Abstract

The small GTPase Ran regulates the interaction of transport receptors with a number of cellular cargo proteins. The high affinity binding of the GTP-bound form of Ran to import receptors promotes cargo release, whereas its binding to export receptors stabilizes their interaction with the cargo. This basic mechanism linked to the asymmetric distribution of the two nucleotide-bound forms of Ran between the nucleus and the cytoplasm generates a switch like mechanism controlling nucleo-cytoplasmic transport. Since 1999, we have known that after nuclear envelope breakdown (NEBD) Ran and the above transport receptors also provide a local control over the activity of factors driving spindle assembly and regulating other aspects of cell division. The identification and functional characterization of RanGTP mitotic targets is providing novel insights into mechanisms essential for cell division. Here we review our current knowledge on the RanGTP system and its regulation and we focus on the recent advances made through the characterization of its mitotic targets. We then briefly review the novel functions of the pathway that were recently described. Altogether, the RanGTP system has moonlighting functions exerting a spatial control over protein interactions that drive specific functions depending on the cellular context.

Keywords: spindle, RanGTP, microtubule, cell division, importin, SAF, nucleo-cytoplasmic transport, exportin

Historical perspective on the chromatin dependent MT assembly pathway

The first hints of the existence of a chromosome-dependent MT assembly mechanism in the dividing cell were obtained in the 1970–1980s when several groups reported that MT nucleation occurred close to or at the kinetochores (McGill and Brinkley, 1975; Telzer et al., 1975; Witt et al., 1980; De Brabander et al., 1981) and a spindle like structure formed around lambda DNA injected into metaphase arrested Xenopus eggs (Karsenti et al., 1984). In 1996, DNA coated beads were shown to trigger bipolar spindle formation when incubated in Xenopus egg extracts (Heald et al., 1996), providing further support to the idea that chromatin carries all the information required to direct MT assembly and organization in the M-phase cytoplasm. Shortly after, the identification of the small Ran GTPase as driver of chromatin-dependent MT assembly in the M-phase cytoplasm provided a major breakthrough to understand the underlying mechanism (Carazo-Salas et al., 1999; Kalab et al., 1999; Ohba et al., 1999; Wilde and Zheng, 1999; Zhang et al., 1999). Today, we know that the chromosomes drive MT assembly and organization into a bipolar spindle in a RanGTP dependent manner in most cells (Karsenti and Vernos, 2001; Rieder, 2005).

In this mini-review we will describe briefly how the RanGTP system regulates the nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling of components in interphase and, after NEBD, the activity and/or localization of specific factors to drive spindle assembly. We will briefly review our current knowledge on the identity and function of RanGTP regulated factors and the recent advances on understanding novel mechanisms regulated by RanGTP. Finally we will provide an overview of the regulation of the RanGTP pathway itself during mitosis, its conservation in different organisms and cell types, and its role in other cellular functions. For additional information we refer the reader to excellent reviews (Ciciarello et al., 2007; O'Connell and Khodjakov, 2007; Clarke and Zhang, 2008; Kalab and Heald, 2008; Roscioli et al., 2010; Forbes et al., 2015).

The nucleo-cytoplasmic transport and the small GTPase ran

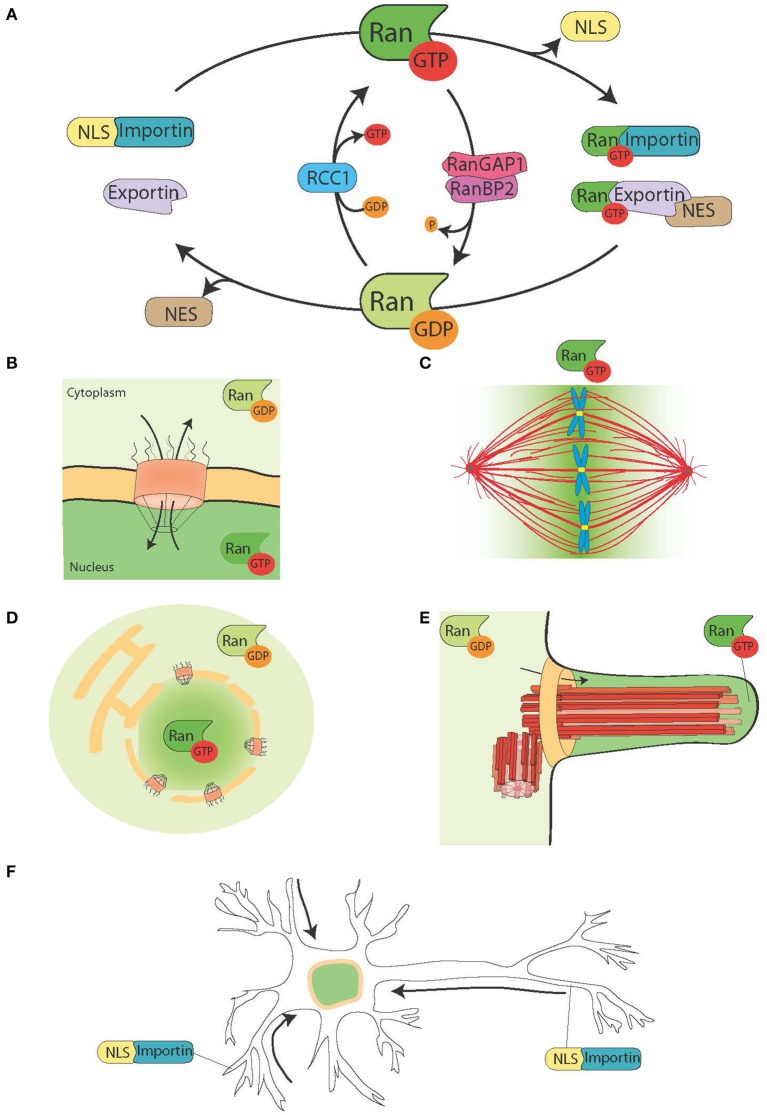

Eukaryotic cells are compartmentalized and have specific transport systems for the communication between the cytoplasm and the different membrane-bound organelles. The nucleo-cytoplasmic transport system is essential to connect functionally the transcription of the genome that occurs within the nucleus, with protein translation that takes place in the cytoplasm (Figures 1A,B). The transport of molecules in and out of the nucleus occurs through the nuclear pore complex (NPC), a big protein complex of ~60 MDa inserted into the nuclear membrane (Sorokin et al., 2007). Small cargos (< 40 kDa) diffuse rapidly through the NPC. Instead, proteins larger than 40 kDa require an active transport through the NPC that involves soluble nuclear transport receptors (NTRs) that belong to the karyopherin-β protein family. NTRs that facilitate the transport of cargo proteins into the nucleus are called importins and interact with their cargo through a nuclear localization signal (NLS) rich in basic residues. NTRs facilitating the export of proteins out of the nucleus are called exportins and interact with their cargo through a nuclear export signal (NES) rich in hydrophobic residues such as leucine. The karyopherin-β importin β1 often interacts with the cargo through an adaptor of the importin α family (Sorokin et al., 2007). Importin α binds directly to the NLS of the cargo protein and to importin β1 through an IBB domain (importin β binding domain), leading to the formation of a trimeric complex.

Figure 1.

The Ran system and its moonlighting functions. (A) Schematic representation of the Ran system for the spatial control of NLS and NES carrying proteins. In cells Ran is found in two forms, RanGTP (green), and RanGDP (light green). RCC1 (light blue) promotes the exchange of GDP to GTP, while RanGAP1-RanBP2 (in pink and purple) promote the hydrolysis of GTP into GDP. RanGTP binds to the importins (turquoise green) and exportins (light purple). Exportins in complex with RanGTP can associate to the NES-proteins (in brown). On the other hand, the binding of RanGTP to importins trigger their dissociation from NLS-proteins (yellow). (B) During interphase, the Ran system controls the nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling of proteins, because RanGTP is predominant in the nucleoplasm and RanGDP is predominant in the cytoplasm (Sorokin et al., 2007). (C) During mitosis the association of RCC1, the RanGEF, with the chromosomes defines a gradient of RanGTP concentrations that promote the release of SAFs and MT nucleation around the chromatin. The Ran system is converted into a pathway for MT assembly and organization that is essential for mitotic spindle assembly. The RanGTP pathway depends on the establishment of a concentration gradient of RanGTP that peaks around the chromosomes (Kalab et al., 2002; Caudron et al., 2005). (D) At the end of mitosis, the Ran system also regulates nuclear membrane and NPC reassembly by controlling membrane fusion and releasing NPC components (Walther et al., 2003; Harel et al., 2003). (E) In ciliated cells RanGTP accumulates in the cilioplasm and promotes the transport and accumulation of Kif17 and retinis pigmentosa 2 to the cilioplasm (Dishinger et al., 2010; Fan et al., 2011; Hurd et al., 2011). (F) In neurons many SAFs have a function. Furthermore, importins localize to the dendritic synaptic space and are involved in the transport of cargos to the nucleus (Jordan and Kreutz, 2009; Panayotis et al., 2015). The Ran system is also active in the axon of the sciatic nerve, where upon injury importins promote the transport of cargos toward the neuron cell body (Hanz et al., 2003; Yudin et al., 2008).

NTRs associate with the small GTPase Ran that acts as a molecular switch. In its GTP bound form, Ran (RanGTP) interacts with karyopherin-β proteins with high affinity, while it dissociates in its GDP bound form (RanGDP). RanGTP binding to importins and exportins have very different consequences: it stabilizes the exportin-cargo interaction whereas it destabilizes the importin-cargo interaction (Figure 1A).

The RanGEF (guanine nucleotide exchange factor) RCC1 associates with the chromatin inside the nucleus, whereas RanGAP (GTPase activating protein) is cytoplasmic. As a consequence the predominant form of Ran in the nucleus is bound to GTP, while in the cytoplasm it is bound to GDP. Thereby NLS proteins transported to the nucleus by importins are released and accumulate in the nucleoplasm, whereas NES proteins in complex with exportin-RanGTP are transported out of the nucleus (Figures 1A,B).

Although the nucleo-cytoplasmic transport is no longer needed when a cell enters into mitosis, its complex molecular machinery is recycled to promote MT assembly around the chromatin and to direct the organization of the bipolar spindle (Clarke and Zhang, 2008).

The RanGTP pathway during cell division

As RCC1 remains associated with the chromatin after NEBD, RanGTP is highly enriched in the proximity of the chromosomes. As RanGTP diffuses away from the chromatin, RanGAP in the cytoplasm converts it into RanGDP (Figure 1C). The resulting gradient has been directly visualized in cells and Xenopus egg extracts (Kalab et al., 2002, 2006) and its properties in MT nucleation and stabilization tested and modeled (Caudron et al., 2005). Like in interphase, this system provides a spatial control over the stability of NTRs-cargo complexes. The cargos are NLS and/or NES containing proteins with specific functions related to spindle assembly and function. The NLS-proteins with a role in spindle assembly have been named SAFs (Spindle Assembly Factors).

The discovery and characterization of the RanGTP pathway prompted a re-examination of the Search and Capture model for spindle assembly proposed in 1986 (Kirschner and Mitchison, 1986). This model postulates that centrosomal MTs grow and shrink exploring the cytoplasmic space until a stochastic encounter with a kinetochore promotes their capture and attachment. However, it has been now clearly established that animal cells experimentally deprived from their centrosomes do assemble a functional mitotic spindle (Debec et al., 1995; Khodjakov et al., 2000). Moreover, mathematical simulations suggested that the Search and Capture mechanism could not account for the short division time observed in most animal cells (Wollman et al., 2005). By promoting MT nucleation and stabilization in the proximity of the chromosomes, the RanGTP pathway most certainly favors MT capture by the kinetochores increasing the efficiency of the Search and Capture mechanism. However, the role of the RanGTP pathway must go beyond MT capture by the kinetochores and kinetochore-fiber (K-fiber) formation since it also promotes MT organization in the absence of chromosomes, kinetochores, and K-fibers (Carazo-Salas et al., 1999). The identification of the direct and indirect RanGTP targets in the M-phase cytoplasm is therefore an essential step to fully understand the several roles this pathway fulfills during cell division.

Understanding the RanGTP pathway through the identification and functional characterization of its targets

A direct read out of the role of RanGTP in the M-phase cytoplasm was obtained in Xenopus egg extracts devoid of chromatin and centrosomes. Addition of RanGTP to these extracts is indeed sufficient to trigger MT nucleation, promote MT stabilization, and induce the organization of MT assemblies named mini-spindles (Carazo-Salas et al., 1999, 2001). Therefore, one or more SAFs maybe involved in these different events.

Since the identification of the first SAFs in 2001 (Gruss et al., 2001; Nachury et al., 2001; Wiese et al., 2001; Clarke and Zhang, 2008; Meunier and Vernos, 2012), the number of proteins controlled by RanGTP in mitosis has been slowly growing and several novel SAFs were identified recently (CDK11, CHD4, ISWI, Kif14, Kif2a, MCRS1, Mel28, Anillin, APC; Silverman-Gavrila et al., 2008; Yokoyama et al., 2008, 2009, 2014; Dikovskaya et al., 2010; Meunier and Vernos, 2011; Samwer et al., 2013; Wilbur and Heald, 2013). Currently, 22 proteins have been validated as SAFs (Table 1). In addition, a number of proteins with established roles in various aspects of spindle assembly are nuclear and could therefore be targets for RanGTP regulation (i.e., Kif4a/Klp1, Ino80, Reptin), but further studies should address this possibility.

Table 1.

Spindle assembly factors.

| Protein name | Mitotic function | Mitotic localization | Interphase function | Interphase localization | Importin | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromatin Remodeling | CHD4 | Stabilizes MTs | MTs and DNA | Chromatin Remodeling complex (NuRD), to inhibit transcription; also in DNA damage response | Nucleus | α1–β1 | Oshaughnessy and Hendrich, 2013; Stanley et al., 2013; Yokoyama et al., 2013 |

| ISWI1 | Stabilizes MTs, mostly in anaphase | Centrosomes, Spindle poles and DNA | ATPase subunit of Chromatin remodeling complex; involved in DNA repair, DNA Replication, Chromatin structure | Nucleus | α1–β1 | Yokoyama et al., 2009; Toto et al., 2014 | |

| MCRS1 | Protects MT -end, favors Chromatin MT assembly and K-fiber formation | Spindle poles, K-fibers—ends | rRNA production; Ino80 complex, NSL complex | Nucleolar | β1 | Shimono et al., 2005; Raja et al., 2010; Watanabe and Peterson, 2010; Meunier and Vernos, 2011 | |

| Kinesins | Kif14-NabKin | +end directed motor, important for chromosome congression and cytokinesis | MTs | Focal adhesion (Rap1a-Radil signaling) | Cytoplasm, MTs and Centrosome | β1 | Zhu et al., 2005; Carleton et al., 2006; Ahmed et al., 2012; Samwer et al., 2013 |

| Kid (Kif22) | +end directed chromokinesin, important for for chromosome arm congression | MTs and Chromatin | n.d. | Nucleus | α1-β1 | Tokai et al., 1996; Tahara et al., 2008 | |

| HSET/XCTK2/KIFC1 | -end directed kinesin, important for pole focusing | MTs | Endocytic transport and DNA transport | Nucleus | α1-β1 | Walczak et al., 1997; Ems-McClung et al., 2004; Nath et al., 2007; Farina et al., 2013 | |

| Kif2a | MT depolymerizing kinesin. Important for spindle length, pole coalescence, and chromosome congression | MTs | ? Primary cilia disassembly; axonal pruning | Centrosome | α1-β1 | Maor-Nof et al., 2013; Wilbur and Heald, 2013; Eagleson et al., 2015; Miyamoto et al., 2015 | |

| Nuclear Pore Complex | Mel28/ELYS | Ran Dependent MT nucleation, interacts with γTubulin | Spindle poles, kinetochores | NPC re-assembly | NPC | β1; transp. | Rasala et al., 2006; Lau et al., 2009; Yokoyama et al., 2014 |

| Nup107-160 complex | Ran Dependent MT nucleation, interacts with γTubulin, CPC localization | Spindle poles, kinetochores | NPC | NPC | β1; transp. | Orjalo et al., 2006; Lau et al., 2009; Platani et al., 2009; Mishra et al., 2010 | |

| Nup98 | Inhibits MCAK activity | n.d. | NPC | NPC | β1; transp. | Lau et al., 2009; Cross and Powers, 2011 | |

| Rae1 | Spindle organization; counteracts NuMa function | Spindle poles | Nucleoporine, involved in RNA export, interacts with Nup98 | NPC | β1 | Pritchard et al., 1999; Blower et al., 2005; Wong et al., 2006 | |

| Lamin B3* | Spindle organization, supposedly through the spindle matrix | MTs | Mechanical properties of the nucleus, but also DNA replication, DNA transcrption and DNA damage | Nucleus and NE | α1-β1 | Tsai et al., 2006; Adam et al., 2008; Osmanagic-Myers et al., 2015 | |

| Others | TPX2 | MT nucleation, MT bundling, AurA activation | MTs | Binds DNA; post mitotic neurons MT assembly | Nucleus | α1-β1 | Wittmann et al., 2000; Gruss et al., 2001; Mori et al., 2009; Neumayer et al., 2014; Scrofani et al., 2015 |

| NuMA | Spindle pole formation and Spindle positioning | MTs | Nuclear matrix; Chromatin organization; Splicing; Recombination upon DNA damage | Nucleus | β1 | Compton and Cleveland, 1993; Zeng et al., 1994; Gaglio et al., 1995; Nachury et al., 2001; Wiese, 2001; Abad et al., 2007; Radulescu and Cleveland, 2010; Kiyomitsu and Cheeseman, 2012; Vidi et al., 2014 | |

| NuSAP | Important for MT stabilization and crosslinking, favors MT assembly in proximity of chromatin | MTs and chromatin | n.d. | Nucleolar | α1-β1; -β7 | Raemaekers, 2003; Ribbeck et al., 2006, 2007 | |

| HURP | Stabilizes and bundles MTs, specially k- fibers | k- fibers | Adherent Juntions in Epithelial cells | Mostly Cytoplasm, but it shuttles | β1 | Tsou et al., 2003; Laprise et al., 2004; Koffa et al., 2006; Sillje et al., 2006 | |

| TACC3 | MT elongation and K-fiber formation | Spindle poles and MTs | mRNA translation; Sequesters transcription factor FOG1; Hypoxia Inducible Factor complex; +Tips MTs | Cytoplasmic, MTs | β1, not clear data | Stebbins-Boaz et al., 1999; Gergely et al., 2000; Garriga-Canut and Orkin, 2004; Peset et al., 2005; Albee et al., 2006; Guo et al., 2013; Nwagbara et al., 2014 | |

| CDK11 | Centrosome maturation and MT stability) | Spindle poles/centrosomes | Many; i.e., mRNA splicing | Nucleus and Centrosomes | β1 | Petretti et al., 2006; Yokoyama et al., 2008; Malumbres, 2014 | |

| Xnf7** | Stabilizes and bundles MTs; inhibits APC/C at anaphase on set | MTs | Transcription, E3 Ub ligase | Nucleus | β1 | Etkin et al., 1997; Casaletto, 2005; Maresca et al., 2005; Beenders et al., 2007; Sinnott et al., 2014 | |

| APC | Bundles MTs | MTs and kinetochores | Many: Transcription, cell migration, Wnt signaling pathway, inhibits DNA replication | Cytoplasmic, MTs | β1 | Dikovskaya et al., 2001, 2004, 2010, 2012; Perchiniak and Groden, 2011 | |

| Crb3-Clp1*** | Not charcterized function, disorganized spindles | Spindle poles | n.d. | Cilia and Nuclear membrane | β1 | Fan et al., 2007 | |

| Anillin | Cytokinesis, membranes elongation in anaphase | Cell cortex | Sequestered to the nucleus, if in the cytoplasm is deleterious | Nucleus | α1-β1 | Field and Alberts, 1995; Silverman-Gavrila et al., 2008;Kiyomitsu and Cheeseman, 2013 |

Only amphibians have Lamin B3;

XL name (By Blast TRIM69, 43% identity, Trim69i impairs spindle assembly);

Crb3, no Clp1.

Interestingly, the functional characterization of some of the SAFs is providing mechanistic insights into the RanGTP pathway functions in the dividing cell. The mechanism by which RanGTP promotes MT nucleation de novo in the M-phase cytoplasm was recently described (Scrofani et al., 2015). By releasing TPX2 from importins, RanGTP promotes its interaction with Aurora A and with a RHAMM-NEDD1-γTURC (γTubulin Ring Complex) complex. In this new complex the activated Aurora A phosphorylates NEDD1, an essential requirement for MT nucleation. Another SAF, Mel28, was shown to interact with the γTuRC and it was proposed to play a role in RanGTP dependent MT nucleation (Yokoyama et al., 2014). The potential cooperation of Mel28 with the TPX2-dependent pathway described above remains to be established.

The RanGTP pathway also contributes to centrosome maturation and its MT assembly activity (Carazo-Salas et al., 2001). In fact two SAFs, CDK11, and Mel28 were shown to favor MT assembly at the centrosome (Yokoyama et al., 2008, 2014).

The identification and characterization of another SAF, MCRS1, has revealed a novel and important mechanism for the regulation of K-fiber MT minus-end dynamics (Meunier and Vernos, 2011) and novel insights on the roles of the RanGTP pathway in spindle assembly and cell division (Meunier and Vernos, 2012). MCRS1, in complex with members of the chromatin modifier KAT8-associated nonspecific lethal (KANSL) complex (Meunier et al., 2015), is targeted to the minus-end of RanGTP-dependent MTs protecting them from depolymerisation. Within the spindle MCRS1 also associates specifically with the minus-ends of K-fiber MTs and regulates their depolymerisation rate playing an essential role in K-fiber dynamics and chromosome alignment (Meunier and Vernos, 2011; Meunier et al., 2015). The specific association of MCRS1 with the MTs nucleated by the RanGTP dependent pathway also suggests that these MTs have specific characteristics that distinguish them from the MTs nucleated by the centrosomes. If this turns out to be true, the chromosomal MTs would not be merely a local supply of MTs favoring an efficient Search and Capture mechanism, but they could provide essential unique functionalities required for the assembly and function of the bipolar spindle (Meunier et al., 2015).

Recently the MT depolymerizing kinesin Kif2a was shown to be regulated by RanGTP in mitosis, revealing an important mechanism for the scaling of the spindle to the cell size during the early development of Xenopus embryos (Wilbur and Heald, 2013). Kif2a is maintained inactive by importin α until stage 8 of embryonic development. As the soluble concentration of importin α decreases, Kif2a is released and function as a MT depolymerase promoting spindle shortening.

Although, most of the SAFs identified so far were found to play a role in the early phases of cell division, a number of recent reports indicate that the RanGTP pathway has other essential roles not directly related to spindle assembly. Indeed, the characterization of the SAF ISWI suggests functions for the RanGTP pathway during anaphase (Yokoyama et al., 2009).

Multiple lines of research also indicate that it plays a role in spindle positioning. Indeed, before entry into anaphase, the RanGTP gradient restricts the localization of the LGN-NuMa complex to cell cortex areas further away from the chromosomes, contributing to the control of spindle position and orientation (Kiyomitsu and Cheeseman, 2012).

In addition, RanGTP also regulates non-MT related targets. Indeed, it controls Anillin localization and triggers asymmetric membrane elongation during anaphase, defining spindle positioning at the center of the dividing cell (Silverman-Gavrila et al., 2008; Kiyomitsu and Cheeseman, 2012). Finally, during cytokinesis the RanGTP pathway regulates the activity of the kinesin Kif14/Nabkin in actin bundling (Carleton et al., 2006; Samwer et al., 2013) and coordinates nuclear membrane and NPC reassembly (Harel et al., 2003; Walther et al., 2003; Ciciarello et al., 2010; Roscioli et al., 2010; Forbes et al., 2015; Figure 1D).

It is therefore clear that the identification and functional characterization of the RanGTP mitotic targets is providing novel insights into the mechanism of spindle assembly and cell division. However, it is unclear whether many or only a few more RanGTP targets remain to be identified. This number could be potentially high as the number of nuclear proteins is in the order of hundreds or thousands (Dellaire et al., 2003), at least one order of magnitude above the current number of known RanGTP targets in the dividing cell (Table 1).

Most of the proteomic studies aimed at identifying novel SAFs have focused on importins α1 and β1 (Nachury et al., 2001; Wiese et al., 2001; Yokoyama et al., 2008), which are two of the most abundant importins in Xenopus egg extracts (Bernis et al., 2014; Wuhr et al., 2014). However, there are five additional α-importins and eight additional β-importins in humans (Cautain et al., 2015).

Although still scarce, some data indicate that indeed other importins also play a role during cell division. The RanGTP regulation of NuSAP was shown to depend on importin-β1 and importin-7 (Ribbeck et al., 2006) and that of Mel28, Nup107-160, and Nup98 on importin-β1 and transportin/importin-β2 (Lau et al., 2009). Transportin was also specifically shown to negatively regulate spindle assembly and nuclear membrane and NPC reassembly (Bernis et al., 2014). However, there are no described mitotic factors exclusively regulated by importin-7 or transportin.

The characterization of possible transportin specific targets and, more generally, of the other importins α and β represents an open field for exploration. This could be important to understand the regulation of the RanGTP pathway, especially considering that importins expression patterns change significantly in different developmental stages and tissues (Hosokawa et al., 2008).

Regulation of the RanGTP system during cell division

Beyond the specificities of NTR-SAF interactions, several mechanisms may directly impinge upon the RanGTP pathway during cell division. Several data suggest that RCC1 itself is a key component under fine regulation. Human cells have three isoforms of RCC1, that are expressed in a tissue specific manner (Hood and Clarke, 2007). The isoforms differ at their N-terminus, a region involved in importin binding and regulated by phosphorylation, which was proposed to influence chromosome-coupled RanGTP production (Hood and Clarke, 2007; Li et al., 2007). Moreover, the level of RCC1 expression also varies in different cells and correlates with the steepness of the RanGTP gradient (Hasegawa et al., 2013). This may have important consequences as it was proposed that the steepness of the RanGTP gradient determines the length of prometaphase and metaphase which in turn may be relevant for chromosome segregation fidelity (Silkworth et al., 2012; Hasegawa et al., 2013).

Other mechanisms, such as post-translational modifications and alternative splicing are also potential strategies to control the NLS of SAFs. However, these mechanisms would rather affect a particular protein than the whole RanGTP pathway.

Recently, an alternative mechanism for the regulation of SAFs independently of RanGTP was proposed. The targeting of the Golgi protein GM130 to fragmented Golgi membranes in mitosis may compete out locally TPX2 from the importin α1 binding, thus favoring MT assembly in the vicinity of Golgi fragments (Wei et al., 2015). This competition-based mechanism could be another strategy to locally control SAFs sequestered by importins.

The role of other components of the nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling machinery during mitosis

The binding of RanGTP to exportins stabilizes its interaction with NES-cargo proteins. The major exportin, CRM1, was shown to be involved in the targeting of NES-proteins to the kinetochore or the centrosomes. At the kinetochore, CRM1 recruits the RanBP2-RanGAP1-SUMO complex that is required for the interaction between MTs and the kinetochore (Arnaoutov et al., 2005). However, it is still mechanistically unclear how this complex favors the MT-kinetochore interaction (Forbes et al., 2015). CRM1 also promotes the recruitment of RanGAP1-RanBP2 to the spindle in a RanGTP dependent manner (Wu et al., 2013) and it is involved in tethering the Chromosome Passenger Complex to the centromere through its direct interaction with survivin (Knauer et al., 2006). CRM1 has also been shown to promote the recruitment of BRCA1 and pericentrin to the mitotic centrosomes, thus promoting the MT assembly activity of the centrosomes (Liu et al., 2009; Brodie and Henderson, 2012). Recently, the transcriptional repressor Bach1 was found to play a role in chromosome arm alignment during mitosis and to be excluded from the chromosomes during metaphase in a CRM1-dependent way (Li et al., 2012).

However, the significance of these targeting events is not entirely clear mechanistically (Yokoyama and Gruss, 2013). A major problem is that during mitosis the putative role of exportin mediated interactions may be difficult to untangle from that of importin mediated interactions, as they involve proteins having both NES and NLS [i.e., Pericentrin (Liu et al., 2010)]. Nevertheless, it seems evident that the RanGTP regulation of CRM1 has several roles during mitosis and it will be interesting to test whether other exportins are also important for mitotic events.

Conservation of the RanGTP pathway in dividing cells

In the last 15 years the RanGTP pathway has been studied in several organisms and cell types. It was found to present variations on some details or in some cases to be unnecessary. Indeed, in some meiotic systems the contribution of the RanGTP pathway appears to be non-essential. For instance, Drosophila spermatocytes can assemble the meiosis I spindle in the complete absence of chromosomes (Bucciarelli et al., 2003). The assembly of the acentrosomal spindle of meiosis I in mice and frogs oocytes was also shown to be only partially dependent on the RanGTP pathway, although the pathway is strictly essential for spindle assembly during meiosis II (Dumont et al., 2007).

Even in systems relying on RanGTP for spindle assembly there are some variations at least at the level of the machinery. For instance, TPX2, which is essential in frogs and mammals, is not present in Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster. Although proteins with some of the TPX2 characteristics have been identified in these systems (Ozlu et al., 2005; Goshima, 2011), they lack essential features of TPX2, like an NLS that is at the basis of the RanGTP regulation. This example indicates that the effectors of the RanGTP pathway might vary from system to system, although the main principles are probably maintained and conserved.

The RanGTP pathway: a moonlighting pathway with a role in several cellular functions

The RanGTP pathway is an example of a whole pathway that accomplishes essential functions in different parts of the cell cycle. In interphase, it orchestrates the nucleo-cytoplasmic transport, while in mitosis it drives spindle assembly and later nuclear membrane and NPC reassembly (Figures 1B–D). Individual proteins that have different functions at different times are defined as moonlighting proteins (Jeffery, 1999). The RanGTP pathway could therefore be an example of a moonlighting pathway.

The RanGTP pathway is particularly interesting, because it shows how the function of a protein depends on its context: most of the SAFs have nuclear functions and are kept separated from tubulins and others cytoskeleton proteins during interphase. Upon NEBD, the general context changes and the SAFs exert important functions related to the MTs.

Some data point toward a moonlighting function of the RanGTP pathway in cilia formation and in transport into the cilium. RanGTP has been shown to control the accumulation of Kif17 and retinis pigmentosa 2 to the cilioplasm (Dishinger et al., 2010; Hurd et al., 2011), where RanGTP is concentrated (Fan et al., 2011). The current working model is that the RanGTP pathway orchestrates the transport of cargos carrying a cilia localization signal through the cilia pore complex, which has been proposed to be located at the base of the cilium (Kee et al., 2012; Figure 1E). However, further studies are needed to understand how the RanGTP gradient is established in cilia and what other cargos it transports into the cilia.

Interestingly, the RanGTP pathway moonlights also in differentiated neurons, where many SAFs also have a function [TPX2, MCRS1, NuMa, Rae1, HSET (Ferhat et al., 1998; Davidovic et al., 2006; Mori et al., 2009; Tian et al., 2011; Pannu et al., 2015)]. Furthermore importins α and β accumulate at the dendritic synaptic space and have a role in the transport of cargos from the synapses to the nucleus (Jordan and Kreutz, 2009; Panayotis et al., 2015). Finally, a RanGTP regulated mechanism has been shown to be at play in response to sciatic nerve injuries (Hanz et al., 2003; Yudin et al., 2008; Figure 1F).

Conclusions

The identification of the role played by the RanGTP pathway during cell division occurred more than 15 years ago. We know now that the RanGTP pathway has additional functions and could be considered a moonlighting pathway controlling various important cellular processes (Figure 1). During cell division it drives essential mechanisms that we start to understand thanks to the identification and functional characterization of its direct targets. However, several open questions still need to be addressed. The total number of SAFs is difficult to anticipate and therefore we do not know how many still remain to be identified. Furthermore, most of our current knowledge is restricted to the role of only some components of the nucleo-cytoplasmic transport machinery. For instance, very little is currently known about the putative role in cell division of the different importins present in the human cell. Specific importins may regulate the activity of novel SAFs and their different expression patterns in different cell types and tissues may provide a relevant combinatorial mechanism. We also know little on the putative role of the components of the export machinery in spindle assembly and in the other novel functions of the pathway. Although, there are data suggesting various points of regulation of the pathway itself, the consequences on cell division and other processes are not clear yet, nor how it may be adapted to the requirements of different cell types or tissues. The study of the RanGTP pathway will certainly provide exciting new insights in the next few years, revealing some essential mechanisms for cell organization and function.

Author contributions

IV and TC wrote the manuscript, TC prepared the table and figure.

Funding

TC was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (MINECO) through the FPI fellowship BES-2010-031355. Work in the Vernos lab was supported by the Spanish ministry grants BFU2009-10202 and BFU2012-37163, co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF/FEDER). We also acknowledge support of the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, “Centro de Excelencia Severo Ochoa 2013-2017,” SEV-2012-0208.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the members of Vernos lab for critical discussions on the various aspects of the RanGTP pathway.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- γTuRC

γTubulin Ring Complex

- K-Fiber

Kinetochore-Fiber

- KANLS

KAT8-associated nonspecific lethal complex

- MT

Microtubule

- NEBD

Nuclear Envelope Breakdown

- NES

Nuclear Export Signal

- NLS

Nuclear Localization Signal

- NPC

Nuclear Pore Complex

- NTR

Nuclear Transport Receptor

- RanGAP

Ran GTPase Activating Protein

- RanGEF

Ran Guanine nucleotide Exchange Factor

- SAF

Spindle Assembly Factor.

References

- Abad P. C., Lewis J., Mian I. S., Knowles D. W., Sturgis J., Badve S., et al. (2007). NuMA influences higher order chromatin organization in human mammary epithelium. Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 348–361. 10.1091/mbc.E06-06-0551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam S. A., Sengupta K., Goldman R. D. (2008). Regulation of nuclear lamin polymerization by importin alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 8462–8468. 10.1074/jbc.M709572200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S. M., Theriault B. L., Uppalapati M., Chiu C. W. N., Gallie B. L., Sidhu S. S., et al. (2012). KIF14 negatively regulates Rap1a-Radil signaling during breast cancer progression. J. Cell Biol. 199, 951–967. 10.1083/jcb.201206051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albee A. J., Tao W., Wiese C. (2006). Phosphorylation of maskin by Aurora-A is regulated by RanGTP and importin beta. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 38293–38301. 10.1074/jbc.M607203200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaoutov A., Azuma Y., Ribbeck K., Joseph J., Boyarchuk Y., Karpova T., et al. (2005). Crm1 is a mitotic effector of Ran-GTP in somatic cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 626–632. 10.1038/ncb1263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beenders B., Jones P. L., Bellini M. (2007). The tripartite Motif of nuclear factor 7 is required for its association with transcriptional units. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 2615–2624. 10.1128/MCB.01968-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernis C., Swift-Taylor B., Nord M., Carmona S., Chook Y. M., Forbes D. J. (2014). Transportin acts to regulate mitotic assembly events by target binding rather than Ran sequestration. Mol. Biol. Cell 25, 992–1009. 10.1091/mbc.E13-08-0506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blower M. D., Nachury M., Heald R., Weis K. (2005). A Rae1-containing ribonucleoprotein complex is required for mitotic spindle assembly. Cell 121, 223–234. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie K. M., Henderson B. R. (2012). Characterization of BRCA1 protein targeting, dynamics, and function at the centrosome: a role for the nuclear export signal, CRM1, and Aurora A kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 7701–7716. 10.1074/jbc.M111.327296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucciarelli E., Giansanti M. G., Bonaccorsi S., Gatti M. (2003). Spindle assembly and cytokinesis in the absence of chromosomes during Drosophila male meiosis. J. Cell Biol. 160, 993–999. 10.1083/jcb.200211029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carazo-Salas R. E., Gruss O. J., Mattaj I. W., Karsenti E. (2001). Ran-GTP coordinates regulation of microtubule nucleation and dynamics during mitotic-spindle assembly. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 228–234. 10.1038/35060009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carazo-Salas R. E., Guarguaglini G., Gruss O. J., Segref A., Karsenti E., Mattaj I. W. (1999). Generation of GTP-bound Ran by RCC1 is required for chromatin-induced mitotic spindle formation. Nature 400, 178–181. 10.1038/22133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carleton M., Mao M., Biery M., Warrener P., Kim S., Buser C., et al. (2006). RNA interference-mediated silencing of mitotic Kinesin KIF14 disrupts cell cycle progression and induces cytokinesis failure. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 3853–3863. 10.1128/MCB.26.10.3853-3863.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casaletto J. B. (2005). Inhibition of the anaphase-promoting complex by the Xnf7 ubiquitin ligase. J. Cell Biol. 169, 61–71. 10.1083/jcb.200411056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudron M., Bunt G., Bastiaens P., Karsenti E. (2005). Spatial coordination of spindle assembly by chromosome-mediated signaling gradients. Science 309, 1373–1376. 10.1126/science.1115964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cautain B., Hill R., de Pedro N., Link W. (2015). Components and regulation of nuclear transport processes. FEBS J. 282, 445–462. 10.1111/febs.13163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciciarello M., Mangiacasale R., Lavia P. (2007). Spatial control of mitosis by the GTPase Ran. Cell Mol. Life Sci 64, 1891–1914. 10.1007/s00018-007-6568-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciciarello M., Roscioli E., Di Fiore B., Di Francesco L., Sobrero F., Bernard D., et al. (2010). Nuclear reformation after mitosis requires downregulation of the Ran GTPase effector RanBP1 in mammalian cells. Chromosoma 119, 651–668. 10.1007/s00412-010-0286-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke P., Zhang R. C. (2008). Spatial and temporal coordination of mitosis by Ran GTPase. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 464–477. 10.1038/nrm2410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton D. A., Cleveland D. W. (1993). NuMA is required for the proper completion of mitosis. J. Cell Biol. 120, 947–957. 10.1083/jcb.120.4.947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross M. K., Powers M. A. (2011). Nup98 regulates bipolar spindle assembly through association with microtubules and opposition of MCAK. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 661–672. 10.1091/mbc.E10-06-0478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidovic L., Bechara E., Gravel M., Jaglin X. H., Tremblay S., Sik A., et al. (2006). The nuclear microspherule protein 58 is a novel RNA-binding protein that interacts with fragile X mental retardation protein in polyribosomal mRNPs from neurons. Hum. Mol. Genet. 15, 1525–1538. 10.1093/hmg/ddl074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debec A., Detraves C., Montmory C., Geraud G., Wright M. (1995). Polar organization of gamma-tubulin in acentriolar mitotic spindles of Drosophila melanogaster cells. J. Cell Sci. 108(Pt 7), 2645–2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Brabander M., Geuens G., De Mey J., Joniau M. (1981). Nucleated assembly of mitotic microtubules in living PTK2 cells after release from nocodazole treatment. Cell Motil. 1, 469–483. 10.1002/cm.970010407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellaire G., Farrall R., Bickmore W. A. (2003). The Nuclear Protein Database (NPD): sub-nuclear localisation and functional annotation of the nuclear proteome. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 328–330. 10.1093/nar/gkg018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikovskaya D., Khoudoli G., Newton I. P., Chadha G. S., Klotz D., Visvanathan A., et al. (2012). The adenomatous polyposis coli protein contributes to normal compaction of mitotic chromatin. PLoS ONE 7:e38102–38113. 10.1371/journal.pone.0038102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikovskaya D., Li Z., Newton I. P., Davidson I., Hutchins J. R. A., Kalab P., et al. (2010). Microtubule assembly by the Apc protein is regulated by importin-ß-RanGTP. J. Cell Sci. 123, 736–746. 10.1242/jcs.060806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikovskaya D., Newton I. P., Nthke I. S. (2004). The adenomatous polyposis coli protein is required for the formation of robust spindles formed in CSF Xenopus extracts. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 2978–2991. 10.1091/mbc.E03-08-0613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikovskaya D., Zumbrunn J., Penman G. A., Nathke I. S. (2001). The adenomatous polyposis coli protein: in the limelight out at the edge. Trends Cell Biol. 11, 378–384. 10.1016/S0962-8924(01)02069-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishinger J. F., Kee H. L., Jenkins P. M., Fan S., Hurd T. W., Hammond J. W., et al. (2010). Ciliary entry of the kinesin-2 motor KIF17 is regulated by importin-beta2 and RanGTP. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 703–710. 10.1038/ncb2073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont J., Petri S., Pellegrin F., Terret M. E., Bohnsack M. T., Rassinier P., et al. (2007). A centriole- and RanGTP-independent spindle assembly pathway in meiosis I of vertebrate oocytes. J. Cell Biol. 176, 295–305. 10.1083/jcb.200605199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagleson G., Pfister K., Knowlton A. L., Skoglund P., Keller R., Stukenberg P. T. (2015). Kif2a depletion generates chromosome segregation and pole coalescence defects in animal caps and inhibits gastrulation of the Xenopus embryo. Mol. Biol. Cell 26, 924–937. 10.1091/mbc.E13-12-0721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ems-McClung S. C., Zheng Y., Walczak C. E. (2004). Importin alpha/beta and Ran-GTP regulate XCTK2 microtubule binding through a bipartite nuclear localization signal. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 46–57. 10.1091/mbc.E03-07-0454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin L. D., el-Hodiri H. M., Nakamura H., Wu C. F., Shou W., Gong S. G. (1997). Characterization and function of Xnf7 during early development of Xenopus. J. Cell. Physiol. 173, 144–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan S., Fogg V., Wang Q., Chen X.-W., Liu C.-J., Margolis B. (2007). A novel Crumbs3 isoform regulates cell division and ciliogenesis via importin beta interactions. J. Cell Biol. 178, 387–398. 10.1083/jcb.200609096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan S., Whiteman E. L., Hurd T. W., McIntyre J. C., Dishinger J. F., Liu C. J., et al. (2011). Induction of Ran GTP drives ciliogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 4539–4548. 10.1091/mbc.E11-03-0267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina F., Pierobon P., Delevoye C., Monnet J., Dingli F., Loew D., et al. (2013). Kinesin KIFC1 actively transports bare double-stranded DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 4926–4937. 10.1093/nar/gkt204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferhat L., Cook C., Kuriyama R., Baas P. W. (1998). The nuclear/mitotic apparatus protein NuMA is a component of the somatodendritic microtubule arrays of the neuron. J. Neurocytol. 27, 887–899. 10.1023/A:1006949006728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field C. M., Alberts B. M. (1995). Anillin, a contractile ring protein that cycles from the nucleus to the cell cortex. J. Cell Biol. 131, 165–178. 10.1083/jcb.131.1.165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes D. J., Travesa A., Nord M. S., Bernis C. (2015). Reprint of “Nuclear transport factors: global regulation of mitosis”. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 34, 122–134. 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaglio T., Saredi A., Compton D. A. (1995). NuMA is required for the organization of microtubules into aster-like mitotic arrays. J. Cell Biol. 131, 693–708. 10.1083/jcb.131.3.693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garriga-Canut M., Orkin S. H. (2004). Transforming Acidic Coiled-coil Protein 3 (TACC3) Controls Friend of GATA-1 (FOG-1) subcellular localization and regulates the association between GATA-1 and FOG-1 during Hematopoiesis. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 23597–23605. 10.1074/jbc.M313987200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gergely F., Kidd D., Jeffers K., Wakefield J. G., Raff J. W. (2000). D-TACC: a novel centrosomal protein required for normal spindle function in the early Drosophila embryo. EMBO J. 19, 241–252. 10.1093/emboj/19.2.241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshima G. (2011). Identification of a TPX2-Like Microtubule-Associated Protein in Drosophila. PLoS ONE 6:e28120. 10.1371/journal.pone.0028120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruss O. J., Carazo-Salas R. E., Schatz C. A., Guarguaglini G., Kast J., Wilm M., et al. (2001). Ran induces spindle assembly by reversing the inhibitory effect of importin alpha on TPX2 activity. Cell 104, 83–93. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00193-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Partch C. L., Key J., Card P. B., Pashkov V., Patel A., et al. (2013). Regulating the ARNT/TACC3 axis: multiple approaches to manipulating protein/protein interactions with small molecules. ACS Chem. Biol. 8, 626–635. 10.1021/cb300604u [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanz S., Perlson E., Willis D., Zheng J. Q., Massarwa R., Huerta J. J., et al. (2003). Axoplasmic importins enable retrograde injury signaling in lesioned nerve. Neuron 40, 1095–1104. 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00770-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harel A., Chan R. C., Lachish-Zalait A., Zimmerman E., Elbaum M., Forbes D. J. (2003). Importin beta negatively regulates nuclear membrane fusion and nuclear pore complex assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 4387–4396. 10.1091/mbc.E03-05-0275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa K., Ryu S. J., Kalab P. (2013). Chromosomal gain promotes formation of a steep RanGTP gradient that drives mitosis in aneuploid cells. J. Cell Biol. 200, 151–161. 10.1083/jcb.201206142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heald R., Tournebize R., Blank T., Sandaltzopoulos R., Becker P., Hyman A., et al. (1996). Self-organization of microtubules into bipolar spindles around artificial chromosomes in Xenopus egg extracts. Nature 382, 420–425. 10.1038/382420a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood F. E., Clarke P. R. (2007). RCC1 isoforms differ in their affinity for chromatin, molecular interactions and regulation by phosphorylation. J. Cell Sci. 120, 3436–3445. 10.1242/jcs.009092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa K., Nishi M., Sakamoto H., Tanaka Y., Kawata M. (2008). Regional distribution of importin subtype mRNA expression in the nervous system: Study of early postnatal and adult mouse. Neuroscience 157, 864–877. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.09.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd T. W., Fan S., Margolis B. L. (2011). Localization of retinitis pigmentosa 2 to cilia is regulated by Importin beta2. J. Cell Sci. 124, 718–726. 10.1242/jcs.070839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery C. J. (1999). Moonlighting proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24, 8–11. 10.1016/S0968-0004(98)01335-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan B. A., Kreutz M. R. (2009). Nucleocytoplasmic protein shuttling: the direct route in synapse-to-nucleus signaling. Trends Neurosci. 32, 392–401. 10.1016/j.tins.2009.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalab P., Heald R. (2008). The RanGTP gradient - a GPS for the mitotic spindle. J. Cell Sci. 121, 1577–1586. 10.1242/jcs.005959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalab P., Pralle A., Isacoff E. Y., Heald R., Weis K. (2006). Analysis of a RanGTP-regulated gradient in mitotic somatic cells. Nature 440, 697–701. 10.1038/nature04589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalab P., Pu R. T., Dasso M. (1999). The ran GTPase regulates mitotic spindle assembly. Curr. Biol. 9, 481–484. 10.1016/S0960-9822(99)80213-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalab P., Weis K., Heald R. (2002). Visualization of a Ran-GTP gradient in interphase and mitotic Xenopus egg extracts. Science 295, 2452–2456. 10.1126/science.1068798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsenti E., Newport J., Kirschner M. W. (1984). Respective roles of centrosomes and chromatin in the conversion of microtubule arrays from interphase to metaphase. J. Cell Biol. 99, 47s–54s. 10.1083/jcb.99.1.47s [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsenti E., Vernos I. (2001). The mitotic spindle: a self-made machine. Science 294, 543–547. 10.1126/science.1063488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kee H. L., Dishinger J. F., Blasius T. L., Liu C. J., Margolis B., Verhey K. J. (2012). A size-exclusion permeability barrier and nucleoporins characterize a ciliary pore complex that regulates transport into cilia. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 431–437. 10.1038/ncb2450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodjakov A. L., Cole R. W., Oakley B. R., Rieder C. L. (2000). Centrosome-independent mitotic spindle formation in vertebrates. Curr. Biol. 10, 59–67. 10.1016/S0960-9822(99)00276-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner M. W., Mitchison T. J. (1986). Beyond self-assembly: from microtubules to morphogenesis. Cell 45, 329–342. 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90318-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyomitsu T., Cheeseman I. M. (2012). Chromosome- and spindle-pole-derived signals generate an intrinsic code for spindle position and orientation. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 311–317. 10.1038/ncb2440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyomitsu T., Cheeseman I. M. (2013). Cortical Dynein and Asymmetric Membrane elongation coordinately position the spindle in anaphase. Cell 154, 391–402. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knauer S. K., Bier C., Habtemichael N., Stauber R. H. (2006). The Survivin-Crm1 interaction is essential for chromosomal passenger complex localization and function. EMBO Rep. 7, 1259–1265. 10.1038/sj.embor.7400824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffa M. D., Casanova C. M., Santarella R., Kcher T., Wilm M., Mattaj I. W. (2006). HURP is part of a Ran-dependent complex involved in spindle formation. Curr. Biol. 16, 743–754. 10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laprise P., Viel A., Rivard N. (2004). Human Homolog of Disc-large Is required for adherens junction assembly and differentiation of human intestinal epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 10157–10166. 10.1074/jbc.M309843200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau C. K., Delmar V. A., Chan R. C., Phung Q., Bernis C., Fichtman B., et al. (2009). Transportin regulates major mitotic assembly events: from spindle to nuclear pore assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 4043–4058. 10.1091/mbc.E09-02-0152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. Y., Ng W. P., Wong C. H., Iglesias P. A., Zheng Y. (2007). Coordination of chromosome alignment and mitotic progression by the chromosome-based Ran signal. Cell Cycle 6, 1886–1895. 10.4161/cc.6.15.4487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Shiraki T., Igarashi K. (2012). Transcription-independent role of Bach1 in mitosis through a nuclear exporter Crm1-dependent mechanism. FEBS Lett. 586, 448–454. 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.01.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Jiang Q., Zhang C. (2009). A fraction of Crm1 locates at centrosomes by its CRIME domain and regulates the centrosomal localization of pericentrin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 384, 383–388. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.04.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Yu J., Zhuo X., Jiang Q., Zhang C. (2010). Pericentrin contains five NESs and an NLS essential for its nucleocytoplasmic trafficking during the cell cycle. Cell Res. 20, 948–962. 10.1038/cr.2010.89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malumbres M. (2014). Cyclin-dependent kinases. Genome Biol. 15, 122. 10.1186/gb4184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maor-Nof M., Homma N., Raanan C., Nof A., Hirokawa N., Yaron A. (2013). Axonal pruning is actively regulated by the microtubule-destabilizing protein kinesin superfamily protein 2A. Cell Rep. 3, 971–977. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maresca T. J., Niederstrasser H., Weis K., Heald R. (2005). Xnf7 contributes to spindle integrity through its microtubule-bundling activity. Curr. Biol. 15, 1755–1761. 10.1016/j.cub.2005.08.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill M., Brinkley B. R. (1975). Human chromosomes and centrioles as nucleating sites for the in vitro assembly of microtubules from bovine brain tubulin. J. Cell Biol. 67, 189–199. 10.1083/jcb.67.1.189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier S., Shvedunova M., Van Nguyen N., Avila L., Vernos I., Akhtar A. (2015). An epigenetic regulator emerges as microtubule minus-end binding and stabilizing factor in mitosis. Nat Commun 6, 7889. 10.1038/ncomms8889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier S., Vernos I. (2011). K-fibre minus ends are stabilized by a RanGTP-dependent mechanism essential for functional spindle assembly. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 1406–1414. 10.1038/ncb2372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier S., Vernos I. (2012). Microtubule assembly during mitosis - from distinct origins to distinct functions? J. Cell Sci. 125, 2805–2814. 10.1242/jcs.092429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra R. K., Chakraborty P., Arnaoutov A., Fontoura B. M. A., Dasso M. (2010). The Nup107-160 complex and gamma-TuRC regulate microtubule polymerization at kinetochores. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 164–169. 10.1038/ncb2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto T., Hosoba K., Ochiai H., Royba E., Izumi H., Sakuma T., et al. (2015). The microtubule-depolymerizing activity of a mitotic kinesin protein KIF2A drives primary cilia disassembly coupled with cell proliferation. Cell Rep. 10, 664–673. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori D., Yamada M., Mimori-Kiyosue Y., Shirai Y., Suzuki A., Ohno S., et al. (2009). An essential role of the aPKC-Aurora A-NDEL1 pathway in neurite elongation by modulation of microtubule dynamics. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 1057–1068. 10.1038/ncb1919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachury M. V., Maresca T. J., Salmon W. C., Waterman-Storer C. M., Heald R., Weis K. (2001). Importin beta is a mitotic target of the small GTPase Ran in spindle assembly. Cell 104, 95–106. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00194-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nath S., Bananis E., Sarkar S., Stockert R. J., Sperry A. O., Murray J. W., et al. (2007). Kif5B and Kifc1 interact and are required for motility and fission of early endocytic vesicles in mouse liver. Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 1839–1849. 10.1091/mbc.E06-06-0524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumayer G., Belzil C., Gruss O. J., Nguyen M. D. (2014). TPX2: of spindle assembly, DNA damage response, and cancer. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 71, 3027–3047. 10.1007/s00018-014-1582-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nwagbara B. U., Faris A. E., Bearce E. A., Erdogan B., Ebbert P. T., Evans M. F., et al. (2014). TACC3 is a microtubule plus end-tracking protein that promotes axon elongation and also regulates microtubule plus end dynamics in multiple embryonic cell types. Mol. Biol. Cell 25, 3350–3362. 10.1091/mbc.E14-06-1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell C. B., Khodjakov A. L. (2007). Cooperative mechanisms of mitotic spindle formation. J. Cell Sci. 120, 1717–1722. 10.1242/jcs.03442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohba T., Nakamura M., Nishitani H., Nishimoto T. (1999). Self-organization of microtubule asters induced in Xenopus egg extracts by GTP-bound Ran. Science 284, 1356–1358. 10.1126/science.284.5418.1356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orjalo A. V., Arnaoutov A., Shen Z., Boyarchuk Y., Zeitlin S. G., Fontoura B., et al. (2006). The Nup107-160 nucleoporin complex is required for correct bipolar spindle assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 3806–3818. 10.1091/mbc.E05-11-1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshaughnessy A., Hendrich B. (2013). CHD4 in the DNA-damage response and cell cycle progression: not so NuRDy now. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 41, 777–782. 10.1042/BST20130027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osmanagic-Myers S., Dechat T., Foisner R. (2015). Lamins at the crossroads of mechanosignaling. Genes Dev. 29, 225–237. 10.1101/gad.255968.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozlu N., Srayko M., Kinoshita K., Habermann B. T., O'Toole E., Muller-Reichert T., et al. (2005). An essential function of the C. elegans ortholog of TPX2 is to localize activated aurora A kinase to mitotic spindles. Dev. Cell 9, 237–248. 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panayotis N., Karpova A., Kreutz M. R., Fainzilber M. (2015). Macromolecular transport in synapse to nucleus communication. Trends Neurosci. 38, 108–116. 10.1016/j.tins.2014.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannu V., Rida P. C. G., Aneja R. (2015). The human Kinesin-14 motor KifC1/HSET is an attractive anti-cancer drug target, in Kinesins and Cancer, eds Kozielski F. S., Skoufias D. A. (Dordrecht: Springer; ), 101–116. Available online at: http://link.springer.com/book/10.1007%2F978-94-017-9732-0 [Google Scholar]

- Perchiniak E. M., Groden J. (2011). Mechanisms regulating microtubule binding, DNA replication, and apoptosis are controlled by the intestinal tumor suppressor APC. Curr. Colorectal Cancer Rep. 7, 145–151. 10.1007/s11888-011-0088-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peset I., Seiler J., Sardon T., Bejarano L. A., Rybina S., Vernos I. (2005). Function and regulation of Maskin, a TACC family protein, in microtubule growth during mitosis. J. Cell Biol. 170, 1057–1066. 10.1083/jcb.200504037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petretti C., Savoian M., Montembault E., Glover D. M., Prigent C., Giet R. (2006). The PITSLRE/CDK11p58 protein kinase promotes centrosome maturation and bipolar spindle formation. EMBO Rep. 7, 418–424. 10.1038/sj.embor.7400639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platani M., Santarella-Mellwig R., Posch M., Walczak R., Swedlow J. R., Mattaj I. W. (2009). The Nup107-160 nucleoporin complex promotes mitotic events via control of the localization state of the chromosome passenger complex. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 5260–5275. 10.1091/mbc.E09-05-0377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard C. E., Fornerod M., Kasper L. H., van Deursen J. M. (1999). RAE1 is a shuttling mRNA export factor that binds to a GLEBS-like NUP98 motif at the nuclear pore complex through multiple domains. J. Cell Biol. 145, 237–254. 10.1083/jcb.145.2.237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radulescu A. E., Cleveland D. W. (2010). NuMA after 30 years: the matrix revisited. Trends Cell Biol. 20, 214–222. 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raemaekers T. (2003). NuSAP, a novel microtubule-associated protein involved in mitotic spindle organization. J. Cell Biol. 162, 1017–1029. 10.1083/jcb.200302129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raja S. J., Charapitsa I., Conrad T., Vaquerizas J. M., Gebhardt P., Holz H., et al. (2010). The nonspecific lethal complex is a transcriptional regulator in Drosophila. Mol. Cell 38, 827–841. 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasala B. A., Orjalo A. V., Shen Z., Briggs S., Forbes D. J. (2006). ELYS is a dual nucleoporin/kinetochore protein required for nuclear pore assembly and proper cell division. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 17801–17806. 10.1073/pnas.0608484103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribbeck K., Groen A. C., Santarella R., Bohnsack M. T., Raemaekers T., Kcher T., et al. (2006). NuSAP, a mitotic RanGTP target that stabilizes and cross-links microtubules. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 2646–2660. 10.1091/mbc.E05-12-1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribbeck K., Raemaekers T., Carmeliet G., Mattaj I. W. (2007). A role for NuSAP in linking microtubules to mitotic chromosomes. Curr. Biol. 17, 230–236. 10.1016/j.cub.2006.11.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieder C. L. (2005). Kinetochore fiber formation in animal somatic cells: dueling mechanisms come to a draw. Chromosoma 114, 310–318. 10.1007/s00412-005-0028-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscioli E., Bolognesi A., Guarguaglini G., Lavia P. (2010). Ran control of mitosis in human cells: gradients and local signals. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 38, 1709–1714. 10.1042/BST0381709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samwer M., Dehne H.-J., Spira F., Kollmar M., Gerlich D. W., Urlaub H., et al. (2013). The nuclear F-actin interactome of Xenopus oocytes reveals an actin-bundling kinesin that is essential for meiotic cytokinesis. EMBO J. 32, 1886–1902. 10.1038/emboj.2013.108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scrofani J., Sardon T., Meunier S., Vernos I. (2015). Microtubule nucleation in Mitosis by a RanGTP-dependent protein complex. Curr. Biol. 25, 131–140. 10.1016/j.cub.2014.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimono K., Shimono Y., Shimokata K., Ishiguro N., Takahashi M. (2005). Microspherule protein 1, Mi-2beta, and RET finger protein associate in the nucleolus and up-regulate ribosomal gene transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 39436–39447. 10.1074/jbc.M507356200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silkworth W. T., Nardi I. K., Paul R., Amogilner A., Cimini D. (2012). Timing of centrosome separation is important for accurate chromosome segregation. Mol. Biol. Cell 23, 401–411. 10.1091/mbc.E11-02-0095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillje H. H., Nagel S., Korner R., Nigg E. A. (2006). HURP is a Ran-importin beta-regulated protein that stabilizes kinetochore microtubules in the vicinity of chromosomes. Curr. Biol. 16, 731–742. 10.1016/j.cub.2006.02.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman-Gavrila R. V., Hales K. G., Wilde A. (2008). Anillin-mediated targeting of peanut to pseudocleavage furrows is regulated by the GTPase Ran. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 3735–3744. 10.1091/mbc.E08-01-0049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinnott R., Winters L., Larson B., Mytsa D., Taus P., Cappell K. M., et al. (2014). Mechanisms promoting escape from mitotic stress-induced tumor cell death. Cancer Res. 74, 3857–3869. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorokin A. V., Kim E. R., Ovchinnikov L. P. (2007). Nucleocytoplasmic transport of proteins. Biochemistry 72, 1439–1457. 10.1134/S0006297907130032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley F. K. T., Moore S., Goodarzi A. A. (2013). CHD chromatin remodelling enzymes and the DNA damage response. Mutat. Res. 750, 31–44. 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2013.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stebbins-Boaz B., Cao Q., de Moor C. H., Mendez R., Richter J. D. (1999). Maskin is a CPEB-associated factor that transiently interacts with elF-4E. Mol. Cell 4, 1017–1027. 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80230-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahara K., Takagi M., Ohsugi M., Sone T., Nishiumi F., Maeshima K., et al. (2008). Importin-β and the small guanosine triphosphatase Ran mediate chromosome loading of the human chromokinesin Kid. J. Cell Biol. 180, 493–506. 10.1083/jcb.200708003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telzer B. R., Moses M. J., Rosenbaum J. L. (1975). Assembly of microtubules onto kinetochores of isolated mitotic chromosomes of HeLa cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 72, 4023–4027. 10.1073/pnas.72.10.4023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian X., Li J., Valakh V., DiAntonio A., Wu C. (2011). Drosophila Rae1 controls the abundance of the ubiquitin ligase Highwire in post-mitotic neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 1267–1275. 10.1038/nn.2922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokai N., Fujimoto-Nishiyama A., Toyoshima Y., Yonemura S., Tsukita S., Inoue J., et al. (1996). Kid, a novel kinesin-like DNA binding protein, is localized to chromosomes and the mitotic spindle. EMBO J. 15, 457–467. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toto M., Dangelo G., Corona D. F. V. (2014). Regulation of ISWI chromatin remodelling activity. Chromosoma 123, 91–102. 10.1007/s00412-013-0447-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai M.-Y., Wang S., Heidinger J. M., Shumaker D. K., Adam S. A., Goldman R. D., et al. (2006). A mitotic lamin B matrix induced by RanGTP required for spindle assembly. Science 311, 1887–1893. 10.1126/science.1122771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsou A.-P., Yang C.-W., Huang C.-Y. F., Yu R. C. T., Lee Y.-C. G., Chang C.-W., et al. (2003). Identification of a novel cell cycle regulated gene, HURP, overexpressed in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene 22, 298–307. 10.1038/sj.onc.1206129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidi P. A., Liu J., Salles D., Jayaraman S., Dorfman G., Gray M., et al. (2014). NuMA promotes homologous recombination repair by regulating the accumulation of the ISWI ATPase SNF2h at DNA breaks. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 6365–6379. 10.1093/nar/gku296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walczak C. E., Verma S., Mitchison T. J. (1997). XCTK2: a kinesin-related protein that promotes mitotic spindle assembly in Xenopus laevis egg extracts. J. Cell Biol. 136, 859–870. 10.1083/jcb.136.4.859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther T. C, Askjaer P., Gentzel M., Habermann A., Griffiths G., Wilm M., et al. (2003). RanGTP mediates nuclear pore complex assembly. Nature 424, 689–694. 10.1038/nature01898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S., Peterson C. L. (2010). The INO80 family of chromatin-remodeling enzymes: regulators of histone variant dynamics. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 75, 35–42. 10.1101/sqb.2010.75.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J. H., Zhang Z. C., Wynn R. M., Seemann J. (2015). GM130 Regulates Golgi-derived spindle assembly by activating TPX2 and capturing microtubules. Cell 162, 287–299. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese C. (2001). Role of importin-beta in coupling Ran to downstream targets in microtubule assembly. Science 291, 653–656. 10.1126/science.1057661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese C., Wilde A., Moore M. S., Adam S. A., Merdes A., Zheng Y. (2001). Role of importin-beta in coupling Ran to downstream targets in microtubule assembly. Science 291, 653–656. 10.1126/science.1057661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilbur J. D., Heald R. (2013). Mitotic spindle scaling during Xenopus development by kif2a and importin α. eLife 2:e00290. 10.7554/eLife.00290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilde A., Zheng Y. (1999). Stimulation of microtubule aster formation and spindle assembly by the small GTPase Ran. Science 284, 1359–1362. 10.1126/science.284.5418.1359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt P. L., Ris H., Borisy G. G. (1980). Origin of kinetochore microtubules in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Chromosoma 81, 483–505. 10.1007/BF00368158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann T., Wilm M., Karsenti E., Vernos I. (2000). TPX2, A novel xenopus MAP involved in spindle pole organization. J. Cell Biol. 149, 1405–1418. 10.1083/jcb.149.7.1405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollman R., Cytrynbaum E. N., Jones J. T., Meyer T., Scholey J. M., Amogilner A. (2005). Efficient chromosome capture requires a bias in the 'search-and-capture' process during mitotic-spindle assembly. Curr. Biol. 15, 828–832. 10.1016/j.cub.2005.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong R. W., Blobel G., Coutavas E. (2006). Rae1 interaction with NuMA is required for bipolar spindle formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 19783–19787. 10.1073/pnas.0609582104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z., Jiang Q., Clarke P. R., Zhang C. (2013). Phosphorylation of Crm1 by CDK1-cyclin-B promotes Ran-dependent mitotic spindle assembly. J. Cell Sci. 126, 3417–3428. 10.1242/jcs.126854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuhr M., Freeman R. M., Jr., Presler M., Horb M. E., Peshkin L., Gygi S. P., et al. (2014). Deep proteomics of the Xenopus laevis Egg using an mRNA-Derived reference database. Curr. Biol. 24, 1467–1475. 10.1016/j.cub.2014.05.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama H., Gruss O. J. (2013). New mitotic regulators released from chromatin. Front. Oncol. 3:308. 10.3389/fonc.2013.00308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama H., Gruss O. J., Rybina S., Caudron M., Schelder M., Wilm M., et al. (2008). Cdk11 is a RanGTP-dependent microtubule stabilization factor that regulates spindle assembly rate. J. Cell Biol. 180, 867–875. 10.1083/jcb.200706189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama H., Koch B., Walczak R., Duygu F. C., González-Sánchez J. C., Devos D. P., et al. (2014). The nucleoporin MEL-28 promotes RanGTP-dependent \γ-tubulin recruitment and microtubule nucleation in mitotic spindle formation. Nat. Commun. 5, 1–9. 10.1038/ncomms4270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama H., Nakos K., Santarella-Mellwig R., Rybina S., Krijgsveld J., Koffa M. D., et al. (2013). CHD4 Is a RanGTP-Dependent MAP that Stabilizes microtubules and regulates bipolar spindle formation. Curr. Biol. 23, 2443–2451. 10.1016/j.cub.2013.09.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama H., Rybina S., Santarella-Mellwig R., Mattaj I. W., Karsenti E. (2009). ISWI is a RanGTP-dependent MAP required for chromosome segregation. J. Cell Biol. 187, 813–829. 10.1083/jcb.200906020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yudin D., Hanz S., Yoo S., Iavnilovitch E., Willis D., Gradus T., et al. (2008). Localized regulation of Axonal RanGTPase controls retrograde injury signaling in peripheral nerve. Neuron 59, 241–252. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.05.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng C., He D., Berget S. M., Brinkley B. R. (1994). Nuclear-mitotic apparatus protein: a structural protein interface between the nucleoskeleton and RNA splicing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 1505–1509. 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Hughes M., Clarke P. R. (1999). Ran-GTP stabilises microtubule asters and inhibits nuclear assembly in Xenopus egg extracts. J. Cell Sci. 112 (Pt 14), 2453–2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C., Zhao J., Bibikova M., Leverson J. D., Bossy-Wetzel E., Fan J.-B., et al. (2005). Functional analysis of human microtubule-based motor proteins, the kinesins and dyneins, in mitosis/cytokinesis using RNA interference. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 3187–3199. 10.1091/mbc.E05-02-0167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]