Abstract

The role of PDGF-B and its receptor in meningeal tumorigenesis is not clear. We investigated the role of PDGF-B in mouse meningioma development by generating autocrine stimulation of the arachnoid through the platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) using the RCAStv-a system. To specifically target arachnoid cells, the cells of origin of meningioma, we generated the PGDStv-a mouse (Prostaglandin D synthase). Forced expression of PDGF-B in arachnoid cells in vivo induced the formation of Grade I meningiomas in 27% of mice by 8 months of age. In vitro, PDGF-B overexpression in PGDS-positive arachnoid cells lead to increased proliferation.

We found a correlation of PDGFR-B expression and NF2 inactivation in a cohort of human meningiomas, and we showed that, in mice, Nf2 loss and PDGF over-expression in arachnoid cells induced meningioma malignant transformation, with 40% of Grade II meningiomas. In these mice, additional loss of Cdkn2ab resulted in a higher incidence of malignant meningiomas with 60% of Grade II and 30% of Grade III meningiomas. These data suggest that chronic autocrine PDGF signaling can promote proliferation of arachnoid cells and is potentially sufficient to induce meningiomagenesis. Loss of Nf2 and Cdkn2ab have synergistic effects with PDGF-B overexpression promoting meningioma malignant transformation.

Keywords: meningioma, PDGF, Nf2, mouse model, RCAS

INTRODUCTION

Meningiomas account for approximately one-third of all primary central nervous system tumors and are the most common brain tumor in adults over 35 years of age [1]. Most meningiomas are benign and do not recur after complete surgical resection, resulting in prolonged disease free survival and low morbidity. In contrast, a subset of recurrent and/or histologically aggressive meningiomas (15–25% of tumors, WHO Grade II and III) presents with high morbidity and mortality [2–4], and repeated surgeries, radiosurgery/radiotherapy are the only option. Despite recent advances in understanding molecular mechanisms of meningioma development [5, 6], there is no available drug treatment.

We have demonstrated that Nf2 loss in arachnoid cells is sufficient to initiate meningioma development in mice [7], and identified a PGDS(Prostaglandin D2 synthase)-positive arachnoid cell as the cell of origin of meningioma [8]. Moreover, as in humans, Nf2 and Cdkn2ab loss cooperate to promote progression to histologically aggressive meningiomas [9, 10].

In human meningioma, there is accumulating evidence that platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) stimulates tumorigenesis. PDGF ligands AA and BB and PDGF receptor-B (PDGFR-B) have been detected by immunohistochemistry and Western Blot in the majority of meningiomas of all grades [11–14]. Early studies have also shown that normal arachnoid cells express PDGF receptors, almost exclusively of the β-type [14, 15]. Administration of PDGF-B to meningioma cells in culture stimulates growth and activates mitogen-activated protein kinases and c-fos [16]. However, the exact importance of PDGF-B / PDGFR-B signaling in meningiomas remains elusive, especially in relation with NF2 inactivation.

To specifically overexpress PDGF-B in arachnoidal cells, we used the RCAS/tv-a system in which oncogene carrying RCAS (replication-competent avian sarcoma-leukosis virus long terminal repeat with splice acceptor) retroviruses infect specific somatic cells carrying the tv-a receptor in tv-a transgenic mice [17]. By generating transgenic mice expressing tv-a under the control of tissue specific promoters, exclusive infection by RCAS has been obtained to tv-a-expressing cells, allowing the generation of several mouse glioma models, including PDGF-B-driven tumors [18, 19] and demonstrating that abnormal PDGF signaling can contribute to the etiology of brain tumors. In order to specifically target arachnoid cells, we chose the PGDS promoter to generate a new transgenic PGDStv-a strain. Here we show that PDGF-B overexpression in arachnoid mouse cells induces the development of benign meningiomas synergizing with Nf2 and Cdkn2ab loss for malignant histological progression.

RESULTS

Expression of PDGFR-B is correlated with NF2 status in human meningiomas

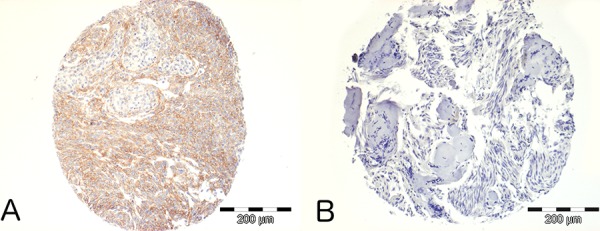

PDGF-B and PDGFR-B are widely expressed in human meningiomas [11]. To assess the relationship between PDGF-B expression and NF2 status, we performed PDGFR-B immunohistochemistry on a Tissue Array of 54 meningiomas of all grades with known NF2 status. We analyzed 36 NF2- meningiomas (defined as presenting either an identified NF2 mutation and 22q LOH, or 22q LOH with no NF2 protein expression on Western blot) and 18 NF2+ meningiomas (defined as presenting NF2 protein expression with no 22q LOH and no NF2 mutation). PDGFR-B immunopositivity was found in 54% of meningiomas and statistically more frequent in NF2- tumors compared to NF2+ tumors (23/36 vs. 6/18, χ2, p = 0,03, Figure 1). No correlation between PDGFR-B immunopositivity and meningioma histological grade was found.

Figure 1. Immunohistochemical analysis of PDGFR-B expression in human meningiomas.

A. Example of a NF2- Grade II meningioma demonstrating strong positivity. B. Example of a NF2+ Grade I meningioma demonstrating no immunopositivity.

Generation and functional testing of the PGDStv-a mouse

To overexpress PDGF-B in arachnoid cells in vivo, we have generated a new transgenic mouse strain where the tv-a receptor is expressed under the control of the endogenous PDGS gene promoter using a knock-in approach [8]. A nuclear-targeted tv-a receptor gene was integrated into the PGDS coding region by replacing exon 1 of the murine PGDS gene (Figure S1, supplementary data).

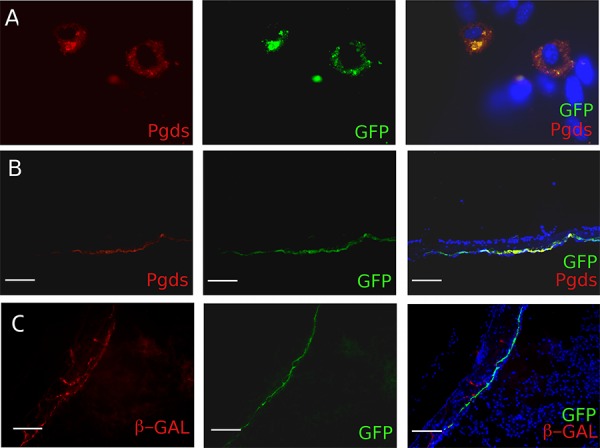

To evaluate the in vitro expression of the transgene, we established primary arachnoid cell cultures from neonatal PGDStv-a brains and infected them with supernatant from DF-1 cells producing RCAS-eGFP (Figure 2A). Approximately 5–10% of the cells were infected and were large in size with oval nuclei, reminiscent of arachnoid cap cells. Infected cells were analyzed with immunocytochemistry and identified by GFP immunopositivity. As expected, GFP-positive cells had a strong PGDS immunopositivity (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. In vitro and in vivo characterization of the PDGDStv-a mouse.

A. Functional analyses of the PGDStv-a transgenic construct in a culture of arachnoidal cells. Infection with RCAS-eGFP was directed to cells with arachnoid morphology and the enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP)-infected cells co-expressed PGDS (red cytoplasmic staining). B. In vivo characterization of PN7 PGDStv-a mouse brains and meninges. Arachnoid PGDS positive cells forming a thin layer were found to be positive for GFP after transfection with RCAS-eGFP. C. Co-localisation of X-gal (red staining) and GFP stainings in PGDS positive arachnoid cells demonstrating the possibility to co-transfect the same cells with both RCAS and Adenovirus vectors.

To confirm that the transgene was functionally expressed in vivo, we injected DF-1 cells producing RCAS-eGFP retrovirus in the sub-dural space of newborn mice at PN1 and analyzed PN5 meninges. The GFP-positive infected arachnoid mouse cells simultaneously expressed PGDS and formed a delicate layer surrounding the brain, thus perfectly adopting the shape of the arachnoid layer (Figure 2B). As we aimed at deleting Nf2 using Cre-loxP system and activating PDGF-B using the RCAS-/tv-a system in the same cell, we injected newborn mice in the sub-dural space with DF-1 cells producing RCAS-eGFP retrovirus to test the RCAS/tv-a recombination and Adenovirus Adβ-Gal to test the Cre-loxP recombination. We then analyzed the arachnoid layer and demonstrated co-infection of meningioma progenitor cells with both RCAS virus and Adenovirus (Figure 2C).

In conclusion, we found that in the PGDStv-a mouse functional tv-a expression is restricted to PGDS positive cells and that both in vitro and in vivo retroviral infections resulted in specific transgene expression, alone or in combination with adenoviral infection.

Effect of overexpression of the PDGF-B oncogene in PGDS-positive arachnoid cells alone or in combination with Nf2 inactivation

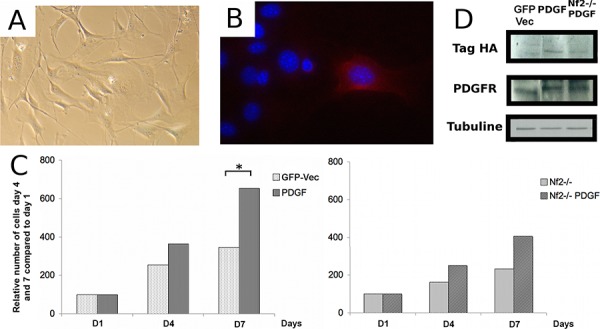

To analyze the effect of overexpression of PDGF-B in vitro, we cultured arachnoid cells taken from the meninges of the skull vault of PGDStv-a;Nf2flox2/flox2 mice. Cells in culture displayed an enlarged and flattened phenotype as previously reported in human meningioma cell cultures [20] (Figure 3A). Next, we co-infected cells with RCAS-PDGF-B and AdCre. Viral infection was verified by HA (Human influenza hemagglutinin)-tag immunostaining of infected cells (Figure 3B). Because of the rapid senescence of arachnoid cells in culture, experiments were performed using cells at early passages. For the analysis, the number of cells at days 4 and 7 after infection was determined and calculated as fold change of cell number compared to day 1 (Figure 3C). Overexpression of PDGF-B significantly increased the proliferation of arachnoid cells compared to the control cells transfected with RCAS-GFP (Student t-test, p < 0.05). Similarly, concomitant overexpression of PDGF-B and Nf2 inactivation increased the proliferation of arachnoid cells compared to cells with Nf2 inactivation alone. In human meningioma primary cultures overexpression of PDGF-B increases the number of PDGF-B receptors (PDGFR-B) by an autocrine loop [16, 21]. Likewise, in our system, overexpression of PDGF-B by RCAS infection increases the expression of PDGFR-B in cultured mouse arachnoid cells (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. Effect of oncogenic stimulation by platelet-derived growth factor B (PDGF-B) on proliferation of arachnoidal cells in culture alone or in combination with Nf2 inactivation.

A. Morphology of arachnoid cells in culture. B. Hemagglutinin A (HA)-immunocytochemistry in arachnoid cells in vitro. C. Effect of PDGF-B overexpression on the growth of arachnoid cells in vitro, alone (left) or in combination with Nf2 bi-allelic inactivation (right) D. Western blot analysis of arachnoid cells demonstrating increased PDGFR immunoreactivity in arachnoidal cells infected with RCAS-PDGF-B compared to controls.

PDGF-B overexpression alone results in meningioma formation while promoting malignant progression in a null Nf2 and Cdkn2ab background

To investigate the potential role of PDGF-B in meningioma initiation, we generated a cohort of 26 PGDStv-a;RCAS-PDGF-B mice and 19 PGDStv-a;RCAS-X control mice, injected with an empty RCAS vector (RCAS-X). After a mean follow-up of 8.0 months, we found 27% of benign meningiomas, mostly located at the convexity, and 33% of meningothelial proliferations in PGDStv-a;RCAS-PDGF-B mice (Table 1). No meningeal lesions were found in the control PGDStv-a;RCAS-X cohort after a mean follow-up of 9.0 months. Interestingly, five PDGF-B-injected mice developed hydrocephalus before 3 months of age associated with meningothelial proliferations and/or meningiomas.

Table 1. Summary of the phenotypic consequences of PDGF-B overexpression in mouse PGDS+ arachnoidal cells in vivo, alone or in combination with Nf2 and Cdkn2ab inactivation.

| PGDStv-a; PDGF-B (n = 26) | PGDStv-a; PDGF-B; AdCre; Nf2flox/flox (n = 29) | Control series AdCre; Nf2flox/flox (n = 25) | PGDStv-a; PDGF-B; AdCre; Nf2flox/flox; Cdkn2ab−/− (n = 19) | Control series AdCre;Nf2flox/flox; Cdkn2ab−/− (n = 53) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean survival (months) | 8.0 | 6.3 | 6.4 | 1.8 | 3.5 |

| Meningiomas | 7 (27%) | 15 (52%) | 4 (16%) | 15 (79%) | 38 (72%) |

| -convexity | 7 | 14 | 0 | 11 | 18 |

| -skull base | 0 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 20 |

| Meningothelial proliferation | 8 (33%) | 11 (38%) | 8 (32%) | 8 (42%) | 5 (9%) |

| Glioma | 23 (88%) | 14 (48%) | 0 | 15 (79%) | 0 |

| Hydrocephalus | 17 (32%) | 2 (7%) | 1 (3%) | 0 | 17 (32%) |

The results of the AdCre; Nf2flox/flox; Cdkn2ab−/− control series were taken from Peyre et al. (9)

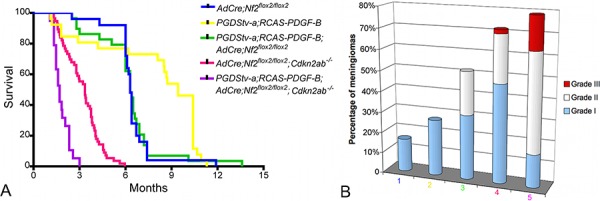

To determine if Nf2 loss alone or in combination with Cdkn2ab loss could promote progression of PDGF-B induced benign meningiomas, we generated cohorts of PGDStv-a;RCAS-PDGF-B;AdCre;Nf2flox2/flox2 and PGDStv-a;RCAS-PDGF-B;AdCre;Nf2flox2/flox2; Cdkn2ab−/− mice. In PGDStv-a;RCAS-PDGF-B;AdCre;Nf2flox2/flox2mice the rate of meningioma development was significantly higher (15 of 29 mice; 52%) compared to AdCre;Nf2flox2/flox2 mice (4 of 25 age-paired mice; 16%; χ2, p = 0,02) (Table 1). In PGDStv-a;RCAS-PDGF-B;AdCre;Nf2flox2/flox2; Cdkn2ab−/− mice, the frequency of meningiomas (15 of 19 mice; 79%) was not statistically different compared to control AdCre;Nf2flox2/flox2; Cdkn2ab−/− mice (38 of 53 mice; 72%). To evaluate the role of PDGF-B activation in meningioma malignant progression, we classified the mouse meningiomas according to the GEM meningioma pathological classification (Figure 4) [9]. We observed 60% (9/15) of grade I and 40% (6/15) grade II meningiomas in PGDStv-a;RCAS-PDGF-B;AdCre;Nf2flox2/flox2 mice (Figure 5A). Of the six grade II meningiomas, four presented at least one mitosis and two showed subpial invasion (Figure 5B). In the group of PGDStv-a;RCAS-PDGF-B;AdCre;Nf2flox2/flox;Cdkn2ab−/− mice, we observed 33% (5/15) of grade I meningiomas, 47% (7/15) of grade II meningiomas and 20% (3/15) of grade III meningiomas. Of the seven grade II meningiomas, one tumor showed subpial invasion and six had at least one mitosis. Among the 3 grade III meningiomas, two presented an architectural dedifferentiation with sarcoma-like appearance and one preserved a meningothelial differentiation but with more than 10 mitosis per field (Figure 5C, 5D). The rate of histologically aggressive meningiomas (grades II and III) was statistically higher in PGDStv-a;RCAS-PDGF-B;AdCre;Nf2flox2/flox2;Cdkn2ab−/− mice compared to AdCre;Nf2flox2/flox2;Cdkn2ab−/− mice (χ2, p = 0,002 and p = 0.03). As for human aggressive meningiomas, brain invasion by direct breaching of pial surface and/or along Virchow-Robin spaces was observed in grades II and III mouse meningiomas

Figure 4. Role of PDGF-B alone or in association with Nf2 loss and Cdkn2ab loss in meningiomagenesis.

A. Survival curves of PGDStv-a;RCAS-PDGF-B mice (n = 26), AdCre;Nf2flox2/flox2 mice (n = 25), PGDStv-a het; RCAS-PDGF-B; AdCre;Nf2flox2/flox2 mice (n = 29), AdCre;Nf2flox2/flox2; Cdkn2ab−/− mice (n = 53) and PGDStv-a;RCAS-PDGF-B;AdCre;Nf2flox2/flox2;Cdkn2ab−/− (n = 19) mice after perinatal injection. B. Proportion of meningioma histological grades in the different mice cohorts : 1. PGDStv-a;RCAS-PDGF-B mice, 2. AdCre;Nf2flox2/flox2 mice, 3. PGDStv-a;RCAS-PDGF-B;AdCre;Nf2flox2/flox2 mice, 4. AdCre;Nf2flox2/flox2;Cdkn2ab−/− mice, 5. PGDStv-a;RCAS-PDGF-B;AdCre;Nf2flox2/flox2;Cdkn2ab−/− mice.

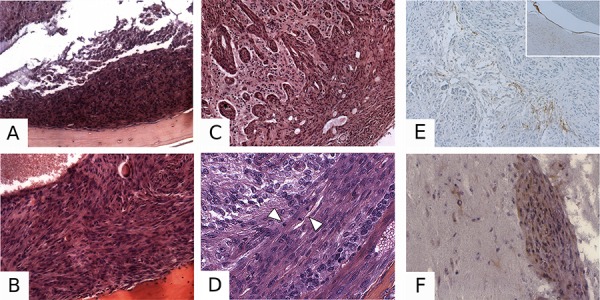

Figure 5. Pathological characterization of PDGF-induced meningiomas.

A. H&E-stained section illustrating a Grade I meningioma in a PGDStv-a;RCAS-PDGF-B mouse. B. Example of a Grade II meningioma in a PGDStv-a;RCAS-PDGF-B;AdCre;Nf2flox2/flox2 mouse. C. Grade III mouse meningioma with brain invasion in a PGDStv-a;RCAS-PDGF-B;AdCre;Nf2flox2/flox2;Cdkn2ab−/− mouse. D. Grade III mouse meningioma with a high mitosis count in a PGDStv-a;RCAS-PDGF-B;AdCre;Nf2flox2/flox2; Cdkn2ab−/− mouse. Arrows indicate two mitoses in a single 63x power field. Example of a Grade III meningioma with focal PGDS positive immunostaining E. with the surrounding arachnoid layer as a positive control (insert). HA immunostaining showing positive F. meningioma cells infiltrating the brain. Some of oligodendroglial cells are also HA-positive.

To demonstrate that meningiomas were induced by RCAS-PDGF-B infection, we performed HA-tag immunohistochemistry in 7 selected meningiomas of all grades. Immunopositivity was found in 50–90% of labeled cells within the tumors (Figure 5F). PGDS immunohistochemistry revealed some cases of strong PGDS immunostaining within specific regions of the tumor (Figure 5E).

In addition to meningiomas, we also found several gliomas in all the PGDStv-a cohorts (Table 1). PGDStv-a;RCAS-PDGF-B mice developed oligodendroglioma while in PGDStv-a; RCAS-PDGF-B;AdCre;Nf2flox2/flox2 mice and PGDStv-a;RCAS-PDGF-B;AdCre; Nf2flox2/flox2;Cdkn2ab−/− mice, all tumors grades were found, from WHO Grade II gliomas to WHO Grade IV glioblastomas. Most tumors resembled oligodendroglioma, but some had mixed oligodendrocytic and astrocytic components as shown by GFAP immunopositivity (data not shown), as previously described in models of PDGF-driven gliomas derived from oligodendroglial progenitors [19]. In conclusion, we demonstrated that in vivo PDGF-B overexpression in mouse arachnoidal cells promotes meningioma initiation and cooperates with Nf2 and Cdkn2ab loss to promote histological meningioma progression.

DISCUSSION

This study explores the role of PDGF-B in meningioma tumorigenesis using an innovative approach combining conditional mutagenesis and the RCAS/tv-a system to recapitulate the genetic alterations found in human meningioma progression. This is the first case of combination of Cre-loxP and RCAS-tv-a systems using two different types of viral vectors (adenovirus and retrovirus). Seidler et al. [22] generated a mouse model for Cre-inducible tv-a expression by insertion of a silenced tv-a/lacZ cassette into the ubiquitously expressed Rosa26 locus. Others [23, 24] combined conditional gene knockout and oncogene overexpression in the same tv-a expressing cell type by simultaneously injecting two RCAS vectors with the Cre recombinase and the oncogene of interest. Use of two RCAS viruses in our model would have hampered a direct comparison with our previous models, due to the change in the method of delivery of the Cre recombinase to arachnoid cells.

We showed that PDGF overexpression alone results in meningioma formation in vivo, the relatively short latency of meningioma development in these mice arguing against the need for additional mutations. A link between PDGFR expression and NF2 loss has been demonstrated in human schwannoma [25]. Merlin-deficient schwannoma cells show accumulation of growth factors receptors at the plasma membrane, including PDGFR-B [26], with high levels of receptors associated with an increase of phosphorylated receptors. These molecular phenotypes were correlated with the expression of merlin: its reintroduction into Nf2−/− Schwann cells markedly reduced the levels of PDGFR-B. Moreover, in a schwannoma cell line, merlin was also shown to decrease membrane levels of PDGFR-B by inducing its degradation [27]. A statistically higher expression of PDGFR-A has been found in meningiomas with monosomy 22 compared to meningiomas with normal karyotype, while PDGFR-B was ubiquitously expressed in all tumors [28]. Here we observed a correlation between PDGFR-B expression and NF2 loss in human meningiomas and their synergy in mouse meningiomagenesis.

Based on the evidence of PDGF-B and PDGFR-B expression in meningiomas, several pre-clinical and clinical trials have been performed using PDGFR. Meningioma cell lines demonstrated the efficacy of Sunitinib inhibiting cell proliferation and migration in vitro and that PDGFR was the prime target of the drug. Sunitinib reduced PDGFR-autophosphorylation even at the lowest concentration tested [29]. After disappointing results of a phase II trial of imatinib mesylate, a recent single arm phase II study on another Receptor Tyrosine Kinase (RTK) inhibitor targeting PDGFR and VEGFR, sunitinib malate, demonstrated partial activity in recurrent and progressive Grade II and III meningiomas, encouraging additional trials [30].

We found no difference in meningioma histological subtypes in PDGF-induced tumors compared to previous models, with a predominance of meningothelial, fibroblastic and transitional types [7, 9]. On the other hand, PDGF-induced tumors were mostly found at the convexity while meningiomas in the other mouse models were mostly found at the skull base [7, 9]. Interestingly, PDGF-B overexpression in PGDStv-a expressing cells also induced gliomas of various histological grades. This is likely due to PGDS expression in oligodendrocytes after commencement of myelination in rats [31–33], mice [34] and humans [8, 35] making it a marker of mature oligodendrocytes [36]. In this model, gliomas were more frequent than meningiomas in PGDStv-a;RCAS-PDGF-B mice. In other PDGF-driven glioma mouse models, the incidence of tumors was 33% at 3 months when targeting oligodendroglial progenitors using the CNP promoter (Ctv-a mouse, [19]), 50% at 3 months when targeting neural/glial stem cells with Nestin promoter (Ntv-a mouse, [37]) and 16% at 3 months when targeting astrocytes using GFAP promoter (Gtv-a mouse, [37]). The high incidence of gliomas in our model at 8 months suggests that other cell types in the CNS and/or developmental stages are sensitive to PDGF-B transformation and may serve as cell of origin for glioma.

Finally, we have confirmed the key role of Cdkn2ab loss in meningioma malignant transformation. While PDGF-B overexpression in addition to Nf2 loss resulted in higher tumor frequency and grade II meningiomas, additional loss of Cdkn2ab also induced malignant grade III meningiomas.

In conclusion, we showed the pivotal role of PDGF-B in meningioma initiation and progression thus confirming it as a target for future clinical trials with selective inhibitors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Immunohistochemical characterization of PDGFR-B in human NF2- and NF2+ meningiomas

A Tissue Micro Array was built using meningiomas of all grades operated in the Neurosurgery department of Beaujon Hospital, Clichy, France. The local institutional review board approved this retrospective analysis. All patients or their parents provided informed consent. Sonic aspirator extracts were excluded from the study. Meningiomas were graded based on WHO 2000 criteria. Immunostainings for PDGFR-B (1:1, clone E29, DAKO) was performed for all cases. NF2 gene characterization was performed as previously published [38], with additional NF2 protein Western Blot. Tumor material and NF2 status were available for 54 patients. There were 25 WHO Grade I, 26 WHO Grade II and 3 WHO Grade III meningiomas.

Generation and genotyping of PGDStv-a transgenic mice

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the local animal ethics committee.

Germline chimeras (PGDStv-afloxGFPHygro/+) were generated by injection of 10 mutant embryonic stem cells into C57BL/6 blastocysts, and crossed with FVB/N mice to produce outbred heterozygous offspring. The genotypes of all offspring were analyzed by polymerase chain reaction or Southern blot analysis on tail-tip DNA. To generate PGDStv-a mice, PGDStv-afloxGFPHygro/+ mice were crossed with EIIACre deletor transgenic mice [39]. In the deriving double transgenic offspring XbaI–NdeI digested tail DNA, deletion of the floxed GFP-Hygromicin cassette was confirmed by PCR. Mice carrying the PGDStv-a allele were subsequently crossed with FVB/N mice to segregate the mutant allele. Genotyping was carried out on DNA purified from tail biopsies after PCR reactions were performed using primers specific for PGDStv-a (sequence available upon request).

In vitro infection and immunohistochemical staining of primary arachnoid cultures

Primary arachnoid cell cultures were established from adult PGDStv-a−/+ mice. The arachnoid tissue was surgically removed at the ventral surface of the brainstem after sacrifice and plated in Petri dishes after 1 h digestion by Collagenase. Arachnoid cells were then cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing 10% Fetal Calf Serum (FCS), Insulin and Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF). Cells were infected for 5 days for characterization and seeded on coverslips for immunohistochemistry. Infected cells were fixed in 4% PFA for 15 min and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X. They were then incubated with primary and secondary antibodies. Cells were mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) containing DAPI. Stainings were visualized using a Zeiss (Oberkochen, Germany) microscope.

Immunostaining of postnatal brain sections

After injection of newborn mice with DF-1 cells producing RCAS-eGFP retrovirus at PN1 and Adenovirus Adβ-Gal at PN3, pups were sacrificed and injected P7 heads injected at were fixed in 4% Formol at 4°C overnight and cryosectioned. Sections were incubated with primary antibody Pgds (1/1000; Santa Cruz, sc-14825), GFP (1/200; Abcam, catalog#ab290), diluted in blocking solution followed by secondary antibody. Slides were mounted Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) containing DAPI. Stainings were visualized using a Zeiss (Oberkochen, Germany) microscope.

In vivo tumor induction

For Nf2 and Cdkn2ab inactivation, we used Nf2flox2/flox2 and p16Ink4a−/−;p15Ink4b−/−;p19Arf flox/flox (noted Cdkn2ab−/− in this paper) mouse strains [9]. Neonatal mice were injected subdurally as previously described [7] with 3 to 4 μl of Adenovirus (Ad5CMV-Cre-AdCre or Adβ-Gal) (University of Iowa Gene Transfer Vector Core, Iowa City, IA, USA) at PN1 and then injected at PN3 with 4 μl of RCAS-producing DF-1 chicken fibroblasts (RCAS-PDGF-B, RCAS-GFP), which equals approximately 2.105 cells, as previously described [19]. RCAS-PDGF-B-HA contains a 3-nt ‘ACC’ Kozak consensus sequence in front of PDGF-B and a C-terminal HA epitope tag [40]. DF-1 cells were cultured in DMEM with addition of 10% FCS (Gibco), 4 mM L-glutamine (Gibco) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco). Mice were monitored every day and euthanized on any sign of illness or at predefined time points according to the control cohorts. Brains were then fixed, decalcified and embedded in paraffin as previously described [41].

Immunohistochemical analysis of tumors

Immunohistochemical staining was performed on 6-mm paraffin sections. For antigen retrieval, after pressure boiling in antigen unmasking solution (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA, USA) or 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) for 45 minutes, sections were incubated in 1% H2O2 in methanol for 30 min and blocked in 1.5% Normal Goat Serum followed by incubation with primary antibody. Biotinylated secondary goat anti-mouse, goat anti-rabbit, rabbit anti-goat or rabbit anti-rat antibodies were used at 1:200. Stainings were developed using Vectastain ABC system and DAB substrate kit (Vector Labs). For HA secondary antibody Alexa Flour 555 donkey anti-rabbit was used at 1:400 dilution and mounted in Immu-Mount (Shandon) containing DAPI.

Proliferation assay

After 10 days of primary culture, mouse arachnoid cells were passaged in 6-well plates at a concentration of 1000 cells / mL. After 72 hours, cells were infected with AdCre at a concentration of 50 pfu per cell for 48 hours. Next, cells were infected with RCAS-PDGF-B and RCAS-GFP (GFP-vec) as described [19]. Infection was repeated daily for 5 consecutive days. Cells were then seeded at a concentration of 2.104 cells/mL in triplicate, and counted 1, 4 and 7 days after plating, manually using blade KOVA (Hycor, IN, USA) and/or automatically using Cellometer (Nexcelomn Nexcelom Bioscience, MA, USA).

Western blot

Cells were washed twice in ice-cold PBS, scraped in PBS and lysed in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% P40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, prepared from a 10X solution (RIPA Lysis Buffer, Millipore) to which was added a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Complete™ Protease inhibitor cocktail, Roche). The samples were incubated for 45 min on ice, then centrifuged for 20 min at 16,000 g at 4°C. The resulting supernatant was removed and the protein concentration of each extract was determined using a DC Protein Assay (Biorad, CA, USA). The proteins were separated by migration in a gel concentration and migration SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Immobilon-P Transfer, Millipore) at 4°C for 2 hours at 100 V, blocked using a solution of BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin from 96%, Sigma Aldrich) diluted to 5% in Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 0.1 M NaCl, 0.1% Tween (TBS-T), washed with TBS-Tween 0.1% and immunoblotted with the primary antibody monoclonal anti-PDGFR B (Cell Signaling, catalog#3169, clone#28E1) rabbit diluted by 1/1000 and the rabbit anti with Tag-HA (Santa Cruz, catalog#sc805, clone#Y-11) diluted by 1/1000. The secondary antibody used was anti-rabbit polyclonal IgG HRP (Santa Cruz, catalog#sc2004) diluted by 1/10000.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr N. Lindberg and Dr L. Uhrbom (Uppsala, Sweden) for their invaluable support and for the RCAS-PDGF vector; Dr. E. Holland for the SPKE 0.8 TV-A vector, Dr. M. Pla and staff of the Institut Universitaire d'Hematologie (IUH), Universite Paris 7, for mouse housing; A. Roumegous and N. Karboul for technical assistance. Special thanks to Dr. D. Gutmann for his contribution to the initial stages of this project.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have reported no conflicts of interest.

GRANT SUPPORT

This work was supported in part by the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command under grant DAMD17-02-1-0645 to MG, Association Neurofibromatoses et Recklinghausen (EC-T, AR, NK), DFG (MA 2530/6-1) and the Wilhelm Sander Stiftung (2014.092.1) (CM).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Farah P, Ondracek A, Chen Y, Wolinsky Y, Stroup NE, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS. CBTRUS statistical report: Primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2006–2010. Neuro Oncol. 15:ii1–ii56. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aghi MK, Carter BS, Cosgrove GR, Ojemann RG, Amin-Hanjani S, Martuza RL, Curry WT, JR, Barker FG., 2nd Long-term recurrence rates of atypical meningiomas after gross total resection with or without postoperative adjuvant radiation. Neurosurgery. 2009;64:56–60. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000330399.55586.63. discussion 60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sughrue ME, Sanai N, Shangari G, Parsa AT, Berger MS, McDermott MW. Outcome and survival following primary and repeat surgery for World Health Organization Grade III meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2010;113:202–209. doi: 10.3171/2010.1.JNS091114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanft S, Canoll P, Bruce JN. A review of malignant meningiomas: diagnosis, characteristics, and treatment. J Neurooncol. 2010;99:433–443. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brastianos PK, Horowitz PM, Santagata S, Jones RT, McKenna A, Getz G, Ligon KL, Palescandolo E, Van Hummelen P, Ducar MD, Raza A, Sunkavalli A, Macconaill LE, et al. Genomic sequencing of meningiomas identifies oncogenic SMO and AKT1 mutations. Nat Genet. 2013;45:285–289. doi: 10.1038/ng.2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark VE, Erson-Omay EZ, Serin A, Yin J, Cotney J, Ozduman K, Avsar T, Li J, Murray PB, Henegariu O, Yilmaz S, Gunel JM, Carrion-Grant G, et al. Genomic analysis of non-NF2 meningiomas reveals mutations in TRAF7, KLF4, AKT1, and SMO. Science. 2013;339:1077–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1233009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalamarides M, Niwa-Kawakita M, Leblois H, Abramowski V, Perricaudet M, Janin A, Thomas G, Gutmann DH, Giovannini M. Nf2 gene inactivation in arachnoidal cells is rate-limiting for meningioma development in the mouse. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1060–1065. doi: 10.1101/gad.226302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalamarides M, Stemmer-Rachamimov AO, Niwa-Kawakita M, Chareyre F, Taranchon E, Han ZY, Martinelli C, Lusis EA, Hegedus B, Gutmann DH, Giovannini M. Identification of a progenitor cell of origin capable of generating diverse meningioma histological subtypes. Oncogene. 2011;30:2333–2344. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peyre M, Stemmer-Rachamimov A, Clermont-Taranchon E, Quentin S, El-Taraya N, Walczak C, Volk A, Niwa-Kawakita M, Karboul N, Giovannini M, Kalamarides M. Meningioma progression in mice triggered by Nf2 and Cdkn2ab inactivation. Oncogene. 32:4264–4272. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hallahan AR, Pritchard JI, Hansen S, Benson M, Stoeck J, Hatton BA, Russell TL, Ellenbogen RG, Bernstein ID, Beachy PA, Olson JM. The SmoA1 mouse model reveals that notch signaling is critical for the growth and survival of sonic hedgehog-induced medulloblastomas. Cancer Research. 2004;64:7794–7800. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Black PM, Carroll R, Glowacka D, Riley K, Dashner K. Platelet-derived growth factor expression and stimulation in human meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 1994;81:388–393. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.81.3.0388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maxwell M, Galanopoulos T, Hedley-Whyte ET, Black PM, Antoniades HN. Human meningiomas co-express platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and PDGF-receptor genes and their protein products. Int. J. Cancer. 1990;46:16–21. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910460106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adams EF, Todo T, Schrell UM, Thierauf P, White MC, Fahlbusch R. Autocrine control of human meningioma proliferation: secretion of platelet-derived growth-factor-like molecules. Int. J. Cancer. 1991;49:398–402. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910490315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang JL, Nistér M, Hermansson M, Westermark B, Pontén J. Expression of PDGF beta-receptors in human meningioma cells. Int. J. Cancer. 1990;46:772–778. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910460504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perry A, Lusis EA, Gutmann DH. Meningothelial hyperplasia: a detailed clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical and genetic study of 11 cases. Brain Pathology. 2005;15:109–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2005.tb00505.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Todo T, Adams EF, Fahlbusch R, Dingermann T, Werner H. Autocrine growth stimulation of human meningioma cells by platelet-derived growth factor. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:852–858. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.84.5.0852. discussion 858–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uhrbom L, Holland EC. Modeling gliomagenesis with somatic cell gene transfer using retroviral vectors. J. Neurooncol. 2001;53:297–305. doi: 10.1023/a:1012208314436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dai C, Celestino JC, Okada Y, Louis DN, Fuller GN, Holland EC. PDGF autocrine stimulation dedifferentiates cultured astrocytes and induces oligodendrogliomas and oligoastrocytomas from neural progenitors and astrocytes in vivo. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1913–1925. doi: 10.1101/gad.903001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindberg N, Kastemar M, Olofsson T, Smits A, Uhrbom L. Oligodendrocyte progenitor cells can act as cell of origin for experimental glioma. Oncogene. 2009;28:2266–2275. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.James MF, Lelke JM, Maccollin M, Plotkin SR, Stemmer-Rachamimov AO, Ramesh V, Gusella JF. Modeling NF2 with human arachnoidal and meningioma cell culture systems: NF2 silencing reflects the benign character of tumor growth. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;29:278–292. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shamah SM, Alberta JA, Giannobile WV, Guha A, Kwon YK, Carroll RS, Black PM, Stiles CD. Detection of activated platelet-derived growth factor receptors in human meningioma. Cancer Research. 1997;57:4141–4147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seidler B, Schmidt A, Mayr U, Nakhai H, Schmid RM, Schneider G, Saur D. A Cre-loxP-based mouse model for conditional somatic gene expression and knockdown in vivo by using avian retroviral vectors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:10137–10142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800487105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robinson JP, VanBrocklin MW, Guilbeault AR, Signorelli DL, Brandner S, Holmen SL. Activated BRAF induces gliomas in mice when combined with Ink4a/Arf loss or Akt activation. Oncogene. 2010;29:335–344. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pitter KL, Galbán CJ, Galbán S, Tehrani OS, Saeed-Tehrani O, Li F, Charles N, Bradbury MS, Becher OJ, Chenevert TL, Rehemtulla A, Ross BD, Holland EC, et al. Perifosine and CCI 779 co-operate to induce cell death and decrease proliferation in PTEN-intact and PTEN-deficient PDGF-driven murine glioblastoma. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e14545. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou L, Ercolano E, Ammoun S, Schmid MC, Barczyk MA, Hanemann CO. Merlin-deficient human tumors show loss of contact inhibition and activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling linked to the PDGFR/Src and Rac/PAK pathways. Neoplasia. 2011;13:1101–1112. doi: 10.1593/neo.111060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lallemand D, Manent J, Couvelard A, Watilliaux A, Siena M, Chareyre F, Lampin A, Niwa-Kawakita M, Kalamarides M, Giovannini M. Merlin regulates transmembrane receptor accumulation and signaling at the plasma membrane in primary mouse Schwann cells and in human schwannomas. Oncogene. 2009;28:854–865. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fraenzer JT, Pan H, Minimo L, Jr, Smith GM, Knauer D, Hung G. Overexpression of the NF2 gene inhibits schwannoma cell proliferation through promoting PDGFR degradation. Int J Oncol. 2003;23:1493–1500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Figarella-Branger D, Vagner-Capodano AM, Bouillot P, Graziani N, Gambarelli D, Devictor B, Zattara-Cannoni H, Bianco N, Grisoli F, Pellissier JF. Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and receptor (PDGFR) expression in human meningiomas: correlations with clinicopathological features and cytogenetic analysis. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1994;20:439–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1994.tb00994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andrae N, Kirches E, Hartig R, Haase D, Keilhoff G, Kalinski T, Mawrin C. Sunitinib targets PDGF-receptor and Flt3 and reduces survival and migration of human meningioma cells. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:1831–1841. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaley TJ, Wen P, Schiff D, Ligon K, Haidar S, Karimi S, Lassman AB, Nolan CP, DeAngelis LM, Gavrilovic I, Norden A, Drappatz J, Lee EQ, et al. Phase II trial of sunitinib for recurrent and progressive atypical and anaplastic meningioma. Neuro Oncology. 2015;17:116–21. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Urade Y, Fujimoto N, Kaneko T, Konishi A, Mizuno N, Hayaishi O. Postnatal changes in the localization of prostaglandin D synthetase from neurons to oligodendrocytes in the rat brain. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:15132–15136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.García-Fernández LF, Urade Y, Hayaishi O, Bernal J, Muñoz A. Identification of a thyroid hormone response element in the promoter region of the rat lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase (beta-trace) gene. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1998;55:321–330. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beuckmann CT, Urade Y, Hayaishi O. Lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase (beta-trace) binds non-substrate lipophilic ligands. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;469:55–60. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4793-8_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eguchi N, Minami T, Shirafuji N, Kanaoka Y, Tanaka T, Nagata A, Yoshida N, Urade Y, Ito S, Hayaishi O. Lack of tactile pain (allodynia) in lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:726–730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blödorn B, Mäder M, Urade Y, Hayaishi O, Felgenhauer K, Brück W. Choroid plexus: the major site of mRNA expression for the beta-trace protein (prostaglandin D synthase) in human brain. Neurosci. Lett. 1996;209:117–120. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12614-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Urade Y, Fujimoto N, Hayaishi O. Purification and characterization of rat brain prostaglandin D synthetase. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:12410–12415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tchougounova E, Kastemar M, Brasater D, Holland EC, Westermark B, Uhrbom L. Loss of Arf causes tumor progression of PDGFB-induced oligodendroglioma. Oncogene. 2007;26:6289–6296. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goutagny S, Yang HW, Zucman-Rossi J, Chan J, Dreyfuss JM, Park PJ, Black PM, Giovannini M, Carroll RS, Kalamarides M. Genomic profiling reveals alternative genetic pathways of meningioma malignant progression dependent on the underlying NF2 status. Clin Cancer Research. 2010;16:4155–4164. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lakso M, Pichel JG, Gorman JR, Sauer B, Okamoto Y, Lee E, Alt FW, Westphal H. Efficient in vivo manipulation of mouse genomic sequences at the zygote stage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:5860–5865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shih AH, Dai C, Hu X, Rosenblum MK, Koutcher JA, Holland EC. Dose-dependent effects of platelet-derived growth factor-B on glial tumorigenesis. Cancer Research. 2004;64:4783–4789. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giovannini M, Robanus-Maandag E, van der Valk M, Niwa-Kawakita M, Abramowski V, Goutebroze L, Woodruff JM, Berns A, Thomas G. Conditional biallelic Nf2 mutation in the mouse promotes manifestations of human neurofibromatosis type 2. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1617–1630. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.