Abstract

Repulsive guidance molecule family members (RGMs) control fundamental and diverse cellular processes, including motility and adhesion, immune cell regulation, and systemic iron metabolism. However, it is not known how RGMs initiate signaling through their common cell-surface receptor, neogenin (NEO1). Here, we present crystal structures of the NEO1 RGM-binding region and its complex with human RGMB (also called dragon). The RGMB structure reveals a previously unknown protein fold and a functionally important autocatalytic cleavage mechanism and provides a framework to explain numerous disease-linked mutations in RGMs. In the complex, two RGMB ectodomains conformationally stabilize the juxtamembrane regions of two NEO1 receptors in a pH-dependent manner. We demonstrate that all RGM-NEO1 complexes share this architecture, which therefore represents the core of multiple signaling pathways.

The repulsive guidance molecule (RGM) family has three major, membrane-attached members: RGMA, RGMB (dragon), and RGMC (hemojuvelin, HFE2). Their functions span biological phenomena ranging from cell motility and adhesion (e.g., axon guidance, neural tube closure, and leucocyte chemotaxis) to immune cell regulation and systemic iron metabolism (1-5). Abnormal RGM expression or function has been linked to regenerative failure; inflammation (3); and diseases such as multiple sclerosis (6), cancer (7), and juvenile hemochromatosis (JHH) (5). All RGMs bind directly to the cell surface receptor neogenin (NEO1) (8), triggering structural rearrangements of the actin cytoskeleton through the Rho family of small guanosine-5′-triphosphate (GTP)–hydrolyzing GTPases that mediate cell repulsion (1, 9, 10). RGM binding to NEO1 activates the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)–regulated signaling involved in morphogenesis and iron homeostasis (11-14).

Human RGMs contain an Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) motif (conserved in RGMA and RGMC), which is important for integrin-mediated adhesive function (15), and a region homologous to the von Willebrand factor type D (vWfD) domain, which contains an autocatalytic Gly-Asp-Pro-His cleavage site (1, 16) (Fig. 1A). NEO1 is a type-I transmembrane protein of the immunoglobulin (Ig) receptor superfamily related to the netrin-1 receptor DCC (deleted in colorectal cancer) (17, 18). Its extracellular region consists of four Ig domains followed by six fibronectin type III (FN) domains and 50 juxtamembrane residues that are predicted to be unstructured. The cytoplasmic region comprises three conserved motifs (P1, P2, and P3) containing several phosphorylation sites and is required for receptor oligomerization of DCC (18, 19). FN domains five and six contain the binding site for RGMs (20). However, the molecular mechanisms underlying extracellular RGM reception by NEO1 and the mode of signal transduction across the membrane are not known.

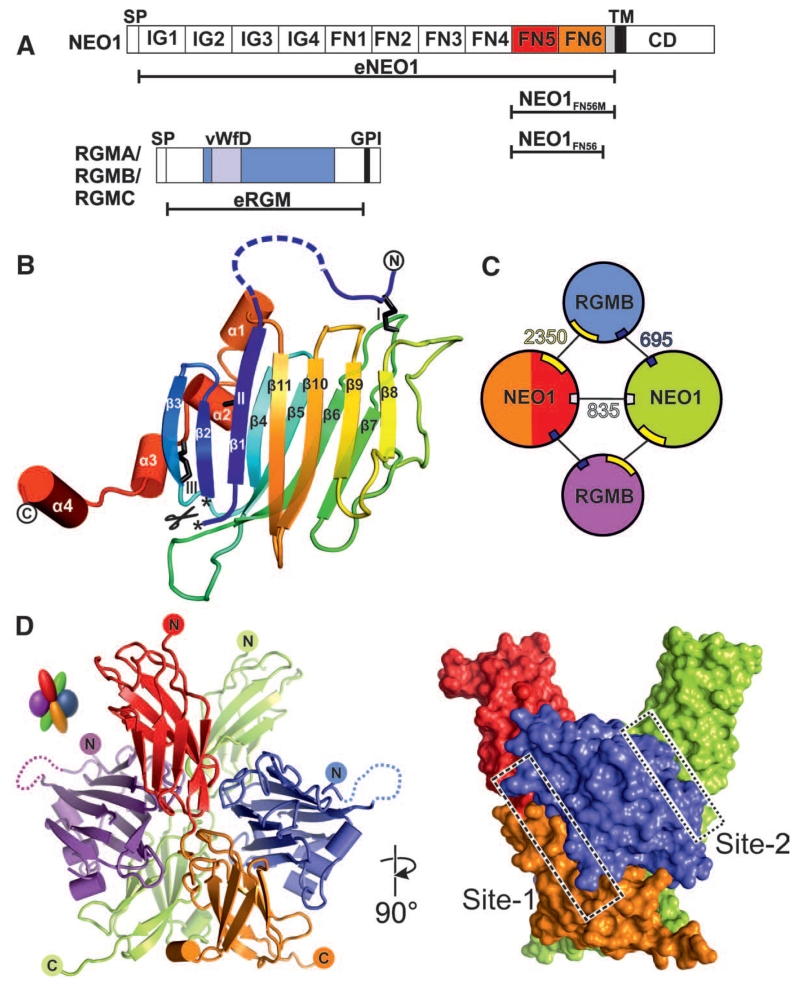

Fig. 1. Structure of the RGMB-NEO1 complex.

(A) Schematic of NEO1 and RGMs. SP indicates signal peptide; IG, Ig-like C2-type 1; TM, transmembrane; CD, C-terminal domain; GPI, glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor; and vWFD, von Willebrand factor D domain-like. (B) eRGMB ribbon diagram in rainbow coloring (blue, N terminus, red, C terminus). Disulfides (black sticks) are depicted with roman numerals. The autocatalytic cleavage site is marked with asterisks. (C) Schematics of the 2:2 RGMB-NEO1 complex. RGMB is blue and violet; NEO1 is red (FN5), orange (FN6), and green. Interface-buried surface areas (Å2) are shown. (D) Ribbon (left) and surface representation of the 2:2 eRGMB-NEO1FN56 complex. Site-1 and site-2 interfaces are highlighted with boxes. Color coding is as in (C). Right image is 90° rotated around the y axis compared with the left representation.

We solved a series of crystal structures of the fifth and sixth FN domains of NEO1 (NEO1FN56) in complex with the ectodomain of RGMB (eRGMB) (Fig. 1A, fig. S1, and table S1). In all of the NEO1-RGMB complexes, only the middle domain of RGMB (residues 134 to 338) could be resolved unequivocally. This domain represents a previously unknown protein fold consisting of a tightly packed β sandwich (Fig. 1B and fig. S2) extended by four short helices at the C terminus. The N and C termini, linked to the β sandwich by three disulfide bonds (fig. S3), point in opposite directions and into the solvent channels of the crystal, suggesting that the N- and C-terminal regions, which were disordered in the crystal, are flexible and do not associate with the middle domain. The autocatalytic cleavage site between Asp168-Pro169 is located in the loop connecting β sheets 1 and 2 (Fig. 1B and figs. S3A and S4) and is conserved in all RGM family members (fig. S3A). Asp-Pro bonds are hydrolyzed in low pH environments, for example, in the Golgi and secretory vesicles (21). This autocatalytic cleavage allows Pro169 to be deeply buried in the protein core (fig. S4A). Seven out of the 14 RGMC disease mutations leading to JHH (5, 22, 23), a severe iron-overload condition, cluster at the cleavage site (fig. S5). Ten of these map onto the β sandwich (fig S5A) and abolish protein secretion in mammalian cells (fig. S5B). These include Asp to Glu at position 172 (Asp172GluRGMC) from the cleavage site itself (figs. S4 and S5), highlighting the importance of autocatalytic cleavage for the structural integrity of the middle domain and indeed the entire protein.

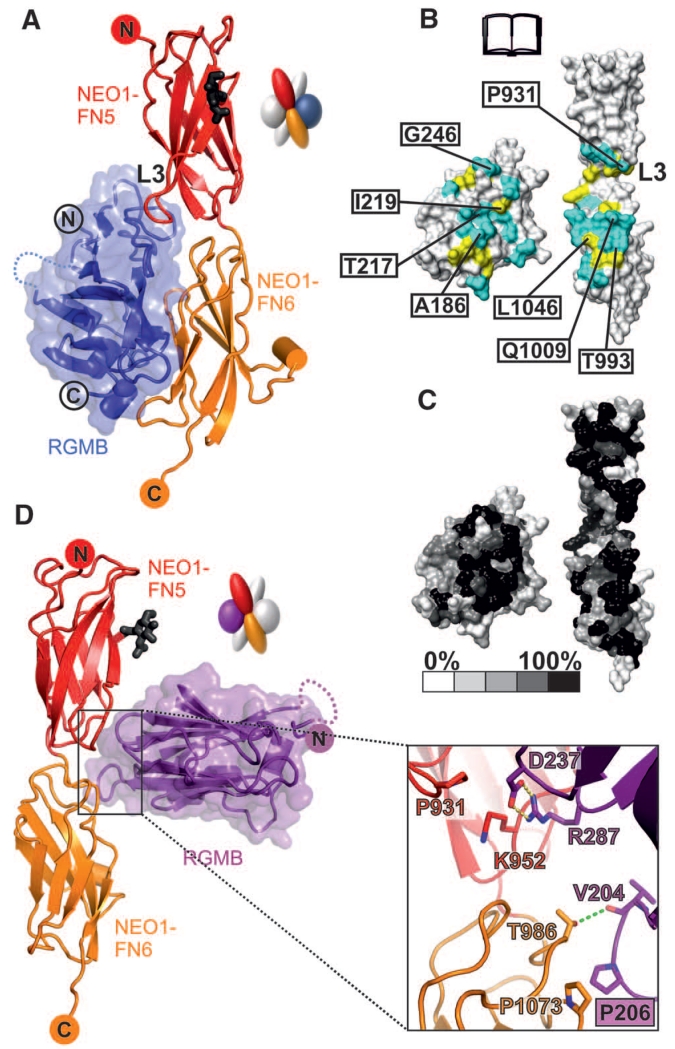

The eRGMB-NEO1FN56 complex structure determined at neutral pH [(24), fig. S6, and table S1] has a 2:2 stoichiometry and exhibits twofold symmetry with both NEO1 C-termini oriented in the same direction (Fig. 1, C and D), as observed in two independent crystal forms (fig. S6). Each RGMB molecule acts as a staple, bringing two NEO1 receptors together with one major interaction site (site 1) and a minor site (site 2) (Fig. 1, C and D), positioning the NEO1 C-termini in close proximity to each other (Fig. 1C). Whereas the two NEO1 molecules in the complex contact each other, the two RGMB molecules do not. Most of the site-1 contacts are formed between RGMB and the FN6 domain of NEO1, with the remainder of the interface made by the L3 loop of NEO1-FN5 (Fig. 2, A to C). The JHH-linked RGMC mutation Gly320ValRGMC, which cannot interact with NEO1 anymore (25), is located close to the site-1 interface (fig. S5D), thereby confirming the importance of the RGMB-NEO1 site-1 interface. We also solved three independent crystal structures of NEO1FN56 alone (table S1). Together with a previously reported NEO1 structure (26), these reveal flexibility or disorder of the L3 loop as well as variation in the relative orientation of the FN5 and FN6 domains, in contrast to the rigidity of the NEO1 molecules in the RGMB complex structures (fig. S7). The site-2 interaction between RGMB and the neighboring NEO1 molecule (Fig. 2D and fig. S8) has a buried surface area one-fourth the size of site 1 (Fig. 1C). Therefore, the site-1 interaction is likely to be the driving force for the RGM-NEO1 complex formation, whereas site 2 has a supporting role because of its shallow geometry and predominantly hydrophobic nature.

Fig. 2. Detailed interactions of the RGMB-NEO1 complex.

Color coding is as Fig. 1D. (A) Ribbon representation of the RGMB-NEO1 site-1 complex. The L3 loop of NEO1 is marked. (B and C) Open-book view showing the solvent-accessible surface of the site-1 interface (formed by 17 hydrogen bonds and 147 nonbonded contacts). (B) Interface residues (I, Ile; L, Leu; Q, Gln; T, Thr). Cyan, hydrophilic interactions; yellow, nonbonded contacts. Residues tested by site-directed mutagenesis and functional experiments are labeled. (C) Residue conservation (from nonconserved, white, to conserved, black) based on sequence alignments from vertebrate NEO1 and RGM family members. (D) Ribbon representation of the RGMB-NEO1 site-2 complex. The site-2 interaction uses the RGMB β5-β6 and β10-β11 loop regions contacting the NEO1 FN5 and FN6 domains. K, Lys; V, Val.

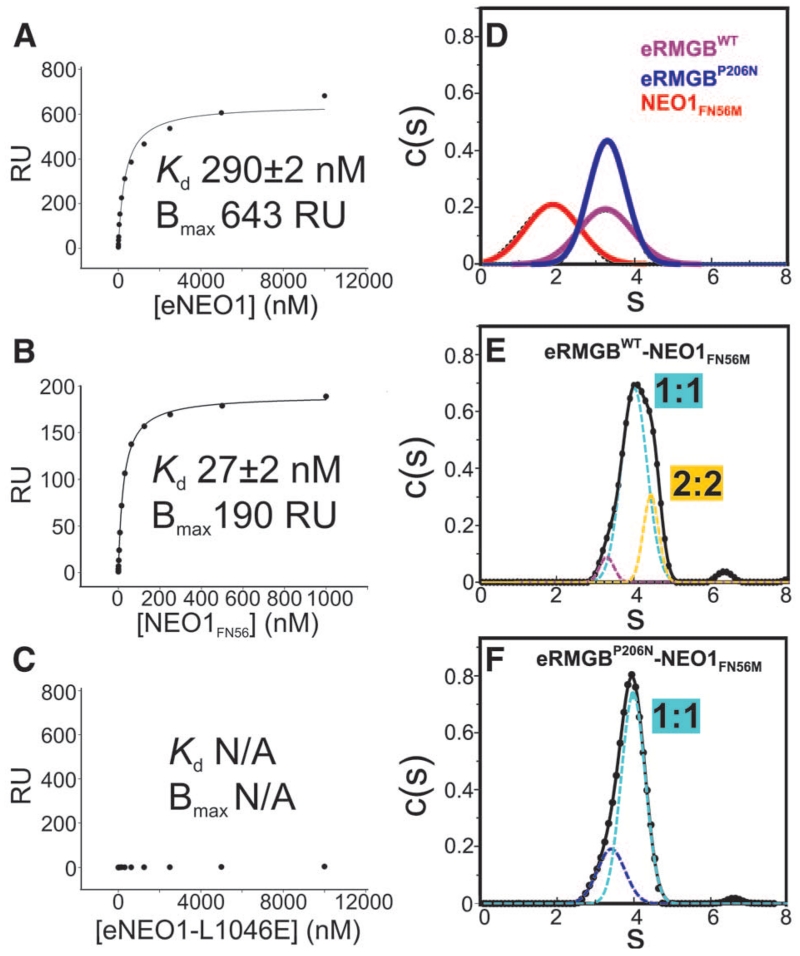

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) measurements revealed nanomolar equilibrium dissociation constants between the full-length ectodomains of NEO1 (eNEO1) and RGMA, RGMB, and RGMC, respectively (Fig. 3A and fig. S8). Furthermore, the truncated NEO1FN56 and NEO1FN56M constructs (Fig. 1A) were necessary and sufficient for the RGM interaction [Fig. 3B, fig. S9, and (20)]. Site-directed mutagenesis of site-1 interface residues abolished or severely impaired the NEO1-RGM interaction, validating the observed binding mode (Fig. 3C and figs. S9 and S10). Mutations in the L3 loop of NEO1-FN5 and the corresponding RGMB surface did not abolish binding, consistent with NEO1-FN5 being important but not essential for interaction with RGMs. Unlike the majority of site-1 residues, the L3 loop residues are not conserved between NEO1 and DCC, possibly explaining why no binding between RGMs and DCC was observed in immunoprecipitation experiments (8, 25). Indeed, the interaction between RGMA, RGMB, or RGMC and the full-length DCC ectodomain was one-thousandth that observed for the equivalent NEO1 construct (fig. S11).

Fig. 3. Biophysical characterization of the RGMB-NEO1 complex.

(A to C) SPR equilibrium binding. Different concentrations of eNEO1 (A), NEO1FN56 (B), and eNEO1-L1046E (where E is Glu) (C) were injected over surfaces coupled with eRGMB. RU, response units; Kd, dissociation constant; Bmax, maximum binding capacity; and N/A, not applicable. (D to F) Sedimentation velocity AUC experiments of eRGMB-WT [(D) violet], eRGMB-P206N [(D) blue], NEO1FN56M [(D) red], eRGMB-NEO1 (E), and eRGMB-P206N-NEO1 (F) complexes. Data fitted by using a continuous c(s) function (where s is the sedimentation coefficient) distribution model (solid line). Gaussian peaks contributing to the overall distributions (dotted lines) for eRGMB-NEO1 [(E), root mean square deviation (RMSD) = 0.0038] and eRGMB-P206N-NEO1 [(F), RMSD = 0.0063] complexes. Individual components run as monomeric species. The eRGMB-NEO1FN56M complex shows two major species, indicating both 1:1 and 2:2 complexes. The eRGMB-P206N mutation introduces an N-linked glycan at the site-2 interface. The resulting eRGMB-P206N-NEO1 complex shows a single species corresponding to the 1:1 complex.

To test whether the RGMB-NEO1 complex observed in the crystal structures exists in solution, we performed multiangle light scattering (MALS) measurements of purified proteins. At concentrations up to 3 μM, we observed a 1:1 RGMB-NEO1 complex (fig. S12A). Sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC), allowing exploration of higher concentrations of eRGMB and NEO1FN56M (up to 90 μM), revealed that the individual components were monomeric (Fig. 3D), and the RGMB-NEO1 mixture showed both a major species, corresponding to the 1:1 stoichiometry, and a higher-order oligomer, likely the 2:2 complex (Fig. 3E). A mutation of RGMB-Pro206 to asparagine in the site-2 interface (Fig. 2D), introducing an N-linked glycan, abolished the larger oligomer (Fig. 3F). The same AUC experiment performed with wild-type proteins at pH = 4.5 revealed only the 1:1 complex (fig. S12, B and C), suggesting that the site-2 interface is pH sensitive. This is in agreement with our structural data, because in a crystal form grown at pH = 4.5 to 5.0 (fig. S6C) the site-2 interface is absent, whereas site-1 is essentially identical to the neutral pH crystal form (fig. S7).

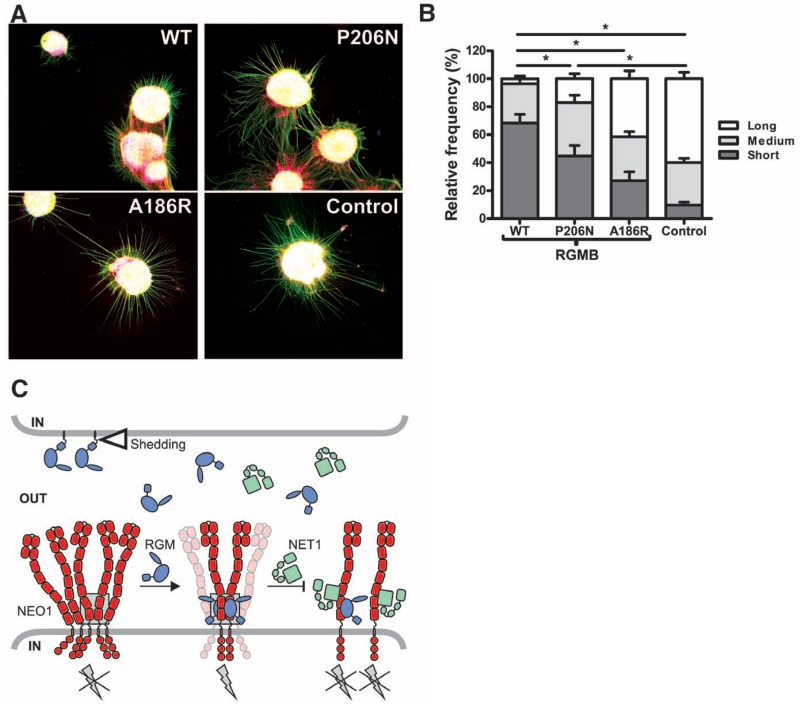

To explore the physiological relevance of the 2:2 oligomeric arrangement, we assessed the effect of RGMB mutants in neuronal explant cultures. Binding of RGMs to NEO1 inhibits neurite outgrowth from cerebellar granule neurons (CGNs) (27). To assess the functional consequences of site-1 and site-2 RGMB mutants, we cultured postnatal mouse CGN explants on substrates of control, RGMB-A186R (site-1 mutant with Ala changed to Arg at position 186), RGMB-P206N (site-2 mutant with Pro changed to Asn at position 206), and RGMB-WT (wild-type) proteins. As previously shown, neurite outgrowth was reduced on coverslips coated with RGMB-WT compared with control substrate (Fig. 4, A and B, and fig. S13). This inhibitory effect was not observed in neurons grown on RGMB-A186R and was reduced but not abolished by RGMB-P206N (Fig. 4 and fig. S13). These results support a functional role for RGMB-NEO1 interactions mediated through site-1 and to a lesser extent through site-2.

Fig. 4. Functional analysis of site-1 and -2 mutations on RGMB neurite growth inhibitory effects.

(A) Representative examples of P9 mouse CGN explants on coverslips coated with RGMB-WT (top left), site-2 mutant RGMB-P206N (top right), site-1 mutant RGMB-A186R (bottom left), or control (bottom right) proteins. Green, βIII-tubulin; red, F-actin; blue, nuclei. (B) Quantification of CGN neurite outgrowth. Distribution of neurite length (short, medium, and long) relative to the control is displayed (total number of explants analyzed for WT, n = 27; P206N, n = 24; A186R, n = 26; control n = 23); error bars are SEM, and *P < 0.01. (C) Model of trans RGMB-NEO1 signaling. RGM ectodomains can be shed by proteolytic or phospholipase activity (open triangle). RGM-binding to preclustered NEO1 results in formation of NEO1 dimers with a defined, signaling-compatible orientation that may be part of a supramolecular clustered state. This arrangement leads to activation of downstream signaling via RhoA (9) (gray lightning bolt). NET1 can inhibit RGM signaling by either simultaneous NEO1 binding or competing with the RGM-NEO1 interaction. The gray box highlights the RGM-NEO1 signaling hub observed in the crystal structure.

To investigate the RGM-NEO1 complex stoichiometry within a cellular context, we coexpressed full-length NEO1 tagged with either a His6 or 1D4 tag in human embryonic kidney 293T cells. We found that a specific antibody against NEO1-1D4 was able to coimmunoprecipitate NEO1-His6, indicating the presence of high-affinity NEO1 oligomers in the cellular lysate (fig. S14). This result suggests that NEO1 molecules may also be present in an RGM-independent, preclustered form at the cell surface.

The 2:2 stoichiometry of the RGM-NEO1 ectodomains may facilitate a common mechanism based on ligand-dependent receptor stabilization of NEO1 dimers within supramolecular signaling clusters (Fig. 4, C and D). Activation of the small GTPase RhoA and its downstream effectors Rho kinase and protein kinase C is a direct consequence of RGM-NEO1 interaction (9, 28). NEO1 can also interact with netrin-1 (NET1) (8), which functionally competes with RGMA, suppressing growth cone collapse in dorsal root ganglion axons (9). The NET1 binding site on the NEO1-related receptor DCC minimally involves the interface between its FN domains 4 and 5, including loop 5 of FN5 (29) occupied by a sucrose octasulphate (SOS) molecule in our apo-NEO1 structure (fig. S7B). This region, which borders the RGM interaction interface, is strictly conserved in NEO1 and DCC (fig. S3B), so NET1 might occupy the same position in NEO1, impairing the formation of an active 2:2 RGM-NEO1 complex and thus explaining the ability of NET1 to reduce RGM-induced growth cone collapse (Fig. 4C). An additional level of signaling control may be related to the subcellular localization of the RGM-NEO1 complex. The neutral pH at the cell surface allows an active 2:2 stoichiometry, whereas internalization and gradual acidification of the milieu promotes dissociation of the complex and signal termination. Such a signaling mechanism might prevent premature activation and allow dissociation upon internalization when RGM, NEO1, and associated proteins are expressed on the same cell.

Although diversity in the signaling triggered at downstream levels in a cell- and tissue-specific manner can be expected, our experimental evidence coupled with sequence conservation suggests that all RGM family members engage NEO1 in a similar way. Molecular details of the direct cross-talk between different receptors in signaling “supercomplexes,” such as RGM-NEO1-BMP ligand-BMP receptors (12-14), remain to be determined. However, we predict that the RGM-stapled NEO1 dimer provides a mode of pH-dependent organization, which forms the signaling hub common to multiple extracellular guidance cues and morphogens.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Diamond and European Synchrotron Radiation Facility beamline staff for assistance; T. Walter, K. Harlos, and G. Sutton for technical support; and M. Zebisch, E. Y. Jones, and D. I. Stuart for discussions. Work was funded by the Wellcome Trust (C.S.) and Human Frontier Science Program and the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (R.J.P.). The Division of Structural Biology is supported by a Wellcome Trust Core Grant. R.J.C.G. was a Royal Society University Research Fellow. A.R.A. was a Medical Research Council Career Development Award Fellow. C.S. is a Cancer Research UK Senior Research Fellow. Structure coordinates of eRGMB-NEO1FN56-Form 1, eRGMB-NEO1FN56-Form 2, eRGMB-NEO1FN56-Form 3, NEO1FN56-Form 1, NEO1FN56-Form 2, and NEO1FN56-SOS are deposited in the Protein Data Bank (identification codes 4BQ6, 4BQ7, 4BQ8, 4BQ9, 4BQB, and 4BQC, respectively).

Footnotes

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/science.1232322/DC1

Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S14

Table S1

References (30–59)

References and Notes

- 1.Monnier PP, et al. Nature. 2002;419:392–395. doi: 10.1038/nature01041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niederkofler V, Salie R, Sigrist M, Arber S. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:808–818. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4610-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mirakaj V, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108:6555–6560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015605108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xia Y, et al. J. Immunol. 2011;186:1369–1376. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papanikolaou G, et al. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:77–82. doi: 10.1038/ng1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muramatsu R, et al. Nat. Med. 2011;17:488–494. doi: 10.1038/nm.2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li VS, et al. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:176–187. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajagopalan S, et al. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6:756–762. doi: 10.1038/ncb1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conrad S, Genth H, Hofmann F, Just I, Skutella T. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:16423–16433. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610901200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hata K, et al. J. Cell Biol. 2006;173:47–58. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Babitt JL, et al. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:531–539. doi: 10.1038/ng1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou Z, et al. Dev. Cell. 2010;19:90–102. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee DH, et al. Blood. 2010;115:3136–3145. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-251199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang AS, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:12547–12556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608788200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiong JP, et al. Science. 2002;296:151–155. doi: 10.1126/science.1069040. 10.1126/science.1069040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lidell ME, Johansson ME, Hansson GC. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:13944–13951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210069200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson NH, Key B. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007;39:874–878. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai Wing Sun K, Correia JP, Kennedy TE. Development. 2011;138:2153–2169. doi: 10.1242/dev.044529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stein E, Zou Y, Poo M, Tessier-Lavigne M. Science. 2001;291:1976–1982. doi: 10.1126/science.1059391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang F, West AP, Jr., Allendorph GP, Choe S, Bjorkman PJ. Biochemistry. 2008;47:4237–4245. doi: 10.1021/bi800036h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Landon X. Methods Enzymol. 1977;47:145–149. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(77)47017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lanzara C, et al. Blood. 2004;103:4317–4321. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee PL, Beutler E, Rao SV, Barton JC. Blood. 2004;103:4669–4671. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Materials and methods are available as supplementary materials on Science Online.

- 25.Zhang AS, West AP, Jr., Wyman AE, Bjorkman PJ, Enns CA. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:33885–33894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506207200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang F, West AP, Jr., Bjorkman PJ. J. Struct. Biol. 2011;174:239–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu X, et al. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009;382:795–800. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.03.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hata K, Kaibuchi K, Inagaki S, Yamashita T. J. Cell Biol. 2009;184:737–750. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200807029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geisbrecht BV, Dowd KA, Barfield RW, Longo PA, Leahy DJ. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:32561–32568. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302943200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.