SUMMARY

No method with low morbidity presently exists for obtaining serial hepatic gene expression measurements in humans. While hepatic fine needle aspiration (FNA) has lower morbidity than core needle biopsy, applicability is limited due to blood contamination, which confounds quantification of gene expression changes. The aim of this study was to validate FNA for assessment of hepatic gene expression. Liver needle biopsies and FNA procedures were simultaneously performed on 17 patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection with an additional FNA procedure 1 week later. Nine patients had mild/moderate fibrosis and eight advanced fibrosis. Gene expression profiling was performed using Affymetrix microarrays and TaqMan qPCR; pathway analysis was performed using Ingenuity. We developed a novel strategy that applies liver-enriched normalization genes to determine the percentage of liver in the FNA sample, which enables accurate gene expression measurements overcoming biases derived from blood contamination. We obtained almost identical gene expression results (ρ = 0.99, P < 0.0001) comparing needle biopsy and FNA samples for 21 preselected genes. Gene expression results were also validated in dogs. These data suggest that liver FNA is a reliable method for serial hepatic tissue sampling with potential utility for a variety of preclinical and clinical applications.

Keywords: liver sampling, microarray, nucleic acid analysis, RNA, RNA amplification

INTRODUCTION

The liver is fundamental to a variety of body processes including glucose homoeostasis, cholesterol biosynthesis, drug metabolism, and the production of all major plasma proteins. At the same time, the liver is susceptible to autoimmune, infectious, metabolic and inflammatory conditions. For example, hepatitis C virus (HCV) affects ~120 million people worldwide and nearly five million people in the United States [1,2]. The infection can lead to hepatocellular carcinoma and cirrhosis resulting in liver failure and potentially liver transplantation. In HCV, important issues surrounding viral pathogenesis and determinants of treatment efficacy remain unanswered largely due to difficulty in intrahepatic sampling. While measurements in blood can be a surrogate for intrahepatic events, such as in the case of viral kinetics, in many situations, information directly from the target organ might improve biomarker sensitivity and understanding of treatment or pathologic consequences.

Core needle biopsy (CNB) has conventionally been the gold standard for assessment of hepatic histology. However, CNB is associated with significant shortcomings such as high cost, morbidity and mortality. The most frequent complication of liver biopsy is pain, occurring in 84% of patients, significant haemorrhage in 0–5.3% and mortality in up to 0.5% as reported in the literature [3], although reduced mortality rates would be expected in clinical settings with experienced operators. As liver biopsies are difficult to perform for serial hepatic sampling at short intervals, liver fine needle aspiration (FNA) is likely a safer and less invasive alternative [4]. Its improved safety record, ~0.5% minor complications, 0.05% major complications requiring surgery and <0.01% mortality [4] derives primarily from the much smaller needle used in the procedure (16 vs 25 gauge). FNA has conventionally been used for tissue diagnosis in malignancies from varied organs and in acute rejection in renal and hepatic transplantation [5]. FNA is also extremely accurate for focal liver lesions with specificity approaching 100% and sensitivity ranging from 67% to 100%, averaging ~85% [4]. However, routine fibrosis assessment is much more reliable on CNB than on FNA due to greater sampling error with the FNA technique.

A safe technique [6] with infrequent complications [4], such as liver FNA, may be permissible for serial liver sampling particularly at short intervals. As blood contamination in FNAs can confound quantification of changes in gene expression especially in the liver, its application for clinical investigation requires methods to mitigate these effects. Here, we sought to develop a platform for gene expression profiling using liver samples obtained by FNA. We identified six liver-enriched normalization genes that can reliably determine the percentage of liver in an FNA sample and that increase the sensitivity to detect changes in liver gene expression in fundamental hepatic processes. Finally, we show that these same genes were able to reliably identify the percentage of liver and blood in another mammalian species. These findings validate liver FNA as an accurate, reliable and safe method for frequent, serial assessment of hepatic gene expression that could have wide applicability in understanding physiological changes in the liver related to disease processes or to therapeutic interventions.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study subjects and procedures

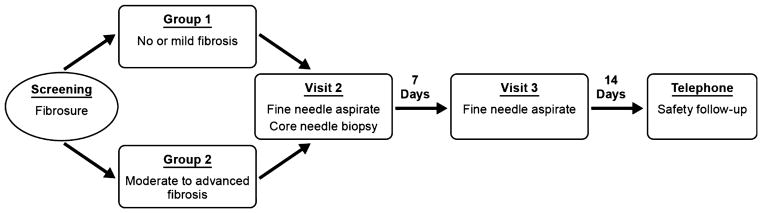

Potentially eligible patients initially underwent a screening visit during which informed consent was obtained and eligibility was assessed (Fig. 1). Potential subjects then returned for a second visit, 7–30 days later, when both FNA and CNB were performed under ultrasound guidance and local anaesthesia. After 7 days, patients returned for a third visit when a second FNA was performed. Pain was assessed on a 0–10 scale after each procedure with the first value representing the combined pain felt with both the liver biopsy and FNA, and the second value indicating pain felt when only the FNA procedure was performed. Fourteen days later, an additional telephone consultation was conducted for safety assessment. Demographic characteristics of the study subjects are illustrated in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Study flow diagram.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Sub no | FibroSure*

|

Sex | Age | Hispanic | Ethnicity | Biopsy

|

HCV RNA | ALT/AST | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | Grade | Stage | Lobular Inflam | Portal Inflam | |||||||

| 1001 | 0.41 | 0.07 | F | 49 | Y | White | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 719 786 | 14/29 |

| 1002 | 0.14 | 0.57 | M | 39 | Y | White | 2 | 2 | 2 | 5 457 293 | 97/51 |

| 1003 | 0.82 | 0.78 | M | 55 | Y | White | 4 | 1 | 1 | 5 455 572 | 90/92 |

| 1006 | 0.64 | 0.3 | F | 46 | N | White | 2 | 2 | 2 | 118 899 | 44/47 |

| 1007 | 0.7 | 0.83 | M | 53 | N | Black | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 902 865 | 133/172 |

| 1008 | 0.5 | 0.26 | M | 51 | N | Black | 2–3 | 1 | 2 | 5 708 610 | ND/40 |

| 1009 | 0.3 | 0.09 | M | 55 | N | Black | 2 | 1–2 | 1–2 | 5 669 440 | 24/22 |

| 1010 | 0.53 | 0.37 | M | 51 | N | Black | 1 | 1 | 1 | 447 250 | 50/35 |

| 1011 | ND | ND | F | 43 | N | Black | 2 | 1 | 2 | 285 631 | 42/42 |

| 1014 | 0.19 | 0.18 | M | 57 | N | Black | 1 | 0 | 1 | 354 752 | 38/26 |

| 1015 | 0.49 | 0.68 | M | 48 | N | Black | 3 | 2 | 2 | 140 936 | 122/152 |

| 1018 | 0.47 | 0.57 | M | 63 | N | Black | 3 | 1 | 3 | 238 912 | 80/70 |

| 1020 | 0.68 | 0.6 | M | 56 | N | Black | 3–4 | 1 | 2 | 6 417 203 | 54/57 |

| 1021 | 0.54 | 0.41 | M | 60 | N | Black | 2 | 2 | 2 | 7 596 697 | 56/63 |

| 1022 | 0.61 | 0.28 | M | 51 | N | Black | 2–3 | 2 | 2 | 87 063 | 32/36 |

| 1026 | 0.28 | 0.46 | M | 47 | Y | White | 2 | 2 | 2 | 692 655 | 75/66 |

| 1027 | 0.57 | 0.61 | M | 53 | Y | White | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 687 484 | 78/48 |

Sub no, subject number; M, male; F, female; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ND, not done.

Fibrosure measurements performed by Labcorp, Research Triangle Park, NC.

For each FNA procedure, four individual samples were collected, and subsequently the CNB was performed. FNA samples and a portion of the CNB were collected in tubes prefilled with RNAlater® (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA), stored at 4 °C for at least 12 h and then placed in −20 °C until processed. The remaining CNB sample, at least 2.5 cm in length, was placed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for histologic assessment by the same pathologist using the Scheuer system [7].

To ensure balanced representation, we initially divided patients based upon FibroSure (LabCorp, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA), into those with no/mild (stage 0–1) or at least moderate fibrosis (stage ≥2). Patients were ineligible if they received any HCV treatment within 6 months of study entry.

Written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to the initiation of the study, and the study conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a priori approval by the Institutional Review Board.

RNA quality

RNA extraction and amplification were performed as described (Supporting information). High quality RNA was defined as RNA integrity number (RIN) > 5 and 28S/18S rRNA ratio between 0.75 and 3.02. The overall yield and RIN for 136 FNA samples were 0.75 μg and 5.6, as compared with an average yield of 1.81 μg and RIN 8.2 for 18 CNBs, respectively.

RNA amplification and RT-qPCR

For each target gene, two candidate TaqMan assays (Applied Biosystems, Inc) were designed using criteria suggested by ABI. After reverse transcription, quantitative PCR was performed with and without pre-amplification (Fig. S1) using the ABI TaqMan® PreAmp Master Mix using an Applied Biosystems Prism 7900HT sequence detection system and expression values were calculated using the comparative Ct method [8].

Identification of liver-enriched normalization genes for qPCR

From an initial list of 560 published gene expression profiles [9–11], we selected a final list of six liver-enriched normalization genes (AMOTL2, KRT8, PPIC, PTPN3, S100A16, and TF) based on absence of variant sequencing transcripts, biological relevance and availability of Taqman assays (see Supporting information and Table S1). TREM1 was selected as a quality-control gene.

Gene expression profiling

Total RNA was amplified using the NuGEN Ovation Whole Blood Solution protocol (NuGEN, Inc., San Carlos, CA, USA) as previously described [12]. Amplified biotin-labelled material was hybridized to a custom-designed Affymetrix array (Gene Expression Omnibus GEO reference GPL10379). Hybridization, washing and scanning were completed as recommended by the manufacturer.

Only samples that met standard RNA quality (28S/18S ratio <0.75) and hybridization quality metrics were analysed. Arrays passed if the percent of detected probe sets was more than 30%.

Microarray and pathway analyses

Microarray data quality was assessed using standard metrics [13] as described in Supporting information.

Confirmation experiments in dog

To collect FNA samples from dog, abdominal skin, muscle, fascia and peritoneal layers were cut and reflected back to provide direct visualization of the liver lobes. FNAs were collected immediately by aspiration with a 1″ 22G needle from the intact liver. FNAs were placed directly into RNAlater® and stored at −20 °C until processing. After FNA collection, liver punches of approximately 1 g were obtained from regions of the liver not affected by FNA collection and stored at −80 °C.

To generate dog liver standard curves, liver punches of various masses (20, 10, 5 and 2.5 mg) were excised from the thawed tissue and homogenized, and 1:2 serial dilutions of homogenate were prepared from the smallest punch to obtain a 12-point standard curve. Prior to sample processing, RNAlater® was decanted from the FNA samples. RNA was isolated from liver punches and FNA samples using Tri-zol Plus RNA purification kit (Invitrogen, #12183-555) and quantified using Quant-it Ribogreen kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad Caverns, CA, USA). cDNA was synthesized using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed using TaqMan gene expression assays from Applied Biosystems according to manufacturer’s directions. Gene expression was stable at different storage and collection temperatures of RNAlater® (data not shown).

For blood addition experiments, FNA samples in RNAlater® were split into two halves and RNAlater® was decanted. 50 μL of dog blood was added to one half of each FNA sample prior to RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis and qPCR analysis as described above.

Statistical analysis

Pearson correlation coefficient was used to assess the similarity of amplified vs nonamplified results for 21 target genes of interest. A random effects model (SAS PROC MIXED), applied to FNA samples whose estimated percent liver content was >30%, was used to assess the impact of normalizing qPCR results for the estimated percentage of liver on the fraction of total variability explained by biological sources (patient-to-patient) relative to technical sources (visit-to-visit and from one FNA insertion to another within the same visit). Differences in gene expression results obtained by qPCR and microarray were also compared using linear regression. The level of significance for all statistical tests was set at α = 0.05.

RESULTS

Demographics and patient characteristics

Seventeen HCV genotype 1 patients with chronic infection undergoing CNB for histologic assessment were enrolled. The average age was 51.6 (range 18–65) years; 14 patients were male, six were Caucasian, 11 were African-American and five were of Hispanic origin (Table 1). Nine patients had fibrosis ≤2 and eight >2. All patients had lobular inflammation of 2 or less, and only two patients had portal inflammation >2. In general, FNAs were well tolerated without any significant adverse effects. The mean patient-rated pain intensity (scale 0–10) on the first (FNA and CNB) and second (FNA) procedures were 1.2 and 2.1, respectively, with 12 of 17 and 8 of 17 subjects reporting no pain on either procedure, respectively.

Quantification of gene expression from FNAs

Initially, we sought to accurately quantify the percentage of liver in the FNA sample through normalization by measurement of liver-enriched genes with the lowest variance (see methods) derived from 560 gene expression experiments from four cohorts. Based upon these analyses, we selected six liver-enriched genes (AMOTL2, KRT8, PPIC, PTPN3, S100A16 and TF) and two quality-control genes (TREM1 and GAPDH). We assumed that the expression level of liver-enriched genes was proportional to the respective liver content of the sample, does not change appreciably across patients and could be used to accurately estimate the respective liver mRNA content of each FNA sample.

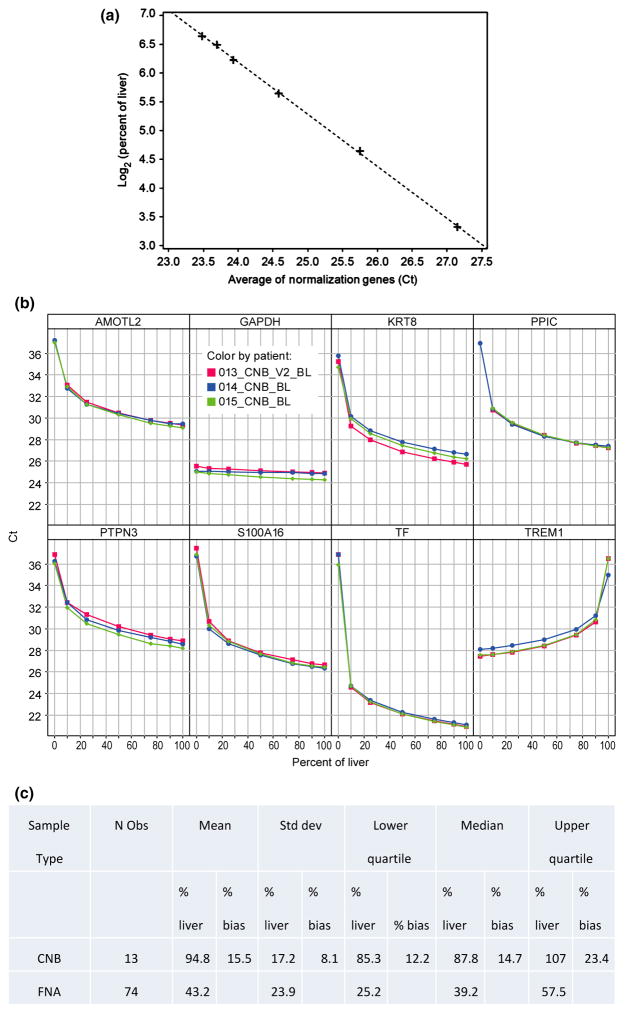

We next assayed expression levels of each of the eight human genes in titrations (Fig. 2a, b) that contained liver-or blood-derived total RNA in various proportions from 0% to 100%. From the standard curves, we estimated that CNB and FNA samples had on average 95% ± 17% and 43% ± 24% liver, respectively. We next computed the bias as the estimated CNB liver content minus 100% and observed a mean 15% bias, which is very typical for analytical assays (Fig. 2c) [14].

Fig. 2.

Methods to estimate percent liver and blood in a sample. (a) Standard curve to calculate percentage of liver. X-axis corresponds to the percent of the six liver-specific genes, AMOTL2, KRT8, PPIC, PTPN3, S100A16 and TF. Y-axis corresponds to the concentration of liver on log2 scale. (b) Titration curves for each transcript for core needle biopsies for three representative patients for liver-enriched genes, AMOTL2, KRT8, PPIC, PTPN3, S100A16 and TF. Also illustrated is the gene, TREM1. Included as a control is the conventional, constitutively expressed gene, GAPDH. X-axis corresponds to the percent of liver in each specimen, and Y-axis corresponds to the threshold cycle for each gene product. Three separate patients are illustrated. (c) Percent of liver and bias estimated in FNA and CNB samples. (d) Representative linear regression analysis to estimate liver gene expression for gene CTNNB1. Y-axis indicates threshold cycle and X-axis indicates percentage of liver on log scale. Black and green lines correspond to the upper and lower 90% confidence intervals for the group mean, respectively. Data points are denoted as crosses. Red line illustrates linear fit. (e) Estimated group means of FNA compared to group means of CNB samples. Abbreviation: Std dev, standard deviation; FNA, fine needle aspirate; CNB, core needle biopsy.

Linear models, including terms for liver content, clinical factors, patient population and their interactions, were used to estimate group mean, error and confidence intervals at 100% liver. For a given transcript, all FNA samples were included in the model (and patient-specific random effects to account for FNAs from the same patient). Ct was regressed on the log (base two) concentration of liver, treatment group and an interaction term allowing for separate Ct vs liver content slopes within each patient population (Fig. 2d). Estimated group means for FNA after accounting for blood contamination were within 0.24 Cts on average to those measured on CNBs with ΔCt, which reflects the accuracy of the estimate (Fig. 2e).

Confirmation of results in another species

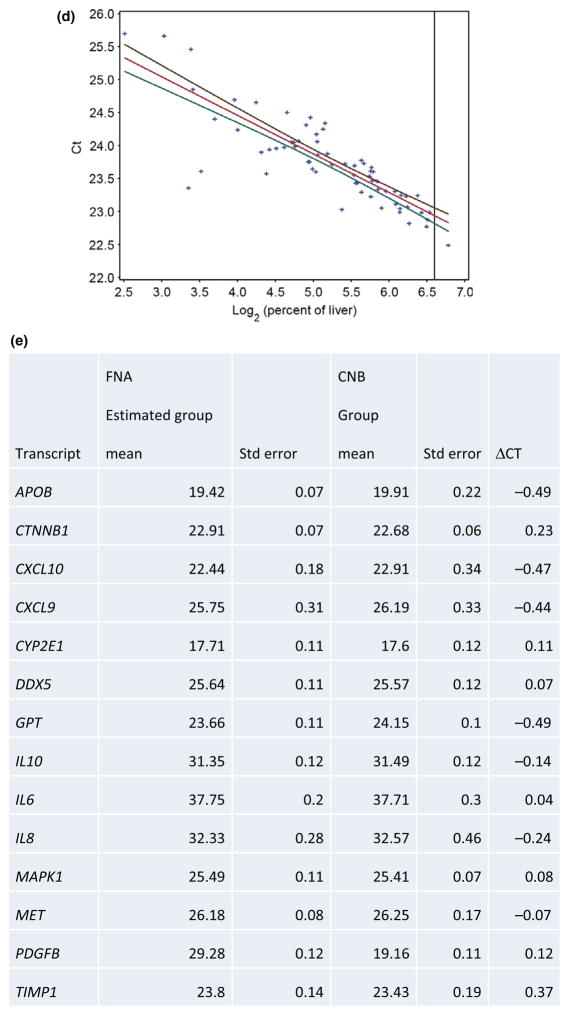

To investigate the cross-species validity of our methods, we conducted liver titration experiments in dog. Standard curves illustrating the amount of liver included vs Ct value for four liver-enriched normalization genes (AMOTL2, KRT8, PTPN3 and TF) confirmed that the expression of the normalization genes is linear with respect to the amount of liver in the sample (Fig. 3a). Using the average Ct value, FNA liver mass was extrapolated from the standard curve to be 0.15–2 mg (Fig. 3b). Liver mass determination was consistent across the individual normalization genes, as observed when FNA liver mass is extrapolated according to the expression and standard curve for each of the four genes (Fig. 3c). The normalization genes S100A16 and PPIC were omitted from the analysis as their expression in dog was more variable than the other liver-enriched genes, resulting in 2–15X higher estimates of liver mass (data not shown). The variability observed for these genes could indicate a species difference. When samples were analysed for the quality-control gene TREM1, the FNA samples had lower TREM1 Ct values relative to the liver punches, indicating higher blood content (Fig. 3d).

Fig. 3.

Quantification of FNA liver mass by assessment of liver normalization genes in dog. Standard curves were generated from liver punches as described in methods and represent the average of two standard curves derived from each of four separate dog experiments. X-axis indicates log-transformed liver tissue mass and Y-axis indicates threshold cycle (Ct). (a) Expression of the liver-enriched normalization genes AMOTL2 (circle), KRT8 (square), PTPN3 (triangle) and TF (inverted triangle) (expressed as Ct value) is linear with respect to liver input in dog liver standard curve. (b) Average expression of the four normalization genes in dog liver standard curve is expressed as average Ct value. (c) FNA liver mass determinations calculated from the standard curves in A. Error bars illustrate the standard error of the mean. (d) Expression of the gene, TREM1, in dog liver standard curve. Gene expression determination of samples obtained by fine needle aspiration (FNA) is shown in red (panels a, b and d). (e) Effect of blood addition on measured liver-enriched gene expression levels as assessed using linear regression analysis of average liver Ct values in FNA samples with (Y-axis) and without (X-axis) blood addition. (f) Liver mass estimation using linear regression analysis in FNA samples with (Y-axis) and without (X-axis) blood addition.

Blood addition experiments were performed to determine the specificity of the liver normalization approach. FNAs were split into two halves, and 50 μL dog blood was added to one half of each FNA sample. Expression of the liver normalization genes was largely resistant to blood addition as indicated by an R2 = 0.75 for comparison of average liver Ct values in FNA samples with and without blood addition (Fig. 3e). Liver mass determination was also consistent between the two halves of each FNA regardless of blood addition (R2 = 0.73, Fig. 3f), suggesting that quantification of liver content is reliable even in the presence of blood contamination. Expression of TREM1, however, was affected by blood addition as indicated by the lack of correlation (R2 = 0.12) observed when TREM1 Ct values are compared in FNA samples with and without blood addition (data not shown).

Identification of sources of variability in human FNA liver sampling

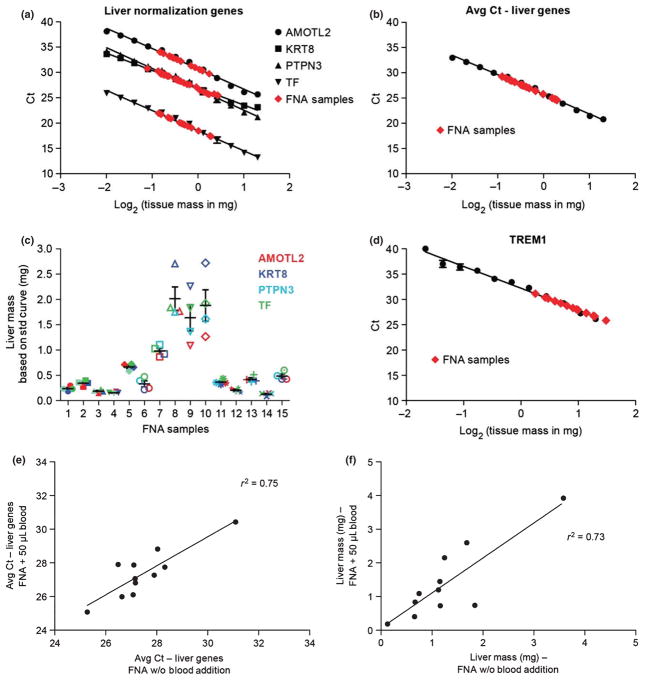

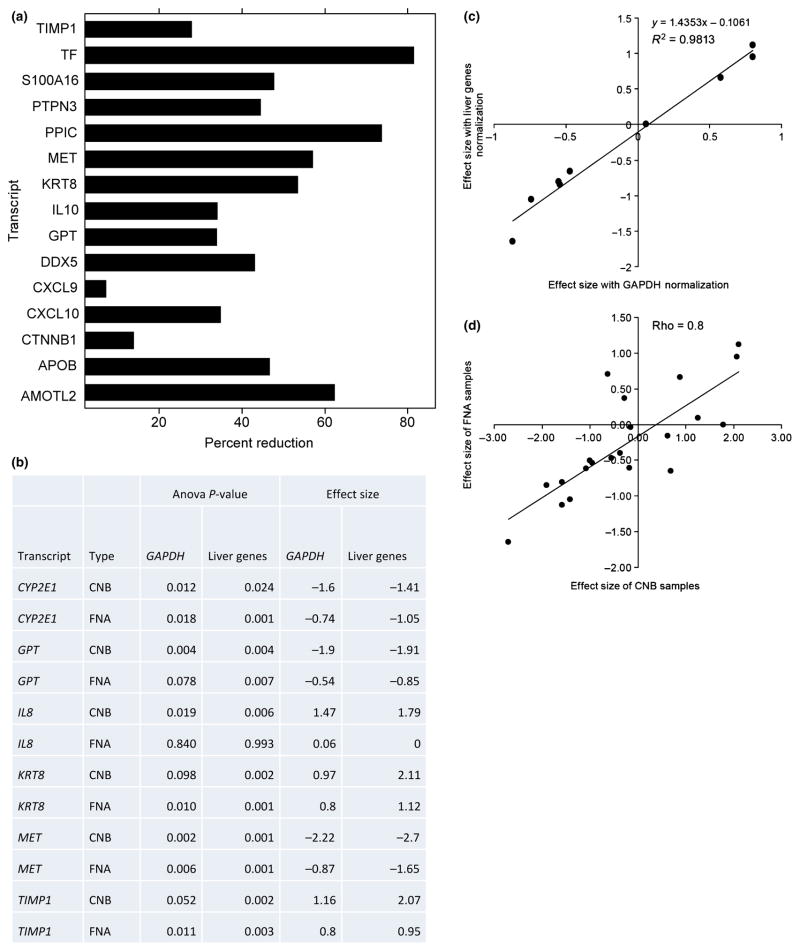

To assess the relative contribution of biological and technical sources of variation in the qPCR normalized Ct values of liver-enriched genes, a variance components analysis with and without an adjustment that normalizes for the liver percentage was performed. Overall, we found that use of the liver percentage adjustment results in substantial reduction in total variability (Fig. 4a). Importantly, without the adjustment for liver percentage, the technical sources of variation (due to unmitigated blood contamination) are the dominant components of total variability overwhelming the biological (patient-to-patient) difference; whereas, after normalizing for the liver percentage in the sample, the overall trend was that biological variation becomes the largest component of variability for liver-enriched genes (Fig. 4b and Table S2). These results underscore the importance of liver normalization with liver-enriched genes.

Fig. 4.

Sources of variability in liver samples obtained by liver fine needle aspiration. (a) Percentage reduction in total variance after adjustment for blood contamination. Total variance is calculated as the sum of the estimates of components of variance due to patient, visit and fine needle aspiration (FNA) procedure. Only genes which showed a positive definite structure for the random effects are shown. (See Supporting information). (b) Significant genes and effect sizes identified on using liver-specific normalization genes compared to normalization using GAPDH on samples obtained by core needle biopsy (CNB) and FNA. Significant differences are defined at P-value<0.01 to compensate for multiple testing. (c) Scatter plot and linear regression analysis of effect sizes for the differences between mild and severe fibrosis from FNA samples. Y-axis corresponds to effect sizes calculated using liver-specific genes. X-axis corresponds to normalization using GAPDH. Each data point corresponds to a gene from the list (CTNNB1, CXCL10, CYP2E1, GPT, IL8, KRT8, MET, PDGFB and TIMP1). Linear regression and R2 are illustrated. (d) Scatter plot of effect sizes for the differences between mild and severe fibrosis from FNA and CNB samples. Y-axis corresponds to effect sizes in FNA. X-axis corresponds to CNB samples. Each data point corresponds to a gene from the list (AMOTL2, APOB, CTNNB1, CXCL10, CXCL9, CYP2E1, DDX5, GPT, IL10, IL6, IL8, KRT8, MAPK1, MET, PDGFB, PPIC, PTPN3, S100A16, TF, TIMP1 and TREM1). Pearson correlation coefficient is illustrated.

Application to gene expression

Using CNB samples, which have conventionally been used for gene expression analysis, we found that of the 21 genes of interest, only GPT and MET were significantly different (P-value <0.01) between mild/moderate and severe fibrosis normalized to GAPDH (Fig. 4c). Subsequently, we evaluated whether the use of organ-specific normalization genes would identify more differentially-regulated genes in comparison to normalization by GAPDH. TIMP1, one of the most important fibrosis-related genes, was not significantly different after normalization with GAPDH. However, it was significantly changed after normalization with liver-specific genes. Additionally we found that KRT8 and IL8 were significantly increased while two genes (GPT, MET) were decreased in patients with severe fibrosis after normalization with liver-enriched genes. Thus, normalization by liver-enriched genes improved the ability to identify genes important to liver pathogenesis in comparison with GAPDH.

Cohen’s effect size is the measure of magnitude of the relationship between two groups, that is, between those with mild and severe fibrosis. We found strong correlation (R2 = 0.98) between effect sizes calculated after normalization with GAPDH vs normalization with all six liver-enriched genes (Fig. 4c). Additionally, it shows that effect sizes are larger by 1.4-fold in samples normalized with liver genes. This is a direct result of reducing the variance due to blood by normalizing liver content in FNA samples. Figure 4d shows strong (ρ = 0.8) correlation between effect sizes from FNA and CNB samples normalized with liver-enriched genes. This is additional evidence that samples obtained by FNA can enhance the sensitivity of biomarker discovery in liver in comparison with peripheral blood samples.

Differential expression in high and low fibrosis as assessed by FNA and CNB

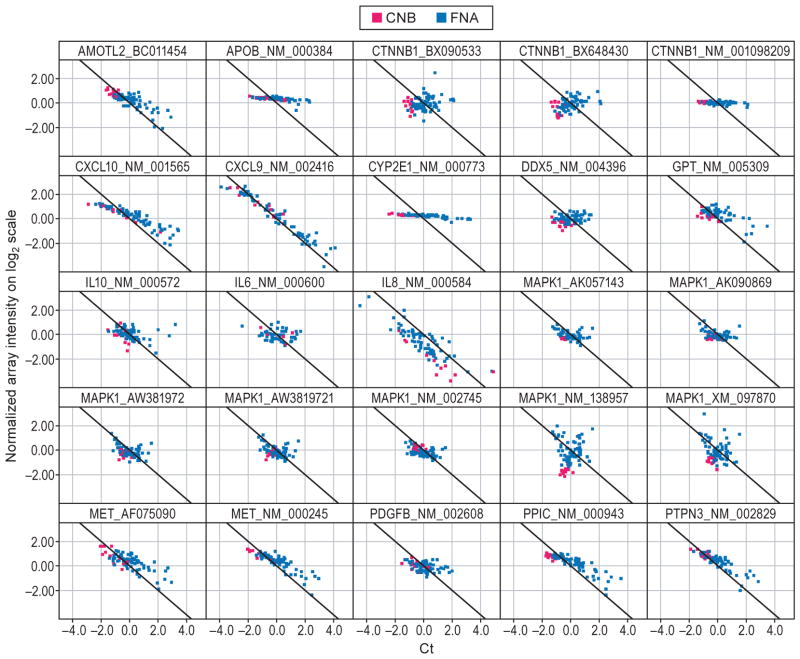

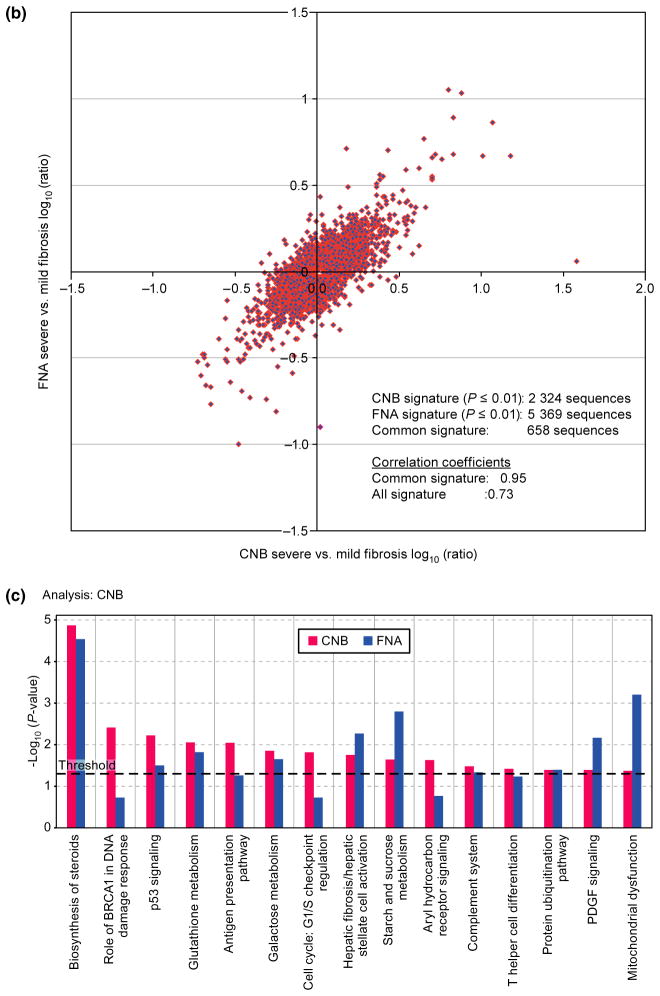

We next sought to extend techniques for quantification of blood contamination in FNA to the results of DNA microarray assays in comparison to those obtained through RT-qPCR using TaqMan assays (Fig. 5a). The results of linear regression analysis performed to estimate the similarity of microarray and TaqMan gene expression measurements for the 21 genes of interest are illustrated in Table S3. Seven genes had good correlation (R2>0.7) between the results of the two platforms (CXCL9, CXCL10, MET, PPIC, PTPN3, S100A16 and TREM). Subsequently, we assessed the relationship between genes identified on microarray and the level of fibrosis using three different measures of the stage of fibrosis: (i) as assessed by the study-specific pathologist by review of the liver biopsy, (ii) as assessed using the noninvasive measure of fibrosis, Fibrosure®, both as a continuous variable and (iii) as a dichotomous variable. Liver CNB and FNA profiling by microarray was performed on 16 patients, eight with mild/moderate (Scheuer stage 1–2) and eight with severe fibrosis (stage 3–4).

Fig. 5.

Agreement in gene expression in samples obtained by core needle biopsy and fine needle aspiration. (a) Scatter plot of mean normalized log2 transformed intensity values vs standardized TaqMan assay Cts. Black line corresponds to ideal relationship between microarray and TaqMan assay data. Negative correlation is due to reverse scale of TaqMan assay, the higher the Cts the lower the transcript expression levels. Red and blue colours correspond to core needle biopsy (CNB) and fine needle aspiration (FNA), respectively. (b) Correlation analysis between CNB and FNA signatures. Analysis was performed by combining severe fibrosis samples and referenced to the mild fibrosis gene expression pool of its own sample type (i.e. CNB or FNA). Correlation of fibrosis signature genes between CNB and FNA samples is 0.73, P ≤ 0.01. (c) The canonical pathways most associated with severe fibrosis signatures from CNB (red) and FNA (blue) samples based on the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA). Y-axis depicts log-transformed P-value.

We found a high degree of correlation for fibrosis signature genes between CNB and FNA (rho~0.73, P = 0.01) (Fig. 5b) after removing 18 (of 96) FNA samples in which blood consisted of more than 30% of the sample. A common severe vs mild/moderate fibrosis gene signature of 2441 sequences (corresponding to 1862 genes) was identified between CNB and FNA samples by using a 2-way ANOVA approach. Ingenuity pathway analysis indicated that genes differentially expressed in patients with severe vs mild fibrosis include those that belong in pathways involved with cholesterol biosynthesis, cell-cycle regulation, glutathione metabolism, hepatic fibrosis and inflammation-related responses such as antigen presentation pathways, complement system and T-helper cell differentiation (Fig. 5c). It also resembled previously reported signatures of cirrhotic liver [15].

DISCUSSION

Intrahepatic investigation requires a balance between the potential of gaining insights into disease processes directly from the target organ with that of risk to the patient due to an invasive procedure. While mathematical models of peripheral HCV RNA decline may be used to infer what occurs in the liver [16,17], their validation has been limited by the difficulty of performing serial liver biopsies due to the potential to cause infection, bleeding, organ injury and even death. Thus, minimally invasive procedures and reliable assays that require small input quantities could provide important insights. In this work, we sought to validate liver FNA, a procedure that has been utilized previously to assess immunological aspects of HCV [18,19] and to monitor for signs of liver transplant rejection [5,20], as a method for assessment of changes in intrahepatic gene expression.

Here, we demonstrate that we have successfully overcome the major limitations of the use of the FNA procedure, low nucleic acid quantity and blood contamination, for gene expression profiling. Through nucleic acid pre-amplification and normalization with liver-enriched genes, we were able to differentiate the fraction of the transcript that originated from liver. We have shown that RNA obtained by both FNA and CNB has sufficient quality for gene expression analysis by microarray and Taqman leading to highly correlated results. By calculating the percentage of liver in the sample and discarding samples that contain more than 30% blood, we were able to effectively mitigate blood contamination as a source of variability in liver FNA samples and to achieve accurate quantification of transcript levels. In addition, the normalization procedure resulted in an increased sensitivity to detect intrahepatic expression levels of genes important to liver pathogenesis. Normalization by organ-specific genes may prove particularly important in resource-intensive studies that rely on invasive sampling, which by their nature are limited to relatively small sample sizes in comparison to those based upon peripheral blood sampling. The use of organ-specific normalization genes may also increase the power to detect differences between groups, thereby potentially decreasing the required sample size. Furthermore, the strategy of normalizing by liver-enriched genes was also effective in determining the respective contribution to the sample in a mammalian model system (dog) thus affording platform translation to preclinical species. As a clinical application, we found that gene signatures from either CNB or FNA samples were highly correlated and differentiated those with mild/moderate vs severe hepatic fibrosis very effectively.

By molecular profiling of samples from patients with severe compared to those with mild/moderate fibrosis, we identified genes that are consistent with previously identified pathways of hepatic fibrogenesis. For example, we identified 673 genes in common between the current severe fibrosis gene signature and a previously reported liver cirrhosis signature of 5569 genes (overlapping P-value = 6.5 × 10−95) [15]. The gene signature that we identified had significant overlap with liver dysplasia [15], HBV-infected liver with cirrhosis [21] and hepatocellular carcinoma. In addition to pathways previously shown to be related to fibrosis such as cell-cycle regulation, glutathione metabolism, antigen presentation, platelet-derived growth factor signalling and protein ubiquitination [22], we identified signature genes associated with cholesterol biosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism pathways, both of which have recently been shown to be associated with the severity of liver fibrosis [23,24]. Thus, our results validate liver FNA for assessment of hepatic gene expression serially with results comparable to those observed in CNB samples.

In summary, we have demonstrated that hepatic sampling via FNA is suitable for studies of gene expression by qPCR. We have also demonstrated that the liver-enriched normalization genes we identified are also valid to other mammalian species. The application of these techniques to other organs with normalization by genes specific for that organ may improve biomarker development by increasing specificity and power. Potential further uses of the FNA procedure may include measurement of intrahepatic drug concentration for modelling and for selection of the optimal drug dose as well as assessment of changes in intrahepatic gene expression levels under antiviral therapy. With additional investigation, liver FNA may become a standard procedure for intrahepatic assessment of disease processes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the assistance of Dr. Rhonda Yantiss, Jessy Makeyeva, Ginevra Castagna, Gertrudis Soto, Beatrice Mesidor, Melissa Drexel, Christine Cervini, David Stone, Mark Ferguson, Robert Iannone and Zinaida Sergueeva. We thank Phil Kezele and Miho Kibukawa for technical assistance with this study, Larry Handt and Ken Lodge for providing preclinical dog samples, and John Hinchcliffe for the design and production of the custom-designed vacuum filtration device. This study was partially funded by Merck and Co. and partially by the Clinical and Translational Science Center (ULI RR024996) at Weill Cornell Medical College.

Abbreviations

- CNB

core needle biopsy

- FNA

fine needle aspiration

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- RIN

RNA Integrity Number

Footnotes

AUTHOR’S DECLARATION OF PERSONAL INTERESTS

Dr. Talal has served as a consultant to and has received research support from Merck and Company. Dr. Zeremski has received research support from Merck and Company. Drs. Lejnine, Lunceford, Ruddy, Sun, Marton, Wang, Malkov, Howell, Webber, Maxwell and Shire are employees of Merck and Company.

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Table S1: Genes and probes evaluated as part of the analysis.

Table S2: Variance components estimates with and without adjustment for percent liver.

Table S3: Linear regression analysis comparing Taqman and microarray probesets for 21 genes.

Figure S1: Representative example of linear regression analysis between ΔCt of preamplified (Y-axis) and nonamplified (X-axis) of MAPK1 as assessed by reverse transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) across 89 samples.

References

- 1.Shepard CW, Finelli L, Alter MJ. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:558–567. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chak E, Talal AH, Sherman KE, Schiff ER, Saab S. Hepatitis C virus infection in USA: an estimate of true prevalence. Liver Int. 2011;31:1090–1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rockey DC, Caldwell SH, Goodman ZD, Nelson RC, Smith AD. Liver biopsy. Hepatology. 2009;49:1017–1044. doi: 10.1002/hep.22742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buscarini L, Fornari F, Bolondi L, et al. Ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy of focal liver lesions: techniques, diagnostic accuracy and complications. A retrospective study on 2091 biopsies. J Hepatol. 1990;11:344–348. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(90)90219-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwekkeboom J, Zondervan PE, Kuijpers MA, Tilanus HW, Metselaar HJ. Fine-needle aspiration cytology in the diagnosis of acute rejection after liver transplantation. Br J Surg. 2003;90:246–247. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chhieng DC. Fine needle aspiration biopsy of liver - an update. World J Surg Oncol. 2004;2:5. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scheuer PJ. Classification of chronic viral hepatitis: a need for reassessment. J Hepatol. 1991;13:372–374. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(91)90084-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System: User Bulletin #2. Foster City, CA: Applied Biosystems; 1997. Updated 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schadt EE, Molony C, Chudin E, et al. Mapping the genetic architecture of gene expression in human liver. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hao K, Luk JM, Lee NP, et al. Predicting prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma after curative surgery with common clinicopathologic parameters. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:389. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhong H, Beaulaurier J, Lum PY, et al. Liver and adipose expression associated SNPs are enriched for association to type 2 diabetes. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000932. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parrish ML, Wright C, Rivers Y, et al. cDNA targets improve whole blood gene expression profiling and enhance detection of pharmocodynamic biomarkers: a quantitative platform analysis. J Transl Med. 2010;8:87. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-8-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krotzky AJ, Zeeh B. Immunoassays for residue analysis of agrochemicals: proposed guidelines for precision, standardization and quality control. Pure Appl Chem. 2005;67:2065–2088. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wurmbach E, Chen YB, Khitrov G, et al. Genome-wide molecular profiles of HCV-induced dysplasia and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2007;45:938–947. doi: 10.1002/hep.21622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neumann AU, Lam NP, Dahari H, et al. Hepatitis C viral dynamics in vivo and the antiviral efficacy of interferon-α therapy. Science. 1998;282:103–107. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5386.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Talal AH, Ribeiro RM, Powers KA, et al. Pharmacodynamics of PEGIFN alpha differentiate HIV/HCV co-infected sustained virological responders from nonresponders. Hepatology. 2006;43:943–953. doi: 10.1002/hep.21136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sprengers D, van der Molen RG, Kusters JG, et al. Flow cytometry of fine-needle-aspiration biopsies: a new method to monitor the intrahepatic immunological environment in chronic viral hepatitis. J Viral Hepat. 2005;12:507–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vrolijk JM, Tang TJ, Kwekkeboom J, et al. Monitoring intrahepatic CD8+ T cells by fine-needle aspiration cytology in chronic hepatitis C infection. J Viral Hepat. 2004;11:342–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2004.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuijf ML, Kwekkeboom J, Kuijpers MA, et al. Granzyme expression in fine-needle aspirates from liver allografts is increased during acute rejection. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:952–956. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2002.34970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jia HL, Ye QH, Qin LX, et al. Gene expression profiling reveals potential biomarkers of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1133–1139. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hernandez-Gea V, Friedman SL. Pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:425–456. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwartz Y, Dushkin MI, Komarova NI, Vorontsova EV, Kuznetsova IS. Cholesterol-induced stimulation of postinflammatory liver fibrosis. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2008;145:692–695. doi: 10.1007/s10517-008-0175-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abdelmalek MF, Suzuki A, Guy C, et al. Increased fructose consumption is associated with fibrosis severity in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51:1961–1971. doi: 10.1002/hep.23535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.