Abstract

Objective: To provide an overview of the prevalence of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) and their risk factors in several Pacific island countries and territories (PICTs), in accordance with global NCD targets.

Methods: For six risk factors, data for adults (aged 25–64 years) from published reports of the World Health Organization STEPwise approach to NCD surveillance, or methodologically similar surveys, were collated, age standardised and compared across fifteen PICTs.

Results: In the majority of PICT populations, more than half of male current drinkers drank heavily and more than 40% of men and 20% of women were current smokers. In 10 populations, about 50% or more of women were insufficiently physically active. Prevalence of hypertension and diabetes exceeded 20% and 25%, respectively, in several populations. Near or more than half of men and women in all populations were overweight; in most, more than one‐third of both sexes were obese.

Conclusions: The prevalence of NCDs and risk factors varies widely between PICTs and by sex. The evidence shows the high and alarming present and future burden of NCDs in the region.

Implications: Strengthened political commitment and increased investment are urgently required to tackle the NCD crisis, successfully achieve targets and ensure continuing sustainable development in the Pacific islands.

Keywords: noncommunicable diseases, Pacific Islands, adults, prevalence, epidemiology

The Pacific islands have a strong history of collaboration for development, including public health, through membership of the Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC), founded in 1947. 1 Today, these 22 Pacific island countries and territories (PICTs) (referred to hereafter as ‘the Pacific region’) are facing a “human, social, and economic crisis” due to noncommunicable diseases (NCDs). 2 Cardiovascular disease and diabetes are among the leading causes of mortality in the region; mental health disorders, musculoskeletal conditions, diabetes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are estimated to account for much of the non‐fatal burden of disease. 3 Through the costs of treatment, combined with the social and economic consequences of premature mortality, morbidity and lost productivity, NCDs pose a grave threat to development in the region. 4

Global voluntary targets for NCDs have been established. 5 Monitoring the region's progress towards these targets will need robust surveillance and knowledge of the current burden of NCDs and their shared risk factors. Although a wealth of data are gathered in the Pacific, considerably more analysis and dissemination is required. 3 Considering the shared challenges the islands face, collation of data in a Pacific‐focused analysis is warranted.

This paper builds on previous work by SPC, 6 presenting data for adults in the Pacific region on indicators corresponding to five of the nine global NCD targets: at least a 10% relative reduction in the harmful use of alcohol; a 10% relative reduction in the prevalence of insufficient physical activity; a 30% relative reduction in current tobacco use prevalence; a 25% relative reduction in the prevalence of raised blood pressure; and a halt in the rise in diabetes and obesity. These targets support the overarching goal of reducing premature mortality from NCDs by 25% by 2025. 5 By providing a regional overview of NCD risk factors in the Pacific, this work will assist in monitoring progress towards the targets and in the development of evidence‐based national and regional policies to tackle the NCD crisis.

Methods

Data on NCDs and their risk factors in adults in the Pacific are available from several different surveys. These include the World Health Organization (WHO) STEPwise approach to surveillance (STEPS) 7 and, for the United States affiliated Pacific Islands, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). 8 STEPS was selected as the primary data source for the present analysis as it is widely utilised and provides a standardised methodology for our comparisons.

STEPS methodology has been published in depth elsewhere. 9 Briefly, the approach utilises a multi‐stage cluster design with probability proportional to size sampling. Data are collected in person through interviewer‐administered questionnaires (STEP 1), physical measurements (STEP 2) and biochemical analyses of blood samples (STEP 3). Each step has core, expanded and optional modules, use of which is informed by available resources and national data needs. Sample, non‐response and population weights are applied to results as needed.

SPC holds a database with the results from reports published by PICTs of STEPS and similar surveys. We analysed data from fifteen PICTs (Table 1). 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 We included the survey for Wallis and Futuna, which was based on STEPS methodology, and the Baromètre Santé in New Caledonia which, like STEPS, utilised a multi‐stage sampling design and in‐person interviews.

Table 1.

Published reports of surveys utilised in this analysis, with year conducted.

| Country Survey Report | Year |

|---|---|

| American Samoa NCD Risk Factors STEPS Report | 2004 |

| Cook Islands NCD Risk Factors STEPS Report | 2003–2004 |

| Fiji Non‐communicable diseases (NCD) STEPS Survey 2002 | 2002 |

| Enquête Santé 2010 en Polynésie française (French Polynesia) | 2010 |

| Kiribati NCD Risk Factors STEPS Report | 2004–2006 |

| Republic of the Marshall Islands NCD Risk Factors STEPS Report 2002 | 2002 |

| Federated States of Micronesia (Chuuk) NCD Risk Factors STEPS Report Federated States of Micronesia (Pohnpei) NCD Risk Factors STEPS Report |

2006 2002 |

| Nauru NCD Risk Factors STEPS Report | 2004 |

| Niue NCD Risk Factors STEPS Report | 2011–2012 |

| Baromètre Santé Nouvelle‐Calédonie 2010, Résultats préliminaires (New Caledonia)a | 2010 |

| Solomon Islands NCD Risk Factors STEPS Report | 2005–2006 |

| Tokelau NCD Risk Factors STEPS Report | 2005 |

| Kingdom of Tonga NCD Risk Factors STEPS Report | 2004 |

| Vanuatu NCD Risk Factors STEPS Report | 2011 |

| Study of Risk Factors for Chronic Non‐communicable Diseases in Wallis and Futunab | 2009 |

a: The survey for New Caledonia utilised a comparable methodology to STEPS.

b: The survey for Wallis and Futuna was based on STEPS methodology.

Local adaptation of STEPS can result in methodological variations between PICTs. For example, Niue and Tokelau designed the survey to include all members of the target population. Details of the surveys' methods can be found in individual country reports.

We examined the survey reports for results aligning to the global targets and their primary indicator for adults, as per the Global Action Plan for Noncommunicable Diseases. 5 We identified relevant and comparable data for the main indicator to five of the nine targets and selected: i) the percentage of current (past 12 months) drinkers who reported consuming six or more drinks on average on a day in which alcohol was consumed (‘heavy drinking’); ii) the proportion of the population who obtained <600 MET minutes of total physical activity per week (‘insufficient physical activity’); iii) the percentage of the population who were current (past 12 months) tobacco smokers; iv) the proportion of the population with hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg, or on anti‐hypertensive medication); v) the percentage of the population with diabetes (raised fasting blood glucose or on medication for raised blood glucose); and vi) the percentage of the population with a Body Mass Index (BMI) ≥25 kg/m2 (overweight), and ≥30 kg/m2 (obese) (Table 2). We noted where variations to the definitions for current smoking, physical activity and diabetes occurred.

Table 2.

Selected STEPS indicators aligned to the corresponding global indicator and target for noncommunicable disease risk factors in adults.

| STEPS indicator (25–64 years) | Global Indicator | Global Target |

|---|---|---|

| % of current (past 12 months) drinkers who report consuming 6 or more drinks on average during a day on which alcohol is consumed | Age‐standardized prevalence of heavy episodic drinking among adolescents and adults, as appropriate, within the national context | At least a 10% relative reduction in the harmful use of alcohol, as appropriate, within the national context |

| % of population who engage in <600 MET minutes of total physical activity per week | Age‐standardized prevalence of insufficiently physically active persons aged 18+ years (defined as less than 150 minutes of moderate‐intensity activity per week, or equivalent) | A 10% relative reduction in prevalence of insufficient physical activity |

| % of population who are current smokers (smoked tobacco in the past 12 months, either daily or non‐daily) | Age‐standardised prevalence of current tobacco use among persons aged 18+ years | A 30% relative reduction in prevalence of current tobacco use in persons aged 15+ years |

| % of population with raised blood pressure (systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg) or on anti‐hypertensive medication | Age‐standardized prevalence of raised blood pressure among persons aged 18+ years (defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg) and mean systolic blood pressure | A 25% relative reduction in the prevalence of raised blood pressure or contain the prevalence of raised blood pressure, according to national circumstances |

| % of population with raised blood glucose or on medication for raised blood glucose | Age‐standardised prevalence of raised blood glucose/diabetes among persons aged 18+ years (defined as fasting plasma glucose concentration ≥7.0mmol/l (126mg/dl) or on medication for raised blood glucose | Halt the rise in diabetes and obesity |

| % of population with BMI ≥25kg/m2 and % of population with BMI ≥30kg/m2 | Age‐standardized prevalence of overweight and obesity in persons aged 18+ years (defined as body mass index ≥25kg/m2 for overweight and body mass index ≥30kg/m2 for obesity) |

Source: WHO Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020. 5

Although the age range of surveyed populations varied, all surveys included those aged 25 to 64 years. This was therefore the population of focus for this work. STEPS reports aggregated data into 10‐year or, for French Polynesia, 20‐year age brackets. Accordingly, we applied these results to the WHO world population to produce an age‐standardised rate for those aged 25 to 64 years. 26 Prior to standardisation, we developed and compared two standard populations for the Pacific with the WHO world population. As there was minimal difference for the 25–64 year age range, the WHO population was used. Standard errors and confidence intervals for the age‐standardised estimates of prevalence were calculated using the approach described by Breslow and Day. 27

Results

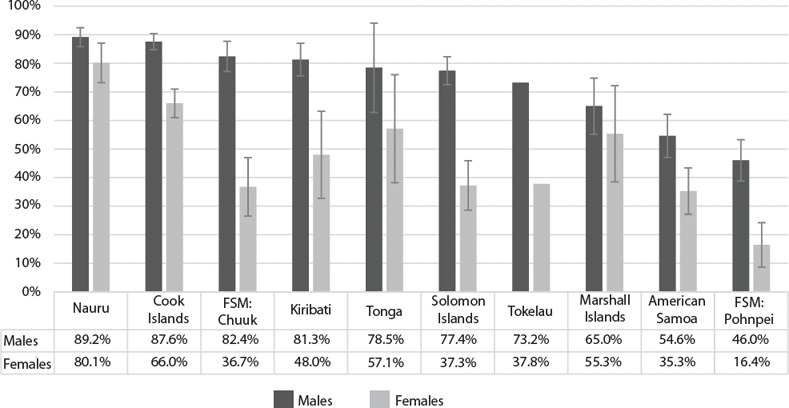

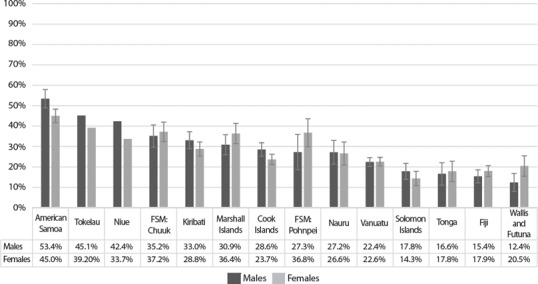

Harmful use of alcohol

In PICT populations for which data were available, among men, nearly half or more of current drinkers reported consuming six or more standard drinks on average on a day when alcohol was consumed (Figure 1). The prevalence of heavy drinking varied more widely among women in PICTs and was highest for both sexes in Nauru and the Cook Islands. Across all populations, the point prevalence of heavy drinking was higher among men than women, though the magnitude of this gender disparity varied.

Figure 1.

Age‐standardised prevalence (with 95% confidence intervals) of heavy drinking* among current (past 12 months) alcohol drinkers, aged 25 to 64 years, by sex and Pacific Island Country and Territory.

Source: STEPS and similar surveys conducted between 2002 and 2006.

FSM: Federated States of Micronesia

Heavy drinking was defined as consuming six or more standard drinks on average on a day when alcohol was consumed. Current drinkers were those who consumed alcohol within the past 12 months.

Small numbers of current drinkers, especially among women, in some PICTs resulted in high estimates of uncertainty. Results must be interpreted with caution.

Confidence intervals were not applicable to Tokelau results as the survey was designed to include all members of the target adult population.

Comparable data not were available from the STEPS and similar survey reports for Fiji, French Polynesia, New Caledonia, Niue, Vanuatu and Wallis and Futuna.

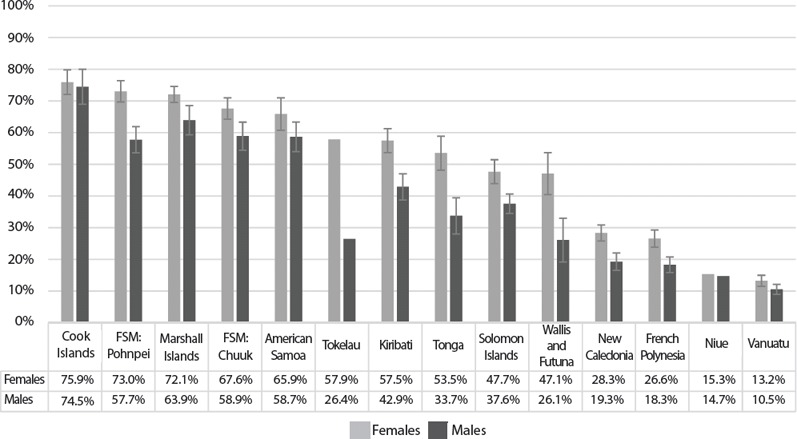

Insufficient physical activity

The prevalence of insufficient physical activity was higher in women than men in PICTs (Figure 2). In 10 populations, about 50% or more of women obtained less than 600MET minutes of physical activity per week; in comparison, this was the case for men in five PICTs. For both sexes, the proportion of the population who were insufficiently active varied considerably across the Pacific; prevalence was highest in the Cook Islands (more than 70% of men and women) and lowest in Vanuatu (less than 15% of men and women).

Figure 2.

Age‐standardised prevalence (with 95% confidence intervals) of insufficient physical activity* among those 25 to 64 years, by sex and Pacific Island Country and Territory.

Source: STEPS and similar surveys conducted between 2002 and 2011.

FSM: Federated States of Micronesia

*Insufficient (or low) physical activity is <600 metabolic equivalent minutes per week. Physical activity is measured in STEPS according to the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire, in which a Metabolic Equivalent (MET) is the ratio of a person's working metabolic rate relative to the resting metabolic rate. One MET is the energy cost of sitting quietly, and equates to a caloric consumption of 1 kcal/kg/hour. Moderate activities are assigned 4.0 METs, vigorous activities are assigned 8.0 METS. MET minutes per week are calculated from the total physical activity across the domains of work, leisure, and transport related walking/cycling which is assigned 4.0 METS. Source: Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) Analysis Guide. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

In the American Samoa STEPS analysis, transport related activity was assigned 3.0METs. In the Wallis and Futuna report, moderate work and leisure activity were assigned 3.0–6.0METs, vigorous activity was assigned 6.0METs. In the Republic of the Marshall Islands report 15 low physical activity was recorded if the criteria for moderate activity were not met – one of the definitions of moderate activity was the sum total of days spent in moderate or vigorous intensity physical activity across the three domains ≥ 5 days AND total physical activity MET minutes per week ≥600.

Confidence intervals were not applicable to Tokelau and Niue results as the surveys were designed to include all members of the target adult population.

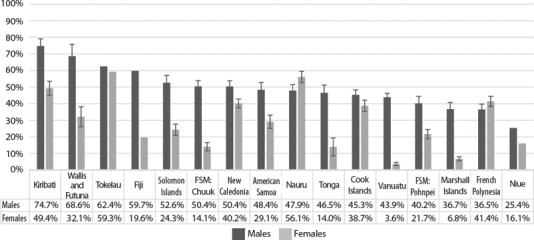

Tobacco smoking

More than one‐quarter of men in Niue smoked, and almost three‐quarters in Kiribati (Figure 3). Overall, a higher percentage of men than women were current smokers; however, in the majority of PICT populations, at least 20% of women smoked. The gender difference was reversed in French Polynesia and Nauru where there was a higher point prevalence of smoking among women.

Figure 3.

Age‐standardised prevalence (with 95% confidence intervals) of current smokers* among those aged 25–64 years, by sex and Pacific Island Country and Territory.

Source: STEPS and similar surveys conducted between 2002 and 2011.

FSM: Federated States of Micronesia

*Current smoking was defined as smoking of tobacco (daily or non‐daily) in the past 12 months, apart from in the French Polynesia, Nauru and New Caledonia reports in which the time frame was not specified.

The prevalence of current smoking in Fiji was estimated from the addition of the prevalence of daily and non‐daily current (past 12 months) smokers as provided in the report. The corresponding 95% confidence intervals were not able to be calculated.

Due to a misprint in the reported age‐specific rates of current smoking in women in the Tokelau report, we recalculated these using the case numbers provided and the age‐specific sample numbers listed elsewhere in the report and verified by WHO.

Confidence intervals were not applicable to Tokelau and Niue results as the surveys were designed to include all members of the target population.

Hypertension

At least 13% of men and women in all populations presented had hypertension (Figure 4). In the majority of populations, prevalence exceeded 20%. Hypertension was least common in the Solomon Islands and most prevalent in American Samoa and the Cook Islands, where more than 30% of women and 40% of men had hypertension. Gender differences varied between countries, though men appeared to be more affected.

Figure 4.

Age‐standardised prevalence (with 95% confidence intervals) of hypertension* among those 25 to 64 years, by sex and Pacific Island Country and Territory.

Source: STEPS and similar surveys conducted between 2002 and 2011.

FSM: Federated States of Micronesia

*Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90mmHg or on medication for raised blood pressure.

This figure includes only results from surveys in which blood pressure was measured directly. Comparable measured data were not available for New Caledonia.

Confidence intervals were not applicable to Tokelau and Niue results as the surveys were designed to include all members of the target adult population.

Diabetes

Notwithstanding definition variations between reports, prevalence of diabetes exceeded 25% in men in nine populations, and in women in eight populations (Figure 5). Prevalence was highest in American Samoa where 53.4% (95%CI 49.0–57.9) of men and 45.0% (95%CI 41.7–48.3) of women were affected. Diabetes was least common in women in the Solomon Islands, although it still affected 14.3% (95%CI 10.8–17.9).

Figure 5.

Age‐standardised prevalence (with 95% confidence intervals) of diabetes* among those 25 to 64 years, by sex and Pacific Island Country and Territory.

Source: STEPS and similar surveys conducted between 2002 and 2011.

FSM: Federated States of Micronesia

*Diabetes was defined as fasting capillary (or venous) whole blood glucose ≥6.1mmol/L or fasting venous plasma glucose ≥7.0mmol/L whether or not the participant had previously been told by a health worker that they had diabetes; or normal fasting blood glucose and currently receiving anti‐diabetes medication prescribed by a health worker.

In addition to these core criteria, the Fiji, Republic of the Marshall Islands and Nauru reports included in the definition those with normal fasting blood glucose and on a special diet for diabetes. The Pohnpei and Kiribati reports included participants who had been advised by a health worker that they had diabetes but who had normal fasting blood glucose, and were not on anti‐diabetes medication or on a special diet prescribed by a health worker.

The figure includes only results from surveys where fasting blood glucose was measured directly. Comparable measured data were not available from the French Polynesia or New Caledonia reports.

Confidence intervals were not applicable to Tokelau and Niue results as the surveys were designed to include all members of the target adult population.

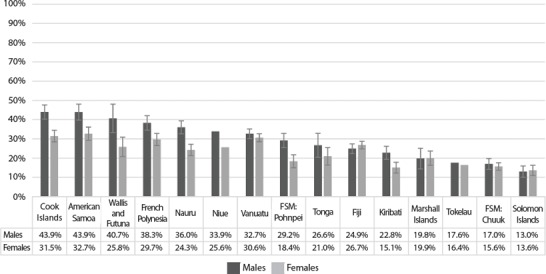

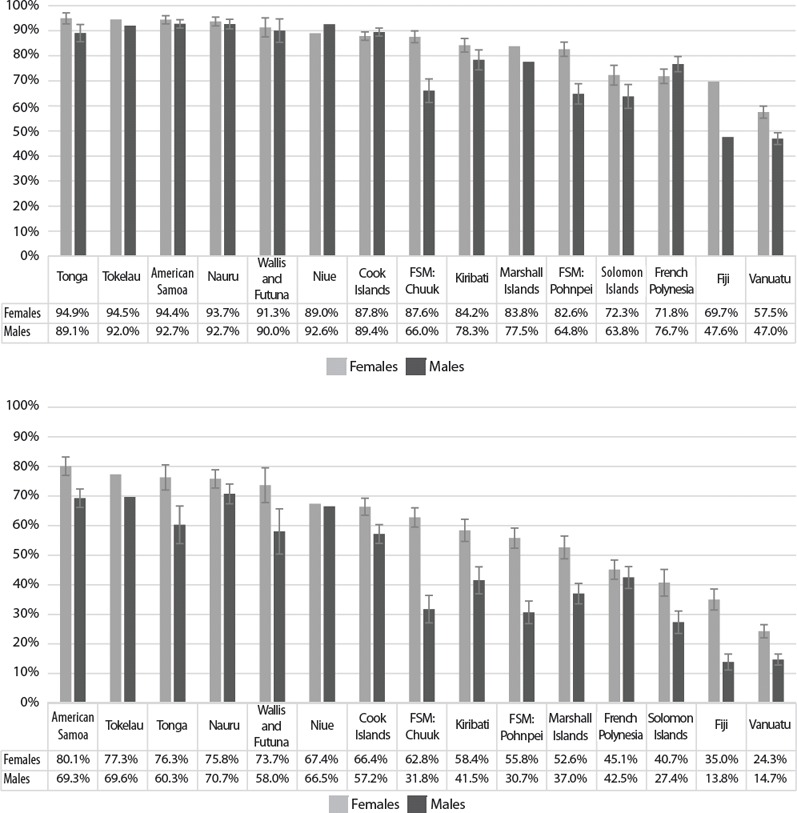

Overweight and Obesity

In eleven of fifteen PICT populations in which height and weight were measured, more than 80% of women were overweight (Figure 6). In seven populations, more than 80% of men were overweight. The lowest prevalence of overweight was in Vanuatu, although this still equated to nearly half of men and more than half of women.

Figure 6.

Age‐standardised prevalence (with 95% confidence intervals) of overweight (above) and obesity (below)* among those 25 to 64 years, by sex and Pacific Island Country and Territory.

Source: STEPS and similar surveys conducted between 2002 and 2011.

FSM: Federated States of Micronesia

*Overweight was defined as body mass index (BMI) ≥25kg/m2, obesity was defined as BMI ≥30kg/m2.

The figure includes results only from surveys in which height and weight were measured directly. Comparable data from New Caledonia were not available.

Results for overweight for the Republic of the Marshall Islands and Fiji were estimated from the addition of the prevalence of BMI ≥25 and <30, and BMI ≥30. Corresponding 95% confidence intervals were not able to be calculated.

Confidence intervals were not applicable to Tokelau and Niue results as the surveys were designed to include all members of the target adult population.

The prevalence of obesity in women exceeded 70% in American Samoa, Tokelau, Tonga, Nauru, and Wallis and Futuna (Figure 6). In men, prevalence was highest in Nauru, Tokelau and American Samoa, and lowest in Fiji and Vanuatu. Weight and height were self‐reported in New Caledonia; age‐standardised prevalence of obesity was 32.9% (95%CI 30.2–5.5) in women and 26.6% (95%CI 23.5–29.8) in men. Compared to overweight, there was a clearer demarcation between the sexes in obesity prevalence in PICTs, which affected women more than men. There was, however, wide variation between populations in the magnitude of this gender difference.

Discussion

This paper presents data aligned to the global NCD targets and indicators on the prevalence of tobacco and alcohol use, diabetes and hypertension, insufficient physical activity and overweight/obesity, from STEPS or similar surveys conducted in fifteen PICTs. The prevalence of many or all of these risk factors is high in several PICTs, demonstrating the immense burden of NCDs in the region.

Alcohol

WHO global estimates for 2010 indicate that 21.5% of male and 5.7% of female drinkers (15+ years) engage in heavy episodic drinking (defined as consumption of ≥60 g of pure alcohol – six or more standard drinks – on at least one single occasion at least monthly). 28 Comparison with the Pacific data described here is limited due to the different age ranges and definitions of heavy episodic drinking. Of those available, we selected the indicator most similar to the WHO definition and most consistently reported on across PICTs. Our analysis demonstrates that the prevalence of heavy drinking is high in several PICTs, especially among men. Our results, however, must be interpreted cautiously as in some PICT populations the number of current and heavy drinkers – particularly among women – is low, resulting in wide uncertainties around our estimates.

The gender disparity in heavy drinking in the Pacific is consistent with that observed across WHO regions. 28 Gender differences vary in magnitude between PICTs, reflecting diverse societal norms and cultures. Alcohol harm reduction initiatives in the Pacific must therefore be culturally specific, gender responsive and mindful that women may experience more harm from the same level or pattern of alcohol consumption as men. 28

Recognising that the impact of harmful alcohol use extends beyond the individual, affecting the health, social and economic welfare of families and communities, there is cause and wide scope for implementation in PICTs of identified “best buy” 29 strategies and those within the Global Strategy to Reduce Harmful Use of Alcohol. 30 Comprehensive monitoring of the effects of such action and progress towards the global target will require triangulation of information and use of multiple indicators. These can include per capita alcohol consumption, as recommended by the global framework, in addition to data on the consumption and sale of alcohol in the informal sector (home brew) in PICTs, an area in which current knowledge is limited. In addition, understanding of drinking patterns in PICTs could be expanded with further research on kava and its association with alcohol consumption.

Physical activity

Globally, 31.1% of adults (15+ years) are insufficiently physically active; women are more inactive than men and prevalence of physical inactivity is greater in high‐income countries. 31 Our results notably reveal a high prevalence of insufficient physical activity in several PICTs, especially among women.

Achieving and exceeding the global target will require enhanced efforts in this sphere. As initiatives to increase physical activity in PICTs may also address the high prevalence of overweight and obesity, their importance cannot be underestimated. Guidelines for physical activity in adults have been developed specifically for the Pacific; continuing dissemination and communication to communities is essential. 32 Further evaluation of the impact of physical activity initiatives is also needed; recommendations to enable success and longevity of programs include embedding them within national NCD strategies and partnering with multiple sectors and organisations, in government and the community. 33

Tobacco

WHO estimates for 2011 indicate that Pacific countries have some of the highest adult prevalences of current tobacco smoking within the Western Pacific, far exceeding the lowest in the region − 21% of men in Australia and New Zealand, and less than 5% of women in many Asian countries. 34

Considering the alarmingly high prevalence of smoking in PICTs, particularly among men, a 30% relative reduction in tobacco use may not sufficiently curtail the public health detriment tobacco causes. Accordingly, Ministers of Health in the Pacific have committed instead to achieving a ‘Tobacco‐Free Pacific by 2025’ with adult tobacco use prevalence below 5% in each PICT. 35 For smoking, given the significant regional inequalities in prevalence, this will be relatively more challenging for some PICTs than others. Substantial gains may be achieved with accelerated and comprehensive implementation of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) in the 14 Pacific countries that are signatories, and of equivalent measures in the PICTs that are not. First and foremost, legislation needs to be FCTC compliant. Furthermore, current impediments to implementing legislation need to be addressed in PICTs. These include insufficient capacity to enforce the law, a lack of cross‐sectoral support and limited anti‐tobacco advocacy from civil society. 36 Importantly, our analysis focuses on smoked tobacco. In parts of Melanesia and Micronesia, tobacco is commonly chewed, often in conjunction with betel nut. 37 Continuing research on the use of smokeless tobacco in the Pacific will be necessary to comprehensively monitor progress towards the targets.

Hypertension

In many PICTs, at least one‐fifth of the population has hypertension. Globally, prevalence of hypertension in those 25 years and older is about 40%, 38 and indeed men in some PICTs are similarly affected. Achieving the global target of a 25% relative reduction in hypertension prevalence is critical for the Pacific, particularly through population health strategies, as treatment costs escalate with increasingly complex regimens and can rapidly outstrip the national annual pharmaceutical budget. 39 Simultaneously, integrated cardiovascular risk management is being implemented across the Pacific through the Package of Essential NCD Interventions for Primary Health Care in Low Resource Settings. 40

Data on dietary salt intake in the Pacific are scarce and have not previously been collected in STEPS. Salt intake questions and measurements are being included in second STEPS surveys. In Fiji, and in Samoa as part of the Samoa STEPS survey, a comprehensive research initiative is underway to ascertain the change in population salt intake (including measurement of 24‐hour urinary salt levels) after implementation of salt‐reduction strategies. 41

Diabetes, overweight and obesity

The data presented reflect evidence that some of the highest prevalences of diabetes, overweight and obesity in the world are found in the Pacific. 42 , 43 Considering these unprecedented levels, PICTs must not just halt but also reverse the rise in these risk factors. This is critical considering that the costs of treatment of diabetes, like hypertension, may overwhelm health systems. 39

The impact of international trade, particularly as it affects dietary patterns, must be addressed in the Pacific. Globalisation has contributed to imported cereals replacing root crops, and fatty imported meats becoming the main sources of protein. 44 Returning to traditional diets may be challenging as in some PICTs the relative lower costs and higher convenience of imported products contribute to purchase and consumption. 45 , 46 In addition, countries' ability to enact public health policy, such as that pertaining to food imports, can be significantly constrained by international trade agreements. 47

Public health measures to tackle obesity and diabetes include taxation of sugar‐sweetened beverages. Several PICTs have introduced such taxes with fiscal and/or public health intentions. 48 To reverse the rise in obesity and diabetes, the health of younger generations must be considered. Childhood obesity has several immediate and long‐term health consequences, including a higher risk of NCDs in adulthood. 49 To be sustainably effective, PICTs' NCD strategies need to incorporate a lifecourse approach.

Implications for practice

NCD risk factors are highly prevalent and pervasive in the Pacific. Across indicators, there are inequalities between the sexes and between countries. PICTs and development partners must be cognisant of gender and inter‐country disparities. Conscious action is required to ensure that where risk factor prevalence is low, it does not increase, and that there is an equitable reduction in disease within countries and within the region. This will require quantitative and qualitative research on the underlying drivers of risk behaviours in PICTs, in order for national NCD strategies to be well‐informed and responsive to populations.

To monitor the Pacific's progress towards NCD targets, surveillance systems need to be enhanced. Regular repetition of surveys is imperative. To ensure comparability over time, it is important to maintain consistency of the questions and definitions used. STEPS, BRFSS and other NCD survey tools could be streamlined to reduce the burden that multiple surveys may place on communities.

There are several repositories of NCD data in the Pacific. These need to be streamlined and integrated with those for communicable diseases to promote a more integrated approach to health system planning nationally and regionally. Additionally, intense efforts are required to build in‐country capacity for data analysis, to ensure PICTs have ownership of their survey results and access to them in a timely manner. The Pacific Public Health Surveillance Network has been implementing the Fiji National University‐accredited ‘Data for decision‐making’ program. This program for health professionals working with health information covers both communicable and noncommunicable diseases and is designed to improve in‐country surveillance and health information systems.

Strengths and limitations

By utilising results from standardised surveys conducted across the region, this work provides a comprehensive, Pacific‐focused perspective on NCDs and their risk factors. Furthermore, the data this analysis uses are often the primary source of NCD information for PICTs, upon which national policies and health care planning are based.

There are several limitations to this work. The surveys used in this analysis were conducted between 2002 and 2011; the epidemiology of NCDs would likely have changed since. By only utilising data from published reports of STEPS and similar surveys, our analysis is confined to fifteen PICTs. Full reports were not available for STEPS surveys from Samoa and Papua New Guinea, although fact sheets providing crude rates have been published through WHO. Information from other sources such as BRFSS would also enhance the perspective presented here.

As detailed in some reports, sampling frames may be limited due to costs or logistical challenges of surveying certain areas or islands. Results are consequently not always nationally representative.

Occasionally, survey reports present results using unique indicator definitions. Where this occurred, we had to exclude results to preserve the validity of comparisons, or calculate best possible estimates using the available data.

This analysis includes those aged 25 to 64 years. NCDs and the forces that drive them exert their influence at much earlier ages. Synthesis of data on risk factor prevalence in children and adolescents is needed.

We were unable to assess differences in age‐standardised prevalence of risk factors by socioeconomic status, rural/urban residence and ethnicity, as the required elements for such an analysis were unavailable. Of note, the Fiji STEPS report provides aggregate results by sex for locality and ethnicity. It would be useful to include these covariates in all future PICT survey reports, to ascertain the leading drivers of the NCD epidemic and the inequalities within.

This work focuses on the primary indicators corresponding to the main targets chosen by the Global NCD Action Plan. STEPS can also be used to track progress on additional indicators of fruit and vegetable consumption and total cholesterol level. Mean population glucose and mean population BP are also available to monitor the respective targets.

Fundamentally, STEPS – and therefore this analysis – is limited to the ‘traditional’ NCDs. While there is an optional STEPS module for mental health, this has not yet been implemented in PICTs. Further, no such module exists for musculoskeletal diseases. Improving surveillance of both these conditions is essential; depression and low back pain cause the highest two amounts of disability in the Pacific and globally. 3 , 50 , 51 Opportunities to monitor and respond to these NCDs are urgently needed and are currently being missed.

Conclusion

Given that present risk factor distribution is indicative of future disease prevalence, the outlook for the Pacific is ominous. With limited financial resources and capacity, prioritisation of targets and corresponding interventions is required. The “best buys,” cost‐effective initiatives which can significantly reduce premature mortality and economic losses in PICTs, are the foundation of the crisis response. In alignment with the policy options discussed earlier, they include: i) increasing tobacco taxation, restricting tobacco marketing and implementing smoke free environments; ii) increasing taxation on, and restricting access to and advertising of alcohol; iii) reducing salt intake; and iv) implementing multiple drug therapy and counselling for those at risk of cardiovascular events. 29

Current investment by international and regional organisations and countries themselves to tackle NCDs, however, is insufficient and disproportionate to their prevalence and impact. The case for augmented cross‐sector action on the Pacific NCD emergency is unassailable and investments need to ensure adherence to the principles of development effectiveness. Substantial further funding, escalated action and accountability by all partners and stakeholders are essential to prevent NCDs from crippling health systems and arresting economic and social development in the Pacific islands.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr Colin Tukuitonga who provided the concept for this article. We also thank Dr Yvan Souarès for his guidance with this work. We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of national health staff in the Pacific who undertook the surveys that were used to inform this paper. We also appreciate the contribution of the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to this process.

The authors have stated they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Secretariat of the Pacific Community . Déclaration de Tahiti Nui ‐ Tahiti Nui Declaration (revised November 2011) [Internet]. Noumea (NCL): SPC; 2012. [cited 2014 Sep 2]. Available from: http://www.spc.int/images/publications/ef/Corporate/ef-tahiti-nui-declaration.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat . Proceedings of the Forty‐Second Pacific Islands Forum Communique; 2011. September 7–11; Auckland, New Zealand.

- 3. Hoy D, Roth A, Viney K, et al. Findings and implications of the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study for the Pacific Islands. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014; 11: 130344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anderson I. The Economic Costs of Noncommunicable Diseases in the Pacific Islands. A Rapid Stocktake of the Situation in Samoa, Tonga and Vanuatu Health, Nutrition, and Population (HNP) Discussion Paper. Washington (DC): World Bank Group; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization . Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020. Geneva (CHE): WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Healthy Pacific Lifestyle Section Public Health Division . NCD Statistics for the Pacific Islands Countries and Territories. Noumea (NCL): Secretariat of the Pacific Community; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bonita R, de Courten M, Dwyer T, et al. Surveillance of Risk Factors for Noncommunicable Diseases: The WHO STEPwise Approach. Summary. Geneva (CHE): WHO; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): CDC; 2015. [cited 2014 Sep 2]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/ [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization . WHO STEPS Surveillance Manual. Geneva (CHE): WHO; 2008. [cited 2014 Aug 6]. Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/steps/manual/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 10. American Samoa Government and WHO Western Pacific Region . American Samoa NCD Risk Factors STEPS Report [Internet]. Manila (PHL): WHO; 2007. [cited 2014 Apr 10]. Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/steps/american_samoa/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 11. Te Marae Ora, Ministry of Health Cook Islands and WHO Western Pacific Region . Cook Islands NCD Risk Factors STEPS Report [Internet]. Manila (PHL): WHO; 2011. [cited 2014 Feb 4]. Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/steps/cook_islands/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ministry of Health Fiji . Fiji Non‐communicable Diseases (NCD) STEPS Survey [Internet]. Manila (PHL): WHO; 2002. [cited 2014 Feb 4]. Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/steps/fiji/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ministère de la Santé Direction de la Santé Polynésie française and WHO Western Pacific Region . Enquête santé 2010 en Polynésie française. Surveillance des facteurs de risque des maladies non transmissibles [Internet]. Manila (PHL): WHO; 2010. [cited 2014 Apr 10]. Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/steps/french_polynesia/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kiribati Ministry of Health and Medical Services and WHO Western Pacific Region . Kiribati NCD Risk Factors STEPS Report [Internet]. Manila (PHL): WHO; 2009. [cited 2014 Feb 4]. Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/steps/kiribati/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ministry of Health Republic of the Marshall Islands and WHO Western Pacific Region . NCD Risk Factors STEPS Report, 2002 [Internet]. Manila (PHL): WHO; 2007. [cited 2014 Apr 10]. Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/steps/marshall_islands/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 16. Government of the Federated States of Micronesia and WHO Western Pacific Region . Federated States of Micronesia (Chuuk) NCD Risk Factors STEPS Report [Internet]. Manila (PHL): WHO; 2012. [cited 2014 Feb 4]. Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/steps/reports/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 17. Government of the Federated States of Micronesia and WHO Western Pacific Region . Federated States of Micronesia (Pohnpei) NCD Risk Factors STEPS Report [Internet]. Manila (PHL): WHO; 2008. [cited 2014 Apr 10]. Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/steps/reports/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 18. Republic of Nauru and WHO Western Pacific Region . Nauru NCD Risk Factors STEPS Report [Internet]. Manila (PHL): WHO; 2007. [cited 2014 Apr 10]. Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/steps/reports/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 19. Niue Health Department and WHO Western Pacific Region . Niue NCD Risk Factors STEPS Report [Internet]. Manila (PHL): WHO; 2013. [cited 2014 Feb 4]. Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/steps/reports/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 20. Agence Sanitaire et Sociale de la Nouvelle‐Calédonie . Baromètre Santé Nouvelle‐Calédonie 2010 Résultats préliminaires [Internet]. Nouméa (NCL): ASSNC; 2011. [cited 2014 Jul 9]. Available from: http://www.ass.nc/etudes-et-recherches/barometre-sante/les-resultats-preliminaires [Google Scholar]

- 21. Solomon Islands Ministry of Health and Medical Services and WHO Western Pacific Region . Solomon Islands NCD Risk Factors STEPS Report [Internet]. Manila (PHL): WHO; 2010. [cited 2014 Apr 10]. Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/steps/reports/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tokelau Department of Health and WHO Western Pacific Region . Tokelau NCD Risk Factors STEPS Report [Internet]. Manila (PHL): WHO; 2007. [cited 2014 Apr 10]. Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/steps/reports/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ministry of Health Kingdom of Tonga and WHO Western Pacific Region . Kingdom of Tonga NCD Risk Factors STEPS Report [Internet]. Manila (PHL): WHO; 2012. [cited 2014 Apr 10]. Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/steps/reports/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vanuatu Ministry of Health and WHO Western Pacific Region . Vanuatu NCD Risk Factors STEPS Report [Internet]. Manila (PHL): WHO; 2013. [cited 2014 Apr 10]. Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/steps/reports/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 25. New Caledonia Renal Failure Network, Wallis and Futuna Statistics and Economic Surveys Departments and Secretariat of the Pacific Community Public Health Division . Study of Risk Factors for Chronic Non‐communicable Diseases in Wallis and Futuna [Internet]. Noumea (NCL): SPC; 2010. [cited 2014 Apr 10]. Available from: http://www.spc.int/images/publications/en/Divisions/Health/en-wallis-futuna_ncd_report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ahmad OB, Boschi‐Pinto C, Lopez AD, et al. Age Standardization of Rates: A New WHO Standard GPE Discussion Paper Series No.: 31. Geneva (CHE): World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Breslow NE, Day NE. Volume II ‐ The Design and Analysis of Cohort Studies In: Statistical Methods in Cancer Research IARC Scientific Publications No 82. Lyon (FRA): World Health Organization International Agency for Research on Cancer; 1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. World Health Organization . Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health ‐ 2014. Geneva (CHE): WHO; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29. World Health Organization and World Economic Forum . From Burden to “Best Buys”: Reducing the Economic Impact of Non‐Communicable Diseases in Low‐ and Middle‐Income Countries. Geneva (CHE): World Economic Forum; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30. World Health Organization . Global Strategy to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol. Geneva (CHE): WHO; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, et al. Global physical activity levels: surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet. 2012; 380 (9838): 247–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. World Health Organization . Pacific Physical Activity Guidelines for Adults: Framework for Accelerating the Communication of Physical Activity Guidelines. Manila (PHL): WHO Western Pacific Regional Office; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Siefken K, Macniven R, Schofield G, et al. A stocktake of physical activity programs in the Pacific Islands. Health Promot Int. 2012; 27 (2): 197–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. World Health Organization . WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2013: Enforcing Bans on Tobacco Advertising, Promotion and Sponsorship. Geneva (CHE): WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Apia Communiqué on Healthy Islands, NCDs and the Post‐2015 Development Agenda . Tenth Pacific Health Ministers Meeting; 2013 July 4. Samoa. Suva (Fiji): World Health Organization; 2013. [cited 2014 Jul 11]. Available from: http://www.wpro.who.int/southpacific/pic_meeting/2013/meeting_outcomes/10th_PHMM_Apia_Commnique.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 36. Martin E, de Leeuw E. Exploring the implementation of the framework convention on tobacco control in four small island developing states of the Pacific: A qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2013; 3: e003982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. World Health Organization . Review of Areca (Betel) Nut and Tobacco Use in the Pacific. A Technical Report. Manila (PHL): WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 38. World Health Organization . Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2010. Geneva (CHE): WHO; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Anderson I, Sanburg A, Aru H, et al. The costs and affordability of drug treatments for type 2 diabetes and hypertension in Vanuatu. Pac Health Dialog. 2013; 19 (2): 1. [Google Scholar]

- 40. World Health Organization . Package of Essential Noncommunicable (PEN) Disease Interventions for Primary Health Care in Low‐resource Settings. Geneva (CHE): WHO; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Webster J, Snowdon W, Moodie M, et al. Cost‐effectiveness of reducing salt intake in the Pacific Islands: Protocol for a before and after intervention study. BMC Public Health. 2014; 14 (1): 107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. World Health Organization . Global Health Observatory, Risk Factors [Internet]. Geneva (CHE): WHO; 2014. [cited 2014 Aug 20]. Available from: http://www.who.int/gho/ncd/risk_factors/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014; 384 (9945): 766–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hughes RG, Lawrence M. Globalisation, food and health in Pacific Island countries. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2005; 14 (4): 298–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Corsi A, Englberger L, Flores R, et al. A participatory assessment of dietary patterns and food behavior in Pohnpei, Federated States of Micronesia. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008; 17 (2): 309–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Evans M, Sinclair RC, Fusimalohi C, et al. Globalization, diet, and health: An example from Tonga. Bull World Health Organ. 2001; 79: 856–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Snowdon W, Thow AM. Trade policy and obesity prevention: Challenges and innovation in the Pacific Islands. Obes Rev. 2013; 14 (S2): 150–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Thow AM, Quested C, Juventin L, et al. Taxing soft drinks in the Pacific: implementation lessons for improving health. Health Promot Int. 2011; 26 (1): 55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Reilly JJ, Kelly J. Long‐term impact of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence on morbidity and premature mortality in adulthood: Systematic review. Int J Obes. 2010; 35 (7): 891–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hoy D, March L, Brooks P, et al. The global burden of low back pain: Estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014; 73: 968–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Vos T, Flaxman A, Naghavi M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012; 380: 2163–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]