Abstract

Objective

Dietary fructose is implicated in metabolic syndrome, but intervention studies are confounded by positive caloric balance, changes in adiposity, or artifactually high amounts. We determined whether isocaloric substitution of starch for sugar would improve metabolic parameters in Latino (n=27) and African-American (n=16) children with obesity and metabolic syndrome.

Methods

Participants consumed a diet for nine days to deliver comparable percentages of protein, fat, and carbohydrate as their self-reported diet; however, dietary sugar was reduced from 28% to 10%, and substituted with starch. Participants recorded daily weights, with calories adjusted for weight maintenance. Participants underwent dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) and oral glucose tolerance testing (OGTT) on Days 0 and 10. Biochemical analyses were controlled for weight change by repeated measures ANCOVA.

Results

Reductions in diastolic BP (−5 mmHg; p=0.002), lactate (−0.3 mmol/L; p<0.001), triglyceride and LDL-cholesterol (−46% and −0.3 mmol/L; p<0.001) were noted. Glucose tolerance and hyperinsulinemia improved (p<0.001). Weight reduced by 0.9±0.2 kg (p<0.001) and fat-free mass by 0.6 kg (p=0.04). Post-hoc sensitivity analysis demonstrates that results in the subcohort that did not lose weight (n=10) were directionally consistent

Conclusions

Isocaloric fructose restriction improved surrogate metabolic parameters in children with obesity and metabolic syndrome irrespective of weight change.

Keywords: obesity, metabolic syndrome, fructose, sugar, hyperinsulinemia, hyperlipidemia

Introduction

Chronic diseases such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and type 2 diabetes (T2DM) now occur in children, an age group that had never previously manifested such pathologies. In addition, dyslipidemia and hypertension, two risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD), are now common in childhood 1, 2. While these diseases clearly exhibit higher prevalence in children with obesity, they nonetheless occur in those with normal weight 3 Furthermore, the prevalence of diabetes is higher than obesity prevalence in some countries, such as India, Pakistan, and China 4; suggesting that calories alone do not explain this phenomenon It has been hypothesized that changes in dietary composition associated with the Western Diet are responsible for biochemical alterations which promote insulin resistance to foment these diseases, known collectively as metabolic syndrome 5. Fructose has attracted particular concern, due to several unique metabolic and neuroendocrine properties: 1) it is metabolized almost exclusively in the liver 6; 2) it serves as a substrate for de novo lipogenesis and drives hepatic triglyceride (TG) synthesis and accumulation 7, 8; 3) it engages in non-enzymatic fructation and reactive oxygen species formation which causes cellular dysfunction 9; 4) it does not suppress the hunger hormone ghrelin, resulting in excessive consumption 10; and 5) it stimulates the nucleus accumbens resulting in increased reward and continued ingestion 11. Short-term studies demonstrate that excessive oral fructose increases serum TG and visceral fat more than does its isomer glucose 12. However, previous clinical studies of orally administered fructose on surrogate markers of metabolic syndrome were confounded by the administration of excessive or pharmacologic doses and by the inability to isolate the metabolic effects of fructose from either its caloric content or its effects on weight gain and adiposity.

Instead, we assessed the effects of dietary sugar restriction with isocaloric substitution of starch (complex carbohydrate) on metabolic parameters in children with obesity with high habitual added sugar consumption who evidenced co-morbidity, so as to obviate concerns of dose, caloric equivalence, or effects on adiposity.

Methods

This study was approved by the UCSF Committee on Human Research and the Touro University Institutional Review Board, and listed as NCT01200043 on ClinicalTrials.gov. We restricted recruitment to Latino youth (who are known to be at higher risk for dyslipidemia and NAFLD) 13, and African-American youth (who are known to be at higher risk for T2DM and hypertension) 14, and who identified as high habitual sugar consumers (>15% sugar and >5% fructose).

Participants were identified primarily through the UCSF Weight Assessment for Teen and Child Health (WATCH) Clinic, an interdisciplinary obesity clinic dedicated to targeting metabolic dysfunction rather than caloric balance 15. Eligibility criteria included: 1) ages 8-18 years; 2) obesity (body mass index (BMI) z-score ≥+1.8); and 3) at least one other co-morbidity, including hypertension (systolic blood pressure (BP) >95th percentile for age and sex), hypertriglyceridemia (TG >95th percentile for age and sex), impaired fasting glucose (Hemoglobin A1c >6.0 or fasting glucose >5.55 mmol/L), hyperinsulinemia (fasting insulin >90 pmol/L or HOMA-IR >4.3), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) >40 U/L, or severe acanthosis nigricans. Exclusion criteria included: known diabetes, steroid medication use, any medication that affected insulin secretion or resistance, alcohol use, pregnancy, or neuroactive medications. Participants were recruited during initial clinic visits or from referrals from the community. Appropriate consent and assent were obtained in writing at the time of screening. Participants filled in food frequency questionnaires (FFQ) 16, 17 and were interviewed by a dietitian, from which their baseline macronutrient profiles (percent of calories as fat, protein, and carbohydrate; and fiber content as g/1000 kcal) were identified. We estimated energy requirements using formulas published by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) for weight maintenance in overweight boys and girls, ages 3 through 18 18. After the first 17 participants were studied, seven were noted to have lost >2% in weight, so caloric targets for each participant were increased by 10% thereafter.

Participants and guardians were told to continue their usual home diets until they came fasting to the UCSF Pediatric Clinical Research Center on Day 0, where anthropometric measurements were recorded. Blood pressure was obtained by automated monitor after a 15 minute rest period. Fasting blood samples were obtained through a saline lock. An oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) was performed by administering 75 gm glucose, and blood was drawn for glucose and insulin levels at 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes. Whole-body dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scanning was performed to assess bone, fat, and fat-free mass. All participants were provided a floor scale with instructions on how to collect, record, and report their weight each day, as well as store and prepare the study diet, and record their daily food intake for the following nine days. Participants were sent home with nine days of food (in three separate installments) prepared by the UCSF Clinical Research Service (CRS) Bionutrition Core to provide adequate calories to maintain their body weight. The menu was planned to restrict added sugar, while substituting other carbohydates such as those in fruit, bagels, cereal, pasta, and bread so that the percentage of calories consumed from carbohydrate was consistent with their baseline diet, but total dietary sugar and fructose were reduced to 10% and 4% of total calories, respectively. Additional food items were provided when weight loss was observed during daily fasting weight checks which were reported to the study dietitian each morning. Additional individualized instructions for maintaining weight stability were provided by phone, email or text, and at food pickup or delivery. On Day 10, participants returned with their final record of dietary intake and fasting blood specimens, OGTT, and DXA were repeated. Any additional or missed foods that were recorded on the diet checklists were added or subtracted from the total study diet intake calculation. The caloric and nutrient content of the study diet assigned and after intervention was calculated using the nutrient analyses software ProNutra 3.4 (Viocare) with USDA standard reference database 23.

Fasting clinical chemistries were measured in the UCSF clinical laboratory. All other specimens were processed and frozen for subsequent batch analysis. Plasma with sodium fluoride and potassium oxalate was used to measure for glucose and lactate concentrations (YSI 2300 Stat plus, Yellow Springs, OH, USA). Serum insulin concentrations were measured by chemiluminescence on a Siemens Immulite 2000 XPI platform, fasting lipids on a Beckman DXC-600 by blanked timed endpoint, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) by homogeneous immunoinhibition (Trinity Biotech) at Pennington Biomedical Research Center (Baton Rouge, LA, USA).

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SD. Normal distributions were tested by histogram, box-plot, q-norm plot, and Shapiro Wilk tests. To compare weight and DXA variables between Day 0 and Day 10, paired t-tests were used. Each analyte was evaluated for normality; when normal, repeated measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed on each biochemical parameter to control for weight change, and separate regression analysis was performed to obtain the β-coefficient (mean difference adjusted for weight change, with 95% confidence intervals). When data were not normally distributed, log transformation was performed to achieve normal distribution, and then the data were subjected to repeated measures ANCOVA. Resultant β-coefficients were converted back to the raw data scale for each parameter to reflect percent change in mean differences adjusted for weight change, with 95% confidence intervals. When data were not normally distributed and could not be log transformed, Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric testing was instead used for analysis. We also performed univariate regression analysis to investigate the association between change in weight and change in metabolic analytes; r2 values are reported to assess the change in the variance of each analyte versus change in weight. To assess the impact of the demographic variables (sex, age, Tanner stage, race/ethnicity), we re-ran the repeated measures ANCOVA models with each included as a single covariate, and with all included as multiple covariates in one model. For the glucose and insulin levels from the OGTT, we compared values at each time point using paired (Day 10 vs Day 0) t-tests. Post-hoc sensitivity analysis was performed for the 10 participants who did not lose weight during the study. All statistical tests were considered significant at p<0.05 based on two-tailed tests. All analyses were conducted with STATA version 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Day 0 and Day 10 clinical and anthropometric parameters are listed in Table 1. Fifty-two Latino and African-American participants were recruited. Two participants were found to be ineligible, five did not arrive for their Day 0 visit, and two completed Day 0 but did not return on Day 10, and are excluded from this analysis. We analyzed 43 pairs (27 Latino, 16 African-American, 16M, 27F) of baseline and 10-day post-intervention data (42 pairs for OGTT). The mean age of our cohort was 13.3±2.7 years, with BMI z-score 2.4±0.3. Pubertal status was Tanner 1 in five, Tanner 2-3 in 16, and Tanner 4-5 in 22 participants.

Table 1.

Anthropometric and DXA measurements (mean ± SD) on Day 0 and 10 (n=43)

| Day 0 | Day 10 | Mean Change (95%CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | 93.0 ± 22.1 | 92.1 ± 22.2 | −0.9 [−1.3, −0.6] | 0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 35.6 ± 6.4 | 35.2 ± 6.5 | −0.4 [−0.6, −0.2] | <0.001 |

| Fat mass (kg) | 43.9 ± 13.8 | 43.6 ± 14.2 | −0.3 [−0.8, +0.1] | 0.17 |

| Fat free mass (kg) | 48.3 ± 9.4 | 47.6 ± 8.9 | −0.6 [−1.2, −0.1] | 0.04 |

| Bone Mass§ (kg) | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 0 [−0.08, +0.05] | 0.63 |

Paired t-test, statistical significance p<0.05

Bone Mass excludes the 1 participant who underwent BOD-POD analysis instead of DXA due to excessive weight (n=42)

We attempted to match each participant's macronutrient intake profile during the nine-day intervention to their baseline diet. After adjustments for both uneaten and supplementary foods, the mean self-reported intake of the study diet was 29±6 kcal/kg with a macronutrient profile of 51±3% carbohydrate, 16±1% protein, and 33±3% fat (16% saturated, 9% polyunsaturated, 13% monounsaturated). Post-hoc analysis showed that, compared with the baseline macronutrient distribution determined by FFQ, the total percentage of carbohydrate intake on the study diet decreased by 4%, protein increased by 2%, and there was no change in percentage calories from fat. Within the carbohydrate fraction, dietary sugar intake reduced from 27.7±8.3% to 10.2±1.7%, and fructose from 11.7±4.0% to 3.8±0.5%, of daily calories. The consumption of dietary fiber of necessity increased from a daily mean of 9.3±2.2 g/1000kcal to 11.7±1.3 g/1000kcal. This study diet profile is consistent with recommendations by the IOM for macronutrients 18 and the World Health Organization for dietary sugar intake 19. This “child-friendly” study diet included various no- or low-sugar added processed foods including turkey hot dogs, pizza, bean burrritos, baked potato chips, and popcorn that were purchased at local supermarkets.

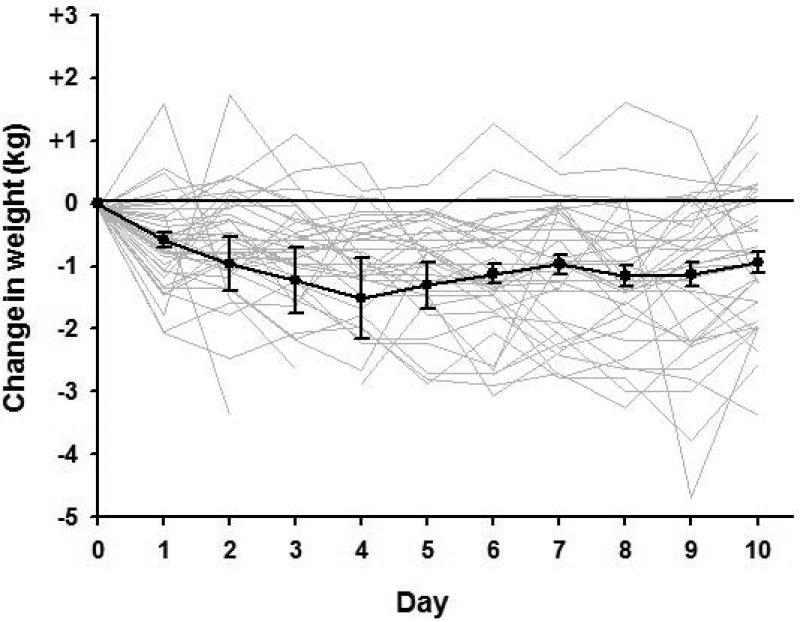

Despite intensive efforts to maintain each participant's body weight at baseline levels, weight decreased by 0.9±0.2 kg (1%, p=0.001) over the 10 days of intervention. Of the 43 participants, consumption of the study diet ranged from 75% to 115% of calories assigned; 33 reported that they were unable to consume all of the food provided for weight maintenance. Individual weight curves and the mean pattern of weight change (Figure 1) suggests that weight loss occurred within the first four days, with subsequent return toward baseline and stabilization thereafter, arguing for acute water loss and against persistent caloric deficit as the cause of the weight change. Comparison of DXA data (Table 1) demonstrated that fat and bone mass did not change significantly during the 10-day study period, although fat-free mass reduced by 0.6 kg (p=0.04).

Figure 1.

Change in weight from baseline in the 43 participants over the 10 days of study. Individual weight change curves are in light gray, while mean±SEM for the entire cohort are in black.

All subsequent physiologic and biochemical analyses that were normally distributed, either before or after log transformation, were adjusted for weight change by repeated measures ANCOVA. Our results did not differ when we controlled for sex, age, Tanner stage, and/or race/ethnicity. Weight change itself was not significant as a covariate in any of the repeated measures ANCOVAs. Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) was not normally distributed and was analysed by Kruskal-Wallis testing.

Systolic BP did not change (p=0.42) over the ten days. However, diastolic BP decreased signficantly by 4.9 mmHg (p=0.002). Heart rate (HR) tended to decline non-significantly by 2.8 bpm (p=0.12). Interestingly, uric acid increased over the ten days of intervention by 17.8 μmol/L (p=0.001).

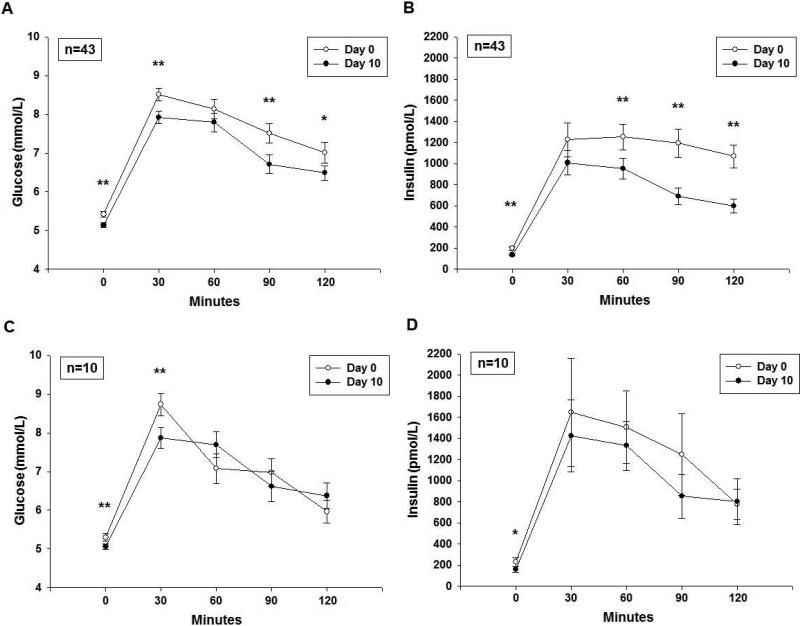

Glucose and insulin responses to OGTT are shown in Figure 2a,b. Fasting glucose decreased by 0.3 mmol/L (p <0.001), while glucose area under the curve (AUC) decreased by 7.3% or 67.2 mmol/L/120min (p = 0.001). Fasting insulin decreased by 53% (p <0.001), and HOMA-IR decreased by 58% (p <0.001). Peak insulin decreased by 56% (p <0.001) and insulin AUC reduced by 57% (p<0.001), implying reduction in hyperinsulinemia.

Figure 2.

a) Glucose, and b) insulin responses (Mean±SEM) to OGTT on Day 0 and 10 for all 43 participants. c) Glucose, and d) insulin responses to OGTT on Day 0 and 10 for the ten participants in the post-hoc sensitivity analysis who gained weight during the study interval.

* p<0.05 paired t-test (Day 10 vs. Day 0) at each individual time point

** p<0.01 paired t-test (Day 10 vs. Day 0) at each individual time point

The results of other biochemical analyses are shown in Table 2. Fasting TG levels decreased by 46% (p= 0.002), low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) decreased by 0.3 mmol/L (p< 0.001), and HDL-C reduced by 0.1 mmol/L (p< 0.001). Serum free fatty acids increased by 0.12 mmol/L (p<0.001), suggesting increases in peripheral lipolysis and increases in flow of fatty acid for oxidation. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) tended to decline non-significantly by 13% (p = 0.09), while AST declined significantly by 3.6 U/L (p= 0.02 by Kruskal-Wallis). Fasting lactate on Day 0 was 1.2 ± 0.4 mmol/L, and decreased by 0.3 mmol/L, (p< 0.001), and lactate AUC decreased by 19.5% or 31.2 mmol/L/120min (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Biochemical measurements (mean ± SD) on Day 0 and 10 (n=43)

| Day 0 | Day 10 | β-coefficient (Adjusted Change) [95% CI] | p value | R2** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 83.1 ± 10.7 | 80.1 ± 11.3 | −2.8 [−6.5, +0.9] | 0.13 | 0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 122.6 ± 10.5 | 121.1 ± 9.9 | − 1.39 [−4.9, +2.1] | 0.43 | 0.002 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 68.8 ± 8.9 | 63.7 ± 7.5 | − 4.9 [−8.1, −1.8] | 0.003 | 0.03 |

| Mean arterial blood pressure (mmHg) | 86.7 ± 7.7 | 82.9 ± 7.3 | −2.8 [−6.4, +0.8] | <0.001 | 0.01 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 5.4 ± 0.5 | 5.1 ± 0.4 | −0.3 [−0.4, −0.2] | <0.001 | 0.04 |

| Glucose AUC (mmol/L/120 min) | 911.9 ± 130.9 | 845.3 ± 130.4 | −67.2 [−105.5, −28.9] | < 0.001 | 0.09 |

| Peak glucose during OGTT (mmol/L) | 9.1 ± 1.4 | 8.3 ± 1.3 | −0.8 [−1.2, −8.0] | <0.001 | 0.03 |

| Fasting lactate (mmol/L) | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | −0.3 [−0.5, −0.2] | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| Lactate AUC (mmol/L/120 min) | 160.0 ± 34.5 | 129.0 ± 34.5 | −31.2 [−41.9, −20.5] | <0.001 | 0.01 |

| Fasting insulin (pmol/L)¥ | 195.6 ± 115.2 | 135.6 ± 63.0 | −53% [−65, −36] | <0.001 | 0.07 |

| Insulin AUC¥ (pmol/L/120 min) | 131760 ± 81240 | 89580 ± 53280 | −57% [−71, −36] | <0.001 | 0.07 |

| HOMA-IR¥ | 7.9 ± 4.8 | 5.2 ± 2.6 | −58% [−70, −43 ] | <0.001 | 0.07 |

| Peak insulin during OGTT¥ (pmol/L) | 1645.2 ± 1020.0 | 1172.8 ± 786.8 | −56% [−69, −36] | <0.001 | 0.09 |

| AST (U/L)* | 27.4 ± 14.1 | 23.8 ± 8.9 | 0.02 | 0.04 | |

| ALT (U/L)¥ | 28.9 ± 22.8 | 26.7 ± 19.6 | −13% [−25, +0.2] | 0.09 | 0.02 |

| BUN | 3.5 ± 0.9 | 3.6 ± 1.1 | 0.1 [−0.2, +0.4] | 0.56 | 0.06 |

| Creatinine | 53.0 ± 8.8 | 53.0 ± 8.8 | 0 [−0.9, +2.7] | 0.41 | 0.001 |

| Fasting uric acid (mmol/L) | 315.2653.5 | 333.1653.5 | 117.8 [+8.3, +32.1] | 0.001 | 0.08 |

| Fasting Triglycerides¥ (mmol/L) | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | − 46% [−62, −25] | 0.002 | 0.08 |

| Fasting LDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 2.4 ± 0.6 | 2.1 ± 0.6 | −0.3 [−0.4, −0.1] | <0.001 | 0.003 |

| Fasting HDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | −0.1 [−0.2, −0.1] | <0.001 | 0.05 |

| Fasting free fatty acids (mmol/L) | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | +0.1 [+0.1, +0.2] | <0.001 | 0.07 |

Statistical significance p<0.05 after adjustment for weight change by repeated measures ANCOVA

Non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis, statistical significance p<0.05

Coefficient of determination for univariate regression analysis between change in biochemcial parameters and change in weight

Parameters not normally distributed and log transformed for analysis only, mean change and 95% CI are reported as percent change.

To provide assurance that the effects of sugar restriction were not due exclusively to the modest weight loss evidenced during the study, we performed univariate regression between the change in weight versus the change in metabolic analytes. We saw no relationship other than a positive association between change in glucose AUC and change in weight (p=0.045). Furthermore, we analyzed the 10 participants who did not lose weight over the ten days in a separate post-hoc sensitivity analysis, and the results were directionally consistent as compared with the entire cohort (Table 3). Notably, hyperinsulinemia significantly improved in this subcohort as well (Figure 2d).

Table 3.

Sensitivity analysis of the 10 children who did not lose weight; measurements (mean ± SD) on Day 0 and 10

| Day 0 | Day 10 | β-coefficient (Adjusted Change) [95% CI] | p value | R2** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 5.3 ± 0.3 | 5.1 ± 0.2 | −0.2 [−0.4, −0.1] | 0.01 | 0.31 |

| Glucose AUC (mmol/L/120 min) | 854.7 ± 74.4 | 836.4 ± 95.5 | −18.3 [−79.6, +42.2] | 0.51 | 0.11 |

| Peak glucose during OGTT (mmol/L) | 8.7 ± 0.9 | 8.0 ± 0.9 | −0.7 [−1.3, −0.2] | 0.01 | 0.19 |

| Fasting lactate (mmol/L) | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 0.9 ± 0.4 | −0.5 [−0.8, −0.1] | 0.01 | 0.56 |

| Lactate AUC (mmol/L/120min) | 161.9 ± 34.2 | 128.5 ± 28.1 | −33.4 [−58.2, −8.6] | 0.01 | 0.09 |

| Fasting insulin (pmol/L)¥ | 228.6 ± 141.0 | 159.6 ± 76.2 | −54% [−76, −11] | 0.04 | 0.30 |

| Insulin AUC¥ (pmol/L/120 min) | 151080 ± 112620 | 123180 ± 74400 | −32% [−67, +43] | 0.24 | 0.01 |

| HOMA-IR¥ | 9.0 ± 5.7 | 5.9 ± 2.9 | −58% [−78, −21] | 0.03 | 0.25 |

| Peak Insulin during OGTT¥ (pmol/L) | 2019.0 ± 1399.2 | 1614.0 ± 1129.8 | −41% [−71, +21] | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| AST (U/L)* | 25.9 ± 6.9 | 21.1 ± 3.9 | 0.08 | 0.001 | |

| ALT (U/L)¥ | 25.2 ± 13.1 | 22.5 ± 11.5 | −21% [−51, +24] | 0.42 | 0.001 |

| BUN | 3.3 ± 0.6 | 3.7 ± 0.9 | +0.4 [−0.1, +0.8] | 0.11 | 0.002 |

| Creatinine | 53.0 ± 8.8 | 53.0 ± 8.8 | + 8.8 [−3.5, +6.2] | 0.61 | 0.25 |

| Fasting uric acid (μmol/L) | 315.2 ± 65.4 | 327.1 ± 47.6 | +11.9 [−5.9, +29.7] | 0.14 | 0.04 |

| Fasting triglycerides¥ (mmol/L) | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.4 | −33% [−69, +55] | 0.30 | 0.17 |

| Fasting LDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.4 | −1.2 [−0.4, +0.1] | 0.26 | 0.04 |

| Fasting HDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | −0.05 [−0.14, +0.04] | 0.26 | 0.01 |

| Fasting free fatty acids (mmol/L) | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | +0.1 [−0.04, +0.17] | 0.19 | 0.15 |

Statistical significance p<0.05 after adjustment for weight change by repeated measures ANCOVA

Non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis, statistical significance p<0.05

Coefficient of determination for univariate regression analysis between change in biochemcial parameters and change in weight

Parameters not normally distributed and log transformed for analysis only, mean change and 95% CI are reported as percent change.

Discussion

Epidemiological studies have linked dietary fructose consumption, either as sucrose or high-fructose corn syrup, with the various co-morbidities of metabolic syndrome, including CVD, T2DM, and NAFLD 4, 20, 21. However, proof of causation has been difficult to establish for four reasons. First, long-term randomized controlled trials of dietary fructose consumption are difficult because in real world settings, there is no integrated biomarker for dietary fructose or measure of compliance 22. Second, short-term experimental protocols feature an excessive dose of oral fructose 23. Third, recall bias underestimating sugar consumption is the norm in epidemiologic studies 24; therefore using recall data in order to conduct externally controlled studies becomes problematic. Fourth, investigators routinely conflate the metabolic detriment of the fructose molecule with its caloric equivalence or with its effects on adiposity, either of which are assumed to be the intermediate cause of the pathology 25.

To circumvent these issues, we instead chose to evaluate whether short-term isocaloric restriction of dietary fructose in children with obesity and metabolic syndrome would mitigate metabolic pathology. However, to demonstrate a primary effect, we had to substitute dietary added sugar (glucose-fructose) calorie-for-calorie with dietary starch in order to maintain equivalence for both calories, carbohydrate content, and weight. We anticipated that a 9-day fructose restriction interval would be sufficient, based on previous work by our group in healthy adults demonstrating changes in liver fat within seven days of isocaloric fructose restriction 8.

Fructose has been suggested to increase BP 26 by enhancing sympathetic activity 27, decreasing urinary sodium excretion 28, increasing gut sodium absorption 29, and increasing uric acid (the endogenous inhibitor of endothelial nitric oxide synthase) 30. Fructose has been associated with both systolic and diastolic BP increase in children 31, 32. Our participants’ diastolic BP declined significantly. A reduction in diastolic BP suggests decreased volume status which would normally trigger a compensatory increase in HR to maintain cardiac output. Our participants’ weight loss occurred during the first 4 days (suggesting water loss) and then returned toward baseline (Fig. 1). However, the non-significant decline in HR suggested that the diastolic BP reduction was not due to changes in volume status. In addition, blood urea nitrogen and creatinine did not change (Table 2). Interestingly, our participants’ uric acid levels increased, despite the significant reduction in diastolic BP. We cannot attribute this increase to hemoconcentration, protein intake, or weight loss.

Fasting glucose and glucose AUC improved, implying improved glucose tolerance. Fasting, peak, and insulin AUC reduced, implying enhanced insulin sensitivity. These improvements were unrelated to calories or weight change.

We also documented improvement in fasting serum lipids. TG were reduced on the fructose-restricted diet, consistent with previously reported declines in de novo lipogenesis and very-low density lipoprotein (VLDL) production and release from the liver 8, 33. LDL-C reduced consistent with VLDL reduction. Fasting free fatty acids increased, consistent with peripheral lipolysis.

Fasting lactate and lactate AUC decreased after fructose restriction. Although clinical norms for lactate in children vary, high lactate is seen in patients with decreased mitochondrial number or throughput, e.g. those with ischemia or anoxia, cancer (due to the Warburg effect) 34, or in those with mitochondrial encephalomyopathy (Kearns-Sayre, MELAS) 35. Fasting lactate and lactate AUC reduced significantly either through decreased lactate production or increased lactate clearance. ALT, a marker of liver fat, did not decline significantly. However, AST, a marker of liver mitochondrial integrity 36, 37, declined significantly by Day 10. While each of these indices are indirect, the simultaneous reduction of AST, lactate, and TG suggests that hepatic mitochondria may be capable of improved disposal of pyruvate. We proffer the testable hypothesis that excessive dietary fructose causes hepatic mitochondrial overload which results in metabolic syndrome, and that individual manifestations of metabolic syndrome may be due to organ-specific mitochondrial overload.

This study manifests several strengths. Rather than studying excessive acute oral fructose administration in normal participants, or the addition of fructose to a normal caloric allotment 12, 38, we instead evaluated restriction of added dietary sugar in children with metabolic syndrome to see if their metabolic dysfunction would resolve — an endpoint with clinical relevance, and with little chance for charges of artifact. If our participants had been non-compliant with the dietary regimen, it would only have diluted our findings. To reduce systematic bias, we maintained investigator blinding on all data until final statistical analysis.

However, there are some limitations to our paradigm. Athough inclusion of a separate external control group would have been optimal, it would have presented novel challenges of its own, such as: 1) if subjects under- or over-estimated their baseline fructose consumption, then providing them their reported daily fructose content would be problematic; 2) altering each subject's diet while trying to maintain the baseline fructose content would require changes in liquid vs. solid, which may also result in caloric change, altered absorption, and altered satiety; and 3) our participants were all patients in an obesity program. We did not believe that maintaining fructose at the same level, even within a study, is commensurate with the message that the change in macronutrient composition is important for their health, and in order to use the study as an “educational moment”. Furthermore, others have looked longitudinally at children with obesity over time without any intervention, but still within the confines of a study, and had seen no changes in metabolic outcomes 39. Rather, each participant served as his or her own control. Our paradigm of dietary sugar and fructose restriction, which included mid-study dietary adjustments to compensate for weight loss, resulted in a 4% decrease in percentage of calories from carbohydrate, a 2% increase in percentage of calories from protein, and a small increase in dietary fiber, which could have reduced macronutrient absorption 18, flux of fructose to the liver, and also increased satiety. Recognizing that consumption data by recall is routinely underestimated 24, we made every effort to maintain our participants’ baseline weight throughout the 10-day study interval, and even increased the caloric allotment partway through the cohort, yet a decline of 0.9±0.2 kg was noted during the ten days. Furthermore, this reduction was documented by a 0.6 kg change in fat-free mass on DXA. One potential concern is that the weight loss over the 10-day study interval was a manifestation of unintended caloric deficit, and that this weight loss alone resulted in metabolic improvement. Although we cannot determine whether this weight loss was muscle or water or combination thereof, the temporal pattern of weight change argues against persistent caloric deficit (Fig. 1); and it is unlikely that a reduction of this magnitude in either compartment would improve metabolic health. To control for weight loss: 1) regression of change in metabolic analytes (except for glucose AUC) versus change in weight showed no significance (data not shown); 2) all analytes (except AST) were adjusted for changes in weight by repeated measures ANCOVA (Table 2); 3) sensitivity analysis on the subcohort who gained weight (Table 3; Fig. 2c,d) demonstrated directionally equivalent metabolic improvement, especially in hyperinsulinemia, suggesting that the effects were primarily due to fructose restriction rather than weight loss.

Our econometric analysis ascertained that sugar meets the Bradford Hill criteria for causation for diabetes, including dose, duration, directionality, and precedence 4. This study bolsters this assertion, and supports change in public health policy regarding sugar intake and food labeling.

Conclusion

Concerns surrounding the role of sugar consumption in chronic disease have previously focused on its caloric equivalence, and its role in fomenting increases in weight. Furthermore, previous clinical studies have relied upon excessive sugar administration, which introduces experimental artifact. This study mitigates all three of these concerns, by intervening in children who are already sick with metabolic syndrome, and by adjusting for effects of calories, weight gain, and adiposity. This study argues that the health detriments of sugar, and fructose in specific, are independent of its caloric value or effects on weight. Further studies will be required to determine whether sugar restriction alone can impact metabolic syndrome in adults, and whether such effects are short-lived or long-term.

Study Importance.

What is already known about this subject?

Dietary sugar consumption is implicated in the pathogenesis of metabolic syndrome.

Epidemiologic and prospective cohort data support a relationship, but causation is difficult to prove.

Controlled clinical studies have been confounded by other factors, such as ingestion of artifactually high amounts (dose), positive caloric balance, or changes in adiposity.

What does your study add?

We mitigated concerns about dose by removing added sugar from the diet of affected children.

We mitigated concerns about calories by replacing the added sugar with starch.

We mitigated concerns of changes in adiposity by using a paradigm to maintain weight stability.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants and parents/caregivers who volunteered for this study. Thanks is also given to all the UCSF Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute (CTSI) Pediatric and Adult CRS Staff (Jean Addis, Sarah Fuerstenau, Erin Matsuda, Grace Mausisa, Abigail Sobejana, Grady Kimes, Erin Miller, Raquel Herrera, Tamara Williamson, John Duda, Caitlin Sheets) who participated in this study, as well as the Bionutrition staff, Jennifer Culp and Monique Schloetter, who planned and prepared the food for this study. A special thank you to Drs. Emily Perito and Patrika Tsai. We also thank Arianna Pham, Davis Tang, Ari Simon, Moises Velasco-Alin, and Karen Pan. Special acknowledgment is given to Drs. Zea Malawa and Tami Hendriksz who helped recruit patients. Thanks to Laurie Herraiz, RD, who helped design and implement the protocol. And our greatest thanks is given to our wonderful WATCH clinic coordinators, who helped screen patients and implement this protocol, including Rachel Lipman, CPNP, Kelly Jordan (medical student at Tufts), Sally Elliott (medical student at UCLA), and Katrina Koslov, PhD (medical student at UCLA).

Funding: NIH (R01DK089216), UCSF CTSI (NCATS–UL1-TR00004), and Touro University.

Authors also thank Arianna Pham, Davis Tang, Ari Simon, Moises Velasco-Alin, Luis Rodriguez, and Karen Pan. Special acknowledgment is given to Drs. Zea Malawa and Tami Hendriksz who helped recruit patients. Thanks to Laurie Herraiz, RD, who helped design and implement the protocol. The authors also thank WATCH clinic coordinators, who helped screen patients and

Footnotes

Disclosure: None of the authors report any conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions:

All authors had access to the study data, and are responsible for the conclusions.

Study concept and design: Lustig, Schwarz, Mulligan.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Lustig.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Erkin-Cakmak, Mulligan.

Obtained funding: Lustig, Schwarz, Noworolski, Gugliucci, Mulligan.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Lustig, Schwarz, Mulligan, Gugliucci, Tai, Wen.

Study supervision: Lustig, Schwarz, Mulligan.

Trial Registration: Metabolic Impact of Fructose Restriction in Obese Children, https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01200043?term=NCT01200043&rank=1

References

- 1.Sorof JM, Lai D, Turner J, Poffenbarger T, Portman RJ. Overweight, ethnicity, and the prevalence of hypertension in school-aged children. Pediatrics. 2004;113:475–482. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.3.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kohen-Avramoglu R, Theriault A, Adeli K. Emergence of the metabolic syndrome in childhood: an epidemiological overview and mechanistic link to dyslipidemia. Clin Biochem. 2003;36:413–420. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(03)00038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwimmer JB, Deutsch R, Rauch JB, Behlung C, Newbury R, Lavine JE. Obesity, insulin resistance, and other clinicopathological correlates of pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Pediatr. 2005;143:500–505. doi: 10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00325-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basu S, Yoffe P, Hills N, Lustig RH. The relationship of sugar to population-level diabetes prevalence: an econometric analysis of repeated cross-sectional data. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57873. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiss R, Bremer AA, Lustig RH. Braaten D, editor. What is metabolic syndrome, and why are children getting it? Year in Diabetes and Obesity, 2012. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2013;1281:123–140. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim HS, Paik HY, Lee KU, Lee HK, Min HK. Effects of several simple sugars on serum glucose and serum fructose levels in normal and diabetic subjects. Diab Res Clin Pract. 1988;4:281–287. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(88)80030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim JS, Mietus-Snyder M, Valente A, Schwarz JM, Lustig RH. The role of fructose in the pathogenesis of NAFLD and the metabolic syndrome. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:251–264. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwarz JM, Noworolski SM, Wen MJ, Dyachenko A, Prior JL, Weinberg ME, et al. Effect of a high-fructose weight-maintaining diet on lipogenesis and liver fat. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:2434–2442. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schalkwijk CG, Stehouwer CD, van Hinsbergh VW. Fructose-mediated non-enzymatic glycation: sweet coupling or bad modification. Diabetes Metab Res. 2004;20:369–382. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Name M, Giannini C, Santoro N, Jastreboff AM, Kubat J, Li F, et al. Blunted suppression of acyl-ghrelin in response to fructose ingestion in obese adolescents: The role of insulin resistance. Obesity. 2015;23:653–661. doi: 10.1002/oby.21019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Page KA, Chan O, Arora J, Belfort-Deaguiar R, Dzuira J, Roehmholdt B, et al. Effects of fructose vs glucose on regional cerebral blood flow in brain regions involved with appetite and reward pathways. JAMA. 2013;309:63–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.116975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanhope KL, Schwarz JM, Keim NL, Griffen SC, Bremer AA, Graham JL, et al. Consuming fructose-, not glucose-sweetened beverages increases visceral adiposity and lipids and decreases insulin sensitivity in overweight/obese humans. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1322–1334. doi: 10.1172/JCI37385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Louthan MV, Theriot JA, Zimmerman E, Stutts JT, McClain CJ. Decreased prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in black obese children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41:426–429. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000177314.65824.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bacha F, Saad R, Gungor N, Janosky J, Arslanian SA. Obesity, regional fat distribution, and syndrome X in obese black versus white adolescents: race differential in diabetogenic and atherogenic risk factors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:2534–2540. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madsen KA, Garber AK, Mietus-Snyder ML, Valente JK, Tran CT, Wlasiuk L, et al. A lifestyle intervention for pediatric obesity: efficacy and behavioral and biochemical predictors of response. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2009;22:805–814. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2009.22.9.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neuhouser ML, Lilley S, Lund A, Johnson DB. Development and validation of a beverage and snack questionnaire for use in evaluation of school nutrition policies. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:1587–1592. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.06.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cullen KW, Watson K, Zakeri I. Relative reliability and validity of the Block Kids Questionnaire among youth aged 10 to 17 years. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:862–866. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Food and Nutrition Board . Dietary Reference Intakes: Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients) Institute of Medicine; Washington, D.C.: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guideline: Sugars intake for adults and children. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang Q, Zhang Z, Edward Gregg E, Flanders WD, Merritt R, Hu FB. Added sugar intake and cardiovascular diseases mortality among U.S. adults. JAMA Int Med. 2014;174:516–524. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ouyang X, Cirillo P, Sautin Y, McCall S, Bruchette JL, Diehl AM, et al. Fructose consumption as a risk factor for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2008;48:993–999. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hedrick VE, Dietrich AM, Estabrooks PA, Savla J, Serrano E, BM. D. Dietary biomarkers: advances, limitations and future directions. Nutr J. 2012;11:109. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-11-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stanhope KL, Havel PJ. Endocrine and metabolic effects of consuming beverages sweetened with fructose, glucose, sucrose, or high-fructose corn syrup. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:1733S–1737S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.25825D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rangan A, Allman-Farinelli M, Donohoe E, Gill T. Misreporting of energy intake in the 2007 Australian Children's Survey: differences in the reporting of food types between plausible, under- and over-reporters of energy intake. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2014;27:450–458. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sievenpiper JL, de Souza RJ RJ, Mirrahimi A, et al. Effect of fructose on body weight in controlled feeding trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Int Med. 2012;156:291–304. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-4-201202210-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fiaschi E, Baggio B, Favaro S, Antonello A, Camerin E, Todesco S, et al. Fructose-induced hyperuricemia in essential hypertension. Metabolism. 1977;26:1219–1223. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(77)90114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brito JO, Ponciano K, Figueroa D, et al. Parasympathetic dysfunction is associated with insulin resistance in fructose-fed female rats. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2008;41:804–808. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2008005000030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rebello T, Hodges RE, Smith JL. Short-term effects of various sugars on antinatriuresis and blood pressure changes in normotensive young men. Am J Clin Nutr. 1983;38:84–94. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/38.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh AK, Amlal H, Haas PJ, et al. Fructose-induced hypertension: essential role of chloride and fructose absorbing transporters PAT1 and Glut5. Kidney Int. 2008;74:438–447. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson RJ, Segal MS, Sautin Y, Nakagawa T, Feig DI, Kang DH, et al. Potential role of sugar (fructose) in the epidemic of hypertension, obesity and the metabolic syndrome, diabetes, kidney disease, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:899–906. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.4.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen S, Choi HK, Lustig RH, Hsu CY. Sugar sweetened beverages, serum uric acid, and blood pressure in adolescents. J Pediatr. 2009;154:807–813. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kell KP, Cardel MI, Bohan Brown MM, Fernandez JR. Added sugars in the diet are positively associated with diastolic blood pressure and triglycerides in children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100:46–52. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.076505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Faeh D, Minehira K, Schwarz JM, Periasami R, Seongsu P, Tappy L. Effect of fructose overfeeding and fish oil administration on hepatic de novo lipogenesis and insulin sensitivity in healthy men. Diabetes. 2005;54:1907–1913. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.7.1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seyfried TN, Shelton LM. Cancer as a metabolic disease. Nutr Metab. 2010:27. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-7-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Treem WR, Sokol RJ. Disorders of the mitochondria. Semin Liver Dis. 1998;18:237–253. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kojima H, Sakurai S, Uemura M, Fukui H, Morimoto H, Tamagawa Y. Mitochondrial abnormality and oxidative stress in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(1 Suppl):S61–S66. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liangpunsakul S, Lai X, Ross RA, Yu Z, Modlik E, Westerhold C, et al. Novel serum biomarkers for detection of excessive alcohol use. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39:556–565. doi: 10.1111/acer.12654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maersk M, Belza A, Stødkilde-Jorgensen H, et al. Sucrose-sweetened beverages increase fat storage in the liver, muscle, and visceral fat depot: a 6-mo randomized intervention study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:283–289. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.022533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uysai Y, Wolters B, Knop C, Reinehr T. Components of the metabolic syndrome are negative predictors of weight loss in obese children with lifestyle intervention. Clin Nutr. 2014;33:620–625. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]