Abstract

Although Down syndrome (DS) can be diagnosed prenatally, currently there are no effective treatments to lessen the intellectual disability (ID) which is a hallmark of this disorder. Furthermore, starting as early as the third decade of life, DS individuals exhibit the neuropathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) with subsequent dementia, adding substantial emotional and financial burden to their families and society at large. A potential therapeutic strategy emerging from the study of trisomic mouse models of DS is to supplement the maternal diet with additional choline during pregnancy and lactation. Studies demonstrate that maternal choline supplementation (MCS) markedly improves spatial cognition and attentional function, as well as normalizes adult hippocampal neurogenesis and offers protection to basal forebrain cholinergic neurons (BFCNs) in the Ts65Dn mouse model of DS. These effects on neurogenesis and BFCNs correlate significantly with spatial cognition, suggesting functional relationships. In this review, we highlight some of these provocative findings, which suggest that supplementing the maternal diet with additional choline may serve as an effective and safe prenatal strategy for improving cognitive, affective, and neural functioning in DS. In light of growing evidence that all pregnancies would benefit from increased maternal choline intake, this type of recommendation could be given to all pregnant women, thereby providing a very early intervention for DS fetuses, and include babies born to mothers unaware that they are carrying a DS fetus.

Keywords: attention, basal forebrain, choline, cholinergic neurons, hippocampus, spatial learning, Ts65Dn mice

Introduction

Down syndrome (DS) is estimated to affect ~350,000 – 400,000 people in the USA, with ~5,000 infants born each year with the disorder [1–5]. DS is caused by the triplication of human chromosome 21 (HSA21) and is the primary genetic cause of intellectual disability (ID) [4, 6–8]. DS has increased in prevalence in the last 40 years, from ~1:1,100 in the 1970s to ~1:650 by 2006 [4, 9]. The life expectancy of individuals with DS has also increased substantially in recent years, from ~12 years of age in the 1940s, to the sixth and seventh decade of life currently [10, 11]. Individuals with DS generally exhibit significant intellectual difficulty with the most pronounced dysfunction in hippocampal-dependent learning and memory, attentional function, and language and communication skills [12, 13] (see Marwan and Edgin, article in this issue). The phenotype is presumed to be caused by overexpression of >550 genes and putative protein-encoding gene transcripts, including >160 known protein encoding transcripts termed the ‘DS critical region’ [14]. In addition to impaired central nervous system (CNS) function during development and adult life, individuals with DS develop Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology in early middle age (frequently by the third decade of life), including amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques, neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), degeneration of cholinergic basal forebrain (CBF) neurons, and early endosomal abnormalities [15–22]. Consistent with these neurodegenerative changes, it is estimated that 50%–70% of DS individuals over the age of fifty display clinical dementia [5, 8, 17], although these may be underestimates due to the difficulty in diagnosing dementia in people with ID [23]. Currently, there are no therapeutic interventions that prevent or reverse ID, age-related cognitive impairment, or brain pathology in DS.

Murine trisomic models

Animal models of DS provide an opportunity to elucidate neural mechanisms underlying the cognitive and neuropathological deficits in DS and provide experimental paradigms for testing novel therapies (see Granholm et al., article in this issue). A variety of mouse models have been engineered that recapitulate aspects of DS and AD neuropathology [24–27]. The Ts65Dn trisomic mouse model is one of the most widely utilized models of both DS and AD-like pathology. Ts65Dn are trisomic for a segment of mouse chromosome 16 (MMU16) and mouse chromosome 17 (MMU17) orthologous to HSA21. Notably, the distal end of MMU16 is translocated to <10% of the centromeric end of MMU17, creating a small translocation chromosome [28–31]. This segmental region includes genomic information proximal to amyloid-beta precursor protein (App) extending to Myxovirus (influenza virus) resistance 1, interferon-inducible protein p78 (mouse) (Mx1) and exhibits ~55% gene conservation of known protein coding genes between MMU16 and HSA21 [14, 30–32]. Importantly, these mice survive into adulthood and exhibit key morphological, biochemical, and transcriptional changes similar to that seen in human DS and AD [27, 29–31, 33, 34]. Like humans with DS, these mice are born with intact basal forebrain cholinergic neurons (BFCNs) [29, 35, 36], but these neurons atrophy by 6 months of age, accompanied by astrocytic hypertrophy and microglial activation [29, 36–38]. The cholinergic septohippocampal circuit is particularly vulnerable in both DS and AD [29, 36, 39–42] (see Kelley et al., article in this issue).

Consistent with these neurodegenerative changes, the most pronounced cognitive deficits in humans with DS and Ts65Dn mice pertain to functions modulated by the two major cholinergic basal forebrain projection systems: (a) explicit memory function, modulated by projections arising from the cholinergic neurons of the medial septal nucleus/vertical limb of the diagonal band (MSN/VDB) which innervate the hippocampus [36, 43–45], and (b) attention and working memory, modulated by projections arising from the cholinergic neurons located within the nucleus basalis of Meynert (NBM)/substantia innominata (NBM/SI) which project to the frontal cortex [46–48]. As in humans with DS, cognitive functioning in Ts65Dn mice declines during adulthood, coincident with the loss of the BFCN phenotype [36, 45, 49]. Using the Ts65Dn mouse model of DS/AD, our group has identified a putative novel therapeutic intervention that holds great promise for improving cognitive outcome and offering neuroprotection to the cholinergic projection system in DS; namely, supplementing the maternal diet with additional choline during pregnancy and lactation.

Beneficial effects of increased dietary maternal choline intake

Choline is a molecule composed of three methyl groups covalently attached to the nitrogen atom of ethanolamine, which serves as the precursor molecule of several metabolites [50, 51]. Choline is classified as an essential nutrient, meaning that dietary intake of this nutrient is required for proper health, although it is produced to some degree by the body [52, 53]. Choline is widely distributed in the food chain but animal products are generally a more concentrated source than plants.

The demand for choline is extremely high during prenatal development. Choline supply is of particular importance for the developing brain because it is required for the biosynthesis of acetylcholine (Ach), a key neurotransmitter for multiple brain functions, including regulation of neuronal proliferation, differentiation, migration, maturation, plasticity, survival, and synapse formation [54–56]. Additionally, choline provides a substrate for the formation of phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin, key elements of neuronal membranes [50, 57, 58]. Choline is also the principal dietary source of methyl groups. As a methyl donor, choline plays a significant role in the regulation of gene expression through epigenetic mechanisms [56, 59–62].

Dietary recommendations for choline were first published in 1998 by the Institute of Medicine [63]. The recommended intake level for adults, 425 and 550 mg/day for women and men, respectively, was based on the estimated level of choline intake required to prevent liver damage [63]. For pregnant women, the adequate choline intake recommendation was increased to 450 mg/day; the 25 mg/day increase during pregnancy was based on fetal and placental accumulation of choline derived primarily from animal models [63]. Several lines of evidence indicate that these current recommendations may not be sufficient to meet the high demands of pregnancy. For example, during pregnancy, maternal choline stores in rodents consuming a normal chow diet become depleted as choline is transported across the placenta to the fetus [64–68]. Moreover, pregnant women consuming choline at a level slightly above current intake recommendations (480 mg/d) have diminished circulating concentrations of several choline metabolites relative to non-pregnant women [69]. Increasing maternal choline intake during pregnancy to 930 mg/d increases biomarkers of choline metabolism but fails to achieve levels seen in non-pregnant women [69]. Furthermore, increased maternal choline intake (480 to 930 mg/d) does not increase the urinary excretion of choline, a water-soluble biomolecule, indicating that higher intake levels do not exceed metabolic requirements [69]. By comparison, folate status biomarkers in this same study did not differ between pregnant and non-pregnant participants, and pregnant women excreted a substantial amount of their total folate intake in urine [70]. Thus, the demand for choline during pregnancy appears to be extremely high and likely exceeds current choline intake recommendations [58].

The most powerful functional evidence that current recommendations for choline intake may not be sufficient for optimal fetal development and lifelong cognitive functioning of offspring is derived from studies using animal models. Numerous studies using rodents demonstrate lasting beneficial effects of increased maternal choline intake during pregnancy on various indices of offspring brain function [71–80]. Specifically, supplementing the maternal diet with additional choline (~4 times higher than found in normal lab chow) enhances memory and spatial cognition in offspring, a benefit that becomes more pronounced with aging [81, 82]. The improved spatial learning/memory in the offspring of choline-supplemented dams likely stems from concomitant changes in septohippocampal circuitry, including (i) the size and shape of MSN/VDB neurons, which correlate with memory function [83, 84]; (ii) altered Ach turnover and choline transporter expression in the septohippocampal circuit [85, 86]; (iii) changes in hippocampal neurogenesis, migration, gene expression, and neurotrophin levels [76, 87–90]; (iv) changes in dendritic fields and spine density in the dentate gyrus and CA1 region of the hippocampus [91]; (v) a lowered threshold for eliciting hippocampal long-term potentiation, a putative change underlying memory formation [92, 93]; (vi) alterations in Ach metabolizing enzymes [71, 94]; (vii) increased hippocampal responsiveness to cholinergic stimulation [94, 95]; and (viii) increased hippocampal progenitor cell proliferation and decreased apoptosis in these cells [55, 77, 87]. In sum, supplementing the maternal diet with additional choline during prenatal development produces lasting, organizational changes in structure and function of the septohippocampal system in ways consistent with the aforementioned improvement in memory function also produced by this early dietary manipulation.

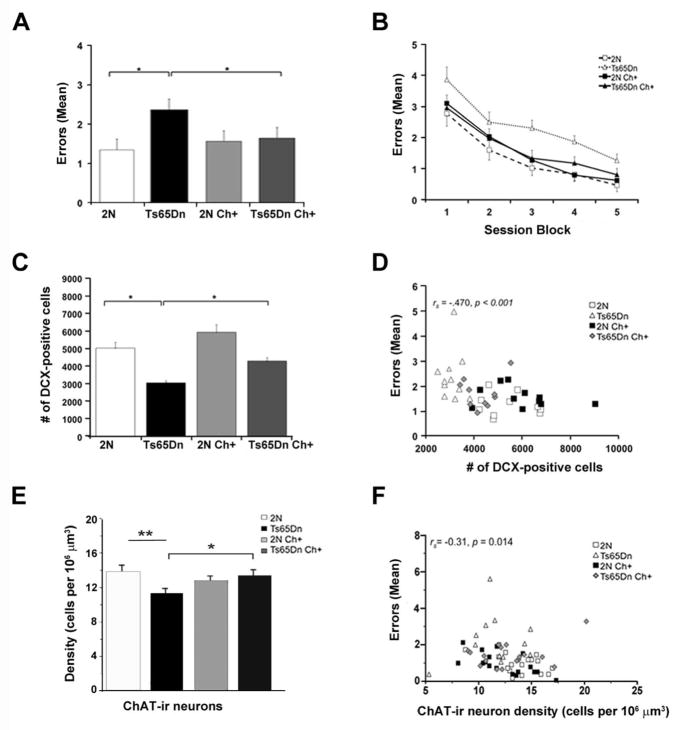

Reports also indicate that supplementing the maternal diet with additional choline during pregnancy of normal rats and mice leads to lasting improvements in attentional function of the offspring [75, 96]. In a signal detection task, which tests focused attention or vigilance, offspring of choline-supplemented dams made significantly more correct responses to the signal trials (Hits) than did control mice (born to dams on a control diet) [96]. Converging evidence for an effect of MCS on attention was also provided using a 5-choice serial reaction time task (5-CSRTT) [75]. In this task, one of five ports is briefly illuminated after a variable delay, and the mouse is rewarded for making a nose-poke into the illuminated port. The unpredictability of the location and time of cue presentation places substantial demands on focused attention and impulse control. Mice born to choline-supplemented dams were significantly faster than controls to master the first attention task, which entailed variable pre-cue delays [75] (Fig. 1A). Taken together, these results suggest a benefit of MCS on attentional function. Although little is known about the neurobiological substrates underlying the improvements in attention seen in offspring of dams supplemented with choline during pregnancy and/or lactation, a plausible mechanism is that MCS improves functioning and/or efficiency of BFCNs located within the NBM/SI that project to the neocortex (e.g., frontal and parietal cortex).

Figure 1.

Effects of MCS on attentional function and emotional reactivity. A: Mean (+/−SE) percentage of correct responses, as a function of the four session blocks (five sessions/block) on the first attention task in which a variable delay was imposed before cue presentation. Although the four groups did not differ in the first session block, differences emerged during the last three session blocks. During these latter 15 sessions, the unsupplemented Ts65Dn mice performed significantly worse than both groups of 2N mice. In contrast, the choline-supplemented Ts65Dn mice did not differ from the unsupplemented 2N mice for any session-block, and performed better than their unsupplemented counterpart mice for Session Blocks 2 and 3. The choline-supplemented 2N mice performed significantly better than their unsupplemented counterparts during Session Block 2. B: Mean (+/−SE) percentage of correct responses as a function of the pre-cue delay, in a task in which both cue duration and pre-cue delay varied across trials. The unsupplemented Ts65Dn mice performed significantly worse than the unsupplemented 2N controls at all delays. In contrast, the choline-supplemented Ts65Dn mice performed significantly better than their unsupplemented counterparts for trials with a 0-s (p < 0.002) or 4-s (p < 0.02) pre-cue delay, and did not differ significantly from the 2N mice for any delay. C: Mean (+/−SE) percentage of trials on which the mice exhibited a long latency (≥ 5 s) to initiate the next trial, referred to as alcove latency (AL), as a function of the outcome of the previous trial (correct or incorrect). No group differences were seen for trials that followed a correct response (PREV CORRECT). However, for trials that followed an error (PREV ERROR), the incidence of trials with a long initiation latency was significantly greater for the unsupplemented trisomic mice than for the two groups of 2N mice and the supplemented trisomic mice. *, p < 0.05, compared with the unsupplemented Ts65Dn mice. Adapted from Moon et al., 2010 [75], and revised images used with permission

Effects of MCS on spatial cognition, hippocampal neurogenesis, and BFCNs

In addition to the beneficial cognitive effects of MCS in normal rats and mice, this early dietary intervention provides lasting neuroprotective effects and attenuates cognitive impairment in a wide variety of rodent disease models including aging [73, 82, 97–99], prenatal alcohol exposure [100–102], epilepsy [103–105], excitotoxicity [106, 107], Rett syndrome [108–111], and notably, DS [74–76, 112].

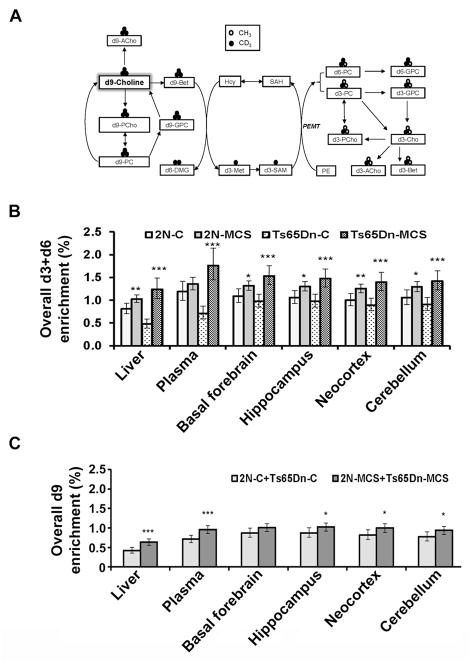

To test the hypothesis that MCS would improve spatial learning and memory in DS, we trained Ts65Dn and normal disomic (2N) littermates in a radial arm water maze (RAWM) containing 6 arms radiating from a center choice area. In this task, the animals must use extra-maze cues to locate a hidden escape platform at the end of one of the arms. Ts65Dn mice born to choline-supplemented dams exhibited lifelong improvements in spatial learning, performing nearly as well as their 2N littermates [74, 76] (Fig. 2A, B). In addition, MCS partially normalized adult hippocampal neurogenesis [76], evidenced by an increased number of doublecortin (DCX) containing cells, a marker for newly born neurons, within the dentate gyrus (Fig. 2C, D). MCS also offered protection to BFCNs in the medial septal nucleus (MSN) [74], which typically exhibits atrophic changes by ~6 months of age [29, 36, 41, 113, 114]. Specifically, choline acetyltransferase-immunoreactive (ChAT-ir) BFCN number and density within the MSN was increased in Ts65Dn offspring born to choline-supplemented dams relative to those born to dams on a control diet [74] (Fig. 2E). Importantly, adult hippocampal neurogenesis and density of BFCNs each correlated significantly with indices of spatial cognition (Fig. 2D, F), supporting the concept that improved spatial cognition produced by maternal choline supplementation may be due to normalization of BFCNs and hippocampal structure and function [74, 76].

Figure 2.

MCS effects on spatial cognition, hippocampal neurogenesis, and BFCN density. A: Average errors per trial (collapsed across sessions) in the Hidden Platform (HP) task of the radial arm water maze (RAWM), a task which requires spatial mapping. Mean errors per trial were significantly higher for the unsupplemented Ts65Dn mice than their 2N counterparts. MCS significantly improved performance for Ts65Dn (p = 0.011). B: Mean errors per trial in the HP task, shown as a function of session-block (3 sessions/block). C: Mean (±SE) number of DCX-positive cells in the dentate gyrus. Unsupplemented Ts65Dn mice displayed significantly fewer DCX-positive cells than 2N mice (p<0.0001). MCS significantly increased the number of DCX-positive cells in Ts65Dn mice (p<0.001). D: The number of DCX-positive cells in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus was a significant predictor of performance in the HP task, an index of spatial learning/memory. E: Ts65Dn mice showed a significantly lower ChAT-ir density relative to 2N mice (p = 0.008). MCS significantly increased the density of ChAT-ir neurons in Ts65Dn mice (p = 0.036). F: Density of ChAT-ir neurons in the MSN was a significant predictor of performance in the HP task. Adapted from Ash et al., 2014 and Velazquez et al., 2013 [74, 76], and revised images used with permission.

Neuroprotection of BFCNs and restoration of adult hippocampal neurogenesis seen in Ts65Dn mice born to choline-supplemented dams may be mediated partially by neurotrophins. Specifically, phenotypic restoration of BFCNs may reflect increased neurotrophin support for these neurons, which atrophy in trisomic mice, at least in part, due to impaired retrograde transport of nerve growth factor (NGF) [29, 36–38, 115]. Interestingly, normal adult rat offspring of choline-supplemented dams exhibit increased brain levels of NGF and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) relative to those born to unsupplemented dams [77, 116]. Moreover, intracerebroventricular administration of NGF reverses atrophy of BFCNs in Ts65Dn mice [38]. Collectively, these data suggest that MCS enhances target-derived neuroprotection of Ts65Dn BFCNs, resulting in a restoration of the functions dependent on these neurons and their projections to the hippocampus and frontal cortex. The normalization of hippocampal neurogenesis in Ts65Dn mice produced by maternal choline supplementation [76] (Fig. 2C, D), may reflect elevated levels of BDNF within the hippocampal formation. BDNF, which has been shown to increase in response to maternal choline supplementation in normal rodents [117], increases survival of newly proliferated neurons [118, 119] and plays an important role in spatial learning and memory [120] (see Iluta and Cuello article in this issue).

These beneficial effects of MCS may be due to organizational brain changes, secondary to choline’s role as the precursor to phosphatidylcholine, a major constituent of cellular membranes, and its role as the precursor of Ach, an important ontogenetic signal [71, 79, 94]. Beneficial MCS effects may also be related to epigenetic modifications with lasting effects on gene expression, secondary to choline’s role as a methyl donor [121–124]. As noted above, choline has a primary role as a methyl donor through the betaine-methionine pathway [50], and alterations in dietary levels of choline during early development can produce lifelong effects on gene expression through DNA methylation and histone modifications [62, 125]. This type of effect has been described in the Latent Early-life Associated Regulation (LEARn) model, which suggests that nutritional and maternal care interventions early in life can modify disease-related and/or disease-causing genes later in life via epigenetic mechanisms [126, 127]. In sum, by playing key roles in several fundamental epigenetic and non-genetic processes, choline availability during prenatal life can exert lifelong effects on brain structure and function.

A question may arise as to whether choline supplementation would have functional effects in the face of widespread fortification of foods with folate, another methyl-nutrient which can also donate methyl groups for DNA methylation. However, it is important to note that folate is only a carrier of methyl groups whereas choline is a source [128]. In a recent choline intervention study involving pregnant women, choline-derived methyl donors were depleted even under conditions of excess folate intake [69, 70]. Although folate and choline can both modulate DNA methylation, folate cannot replace choline as a source of methyl groups during pregnancy, nor can it serve as a substrate for phospholipid and acetylcholine biosynthesis.

Effects of MCS on attention and emotional reactivity

Studies of children with DS reveal deficits in selective and sustained attention, which progressively worsen through adolescence and adulthood [129, 130]. Consistent with human DS research, our studies revealed attentional dysfunction in Ts65Dn mice using the 5-CSRTT task series [47, 75]. Ts65Dn mice committed a high proportion of omission errors (instances of missing the brief visual cue), and were typically off-task (not attending to the ports) during the delay period prior to cue presentation [47, 75].

Subsequent studies by our group demonstrated that supplementing the maternal diet with additional choline substantially improved attention in the Ts65Dn offspring. On the 5-CSRTT attention task series, the performance of the trisomic offspring of choline-supplemented dams was markedly superior to their counterparts born to dams on a control diet [75] (Fig 1 A, B). Notably, the largest improvement was seen for the accuracy of responding, particularly on tasks with relatively brief cues, which place significant demands on focused attention [75]. These tasks also revealed interesting effects of maternal choline supplementation on emotional reactivity of the Ts65Dn offspring. On these tasks, rats and mice generally commit more errors and exhibit longer response latencies on trials, which follow an error than on trials following a correct response. These effects are exacerbated in Ts65Dn mice relative to 2N littermates [47, 75], demonstrating a heightened reaction to the frustration of committing an error and/or not receiving an expected reward. Importantly, maternal choline supplementation significantly reduced the hesitancy of Ts65Dn mice to initiate the next trial following an error [75], indicative of improved regulation of emotion and/or negative affect (Fig. 1C). Little is known about the neural basis of the attentional or affective dysfunction in Ts65Dn mice or the basis of the MCS normalization of these behaviors. It is possible that the reduced density of ChAT-ir and/or pan-neurotrophin receptor p75NTR-ir BFCNs in the NBM/SI seen in these mice [74] plays a role in their attentional dysfunction, based on the evidence that these indices are correlated with attentional performance (unpublished observations). We also found that ChAT-ir neurons within the NBM/SI were significantly larger in older Ts65Dn mice compared to age-matched 2N mice. Interestingly, ChAT-ir neuron size within the NBM/SI neuron was inversely correlated with attentional performance in both 2N and trisomic mice, suggesting that increased size of these neurons is a cholinergic neuroplasticity response associated with attentional dysfunction (see Kelley et al., article in this issue). Collectively, these findings suggest that abnormalities in the basocortical cholinergic system may at least in part underlie the attentional dysfunction of Ts65Dn mice.

Effects of MCS on choline metabolism

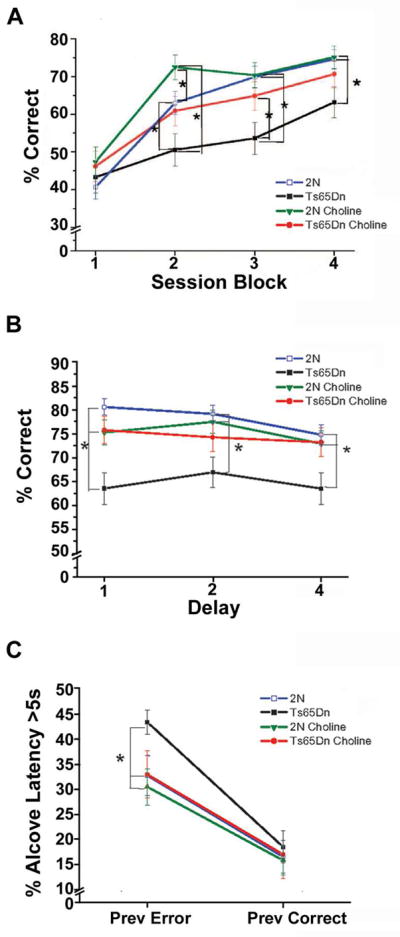

To gain further insight into the mechanism(s) underlying the benefits of maternal choline supplementation, we tested the hypotheses that choline metabolism differs between Ts65Dn mice and their 2N littermates, and that MCS exerts lasting effects on choline metabolism in both Ts65Dn and 2N offspring. Isotopically labeled choline (methyl-d9-choline) was administered in the drinking water of 16-month old adult female trisomic offspring and their 2N littermates born to dams that consumed either a control or choline supplemented diet [57]. Enrichments of d9-choline metabolites derived from intact choline and d3+d6-choline metabolites (Fig. 3A), which are produced when choline-derived methyl groups are used by phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PEMT), were measured in liver, plasma, and in the frontal cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum, and basal forebrain [57]. Both Ts65Dn and 2N adult offspring of choline-supplemented versus choline-unsupplemented dams exhibited 60% greater activity of hepatic PEMT, which functions in de novo choline synthesis and produces phosphatidylcholine (PC) enriched in docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) [57]. Significantly greater enrichment of PEMT-derived d3+d6-metabolites was detected in liver, plasma, and select brain regions including basal forebrain, hippocampus, neocortex, and cerebellum in both genotypes, but to a greater extent in the Ts65Dn adult offspring [57] (Fig. 3B). The offspring of choline-supplemented dams also exhibited higher d9-metabolite enrichments in liver, plasma, and brain regions including hippocampus, neocortex, and cerebellum (Fig. 3C). MCS exerts lasting effects on offspring choline metabolism, including upregulation of the hepatic PEMT pathway and enhanced access of choline and PEMT-PC to brain [57]. These findings indicate that choline metabolism is permanently altered by MCS in trisomic offspring with evidence of preferential partitioning of choline towards brain. Thus, it appears that increasing choline intake by pregnant dams with a trisomic fetus may help normalize their aberrant choline metabolism, which in turn, may contribute to improvement in cognitive function produced by MCS. Organizational effects of MCS may reflect a higher demand for PEMT products (e.g., choline and DHA) among adult Ts65Dn offspring, which is consistent with a higher choline requirement [58, 69]. In summary, increased hepatic supply of PEMT-PC and its associated fatty acids to the brain may be a mechanism whereby maternal choline supplementation induces lifelong cognitive benefits in the Ts65Dn mouse model of DS and AD, as well as in normal offspring. These data generated using the Ts65Dn mice may have a direct translational effect for pregnant women, especially those carrying a DS fetus.

Figure 3.

Effects of MCS on choline metabolites in Ts65Dn mice and 2N littermates. A: Schematic of the metabolism of the orally consumed d9-choline tracer. Intact d9-choline can be used to produce these d9-choline metabolites: d9-acetylcholine (d9-ACho), d9-betaine (d9-Bet), d9-phosphocholine (d9-PCho), d9-glycerophosphocholine (d9-GPC) and d9-phosphatidylcholine (d9-PC). Alternatively, the d9-choline tracer can be oxidized to d9-betaine and one of its three methyl groups can be donated to homocysteine (Hcy) forming d3-methionine (d3-Met) and subsequently d3-S-adenosylmethionine (d3-SAM). A main consumer of SAM is the phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PEMT) pathway which mediates the sequential methylation of phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) to PC (phosphatidylcholine). Under the current labeling strategy, the PEMT pathway generated d3-PC and d6-PC. These PEMT-PC labeled metabolites can then undergo hydrolysis to synthesize other metabolites including d3-ACho, d3-Bet, d3-PCho, and d3-GPC). B: Effects of MCS on overall d3+d6-enrichment in liver, plasma, and brain regions including basal forebrain, hippocampus, neocortex, and cerebellum of adult Ts65Dn and 2N offspring born to unsupplemented (C) versus supplemented (MCS) dams. C: Effects of MCS on overall d9-enrichment in liver, plasma, and brain regions including hippocampus, neocortex, and cerebellum of adult Ts65Dn and 2N offspring born to choline unsupplemented as compared to choline supplemented dams. Key, B, C: *= p≤ 0.05, **= p≤ 0.01, and ***= p≤ 0.001. Adapted from Yan et al., 2014 [57], and revised images used with permission.

Future directions

These findings provide encouragement that maternal choline supplementation may hold significant promise as a prenatal treatment for DS. One caveat to translational inferences, however, is that the Ts65Dn murine model is only trisomic for approximately 88/161 orthologs on HSA21, and also includes approximately 50 triplicated encoded genes that are not triplicated in HSA21 [14]. Although select cognitive and morphological changes seen in Ts65Dn mice are similar to that found in human DS, future MCS investigations are warranted employing newly generated trisomic models, including the Dp16 and Dp16/Dp17/Dp10 mouse lines [25, 131, 132]. Each of these trisomic models has its own limitations, but together they will likely shed greater insight into the potential of MCS as a therapy for DS.

Additional molecular and cellular studies are necessary to delineate the mechanistic basis of the beneficial effects of MCS. For example, microarray or RNA-sequencing studies of BFCNs within the discrete cholinergic neuron subfields may be employed to determine the effect of MCS on select classes of transcripts and/or noncoding RNAs related to cell survival and neuroplasticity. Future studies will likely identify specific genes that exhibit epigenomic marks (DNA and histone methylation) as well as transcripts that display lasting changes in gene expression following choline supplementation. These molecular and cellular data should be correlated with behavioral measures including cognitive endpoints to establish functional links.

Conclusions

In summary, the data reviewed here demonstrate that perinatal choline supplementation attenuates several of the cognitive, affective, and neurochemical alterations seen in Ts65Dn mice, suggesting that MCS deserves consideration as a potential therapy that could reduce the severity of dysfunction in human DS. Although clinical trials are needed to determine whether similar effects are seen in humans with DS, a few anecdotal reports of women increasing their choline intake during pregnancy with a DS fetus are highly encouraging. These reports suggest that these infants reach milestones more similar to normal babies than DS infants without choline supplementation (http://www.delaneyskye.com). In light of growing evidence that all pregnancies would benefit from increased maternal choline intake, this type of recommendation could be given to all pregnant women, thereby providing a very early intervention for DS fetuses, which could also include babies born to mothers who are unaware that they are carrying a DS fetus.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jisook Moon, Ph.D. and Jian Yan, Ph.D. for their support on our collaborative research. We thank Judah Beilin, B.S., and Arthur Saltzman, M.S. for expert technical assistance. Finally, we are grateful to the seminal contributions of Linda Crnic, Ph.D. during the early stages of this research. Supported by NIH grants, HD057564, AG014449, AG043375, AG107617, and the Alzheimer’s Association.

References

- 1.Carothers AD, Hecht CA, Hook EB. International variation in reported livebirth prevalence rates of Down syndrome, adjusted for maternal age. J Med Genet. 1999;36:386–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roizen NJ, Patterson D. Down’s syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1281–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12987-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sherman SL, Allen EG, Bean LH, Freeman SB. Epidemiology of Down syndrome. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2007;13:221–7. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC. Improved national prevalence estimates for 18 selected major birth defects--United States, 1999–2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;54:1301–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartley D, Blumenthal T, Carrillo M, DiPaolo G, Esralew L, Gardiner K, et al. Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease: common pathways, common goals. Alzheimers Dement. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.10.007. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rachidi M, Lopes C. Mental retardation and associated neurological dysfunctions in Down syndrome: a consequence of dysregulation in critical chromosome 21 genes and associated molecular pathways. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2008;12:168–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rachidi M, Lopes C. Molecular and cellular mechanisms elucidating neurocognitive basis of functional impairments associated with intellectual disability in Down syndrome. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2010;115:83–112. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-115.2.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hassold T, Abruzzo M, Adkins K, Griffin D, Merrill M, Millie E, et al. Human aneuploidy: incidence, origin, and etiology. Environ Mol Mutagen. 1996;28:167–75. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2280(1996)28:3<167::AID-EM2>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parker SE, Mai CT, Canfield MA, Rickard R, Wang Y, Meyer RE, et al. Updated National Birth Prevalence estimates for selected birth defects in the United States, 2004–2006. Birth Defects Res A Clinand Mol Teratol. 2010;88:1008–16. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bittles AH, Glasson EJ. Clinical, social, and ethical implications of changing life expectancy in Down syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2004;46:282–6. doi: 10.1017/s0012162204000441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Penrose LS. The incidence of mongolism in the general population. J Ment Sci. 1949;95:685–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.95.400.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chapman RS, Hesketh LJ. Behavioral phenotype of individuals with Down syndrome. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2000;6:84–95. doi: 10.1002/1098-2779(2000)6:2<84::AID-MRDD2>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esbensen AJ. Health conditions associated with aging and end of life of adults with Down syndrome. Int Rev Res Ment Retard. 2010;39:107–26. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7750(10)39004-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sturgeon X, Gardiner KJ. Transcript catalogs of human chromosome 21 and orthologous chimpanzee and mouse regions. Mamm Genome. 2011;22:261–71. doi: 10.1007/s00335-011-9321-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leverenz JB, Raskind MA. Early amyloid deposition in the medial temporal lobe of young Down syndrome patients: a regional quantitative analysis. Exp Neurol. 1998;150:296–304. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mann DM, Yates PO, Marcyniuk B, Ravindra CR. The topography of plaques and tangles in Down’s syndrome patients of different ages. Neuropathol App Neurobiol. 1986;12:447–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1986.tb00053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wisniewski KE, Dalton AJ, Crapper McLachlan DR, Wen GY, Wisniewski HM. Alzheimer’s disease in Down’s syndrome: clinicopathologic studies. Neurology. 1985;35:957–61. doi: 10.1212/wnl.35.7.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cataldo AM, Peterhoff CM, Troncoso JC, Gomez-Isla T, Hyman BT, Nixon RA. Endocytic pathway abnormalities precede amyloid beta deposition in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease and Down syndrome: differential effects of APOE genotype and presenilin mutations. Am J Pathol. 2000;157(1):277–86. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64538-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sendera TJ, Ma SY, Jaffar S, Kozlowski PB, Kordower JH, Mawal Y, et al. Reduction in TrkA-immunoreactive neurons is not associated with an overexpression of galaninergic fibers within the nucleus basalis in Down’s syndrome. J Neurochem. 2000;74(3):1185–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.741185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nixon RA, Cataldo AM. Lysosomal system pathways: genes to neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9(3 Suppl):277–89. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-9s331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mann DM, Yates PO, Marcyniuk B. Alzheimer’s presenile dementia, senile dementia of Alzheimer type and Down’s syndrome in middle age form an age related continuum of pathological changes. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1984;10:185–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1984.tb00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartley SL, Handen BL, Devenny DA, Hardison R, Mihaila I, Price JC, et al. Cognitive functioning in relation to brain amyloid-beta in healthy adults with Down syndrome. Brain. 2014;137:2556–63. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheehan R, Ali A, Hassiotis A. Dementia in intellectual disability. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2014;27:143–8. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Das I, Reeves RH. The use of mouse models to understand and improve cognitive deficits in Down syndrome. Dis Model Mech. 2011;4:596–606. doi: 10.1242/dmm.007716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gardiner KJ. Pharmacological approaches to improving cognitive function in Down syndrome: current status and considerations. Drug Design Devel Ther. 2015;9:103–25. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S51476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rueda N, Florez J, Martinez-Cue C. Mouse models of Down syndrome as a tool to unravel the causes of mental disabilities. Neural Plast. 2012;2012:584071. doi: 10.1155/2012/584071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antonarakis SE, Lyle R, Chrast R, Scott HS. Differential gene expression studies to explore the molecular pathophysiology of Down syndrome. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2001;36:265–74. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00103-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akeson EC, Lambert JP, Narayanswami S, Gardiner K, Bechtel LJ, Davisson MT. Ts65Dn -- localization of the translocation breakpoint and trisomic gene content in a mouse model for Down syndrome. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 2001;93:270–6. doi: 10.1159/000056997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holtzman DM, Santucci D, Kilbridge J, Chua-Couzens J, Fontana DJ, Daniels SE, et al. Developmental abnormalities and age-related neurodegeneration in a mouse model of Down syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(23):13333–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reeves RH, Irving NG, Moran TH, Wohn A, Kitt C, Sisodia SS, et al. A mouse model for Down syndrome exhibits learning and behaviour deficits. Nat Genet. 1995;11(2):177–84. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davisson MT, Schmidt C, Reeves RH, Irving NG, Akeson EC, Harris BS, et al. Segmental trisomy as a mouse model for Down syndrome. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1993;384:117–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gardiner K, Fortna A, Bechtel L, Davisson MT. Mouse models of Down syndrome: how useful can they be? Comparison of the gene content of human chromosome 21 with orthologous mouse genomic regions. Gene. 2003;318:137–47. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00769-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pinter JD, Eliez S, Schmitt JE, Capone GT, Reiss AL. Neuroanatomy of Down’s syndrome: a high-resolution MRI study. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(10):1659–65. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davisson MT, Schmidt C, Akeson EC. Segmental trisomy of murine chromosome 16: a new model system for studying Down syndrome. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1990;360:263–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hunter CL, Bimonte HA, Granholm A-CE. Behavioral comparison of 4 and 6 month-old Ts65Dn mice: Age-related impairments in working and reference memory. Behav Brain Research. 2003;138(2):121–31. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00275-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Granholm AC, Sanders LA, Crnic LS. Loss of cholinergic phenotype in basal forebrain coincides with cognitive decline in a mouse model of Down’s syndrome. Exp Neurol. 2000;161(2):647–63. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holtzman DM, Li YW, DeArmond SJ, McKinley MP, Gage FH, Epstein CJ, et al. Mouse model of neurodegeneration: atrophy of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons in trisomy 16 transplants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(4):1383–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cooper JD, Salehi A, Delcroix JD, Howe CL, Belichenko PV, Chua-Couzens J, et al. Failed retrograde transport of NGF in a mouse model of Down’s syndrome: reversal of cholinergic neurodegenerative phenotypes following NGF infusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(18):10439–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181219298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Granholm AC, Ford KA, Hyde LA, Bimonte HA, Hunter CL, Nelson M, et al. Estrogen restores cognition and cholinergic phenotype in an animal model of Down syndrome. Physiol Behav. 2002;77(2–3):371–85. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00884-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelley CM, Powers BE, Velazquez R, Ash JA, Ginsberg SD, Strupp BJ, et al. Sex differences in the cholinergic basal forebrain in the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathol. 2014;24:33–44. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cataldo AM, Petanceska S, Peterhoff CM, Terio NB, Epstein CJ, Villar A, et al. App gene dosage modulates endosomal abnormalities of Alzheimer’s disease in a segmental trisomy 16 mouse model of Down syndrome. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6788–92. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-17-06788.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen Y, Dyakin VV, Branch CA, Ardekani B, Yang D, Guilfoyle DN, et al. In vivo MRI identifies cholinergic circuitry deficits in a Down syndrome model. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:1453–65. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swanson LW, Cowan WM. Autoradiographic studies of the development and connections of the septal area in the rat. In: DeFrance JF, editor. The Septal Nuclei Advances in Behavioral Biology. Vol. 20. New York: Plenum Press; 1976. pp. 37–63. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Swanson LW, Cowan WM. The connections of the septal region in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1979;186:621–56. doi: 10.1002/cne.901860408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hyde LA, Crnic LS. Age-related deficits in context discrimination learning in Ts65Dn mice that model Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease. Behav Neurosci. 2001;115(6):1239–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rye DB, Wainer BH, Mesulam MM, Mufson EJ, Saper CB. Cortical projections arising from the basal forebrain: a study of cholinergic and noncholinergic components employing combined retrograde tracing and immunohistochemical localization of choline acetyltransferase. Neuroscience. 1984;13(3):627–43. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(84)90083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Driscoll LL, Carroll JC, Moon J, Crnic LS, Levitsky DA, Strupp BJ. Impaired sustained attention and error-induced stereotypy in the aged Ts65Dn mouse: a mouse model of Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease. Behav Neurosci. 2004;118(6):1196–205. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.6.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mesulam MM, Mufson EJ, Levey AI, Wainer BH. Cholinergic innervation of cortex by the basal forebrain: cytochemistry and cortical connections of the septal area, diagonal band nuclei, nucleus basalis (substantia innominata), and hypothalamus in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1983;214(2):170–97. doi: 10.1002/cne.902140206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruparelia A, Pearn ML, Mobley WC. Cognitive and pharmacological insights from the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down syndrome. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2012;22:880–6. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Obeid R. The metabolic burden of methyl donor deficiency with focus on the betaine homocysteine methyltransferase pathway. Nutrients. 2013;5:3481–95. doi: 10.3390/nu5093481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ueland PM. Choline and betaine in health and disease. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2011;34:3–15. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blusztajn JK. Choline, a vital amine. Science. 1998;281:794–5. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5378.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zeisel SH, Blusztajn JK. Choline and human nutrition. Annu Rev Nutr. 1994;14:269–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.14.070194.001413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abreu-Villaca Y, Filgueiras CC, Manhaes AC. Developmental aspects of the cholinergic system. Behav Brain Res. 2011;221(2):367–78. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Albright CD, Tsai AY, Friedrich CB, Mar MH, Zeisel SH. Choline availability alters embryonic development of the hippocampus and septum in the rat. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1999;113(1–2):13–20. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lauder JM, Schambra UB. Morphogenetic roles of acetylcholine. Environ Health Persp. 1999;107:65–9. doi: 10.1289/ehp.99107s165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yan J, Ginsberg SD, Powers B, Alldred MJ, Saltzman A, Strupp BJ, et al. Maternal choline supplementation programs greater activity of the phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PEMT) pathway in adult Ts65Dn trisomic mice. FASEB J. 2014;(24):14–251736. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-251736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jiang X, West AA, Caudil MA. Maternal choline supplementation: a nutritional approach for improving offspring health? Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2014;25:263–73. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jiang X, Yan J, West AA, Perry CA, Malysheva OV, Devapatla S, et al. Maternal choline intake alters the epigenetic state of fetal cortisol-regulating genes in humans. FASEB J. 2012;26:3563–74. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-207894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kovacheva VP, Davison JM, Mellott TJ, Rogers AE, Yang S, O’Brien MJ, et al. Raising gestational choline intake alters gene expression in DMBA-evoked mammary tumors and prolongs survival. FASEB J. 2009;23:1054–63. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-122168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oberlander TF, Weinberg J, Papsdorf M, Grunau R, Misri S, Devlin AM. Prenatal exposure to maternal depression, neonatal methylation of human glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) and infant cortisol stress responses. Epigenetics. 2008;3(2):97–106. doi: 10.4161/epi.3.2.6034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Blusztajn JK, Mellott TJ. Choline nutrition programs brain development via DNA and histone methylation. Cent Nerv Syst Agents Med Chem. 2012;12:82–94. doi: 10.2174/187152412800792706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Institute of Medicine NAoSU. Dietary reference intakes for thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, vitamin B6, folate, vitamin B12, pantothenic acid, biotin and choline. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zeisel SH. Nutrition in pregnancy: the argument for including a source of choline. Int J Womens Health. 2013;5:193–9. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S36610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gwee MC, Sim MK. Free choline concentration and cephalin-N-methyltransferase activity in the maternal and foetal liver and placenta of pregnant rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1978;5:649–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1978.tb00721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gwee MC, Sim MK. Changes in the concentration of free choline and cephalin-N-methyltransferase activity of the rat material and foetal liver and placeta during gestation and of the maternal and neonatal liver in the early postpartum period. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1979;6:259–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1979.tb01247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zeisel SH, da Costa KA. Choline: an essential nutrient for public health. Nutr Rev. 2009;67:615–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00246.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sweiry JH, Yudilevich DL. Characterization of choline transport at maternal and fetal interfaces of the perfused guinea-pig placenta. J Physiol. 1985;366:251–666. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yan J, Jiang X, West AA, Perry CA, Malysheva OV, Devapatla S, et al. Maternal choline intake modulates maternal and fetal biomarkers of choline metabolism in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:1060–71. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.022772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.West AA, Jiang X, Perry C, Yan J, Caudill M. Consumption of a folic acid-containing prenatal vitamin yields supra-physiologic folate status in pregnant and non-pregnant women. FASEB J. 2011;25(31.2) [Google Scholar]

- 71.Meck WH, Smith RA, Williams CL. Organizational changes in cholinergic activity and enhanced visuospatial memory as a function of choline administered prenatally or postnatally or both. Behav Neurosci. 1989;103:1234–41. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.103.6.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Meck WH, Williams CL. Choline supplementation during prenatal development reduces proactive interference in spatial memory. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1999;118:51–9. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Meck WH, Williams CL, Cermak JM, Blusztajn JK. Developmental periods of choline sensitivity provide an ontogenetic mechanism for regulating memory capacity and age-related dementia. Front Integr Neurosci. 2007;1:7. doi: 10.3389/neuro.07.007.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ash JA, Velazquez R, Kelley CM, Powers BE, Ginsberg SD, Mufson EJ, et al. Maternal choline supplementation improves spatial mapping and increases basal forebrain cholinergic neuron number and size in aged Ts65Dn mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;70:32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moon J, Chen M, Gandhy SU, Strawderman M, Levitsky DA, Maclean KN, et al. Perinatal choline supplementation improves cognitive functioning and emotion regulation in the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down syndrome. Behav Neurosci. 2010;124:346–61. doi: 10.1037/a0019590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Velazquez R, Ash JA, Powers BE, Kelley CM, Strawderman M, Luscher ZI, et al. Maternal choline supplementation improves spatial learning and adult hippocampal neurogenesis in the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down syndrome. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;58:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Glenn MJ, Gibson EM, Kirby ED, Mellott TJ, Blusztajn JK, Williams CL. Prenatal choline availability modulates hippocampal neurogenesis and neurogenic responses to enriching experiences in adult female rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:2473–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05505.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Moreno HC, de Brugada I, Carias D, Gallo M. Long-lasting effects of prenatal dietary choline availability on object recognition memory ability in adult rats. Nutr Neurosci. 2013;16:269–74. doi: 10.1179/1476830513Y.0000000055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zeisel SH, Niculescu MD. Perinatal choline influences brain structure and function. Nutr Rev. 2006;64:197–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2006.tb00202.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schulz KM, Pearson JN, Gasparrini ME, Brooks KF, Drake-Frazier C, Zajkowski ME, et al. Dietary choline supplementation to dams during pregnancy and lactation mitigates the effects of in utero stress exposure on adult anxiety-related behaviors. Behav Brain Res. 2014;268:104–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McCann JC, Hudes M, Ames BN. An overview of evidence for a causal relationship between dietary availability of choline during development and cognitive function in offspring. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:696–712. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Meck WH, Williams CL. Metabolic imprinting of choline by its availability during gestation: implications for memory and attentional processing across the lifespan. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27(4):385–99. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Loy R, Heyer D, Williams CL, Meck WH. Choline-induced spatial memory facilitation correlates with altered distribution and morphology of septal neurons. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1991;295:373–82. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-0145-6_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Williams CL, Meck WH, Heyer DD, Loy R. Hypertrophy of basal forebrain neurons and enhanced visuospatial memory in perinatally choline-supplemented rats. Brain Res. 1998;794(2):225–38. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00229-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Blusztajn JK, Cermak JM, Holler T, Jackson DA. Imprinting of hippocampal metabolism of choline by its availability during gestation: implications for cholinergic neurotransmission. J Physiol Paris. 1998;92(3–4):199–203. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4257(98)80010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cermak JM, Holler T, Jackson DA, Blusztajn JK. Prenatal availability of choline modifies development of the hippocampal cholinergic system. FASEB J. 1998;12(3):349–57. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.3.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Albright CD, Friedrich CB, Brown EC, Mar MH, Zeisel SH. Maternal dietary choline availability alters mitosis, apoptosis and the localization of TOAD-64 protein in the developing fetal rat septum. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1999;115(2):123–9. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00057-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Holler T, Cermak JM, Blusztajn JK. Dietary choline supplementation in pregnant rats increases hippocampal phospholipase D activity of the offspring. FASEB J. 1996;10(14):1653–9. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.14.9002559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mellott TJ, Williams CL, Meck WH, Blusztajn JK. Prenatal choline supplementation advances hippocampal development and enhances MAPK and CREB activation. FASEB J. 2004;18:545–7. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0877fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Blusztajn JK, Mellott TJ. Neuroprotective actions of perinatal choline nutrition. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2013;51:591–9. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2012-0635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Meck WH, Williams CA, Cermak JM, Blusztajn JK. Developmental periods of choline sensitivity provide an ontogenetic mechanism for regulating memory capacity and age-related dementia. Front Integr Neurosci. 2008;1(7):1–11. doi: 10.3389/neuro.07.007.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jones JP, Meck WH, Williams CL, Wilson WA, Swartzwelder HS. Choline availability to the developing rat fetus alters adult hippocampal long-term potentiation. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1999;118:159–67. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pyapali GK, Turner DA, Williams CL, Meck WH, Swartzwelder HS. Prenatal dietary choline supplementation decreases the threshold for induction of long-term potentiation in young adult rats. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79(4):1790–6. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.4.1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cermak JM, Blusztajn JK, Meck WH, Williams CL, Fitzgerald CM, Rosene DL, et al. Prenatal availability of choline alters the development of acetylcholinesterase in the rat hippocampus. Dev Neurosci. 1999;21(2):94–104. doi: 10.1159/000017371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Montoya DA, White AM, Williams CL, Blusztajn JK, Meck WH, Swartzwelder HS. Prenatal choline exposure alters hippocampal responsiveness to cholinergic stimulation in adulthood. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2000;123(1):25–32. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(00)00075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mohler EG, Meck WH, Williams CL. Sustained attention in adult mice is modulated by prenatal choline availability. Int J Comp Psychol. 2001;14:136–50. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cheng RK, Scott AC, Penney TB, Williams CL, Meck WH. Prenatal-choline supplementation differentially modulates timing of auditory and visual stimuli in aged rats. Brain Res. 2008;1237:167–75. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Glenn MJ, Kirby ED, Gibson EM, Wong-Goodrich SJ, Mellott TJ, Blusztajn JK, et al. Age-related declines in exploratory behavior and markers of hippocampal plasticity are attenuated by prenatal choline supplementation in rats. Brain Res. 2008;1237:110–23. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.08.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Meck WH, Williams CL. Perinatal choline supplementation increases the threshold for chunking in spatial memory. Neuroreport. 1997;8(14):3053–9. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199709290-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Thomas JD, Abou EJ, Dominguez HD. Prenatal choline supplementation mitigates the adverse effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on development in rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2009;31:303–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Thomas JD, Idrus NM, Monk BR, Dominguez HD. Prenatal choline supplementation mitigates behavioral alterations associated with prenatal alcohol exposure in rats. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2010;88:827–37. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Thomas JD, La Fiette MH, Quinn VRE, Riley EP. Neonatal choline supplementation ameliorates the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on a discrimination learning task in rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2000;22(5):703–11. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(00)00097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Holmes GL, Yang Y, Liu Z, Cermak JM, Sarkisian MR, Stafstrom CE, et al. Seizure-induced memory impairment is reduced by choline supplementation before or after status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res. 2002;48:3–13. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(01)00321-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wong-Goodrich SJ, Mellott TJ, Glenn MJ, Blusztajn JK, Williams CL. Prenatal choline supplementation attenuates neuropathological response to status epilepticus in the adult rat hippocampus. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;30(2):255–69. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yang Y, Liu Z, Cermak JM, Tandon P, Sarkisian MR, Stafstrom CE, et al. Protective effects of prenatal choline supplementation on seizure-induced memory impairment. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-22-j0006.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Guo-Ross SX, Clark S, Montoya DA, Jones KH, Obernier J, Shetty AK, et al. Prenatal choline supplementation protects against postnatal neurotoxicity. J Neurosci. 2002;22:RC195. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-j0005.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Guo-Ross SX, Jones KH, Shetty AK, Wilson WA, Swartzwelder HS. Prenatal dietary choline availability alters postnatal neurotoxic vulnerability in the adult rat. Neurosci Lett. 2003;341(2):161–3. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Nag N, Berger-Sweeney JE. Postnatal dietary choline supplementation alters behavior in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;26:473–80. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Nag N, Mellott TJ, Berger-Sweeney JE. Effects of postnatal dietary choline supplementation on motor regional brain volume and growth factor expression in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Brain Res. 2008;1237:101–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ricceri L, De Filippis B, Fuso A, Laviola G. Cholinergic hypofunction in MeCP2-308 mice: Beneficial neurobehavioural effects of neonatal choline supplementation. Behav Brain Res. 2011;221:623–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ward BC, Kolodny NH, Nag N, Berger-Sweeney JE. Neurochemical changes in a mouse model of Rett syndrome: changes over time and in response to perinatal choline nutritional supplementation. J Neurochem. 2009;108:361–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kelley CM, Powers BE, Velazquez R, Ash JA, Ginsberg SD, Strupp BJ, et al. Maternal choline supplementation differentially alters the basal forebrain cholinergic system of young-adult Ts65Dn and disomic mice. J Comp Neurol. 2014;522:1390–410. doi: 10.1002/cne.23492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Contestabile A, Ciani E. The place of choline acetyltransferase activity measurement in the “cholinergic hypothesis” of neurodegenerative diseases. Neurochem Res. 2008;33:318–27. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9497-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Contestabile A, Fila T, Bartesaghi R, Ciani E. Choline acetyltransferase activity at different ages in brain of Ts65Dn mice, an animal model for Down’s syndrome and related neurodegenerative diseases. J Neurochem. 2006;97(2):515–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Salehi A, Delcroix JD, Belichenko PV, Zhan K, Wu C, Valletta JS, et al. Increased App expression in a mouse model of Down’s syndrome disrupts NGF transport and causes cholinergic neuron degeneration. Neuron. 2006;51(1):29–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sandstrom NJ, Loy R, Williams CL. Prenatal choline supplementation increases NGF levels in the hippocampus and frontal cortex of young and adult rats. Brain Res. 2002;947(1):9–16. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02900-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Glenn MJ, Adams RS, McClurg L. Supplemental dietary choline during development exerts antidepressant-like effects in adult female rats. Brain Res. 2012;1443:52–63. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lee R, Kermani P, Teng KK, Hempstead BL. Regulation of cell survival by secreted proneurotrophins. Science. 2001;294:1945–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1065057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Linnarsson S, Willson CA, Ernfors P. Cell death in regenerating populations of neurons in BDNF mutant mice. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;75:61–9. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00295-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Mizuno M, Yamada K, Olariu A, Nawa H, Nabeshima T. Involvement of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in spatial memory formation and maintenance in a radial arm maze test in rats. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7116–21. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-07116.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Niculescu MD, Craciunescu CN, Zeisel SH. Dietary choline deficiency alters global and gene-specific DNA methylation in the developing hippocampus of mouse fetal brains. FASEB J. 2006;20:43–9. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4707com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Niculescu MD, Yamamuro Y, Zeisel SH. Choline availability modulates human neuroblastoma cell proliferation and alters the methylation of the promoter region of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 3 gene. J Neurochem. 2004;89:1252–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02414.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Waterland RA, Jirtle RL. Transposable elements: targets for early nutritional effects on epigenetic gene regulation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5293–300. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.15.5293-5300.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Zeisel SH. Importance of methyl donors during reproduction. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:673S–7S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26811D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Davison JM, Mellott TJ, Kovacheva VP, Blusztajn JK. Gestational choline supply regulates methylation of histone H3, expression of histone methyltransferases G9a (Kmt1c) and Suv39h1 (Kmt1a), and DNA methylation of their genes in rat fetal liver and brain. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1982–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807651200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Lahiri DK, Maloney B. The “LEARn” (Latent Early-life Associated Regulation) model integrates environmental risk factors and the developmental basis of Alzheimer’s disease, and proposes remedial steps. Exp Gerontol. 2010;45:291–6. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Lahiri DK, Maloney B, Zawia NH. The LEARn model: an epigenetic explanation for idiopathic neurobiological diseases. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:992–1003. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Caudill MA, Gregory JFI, Miller J, Shane B. Folate, choline, vitamin B-12 and vitamin B-6. In: Stipanuk MH, Caudill MA, editors. Biochemical, Physiological and Molecular Aspects of Human Nutrition 3rd edition. St Louis: Elsevier Saunders; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Brown JH, Johnson MH, Paterson SJ, Gilmore R, Longhi E, Karmiloff-Smith A. Spatial representation and attention in toddlers with Williams syndrome and Down syndrome. Neuropsychologia. 2003;41(8):1037–46. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00299-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Clark D, Wilson GN. Behavioral assessment of children with Down syndrome using the Reiss psychopathology scale. Am J Genet A. 2003;118A:210–6. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Yu T, Clapcote SJ, Li Z, Liu C, Pao A, Bechard AR, et al. Deficiencies in the region syntenic to human 21q22.3 cause cognitive deficits in mice. Mamm Genome. 2010;21:258–67. doi: 10.1007/s00335-010-9262-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Yu T, Li Z, Jia Z, Clapcote SJ, Liu C, Li S, et al. A mouse model of Down syndrome trisomic for all human chromosome 21 syntenic regions. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:2780–91. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]