Abstract

Background and Aims

Hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury (IRI) is a critical component of hepatic surgery. Oxidative stress has long been implicated as a key player in IRI. In this study, we examine the cell-specific role of the Nrf2-antioxidant response element pathway in warm hepatic IRI.

Methods

Nrf2 KO and WT animals, and novel transgenic mice expressing a constitutively active Nrf2 mutant in hepatocytes (AlbCre+/caNrf2+) and their littermate controls underwent partial hepatic ischemia or sham surgery. The animals were sacrificed 6 hours after reperfusion and their serum and tissue collected for analysis.

Results

As compared to wild type animals after IR, Nrf2 KO mice had increased hepatocellular injury with increased serum ALT and AST, Suzuki score, apoptosis, an increased inflammatory infiltrate and enhanced inflammatory cytokine expression. On the other hand, AlbCre+/caNrf2+ that underwent IR had significantly reduced serum transaminases, less necrosis on histology, and a less pronounced inflammatory infiltrate and inflammatory cytokine expression as compared to the littermate controls. However, there were no differences in apoptosis.

Conclusion

Taken together, Nrf2 plays a critical role in our murine model of warm hepatic IRI, with Nrf2 deficiency exacerbating hepatic IRI and hepatocyte specific Nrf2 over-activation providing protection against warm hepatic IRI.

Keywords: Liver, Knockout, Transgenic, Oxidative Stress, Inflammation

Hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury (IRI) remains a critical and unavoidable component of liver transplantation. In liver transplantation, the requirement of cold preservation-ischemia during the organ recovery process followed by reperfusion in the recipient also results in IRI (1). In severe cases of cold preservation-IRI, hepatocellular damage can result in either early allograft dysfunction (2) or primary non-function of the transplanted allograft (3, 4).

Hepatic IRI is a multifactorial process involving several mechanisms of cellular injury including impaired oxidative metabolism, depletion of ATP, increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and decreased expression of cytoprotective genes (1). Reoxygenation during reperfusion leads to an oxidative burst followed by increased formation of ROS released from activated Kupffer cells, neutrophils, and CD4+ T cells (5, 6). Oxidative damage is considered one of the major invoked mechanisms contributing to hepatocellular injury and organ dysfunction in the setting of hepatic IRI in some animal models. (7-9).

Nrf2 (nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2) is a ubiquitously expressed transcription factor central to gene expression of major phase II detoxification enzymes and antioxidant proteins. Under basal cellular conditions, most Nrf2 molecules remain bound in the cytoplasm to the regulatory protein, Kelch-like ECH-Associated Protein (Keap1), and undergo subsequent degradation via the ubiquitin-proteosome pathway in a Keap1-dependent manner. During oxidative or electrophilic stress, oxidants modify cysteine residues of Keap1, resulting in stabilization of Nrf2, which allows for nuclear translocation of newly synthesized Nrf2 (10, 11). Once in the nucleus, Nrf2 binds to the cis-acting element called the antioxidant responsive element (ARE) that regulates both constitutive and inducible gene expression in response to oxidative stress (12, 13).

The protective effects of the Nrf2-ARE pathway have been previously described in IRI models of the kidney (14), heart (15), brain (16, 17), and liver (18). All of these studies utilized Nrf2 knockout (KO) mice and demonstrated increased tissue damage in the absence of Nrf2. Since multiple cells in the liver are involved in hepatic IRI, the effects of cell-specific Nrf2 induction in warm hepatic IRI remain unknown. The primary focus of these studies was to assess the cell-specific protective effects of the Nrf2-ARE pathway in a murine model of warm hepatic IRI. To achieve this aim, we first compared the impact of hepatic IRI in Nrf2 KO and wild-type (WT) mice. We then utilized transgenic mice expressing a constitutively active Nrf2 (caNrf2) mutant in hepatocytes to assess the impact of cell-specific over-activation of Nrf2 during IRI. More specifically, we assessed whether over-activation of Nrf2 in hepatocytes alone is sufficient to reduce hepatocellular damage, necrosis, apoptosis, and inflammation in a murine model of warm hepatic IRI.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Nrf2 KO mice (19) and mice with expression of a constitutively active Nrf2 mutant (caNrf2) under the control of a CMV promoter and β-actin enhancer (20) in hepatocytes (21) have previously been described. The caNrf2 sequence is preceded by a floxed transcription/translation STOP cassette. Upon mating these mice with transgenic mice expressing Cre in hepatocytes under control of the albumin promoter (AlbCre mice) (Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor, ME), the STOP cassette is excised and caNrf2 is expressed in a hepatocyte-specific manner. The caNrf2 protein cannot bind to Keap1 and is constitutively present in the nucleus to induce Nrf2 target genes expression. Baseline analysis of the transgenic mice with hepatocyte-specific over-activation of Nrf2 revealed significantly elevated Nrf2-dependent genes and proteins compared to littermate controls (22). All the transgenic lines employed in the experiments described in this report were on a C57BL/6J background.

Nrf2 KO and WT mice (age 6-12 weeks) were subjected to either sham (KO: n=4; WT: n=4) or partial hepatic ischemia surgery (KO: n=16; WT: n=13). Animals that underwent sham surgery only had laparotomy performed, followed by abdominal closure. For partial hepatic ischemia surgery, a vascular clip was applied to the left pedicle of the portal triad to render 70% of the liver ischemic. Ischemia was verified by visual confirmation. After 30 minutes of ischemia, the vascular clip was removed to allow for reperfusion, followed by abdominal closure. Six hours after the procedure, all animals were sacrificed, and liver and serum samples were collected for analysis.

In the second set of experiments, transgenic mice with hepatocyte-specific over-activation of Nrf2 (AlbCre+/caNrf2+) and littermate controls (AlbCre+/caNrf2-) (age 6-12 weeks) were subjected to either sham (AlbCre+/caNrf2+: n=3; AlbCre+/caNrf2-: n=3) or partial hepatic ischemia (AlbCre+/caNrf2+: n=8; AlbCre+/caNrf2-: n=6) for 60 minutes followed by 6 hours of reperfusion in each experimental group). Mice were then sacrificed and the liver and serum samples were collected for analysis. All experiments were performed according to the ethical guidelines outlined in the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

Histology

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded livers were sectioned, and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained slides were reviewed by two pathologists (K.A.M and S.C.) to determine histological features. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed as previously described, using rabbit anti-cleaved Caspase 3 (Epitomics, Burlingame, CA) or rat anti-Ly6G (Biolegend, San Diego, CA) primary antibodies (25) to determine the extent of apoptosis and neutrophilic infiltration, respectively. Briefly, sections (5μm) were deparaffinized, rehydrated in alcohols, and subjected to heat-induced epitope retrieval in 0.1M citrate buffer at pH 6.0 in a microwave for 20 minutes. Slides were then incubated with anti-cleaved Caspase 3 (1:1000) or anti-Ly6G (1:1000) antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. After incubation with secondary antibody, a subsequent reaction was performed with biotin-free horseradish peroxidase enzyme-labeled polymer, 3,3′-diaminobenzidine was used as the chromogen, and sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

Image Analysis

The slides for each animal were visualized under light microscopy using an Axiovert 200M microscope (Carl Zeiss, Gottingen, Germany). Four random high-powered fields of view were taken for each animal.

Serum Analysis

Whole blood was collected at the time of sacrifice, and allowed to coagulate at room temperature for 30 minutes before centrifugation to collect serum. Serum ALT and AST were measured using the IDEXX VetTest Chemistry Analyzer (IDEXX, Westbrook, ME).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Quantitative RT-PCR was performed to assess pro-inflammatory mediators and cytokines as previously described (22). The analysis was performed by normalizing the mRNA abundance of each gene of interest to the β-actin mRNA abundance of the sample, and then each experimental group was normalized to either the Nrf2 WT sham or AlbCre+/caNrf2- sham group, as appropriate. The primer sequences used are listed in the supplemental materials.

Western Blot

Three random sham animals and four IRI animals from each experimental group were used for Western blot analysis of apoptosis. Western blotting using anti-cleaved Caspase 3, anti-caspase 3 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), and anti-β-actin (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) primary antibodies was performed as previously described (22).

Statistics

All data in figures are presented as mean ± SEM. Comparisons between the groups were performed with either one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s LSD post hoc test, or Student’s t-test where appropriate. Log transformation was performed as appropriate as determined by Levene’s test for equality of variance. P<0.05 was used for statistical significance. All statistical tests were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 22.

Results

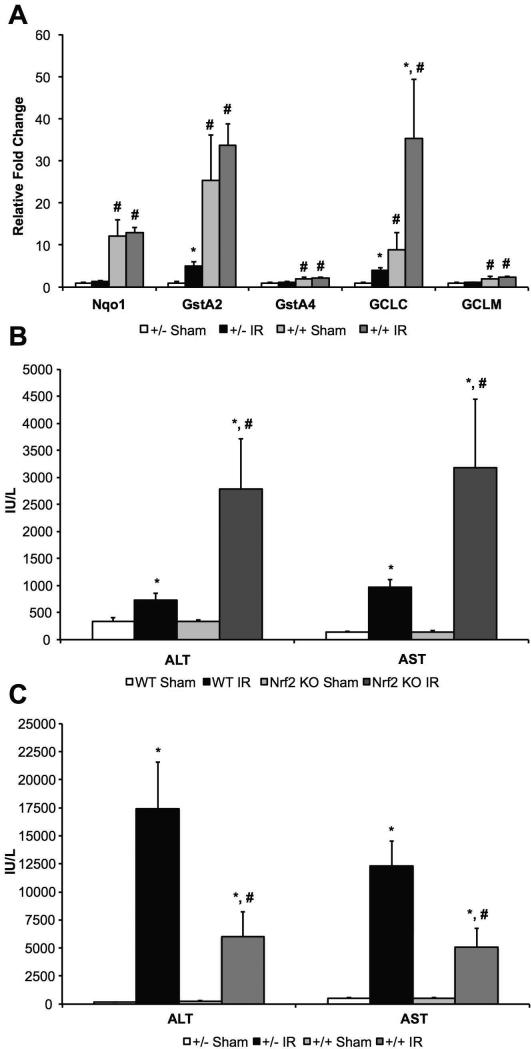

Basal and inducible levels of Nrf2-dependent genes after hepatic IRI

To assess the impact of hepatic IRI on Nrf2-dependent gene expression, we performed qRT-PCR for a panel of Nrf2-dependent genes in the livers of AlbCre+/caNrf2- and AlbCre+/caNrf2+ mice following sham surgery and IRI (Figure 1A). In the AlbCre+/caNrf2- mice, IRI resulted in significant increases in mRNA abundance of two of the five genes assessed (GSTA2, 5-fold; GCLC, 4-fold). IRI did not alter the gene expression for NQO1, GSTA4, and GCLM. In the AlbCre+/caNrf2+ mice, mRNA abundance of GCLC (4-fold) was significantly elevated after IRI compared to sham surgery. However, there were no changes in NQO1, GSTA2, GSTA4, and GCLM mRNA abundance in these mice after IRI compared to sham surgery. In contrast, basal levels of all five Nrf2-dependent genes tested were significantly elevated in the livers of AlbCre+/caNrf2+ mice compared to AlbCre+/caNrf2- mice. The greatest increases in basal expression were observed with GSTA2 (25-fold), NQO1 (12-fold), and GCLC (9-fold). These data suggest that changes seen with the AlbCre+/caNrf2+ mice in comparison to AlbCre+/caNrf2- mice after IRI are more likely related to increased basal levels of Nrf2-ARE pathway activity and less likely from changes in expression of Nrf2-dependent genes upon IRI.

Figure 1. Nrf2-dependent gene expression and serum ALT/AST levels following hepatic IRI.

Hepatic mRNA levels of Nqo1, GstA2, GstA4, GCLC, and GCLM in (A) AlbCre+/caNrf2- and AlbCre+/caNrf2+ mice subjected to sham and IR surgery. Serum transaminases following sham or IR surgery in (B) Nrf2 WT and KO mice and (C) AlbCre+/caNrf2- and AlbCre+/caNrf2+ mice (AlbCre+/caNrf2+ Sham: n=3; AlbCre+/caNrf2- Sham: n=3; AlbCre+/caNrf2+ IR: n=8; AlbCre+/caNrf2- IR: n=6; WT Sham: n=4; KO Sham: n=4; WT IR: n=13; KO IR: n=16). * P<0.05 compared to sham surgery of the same genotype. # P<0.05 compared to control genotype of the same surgery.

The Nrf2-ARE Pathway Protects from Hepatocellular Damage after Warm Hepatic IRI

Nrf2 KO and WT mice were subjected to either sham surgery or 30 minutes of ischemia followed by 6 hours of reperfusion. Serum ALT and AST levels were measured as markers of hepatocellular damage. Nrf2 KO and WT mice undergoing IRI had significantly higher serum ALT and AST compared to sham animals of the same genotype. Nrf2 KO mice undergoing IRI demonstrated significantly higher ALT and AST levels when compared to Nrf2 WT mice undergoing IRI (Figure 1B).

Next, AlbCre+/caNrf2+ and AlbCre+/caNrf2- mice were subjected to 60 minutes of ischemia followed by 6 hours of reperfusion. Serum levels of AST and ALT were significantly elevated in mice undergoing IRI, when compared to sham animals of the same genotype. However, serum AST and ALT levels were significantly lower in AlbCre+/caNrf2+ mice compared to littermate controls (Figure 1C).

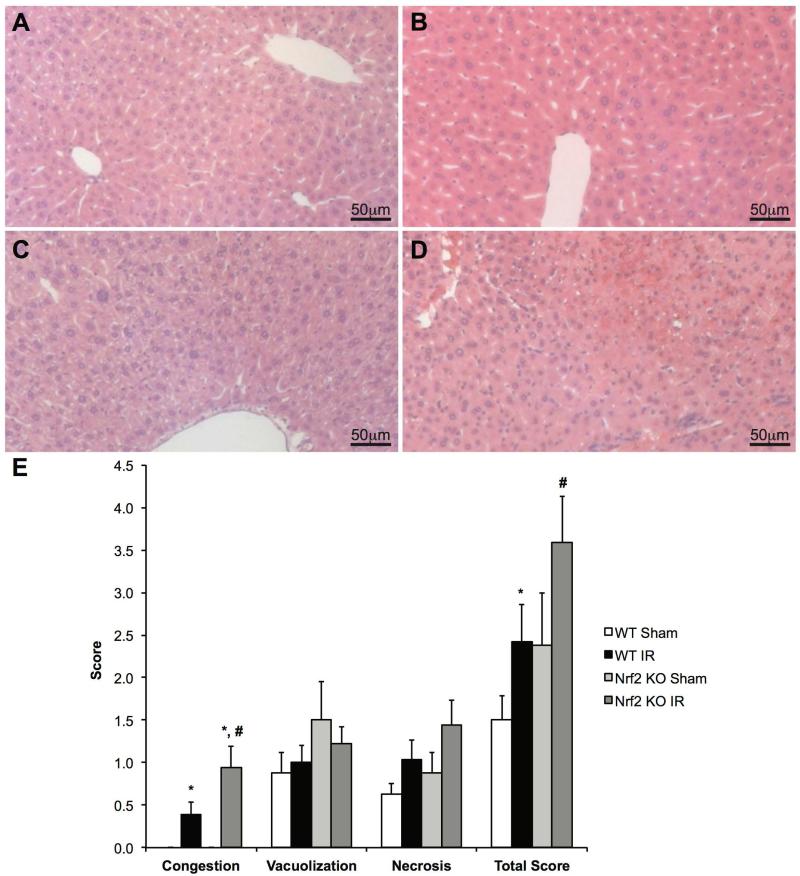

Histologic analysis was also performed to assess the degree of hepatic damage among the groups after IRI. H&E slides were reviewed by two independent pathologists (KAM and SC) in a blinded manner. H&E slides were scored using Suzuki’s scoring method, as previously published (23). The Suzuki score is based on an assessment of sinusoidal congestion, cytoplasmic vacuolization, necrosis, and an additive total score. Representative liver sections from the Nrf2 KO and WT mice are depicted in Figures 2A-2D. Sinusoidal congestion was significantly higher in mice undergoing IRI compared to mice of the same genotype undergoing sham surgery. In mice undergoing IRI, sinusoidal congestion was significantly greater in the Nrf2 KO mice when compared to Nrf2 WT mice. However, no differences were seen with regard to vacuolization or necrosis among the four groups. In mice undergoing IRI, the total Suzuki score was significantly greater in Nrf2 KO mice when compared to Nrf2 WT mice (Figure 2E).

Figure 2. Nrf2 deficiency increases damage following IRI.

Representative H&E staining in livers of Nrf2 WT (A and B) and Nrf2 KO (C and D) mice subjected to either sham (A and C) or IR (B and D) surgery. (E) Suzuki scoring of the H&E liver sections for congestion, vacuolization, necrosis, and additive total score (WT Sham: n=4; KO Sham: n=4; WT IR: n=13; KO IR: n=16). * P<0.05 compared to sham surgery of the same genotype. # P<0.05 compared to control genotype of the same surgery.

Liver tissue from the AlbCre+/caNrf2+ and AlbCre+/caNrf2- mice was stained with H&E, and representative sections are shown in Figures 3A-3D. Sinusoidal congestion and necrosis were significantly greater in mice undergoing IRI compared to sham surgery within the same genotype. Over-activation of Nrf2 in AlbCre+/caNrf2+ mice did not alter the degree of congestion or vacuolization after IRI when compared to littermate controls. However, the extent of cellular necrosis was significantly reduced in the livers of AlbCre+/caNrf2+ mice undergoing IRI compared to littermate control mice (Figure 3E).

Figure 3. Hepatocyte-specific Nrf2 over-activation reduces necrosis following IRI.

Representative H&E staining in livers of AlbCre+/caNrf2- (A and B) and AlbCre+/caNrf2+ (C and D) mice subjected to either sham (A and C) or IR (B and D) surgery. (E) Suzuki scoring of the H&E liver sections for congestion, vacuolization, necrosis, and additive total score (AlbCre+/caNrf2+ Sham: n=3; AlbCre+/caNrf2- Sham: n=3; AlbCre+/caNrf2+ IR: n=8; AlbCre+/caNrf2- IR: n=6). * P<0.05 compared to sham surgery of the same genotype. # P<0.05 compared to control genotype of the same surgery.

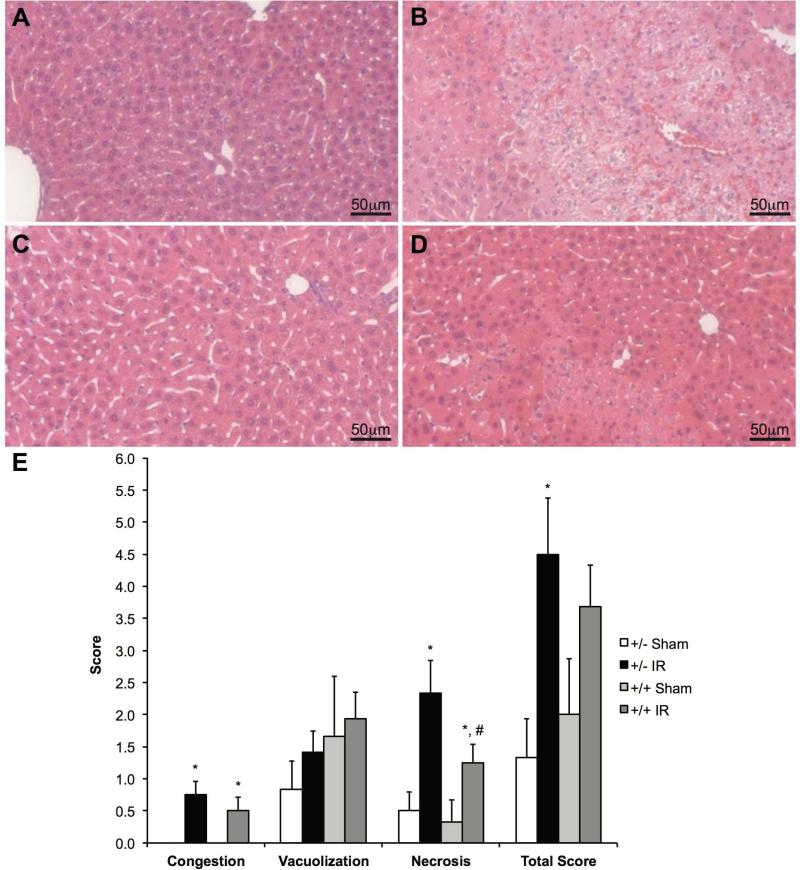

Global Absence of Nrf2 Leads to Increased Apoptosis in Warm Hepatic IRI

Apoptosis after hepatic IRI was assessed using both histological and Western blot analyses. The activation of apoptotic caspases is considered a critical component of most apoptotic processes (24); thus, we measured the amount of cleaved Caspase 3 as a marker of cellular apoptosis in our experiments. Immunohistochemistry for cleaved Caspase 3 was performed on tissue samples from Nrf2 KO and WT mice and representative sections are demonstrated in Figures 4A-4D. Qualitatively, sham animals (Figures 4A and 4C) demonstrated no cleaved Caspase 3 staining. Despite the presence of increased cellular damage in the livers of Nrf2 WT mice undergoing IRI (Figure 4B) compared to sham animals (Figure 4A), minimal to no cleaved Caspase 3 staining was identified. In contrast, a large amount of cleaved Caspase 3 staining was observed in the livers of Nrf2 KO mice undergoing IRI (Figure 4D), as compared to the sham (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Nrf2 deficiency increases apoptosis following IRI.

Representative cleaved Caspase 3 staining in livers of Nrf2 WT (A and B) and Nrf2 KO (C and D) mice subjected to either sham (A and C) or IR (B and D) surgery (WT Sham: n=4; KO Sham: n=4; WT IR: n=13; KO IR: n=16). (E) Western blot analysis and (F) densitometry of cleaved Caspase 3 protein following sham or IR surgery.* P<0.05 compared to sham surgery of the same genotype. # P<0.05 compared to control genotype of the same surgery.

Western blot of cleaved Caspase 3 was performed to quantify the protein levels (Figures 4E and 4F). No differences in cleaved Caspase 3 protein levels were observed among the Nrf2 WT mice undergoing either sham or IR surgery. In contrast, cleaved Caspase 3 protein levels were significantly elevated in Nrf2 KO mice undergoing IRI when compared to both Nrf2 KO mice undergoing sham surgery and Nrf2 WT mice undergoing IRI. These data confirm the histological findings and suggest the presence of Nrf2 in all cells of the liver plays a protective role by decreasing apoptosis in warm hepatic IR.

Constitutive Activation of Nrf2 in Hepatocytes Alone Does Not Affect Apoptosis after Warm Hepatic IRI

Cleaved Caspase 3 immunohistochemistry was performed on livers isolated from AlbCre+/caNrf2+ and AlbCre+/caNrf2- after sham and IR surgery with 60 minutes of ischemia and 6 hours of reperfusion. Representative sections are depicted in Figures 5A-5D. No demonstrable cleaved Caspase 3 was seen in the livers of mice undergoing sham surgery (Figures 5A and 5C). In contrast, cleaved Caspase 3 staining was seen around necrotic areas in the livers of AlbCre+/caNrf2+ and AlbCre+/caNrf2- mice after IRI (Figures 5B and 5D)

Figure 5. Nrf2 over-activation in hepatocytes does not ameliorate the increased apoptosis following IRI.

Representative cleaved Caspase 3 staining in livers of AlbCre+/caNrf2- (A and B) and AlbCre+/caNrf2+ (C and D) mice subjected to either sham (A and C) or IR (B and D) surgery (AlbCre+/caNrf2+ Sham: n=3; AlbCre+/caNrf2- Sham: n=3; AlbCre+/caNrf2+ IR: n=8; AlbCre+/caNrf2- IR: n=6). (E) Western blot analysis and (F) densitometry of cleaved Caspase 3 protein following sham or IR surgery. * P<0.05 compared to sham surgery of the same genotype. # P<0.05 compared to control genotype of the same surgery.

To quantify the protein level of cleaved Caspase 3 in these livers, we performed Western blot analysis (Figures 5E and 5F). Cleaved Caspase 3 protein levels were significantly elevated in both AlbCre+/caNrf2+ and AlbCre+/caNrf2- mice subjected to IRI, as compared to control mice undergoing sham surgery. However, cleaved Caspase 3 protein levels were similar between AlbCre+/caNrf2+ and AlbCre+/caNrf2- mice undergoing IRI. These data suggest that hepatocyte-specific over-activation of Nrf2 is not sufficient to reduce cellular apoptosis resulting from hepatic IRI.

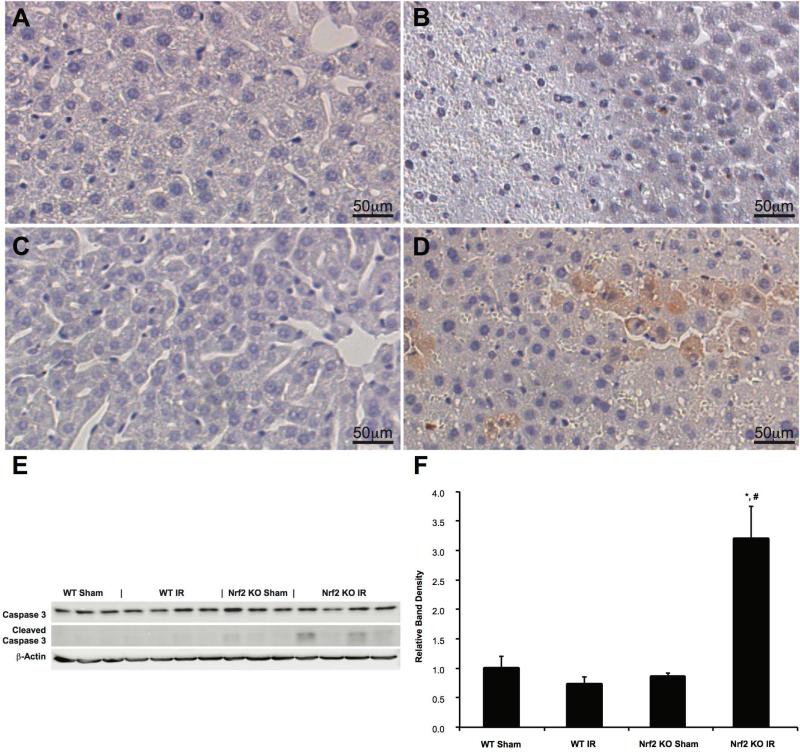

Activation of the Nrf2-ARE Pathway Decreases Inflammation Secondary to Warm Hepatic IRI

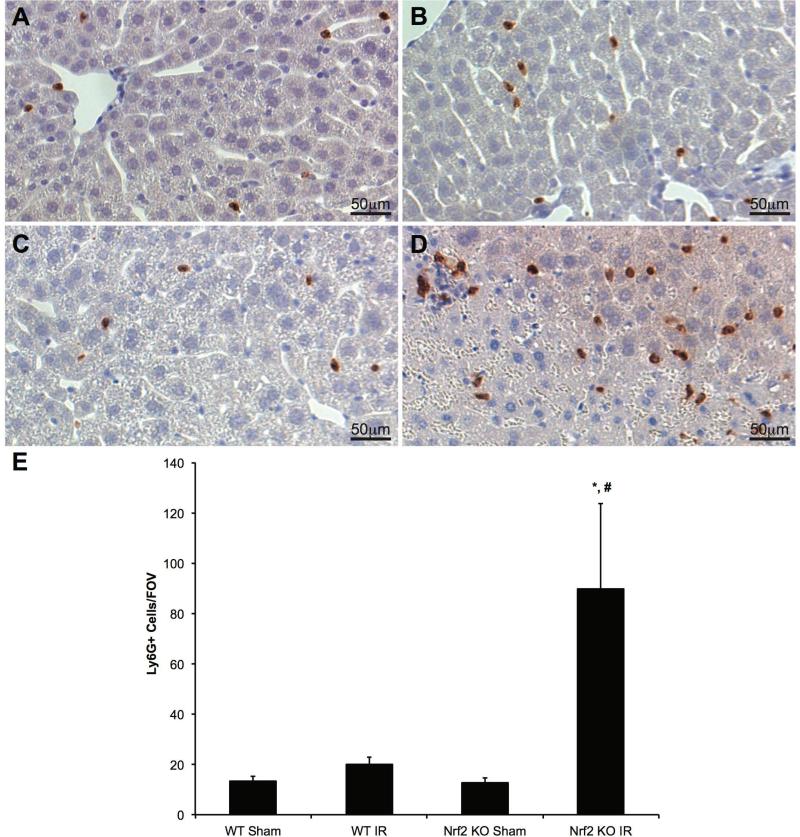

Hepatic inflammation is a well described component of IRI occurring within the first few hours of reperfusion (8). We investigated the impact of both the absence of Nrf2 and hepatocyte-specific over-activation of Nrf2 on the degree of inflammation in our models. Hepatic inflammation was assessed on liver section with IHC using primary antibody against Ly6G, a neutrophil marker. ImageJ was used to count the number of neutrophils per field of view. Representative images of liver specimens are shown in Figures 6A-6D. There were no significant differences in neutrophilic infiltration among Nrf2 WT mice undergoing either sham or IR surgery or with Nrf2 KO mice undergoing sham surgery. However, there were a significantly higher number of neutrophils in the livers of Nrf2 KO mice that underwent IRI when compared to both Nrf2 KO mice undergoing sham surgery and Nrf2 WT mice undergoing IRI (Figure 6E). These data demonstrate that the global absence of Nrf2 leads to an increase in neutrophilic infiltration and inflammation after hepatic IRI.

Figure 6. Nrf2 deficiency increases neutrophil infiltration following IRI.

Representative Ly6G staining in livers of Nrf2 WT (A and B) and Nrf2 KO (C and D) mice subjected to either sham (A and C) or IR (B and D) surgery. (E) Ly6G-positive cells were quantified from four random fields of each section at 20X magnification (WT Sham: n=4; KO Sham: n=4; WT IR: n=13; KO IR: n=16). * P<0.05 compared to sham surgery of the same genotype. # P<0.05 compared to control genotype of the same surgery.

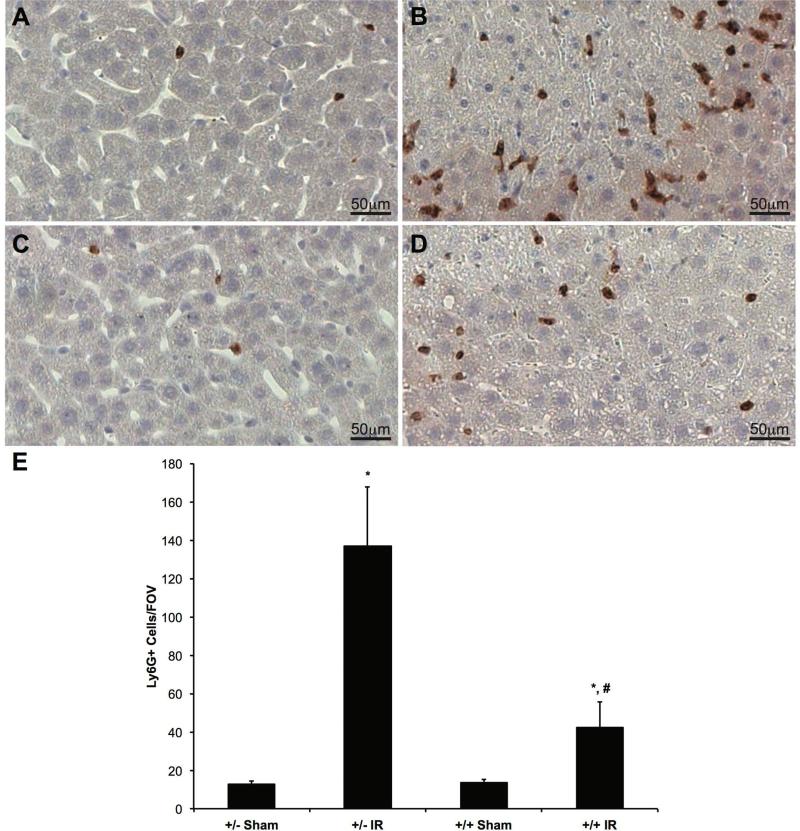

We also performed IHC with anti-Ly6G antibody on liver specimens from AlbCre+/caNrf2+ and AlbCre+/caNrf2- mice. Representative images are shown in Figures 7A-7D. IR surgery resulted in a significantly greater number of neutrophils per field of view in mice compared to sham surgery within the same genotype. Importantly, hepatocyte-specific over-activation of Nrf2 led to a significant reduction in neutrophil count after IR surgery when compared to littermate control mice (Figure 7E), indicating reduced inflammation.

Figure 7. Nrf2 over-activation in hepatocytes reduces neutrophilic infiltration following IRI.

Representative Ly6G staining in livers of AlbCre+/caNrf2- (A and B) and AlbCre+/caNrf2+ (C and D) mice subjected to either sham (A and C) or IR (B and D) surgery. (E) Ly6G-positive cells were quantified from four random fields of each section at 20X magnification (AlbCre+/caNrf2+ Sham: n=3; AlbCre+/caNrf2- Sham: n=3; AlbCre+/caNrf2+ IR: n=8; AlbCre+/caNrf2- IR: n=6). * P<0.05 compared to sham surgery of the same genotype. # P<0.05 compared to control genotype of the same surgery.

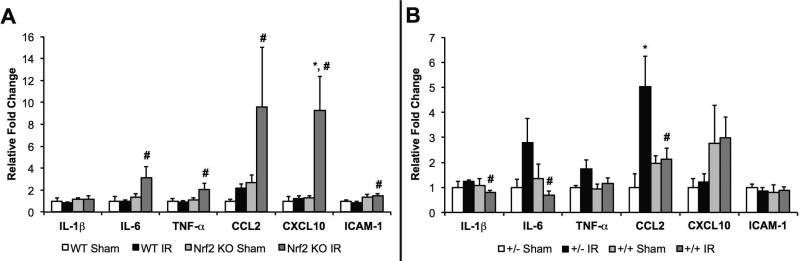

We also performed qRT-PCR to measure the hepatic mRNA abundance of proinflammatory genes, including IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, CCL2, CXCL10 and ICAM-1. There were no differences in mRNA abundance of these genes in the livers isolated from the Nrf2 WT sham, Nrf2 WT IRI, and Nrf2 KO sham mice. However, IL-6, TNF-α, CCL2, CXCL10 and ICAM-1 gene expression were significantly elevated in the livers of Nrf2 KO mice compared to Nrf2 WT mice after IRI (Figure 8A), suggesting an increased inflammatory response in the absence of Nrf2.

Figure 8. Nrf2 attenuates the upregulation of pro-inflammatory gene expression following hepatic IRI.

Hepatic mRNA levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, CCL2, CXCL10, and ICAM-1 in (A) Nrf2 WT and KO mice and (B) AlbCre+/caNrf2- and AlbCre+/caNrf2+ mice subjected to either sham (WT: n=4; KO: n=4; AlbCre+/caNrf2+: n=3; AlbCre+/caNrf2-: n=3) or IR surgery (WT: n=13; KO: n=16; AlbCre+/caNrf2+: n=8; AlbCre+/caNrf2-: n=6). * P<0.05 compared to sham surgery of the same genotype. # P<0.05 compared to control genotype of the same surgery.

Similar analyses were performed on the livers isolated from AlbCre+/caNrf2+ and AlbCre+/caNrf2- mice. There were no differences in mRNA abundance of proinflammatory genes among the AlbCre+/caNrf2- mice undergoing sham or IR surgery or in AlbCre+/caNrf2+ mice undergoing sham surgery with the exception of CCL2. CCL2 expression was significantly greater in AlbCre+/caNrf2- mice undergoing IRI compared to sham surgery. Hepatocyte-specific over-activation of Nrf2 in AlbCre+/caNrf2+ mice resulted in reduced expression of IL-1β, IL-6, and CCL2 when compared to AlbCre+/caNrf2- mice that underwent IRI (Figure 8B). These data demonstrate that over-activation of Nrf2 in hepatocytes leads to reduced inflammation during the early phase of IRI.

Discussion

Hepatic IRI remains a critical, deleterious process leading to significant morbidity in patients undergoing liver resection surgery or liver transplantation. Because oxidative stress is one of the major mechanisms involved in the development of IRI, we chose to study whether the induction of an endogenous antioxidant pathway, the Nrf2-ARE pathway, can lead to a reduction in cell damage in a murine model of warm hepatic IRI. Although previous studies have demonstrated that the absence of Nrf2 can lead to worsening of hepatic IRI (21, 29), the impact of cell-specific induction of the Nrf2-ARE pathway in warm hepatic IRI has not been previously explored.

In these experiments, we utilized multiple strains of transgenic mice to assess the impact of Nrf2 on warm hepatic IRI. Nrf2 KO mice subjected to 30 minutes of warm ischemia followed by 6 hours of reperfusion demonstrated increased hepatocellular damage, apoptosis, and inflammation compared to Nrf2 WT mice. The increased inflammation was demonstrated by neutrophilic infiltration into the liver and a higher mRNA abundance of pro-inflammatory genes in the livers of Nrf2 KO compared to WT mice. AlbCre+/caNrf2+ mice that underwent 60 minutes of warm ischemia followed by 6 hours of reperfusion demonstrated decreased hepatocellular damage, decreased necrosis, and reduced inflammatory infiltrate.

We also measured Nrf2-dependent gene expression at baseline and after IRI in the AlbCre+/caNrf2- and AlbCre+/caNrf2+ mice. In the AlbCre+/caNrf2- mice, only two of the five genes were modestly elevated above baseline after IRI. In the AlbCre+/caNrf2+ mice, only one of the genes was significantly elevated above the sham control mice. In contrast, the expressions of all Nrf2-dependent genes in the AlbCre+/caNrf2+ mice were significantly elevated at baseline compared to controls. Taken together, these data suggest that the basal level of Nrf2 activity prior to IRI is responsible for the mitigation of warm hepatic IRI. Future studies that investigate the use of pharmacological agents aimed at Nrf2 induction should be given prior to the onset of hepatic IRI to maximize cellular protection.

With our different mice strains, we utilized different lengths of ischemia for our experiments. While this makes the comparisons between the sets of experiments more difficult, this was done to better differentiate the effects of Nrf2 absence and over- activation. In previous Nrf2 KO vs. WT experiments, we performed 60 minutes of warm ischemia followed by 6 hours of reperfusion. Both WT and KO mice demonstrated significantly elevated serum transaminases with IRI with no significant difference between genotypes (See Supplementary Data). As there are only a limited number of hepatocytes available to reflect the total amount of damage, we suspected 60 minutes of warm ischemia was too great of an insult to the murine liver in our model. Thus, for WT and KO animals, we decreased the ischemia time to 30 minutes in order to assess whether differences in hepatocellular protection existed. For the AlbCre/caNrf2 animals, 60 minutes of ischemia provided an adequate level of insult for us to delineate the differential effects of injury between the hepatic Nrf2 over-activators and their littermate controls.

Our findings with Nrf2 WT and KO mice are similar to those that have previously been described. Kudoh et al. were the first to describe increased warm hepatic IRI in Nrf2 KO mice using a model of 60 minutes of ischemia with 6 hours of reperfusion. Livers from the Nrf2 KO mice exhibited enhanced tissue damage, impaired Nrf2-dependent gene induction, and increased TNF-α mRNA when compared to Nrf2 WT (18). In another study using a warm hepatic IRI model of 90 minutes of ischemia followed by 6 hours of reperfusion, Huang et al. reported increased hepatocellular damage, apoptosis, and increased inflammation in Nrf2 KO mice when compared Nrf2 WT control mice (25). Each of these studies modeled different degrees of injury based on varying ischemic times. Despite the differences in times of ischemia, these previous studies and our findings support the protective effects of the Nrf2-ARE pathway in warm hepatic IRI models, across a spectrum of injury patterns.

The novelty of our study is that we are the first group to investigate the impact of cell-specific activation of Nrf2 signaling in warm hepatic IRI using a well-characterized caNrf2 construct (20, 21). By utilizing the caNrf2 construct, which directly activates the Nrf2-ARE pathway, we can specifically assess the effects of Nrf2-ARE pathway activation. Pharmacological activation of the Nrf2-ARE pathway may be less efficacious and less specific than our transgenic model. In addition, Nrf2-independent effects of pharmacological activators cannot be excluded (26). By utilizing the caNrf2 construct in our studies, we are better able to exclude Nrf2-independent effects that may be seen with pharmacological activation or Keap1 deficiency.

We previously observed that genetic, over-activation of Nrf2 in hepatocytes leads to reduced hepatocellular damage and steatosis in a dietary model of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (22). However, over-activation of Nrf2 in hepatocytes alone was not sufficient to mitigate the oxidative stress and inflammation in this model. These data suggested that Nrf2 induction in non-parenchymal cells of the liver may be responsible for the reduction in inflammation and oxidative stress that have been seen in previous studies utilizing Nrf2 KO and WT mice (27). In the studies described here, over-activation of Nrf2 in hepatocytes at baseline led to reduced hepatocellular damage, cellular necrosis, and hepatic inflammation after warm hepatic IRI. These findings are similar to those seen in Nrf2 WT mice compared to Nrf2 KO mice after warm hepatic IRI. The data suggest that elevated basal activity of Nrf2-ARE in hepatocytes is an important cellular defense mechanism to combat the inflammatory response and oxidative stress after warm hepatic IRI.

Genetic activation of Nrf2 has been previously tested in a cold preservation IRI model. Ke et al. used Keap1 hepatocyte-specific knockout (HKO) mice to assess the impact of Nrf2 activation in a murine liver transplant model (28). Liver transplants from Keap1 HKO donors showed reduced hepatocellular damage, decreased inflammatory cell trafficking, and prolonged survival compared to control donor livers from Nrf2 WT and KO mice. Although the Keap1 HKO mice have demonstrable increases in Nrf2-dependent proteins in hepatocytes, it is uncertain if Keap1 plays a role in Nrf2-independent pathways. The studies that we describe here are different as they employ a more specific transgenic model for hepatocyte-directed Nrf2 over-activation, and the effects of this induction were tested in a warm hepatic IRI model.

It is well recognized that both necrotic and apoptotic cell death are active processes occurring after warm hepatic IRI (29). Although some have suggested that necrosis, and not apoptosis, is the dominant form of cell death after warm hepatic IRI (30, 31), others have supported the view that apoptosis is a central mechanism of injury (32). The latter view is supported by experiments involving blockade of apoptotic pathways, which leads to reduced cell damage after warm hepatic IRI (33).

By studying the degree of apoptosis, we obtained differential results. In the Nrf2 KO and WT experiments, livers from Nrf2 KO mice demonstrated significantly increased cleaved Caspase 3 staining on IHC and greater protein levels on immunoblot compared to WT mice. This is similar to what others have shown with Nrf2 KO mice (25). However, when apoptosis was studied in livers from the AlbCre+/caNrf2+ and AlbCre+/caNrf2- mice subjected to IRI, no differences in apoptosis were seen. The basal level of Nrf2-ARE pathway activation in the AlbCre+/caNrf2+ mice was sufficient to mitigate the overall cellular damage and inflammation after warm hepatic IRI; therefore, we do not suspect that the lack of changes in apoptosis is due to insufficient Nrf2-ARE induction in hepatocytes. While it is possible that our model lacks the sensitivity to biologically induce and detect differences in apoptosis, there remains the possibility that Nrf2 induction in non-parenchymal liver cells is responsible for the overall reduction in apoptosis seen in the Nrf2 WT and KO experiments.

In conclusion, Nrf2 deficiency leads to increased hepatocellular damage, apoptosis, and inflammation in a murine model of warm hepatic IRI. Complementarily, Nrf2 over-activation in a hepatocyte-specific manner results in decreased hepatocellular damage, necrosis, and inflammation, but no difference in apoptosis. Basal Nrf2 activity undoubtedly plays an important protective role in the early phase of hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury. However, the findings in these studies of warm hepatic IRI need to be tested further in models of cold preservation IRI to determine if protection can be seen in the setting of liver transplantation. Future studies are required to elucidate the cell-specific mechanisms of Nrf2-mediated protection during the late phases of warm hepatic IRI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support

The project described was supported by Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program through the National Institutes of Health Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) [UL1TR000427](D.P.F.) The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The project was also supported by the American Society of Transplant Surgeons-Pfizer Mid-Level Faculty Award (D.P.F.), National Institutes of Health (T32 CA0900217 to L.-Y.L.), and the Swiss National Science Foundation (310030_132884 to S.W.)

Abbreviations

- ARE

antioxidant response element

- CCL2

chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2

- CXCL10

chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10

- GCLC

glutamate-cysteine ligase, catalytic subunit

- GCLM

glutamate-cysteine ligase, modifier subunit

- GstA2

glutathione S-transferase alpha 2

- GstA4

glutathione S-transferase alpha 4

- ICAM1

intercellular adhesion molecule 1

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- IL

interleukin

- IRI

ischemia-reperfusion injury

- Keap1

Kelch-like ECH-associated protein

- Nrf2

Nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2

- Nqo1

NAD(P)H dehydrogenase, quinone 1

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time reverse-transcriptase PCR

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Data

Additional information is available in the supplementary data.

References

- 1.Clavien PA, Harvey PR, Strasberg SM. Preservation and reperfusion injuries in liver allografts. An overview and synthesis of current studies. Transplantation. 1992;53(5):957–78. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199205000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olthoff KM, Kulik L, Samstein B, Kaminski M, Abecassis M, Emond J, et al. Validation of a current definition of early allograft dysfunction in liver transplant recipients and analysis of risk factors. Liver transplantation : official publication of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the International Liver Transplantation Society. 2010;16(8):943–9. doi: 10.1002/lt.22091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ploeg RJ, D'Alessandro AM, Knechtle SJ, Stegall MD, Pirsch JD, Hoffmann RM, et al. Risk factors for primary dysfunction after liver transplantation--a multivariate analysis. Transplantation. 1993;55(4):807–13. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199304000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briceno J, Ciria R, Pleguezuelo M, de la Mata M, Muntane J, Naranjo A, et al. Impact of donor graft steatosis on overall outcome and viral recurrence after liver transplantation for hepatitis C virus cirrhosis. Liver transplantation : official publication of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the International Liver Transplantation Society. 2009;15(1):37–48. doi: 10.1002/lt.21566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaeschke H, Farhood A. Neutrophil and Kupffer cell-induced oxidant stress and ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat liver. The American journal of physiology. 1991;260(3 Pt 1):G355–62. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1991.260.3.G355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaeschke H, Bautista AP, Spolarics Z, Spitzer JJ. Superoxide generation by neutrophils and Kupffer cells during in vivo reperfusion after hepatic ischemia in rats. Journal of leukocyte biology. 1992;52(4):377–82. doi: 10.1002/jlb.52.4.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaeschke H, Woolbright BL. Current strategies to minimize hepatic ischemiareperfusion injury by targeting reactive oxygen species. Transplantation reviews. 2012;26(2):103–14. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaeschke H. Reactive oxygen and mechanisms of inflammatory liver injury: Present concepts. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2011;26(Suppl 1):173–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taneja C, Prescott L, Koneru B. Critical preservation injury in rat fatty liver is to hepatocytes, not sinusoidal lining cells. Transplantation. 1998;65(2):167–72. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199801270-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Itoh K, Wakabayashi N, Katoh Y, Ishii T, Igarashi K, Engel JD, et al. Keap1 represses nuclear activation of antioxidant responsive elements by Nrf2 through binding to the amino-terminal Neh2 domain. Genes & development. 1999;13(1):76–86. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.1.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki T, Motohashi H, Yamamoto M. Toward clinical application of the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Trends in pharmacological sciences. 2013;34(6):340–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rushmore TH, Morton MR, Pickett CB. The antioxidant responsive element. Activation by oxidative stress and identification of the DNA consensus sequence required for functional activity. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1991;266(18):11632–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wasserman WW, Fahl WE. Functional antioxidant responsive elements. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94(10):5361–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu M, Grigoryev DN, Crow MT, Haas M, Yamamoto M, Reddy SP, et al. Transcription factor Nrf2 is protective during ischemic and nephrotoxic acute kidney injury in mice. Kidney international. 2009;76(3):277–85. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, Sano M, Shinmura K, Tamaki K, Katsumata Y, Matsuhashi T, et al. 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal protects against cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury via the Nrf2-dependent pathway. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2010;49(4):576–86. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah ZA, Li RC, Thimmulappa RK, Kensler TW, Yamamoto M, Biswal S, et al. Role of reactive oxygen species in modulation of Nrf2 following ischemic reperfusion injury. Neuroscience. 2007;147(1):53–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.02.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shih AY, Li P, Murphy TH. A small-molecule-inducible Nrf2-mediated antioxidant response provides effective prophylaxis against cerebral ischemia in vivo. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2005;25(44):10321–35. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4014-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kudoh K, Uchinami H, Yoshioka M, Seki E, Yamamoto Y. Nrf2 activation protects the liver from ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Annals of surgery. 2014;260(1):118–27. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan K, Lu R, Chang JC, Kan YW. NRF2, a member of the NFE2 family of transcription factors, is not essential for murine erythropoiesis, growth, and development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93(24):13943–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schafer M, Farwanah H, Willrodt AH, Huebner AJ, Sandhoff K, Roop D, et al. Nrf2 links epidermal barrier function with antioxidant defense. EMBO molecular medicine. 2012;4(5):364–79. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201200219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kohler UA, Kurinna S, Schwitter D, Marti A, Schafer M, Hellerbrand C, et al. Activated Nrf2 impairs liver regeneration in mice by activation of genes involved in cell-cycle control and apoptosis. Hepatology. 2014;60(2):670–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.26964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee LY, Kohler UA, Zhang L, Roenneburg D, Werner S, Johnson JA, et al. Activation of the Nrf2-ARE pathway in hepatocytes protects against steatosis in nutritionally induced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2014;142(2):361–74. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfu184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suzuki S, Toledo-Pereyra LH, Rodriguez FJ, Cejalvo D. Neutrophil infiltration as an important factor in liver ischemia and reperfusion injury. Modulating effects of FK506 and cyclosporine. Transplantation. 1993;55(6):1265–72. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199306000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen GM. Caspases: the executioners of apoptosis. The Biochemical journal. 1997;326(Pt 1):1–16. doi: 10.1042/bj3260001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang J, Yue S, Ke B, Zhu J, Shen XD, Zhai Y, et al. Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 regulates toll-like receptor 4 innate responses in mouse liver ischemia-reperfusion injury through Akt-forkhead box protein O1 signaling network. Transplantation. 2014;98(7):721–8. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aleksunes LM, Klaassen CD. Coordinated regulation of hepatic phase I and II drug-metabolizing genes and transporters using AhR-, CAR-, PXR-, PPARalpha-, and Nrf2-null mice. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2012;40(7):1366–79. doi: 10.1124/dmd.112.045112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang YK, Yeager RL, Tanaka Y, Klaassen CD. Enhanced expression of Nrf2 in mice attenuates the fatty liver produced by a methionine- and choline-deficient diet. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 2010;245(3):326–34. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ke B, Shen XD, Zhang Y, Ji H, Gao F, Yue S, et al. KEAP1-NRF2 complex in ischemia-induced hepatocellular damage of mouse liver transplants. Journal of hepatology. 2013;59(6):1200–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lemasters JJ. V. Necrapoptosis and the mitochondrial permeability transition: shared pathways to necrosis and apoptosis. The American journal of physiology. 1999;276(1 Pt 1):G1–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.1.G1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaeschke H, Lemasters JJ. Apoptosis versus oncotic necrosis in hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(4):1246–57. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)01209-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gujral JS, Bucci TJ, Farhood A, Jaeschke H. Mechanism of cell death during warm hepatic ischemia-reperfusion in rats: apoptosis or necrosis? Hepatology. 2001;33(2):397–405. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.22002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rudiger HA, Graf R, Clavien PA. Liver ischemia: apoptosis as a central mechanism of injury. J Invest Surg. 2003;16(3):149–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cursio R, Gugenheim J, Ricci JE, Crenesse D, Rostagno P, Maulon L, et al. A caspase inhibitor fully protects rats against lethal normothermic liver ischemia by inhibition of liver apoptosis. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 1999;13(2):253–61. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.