The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-V) contains a far more detailed exposition of the place of “culture” in psychopathology than any previous edition of the manual. At the same time, culture has also become the basis from which two of the major attacks on the DSM-V have been waged. The whole DSM project risks unravelling if the concept of culture is not addressed in substantially different terms. One crucial revision must be to recognize pharmaceutical uses as a part of culture.

The DSM-V comprises three sections on culture. “Cultural issues” are first mentioned in the Introduction.1 A chapter is devoted to “Cultural formulation,” which extends the discussion of culture and outlines the “Cultural Formulation Interview.”1 The “Glossary of cultural concepts of distress”1 lists well-documented syndromes such as ataque de nervios, dhat and susto.

The manual echoes classic definitions from cultural anthropology. “Culture” is said to be the totality of norms and values held by individuals, families, social systems and institutions. Culture encompasses “systems of knowledge, concepts, rules, and practices.”1 Language, religion, spirituality, kinship, rituals and laws are all part of culture. One becomes a member of a culture by internalizing shared norms and values.

The DSM-V lists many areas in which culture matters for psychiatric practice. It provides patients with an “interpretive framework” that shapes both the “experience” of mental distress and its “expression.” What is still “normal” and what is already “pathological” will differ according to cultural norms and expectations. The previous concept of “culture-bound syndromes” is rejected and replaced by “cultural syndromes,” “cultural idioms of distress” and “cultural explanation/perceived causes.”

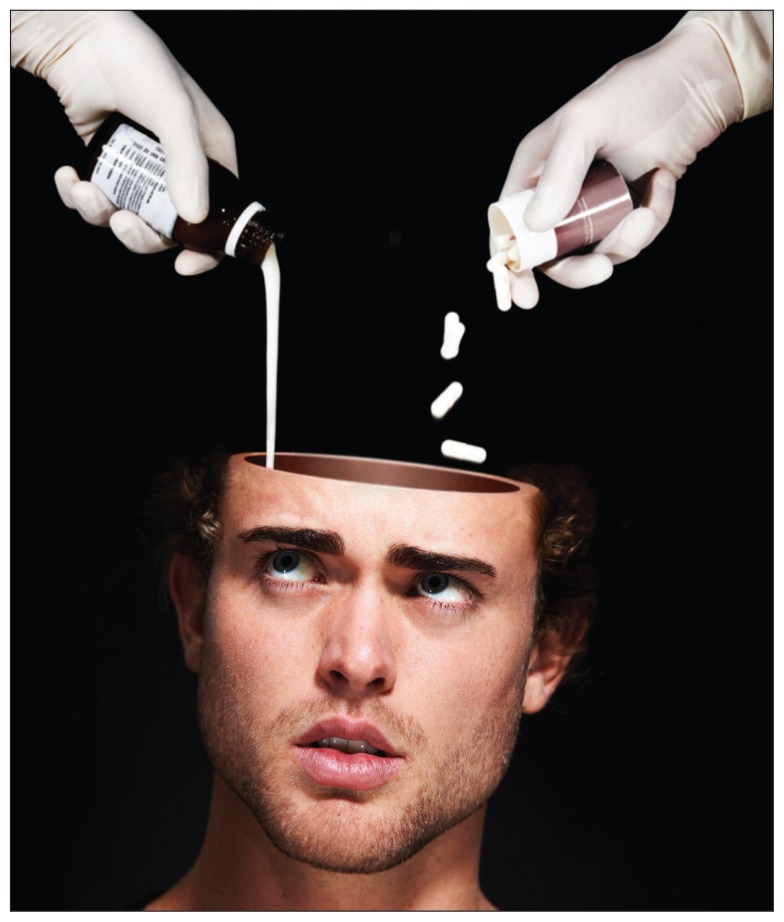

Image courtesy of PeopleImages/iStock

It has often been said that DSM classifications will always be uncertain, arbitrary or nothing more than the results of horse-trading in committee meetings.2 Most assumed that the authors of the DSM would never part from claims of ahistorical truths and be “reluctant to see their creations as historical, cultural, ideological products rather than as scientific documents.”3 Yet, the DSM-V took these culturalist criticisms on board and made them its own: “Like culture and DSM itself, cultural concepts may change over time in response to both local and global influences”1 [emphasis added]. All the diagnostic labels used in the DSM had specific cultural origins: “The current formulation acknowledges that all forms of distress are locally shaped, including the DSM disorders”1 [emphasis in the original].

If the American Psychiatric Association acknowledges that the DSM is itself a product of “culture” and that all its categories are “locally shaped,” where does this leave the argument that the DSM leads to the medicalization of normal feeling and behaving? This criticism has been made against the DSM for decades, but has never been as vociferous as now. The British Psychological Society,4 for example, published a manifesto against “the continued and continuous medicalisation of ... natural and normal responses.” The mainstream media took a similar position and worried about how “abnormal is the new normal.” The argument runs that the DSM-V, more than any previous version, devalues cultural patterns of feeling and behaving in favour of excessive medical interventionism.

A prominent voice against medicalization is Allen Frances, chair of the DSM-IV Task Force. Frances predicts “a bonanza for the pharmaceutical industry but at a huge cost to the new false-positive patients caught in the excessively wide DSM-V net.”5 For example, the removal of the bereavement exclusion from the diagnosis of depression was an attempt at medicalizing normal sadness and turning it into a psychiatric condition: “Turning bereavement into major depression would substitute a shallow, Johnny-come-lately medical ritual for the sacred mourning rites that have survived for millenniums.”6 It is not without irony that Frances, who suppressed a substantial expansion of “culture” in the DSM-IV, would turn into an über-culturalist, but this is what has happened.

Another attack on the DSM-V came from within biopsychiatry and focused on the manual’s “lack of validity.” Shortly before the DSM-V was launched, Thomas Insel, former director of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), ridiculed the DSM approach to disease classification as an intuitive art rather than a hard science: “DSM diagnoses are based on a consensus about clusters of clinical symptoms, not any objective laboratory measure” [emphasis added].7 Because the DSM could never move beyond mere opinions arrived at through consensus decisions, the NIMH “will be re-orienting its research away from DSM categories.”7 Doubts about the validity of DSM classification go back more than a decade and were a key part of the post–DSM-IV revision agenda. The failure of DSM-V to make any progress in this area has turned this doubt into dread.

Clearly, the medicalization critique is a kind of cultural critique.8 It is less obvious that the biopsychiatric argument against the DSM-V also comes from a culturalist position. When Insel finds that the DSM is based on a “consensus” rather than objective measures, he is making the same point that Frances and the critics of medicalization have been making all along: that the DSM is produced by a human, all-too-human community of psychiatrists, and that their ideas about psychopathology are mere conventions.

Neither group of critics seem to have noticed, however, that the DSM-V might find a defence against these attacks in its culture sections. Could the authors not turn around and say that both the “medicalization” and the “lack of validity” allegations have already been acknowledged and answered because everything is now “culture,” including the DSM?

The culture sections provide a kind of apology for the DSM. But it seems like a shallow apology. Why is it shallow? It is shallow because what is presented as “culture” in the DSM-V is too focused on meaning and not enough on practice. Its culture sections are based on the hermeneutic, meaning-centred tradition in anthropological theory. This approach is good at dealing with ideas, but it is bad at grasping material, nonhuman things that co-constitute everything that humans experience.

Things matter in psychiatry. There are many things that change how psychiatrists detect, diagnose and treat mental illnesses. One kind of material artifact that makes a huge difference is the psychopharmaceutical. There are many examples for why drugs matter. Drugs matter for research: DSM classifications and psychopharmacology have been developing hand in hand since DSM-III. Clinical trials for various compounds need to enrol patients with specific problems rather than a diffuse spectrum of complaints. The more specific the diagnosis, the easier it is to conduct trials and to provide the evidence needed to get market approval. Drugs matter for diagnostic practices: most psychiatrists first consider what kind of drug might work on a particular patient, and then tailor their diagnoses toward that.2,9 Drugs matter for patients’ expectations and demands of doctors. Direct-to-consumer marketing, especially in North America, asks patients to see immediate links between illnesses and drugs, putting pressure on prescribing doctors (“ask your doctor if drug X is right for you”). Drugs matter because they shift what is “culturally” normal. For example, “cultures of bereavement” are not immune to the availability of antidepressants or tranquillizers. There are countless loops between drugs and cultural expectations.10 In my ethnographic work on changing notions of mental illness in India,9 I would not know how to use the culture sections of the DSM-V because everything I encounter hinges on the uses of psychopharmaceuticals.

Both the “medicalization” critique and the “lack of validity” critique also point to missing materialities in the DSM-V, be it the overuse of psychotropic medications or the absence of biogenetic substrates. If the DSM-VI is going to be relevant, it needs to account for things that matter in both its diagnostics and its definitions of culture.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Fifth edition Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shorter E. The history of DSM. In: Paris J, Phillips J, editors. Making the DSM-5: concepts and controversies. New York: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phillips J. Conclusion. In: Paris J, Phillips J, editors. Making the DSM-5: concepts and controversies. New York: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Response to the American Psychiatric Association: DSM-5 development; London (UK): British Psychological Society; 2011. Available: http://apps.bps.org.uk/_publicationfiles/consultation-responses/DSM-5%202011%20-%20BPS%20response.pdf (accessed 2015 Mar. 4) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frances A. A warning sign on the road to DSM-V: Beware of its unintended consequences. Psychiatric Times 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frances A. Good grief. The New York Times, 2010. August 14. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Insel T. Director’s blog: Transforming diagnosis. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Mental Health; 2013. Available: www.nimh.nih.gov/about/director/2013/transforming-diagnosis.shtml (accessed 2015 Mar. 4). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pickersgill MD. Debating DSM-5: diagnosis and the sociology of critique. J Med Ethics 2014;40:521–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ecks S. Eating drugs: psychopharmaceutical pluralism in India. New York: New York University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elliott C. Enhancement technologies and the modern self. J Med Philos 2011;36:364–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]