Abstract

Epidemiological data suggest women are at increased risk for developing anxiety and depression, although the mechanisms for this sex/gender difference remain incompletely understood. Pre-clinical studies have begun to investigate sex-dependent emotional learning and behavior in rodents, particularly as it relates to psychopathology; however, information about how gonadal hormones interact with the central nervous system is limited. We observe greater anxiety-like behavior in male mice with global knockout of the cannabinoid 1 receptor (Cnr1) compared to male, wild-type controls as measured by percent open arm entries on an elevated plus maze test. A similar increase in anxiety-like behavior, however, is not observed when comparing female Cnr1 knockouts to female wild-type subjects. Although, ovariectomy in female mice did not reverse this effect, both male and female adult mice with normative development were sensitive to Cnr1 antagonist-mediated increases in anxiety-like behavior. Together, these data support an interaction between sex, potentially mediated by gonadal hormones, and the endocannabinoid system at an early stage of development that is critical for establishing adult anxiety-like behavior.

Keywords: Cannabinoid 1 receptor, anxiety, estrogen, development, sex, gender

Introduction

Human epidemiological data consistently suggest that women are at increased risk for major depression and anxiety disorders [1]. Pre-clinical behavioral neuroscience studies, however, have historically modeled emotional behavior and psychiatric disease in exclusively male samples. Given the epidemiological data and the largely exclusive focus on male animal models, it is imperative to include a sex-dependent component of analysis in animal models of psychopathology. Comprehensive sex-based analysis will allow researchers to determine how gonadal hormones, which generally circulate at different levels in men and women, interact with central transmitter systems and neural circuits, particularly those that underlie emotion and psychopathology. These types of analyses may clarify the greater prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders among women.

In the pursuit of identifying factors that differentially confer risk or resilience to psychopathology according to sex/gender, investigation of the endogenous cannabinoid system may offer clarity. Across species, the cannabinoid system appears to be critical for emotion and psychopathology [2, 3]. Moreover, the cannabinoid system also seems to be regulated differently in men and women. Sex/gender-differences are observed related to cannabis use, where women appear to more susceptible to dependence [4]. The cannabinoids are also reported to exert sex/gender-specific effects with respect to stress, emotion, and psychopathology, although investigation in this area is still minimal and the direction of these sex/gender-specific effects is not always consistent [3]. These sex/gender-dependent differences may stem from a bidirectional interaction between the cannabinoid system and the estrogen system [5].

We hypothesize that constitutive global knockout of Cnr1 may have a differential sex-dependent effect on anxiety-like behavior in mice on an elevated plus maze. The elevated plus maze is a valid test of anxiety-like behavior in rodents and has been used to screen pharmacotherapies for affective disorders [6]. In male subjects, global knockout or antagonism of Cnr1 increases anxiety-like behavior on a number of different paradigms [2]. Here, we demonstrate divergent anxiety-like behaviors of male and female Cnr1 transgenic mice on an elevated-plus maze test.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult male and free-cycling female (estrous cycle was not monitored) C57BL/6J and Cnr1 transgenic mice were group housed in a temperature-controlled (24° C) animal colony, with ad libitum access to food and water, on a 12 hour light-dark cycle. Cnr1 transgenic mice (C57BL/6J background) were a generous gift from Dr. Carl Lupica at NIDA [7]. Experimental subjects were genotyped by PCR using primers “CB1F” (wild-type forward: 5’ GTA CCA TCA CCA CAG ACC TCC T), “CB1wt” (wild-type reverse: 5’ GGA TTC AGA ATC ATG AAG CAC TC) and “CNK03” (mutant reverse: 5’ AAG AAC GAG ATC AGC AGC CTC T). Wild-type and Cnr1 knockout amplicons are ~300 base pairs and ~150 base pairs, respectively. Homozygous constitutive Cnr1 knockout and wild-type littermates from in house heterozygous breeding pairs were weaned at 3 weeks of age and tested at 8-12 weeks of age. All behavioral procedures were performed during the light cycle.

Surgery

Ovariectomy or sham surgeries were performed on 8-week old female Cnr1 transgenic mice. Anesthesia was induced and maintained using isoflurane. For the ovariectomies, ovaries were gently pulled out and removed via cauterization and subsequent severing of the fallopian tubes. Sham surgeries were conducted identical to ovariectomy with the exception of ovary removal. Behavioral testing commenced two weeks after surgery.

Behavior

Elevated plus maze

Subjects were handled once per day for the two days prior to testing. Subjects were placed in the center of an elevated plus maze apparatus to explore for 5 minutes in dim lighting (25 lux, measured from the perspective of the subject in the center of the elevated plus maze). The EPM consists of two open arms (50 × 6.5 cm2) and two closed arms with a wall (50 × 6.5 × 15 cm3) attached to a common central platform (6.5 × 6.5 cm2) to form a cross. The maze was elevated 65 cm above the floor. Behavior was videotaped and hand-scored offline for time on open arms, time on closed arms, open arm entries, and closed arm entries. Observer was not blinded to subject genotype, sex, or drug group assignment. Mice were considered to be on the open or closed arm when all four feet entered an arm. Percent open arm entries (percent open arm entries = (open arm entries/(open arm entries + closed arm entries))*100) was used as a measure of anxiety-like behavior. Separate cohorts were used for each behavioral experiment. All subjects tested were included in the analyses, as no subjects fell off the elevated plus maze.

Drugs

The Cnr1 antagonist, SR141716A (Cayman Chemical 9000484), was dissolved in a vehicle of 2.5% DMSO/0.1% Tween-80 in saline and administered at a dose of 3 mg/kg. SR141716A was administered intraperitoneally (IP) 20 minutes prior to testing on an elevated plus maze.

Statistics

Two-way ANOVA was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 21 software. The results are presented as mean + SEM. A post hoc Bonferroni correction was used where appropriate.

Results

Female Cnr1 knockout subjects do not exhibit increased anxiety-like behavior compared to male Cnr1 knockout littermates

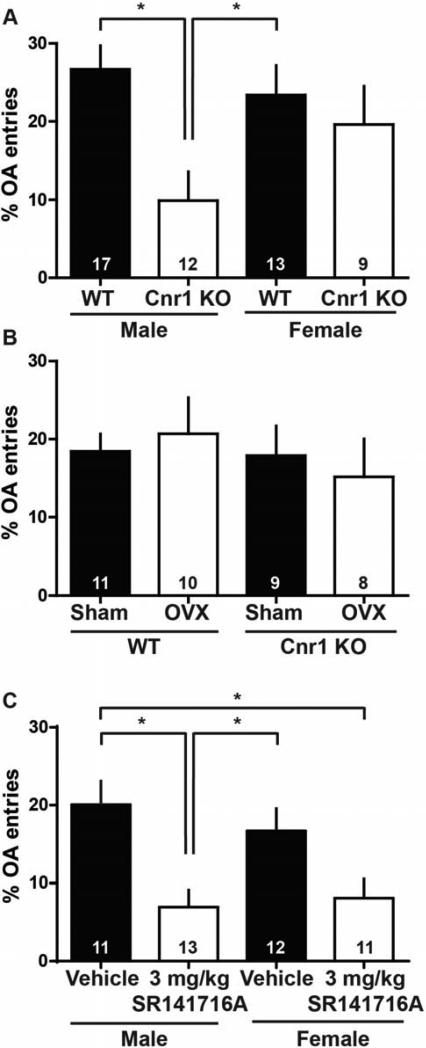

Wild-type and Cnr1 knockout male and female littermates were tested on an elevated plus maze and assessed for 1) time spent on open arms, 2) time spent on closed arms, 3) open arm entries, and 4) closed arm entries (N, wild-type males = 17, Cnr1 knockout males = 12, wild-type females = 13, Cnr1 knockout females = 9). We detected a significant main effect of genotype on percent open arm entries (F1,47=9.32, p<0.01, Fig. 1A). We also found a significant genotype by sex interaction in our analysis of percent open arm entries (F1,47=4.35, p<0.05). We did not observe a main effect of sex. Post hoc Bonferroni tests revealed a significant difference between male wild-type versus male Cnr1 knockouts (p<0.01) and female wild-type subjects versus male Cnr1 knockouts (p<0.05) on percent open arm entries. We did not detect a significant difference between female wild-type versus female Cnr1 knockout littermates. These data suggest that male Cnr1 knockout subjects exhibit increased anxiety-like behavior compared to male wild-type subjects, whereas female Cnr1 knockout subjects exhibit similar levels of anxiety-like behavior compared to female and male wild-type subjects.

Fig. 1. Anxiety-like behavior in cannabinoid receptor 1 (Cnr1) knockout mice is sex-dependent.

(A) We observe a significant genotype by sex interaction in our analysis of percent open arm entries (p<0.05). Post hoc tests reveal a significant difference between male wild-type versus male Cnr1 knockouts (p<0.01) and female wild-type subjects versus male Cnr1 knockouts (p<0.05). We do not detect a significant difference between female wild-type versus female Cnr1 knockout littermates. (B) Ovariectomy does not increase anxiety-like behavior in Cnr1 knockout females. We do not detect a significant main effect of surgery or sex, nor do we observe a surgery by sex interaction on percent open arm entries. (C) We observe a significant main effect of 3 mg/kg SR141716A on percent open arm entries (p<0.01). Post hoc tests reveal a significant difference between males administered vehicle versus males administered SR141716A (p<0.01), males administered SR141716A versus females administered vehicle (p<0.05), and males administered vehicle versus females administered SR141716A (p<0.05). We observe a trend when comparing females administered vehicle versus females administered SR141716A (p<0.1).

In analyzing the raw values, we detected the same main effect of genotype (F1,47=5.10, p<0.05) and a genotype x sex interaction on open arm entries (F1,47=4.53, p<0.05). We did not detect a main effect of sex or genotype, or a genotype x sex interaction on closed arm time, closed arm entries, or open arm time (data not shown). Furthermore, we did not detect a main effect of genotype or sex, or a genotype x sex interaction on total number of entries (closed arm entries + open arm entries), suggesting that all subjects exhibited comparable motor behavior (data not shown).

Ovariectomy does not increase anxiety-like behavior in Cnr1 knockout females

To test the hypothesis that ovarian hormones mediate a protective effect against increased anxiety-like behavior caused by Cnr1 knockout, we performed ovariectomy (OVX) and sham surgeries on 8-week old wild-type and Cnr1 knockout females (N, wild-type sham females = 11, Cnr1 knockout sham females = 9, wild-type OVX females = 10, Cnr1 knockout females = 8). Two weeks after surgery, subjects were assessed for anxiety-like behavior, as in the prior experiment (Fig. 1B). We did not detect a significant main effect of surgery or genotype, nor did we observe a surgery by genotype interaction on percent open arm entries. Similarly, we did not detect a significant main effect of surgery or genotype, nor did we observe a surgery x genotype interaction on open arm entries, closed arm time, closed arm entries, open arm time, or total entries (data not shown). These data replicate our previous finding - global knockout of Cnr1 does not increase anxiety-like behavior in female mice as in male mice. Interestingly, ovariectomy does not increase anxiety-like behavior in female Cnr1 knockout subjects, suggesting that gonadal hormones might interact with the cannabinoid system early in development to differentially mediate anxiety-like behavior in males and females.

A Cnr1 antagonist, SR141716A, increases anxiety-like behavior in male and female C57BL/6J mice

Next, we administered the Cnr1 antagonist SR141716A at a dose of 3 mg/kg to male and female adult C57BL/6J mice to further examine whether the previously observed interaction between sex and Cnr1 knockout is developmentally-mediated (N, vehicle males = 11, SR141716A males = 13, vehicle females = 12, SR141716A females = 11). We observed a significant main effect of drug on percent open arm entries (F1,43=7.43, p<0.01, Fig. 1C). We did not detect a significant main effect of sex or a drug by sex interaction on percent open arm entries. Post hoc Bonferroni tests revealed a significant difference between males administered vehicle versus males administered SR141716A (p<0.01), males administered SR141716A versus females administered vehicle (p<0.05), and males administered vehicle versus females administered SR141716A (p<0.05). We observed a trend when comparing females administered vehicle versus females administered SR141716A (p<0.1).

We also observed a significant main effect of drug on open arm entries (F1,43=11.49, p<0.01), closed arm time (F1,43=16.49, p<0.001), closed arm entries (F1,43=5.62, p<0.05), and open arm time (F1,43=5.14, p<0.05). We did not detect a significant drug x sex interaction on any measure of anxiety-like behavior (data not shown). Furthermore, we did not detect a main effect of drug or sex, or a drug x sex interaction on total number of entries.

Discussion

These data demonstrate an interaction between sex and the endocannabinoid system in anxiety-like behavior, where: 1) adult female Cnr1 knockout subjects do not exhibit increased anxiety-like behavior as in adult male Cnr1 knockout littermates; 2) ovariectomy in adult females does not increase anxiety-like behavior in Cnr1 knockouts; however, 3) the Cnr1 antagonist, SR141716A, increases anxiety-like behavior in both male and female wild-type C57BL/6J mice.

Our results are supported by prior literature. Global knockout of Cnr1 or administration of a Cnr1 antagonist increases anxiety-like behavior in male rodents [2]. However, other data demonstrate differential effects of the cananbinoids on anxiety-like behavior, which could be dependent on a balance between GABAergic and glutamatergic neurotransmission or, alternatively, promiscuous activation of receptors beyond Cnr1 [8, 9]. Furthermore, an effect of the cannabinoids on anxiety-like behavior appears to be contingent on the aversiveness of the test situation [10]. Thus, our observation of a genotype and drug, and, further, genotype x sex interaction effect on anxiety-like behavior may be specific to our experimental conditions.

We did not observe a main effect of sex on anxiety-like behavior in any of our experiments, consistent with some data, but in contrast to other reports [11, 12]. To our knowledge, no study has assessed differences in anxiety-like behavior between male and female Cnr1 knockout mice, however, one study fails to observe a difference in anxiety-like behavior between male and female mice with conditional knockout of Cnr1 in either GABAergic or glutamatergic neuronal populations [9]. Furthermore, no study has assessed whether Cnr1 antagonists have an effect on anxiety-like behavior in female Cnr1 knockout mice as in male Cnr1 knockout mice [8].

As acute administration of a Cnr1 antagonist increases anxiety-like behavior similar to Cnr1 knockout mice, it is presumed that an anxiogenic effect of Cnr1 knockout is not developmentally mediated [2]. Our data demonstrating that female Cnr1 knockout mice exhibit normative anxiety-like behavior, which was not altered by ovariectomy, compared to increased anxiety-like behavior in Cnr1 antagonist administered C57BL/6J females suggests that there is a developmental component to an effect of Cnr1 knockout on anxiety-like behavior. This is underlined by data which do not observe a difference in anxiety-like behavior between male and female mice with conditional knockout of Cnr1 in either GABAergic or glutamatergic neuronal populations, as Cnr1 could be present during a critical period of development in these strains [9]. Our data indicate that some factor present during early development in females - potentially during the prenatal through the early postnatal developmental critical period - may detect and compensate for aberrant Cnr1 signaling that contributes to increased anxiety-like behavior in adult males. Alternatively, males, perhaps due to an interaction between Cnr1 knockout and an early development surge in testosterone, may be more vulnerable to development of the observed anxiety-like phenotype. Male rat pups have higher levels of anandamide and 2-AG, the two major endogenous cannabinoids, potentially stemming from lower levels of observed endocannabinoid degradative enzymes [13]. Furthermore, the cannabinoid system is differentially dysregulated in male and female rats in response to early maternal deprivation, supporting the hypothesis that sex-specific organization of the cannabinoid system early in development impacts later adolescent and adult sex-specific behaviors [13-15]. Regardless, an exact interpretation of a developmental mechanism by which gonadal hormones interact with the cannabinoid system to mediate differential anxiety phenotypes in male and female mice is limited by the scope of this study and the relative dearth of investigation in this area. Future experiments should investigate the effect of gonadal hormones during early development, which are critical for sexual differentiation, in order to determine the exact nature and timing of a Cnr1/gonadal hormone interaction in anxiety-like behavior. The adult male brain phenotype results from exposure of the late gestational/early neonatal brain to estradiol, which is synthesized from testicular testosterone [16]. In this vein, future studies could examine an effect of neonatal testosterone or estradiol injection in female Cnr1 knockout mice to determine whether early testosterone administration causes an increase in anxiety-like behavior as in male Cnr1 knockout mice. Moreover, there is evidence that the pubertal surge in hormones, aside from a surge early in development, can also differentially organize the male and female brain [17]. As we performed ovariectomy on 8-week old, adult females, we are not able to exclude the possibility that a pubertal surge in hormones contributed to sex differences in anxiety-like behavior in our subjects.

Comparatively more is known regarding an interaction between the cannabinoid system, behavior, sex/gender, and the gonadal hormones during adulthood relative to early development. Sex/gender-differences are observed related to cannabis use and dependence [4]. Chronic stress differentially affects plasticity of the cannabinoid system in the hippocampus according to sex [18]. The cannabinoid system also appears to modulate prefrontal dendritic complexity and cognitive flexibility disparately in males and females [19]. In rats, an anxiolytic effect of estradiol may be mediated by fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH), an endocannabinoid degradative enzyme [20].

Several clinical studies observe interactions between the cannabinoid system, sex/gender, and mental health. Males with a specific Cnr1 SNP haplotype (rs806377) are at greater risk for ADHD compared to females with the same haplotype [21]. The same SNP is associated with PTSD; however, a sex/gender x SNP x PTSD diagnosis interaction is not reported [21]. Intriguingly, in vivo PET data demonstrate sex/gender differences in Cnr1 receptor regulation, in particular an upregulation of Cnr1 in women, and especially in women with PTSD [3]. In a study of Major Depression, the CNR1 rs1049353 G allele is reported to confer resistance to antidepressant treatment, particularly in women [22].

While both the clinical and pre-clinical data suggest interplay between the cannabinoid system and sex that is critical to emotional behavior and psychopathology, the direction of this interaction is not always consistent. Furthermore, our data suggest that females are more resilient with regard to anxiety-like behavior, which is counterintuitive given that the epidemiological data indicates increased prevalence of affective disorders among women [1, 23]. Looking forward, it will be important to address divergence between animal model data and epidemiological data. Transgenic mice, in particular the four core genotypes (FCG) mice, may be instrumental in this vein, as they can allow assessment of the contribution of sex chromosomes, developmental hormone exposure, and adult circulating hormones to differences in behavior according to sex [24].

Several caveats of our study should be acknowledged. While we did not measure gonadal hormone levels in our female subjects, the ovariectomy data suggest that some sex-specific factor interacts with a Cnr1 deficiency during early neural development, limiting the information that adult hormone level monitoring might lend to the conclusions of this study. However, data suggest that proestrous (when estradiol levels are higher), compared to diestrous, mice and rats spend more time on the open arms of the EPM [25, 26]. Estrous cycle monitoring may be particularly critical in the future, additionally, as Cnr1 binding appears to fluctuate according to phase of the estrous cycle [27]. Additional tests of anxiety-like behavior (e.g. open field test, elevated plus maze under aversive light conditions) should be conducted to expand on the findings reported here, particularly as anxiety-like behavior of Cnr1 knockout mice may depend on the aversiveness of the test situation [28]. Data from these studies suggest that we may observe an alternative outcome when measuring anxiety-like phenotypes of male and female Cnr1 transgenic mice in more aversive contexts. Additionally, while recent evidence indicates that the EPM appropriately assays anxiety-like behavior in male mice, the EPM may provide a measure of general activity in females [29, 30]. This complicates interpretation of the present study, however, as noted – we did not observe a main effect of sex on total entries made by subjects on the EPM. Future studies that use an anxiety task less dependent on general locomotion, such as the Vogel punished drinking task, could clarify these issues.

Altogether, our data suggests the cannabinoid system may regulate anxiety-like behavior in a sex-dependent manner, potentially via changes to the brain early in development. Pre-clinical and clinical studies should continue to address a potential interaction between the cannabinoid system, sex/gender, and emotion, as identifying an interaction might be explanatory regarding sex/gender differences related to affective disorders.

Table 1.

Non-significant elevated plus maze data from wild-type and Cnr1 knockout male and female mice

| Group | Open Arm Time | Percent Open Arm Time | Closed Arm Time | Closed Arm Entries | Total Entries | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | |

| WT/Male | 25.71 | 6.17 | 8.29 | 1.99 | 198.47 | 9.70 | 10.41 | 1.04 | 14.18 | 1.24 |

| KO/Male | 24.58 | 13.68 | 7.93 | 4.41 | 234.42 | 10.64 | 8.42 | 1.32 | 9.58 | 1.56 |

| WT/Female | 36.16 | 16.88 | 11.66 | 5.44 | 212.46 | 15.17 | 9.15 | 1.04 | 12.23 | 1.35 |

| KO/Female | 33.44 | 10.71 | 10.79 | 3.46 | 217.89 | 15.73 | 9.33 | 1.96 | 12.33 | 2.51 |

Table 2.

Non-significant elevated plus maze data from wild-type and Cnr1 knockout, sham and ovariectomized female mice

| Group | Open Arm Time | Percent Open Arm Time | Open Arm Entries | Percent Open Arm Entries | Closed Arm Time | Closed Arm Entries | Total Entries | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | |

| WT/Sham | 12.86 | 3.30 | 5.41 | 1.47 | 2.82 | 0.42 | 18.43 | 2.24 | 235.82 | 8.21 | 12.45 | 1.19 | 15.27 | 1.36 |

| WT/OVX | 27.60 | 10.85 | 10.86 | 4.40 | 3.70 | 1.08 | 20.69 | 4.62 | 232.90 | 12.85 | 12.10 | 0.38 | 15.80 | 1.18 |

| KO/Sham | 34.33 | 10.08 | 12.81 | 3.64 | 3.56 | 0.77 | 17.88 | 3.81 | 229.89 | 9.72 | 15.11 | 1.15 | 18.67 | 1.44 |

| KO/OVX | 25.38 | 12.89 | 9.72 | 4.92 | 3.13 | 1.33 | 15.17 | 4.88 | 233.50 | 13.15 | 11.63 | 1.92 | 14.75 | 3.04 |

Table 3.

Non-significant elevated plus maze data from vehicle and 3 mg/kg SR141716A-administered male and female mice

| Group | Total Entries | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | SEM | |

| Vehicle/Male | 17.73 | 0.78 |

| SR141716A/Male | 16.85 | 0.73 |

| Vehicle/Female | 17.92 | 1.04 |

| SR141716A/Female | 18.45 | 0.89 |

Highlights.

We compare anxiety-like behavior of male and female Cnr1 transgenic mice.

Male Cnr1 KOs make less percent open arm entries on an elevated plus maze compared to male WTs.

Female WTs and female Cnr1 KOs do not significantly differ on percent open arm entries.

Ovariectomy does not affect percent open arm entries.

Cnr1 antagonist administration decreases percent open arm entries in both sexes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Carl Lupica for the generous donation of the Cnr1 transgenic mouse line. We thank Dr. Brian Dias for assistance in learning how to perform ovariectomy surgery. Support was provided by NIH (T32-GM08605, 1F31MH097397, and R01MH096764), the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, and by an NIH/NCRR base grant (P51RR000165) to Yerkes National Primate Research Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gavranidou M, Rosner R. The weaker sex? Gender and post-traumatic stress disorder. Depression and anxiety. 2003;17:130–9. doi: 10.1002/da.10103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruehle S, Rey AA, Remmers F, Lutz B. The endocannabinoid system in anxiety, fear memory and habituation. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26:23–39. doi: 10.1177/0269881111408958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neumeister A, Seidel J, Ragen BJ, Pietrzak RH. Translational evidence for a role of endocannabinoids in the etiology and treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;51:577–84. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Craft RM, Marusich JA, Wiley JL. Sex differences in cannabinoid pharmacology: a reflection of differences in the endocannabinoid system? Life sciences. 2013;92:476–81. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorzalka BB, Dang SS. Minireview: Endocannabinoids and gonadal hormones: bidirectional interactions in physiology and behavior. Endocrinology. 2012;153:1016–24. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walf AA, Frye CA. The use of the elevated plus maze as an assay of anxiety-related behavior in rodents. Nature protocols. 2007;2:322–8. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimmer A, Zimmer AM, Hohmann AG, Herkenham M, Bonner TI. Increased mortality, hypoactivity, and hypoalgesia in cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:5780–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haller J, Bakos N, Szirmay M, Ledent C, Freund TF. The effects of genetic and pharmacological blockade of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor on anxiety. The European journal of neuroscience. 2002;16:1395–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rey AA, Purrio M, Viveros MP, Lutz B. Biphasic effects of cannabinoids in anxiety responses: CB1 and GABA(B) receptors in the balance of GABAergic and glutamatergic neurotransmission. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:2624–34. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haller J, Varga B, Ledent C, Barna I, Freund TF. Context-dependent effects of CB1 cannabinoid gene disruption on anxiety-like and social behaviour in mice. The European journal of neuroscience. 2004;19:1906–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Voikar V, Koks S, Vasar E, Rauvala H. Strain and gender differences in the behavior of mouse lines commonly used in transgenic studies. Physiology & behavior. 2001;72:271–81. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00405-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.An XL, Zou JX, Wu RY, Yang Y, Tai FD, Zeng SY, et al. Strain and sex differences in anxiety-like and social behaviors in C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice. Experimental animals / Japanese Association for Laboratory Animal Science. 2011;60:111–23. doi: 10.1538/expanim.60.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krebs-Kraft DL, Hill MN, Hillard CJ, McCarthy MM. Sex difference in cell proliferation in developing rat amygdala mediated by endocannabinoids has implications for social behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:20535–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005003107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Llorente R, Arranz L, Marco EM, Moreno E, Puerto M, Guaza C, et al. Early maternal deprivation and neonatal single administration with a cannabinoid agonist induce long-term sex-dependent psychoimmunoendocrine effects in adolescent rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:636–50. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suarez J, Llorente R, Romero-Zerbo SY, Mateos B, Bermudez-Silva FJ, de Fonseca FR, et al. Early maternal deprivation induces gender-dependent changes on the expression of hippocampal CB(1) and CB(2) cannabinoid receptors of neonatal rats. Hippocampus. 2009;19:623–32. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCarthy MM. Estradiol and the developing brain. Physiological reviews. 2008;88:91–124. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00010.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulz KM, Molenda-Figueira HA, Sisk CL. Back to the future: The organizational-activational hypothesis adapted to puberty and adolescence. Hormones and behavior. 2009;55:597–604. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reich CG, Taylor ME, McCarthy MM. Differential effects of chronic unpredictable stress on hippocampal CB1 receptors in male and female rats. Behavioural brain research. 2009;203:264–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee TT, Filipski SB, Hill MN, McEwen BS. Morphological and behavioral evidence for impaired prefrontal cortical function in female CB1 receptor deficient mice. Behavioural brain research. 2014;271:106–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.05.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill MN, Karacabeyli ES, Gorzalka BB. Estrogen recruits the endocannabinoid system to modulate emotionality. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:350–7. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu AT, Ogdie MN, Jarvelin MR, Moilanen IK, Loo SK, McCracken JT, et al. Association of the cannabinoid receptor gene (CNR1) with ADHD and post-traumatic stress disorder. American journal of medical genetics Part B, Neuropsychiatric genetics : the official publication of the International Society of Psychiatric Genetics. 2008;147B:1488–94. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Domschke K, Dannlowski U, Ohrmann P, Lawford B, Bauer J, Kugel H, et al. Cannabinoid receptor 1 (CNR1) gene: impact on antidepressant treatment response and emotion processing in major depression. European neuropsychopharmacology : the journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;18:751–9. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen H, Yehuda R. Gender differences in animal models of posttraumatic stress disorder. Disease markers. 2011;30:141–50. doi: 10.3233/DMA-2011-0778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seney ML, Chang LC, Oh H, Wang X, Tseng GC, Lewis DA, et al. The Role of Genetic Sex in Affect Regulation and Expression of GABA-Related Genes Across Species. Frontiers in psychiatry. 2013;4:104. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walf AA, Koonce C, Manley K, Frye CA. Proestrous compared to diestrous wildtype, but not estrogen receptor beta knockout, mice have better performance in the spontaneous alternation and object recognition tasks and reduced anxiety-like behavior in the elevated plus and mirror maze. Behavioural brain research. 2009;196:254–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walf AA, Frye CA. A review and update of mechanisms of estrogen in the hippocampus and amygdala for anxiety and depression behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1097–111. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodriguez de Fonseca F, Cebeira M, Ramos JA, Martin M, Fernandez-Ruiz JJ. Cannabinoid receptors in rat brain areas: sexual differences, fluctuations during estrous cycle and changes after gonadectomy and sex steroid replacement. Life sciences. 1994;54:159–70. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)00585-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacob W, Yassouridis A, Marsicano G, Monory K, Lutz B, Wotjak CT. Endocannabinoids render exploratory behaviour largely independent of the test aversiveness: role of glutamatergic transmission. Genes, brain, and behavior. 2009;8:685–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shansky RM. Sex differences in PTSD resilience and susceptibility: Challenges for animal models of fear learning. Neurobiology of stress. 2015;1:60–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kokras N, Dalla C. Sex differences in animal models of psychiatric disorders. British journal of pharmacology. 2014;171:4595–619. doi: 10.1111/bph.12710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]