Abstract

The myelin sheaths wrapped around axons by oligodendrocytes are crucial for brain function. In ischaemia myelin is damaged in a Ca2+-dependent manner, abolishing action potential propagation1,2. This has been attributed to glutamate release activating Ca2+-permeable NMDA receptors2-4. Surprisingly, we now show that NMDA does not raise [Ca2+]i in mature oligodendrocytes and that, although ischaemia evokes a glutamate-triggered membrane current4, this is generated by a rise of extracellular [K+] and decrease of membrane K+ conductance. Nevertheless, ischaemia raises oligodendrocyte [Ca2+]i, [Mg2+]i and [H+]i, and buffering intracellular pH reduces the [Ca2+]i and [Mg2+]i increases, showing that these are evoked by the rise of [H+]i. The H+-gated [Ca2+]i elevation is mediated by channels with characteristics of TRPA1, being inhibited by ruthenium red, isopentenyl pyrophosphate, HC-030031, A967079 or TRPA1 knockout. TRPA1 block reduces myelin damage in ischaemia. These data suggest TRPA1-containing ion channels as a therapeutic target in white matter ischaemia.

Ischaemia blocks action potential propagation through myelinated axons1. Electron microscopy2 and imaging of dye-filled oligodendrocytes3 show ischaemia-evoked Ca2+-dependent damage to the capacitance-reducing myelin sheaths, which causes loss of action potential propagation. Glutamate receptor block reduces myelin damage and action potential loss2-7, and glutamate evokes a membrane current in oligodendrocytes mediated by AMPA/kainate and NMDA receptors2-4. Thus, oligodendrocyte damage is thought to be excitotoxic: as for neurons in ischaemia, a rise of glutamate concentration8 caused by reversal of glutamate transporters in oligodendrocytes and axons9,10 activates receptors that raise2 oligodendrocyte [Ca2+]i, thus damaging the cells.

However, although AMPA/KA and NMDA receptors regulate oligodendrocyte precursor development11,12, these receptors are down-regulated as the cells mature13-15. How can mature oligodendrocytes be damaged excitotoxically, if they express low levels of glutamate receptors? To investigate how oligodendrocyte [Ca2+]i is raised in ischaemia, we characterised ischaemia-evoked membrane current and [Ca2+]i changes in cerebellar white matter oligodendrocytes.

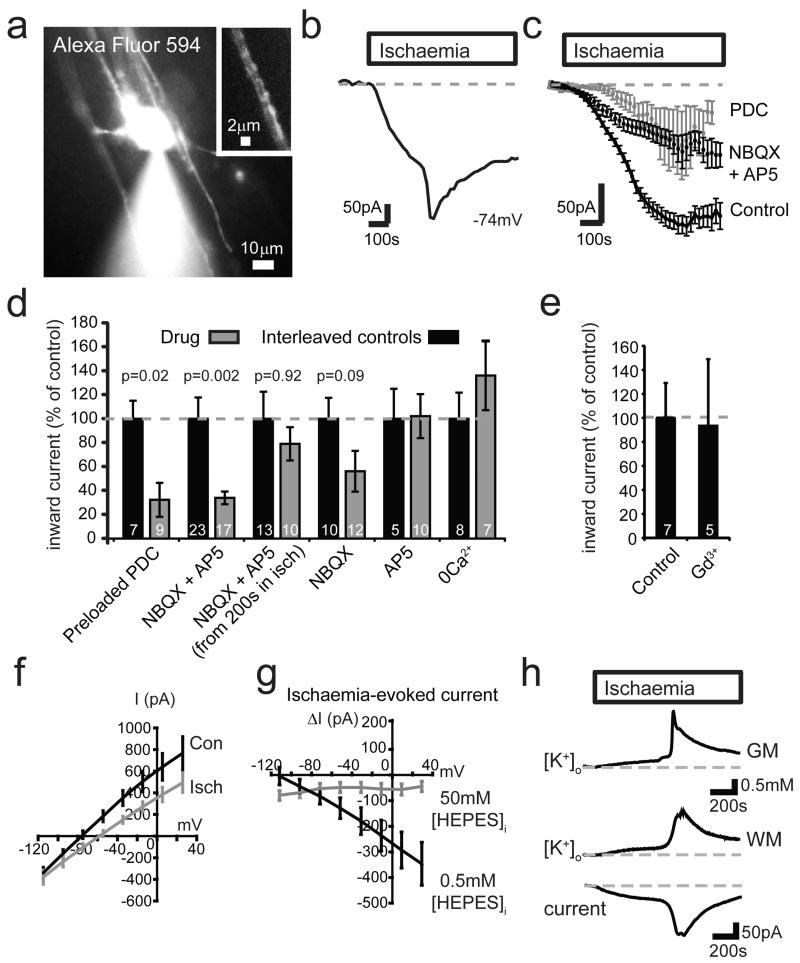

Solution mimicking ischaemia (see Methods) evoked an increasing inward current in oligodendrocytes (Fig. 1a-b), often with a faster phase that was obscured when responses in many cells were averaged (Fig. 1c). When applied from before the ischaemia, NBQX and D-AP5 reduced the ischaemia-evoked current by 66% (Fig. 1c-d), while mGluR block had no effect (Ext. Data Fig. 1a). Preloading for 30 mins with the glutamate transport blocker PDC, to prevent ischaemia-evoked glutamate release by reversal of transporters in the white9 and grey16 matter, also reduced the inward current (by 68%, Fig. 1c-d), while blocking other candidate release mechanisms had no effect (Ext. Data Fig. 1a). Thus, glutamate release by reversed uptake helps to trigger the ischaemia-evoked current. Strikingly, however, current flow through glutamate receptors generates only a small fraction of the sustained inward current evoked by ischaemia, since applying NBQX and D-AP5 from 200 sec after ischaemia had started produced only a non-significant 21% suppression of the ischaemia-evoked inward current (Fig. 1d).

Figure 1. Ischaemia evokes an inward current in oligodendrocytes by altering K+ fluxes.

a Whole-cell clamped oligodendrocyte. Inset: Alexa dye in processes around an axon. b Ischaemia-evoked membrane current in single cell. c Current in 179 control cells, 12 cells exposed to 25 μM NBQX and 200 μM D-AP5 from before ischaemia, or 9 cells preloaded16 with 1 mM PDC. d Current (normalised to interleaved control cells) from 8-10 mins after start of ischaemia in cells preloaded with PDC, exposed to NBQX+AP5 throughout ischaemia or from 200 sec after ischaemia starts, or exposed to NBQX or AP5 alone or to zero-Ca2+ solution (with 50 μM EGTA) throughout ischaemia. Mann-Whitney p values compare with control cells; cell numbers shown on bars. e Effect of Gd3+ (100 μM) on ischaemia-evoked current at 8-10 mins (Mann-Whitney p=0.83). f I-V relation of 10 cells before and after 5 mins ischaemia (10 mM HEPES internal). g Ischaemia-evoked current in 10 cells with 0.5 mM and 9 cells with 50 mM internal HEPES. Ischaemia decreased cell conductance by 2.1±0.7 nS near −70 mV in 11 cells using 10 mM, and by 2.3±0.6 nS in 10 cells using 0.5 mM, internal HEPES; 50 mM HEPES abolished the decrease (Fig. 3i). h Change of [K+]o in grey matter (GM, granule cell layer), and in white matter (WM, different slice) with simultaneously recorded oligodendrocyte current. Error bars, s.e.m.

In neurons, an ischaemia-evoked inward current triggered by glutamate release, but maintained by non-glutamatergic mechanisms, generates the “Extended Neuronal Depolarization” (END) that evokes neuronal death17. However, the ischaemia-evoked current in oligodendrocytes was not prevented by removing external Ca2+, nor by gadolinium, which both block the END17 (Fig. 1d-e), implying a different mechanism maintains the inward current triggered by glutamate.

Unlike in neurons, where ischaemia evokes a conductance increase mediated by ionotropic glutamate receptors16, ischaemia decreased the conductance of oligodendrocytes (Fig. 1f-g). The suppressed current reversed below the K+ reversal potential (EK=−104 mV), at −121 mV with 10 mM (Fig. 1f, Ext. Data Fig. 1e) and −118 mV with 0.5 mM HEPES (Fig. 1g). This is expected if ischaemia decreases the membrane K+ conductance, while [K+]o rises (due to Na+/K+ pump inhibition throughout the slice) which increases the inward current at all potentials (see Ext. Data Fig. 1b-d; Suppl. Information). K+-sensitive electrodes showed that [K+]o in the white matter initially rose slowly during ischaemia, but then increased more abruptly, in parallel with the membrane current (Fig. 1h). The peak rise was 2.35±0.13 mM (n=12) in the white matter and 2.48±0.35 mM (n=4) in the adjacent grey matter (where it reflects the anoxic depolarization of neurons18). The conductance decrease described above produced 32%, while the [K+]o rise produced 68%, of the inward current in oligodendrocytes at −74mV (see Suppl. Information). Thus, changes in K+ fluxes generate the ischaemia-evoked inward current.

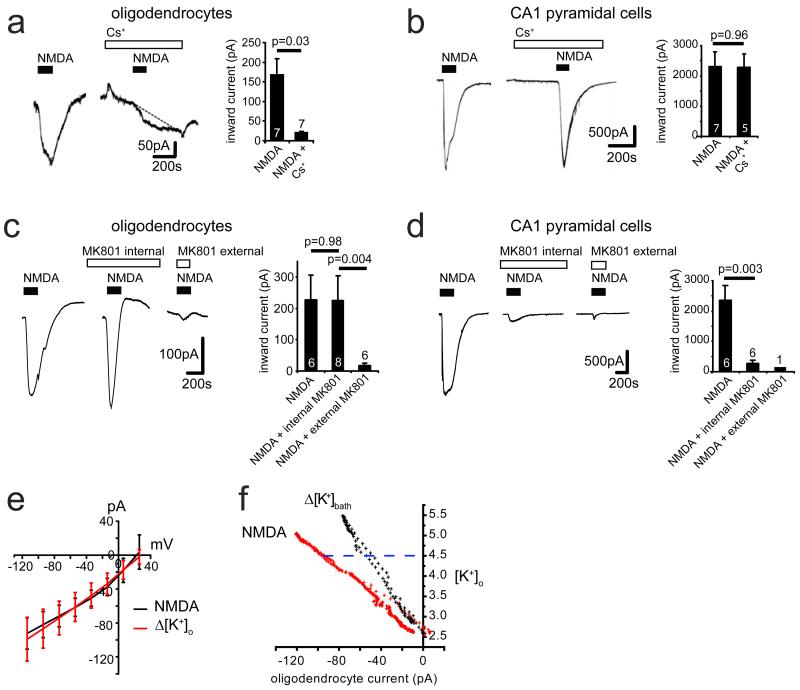

Could part of the NMDA-evoked inward current in oligodendrocytes4 also reflect a [K+]o rise? Extracellular Cs+ blocked the NMDA-evoked current while intracellular MK-801 had no effect (Ext. Data Fig. 2a-d), suggesting most of the NMDA-evoked current is generated by [K+]o rising, rather than by oligodendrocyte NMDA receptors. Applying NMDA or raising [K+]o, and correlating the resulting inward current with the [K+]o rise occurring (see Supplementary Information; Ext. Data Fig. 2e-f), we found that at least 49% of the NMDA-evoked current was attributable to the [K+]o rise that it produced. Since mature oligodendrocytes express few NMDA receptors13-15, this presumably reflects NMDA depolarizing neurons or astrocytes in the slice and releasing K+.

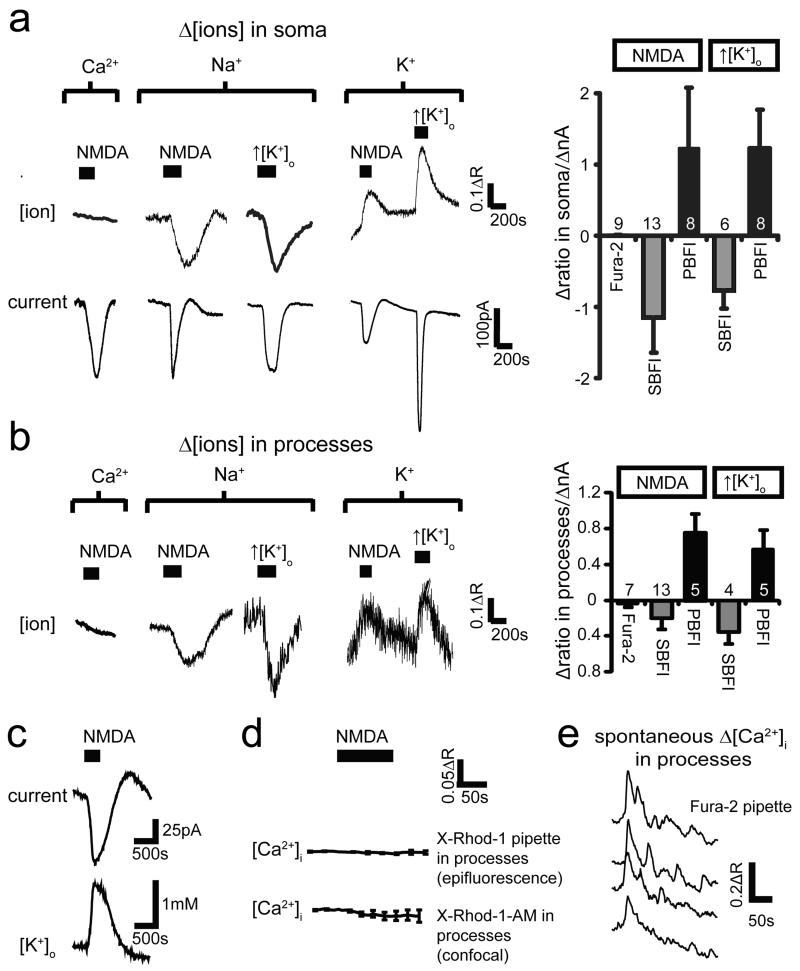

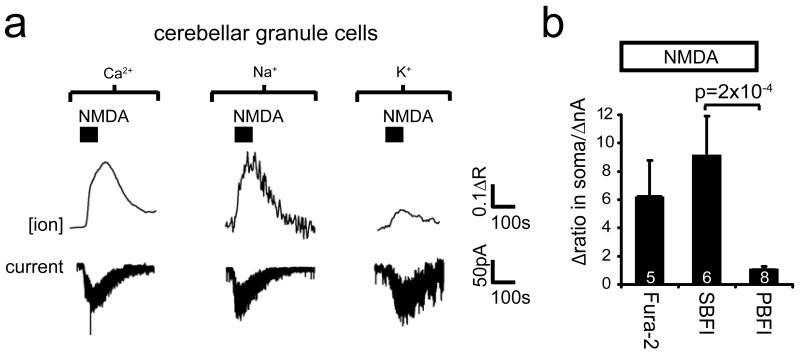

These data challenge the idea2-5 that, during ischaemia, NMDA receptors in mature oligodendrocytes generate a prolonged calcium influx which damages the cells. We therefore investigated the ion concentration changes evoked in oligodendrocytes by activation of NMDA receptors, using Ca2+-, Na+- and K+-sensitive dyes loaded into cells from the pipette. When 100 μM NMDA was applied to whole-cell clamped cerebellar granule neurons at −74 mV, as expected it evoked an inward current, and raised [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i (Ext. Data Fig. 3). In contrast, although NMDA evoked an inward current in oligodendrocytes, it generated no [Ca2+]i or [Na+]i elevation, indeed [Na+]i decreased after applying NMDA (Fig. 2a). NMDA raised [K+]i however. Similar concentration changes were seen at the soma (Fig. 2a) and in the internodal processes where NMDA receptors may be located2-4 (Fig. 2b). Like NMDA, raising [K+]o lowered [Na+]i (Fig. 2a, b). A likely explanation is that NMDA raises [K+]o (Fig. 2c), which decreases [Na+]i by activating the Na+/K+ pump.

Figure 2. NMDA does not elevate [Ca2+]i in oligodendrocytes.

a-b Oligodendrocyte membrane current (lower traces, a) and background-subtracted fluorescent dye ratio (R, see Methods, concentration increases are upwards for all dyes) when measuring [Ca2+]i with Fura-2, [Na+]i with SBFI, and [K+]i with PBFI; 100μM NMDA was applied, or [K+]o was raised from 2.5 to 5 mM, with fluorescence measured in soma (a) or myelinating processes (b). Right panels: peak fluorescence change normalised to evoked current (number of cells on bars). c NMDA-evoked current and simultaneously recorded [K+]o. d Measuring [Ca2+]i with X-Rhod-1, loaded from pipette or as an acetoxymethyl ester2, reveals no NMDA-evoked [Ca2+]i rise. e Spontaneous [Ca2+]i transients in four myelinating processes confirm Fura-2 is working. Error bars, s.e.m.

The absence of a rise of [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i is surprising if oligodendrocytes express NMDA receptors2-4. Conceivably NMDA receptors might pass ions into a compartment in their myelinating processes which only certain Ca2+-sensing dyes such as X-Rhod-1 can access2. However, whether X-Rhod-1 was loaded as an acetoxymethyl ester2 or from the pipette, we observed no NMDA-evoked change of [Ca2+]i in the myelinating processes (Fig. 2d). Nevertheless, we could detect spontaneous [Ca2+]i rises propagating through myelinating processes in 55% of oligodendrocytes (Fig. 2e).

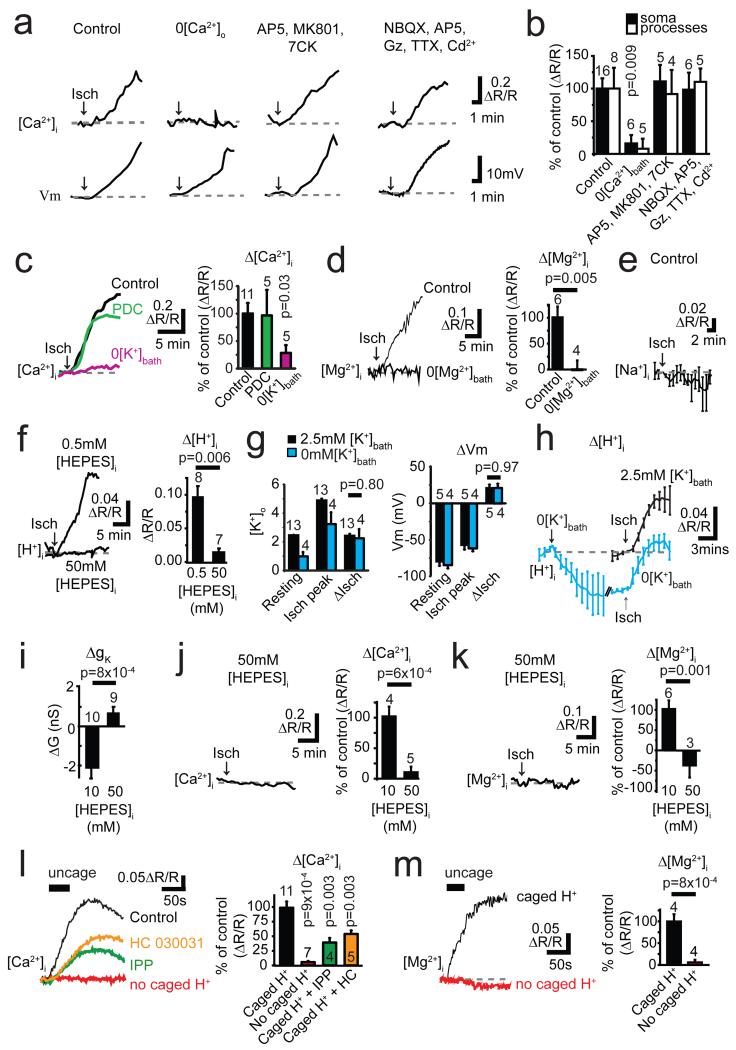

To confirm that ischaemia raises2 oligodendrocyte [Ca2+]i, we loaded the Ca2+-sensing dye Fluo-4 (with Alexa Fluor 594, for ratiometric imaging) into oligodendrocytes from a whole-cell pipette (in current-clamp mode, allowing voltage changes, in case voltage-gated Ca2+ channels raise [Ca2+]i). Ischaemia increased [Ca2+]i in the soma and processes over ~10 mins. This was abolished if extracellular calcium was removed (Fig. 3a-b), and reduced by removing external K+ (Fig. 3c), suggesting that the ischaemia-evoked [K+]o rise promotes calcium entry from the extracellular solution. However, contradicting the earlier report2, blocking NMDA receptors with MK-801, D-AP5 and 7-chloro-kynurenate, or blocking NMDA and AMPA/KA receptors with NBQX and D-AP5 while blocking voltage-gated Na+ and Ca2+ channels and GABAA receptors, did not prevent the [Ca2+]i rise (Fig. 3a-b). Similarly, when PDC-preloading reduced transporter-mediated glutamate release, the [Ca2+] rise was unaffected (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3. Ischaemia evokes a [Ca2+]i and [Mg2+]i rise gated by internal protons.

a Ratiometric Fluo-4/Alexa-Fluor-594 signals ([Ca2+]i) and membrane potential (Vm) in oligodendrocytes exposed to ischaemia (starting at arrow), or ischaemia in zero [Ca2+]o, or with drugs at concentrations (μM): AP5 50, MK-801 50, 7-chlorokynurenate (7CK) 100, NBQX 25, GABAzine (Gz) 20, TTX 1, Cd2+ (to block Ca2+ channels) 100. b Mean data from experiments like a (cell numbers on bars; p values compare with soma or process control values). c Data as in a after PDC-preloading or in 0 mM [K+]bath. d Ischaemia-evoked [Mg2+]i rise monitored with Mag-Fluo-4 in normal and Mg2+-free solution. e Ischaemia-evoked [Na+]i change monitored with SBFI (6 cells). f Ischaemia-evoked [H+]i rise monitored with BCECF with 0.5 mM and 50 mM internal HEPES (p from Mann-Whitney test). g [K+]o and oligodendrocyte membrane potential (Vm) with 2.5 or 0 mM [K+]bath, before (Resting) and during ischaemia (Isch peak), and change produced by ischaemia (ΔIsch). h Effect of removing K+ from bath solution on [H+]i in control conditions (relative to value at start of K+ removal), and [H+]i increase evoked by ischaemia (normalised to value at start of ischaemia) with 2.5 or 0 mM bath K+. i High [HEPES]i blocks ischaemia-evoked decrease of membrane conductance. j-k Ischaemia-evoked rise of [Ca2+]i (j) and [Mg2+]i (k) are inhibited with 50 mM internal HEPES. l-m Uncaging H+ with light (bars) raises [Ca2+]i (l, an effect reduced by 200 μM IPP or 80 μM HC-030031) and [Mg2+]i (m), but not when caged H+ is omitted from the pipette. P values in l from Mann-Whitney tests. Error bars, s.e.m.

Similar experiments using a Mg2+-sensitive dye revealed that [Mg2+]i also rises in ischaemia (Fig. 3d). This was not due to ATP breakdown, which releases Mg2+, since the [Mg2+]i rise was abolished by removing extracellular Mg2+ (Fig. 3d) implying that Mg2+ enters across the cell membrane. Surprisingly, ischaemia did not raise [Na+]i (Fig. 3e). Thus ischaemia activates a membrane conductance that allows entry of divalent ions.

Seeking an agent that decreases membrane K+ conductance and activates Ca2+ entry, we measured the ischaemia-evoked pH change in oligodendrocytes. Ischaemia increased [H+]i on the timescale seen for [Ca2+]i (Fig. 3f). A similar (but smaller) [H+]i rise was evoked by elevated [K+]o or NMDA (Ext. Data Fig. 4a), suggesting that the ischaemia-evoked [K+]o rise partly generates this pH change. To investigate this, we removed external K+, which reduced the [K+]o in the slice from 2.46±0.02 mM (n=13) to 0.99±0.3 mM (n=4) (Mann-Whitney p=0.001, Fig. 3g), and hyperpolarized the resting potential by 7 mV (−84.0±4.7 to −77.2±4.3 mV, n=4, p=0.002, paired t-test, Fig. 3g). The ischaemia-evoked [K+]o rise and depolarization were unaffected by K+ removal (Fig. 3g), but the [H+]i initially and during ischaemia were reduced (Fig. 3h). These data and those in Fig. 3c suggest that the ischaemia-evoked [K+]o rise helps to acidify the cell, which in turn evokes Ca2+ entry.

Using an internal solution containing 50 mM HEPES, the ischaemia-evoked rise of [H+]i was, as expected, greatly reduced (Fig. 3f). This prevented the decrease of K+ conductance (Figs. 1g, 3i), consistent with intracellular acidity suppressing activity of tonically-active K+ channels19. Strikingly, however, buffering intracellular pH also prevented the ischaemia-evoked rise of [Ca2+]i and [Mg2+]i (Fig. 3j-k), implying that the ischaemia-evoked [H+]i rise activates entry of these cations into the cell. Consistent with this, uncaging protons in oligodendrocytes raised [Ca2+]i and [Mg2+]i (Fig. 3l-m).

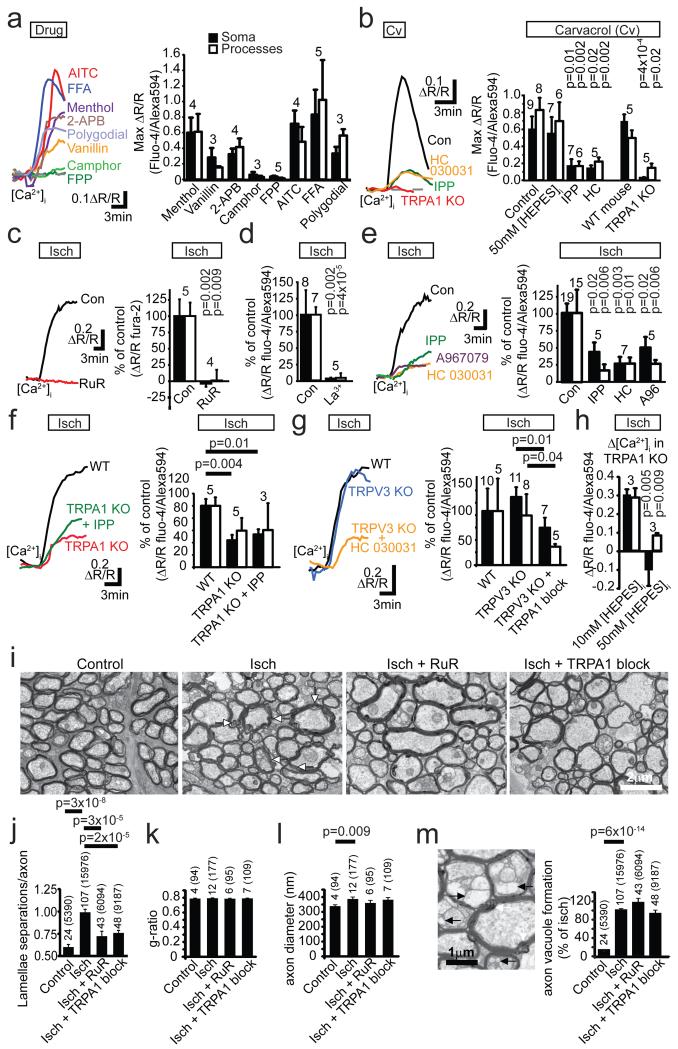

Few channels allow entry of Ca2+ and Mg2+ better than Na+, but many TRP channels share this property20 (and TRP channel activation can cause ischaemic damage to neurons21 and astrocytes22). Of these channels, only20,23,24 TRPA1 and TRPV3 are known to be activated by intracellular H+, so we applied modulators of these channels and examined the effect on oligodendrocyte [Ca2+]i (TRP agonist and blocker specificity are discussed in Supplementary Information). The TRPA1/TRPV3 blocker isopentenyl pyrophosphate25 (IPP) and the TRPA1 blocker26 HC-030031 slowed and reduced the [Ca2+]i rise evoked by uncaging H+ in the cell (Fig. 3l). The TRPA1/TRPV3 agonists20,27 menthol, vanillin, carvacrol (Cv) and 2-APB all raised [Ca2+]i in oligodendrocyte somata and myelinating processes, as did the TRPA1 agonists27 AITC, polygodial and flufenamic acid, while the TRPV3 agonists20,27 camphor and farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) did not (Fig. 4a-b). Thus, TRPA1 subunit-including channels contribute to these responses, but TRPV3 channels are not needed. The carvacrol-evoked rise of [Ca2+]i was reduced by HC-030031 which blocks TRPA1 but not TRPV326, by the TRPA1/TRPV3 blocker isopentenyl pyrophosphate25 (IPP), and by TRPA1 knock-out (Fig 4b), again implying involvement of TRPA1 channels. It was unaffected by buffering [H+]i (Fig. 4b), consistent with Ca2+ entry via TRPA1 being downstream of the [H+]i rise, as seen with H+ uncaging (Fig. 3l).

Figure 4. TRPA1 mediates ischaemic Ca2+ accumulation and myelin damage.

a Δ[Ca2+]i to TRPA1/TRPV3 agonists (mM) (menthol 2, vanillin 1, 2-APB 2), TRPV3 agonists (camphor 2, FPP 0.5) and TRPA1 agonists (AITC 0.5, FFA 1, polygodial 0.2). b Δ[Ca2+]i to TRPA1/TRPV3 agonist carvacrol (2 mM, in 1 μM TTX) is inhibited by TRPA1/TRPV3 antagonist isopentyl pyrophosphate (IPP, 200 μM, Mann-Whitney test on soma), TRPA1 antagonist HC-030031 (80 μM), and TRPA1 knock-out (Mann-Whitney test on processes), but not by 50 mM internal [HEPES] (p values compare with control). c-d Ischaemia-evoked Δ[Ca2+]i is blocked by Ruthenium Red (RuR, 10 μM) (c), and La3+ (d, 1 mM, using HEPES-buffered external, Mann-Whitney test on soma). e Block of ischaemia-evoked Δ[Ca2+]i by TRPA1/TRPV3 blocker IPP (200 μM) and TRPA1 blockers HC-030031 (80 μM) and A967079 (10 μM). Mann-Whitney p values compare with control. f Ischaemia-evoked Δ[Ca2+]i in wild-type mice, with TRPA1 knocked out (p=0.07 for processes) and with TRPA1/TRPV3 blocker IPP (200 μM) also present. g Ischaemia-evoked Δ[Ca2+]i in wild-type mice, with TRPV3 knocked out and with TRPA1 blockers HC-030031 (80 μM) and A967079 (10 μM) also present (Mann-Whitney p values). h Ischaemia-evoked Δ[Ca2+]i in TRPA1 KO with 10 and 50 mM internal [HEPES]. i EM showing control optic nerves and myelin decompaction (white arrows) after 60 mins ischaemia or ischaemia in RuR (10 μM), or A967079 (10 μM) and HC-030031 (80 μM) together (TRPA1 block). j-m Lamella separations (j), g ratio (k), axon diameter (l) and axon vacuoles (m: EM shows vacuoles (black arrows) within axon and periaxonal space) in control, ischaemia alone or ischaemia with RuR (10 μM) or with A967079 (10 μM) and HC-030031 (80 μM) (TRPA1 block). Bar numbers are ‘images (axons)’. P values for j-m from Mann-Whitney tests except l from Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Error bars, s.e.m.

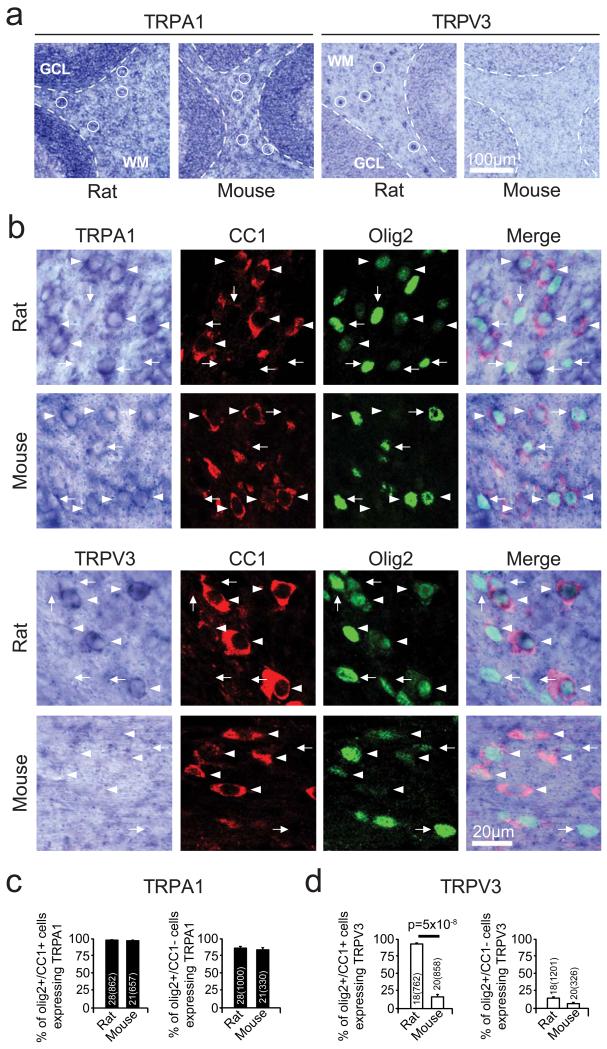

Using in situ hybridization, a TRPA1 probe labelled cerebellar white matter in rat and mouse, while a TRPV3 probe labelled rat only (Ext. Data Fig. 5a). Immunocytochemistry revealed that TRPA1- and TRPV3-expressing cells included myelinating oligodendrocytes expressing Olig2 and CC1 (Ext. Data Fig. 5b-d).

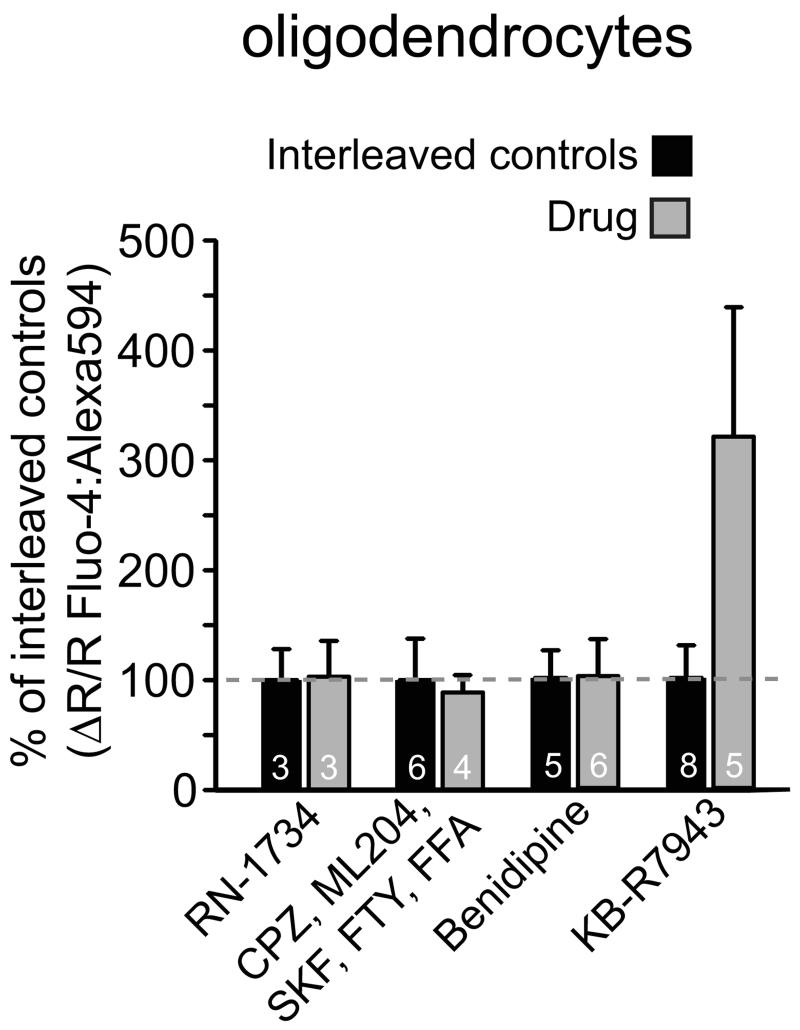

Consistent with ischaemia raising [Ca2+]i by activating TRPA1- rather than TRPV3-containing channels, the general TRP blockers20,27 ruthenium red (RuR, 10 μM) and La3+ (1 mM) and the TRPA1/TRPV3 blocker25 IPP (200 μM) reduced the [Ca2+]i rise, as did HC-030031 and A967079, which block TRPA1 but not TRPV326,28 (Fig. 4c-e). Knock-out of TRPA1 slowed and halved the ischaemia-evoked [Ca2+]i rise, and the TRPA1/TRPV3 blocker IPP produced no further reduction in the knock-out (suggesting no contribution of TRPV3: Fig. 4f), while knock-out of TRPV3 did not affect the [Ca2+]i rise, and the TRPA1 blocker HC-030031 slowed and halved the rise occurring in the TRPV3 knock-out (Fig 4g). Blockers of many other TRP channels had no effect (Ext. Data Fig. 6). Thus TRPA1 is the dominant contributor to the ischaemia-evoked rise of [Ca2+]i in oligodendrocytes.

The larger (70%) block of the ischaemia-evoked [Ca2+]i rise by the TRPA1 blocker HC-030031 than by TRPA1 knock-out (50%: Figs. 4e-f) suggests there may be compensatory upregulation of another Ca2+ entry pathway in the TRPA1 knock-out, which normally generates only ~30% of the [Ca2+]i rise. Introducing high pH-buffering-power solution into the cell blocked the [Ca2+]i rise in the TRPA1 knock-out (Fig. 4h), implying that the non-TRPA1 Ca2+ entry pathway is also H+-activated. Since the non-specific TRP blockers RuR and La3+ abolished the ischaemia-evoked [Ca2+]i rise, these data suggest there is another Ca2+-permeable TRP channel (neither TRPA1 nor TRPV3) which is activated by internal H+ in oligodendrocytes and generates ~30% of the ischaemia-evoked [Ca2+]i rise.

To assess the role of TRPA1-containing channels in evoking myelin damage, we exposed rat optic nerves to 60 mins ischaemia. This led to disruption of myelin sheaths2,3, which we quantified by counting the regions of myelin decompaction (lamellar separation) per axon cross section (see Methods). Taking as baseline the level of decompaction which occurs in control nerves during processing for EM, ischaemia increased decompaction (p=3×10−8), and ruthenium red or the TRPA1 blockers HC-030031 and A967079 (applied together) reduced this increase by 69% (p=3×10−5) and 59% (p=2.0×10−5) respectively (Fig. 4i-j). Ischaemia did not affect the axon g ratio (Fig. 4k: see Methods), but increased axon diameter via swelling (Fig. 4l). It also caused some axon vacuolization (Fig. 4m): vacuoles were seen in 4.3% of 2390 control axons, but in 21% of 15976 axons after ischaemia. Vacuolization was not prevented by TRP channel block (Fig. 4m), suggesting different mechanisms for axon and myelin damage.

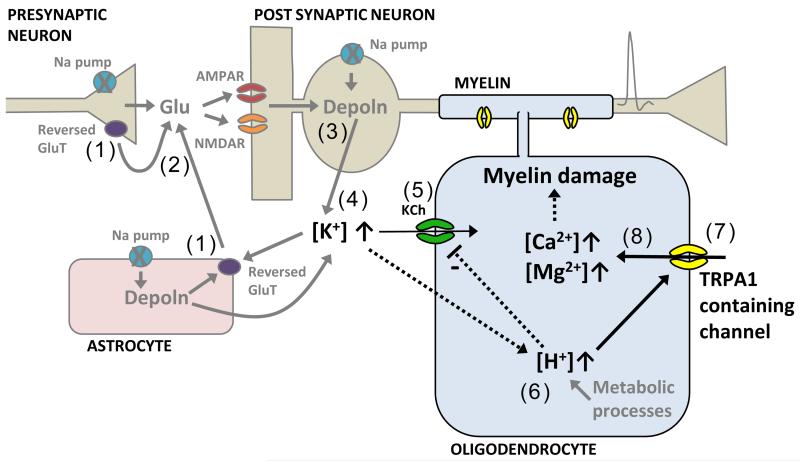

Thus, ischaemic damage to oligodendrocytes differs fundamentally from that in neurons (Ext. Data Fig. 7), where [Ca2+]i is raised by glutamate-gated receptors (and later by TRP channels activated by reactive oxygen species21). Contradicting current ideas2-4, ischaemia does not damage oligodendrocytes by activating Ca2+ entry through ionotropic glutamate receptors in their membranes. Instead, ischaemia-evoked sodium pump inhibition and glutamate release evoke a long-lasting rise of [K+]o that, together with metabolic changes, acidifies the oligodendrocyte, activating H+-gated TRP channels through which Ca2+ enters.

In the optic nerve, ischaemia-evoked Ca2+ entry into oligodendrocytes is blocked by NMDA receptor antagonists2, contradicting our demonstrations that NMDA evokes no [Ca2+]i rise in oligodendrocytes (Fig. 2) and that the ischaemia-evoked [Ca2+]i rise is unaffected by NMDA receptor blockers (Fig. 3). Conceivably, in the optic nerve, NMDA receptors on astrocytes29 make a greater contribution than in cerebellum to generating the ischaemia-evoked rise of [K+]o and thus the [Ca2+]i rise.

TRPA1 generates ~70% of the ischaemia-evoked [Ca2+]i rise, and TRPA1 blockers reduce ischaemic damage to myelin (Fig. 4). Consequently, blocking oligodendrocyte TRPA1-containing channels may reduce myelin loss during the energy deprivation that follows stroke, secondary ischaemia caused by spinal cord injury, or hypoxia in multiple sclerosis30.

Methods

Animals

Experiments used Sprague-Dawley rats or transgenic mice of either sex. Animal procedures were carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 and subsequent amendments. TRPV3 knock-out (KO) mice were obtained from JAX (http://jaxmice.jax.org/strain/010773.html). TRPA1 KO mice were obtained as a double knock-out with TRPV1 knocked out (kindly provided by John Wood and Jane Sexton). TRPV1 does not contribute to the ischaemia-evoked [Ca2+]i rise described here because the TRPV1 antagonist20,27 capsazepine did not reduce the ischaemia-evoked [Ca2+]i rise in rat oligodendrocytes (Ext. Data Fig. 6a) and the TRPV1 agonists20,27 capsaicin (10 μM) and camphor (2 mM) did not evoke a [Ca2+]i rise (see Specificity of drugs acting on TRP channels and Fig. 4a). Wild type and (double) KO mice were obtained from a colony obtained by breeding mice doubly heterozygous for the TRPA1 and TRPV1 knock-outs. The wild-type and KO mice compared share the same doubly heterozygous grandparents.

Brain slice preparation

Cerebellar slices (225 μm thick) were prepared from the cerebellum of P12 rats in ice-cold solution containing (mM) 124 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 1 NaH2PO4, 2.5 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 2-2.5 CaCl2, 10 glucose, bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2, pH 7.4, as well as 1 mM Na-kynurenate to block glutamate receptors. Slices were then incubated at room temperature (21–24°C) in the same solution until used in experiments. Cerebellar slices from P10-17 mice were prepared in ice-cold solution containing (mM) 87 NaCl, 25 NaHC03, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2.5 KCl, 7 MgCl2, 0.5 CaCl2, 25 glucose, 75 sucrose, 1 Na-kynurenate and then transferred to the same solution at 27°C and allowed to cool naturally to room temperature. Only 1 cell was recorded from in each slice.

Cell identification and electrophysiology

Oligodendrocytes, cerebellar granule cells and hippocampal pyramidal cells were identified by their location and morphology. All cells were whole-cell clamped with pipettes with a series resistance of 8-30 MΩ. Electrode junction potentials were compensated. I-V relations were from responses to 200 msec voltage steps. Unless otherwise indicated, cells were voltage-clamped at −74 mV.

External solutions

Slices were superfused with either bicarbonate-buffered solution containing (mM) 124 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 26 NaHCO3, 1 NaH2PO4, 2-2.5 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, pH 7.4, bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2, or with HEPES-buffered solution containing (mM) 144 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 10 HEPES, 1 NaH2PO4, 2-2.5 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, pH set to 7.3 with NaOH, bubbled with 100% O2. During experiments when NMDA was applied and ion concentration changes were observed with ion sensitive dyes, MgCl2 was omitted from the solution to minimize the Mg2+ block. For experiments involving Gd3+ and La3+, the HEPES-based solution was used and NaH2PO4 was omitted. To simulate ischaemia we replaced external O2 with N2, and external glucose with 7 mM sucrose, added 2 mM iodoacetate to block glycolysis, and 25 μM antimycin to block oxidative phosphorylation31,4. All ischaemia experiments were done at 33-36°C, while applications of NMDA and of TRP channel agonists were at 24°C. Control and drug conditions were interleaved where appropriate. For calcium imaging experiments when applying ischaemia solution to brain slices from transgenic mice, the experimenter was blind to the genotype.

Intracellular solutions

Cells were whole-cell clamped with electrodes containing either Cs- (to improve voltage uniformity) or K-gluconate-based solution, comprising (mM) 130 Cs-gluconate (or K-gluconate), 2 NaCl, 0.5 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 BAPTA, 2 NaATP, 0.5 Na2GTP, 2 MgCl, 0.5 K-Lucifer yellow, pH set to 7.2 with Cs- or K-OH (all from Sigma). The K+-based solution was used for current-clamp experiments. For Ca2+ imaging experiments, BAPTA was decreased to 0.01 mM and replaced with 10 mM phosphocreatine, added CaCl2 was reduced to 10 μM, and Lucifer Yellow was replaced with 1 mM Fura-2, or 200 μM Fluo-4 with 50 μM Alexa Fluor 594, or 200 μM X-Rhod-1 with 50 μM Alexa Fluor 488 (all from Molecular Probes) to allow ratiometric imaging. For imaging pH, Lucifer yellow was replaced with BCECF (96 μM) and the HEPES concentration was decreased to 0.5 mM. This [HEPES] was also used for control experiments when examining the effect of 50 mM internal [HEPES] on the ischaemia-evoked current; ischaemia-evoked membrane current changes were indistinguishable when 0.5 and 10 mM HEPES were used (see main text), presumably because endogenous pH buffering dominates at these low [HEPES] levels. For experiments where the pH-buffering capacity of the internal solution was increased, 68 mM K-gluconate and 50 mM HEPES were used. When uncaging protons, 2 mM 1-(2-nitrophenyl)ethyl sulphate sodium salt (NPE-caged protons, Tocris) was added to the pipette solution and 10 mM HEPES was replaced by 30 mM Tris to prevent UV light-mediated oxidation32 of HEPES (and K-gluconate was reduced from 130 to 120 mM). For Na+ and K+ imaging experiments, Lucifer yellow was replaced with 1 mM of the Na+-sensing dye SBFI tetra-ammonium salt or of the K+-sensing dye PBFI tetra-ammonium salt (Molecular Probes). In some experiments MK-801 (1 mM) was added to the internal solution to block NMDA receptors, and cells were depolarised to −10 mV for 10 sec intermittently over a 20 min waiting period to facilitate MK-801 block of open channels.

Single cell ion imaging and H+ uncaging

For Fura-2, SBFI and PBFI imaging when applying NMDA or during ischaemia, white matter oligodendrocytes and grey matter granule cells were patch-clamped with pipettes containing a solution as described above, fluorescence was excited sequentially at 340±10 nm and 380±10 nm, and emitted light was collected at 510±20 nm. The ratio (R) of the emission intensities (340 nm/380 nm), after subtraction of the background intensity averaged over 4 distant areas of the image, was used as a measure of intracellular ion concentration. Increases of ion concentration generated a fall of fluorescence (F) excited at 380 nm and a rise in fluorescence excited at 340 nm, which is plotted as ΔR/R in the graphs shown, with R= F340nm/F380nm: an upward deflection corresponds to a rise of concentration of the sensed ion. For Fura-2, SBFI and PBFI, mean values of R before applying NMDA or ischaemia solution were 0.41±0.05 (n=5), 1.68±0.14 (n=13) and 1.86±1.10 (n=8) respectively.

Fluo-4 and Alexa Fluor 594 were used in the internal solution to measure [Ca2+]i changes ratiometrically during H+-uncaging and most ischaemia experiments. To measure [Mg2+]i Mag-Fluo-4 was used instead of Fluo-4. Fluo-4 (or Mag-Fluo-4) and Alexa Fluor 594 fluorescence were excited sequentially every 2, 10 or 30 seconds at 488±10nm and 585±10nm, and emission was collected using a triband filter cube (DAPI /FITC/Texas Red, 69002, Chroma). The mean ratio of intensities (F488nm/F585nm) before applying NMDA or ischaemia was 0.81±0.09 (n=16) for Fluo-4 and 0.55±0.04 (n=6) for Mag-Fluo-4. Caged-H+ were uncaged using 380±20 nm light for 1 second every 2 seconds (repeated 30 times) interspersed with the above excitation wavelengths. BCECF was imaged every 30 seconds at 400 and 480nm, with emission collected using the above tri-band filter. The ratio (R) of the emitted light excited by these two wavelengths (F480nm/F400nm) was used as a measure of [H+]i (mean value before ischaemia was 17.6±0.9, n=8) but, since this ratio decreases with increasing [H+]i, when plotting changes in dR/R in Fig. 3e and Ext. Data Fig. 4 we multiplied them by −1 to produce a trace that increased with [H+]i.

During ischaemia, slices swelled at the time of the anoxic depolarisation. When cells were patch-clamped with calcium dyes, the resulting movement of the cell away from the electrode sometimes caused [Ca2+]i oscillations within the cells. These oscillations did not occur if the patch pipette was removed (after 2 minutes to allow dye-filling) before the ischaemic solution was applied. Without the pipette attached to the cell, the time-course of the ischaemia-evoked [Ca2+]i rise was the same as with the electrode attached, but its amplitude was 69% larger (ratio increase 0.21±0.03, n=20 versus 0.12±0.02, n=16). In some experiments (those in Fig. 4c-g and Ext. Data Fig. 6) we therefore removed the pipette for calcium-imaging.

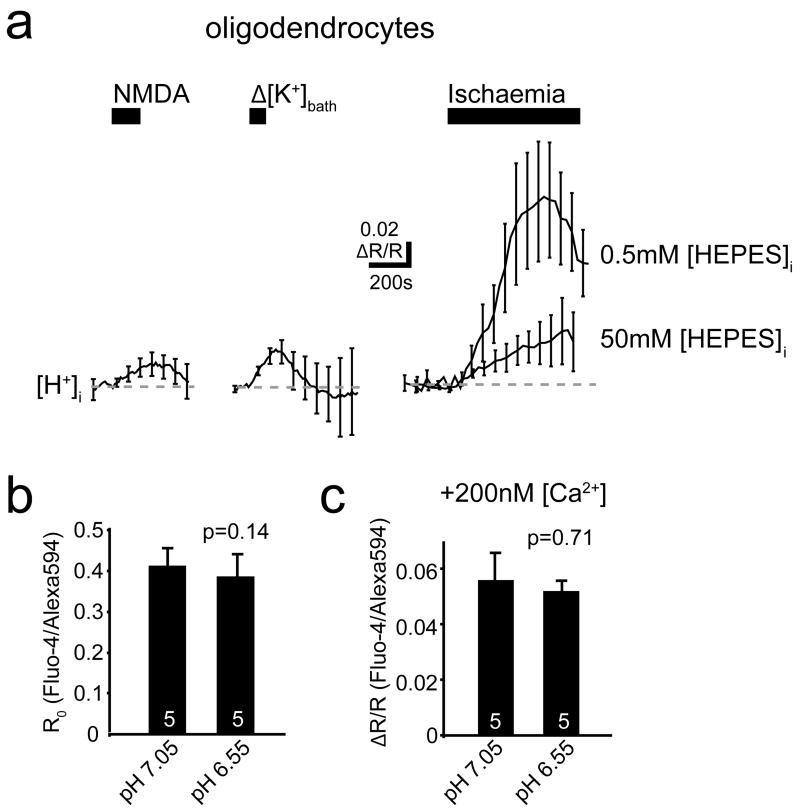

Control experiments were carried out to check whether the ischaemia-evoked change of pH would affect our [Ca2+]i measurements. The internal solution for Ca2+-sensing was studied in the experimental bath that the slices usually are placed in. The resting ratio of Fluo-4 fluorescence to Alexa 594 fluorescence was not significantly affected by altering the pH of the solution from 7.05 to 6.55, and this also did not affect the change of ratio produced by adding 200 nM Ca2+ to the sensing solution (Ext. Data Fig. 4b, c). Thus, even a 0.5 unit pH change occurring in the oligodendrocyte would not significantly affect the calcium dye measurements.

AM dye loading

X-Rhod-1-AM (38 μM) dye loading with the myelin marker DIOC6 into P12 cerebellar slices was performed as described previously for optic nerves2. Loading times ranged from 1-2 hrs and a de-esterification period of 30 mins at 36°C was allowed before imaging.

Potassium electrodes

Potassium electrodes were made as described33. Electrodes were pulled with a resistance of 4-10 MΩ. Electrode tips were silanised by heating them to 250°C for 7 minutes whilst N2 and N,N-dimethyltrimethylsilylamine (Fluka) were gassed into the tip from the back of the electrode. The tip was then filled with either 6% valinomycin, 1.5% potassium tetrakis(4-chlorophenyl)borate (Fluka) and 92.5% 1,2-dimethyl-3-nitrobenzene (Fluka) or the pre-made potassium sensitive ionophore I – cocktail B (Fluka). The electrodes were back-filled with the bicarbonate-buffered external solution mentioned above (2.5 mM K+), and attached to a sensitive high resistance electrometer (Model FD 223, World Precision Instruments). A reference electrode tip was placed less than 5 μm away from the K+ electrode tip, and the voltage changes measured by it were subtracted from those measured with the K+ electrode. [K+]o was determined by calibrating each electrode at the end of every experiment with at least 3 different K+ concentrations (1, 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10 or 17.5 mM). To check for cross-reactivity, the [NaCl]o was decreased by 60 mM which led to a −2.2±0.1 mV change in voltage (n=3), while a pH change from 7.3 to 6.5 led to a 0.47±0.22 mV change (n=3). Both of these changes are much less than the 17.5±0.5 mV change (n=18) seen in response to an increase of [K+]o from 2.5 to 5 mM (which is consistent with the electrodes used having an average calibration slope of 60.9±0.9 mV (n=6) per 10-fold change of [K+]o).

Drugs used

Stock solutions of the following drugs were made up in water: NMDA, AP5, NBQX, MK801, 7-CK, TTX, PDC, IPP, CPG, SKF 96365 and RuR. (S)-MCPG and amiloride were made up in external solution. Carvacrol was made up in ethanol. Bicuculline, bumetanide, HC 030031, A967079, flufenamic acid, capsazepine, FTY720-HCl, 2-APB, AITC, RN1734 and ML204 were made up in DMSO. When used, DMSO and ethanol were also added to control solution at the same concentrations, and did not evoke [Ca2+]i changes at the concentrations used. Stocks were kept at −20°C apart from carvacrol, menthol, vanillin, AITC, and RuR, which were made up fresh on each day of use. To minimise evaporation of carvacrol, vanillin and menthol, lids were kept on until the solutions were used. Gd3+ and La3+ were applied (as chloride salts) in bicarbonate- and phosphate-free solution to avoid chelation by these anions (see External Solutions above).

Immunohistochemical labelling of oligodendrocytes

Cerebellar slices were fixed for 30 mins in 4% PFA, and incubated for 1 to 6 h in 0.1% Triton X-100, 10% goat serum in phosphate-buffered saline at 21°C, then with primary antibody at 4°C overnight with agitation, and then 2 hours or overnight at 24°C with secondary antibody. Primary antibodies were: anti-CC1 (mouse, 1:300, Calbiochem OP80 monoclonal) and anti-Olig-2 (rabbit, 1:700, Millipore, AB9610 polyclonal). Secondary antibodies were: goat anti-rabbit AlexFluor 488 or 568 (Molecular Probes, 1:1000), donkey anti-rabbit AlexFluor 488 (Millipore, 1:1000), and goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 568 (Millipore, 1:1000).

Antibody labelling and in situ hybridization for TRPA1 and TRPV3

TRPA1 and TRPV3 antibodies appeared to label the myelinating processes and somata of oligodendrocytes in rat, but the labelling was not significantly different in wild-type mice and mice with TRPA1 or TRPV3 knocked-out (data not shown). We therefore turned to in situ hybridization.

Solutions used for in situ hybridization were pretreated with 0.1% DEPC. Animals were perfused with PBS followed by 4% PFA. Brains were post-fixed in 4% PFA overnight at 4°C, cryoprotected in 20% sucrose overnight at 4°C and frozen in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. Sections (20 μm) collected onto Superfrost Plus microscope slides (VWR International) were hybridized at 65°C overnight with hybridization buffer [50% v/v deionized formamide (Sigma), 10% w/v dextran sulphate (Fluka), 0.1 mg/ml yeast tRNA (Roche), 1x Denhardt’s solution (Sigma) and 1x “salts” (200 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM NaH2PO4, 5 mM Na2HPO4)] containing digoxigenin (DIG)-labelled antisense RNA probe (1:1000). Sections were washed with a washing solution (50% v/v formamide, 1× SSC, 0.1% Tween 20) three times at 65°C for 30 min, followed by two 1× MABT (100 mM maleic acid, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5, 0.1% Tween-20) washes at room temperature for 30 min each. Sections were subsequently blocked with blocking solution [2% w/v Blocking Reagent (Roche Diagnostics), 10% v/v heat-inactivated sheep serum (Sigma) in 1× MABT] for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with anti-DIG antibody conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (AP) (Roche Diagnostics, 1:1500 in blocking solution) at 4°C overnight. Sections were then washed in 1× MABT 5 times for 20 min each at room temperature, followed by two 5 min washes in staining buffer (100 mM NaCl, 50 mM MgCl2, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 9.5, 0.1% Tween-20). Development was performed at 37°C for 24-48 hours overnight with nitroblue tetrazolium/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate in freshly prepared staining solution (50% v/v staining buffer, 25 mM MgCl2, 5% w/v polyvinyl alcohol). Sections were washed in PBS and immunohistochemistry was performed as described above. The plasmids used to generate RNA probes were: IMAGE clone 40129486 for Trpa1 (linearized with ClaI and transcribed with T3 RNA polymerase) and IMAGE clone 40047664 for Trpv3 (linearized with XhoI and transcribed with SP6 RNA polymerase). In situ hybridization was repeated using at least three animals for each probe.

Quantifying myelin decompaction during chemical ischaemia using electron microscopy

For chemical ischaemia experiments, optic nerves were dissected from P28 Sprague-Dawley rats and incubated for 1 hour at 36°C in either control or ischaemic solution with and without the TRPA1/V3 channel blocker ruthenium red (10 μM) or the combined presence of the TRPA1 blockers HC-030031 (80 μM) and A967079 (10 μM). The optic nerves were then immersion fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer overnight. All samples were then post-fixed in 1% OsO4/0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.3) at 3°C for 2 hours before washing in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.3). The samples were dehydrated in a graded ethanol-water series at 3°C and infiltrated with Agar 100 resin mix. The nerve was then cut transversely at the mid-point, blocked out and hardened. Ultra-thin sections were taken, 300 microns from the cut end of the middle of the nerve, on a Reichert Ultracut S microtome. Sections were collected on 300 mesh copper grids and stained with lead citrate. The sections were imaged using a Joel 1010 transition electron microscope and a Gatan Orius camera.

In 3 out of 4 experiments the experimenter was blinded to the drug condition prior to imaging (all 4 experiments gave similar results). One section was used from each nerve and eight 21.5 μm × 17.3 μm images were collected at x8000 magnification, four from the peripheral borders of the nerve at 0°, 90°, 180° and 270° positions on the section, and four covering the central portion of the nerve. In all experiments the image identities were then blinded prior to analysis, and the number of large separations of lamellae (decompaction) was counted. Decompaction was defined as a visible white inter-lamellar gap being present between at least 2 normal lamellae. Regions of decompaction were normally separated from each other by an area of compact myelin, but when most of the myelin surrounding an axon had separated lamellae, decompacted regions were counted at 0.5 micron intervals around the sheath. The number of decompacted regions was normalised to the number of axons per image. Some decompaction occurred even in control nerves as a result of the processing for electron microscopy, so we assessed drug block of decompaction by quantifying the ischaemia-evoked increase in decompactions seen without and with the drug present. Myelin g ratios were calculated as the square root of the ratio of the area of the axon to the area of the axon plus myelin sheath. When drawing lines around the axon and sheath, areas of decompaction were ignored, i.e. we interpolated the lines from regions that were not decompacted. Axon diameter was calculated as (4.(axon area)/π)0.5. Axon vacuolisation was defined as the inclusion of one or more large (>0.1 μm) empty membrane bound (often circular) organelles within the axon or periaxonal space (Fig. 4m) which may reflect rearrangement of internal axonal membranes or be formed from inclusion of myelin membranes into the axon (Fig. 4m).

Statistics

Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. Experiments were carried out on brain slices from at least 3 animals on at least 3 separate days, except for a few experiments using expensive drugs which were done on only 2 days. Only 1 cell was recorded from in each slice, so the numbers of cells given are also the numbers of slices. P values are from two tailed Student’s t-tests (for normally distributed data, assessed using Shapiro-Wilk tests) or Mann-Whitney U tests (for non-normally distributed data). Normally distributed data were tested for equal variance (p<0.05, unpaired F-test) and homo- or heteroscedastic t-tests were chosen accordingly. P values in the text are from unpaired t-tests unless otherwise stated. When small sample sizes (n≤4) achieved p<0.05, analysis of sample and effect size typically demonstrated a power for detecting the observed effect of 80-99% (mean 92%), with two exceptions: the process data in Fig. 4c (power 78%) and the soma data in Fig. 4h (power 75%). For multiple comparisons within one experiment (usually one figure panel, but measurements of [Ca2+]i in somata and processes were treated as separate experiments even when plotted in the same figure panel), P values were corrected using a procedure equivalent to the Holm-Bonferroni method (for N comparisons, the most significant p value is multiplied by N, the 2nd most significant by N-1, the 3rd most significant by N-2, etc.; corrected p values are significant if they are less than 0.05). All statistical analysis was conducted using OriginLab software.

Extended Data

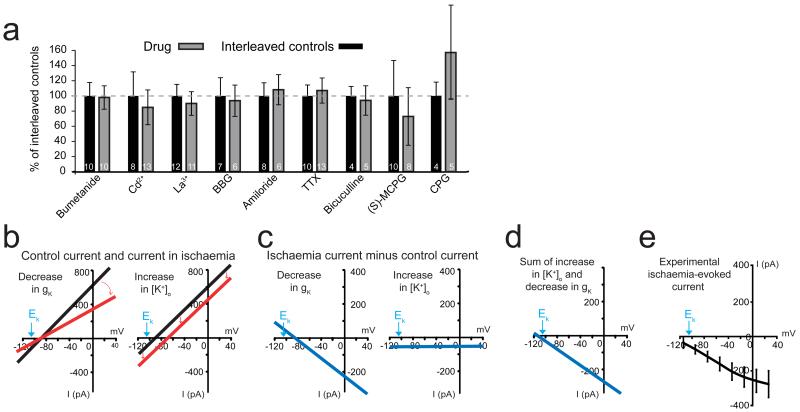

Ext. Data Fig. 1. Tests for causes of the ischaemia-evoked current.

a Effect of blocking various putative glutamate release mechanisms (blocker concentrations given in Supplementary Information) on peak ischaemia-evoked currents measured in the presence of each drug and in interleaved controls. No significant differences were measured (p>0.20). b Schematic showing effect of ischaemia-evoked decrease in resting conductance (which is dominated by gK, left) and ischaemia-evoked [K+]o rise (right) on oligodendrocyte membrane current. Black lines are control I-V relations. Red lines are I-V relations in ischaemia showing the effect of a conductance decrease (left) or of a positive shift of reversal potential due to [K+]o rising (right). c Ischaemia-evoked current change for the two mechanisms in b (cf. Fig. 1g). d Sum of currents in c gives an I-V relation with a reversal potential more negative than EK. e Experimentally observed ischaemia-evoked current in 10 oligodendrocytes with 10 mM internal HEPES (difference of curves in Fig. 1f). Error bars are s.e.m.

Ext. Data Fig. 2. K+ flux changes generate the oligodendrocyte NMDA-evoked current.

a-b Extracellular Cs+ (30 mM, replacing Na+) reduces the inward current evoked by 100 μM NMDA at −74 mV in oligodendrocytes (a), but not in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons (b). c-d Intracellular MK-801 (1 mM) has no effect on NMDA-evoked currents in oligodendrocytes (c) but blocks them in pyramidal cells (d), while extracellular MK-801 (50 μM) blocks both. e Voltage-dependence of the current evoked in 16 oligodendrocytes by 100 μM NMDA and by elevating [K+]o from 2.5 to 5 mM. f Specimen plot of membrane current in an oligodendrocyte versus local [K+]o in response to applying 100 μM NMDA or elevating [K+]o from 2.5 to 5 mM. Horizontal cell line shows that if NMDA raises [K+]o to (say) 4.5 mM, the current attributable to the [K+]o rise alone is 51% of the NMDA-evoked current. Mean value in 11 cells was 49% (see Supplementary Information). Error bars are s.e.m.

Ext. Data Fig. 3. NMDA-evoked ion concentration changes in neurons differ from those in oligodendrocytes.

a Specimen records of cerebellar granule cell membrane current and background-subtracted fluorescent dye ratio (R, see Methods) when measuring [Ca2+]i with Fura-2, [Na+]i with SBFI, and [K+]i with PBFI, when 100μM NMDA was applied. The rise of [K+]i seen reflects K+ entry: [K+]pipette was 32.5 mM, so EK>−60mV for [K+]o >3.3 mM. b Mean peak fluorescence change normalised to evoked current (number of cells on bars; p value from Mann-Whitney test). Oligodendrocyte data for comparison are shown in Fig. 2. Error bars are s.e.m.

Ext. Data Fig. 4. Comparison of NMDA-, [K+]bath- and ischaemia-evoked changes of [H+]i.

a Measurements of changes of ratio (R, see Methods) of background-subtracted BCECF fluorescence in oligodendrocytes in response to 100 μM NMDA and raising [K+]bath from 2.5 to 5 mM with 0.5 mM internal HEPES, and to ischaemia with 0.5 mM and 50 mM internal HEPES. b-c Effect of pH of 10 mM HEPES internal solution on: (b) baseline ratio of Fluo-4 to Alexa 594 fluorescence (p value from Mann-Whitney test), and (c) change of ratio when [Ca] was increased by 200 nM. Error bars are s.e.m.

Ext. Data Fig. 5. In situ hybridization data on TRP channel expression.

a. In situ data for TRPA1 and TRPV3 in the cerebellum of rats and mice show TRPA1 mRNA in white matter (WM) cells in rats and mice (with denser expression in the adjacent granule cell layer, GCL), but TRPV3 mRNA only in white matter cells in rats. Specimen cells are labelled with white circles. b Higher magnification views of white matter, combining in situ hybridization for TRPA1 and TRPV3 with immunocytochemistry for Olig2 (to label oligodendrocyte lineage cells) and CC1 (to define myelinating oligodendrocytes). TRPA1 mRNA is present (in rats and mice) and TRPV3 mRNA is present (in rats but not mice) in myelinating oligodendrocytes (Olig2+, CC1+: arrowheads) and also in some presumed oligodendrocyte precursor cells (Olig2+, CC1−: arrows). c-d Quantification of presence of mRNA for TRPA1 (c) and TRPV3 (d) in different oligodendrocyte lineage cell classes. Numbers on bars are ‘images analysed (cells counted)’. P value from Mann-Whitney test. Error bars are s.e.m.

Ext. Data Fig. 6. Further evidence for the identity of TRP channels in oligodendrocytes.

[Ca2+]i increase (ratio signal from Fluo-4 and Alexa Fluor 594) in oligodendrocyte somata when ischaemia solution was applied with the following drugs present (data normalised to interleaved controls, shown as black bars): RN-1734 (0.5 mM), which blocks TRPV4 and, less well, TRPV1, TRPV3 and TRPM8; a cocktail of blockers inhibiting (see Supplementary Information section on Specificity of drugs acting on TRP channels) TRPP2, TRPC3, TRPC4, TRPC5, TRPC6, TRPC7, TRPM2, TRPM4, TRPM5, TRPV1, TRPV2, TRPM7, TRPM8 and TRPP1, as well as the store-operated calcium channel component STIM1 and some voltage-gated calcium channels; blocking voltage-gated Ca2+ channels with 10μM benidipine; or blocking reversed Na/Ca exchange with 10μM KB-R7943 mesylate (p values, from Mann-Whitney test and t-test as appropriate, were non-significant (p>0.28)). Error bars are s.e.m.

Ext. Data Fig. 7. Schematic of how oligodendrocyte [Ca2+]i is raised in ischaemia.

Run-down of transmembrane ion gradients leads to glutamate transporters (GluT) reversing (1) and releasing glutamate (2). This depolarizes (and causes a neurotoxic [Ca2+]i rise in) neurons (3) and raises [K+]o (4), causing an inward current (5) through oligodendrocyte K+ channels (KCh). At the same time, metabolic changes and also the rise of [K+]o lead to a rise in oligodendrocyte [H+]i (6). This decreases the membrane K+ conductance (either directly or via TRPA1-containing channels opening) which contributes to the inward current generated, and opens TRPA1-containing channels (7) that let Ca2+ and Mg2+ into the cell (8). The resulting rise of [Ca2+]i damages the myelin.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Supported by a Wellcome Trust Programme Grant and Senior Investigator Award, and ERC Advanced Investigator Award, and the EU (Leukotreat). We thank Paikan Marcaggi for help with ion-sensitive electrodes, and Jane Sexton and John Wood for knock-out mice. Karolina Kolodziejczyk was in the 4 year PhD Programme in Neuroscience at UCL. We thank Lorena Arancibia-Carcamo, Marc Ford, Alasdair Gibb, Renaud Jolivet, Josef Kittler, Marija Sajic, Angus Silver and Ken Smith for comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

References

- 1.Stys PK, Ransom BR, Waxman SG, Davis PK. Role of extracellular calcium in anoxic injury of central white matter. Proc. Natl. Acad, Sci. USA. 1990;87:4212–4216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.11.4212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Micu I, et al. NMDA receptors mediate calcium accumulation in myelin during chemical ischaemia. Nature. 2006;439:988–992. doi: 10.1038/nature04474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salter MG, Fern R. NMDA receptors are expressed in developing oligodendrocyte processes and mediate injury. Nature. 2005;438:1167–1171. doi: 10.1038/nature04301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Káradóttir R, Cavelier P, Bergersen LH, Attwell D. NMDA receptors are expressed in oligodendrocytes and activated in ischaemia. Nature. 2005;438:1162–1168. doi: 10.1038/nature04302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakiri Y, Hamilton NB, Karadottir R, Attwell D. Testing NMDA receptor block as a therapeutic strategy for reducing ischaemic damage to CNS white matter. Glia. 2008;56:233–240. doi: 10.1002/glia.20608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarran WJ, Goldberg MP. White matter axon vulnerability to AMPA/kainate receptor-mediated ischemic injury is developmentally regulated. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:4220–4229. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5542-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agrawal SK, Fehlings MG. Role of NMDA and non-NMDA ionotropic glutamate receptors in traumatic spinal cord axonal injury. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:1055–1063. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-03-01055.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarrafzadeh AS, Kiening KL, Callsen TA, Unterberg AW. Metabolic changes during impending and manifest cerebral hypoxia in traumatic brain injury. Brit. J. Neurosurg. 2003;17:340–346. doi: 10.1080/02688690310001601234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li S, Mealing GA, Morley P, Stys PK. Novel injury mechanism in anoxia and trauma of spinal cord white matter: glutamate release via reverse Na+-dependent glutamate transport. J Neurosci. 1999;19:RC16. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-j0002.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Back SA, et al. Hypoxia-ischemia preferentially triggers glutamate depletion from oligodendroglia and axons in perinatal cerebral white matter. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:334–347. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuan X, Eisen AM, McBain CJ, Gallo V. A role for glutamate and its receptors in the regulation of oligodendrocyte development in cerebellar tissue slices. Development. 1998;125:2901–2914. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.15.2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lundgaard I, et al. Neuregulin and BDNF induce a switch to NMDA receptor-dependent myelination by oligodendrocytes. PLoS Biol. 2013;11:e1001743. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cahoy JD, et al. A transcriptome database for astrocytes, neurons, and oligodendrocytes: a new resource for understanding brain development and function. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:264–278. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4178-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Biase LM, Nishiyama A, Bergles DE. Excitability and synaptic communication within the oligodendrocyte lineage. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:3600–3611. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6000-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kukley M, Nishiyama A, Dietrich D. The fate of synaptic input to NG2 glial cells: neurons specifically downregulate transmitter release onto differentiating oligodendroglial cells. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:8320–8331. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0854-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossi DJ, Oshima T, Attwell D. Glutamate release in severe brain ischaemia is mainly by reversed uptake. Nature. 2000;403:316–321. doi: 10.1038/35002090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Limbrick DD, Jr., Sombati S, DeLorenzo RJ. Calcium influx constitutes the ionic basis for the maintenance of glutamate-induced extended neuronal depolarization associated with hippocampal neuronal death. Cell Calcium. 2003;33:69–81. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(02)00054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamann M, Rossi DJ, Mohr C, Andrade AL, Attwell D. The electrical response of cerebellar Purkinje neurons to simulated ischaemia. Brain. 2005;128:2408–2420. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lesage F, et al. TWIK-1, a ubiquitous human weakly inward rectifying K+ channel with a novel structure. EMBO J. 1996;15:1004–1011. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nilius B, Szallasi A. Transient receptor potential channels as drug targets: from the science of basic research to the art of medicine. Pharmacol. Rev. 2014;66:676–814. doi: 10.1124/pr.113.008268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aarts M, et al. A key role for TRPM7 channels in anoxic neuronal death. Cell. 2003;115:863–877. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butenko O, et al. The increased activity of TRPV4 channel in the astrocytes of the adult rat hippocampus after cerebral hypoxia/ischemia. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39959. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang YY, Chang RB, Liman ER. TRPA1 is a component of the nociceptive response to CO2. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:12958–12963. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2715-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cao X, Yang F, Zheng J, Wang K. Intracellular proton-mediated activation of TRPV3 channels accounts for the exfoliation effect of α-hydroxyl acids on keratinocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;31:25905–25916. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.364869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bang S, Yoo S, Yang TJ, Cho H, Hwang SW. Isopentenyl pyrophosphate is a novel antinociceptive substance that inhibits TRPV3 and TRPA1 ion channels. Pain. 2011;152:1156–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McNamara CR, et al. TRPA1 mediates formalin-induced pain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:13525–13530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705924104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clapham DE. SnapShot: Mammalian TRP channels. Cell. 2007;129:220.e1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen J, et al. Selective blockade of TRPA1 channel attenuates pathological pain without altering noxious cold sensation or body temperature regulation. Pain. 2011;152:1165–1172. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamilton NB, et al. Mechanisms of ATP- and glutamate-mediated calcium signaling in white matter astrocytes. Glia. 2008;56:734–749. doi: 10.1002/glia.20649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davies AL, et al. Neurological deficits caused by tissue hypoxia in neuroinflammatory disease. Ann. Neurol. 2013;74:815–825. doi: 10.1002/ana.24006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allen NJ, Káradóttir R, Attwell D. A preferential role for glycolysis in preventing the anoxic depolarization of rat hippocampal area CA1 pyramidal cells. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:848–859. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4157-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keynes RG, Griffiths C, Garthwaite J. Superoxide-dependent consumption of nitric oxide in biological media may confound in vitro experiments. Biochem. J. 2003;369:399–406. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marcaggi P, Jeanne M, Coles JA. Neuron-glial trafficking of NH4+ and K+ : separate routes of uptake into glial cells of bee retina. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004;19:966–976. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816x.2004.03165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.