Abstract

Two-pore channels (TPCs) are ancient members of the voltage-gated ion channel superfamily that localize to acidic organelles such as lysosomes. The TPC complex is the proposed target of the Ca2 +-mobilizing messenger NAADP, which releases Ca2 + from these acidic Ca2 + stores. Whereas details of TPC activation and native ion permeation remain unclear, a consensus has emerged around their function in regulating endolysosomal trafficking. This role is supported by recent proteomic data showing that TPCs interact with proteins controlling membrane organization and dynamics, including Rab GTPases and components of the fusion apparatus. Regulation of TPCs by PtdIns(3,5)P2 and/or NAADP (nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate) together with their functional and physical association with Rab proteins provides a mechanism for coupling phosphoinositide and trafficking protein cues to local ion fluxes. Therefore, TPCs work at the regulatory cross-roads of (patho)physiological cues to co-ordinate and potentially deregulate traffic flow through the endolysosomal network. This review focuses on the native role of TPCs in trafficking and their emerging contributions to endolysosomal trafficking dysfunction.

Keywords: Ca2+, lysosomes, leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2), NAADP, two-pore channel 1 (TPCN1), two-pore channel 2 (TPCN2)

Introduction

The endolysosomal system is a heterogeneous collection of vesicular structures that dynamically interface to exchange trafficked substrates. The system serves as both a cellular entry and an exit portal that balances streams of traffic involved in internalization and export, biosynthesis and degradation. It is therefore unsurprising that endosomes, lysosomes and their related organelles are an active nexus for signalling events needed to regulate these different transport fluxes. A variety of cues, proteins (such as Rab GTPases), lipids [phosphoinositides, such as PtdIns(3,5)P2] and Ca2 + fluxes, regulate vesicular dynamics to shape the endolysomal system [1]. Understanding how such signals converge to coordinate traffic is needed to appreciate how cells sense and adapt to their environment. The importance of this problem is further underscored by scenarios of endolysosomal dysfunction. For example, lysosomal storage disorders have significant prevalence and lack curative therapeutics [2]. Emerging links to other pathologies highlight that trafficking fluxes through the endolysosomal system are central to the progression of a variety of diseases [3]. It is therefore crucial to understand the molecular choreography of cues that direct endolysosomal traffic. This review discusses recent data that implicates the two-pore channel (TPC) family as coordinators of endolysosomal dynamics. We introduce TPCs and discuss recent proteomic data that highlights a role for these channels in the coordination and mis-coordination of endolysosomal trafficking. We develop the idea that TPCs serve as a convergent point of co-ordination between Rab GTPases, PtdIns(3,5)P2 and localized ion fluxes.

Two-pore channels

TPCs are members of the voltage-gated ion channel superfamily [4–6]. A defining feature of these channels is their location to acidic organelles namely vacuoles (in plants) and vesicles of the endolysosomal system [7]. Plants possess a single TPC gene (or two closely related homologues). Animals in the deuterostome lineage usually possess three distantly related genes (TPC1–3) although there is unusual lineage-specific gene loss of TPC3 in humans and rodents [8,9]. In animals, TPC2 localizes to the lysosome whereas TPC1 shows a broader distribution throughout the endolysosomal system [10,11]. TPC3 has also been localized to acidic organelles and the plasma membrane [8,12,13]. For plant TPC and animal TPC2, trafficking to their respective locale is mediated by a dileucine signal in the N-terminus [14,15], a motif which targets other membrane proteins to the lysosomal system [16].

Another defining feature of these proteins is their duplicated domain architecture comprising two channel domains with six transmembrane regions arranged in tandem [17] (Figure 1). This distinctive structure identifies TPCs as probable descendants of the putative two domain evolutionary intermediate linking one domain channels such as voltage-gated K+ channels and four domain channels such as voltage-gated Ca2+ /Na+ channels [4]. It has been long-hypothesized that the latter arose through two rounds of intragenic duplication [18]. Recent phylogenetic analyses unites each domain of TPCs with counterparts in voltage-gated Ca2+ /Na+ channels supporting this transition [19]. Consistent with this ancestry, is the ‘loose’ pharmacological profile of TPCs whereby both Ca2+ and Na+ channel antagonists block the channel probably through a common ancestral-binding site predicted by molecular docking analyses [19]. Identification of a novel clade of TPCs in several unicellular species with ion selectivity filters similar to voltage-gated Ca2+ channels also supports kinship [19].

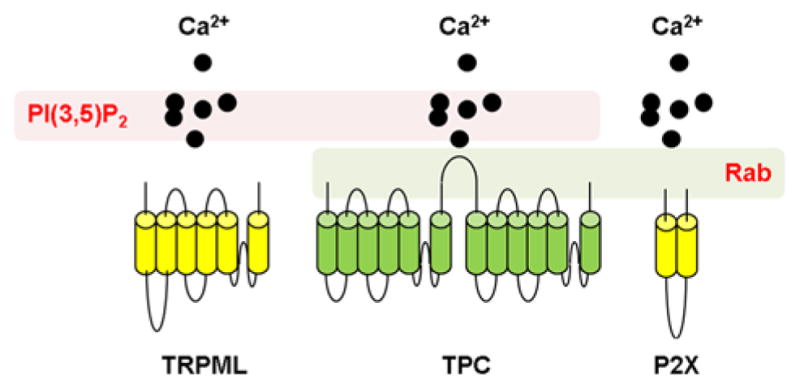

Figure 1. TPCs regulate membrane traffic by integrating Ca2 +, phosphoinositide and Rab cues.

Schematic representation showing topology of (cylinders) and Ca2 + flux through (black circles) TPCs (green), TRPML1 and P2X receptors (yellow). TRPMLs are regulated by the phosphoinositide, PtdIns(3,5)P2 (left). P2X receptors are regulated by Rab proteins (right). TPCs are regulated by both PtdIns(3,5)P2 and Rabs (centre).

In plants, TPCs are the molecular correlates of the SV (slow vacuolar) channels [20]. SV (slow vacuolar) channels have been extensively characterized electrophysiologically in part due to their abundance and the relative ease of recording from large vacuoles. They are non-selective Ca2+ -permeable channels regulated by voltage and both cytosolic and luminal Ca2+ [21]. They are thought to mediate Ca2+ release from the vacuole although this is debated and they have been implicated in several physiological processes including salt stress [22,23]. In animals, TPCs encode NAADP-sensitive Ca2+ channels [10,11,24]. NAADP is a second messenger produced upon stimulation which releases Ca2+ from lysosomes and lysosome-related organelles termed ‘acidic Ca2+ stores’ [25–28] Both loss- and gain-of-function experiments including electrophysiological recordings of TPC1 [29,30] and TPC2 [14,31,32] support the idea that TPCs function as NAADP targets [33]. But a series of studies have challenged this premise suggesting instead that TPCs are Na+ channels activated either by PtdIns(3,5)P2 (TPC2) [34] or by voltage (TPC1, 3) [13,35]. Thus, both the activating ligand and the ion permeability is unclear [36,37].

Inhibition of PtdIns(3,5)P2-mediated Na+ currents by cytoplasmic ATP has been reported and ascribed to activation of mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) [38,39], a key nutrient sensor and the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases, JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinase) and p38 [39]. PtdIns(3,5)P2-mediated Na+ currents are also inhibited by both cytoplasmic and luminal Mg2+ [39]. In the absence of Mg2+, NAADP-evoked Na+ currents are readily demonstrable [39] using the same recording configuration as Wang et al. [34] who failed to find any effect of NAADP on TPC activity. Such data and others [40] potentially reconcile some of the discrepancies in the literature regarding activation of TPCs by NAADP. Such data also highlight the importance of defining the regulatory properties of TPCs not least given evidence that activation of TPCs by NAADP may be mediated indirectly through low molecular mass NAADP-binding proteins [41–43].

Regulation of TPCs: a proteomic view

Our recent work using proteomics brings fresh perspective to understanding TPC regulation [44]. Proteomic methods are important as they provide an unbiased discovery approach for defining the composition of TPC complexes and their associated cellular roles. In our analyses [44], we resolved that Rab GTPases and other regulators of endomembrane dynamics interacted with TPCs, a discovery that provides molecular support to underpin the broader demonstration of TPC-dependent trafficking defects (see ‘TPCs and regulation of trafficking’).

To characterize the TPC interactome, we [44] employed an affinity purification method for protein complexes based upon ‘one-Strep’-tagging [3]. The ‘one-Strep’ tag is a short (~2 kDa), stable tag that binds to an engineered streptavidin with high affinity. This method for protein complex isolation has been previously used across diverse applications to define protein interactomes [45–49]. Over 60 candidate TPC interactors were defined (stringency of >five unique peptides identified for TPC1 and/or TPC2, absence from control purifications), including many proteins involved in the control of trafficking events [Rab GTPases and their regulators, syntaxins (STX16,18), synaptogyrins (SYNGR2,3)], Ca2+ signalling and autophagy, as well as previously known TPC interactors {mTOR [38], HAX-1 (HCLS1 associated protein X-1) [50]}. Whereas the broader dataset shows expected overlap with proteomic analysis of endolysosomal organelles (~40% representation of proteins commonly found in distinct endosomal lipid fractions [51]), the interactome is clearly uniquely TPC (bait) focused. The presence of proteins not previously assigned endolysosomal localizations is expected as TPCs are dynamically distributed not only across the endolysosomal system but also interact with other organelles at membrane contact sites, cell surface components during endocytosis and during lysosomal degradation of substrates delivered from other organelles. Additionally, TPC-evoked trafficking defects may promote capture of a broader diversity of organellar proteins as trafficking is perturbed [52]. Validating and determining the functional significance of these candidates will stimulate research into new aspects of TPC biology, as highlighted here for trafficking regulators. This focus is exciting given an independent proteomic study, despite using quite different methods, also converged on similar trafficking interactors. The study of Grimm et al. [53] employed the quantitative proteomic method of SILAC (stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture)-immunoprecipitation to resolve TPC2 interacting proteins [54,55], which allows specific interaction partners to be more readily distinguished from non-specific associations. In this method, cultured cells are incubated over multiple passages (typically >five doublings) with amino acids incorporating unique stable isotopes (‘light’ compared with ‘heavy’). One sample is transfected with the bait and samples mixed (either before or after) immunoprecipitation prior to proteomic analysis for differential representation of SILAC-labelled peptides. Experimental perturbations can be performed in forward (bait in ‘heavy’) and reverse (bait in ‘light’) to aid discrimination of specific interactors. As such, a lower number of higher confidence candidates are identified relative to affinity purification methods and this is a key advantage. In contrast, whereas the longer list of candidates from affinity purification approaches (including TAP-tagging) must be more carefully validated to exclude false positives, casting a broader net may be critical for capturing dynamic, transient interactions that are potentially important for TPC activation [41,42,56]. Grimm et al. [53] identified 26 TPC2 interactors from (HEK) human embryonic kidney cells transfected with mouse GFP–TPC2. Again trafficking proteins dominated the interactor list, including STX6, 7 and 12 and their interactors (VAMP2 [vesicle-associated membrane protein 2] and 3, VTI1B [vesicle transport through interaction with t-SNAREs homolog 1B]), Rab GTPases (RAB1A, B and C, Rab 11A and B and Rab 14), VPS45 (vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 45) and SYNGR1 and 2. The congruence between the two datasets [44,53] is therefore high (Figure 2). Approximately half of the interactors presented by Grimm et al. [53] were also found in the Lin-Moshier et al. [44] dataset. This proportion increases further when general clades, rather than identical isoforms, of proteins are considered (for example, SYNGR1 [53] compared with SYNGR3 [44]; LMAN1 (lectin, mannose-binding 1) [53] compared with LMAN2 [44], Figure 2). Overall, only four out of 26 proteins identified by Grimm et al. [53] are not represented in the study by Lin-Moshier et al. [44], despite the different proteomic procedures and methods employed in the two studies (difference in tags, tag orientation, TPC isoforms used). This convergence brings considerable confidence to the association between TPCs and these trafficking regulators and solid molecular support for observation of TPC-associated trafficking defects (see ‘TPCs and regulation of trafficking’).

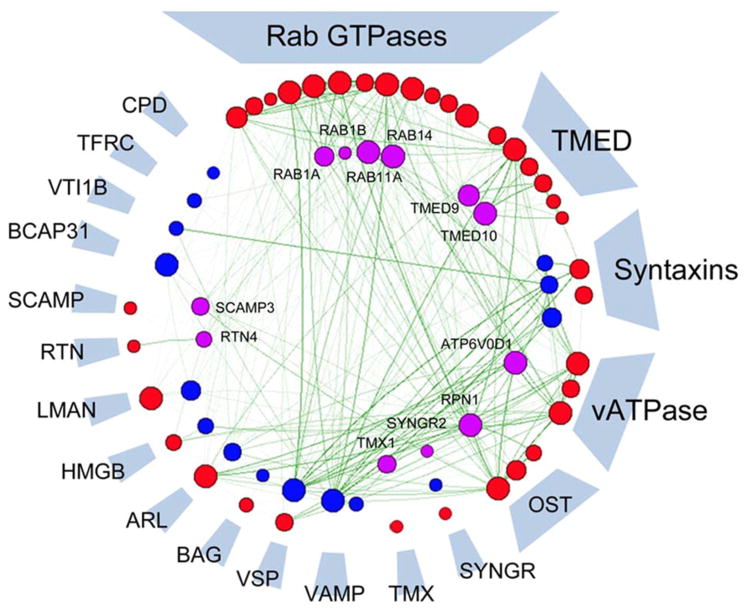

Figure 2. Converging traffic on TPC interactors.

Schematic representation highlighting the congruence between TPC interactors reported by Grimm et al. [53] within the Lin-Moshier et al. [44] dataset. Network nodes represent individual candidates identified in both datasets (purple, inner) or individual datasets {Grimm et al. [53] (blue), Lin-Moshier et al. [44] (red, outer)}. For example, 12 proteins (labelled) are identical in both datasets. Nodes are clustered into families circumferentially, with decreasing representation of candidate number per family clockwise. Only four candidates from the Grimm et al. [53] analysis were not represented in the Lin-Moshier et al. [44] dataset (10:00), highlighting the congruence between reports. Functional associations are predicted using FunCoup [26] and node size reflects summation of known protein-–protein interaction and predicted functional associations (green spokes).

Although these reports are an exciting, first step into documenting the cell biology of the TPC complex, a lot of work is still required to validate the functional significance of the numerous interactors discovered. It is also important to remember that any dataset is only as faithful as the methods used to generate it and both these foundational studies relied upon overexpression. TPC2 overexpression causes trafficking defects (see ‘TPCs and regulation of trafficking’), so the datasets may reflect a dysregulated trafficking state, rather than capturing interactions from endogenous TPCs under basal conditions [57]. Nevertheless, these datasets are a key first step for illuminating the cellular roles of both this ancient channel family [19] and the mercurial second messenger NAADP that activates TPCs [58]. Especially impactful will be the study of disease-linked genes identified in these studies. Several TPC interactors (ALDOA [aldolase A], PHB2 [prohibitin-2], PNKD [paroxysmal nonkinesigenic dyskinesia], TMEM165 [transmembrane protein 165], SFXN1 [sideroflexin 1], [44]) are associated with muscle and skeletal pathologies [59–65], where roles for TPCs have been evidenced [66,67]. Other interactors are biomarkers for tumour proliferation (Σ2R, CERS2 [ceramide synthase 2] SLC7A5 [solute carrier family 7 member 5], [44]) meriting attention to a role for TPCs in growth/dedifferentiation. Links between endolysosomal trafficking events and Parkinson’s disease were also evident and especially topical in the light of new data concerning the impact of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) mutants on TPC-regulated trafficking events (see ‘TPCs and dysregulation of trafficking’).

TPCs and regulation of trafficking

The significance of associations between TPCs and trafficking proteins is that they provide molecular grist to recently observed effects of TPCs on endolysosomal morphology and transport function [12,34,44,53,68–70]. Several groups have now reported that modulation of TPC expression or activity can affect the size, number or positioning of endolysosomal organelles, as well as the transport of various ligands through this system [12,34,44,53,68–70]. From this growing collection of studies, common principles emerge.

First, the role of TPCs in trafficking seems conserved. A consistent observation is enlargement of endolysosomal structures upon TPC overexpression [12,34,44,68]. Such effects are observed in non-mammalian systems (Xenopus) expressing mammalian TPCs [44] and conversely, after expression of non-mammalian TPCs (sea urchin) in mammalian cells [12]. This is suggestive that a regulatory role in trafficking is a key functionality for this ancestral ion channel family [19].

Second, TPC activity is required to yield trafficking phenotypes. This is clearly underscored by recent genetic loss-of-function studies that result in defects in processing and degradation of internalized ligands within the cell [53,69]. Most dramatically, TPC2 ablation has been shown to cause cholesterol accumulation in hepatocytes as a result of a speculated fusion defect in the distal (late endosomal to lysosomal) degradation pathway [53]. These TPC2-deficient mice exhibit hepatic cholesterol overload and fatty liver disease. Additionally, trafficking defects caused by TPC overexpression can be rescued by blocking TPC activity using NAADP antagonists [12], whereas trafficking defects are not caused by inactive TPC mutants [44]. Moreover, TPC activity within an appropriate cellular context is also required. TPCs must be correctly localized within the endolyosomal system with their appropriate effectors as rerouting active channels away from their endogenous milieu failed to cause trafficking phenotypes [44].

Third, localized TPC-evoked Ca2+ signals are likely mediators of trafficking effects. Recent studies have consistently shown, whatever the TPC-associated trafficking phenomenon being examined that effects are reversed/phenocopied by the fast, Ca2+ -selective chelator BAPTA (1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane- N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid), but not by EGTA (ethylene glycol-bis(2-aminoethylether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid) [44,53,70]. In Xenopus oocytes, for example, the pigmentation defects associated with TPC2 overexpression are corrected by co-incubation with BAPTA whereas BAPTA-treatment disrupts cholesterol and EGF (epidermal growth factor) trafficking in mouse embryonic fibroblasts similar to fibroblasts derived from TPC2−/− mice [53]. Such a requirement for Ca2+ is somewhat controversial, as is the issue of whether Ca2+ is directly sourced from TPC activity [34]. However, the consistent demonstration of these chelator effects merits further consideration of the role of local TPC-evoked Ca2+ microdomains that probably exist beneath the resolution of the conventional confocal imaging approaches applied to date [71]. Perhaps a small but significant Ca2+ flux through TPCs [14,29–32] provides an intimate signal-regulating fusion of closely apposed endolysosomal structures.

Beyond these convergent themes, other details are less clear. Central is the issue of how exactly do TPCs regulate trafficking? This is not a trivial issue to untangle within the malleable and dynamic system of intracellular vesicles that comprise acidic Ca2+ stores. As a yardstick, consider how controversial the mechanisms underpinning regulated exocytosis remained for decades even when cell surface accessibility facilitated electrophysiological and imaging interventions [72]. At present, the balance of published data suggests that endogenous TPC2 somehow acts to facilitate membrane fusion. This is based on both loss-of-function data where impairment of TPC2 function causes a traffic jam of internalized substrates [53] and gain-of-function analyses where overexpression of TPC2 causes lysosomal enlargement consistent with facilitation of fusion events [12,34,44]. Less is known about the role of TPC1 although curiously both overexpression [12] and knockdown [69] disrupt retrograde trafficking between endosomes and the Golgi.

We speculate that TPCs may not fulfill a standardized role across the spectrum of non-standardized environments that exist within the endolysosomal system. Their role is probably both cell type- and context-specific, reflecting specializations of individual cells and their complement of effectors. The functionality of TPCs may also adapt as normal cellular trafficking processes change during aging or are perturbed by disease [73] with the exciting possibility that TPCs may represent novel druggable targets for correcting trafficking abnormalities (see ‘TPCs and dysregulation of trafficking’, [70]).

TPCs and dysregulation of trafficking

The significance of TPCs for regulating endolysosomal trafficking extends to disease states where normal trafficking may be perturbed. An emerging example is Parkinson disease. Parkinson disease is a prevalent neurodegenerative disorder with a complex aetiopathogenesis [74,75]. A growing body of literature implicates lysosomal dysfunction in Parkinson disease [76] but the underlying mechanisms are not clear. Interaction of TPCs with proteins associated with Parkinson disease are therefore of interest [44]. STX1B has been linked to Parkinson’s disease risk through genetic association studies [77]. So too has CHP (calcium binding protein P22) [64,65]. Such data point to potential Ca2+ -dependent trafficking defects in the disease. Indeed, LRRK2, mutation of which causes an autosomal dominant form of Parkinson disease [78–80] has been shown to regulate autophagy in an NAADP- and TPC2-dependent manner [81]. That several of the effects of LRRK2 rely upon physical and functional association with endosomal Rabs [82–84] is particularly relevant in light of similar interactions between Rabs and TPCs and the other trafficking proteins discussed above.

Therefore, we probed endolysosomal morphology in patient fibroblasts from Parkinson disease sufferers with the common G2019S mutation in the kinase domain of LRRK2 [70]. Pronounced morphology defects characterized by enlargement of lysosomes and their clustering often in the perinuclear region were observed. Such phenotypes are reminiscent not only of the effects of TPC2 overexpression in Xenopus oocytes [44] but also of Rab7 activation [85,86]. Consistent with an involvement of both in the pathogenic actions of LRRK2 was the demonstrable reversal of lysosomal morphology defects by molecular silencing of TPC2 or pharmacological inhibition of Rab7 GTPase activity. Intriguingly, silencing of TPC1 was without effect matching the isoform selectivity seen in Xenopus oocytes [44,70]. Importantly, reversal of the defects could also be effected by antagonizing the actions of NAADP with the antagonist Ned-19 and by reducing PtdIns(3,5)P2 levels by inhibiting PIKfyve (phosphoinositide kinase, FYVE finger containing) [70]. Such data are consistent with co-regulation of TPCs by NAADP and PtdIns(3,5)P2 and support the electrophysiological analyses of Jha et al. [39] and Grimm [53] et al. Together, these data suggest a gain-of-function of TPC2 upon mutation of LRRK2. In accord NAADP-evoked Ca2+ signals were significantly larger in diseased cells relative to healthy controls. But in the context of the lysosomal morphology defects, such enhanced activity is probably manifest at the local level. This is because the defects were apparent in the absence of overt stimulation of the NAADP pathway and reversed by chelating Ca2+ with fast chelator BAPTA but not the slower chelator EGTA [70]. Defects in Xenopus oocytes also showed differential sensitivity to Ca2+ chelators [44]. It is thus tempting to speculate that de-regulated ‘constitutive’ Ca2+ signalling at the lysosomal interface may promote Ca2+ -dependent fusion thus accounting for enlargement. It is also tempting to speculate that TPC2 is a Rab7 effector in the context of lysosomal positioning. Whether such effects are due to direct phosphorylation of TPC2 by LRRK2 remains to be established although endolysosomal disturbances were dependent upon LRRK2 kinase activity [70]. Such data identify TPC2 and its associated regulators as potential therapeutic targets in Parkinson disease.

Conclusions: TPCs put it all together

The role of Ca2+ in regulating membrane traffic in the endolysosomal system has been long-recognized [87,88]. In an insightful study using Ca2+ chelators in vitro, Pryor et al. [87] proposed that endolysosomal fusion (and fission) was dependent on local Ca2+ release. To date most emphasis has been on the TRPMLs (transient receptor potential cation channel, mucolipin subfamily) as the ‘point source’ of Ca2+ since (like TPCs) they are endolysosomal proteins and ostensibly Ca2+ -permeable [1,89]. Such emphasis is deserved given that mutation of the TRPML1 causes the lysosomal storage disorder mucolipidosis type IV [90] in which trafficking defects within the endolysosomal system feature heavily. But as discussed above, TPCs also regulate trafficking and both TPCs and TRPMLs are regulated by PtdIns(3,5)P2 [34,39,53,91]. Consequently, both channel types could serve as focal points for integrating Ca2+ and phosophoinositide cues in the control of membrane traffic (Figure 1).

Regulation by Rab GTPases provides a further level of convergence. Precedence for such regulation comes from P2X receptors, which like TPCs also co-ordinate Ca2+ flux with Rab activity during trafficking [92]. Whereas P2X receptors are best known for their role on purinergic signalling at the plasma membrane [93], these receptors are also found on acidic organelles such as the contractile vacuole in Dictyostelium [94], lysosomes [95] and lysosome-related organelles [96]. Importantly, in Dictyostelium, P2X receptors formed complexes with Rab11 and CnrF (RabGAP/TBC domain-containing protein), a Ca2+ -dependent Rab GTPase-activating protein (GAP) with activity against Rab11. Ca2+ fluxes through vacuolar P2X receptors were proposed to activate CnrF which in turn down-regulated Rab11 activity through stabilizing its inactive (GDP-bound) form. This then allowed vesicle fusion to proceed [92].

Thus, intimate Ca2+ fluxes through TPCs and other resident channels on acidic organelles probably represent an evolutionary conserved mechanism to control membrane traffic [97]. Although such fluxes are coupled to phosphoinositides (in the case of TRPML) and Rab proteins (in the case of P2X receptors), TPCs couple to both phosphoinositides and Rabs (Figure 1). TPCs thus represent a point of convergence. They marry established regulators of membrane traffic that are often studied in isolation. Mechanistic understanding of such regulation is crucial to defining the role of TPCs in the control of membrane dynamics, an important task given emerging links to several diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Marchant and Patel laboratories for their helpful comments.

Funding

Supported by NIH [grant number GM088790 (to J.S.M.)], Parkinson’s U.K. [grant numbers H-1202 and K-1412 (to S.P.)] and Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council [grant numbers BB/G013721/1 and BB/K000942/1 (to S.P.)].

Abbreviations

- LRRK2

leucine-rich repeat kinase 2

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- STX

syntaxin

- SYNGR

synaptogyrin

- TPC

two-pore channel

References

- 1.Li X, Garrity AG, Xu H. Regulation of membrane trafficking by signalling on endosomal and lysosomal membranes. J Physiol. 2013;591:4389–4401. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.258301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Platt FM, Boland B, van der Spoel AC. The cell biology of disease: lysosomal storage disorders: the cellular impact of lysosomal dysfunction. J Cell Biol. 2012;199:723–734. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201208152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saftig P, Klumperman J. Lysosome biogenesis and lysosomal membrane proteins: trafficking meets function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:623–635. doi: 10.1038/nrm2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishibashi K, Suzuki M, Imai M. Molecular cloning of a novel form (two-repeat) protein related to voltage-gated sodium and calcium channels. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;270:370–376. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu FH, Yarov-Yarovoy V, Gutman GA, Catterall WA. Overview of molecular relationships in the voltage-gated ion channel superfamily. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:387–395. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clapham DE, Garbers DL. International Union of Pharmacology L. Nomenclature and structure-function relationships of CatSper and two-pore channels. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:451–454. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel S, Ramakrishnan L, Rahman T, Hamdoun A, Marchant JS, Taylor CW, Brailoiu E. The endolysosomal system as an NAADP-sensitive acidic Ca2 + store: role for the two-pore channels. Cell Calcium. 2011;50:157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brailoiu E, Hooper R, Cai X, Brailoiu GC, Keebler MV, Dun NJ, Marchant JS, Patel S. An ancestral deuterostome family of two-pore channels mediate nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate-dependent calcium release from acidic organelles. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:2897–2901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C109.081943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cai X, Patel S. Degeneration of an intracellular ion channel in the primate lineage by relaxation of selective constraints. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27:2352–2359. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brailoiu E, Churamani D, Cai X, Schrlau MG, Brailoiu GC, Gao X, Hooper R, Boulware MJ, Dun NJ, et al. Essential requirement for two-pore channel 1 in NAADP-mediated calcium signaling. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:201–209. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200904073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calcraft PJ, Ruas M, Pan Z, Cheng X, Arredouani A, Hao X, Tang J, Rietdorf K, Teboul L, Chuang KT, et al. NAADP mobilizes calcium from acidic organelles through two-pore channels. Nature. 2009;459:596–600. doi: 10.1038/nature08030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruas M, Rietdorf K, Arredouani A, Davis LC, Lloyd-Evans E, Koegel H, Funnell TM, Morgan AJ, Ward JA, Watanabe K, et al. Purified TPC isoforms form NAADP receptors with distinct roles for Ca2 + Signaling and endolysosomal trafficking. Curr Biol. 2010;20:703–709. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.02.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cang C, Aranda K, Ren D. A non-inactivating high-voltage-activated two-pore Na( + ) channel that supports ultra-long action potentials and membrane bistability. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5015. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brailoiu E, Rahman T, Churamani D, Prole DL, Brailoiu GC, Hooper R, Taylor CW, Patel S. An NAADP-gated two-pore channel targeted to the plasma membrane uncouples triggering from amplifying Ca2 + signals. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:38511–38516. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.162073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larisch N, Schulze C, Galione A, Dietrich P. An N-terminal dileucine motif directs two-pore channels to the tonoplast of plant cells. Traffic. 2012;13:1012–1022. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2012.01366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonifacino JS, Traub LM. Signals for sorting of transmembrane proteins to endosomes and lysosomes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:395–447. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hooper R, Churamani D, Brailoiu E, Taylor CW, Patel S. Membrane topology of NAADP-sensitive two-pore channels and their regulation by N-linked glycosylation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:9141–9149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.189985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hille B. Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rahman T, Cai X, Brailoiu GC, Abood ME, Brailoiu E, Patel S. Two-pore channels provide insight into the evolution of voltage-gated Ca2 + and Na + channels. Sci Signal. 2014;7:ra109. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peiter E, Maathuis FJ, Mills LN, Knight H, Pelloux J, Hetherington AM, Sanders D. The vacuolar Ca2 + -activated channel TPC1 regulates germination and stomatal movement. Nature. 2005;434:404–408. doi: 10.1038/nature03381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hedrich R, Neher E. Cytoplasmic calcium regulates voltage-dependent ion channels in plant vacuoles. Nature. 1987;329:833–836. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peiter E. The plant vacuole: emmitter and receiver of calcium signals. Cell Calcium. 2011;50:120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi WG, Toyota M, Kim SH, Hilleary R, Gilroy S. Salt stress-induced Ca2 + waves are associated with rapid, long-distance root-to-shoot signaling in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:6497–6502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319955111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zong X, Schieder M, Cuny H, Fenske S, Gruner C, Rotzer K, Griesbeck O, Harz H, Biel M, Wahl-Schott C. The two-pore channel TPCN2 mediates NAADP-dependent Ca2 + -release from lysosomal stores. Pflugers Arch. 2009;458:891–899. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0690-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee HC. NAADP-mediated calcium signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33693–33696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R500012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galione A, Morgan AJ, Arredouani A, Davis LC, Rietdorf K, Ruas M, Parrington J. NAADP as an intracellular messenger regulating lysosomal calcium-release channels. Biochem Soc Trans. 2010;38:1424–1431. doi: 10.1042/BST0381424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patel S, Docampo R. Acidic calcium stores open for business: expanding the potential for intracellular Ca2 + signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:277–286. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patel S, Muallem S. Acidic Ca2 + stores come to the fore. Cell Calcium. 2011;50:109–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rybalchenko V, Ahuja M, Coblentz J, Churamani D, Patel S, Kiselyov K, Muallem S. Membrane potential regulates NAADP dependence of the pH and Ca2 + sensitive organellar two-pore channel TPC1. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:20407–20416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.359612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pitt SJ, Lam AK, Rietdorf K, Galione A, Sitsapesan R. Reconstituted human TPC1 is a proton-permeable ion channel and is activated by NAADP or Ca2 + Sci Signal. 2014;7:ra46. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schieder M, Rotzer K, Bruggemann A, Biel M, Wahl-Schott CA. Characterization of two-pore channel 2 (TPCN2)-mediated Ca2 + currents in isolated lysosomes. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:21219–21222. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C110.143123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pitt SJ, Funnell T, Sitsapesan M, Venturi E, Rietdorf K, Ruas M, Ganesan A, Gosain R, Churchill GC, Zhu MX, et al. TPC2 is a novel NAADP-sensitive Ca2 + -release channel, operating as a dual sensor of luminal pH and Ca2 + J Biol Chem. 2010;285:24925–24932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.156927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hooper R, Patel S. NAADP on target. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;740:325–347. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-2888-2_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang X, Zhang X, Dong XP, Samie M, Li X, Cheng X, Goschka A, Shen D, Zhou Y, Harlow J, et al. TPC proteins are phosphoinositide- activated sodium-selective ion channels in endosomes and lysosomes. Cell. 2012;151:372–383. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cang C, Bekele B, Ren D. The voltage-gated sodium channel TPC1 confers endolysosomal excitability. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:463–469. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marchant JS, Patel S. Questioning regulation of two-pore channels by NAADP. Messenger. 2013;2:113–119. doi: 10.1166/msr.2013.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morgan AJ, Galione A. Two-pore channels (TPCs): current controversies. BioEssays. 2013;36:173–183. doi: 10.1002/bies.201300118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cang C, Zhou Y, Navarro B, Seo YJ, Aranda K, Shi L, Battaglia-Hsu S, Nissim I, Clapham DE, Ren D. mTOR regulates lysosomal ATP-sensitive two-pore Na( + ) channels to adapt to metabolic state. Cell. 2013;152:778–790. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jha A, Ahuja M, Patel S, Brailoiu E, Muallem S. Convergent regulation of the lysosomal two-pore channel-2 by Mg2 +, NAADP, PI(3,5)P2 and multiple protein kinases. EMBO J. 2014;33:501–511. doi: 10.1002/embj.201387035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Churamani D, Hooper R, Rahman T, Brailoiu E, Patel S. The N-terminal region of two-pore channel 1 regulates trafficking and activation by NAADP. Biochem J. 2013;453:147–151. doi: 10.1042/BJ20130474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin-Moshier Y, Walseth TF, Churamani D, Davidson SM, Slama JT, Hooper R, Brailoiu E, Patel S, Marchant JS. Photoaffinity labeling of nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP) targets in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:2296–2307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.305813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walseth TF, Lin-Moshier Y, Jain P, Ruas M, Parrington J, Galione A, Marchant JS, Slama JT. Photoaffinity labeling of high affinity nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide 2′-phosphate (NAADP) proteins in sea urchin egg. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:2308–2315. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.306563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walseth TF, Lin-Moshier Y, Weber K, Marchant JS, Slama JT, Guse AH. Nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide 2′-phosphate (NAADP) binding proteins in T-lymphocytes. Messenger. 2012;1:86–94. doi: 10.1166/msr.2012.1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin-Moshier Y, Keebler MV, Hooper R, Boulware MJ, Liu X, Churamani D, Abood ME, Brailoiu E, Patel S, Marchant JS. The two-pore channel (TPC) interactome unmasks isoform-specific roles for TPCs in endolysosomal morphology and cell pigmentation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:13087–13092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407004111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johansen LD, Naumanen T, Knudsen A, Westerlund N, Gromova I, Junttila M, Nielsen C, Bottzauw T, Tolkovsky A, Westermarck J, et al. IKAP localizes to membrane ruffles with filamin A and regulates actin cytoskeleton organization and cell migration. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:854–864. doi: 10.1242/jcs.013722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bingel-Erlenmeyer R, Kohler R, Kramer G, Sandikci A, Antolic S, Maier T, Schaffitzel C, Wiedmann B, Bukau B, Ban N. A peptide deformylase-ribosome complex reveals mechanism of nascent chain processing. Nature. 2008;452:108–111. doi: 10.1038/nature06683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Groth A, Corpet A, Cook AJ, Roche D, Bartek J, Lukas J, Almouzni G. Regulation of replication fork progression through histone supply and demand. Science. 2007;318:1928–1931. doi: 10.1126/science.1148992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schaffitzel C, Ban N. Generation of ribosome nascent chain complexes for structural and functional studies. J Struct Biol. 2007;158:463–471. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Junttila MR, Saarinen S, Schmidt T, Kast J, Westermarck J. Single-step strep-tag purification for the isolation and identification of protein complexes from mammalian cells. Proteomics. 2005;5:1199–1203. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200400991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lam AK, Galione A, Lai FA, Zissimopoulos S. Hax-1 identified as a two-pore channel (TPC)-binding protein. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:3782–3786. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lafourcade C, Sobo K, Kieffer-Jaquinod S, Garin J, van der Goot FG. Regulation of the V-ATPase along the endocytic pathway occurs through reversible subunit association and membrane localization. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2758. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang H, Fan X, Bagshaw RD, Zhang L, Mahuran DJ, Callahan JW. Lysosomal membranes from beige mice contain higher than normal levels of endoplasmic reticulum proteins. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:240–249. doi: 10.1021/pr060407o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grimm C, Holdt LM, Chen CC, Hassan S, Muller C, Jors S, Cuny H, Kissing S, Schroder B, Butz E, et al. High susceptibility to fatty liver disease in two-pore channel 2-deficient mice. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4699. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Trinkle-Mulcahy L, Boulon S, Lam YW, Urcia R, Boisvert FM, Vandermoere F, Morrice NA, Swift S, Rothbauer U, Leonhardt H, Lamond A. Identifying specific protein interaction partners using quantitative mass spectrometry and bead proteomes. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:223–239. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200805092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mann M. Functional and quantitative proteomics using SILAC. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:952–958. doi: 10.1038/nrm2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marchant JS, Lin-Moshier Y, Walseth TF, Patel S. The Molecular Basis for Ca2 + signalling by NAADP: two-pore channels in a complex? Messenger. 2012;1:63–76. doi: 10.1166/msr.2012.1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hubner NC, Mann M. Extracting gene function from protein-protein interactions using Quantitative BAC InteraCtomics (QUBIC) Methods. 2011;53:453–459. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Patel S, Marchant JS, Brailoiu E. Two-pore channels: Regulation by NAADP and customized roles in triggering calcium signals. Cell Calcium. 2010;47:480–490. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kreuder J, Borkhardt A, Repp R, Pekrun A, Gottsche B, Gottschalk U, Reichmann H, Schachenmayr W, Schlegel K, Lampert F. Brief report: inherited metabolic myopathy and hemolysis due to a mutation in aldolase. A N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1100–1104. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199604253341705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sun L, Liu L, Yang XJ, Wu Z. Akt binds prohibitin 2 and relieves its repression of MyoD and muscle differentiation. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:3021–3029. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ghezzi D, Viscomi C, Ferlini A, Gualandi F, Mereghetti P, DeGrandis D, Zeviani M. Paroxysmal non-kinesigenic dyskinesia is caused by mutations of the MR-1 mitochondrial targeting sequence. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:1058–1064. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rosnoblet C, Legrand D, Demaegd D, Hacine-Gherbi H, de Bettignies G, Bammens R, Borrego C, Duvet S, Morsomme P, Matthijs G, Foulquier F. Impact of disease-causing mutations on TMEM165 subcellular localization, a recently identified protein involved in CDG-II. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:2914–2928. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fleming MD, Campagna DR, Haslett JN, Trenor CC, III, Andrews NC. A mutation in a mitochondrial transmembrane protein is responsible for the pleiotropic hematological and skeletal phenotype of flexed-tail (f/f) mice. Genes Dev. 2001;15:652–657. doi: 10.1101/gad.873001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lesnick TG, Papapetropoulos S, Mash DC, Ffrench-Mullen J, Shehadeh L, de Andrade M, Henley JR, Rocca WA, Ahlskog JE, Maraganore DM. A genomic pathway approach to a complex disease: axon guidance and Parkinson disease. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e98. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim JM, Park SK, Yang JJ, Shin ES, Lee JY, Yun JY, Kim JS, Park SS, Jeon BS. SNPs in axon guidance pathway genes and susceptibility for Parkinson’s disease in the Korean population. J Hum Genet. 2011;56:125–129. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2010.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Aley PK, Mikolajczyk AM, Munz B, Churchill GC, Galione A, Berger F. Nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate regulates skeletal muscle differentiation via action at two-pore channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:19927–19932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007381107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Notomi T, Ezura Y, Noda M. Identification of two-pore channel 2 as a novel regulator of osteoclastogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:35057–35064. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.328930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lu Y, Hao BX, Graeff R, Wong CW, Wu WT, Yue J. Two pore channel 2 (TPC2) inhibits autophagosomal-lysosomal fusion by alkalinizing lysosomal pH. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:24247–24263. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.484253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 69.Ruas M, Chuang KT, Davis LC, Al-Douri A, Tynan PW, Tunn R, Teboul L, Galione A, Parrington J. TPC1 has two variant isoforms and their removal has different effects on endo-lysosomal functions compared to loss of TPC2. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34:3981–3992. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00113-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hockey LN, Kilpatrick BS, Eden ER, Lin-Moshier Y, Brailoiu GC, Brailoiu E, Futter C, Schapira AH, Marchant JS, Patel S. Dysregulation of lysosomal morphology by pathogenic LRRK2 is corrected by TPC2 inhibition. J Cell Sci. 2015;128:232–238. doi: 10.1242/jcs.164152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Penny CJ, Kilpatrick BS, Han JM, Sneyd J, Patel S. A computational model of lysosome-ER Ca2 + microdomains. J Cell Sci. 2014;127:2934–2943. doi: 10.1242/jcs.149047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weimer RM, Jorgensen EM. Controversies in synaptic vesicle exocytosis. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:3661–3666. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dickinson GD, Churchill GC, Brailoiu E, Patel S. Deviant NAADP-mediated Ca2 + -signalling upon lysosome proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:13321–13325. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C110.112573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hardy J. Genetic analysis of pathways to Parkinson disease. Neuron. 2010;68:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schapira AH, Jenner P. Etiology and pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2011;26:1049–1055. doi: 10.1002/mds.23732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dehay B, Martinez-Vicente M, Caldwell GA, Caldwell KA, Yue Z, Cookson MR, Klein C, Vila M, Bezard E. Lysosomal impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2013;28:725–732. doi: 10.1002/mds.25462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.International Parkinson’s Disease Genomics Consortium and Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2. A two-stage meta-analysis identifies several new loci for Parkinson’s disease. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zimprich A, Biskup S, Leitner P, Lichtner P, Farrer M, Lincoln S, Kachergus J, Hulihan M, Uitti RJ, Calne DB, et al. Mutations in LRRK2 cause autosomal-dominant Parkinsonism with pleomorphic pathology. Neuron. 2004;44:601–607. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Paisan-Ruiz C, Jain S, Evans EW, Gilks WP, Simon J, van der Brug M, Lopez de MA, Aparicio S, Gil AM, Khan N, et al. Cloning of the gene containing mutations that cause PARK8-linked Parkinson’s disease. Neuron. 2004;44:595–600. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Healy DG, Falchi M, O’Sullivan SS, Bonifati V, Durr A, Bressman S, Brice A, Aasly J, Zabetian CP, Goldwurm S, et al. Phenotype, genotype, and worldwide genetic penetrance of LRRK2-associated Parkinson’s disease: a case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:583–590. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70117-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gomez-Suaga P, Luzon-Toro B, Churamani D, Zhang L, Bloor-Young D, Patel S, Woodman PG, Churchill GC, Hilfiker S. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 regulates autophagy through a calcium-dependent pathway involving NAADP. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:511–525. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shin N, Jeong H, Kwon J, Heo HY, Kwon JJ, Yun HJ, Kim CH, Han BS, Tong Y, Shen J, et al. LRRK2 regulates synaptic vesicle endocytosis. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:2055–2065. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dodson MW, Zhang T, Jiang C, Chen S, Guo M. Roles of the Drosophila LRRK2 homolog in Rab7-dependent lysosomal positioning. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:1350–1363. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.MacLeod DA, Rhinn H, Kuwahara T, Zolin A, Di Paolo G, McCabe BD, Marder KS, Honig LS, Clark LN, Small SA, Abeliovich A. RAB7L1 interacts with LRRK2 to modify intraneuronal protein sorting and Parkinson’s disease risk. Neuron. 2013;77:425–439. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bucci C, Thomsen P, Nicoziani P, McCarthy J, van DB. Rab7: a key to lysosome biogenesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:467–480. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.2.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hutagalung AH, Novick PJ. Role of Rab GTPases in membrane traffic and cell physiology. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:119–149. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00059.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pryor PR, Mullock BM, Bright NA, Gray SR, Luzio JP. The role of intraorganellar Ca2 + in late endosome-lysosome heterotypic fusion and in the reformation of lysosomes from hybrid organelles. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:1053–1062. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.5.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Luzio JP, Pryor PR, Bright NA. Lysosomes: fusion and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:622–632. doi: 10.1038/nrm2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pryor PR, Reimann F, Gribble FM, Luzio JP. Mucolipin-1 is a lysosomal membrane protein required for intracellular lactosylceramide traffic. Traffic. 2006;7:1388–1398. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bargal R, Avidan N, Ben-Asher E, Olender Z, Zeigler M, Frumkin A, Raas-Rothschild A, Glusman G, Lancet D, Bach G. Identification of the gene causing mucolipidosis type IV. Nat Genet. 2000;26:118–123. doi: 10.1038/79095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dong XP, Shen D, Wang X, Dawson T, Li X, Zhang Q, Cheng X, Zhang Y, Weisman LS, Delling M, Xu H. PI(3,5)P2 controls membrane traffic by direct activation of mucolipin Ca2 + release channels in the endolysosome. Nat Commun. 2010;1 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1037. pii: 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Parkinson K, Baines AE, Keller T, Gruenheit N, Bragg L, North RA, Thompson CR. Calcium-dependent regulation of Rab activation and vesicle fusion by an intracellular P2X ion channel. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:87–98. doi: 10.1038/ncb2887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Khakh BS, North RA. P2X receptors as cell-surface ATP sensors in health and disease. Nature. 2006;442:527–532. doi: 10.1038/nature04886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fountain SJ, Parkinson K, Young MT, Cao L, Thompson CR, North RA. An intracellular P2X receptor required for osmoregulation in Dictyostelium discoideum. Nature. 2007;448:200–203. doi: 10.1038/nature05926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Qureshi OS, Paramasivam A, Yu JC, Murrell-Lagnado RD. Regulation of P2X4 receptors by lysosomal targeting, glycan protection and exocytosis. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:3838–3849. doi: 10.1242/jcs.010348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Miklavc P, Mair N, Wittekindt OH, Haller T, Dietl P, Felder E, Timmler M, Frick M. Fusion-activated Ca2 + entry via vesicular P2X4 receptors promotes fusion pore opening and exocytotic content release in pneumocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:14503–14508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101039108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Patel S, Cai X. Evolution of acid Ca2 + stores and their resident Ca2 + -permeable channels. Cell Calcium. 2015;57:222–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]