Abstract

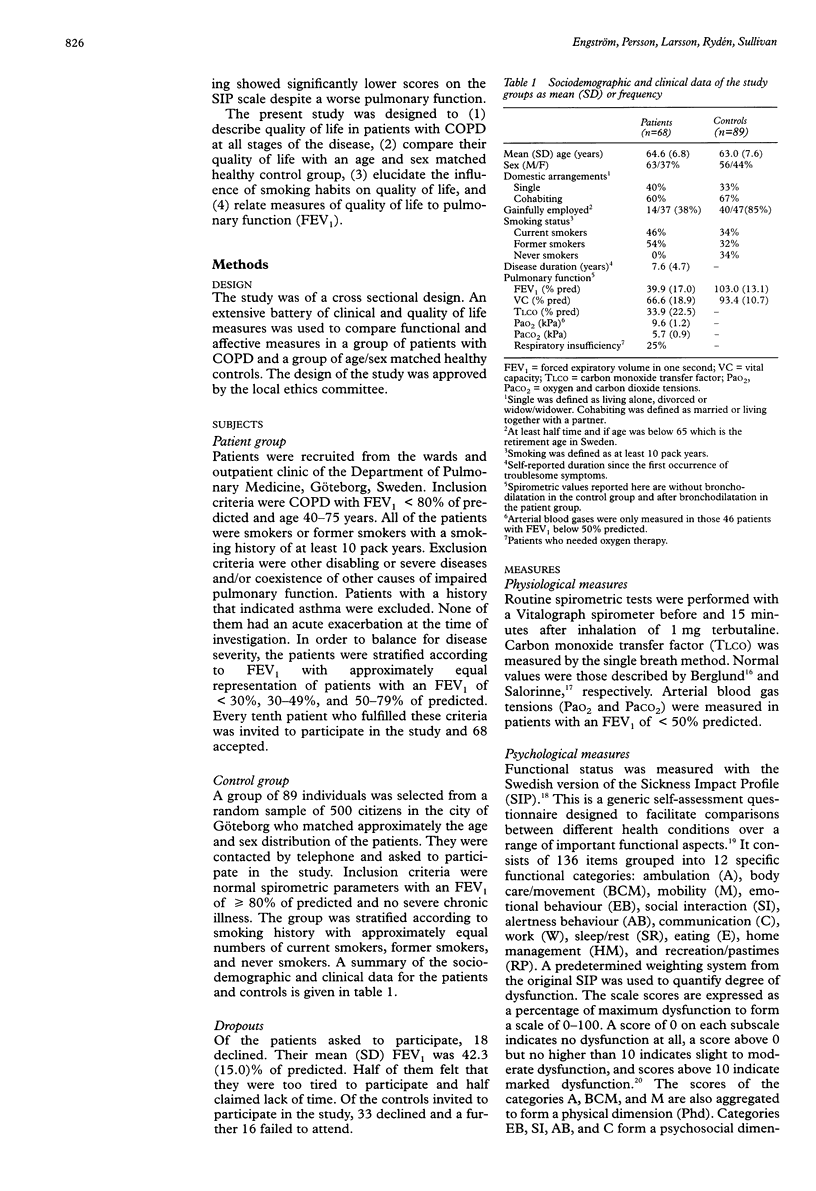

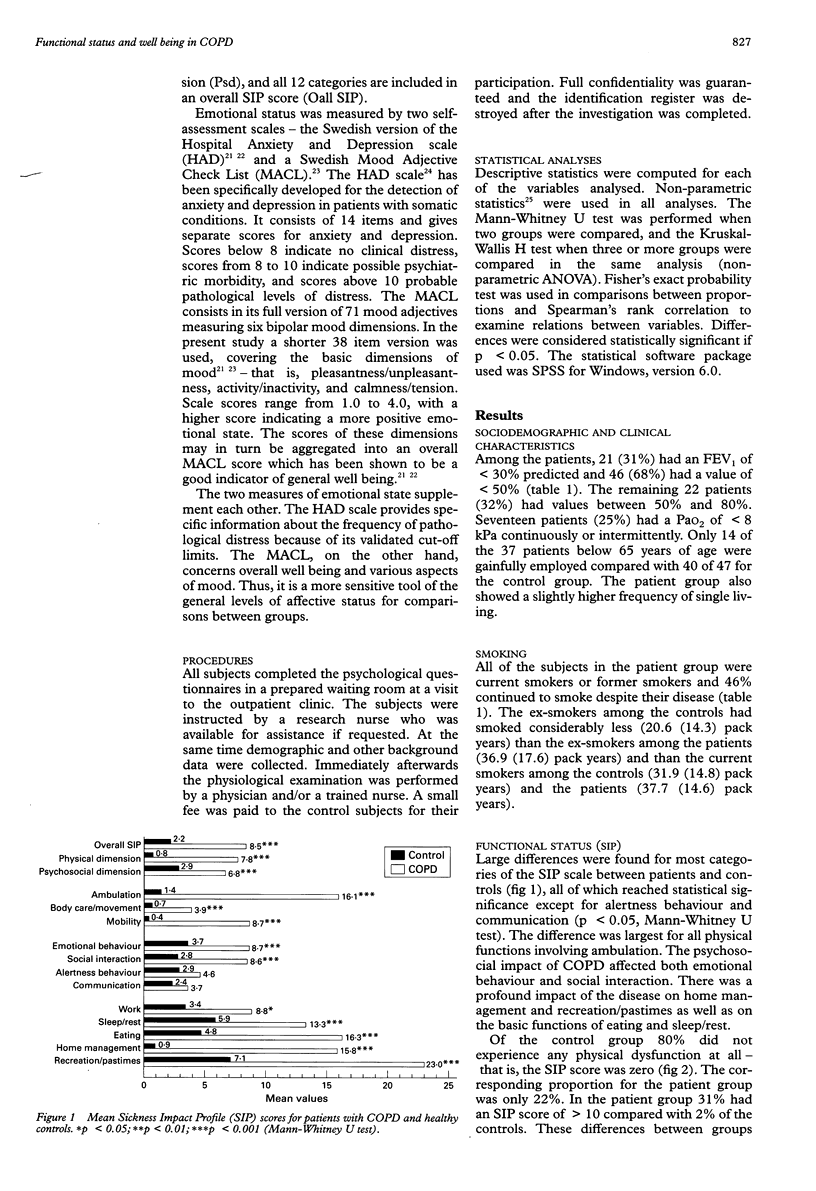

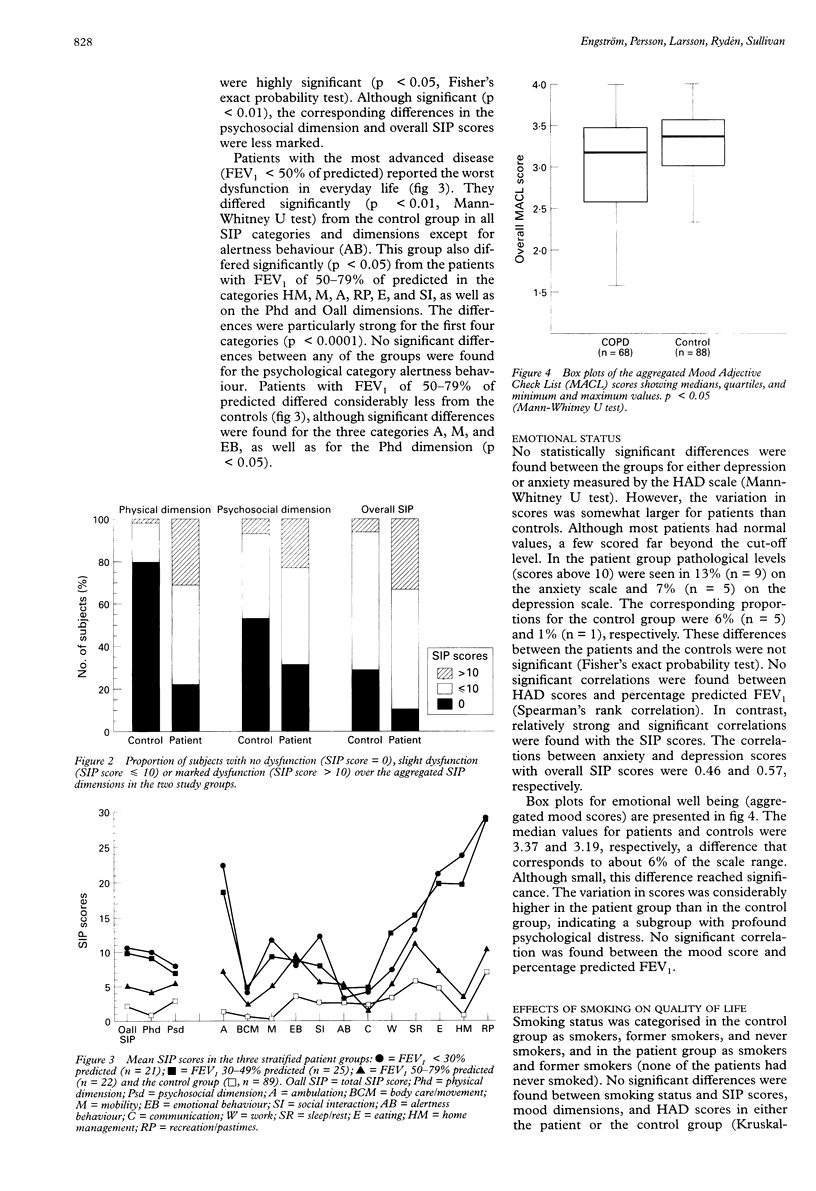

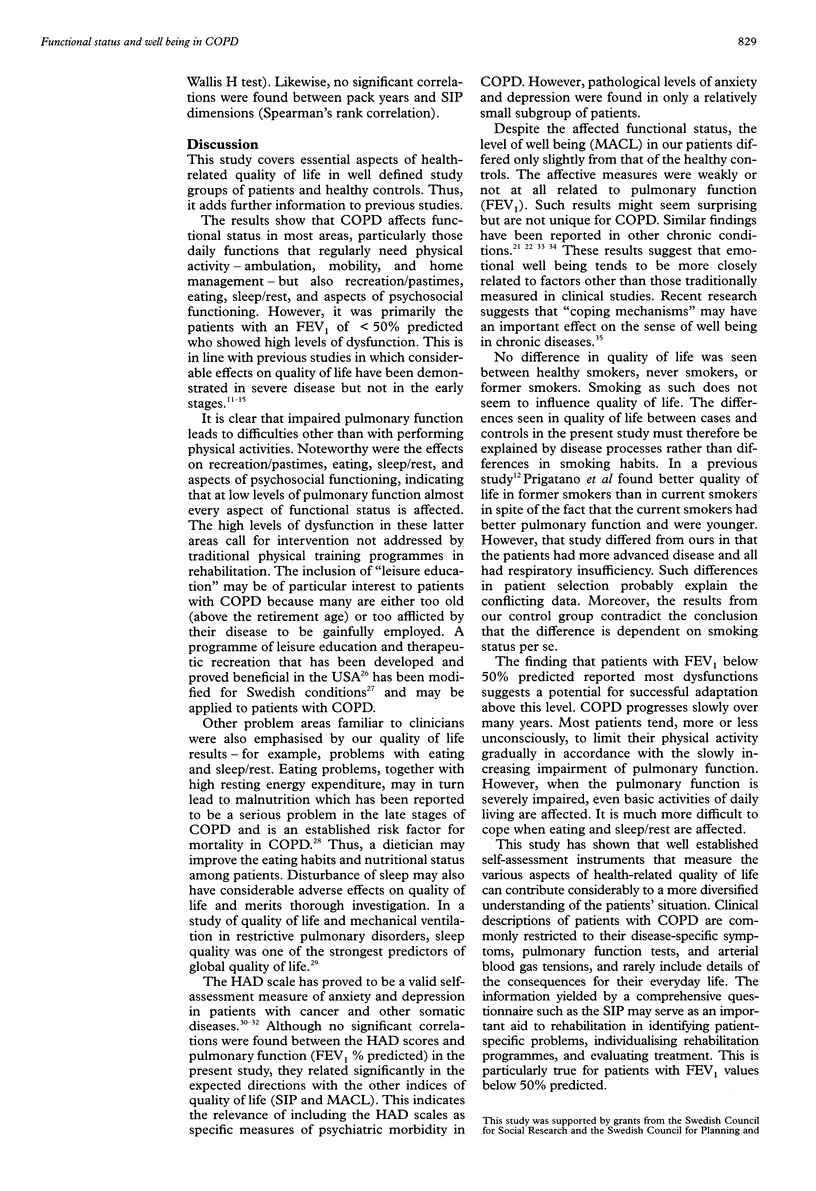

BACKGROUND: Self-assessment questionnaires which measure the functional and affective consequences of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) give valuable information about the effects of the disease and may serve as important tools with which to evaluate treatment. METHODS: A cross sectional comparative study was performed between patients with COPD (n = 68), stratified according to pulmonary function, and a healthy control group (n = 89). A battery of well established clinical and quality of life measures (the Sickness Impact Profile (SIP), Mood Adjective Check List (MACL), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale (HAD)) was used to examine in which functional and affective aspects the patient group differed from the control group and how these measures related to pulmonary function and smoking habits. RESULTS: Compared with the controls, COPD affected functional status in most areas, not just those requiring physical activity. Forty six patients with forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) below 50% predicted showed particularly high levels of dysfunction in ambulation, eating, home management, and recreation/ pastimes (SIP). Despite this, their level of psychosocial functioning and mood status was little different from that of the healthy controls. Among the patients, a subgroup reported substantial psychological distress, but mood status was only weakly, or not at all, related to pulmonary function. Smoking habits did not affect functional status or well being. CONCLUSIONS: Quality of life is not significantly affected in patients with mild to moderate loss of pulmonary function, possibly due to coping and/or pulmonary reserve capacity. This suggests that generic self-assessment questionnaires are of limited value for detecting the early consequences of COPD. However, in later stages of the disease they are sensitive enough to discriminate between patients with different levels of pulmonary dysfunction. The low correlations between the indices of pulmonary function and the indices of affective status suggest that well being depends, to a large extent, on factors outside the clinical domain.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ahlmén E. M., Bengtsson C. B., Sullivan B. M., Bjelle A. A comparison of overall health between patients with rheumatoid arthritis and a population with and without rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 1990;19(6):413–421. doi: 10.3109/03009749009097630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson R. T., Aaronson N. K., Wilkin D. Critical review of the international assessments of health-related quality of life. Qual Life Res. 1993 Dec;2(6):369–395. doi: 10.1007/BF00422215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aylard P. R., Gooding J. H., McKenna P. J., Snaith R. P. A validation study of three anxiety and depression self-assessment scales. J Psychosom Res. 1987;31(2):261–268. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(87)90083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERGLUND E., BIRATH G., BJURE J., GRIMBY G., KJELLMER I., SANDQVIST L., SODERHOLM B. Spirometric studies in normal subjects. I. Forced expirograms in subjects between 7 and 70 years of age. Acta Med Scand. 1963 Feb;173:185–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergner M., Bobbitt R. A., Carter W. B., Gilson B. S. The Sickness Impact Profile: development and final revision of a health status measure. Med Care. 1981 Aug;19(8):787–805. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198108000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis J. R., Deyo R. A., Hudson L. D. Pulmonary rehabilitation in chronic respiratory insufficiency. 7. Health-related quality of life among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1994 Feb;49(2):162–170. doi: 10.1136/thx.49.2.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman A. P. Pulmonary rehabilitation research. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994 Mar;149(3 Pt 1):825–833. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.8118655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood P., Howell A., Maguire P. Screening for psychiatric morbidity in patients with advanced breast cancer: validation of two self-report questionnaires. Br J Cancer. 1991 Aug;64(2):353–356. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1991.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood P., Howell A., Maguire P. Screening for psychiatric morbidity in patients with advanced breast cancer: validation of two self-report questionnaires. Br J Cancer. 1991 Aug;64(2):353–356. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1991.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P. W., Baveystock C. M., Littlejohns P. Relationships between general health measured with the sickness impact profile and respiratory symptoms, physiological measures, and mood in patients with chronic airflow limitation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989 Dec;140(6):1538–1543. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.6.1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaptein A. A., Brand P. L., Dekker F. W., Kerstjens H. A., Postma D. S., Sluiter H. J. Quality-of-life in a long-term multicentre trial in chronic nonspecific lung disease: assessment at baseline. The Dutch CNSLD Study Group. Eur Respir J. 1993 Nov;6(10):1479–1484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R. S. Coping theory and research: past, present, and future. Psychosom Med. 1993 May-Jun;55(3):234–247. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199305000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundqvist C., Siösteen A., Blomstrand C., Lind B., Sullivan M. Spinal cord injuries. Clinical, functional, and emotional status. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1991 Jan;16(1):78–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahler D. A., Faryniarz K., Tomlinson D., Colice G. L., Robins A. G., Olmstead E. M., O'Connor G. T. Impact of dyspnea and physiologic function on general health status in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chest. 1992 Aug;102(2):395–401. doi: 10.1378/chest.102.2.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahler D. A., Harver A. A factor analysis of dyspnea ratings, respiratory muscle strength, and lung function in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992 Feb;145(2 Pt 1):467–470. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.2_Pt_1.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McSweeny A. J., Grant I., Heaton R. K., Adams K. M., Timms R. M. Life quality of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 1982 Mar;142(3):473–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pehrsson K., Olofson J., Larsson S., Sullivan M. Quality of life of patients treated by home mechanical ventilation due to restrictive ventilatory disorders. Respir Med. 1994 Jan;88(1):21–26. doi: 10.1016/0954-6111(94)90169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigatano G. P., Wright E. C., Levin D. Quality of life and its predictors in patients with mild hypoxemia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 1984 Aug;144(8):1613–1619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjöberg L., Svensson E., Persson L. O. The measurement of mood. Scand J Psychol. 1979;20(1):1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.1979.tb00677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan M., Ahlmén M., Archenholtz B., Svensson G. Measuring health in rheumatic disorders by means of a Swedish version of the sickness impact profile. Results from a population study. Scand J Rheumatol. 1986;15(2):193–200. doi: 10.3109/03009748609102088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan M., Ahlmén M., Bjelle A. Health status assessment in rheumatoid arthritis. I. Further work on the validity of the sickness impact profile. J Rheumatol. 1990 Apr;17(4):439–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan M., Karlsson J., Sjöström L., Backman L., Bengtsson C., Bouchard C., Dahlgren S., Jonsson E., Larsson B., Lindstedt S. Swedish obese subjects (SOS)--an intervention study of obesity. Baseline evaluation of health and psychosocial functioning in the first 1743 subjects examined. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1993 Sep;17(9):503–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J. E., Jr Standards for validating health measures: definition and content. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(6):473–480. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegner R. E., Jörres R. A., Kirsten D. K., Magnussen H. Factor analysis of exercise capacity, dyspnoea ratings and lung function in patients with severe COPD. Eur Respir J. 1994 Apr;7(4):725–729. doi: 10.1183/09031936.94.07040725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S. J., Bury M. R. Impairment, disability and handicap in chronic respiratory illness. Soc Sci Med. 1989;29(5):609–616. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(89)90180-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D. O., Rogers R. M., Wright E. C., Anthonisen N. R. Body weight in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The National Institutes of Health Intermittent Positive-Pressure Breathing Trial. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989 Jun;139(6):1435–1438. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/139.6.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond A. S., Snaith R. P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983 Jun;67(6):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]