To the Editor:

Recently, two genome-wide association studies identified more than 10 novel susceptibility loci for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) (1, 2). Although some of these loci are located in or near genes with known functions (including mucin production, cell adhesion, and telomere biology), in many instances, the mechanisms through which these genetic variants confer IPF risk are not clear. We suspect that these IPF risk variants have pleiotropic effects and play roles in other diseases. Therefore, we postulate that understanding the spectrum of disease associated with these variants would lead to insights into mechanisms through which individual genes contribute to IPF risk.

To investigate IPF-associated genetic variants, we performed a phenome-wide association study (PheWAS) (3, 4) of 15 previously reported single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) identified by genome-wide association studies. PheWAS employs a genotype-to-phenotype association approach by linking subject-level deidentified genotyping information with electronic medical record–derived clinical phenotypes. In simple terms, PheWAS can be thought of as a “genome-wide association study in reverse.” The electronic medical record phenotypes are derived from clusters of common International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, codes collected from Vanderbilt’s de-identified electronic medical record and linked DNA repository, called BioVU. Among these 15 IPF-SNPs, rs6793295 (near telomerase RNA component, TERC) had genotyping information available on 36,400 subjects (genotyped on the Illumina HumanExome BeadChip array). Based on the platforms used for genotyping in BioVU, genotype information was available on fewer than 5,500 subjects for each of the other 14 SNPs, rendering them insufficiently powered for further analysis(4). For rs6793295, we performed a race-stratified (European ancestry) PheWAS, using previously validated methodology. Some of the results of this study have been previously reported in abstract form (5).

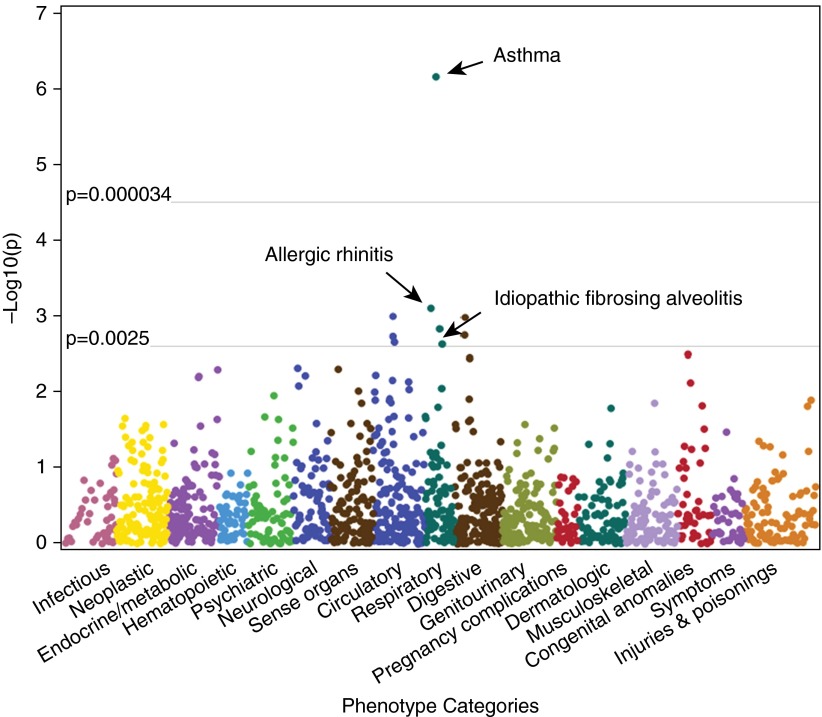

The previously reported association with IPF was confirmed (odds ratio [OR], 1.48; P = 2.4 × 10−3) (Figure 1). Nine clinical phenotypes were associated with rs6793295 (Table 1) at P < 0.0025, including four respiratory phenotypes. Surprisingly, a highly significant association of rs6793295 with asthma was identified (OR, 1.21; P = 6.9 × 10−7) (Figure 1). There were 1,739 asthma cases (mean age, 50.3 years, 63.1% female, and 20.9% children) and 23,889 controls (mean age, 54.2 years, 53.4% female, and 12.9% children). In addition, there was a strong association of rs6793295 with allergic rhinitis (OR, 1.11; P = 7.9 × 10−4) (Figure 1) that approached Bonferroni significance.

Figure 1.

Phenotype associations of rs6793295. Phenome-wide association study (PheWAS) plot for 1,492 phenotypes tested for association with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis-related single-nucleotide polymorphism near TERC, rs6793295. Phenotypes are arranged along the x-axis by categorization within the PheWAS code hierarchy. Horizontal lines indicate association thresholds P < 0.0025 and 3.3 × 10−5 (Bonferroni).

Table 1.

Phenotypes Significantly Associated with rs6793295

| PheWAS Phenotype Code | PheWAS Phenotype | Cases | Controls | OR | P Value | PheWAS Phenotype Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 495 | Asthma | 1,739 | 23,889 | 1.21 | 6.9 × 10−7 | Respiratory |

| 476 | Allergic rhinitis | 2,742 | 20,942 | 1.11 | 7.9 × 10−4 | Respiratory |

| 427.21 | Atrial fibrillation | 3,103 | 18,407 | 1.12 | 1.0 × 10−3 | Circulatory system |

| 528.11 | Stomatitis and mucositis (ulcerative) | 124 | 27,525 | 0.58 | 1.0 × 10−3 | Digestive |

| 499 | Cystic fibrosis | 168 | 29,470 | 1.45 | 1.5 × 10−3 | Respiratory |

| 528.1 | Stomatitis and mucositis | 477 | 27,525 | 0.78 | 1.8 × 10−3 | Digestive |

| 427.2 | Atrial fibrillation and flutter | 3,208 | 18,407 | 1.11 | 1.9 × 10−3 | Circulatory system |

| 427.41 | Ventricular fibrillation and flutter | 123 | 18,407 | 1.51 | 2.2 × 10−3 | Circulatory system |

| 504.1 | Idiopathic fibrosing alveolitis | 139 | 20,230 | 1.48 | 2.4 × 10−3 | Respiratory |

Definition of abbreviations: OR = odds ratio; PheWAS = phenome-wide association study.

This PheWAS provides proof of concept demonstrating the potential value of this technique in elucidating the mechanisms that underlie genetic risk for chronic lung disease. In addition to independently validating the previously reported association of a common genetic variant near TERC with IPF, we identified a previously unreported association with asthma and allergic rhinitis. These data indicate a potential genetic link between telomere biology and allergic airway disease.

Although prior studies have discovered numerous asthma-related genetic variants (6, 7), none has previously linked telomere-related genes to asthma, potentially because of insufficient power to detect variants with modest effect sizes. Alternatively, patients with asthma in our study population may represent a distinct (older and perhaps more severe) asthma phenotype that differs from those previously studied. Because our study population comprised subjects who had blood drawn for clinical laboratory testing, a substantial proportion of subjects in our analysis were hospitalized or seen in the emergency department. These cases may have poorer disease control, more frequent exacerbations, or more severe disease than the general population of patients with asthma. The association of this SNP with allergic rhinitis association further reinforces a link of rs6793295 with allergic disease.

Asthma has been linked to PBMC telomere length by several recent studies (8, 9), but the mechanisms through which asthma and telomere length are related remains unclear. Shortened telomere lengths were proposed to result from accelerated aging in the setting of increased oxidative stress resulting from the chronic inflammation in asthma. Our findings suggest that genetic factors may also underlie the association between telomere shortening in asthma.

Although our approach and study population offer unique advantages, this approach also has several limitations. Our analysis was limited to a single IPF-related SNP because of insufficient power on other genotyping platforms, and for low-frequency phenotypes, there was marginal power for this single SNP. A more comprehensive PheWAS of IPF-associated genetic variants would likely offer additional insights into the mechanisms of genetic risk for IPF, and we anticipate this will be possible in the future with additional genotyping of BioVU samples. In light of correlation of some phenotypes and limited power for many phenotypes, Bonferroni correction may be overly conservative. In addition, PheWAS phenotypes are derived from International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision billing codes and are therefore dependent on the intrinsic variations within coding schema, variation in application of the codes by physicians, and sensitivity of each individual code.

In summary, we identified a novel association between asthma and a genetic variant near TERC, a telomere gene locus previously linked with IPF. Our findings suggest future research should target the role of telomere pathology in asthma, with consideration given to linking underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms to other telomere-associated pulmonary diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and IPF. Moreover, this work highlights PheWAS as a unique discovery platform for novel genotype–phenotype relationships. These relationships may further understanding of genetic mechanisms of lung diseases through linkage to other disease phenotypes.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL094296 (J.A.K.), HL92870 (T.S.B.), HL085317 (T.S.B.), LM010685 (J.C.D.), K24 AI077930 (T.V.H.), U19 AI095227 (T.V.H.); the Department of Veterans Affairs (T.S.B.); the Francis Family Foundation (J.A.K.); and the American Thoracic Society Foundation/Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Career Award in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (J.A.K.). The dataset used for the analyses described was obtained from Vanderbilt University Medical Center's Synthetic Derivative, which is supported by institutional funding and by the Vanderbilt CTSA grant ULTR000445 from National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health.

Author Contributions: Designed study: D.D.C., E.K.L., J.E.L., and J.A.K; performed PheWAS data analysis: L.B. and J.C.D.; analyzed and interpreted data: L.B., J.C.D., D.D.C., E.K.L., T.S.B., J.E.L., T.V.H., and J.A.K.; wrote manuscript: D.D.C. and J.A.K.; and performed manuscript revision: D.D.C., E.K.L., L.B., T.S.B., J.E.L., T.V.H., J.C.D., and J.A.K.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Fingerlin TE, Murphy E, Zhang W, Peljto AL, Brown KK, Steele MP, Loyd JE, Cosgrove GP, Lynch D, Groshong S, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies multiple susceptibility loci for pulmonary fibrosis. Nat Genet. 2013;45:613–620. doi: 10.1038/ng.2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noth I, Zhang Y, Ma SF, Flores C, Barber M, Huang Y, Broderick SM, Wade MS, Hysi P, Scuirba J, et al. Genetic variants associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis susceptibility and mortality: a genome-wide association study. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1:309–317. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70045-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denny JC, Ritchie MD, Basford MA, Pulley JM, Bastarache L, Brown-Gentry K, Wang D, Masys DR, Roden DM, Crawford DC. PheWAS: demonstrating the feasibility of a phenome-wide scan to discover gene-disease associations. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1205–1210. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denny JC, Bastarache L, Ritchie MD, Carroll RJ, Zink R, Mosley JD, Field JR, Pulley JM, Ramirez AH, Bowton E, et al. Systematic comparison of phenome-wide association study of electronic medical record data and genome-wide association study data. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:1102–1110. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Claar D, Larkin EK, Bastarache L, Blackwell TS, Loyd JE, Denny JC, Kropski JA. A Phenome-Wide-Association Study (PheWAS) identifies common genetic risk among clinical risk factors for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) [abstract] Am J Crit Care Med. 2015;191:A2204. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moffatt MF, Gut IG, Demenais F, Strachan DP, Bouzigon E, Heath S, von Mutius E, Farrall M, Lathrop M, Cookson WO GABRIEL Consortium. A large-scale, consortium-based genomewide association study of asthma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1211–1221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bønnelykke K, Sleiman P, Nielsen K, Kreiner-Møller E, Mercader JM, Belgrave D, den Dekker HT, Husby A, Sevelsted A, Faura-Tellez G, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies CDHR3 as a susceptibility locus for early childhood asthma with severe exacerbations. Nat Genet. 2014;46:51–55. doi: 10.1038/ng.2830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albrecht E, Sillanpää E, Karrasch S, Alves AC, Codd V, Hovatta I, Buxton JL, Nelson CP, Broer L, Hägg S, et al. Telomere length in circulating leukocytes is associated with lung function and disease. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:983–992. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00046213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belsky DW, Shalev I, Sears MR, Hancox RJ, Lee Harrington H, Houts R, Moffitt TE, Sugden K, Williams B, Poulton R, et al. Is chronic asthma associated with shorter leukocyte telomere length at midlife? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:384–391. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201402-0370OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]