Abstract

Signaling through the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathways mediates the actions of a plethora of hormones, growth factors, cytokines, and neurotransmitters upon their target cells following receptor occupation. Overactivation of these pathways has been implicated in a number of pathologies, in particular a range of malignancies. The tight regulation of signaling pathways necessitates the involvement of both stimulatory and terminating enzymes; inappropriate activation of a pathway can thus result from activation or inhibition of the two signaling arms. The focus of this review is to discuss, in detail, the activities of the identified families of phosphoinositide phosphatase expressed in humans, and how they regulate the levels of phosphoinositides implicated in promoting malignancy.

Keywords: phosphoinositides, phosphatases/lipid, lipid kinases, cancer, phosphoinositide 3-kinase

A series of tightly regulated lipid kinase and phosphatase enzyme activities coordinately convert phosphatidylinositol (PtdIns) into a network of phosphorylated derivatives, collectively called phosphoinositides. These differ in the number and position of the phosphate groups on the inositol head group: three PtdIns monophosphate isomers [PtdIns(3)P, PtdIns(4)P, and PtdIns(5)P], three PtdIns bisphosphate isomers [PtdIns(3,4)P2, PtdIns(3,5)P2, and PtdIns(4,5)P2], and a single trisphosphate isomer [PtdIns(3,4,5)P3] [reviewed in (1, 2)].

Phosphoinositide signaling is an extensively studied topic with clear evidence linking the pathway from the kinase to activation of AKT and TOR to a number of disease states. While these include malignancies, there is also strong evidence for other diseases, such as overgrowth syndromes. Most studies have focused upon the importance of the kinase pathways in regulating phosphoinositide signaling; however, all signaling pathways are subject to negative as well as positive control, pointing to a key role for inositol phospholipid phosphatases in cell and tissue regulation in health and disease. This review focuses upon this aspect of regulation, considering the importance of the many phosphatases that can act upon phosphoinositides, and we further consider the importance of each in malignancy.

PHOSPHOINOSITIDE 3-KINASES

In mammals, the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) isoforms responsible for phosphorylating the 3-hydroxyl group of the inositol headgroup of PtdIns, PtdIns(4)P, and PtdIns(4,5)P2 have been divided into three classes: class I, class II, and class III.

In response to activation of cell surface receptors, class I PI3Ks are responsible for phosphorylating PtdIns(4,5)P2 to generate PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 (3). There are four class I PI3Ks that exist as heterodimers of regulatory and catalytic subunits. The four distinct catalytic subunits, p110α, -β, -γ, and -δ, are further divided into class IA (p110α, -β, and -δ) and class IB (p110γ). Class IA PI3Ks bind the SH2 domain containing the p85 family of regulatory subunits (p85α, p85β, and p55) that bind to protein tyrosine phosphate residues in activated receptors, thus relieving p85-mediated inhibition of p110 catalytic subunits and facilitating access to PI3K lipid substrates in cell membranes. The single class IB PI3K, p110γ, can bind p84 or p101 regulatory subunits that mediate heterotrimeric G-protein βγ-subunit activation of p110γ (4, 5).

The class II PI3Ks, PI3K-C2α, PI3K-C2β, and PI3K-C2γ, phosphorylate PtdIns to generate PtdIns(3)P in cells [reviewed in (6)]. There is some evidence that class II PI3Ks can be regulated by activated cell surface receptors, but because they do not have regulatory subunits, the mechanism is unclear (6). Furthermore PI3K-C2α has been reported to phosphorylate PtdIns(4)P to generate PtdIns(3,4)P2 (7).

The sole class III PI3K in mammals, Vps34, phosphorylates PtdIns in cells to generate PtdIns(3)P [reviewed in (8)]. Vps34 is regulated by at least three distinct regulatory complexes (8).

PI3K AND CANCER

Gene amplification of the genes encoding all four p110 catalytic subunits have been reported in several human cancers, including ovarian, prostate, lung, thyroid, cervical, and glioblastoma [reviewed in (9)]. Furthermore, the gene encoding p110α, PIK3CA, is frequently mutated in human cancers such as colorectal, breast, lung, and glioblastoma (10). The consequence of gene amplification and the mutations in p110 subunits is the increase in the basal activity of PI3Ks.

Somatic mutations have also been identified in the gene encoding the p85α subunit, PIK3R1, in colon, breast, pancreatic, and glioblastoma cancers (11). The p85α mutants interact with the p110α, -β, and -δ subunits, but because they have an impaired ability to inhibit the activity of the catalytic subunits, the basal activity of class IA PI3Ks is increased (11).

To date, there have been no somatic mutations in the genes encoding the class II and class III PI3Ks in human cancer.

PI3K SIGNALING PATHWAYS IN CANCER

Since the discovery that the serine/threonine kinase, AKT/PKB, is an effector of PI3K in the mid-nineties (12–16), the enzyme has been identified as the key transducer of oncogenic signaling in numerous human cancers. Activating mutants of AKT have been identified in human cancers such as breast, colorectal, and ovarian (17). The AKT gene family comprises three forms, of which AKT1 and AKT2 are widely expressed, but AKT3 expression appears to be limited to brain tissue. AKT phosphorylates upwards of 200 target proteins that regulate gene expression, protein synthesis, cell cycle progression, cytoskeleton organization, and cell metabolism (18).

PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and PtdIns(3,4)P2 generated in response to growth factor stimulation recruit AKT/PKB to the plasma membrane by binding to its N-terminal pleckstrin homology (PH) domain (19, 20). This interaction has been shown to activate AKT in vitro (19, 21, 22). However, other studies have favored a model in which PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and PtdIns(3,4)P2 binding does not activate AKT (20), but instead recruits the enzyme to the membrane, altering its conformation and allowing the kinase to be fully activated by subsequent phosphorylation at Thr308 and Ser473.

AKT is phosphorylated at Thr308 in the activation loop by a PH domain containing 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1) (23–26). PDK1 only phosphorylates AKT in the presence of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 or PtdIns(3,4)P2 (23–26). The C-terminal PH domain of PDK1 binds to PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and PtdIns(3,4)P2, with weaker binding to PtdIns(4,5)P2, resulting in PDK1 binding to the plasma membrane (25, 27). AKT does not bind PtdIns(4,5)P2 (27). AKT is further activated by phosphorylation at Ser473 in the hydrophobic motif by mTORC2 (28). However, little is known about the upstream activators of mTORC2 in response to growth factors. Interestingly, one report has demonstrated that PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 can directly activate mTORC2 activity in vitro (29).

There is evidence that PDK1 can be recruited to membranes independently of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 or PtdIns(3,4)P2 through its binding to the activated insulin receptor via the adaptor protein, Grb14 (30). Furthermore, the PH domain of PDK1 exhibits a greater binding affinity for PtdIns(3,4,5)P3, PtdIns(3,4)P2, and PtdIns(4,5)P2 than the binding affinity of the PH domain of AKT for PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 (25, 27). Indeed, the binding affinity of PDK1 for PtdIns(4,5)P2 is comparable to the affinity of AKT toward PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 (27). Therefore, AKT membrane localization and activation is potentially more dependent on higher PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and PtdIns(3,4)P2 levels than the levels necessary for PDK1 localization. In this model, PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and PtdIns(3,4)P2 are considered to have redundant abilities to activate AKT and PDK1; however, one study has suggested that both PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and PtdIns(3,4)P2 are required for full activation of AKT (31).

Not all PI3K signals in cancer are transduced by AKT phosphorylation. The levels of phosphorylated AKT in PIK3CA mutant cell lines and human breast tumors are low and anchorage-dependent growth is less dependent on AKT (32). However, PDK1 is highly expressed in PIK3CA mutant breast tissue, and PDK1 expression is required for anchorage-independent growth in PIK3CA mutant cell lines (32). PDK1 is not solely an AKT kinase; it phosphorylates the activation segment of at least 23 AGC kinases [reviewed in (33)]. One of these kinases, the serum and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 3 (SGK3) is phosphorylated by PDK1 at the activation loop (34) and mTORC2 at the hydrophobic motif (35). SGK3 is amplified and hyperactivated in PIK3CA-mutant breast cancer (36), and is required for AKT-independent viability (32), anchorage-independent growth, and spheroid growth (36).

PHOSPHOINOSITIDE PHOSPHATASE ACTIVITIES AND CANCER

Over the last 20 years, there has been a tremendous amount of research that has demonstrated that PI3K/AKT signaling is constitutively activated in a large number of human cancers as a result of gene mutation or amplification of PI3K and AKT. However, the functional loss of the phosphoinositide phosphatases has also been reported to drive the progression of human cancer. There are phosphatases which remove the phosphate group from each of the 3-, 4-, and 5-positions of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and related phosphoinositides. Considering the key role the PI3K/AKT pathway plays in malignancy, changes in the activities of these enzymes will have distinct effects upon the onset and progression of cancer. Thus, this review will highlight the phosphoinositide phosphatase activities expressed in humans and consider their involvement in cancer, recognizing that most data relate to the 3- and 5-phosphatases.

PHOSPHOINOSITIDE 3-PHOSPHATASES

Mammalian phosphoinositide 3-phosphatases can be divided into two major groups: one group comprised of phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) and the transmembrane phosphatase with tensin homology (TPTE) and PTEN homologous inositol lipid phosphatase (TPIP) proteins, and the other group made up of myotubularin (MTM) and MTM-related (MTMR) proteins.

PTEN AND TPIP PROTEINS

PTEN, also known as mutated in multiple advanced cancers (MMAC), was first identified as a candidate tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 10q23 in 1997 (37, 38). PTEN is the best known and most described of phosphoinositide phosphatases that play a role in human malignancy. Somatic homozygous mutations and deletions of PTEN have been detected in glioblastoma, prostate, kidney, melanoma, lung, endometrial, bladder, and breast cancer cell lines and primary tumors (38–43). That same year, it was reported that germline mutations of PTEN were associated with Cowden’s disease, an autosomal dominant cancer predisposition syndrome that has an associated increased risk of cancer (44, 45). Homozygous PTEN knockout mice are embryonic lethal, but PTEN/− mice are viable (46–48). Nevertheless, consistent with the tumor suppressor function of PTEN and the situation observed in Cowden’s disease patients, heterozygous PTEN/− mice exhibited a higher frequency of spontaneous tumor formation compared with wild-type mice (46–48).

Due to its similarity to a subfamily of protein tyrosine phosphatases, the dual specificity phosphatases, in particular the VH1-like family (49), PTEN was initially predicted to be a dual specificity protein phosphatase (38, 42, 50). Subsequent work demonstrated that recombinant PTEN exhibited tyrosine phosphatase (42, 50, 51) and serine/threonine phosphatase activity in vitro (51). Importantly, Myers et al. (51) demonstrated that mutation of the essential cysteine from the invariant signature motif HCxxGxxR found in all the members of the protein tyrosine phosphatase superfamily, PTEN C124S, resulted in loss of tyrosine phosphatase activity in vitro. Consistent with the in vitro results, overexpression of PTEN in NIH-3T3 cells reduced tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase in vitro and in vivo (52). Furthermore, when the phosphatase inactive PTEN C124S mutant was overexpressed in NIH-3T3 and glioblastoma U-89 cell lines, focal adhesion kinase tyrosine dephosphorylation, cell spreading, invasion, and growth were attenuated (52, 53).

Maehama and Dixon (54) suggested that PTEN could dephosphosphorylate negatively charged substrates other than tyrosine and/or serine/threonine phosphoproteins. They based this on the observation that the in vitro catalytic rate activity of PTEN toward protein and peptide substrates was low (42, 50, 51), but was far greater toward highly negatively charged and multi-phosphorylated tyrosine peptide substrates such as polyGlu4Tyr1 (51). When PTEN was overexpressed in HEK293 cells, the levels of insulin-stimulated PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 were found to be significantly reduced, whereas overexpression of the catalytically inactive PTEN C124S mutant resulted in an increase in cellular PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 in the absence of insulin stimulation (54). Furthermore, recombinant PTEN dephosphorylated PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 to PtdIns(4,5)P2 and Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 to Ins(1,4,5)P3 in vitro (54), confirming that PTEN was indeed a lipid phosphatase with activity toward phosphates at the 3-position of the inositol ring.

Myers et al. (55) confirmed that recombinant PTEN catalyzed the dephosphorylation of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 to PtdIns(4,5)P2 and Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 to Ins(1,4,5)P3 in vitro. However, they also demonstrated that in addition to PtdIns(3,4,5)P3, PTEN was able to dephosphorylate PtdIns(3)P and PtdIns(3,5)P2 at the 3-position in vitro (55), in the order of preference PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 = PtdIns(3,4)P2 > PtdIns(3)P > Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 (55).

Interestingly, it was demonstrated that the dephosphorylation activity of the PTEN mutant found in Cowden’s disease, PTEN G129E (44), against phosphotyrosine peptides is unaltered (51), but the activity is significantly reduced against PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 (55).

This result strongly suggested that it is the lipid, rather than the protein phosphatase activity of PTEN that is required for its tumor suppressor function, and that loss of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3-phosphatase activity results in Cowden’s disease (55). Furthermore, in immortalized mouse embryonic fibroblasts isolated from PTEN −/− mice, the levels of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 are elevated and AKT is hyperactivated (56), and in heterozygous PTEN/− mice, the elevated frequency of spontaneous tumor formation is associated with an increased activity of AKT (48). These and subsequent studies have shown that the mechanism underlying the tumor suppressor function of PTEN is the regulation of the cellular pool of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 levels that controls AKT-mediated signaling [reviewed in (57)].

In the Cowden PTEN G129E mutant, the protein phosphatase activity is attenuated, but the PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 phosphatase activity is intact. Thus, the significance of the PTEN protein phosphatase activity for PTEN tumor suppressor function is not clear.

Nevertheless, it has been suggested that this protein phosphatase activity may be relevant to various physiological functions of PTEN, such as regulating cell migration and invasion. In contrast, PTEN Y138C, found in small cell lung carcinoma, dephosphorylates PtdIns(3,4,5)P3, but has no protein phosphatase activity (58). When overexpressed in a glioblastoma cell line, PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 levels and AKT phosphorylation are reduced, but cellular invasion into matrigel is not suppressed (58), arguing against a role for the protein dephosphorylating activity of PTEN in this function. PTEN Y138C displays increased phosphorylation at Thr366. It has therefore been hypothesized to alter PTEN binding to other proteins, and consequently to altering the localization of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 dephosphorylation (58), thereby affecting the physiological consequence of a local change in PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 concentration. The PTEN G129E mutant also displays increased phosphorylation at Thr366. This has been proposed to provide a mechanism whereby the PTEN protein phosphatase activity is required to auto-dephosphorylate PTEN and thereby control lipid phosphatase activity in vivo (58). Of potential importance, however, remains the demonstration that PTEN is a protein tyrosine phosphatase for IRS1, both in vitro and in vivo (59).

In addition to post-translational modification, PTEN activity can be regulated by intracellular localization and recruitment. In particular, PTEN has been demonstrated in both nuclear and mitochondrial compartments, in addition to being found in the cytoplasm and being translocated to the plasma membrane. The nuclear localization of PTEN appears to be regulated by sumoylation of PTEN (60). The function of nuclear PTEN activity is not fully clear, there are reports of nuclear PI3K activity (61), and phosphorylated nuclear AKT has been detected in thyroid adenomas and carcinomas with an increase in phosphorylation detectable in PTEN-null tumors (62). However, He et al. (62) demonstrated that PTEN suppresses translocation of phosphorylated AKT, suggesting that it is the non-nuclear rather than the nuclear PTEN that is critical in cancer. Nevertheless, there is clearly a signaling role for nuclear PtdIns(3,4,5)P3. Blind et al. (63) have demonstrated that PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 binds to and stabilizes the nuclear receptor SF-1 structure, explaining the PI3K-dependent increase of SF-1 activity (64). This group has, however, questioned the importance of PI3K in this process by demonstrating that PtdIns(4,5)P2-associated SF-1 can be modified by IMPK, as well as PTEN. A further role for nuclear PTEN is suggested by its interaction with histone H1 via its C2 domain, thereby regulating chromatin condensation and gene expression (65). The PTEN-histone H1 interaction is not dependent on PTEN phosphatase activity (65), and is thus mediated by protein-protein interaction; the regulation of this process and its regulatory significance in cancer tissues remains unclear.

Mitochondrial PTEN has also been reported, though it has been shown that this is a 70 kDa PTENα which has a 173 amino acid elongated N-terminal region generated through an alternate translation initiation site (66). This form of PTEN is detectable in both the cytoplasm and mitochondria, and in the latter localization it can activate cytochrome oxidase and thus mitochondrial oxidative metabolism. It appears that PTENα physically associates with cytochrome oxidase and that mutagenesis demonstrates that the phosphatase activity is necessary for activation of the oxidase. However, while it has been suggested that cytochrome oxidase activity can be regulated by phosphorylation, with the hypo-phosphorylated form showing greater activity (67), the mutation in PTENα, C297S, that reduces oxidase activity, is equivalent to C124S in PTEN, and thus regulates lipid rather than protein phosphatase activity. The presence of PtdIns(4,5)P2 in mitochondria has been reported (68); however, there is a paucity of evidence for a mitochondrial PI3K, which nevertheless may exist and there could therefore be an as yet unrecognized PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 signaling pathway in mitochondria which could be important in malignancy where energy metabolism is increased.

Hopkins et al. (69) have also reported a longer form of PTEN, which they named PTEN-long. The additional 174 N-terminal amino acids of PTEN-long share homology to the poly-basic residues of the cell-penetrating element of the HIV transactivator of transcription (TAT) protein (70, 71). Consequently, PTEN-long is a membrane-permeable enzyme that is secreted and can enter other cells to antagonize PI3K-AKT signaling (69). PTEN-long is most likely identical to PTENα however, as discussed by Liang et al. (66), due to the absence of peptide sequence data for PTEN-long, this remains to be definitely proven. Furthermore, Liang et al. (66) have proposed, based on sequence analysis and the CUG initiation mechanism, that multiple longer forms of PTEN are likely to be expressed. PTEN-long is not the only PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 phosphatase that has been reported to be secreted from cells, PTEN has also been reported to be secreted from cells inside microvesicles, called exosomes, allowing PTEN to enter and antagonize PI3K-AKT signaling in other cells (72). However, it remains unclear what the physiological function of PTEN and PTEN-long transfer between cells fulfils.

Phosphorylation of residues S380, T382, T383, and S385 in the C terminus of PTEN maintains the phosphatase as a monomer (73, 74). However, when these residues are not phosphorylated, PTEN exists as a dimer that has greater PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 phosphatase activity than the monomer (73). Furthermore, catalytically inactive mutants of PTEN heterodimerize with wild-type PTEN, resulting in the inhibition of the PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 phosphatase activity in a dominant-negative manner (73). This, in turn, results in hyper-activation of PI3K-AKT signaling and increased tumor formation in mice (73). The implications for the clinical outcome of patients that express both wild-type and mutant PTEN proteins are significant based on the dominant-negative effect of the mutant protein. For example, patients with one mutant gene expressing an inactive mutant of PTEN could conceivably have a significant reduction in the PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 phosphatase activity of the remaining wild-type PTEN, whereas patients expressing PTEN mutants that result in reduced protein levels, would not (73).

The dominant-negative effects of cancer-associated PTEN mutants are most likely not just confined to the same cell. The discovery that PTEN is sorted into exosomes, and that PTEN-long is secreted PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 phosphatases that enter other cells to regulate PI3K-AKT signaling, raises the intriguing possibility that catalytically inactive mutants of PTEN could also be transferred from cancer cells to stromal cells. This cell-to-cell communication of cancer-associated PTEN mutants, and the dominant-negative manner in which they can inhibit the catalytic activity of wild-type PTEN could further accentuate tumor progression by hyperactivating PI3K-AKT signaling in the surrounding stromal cells, thus facilitating the formation of a tumor microenvironment that is required to support tumor growth.

Human cells express a single TPTE (75). However, the human enzyme lacks PtdIns(3)P phosphatase activity (76). In contrast, mouse TPTE has been demonstrated to exhibit phosphatase activity in vitro toward PtdIns(3)P, PtdIns(3,4)P2, PtdIns(3,5)P2, and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 (77). TPIP exists as four splice variants (TPIPα, -β, -γ, and -C2) (76, 78, 79). TPIPα, but not TPIPβ, dephosphorylates PtdIns(3)P, PtdIns(3,4)P2, PtdIns(3,5)P2, and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 in vitro (76), and in contrast to PTEN, TPIPα does not dephosphorylate Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 in vitro (76). To date, there are no reports about whether either TPIPγ or TPIPC2 have phosphatase activity. Although both TPTE and TPIP phosphatases have the capacity to dephosphorylate PtdIns(3,4,5)P3, there are no reports, to date, that the genes encoding either activity are mutated or overexpressed in a human cancer; thus, it is likely that these enzymes play a limited role in regulating PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 levels physiologically and their normal physiological role(s) remains open to question.

The PTEN-like phosphatase (PTPMT1) was first identified from database searches using the PTEN active site as a query (80). The recombinant protein exhibited phosphatase activity against PtdIns(5)P, but no other phosphoinositide (80). However, other reports have demonstrated that PTPMT1 can dephosphorylate PtdIns(3,5)P2, PtdIns(3,4)P2, and PtdIns(5)P in vitro (81). Furthermore, PtdIns(5)P is not dephosphorylated in vivo by this enzyme (82), but rather phosphatidylglycerolphosphate is the physiological substrate (82, 83); this is a lipid structurally very similar to PtdIns(5)P (84). This finding questions the importance of PTPMT1 in regulating the levels of cellular phosphoinositides.

However, Shen et al. (81) have reported that PtdIns(3,5)P2 can be dephosphorylated in vivo by the phosphatase. Knockdown of PTPMT1 in cancer cells causes apoptotic death. This is probably brought about through the dual specificity phosphatase being mitochondrially located and its inhibition affects cardiolipin levels leading to modulation of energy metabolism. Nevertheless, this result could suggest that inhibition of this phosphatase could be used in the treatment of cancer (85); however, there are no reports that PTPMT1 is mutated in cancer tissues.

MTM AND RELATED PROTEINS

MTM1 was first identified as the gene mutated in X-linked recessive myotubular myopathy (86). MTM1 was first predicted to be a dual-specificity tyrosine phosphatase (86), and initial in vitro assays with recombinant protein reported that MTM1 exhibited both phosphotyrosine (86, 87) and phosphoserine (87) dephosphorylating activity. However, Taylor, Maehama, and Dixon (88) noted that the catalytic activity of MTM1 toward artificial phosphotyrosine substrates was poor, and reported that the active site of MTM1 shares some similarity to the active site region of suppressor of actin (Sac)1, a phosphoinositide phosphatase. Based on these observations, the authors tested the capability of recombinant MTM1 in dephosphorylating phosphoinositides and inositol phosphates, and reported that the enzyme exhibited greatest activity toward PtdIns(3)P and Ins(1,3)P2 (88). However, the soluble inositol phosphate substrate is dephosphorylated with a 10- to 20-fold reduced rate compared with the lipid substrate, which is thus likely to be the authentic substrate in cells (88, 89). Blondeau et al. (90) also demonstrated that MTM1 dephosphorylated PtdIns(3)P in vitro and, based on cell expression studies using Schizosaccharomyces pombe, reported that MTM1 dephosphorylated PtdIns(3,5)P2 in vivo. Subsequent studies demonstrated that MTM1 could dephosphorylate PtdIns(3)P (89, 91–93) and PtdIns(3,5)P2 (92, 93), both in vitro and in vivo.

The MTMR proteins are close homologs of MTM. MTMR1 can dephosphorylate both PtdIns(3)P (89, 93) and PtdIns(3,5)P2 (93) in in vitro assays. There are also reports that MTMR1 dephosphorylates both lipids in vivo. MTMR2 is also able to dephosphorylate PtdIns(3)P in vitro (89, 91, 94, 95) and in vivo (91) and has also been shown to dephosphorylate PtdIns(3,5)P2 in vitro (94, 95). In addition, MTMR2 can dephosphorylate Ins(1,3)P2, but with a 10-fold lower activity than when dephosphorylating the lipid substrates, making its physiological relevance questionable (89). MTMR3 dephosphorylates PtdIns(3)P in vitro (89, 96–98) and in vivo (97), and PtdIns(3,5)P2 in vitro and in vivo (96, 97). MTMR4 has been reported to dephosphorylate PtdIns(3)P in vitro (98) and in vivo (99). There are, however, no reports that PtdIns(3,5)P2 can be a substrate. MTMR6 dephosphorylates PtdIns(3)P in vitro (89, 92, 100), and PtdIns(3,5)P2 both in vitro (92, 100) and in vivo (100). Nevertheless, there are no reports that MTMR6 can dephosphorylate PtdIns(3)P in vivo. The catalytically inactive MTMR9 is able, however, to regulate the activity of MTMR6 and, as such, determines the substrate specificity in vivo (100). MTMR7 dephosphorylates PtdIns(3)P in vitro (101), and MTMR9 has been shown to increase the in vitro activity (101). MTMR8 dephosphorylates PtdIns(3)P and Ptd(3,5)P2 in vitro, but has only been shown to be active against PtdIns(3)P in vivo (100). MTMR9 regulates activity of MTMR8 in vitro and in vivo, and determines substrate specificity in vivo (100); it is thus a regulatory component rather than an activity, per se. MTMR14 dephosphorylates PtdIns(3)P and PtdIns(3,5)P2 in vitro, but only PtdIns(3)P in vivo (102). These PtdIns(3)P and PtdIns(3,5)P2 substrate specificities, with no reported activities against PtdIns(3,4,5)P3, PtdIns(3,4)P2, or PtdIns(4,5)P2, make the importance of these phosphoinositide phosphatases in the regulation of cell proliferation and malignancy questionable, and indeed no tumors have been reported to exhibit mutation or altered expression of the MTMRs.

PHOSPHOINOSITIDE 4-PHOSPHATASE ACTIVITIES AND CANCER

Dephosphorylation of phosphoinositides at the 4-position is relatively infrequent. Many of the enzymes that catalyze this reaction were identified primarily as inositol polyphosphate phosphatases (INPPs) and, subsequently, as lipid phosphatases.

INPP4A dephosphorylates PtdIns(3,4)P2 at the 4-position in vitro (103) and in vivo (104), and, to lesser extent, demonstrates activity against Ins(3,4)P2 and Ins(1,3,4)P3 in vitro (103). The C2 domain of INNP4A is able to bind PtdIns(3,4)P2, PtdIns(4)P, and phosphatidylserine (104). Furthermore, recombinant INPP4A lacking the C2 domain exhibits significantly reduced activity toward PtdIns(3,4)P2 in vitro, suggesting that this domain regulates substrate binding (104).

INPP4A overexpression in cells has been shown to reduce PtdIns(3,4)P2 (104), suggesting that INPP4A might function to suppress AKT activity. Subsequent work using INPP4A −/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) demonstrated that the level of phosphorylation of AKT at both Thr308 and Ser473 in response to EGF was elevated compared with INPP4A +/+ MEFs (106).

Furthermore, loss of INPP4A resulted in increased cell growth, decreased apoptosis, and increased anchorage-independent growth, and formed tumors in nude mice, in keeping with activation of the AKT signaling cascade (106). INPP4A is thus similar in effect to PTEN in regulating the AKT pathway and cell growth and malignancy.

INPP4B also dephosphorylates PtdIns(3,4)P2 at the 4-position, and to lesser extent both Ins(3,4)P2 and Ins(1,3,4)P3 in vitro (105) and PtdIns(3,4)P2 in vivo (107). The C2 domain of INNP4B selectively binds PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and phosphatidic acid, suggesting that these lipids may play a role in regulating the localization and/or activity of INPP4B in vivo (108). However, this hypothesis remains to be tested. More recently, INNP4B has been demonstrated to dephosphorylate PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and PtdIns(3,4)P2 in vitro, showing a greater preference for PtdIns(3,4)P2 (109). Furthermore, from cellular expression experiments, INPP4B has been shown to selectively dephosphorylate PtdIns(3,4)P2 in vivo (109). The knockdown of INPP4B in a human mammary epithelial cell line resulted in anchorage-independent growth, increased cell migration, and elevated AKT phosphorylation in response to insulin (109). Furthermore, increased INPP4B expression resulted in reduced tumor growth in a xenograft mouse model; whereas, loss of INPP4B expression has been found to correlate with poor patient survival in both breast and ovarian cancer (109). The phosphatidic acid binding of INPP4B, if inhibitory or localizing, could further suggest a cooperative effect with increased phospholipase D activity, which has also been suggested to play a role in breast cancer, particularly metastasis (110).

Fedele et al. (111) reported that decreased INPP4B expression in human breast cancer cell lines elevates AKT signaling and results in increased tumor formation. In keeping with this, INPP4B expression is frequently lost in human breast cancer (111). A reduction in expression of INPP4B in prostate cancer cell lines increases AKT phosphorylation and stimulates cell proliferation (112), whereas overexpression of INPP4B inhibits prostate cancer cell invasion (113). INPP4B expression is reduced in prostate cancer, and patients with lower expression of INPP4B show a decrease in recurrence-free survival (112, 114). These results demonstrate that INPP4B, and probably INPP4A, is a tumor suppressor that inhibits PI3K/AKT signaling.

TMEM55A (also known as type II PtdIns 4,5-bisphosphate 4-phosphatase) and TMEM55B (also known as type I PtdIns 4,5-bisphosphate 4-phosphatase) both contain two putative transmembrane domains at the C terminus, and they dephosphorylate PtdIns(4,5)P2 at the 4-position in vitro (115). TMEM55B has been further reported to dephosphorylate PtdIns(4,5)P2 in vivo (115, 116). In keeping with TMEM55 being unlikely to modulate the AKT pathway, there are no reports of TMEM55 involvement in cancer.

PHOSPHOINOSITIDE 5-PHOSPHATASE ACTIVITIES AND CANCER

The phosphoinositide 5-phosphatases are grouped into four types (I–IV).

The 40 kDa type I inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase, also known as INPP5A, dephosphorylates Ins(1,4,5)P3 and Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 at the 5-position in vitro, but has no activity toward phosphoinositides (117–119). There have been a number of studies that suggested a link between INPP5A activity and cancer. However, siRNA knockdown of INPP5A resulted in increased cellular levels of Ins(1,4,5)P3 and Ins(1,3,4,5)P4, leading to cell transformation and tumor formation in nude mice (120). In addition, INPP5A expression is reduced in human cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma tumors (121). Together these observations suggest that, if important, INPP5A will play a tumor suppressing rather than malignancy promoting role.

The type II 5-phosphatases include INPP5B, oculocerebrorenal syndrome (OCRL) (INPP5F), synaptojanin 1 (SYNJ1/INPP5G), synaptojanin 2 (SYNJ2/INPP5H), INPP5J, and INPP5K [skeletal and muscle enriched INPP (SKIP)].

INPP5B, also known as 75 kDa type II inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase, dephosphorylates PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 (122, 123), PtdIns(4,5)P2 (123–125), Ins(1,4,5)P3 (123–125), and Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 (123) in vitro. Furthermore, INPP5B has been reported to dephosphorylate PtdIns(4,5)P2 in vivo (124). INPP5B does not dephosphorylate PtdIns(3,5)P2 (123). INPP5B has a similar domain organization to OCRL/INPP5F. However, INPP5B does not contain clathrin binding sites, and it has a C-terminal CAAX prenylation sequence (124). To date no human disease or cancer has been associated with INPP5B.

Lowe syndrome, also known as OCRL, is a rare human X-linked developmental disorder that affects brain, kidney, and eye function [reviewed in (126)]. Mutations in the OCRL gene were demonstrated to be responsible for Lowe syndrome, and the OCRL protein was found to share similarity with INPP5B (127).

Patients diagnosed with a related X-linked disorder, called Dent-2 disease, also carry mutations in OCRL (128).

OCRL dephosphorylates Ins(1,4,5)P3 and Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 at the 5-position, and PtdIns(4,5)P2 in vitro, with a greater preference for the lipid substrate (129). Subsequent studies demonstrated that OCRL can also dephosphorylate PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 in vitro (123). However, PtdIns(3,5)P2 is a very poor substrate for INPP5B in vitro (123). Studies using cell lines isolated from patients diagnosed with Lowe syndrome have shown that OCRL dephosphorylates PtdIns(4,5)P2 in vivo (130). Despite its similarity in elevating phosphoinositide signaling, there is surprisingly no association between OCRL and cancer.

SYNJ1/INPP5G contains two phosphoinositide phosphatase domains: a Sac1-like phosphatase domain and an inositol 5-phosphatase domain (131, 132). SYNJ1 dephosphorylates PtdIns(4,5)P2 (123, 132–134) and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 (123, 131, 134) in vitro. PtdIns(3,5)P2 is a poor substrate for SYNJ1 (123). Furthermore, SYNJ1 can dephosphorylate Ins(1,4,5)P3 (123, 132), and to a lesser extent Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 (123), in vitro. The isolated inositol 5-phosphatase domain of SYNJ1 dephosphorylates PtdIns(3,4,5)P3, PtdIns(4,5)P2, PtdIns(3,5)P2, Ins(1,4,5)P3, and Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 in vitro (135), and the isolated Sac1 domain of SYNJ1 can dephosphorylate PtdIns(3)P, PtdIns(4)P, and PtdIns(3,5)P2 in vitro (136).

Consistent with these studies of the activities of the individual phosphatase domains, full length SYNJ1 has been reported to dephosphorylate both PtdIns(3)P and PtdIns(4)P, in addition to PtdIns(4,5)P2, in vitro (137, 138). Furthermore, inactivating mutants in the Sac1 domain of SYNJ1 results in loss of activity toward PtdIns(3)P and PtdIns(4)P, but not PtdIns(4,5)P2, in vitro (137, 138). Conversely, inactivating mutants in the inositol 5-phosphatase domain of SYNJ1 results in loss of activity toward PtdIns(4,5)P2, but not PtdIns(3)P and PtdIns(4)P (138). The study of these mutants has established that both the Sac1 and the inositol 5-phosphatase domain are required for SYNJ1 function in endocytic recycling of synaptic vesicles (138). PtdIns(4,5)P2 levels are elevated in SYNJ1 −/− primary cortical neurons compared with wild-type control cells; however, PtdIns(4)P levels are not altered (140). Elevated PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 levels in SYNJ1 whole brain tissue have only been observed when brain lysates were incubated with 32P-ATP (140).

SYNJ2/INPP5H is a highly homologous enzyme to SYNJ1 and also contains a Sac1 phosphoinositide phosphatase domain and an inositol 5-phosphatase domain (133, 141). In vitro, SYNJ2 has been reported to dephosphorylate PtdIns(3,4,5)P2 (123) and PtdIns(4,5)P2 (123, 133). PtdIns(3,5)P2 is a poor substrate for SYNJ2 (123). It has also been proposed that SYNJ2 can also dephosphorylate Ins(1,3,5)P3 and Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 in vitro (141); however, other groups have reported that Ins(1,3,5)P3 and Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 are not substrates for SYNJ2 (123). The isolated Sac1 domains of SYNJ2 dephosphorylate PtdIns(3)P, PtdIns(4)P, and PtdIns(3,5)P2 in vitro (142). However, it remains to be established whether full length SYNJ2 can dephosphorylate PtdIns(3)P or PtdIns(4)P. Furthermore, the substrate selectivity of SYNJ2 in cells has not been reported.

There is no reported evidence that SYNJ1 and SYNJ2 are associated with cancer. However, SYNJ2 interacts with Rac1, and siRNA knockdown of either SYNJ2 or Rac1 in glioblastoma cells resulted in reduced cell migration and invasion (143), suggesting a possible, if as yet ill-defined, role in malignancy.

INPP5J, also known as proline-rich inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase, was identified through sequence similarity to the conserved residues in the phosphoinositide 5-phosphatase catalytic domains (144). INPP5J dephosphorylates at the 5-position on the inositol ring of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 (123, 145), PtdIns(4,5)P2 (123, 144), Ins(1,4,5)P3, and Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 in vitro (144). Cellular studies, in which INPP5J was downregulated through the use of siRNA, showed recruitment of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3-binding PH domains to the plasma membrane of growth factor-stimulated COS-1 cells, thereby suggesting that INPP5J dephosphorylates PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 in vivo, pointing to this being an authentic lipid phosphatase (145).

Overexpression of INPP5J in PC12 cells decreased PtdIns(3,4,5)P2 levels (as determined by the cellular localization of a PtdIns(3,4,5)P3-specifc binding GFP-PH domain), and consequently decreased AKT Ser473 phosphorylation (145). This study demonstrated that INPP5J is a negative regulator of PI3K/AKT signaling (145). Subsequent studies have identified INPP5J to have a tumor suppressor function in melanoma (146). INPP5J expression is downregulated in melanoma tissue, and the overexpression of INPP5J inhibited AKT activation (146). Furthermore, overexpression of INPP5J inhibited cell proliferation, and ablated melanoma cell survival in vitro and melanoma growth in a xenograft mouse model (146).

INPP5J expression has been shown to be downregulated in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) tissue, compared with normal tissue (147). Furthermore overexpression of INPP5J in ESCC cell lines results in decreased pAKT Ser473, with decreased rates of both cell proliferation and anchorage-independent growth (147).

Moreover, ESCC cell lines overexpressing INPP5J exhibited diminished tumor formation in a xenograft mouse model, compared with vector control cell lines with reduced pAKT Ser473 levels detected in the tumor tissue (147). This demonstrates, therefore, that INPP5J overexpression inhibits ESCC tumorigenicity in vitro and in vivo.

INPP5K, also known as SKIP, was identified on the basis of sequence homology to other 5-phosphatases (148). INPP5K dephosphorylates PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 at the 5-position (123, 148, 149), and similarly the 5-position of PtdIns(4,5)P2 (123, 148, 149). INPP5K has further been reported to dephosphorylate Ins(1,4,5)P3 and Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 in vitro in some studies (148), but not others (123, 149). PtdIns(3,5)P2 is a very poor substrate for INPP5K (123, 149). INPP5K has been shown to regulate PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 levels in response to growth factors (150, 151), suggesting that the physiological substrate for INPP5K is PtdIns(3,4,5)P3. In keeping with this, decreased expression of INPP5K in C2C12 myoblast cells has been reported to elevate AKT phosphorylation in response to insulin (148). INPP5K expression is decreased in lung carcinoma (152) and increased in renal cancer (153). This contrasting data suggests that it is unlikely that INPP5K plays a role in malignancy and, further, there are no reports that INPP5K can function as a tumor suppressor.

SHIP1/INPP5D and SHIP2/INPPL1 are SH2-containing type III inositol phosphatases (154) that associate with adaptor proteins, such as Shc (155), and immune receptors (156). SHIP1 catalyzes the 5-dephosphorylation of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 (154, 157–160) and Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 (154, 157, 158, 161) and Ins(1,4,5)P3 (154, 157, 158) were initially reported not to be substrates for SHIP1 in vitro; however, more recent studies have reported that SHIP1 can indeed dephosphorylate PtdIns(4,5)P2 in vitro (159, 162). Mutations in SHIP1 have only been found infrequently in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (163).

Nevertheless, treatment of hematopoietic cancer cells with a SHIP1 inhibitor resulted in reduced growth and increased apoptosis (164, 165); this suggests that SHIP1 has proto-oncogenic activity, possibly by facilitating cancer progression through the generation of PtdIns(3,4)P2 from PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and thereby activating a different group of PH-domain-containing proteins such as TAPP1.

Soon after SHIP1 was cloned and characterized, a second SH2-containing inositol phosphatase, SHIP2, was identified (166, 167). SHIP2 dephosphorylates at the 5-position PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 in vitro (168). Subsequent studies confirmed that SHIP2 dephosphorylates PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 (169–171) and Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 in vitro (169, 171), but that the enzyme also dephosphorylates Ins(1,2,3,4,5)P5, Ins(1,4,5,6)P4, Ins(2,4,5,6)P4, and PtdIns(3,5)P2 (169). SHIP2 does not dephosphorylate Ins(1,4,5)P3 (168), but cellular studies have shown that overexpression of SHIP2 decreases PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and PtdIns(4,5)P2 levels, suggesting that both lipids are physiological substrates (170). Consistent with this report, SHIP2 has been shown to regulate both PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and PtdIns(4,5)P2 levels in cells (172).

SHIP2 levels are elevated in breast cancer cell lines and tissue (173, 174). Knockdown of SHIP2 expression reduces EGF-stimulated AKT phosphorylation (175), cell proliferation in culture, and tumorigenesis in vivo (173). Furthermore, overexpression of SHIP2 in a squamous cell carcinoma cell line resulted in an increase in the number of invadopodia (176). This suggests that SHIP2 has proto-oncogenic activity; however, this picture is complicated in that it does not apply to all cancers; indeed, overexpression of SHIP2 in glioblastoma cells results in decreased AKT phosphorylation (170).

INPP5E, also known as pharbin and 72 kDa polyphosphate 5-phosphatase, is the only type IV 5-phosphatase expressed in mammalian cells. INPP5E is widely expressed, with the greatest expression detected in the heart, testis, and brain (159, 177). INPP5E dephosphorylates at the 5-position PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 (159, 177, 178), PtdIns(4,5)P2 (159, 178, 179), and PtdIns(3,5)P2 (177) in vitro. In contrast, other reports have suggested that neither PtdIns(4,5)P2 (177) nor PtdIns(3,5)P2 (178) are substrates for INPP5E in vitro. Furthermore, it has been reported that Ins(1,4,5)P3 and Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 can be dephosphorylated by INPP5E (179); however, other studies have shown they are not substrates (159, 177). Thus the substrate specificity of this phosphatase remains unclear.

Mutations in INPP5E have been detected in patients diagnosed with Joubert syndrome (180). Joubert syndrome is characterized by a specific midbrain-hindbrain malformation, which is variably associated with retinal dystrophy, nephronophthisis, liver fibrosis, and polydactyly [reviewed in (181)]. The analysis of the in vitro phosphatase activites of the mutants of INPP5E associated with Joubert syndrome demonstrated that the loss of activity toward PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 was greater than the loss of activity against PtdIns(4,5)P2 (180), implicating a defect in AKT signaling in the disease. INPP5E mutations have also been detected in patients diagnosed with MORM syndrome (182). MORM syndrome is an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by mental retardation, obesity, congenital retinal dystrophy, and micropenis in males (183).

However, the INPP5E mutants found in MORM syndrome result in premature truncation of the protein, with loss of the C-terminal CAAX motif and loss of phosphatase activity (182) pointing to over-activation of phosphoinositide signaling. In keeping with these suggested disease consequences, INPP5E has been shown to regulate the levels of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 (184, 185) and PtdIns(3,5)P2 (184, 185) in vivo. INPP5E overexpression inhibits AKT phosphorylation at Thr308 and Ser473 in response to PDGF (184) and insulin-like growth factor (178), demonstrating that INPP5E is a physiologically relevant negative regulator of PI3K/AKT signaling. Several studies have associated INPP5E with cancer; however, INPP5E expression has also been reported to be increased in some cancers, such as cervical (186), but in metastatic adenocarcinoma compared with primary tumors the expression of INPP5E is downregulated (187). This could reflect different regulation in these tissue types or that the mutation of signaling in these cancer types may differ and thus ablating AKT signaling may be more or less critical for the different tumor types.

THE SAC PHOSPHATASES AND CANCER

The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae Sac1 protein is the prototypical member of a family of Sac1 domain-containing proteins. Sac1 was first identified as a mutant allele that suppressed conditional-lethal temperature-sensitive mutants of actin (188) and secretory protein 14 (sec14) (PtdIns transfer protein) (189). Analysis of the phosphoinositide levels in Sac1 deletion mutants has shown that Sac1 regulates the levels of PtdIns(4)P, PtdIns(3)P, and PtdIns(3,5)P2 (136, 190–192). Consistent with these studies, the isolated Sac1 domain dephosphorylates PtdIns(4)P, PtdIns(3)P, and PtdIns(3,5)P2 in vitro (190, 191). PtdIns(4,5)P2 is not a substrate for the Sac1 domain in vitro (190, 191). On the basis of sequence similarities with the Sac1 phosphatase domain, mammalian cells are found to express five Sac1 domain-containing proteins, SAC1M1L, Fig4/SAC3, SAC2/INPP5F, and the SYNJs. SAC1M1L is the mammalian ortholog of the S. cerevisiae Sac1 protein. SAC1M1L dephosphorylates PtdIns(3)P and PtdIns(4)P in vitro, but not PtdIns(3,5)P2 (193). To date, there are no reports linking SAC1M1L with cancer.

Yeast Fig4 was first identified from a screen that identified pheromone-regulated genes required for yeast mating (194). Fig4 was subsequently discovered to regulate the PtdIns(3,5)P2 levels necessary for vacuole size control (195) and was shown to dephosphorylate PtdIns(3,5)P2 in vitro (196). Fig4 also activates the Fab1 kinase responsible for PtdIns(3,5)P2 synthesis; so consequently, deletion of Fig4 resulted in decreased levels of PtdIns(3,5)P2 (197). The mammalian ortholog of Fig4, SAC3, dephosphorylates PtdIns(3,4,5)P3, PtdIns(4,5)P2, and PtdIns(3,5)P2 in vitro (198). In contrast, the isolated Sac1 domain of Fig4 dephosphorylates PtdIns(3)P, PtdIns(4)P, and PtdIns(3,5)P2 in vitro, but not PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 or PtdIns(4,5)P2 (199). However, data from cellular-based assays using siRNA knockdown of Fig4 (198) and Fig4 −/− MEFs (200) shows that loss of Fig4 results in a decrease in PtdIns(3,5)P2, but no significant changes in PtdIns(3)P, PtdIns(4)P, and PtdIns(4,5)P2 (198, 200). To date, there are no reports implicating Fig4/SAC3 and cancer.

SAC2/INPP5F dephosphorylates PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and PtdIns(4,5)P2 at the 5-position in vitro (201). In contrast, PtdIns(3)P, PtdIns(4)P, or PtdIns(3,5)P2 are not substrates for SAC2 (201).

Through the use of an ELISA-based assay, PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 levels were shown to be increased in Sac2 −/− mice (202), suggesting that PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 is the physiological substrate. However, more recent studies have shown that Sac2 selectively dephosphorylates PtdIns(4)P in vitro (203, 204). Consequently, more work will be needed to determine the true physiological substrate for Sac2. However, similar to the other SAC proteins, there are no reports linking SAC2/INPP5F with cancer.

WHICH PHOSPHATASES PLAY A ROLE IN MALIGNANCY?

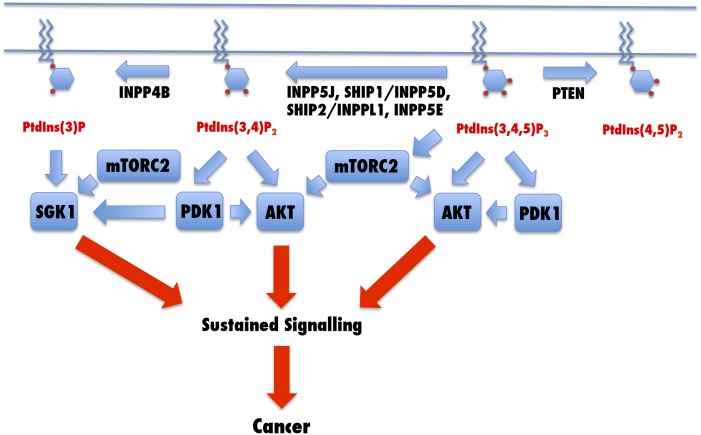

Table 1 draws together the substrate specificity and the evidence for a role for the phosphatases in malignancy. It is notable from the table that, while there are a plethora of phosphatase activities which are capable of dephosphorylating phosphoinositides, including thirteen active against PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and five against PtdIns(3,4)P2, only PTEN, INPP4B, INPP5J, INPP5D, INPPL1, and INPP5E have been implicated in the promotion of malignancy through either mutation or altered expression. This may point to it only being these enzymes that regulate PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and PtdIns(3,4)P2 concentrations physiologically, or alternatively, it may be that these are the only enzymes which regulate the level of the lipid in response to growth factors: such regulation leads to activation of AKT and Tor, as outlined in Fig. 1. The other enzymes may therefore play a greater role in regulating acute PI3K signaling.

TABLE 1.

Human phosphatidylinositolphosphate activities and cancer

| Approved Gene Symbol | Location | Approved Name | Lipid Phosphatase Reaction(s) Catalyzed | Mutated or Altered Expression in Cancer Tissue |

| PTEN | 10q23 | Phosphatase and tensin homolog (MMAC1, TEP1) | PtdIns(3)P → PtdIns | Yes |

| PtdIns(3,4)P2 → PtdIns(4)P | ||||

| PtdIns(3,5)P2 → PtdIns(5)P | ||||

| PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 → PtdIns(4,5)P2 | ||||

| TPTE2 | 13q12.11 | Transmembrane phosphoinositide 3-phosphatase and tensin homolog 2 (TPTE and PTEN homologous inositol lipid phosphatase, TPIP) | PtdIns(3)P → PtdIns | No reports to date |

| PtdIns(3,4)P2 → PtdIns(4)P | ||||

| PtdIns(3,5)P2 → PtdIns(5)P | ||||

| PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 → PtdIns(4,5)P2 | ||||

| PTPMT1 | 11p11.2 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, mitochondrial 1 (phosphatidylglycerophosphatase and protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1) | PtdIns(5)P → PtdIns | No reports to date |

| PtdIns(3,4)P2 → PtdIns(4)P | ||||

| PtdIns(3,5)P2 → PtdIns(5)P | ||||

| Phosphatidylglycerophosphate → phosphatidylglycerol | ||||

| MTM1 | Xq27.3-q28 | Myotubularin 1 | PtdIns(3)P → PtdIns | No reports to date |

| PtdIns(3,5)P2 → PtdIns(5)P | ||||

| MTMR1 | Xq28 | Myotubularin related protein 1 | PtdIns(3)P → PtdIns | No reports to date |

| PtdIns(3,5)P2 → PtdIns(5)P | ||||

| MTMR2 | 11q22 | Myotubularin related protein 2 | PtdIns(3)P → PtdIns | No reports to date |

| PtdIns(3,5)P2 → PtdIns(5)P | ||||

| MTMR3 | 22q12.2 | Myotubularin related protein 3 (FYVE domain-containing dual specificity protein phosphatase 1, FYVE-DSP1) | PtdIns(3)P → PtdIns | No reports to date |

| PtdIns(3,5)P2 → PtdIns(5)P | ||||

| MTMR4 | 17q22-q23 | Myotubularin related protein 4 (FYVE domain-containing dual specificity protein phosphatase 2, FYVE-DSP2) | PtdIns(3)P → PtdIns | No reports to date |

| MTMR6 | 13q12 | Myotubularin related protein 6 | PtdIns(3)P → PtdIns | No reports to date |

| PtdIns(3,5)P2 → PtdIns(5)P | ||||

| MTMR7 | 8p22 | Myotubularin related protein 7 | PtdIns(3)P → PtdIns | No reports to date |

| MTMR8 | Xq11.2-q12 | Myotubularin related protein 8 | PtdIns(3)P → PtdIns | No reports to date |

| PtdIns(3,5)P2 → PtdIns(5)P | ||||

| MTMR14 | 3p26 | Myotubularin related protein 14 (hJumpy) | PtdIns(3)P → PtdIns | No reports to date |

| PtdIns(3,5)P2 → PtdIns(5)P | ||||

| INPP4A | 2q11.2 | Inositol polyphosphate-4-phosphatase, type I, 107 kDa | PtdIns(3,4)P2 → PtdIns(3)P | No reports to date |

| INPP4B | 4q31.1 | Inositol polyphosphate-4-phosphatase, type II, 105 kDa | PtdIns(3,4)P2 → PtdIns(3)P | Yes |

| PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 → PtdIns(3,5)P2 | ||||

| TMEM55A | 8q21.3 | Transmembrane protein 55A (type 2 PtdIns 4,5-bisphosphate 4-phosphatase) | PtdIns(4,5)P2 → PtdIns(5)P | No reports to date |

| TMEM55B | 14q11.1 | Transmembrane protein 55B (type 1 PtdIns 4,5-bisphosphate 4-phosphatase) | PtdIns(4,5)P2 → PtdIns(5)P | No reports to date |

| INPP5B | 1p34 | Inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase, 75 kDa (OCRL2) | PtdIns(4,5)P2 → PtdIns(4)P | No reports to date |

| PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 → PtdIns(3,4)P2 | ||||

| OCRL | Xq25 | Oculocerebrorenal syndrome of Lowe (LOCR, NPHL2, OCRL1, INPP5F, OCRL-1) | PtdIns(4,5)P2 → PtdIns(4)P | No reports to date |

| PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 → PtdIns(3,4)P2 | ||||

| SYNJ1 | 21q22.2 | Synaptojanin 1 (INPP5G) | PtdIns(3)P → PtdIns | No reports to date |

| PtdIns(4)P → PtdIns | ||||

| PtdIns(4,5)P2 → PtdIns(4)P | ||||

| PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 → PtdIns(3,4)P2 | ||||

| SYNJ2 | 6q25.3 | Synaptojanin 2 (INPP5H) | PtdIns(4,5)P2 → PtdIns(4)P | No reports to date |

| INPP5J | 22q12.2 | Inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase J (PIPP) | PtdIns(4,5)P2 → PtdIns(4)P | Yes |

| PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 → PtdIns(3,4)P2 | ||||

| INPP5K | 17p13.3 | Inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase K (skeletal muscle and kidney enriched inositol phosphatase, SKIP) | PtdIns(4,5)P2 → PtdIns(4)P | No reports to date |

| PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 → PtdIns(3,4)P2 | ||||

| INPP5D | 2q37.1 | Inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase, 145 kDa (Src homology-2 domain-containing inositol 5-phosphatase 1, SHIP1) | PtdIns(4,5)P2 → PtdIns(4)P | Yes |

| PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 → PtdIns(3,4)P2 | ||||

| INPPL1 | 11q23 | Inositol polyphosphate phosphatase-like 1 (Src homology-2 domain-containing inositol 5-phosphatase 2, SHIP2) | PtdIns(4,5)P2 → PtdIns(4)P | Yes |

| PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 → PtdIns(3,4)P2 | ||||

| INPP5E | 9q34.3 | Inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase, 72 kDa (Joubert syndrome locus 1, JBTS1) | PtdIns(3,5)P2 → PtdIns(3)P | Yes |

| PtdIns(4,5)P2 → PtdIns(4)P | ||||

| PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 → PtdIns(3,4)P2 | ||||

| SAC1M1L | 3p21.3 | SAC1 suppressor of actin mutations 1-like (yeast) (hSac1, SAC1) | PtdIns(3)P → PtdIns | No reports to date |

| PtdIns(4)P → PtdIns | ||||

| FIG4 | 6q21 | FIG4 homolog, SAC1 lipid phosphatase domain containing (S. cerevisiae) (hSac3, SAC3, CMT4J) | PtdIns(3,5)P2 → PtdIns(3)P | No reports to date |

| PtdIns(4,5)P2 → PtdIns(4)P | ||||

| PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 → PtdIns(3,4)P2 | ||||

| INPP5F | 10q26.13 | Inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase F (hSac2, SAC2) | PtdIns(4)P → PtdIns | No reports to date |

| PtdIns(4,5)P2 → PtdIns(4)P | ||||

| PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 → PtdIns(3,4)P2 |

Fig. 1.

Inactivation of the phosphoinositide phosphatases PTEN, INPP5J, SHIP1/INPP5D, SHIP2/INPPL1, INPP5E, and INPP4B results in sustained PDK1- and AKT-mediated cell signaling as a result of deficient PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and PtdIns(3,4)P2 metabolism.

It is also notable that the phosphoinositide phosphatases that act upon lipids other than PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and PtdIns(3,4)P2 have no reported role in regulating malignancy, thereby suggesting that these other phosphoinositides and their synthetic enzymes, which include class II and III PI3Ks, are not involved in cancer. However, with the recent development of class III-selective inhibitors, PtdIns(3)P has been demonstrated to regulate the activity of SGK3 in cells, opening up the possibility that co-inhibition of class I and III PI3Ks could be used to treat human PIK3CA-mutant cancers where SGK3 is amplified and hyper-activated, such as in breast cancer (205). Furthermore class I and III PI3Ks regulate autophagy (206), a cellular process that in some situations helps drive tumor formation (207). Consequently the control of PtdIns(3)P levels in cancer cells could offer an additional therapeutic possibility.

The simultaneous suppression of PTEN, INPP4A, and INPP5J expression by the microRNA, miR-508, has been reported to promote the progression of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by elevating PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and PtdIns(3,4)P2 levels, and AKT activity (147). This work has unveiled a new regulatory mechanism that results in the activation of PI3K signaling and further work will be needed to determine whether miR-508 overexpression in other human cancers suppresses the expression of phosphoinositide phosphatases. Nevertheless, this study highlights the often reported observation that cancer is not a result of a single event; the presence in cells of multiple enzyme activities able to dephosphorylate PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and PtdIns(3,4)P2 points to the need for inhibition of more than one phosphatase to promote disease, a conclusion indicated by the survival of patients with Cowden’s disease.

For many of the phosphoinositide phosphatases studied, multiple substrates have been identified both in vitro and in vivo. Further, in some cases different groups have reported conflicting data upon the same enzyme. These differences have been highlighted in this review, and are most likely a result of the use of different experimental approaches. For example, recombinant phosphatases, or their catalytic domains, are often expressed in bacteria or sf9 cells, or alternatively immunoprecipitated from transfected cell lines and then assayed using nonphysiological lipid substrates, such as C12:0 phosphoinositides, that are not present in human cells. Furthermore, the measurement of phosphoinositide phosphatase activities in cells more often than not relies on radiolabeling and transfection studies that could potentially introduce nonphysiological activities as a result of protein mislocalization due to overexpression. This could result in the transfected phosphatases accessing cellular membranes and substrates not normally accessible to the endogenous enzyme. Furthermore, radiolabeling studies provide no information on the fatty acyl composition of the phosphoinositide substrates, and cells in culture are often deficient in arachidonate, and so consequently, the major species of phosphoinositide found in mammalian tissue are far less prominent (208). Compared with other major classes of phospholipids, such as PtdCho, PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 is unusual in that the number of distinct diacyl species appears to be limited to around five in mammalian cells and tissues, with the most prominent species being C38:4, sn1 C18:0 (stearoyl) and sn2 C20:4 (arachidonyl) (208–211), and C38:3, C36:2, C36:1, and C38:2 being the additional species reported. Furthermore, the C38:4 species of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 is further enriched when compared with the species profile of PtdIns, PtdIns monophosphate, and PtdIns bisphosphate isomers present in cells and tissue (208–211). This suggests that the enzymes that synthesize and degrade PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 must exhibit a degree of selectivity toward the different species, which may have been unappreciated in some of the published in vitro studies. However, the published data supporting this idea is lacking, and it remains to be determined whether the PI3Ks and phosphoinositide phosphatases have different selectivities for each species of their phosphoinositide substrates. Nevertheless, in support of this idea, Schmid et al. (123) demonstrated that the activities of the phosphoinositide phosphatases, SYN1, SYN2, SKIP, INPP5B, and OCRL, in vitro displayed significantly greater activity against natural (C38:4 enriched) PtdIns(4,5)P3 compared with synthetic C32:0 PtdIns(3,4,5)P3. Furthermore, all four phosphoinositide phosphatases dephosphorylated C32:0 PtdIns(4,5)P2 with equal activity, but they each displayed different activities toward natural (C38:4 enriched) PtdIns(4,5)P2, with OCRL exhibiting the greatest activity and SYN2 the least (122).

In parallel it has been interestingly demonstrated that C38:4 PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 is a more effective activator of PDK1 than C32:0 PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 in vitro, suggesting that the length and saturation of the fatty acid moieties of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 can indeed influence function (25). With the recent development of a novel method to measure PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 in cells and tissues (208, 209), and with the potential to refine this method to allow the separation and measurement of the individual PtdIns mono- and bisphosphate isomers together with the availability of appropriate knockout mice, the question of whether the PI3Ks and phosphoinositide phosphatase display different selectivities can start to be addressed. Furthermore, the ability to measure the levels of all the diacyl species of each phosphoinositide in normal and cancer tissues should provide long-needed information on the potential roles of individual phosphoinositide diacyl species in the initiation and progression of human cancer. However, assimilating the very limited information currently available to assess whether the acyl chain composition of phosphoinositide influences binding to target proteins, the available data strongly suggests that C38:4 PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 is the primary “functional” signaling phosphoinositide in cells. Nevertheless, there is no published data that can exclude the possibility that the additional species of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and PtdIns(3,4)P2 [and possibly PtdIns(3)P] have distinct physiological roles, and that the phosphoinositide phosphatases reported to dephosphorylate phosphoinositides have different selectivities for these species, thereby providing a physiological basis for the plethora of phosphatases present in normal and diseased tissues described in this review.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- ESCC

- esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- INPP

- inositol polyphosphate phosphatase

- INPP4

- inositol polyphosphate 4-phosphatase

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblast

- MTM

- myotubularin

- MTMR

- myotubularin-related

- OCRL

- oculocerebrorenal syndrome

- PDK1

- 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1

- PH

- pleckstrin homology

- PI3K

- phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- PtdIns

- phosphatidylinositol

- PTEN

- phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10

- PTPMT1

- phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10-like phosphatase

- Sac

- suppressor of actin

- SGK3

- serum and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 3

- SKIP

- skeletal and muscle enriched inositol polyphosphate phosphatase

- SYNJ

- synaptojanin

- TPIP

- transmembrane phosphatase with tensin homology and phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 homologous inositol lipid phosphatase

- TPTE

- transmembrane phosphatase with tensin homology

This work was supported by funding from the United Kingdom Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rudge S. A., and Wakelam M. J.. 2013. SnapShot: lipid kinases and phosphatases. Cell. 155: 1654–1654.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rudge S. A., and Wakelam M. J.. 2014. SnapShot: lipid kinase and phosphatase reaction pathways. Cell. 156: 376–376.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hawkins P. T., and Stephens L. R.. 2015. PI3K signalling in inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1851: 882–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stephens L. R., Eguinoa A., Erdjument-Bromage H., Lui M., Cooke F., Coadwell J., Smrcka A. S., Thelen M., Cadwallader K., Tempst P., et al. 1997. The G beta gamma sensitivity of a PI3K is dependent upon a tightly associated adaptor, p101. Cell. 89: 105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Voigt P., Dorner M. B., and Schaefer M.. 2006. Characterization of p87PIKAP, a novel regulatory subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma that is highly expressed in heart and interacts with PDE3B. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 9977–9986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maffucci T., and Falasca M.. 2014. New insight into the intracellular roles of class II phosphoinositide 3-kinases. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 42: 1378–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Posor Y., Eichhorn-Gruenig M., Puchkov D., Schoneberg J., Ullrich A., Lampe A., Muller R., Zarbakhsh S., Gulluni F., Hirsch E., et al. 2013. Spatiotemporal control of endocytosis by phosphatidylinositol-3,4-bisphosphate. Nature. 499: 233–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vanhaesebroeck B., Guillermet-Guibert J., Graupera M., and Bilanges B.. 2010. The emerging mechanisms of isoform-specific PI3K signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11: 329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kok K., Nock G. E., Verrall E. A. G., Mitchell M. P., Hommes D. W., Peppelenbosch M. P., and Vanhaesebroeck B.. 2009. Regulation of p110delta PI 3-kinase gene expression. PLoS One. 4: e5145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samuels Y., Wang Z., Bardelli A., Silliman N., Ptak J., Szabo S., Yan H., Gazdar A., Powell S. M., Riggins G. J., et al. 2004. High frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers. Science. 304: 554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaiswal B. S., Janakiraman V., Kljavin N. M., Chaudhuri S., Stern H. M., Wang W., Kan Z., Dbouk H. A., Peters B. A., Waring P., et al. 2009. Somatic mutations in p85α promote tumorigenesis through class IA PI3K activation. Cancer Cell. 16: 463–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andjelković M., Jakubowicz T., Cron P., Ming X. F., Han J. W., and Hemmings B. A.. 1996. Activation and phosphorylation of a pleckstrin homology domain containing protein kinase (RAC-PK/PKB) promoted by serum and protein phosphatase inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 93: 5699–5704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burgering B. M., and Coffer P. J.. 1995. Protein kinase B (c-Akt) in phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase signal transduction. Nature. 376: 599–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cross D. A., Alessi D. R., Cohen P., Andjelkovic M., and Hemmings B. A.. 1995. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature. 378: 785–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franke T. F., Yang S. I., Chan T. O., Datta K., Kazlauskas A., Morrison D. K., Kaplan D. R., and Tsichlis P. N.. 1995. The protein kinase encoded by the Akt proto-oncogene is a target of the PDGF-activated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Cell. 81: 727–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kohn A. D., Kovacina K. S., and Roth R. A.. 1995. Insulin stimulates the kinase activity of RAC-PK, a pleckstrin homology domain containing ser/thr kinase. EMBO J. 14: 4288–4295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carpten J. D., Faber A. L., Horn C., Donoho G. P., Briggs S. L., Robbins C. M., Hostetter G., Boguslawski S., Moses T. Y., Savage S., et al. 2007. A transforming mutation in the pleckstrin homology domain of AKT1 in cancer. Nature. 448: 439–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toker A. 2012. Achieving specifity in AKT signaling in cancer. Adv. Biol. Regul. 52: 78–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frech M., Andjelkovic M., Ingley E., Reddy K. K., Falck J. R., and Hemmings B. A.. 1997. High affinity binding of inositol phosphates and phosphoinositides to the pleckstrin homology domain of RAC/protein kinase B and their influence on kinase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 8474–8481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.James S. R., Downes C. P., Gigg R., Grove S. J., Holmes A. B., and Alessi D. R.. 1996. Specific binding of the Akt-1 protein kinase to phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate without subsequent activation. Biochem. J. 315: 709–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franke T. F., Kaplan D. R., Cantley L. C., and Toker A.. 1997. Direct regulation of the Akt protooncogene product by phosphatidylinositol-3,4-bisphosphate. Science. 275: 665–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klippel A., Kavanagh W. M., Pot D. A., and Williams L. T.. 1997. A specific product of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase directly activates the protein kinase Akt through its pleckstrin homology domain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17: 338–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alessi D. R., Deak M., Casamayor A., Caudwell F. B., Morrice N., Norman D. G., Gaffney P. R., Reese C. B., MacDougall C. N., Harbison D., et al. 1997. Phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (PDK1): structural and functional homology with the Drosophila DSTPK61 kinase. Curr. Biol. 7: 776–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alessi D. R., James S. R., Downes C. P., Holmes A. B., Gaffney P. R., Reese C. B., and Cohen P.. 1997. Characterization of a 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase which phosphorylates and activates protein kinase Balpha. Curr. Biol. 7: 261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stephens L., Anderson K., Stokoe D., Erdjument-Bromage H., Painter G. F., Holmes A. B., Gaffney P. R., Reese C. B., McCormick F., Tempst P., et al. 1998. Protein kinase B kinases that mediate phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate-dependent activation of protein kinase B. Science. 279: 710–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stokoe D., Stephens L. R., Copeland T., Gaffney P. R. J., Reese C. B., Painter G. F., Holmes A. B., McCormick F., and Hawkins P. T.. 1997. Dual role of phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate in the activation of protein kinase B. Science. 277: 567–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Currie R. A., Walker K. S., Gray A., Deak M., Casamayor A., and Downes C. P.. 1999. Role of phosphatidylinositol 3,4-5-trisphosphate in regulating the activity and localization of 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1. Biochem. J. 337: 575–583. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarbassov D. D., Guertin D. A., Ali S. M., and Sabatini D. M.. 2005. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 307: 1098–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gan X., Wang J., Su B., and Wu D.. 2011. Evidence for direct activation of mTORC2 kinase activity by phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 286: 10998–11002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.King C. C., and Newton A. C.. 2004. The adaptor protein Grb14 regulates the localization of 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 37518–37527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scheid M. P., Marignani P. A., and Woodgett J. R.. 2002. Multiple phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent steps in activation of protein kinase B. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 6247–6260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vasudevan K. M., Barbie D. A., Davies M. A., Rabinovsky R., McNear C. J., Kim J. J., Hennessy B. T., Tseng H., Pochanard P., Kim S. Y., et al. 2009. AKT-independent signaling downstream of oncogenic PIK3CA mutations in human cancer. Cancer Cell. 16: 21–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pearce L. R., Komander D., and Alessi D. R.. 2010. The nuts and bolts of AGC protein kinases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11: 9–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kobayashi T., and Cohen P.. 1999. Activation of serum- and glucocorticoid-regulated protein kinase by agonists that activate phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase is mediated by 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (PDK1) and PDK2. Biochem. J. 339: 319–328. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.García-Martínez J. M., and Alessi D. R.. 2008. mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2) controls hydrophobic motif phosphorylation and activation of serum- and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase 1 (SGK1). Biochem. J. 416: 375–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gasser J. A., Inuzuka H., Lau A. W., Wei W., Beroukhim R., and Toker A.. 2014. SGK3 mediates INPP4B-dependent PI3K signaling in breast cancer. Mol. Cell. 56: 595–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li J., Yen C., Liaw D., Podsypanina K., Bose S., Wang S. I., Puc J., Miliaresis C., Rodgers L., McCombie R., et al. 1997. PTEN, a putative protein tyrosine phosphatase gene mutated in human brain, breast, and prostate cancer. Science. 275: 1943–1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steck P. A., Pershouse M. A., Jasser S. A., Yung W. K., Lin H., Ligon A. H., Langford L. A., Baumgard M. L., Hattier T., Davis T., et al. 1997. Identification of a candidate tumour suppressor gene, MMAC1, at chromosome 10q23.3 that is mutated in multiple advanced cancers. Nat. Genet. 15: 356–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cairns P., Evron E., Okami K., Halachmi N., Esteller M., Herman J. G., Bose S., Wang S. I., Parsons R., and Sidransky D.. 1998. Point mutation and homozygous deletion of PTEN/MMAC1 in primary bladder cancers. Oncogene. 16: 3215–3218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guldberg P., Thor Straten P., Birck A., Ahrenkiel V., Kirkin A. F., and Zeuthen J.. 1997. Disruption of the MMAC1/PTEN gene by deletion or mutation is a frequent event in malignant melanoma. Cancer Res. 57: 3660–3663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kohno T., Takahashi M., Manda R., and Yokota J.. 1998. Inactivation of the PTEN/MMAC1/TEP1 gene in human lung cancers. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 22: 152–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li L., Ernsting B. R., Wishart M. J., Lohse D. L., and Dixon J. E.. 1997. A family of putative tumor suppressors is structurally and functionally conserved in humans and yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 29403–29406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tashiro H., Blazes M. S., Wu R., Cho K. R., Bose S., Wang S. I., Li J., Parsons R. and Ellenson L. H.. 1997. Mutations in PTEN are frequent in endometrial carcinoma but rare in other common gynecological malignancies. Cancer Res. 57: 3935–3940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liaw D., Marsh D. J., Li J., Dahia P. L., Wang S. I., Zheng Z., Bose S., Call K. M., Tsou H. C., Peacocke M., et al. 1997. Germline mutations of the PTEN gene in Cowden disease, an inherited breast and thyroid cancer syndrome. Nat. Genet. 16: 64–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nelen M. R., van Staveren W. C., Peeters E. A., Hassel M. B., Gorlin R. J., Hamm H., Lindboe C. F., Fryns J. P., Sijmons R. H., Woods D. G., et al. 1997. Germline mutations in the PTEN/MMAC1 gene in patients with Cowden disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 6: 1383–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Di Cristofano A., Pesce B., Cordon-Cardo C., and Pandolfi P. P.. 1998. Pten is essential for embryonic development and tumour suppression. Nat. Genet. 19: 348–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Podsypanina K., Ellenson L. H., Nemes A., Gu J., Tamura M., Yamada K. M., Cordon-Cardo C., Catoretti G., Fisher P. E., and Parsons R.. 1999. Mutation of Pten/Mmac1 in mice causes neoplasia in multiple organ systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96: 1563–1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Suzuki A., de la Pompa J. L., Stambolic V., Elia A. J., Sasaki T., del Barco Barrantes I., Ho A., Wakeham A., Itie A., Khoo W., et al. 1998. High cancer susceptibility and embryonic lethality associated with mutation of the PTEN tumor suppressor gene in mice. Curr. Biol. 8: 1169–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alonso A., Burkhalter S., Sasin J., Tautz L., Bogetz J., Huynh H., Bremer M. C. D., Holsinger L. J., Godzik A., and Mustelin T.. 2004. The minimal essential core of a cysteine-based protein-tyrosine phosphatase revealed by a novel 16-kDa VH1-like phosphatase, VHZ. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 35768–35774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li D. M., and Sun H.. 1997. TEP1, encoded by a candidate tumor suppressor locus, is a novel protein tyrosine phosphatase regulated by transforming growth factor beta. Cancer Res. 57: 2124–2129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Myers M. P., Stolarov J. P., Eng C., Li J., Wang S. I., Wigler M. H., Parsons R., and Tonks N. K.. 1997. P-TEN, the tumor suppressor from human chromosome 10q23, is a dual-specificity phosphatase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94: 9052–9057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tamura M., Gu J., Matsumoto K., Aota S., Parsons R., and Yamada K. M.. 1998. Inhibition of cell migration, spreading, and focal adhesions by tumor suppressor PTEN. Science. 280: 1614–1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tamura M., Gu J., Takino T., and Yamada K. M.. 1999. Tumor suppressor PTEN inhibition of cell invasion, migration, and growth: differential involvement of focal adhesion kinase and p130Cas. Cancer Res. 59: 442–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maehama T., and Dixon J. E.. 1998. The tumour suppressor, PTEN/MMAC1, dephosphorylates the lipid second messenger, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 13375–13378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Myers M. P., Pass I., Batty I. H., Van der Kaay J., Stolarov J. P., Hemmings B. A., Wigler M. H., Downes C. P., and Tonks N. K.. 1998. The lipid phosphatase activity of PTEN is critical for its tumor supressor function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95: 13513–13518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stambolic V., Suzuki A., de la Pompa J. L., Brothers G. M., Mirtsos C., Sasaki T., Ruland J., Penninger J. M., Siderovski D. P., and Mak T. W.. 1998. Negative regulation of PKB/Akt-dependent cell survival by the tumor suppressor PTEN. Cell. 95: 29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Worby C. A., and Dixon J. E.. 2014. PTEN. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 83: 641–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tibarewal P., Zilidis G., Spinelli L., Schurch N., Maccario H., Gray A., Perera N. M., Davidson L., Barton G. J., and Leslie N. R.. 2012. PTEN protein phosphatase activity correlates with control of gene expression and invasion, a tumor-suppressing phenotype, but not with AKT activity. Sci. Signal. 5: ra18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shi Y., Wang J., Chandarlapaty S., Cross J., Thompson C., Rosen N., and Jiang X.. 2014. PTEN is a protein tyrosine phosphatase for IRS1. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21: 522–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bassi C., Ho J., Srikumar T., Dowling R. J. O., Gorrini C., Miller S. J., Mak T. W., Neel B. G., Raught B., and Stambolic V.. 2013. Nuclear PTEN controls DNA repair and sensitivity to genotoxic stress. Science. 341: 395–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gimm O., Attié-Bitach T., Lees J. A., Vekemans M., and Eng C.. 2000. Expression of the PTEN tumour suppressor protein during human development. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9: 1633–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]