Abstract

Attempts to create artificial liver tissue from various cells have been reported as an alternative method for liver transplantation and pharmaceutical testing. In the construction of artificial liver tissue, the selection of the cell source is the most important factor. However, if an appropriate environment (in vitro/in vivo) cannot be provided for various cells, it is not possible to obtain artificial liver tissue with the desired function. Therefore, we focused on the in vitro environment and produced liver tissues using MEMS technology. In the present study, we report a combinatorial TASCL device to prepare 3D cell constructs in vitro. The TASCL device was fabricated with an overall size of 10 mm × 10 mm with microwells and a top aperture (400 µm × 400 µm, 600 µm × 600 µm, 800 µm × 800 µm) and bottom aperture (40 µm × 40 µm, 80 µm × 80 µm, 160 µm × 160 µm) per microwell. The TASCL device can be easily installed on various culture dishes with tweezers. Using plastic dishes as the bottom surface of the combinatorial TASCL device, 3D hepatocyte constructs of uniform sizes (about ɸ 100 μm–ɸ 200 μm) were produced by increasing the seeding cell density of primary mouse hepatocytes. The 3D hepatocyte constructs obtained using the TASCL device were alive and secreted albumin. On the other hand, partially adhered primary mouse hepatocytes exhibited a cobblestone morphology on the collagen-coated bottom of the individual microwells using the combinatorial TASCL device. By changing the bottom substrate of the TASCL device, the culture environment of the cell constructs was easily changed to a 3D environment. The combinatorial TASCL device described in this report can be used quickly and simply. This device will be useful for preparing hepatocyte constructs for application in drug screening and cell medicine.

Key words: Primary hepatocytes, Hepatic constructs, Three-dimensional (3D) culture, Tapered stencil for cluster culture (TASCL) device, Biomedical microdevices

INTRODUCTION

Attempts to create artificial liver tissue from induced pluripotent stem cells (27–29), embryonic stem cells (1,3,30), other stem cells (12), and tissue cells (5,22) have been reported as alternative methods for use in liver transplantation (13) and pharmaceutical testing (4,14–17). In the construction of artificial liver tissue, the selection of the cell source (13,18–21,27,30) is the most important factor. However, an appropriate environment (in vitro/in vivo) for the cells cannot be provided; it is not possible to obtain artificial liver tissue with the desired functions, such as the capacity for albumin secretion, cytochrome P450 activity, ammonia metabolism, etc. Therefore, we focused on the in vitro environment and attempted to create liver tissues using the MEMS (Micro Electro Mechanical Systems) technique.

Various methods for manufacturing artificial liver tissue (14,17) (i.e., hepatic cell aggregates) have been devised using spinner flasks, gyratory culture apparatuses, culture devices modified with low cell adhesive cationic compounds (23), poly(2-hydroxyethylmethacrylate) (32), hollow fibers (26), scaffolds (7), or the hanging drop method, etc. Conventional cell aggregate formation has also been induced using the hanging drop method. This method, however, is not suitable for the mass production of cell aggregates because it requires the manual deposition of uniform small droplets containing cells onto the culture substrate. Recently, several culture methods have been developed for the mass production of cell aggregates using ultralow adhesive surfaces in which the cells are suspended in medium (9) or Matrigel, wherein the cells can migrate three dimensionally (2). However, there remain problems with these techniques, including that clusters of various sizes are formed during the experiments. Therefore, processes of separation are required following cell aggregate formation. The variation in cell aggregate size seemingly derives from the randomness of the initial condition of each cell aggregate formation number and population density of cells.

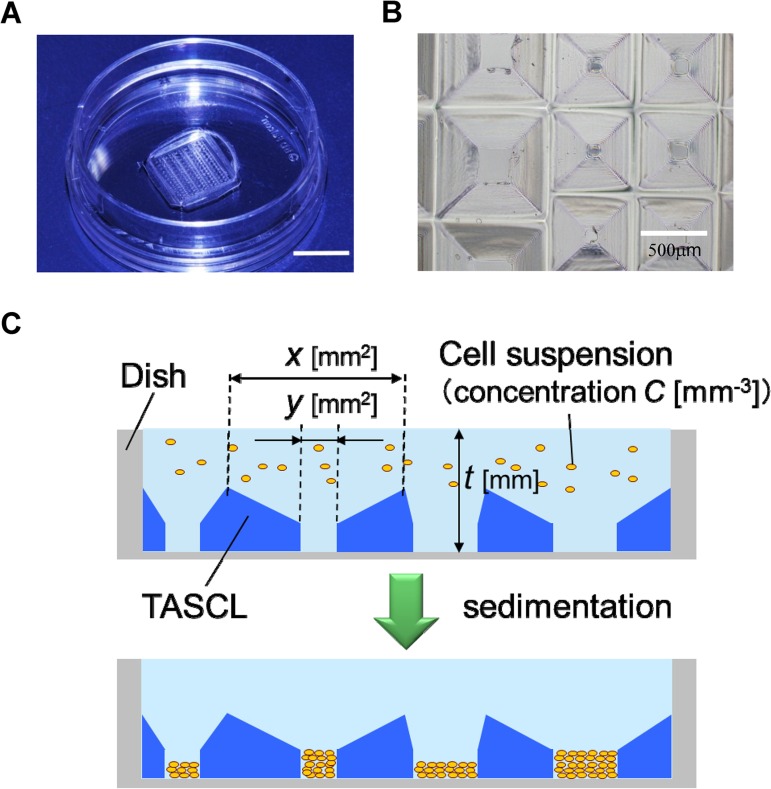

In order to address this problem, we proposed the use of the tapered stencil for cluster culture (TASCL) method (Fig. 1A, B), an array employing tapered microapertures of varying sizes made of poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) (10,11,33). The self-sealing ability of PDMS enables the easy attachment and removal of a combinatorial TASCL on various substrates without adhesives. Briefly, by placing TASCL on a cell culture dish, microwells are formed on the substrate (Fig. 1). The seeding condition in each microwell can be controlled based on the area of the top aperture x (mm2) and bottom aperture y (mm2). The cell population (P) in a microwell and cell density (D) at the bottom of the microwell are described as follows:

Figure 1.

Fabrication of combinatorial TASCL device. (A) The combinatorial TASCL device consisted of various microwells measuring 10 mm by 10 mm with a thickness of 0.55 mm. Scale bar: 10 mm. (B) The combinatorial TASCL device was observed under phase-contrast microscopy. Scale bar: 500 μm. (C) A schematic diagram of cell seeding and cell construct process using TASCL. Cell constructs can be created under multiple initial conditions simultaneously by injecting cell suspension onto the TASCL device.

| (1) |

| (2) |

where C (cells/ml) is the concentration of the cell suspension medium, and t (mm) is the depth of the medium. The walls between microwells are formed to have a knife edge so that all cells fall into one of the microwells, thus preventing the unexpected intrusion of cells following the initial sedimentation. Therefore, multiple 3D cell constructs can be initiated under defined conditions at the same time by simply placing a droplet of cell suspension onto the device. Unlike other previous reports using arrays of single-size microwells (24,31), a combinatorial TASCL device can be used to create 3D cell constructs under multiple controlled seeding conditions simultaneously.

In the present study, we report the application of a combinatorial TASCL device to prepare 3D cell constructs in vitro. Using the TASCL device, we evaluated 3D constructs using primary mouse hepatocytes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

William’s E Medium and antibiotics (penicillin, streptomycin, and kanamycin) were purchased from Life Technologies, Inc. (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from Gemini Bio-Products (West Sacramento, CA, USA). Insulin and dexamethasone were purchased from Sigma Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). All other materials and chemicals not specified above were of the highest grade available.

Fabrication of a Combinatorial TASCL Device

The dimensions of the top and bottom aperture of a combinatorial TASCL device are shown in Table 1. The TASCL device was created using PDMS (SYLGARD® 184; Dow Corning, Midland, MI, USA) according to the micromolding technique (10,11). First, a master mold was fabricated with photocurable resin (SCR770; D-MEC Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) using microstereolithography. In order to prevent adhesion of the PDMS and the master mold, the surface of the mold was dip coated with fluoropolymer (CYTOP; AGC, Tokyo, Japan) and baked at 200°C for 60 min. PDMS prepolymer (SYLGARD 184; Dow Corning Toray Co., Japan) was injected into the master mold, which was placed in a vacuum for 15 min to eliminate air bubbles trapped in the mold. After curing at 80°C for 12 h, the TASCL device was detached from the master mold and washed with Milli-Q water (Milli-Q Integral Water Purification System; Merck-Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) and ethanol and then placed on a 35-mm plastic culture dish (Falcon 3001; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and sterilized under UV for 12 h. The upper surface of the TASCL device was coated with an aqueous solution of polyethylene oxide-polypropylene oxide-polyethylene oxide triblock copolymer (1 wt% Anti-Link; Allvivo Vascular, Inc., Lake Forest, CA, USA) for 12 h at room temperature. The copolymer self-assembles on hydrophobic surfaces and forms a hydrophilic layer that prevents cell adhesion. The bottom surface of the TASCL device is maintained intact due to the self-sealing ability of PDMS, whereas the top surface is hydrophilic. The array of microwells was placed at the center of the TASCL device and surrounded by a trench to prevent the uncontrolled intrusion of cells from the boundary area.

Table 1.

Combinations of the Size of the Top and Bottom Apertures of the Combinatorial TASCL Device

| Size of the Top Aperture (μm) | Size of the Bottom Aperture (μm) | Number of Microwells |

|---|---|---|

| 400 × 400 | 40 × 40, 80 × 80, 160 × 160 | 12, 12, 12 |

| 600 × 600 | 40 × 40, 80 × 80, 160 × 160 | 8, 8, 8 |

| 800 × 800 | 40 × 40, 80 × 80, 160 × 160 | 6, 6, 6 |

Animals

Male Institute for Cancer Research (ICR) mice (n = 3) (7–8 weeks old, specific pathogen free) weighing approximately 25–30 g were purchased from Japan SLC, Inc. (Shizuoka, Japan). The mice studies were approved by the review committee of Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, Nagoya, Japan.

Isolation and Creation of 3D In Vitro Cell Constructs of Primary Mouse Hepatocytes Using a Combinatorial TASCL Device

Primary hepatocytes were isolated from ICR mouse livers (n = 3) using collagenase (S-I; Nitta Gelatin, Tokyo, Japan), as previously described (6,25). The viability of the employed cells was greater than 85%, as determined according to the trypan blue dye exclusion test. The final concentration of trypan blue (Gibco®, Life Technologies Inc.) was 0.2%.

ICR mice primary hepatocytes at densities of 5 × 104, 1 × 105, and 2 × 105 cells/dish were inoculated on a combinatorial TASCL device to form hepatic cell constructs. The cells were then cultured in 0.35 ml of William’s E Medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1 µmol/L of insulin, 1 µmol/L of dexamethasone, 100 µg/ml of kanamycin, 100 U/ml of penicillin, and 100 U/ml of streptomycin (culture medium). The cells were incubated at 37°C under a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere.

A 35-mm plastic culture dish (Falcon 3001) and 35-mm collagen-coated dish (BD Biocoat Collagen I Cellware, BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA, USA) were used as the bottom portion of the TASCL device. The medium on the dishes was partially changed every day. In the 2D monolayer culture (control) group, mouse primary hepatocytes were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 in culture medium on 35-mm collagen-coated dishes. The cells were cultured for 6 days, and the differential hepatic activity was determined as described below.

Hepatic Function Tests In Vitro

The primary hepatocytes were stained with calcein acetoxymethyl ester (calcein AM, 1 mg/ml solution in anhydrous dimethyl sulfoxide, C3099; Molecular Probes®, Life Technologies, Inc.) to detect viable cells. We combined the reagents by transferring 10 µl of the supplied 1 mmol/L calcein AM stock solution to the 5 ml Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline without Ca2+ and Mg2+ supplementation (DPBS free; Life Technologies, Inc.). The cells were incubated in this 2 µmol/L calcein AM/DPBS-free solution for 20 min at 37°C. Calcein AM-positive green cells were judged to be alive with a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

We carried out 2D monolayer culture to confirm if primary hepatocytes isolated from ICR mice livers secrete albumin. After confirmation, we cultured primary hepatocytes from the same isolation in the TASCL device. The level of albumin production was assessed by the accumulation of albumin in the culture medium after 24 h using a mouse albumin enzyme linked immunosorbent assay quantification kit, as instructed by the manufacturer (Bethyl Laboratories, Inc., Montgomery, TX, USA).

RESULTS

Preparation of a Combinatorial TASCL Device

A combinatorial TASCL device was created with an overall size (Fig. 1A) of 10 mm × 10 mm, containing microwells, which have a top aperture (400 µm × 400 µm, 600 µm × 600 µm, 800 µm × 800 µm) and bottom aperture (40 µm × 40 µm, 80 µm × 80 µm, 160 µm × 160 µm) per microwell (Fig. 1B, Table 1). The TASCL device can be easily installed on a commercially available culture dish and be used to freely replace the cell adhesion surface matrix. In this system, we used hydrophobic treatment of the surface inside the TASCL device and put 35-mm plastic (normal) and collagen-coated culture dishes under the TASCL device.

Creation of 3D In Vitro Constructs of Primary Mouse Hepatocytes Using a Combinatorial TASCL Device

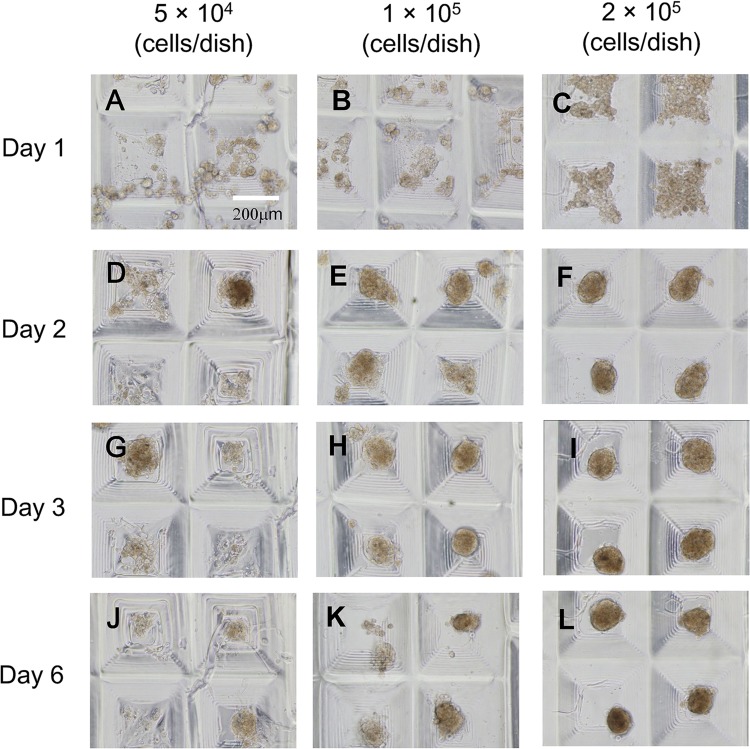

We characterized the 3D constructs of primary mouse hepatocytes using the combinatorial TASCL device (Fig. 2). A total of 5 × 104, 1 × 105, and 2 × 105 cells were seeded onto the TASCL device and were cultured for 6 days. A 35-mm plastic culture dish was used as the bottom part of the TASCL device. As cell seeding density increased, tendency toward the creation of hepatocyte constructs with a defined size was noted. After 2 days of culture, hepatocyte constructs were observed under phase-contrast microscopy (Fig. 2F). At cell densities of 1 × 105 and 2 × 105 cells/dish, hepatocytes in the constructs maintained their spherical morphology after 3 and 6 days of culture (Fig. 2H, I and K, L). However, at a low cell seeding density (5 × 104 cells/dish), seeded cells adhered to the bottom of the device and displayed morphology similar to that in the 2D monolayer culture (Fig. 2A, D, G, and J). The morphology of the hepatocyte constructs was significantly different between microwells.

Figure 2.

Phase-contrast photomicrographs of primary mouse hepatocyte constructs created using a combinatorial TASCL device and the bottom surface of the TASCL device employed as a 35-mm uncoated plastic culture dish. Primary mouse hepatocytes at a density of 5 × 104 (A, D, G, and J), 1 × 105 (B, E, H, and K), and 2 × 105 cells (C, F, I, and L) were inoculated on the combinatorial TASCL device for 6 days. The culture periods are as follows: 1 day (A, B, and C), 2 days (D, E, and F), 3 days (G, H, and I), and 6 days (J, K, and L). Scale bar: 200 µm.

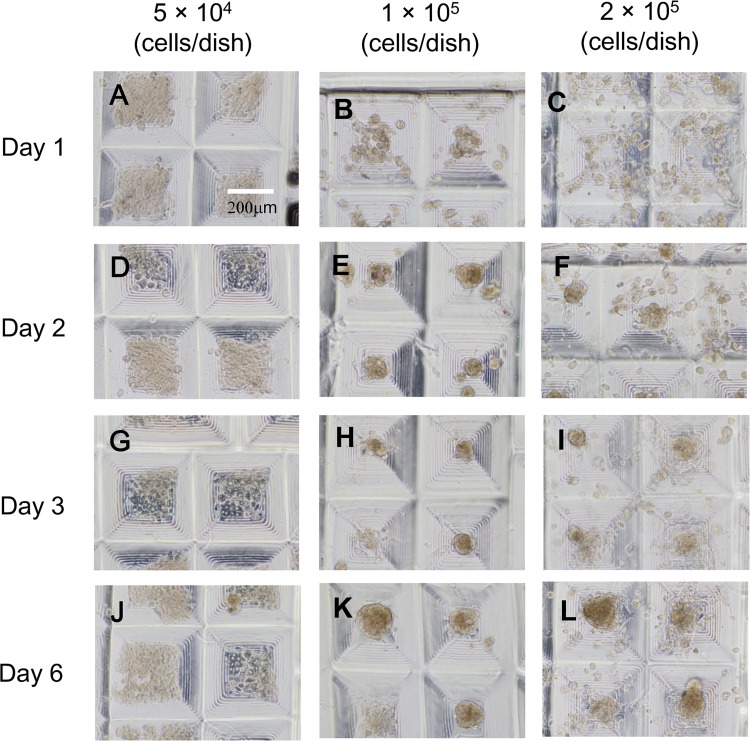

Subsequently, hepatocyte constructs were created using a 35-mm collagen-coated dish (Fig. 3). More cells adhered to the 35-mm collagen-coated dish compared with the 35-mm plastic one used as the bottom part of the TASCL device. At a low cell seeding density (5 × 104 cells/dish), seeded hepatocytes adhered to the bottom (Fig. 3D, G, and J), and some cells exhibited a cobblestone morphology similar to that in monolayer culture. At higher cell seeding densities (1 × 105 and 2 × 105 cells/plate), hepatocyte constructs of different sizes were obtained after 2 days of culture (Fig. 3E, F, H, I; and K, L). It was not possible to obtain hepatocyte constructs with similar morphology.

Figure 3.

Phase-contrast photomicrographs of primary mouse hepatocyte constructs created using combinatorial TASCL device and the bottom surface of the TASCL device employed as a 35-mm collagen-coated culture dish. Primary mouse hepatocytes at a density of 5 × 104 (A, D, G, and J), 1 × 105 (B, E, H, and K), and 2 × 105 cells (C, F, I, and L) were inoculated on a combinatorial TASCL device for 6 days. The culture periods were as follows: 1 day (A, B, and C), 2 days (D, E, and F), 3 days (G, H, and I), and 6 days (J, K, and L). Scale bar: 200 µm.

Hepatic Function of the 3D In Vitro Constructs of Primary Mouse Hepatocytes Created Using the TASCL Device

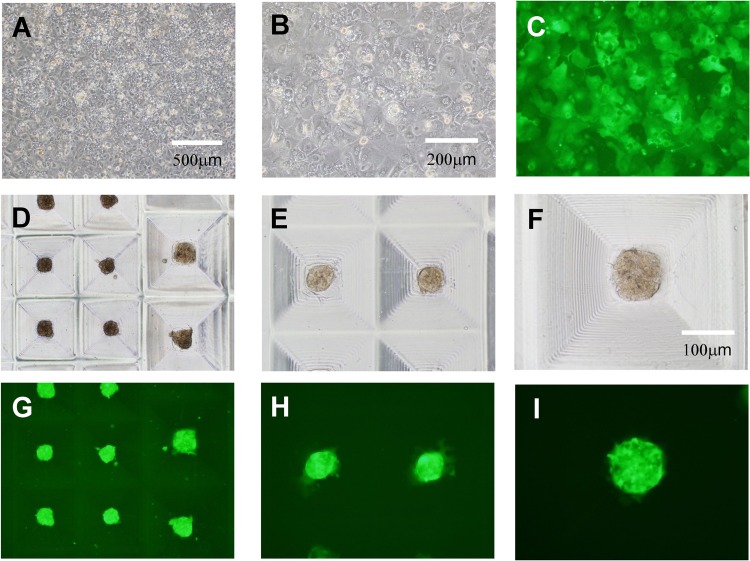

Based on the above results, we determined the preparation conditions for the formation of hepatocyte constructs using the TASCL device. A total of 2 × 105 cells were seeded in the TASCL device and cultured for 48 h. In the 2D monolayer culture, the cells exhibited a cobblestone morphology (Fig. 4A–C). By comparison, after 48 h of culture, the morphology of the hepatocyte constructs (Fig. 4D–F) included uniform sizes (about ɸ 100 μm–ɸ 200 μm). The calcein staining results confirmed that the construct consisted of living cells (Fig. 4G–I).

Figure 4.

Morphological examination of primary mouse hepatocyte created using the TASCL device or a collagen-coated culture dish. Hepatocytes were cultured on the TASCL device (hepatocyte constructs) and a collagen-coated culture dish (2D monolayer culture). A total of 2 × 105 cells were seeded on the TASCL device and cultured for 2 days. A 35-mm plastic culture dish was used as the bottom part of the TASCL device. The morphology of the hepatocytes treated with 2D monolayer culture is shown after 48 h of culture (A, B, and C). The morphology of the hepatocyte constructs is shown (D, E, and F). (C, G, H, and I) Fluorescent photomicrographs of (B, D, E, and F) after staining with calcein AM. Scale bars: 500 μm (A, D, and G), 200 μm (B, C, E, and H), and 100 μm (F and I).

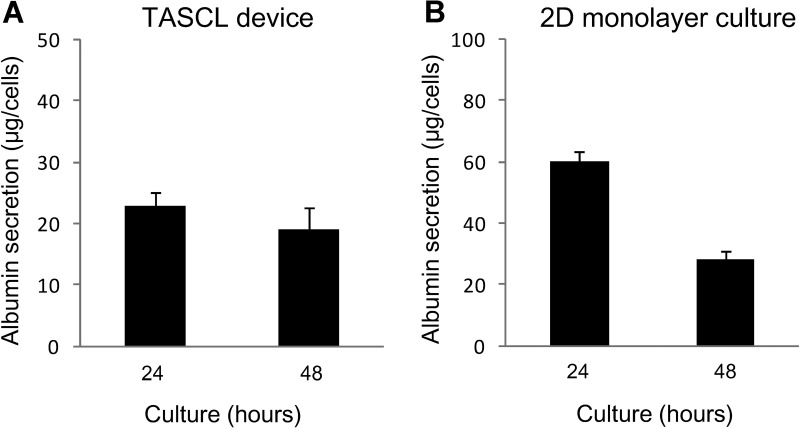

We also evaluated the albumin secretion by mouse hepatocytes in the TASCL device (Fig. 5A). A total of 2 × 105 cells were seeded in the TASCL device and were further cultured for 48 h. The amount of albumin secretion in the TASCL device was measured, and as a result, the activity did not significantly change from 24 to 48 h (Fig. 5A). The level of albumin synthesis in the 2D monolayer culture increased at 24 h, then gradually decreased at 48 h, and maintained at 50% of the peak activity level (Fig. 5B). Conventional 2D culture showed the same tendency for albumin secretion.

Figure 5.

Albumin secretion in primary mouse hepatocyte constructs created using the TASCL device. The level of albumin synthesis was measured after 24 h of accumulation. (A) Hepatocytes were incubated on the TASCL device for 24 h. (B) Hepatocytes were incubated on the collagen-coated dishes for 24 h. The data represent the mean and SD of three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

In recent years, the application of several hepatocellular 3D culture techniques with various matrices as promising tools for innovative drug development has been reported (4,7,8,14–17,26,32). It has also been previously reported that long-term culture is useful for maintaining the functions of hepatocytes that adhere to the matrix (4,22). Various methods for preparing artificial liver tissue consisting of hepatic cell aggregates have been attempted using biotechnology. In the present study, primary hepatocyte constructs were prepared using the TASCL device (10,11) fabricated according to MEMS technology. The TASCL device can be easily installed on various types of culture dishes with tweezers. We examined the cell constructs of the primary mouse hepatocytes by changing the bottom surface (plastic and collagen-coated dishes) of the TASCL device.

Using plastic dishes on the bottom surface of the combinatorial TASCL device, 3D hepatocyte constructs of uniform sizes (about ɸ 100 μm–ɸ 200 μm) were produced by increasing the seeding cell density of primary mouse hepatocytes (Fig. 2F, I, and L). The 3D hepatocyte constructs obtained using the TASCL device were alive and produced albumin (Figs. 4 and 5). On the other hand, partially adhered primary mouse hepatocytes exhibited a cobblestone morphology on the collagen-coated bottom of individual microwells using the combinatorial TASCL device (Fig. 3D, G, and J). By changing the bottom substrate of the TASCL device, the culture environment of the cell constructs was easily changed to a 3D environment. In this experiment, the size of individual microwells in the TASCL device was different (Fig. 1). Therefore, this device can be used as a screening tool to create uniform hepatocyte constructs. The combinatorial TASCL device described in this report can be used quickly and simply, and it will be useful for preparing hepatocyte constructs. In the future, we will report an application of the TASCL device taking into consideration properties of primary hepatocytes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would thank Ms. Rina Yokota and Ms. Yumie Koshidaka at Nagoya University for their technical assistance. This work was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI Grant No. 22650127, 25560248 (Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Exploratory Research), and JST PRESTO program. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Basma H.; Soto-Gutiérrez A.; Yannam G. R.; Liu L.; Ito R.; Yamamoto T.; Ellis E.; Carson S. D.; Sato S.; Chen Y.; Muirhead D.; Navarro-Álvarez N.; Wong R. J.; Roy-Chowdhury J.; Platt J. L.; Mercer D. F.; Miller J. D.; Strom S. C.; Kobayashi N.; Fox I. J. Differentiation and transplantation of human embryonic stem cell-derived hepatocytes. Gastroenterology 136:990–999; 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bonner-Weir S.; Taneja M.; Weir G. C.; Tatarkiewicz K.; Song K. H.; Sharma A.; O’Neil J. J. In vitro cultivation of human islets from expanded ductal tissue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97(14):7999–8004; 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen Y.; Soto-Gutiérrez A.; Navarro-Alvarez N.; Rivas-Carrillo J. D.; Yamatsuji T.; Shirakawa Y.; Tanaka N.; Basma H.; Fox I. J.; Kobayashi N. Instant hepatic differentiation of human embryonic stem cells using activin A and a deleted variant of HGF. Cell Transplant. 15:865–871; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Enosawa S.; Miyamoto Y.; Hirano A.; Suzuki S.; Kato N.; Yamada Y. Application of cell array 3D-culture system for cryopreserved human hepatocytes with low-attaching capability. Drug Metab. Rev. 39(Suppl. 1):342; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Enosawa S.; Miyamoto Y.; Kubota H.; Jomura T.; Ikeya T. Construction of artificial hepatic lobule-like spheroids on a three-dimensional culture. Cell Med. 3(1–3):19–23; 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Enosawa S.; Suzuki S.; Li X. K.; Okuyama T.; Fujino M.; Amemiya H. Higher efficiency of retrovirus transduction in the late stage of primary culture of hepatocytes from nontreated than from partially hepatectomized rat. Cell Transplant. 7:413–416; 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Feng Z. Q.; Chu X.; Huang N. P.; Wang T.; Wang Y.; Shi X.; Ding Y.; Gu Z. Z. The effect of nanofibrous galactosylated chitosan scaffolds on the formation of rat primary hepatocyte aggregates and the maintenance of liver function. Biomaterials. 30(14):2753–2763; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hewitt N. J.; Lech M. J.; Houston J. B.; Hallifax D.; Brown H. S.; Maurel P.; Kenna J. G.; Gustavsson L.; Lohmann C.; Skonberg C.; Guillouzo A.; Tuschl G.; Li A. P.; LeCluyse E.; Groothuis G. M.; Hengstler J. G. Primary hepatocytes: Current understanding of the regulation of metabolic enzymes and transporter proteins, and pharmaceutical practice for the use of hepatocytes in metabolism, enzyme induction, transporter, clearance, and hepatotoxicity studies. Drug Metab. Rev. 39(1):159–234; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hori Y.; Rulifson I. C.; Tsai B. C.; Heit J. J.; Cahoy J. D.; Kim S. K. Growth inhibitors promote differentiation of insulin-producing tissue from embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99(25):16105–16110; 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ikeuchi M.; Ikuta K. Method for producing different populations of molecules or fine particles with arbitrary distribution forms and distribution densities simultaneously and in quantity, and masking member therefore. United States Patent Application, US 2011/0229953 A1.

- 11. Ikeuchi M.; Oishi K.; Noguchi H.; Shuji H.; Koji I. Soft tapered stencil mask for combinatorial 3D cluster formation of stem cells. Proc. µTAS2010:641–643; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ishikawa T.; Banas A.; Hagiwara K.; Iwaguro H.; Ochiya T. Stem cells for hepatic regeneration: The role of adipose tissue derived mesenchymal stem cells. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 5(2):182–189; 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ishikawa T.; Banas A.; Teratani T.; Iwaguro H.; Ochiya T. Regenerative cells for transplantation in hepatic failure. Cell Transplant. 21(2–3):387–399; 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Janorkar A. V. Polymeric scaffold materials for two-dimensional and three-dimensional in vitro culture of hepatocytes. In: Kulshrestha A. S.; Mahapatro A.; Henderson L. A., eds. Biomaterials. Washington, DC: ACS Publications; 2010:1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Miyamoto Y.; Enosawa S.; Takeuchi T.; Takezawa T. Cryopreservation in situ of cell monolayers on collagen vitrigel membrane culture substrata: Ready-to-use preparation of primary hepatocytes and ES cells. Cell Transplant. 18:619–626; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Miyamoto Y.; Ikeya T.; Enosawa S. Preconditioned cell array optimized for a three-dimensional culture of hepatocytes. Cell Transplant. 18:677–681; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Miyamoto Y.; Koshidaka Y.; Noguchi H.; Oishi K.; Saito H.; Yukawa H.; Kaji N.; Ikeya T.; Iwata H.; Baba Y.; Murase K.; Hayashi S. Polysaccharide functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for cell labeling and tracking: A new three-dimensional cell-array system for toxicity testing. In: Nagarajan R., ed. Nanomaterials for Biomedicine. Washington, DC: ACS Publications; 2012:191–208. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Miyamoto Y.; Noguchi H.; Yukawa H.; Oishi K.; Matsushita K.; Iwata H.; Hayashi S. Cryopreservation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Med. 3(1–3):89–95; 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Miyamoto Y.; Oishi K.; Yukawa H.; Noguchi H.; Sasaki M.; Iwata H.; Hayashi S. Cryopreservation of human adipose tissue-derived stem/progenitor cells using the silk protein sericin. Cell Transplant. 21(2–3):617–622; 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Miyamoto Y.; Suzuki S.; Nomura K.; Enosawa S. Improvement of hepatocyte viability after cryopreservation by supplementation of long-chain oligosaccharide in the freezing medium in rats and humans. Cell Transplant. 15:911–919; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Miyamoto Y.; Teramoto N.; Hayashi S.; Enosawa S. An improvement in the attaching capability of cryopreserved human hepatocytes by a proteinaceous high molecule, Sericin, in the serum-free solution. Cell Transplant. 19:701–706; 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Otsuka H.; Hirano A.; Nagasaki Y.; Okano T.; Horiike Y.; Kataoka K. Two-dimensional multiarray formation of hepatocytes spheroids on a microfabricated PEG-brush surface. Chembiochem 5:850–855; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Peshwa M. V.; Wu F. J.; Sharp H. L.; Cerra F. B.; Hu W. S. Mechanistics of formation and ultrastructural evaluation of hepatocyte spheroids. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Anim. 32(4):197–203; 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sakai Y.; Nakazawa K. Technique for the control of spheroid diameter using microfabricated chips. Acta Biomater. 3(6):1033–1040; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Seglen P. O. Preparation of isolated rat liver cells. Methods Cell Biol. 13:29–83; 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sullivan J. P.; Gordon J. E.; Bou-Akl T.; Matthew H. W.; Palmer A. F. Enhanced oxygen delivery to primary hepatocytes within a hollow fiber bioreactor facilitated via hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers. Artif. Cells Blood Substit. Immobil. Biotechnol. 35(6):585–606; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Takahashi K.; Tanabe K.; Ohnuki M.; Narita M.; Ichisaka T.; Tomoda K.; Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 131(5):861–872; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Takebe T.; Sekine K.; Enomura M.; Koike H.; Kimura M.; Ogaeri T.; Zhang R. R.; Ueno Y.; Zheng Y. W.; Koike N.; Aoyama S.; Adachi Y.; Taniguchi H. Vascularized and functional human liver from an iPSC-derived organ bud transplant. Nature 499(7459):481–484; 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Takebe T.; Zhang R. R.; Koike H.; Kimura M.; Yoshizawa E.; Enomura M.; Koike N.; Sekine K.; Taniguchi H. Generation of a vascularized and functional human liver from an iPSC-derived organ bud transplant. Nat. Protoc. 9(2):396–409; 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thomson J. A.; Itskovitz-Eldor J.; Shapiro S. S.; Waknitz M. A.; Swiergiel J. J.; Marshall V. S.; Jones J. M. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science 282(5391):1145–1147; 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ungrin M. D.; Joshi C.; Nica A.; Bauwens C.; Zandstra P. W. Reproducible, ultra high-throughput formation of multicellular organization from single cell suspension-derived human embryonic stem cell aggregates. PLoS One 3(2):e1565; 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Walker T. M.; Rhodes P. C.; Westmoreland C. The differential cytotoxicity of methotrexate in rat hepatocyte monolayer and spheroid cultures. Toxicol. In Vitro 14(5):475–485; 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yukawa H.; Ikeuchi M.; Noguchi H.; Miyamoto Y.; Ikuta K.; Hayashi S. Embryonic body formation using the tapered soft stencil for cluster culture device. Biomaterials 32(15):3729–3738; 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]