Abstract

Guard cells are specialized cells located at the leaf surface delimiting pores which control gas exchanges between the plant and the atmosphere. To optimize the CO2 uptake necessary for photosynthesis while minimizing water loss, guard cells integrate environmental signals to adjust stomatal aperture. The size of the stomatal pore is regulated by movements of the guard cells driven by variations in their volume and turgor. As guard cells perceive and transduce a wide array of environmental cues, they provide an ideal system to elucidate early events of plant signaling. Reversible protein phosphorylation events are known to play a crucial role in the regulation of stomatal movements. However, in some cases, phosphorylation alone is not sufficient to achieve complete protein regulation, but is necessary to mediate the binding of interactors that modulate protein function. Among the phosphopeptide-binding proteins, the 14-3-3 proteins are the best characterized in plants. The 14-3-3s are found as multiple isoforms in eukaryotes and have been shown to be involved in the regulation of stomatal movements. In this review, we describe the current knowledge about 14-3-3 roles in the regulation of their binding partners in guard cells: receptors, ion pumps, channels, protein kinases, and some of their substrates. Regulation of these targets by 14-3-3 proteins is discussed and related to their function in guard cells during stomatal movements in response to abiotic or biotic stresses.

Keywords: 14-3-3 proteins, guard cell, H+-ATPases, ion channels, phototropins, protein kinases, protein phosphorylation, signal transduction

Introduction

Reversible protein phosphorylation is recognized as one of the most important post-translational modifications in eukaryotes, playing major roles in the regulation of cellular processes (Cohen, 2002). However, in many cases, phosphorylation alone is not sufficient to achieve complete protein regulation, but is required to induce the binding of interactors that modulate protein function. Among the phosphopeptide-binding proteins, the 14-3-3 proteins are the best characterized in plants (Chevalier et al., 2009). The 14-3-3s form a family of highly conserved proteins found in all eukaryotes that bind to phosphoserine/phosphothreonine-containing motifs. 14-3-3 proteins have been found to be expressed in all eukaryotic organisms, in which they generally exist as multiple isoforms. While yeast expresses two 14-3-3 isoforms and mammals possess seven, plants have a varying number of isoforms, with e.g., thirteen identified in Arabidopsis and eight in rice (Van Heusden et al., 1995; DeLille et al., 2001; Aitken, 2006; Yao et al., 2007). Arabidopsis 14-3-3 proteins are designated by Greek letters (χ, ω, ѱ, φ, υ, λ, ν, κ, μ, ε, о, ι, π) and are encoded by genes called General Regulatory Factors (GRF1-13) (Ferl et al., 2002; Chevalier et al., 2009). Both of these designations are currently used for Arabidopsis 14-3-3s in the literature. The 14-3-3s are small acidic proteins (∼30 kDa) that are highly conserved both within and across species (Ferl et al., 2002). These proteins form homo- and heterodimers (Paul et al., 2012) that bind, in most cases, to phosphorylated target proteins. To date, three consensus 14-3-3-binding phosphopeptide motifs have been described: mode I (R/K)XX(pS/pT)XP, mode II (R/K)XXX(pS/pT)XP (Muslin et al., 1996; Yaffe et al., 1997) and C-terminal mode III (pS/pT)X1-2-COOH (Coblitz et al., 2005; Ganguly et al., 2005), where X is any amino acid and pS/pT represents a phosphoserine or phosphothreonine. However, many phosphorylated target proteins contain 14-3-3-binding sites that do not conform to these consensus motifs and 14-3-3-binding can also occur through non-phosphorylated sequences (Bridges and Moorhead, 2005; Taoka et al., 2011). Through these interactions, 14-3-3s regulate target activity, subcellular localization, proteolysis, or association with other proteins (Cotelle et al., 2000; Taoka et al., 2011; Paul et al., 2012). Plant 14-3-3s interact with a wide range of proteins, thereby playing prominent role in diverse aspects of plant physiology, including primary metabolism, development, abiotic and biotic stress responses, and regulation of stomatal movements (reviewed in Denison et al., 2011; Jaspert et al., 2011; de Boer et al., 2013; Lozano-Durán and Robatzek, 2015).

In plants, the majority of water loss occurs through pores on the leaf surface, which are called stomata. The size of the stomatal pores is variable and controls the rate of diffusion of water vapor out of the plant. In addition to controlling water loss, stomata allow CO2 to diffuse into the leaf for photosynthesis. Thus, the primary role of stomata is to optimize the exchange of CO2 and water vapor between the intracellular spaces in leaves and the atmosphere according to environmental conditions. Under favorable conditions, stomatal opening requires activation of plasma membrane H+-ATPases, resulting in plasma membrane hyperpolarization (Assmann et al., 1985; Shimazaki et al., 1986) to drive K+ uptake into guard cells via inward-rectifying K+ channels (Schroeder et al., 1984), including K+ channels Arabidopsis thaliana 1 and 2 (KAT1, KAT2), Arabidopsis K+ transporter 1 and 2 (AKT1, AKT2) and K+ rectifying channel (KC1) (Schachtman et al., 1992; Nakamura et al., 1995; Pilot et al., 2001; Szyroki et al., 2001). Uptake of K+ ions, in combination with the accumulation of anions, increases the osmotic potential of the guard cells resulting in guard cell swelling, driving opening of the stomatal pore. In contrast, stomatal closure is triggered by transition from light to darkness, high CO2 concentrations and abscisic acid (ABA), a hormone synthesized in response to drought stress. All these signals have been shown to induce an alkalinisation of the apoplastic space, which is correlated with the concomitant decrease of the plasma membrane H+-ATPase activity (Hedrich et al., 2001; Jia and Davies, 2006). Moreover, the activation of rapid-type (R-type) anion channels, the aluminum-activated anion channel 12 (ALMT12), and slow-type (S-type) anion channels including slow anion channel-associated 1 (SLAC1) and SLAC1 homolog 3 (SLAH3), facilitate the efflux of anions such as malate2-, Cl-, and NO3- (Schroeder and Hagiwara, 1989; Hedrich et al., 1990; Roelfsema et al., 2004; Negi et al., 2008; Vahisalu et al., 2008; Meyer et al., 2010; Sasaki et al., 2010; Geiger et al., 2011). An elevation of cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration due to the activation of plasma membrane and vacuolar channels is also observed during stomatal closure (Schroeder and Hagiwara, 1989; Ward and Schroeder, 1994). Altogether, inhibition of H+-ATPases, activation of anion and Ca2+ channels induce plasma membrane depolarization. This plasma membrane depolarization activates guard cell outward-rectifying K+ (GORK; Hosy et al., 2003). The efflux of solutes from the guard cells leads to a reduced turgor and stomatal closure.

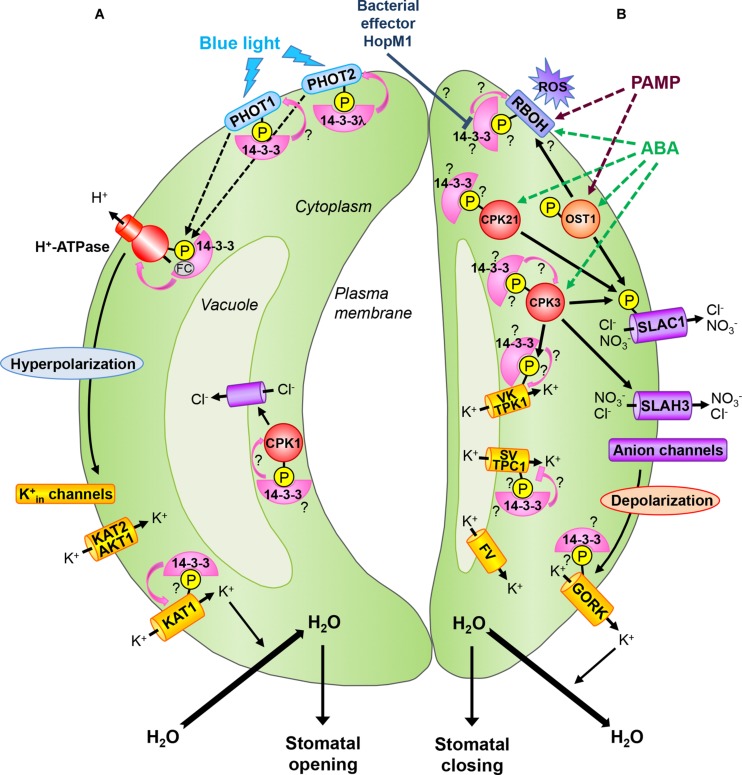

In the past decades, guard cell research has revealed many new signal transduction components including channels mediating movement of ions. However, mechanisms by which the environmental cues are transduced to activate or deactivate the channels are still not completely understood. Using several approaches including genetics and biochemistry, the key role of protein phosphorylation involving binding of 14-3-3 proteins has been demonstrated in guard cell signal transduction. Moreover, several studies report expression of 14-3-3 isoforms in guard cells (Table 1). In this mini-review, we highlight the functions of 14-3-3 proteins in guard cell signaling, which are summarized in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Expression and subcellular localization of Arabidopsis thaliana 14-3-3 proteins.

nd: not determined.

1Reference related to gene expression.

2Reference related to protein localization.

FIGURE 1.

14-3-3 proteins during stomatal movements. (A) Stomatal opening: the perception of blue light by phototropins PHOT1 and PHOT2 leads to their autophosphorylation and subsequent 14-3-3 binding. In Arabidopsis, the 14-3-3λ isoform is required for PHOT2-mediated stomatal opening. Blue light stimulates the plasma membrane H+-ATPase by phosphorylation at its C-terminus end and subsequent 14-3-3 binding. The fungal toxin FC stabilizes the 14-3-3/H+-ATPase interaction leading to constant activation of the proton pump and thus irreversible stomatal opening. Activation of H+-ATPases leads to hyperpolarization of the plasma membrane and uptake of K+ via inward-rectifying K+ channels (Kin) including K+ channel A. thaliana 1 and 2 (KAT1, KAT2) and Arabidopsis K+ transporter 1 (AKT1). KAT1 is activated by 14-3-3 binding. K+ influx induces inward water movement leading to guard cell swelling and stomatal opening. At the tonoplast, a Cl- channel providing a pathway for anion uptake into the vacuole is activated by the calcium-dependent protein kinase (CPK) CPK1, whose activity might be directly stimulated by 14-3-3s. (B) Stomatal closing: ABA induces activation of protein kinase open stomata 1 (OST1) as well as CPKs. Among the CPKs involved in guard cell ABA signaling, CPK21 could bind to 14-3-3 proteins and CPK3 might be stabilized by its interaction with 14-3-3s. OST1 and CPKs can activate the guard cell plasma membrane S-type anion channel SLAC1 (slow anion channel-associated 1) by phosphorylation. SLAC1 homolog 3 (SLAH3), another guard cell S-type anion channel, is also activated by CPK3. Activation of anion channels leads to plasma membrane depolarization and activation of the guard cell outward-rectifying K+ (GORK) channel which is a putative 14-3-3 client protein. The efflux of ions leads to water loss and guard cell shrinkage, thus closure of the stomatal pore. During stomatal closure, K+ release from vacuoles occurs via vacuolar K+-selective (VK) channels, slow vacuolar (SV) channels and fast vacuolar (FV) channels. The tandem-pore K+ channel 1 (TPK1) represents the guard cell VK channel which might be activated by 14-3-3 binding to a N-terminal site phosphorylated by CPK3. In contrast, SV channels, represented by the two-pore channel 1 (TPC1) in Arabidopsis, might be inactivated by 14-3-3 binding. Stomatal closure induced by pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or ABA involves plasma membrane respiratory burst oxidase homologs (RBOHs) which are targets of OST1. RBOHs are NADPH oxidases producing reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the apoplast and might be activated by interaction with 14-3-3 proteins. The Pseudomonas syringae effector HopM1 could suppress PAMP-triggered ROS production and stomatal closure by destabilization of 14-3-3 proteins. Pink lines show 14-3-3 regulation on target proteins. Arrowheads designate activation, bars indicate inhibition. Dashed lines denote more than one step, solid lines show direct interaction. Question marks denote signaling events that require further investigation in guard cells. The P in the yellow-colored disks indicates a phosphorylated protein. See the text for details.

Regulation of Membrane Proteins By 14-3-3 Proteins in Guard Cells

Phototropins and H+-ATPases in Response to Blue Light

Light stimulates stomatal opening via two signaling pathways. One depends specifically on blue light and is perceived by two phototropins, PHOT1 and PHOT2 and cryptochromes, while the other is stimulated by photosynthetically active radiations (Kinoshita et al., 2001; Shimazaki et al., 2007). Phototropins are serine/threonine protein kinases with two LOV (light, oxygen and voltage) domains (Briggs and Christie, 2002). The activated phototropins undergo autophosphorylation and bind 14-3-3 proteins, and ultimately activate the plasma membrane H+-ATPase in guard cells (Kinoshita et al., 2001, 2003; Ueno et al., 2005). It is still unknown whether phototropin excitation induces direct phosphorylation of the H+-ATPase via a direct association of the two proteins, or whether there are one or more signaling cascade elements. In Vicia faba and A. thaliana guard cells, blue light has been shown to induce phosphorylation-dependent binding of a non-epsilon 14-3-3 to PHOT1 (Kinoshita et al., 2003; Ueno et al., 2005). Using yeast two-hybrid and in vitro assays, PHOT1 was found to interact with 14-3-3λ with the strongest affinity followed by 14-3-3κ, 14-3-3φ, and 14-3-3υ (Sullivan et al., 2009). However, characterization of Arabidopsis mutants lacking both 14-3-3λ and 14-3-3κ has been unsuccessful in identifying a physiological role for 14-3-3-binding to PHOT1 (Sullivan et al., 2009). More recently, Tseng et al. (2012) demonstrate that 14-3-3λ interacts also with PHOT2 and plays a role in PHOT2-mediated blue light response. This interaction is dramatically reduced when the PHOT2 S747 in a putative mode I 14-3-3 recognition site was replaced by a non phosphorylatable residue. In addition, blue light-induced stomatal opening is dramatically impaired in phot1-5 14-3-3λ Arabidopsis double mutant. In contrast, phot2-1 14-3-3λ double mutant and phot1-5 14-3-3κ double mutant do not exhibit defects in stomatal opening in response to blue light. Altogether, these observations demonstrate that the closely related 14-3-3 isoforms λ and κ differentially affect PHOT2 signaling in guard cell and reveal the existence of remarkable functional specificity of 14-3-3 proteins.

Furthermore, blue light activates the plasma membrane H+-ATPase (Shimazaki et al., 1986; Kinoshita and Shimazaki, 1999; Hayashi et al., 2011). The pump activation requires the phosphorylation of its penultimate threonine residue at the C-terminus end. However, this phosphorylation alone is not enough to activate H+ pumping, as subsequent binding of 14-3-3 proteins is also needed (Palmgren, 2001; Bækgaard et al., 2005). In Vicia faba guard cells, a 32 kDa 14-3-3 protein has been shown to bind to the phosphorylated C-terminus of the H+-ATPase, but not to the non phosphorylated one (Emi et al., 2001; Kinoshita and Shimazaki, 2001). Moreover, blue light increases the amount of bound 14-3-3 protein which is proportional to H+-ATPase activity (Kinoshita and Shimazaki, 2002). The binding of 14-3-3 proteins to the autoinhibitory C-terminal domain of the H+-ATPase prevents its interaction with the catalytic domain leading to a high-activity state of the pump. The H+-ATPase/14-3-3 complex is stabilized by fusicoccin (FC), a fungal phytotoxin (Palmgren, 2001). FC binds to 14-3-3 proteins, thereby increasing the affinity of 14-3-3 proteins for the autoinhibitory C-terminal end of the plasma membrane H+-ATPase, which causes irreversible opening of stomata (Assmann and Schwartz, 1992; Kinoshita and Shimazaki, 2001). Interestingly, Pallucca et al. (2014) show that H+-ATPase preferentially interacts with non-ε 14-3-3 isoforms. However, further studies will be needed to identify which 14-3-3 isoforms interact with guard cell-expressed proton pumps. Finally, overexpression of 14-3-3λ in cotton results in an increase in stomatal conductance suggesting that 14-3-3λ may interact with the plasma membrane H+-ATPase or phototropins to regulate stomatal movements (Yan et al., 2004).

Ion Channels at the Plasma Membrane

Plasma membrane K+ channels play a major role in K+ fluxes that modulate guard cell turgor. The main plasma membrane K+ channels identified in guard cell are from shaker superfamily (Véry et al., 2014). In Arabidopsis guard cells, the expression of six shaker-type K+ channels can be detected including KAT1, KAT2, AKT1, AKT2, GORK, and KC1 (Schachtman et al., 1992; Nakamura et al., 1995; Pilot et al., 2001; Szyroki et al., 2001). KAT1, the first cloned plant K+ channel, was demonstrated to be endowed with functional properties compatible with a role in mediating K+ influx (Schachtman et al., 1992). KAT1 is the main inward-rectifying K+ channel in guard cell since its disruption leads to more than 50% reduction of the inward K+ currents in Arabidopsis guard cell (Szyroki et al., 2001). Moreover, dominant negative repressive mutants of KAT1 and KAT2 suppress light- and low-CO2-induced stomatal opening (Kwak et al., 2001; Lebaudy et al., 2008). These data provide genetic evidences demonstrating the important role of inward K+ channels for stomatal opening. Other mechanisms are also involved in the regulation of these channel activities. Notably, KAT1 is sensitive to internal and external pH (Blatt, 1992; Hoth et al., 2001). Cytosolic 14-3-3 proteins also regulate KAT1 activity. The binding of the maize GF14-6 isoform to KAT1 enhances channel activity by increasing channel open probability and also by controlling the number of channels at the plasma membrane (Sottocornola et al., 2006, 2008).

In contrast to inward K+ channels, only one outward rectifying K+ channel, GORK, is expressed in Arabidopsis guard cell. GORK disruption completely abolishes outward K+ channel currents in guard cells and impairs dark- and ABA-induced stomatal closure (Hosy et al., 2003). GORK currents are regulated by external K+ concentration and also by internal and external pH (Blatt, 1992; Ache et al., 2000). Interestingly, by mass spectrometry-based proteomic analysis of tag affinity-purified 14-3-3ω complexes, GORK was identified as a putative 14-3-3 client (Chang et al., 2009). However, further studies will be required to determine the physiological function of GORK regulation by 14-3-3s in guard cells.

Vacuolar Ion Channels

During stomatal closure, K+ release from vacuoles into the cytosol occurs via channels. Three cation channel activities have been characterized in guard cell tonoplast: fast vacuolar (FV) channels, vacuolar K+-selective (VK) channels, and slow vacuolar (SV) channels (Pandey et al., 2007). FV channels are instantaneously activated in response to voltage and inhibited by cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations ([Ca2+]cyt) (Hedrich and Neher, 1987; Allen and Sanders, 1996). However, the molecular identity of these channels still remains unknown. VK channels are voltage-independent, K+-selective, and activated by increases in [Ca2+]cyt (Ward and Schroeder, 1994; Allen and Sanders, 1996). In Arabidopsis, the voltage-independent K+-channels of the TPK/KCO family consists of five “tandem-pore” channels (TPK1-TPK5) and one Kir-like channel (KCO3) (Voelker et al., 2010). Except for TPK4, these channels are located in the tonoplast and contain 14-3-3-binding sites and Ca2+-binding EF-hands in their N- and C-termini, respectively (Voelker et al., 2006). Their conserved 14-3-3-binding site conforms to the consensus mode I binding motif with a serine or threonine residue as potential phosphorylation site (Latz et al., 2007). Using this phosphorylated conserved motif in surface plasmon resonance (SPR) experiments, it was demonstrated that HvKCO1/HvTPK1, a barley homologue of Arabidopsis TPK1, interacts with three out of the five barley 14-3-3 isoforms (Sinnige et al., 2005). Moreover, Arabidopsis TPKs (TPK1, 3 and 5) also bind to 14-3-3s both in vitro and in vivo (Latz et al., 2007; Voelker et al., 2010; Shin et al., 2011). Phosphorylation of the 14-3-3-binding motif in TPK1 and TPK5 appears to be a prerequisite for their interaction with 14-3-3s. Indeed, in yeast two-hybrid assays, mutating serine or threonine residue to alanine in the 14-3-3-binding sites (TPK1 : S42A; TPK5 : T83A) abolishes the interactions between channel N-terminal segments and 14-3-3s (Voelker et al., 2010). In plant cells, TPK1, but not the TPK1-S42A mutant, co-localizes with 14-3-3λ at the tonoplast (Latz et al., 2007). In the same study, pull-down assays and surface plasmon resonance measurements show high affinity interaction of 14-3-3λ with phosphorylated TPK1. After TPK1 expression in yeast and isolation of vacuoles, 14-3-3λ when applied to the cytosolic side of the membrane, strongly increases TPK1 currents in patch-clamp experiments. TPK1 channel activity in yeast exihibits all the hallmarks of the VK channel, i.e., K+ selectivity, activation by cytosolic Ca2+, and voltage independence (Bihler et al., 2005; Latz et al., 2007). Furthermore, instantaneous VK channel currents are absent in tpk1 knockout mutants (Gobert et al., 2007). Based on these results, it is assumed that TPK1 represents the VK channel characterized in guard cells (Ward and Schroeder, 1994; Allen and Sanders, 1996). In accordance, TPK1 loss-of-function mutants display slower ABA-induced stomatal closure, thus providing evidence that VK channels can mediate vacuolar K+ efflux for stomatal closing (Gobert et al., 2007). SV channels are cation permeable, voltage-regulated and slowly activated at elevated [Ca2+]cyt (Hedrich and Neher, 1987; Ward and Schroeder, 1994; Allen and Sanders, 1996). The SV channels are ubiquitous in plants and encoded by the single TPC1 (two-pore channel 1) gene in Arabidopsis (Peiter et al., 2005; Ranf et al., 2008). In tpc1 knockout mutants, inhibition of stomatal opening by extracellular Ca2+ is impaired, whereas ABA-promoted stomatal closure is not affected (Peiter et al., 2005). Besides Ca2+, SV channels have also been reported to be regulated by 14-3-3 proteins. Indeed, in mesophyll cell vacuoles, the barley SV channel is strongly inhibited by the barley 14-3-3B isoform and 14-3-3λ suppresses SV channel currents in Arabidopsis (Van den Wijngaard et al., 2001; Latz et al., 2007). Interestingly, TPC1 has the C-terminal sequence STSDT, which is a potential 14-3-3 type III binding site (Furuichi et al., 2001). However, although SV and VK channels have been both shown to be regulated by 14-3-3 proteins, further studies are required to address the physiological role of these regulations in stomatal movements.

Regulation of Protein Kinases and Their Subtrates by 14-3-3 Proteins in Guard Cells

Protein phosphorylation plays key roles in regulation of stomatal movements (Zhang et al., 2014). Among the kinases involved in guard cell signaling, calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs) can act as Ca2+ sensors able to translate Ca2+ transients into specific phosphorylation events (Boudsocq and Sheen, 2013; Liese and Romeis, 2013). In Arabidopsis, the CDPK gene family encompasses 34 members (Cheng et al., 2002). Two Arabidopsis CDPK isoforms (also named CPKs), CPK1 and CPK3, regulate ion channels in guard cells and have been identified as 14-3-3 targets. Indeed, three Arabidopsis 14-3-3 isoforms, ω, ψ, and φ, stimulate autophosphorylated CPK1 in vitro by direct binding and CPK1 interacts with endogenous 14-3-3ω (Camoni et al., 1998; Chang et al., 2009). In guard cells, CPK1 activates a vacuolar Cl- channel which may provide a pathway for anion uptake into the vacuole required for stomatal opening (Pei et al., 1996). Recently, CPK3, previously identified as a 14-3-3-binding protein in vitro (Moorhead et al., 1999; Cotelle et al., 2000), was found associated with 14-3-3 proteins in Arabidopsis (Lachaud et al., 2013). CPK3 is not activated in vitro by 14-3-3 proteins (Moorhead et al., 1999), but its interaction with 14-3-3s protects CPK3 from proteolysis (Cotelle et al., 2000; Lachaud et al., 2013). CPK3 directly interacts with the VK channel TPK1 (see above) at the tonoplast and is able to phosphorylate the 14-3-3-binding motif (S42) in the N-terminus of TPK1 (Latz et al., 2013). Moreover, CPK3 does not only phosphorylate sites mediating 14-3-3 binding and interact with 14-3-3s, but this kinase is also able to phosphorylate 14-3-3 proteins themselves, suggesting a cross-regulation between CPK3 and 14-3-3s (Lachaud et al., 2013; Swatek et al., 2014). CPK3 interaction with 14-3-3 proteins has not been described in guard cells, but CPK3 is one of the CDPKs involved in the activation of anion channels at the plasma membrane of guard cells, which is a critical step in stomatal closure (Mori et al., 2006; Geiger et al., 2010, 2011; Brandt et al., 2012; Scherzer et al., 2012; Brandt et al., 2015). Guard cells of double cpk3 cpk6 knockout mutants show impaired ABA and Ca2+ activation of S-type anion channels, and ABA- and Ca2+-induced stomatal closing are also partially inhibited in these mutants (Mori et al., 2006). Furthermore, CPK3 and CPK6 activate guard cell slow anion channels SLAC1 and SLAH3 in Xenopus oocytes, and are able to phosphorylate SLAC1 in vitro (Brandt et al., 2012; Scherzer et al., 2012). Interestingly, SLAC1 is also activated by CPK21 (Geiger et al., 2010) whose closest homologue in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), NtCDPK1, is a 14-3-3-binding protein. NtCDPK1 acts as a scaffold transferring 14-3-3 to its substrate, the transcription factor REPRESSION OF SHOOT GROWTH (RSG) after its phosphorylation, thus promoting RSG interaction with 14-3-3 proteins which negatively regulate RSG by sequestering it in the cytoplasm (Ito et al., 2014).

Besides CDPKs, the Ca2+-independent protein kinase OST1 (open stomata 1), which plays a central role in stomatal closure (Kollist et al., 2014), could also mediate 14-3-3 binding to partners in guard cells. Indeed, targets of Arabidopsis OST1 include KAT1 (Sato et al., 2009), the bZIP transcription factor ABA-responsive-element binding factor 3 (ABF3) (Sirichandra et al., 2010) and plasma membrane respiratory burst oxidase homologs (RBOHs) (Sirichandra et al., 2009; Acharya et al., 2013). RBOHs are NADPH oxidases generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) which are important secondary messengers in stomatal closure induced by ABA or pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) (Kwak et al., 2003; Mersmann et al., 2010; Macho et al., 2012). The tobacco 14-3-3 isoform Nt14-3-3h binds the C-terminus of the tobacco NADPH oxidase NtrbohD in yeast (Elmayan et al., 2007) and it has been speculated that the Pseudomonas syringae effector HopM1, which significantly contributes to bacterial pathogenesis, suppresses PAMP-triggered ROS production and stomatal closure through degradation of 14-3-3κ in Arabidopsis (Lozano-Durán et al., 2014). Moreover, in Vicia faba, an ortholog of OST1, AAPK (ABA-activated protein kinase), is able to phosphorylate a 61 kDa protein whose binding to a 14-3-3 protein is induced by ABA in guard cells (Takahashi et al., 2007).

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Although many indirect indications point out that 14-3-3 proteins play important roles in stomatal movements, regulation of target proteins by 14-3-3s has been characterized in only a few cases in guard cells, as described in this mini-review. Therefore, many questions remain to be addressed in guard cells. What is the extent of the 14-3-3 interactome? What is the functional consequence of 14-3-3 binding to targets and how are these interactions regulated? What is the specificity of 14-3-3 isoforms towards their targets and in the regulation of stomatal movements? Combining protein biochemistry, cell biology and genetics approaches, future work addressing these questions will further our knowledge with regard to the role of 14-3-3 proteins in guard cell signaling.

Author Contributions

VC and NL contributed equally to the writing and editing of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

VC is thankful to the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, the Université de Toulouse and the French Laboratory of Excellence project “TULIP” (ANR-10-LABX-41; ANR-11-IDEX-0002-02) for supporting her research work. Research from NL was supported by ANR-JC09_439044.

References

- Acharya B. R., Jeon B. W., Zhang W., Assmann S. M. (2013). Open Stomata 1 (OST1) is limiting in abscisic acid responses of Arabidopsis guard cells. New Phytol. 200 1049–1063. 10.1111/nph.12469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ache P., Becker D., Ivashikina N., Dietrich P., Roelfsema M. R. G., Hedrich R. (2000). GORK, a delayed outward rectifier expressed in guard cells of Arabidopsis thaliana, is a K+-selective, K+-sensing ion channel. FEBS Lett. 486 93–98. 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)02248-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitken A. (2006). 14-3-3 proteins: a historic overview. Semin. Cancer Biol. 16 162–172. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen G. J., Sanders D. (1996). Control of ionic currents in guard cell vacuoles by cytosolic and luminal calcium. Plant J. 10 1055–1069. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1996.10061055.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assmann S. M., Schwartz A. (1992). Synergistic effect of light and fusicoccin on stomatal opening. Plant Physiol. 98 1349–1355. 10.1104/pp.98.4.1349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assmann S. M., Simoncini L., Schroeder J. I. (1985). Blue light activates electrogenic ion pumping in guard cell protoplasts of Vicia faba. Nature 318 285–287. 10.1038/318285a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bihler H., Eing C., Hebeisen S., Roller A., Czempinski K., Bertl A. (2005). TPK1 is a vacuolar ion channel different from the slow-vacuolar cation channel. Plant Physiol. 139 417–424. 10.1104/pp.105.065599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt M. R. (1992). K+ channels of stomatal guard cells. Characteristics of the inward rectifier and its control by pH. J. Gen. Physiol. 99 615–644. 10.1085/jgp.99.4.615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudsocq M., Sheen J. (2013). CDPKs in immune and stress signaling. Trends Plant Sci. 18 30–40. 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt B., Brodsky D. E., Xue S., Negi J., Iba K., Kangasjarvi J., et al. (2012). Reconstitution of abscisic acid activation of SLAC1 anion channel by CPK6 and OST1 kinases and branched ABI1 PP2C phosphatase action. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 10593–10598. 10.1073/pnas.1116590109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt B., Munemasa S., Wang C., Nguyen D., Yong T., Yang P. G., et al. (2015). Calcium specificity signaling mechanisms in abscisic acid signal transduction in Arabidopsis guard cells. Elife 4 1–25. 10.7554/eLife.03599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges D., Moorhead G. B. G. (2005). 14-3-3 proteins: a number of functions for a numbered protein. Sci. STKE 2005 re10. 10.1126/stke.2962005re10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs W. R., Christie J. M. (2002). Phototropins 1 and 2: versatile plant blue-light receptors. Trends Plant Sci. 7 204–210. 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02245-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bækgaard L., Fuglsang A. T., Palmgren M. G. (2005). Regulation of plant plasma membrane H+- and Ca2+-ATPases by terminal domains. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 37 369–374. 10.1007/s10863-005-9473-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camoni L., Harper J. F., Palmgren M. G. (1998). 14-3-3 proteins activate a plant calcium-dependent protein kinase (CDPK). FEBS Lett. 430 381–384. 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00696-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco J. L., Castelló M. J., Naumann K., Lassowskat I., Navarrete-Gómez M., Scheel D., et al. (2014). Arabidopsis protein phosphatase DBP1 nucleates a protein network with a role in regulating plant defense. PLoS ONE 9:e90734 10.1371/journal.pone.0090734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalá R., López-Cobollo R., Mar Castellano M., Angosto T., Alonso J. M., Ecker J. R., et al. (2014). The Arabidopsis 14-3-3 protein RARE COLD INDUCIBLE 1A links low-temperature response and ethylene biosynthesis to regulate freezing tolerance and cold acclimation. Plant Cell 26 3326–3342. 10.1105/tpc.114.127605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang I.-F., Curran A., Woolsey R., Quilici D., Cushman J. C., Mittler R., et al. (2009). Proteomic profiling of tandem affinity purified 14-3-3 protein complexes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proteomics 9 2967–2985. 10.1002/pmic.200800445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S.-H., Willmann M. R., Chen H.-C., Sheen J. (2002). Calcium signaling through protein kinases. The Arabidopsis calcium-dependent protein kinase gene family. Plant Physiol. 129 469–485. 10.1104/pp.005645.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier D., Morris E. R., Walker J. C. (2009). 14-3-3 and FHA domains mediate phosphoprotein interactions. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 60 67–91. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coblitz B., Shikano S., Wu M., Gabelli S. B., Cockrell L. M., Spieker M., et al. (2005). C-terminal recognition by 14-3-3 proteins for surface expression of membrane receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 280 36263–36272. 10.1074/jbc.M507559200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P. (2002). The origins of protein phosphorylation. Nat. Cell Biol. 4 E127–E130. 10.1038/ncb0502-e127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotelle V., Meek S. E., Provan F., Milne F. C., Morrice N., MacKintosh C. (2000). 14-3-3s regulate global cleavage of their diverse binding partners in sugar-starved Arabidopsis cells. EMBO J. 19 2869–2876. 10.1093/emboj/19.12.2869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler S. R., Ehrhardt D. W., Griffitts J. S., Somerville C. R. (2000). Random GFP::cDNA fusions enable visualization of subcellular structures in cells of Arabidopsis at a high frequency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 3718–3723. 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugherty C. J., Rooney M. F., Miller P. W., Ferl R. J. (1996). Molecular organization and tissue-specific expression of an Arabidopsis 14-3-3 gene. Plant Cell 8 1239–1248. 10.1105/tpc.8.8.1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer A. H., van Kleeff P. J. M., Gao J. (2013). Plant 14-3-3 proteins as spiders in a web of phosphorylation. Protoplasma 250 425–440. 10.1007/s00709-012-0437-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLille J. M., Sehnke P. C., Ferl R. J. (2001). The Arabidopsis 14-3-3 family of signaling regulators. Plant Physiol. 126 35–38. 10.1104/pp.126.1.35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denison F. C., Paul A.-L., Zupanska A. K., Ferl R. J. (2011). 14-3-3 proteins in plant physiology. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 22 720–727. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmayan T., Fromentin J., Riondet C., Alcaraz G., Blein J.-P., Simon-Plas F. (2007). Regulation of reactive oxygen species production by a 14-3-3 protein in elicited tobacco cells. Plant. Cell Environ. 30 722–732. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01660.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emi T., Kinoshita T., Shimazaki K. (2001). Specific binding of vf14-3-3a isoform to the plasma membrane H+-ATPase in response to blue light and fusicoccin in guard cells of broad bean. Plant Physiol. 125 1115–1125. 10.1104/pp.125.2.1115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferl R. J., Manak M. S., Reyes M. F. (2002). The 14-3-3s. Genome Biol. 3 REVIEWS3010 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-reviews3010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuichi T., Cunningham K. W., Muto S. (2001). A putative two pore channel AtTPC1 mediates Ca2+ flux in Arabidopsis leaf cells. Plant Cell Physiol. 42 900–905. 10.1093/pcp/pce145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly S., Weller J. L., Ho A., Chemineau P., Malpaux B., Klein D. C. (2005). Melatonin synthesis: 14-3-3-dependent activation and inhibition of arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase mediated by phosphoserine-205. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 1222–1227. 10.1073/pnas.0406871102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger D., Maierhofer T., Al-Rasheid K. A. S., Scherzer S., Mumm P., Liese A., et al. (2011). Stomatal closure by fast abscisic acid signaling is mediated by the guard cell anion channel SLAH3 and the receptor RCAR1. Sci. Signal. 4 ra32 10.1126/scisignal.2001346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger D., Scherzer S., Mumm P., Marten I., Ache P., Matschi S., et al. (2010). Guard cell anion channel SLAC1 is regulated by CDPK protein kinases with distinct Ca2+ affinities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 8023–8028. 10.1073/pnas.0912030107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gepstein S., Sabehi G., Carp M.-J., Hajouj T., Nesher M. F. O., Yariv I., et al. (2003). Large-scale identification of leaf senescence-associated genes. Plant J. 36 629–642. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01908.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobert A., Isayenkov S., Voelker C., Czempinski K., Maathuis F. J. M. (2007). The two-pore channel TPK1 gene encodes the vacuolar K+ conductance and plays a role in K+ homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 10726–10731. 10.1073/pnas.0702595104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajduch M., Hearne L. B., Miernyk J. A., Casteel J. E., Joshi T., Agrawal G. K., et al. (2010). Systems analysis of seed filling in Arabidopsis: using general linear modeling to assess concordance of transcript and protein expression. Plant Physiol. 152 2078–2087. 10.1104/pp.109.152413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi M., Inoue S. I., Takahashi K., Kinoshita T. (2011). Immunohistochemical detection of blue light-induced phosphorylation of the plasma membrane H +-ATPase in stomatal guard cells. Plant Cell Physiol. 52 1238–1248. 10.1093/pcp/pcr072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Wu J., Lv B., Li J., Gao Z., Xu W., et al. (2015). Involvement of 14-3-3 protein GRF9 in root growth and response under polyethylene glycol-induced water stress. J. Exp. Bot. 66 2271–2281. 10.1093/jxb/erv149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrich R., Busch H., Raschke K. (1990). Ca2+ and nucleotide dependent regulation of voltage dependent anion channels in the plasma membrane of guard cells. EMBO J. 9 3889–3892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrich R., Neher E. (1987). Cytoplasmic calcium regulates voltage-dependent ion channels in plant vacuoles. Nature 329 833–836. 10.1038/329833a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrich R., Neimanis S., Savchenko G., Felle H. H., Kaiser W. M., Heber U. (2001). Changes in apoplastic pH and membrane potential in leaves in relation to stomatal responses to CO2, malate, abscisic acid or interruption of water supply. Planta 213 594–601. 10.1007/s004250100524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosy E., Vavasseur A., Mouline K., Dreyer I., Gaymard F., Porée F., et al. (2003). The Arabidopsis outward K+ channel GORK is involved in regulation of stomatal movements and plant transpiration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 5549–5554. 10.1073/pnas.0733970100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoth S., Geiger D., Becker D., Hedrich R. (2001). The pore of plant K+ channels is involved in voltage and pH sensing: domain swapping between different K+ channel alpha-subunits. Plant Cell 13 943–952. 10.1105/tpc.13.4.943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T., Nakata M., Fukazawa J., Ishida S., Takahashi Y. (2014). Scaffold function of Ca2+-dependent protein kinase: tobacco Ca2+-DEPENDENT PROTEIN KINASE1 transfers 14-3-3 to the substrate REPRESSION OF SHOOT GROWTH after phosphorylation. Plant Physiol. 165 1737–1750. 10.1104/pp.114.236448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaspert N., Throm C., Oecking C. (2011). Arabidopsis 14-3-3 proteins: fascinating and less fascinating aspects. Front. Plant Sci. 2:96 10.3389/fpls.2011.00096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia W., Davies W. J. (2006). Modification of leaf apoplastic pH in relation to stomatal sensitivity to root-sourced abscisic acid signals. Plant Physiol. 143 68–77. 10.1104/pp.106.089110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T., Doi M., Suetsugu N., Kagawa T., Wada M., Shimazaki K. (2001). Phot1 and phot2 mediate blue light regulation of stomatal opening. Nature 414 656–660. 10.1038/414656a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T., Emi T., Tominaga M., Sakamoto K., Shigenaga A., Doi M., et al. (2003). Blue-light- and phosphorylation-dependent binding of a 14-3-3 protein to phototropins in stomatal guard cells of broad bean. Plant Physiol. 133 1453–1463. 10.1104/pp.103.029629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T., Shimazaki K. (2002). Biochemical evidence for the requirement of 14-3-3 protein binding in activation of the guard-cell plasma membrane H+-ATPase by blue light. Plant Cell Physiol. 43 1359–1365. 10.1093/pcp/pcf167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T., Shimazaki K. I. (1999). Blue light activates the plasma membrane H+-ATPase by phosphorylation of the C-terminus in stomatal guard cells. EMBO J. 18 5548–5558. 10.1093/emboj/18.20.5548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T., Shimazaki K. I. (2001). Analysis of the phosphorylation level in guard-cell plasma membrane H+-ATPase in response to fusicoccin. Plant Cell Physiol. 42 424–432. 10.1093/pcp/pce055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollist H., Nuhkat M., Roelfsema M. R. G. (2014). Closing gaps: linking elements that control stomatal movement. New Phytol. 203 44–62. 10.1111/nph.12832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koroleva O. A., Tomlinson M. L., Leader D., Shaw P., Doonan J. H. (2005). High-throughput protein localization in Arabidopsis using Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression of GFP-ORF fusions. Plant J. 41 162–174. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02281.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuromori T., Yamamoto M. (2000). Members of the Arabidopsis 14-3-3 gene family trans-complement two types of defects in fission yeast. Plant Sci. 158 155–161. 10.1016/S0168-9452(00)00320-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak J. M., Mori I. C., Pei Z. M., Leonhardt N., Angel Torres M., Dangl J. L., et al. (2003). NADPH oxidase AtrbohD and AtrbohF genes function in ROS-dependent ABA signaling in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 22 2623–2633. 10.1093/emboj/cdg277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak J. M., Murata Y., Baizabal-Aguirre V. M., Merrill J., Wang M., Kemper A., et al. (2001). Dominant negative guard cell K+ channel mutants reduce inward-rectifying K+ currents and light-induced stomatal opening in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 127 473–485. 10.1104/pp.010428.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachaud C., Prigent E., Thuleau P., Grat S., Da Silva D., Brière C., et al. (2013). 14-3-3-Regulated Ca2+-dependent protein kinase CPK3 is required for sphingolipid-induced cell death in Arabidopsis. Cell Death Differ. 20 209–217. 10.1038/cdd.2012.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latz A., Becker D., Hekman M., Müller T., Beyhl D., Marten I., et al. (2007). TPK1, a Ca2+-regulated Arabidopsis vacuole two-pore K+ channel is activated by 14-3-3 proteins. Plant J. 52 449–459. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03255.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latz A., Mehlmer N., Zapf S., Mueller T. D., Wurzinger B., Pfister B., et al. (2013). Salt stress triggers phosphorylation of the Arabidopsis vacuolar K+ channel TPK1 by calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs). Mol. Plant 6 1274–1289. 10.1093/mp/sss158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebaudy A., Vavasseur A., Hosy E., Dreyer I., Leonhardt N., Thibaud J.-B., et al. (2008). Plant adaptation to fluctuating environment and biomass production are strongly dependent on guard cell potassium channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 5271–5276. 10.1073/pnas.0709732105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonhardt N., Kwak J. M. J., Robert N., Waner D., Leonhardt G., Schroeder J. I. (2004). Microarray expression analyses of Arabidopsis guard cells and isolation of a recessive abscisic acid hypersensitive protein phosphatase 2C mutant. Plant Cell 16 596–615. 10.1105/tpc.019000.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liese A., Romeis T. (2013). Biochemical regulation of in vivo function of plant calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPK). Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1833 1582–1589. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano-Durán R., Bourdais G., He S. Y., Robatzek S. (2014). The bacterial effector HopM1 suppresses PAMP-triggered oxidative burst and stomatal immunity. New Phytol. 202 259–269. 10.1111/nph.12651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano-Durán R., Robatzek S. (2015). 14-3-3 proteins in plant-pathogen interactions. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 28 511–518. 10.1094/MPMI-10-14-0322-CR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macho A. P., Boutrot F., Rathjen J. P., Zipfel C. (2012). ASPARTATE OXIDASE plays an important role in Arabidopsis stomatal immunity. Plant Physiol. 159 1845–1856. 10.1104/pp.112.199810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayfield J. D., Folta K. M., Paul A.-L., Ferl R. J. (2007). The 14-3-3 Proteins mu and upsilon influence transition to flowering and early phytochrome response. Plant Physiol. 145 1692–1702. 10.1104/pp.107.108654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mersmann S., Bourdais G., Rietz S., Robatzek S. (2010). Ethylene signaling regulates accumulation of the FLS2 receptor and is required for the oxidative burst contributing to plant immunity. Plant Physiol. 154 391–400. 10.1104/pp.110.154567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer S., Mumm P., Imes D., Endler A., Weder B., Al-Rasheid K. A. S., et al. (2010). AtALMT12 represents an R-type anion channel required for stomatal movement in Arabidopsis guard cells. Plant J. 63 1054–1062. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04302.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorhead G., Douglas P., Cotelle V., Harthill J., Morrice N., Meek S., et al. (1999). Phosphorylation-dependent interactions between enzymes of plant metabolism and 14-3-3 proteins. Plant J. 18 1–12. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00417.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori I. C., Murata Y., Yang Y., Munemasa S., Wang Y.-F., Andreoli S., et al. (2006). CDPKs CPK6 and CPK3 function in ABA regulation of guard cell S-type anion- and Ca2+-permeable channels and stomatal closure. PLoS Biol. 4:e327 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muslin A. J., Tanner J. W., Allen P. M., Shaw A. S. (1996). Interaction of 14-3-3 with signaling proteins is mediated by the recognition of phosphoserine. Cell 84 889–897. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81067-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura R. L., McKendree W. L., Hirsch R. E., Sedbrook J. C., Gaber R. F., Sussman M. R. (1995). Expression of an Arabidopsis potassium channel gene in guard cells. Plant Physiol. 109 371–374. 10.1104/pp.109.2.371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negi J., Matsuda O., Nagasawa T., Oba Y., Takahashi H., Kawai-Yamada M., et al. (2008). CO2 regulator SLAC1 and its homologues are essential for anion homeostasis in plant cells. Nature 452 483–486. 10.1038/nature06720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallucca R., Visconti S., Camoni L., Cesareni G., Melino S., Panni S., et al. (2014). Specificity of ε and non-ε isoforms of Arabidopsis 14-3-3 proteins towards the H+-ATPase and other targets. PLoS ONE 9:e90764 10.1371/journal.pone.0090764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmgren M. G. (2001). Plant plasma membrane H+-ATPases: powerhauses for nutrient uptake. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 52 817–845. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.52.1.817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey S., Zhang W., Assmann S. M. (2007). Roles of ion channels and transporters in guard cell signal transduction. FEBS Lett. 581 2325–2336. 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul A., Sehnke P., Ferl R. (2005). Isoform-specific subcellular localization among 14-3-3 proteins in Arabidopsis seems to be driven by client interactions. Mol. Biol. Cell 16 1735–1743. 10.1091/mbc.E04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul A.-L., Denison F. C., Schultz E. R., Zupanska A. K., Ferl R. J. (2012). 14-3-3 Phosphoprotein interaction networks – does isoform diversity present functional interaction specification? Front. Plant Sci. 3:190 10.3389/fpls.2012.00190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei Z. M., Ward J. M., Harper J. F., Schroeder J. I. (1996). A novel chloride channel in Vicia faba guard cell vacuoles activated by the serine/threonine kinase, CDPK. EMBO J. 15 6564–6574. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiter E., Maathuis F. J., Mills L. N., Knight H., Pelloux J., Hetherington A. M., et al. (2005). The vacuolar Ca2+-activated channel TPC1 regulates germination and stomatal movement. Nature 434 404–408. 10.1038/nature03381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignocchi C., Doonan J. H. (2011). Interaction of a 14-3-3 protein with the plant microtubule-associated protein EDE1. Ann. Bot. 107 1103–1109. 10.1093/aob/mcr050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilot G., Lacombe B., Gaymard F., Chérel I., Boucherez J., Thibaud J. B., et al. (2001). Guard cell inward K+ channel activity in Arabidopsis involves expression of the twin channel subunits KAT1 and KAT2. J. Biol. Chem. 276 3215–3221. 10.1074/jbc.M007303200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajjou L., Lovigny Y., Groot S. P. C., Belghazi M., Job C., Job D. (2008). Proteome-wide characterization of seed aging in Arabidopsis: a comparison between artificial and natural aging protocols. Plant Physiol. 148 620–641. 10.1104/pp.108.123141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranf S., Wünnenberg P., Lee J., Becker D., Dunkel M., Hedrich R., et al. (2008). Loss of the vacuolar cation channel, AtTPC1, does not impair Ca2+ signals induced by abiotic and biotic stresses. Plant J. 53 287–299. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03342.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelfsema M. R. G., Levchenko V., Hedrich R. (2004). ABA depolarizes guard cells in intact plants, through a transient activation of R- and S-type anion channels. Plant J. 37 578–588. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2003.01985.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenquist M., Alsterfjord M., Larsson C., Sommarin M. (2001). Data mining the Arabidopsis genome reveals fifteen 14-3-3 genes. Expression is demonstrated for two out of five novel genes. Plant Physiol. 127 142–149. 10.1104/pp.127.1.142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T., Mori I. C., Furuichi T., Munemasa S., Toyooka K., Matsuoka K., et al. (2010). Closing plant stomata requires a homolog of an aluminum-activated malate transporter. Plant Cell Physiol. 51 354–365. 10.1093/pcp/pcq016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato A., Sato Y., Fukao Y., Fujiwara M., Umezawa T., Shinozaki K., et al. (2009). Threonine at position 306 of the KAT1 potassium channel is essential for channel activity and is a target site for ABA-activated SnRK2/OST1/SnRK2.6 protein kinase. Biochem. J. 424 439–448. 10.1042/BJ20091221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachtman D. P., Schroeder J. I., Lucas W. J., Anderson J. A., Gaber R. F. (1992). Expression of an inward-rectifying potassium channel by the Arabidopsis KAT1 cDNA. Science 258 1654–1658. 10.1126/science.8966547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherzer S., Maierhofer T., Al-Rasheid K. A. S., Geiger D., Hedrich R. (2012). Multiple calcium-dependent kinases modulate ABA-activated guard cell anion channels. Mol. Plant 5 1409–1412. 10.1093/mp/sss084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid M., Davison T. S., Henz S. R., Pape U. J., Demar M., Vingron M., et al. (2005). A gene expression map of Arabidopsis thaliana development. Nat. Genet. 37 501–506. 10.1038/ng1543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder J., Hagiwara S. (1989). Cytosolic calcium regulates ion channels in the plasma membrane of Vicia faba guard cells. Nature 338 427–430. 10.1038/338427a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder J. I., Hedrich R., Fernandez J. M. (1984). Potassium-selective single channels in guard cell protoplasts of Vicia faba. Nature 312 361–362. 10.1038/312361a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sehnke P. C., Henry R., Cline K., Ferl R. J. (2000). Interaction of a plant 14-3-3 protein with the signal peptide of a thylakoid-targeted chloroplast precursor protein and the presence of 14-3-3 isoforms in the chloroplast stroma. Plant Physiol. 122 235–242. 10.1104/pp.122.1.235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimazaki K., Doi M., Assmann S. M., Kinoshita T. (2007). Light regulation of stomatal movement. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 58 219–247. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimazaki K., Iino M., Zeiger E. (1986). Blue light-dependent proton extrusion by guard-cell protoplasts of Vicia faba. Nature 319 324–326. 10.1038/319324a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shin R., Jez J. M., Basra A., Zhang B., Schachtman D. P. (2011). 14-3-3 Proteins fine-tune plant nutrient metabolism. FEBS Lett. 585 143–147. 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinnige M. P., Ten Hoopen P., Van Den Wijngaard P. W. J., Roobeek I., Schoonheim P. J., Mol J. N. M., et al. (2005). The barley two-pore K+-channel HvKCO1 interacts with 14-3-3 proteins in an isoform specific manner. Plant Sci. 169 612–619. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2005.05.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sirichandra C., Davanture M., Turk B. E., Zivy M., Valot B., Leung J., et al. (2010). The Arabidopsis ABA-activated kinase OST1 phosphorylates the bZIP transcription factor ABF3 and creates a 14-3-3 binding site involved in its turnover. PLoS ONE 5:e13935 10.1371/journal.pone.0013935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirichandra C., Gu D., Hu H. C., Davanture M., Lee S., Djaoui M., et al. (2009). Phosphorylation of the Arabidopsis AtrbohF NADPH oxidase by OST1 protein kinase. FEBS Lett. 583 2982–2986. 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.08.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorrell D. A., Marchbank A. M., Chrimes D. A., Dickinson J. R., Rogers H. J., Francis D., et al. (2003). The Arabidopsis 14-3-3 protein, GF14omega, binds to the Schizosaccharomyces pombe Cdc25 phosphatase and rescues checkpoint defects in the rad24- mutant. Planta 218 50–57. 10.1007/s00425-003-1083-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sottocornola B., Gazzarrini S., Olivari C., Romani G., Valbuzzi P., Thiel G., et al. (2008). 14-3-3 proteins regulate the potassium channel KAT1 by dual modes. Plant Biol. 10 231–236. 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2007.00028.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sottocornola B., Visconti S., Orsi S., Gazzarrini S., Giacometti S., Olivari C., et al. (2006). The potassium channel KAT1 is activated by plant and animal 14-3-3 proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 281 35735–35741. 10.1074/jbc.M603361200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan S., Thomson C. E., Kaiserli E., Christie J. M. (2009). Interaction specificity of Arabidopsis 14-3-3 proteins with phototropin receptor kinases. FEBS Lett. 583 2187–2193. 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swatek K. N., Wilson R. S., Ahsan N., Tritz R. L., Thelen J. J. (2014). Multisite phosphorylation of 14-3-3 proteins by calcium-dependent protein kinases. Biochem. J. 459 15–25. 10.1042/BJ20130035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szyroki A., Ivashikina N., Dietrich P., Roelfsema M. R., Ache P., Reintanz B., et al. (2001). KAT1 is not essential for stomatal opening. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 2917–2921. 10.1073/pnas.051616698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y., Kinoshita T., Shimazaki K. I. (2007). Protein phosphorylation and binding of a 14-3-3 protein in Vicia guard cells in response to ABA. Plant Cell Physiol. 48 1182–1191. 10.1093/pcp/pcm093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taoka K., Ohki I., Tsuji H., Furuita K., Hayashi K., Yanase T., et al. (2011). 14-3-3 proteins act as intracellular receptors for rice Hd3a florigen. Nature 476 332–335. 10.1038/nature10272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng T.-S., Whippo C., Hangarter R. P., Briggs W. R. (2012). The role of a 14-3-3 protein in stomatal opening mediated by PHOT2 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24 1114–1126. 10.1105/tpc.111.092130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno K., Kinoshita T., Inoue S., Emi T., Shimazaki K. (2005). Biochemical characterization of plasma membrane H+-ATPase activation in guard cell protoplasts of Arabidopsis thaliana in response to blue light. Plant Cell Physiol. 46 955–963. 10.1093/pcp/pci104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahisalu T., Kollist H., Wang Y.-F., Nishimura N., Chan W.-Y., Valerio G., et al. (2008). SLAC1 is required for plant guard cell S-type anion channel function in stomatal signalling. Nature 452 487–491. 10.1038/nature06608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Wijngaard P. W. J., Bunney T. D., Roobeek I., Schönknecht G., De Boer A. H. (2001). Slow vacuolar channels from barley mesophyll cells are regulated by 14-3-3 proteins. FEBS Lett. 488 100–104. 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)02394-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Heusden G. P. H., Griffiths D. J. F., Ford J. C., Chin-A-Woeng T. F. C., Schrader P. A. T., Carr A. M., et al. (1995). The 14-3-3 proteins encoded by the BMH1 and BMH2 genes are essential in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae and can be replaced by a plant homologue. Eur. J. Biochem. 229 45–53. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.0045l.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kleeff P. J. M., Jaspert N., Li K. W., Rauch S., Oecking C., de Boer A. H. (2014). Higher order Arabidopsis 14-3-3 mutants show 14-3-3 involvement in primary root growth both under control and abiotic stress conditions. J. Exp. Bot. 65 5877–5888. 10.1093/jxb/eru338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Véry A.-A., Nieves-Cordones M., Daly M., Khan I., Fizames C., Sentenac H. (2014). Molecular biology of K+ transport across the plant cell membrane: what do we learn from comparison between plant species? J. Plant Physiol. 171 748–769. 10.1016/j.jplph.2014.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voelker C., Gomez-Porras J. L., Becker D., Hamamoto S., Uozumi N., Gambale F., et al. (2010). Roles of tandem-pore K+ channels in plants – a puzzle still to be solved. Plant Biol. 12 56–63. 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2010.00353.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voelker C., Schmidt D., Mueller-Roeber B., Czempinski K. (2006). Members of the Arabidopsis AtTPK/KCO family form homomeric vacuolar channels in planta. Plant J. 48 296–306. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02868.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B. C., Wang H. X., Feng J. X., Meng D. Z., Qu L. J., Zhu Y. X. (2006). Post-translational modifications, but not transcriptional regulation, of major chloroplast RNA-binding proteins are related to Arabidopsis seedling development. Proteomics 6 2555–2563. 10.1002/pmic.200500657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Zhang W.-Z., Song L.-F., Zou J.-J., Su Z., Wu W.-H. (2008). Transcriptome analyses show changes in gene expression to accompany pollen germination and tube growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 148 1201–1211. 10.1104/pp.108.126375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward J. M., Schroeder J. I. (1994). Calcium-activated K+ channels and calcium-induced calcium release by slow vacuolar ion channels in guard cell vacuoles implicated in the control of stomatal closure. Plant Cell 6 669–683. 10.1105/tpc.6.5.669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won S.-K., Lee Y.-J., Lee H.-Y., Heo Y.-K., Cho M., Cho H.-T. (2009). Cis-element- and transcriptome-based screening of root hair-specific genes and their functional characterization in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 150 1459–1473. 10.1104/pp.109.140905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe M. B., Rittinger K., Volinia S., Caron P. R., Aitken A., Leffers H., et al. (1997). The structural basis for 14-3-3:phosphopeptide binding specificity. Cell 91 961–971. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80487-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J., He C., Wang J., Mao Z., Holaday S. A., Allen R. D., et al. (2004). Overexpression of the Arabidopsis 14-3-3 protein GF14 lambda in cotton leads to a “stay-green” phenotype and improves stress tolerance under moderate drought conditions. Plant Cell Physiol. 45 1007–1014. 10.1093/pcp/pch115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y., Du Y., Jiang L., Liu J.-Y. (2007). Molecular analysis and expression patterns of the 14-3-3 gene family from Oryza sativa. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 40 349–357. 10.5483/BMBRep.2007.40.3.349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon G. M., Kieber J. J. (2013). 14-3-3 regulates 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate synthase protein turnover in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25 1016–1028. 10.1105/tpc.113.110106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Chen S., Harmon A. C. (2014). Protein phosphorylation in stomatal movement. Plant Signal. Behav. 9 e972845 10.4161/15592316.2014.972845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z., Zhang W., Stanley B. A., Assmann S. M. (2008). Functional proteomics of Arabidopsis thaliana guard cells uncovers new stomatal signaling pathways. Plant Cell 20 3210–3226. 10.1105/tpc.108.063263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H., Lin H., Chen S., Becker K., Yang Y., Zhao J., et al. (2014). Inhibition of the Arabidopsis salt overly sensitive pathway by 14-3-3 proteins. Plant Cell 26 1166–1182. 10.1105/tpc.113.117069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]