Abstract

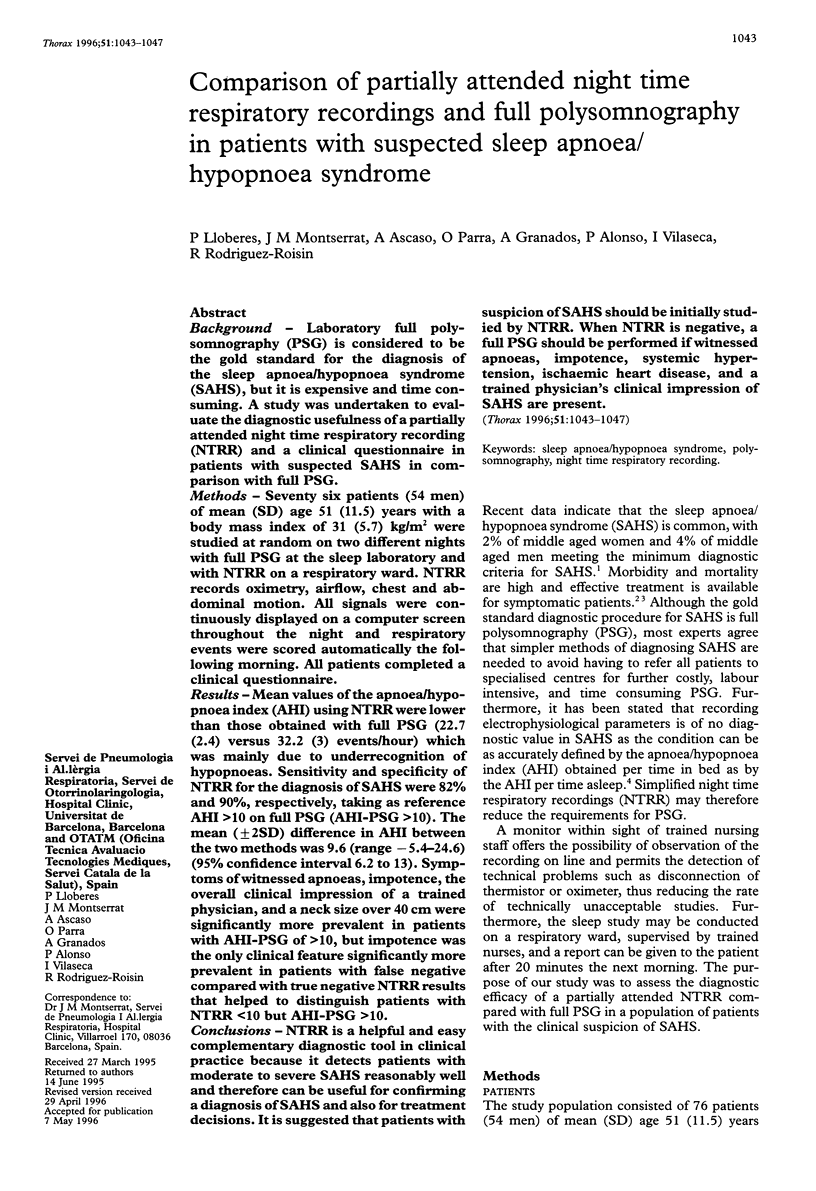

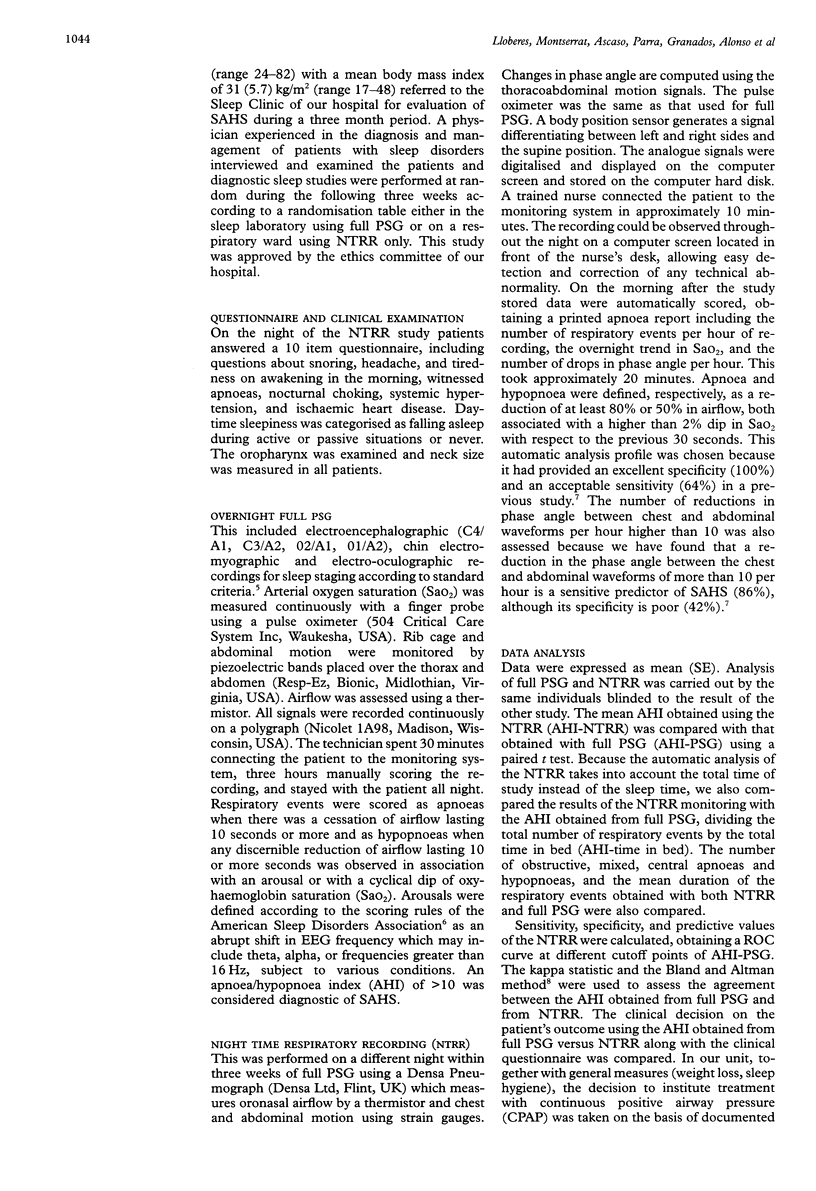

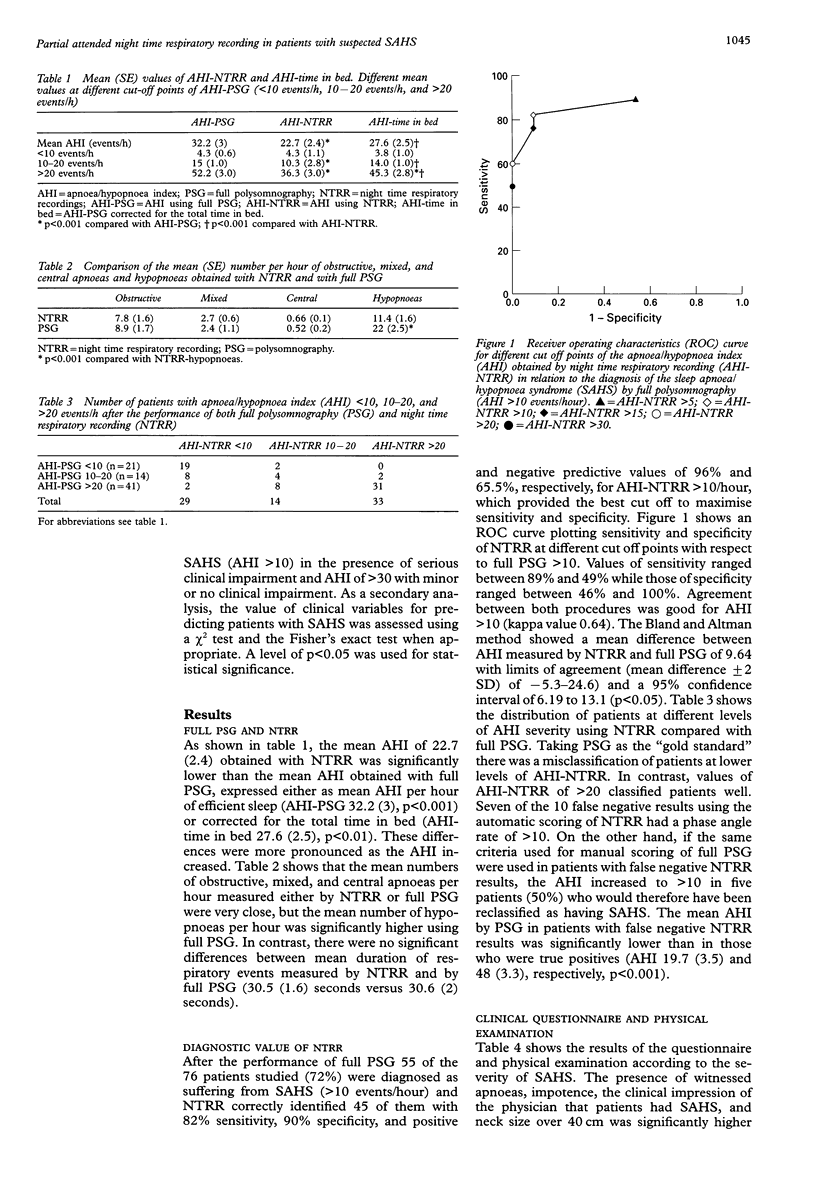

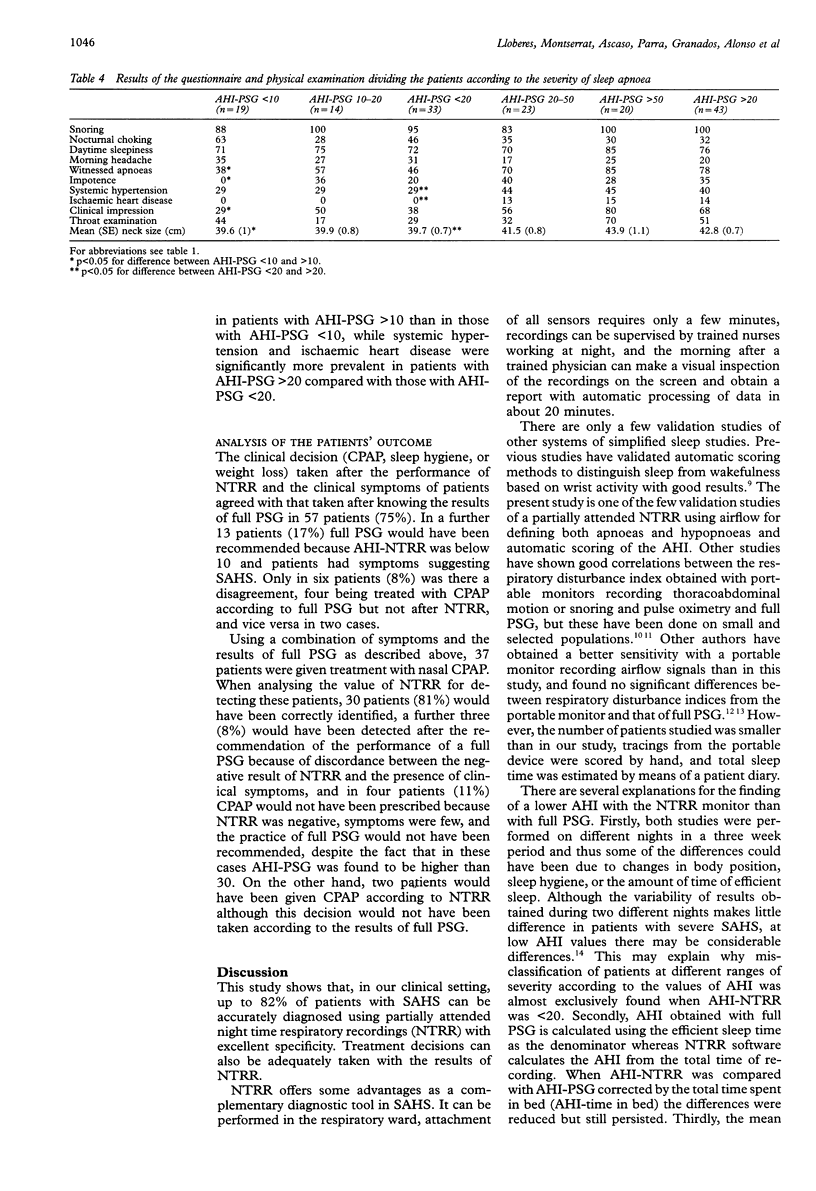

BACKGROUND: Laboratory full polysomnography (PSG) is considered to be the gold standard for the diagnosis of the sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome (SAHS), but it is expensive and time consuming. A study was undertaken to evaluate the diagnostic usefulness of a partially attended night time respiratory recording (NTRR) and a clinical questionnaire in patients with suspected SAHS in comparison with full PSG. METHODS: Seventy six patients (54 men) of mean (SD) age 51 (11.5) years with a body mass index of 31 (5.7) kg/m2 were studied at random on two different nights with full PSG at the sleep laboratory and with NTRR on a respiratory ward. NTRR records oximetry, airflow, chest and abdominal motion. All signals were continuously displayed on a computer screen throughout the night and respiratory events were scored automatically the following morning. All patients completed a clinical questionnaire. RESULTS: Mean values of the apnoea/hypopnoea index (AHI) using NTRR were lower than those obtained with full PSG (22.7 (2.4) versus 32.2 (3) events/hour) which was mainly due to underrecognition of hypopnoeas. Sensitivity and specificity of NTRR for the diagnosis of SAHS were 82% and 90%, respectively, taking as reference AHI > 10 on full PSG (AHI-PSG > 10). The mean (+/-2SD) difference in AHI between the two methods was 9.6 (range -5.4-24.6) (95% confidence interval 6.2 to 13). Symptoms of witnessed apnoeas, impotence, the overall clinical impression of a trained physician, and a neck size over 40 cm were significantly more prevalent in patients with AHI-PSG of > 10, but impotence was the only clinical feature significantly more prevalent in patients with false negative compared with true negative NTRR results that helped to distinguish patients with NTRR < 10 but AHI-PSG > 10. CONCLUSIONS: NTRR is a helpful and easy complementary diagnostic tool in clinical practice because it detects patients with moderate to severe SAHS reasonably well and therefore can be useful for confirming a diagnosis of SAHS and also for treatment decisions. It is suggested that patients with suspicion of SAHS should be initially studied by NTRR. When NTRR is negative, a full PSG should be performed if witnessed apnoeas, impotence, systemic hypertension, ischaemic heart disease, and a trained physician's clinical impression of SAHS are present.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bland J. M., Altman D. G. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986 Feb 8;1(8476):307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco O., Montserrat J. M., Lloberes P., Ascasco C., Ballester E., Fornas C., Rodriguez-Roisin R. Visual and different automatic scoring profiles of respiratory variables in the diagnosis of sleep apnoea-hypopnoea syndrome. Eur Respir J. 1996 Jan;9(1):125–130. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09010125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker B. D., Olson L. G., Saunders N. A., Hensley M. J., McKeon J. L., Allen K. M., Gyulay S. G. Estimation of the probability of disturbed breathing during sleep before a sleep study. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990 Jul;142(1):14–18. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas N. J., Thomas S., Jan M. A. Clinical value of polysomnography. Lancet. 1992 Feb 8;339(8789):347–350. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91660-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsellem H. A., Corson W. A., Rappaport B. A., Hackett S., Smith L. G., Hausfeld J. N. Verification of sleep apnea using a portable sleep apnea screening device. South Med J. 1990 Jul;83(7):748–752. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199007000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyulay S., Gould D., Sawyer B., Pond D., Mant A., Saunders N. Evaluation of a microprocessor-based portable home monitoring system to measure breathing during sleep. Sleep. 1987 Apr;10(2):130–142. doi: 10.1093/sleep/10.2.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J., Kryger M. H., Zorick F. J., Conway W., Roth T. Mortality and apnea index in obstructive sleep apnea. Experience in 385 male patients. Chest. 1988 Jul;94(1):9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redline S., Tosteson T., Boucher M. A., Millman R. P. Measurement of sleep-related breathing disturbances in epidemiologic studies. Assessment of the validity and reproducibility of a portable monitoring device. Chest. 1991 Nov;100(5):1281–1286. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.5.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan C. E., Issa F. G., Berthon-Jones M., Eves L. Reversal of obstructive sleep apnoea by continuous positive airway pressure applied through the nares. Lancet. 1981 Apr 18;1(8225):862–865. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)92140-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster J. B., Kripke D. F., Messin S., Mullaney D. J., Wyborney G. An activity-based sleep monitor system for ambulatory use. Sleep. 1982;5(4):389–399. doi: 10.1093/sleep/5.4.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittig R. M., Romaker A., Zorick F. J., Roehrs T. A., Conway W. A., Roth T. Night-to-night consistency of apneas during sleep. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984 Feb;129(2):244–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young T., Palta M., Dempsey J., Skatrud J., Weber S., Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993 Apr 29;328(17):1230–1235. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]