Genome-wide determination of maize transcription initiation sites reveals the prevalence of sharp promoters and underscores the role of alternate initiation as a determinant of protein function and localization.

Abstract

Core promoters are crucial for gene regulation, providing blueprints for the assembly of transcriptional machinery at transcription start sites (TSSs). Empirically, TSSs define the coordinates of core promoters and other regulatory sequences. Thus, experimental TSS identification provides an essential step in the characterization of promoters and their features. Here, we describe the application of CAGE (cap analysis of gene expression) to identify genome-wide TSSs used in root and shoot tissues of two maize (Zea mays) inbred lines (B73 and Mo17). Our studies indicate that most TSS clusters are sharp in maize, similar to mice, but distinct from Arabidopsis thaliana, Drosophila melanogaster, or zebra fish, in which a majority of genes have broad-shaped TSS clusters. We established that ∼38% of maize promoters are characterized by a broader TATA-motif consensus, and this motif is significantly enriched in genes with sharp TSSs. A noteworthy plasticity in TSS usage between tissues and inbreds was uncovered, with ∼1500 genes showing significantly different dominant TSSs, sometimes affecting protein sequence by providing alternate translation initiation codons. We experimentally characterized instances in which this differential TSS utilization results in protein isoforms with additional domains or targeted to distinct subcellular compartments. These results provide important insights into TSS selection and gene expression in an agronomically important crop.

LARGE-SCALE BIOLOGY ARTICLE

INTRODUCTION

Gene transcription is regulated by the concerted actions of chromatin structure and sequence-specific DNA binding proteins, namely, transcription factors that interact with precise cis-regulatory DNA elements in gene control regions. Regulatory information is conveyed, primarily through protein-protein interactions, to the basal transcription machinery consisting of RNA polymerase II (RNP-II) and associated general transcription factors, including the TATA binding protein (TBP) and the TBP-associated factors. The core (or basal) promoter, an ∼100-bp region flanking the transcription start site (TSS), is responsible for the assembly of the preinitiation transcription complex and, therefore, for the accurate initiation of transcription (Smale and Kadonaga, 2003; Sandelin et al., 2007; Juven-Gershon and Kadonaga, 2010). Thus, to determine the location of core promoters and to identify the cis-regulatory elements that contribute to the assembly of the transcription machinery, a first step is to establish the genomic coordinates of TSSs. Genome-wide TSS determination methods such as cap analysis of gene expression (CAGE) (Shiraki et al., 2003), RNA annotation and mapping of promoters for analysis of gene expression (Batut et al., 2013), and paired-end analysis of transcription start sites (Ni et al., 2010) have provided important information regarding TSS selection and core promoter architecture in metazoans (Carninci et al., 2006; Frith et al., 2006, 2008; Sandelin et al., 2007; Hoskins et al., 2011; Lenhard et al., 2012; Nepal et al., 2013; Forrest et al., 2014). In a gene, transcription initiation often occurs at multiple TSSs, constituting a TSS cluster. Each TSS is linked to its own promoter, resulting in what are commonly referred to as promoter clusters. Metazoan promoters can be classified into three main types based on the distribution of TSSs and the presence of particular DNA sequence features. Type I promoters display sharp TSS clusters (also called peaked or focused clusters), are enriched in TATA motifs, and are associated with tissue-specific expression, primarily in adult tissues. Type II promoters display broad TSS clusters (also called weak peaked or dispersed clusters), are enriched in CpG islands, lack TATA motifs, and are ubiquitously expressed. Type III promoters usually also have broad TSS clusters, but CpG islands (absent in plants) extend into the gene body and are characterized by the recruitment of Polycomb and the presence of trimethylated histone 3 Lys 27 (H3K27m3) repressive marks. Type III promoters frequently correspond to developmentally regulated genes (Juven-Gershon and Kadonaga, 2010; Lenhard et al., 2012). The use of alternative TSSs adds another layer of complexity to regulation of gene expression, resulting in transcript isoforms with different 5′-untranslated regions (UTRs), with potential consequences for mRNA stability and translational efficiency. In most extreme cases, the presence of a new AUG codon can result in the biosynthesis of protein isoforms with different N-terminal regions (Ayoubi and Van De Ven, 1996). While most studies have focused on the consequences of alternate promoter usage in particular genes (Payton et al., 2007), in zebra fish, the transition from maternal to zygotic early embryonic development is set apart by two different transcription initiation grammars (Haberle et al., 2014), highlighting the importance of genome-wide core promoter selection during developmental switches.

Knowledge of the position of plant transcription initiation sites and core promoter architecture lags significantly behind that for metazoans, a consequence of just a couple of genome-wide TSS analyses conducted so far, and only in Arabidopsis thaliana (Yamamoto et al., 2009; Morton et al., 2014). When results from these studies are combined with core promoter predictions based on full-length cDNAs, it appears that, while plants and animals share some commonalities that include the occasional presence of a TATA and initiator (Inr) elements, these two kingdoms of life utilize significantly different DNA element configurations proximal to the predicted TSSs (Molina and Grotewold, 2005; Yamamoto et al., 2009; Kumari and Ware, 2013; Morton et al., 2014). It is possible that alleged differences between plant and animal promoters simply reflect the lack of experimental TSS information, except for Arabidopsis. Alternatively, promoter differences could reflect variations in how RNP-II is tethered to the preinitiation complex or how it transcribes protein-coding genes between both kingdoms. In addition to RNP-I, RNP-II, and RNP-III, plants express two other RNA polymerases, RNP-IV and RNP-V (reviewed in Matzke et al., 2015). RNP-IV and RNP-V are primarily associated with silencing pathways involving small interfering RNA, mainly derived from transposable elements (TEs; reviewed in Matzke et al., 2015). TEs have a significant influence on gene regulation in animals (Bourque, 2009) and plants (Bennetzen and Wang, 2014), for example, by providing binding sites for transcription factors (Jordan et al., 2003; Bourque et al., 2008) and by influencing chromatin structure and DNA methylation (Erhard et al., 2013; Gent et al., 2013; Regulski et al., 2013). Similar to humans and other mammals, but different from Arabidopsis and Drosophila melanogaster, a significant portion (∼85%) of the maize (Zea mays) genome is formed by TE-like sequences (Baucom et al., 2009; Schnable et al., 2009), contributing to the polymorphic structure of maize haplotypes. Breeders have aggressively exploited the extensive genetic diversity of maize for yield improvement and enhanced field performance. The maize genome (Schnable and Freeling, 2011) continues to be in a draft stage, with over 25% of all gene models beginning with the ATG translation initiation codon, rather than experimentally determined TSSs (Erhard et al., 2015). Yet, regions immediately upstream of genes are significantly enriched in polymorphisms associated with traits of agronomic importance (Li et al., 2012; Wallace et al., 2014), suggesting that variations in cis-regulatory sequences play a key role in the phenotypic diversity of maize. Thus, establishing maize TSSs genome-wide is essential to understand the influence of genome variation on gene expression and TSS selection.

Using CAGE, we experimentally established genome-wide maize RNP-II transcription initiation profiles. Our results show that the majority of maize promoters are sharp, like those in mice but different from what has been found for those in Drosophila, zebra fish, and Arabidopsis. Yet, similar to proximal regulatory regions in plants and animals, ∼38% of all genes harbor a TATA motif, which is enriched in sharp promoters. To understand how genetic variation influences TSS selection, we compared results obtained from two divergent (Lorenz and Hoegemeyer, 2013) and widely used maize inbred lines, B73 and Mo17. Our results identified hundreds of instances of haplotype-specific TSS occurrences. The comparison between root and shoot tissues in both inbreds indicates the existence of distinct transcription initiation codes, resulting in some cases in different protein isoforms through the use of alternate translation initiation codons. Unexpectedly, in a few instances, these isoforms were experimentally determined to localize to distinct subcellular compartments in root and shoot, uniquely linking initiation of transcription with protein function. The genome-wide identification of TSSs, together with their dependence on genotype and tissue, provides a framework to better understand the maize cis-regulatory landscape, while significantly improving maize genome annotation.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Genome-Wide Maize TSS Identification by CAGE

To determine the maize transcription initiation landscape, we applied CAGE to the divergent yet widely used inbred lines, B73 and Mo17. To establish how TSS usage is influenced by plant tissue, mRNA isolated from roots and shoots of 14-d-old seedlings was used to generate CAGE libraries, which were sequenced by Illumina. We obtained 34,666,735 high-quality 27-bp-long CAGE tags (Supplemental Table 1) that were aligned (∼91% overall alignment rate) to the reference maize genome (Maize B73 RefGen v3). We identified CAGE TSSs (referred to here as CTSSs) using CAGEr (version 1.2.9) (Haberle et al., 2014). Adjacent CTSSs were aggregated into CTSS clusters (and named hereafter TCs), in which we identified the position of the predominant TSS (CTSS dominant or CTSSd; Figure 1A). This analysis resulted in a total of 338,017 high-confidence CTSSs that collapsed to 75,681 TCs, corresponding to 30,622 transcripts and 17,409 genes (Table 1). Thus, the TSSs identified by CAGE increase by 8-fold the number of known maize transcription initiation sites derived from the Arizona Genome Institute or CERES full-length cDNA collections, which together total 43,676 TSSs (Alexandrov et al., 2009; Soderlund et al., 2009).

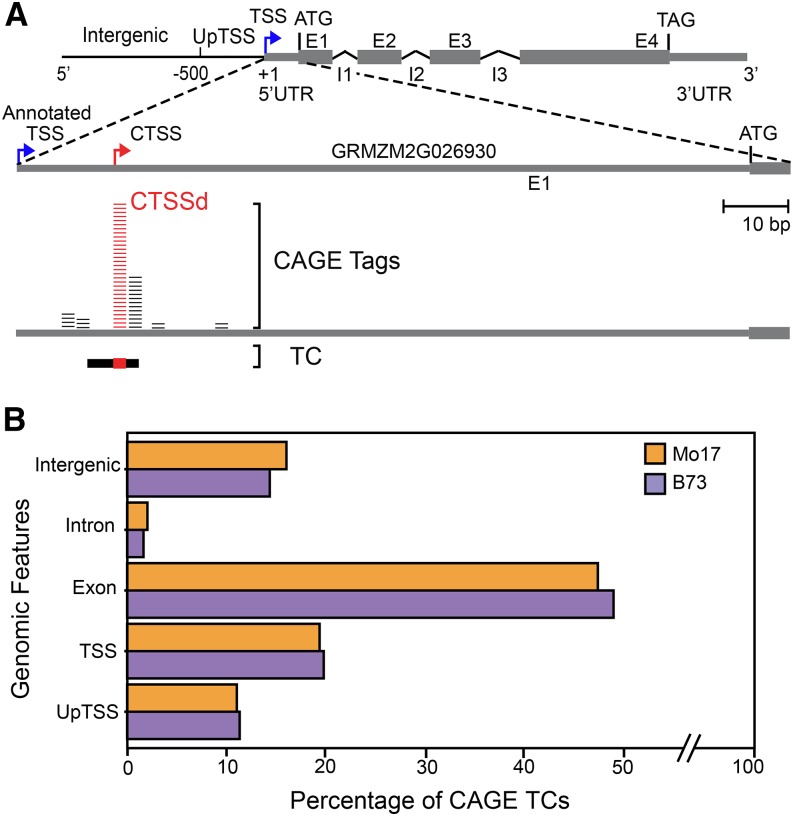

Figure 1.

High-Throughput Mapping of TSSs in Two Maize Lines.

(A) Representation of an extended gene model (top) and CAGE results of B73 shoot tissue for GRMZM2G026930 corresponding to the Anthocyaninless1 (A1) gene (bottom). Exons (E; gray rectangle) are linked by introns (I; black lines) with UTRs (thinner gray rectangles) represented. CTSSs were determined from the CAGE tags (short horizontal lines). CTSSs were grouped into TCs (horizontal black bar, with the dominant CTSS position indicated in red). The position of the dominant CTSS (CTSSd) is indicated with a red arrow and differs from the annotated TSS (blue arrow). The 500-bp region upstream of the CTSSd is designated as UpTSS, with everything outside the extended gene model considered to be intergenic.

(B) Percentage of TCs corresponding to the different genomic segments in Mo17 and B73.

Table 1. Summary of CTSSs and TCs Obtained and Total Genes Assigned in Each Sample.

| Sample | CTSS | TC | Transcript | Nonredundant Transcripts | Genes | Nonredundant Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B73 Shoot | 157,249 | 19,880 | 23,393 | 25,275 | 13,243 | 14,418 |

| B73 Root | 108,919 | 14,568 | 21,178 | 11,955 | ||

| Mo17 Shoot | 188,173 | 22,875 | 25,055 | 26,823 | 14,141 | 15,297 |

| Mo17 Root | 163,969 | 18,358 | 24,232 | 13,747 | ||

| Total | 338,017 | 75,681 | 30,622 | 17,409 |

Total in the CTSS column corresponds to unique stranded genomic coordinates (chromosome, start, end) assigned to TCs and identified across all samples independent of coverage agreement. Total in the TC column corresponds to the sum of the TCs identified in each sample. TCs were assigned to annotated (Maize B73 RefGen v3) transcripts, and genes in each sample and the union of the annotated transcripts assigned to TCs and the annotated genes assigned to TC is reported in the nonredundant transcripts and nonredundant genes columns, respectively.

To compare the full-length cDNA 5′-ends with the obtained CAGE TSSs, we mapped them to the maize genome and plotted the respective distances to the annotated TSSs (Supplemental Figure 1). Two aspects become immediately clear: (1) that in many instances, the full-length cDNA 5′-ends and the CAGE TSSs are in close proximity (represented by the diagonal in Supplemental Figure 1) and (2) that many of the full-length cDNA 5′-ends and the CAGE TSSs are mapping downstream of the annotated TSS (large number of dots in the first quadrant of Supplemental Figure 1). Indeed, a large portion (>80%) of the TSSs identified by CAGE intersect with other features of the annotated gene models, including regions upstream of (annotated) TSSs or UpTSSs, exons, and intergenic regions (Figure 1B; ∼10, ∼50, and ∼15% respectively), irrespective of whether we used B73 or Mo17 (Figure 1B). Based on these results, we determined that 9418 transcripts corresponding to 5552 TCs intersected the annotated TSSs. These findings reveal that ∼70% of the gene models in the most recent release of the maize genome have a misplaced TSS. A case example of misannotation is provided by the classical gene A1, for which the TSS that we defined by CAGE matches the TSS position mapped by S1 nuclease (Schwarz-Sommer et al., 1987), yet the TSS is shifted by ∼15 bp in the current annotation (Figure 1A). Thus, incorporating the newly identified CTSSs will significantly improve maize genome annotation and, therefore, the validity of computational studies aimed at identifying conserved core promoter cis-regulatory motifs.

We compared the positions of the identified CTSSs to available data for maize acetylation and methylation histone marks, which are predictive of active promoters (H3K9ac and H3K4me3) or actively transcribed gene bodies (H3K36me3) (He et al., 2013). For this, we determined the distance from the center of the histone modification enrichment region to the closest CTSSd, with an upper bound of 1 kb (Supplemental Figure 2). In all instances, the histone modification peak increased immediately downstream of the identified CTSSd, with a maximum within the first 500 bp of the transcribed region. No major differences were observed between Mo17 and B73, or root and shoot tissues (Supplemental Figure 2). From these analyses, we conclude that the identified TSSs are imbedded within the chromatin environment normally associated with core promoters (Koch et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2008; Kolasinska-Zwierz et al., 2009).

We used the information obtained from maize CTSSds to determine the length distribution of 5′-UTRs for the ∼28,000 transcripts analyzed (Supplemental Figure 3). We determined that the median 5′-UTR length for maize genes is 154 nucleotides, which is similar to the size computed for human 5′-UTRs (171 nucleotides) and mouse (159 nucleotides), but shorter than Drosophila (191 nucleotides) and larger than Arabidopsis 5′-UTRs (112 nucleotides) (Supplemental Figure 3). These results suggest that, contrary to what was previously proposed (Liu et al., 2012), 5′-UTR length and genome sizes are not obviously positively correlated. Taken together, our results provide a comprehensive view of the organization of TSSs in maize, significantly improving shortcomings in the annotation of the maize genome. Because, with the exception of Arabidopsis, genome-wide TSS information in plants is simply not available, our results are important as a reference for similar future CAGE analyses in other plants.

Maize Displays Predominantly Sharp Transcription Initiation

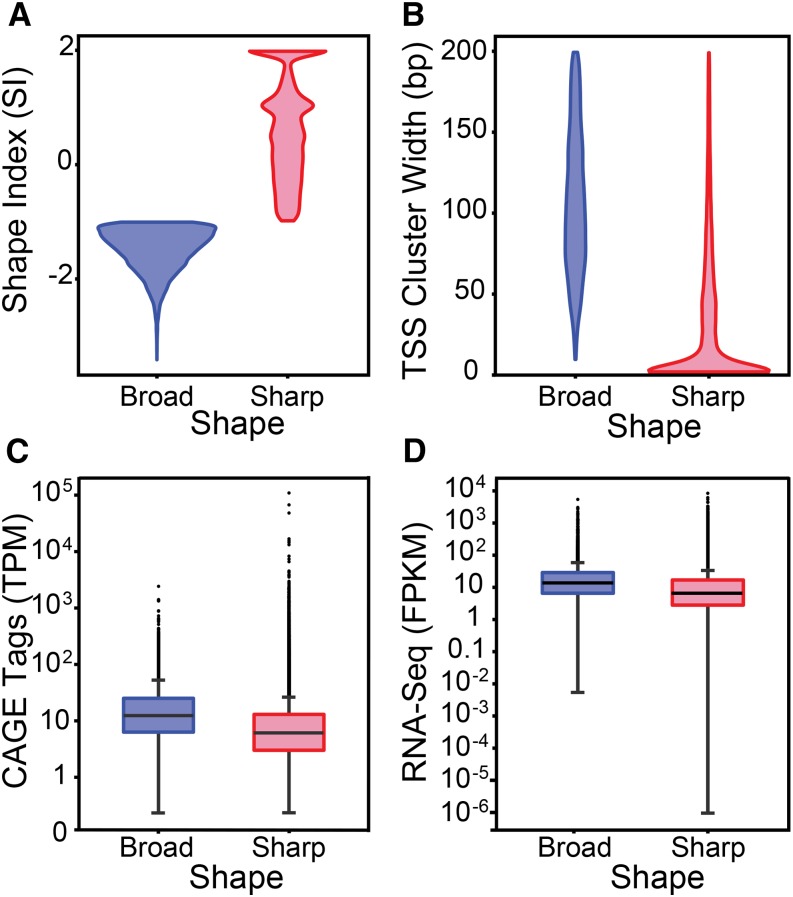

We analyzed the profile of maize transcription initiation sites in each TSS cluster (TC) by calculating a shape index (SI), a metric considered less sensitive to outliers than relying solely on the TC width (Hoskins et al., 2011). The SI index follows a continuum between a TC (and therefore the corresponding promoter) being completely sharp (SI = 2 corresponding to just 1 TSS) to being very broad (SI < −4). Following the criteria used to analyze promoter shape in Drosophila (Hoskins et al., 2011), we divided the 75,681 identified maize TCs into those with a SI > −1, which were considered sharp, and those that had SI of −1 or smaller, which were considered broad (Figure 2A). The width of the broad TCs spanned up to 200 bp, while the majority of the sharp TCs were narrower than 50 bp (Figure 2B). We determined that the vast majority (87%) of the maize TCs have a sharp shape. This contrasts dramatically with what was found in Drosophila, where only 23% of the TCs are sharp (Hoskins et al., 2011).

Figure 2.

Maize Promoter Shape Distribution.

Violin plots displaying differences between sharp and broad TCs. The plots show the kernel density (mirrored curves) of the shape index (A) and TC widths (B). The box plots indicate the distribution of TC expression levels determined by CAGE (measured in TPM) (C) and gene expression levels determined by mRNA-seq (measured in FPKM) (D).

To establish whether the disparity in TSS utilization between maize and Drosophila reflected, for example, differences between the animal and plant kingdom, we investigated promoter shape in other organisms in which genome-wide TSS analyses have been determined. Because the descriptors used for the analysis of core promoter shape varies from one data set to another, in addition to the SI we calculated another metric to compare against zebra fish as a vertebrate data set (see Methods). Our analyses indicate that the proportion of genes displaying sharp promoters in maize (50 to 87%, depending on the method used) is significantly larger than in zebra fish over multiple embryonic developmental stages (28 to 37%) (Nepal et al., 2013). Yet, we found that percentage of sharp promoters in maize was similar to what was found in mouse (66 to 80%) (Kawaji et al., 2006), but significantly larger than in Arabidopsis (36%) (Morton et al., 2014) or Drosophila (23%) (Hoskins et al., 2011). In the context of these other studies, and sensitive to the limitations associated with promoter classification criteria (Frith, 2014), our results suggest a potential link between core promoter shape and genome size that goes across kingdoms. Perhaps large genomes in which RNP-II transcribed genes are interspersed among retrotransposons and other repetitive DNA features, such as present in maize and mouse, require core promoter recognition mechanisms that result in more focused transcription initiation. By contrast, smaller and more compact genomes might be able to afford having a more lax transcription initiation profile. As additional genome-wide TSS mapping results become available for other species, the generality of the correlation between genome size and promoter shape will be verified.

We investigated the correlation between shape and expression levels and found that the median expression of genes with broad TCs is higher than the median expression of genes with sharp TCs, irrespective of whether we evaluated expression by the number of CAGE tags (tags per million [TPM]; Figure 2C) or by RNA-seq (fragments per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads [FPKM]; Figure 2D). However, genes with the highest expression levels corresponded to those with sharp TSSs (Figures 2C and 2D).

In metazoans, genes with sharp promoters often correlate with those displaying tissue- or cell-specific expression, while those with broad promoters often correspond to housekeeping genes. To determine if this is also the case in maize, we investigated how different promoter shapes correlated with tissue-specific expression. For this, we calculated for each gene a tissue-specific score index (TSPS; Ravasi et al., 2010) using maize gene expression data across several developmental times and tissues (Sekhon et al., 2011) (see Methods). Consistent with prior analyses (Sekhon et al., 2011), most maize genes display a rather constitutive expression (TSPS <1), despite the vast majority showing sharp initiation. Nevertheless, there is over 5-fold enrichment of sharp promoters in maize tissue-specific genes (TSPS >1), suggesting a similar trend as found in metazoans. Taken together, our results demonstrate that the large majority of maize core promoters have the distinguishing feature of a sharp transcription initiation profile, which might contribute in a minor way to gene expression patterns.

Different DNA Motifs Characterize Broad and Sharp Promoters

The separation of TCs into broad and sharp classes prompted us to investigate whether any core promoter DNA elements might be associated with specific promoter shapes, given their importance as determinants of TSS location and direction of transcription in many organisms (Colgan and Manley, 1995; Wang et al., 1996; Chen and Manley, 2003; Fukue et al., 2004). Using the maize TSSs identified by CAGE, we analyzed the [−50;+50] segment centered at the dominant CTSSs applying complementary de novo DNA motif discovery algorithms. Both RSAT and MEME (see Methods) identified a set of TA- and GC-rich motifs (Supplemental Figure 4).

The TA-rich motifs showed positional preference for the [−35; −25] region in 38% of the maize CAGE-defined promoters, likely corresponding to the TATA element, based on studies in other organisms (Bucher, 1990; Ohler et al., 2002; Molina and Grotewold, 2005; Shi and Zhou, 2006; Frith et al., 2008). Previous analyses using the annotated maize genome (i.e., not experimentally validated TSSs) and a generic consensus, predicted TATA motifs in only 13% of the maize genes (Kumari and Ware, 2013). When TATA motifs were investigated in the CAGE-defined promoters using the TATA consensus provided by JASPAR (Mathelier et al., 2014), PlantProm db (Shahmuradov et al., 2003), or derived from other studies (Molina and Grotewold, 2005; Yamamoto et al., 2009) (Supplemental Figures 5A and 6A), we confirmed TATA elements in just 14% of the genes. These results are significant as they indicate that maize TATA motifs might be slightly different from those identified in other plants. In addition, our results show that TATA motifs are present in a significantly larger fraction of promoters than previously predicted (Kumari and Ware, 2013).

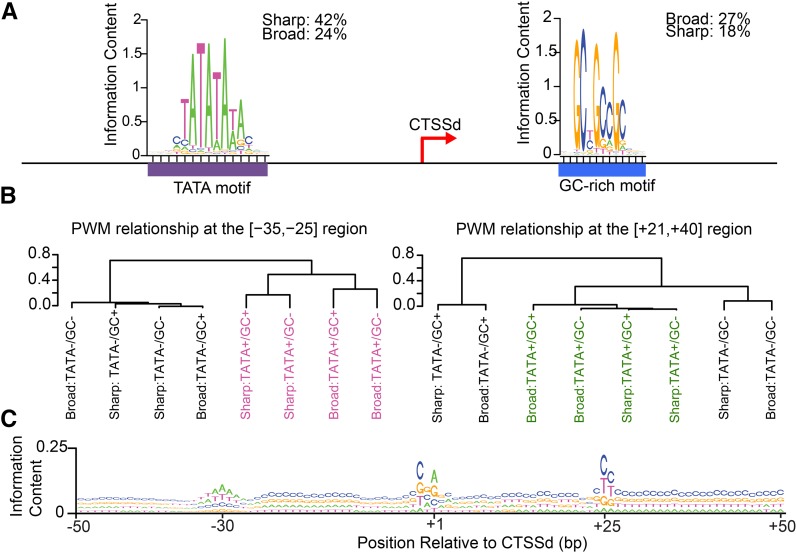

TATA motifs are significantly (P < 0.05, Wilcoxon two-sided nonparametric significance test) enriched in sharp, when compared with broad promoters (Figure 3A). Nevertheless, the presence of a TATA explained transcription initiation in just 42% of all the genes harboring a sharp promoter (Figure 3A), suggesting that other genomic elements are at play in the absence of a TATA. To identify such elements, we searched for other known conserved core promoter motifs (Supplemental Figures 5B and 5C). We confirmed, using the [−50;+50] region, that most conserved cis-elements characteristic of metazoan core promoters that are not typically found in plants (Wang et al., 1996; Molina and Grotewold, 2005; Bernard et al., 2010) are indeed absent in maize (Supplemental Figure 6B). Other described plant-specific motifs (Yamamoto et al., 2007b, 2009; Yamamoto and Obokata, 2008) are often present in maize core regulatory sequences, but their presence is independent of promoter shape (Supplemental Figure 6C).

Figure 3.

Different DNA Motifs Characterize Broad and Sharp Maize Promoters.

(A) Sequence logo representing the consensus of maize TATA+ and GC-rich motifs. TATA and GC-rich motifs positionally restricted to the [−35; −25] and [+21;+40] regions, respectively.

(B) Clustering of maize promoters based on the presence of TATA and/or GC-rich motifs. The dendograms depict complete hierarchical clustering of the 1-spearman correlation (as distance) between the PWMs obtained from the [−35;−25] and [+21;+40] regions derived from the eight possible classes of core promoters.

(C) Sequence logo representing the nucleotide frequency of the [−50;+50] segment of all sharp promoters centered at the CTSSd (+1).

GC-rich motifs showed positional preference for the [+21;+40] region (Supplemental Figures 4C and 4D) and were found in 27% of all genes harboring a broad promoter, in contrast to being present in just 18% of sharp promoters, representing a statistically significant enrichment (Figure 3A). However, since the GC-rich motifs are downstream of the TSS, we cannot formally rule out the possibility that they play roles in some mRNA function (e.g., stability and translation), rather than functioning as transcription regulatory elements.

Based on these results, and to understand which cis-regulatory elements are most important in specifying promoter type, we classified them into eight types depending on shape (sharp or broad) and the presence/absence of TATA and GC-rich motifs (TATA+/GC−, TATA−/GC+, TATA+/GC+, and TATA−/GC−). For this, we derived power weight matrices (PWMs) from the segments in which the respective elements are enriched ([−35;−25] for TATA and [+21;+40] for the GC-like motif, respectively) and pairwise compared the PWMs (see Methods). We found that PWMs derived from the [−35;−25] window present in broad promoters (TATA+/GC− and TATA+/GC+) were different from those derived from the corresponding region in sharp promoters (indicated in magenta in Figure 3B). This means that the TATA motif (plus immediately adjacent base pairs) is different irrespective of the presence/absence of the GC-rich motif, but depending on promoter shape. This finding suggests that varying affinities for TBP, or a diversity in preinitiation complex formation, influence promoter shape. By contrast, PWMs derived from TATA− [−35;−25] regions showed no relationship with promoter shape (Figure 3B).

PWM comparisons also uncovered unexpected patterns in the [+21;+40] region. TATA− promoters cluster in two groups, depending on the presence of GC-rich motifs. However, in TATA+ promoters, the [+21;+40] regions are more similar to each other than to those in TATA− promoters, regardless of promoter shape or whether they are GC+ or GC- (indicated in green in Figure 3B). One interpretation of these results is that the [+21;+40] region harbors an element other than the GC-rich motif that correlates with the presence of TATA.

To determine what additional information might be contained in the [+21;+40] region and how it may relate to other core promoter components, we generated the nucleotide frequency matrix for the [−50;+50] segment for all promoters. One of the features that immediately became evident is the abundance of the CT dinucleotide at position +25 (Figure 3C), in promoters with or without the GC-rich motif (the C in the CT dinucleotide is part of the GC-rich motif, when present) (Supplemental Figure 7). The CT appears to contribute in information content to a larger extent than the Initiator (at position +1) in TATA− promoters (Supplemental Figure 7A) but does not explain the conservation of the [+21;+40] region in TATA+ promoters (Supplemental Figures 7C and 7D). Taken together, our results revealed the existence of additional DNA sequence motifs located downstream of the TSS that function together with, or instead of, TATA in specifying sharp transcription initiation in a subset of genes. Likely, chromatin features other than DNA sequence alone contribute to specify promoter shape and TSS location (Valen and Sandelin, 2011; Lenhard et al., 2012). The large-scale determination of maize TSSs will help elucidate those features.

Promoter Evolution and Developmental Gene Regulation Defined by TSS Selection Differences

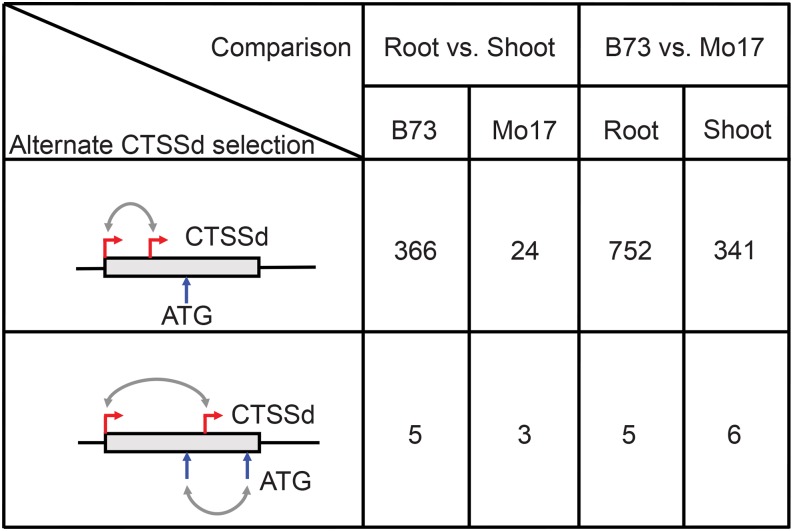

To investigate genotype- and tissue-specific promoter usage, we analyzed TSS selection in root and shoot tissues, in the two inbred lines. The comparison between roots and shoots in B73 showed 371 instances of significant shifts in CTSSd positions and 27 cases in Mo17 (Figure 4, root versus shoot). From these, only three genes were common between both inbred lines. Because the Mo17 genome sequence is not yet available, all of the mapping relies on alignment to the B73 reference genome. Given the highly polymorphic nature of maize noncoding sequences (Wallace et al., 2014), this results in an underestimate of the CTSSd shifts in Mo17. For the 371 instances in which a CTSSd shift was observed between tissues in B73 (Figure 4), we determined that in only 12 genes, the TC overlapped with a repeat. When we compared the genes with a CTSSd shift, we found that in 43% of the cases there was at least one annotated repeat within 1 kb upstream sequence, compared with 31% for all genes. This may indicate that alternative TSS selection is influenced by the presence of repeats upstream of the CTSSd.

Figure 4.

Alternate CTSSd Selection of Maize Genes.

Comparisons of the number of genes that display alternative CTSSd in root versus shoot or B73 versus Mo17. The diagrams illustrate how alternate CTSSd (red arrows) may influence the utilization of different ATG translation start codons (indicated by blue arrows).

When we compared CTSS usage between B73 and Mo17, we found 757 instances of significant shifts in CTSSd positions in root tissues and 347 in shoots. In 114 cases, the same gene showed a shift in both inbred lines. As mentioned for the comparisons between plant organs, a consequence of the unavailability of a Mo17 genome is that we have surely missed a number of CTSSd shifts corresponding to Mo17 CAGE tags that fail to align to the B73 reference genome.

The vast majority (98.8%) of these CTSSd shifts had no consequence for the protein coding potential of the resulting genes (Figure 4). However, in a small fraction of genes (19 total corresponding to 8 for root versus shoot and 11 for B73 versus Mo17), the shift in the CTSSd resulted in a new ATG (Supplemental Figure 8). For the 11 instances in which differences between B73 and Mo17 were observed, we evaluated the potential effects of genomic polymorphisms and repeats upstream of the CTSSd using available genomic resources for Mo17 (HapMapV3 [http://www.panzea.org/#!hapmapv3/c102o]; Mo17 454 reads from Phytozome [http://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html]; Chia et al., 2012; Xin et al., 2013). In 7/11 instances, we identified insertions and deletions between Mo17 and B73, suggesting that indels participate in alternative TSS selection.

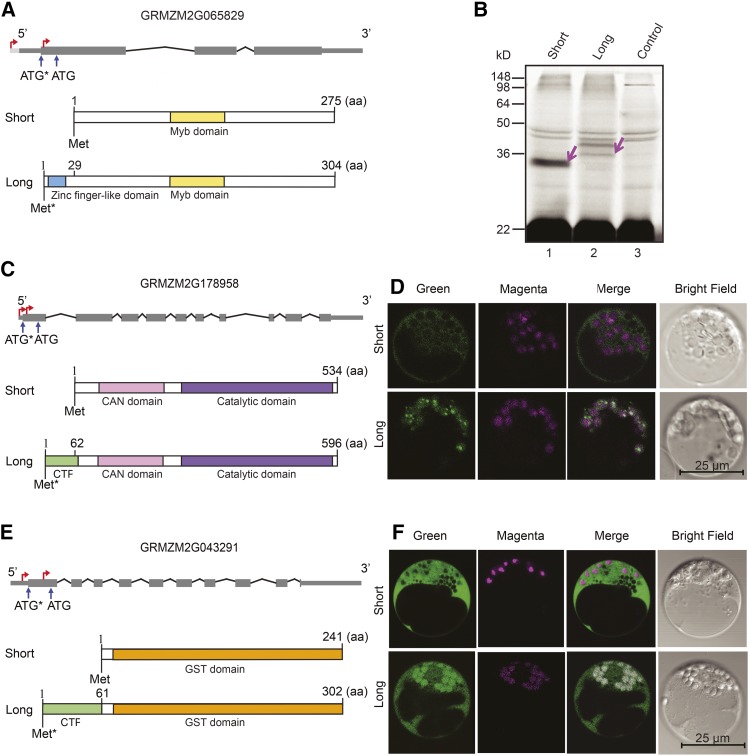

To determine the potential affect that alternate CTSSd selection has on protein sequence and function, we selected a few examples for analysis. GRMZM2G065829 was identified from the shoot-root comparison and encodes MYBR35, a member of the large MYB family of transcription factors (Feller et al., 2011). The distance between the alternatively used CTSSs is 171 bases for both B73 (Figure 5A) and Mo17 (Supplemental Figure 8C). The most upstream CTSS, corresponding to what we refer to here as the long transcript used in roots (Figure 5A) and to the B73 maize genome annotation (RefGen v3), harbors two ATGs: one upstream present in the long transcript (Figure 5A, ATG*) and an additional ATG located 87 nucleotides downstream and present in both transcripts. To determine whether both ATGs could be used for protein synthesis initiation, we cloned and in vitro transcribed the long and short B73 mybr35 transcripts and subjected them to in vitro translation in wheat germ extracts using the FluoroTect GreenLys labeling system. The short transcript (lane 1, Figure 5B) resulted in a 34-kD protein, in agreement with the 275 amino acids encoded in the open reading frame (ORF), plus 24 GreenLys (additional 5.5 kD). The long transcript (lane 2, Figure 5B) resulted in the accumulation of two proteins: one of an ∼38-kD protein, which might be a doublet with the lower band also present in the control lane, and a more prominent band of ∼43 kD, which is completely absent from the control line. While the ∼38-kD band is more in agreement with the 29 additional amino acids encoded in the longer ORF, we cannot rule out that the 43-kD protein corresponds to the ORF present in the long transcript. The absence of the 34-kD band in lane 2 provides strong evidence that translation is preferred from the upstream ATG, when present. An analysis of the 29 amino acids that distinguish the long and the short proteins using SUPERFAMILY (Wilson et al., 2009) revealed the presence of a zinc-finger domain in this region, which is likely to provide a specific function to this MYB transcription factor in the root that is absent in shoots.

Figure 5.

Protein Diversity Generated by Alternate CTSSd Usage.

(A) Gene and protein models of GRMZM2G065829 indicating the position of the alternatively used CTSSd (red arrows) and the respective ATG translation start codons. The upstream ATG (ATG*) results in a (long) protein harboring a MYB domain (yellow box) and a zinc finger-like domain (blue box), absent in the other (short) protein.

(B) SDS-PAGE separation of the in vitro transcription/translation products using FluoroTect GreenLys of the short (lane 1) and long (lane 2) mRNAs depicted in (A). New proteins, absent in the no DNA control (lane 3), are indicated by the purple arrows.

(C) Gene and protein models of GRMZM2G178958. The predicted proteins harbor an aminopeptidase N-terminal (CAN) domain (pink box) and a catalytic domain (purple box), while the protein translated from the upstream ATG (long) additionally has a predicted chloroplast transit peptide (CTP; green box).

(D) Confocal microscopy images of maize protoplasts expressing the two GRMZM2G178958 protein isoforms (short and long depicted in [C]) fused to GFP (green). The magenta signal derives from the autofluorescence of chlorophyll corresponding to chloroplasts, and the merged indicates the level of colocalization of the green and magenta fluorescent signals.

(E) Gene and protein models of GRMZM2G043291. Both (short and long) proteins encode for GST proteins (orange box), and the protein derived from the upstream ATG (long) has an additional chloroplast transit peptide (CTP; green box).

(F) Subcellular localization for the two GRMZM2G043291 protein isoforms fused to GFP, as described for (D).

GRMZM2G178958 and GRMZM2G043291 provide two other interesting examples of how differential CTSS selection between root and shoot influences protein function. For GRMZM2G178958, the distances between the CTSSd used in root and shoot are 59 bases in Mo17 and 53 bases in B73 (Figure 5C). For GRMZM2G043291, the distances are 137 bases in B73 and 176 bases in Mo17 (Figure 5E). In both instances, the reference genome annotates as the TSS only the most upstream CTSS, corresponding to the transcript present in shoots for both genes (designated herein as long transcripts; Figures 5C and 5E). In both cases, using the ChloroP resource (Emanuelsson et al., 1999), we determined that the products from the long, but not from the short, transcripts harbor predicted N-terminal chloroplast target peptides. To establish whether the long and short transcripts are directed to distinct subcellular locations, we cloned regions downstream of the first ATG from the long and short transcripts from B73 downstream of the constitutive CaMV 35S promoter as C-terminal fusions to GFP. The resulting plasmids were transformed into maize protoplasts, and green fluorescence was evaluated to determine the localization of the respective proteins (Figures 5D and 5F) and compared with free GFP (Supplemental Figure 9). For both genes, our results show that the long proteins accumulate in the chloroplasts (identified by the red autofluorescence provided by chlorophyll), while the proteins derived from the short transcripts localize to the cytoplasm (Figures 5D and 5F). GRMZM2G178958 encodes a putative neutral leucine aminopeptidase (N-LAP), and the closest homolog of this gene in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) localizes to the chloroplast, yet harbors a downstream ATG with the potential to generate a protein lacking the N-terminal plastid transit peptide (Tu et al., 2003), suggesting the possibility of a conserved mechanism for protein multiplicity in both plants. Maize GRMZM2G043291 encodes a putative glutathione S-transferase (GST). Arabidopsis GSTF8, encoding a GST distantly related from a sequence perspective to GRMZM2G043291 (Chi et al., 2011), uses at least two distinct TSSs, resulting in transcripts producing a long protein targeted to the plastid and a short one that is cytoplasmic (Thatcher et al., 2007). Furthermore, maize Bronze2 encodes a maize GST that participates in anthocyanin pigment formation and employs an alternative TSS 220 bp upstream of the one used under normal conditions, when induced by cadmium stress (Marrs and Walbot, 1997). Whether the long and short BZ2 proteins localize to different subcellular compartments is not known. Taken together, our findings demonstrate that the use of alternate TSSs provides a previously underrated mechanism to generate maize protein isoform diversity. The comparison of two plant parts (roots and shoots) between two widely studied inbred lines (B73 and Mo17) furnishes insights into the plasticity of TSS selection driven by tissue or genotype, providing a first step to investigate what aspects of the gene regulatory machinery are responsible for TSS multiplicity and the subsequent effect on protein function.

METHODS

Maize (Zea mays) Material and RNA Preparation

B73 and Mo17 maize lines were grown under controlled environmental conditions (16 h light/27°C, 8 h dark/21°C.) At 14 d after germination, shoots and roots from two separate sets of five seedlings each (biological replicates) were collected, pooled, ground in liquid nitrogen, and used to isolate RNA by the Direct-zol RNA MiniPrep Kit following the manufacturers’ recommendations (Zymo Research).

CAGE

CAGE was conducted from B73 and Mo17 shoots and roots RNA using two independent biological replicates, as previously described (Takahashi et al., 2012) with few modifications. Five micrograms of total RNA was reverse transcribed using 462 pmol of a random primer that includes the EcoP15I sequence (Takahashi et al., 2012). RNA-cDNA hybrids were 5′ biotinylated using biotin hydrazide (Vector Lab), followed by a treatment with 50 units of RNase I (Promega) at 37°C for 30 min and incubation with 100 μL streptavidin magnetic beads (PureBiotech) at room temperature for 30 min. After release from the beads, the single-stranded cDNAs were ligated to different 5′ bar-coded linkers (Supplemental Table 2) using the DNA ligation Mighty Mix (Clontech Laboratories). Second-strand cDNAs were synthesized and digested with EcoP15I (NEB), resulting in 27-bp cDNA fragments. Then, 3′ linkers were added to the cleaved double-stranded cDNAs by T4 DNA ligase (NEB). After removing excess 3′ linkers by incubation with 10 μL streptavidin magnetic beads at room temperature for 60 min, cDNAs were amplified for 12, 14, 16, and 18 cycles (98°C for 10 s, 60°C for 10 s) to determine the optimized cycle number for each sample. Concentration and size distribution of PCR products were evaluated by a DNA Bioanalyzer (Agilent). The cDNAs of B73 roots were PCR amplified for 16 cycles and cDNAs of B73 shoots, Mo17 roots, and shoots for 14 cycles to reach in the DNA Bioanalyzer the desired fluorescence units (5 to 10, corresponding to a molarity of ∼10 nM) for fragments ∼100 bp long. After bulk PCR amplification, PCR products were treated with 20 units of Exonuclease I (NEB) at 37°C for 1 h and purified with the MinElute PCR purification kit (Qiagen). DNA concentration and size distribution were evaluated again by the Bioanalyzer. Equal DNA amounts from each replicate were pooled to a 5 pM final concentration and sequenced using the Illumina HiSequation 2000 sequencer. A total of 108,537,619 raw reads were obtained. For sequencing analyses, adapters were removed with Bash scripts using regular expressions to search for each of the CAGE adapters (Supplemental Table 2), and TagDust (Lassmann et al., 2009) was used to identify chimeric sequences arising by mistaken combination of adapter sequences. Only sequences 25 to 30 bp long were kept for further analyses. The most recent maize B73 genome assembly (Maize B73 RefGen v3) was used as reference and downloaded from GRAMENE (Liang et al., 2008). All 34,666,735 trimmed 27-bp CAGE tags were mapped using BOWTIE2 version 2.0.4 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012), allowing unique mapping and a maximum of two mismatches. The alignment files were further used as input in the bioconductor package CAGEr version 1.2.9 for the following tasks: (1) to correct for G-addition when a mismatching G was encountered at the first position; (2) to estimate CAGE transcription start sites; (3) to cluster CAGE TSSs in nonoverlapping TSS clusters (Balwierz et al., 2009) and TCs in nonoverlapping regions; (4) to calculate expression values for dominant CTSSs (CTSS with the highest expression value in a given TC) and TCs in TPM after a power law-based normalization (Frith et al., 2006); (5) to calculate the interquantile width, defined as the absolute distance in base pairs between positions of 10th and 90th percentile of the cumulative sum of CAGE tags for each TC; and (6) to determine differential usage of TSSs between tissues and between inbred lines (Haberle et al., 2014). To account for rRNA contamination, TC sequences were compared against the MIPS database (Mewes et al., 2002) of repetitive elements using BLAST (Spannagl et al., 2007; Camacho et al., 2009). Hits reaching the established threshold (E < 10−15, 98% coverage and 98% similarity) were removed from further analyses. Non-rRNA TCs were further clustered between the compared samples (i.e., root versus shoot and B73 versus Mo17), the cumulative distribution of CAGE normalized signals was calculated across those clustered regions, and the difference between the cumulative distribution was statistically evaluated using a Kolmogorov Smirnov test and further corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini and Hochberg method (false discovery rate threshold = 0.05) (Haberle et al., 2014). CAGE libraries were sequenced using Illumina HiSequation 2000. For sequence analysis, adapters were removed and tags trimmed to the expected length (∼27 bp). Tags were mapped against the maize reference genome using BOWTIE2 (version 2.0.4) (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012). Alignment files were further used in CAGEr (version 1.2.9) to determine CTSSs, TCs (Balwierz et al., 2009), TC expression, CTSSd for each TC, TC interquantile width, and to compare samples to define cases of alternate TSS selection (Haberle et al., 2014).

Definition of TSSs from Full-Length cDNA Collections

As a control group for TSS definition from the CAGE data, we used the 5′ end sequence of full-length cDNAs from the Arizona and CERES collections derived from different tissues. Positions of the full-length cDNA 5′ ends were determined by aligning the first 100 nucleotides to the maize reference genome, as explained for CAGE tags. Identical TSS positions were collapsed to generate the full-length cDNA TSS set.

Identification of Motifs Enriched in Core Promoter Sequences

To identify core promoter elements, we used the [−50;+50] genomic region, extracted from the genome assembly (B73 RefGen v3) using bedtools (Quinlan, 2014) (getfasta, -s option to force strandedness, v2.17.0), and those containing Ns were discarded from further analyses to avoid including sequences representing assembly errors. Motif overrepresentation was evaluated de novo and by comparison against core promoter motifs identified in other organisms.

RNA-Seq Library Preparation and Analysis

Quantification of gene expression was obtained from mRNA-seq data of B73 14-d-old roots and shoots from published data sets (SRX012380-81 and SRX212597-600) (Wang et al., 2009; He et al., 2013) and from mRNA-Seq data of Mo17 14-d-old roots and shoots generated in this work. Mo17 mRNA-seq libraries corresponding to two biological replicates for each tissue were prepared using purified poly(A) mRNA obtained from 200 ng total RNA as previously described (Morohashi et al., 2012). Poly(A) mRNA was heated at 94°C for 10 min in fragmentation buffer, and mRNA-seq libraries were prepared following the manufacturer’s specifications (RS-100-0801; Illumina) using 15 cycles of amplification. PCR products were purified using the Agencourt AMPure (Beckman Coulter) and the MinElute PCR purification kit (Qiagen). Concentration and size distribution were determined by the high-sensitivity DNA Bioanalyzer (Agilent) prior to sequencing. Reads obtained were aligned against the maize reference genome using TopHat 2.0.9 (Trapnell et al., 2009) and gene expression measured in FPKM using Cufflinks version 2.1.1 (Trapnell et al., 2013).

Determination of Tissue Specificity Scores (TSPSs)

The tissue specificity of maize genes was calculated based on their expression patterns in different tissues and developmental time from published microarray data (Sekhon et al., 2011). From the expression data, we calculated a TSPS to quantify the degree of tissue specific expression which is defined as TSPS = SUM [fi * log2 * (fi/pi)].

The value fi corresponds to the fractional gene expression level in tissue i, calculated as the proportion of the gene expression level in tissue i to its total expression level across all samples (SUM), and pi is the fractional expression of the same gene assuming uniform expression across all tissues (null model). A TSPS value of zero would be reported for uniform gene expression across all samples and larger TSPSs would be reported for more specific expression of a gene in few, or a single, sample(s). The threshold used here to classify a gene as tissue specific (TSPS ≥ 1) has been used previously for similar categorizations (Ravasi et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2014).

Histone Modification Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing Analyses

Histone H3K36me3, H3K4me3, and H3K9ac chromatin marks (SRX012382-83, SRX0123825, SRX212613-16, SRX212621-24, and SRX212629-32) were obtained from B73 and Mo17 14-d-old shoot and root tissues from public chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing data (Wang et al., 2009; He et al., 2013). Sequences were aligned as described for CAGE files and subsequently used as input for MACS2 (broad peak option) to evaluate the significance of enriched chromatin immunoprecipitation regions (https://github.com/taoliu/MACS).

Maize TC Shape and Comparison with Other Organisms

To determine TCs generated from focused and dispersed transcription and for comparative CAGE analyses of maize with other organisms, maize TC shape was classified using two metrics: the interquartile width (iq) and SI. An iq ≤ 10 bp defined peaked TCs, whereas iq > 10 bp corresponded to broad TCs (Nepal et al., 2013). SI was defined as  , where L corresponds to the collection of TSSs observed in a given TC, and P is the probability of finding a TSS at the i-th position within a given TC; Pi values were derived from the observed frequency as previously described (Hoskins et al., 2011). SI > −1 corresponded to peaked TCs and SI ≤ −1 to broad TCs. The iq width was used for comparison with zebra fish data sets (Nepal et al., 2013), whereas SI was used for comparisons with Drosophila melanogaster (Hoskins et al., 2011).

, where L corresponds to the collection of TSSs observed in a given TC, and P is the probability of finding a TSS at the i-th position within a given TC; Pi values were derived from the observed frequency as previously described (Hoskins et al., 2011). SI > −1 corresponded to peaked TCs and SI ≤ −1 to broad TCs. The iq width was used for comparison with zebra fish data sets (Nepal et al., 2013), whereas SI was used for comparisons with Drosophila melanogaster (Hoskins et al., 2011).

Identification of Motifs Enriched in Core Promoter Sequences

To determine de novo overrepresented motifs in the core promoters and positional enrichment relative to the dominant CTSS, sequences were scanned using the RSAT peak motif pipeline (Thomas-Chollier et al., 2012) and further with the MEME-ChIP (v4.9.1) (Ma et al., 2014). The set of TA- and GC-rich promoters was obtained from the combined results obtained from MEME and RSAT. Based on the abundance of sharp and broad promoters associated to TA- and GC-rich motifs in each sample, the nonparametric Wilcoxon test was run to determine if differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

The DNA sequences of region [−35;−25] and [+21;+40] were obtained from TATA+/ GC+, TATA+/GC−, TATA−/GC+, and TATA−/GC− in both sharp and broad promoters and used to build PWMs. Next, PWMs were pairwise compared using the Spearman correlation, and statistical significance of the correlation was evaluated using the mycor function from R package mycor (v0.1). The 1-spearman correlation values were used as the distance input of the hclust (method= “complete”) function from R package stats (v3.1.2) to plot similarity dendograms. Sequence LOGOs were drawn using the seqLOGO function from the R package seqLOGO (v1.32.1).

To evaluate if core promoter elements previously described in other organisms were present in maize, PWMs derived from PlantPromDB (Shahmuradov et al., 2003), from JASPAR POLII databases (Mathelier et al., 2014), and from the literature (Molina and Grotewold, 2005; Yamamoto et al., 2007a) were used in combination with FIMO (v4.9.0) from the MEME suite (default P < 0.0001) to scan the same region used for de novo motif discovery. The FIMO output was used to draw density plots (R package ggplot2 v1.0.0) for each of the PWMs scanned, contrasting broad and sharp promoters (Supplemental Figure 6).

Plasmid Construction

cDNAs were obtained from total RNA of B73 shoots and roots used for CAGE by reverse transcription using oligo(dT) primers and the ThermoScript RT-PCR system kit (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. GRMZM2G065829 (mybr35) long and short putative transcripts identified by CAGE were cloned from B73 14-d-old shoots and roots cDNAs into pcDNA3 vector containing the bacteriophage SP6 promoter using ApaI and HindIII sites (Supplemental Table 2). GRMZM2G178958 and GRMZM2G043291 coding sequences were amplified from the first ATG adjacent to the different dominant TSS identified by CAGE in shoots and roots, respectively, and subsequently cloned into a destination vector containing the 35S promoter (p35S) and 3′ GFP using LR Clonase (Life Technologies) (Supplemental Table 2) (Pomeranz et al., 2010).

In Vitro Transcription/Translation

One microgram of plasmid DNA was transcribed in 10 μL TNT SP6 High-Yield Wheat Germ Protein Expression System (Promega) containing 0.8 μL FluoroTect GreenLys tRNA (Promega). Luciferase SP6 DNA (Promega) was used as control. After 2 h incubation at 25°C, reactions were separated by SDS-PAGE. Images were scanned by Typhoon 9410 Variable Mode Imager (GE Healthcare; excitation at 532 nm).

Maize Protoplast Transformation

Plasmids (15 μg) were transformed into protoplasts isolated from F1 seedlings of B73xMo17, as described (Burdo et al., 2014). Protoplasts were incubated for 18 to 22 h in the dark at 25°C prior to monitoring GFP expression using confocal microscopy (Leica DMIRE2; excitation, 488 nm; emission 500 to 530 nm) and chlorophyll autofluorescence (excitation, 543 nm; emission 580 to 650 nm).

Accession Numbers

The CAGE and RNA-seq raw and processed data described in this article have been deposited into the Gene Expression Omnibus repository under accession numbers GSE70251 and GSE70192, respectively.

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Figure 1. Comparison of CTSS and full-length cDNAs relative to annotated TSSs.

Supplemental Figure 2. CTSS context with respect to histone marks.

Supplemental Figure 3. Comparison of 5′-UTR length distribution across species.

Supplemental Figure 4. TA- and GC-rich motifs identified in maize core promoters.

Supplemental Figure 5. Previously described motifs used in promoter analyses.

Supplemental Figure 6. Positional analysis of several core promoter DNA-sequence motifs in broad and sharp [−50;+50] regions.

Supplemental Figure 7. Sequence logo representation for eight classes of maize promoters.

Supplemental Figure 8. Schematic representation of alternative TSSs for nineteen genes resulting in potential different translation start codons.

Supplemental Figure 9. Subcellular localization of the p35S:GFP control.

Supplemental Table 1. Categorization of CAGE reads.

Supplemental Table 2. List of constructs and primers used in this study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Hazuki Takahashi for advice on CAGE, Jay Hollick for comments on the manuscript, Kengo Morohashi for assistance with CAGE library preparation, Pearlly Yan and the Nucleic Acid Shared Resource (The Ohio State University) for DNA sequencing, and the Center for Applied Plant Sciences Computational Biology Laboratory for support and discussions. This research was funded by grants from the National Science Foundation (IOS-1125620) and the Ohio Plant Biotechnology Consortium (OPBC2014-009) through the Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center to E.G., J.G., and A.I.D.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.K.M.-G. and W.L. contributed equally to this work. J.G., E.G., and A.I.D. designed research. W.L., M.V., N.F.G., and M.K.M.-G performed research. M.K.M.-G., W.L., E.G., and A.I.D. analyzed data. E.G. and A.I.D. wrote the artiucle. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Glossary

- TSS

transcription start site

- CAGE

cap analysis of gene expression

- UTR

untranslated region

- TE

transposable element

- CTSS

CAGE TSS

- TC

TSS cluster

- SI

shape index

- TPM

tags per million

- FPKM

fragments per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads

- TSPS

tissue-specific score index

- PWM

power weight matrices

- ORF

open reading frame

Footnotes

Articles can be viewed online without a subscription.

References

- Alexandrov N.N., Brover V.V., Freidin S., Troukhan M.E., Tatarinova T.V., Zhang H., Swaller T.J., Lu Y.P., Bouck J., Flavell R.B., Feldmann K.A. (2009). Insights into corn genes derived from large-scale cDNA sequencing. Plant Mol. Biol. 69: 179–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoubi T.A., Van De Ven W.J. (1996). Regulation of gene expression by alternative promoters. FASEB J. 10: 453–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balwierz P.J., Carninci P., Daub C.O., Kawai J., Hayashizaki Y., Van Belle W., Beisel C., van Nimwegen E. (2009). Methods for analyzing deep sequencing expression data: constructing the human and mouse promoterome with deepCAGE data. Genome Biol. 10: R79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batut P., Dobin A., Plessy C., Carninci P., Gingeras T.R. (2013). High-fidelity promoter profiling reveals widespread alternative promoter usage and transposon-driven developmental gene expression. Genome Res. 23: 169–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baucom R.S., Estill J.C., Chaparro C., Upshaw N., Jogi A., Deragon J.M., Westerman R.P., Sanmiguel P.J., Bennetzen J.L. (2009). Exceptional diversity, non-random distribution, and rapid evolution of retroelements in the B73 maize genome. PLoS Genet. 5: e1000732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennetzen J.L., Wang H. (2014). The contributions of transposable elements to the structure, function, and evolution of plant genomes. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 65: 505–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard V., Brunaud V., Lecharny A. (2010). TC-motifs at the TATA-box expected position in plant genes: a novel class of motifs involved in the transcription regulation. BMC Genomics 11: 166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourque G. (2009). Transposable elements in gene regulation and in the evolution of vertebrate genomes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 19: 607–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourque G., Leong B., Vega V.B., Chen X., Lee Y.L., Srinivasan K.G., Chew J.L., Ruan Y., Wei C.L., Ng H.H., Liu E.T. (2008). Evolution of the mammalian transcription factor binding repertoire via transposable elements. Genome Res. 18: 1752–1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucher P. (1990). Weight matrix descriptions of four eukaryotic RNA polymerase II promoter elements derived from 502 unrelated promoter sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 212: 563–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdo B., et al. (2014). The Maize TFome--development of a transcription factor open reading frame collection for functional genomics. Plant J. 80: 356–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho C., Coulouris G., Avagyan V., Ma N., Papadopoulos J., Bealer K., Madden T.L. (2009). BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10: 421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carninci P., et al. (2006). Genome-wide analysis of mammalian promoter architecture and evolution. Nat. Genet. 38: 626–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Manley J.L. (2003). Core promoter elements and TAFs contribute to the diversity of transcriptional activation in vertebrates. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 7350–7362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi Y., Cheng Y., Vanitha J., Kumar N., Ramamoorthy R., Ramachandran S., Jiang S.Y. (2011). Expansion mechanisms and functional divergence of the glutathione s-transferase family in sorghum and other higher plants. DNA Res. 18: 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia J.M., et al. (2012). Maize HapMap2 identifies extant variation from a genome in flux. Nat. Genet. 44: 803–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colgan J., Manley J.L. (1995). Cooperation between core promoter elements influences transcriptional activity in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92: 1955–1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuelsson O., Nielsen H., von Heijne G. (1999). ChloroP, a neural network-based method for predicting chloroplast transit peptides and their cleavage sites. Protein Sci. 8: 978–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erhard K.F. Jr., Talbot J.E., Deans N.C., McClish A.E., Hollick J.B. (2015). Nascent transcription affected by RNA polymerase IV in Zea mays. Genetics 199: 1107–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erhard K.F. Jr., Parkinson S.E., Gross S.M., Barbour J.E., Lim J.P., Hollick J.B. (2013). Maize RNA polymerase IV defines trans-generational epigenetic variation. Plant Cell 25: 808–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller A., Machemer K., Braun E.L., Grotewold E. (2011). Evolutionary and comparative analysis of MYB and bHLH plant transcription factors. Plant J. 66: 94–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest A.R., et al. ; FANTOM Consortium and the RIKEN PMI and CLST (DGT) (2014). A promoter-level mammalian expression atlas. Nature 507: 462–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith M.C.; FANTOM Consortium (2014). Explaining the correlations among properties of mammalian promoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 42: 4823–4832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith M.C., Valen E., Krogh A., Hayashizaki Y., Carninci P., Sandelin A. (2008). A code for transcription initiation in mammalian genomes. Genome Res. 18: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith M.C., Ponjavic J., Fredman D., Kai C., Kawai J., Carninci P., Hayashizaki Y., Sandelin A. (2006). Evolutionary turnover of mammalian transcription start sites. Genome Res. 16: 713–722. Erratum. Genome Res. 16: 947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukue Y., Sumida N., Nishikawa J., Ohyama T. (2004). Core promoter elements of eukaryotic genes have a highly distinctive mechanical property. Nucleic Acids Res. 32: 5834–5840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gent J.I., Ellis N.A., Guo L., Harkess A.E., Yao Y., Zhang X., Dawe R.K. (2013). CHH islands: de novo DNA methylation in near-gene chromatin regulation in maize. Genome Res. 23: 628–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberle V., et al. (2014). Two independent transcription initiation codes overlap on vertebrate core promoters. Nature 507: 381–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He G., Chen B., Wang X., Li X., Li J., He H., Yang M., Lu L., Qi Y., Wang X., Deng X.W. (2013). Conservation and divergence of transcriptomic and epigenomic variation in maize hybrids. Genome Biol. 14: R57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins R.A., et al. (2011). Genome-wide analysis of promoter architecture in Drosophila melanogaster. Genome Res. 21: 182–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan I.K., Rogozin I.B., Glazko G.V., Koonin E.V. (2003). Origin of a substantial fraction of human regulatory sequences from transposable elements. Trends Genet. 19: 68–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juven-Gershon T., Kadonaga J.T. (2010). Regulation of gene expression via the core promoter and the basal transcriptional machinery. Dev. Biol. 339: 225–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaji H., Frith M.C., Katayama S., Sandelin A., Kai C., Kawai J., Carninci P., Hayashizaki Y. (2006). Dynamic usage of transcription start sites within core promoters. Genome Biol. 7: R118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch C.M., et al. (2007). The landscape of histone modifications across 1% of the human genome in five human cell lines. Genome Res. 17: 691–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolasinska-Zwierz P., Down T., Latorre I., Liu T., Liu X.S., Ahringer J. (2009). Differential chromatin marking of introns and expressed exons by H3K36me3. Nat. Genet. 41: 376–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari S., Ware D. (2013). Genome-wide computational prediction and analysis of core promoter elements across plant monocots and dicots. PLoS One 8: e79011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Salzberg S.L. (2012). Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9: 357–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassmann T., Hayashizaki Y., Daub C.O. (2009). TagDust--a program to eliminate artifacts from next generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 25: 2839–2840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhard B., Sandelin A., Carninci P. (2012). Metazoan promoters: emerging characteristics and insights into transcriptional regulation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13: 233–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., et al. (2012). Genic and nongenic contributions to natural variation of quantitative traits in maize. Genome Res. 22: 2436–2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C., et al. (2008). Gramene: a growing plant comparative genomics resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 36: D947–D953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Yin J., Xiao M., Gao C., Mason A.S., Zhao Z., Liu Y., Li J., Fu D. (2012). Characterization and evolution of 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions in eukaryotes. Gene 507: 106–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz A., Hoegemeyer T. (2013). The phylogenetic relationships of US maize germplasm. Nat. Genet. 45: 844–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W., Noble W.S., Bailey T.L. (2014). Motif-based analysis of large nucleotide data sets using MEME-ChIP. Nat. Protoc. 9: 1428–1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrs K.A., Walbot V. (1997). Expression and RNA splicing of the maize glutathione S-transferase Bronze2 gene is regulated by cadmium and other stresses. Plant Physiol. 113: 93–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathelier A., et al. (2014). JASPAR 2014: an extensively expanded and updated open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 42: D142–D147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzke M.A., Kanno T., Matzke A.J. (2015). RNA-directed DNA methylation: The evolution of a complex epigenetic pathway in flowering plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 66: 243–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mewes H.W., Frishman D., Güldener U., Mannhaupt G., Mayer K., Mokrejs M., Morgenstern B., Münsterkötter M., Rudd S., Weil B. (2002). MIPS: a database for genomes and protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 30: 31–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina C., Grotewold E. (2005). Genome wide analysis of Arabidopsis core promoters. BMC Genomics 6: 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morohashi K., et al. (2012). A genome-wide regulatory framework identifies maize pericarp color1 controlled genes. Plant Cell 24: 2745–2764. Erratum. Plant Cell 24: 3853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton T., Petricka J., Corcoran D.L., Li S., Winter C.M., Carda A., Benfey P.N., Ohler U., Megraw M. (2014). Paired-end analysis of transcription start sites in Arabidopsis reveals plant-specific promoter signatures. Plant Cell 26: 2746–2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nepal C., et al. (2013). Dynamic regulation of the transcription initiation landscape at single nucleotide resolution during vertebrate embryogenesis. Genome Res. 23: 1938–1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni T., Corcoran D.L., Rach E.A., Song S., Spana E.P., Gao Y., Ohler U., Zhu J. (2010). A paired-end sequencing strategy to map the complex landscape of transcription initiation. Nat. Methods 7: 521–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohler U., Liao G., Niemann H., Rubin G.M. (2002). Computational analysis of core promoters in the Drosophila genome. Genome Biol. 3: 0087.0081–0087.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payton S.G., Haska C.L., Flatley R.M., Ge Y., Matherly L.H. (2007). Effects of 5′ untranslated region diversity on the posttranscriptional regulation of the human reduced folate carrier. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1769: 131–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomeranz M.C., Hah C., Lin P.C., Kang S.G., Finer J.J., Blackshear P.J., Jang J.C. (2010). The Arabidopsis tandem zinc finger protein AtTZF1 traffics between the nucleus and cytoplasmic foci and binds both DNA and RNA. Plant Physiol. 152: 151–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan A.R. (2014). BEDTools: The Swiss-Army Tool for Genome Feature Analysis. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics 47: 11.12.11–11.12.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravasi T., et al. (2010). An atlas of combinatorial transcriptional regulation in mouse and man. Cell 140: 744–752. Erratum. Cell 141: 369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regulski M., et al. (2013). The maize methylome influences mRNA splice sites and reveals widespread paramutation-like switches guided by small RNA. Genome Res. 23: 1651–1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelin A., Carninci P., Lenhard B., Ponjavic J., Hayashizaki Y., Hume D.A. (2007). Mammalian RNA polymerase II core promoters: insights from genome-wide studies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8: 424–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnable J.C., Freeling M. (2011). Genes identified by visible mutant phenotypes show increased bias toward one of two subgenomes of maize. PLoS One 6: e17855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnable P.S., et al. (2009). The B73 maize genome: complexity, diversity, and dynamics. Science 326: 1112–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz-Sommer Z., Shepherd N., Tacke E., Gierl A., Rohde W., Leclercq L., Mattes M., Berndtgen R., Peterson P.A., Saedler H. (1987). Influence of transposable elements on the structure and function of the A1 gene of Zea mays. EMBO J. 6: 287–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekhon R.S., Lin H., Childs K.L., Hansey C.N., Buell C.R., de Leon N., Kaeppler S.M. (2011). Genome-wide atlas of transcription during maize development. Plant J. 66: 553–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahmuradov I.A., Gammerman A.J., Hancock J.M., Bramley P.M., Solovyev V.V. (2003). PlantProm: a database of plant promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 31: 114–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi W., Zhou W. (2006). Frequency distribution of TATA Box and extension sequences on human promoters. BMC Bioinformatics 7 (suppl. 4): S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiraki T., et al. (2003). Cap analysis gene expression for high-throughput analysis of transcriptional starting point and identification of promoter usage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 15776–15781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smale S.T., Kadonaga J.T. (2003). The RNA polymerase II core promoter. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72: 449–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderlund C., et al. (2009). Sequencing, mapping, and analysis of 27,455 maize full-length cDNAs. PLoS Genet. 5: e1000740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spannagl M., Noubibou O., Haase D., Yang L., Gundlach H., Hindemitt T., Klee K., Haberer G., Schoof H., Mayer K.F. (2007). MIPSPlantsDB--plant database resource for integrative and comparative plant genome research. Nucleic Acids Res. 35: D834–D840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, H., Kato, S., Murata, M., and Carninci, P. (2012). CAGE (Cap Analysis of Gene Expression): A protocol for the detection of promoter and transcriptional networks. In Gene Regulatory Networks: Methods and Protocols, B. Deplancke and N. Gheldof, eds (Totowa, NJ: Humana Press), pp. 181–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thatcher L.F., Carrie C., Andersson C.R., Sivasithamparam K., Whelan J., Singh K.B. (2007). Differential gene expression and subcellular targeting of Arabidopsis glutathione S-transferase F8 is achieved through alternative transcription start sites. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 28915–28928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas-Chollier M., Darbo E., Herrmann C., Defrance M., Thieffry D., van Helden J. (2012). A complete workflow for the analysis of full-size ChIP-seq (and similar) data sets using peak-motifs. Nat. Protoc. 7: 1551–1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C., Hendrickson D.G., Sauvageau M., Goff L., Rinn J.L., Pachter L. (2013). Differential analysis of gene regulation at transcript resolution with RNA-seq. Nat. Biotechnol. 31: 46–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C., Pachter L., Salzberg S.L. (2009). TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics 25: 1105–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu C.J., Park S.Y., Walling L.L. (2003). Isolation and characterization of the neutral leucine aminopeptidase (LapN) of tomato. Plant Physiol. 132: 243–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valen E., Sandelin A. (2011). Genomic and chromatin signals underlying transcription start-site selection. Trends Genet. 27: 475–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace J.G., Bradbury P.J., Zhang N., Gibon Y., Stitt M., Buckler E.S. (2014). Association mapping across numerous traits reveals patterns of functional variation in maize. PLoS Genet. 10: e1004845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Elling A.A., Li X., Li N., Peng Z., He G., Sun H., Qi Y., Liu X.S., Deng X.W. (2009). Genome-wide and organ-specific landscapes of epigenetic modifications and their relationships to mRNA and small RNA transcriptomes in maize. Plant Cell 21: 1053–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Jensen R.C., Stumph W.E. (1996). Role of TATA box sequence and orientation in determining RNA polymerase II/III transcription specificity. Nucleic Acids Res. 24: 3100–3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Zang C., Rosenfeld J.A., Schones D.E., Barski A., Cuddapah S., Cui K., Roh T.Y., Peng W., Zhang M.Q., Zhao K. (2008). Combinatorial patterns of histone acetylations and methylations in the human genome. Nat. Genet. 40: 897–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D., Pethica R., Zhou Y., Talbot C., Vogel C., Madera M., Chothia C., Gough J. (2009). SUPERFAMILY--sophisticated comparative genomics, data mining, visualization and phylogeny. Nucleic Acids Res. 37: D380–D386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin M., et al. (2013). Dynamic expression of imprinted genes associates with maternally controlled nutrient allocation during maize endosperm development. Plant Cell 25: 3212–3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y.Y., Obokata J. (2008). ppdb: a plant promoter database. Nucleic Acids Res. 36: D977–D981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y.Y., Ichida H., Abe T., Suzuki Y., Sugano S., Obokata J. (2007a). Differentiation of core promoter architecture between plants and mammals revealed by LDSS analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 35: 6219–6226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y.Y., Ichida H., Matsui M., Obokata J., Sakurai T., Satou M., Seki M., Shinozaki K., Abe T. (2007b). Identification of plant promoter constituents by analysis of local distribution of short sequences. BMC Genomics 8: 67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y.Y., Yoshitsugu T., Sakurai T., Seki M., Shinozaki K., Obokata J. (2009). Heterogeneity of Arabidopsis core promoters revealed by high-density TSS analysis. Plant J. 60: 350–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., Li D., Cheng C. (2014). Relating gene expression evolution with CpG content changes. BMC Genomics 15: 693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.