Abstract

Monocytes are circulating precursors of the dendritic cell subset, professional antigen-presenting cells with a unique ability to initiate the innate and adaptive immune response. In this study, we have investigated the effects of wild-type Helicobacter pylori strains and their isogenic mutants with mutations in known bacterial virulence factors on monocytes and monocyte-derived dendritic cells. We show that H. pylori strains induce apoptosis of human monocytes by a mechanism that is dependent on the expression of a functional cag pathogenicity island. This effect requires an intact injection organelle for direct contact between monocytes and the bacteria but also requires a still-unidentified effector that is different from VacA or CagA. The exposure of in vitro-generated monocyte-derived dendritic cells to H. pylori stimulates the release of inflammatory cytokines by a similar mechanism. Of note is that dendritic cells are resistant to H. pylori-induced apoptosis. These phenomena may play a critical role in the evasion of the immune response by H. pylori, contributing to the persistence of the infection.

Helicobacter pylori is the major causative agent of chronic superficial gastritis and peptic ulcer disease and plays an important role in the development of adenocarcinoma of the distal stomach in humans (16, 17, 24). H. pylori-induced gastroduodenal disease depends on the inflammatory response of the host and on the production of specific virulence factors that cause damage to gastric epithelial cells and disruption of the gastric mucosal barrier, such as urease (responsible for ammonia generation), the vacuolating cytotoxin VacA, and the cytotoxin-associated protein CagA (16, 24).

Cytokines contribute to mucosal damage, either directly or indirectly, by mediating an inflammatory response to H. pylori. The local cytokine response to H. pylori infection is of the Th1 type, with increased gamma interferon and interleukin-12 (IL-12), but not IL-4, production in the infected gastric mucosa (10, 13). Variation in the ability of H. pylori to trigger chemokines from gastric mucosa depends upon the expression of genes within the cag (cytotoxin-associated gene) pathogenicity island (PAI), a 40-kb chromosomal DNA insertion which contains 31 genes encoding a type IV secretion system for the export of virulence determinants (3). Colonization with cag+ strains induces a more intense tissue response, as reflected by enhanced mucosal inflammation, cell proliferation, and cell death (12, 16). However, the molecular mechanisms that mediate cag PAI-dependent effects on the inflammatory response in either epithelial or monocyte/macrophage cells of the gastric mucosa are still the subject of debate. The only H. pylori virulence factor that has so far been demonstrated to be injected by the type IV secretion system is the CagA protein (3, 4). Following injection into the host cells, CagA is phosphorylated on tyrosine residues by the c-Src/Lyn kinases (20). Phosphorylated CagA activates SHP-2 tyrosine phosphatase and the Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 pathway, inducing a growth factor-like cell response that results in abnormal proliferation of gastric epithelial cells (11, 15). In addition, injected CagA, independently from its phosphorylation status, interacts with components of the apical junctional complex of gastric mucosal cells, causing a disruption of the epithelial barrier function and dysplastic alterations in epithelial cell morphology (1). However, additional effector factors different from CagA seem to be involved in the epithelial cytokine/chemokine response to H. pylori infection (7). Although H. pylori elicits both innate and acquired immune responses, the host is unable to eliminate the organism from the gastric mucosa, and chronic infection is the usual outcome (16, 17, 24).

Dendritic cells (DCs) are antigen-presenting cells derived from circulating bone marrow precursors, including monocytes, with a unique ability to activate and polarize naive T cells (2, 21). Infection by pathogens stimulates the inflammatory process and the consequent recruitment of leukocytes and monocytes. In the peripheral tissues, monocytes differentiate to immature DCs (iDCs), which display an immature phenotype with a high endocytic capability and a low antigen-presenting capability. The exposure of iDCs to the microbial products activates the iDCs and stimulates their terminal differentiation process. This event determines cytokine release, reduction of the antigen uptake capability, and up-regulation of cell surface expression of a variety of proteins, including major histocompatibility complex class I and II, adhesion, and costimulatory molecules. Maturation of DCs is also associated with changes in the cell surface expression of various chemokine receptors (19). This phenomenon is crucial for their migration from inflamed tissues to regional lymph nodes. The constant traffic of T lymphocytes through the paracortical areas of lymph nodes makes this a prime site for antigen-loaded DCs to encounter the low-frequency, antigen-specific naive T cells and to initiate the immune response. The antigen-presenting capacity of DCs critically depends on their state of maturation, which should determine not only the extent of T-cell activation but also the type of T-cell response generated (2, 18, 19).

Recent studies have revealed that pathogen evasion strategies may include interference at different steps in the DC life cycle, from their initial generation to the productive interaction of mature DCs with T cells in lymphoid tissues. Our study was designed to determine whether H. pylori may affect monocyte and DC survival and to identify bacterial virulence factors involved. We found that (i) wild-type H. pylori strains induced apoptosis of human monocytes but not DCs, (ii) bacteria required contact with inflammatory cells to induce apoptosis of human monocytes, and (iii) the expression of a functional cag PAI, but not the vacA or cagA gene, was necessary for the induction of apoptosis in monocytes, as well as for the up-regulation of IL-1, IL-12, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) proinflammatory cytokines in monocyte-derived DCs. We hypothesize that these mechanisms may play a role in the persistence of infection and in the tissue damage of infected gastric mucosa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

We used the VacA+ cag+ wild-type H. pylori strain G27 (23) and its isogenic mutants in which the cagA (G27 cagA) or cagE (G27 cagE) gene or the entire cag PAI (G27 Δcag) was disrupted by insertional mutagenesis (1, 3, 4). The Δcag isogenic mutant (1) was obtained as follows. Expand high-fidelity DNA polymerase enzyme (Roche) was used to amplify G27 chromosomal regions flanking the cag PAI, corresponding to nucleotides 6 to 389 of cagII (accession no. AF282852) and nucleotides 18886 to 19415 of cagI (accession no. AF282853), respectively. The cag region naturally occurring in between was replaced by a 1.4-kb DNA cassette containing the Campylobacter coli aphA-3 kanamycin resistance gene (accession no. M26832). The resulting chimeric fragment was cloned into a pBluescript SK(+) vector (Stratagene) and then used to transform H. pylori G27 bacteria. After natural transformation, the true kanamycin-resistant mutant was selected and confirmed by both sequencing and PCR amplification. In addition, we used the VacA+ cag+ wild-type H. pylori strain 60190 (ATCC 49503) and its isogenic mutants in which vacA (60190 vacA), cagE (60190 cagE), or cag A (60190 cagA) was disrupted by insertional mutagenesis (5, 22). Bacteria were grown on Columbia agar supplemented with 1% Vitox and 10% defibrinated sheep blood (Oxoid) at 37°C under microaerophilic conditions. Immediately before the start of the experiments, bacteria were suspended at different concentrations (from 107 to 108 CFU/ml) in the culture medium used for monocytes and DCs (RPMI supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum).

Isolation of human monocytes and in vitro generation of iDCs.

Monocytes were isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells by positive selection with anti-CD14-coated magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bologna, Italy). Briefly, peripheral blood mononuclear cells were obtained from 30 ml of leukocyte-enriched buffy coat from healthy donors by centrifugation with an F-Lymphoprep gradient (Axis-Shield PoC AS, Oslo, Norway), and the low-density fraction was recovered. Monocytes were purified by positive selection with anti-CD14-conjugated magnetic microbeads. The resultant cells, which were ≥95% CD14+ cells, were analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting for the expression of the surface markers CD14, CD1a, CD83, CD86, CD54, and HLA-DR. Typical immunotype stains for monocytes, expressed as mean fluorescence intensity ± standard deviation (SD), were as follows: CD14, 520 ± 12.5; CD1a, 17 ± 1.4; CD83, 5 ± 1.2; CD86, 130 ± 17; CD54, 153 ± 19.5; and HLA-DR, 857 ± 27. Monocytes were then resuspended at a concentration of 0.5 × 106 to 1 × 106 cells/ml and cultured in RPMI (Gibco BRL Life Technologies Ltd., Paisley, United Kingdom) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 25 mM HEPES, and 2 mM glutamine (complete medium) and containing 50 ng of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor per ml and 250 ng of IL-4 per ml for 5 to 7 days, with cytokines added every second day, to obtain a population of iDCs. Typical immunotype stains for iDCs were as follows: CD14, 12 ± 2.7; CD1a, 564 ± 22.4; CD83, 8.65 ± 1.91; CD86, 601 ± 19.1; CD54, 410 ± 20.4; and HLA-DR, 729 ± 27.4. For the standard coculture experiments, a total of 3.5 × 105 to 1 × 106 monocytes or iDCs were cultured in 700 μl of RPMI complete medium in 48-well plates in the presence of different bacterial concentrations (from 107 to 108 CFU/ml). For the bacterium-cell contact experiments, bacterial suspensions (from 1 × 108 to 5 × 108 CFU/ml) were seeded on the apical compartment of 0.45-μm-pore-size, 12-mm-diameter culture plate Millicell filters (Millipore) that were inserted into a 24-well tissue culture tray containing 106 monocytes/well.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis.

Apoptotic nuclei were evaluated by using propidium iodide (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.) or fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-annexin V (Becton Dickinson) staining. Briefly, the cell pellet was gently resuspended in 0.2 ml of hypotonic fluorochrome solution (50 μg of propidium iodide per ml in 0.1% sodium citrate plus 0.1% Triton X-100). The early apoptotic cells were evaluated by FITC-annexin V binding. Briefly, cells were washed in cold annexin V buffer (10 mM HEPES, 140 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2) prior to treatment with FITC-labeled annexin V (Becton Dickinson) for 15 min at 4°C. For cell surface analysis, monocytes or DCs were preincubated with unconjugated goat gamma globulin (Sigma Chemical, Milan, Italy) for 10 min to block Fc receptor binding and then were double stained with phycoerythrin- and fluorescein-conjugated specific antibodies. For intracellular staining, DCs were incubated at 37°C in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% fetal calf serum. To promote intracellular cytokine retention, 5 μg of brefeldin A (Sigma-Aldrich) per ml was added during the incubation. After 12 h, cells were fixed and permeabilized by using a cytokine-staining kit according the instructions of the manufacturer (Caltag Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.). Cells were than stained with fluorochrome-labeled IL-1, TNF-α, and IL-12 (Becton Dickinson). The fluorescence intensity was measured by using a FACScan cytometer and Cell Quest software (Becton Dickinson).

RESULTS

H. pylori G27 induces apoptosis in human CD14+ monocytes but not in monocyte-derived DCs.

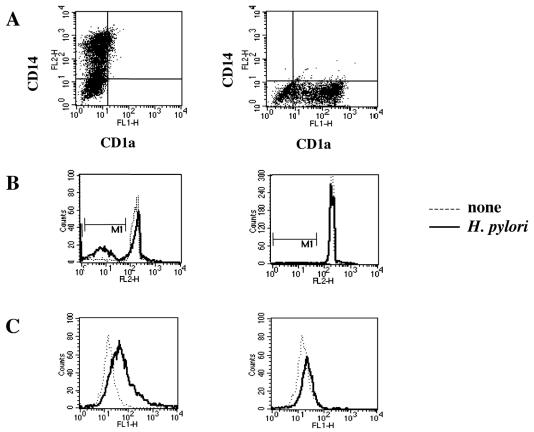

Several reports have shown the ability of H. pylori to trigger the apoptotic program in different cell lines (6, 12, 16). On this basis, we tested the susceptibility of monocytes and monocyte-derived DCs to H. pylori G27-induced apoptosis. We exposed human CD14+ monocytes and CD1a+ monocyte-derived DCs to increasing number of live H. pylori G27 bacteria. As assessed by flow cytometry analysis, a large fraction of monocytes exposed to bacteria underwent programmed cell death. Conversely, CD1a-positive monocyte-derived DCs showed a high resistance to apoptosis (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Effect of H. pylori G27 on nuclear apoptosis in monocytes and DCs. Freshly isolated monocytes or monocyte-derived iDCs were cultured in the presence or absence of H. pylori G27. Sterile culture medium served as a negative control. (A) Immunostaining for CD14 and CD1a. (B) Propidium iodide staining of the nuclei. (C) Early apoptotic cells detected by FITC-conjugated annexin V staining. The results shown are representative of those from one of three independent experiments.

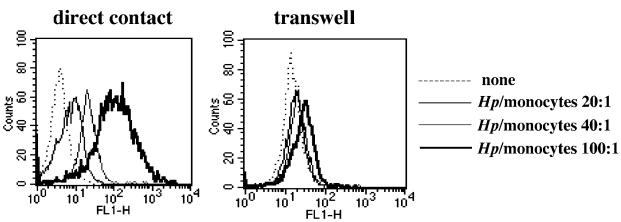

H. pylori G27 requires cell contact to induce apoptosis in human monocytes.

To evaluate whether the induction of apoptosis in human monocytes was dependent on a soluble bacterial virulence factor(s) or required bacterium-monocyte cell contact, we analyzed nuclear apoptosis of monocytes cultured in direct contact with or across a filter barrier from increasing amounts of H. pylori G27 bacterial suspensions. As shown in Fig. 2, H. pylori G27 increased annexin V staining in human monocytes in a dose-dependent manner when cultured at direct contact with monocytes, while the effect was reduced by approximately 90% when a filter barrier was separating bacteria from monocytes. This suggests that H. pylori requires cell contact to induce apoptosis in human monocytes.

FIG. 2.

H. pylori G27 requires cell contact to induce apoptosis in freshly isolated monocytes. H. pylori G27 (Hp)bacterial suspensions were cocultured in direct contact with freshly isolated monocytes (left) or cultured on the apical compartments of 0.45 μm-pore-size Millicell filters that were inserted into a 24-well tissue culture tray containing 106 monocytes/well (right) at a ratio of 20:1, 40:1, or 100:1 bacteria per monocyte. Sterile culture medium served as a negative control. After 24 h, monocytes were stained with FITC-conjugated annexin V and analyzed by cytometry. The results shown are representative of those from one of three independent experiments.

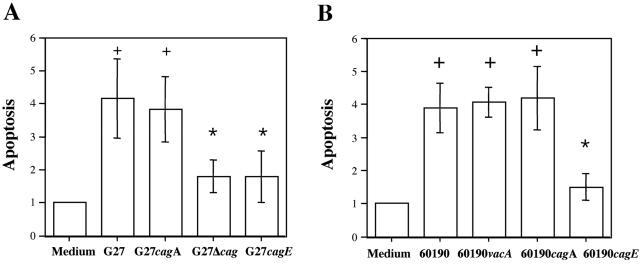

Effect of wild-type H. pylori strains G27 and 60190 and their isogenic mutants on apoptosis in human monocytes.

To identify bacterial virulence factors responsible for H. pylori induction of apoptosis in human monocytes, we compared the effects of the wild-type G27 and 60190 H. pylori strains with those of their respective isogenic mutants with mutations in known virulence factors. As shown in Fig. 3A, wild-type H. pylori strain G27, like its cagA isogenic mutant, increased annexin V staining in human monocytes by approximately fourfold, while G27 Δcag, a G27 strain in which the entire cag PAI has been deleted, and the G27 cagE isogenic mutant strain increased annexin V staining by only twofold. Moreover, wild-type H. pylori strain 60190, as well as the 60190 vacA or cagA isogenic mutant strain, increased annexin V staining by approximately 4-fold, while the 60190 cagE isogenic mutant strain increased staining by 1.5-fold (Fig. 3B). Thus, these data all indicated that H. pylori induction of apoptosis in human monocytes was at least in part dependent on the expression of genes in the cag PAI.

FIG. 3.

Effect of wild-type H. pylori strains G27 and 60190 and their isogenic mutants on apoptosis in human monocytes. Freshly isolated monocytes were cultured in the presence of wild-type G27 or the cagA, cagE, or Δcag isogenic H. pylori strain (A) or in the presence of wild-type 60190 or the vacA, cagA, or cagE isogenic H. pylori strain (B) for 12 h. Sterile culture medium served as a negative control. Early apoptotic cells were detected by FITC-conjugated annexin V staining. Apoptosis values are expressed as fold increase over basal levels and are the means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments. +, P < 0.05 versus control; *, P < 0.05 versus wild type.

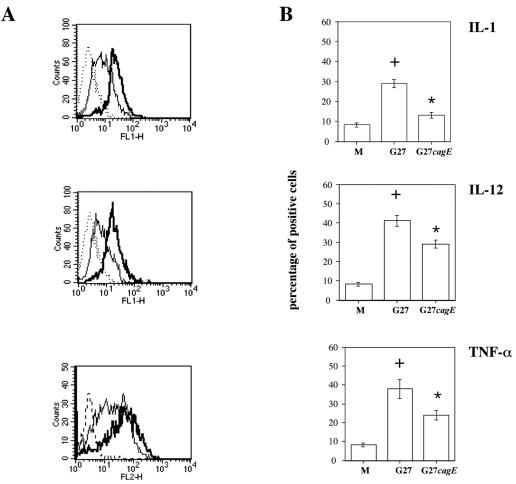

Effect of wild-type H. pylori G27 and cagE isogenic strains on IL-1, IL-12, and TNF-α production in monocyte-derived DCs.

To evaluate whether H. pylori may affect differentiation of DCs, we studied the effect of H. pylori on cytokine production in monocyte-derived iDCs. As shown in Fig. 4, H. pylori G27 increased the percentage of iDCs positive for IL-1, IL-12, and TNF-α intracellular staining by 3-, 4-, and 3.5-fold, respectively. On the other hand, the G27 cagE isogenic mutant increased the percentage of iDCs positive for IL-1, IL-12, and TNF-α intracellular staining by 1.2-, 2.8-, and 2.4-fold, respectively. Moreover, H. pylori G27, like the G27 cagE isogenic mutant, was not able to stimulate the production of IL-10 in iDCs (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Effect of wild-type G27 and cagE isogenic H. pylori strains on IL-1, IL-12, and TNF-α production in monocyte-derived DCs. DCs were infected with wild-type H. pylori G27 and the cagE isogenic mutant at a ratio of 20 bacteria per DC in the presence of brefeldin A. Sterile culture medium served as a negative control. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of IL-1, IL-12, and TNF-α intracellular staining following 12 h of incubation of DCs with an increasing number of cells of H. pylori G27 (thick lines) or its cagE isogenic strain (G27cagE) (thin lines). Dotted lines, control isotypic antibodies. The results shown are representative of those from one of three independent experiments. (B) Percentages of DCs positive for IL-1, IL-12, and TNF-α intracellular staining. The results shown are the means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments. +, P < 0.05 versus control; *, P < 0.05 versus wild type.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have investigated the ability of H. pylori to interfere with the DC life cycle, from their initial generation to their ability to respond to whole live bacteria. We show that H. pylori strains induce apoptosis of human monocytes by a mechanism requiring physical contact between monocytes and bacteria and the expression of a functional cag PAI. Of note is that physical contact and a cag PAI are also required for optimal release of proinflammatory cytokines by iDCs, which are resistant to H. pylori-induced apoptosis.

An important part of the induction of mucosal damage by H. pylori involves activation of apoptosis. In fact, several reports have demonstrated that H. pylori induces gastric epithelial cell apoptosis in vivo and in vitro (6, 12, 16). Moreover, it has been recently shown that H. pylori induces apoptosis in the murine macrophage cell line RAW 264.7, as well as in peritoneal macrophages isolated from C57BL/6 mice (8). We also demonstrate that induction of apoptosis in human monocytes by H. pylori requires direct contact of bacteria with the inflammatory cells. However, a 10% residual effect on apoptosis is still present when a filter barrier separates bacteria from monocytes, thus raising the possibility that a soluble bacterial virulence factor might be responsible for this. Because our data also show that a mutation in the vacA gene does not alter the ability of the bacteria to induce apoptosis in human monocytes, we can exclude VacA cytotoxin as the soluble virulence factor involved. In contrast to our results, VacA cytotoxin has been demonstrated to induce apoptosis of gastric epithelial cells (6). This discrepancy can be explained by differences between inflammatory and epithelial cells in the control of survival.

H. pylori cag+ strains induce more severe gastritis, proliferation, and apoptosis in infected gastric mucosa than do cag mutant strains (12, 16). The type IV secretion system encoded by the cag PAI regulates H. pylori infection of gastric mucosa by (i) increasing the capacity to initiate colonization of gastric mucosa (14); (ii) stimulating the translocation into gastric epithelial cells of the bacterial effector protein CagA, which promotes a growth factor-like response (4, 11, 15, 20) and alters the epithelial barrier function (1); and (iii) inducing the synthesis of chemokines and the host inflammatory response (3, 7, 12, 17). Systematic mutagenesis of the H. pylori cag PAI has identified genes that, upon inactivation, are unable to translocate CagA into host cells but still retain the ability to induce chemokines (7). The data reported here show that the entire cag PAI in H. pylori strain G27 or the cagE gene in H. pylori strains G27 and 60190 is essential for the full induction of apoptosis in human monocytes. In contrast, CagA does not seem to play a role. That H. pylori requires the entire cag PAI or the cagE gene, as well as direct contact with the inflammatory cells, but does not require the cagA gene suggests that a functional cag secretion system and the translocation of a still-unidentified bacterial effector different from CagA are necessary to induce apoptosis of human monocytes. On the other hand, G27 Δcag, G27 cagE, and 60190 cagE isogenic mutant strains are still able to stimulate apoptosis in human monocytes, although to a lesser extent. Based on this, we cannot exclude the possibility that a still-unidentified bacterial virulence factor independent of the cag secretion system could be also responsible for induction of apoptosis.

H. pylori infection elicits a Th1 cell response, with increased gamma interferon and IL-12 but not IL-4 (10, 13), and this has been associated with the presence of the cag PAI (10). In keeping with this observation, we show here that H. pylori requires the expression of cagE for the full induction of IL-1, IL-12, and TNF-α, but not IL-10, cytokines in iDCs. Similar to our observations, a recent report showed that H. pylori preferentially induces IL-12 rather IL-6 or IL-10 in human DCs (9). IL-12 and IL-18 production by antigen-presenting cells stimulates, while IL-10 production down-regulates, a Th1 T-cell response (2, 19). Therefore, the production of IL-12, in the absence of IL-10 induction, from DCs during H. pylori infection suggests that H. pylori elicits a Th1 response. Interestingly, the same virulence factor(s) in the cag PAI that is responsible for the induction of apoptosis in monocytes is also essential for cytokine induction in iDCs. However, because G27 cagE still retains the ability to stimulate the synthesis of IL-1, IL-12, and TNF-α in iDCs, we can postulate that a still-unidentified bacterial virulence factor different from the cag secretion system might also play a role in this phenomenon.

In conclusion, in the present paper we provide novel information on the roles played by the type IV secretion system encoded by the H. pylori cag PAI in the biology of the host-pathogen interaction. The ability of the H. pylori cag PAI to induce apoptosis in monocytes and to stimulate the release of proinflammatory cytokines by iDCs suggests that the presence of the cag PAI is crucial for the evasion of immune recognition through reduction of the number of iDCs, as well as for the damage of the gastric mucosa during the persistence of local infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Salvatore De Simone for technical assistance and Mario Berardone for the artwork.

This work was supported in part by grants from the Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca Scientifica e Tecnologica, Italy (PRIN 2002 to R.Z. and L.R.).

Editor: V. J. DiRita

Footnotes

We dedicate this study to the memory of Stelio Varrone, a mentor in science and life.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amieva, M. R., R. Vogelmann, A. Covacci, L. S. Tompkins, W. J. Nelson, and S. Falkow. 2003. Disruption of the epithelial apical-junctional complex by Helicobacter pylori CagA. Science 300:1430-1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banchereau, J., and R. M. Steinman. 1998. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 392:245-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Censini, S., C. Lange, Z. Xiang, J. E. Crabtree, P. Ghiara, M. Borodovsky, R. Rappuoli, and A. Covacci. 1996. cag, a pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori, encodes type-I specific and disease-associated virulence factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:14648-14653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Censini, S., M. Stein, and A. Covacci. 2001. Cellular responses induced after contact with Helicobacter pylori. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 4:41-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cover, T. L., M. K. R. Tummuru, P. Cao, S. A. Thompson, and M. J. Blaser. 1994. Divergence of genetic sequences for the vacuolating cytotoxin among Helicobacter pylori strains. J. Biol. Chem. 269:10566-10573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cover, T. L., U. S. Krishna, D. A. Israel, and R. M. Peek. 2003. Induction of gastric epithelial cell apoptosis by Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin. Cancer Res. 63:951-957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischer, W., J. Puls, R. Buhrdorf, B. Gebert, S. Odenbreit, and R. Haas. 2001. Systematic mutagenesis of the Helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island: essential genes for cagA translocation in host cells and induction of interleukin-8. Mol. Microbiol. 42:1337-1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gobert, A. P., Y. Cheng, J. Y. Wang, J. L. Boucher, R. K. Iyer, S. D. Cederbaum, R. A. Casero, Jr., J. C. Newton, and K. T. Wilson. 2002. Helicobacter pylori induces macrophage apoptosis by activation of arginase II. J. Immunol. 168:4692-4700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guiney, D. G., P. Hasegawa, and S. P. Cole. 2003. Helicobacter pylori preferentially induces interleukin 12 (IL-12) rather than IL-6 or IL-10 in human dendritic cells. Infect. Immun. 71:4163-4166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hida, N., T. Shimoyama, Jr., P. Neville, M. F. Dixon, A. T. Axon, T. Sr. Shimoyama, and J. E. Crabtree. 1999. Increased expression of IL-10 and IL-12 (p40) mRNA in Helicobacter pylori infected gastric mucosa: relation to bacterial cag status and peptic ulceration. J. Clin. Pathol. 52:658-664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higashi, H., R. Tsutsumi, S. Muto, T. Sugiyama, T. Azuma, M. Asaka, and M. Hatakeyama. 2002. SHP-2 tyrosine phosphatase as an intracellular target of Helicobacter pylori CagA protein. Science 295:683-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Israel, D. A., N. Salama, C. N. Arnold, S. F. Moss, T. Ando, H. P. Wirth, K. T. Tham, M. Camorlinga, M. J. Blaser, S. Falkow, and R. M. Peek. 2001. Helicobacter pylori strain-specific differences in genetic content, identified by microarray, influence host inflammatory responses. J. Clin. Investig. 107:611-620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindholm, C., M. Quiding-Jarbrink, H. Lonroth, A. Hamlet, and A.-M. Svennerholm. 1998. Local cytokine response in Helicobacter pylori-infected subjects. Infect Immun. 66:5964-5971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marchetti, M., and R. Rappuoli. 2002. Isogenic mutants of the cag pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori in the mouse model of infection: effects on colonization efficiency. Microbiology 148:1447-1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mimuro, H., T. Suzuki, J. Tanaka, M. Asahi, R. Haas, and C. Sasakawa. 2002. Grb2 is a key mediator of Helicobacter pylori CagA protein activities. Mol. Cell 10:745-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peek, R. M., and M. J. Blaser. 2002. Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal tract adenocarcinomas. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2:28-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ricci, V., R. Zarrilli, and M. Romano. 2002. Voyage of Helicobacter pylori in human stomach: odyssey of a bacterium. Digest. Liver Dis. 35:2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sallusto, F., and A. Lanzavecchia. 1994. Efficient presentation of soluble antigen by cultured human dendritic cells is maintained by granulocytes/macrophage colony-stimulating factor plus interleukin 4 and downregulated by tumor necrosis factor alfa. J. Exp. Med. 179:1109-1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sallusto, F., P. Schaerli, P. Loetscher, et al. 1998. Rapid and coordinated switch in chemokine receptor expression during dendritic cell maturation. Eur. J. Immunol. 28:2760-2769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stein, M., F. Bagnoli, R. Halenbeck, R. Rappuoli, W. J. Fanti, and A. Covacci. 2002. C-Src/Lyn kinases activate Helicobacter pylori CagA through tyrosine phosphorylation of the EPIYA motifs. Mol. Microbiol. 43:971-980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steinman, R. 1991. The dendritic cell system and its role in immunogenicity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 9:271-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tummuru, M. K. R., S. A. Sharma, and M. J. Blaser. 1995. Helicobacter pylori picB, a homolog of the Bordetella pertussis toxin secretion protein, is required for induction of IL-8 in gastric epithelial cells. Mol. Microbiol. 18:867-876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiang, Z., S. Censini, P. F. Bayeli, J. L. Telford, N. Figura, R. Rappuoli, and A. Covacci. 1995. Analysis of expression of CagA and VacA virulence factors in 43 strains of Helicobacter pylori reveals that clinical isolates can be divided into two major types and that CagA is not necessary for expression of the vacuolating cytotoxin. Infect. Immun. 63:94-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zarrilli, R., V. Ricci, and M. Romano. 1999. Molecular response of gastric epithelial cells to Helicobacter pylori-induced cell damage. Cell Microbiol. 1:93-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]