SUMMARY

There is little published evidence regarding whether heparin lock solutions containing preservatives prevent catheter-related infections. However, adverse effects from preservative-containing flushes have been documented in neonates, leading many hospitals to avoid their use altogether. Infection control records from 1982 to 2008 at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (SJCRH) were reviewed regarding the incidence of CRIs and the use of preservative-containing intravenous locks. In addition, the antimicrobial activities of heparin lock solution containing the preservatives parabens (0.165%) or benzyl alcohol (0.9%), and 70% ethanol were examined against Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Bacillus cereus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Candida albicans, and compared with preservative-free saline with and without heparin. Growth was assessed after exposure to test solutions for 0, 2, 4 and 24 h at 35°C. The activities of preservatives were assessed against both planktonic (free-floating) and sessile (biofilm-embedded) micro-organisms using the MBEC Assay. Infection control records revealed two periods of increased catheter-related infections, corresponding with two intervals when preservative-free heparin was used at SJCRH. Heparin solution containing preservatives demonstrated significant antimicrobial activity against both planktonic and sessile forms of all six microbial species. Ethanol demonstrated the greatest antimicrobial activity, especially following short incubation periods. Heparin lock solutions containing the preservatives parabens or benzyl alcohol, and 70% ethanol demonstrated significant antimicrobial activity against both planktonic and sessile micro-organisms commonly responsible for CRIs. These findings, together with the authors’ historical infection control experience, support the use of preservatives in intravenous lock solutions to reduce catheter related infections in patients beyond the neonatal period.

Keywords: Catheter-related infection, Heparin, Preservatives, Ethanol

Introduction

Infection is the most common serious complication associated with the use of central venous catheters. In paediatric patients, there are an average of 5.2 catheter-related infections/1000 days of catheter use.1 Nosocomial catheter-related bloodstream infections (CRBSIs) increase the average duration of hospitalization by approximately 20 days, typically at a cost exceeding $40,000.2, 3

Standard means to prevent CRBSIs are aimed at thwarting pathogens from reaching the interior of the catheter, where they can gain access to the bloodstream. These strategies include sterile barrier precautions,4 skin antisepsis with 2% chlorhexidine,5 use of an antiseptic barrier cap,6 and prompt removal of the catheter when no longer required.7 While these techniques do help to prevent microbial entry into the catheter lumen, some contamination of the catheter lumen is inevitable.8

Intraluminal colonization by microbes is associated with formation of a biofilm;9 a polysaccharide matrix, commonly referred to as ‘slime’,9, 10 secreted by micro-organisms that adhere to the catheter surface. Not all intraluminal colonization leads to a clinically significant bloodstream infection.11 Infection usually occurs when the intraluminal biofilm reaches a threshold density, causing bacteria that are embedded in the biofilm (sessile micro-organisms) to detach and float free (planktonic micro-organisms) from the polysaccharide matrix, moving into the bloodstream.8

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (SJCRH) is the largest paediatric cancer centre in the USA. Unlike most paediatric hospitals, most of the (approximately) 4000 active patients treated at SJCRH have long-term indwelling catheters or subcutaneous ports at some point in their treatment. Consequently, catheter-related infections disproportionately affect overall infection rates at SJCRH compared with other children’s hospitals. Hospital policy for both outpatients and inpatients is for Hickman and Broviac catheters to be flushed with 0.9% saline without preservative or heparin during active use; between periods of use, catheters are locked with 0.9% saline containing heparin 10 units/mL and 0.9% benzyl alcohol. Subcutaneous ports are locked with 0.9% saline containing heparin 10 units/mL and 0.9% benzyl alcohol if use is planned within 24 h, or heparin 100 units/mL and 0.165% parabens if use is not planned for >24 h. In 1985, a period of increased catheter-related infections at SJCRH occurred following an incidental switch to preservative-free heparin lock solution. Extensive culturing of the preservative-free solution did not yield any evidence of contamination, and the episode resolved upon re-instituting the use of a preservative-containing heparin solution. A similar experience was reported at a Canadian hospital when they changed from bacteriostatic heparin catheter locks to sterilized saline catheter locks.12 This led staff at SJCRH to postulate that preservative-containing heparin locks prevented CRBSIs.

Although the use of an ethanol lock has recently been advocated as a treatment for infected intravascular catheters13 and as prophylaxis in immunocompromised patients,14 the routine use of intravenous lock solutions containing preservatives to prevent catheter-related infections has received relatively little consideration.15, 16 The few published reports available related to this topic are contradictory.17 Generally, hospital policies on indwelling catheter care do not address the use of preservatives in heparin lock solutions. However, paediatric hospitals often have policies precluding use of preservative-containing solutions because of the reported adverse effects associated with the use of preservatives in neonates.18 The Infectious Diseases Society of America 2002 Guidelines on the Prevention of Catheter-related Infections noted the lack of data to address the efficacy, if any, of preservative-containing heparin lock solutions.15 The updated 2011 Guidelines recommend antimicrobial lock solutions for patients with recurrent CRBSIs despite optimal technique; this is a Category II recommendation, suggested for implementation, and supported by suggestive clinical or epidemiology studies or a theoretical rationale.16

The present study reviewed SJCRH infection control records from 1982 to 2008 to analyse the frequency of nosocomial CRBSIs in relation to the use of preservative-containing heparin lock solutions. In addition, the study investigated the antimicrobial activity of heparin solution with and without standard preservatives against six micro-organisms that commonly cause catheter-related infections,19 or are particularly problematic when they do cause infection.20 The antimicrobial significance of 70% ethanol was also examined to determine whether this solution might be useful as a catheter lock. The antimicrobial activities of test solutions were assessed in conditions both conducive and non-conducive to biofilm formation.

Methods

Review of infection control information

Infection control records of nosocomial bacteraemias occurring between January 1982 and December 2008 were reviewed. Infection control minutes, which contained data concerning infections that were not classified as hospital acquired, were also reviewed for this time period. The SJCRH Institutional Review Board approved the retrospective review of infection control records regarding catheter-related infections for this study.

Organisms

Isolates of Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Bacillus cereus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Candida albicans were obtained from the American Type Tissue Culture. Isolates were recovered from storage at −70°C on trypticase soy agar (TSA) after overnight incubation at 35°C.

Preservatives and control solutions

Antimicrobial activity was assessed for the following catheter lock solutions: heparin 10 units/mL (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) with no preservative, heparin 10 units/mL with 0.165% parabens (0.15% methylparaben and 0.015% propylparaben; Abraxis Pharmaceutical Products, Schaumburg, IL, USA), heparin 10 units/mL with 0.9% benzyl alcohol (Hospira, Inc., Lake Forest, IL, USA), 70% ethanol in sterile water, and 0.9% saline (Amsino, Nashville, TN, USA) free of preservative and heparin. All solutions were manufactured for intravenous use in humans.

Activity against planktonic micro-organisms (absence of biofilm)

Micro-organisms were suspended to match a 0.5 McFarland standard [~1.5 × 108 colony-forming units (cfu)/mL]. A 200-µL aliquot of 0.5 McFarland suspension was mixed with 2.8 mL trypticase soy broth (TSB) (1:15 dilution) yielding an inoculum of approximately 1 × 107 cfu/mL. This suspension was serially diluted with TSB to achieve a final concentration of approximately 1.0 × 106 cfu/mL. A 0.05-mL aliquot of each microbial suspension was combined with 0.95 mL of each catheter lock solution, yielding a final inoculum concentration of approximately 5 × 104 cfu/mL. Solutions were placed in small, plastic test tubes, capped and incubated for 0, 2, 4 and 24 h at 35°C. For the solutions tested at 0 h, a 0.05-mL aliquot of the microbial suspension was combined with 0.95 mL of 0.9% saline as a growth control. After each time increment, 10-µL aliquots from each test culture and serial 10-fold dilutions using 0.9% saline were inoculated to a separate TSA plate. The plates were incubated for 24 h at 35°C and the colonies were counted. Experiments were performed in duplicate during two separate trials.

Activity against sessile micro-organisms (presence of biofilm)

Micro-organisms were suspended in TSB to match a 1.0 McFarland Standard (3 × 108 cfu/mL). A 1.2-mL aliquot of 1.0 McFarland suspension was combined with 2.4 mL TSB (1:3 dilution) to achieve a final inoculum concentration of approximately 1 × 108 cfu/mL. The MBEC P&G Assay (Innovotech, Edmonton, Canada) was used to grow the biofilm of the test micro-organisms. A 150-µL aliquot of each microbial suspension was added to each well of a 96-well microtitre plate. After the plate was inoculated, the lid containing 96 pegs was carefully inserted into the wells; these pegs provide the surface on which the biofilm can grow. To generate the shear force required for biofilm formation, the inoculated plate was rocked for 8 h in an Elmi Digital Thermostatic Shaker DTS-2 (Riga, Latvia) at 125 revolutions per min and 35°C. The plate was subsequently incubated at 35°C for 16 h.

A 200-µL aliquot of each test preservative and control solution was pipetted into the wells of a second (challenge) microtitre plate. The lid containing pegs on which the biofilm was grown was transferred to the challenge plate and then incubated at 35°C for 2, 4 and 24 h. The biofilm tested at 0 h was not exposed to the test solutions; instead, it was transferred directly to a third (recovery) microtitre plate. At each time increment, wells in a recovery plate were inoculated with 200 µL TSB. The peg lid containing the challenged biofilm was placed carefully into the wells of the recovery plate. To recover the biofilm from pegs, the recovery plate was sonicated with a VWR B500 Series Ultrasonic Cleaner (VWR International, West Chester, PA, USA) for 30 min. The peg lid was discarded, and 10 µL of the recovery solution was transferred to a TSA plate and incubated at 35°C for 24 h. Viable cell counting was accomplished through serial dilutions of recovery solution with 0.9% saline. The experiment was performed in duplicate during two separate trials.

Results

Infection control review

There were no apparent episodes of increased nosocomial bacteraemias among inpatients between January 1982 and December 2008 (assessed monthly). However, two periods of increased bacteraemias that were predominantly classified as originating in the outpatient setting were noted in the infection control minutes during this period. The first episode occurred in late 1985, and included several bacteraemias caused by Stenotrophomonas maltophilia and other Gram-negative species not typically isolated in patients at SJCRH. Cultures of bottles of lock solution, rubber stoppers from vials, sterile wipes, gauze tape, Betadine, antiseptic solutions and other materials yielded no growth. Investigation revealed that the pharmacy started using preservative-free heparin for inpatients and outpatients in September 1985. In January 1986, the pharmacy switched to heparin with preservatives, and letters were sent to the parents of patients with catheters informing them to discard any preservative-free heparin and to use heparin with preservatives. No infections occurred in February 1986, ending the event.

A second cluster of bacteraemias was reported in April 1999, also classified as non-nosocomial as most infections originated in outpatients. An investigation found no evidence of contamination of catheter supplies after extensive culturing, but revealed a recent hospital change to heparin solution in prefilled syringes prepared by a manufacturer. The stock solution used to prepare prefilled syringes was the same solution previously used as the lock solution, but the solution in the prefilled syringes had a negligible amount of preservative since it was diluted 1:1000 with preservative-free heparin before the manufacturer filled the syringes. In this episode, both the total number of catheter-related infections and the number of infections involving more than one microbial species increased significantly compared with the same period in the preceding year (Table I). Isolation of bacterial species not typically seen in the patient population at SJCRH was noted, including Tsukamurella spp., Agrobacterium radiobacter and Pseudomonas paucimobilis. The hospital resumed use of the previously used heparin with preservative, and the pharmacy prepared the heparin syringes. Patients and parents were informed to discard current stocks of prefilled syringes, and there was a marked decrease in catheter-related infections.

Table I.

Comparison of the absolute number of catheter-related infections in a three-month period in 1999 when preservative-free lock solutions were used and the corresponding three months in 1998 when lock solutions containing preservatives were used. Approximately 900 central catheters (60%) and subcutaneous ports (40%) were in use during both periods. Significantly more total infections and multi-organism infections occurred during the period when lock solutions did not contain preservatives, corresponding to approximately 0.26 infections/1000 catheter-days when using preservatives and 0.47 infections/1000 catheter-days when preservatives were not in use.

| Aetiology of infection | March–May 1998 (preservatives) |

March–May 1999 (no preservatives) |

P-value (Fisher’s exact test) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-negative bacteria | 12 | 22 | 0.12 |

| Gram-positive bacteria | 7 | 13 | 0.26 |

| Mixed (Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria) |

0 | 2 | |

| Candida spp. | 2 | 1 | |

| Total infections | 21 | 38 | 0.03 |

| More than one species per infection |

0 | 7 | 0.02 |

Note that these rates are for all outpatient and inpatient catheters, and cannot be directly compared with the standard reporting of nosocomial catheter-related infections for inpatients alone (0.86 infections/1000 catheter-days at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in 2010).

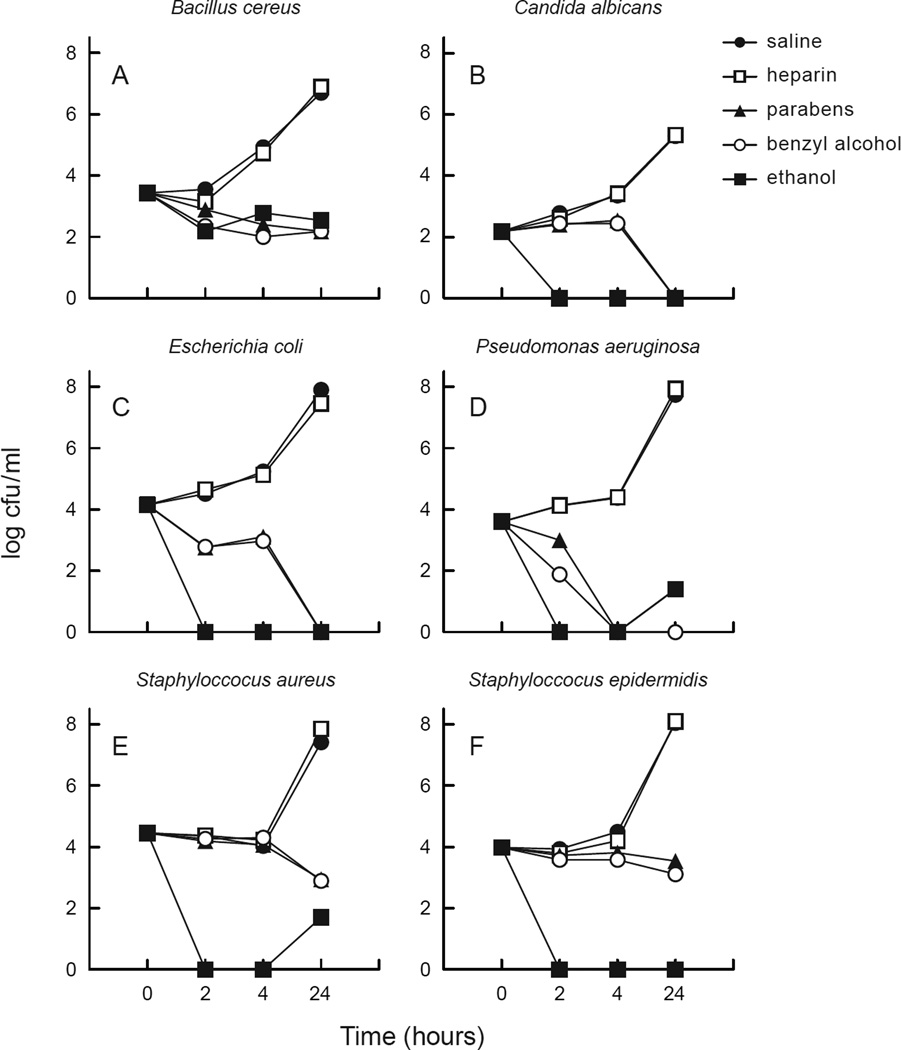

Activity of preservatives against planktonic organisms

Preservative-free heparin did not demonstrate any antimicrobial activity compared with the saline control against any of the six micro-organisms evaluated (Figure 1). In contrast, both heparin containing parabens (0.165%) and heparin containing benzyl alcohol (0.9%) demonstrated significant activity within 4 h of exposure to all six microbial species tested, with most trials showing sterilization after 24 h of exposure. S. aureus and S. epidermidis were slightly more resistant than the other species tested. Micro-organisms were almost completely eradicated within 2 h of exposure to 70% ethanol (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Planktonic organisms challenged against test solutions. (a) Bacillus cereus, (b) Candida albicans, (c) Escherichia coli, (d) Pseudomonas aeruginosa; (e) Staphylococcus aureus, (f) Staphylococcus epidermidis. Parabens, heparin/parabens combination; benzyl, heparin/benzyl combination; cfu, colonu-forming unit. Points on the graph indicate the number of organisms that survived after the indicated exposure time to each test solution.

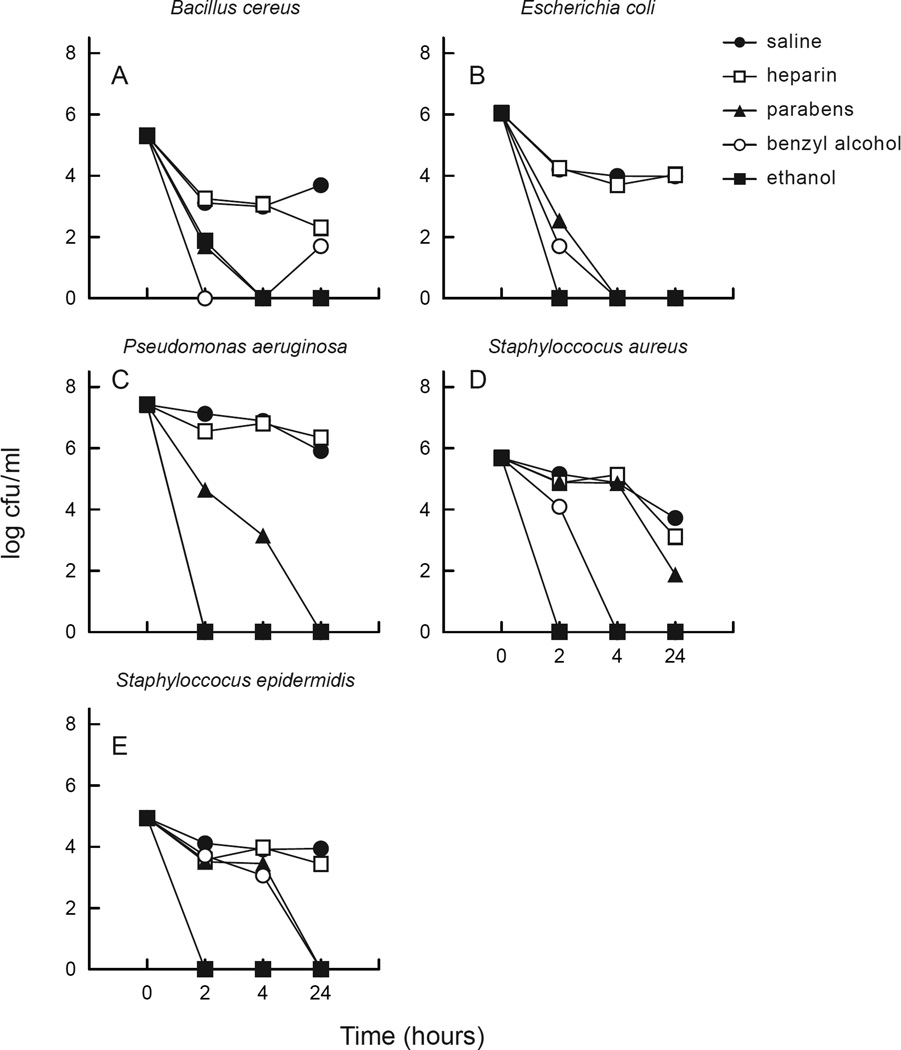

Activity of preservatives against sessile organisms

Saline and heparin reduced the biofilm density of B. cereus, S. epidermidis and S aureus, but had little effect on the biofilm density of E. coli and P. aeruginosa (Figure 2). C. albicans did not produce biofilm or any detectable adherent organisms on multiple attempts with two different strains, and despite trials with increased agitation and incubation periods. Heparin containing parabens or benzyl alcohol demonstrated a significant reduction in sessile organism density compared with saline or heparin after 24 h of exposure. After 4 h of exposure, benzyl alcohol had slightly greater antimicrobial activity than parabens. After exposure to ethanol for ≥2 h, sessile organisms were eliminated (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sessile organisms (embedded in biofilm) challenged against test solutions. (a) Bacillus cereus, (b) Escherichia coli, (c) Pseudomonas aeruginosa; (d) Staphylococcus aureus, (e) Staphylococcus epidermidis. Parabens, heparin/parabens combination; benzyl, heparin/benzyl combination; cfu, colonu-forming unit. Points on the graph indicate the number of organisms that survived after the indicated exposure time to each test solution.

Discussion

Over the past 26 years, preservative-containing heparin lock solutions have been used routinely at SJCRH with the exception of two brief periods. In both instances, increases in catheter-related infections were temporally related to a change to preservative-free heparin solution, and infection control and infectious diseases staff only became aware of the change in lock solution after the clusters of catheter-related infections were noted and investigated. Both occurrences of increased Gram-negative bacterial infections and multi-organism infections were considered most atypical compared with baseline infection patterns. After the first episode, the use of preservative-containing heparin lock solutions became entrenched practice, and in the second episode, the use of a preservative-free solution was initially dismissed as a potential cause when the pharmacy confirmed the use of lock solution containing preservative. However, when the episode persisted in remarkable parallel to the previous occurrence related to use of preservative-free locks, further investigation revealed that the manufacturer of the lock solution had diluted the preservative-containing solution 1000-fold, so a negligible amount of preservative was in the prefilled syringes. The switch to the diluted product coincided with the beginning of the episode. Both occurrences resolved upon re-instituting the use of locks containing full-strength preservatives.

The results of this study indicate that preservatives in heparin lock solutions are active against the micro-organisms most frequently responsible for CRBSIs. The Calgary Biofilm Device,21 commercially available as the MBEC Assay System, was used to simulate the biofilm formation that would be expected along the inner surface of a contaminated intravascular catheter in a reproducible and efficient manner. In addition, organisms were suspended to examine the effects of the test solutions on planktonic organisms that can exist free within the solution locked inside a catheter. The results demonstrated a significant reduction in sessile and planktonic organisms following exposure to commercially available heparin solutions containing benzyl alcohol or parabens for 2–24 h. In addition, 70% ethanol solution was highly effective in reducing or eradicating micro-organisms, and was more effective than the preservatives tested after brief incubation periods. In contrast, heparin solution without preservative permitted rapid growth of all micro-organisms tested.

While the use of a catheter lock solution containing a preservative is a convenient and inexpensive method of infection control, many hospitals have policies discouraging their use. The rejection of preservatives stems from reports of 16 neonatal deaths related to the use of benzyl alcohol (0.9%) in catheter lock solutions.18 Catheter lock solutions containing benzyl alcohol are not recommended for use in neonates, but animal studies suggest that the infusion of as much as 30 mg of 0.9% benzyl is safe in adults.22 Parabens has not been shown to manifest any clinical side-effects when used as a preservative in lock solution, although some studies have shown that parabens can upregulate specific genes in a manner similar to oestradiol.23 These potential risks of adverse effects related to the use of preservatives must be weighed against the potential benefits of preventing CRBSIs, which can be serious and require catheter removal or prolonged antimicrobial therapy.

Dannenberg et al. reported that paediatric oncology patients with CRBSIs and treated with 74% ethanol lock for 20–24 h experienced significantly fewer subsequent infectious relapses compared with patients treated with systemic antibiotics alone.24 Furthermore, the ethanol was well tolerated among the paediatric oncology patients, with mild clinical adverse effects including tiredness, dizziness, nausea and light-headedness.24 Sanders et al. demonstrated fewer catheter-related infections in immunocompromised patients locked with 70% ethanol compared with patients locked with saline containing heparin.14 The present results indicate that 70% ethanol is potentially more effective than benzyl alcohol or parabens, especially for short incubation periods. However, if catheters are accessed frequently, such as in an inpatient setting, care in the volume used to lock the catheter and in complete withdrawal of the lock solution upon each catheter access would be required to avoid exposure of patients to significant amounts of ethanol. Ethanol may be more valuable for treatment of confirmed catheter-related infections using the lock technique and restricting catheter access to assure prolonged dwell times between locks.

To the authors’ knowledge, heparin with preservatives is not commercially available in prefilled syringes, and is only available in multi-dose vials. At SJCRH, heparin syringes are prepared by pharmaceutical services in a sterile environment. An experienced pharmacy technician with appropriate sterile compounding technology can produce 600 syringes in approximately 3 h.

The use of preservative-containing lock solution should be taken into account when evaluating other approaches to preventing catheter-related infections. It is conceivable that antibiotic-impregnated catheters are effective in preventing infection in the absence of preservative-containing locks, but the efficacy of antibiotic use may be diminished or eliminated in the presence of preservative-containing lock solution. Currently, pivotal studies often do not indicate whether the use of preservative-containing locks is standard practice.3 In particular, approaches that could induce antimicrobial resistance should be assessed for efficacy beyond that which may be achieved used preservative-containing locks.

While the data presented in this study are indirect evidence of the efficacy of preservatives in preventing actual catheter-related infections, the microbiological and infection control data taken together are persuasive. Moreover, the overall rate of nosocomial catheter-related infections (0.86 infections/1000 catheter-days for inpatients in 2010) at SJCRH compares favourably with other children’s hospitals, despite the fact that virtually all of the patient population at SJCRH are immunocompromised children. In fact, it would not be feasible to conduct a randomized trial of the use of preservatives at SJCRH because there is consensus that this approach is highly efficacious with minimal risk.

In conclusion, heparin lock solutions containing the preservatives parabens or benzyl alcohol, and 70% ethanol demonstrated significant antimicrobial activity against both planktonic and sessile organisms commonly responsible for catheter-related infections. This study, which includes both infection control and laboratory data, provides evidence that heparin lock solutions containing parabens or benzyl alcohol are an effective prophylaxis against catheter-related infections. Lock solutions with preservatives have minimal risk for adverse effects in patients beyond the neonatal period. The use of preservatives in lock solutions is an inexpensive and underutilized infection control strategy for the prevention of catheter-related infections that does not induce antimicrobial resistance.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources

National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support (Contract Grant No. P30 CA21765) and the American Lebanese and Syrian Associated Charities.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1.Cardo D, Horan T, Andrus M, et al. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System Report, data summary from January 1992 through June 2004, issued October 2004. Am J Infect Control. 2004;32:470–485. doi: 10.1016/S0196655304005425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slonim AD, Kurtines HC, Sprague BM, Singh N. The costs associated with nosocomial bloodstream infections in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2001;2:170–174. doi: 10.1097/00130478-200104000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, et al. An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2725–2732. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raad II, Hohn DC, Gilbreath BJ, et al. Prevention of central venous catheter-related infections by using maximal sterile barrier precautions during insertion. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1994;15:231–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maki DG, Ringer M, Alvarado CJ. Prospective randomised trial of povidone-iodine, alcohol, and chlorhexidine for prevention of infection associated with central venous and arterial catheters. Lancet. 1991;338:339–343. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90479-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menyhay SZ, Maki DG. Preventing central venous catheter-associated bloodstream infections: development of an antiseptic barrier cap for needleless connectors. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36:S174–S175. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Essop AR, Frolich J, Moosa MR, Miller M, Ming RC. Risk factors related to bacterial contamination of indwelling vascular catheters in non-infected hosts. Intensive Care Med. 1984;10:193–195. doi: 10.1007/BF00259436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raad I. Intravascular-catheter-related infections. Lancet. 1998;351:893–898. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10006-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donlan RM, Costerton JW. Biofilms: survival mechanisms of clinically relevant microorganisms. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:167–193. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.2.167-193.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farber BF, Kaplan MH, Clogston AG. Staphylococcus epidermidis extracted slime inhibits the antimicrobial action of glycopeptide antibiotics. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:37–40. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aslam S. Effect of antibacterials on biofilms. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36:S175–S211. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiernikowski JT, Elder-Thornley D, Dawson S, Rothney M, Smith S. Bacterial colonization of tunneled right atrial catheters in pediatric oncology: a comparison of sterile saline and bacteriostatic saline flush solutions. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1991;13:137–140. doi: 10.1097/00043426-199122000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sherertz RJ, Boger MS, Collins CA, Mason L, Raad II. Comparative in vitro efficacies of various catheter lock solutions. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:1865–1868. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.5.1865-1868.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanders J, Pithie A, Ganly P, et al. A prospective double-blind randomized trial comparing intraluminal ethanol with heparinized saline for the prevention of catheter-associated bloodstream infection in immunosuppressed haematology patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:809–815. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Grady NP, Alexander M, Dellinger EP, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2002;23:759–769. doi: 10.1086/502007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e162–e193. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steczko J, Ash SR, Nivens DE, Brewer L, Winger RK. Microbial inactivation properties of a new antimicrobial/antithrombotic catheter lock solution (citrate/methylene blue/parabens) Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:1937–1945. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gershanik J, Boecler B, Ensley H, McCloskey S, George W. The gasping syndrome and benzyl alcohol poisoning. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:1384–1388. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198211253072206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mermel LA, Farr BM, Sherertz RJ, et al. Guidelines for the management of intravascular catheter-related infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:1249–1272. doi: 10.1086/320001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubin LG, Shih S, Shende A, Karayalcin G, Lanzkowsky P. Cure of implantable venous portassociated bloodstream infections in pediatric hematology-oncology patients without catheter removal. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:102–105. doi: 10.1086/520135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ceri H, Olson ME, Stremick C, Read RR, Morck D, Buret A. The Calgary Biofilm Device: new technology for rapid determination of antibiotic susceptibilities of bacterial biofilms. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1771–1776. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1771-1776.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kimura ET, Darby TD, Krause RA, Brondyk HD. Parenteral toxicity studies with benzyl alcohol. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1971;18:60–68. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(71)90315-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Darbre PD, Harvey PW. Paraben esters: review of recent studies of endocrine toxicity, absorption, esterase and human exposure, and discussion of potential human health risks. J Appl Toxicol. 2008;28:561–578. doi: 10.1002/jat.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dannenberg C, Bierbach U, Rothe A, Beer J, Korholz D. Ethanol-lock technique in the treatment of bloodstream infections in pediatric oncology patients with broviac catheter. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;25:616–621. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200308000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]