Abstract

The revision of the structure of the sesquiterpene aquatolide from a bicyclo[2.2.0]hexane to a bicyclo[2.1.1]hexane structure using compelling NMR data, X-ray crystallography, and the recent confirmation via full synthesis exemplify that the achievement of “structural correctness” depends on the completeness of the experimental evidence. Archived FIDs and newly acquired aquatolide spectra demonstrate that archiving and rigorous interpretation of 1D 1H NMR data may enhance the reproducibility of (bio)chemical research and curb the growing trend of structural misassignments. Despite being the most accessible NMR experiment, 1D 1H spectra encode a wealth of information about bonds and molecular geometry that may be fully mined by 1H iterative full spin analysis (HiFSA). Fully characterized 1D 1H spectra are unideterminant for a given structure. The corresponding FIDs may be readily submitted with publications and collected in databases. Proton NMR spectra are indispensable for structural characterization even in conjunction with 2D data. Quantum interaction and linkage tables (QuILTs) are introduced for a more intuitive visualization of 1D J-coupling relationships, NOESY correlations, and heteronuclear experiments. Overall, this study represents a significant contribution to best practices in NMR-based structural analysis and dereplication.

Introduction

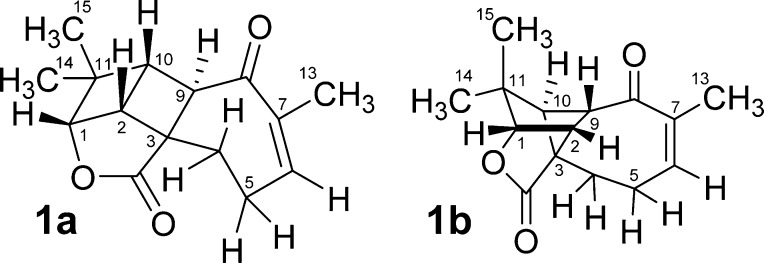

Despite major advances in analytical spectroscopy, structural elucidation of both natural and synthetic compounds continues to be a major challenge, as is illustrated by the recent revision of the structure of aquatolide (1a/1b), a natural product isolated from Asteriscus aquaticus. Initially reported as containing a bicyclo[2.2.0]hexane core substructure, 1a (Figure 1),1 upon subsequent re-examination of the spectroscopic data, indicated the structure to be more consistent with bicyclo[2.1.1]hexane 1b.2 This structural revision was supported by a detailed NMR analysis spurred on by quantum chemical calculations and confirmed through X-ray crystallography.

Figure 1.

Originally proposed (1a) and revised structure (1b) of aquatolide.

The problem of misassigned spectra ultimately leading to incorrect structural assignments is becoming a more prevalent feature in the contemporary chemical literature with no apparent signs of abating.3−7 In fact, there have been in excess of 160 articles describing structural revisions of organic molecules, predominately as a result of spectral misassignment, in the decade since Nicolaou and Snyder published their comprehensive review in 20058 on misassigned structures as revealed by chemical synthesis.

To curb the growing trend of reported misassigned structures, we propose an approach that better utilizes the vast structural information contained in the ubiquitously acquired 1D 1H NMR data sets with the purpose of achieving “structural correctness” while at the same time enhancing the reproducibility of downstream research performed with the structurally correct compound in question. The present study demonstrates that practically everything the chemist needs to know for a correct structural elucidation process is contained in the proton NMR FIDs. Our proposed protocol involves analysis of 1D 1H spectra including both quantum-mechanical prediction of chemical shifts (δ) and scalar coupling constants (J) as well as extraction of compound-specific 1H NMR spectral parameters from the experimental data. Although even classical manual analysis of the spectra is capable of providing sufficient information to verify (or revise) a structure, we demonstrate here that an iterative fitting process utilizing quantum mechanical spin information (HiFSA)9 is indispensable for achieving rigorous structural elucidation and dereplication with a high degree of reproducibility.

To preserve the authenticity of reported spectral information, originally acquired free induction decays (FIDs) should be made available for published structures.10 The approach described here is applied to aquatolide by analysis of the published data together with a reprocessing and HiFSA fitting of the 1H FID that was archived in 2012 and provided by the authors of the revision article.2 A thorough analysis of the data revealed the dangers and pitfalls of a superficial treatment of 1D NMR spectroscopic data and will hopefully serve as a future guide for avoiding similar spectral misinterpretations, including deduction of newly discovered structures that were not there initially.8

Results and Discussion

Chemical Shift Plausibility

The key to both the suitability of a proposed structure, or guidance for its revision, may be found in the 1D 1H and 13C NMR spectra. In the case of aquatolide, the suspect structure 1a was recently evaluated by comparing the experimental data with that of the 13C and 1H chemical shifts predicted with quantum chemical calculations. Significant deviations (ΔδC) of up to 24.33 ppm in the 13C domain indicated a potential problem with the originally assigned structure. Over 60 alternative scaffolds, along with their diastereomers, were generated by both rational and arbitrary changes to the original structure. One alternative structure, 1b (originally suggested by P.B. Jones), yielded a much better predictive fit than the original structure with the largest ΔδC of 4.28 ppm. The prediction of the 1H NMR chemical shifts of aquatolide demonstrated much the same trend as the 13C study. The revised structure, 1b, exhibited a better fit (largest ΔδH = 0.27 ppm) than the original structure with the largest ΔδH = 1.31 ppm. Although deviations of such magnitude are widely accepted as representing a reasonable gap between theoretical or empirical predictions and experimental observations,11,12 it is also well-known that nearly identical yet different molecules can exhibit very minute chemical shift differences in the range of up to a few hundred ppb in 13C and only a few tenths to sub ppb level in 1H NMR spectra.13,14 This obvious contradiction provides a rationale for the need to perform comprehensive mining of 1D NMR data in general structure analysis.

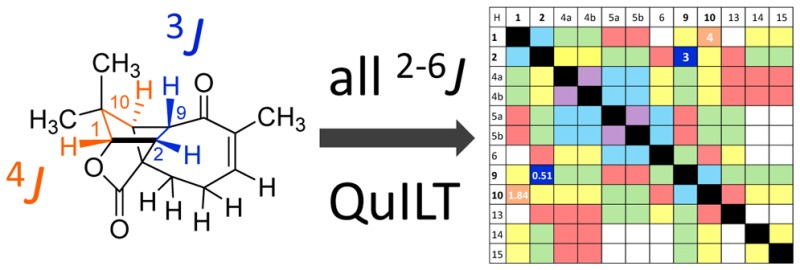

Correlation Maps Visualize Coupling Networks

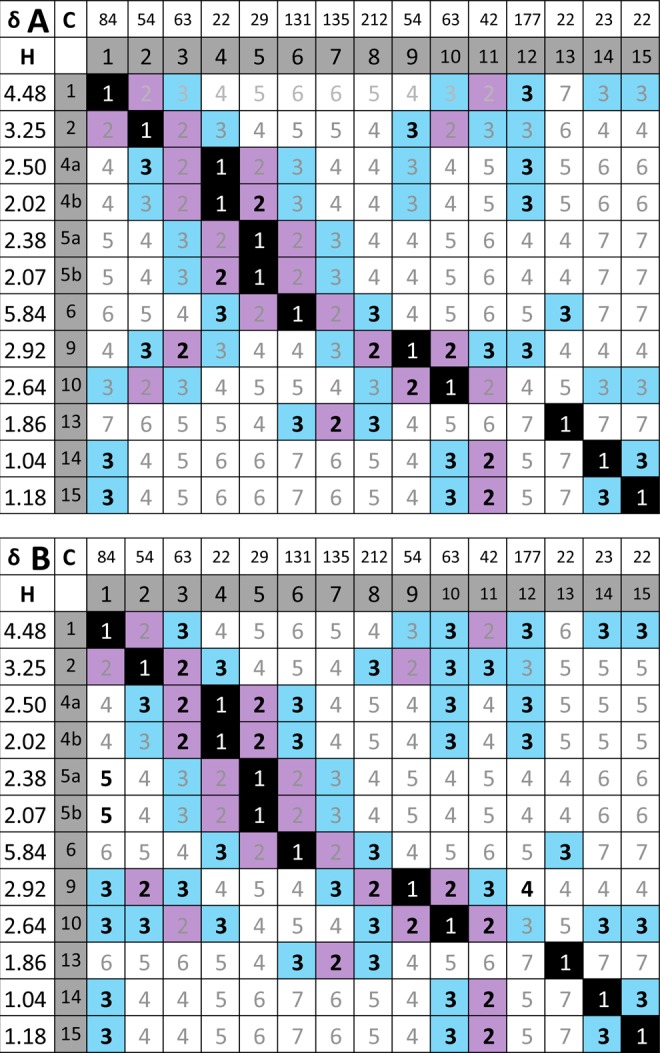

In the structural revision, the evaluation of 1H coupling constants and multiplicities faced the challenge of a lack of comparison due to the meager information content in the original reference article.1 The quantity of coupling information obscured by multiplets in the original article can be demonstrated by compiling the reported couplings into a J-correlation map: Figure 2A graphs all possible scalar coupling combinations present in the molecule in the lower left half,2 whereas the corresponding number of bonds between coupled nuclei are given in the upper right half. The map demonstrates the inherent risk associated with the reporting of “multiplets.” For example, only three couplings were reported mutually for the pair of coupled nuclei (3JH-1,H-2, 4JH-1,H-10, 3JH-2,H-10) and only one of the two couplings (2JH-4a,H-4b, 3JH-4a,H-5b), as indicated by the divided cells in Figure 2A. Ignoring characteristic long-range couplings (4–5J), only six out of a total of 22 values that reflect the pairwise relationship of all possible 3J and 2J couplings were reported. The unreported 2J and 3J couplings were obscured by “multiplets” or simply not observed. A 4J coupling of 1.9 Hz was proposed for nuclei H-1 and H-10, but neither the observed nor the conspicuously unobserved couplings were actually discussed in the original article.

Figure 2.

J-correlation map of the homonuclear proton NMR assignments reported for the original (erroneous) A and revised B structures of aquatolide (δ in ppm, M = reported multiplicity). Cells in the upper right are the number of bonds separating the two hydrogens. In the lower left are the observed coupling constants in Hz. Unresolved multiplets were designated by “m.” ø are 3J coupling constants that are less than 1.0 Hz due to ∼90 deg dihedral relationships. The addition of “a” in the bond numbers 4a and 5a indicate (homo)allylic coupling relationships. Split cells in the lower left represent coupling constants that are unequally reported for the two nuclei, likely referring to observed line distances rather than coupling constants. Yellow boxes in B indicate changes in bond number compared with the original structure.

Consequences of Incomplete Correlation Maps

The apparent lack of attentiveness to coupling patterns and coupling constants exposes a general attitude that 1D proton NMR data is both uninterpretable, at least in great parts, and inferior to that of many 2D experiments. Unfortunately, this lack of attention to 1H NMR spectra (the “mother of all NMR experiments”) is very common in both the natural product structural elucidation literature and reports on the structural characterization of synthetic compounds. In the case of aquatolide, the original authors were likely led astray by resorting to the all-too-common practice of moving on to the 2D data without thoroughly understanding the 1D data. Moreover, Lodewyk et al. deemed the existing 2D data incapable of definitively verifying the revised structure.2 Thus, the compound was reisolated from Asteriscus aquaticus, and an NMR analysis was performed at 800 MHz. It is reasonable to assume that the two isolates yielded the same compound despite the lack of reference material from the original work because the 1H and 13C data sets appear to be very similar. A detailed analysis of the proton data was performed after reisolation. The progress achieved with the revision2 is illustrated in the J-coupling correlation map in Figure 2B, showing the reported experimental values for the revised aquatolide structure. In this case, five out of 18 3J couplings and one out of four 2J couplings were observed. Interestingly, five 4J and two 5J long-range couplings were observed due to the rigid ring structure and presence of an α,β unsaturated ketone.

Although the NMR results in the 2012 study represented a substantial qualitative improvement over the data reported in the original article,1 a different overall focus and approach did not lead to an exhaustive description of the chemical shifts (δ) and scalar coupling constants (J) present in this molecule by resolving highly complex 1H NMR signal patterns. In fact, a thorough treatment of all relevant 1D and 2D NMR data is generally discouraged by current journal practices, relegating in the best case such critical NMR information to the Supporting Information. These practices only serve to reinforce the myth that 1H NMR data is both ambiguous and inferior to 2D NMR data.

In the revision,2 the use of quantum chemical prediction tools for evaluating the observed scalar coupling network led to a complete, yet theoretical, J-correlation map (Supporting Information, Figure S1).15 The predictive exercise proposed 14 coupling constants above 1.0 Hz, of which ten were observed for at least one proton. Notably, the prediction confirmed several instances of unusual coupling behavior, including the unobservable to 3JH-2,H-9 and 3JH-9, H-10 couplings with near zero values.

However, several challenges remained for a comprehensive representation of the coupling network: (i) the magnitude of the coupling constants obscured by multiplets cannot be confirmed or unconfirmed; (ii) four of the observed coupling constants exhibit deviations of 0.5–0.8 Hz from the predicted values; (iii) the relative positions of protons 4a, 4b, 5a, and 5b could not be determined with certainty due to the ambiguity of matching all of their exact chemical shifts; (iv) two 3J coupling constants are nearly undetectable (<1.0 Hz), whereas five 4J and 5J long-range coupling constants are >1.0 Hz, the origin of which requires a closer examination.

Raw NMR Data (FIDs) Enable Multiplet Analysis

Data produced by modern FT-based NMR experiments are time domain data, free induction decays (FIDs) or series thereof, which are stored, processed, and handled digitally. FIDs are relatively small files, machine and vendor specific, but in relatively transparent file formats, and importantly are easy to archive. Commercial as well as free software tools are available for (re)processing FIDs (see, e.g., http://nmr-software.blogspot.com/ for a listing and links). Moreover, the resolution of multiplets may be achieved, in many cases, by optimizing post-acquisition data processing parameters.

The present study became possible because the 1H FID of the newly isolated aquatolide (1b) was archived and accessible via the authors.2 Thus, the 800 MHz 1H FID could be reprocessed with resolution enhancement (e.g., Lorentzian–Gaussian apodization) to resolve even very small coupling constants (∼1.0 Hz) as line splittings in all signals. Manual spectral interpretation of an optimized spectrum led to a more complete J-correlation map (Figure 3A), showing that “multiplets” may be tentatively resolved through optimized processing of FIDs and no additional experiments. Visual interpretation of the resulting highly resolved multiplets may be facilitated by software tools, such as Schimanski’s jVisualizer (http://jvisualizer.sourceforge.net/), to help simulate the line patterns of manifold-coupled resonances using first order assumptions. In most cases, the manually extracted J-couplings matched up well (within 1 Hz, often much better) with the predicted values (Figure 3). It is noteworthy to mention that strong apodization for very strongly enhanced resolution can affect both the exact line distances as well as the relative intensities of individual lines within resonances and of resonances relative to each other. Accordingly, HiFSA processing typically uses spectra that are not or only weakly apodized.

Figure 3.

(A) Results of reprocessing the FID from the 800 MHz 1D 1H NMR spectrum of aquatolide displayed on a J correlation map. The number of bonds separating two coupled nuclei are color-coded: violet = 2J, blue = 3J, yellow = 4J, green = 5J, and pink = 6J. The gaps in the colored fields of the lower left indicate the limitation of achievable coverage with manual spin analysis. Whereas all couplings of ∼1 Hz or more could be readily extracted, determination of the long-range J-couplings typically requires a computational approach. (B) Final J-correlation map, termed quantum interaction and linkage table (QuILT; see main text), achieved by HiFSA fitting of the archived 800 MHz 1D 1H NMR data of aquatolide. Multiplicities in parentheses are less than ∼1 Hz. Couplings less than absolute value of 0.10 Hz are given as “⌀” rather than being reported as blank cells, which would indicate them being unknown or undetermined.

Introduction of color coding to the J-correlation map in Figure 3A visually connects the two near symmetric halves of the J-correlation map, i.e., connecting bonds and coupling constant(s). This facilitates two important elements of 1D 1H NMR interpretation: (a) verification of all coupling constants that should be present due to geminal (2J) and vicinal (3J) relationships with the notable exception of couplings that are (near) zero due to (near) perpendicular dihedral bond angles; and (b) detection of long-range couplings (≥4J) that are characteristic for the given structure, such as aromatic, allylic, homoallylic, and W-type couplings. Although these couplings are often small (up to ∼3 Hz), they can reach values of >10 Hz under certain circumstances, such as the 2-fold W-type coupling pathway that is present in compound 1b showing a 7.2 Hz 4JH-2,H-10. Accordingly, it is important to keep in mind that, in the same molecule, geminal and vicinal J values can be smaller than long-range J values and potentially generate confusion in the early interpretation process. Again, 1b is a perfect example of such a situation as two 3J couplings are near zero, whereas five long-range couplings lead to signal splittings in the 1.5–7.2 Hz range.

HiFSA Enables Quantum Interaction and Linkage Tables (QuILTS)

The aforementioned data processing and prediction methodologies will likely still exhibit gaps between observed and predicted values. Naturally, these must be investigated and resolved to fully confirm the structure and utilize the information contained in the data. The HiFSA technique iteratively fits, within the limits allowed by the conformation and quantum mechanical parameters, the predicted values into the observed spectrum9 to create a high resolution data set that completely defines the J-coupling network (see ref (16) for a discussion of δ and J precision). This enables completion of the J-correlation map, creating a quantum interaction and linkage table (QuILT). This comprehensive approach allows the researcher to analyze a definitive homonuclear data set to base structural assignments on the most definite information that can be derived from the data.

Intelligent Use of HNMR Observations

Even in the case of nearly matching theoretical and observable data, the final values need to be correlated with known NMR results and the structural features of the molecule. This is a process that cannot be completely automated and requires the intervention of a knowledgeable spectroscopist. Whereas every shift and coupling constant computed with quantum mechanical calculations (for a review, see ref (11)) is associated with a specific structural feature, a frequent issue is merely whether these values are predicted with high enough accuracy to assign experimental values that are very close to each other unambiguously.

In the case of aquatolide, a 4J constant greater than 7 Hz is certainly worthy of closer inspection, as are two 3J values of nearly zero, all occurring in the same molecule of only 15 carbons. Ideally, all observed and potentially observable J-couplings should be verified by considering the impact of geometries, such as the phenomena associated with strained rings and allylic and homoallylic relationships.

Another role for the HiFSA process, which involves the prediction of spin parameters from energy-minimized structures as starting values for the iteration,9 is the use of the chemical shift and J-coupling predictions to distinguish between the two structures. As shown in Figure 4A, significant differences exist between both proposed structures and the actual (fitted) values, especially in the bicyclic ring structure involving protons H-1, H-2, H-9, and H-10. The average difference of chemical shifts (Δδ) in the final HiFSA profile favors the revised structure, 0.3060 ppm compared to 0.3990 ppm for the original structure. However, this comparison alone is not conclusive as the chemical shift prediction algorithms are not yet mature enough to distinguish between the near-identical molecules, 1a/1b.

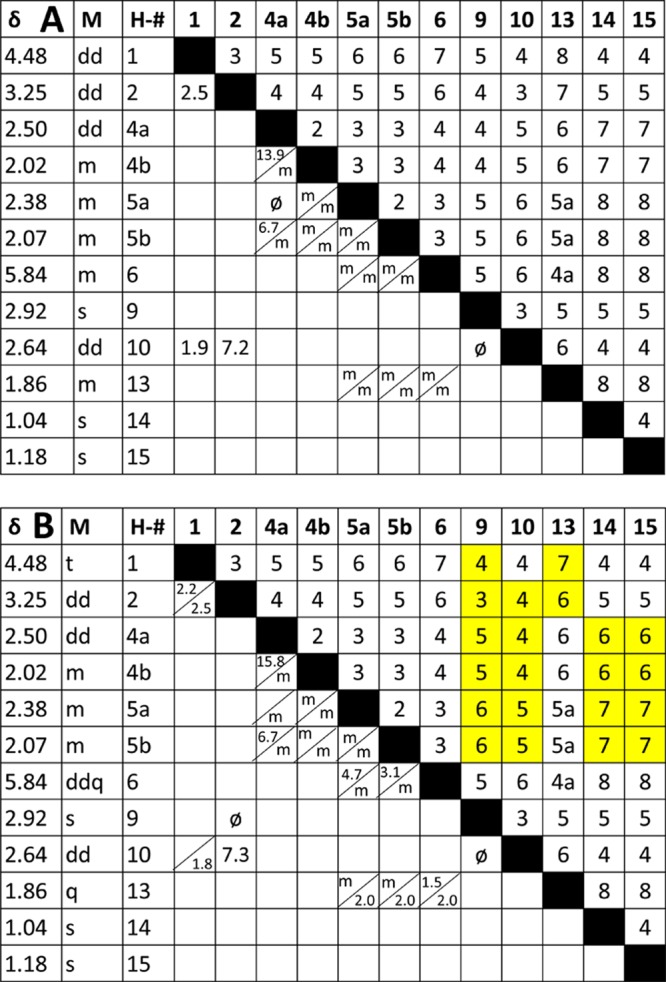

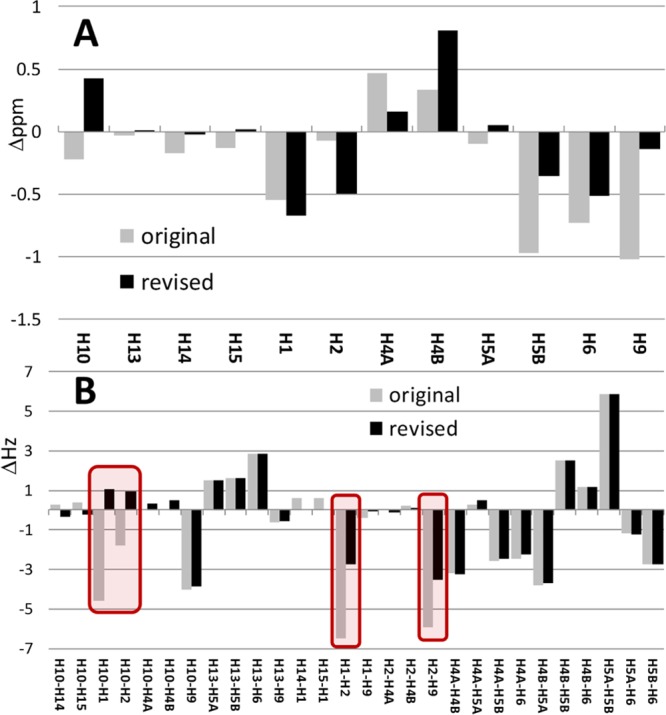

Figure 4.

Difference of chemical shifts (in ppm, A) and coupling constants (in Hz, B) between the HiFSA fitted structure and the original vs revised structures.

In contrast, comparison of the coupling constants in Figure 4B shows that the revised structure exhibits a better fit, especially in the bicyclic ring structure. Although the average difference (ΔJ) across all 28 coupling constants of 1.643 Hz already favors the revised structure compared to 2.063 Hz for the original structure (ΔΔJ = 0.420 Hz), Figure 4B shows that four individual coupling constants exhibit major differences with a total ΔJ of 14.551 Hz (average of 3.638 Hz). The four critical spots of J pattern interpretation are as follows. (i) The magnitude of the 3JH-1,H-2 for a dihedral relationship of ∼ 0° in 1a would be more in line with a value of ∼9 Hz, contrasting the 2.502 Hz measured. (ii) In cyclobutane relationships, the coupling between H-2 and H-9 cannot be neglected, especially not a 4Jtrans as present in 1a, which are known to give rise to coupling constants of up to −3 Hz;17 the revised interpretation as a 3J of 0.513 Hz in 1b demonstrates how potentially misleading the (apparent) lack of coupling can be. (iii) Representing the cyclobutane form of a 2-fold “W” or “4Jcis” coupling, known to reach up to 18 Hz,18 the 4JH-1,H-10 relationship would be expected to be much larger in the original structure, 1a. (iv) The 3JH-2,H-10 relationship would be expected to be ∼2 Hz larger than was measured. Considering that couplings are related to structure, geometry, and bonding, it is important to keep in mind that both the absolute differences and the signs of the coupling constants are diagnostic and indicative of the correct structure.

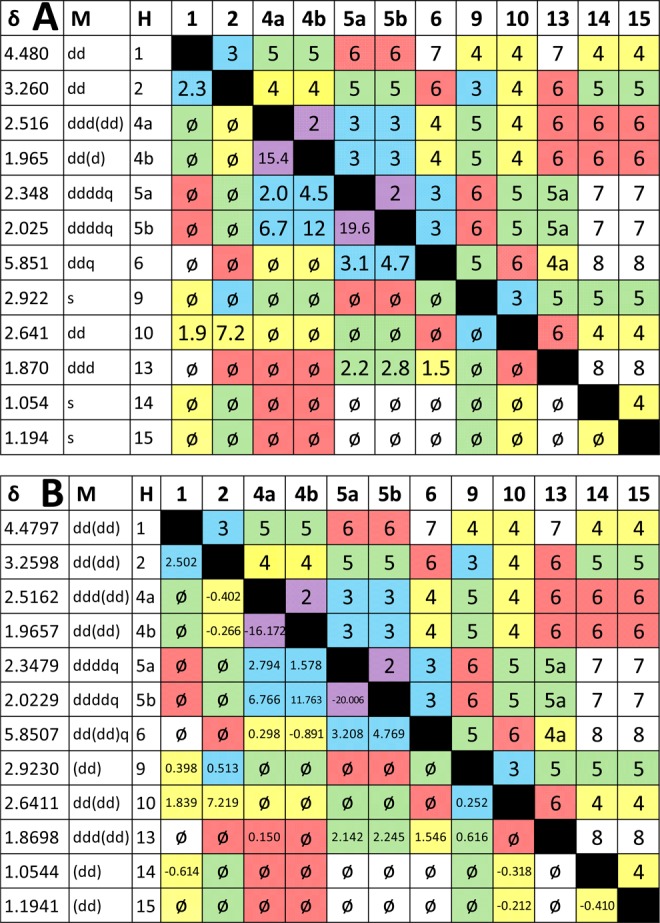

Full HNMR Interpretation of Aquatolide (1b)

The following analysis provides a model treatment of 1H homonuclear NMR data, which should be reported for even apparently straightforward structural assignments. Confirmation employing 2D data sets is appropriate after the 1D spectrum has been thoroughly examined and can focus on issues that are otherwise not fully resolved.

Bicyclo[2.1.1]hexane Core Protons

H-1 is the only proton on the two-carbon bridge of the bicyclo[2.1.1]hexane core of 1b. The chemical shift of this signal is at δ 4.4797 ppm because it is deshielded by the adjacent lactonic alkyl oxygen. The signal was reported as a dd in the original article and as a triplet in the revision article. The 3J coupling with H-2 (2.502 Hz) at the closest bicyclo[2.1.1]hexane bridgehead is clearly observed but rather small due the 50° dihedral angle. A 4J (by two pathways) coupling of 1.839 Hz is observed with H-10, the remote bicyclo[2.1.1]hexane bridgehead proton. The occurrence of 4J couplings in strained rigid ring systems has been previously described19,20 and exemplifies the significance of long-range couplings in general.21 The original aquatolide structure also placed H-1 at a position where it was three bonds away from H-2 and four bonds away from H-10. However, in the original structure, the dihedral angle between H-1 and H-2 approaches 0°.

Proton H-2 occupies a bridgehead position of the bicyclo[2.1.1]hexane core of 1b. The chemical shift of its dd signal is at δ 3.2598 ppm, making it the third most downfield proton in this molecule. Interestingly, the 3J coupling with H-9 on the cyclobutane ring is not observed. The quantum chemical calculations put the coupling constant at less than 0.5 Hz (predicted at −0.119 Hz), which is due to a nearly 90° dihedral angle. The 4JH-2,H-10 coupling (by two routes) on the two bridgehead carbons is a remarkable 7.219 Hz. This is remarkably large for a saturated 4J coupling. However, this value may be predicted (HiFSA processing predicted 6.299 Hz, the quantum mechanical calculations yielded 6.767 Hz) and has been observed in other cyclobutanes22 as well as in bicyclo[2.1.1]hexane derivatives.19 The magnitude of this coupling may be attributed to the rigid W conformation present in the molecule and the fact that there are two parallel 4J coupling pathways. Notably, the H-2 coupling pattern and J values are very likely the explanation as to why, in the original aquatolide structure, protons H-2 and H-9 were placed into a 4J relationship, whereas protons H-2 and H-10 were placed into a 3J relationship. A 7.2 Hz 3J coupling and an unobservable 4J coupling may have seemed more reasonable by the authors of the original assignment but are fully explained by the revised structure.

Proton H-9 is located at one of the one-carbon bridges of the bicyclo[2.1.1]hexane core of 1b. The chemical shift of its signal around δ 2.9230 ppm is at the higher end of what is expected for a methine hydrogen on a carbon adjacent to a ketone. Curiously, this signal appears to be a singlet even though it has 3J relationships with H-2 and H-10, both of which are also on the cyclobutane ring. The unobservable (calculated at 0.074 Hz) 3JH-9,H-10 coupling constant must be attributed again to a nearly 90° dihedral angle. In the original aquatolide structure, proton H-9 was also placed at a three bond distance from H-10, but no explanation was offered for the existence of the small coupling constant.

H-10 is on the opposite bridgehead carbon from H-2 of the bicyclo[2.1.1]hexane core. It is reported as a dd resonance at δ 2.6411 ppm in both the original publication and the revision article.

Resolving Overlapped Aquatolide “Multiplets”

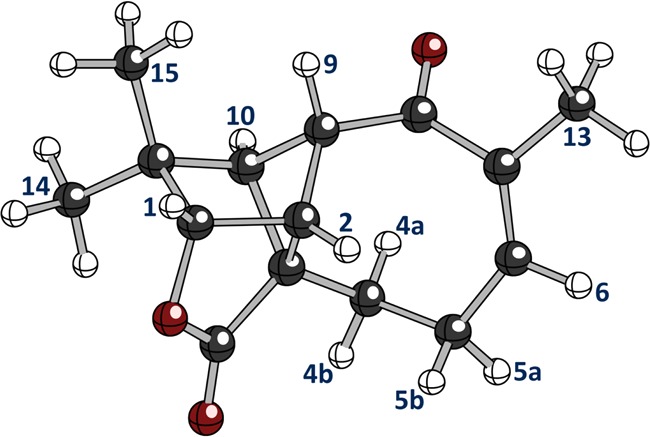

The resonances of the four hydrogens of the two contiguous methylene groups are crowded into the δ 1.84–2.54 ppm interval. Their complex splitting as well as the possible dynamic nature of the ring at these positions tends to obscure the multiplicities and determination of coupling constants. The present study assigns the relative positions of 4a, 4b, 5a, and 5b based on Karplus relationships and unambiguously assigned chemical shift values and reconfirms the assignments through the previously reported NOEs.

H-4a exhibits the most downfield chemical shift of the four methylene hydrogens and has previously been designated as a dd. H-4a is geminally coupled to H-4b with a magnitude of −16.172 Hz. H-4a has a reported 6.7 Hz coupling constant with its 3J H-5b neighbor. On the other hand, the 3JH-4a,H-5a coupling is small and not easily observable; optimized processing revealed the underlying complexity of the signal and allowed determination of 3JH-4a,H-5a as 2.794 Hz. Chemical shifts and coupling patterns are consistent with the position of H-4a pointing into the eight-membered ring in close proximity to the ketone oxygen and H-10. At this position, the dihedral angle between H-4a and H-5a is nearly 90°, and the dihedral angle between H-4a and H-5b approaches 135° with 3JH-4a,H-5b being observed as 6.766 Hz. The position of H-4a is confirmed with NOESY, which shows correlations to both H-10 and H-4b. The resonance is a broad ddd due to an underlying 0.298 Hz 4JH-4a,H-6 coupling.

The signal for H-4b has the most upfield chemical shift of the four methylene hydrogens and is centered at δ 1.9657 ppm. This proton was previously designated as a multiplet. In addition to the 2JH-4a,H-4b coupling of −16.172 Hz, H-4b shows 3J couplings with H-5a and H-5b, which are easily obscured in this complex signal. The small 1.578 Hz coupling may be attributed to 3JH-4b,H-5a, whereas the large 3JH-4b,H-5b coupling was determined as 11.763 Hz.

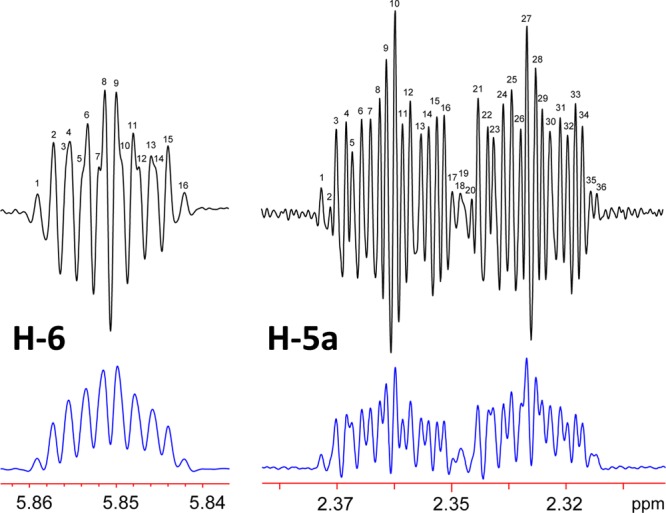

Proton H-5a signal resonates between H-4a and H-5b and has also previously been designated as a multiplet. Upon closer examination, however, this signal appears as a very complex but clearly defined ddddq, as seen in Figure 5. There is a possible total of 64 individual peaks, but overlap considerations bring it down to 36 discernible lines. The reason that this signal exhibits sharper lines than H-5b, H-4a, and H-4b may be related to the fact that the C-5 to H-5a σ bond is aligned with the neighboring sp2 orbitals at C-6. The sp3 hybridized orbitals of H-5a and the C-5 bond are aligned or nearly aligned with the π orbitals of the C-6 to C-7 double bond, imparting the orientation of the C–H bond. Possible dynamic movement of the C-5–C-6–C-7 carbon array, which produces four major conformations (see pages S36 ff. of ref (2)), lead to a specific (T, Bo, c) and characteristic time-averaged spin coupling pattern, especially for the protons at C-5. This portion of the aquatolide molecule is the only substructural fragment that is likely to give rise to dynamic movement, the rest of the molecule being fairly rigid. However, because of the allylic orientational effect, a slight barrier may exist, thus favoring only one of the conformations with aquatolide then being rendered semirigid. A study involving a structural arrangement similar to the present case (6- vs 8-membered ring in aquatolide) was observed for 3-aryl-5r-aryl-6t-carbethoxycyclohex-2-enones.23 The largest coupling constant is attributed to a geminal JH-5a,H-5b coupling (−20.006 Hz), which separates the signal into two almost baseline separated subpatterns. The 3JH-5a,H-4a and 3JH-5a,H-4b couplings have already been described. Protons H-4b, 5a, and 6 appear to orient themselves toward the outside of the 8-membered ring (Figure 6). A 3.208 Hz 3JH-5a,H-6 coupling is also observed, and the observed quartet may be attributed to a 2.142 Hz homoallylic 5JH-5a,H-13 coupling. Homoallylic couplings have been described by Jackman and Sternhell for a number of cases.24 An example that resembles aquatolide exhibits a 1.8 Hz homoallylic coupling reported in a 6-methyl-3,4-dihydro-2H-pyran.25

Figure 5.

Optimizing processing parameters reveal coupling constants and line counts present in the signals for H-5a and H-6 of 1b. Double zero filling was applied to both. The bottom (blue) signals were obtained using a Lorentzian–Gaussian apodization function of LB = −1.4 Hz and GF = 0.17 (17% AQ). The top (black) signals resulted from a Lorentzian–Gaussian apodization function of LB = −2.5 Hz and GF = 0.25 (25% AQ) and demonstrate that all theoretical lines of these complex “multiplets” can indeed be deciphered by manual analysis facilitated by tools such as jVisualizer (http://jvisualizer.sourceforge.net/). Actually, proton H-5a resonates as a ddddq, and H-6 gives rise to a ddq signal.

Figure 6.

Three-dimensional representation of 1b showing the spatial relationships in the 8-membered ring computed with density functional theory.2

Upon closer examination, the H-5b “multiplet” located between the H-5a and H-4b signals is identified as a ddddq. The 3JH-5b,H-6 coupling may be observed as 4.769 Hz. The homoallylic 5JH-5b,H-13 coupling exhibits a similar J coupling value (2.245 Hz) to that of 3JH-5a,H-13.

Protons of the Olefinic Moiety

The signal for the olefinic proton at H-6 has a chemical shift of δ 5.8507 ppm. It was reported as a multiplet in the original publication and as a ddt in the revision article. The 3JH-5a,H-6 and 3JH-5b,H-6 couplings described above are in agreement with previous work on allylic couplings.2 Therefore, the multiplicity of the signal should be accurately represented as a ddq (Figure 5). There are a total of 16 peaks in this signal: ten are readily discernible and six require stronger Lorentzian–Gaussian resolution enhancement to be discernible.

The olefinic methyl group, H-13, with a signal centered at 1.8698 ppm, was reported as a multiplet in the original publication and as a quartet in the revision article. As the H-13 protons are coupled to H-5a, H-5b, and H-6, with J couplings of 2.142, 2.245, and 1.546 Hz, respectively, it should be described as a ddd.

Both methyl groups on the gem dimethyl moiety are reported as singlets in the original publication and in the revision article. The methyl group that is closest to the lactone (Figure 6) is designated as C-14, whose hydrogens have a 1H chemical shift of δ 1.0544 ppm. The methyl group that is closest to H-9 is designated as C-15 with hydrogens at δ 1.1941 ppm. This orientation is revealed in the NOESY spectrum, which shows the protons at δ 1.1941 ppm correlated strongly with H-9 and more moderately with H-1, H-10, and H-14.

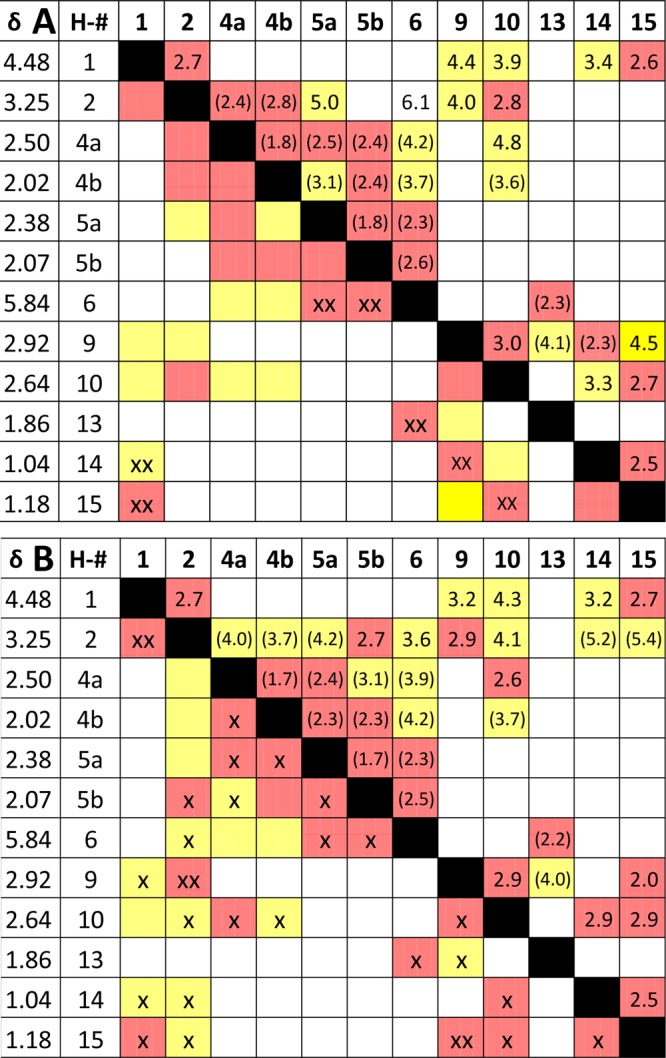

Visualizing 2D NMR Data with QuILTS: NOE Correlations

The QuILT concept, introduced above for 1D HNMR, can be employed to represent the entirety of a complex 2D NMR cross-peak map into a more straightforward graphical format. In the case of aquatolide, the NOESY correlations are essential to confirm and/or determine key structural elements. As shown in the corresponding correlation map (original NOESY QuILT, Figure 7A), plotting internuclear distances on the upper diagonal relative to cross peaks on the lower diagonal, the NOESY approach may be a hit-or-miss situation. Expected NOESY correlations may or may not be observed with a given set of acquisition and processing parameters. Of particular concern with the structure determination of aquatolide in the original article is the apparent lack of correlations for the crucial H-1, H-2, H-9, and H-10 protons, such as H-2 to H-10 (Figure 7A). Without these correlations, it is difficult to confirm the original structure. The revision article described a much more complete family of NOESY correlations (revised NOESY QuILT, Figure 7B), especially between the four key protons of the bicyclo[2.1.1]hexane core, such a H-2 to H-9. However, there are still some areas left for consideration. An apparent cross peak between H-2 and H-10 seems to favor the original structure over the revised structure. This is likely due to the presence of an antiphase cross peak, or COSY cross peak, resulting from a coherence transfer between J-coupled spins.26

Figure 7.

NOESY correlation maps (NOESY QuILTs) of the original (A) and the revised (B) structures (δ precision as reported). The upper right halves contain the distances between nuclei taken from the revision article and a 3D model (in parentheses). Red color indicates distances <3.0 Å. Yellow boxes are distances between 3.0 and 5.0 Å. Boxes without color represent distances >5.0 Å. The bottom left halves are actual NOESY cross peaks observed as either strong (xx) or weak (x) correlations. Distances without parentheses were taken from the revision article, and those in parentheses were determined with Avogadro molecule editor and visualizer.

A detailed analysis of the revised NOESY QuILT (Figure 7B) shows that H-1 correlates with H-2, H-9, H-14, and H-15. H-2 correlates strongly with both H-1 and H-9 while being more moderately correlated with H-5b, H-6, H-10, H-14, and H-15. The NOESY spectrum of H-9 shows a strong correlation to the H-2 and H-15 methyl protons and weaker correlations to H-1, H-13, and H-10. H-10 shows correlations to H-2, H-4a, H-4b, H-9, H-14, and H-15. The position of H-4a relative to H-4b is also supported by the NOESY spectrum as H-4a correlates to H-4b, H-5a, H-5b, and H-10. In turn, H-4b is correlated to H-4a, H-5a, and H-10. H-5a shows NOE contacts to H-4a, H-4b, H-5b, and H-6. The position of H-5b relative to H-5a is supported by NOESY correlations to H-2, H-4a, H-5a, and H-6. The latter shows a correlation with the H-13 methyl protons, which in turn exhibit a correlation with H-6 and H-9. As previously described, the relative orientation of the C-14 and C-15 methyl groups relies on the NOESY data.

QuILT Representation of the 2D NMR Workhorse HMBC

The HMBC experiment is a powerful method to confirm or predict structural connectivity features via long-range heteronuclear coupling (≥2JC,H). Heteronuclear correlations play an important role in the overall structural determination, but there are some important limitations. A survey of marine natural product revisions suggested that a significant number of misassigned structures are associated with interpretation of the HMBC data.27 This was primarily due to the incomplete nature of the experimentally observed HMBC correlations. This situation can be clearly seen, in the case of aquatolide, with the HMBC QuILT shown in Figure 8, which by nature is asymmetric. In the original publication, 9 of 24 2JC,H and 19 of 42 3JC,H possible correlations were observed. In the revision publication, 13 of 24 2JC,H and 37 of 45 3JC,H possible correlations were observed. From these examples, it may be proposed that, at best, HMBC data may be used to favor one set of possible structures rather than actually proving one structure.

Figure 8.

Long-range heteronuclear QuILTs summarize both the observed direct (1JC,H) and ≥2JC,H correlations in the original (A; HETCOR and long-range HETCOR, respectively) vs revised (B; HSQC and HMBC, respectively) aquatolide structures. The numbers inside the δ and atom number grid reflect the number, n, of connecting bonds (nJ). Bolded numbers represent observed correlations. Color coding of boxes: black = one bond, violet = two bonds, blue = three bonds; white = four and more bonds. Color coding of numbers: black and white = 1JC,H correlation; gray ≥2JC,H correlations.

Similar to all NMR techniques, both the acquisition and processing parameters play a substantial role in what correlations may be observed or not observed. For example, the absence of key 3J HMBC correlations, which will exhibit variation according to the 3-bond Karplus relationship between the 1H and 13C, may be a result of the experimentally acquired data falling outside of the coupling constant range in the standard HMBC experiment, which is typically optimized for 3JC,H = 7.0–8.5 Hz for 1H, 13C dihedral angles of 180°. It is frequently necessary to perform two or three HMBC experiments optimized for smaller J-couplings (3JC,H = 4.0–6.0 Hz) and/or extend the number of increments of the evolution time to reveal the smaller couplings that occur later in the evolution time. To reveal the maximum number of correlations, other experiments may be used for extracting couplings over 3–5 bonds, e.g., LR-HSQMBC.28 Heteronuclear correlation experiments do not typically reveal if an observed cross peak represents a 2-, 3-, or even 4-bond coupling. Fully and correctly assigning all protons and, thus, all protonated carbons would serve to reduce this ambiguity considerably.

The heteronuclear QuILTs from the original aquatolide publication data (Figure 8A) shows that all of the observable cross peaks in the long-range HETCOR experiment may be attributed to 2JC,H and 3JC,H correlations. Although this was congruent with the original structure, the incompleteness of the correlation map (a well-known downside of the long-range variant of the HETCOR experiment29) was consistent with other possible structures as well. An HMBC 2D experiment in the revision article identified several key relationships (HMBC QuILT, Figure 8B), but this set alone could not definitively favor the revised structure over the original one and required additional evidence. Notably, there are seven instances where a JC,H coupling is 3JC,H for the revised structure and would be 4JC,H for the original. The five correlations that are identifiable as cross peaks in HMBC are C-1 to H-9, C-4 to H-10, C-8 to H-2, C-10 to H-4a, and C-10 to H-4b. However, two 3JC,H couplings are not evident: C-9 to H-1 and C-12 to H-10. Conversely, there are five instances where observed JC,H couplings are 4JC,H for the revised structure that would be 3JC,H for the original structure. Accordingly, in line with the revision, four of them are not seen as HMBC cross peaks (C-4 to H-9, C-5 to H-13, C-9 to H-4a, and C-9 to H-4b), whereas one is indeed observed: C-12 to H-9. Although these provide a strong argument for the revised structure over the original, these results are not overwhelmingly conclusive. In particular, the only 4JC,H coupling observed for the revised structure must be addressed. The geometry of the correlating moiety has a characteristic “W” arrangement that would allow the back lobes of sp3 orbitals on C-3 and C-9 to overlap, thus providing a mechanism for the transmission of the observed spin coupling effects.

HiFSA of Synthetic Aquatolide Provides Independent Confirmation

While this manuscript was under preparation, the group of HH published the total synthesis of aquatolide.30 Sharing of the 400 MHz 1H NMR spectrum FID of this publication and a 1.1 mg sample of the compound, which was used to acquire a 900 MHz data set, permitted both a rapid verification of the result of this work and the mutual congruence of the structural assignments. For this purpose, the HiFSA profiles of the 400 and 900 MHz data of the synthetic sample were generated and compared with the profile obtained from the 800 MHz of the natural material. The results (Table 1) reveal the expected high consistency of all three profiles and also confirm the reported scaling capability of HiFSA.9 Furthermore, in line with the interpretation of the dynamic effects that broaden the signals of H-4a, H-4b, and H-5a of the 8-membered ring (see above), the small but significant differences observed for the couplings of these protons reflect the impact of the magnetic field strength on the peak separation, leading to greater line broadening due to incomplete averaging as well as the slight experimental differences of the two measurements (temperature and concentration). Accordingly, the minor deviations in the J-patterns actually confirm the inferences regarding the peak broadening effects.

Table 1. Comparison of the HiFSA Profiles of Natural (1b-800 = 800 MHz Data from ref (2)) vs Synthetic Aquatolide (1b-400 = 400 MHz from ref (30) and 1b-900 = 900 MHz of Sample Originating from ref (30)) Shows the Close Congruence of the Spin Systems in the Coupling Constants (A), Chemical Shifts (B), and Line Widths of the Resonances (C), Confirming the Identity of the Samplesa.

| A | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| J (Hz) | 1b-800 | 1b-400 | 1b-900 |

| H10A–H14B | –0.25 | –0.62 | –0.20 |

| H10A–H15B | –0.13 | –0.51 | –0.12 |

| H10A–H1A | 1.85 | 1.90 | 1.82 |

| H10A–H2A | 7.22 | 7.21 | 7.22 |

| H10A–H9A | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.15 |

| H13B–H5A | 2.22 | 2.13 | 2.19 |

| H13B–H5B | 2.17 | 2.11 | 2.16 |

| H13B–H6A | –1.56 | 1.59 | 1.55 |

| H1A–H2A | 2.50 | 2.48 | 2.50 |

| H1A–H9A | –0.39 | –0.08 | –0.40 |

| H2A–H4A | –0.35 | –0.04 | –0.41 |

| H2A–H4B | –0.26 | –0.03 | –0.22 |

| H2A–H9A | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.37 |

| H4A–H4B | –16.20 | –16.20 | –16.20 |

| H4A–H5A | 3.03 | 1.92 | 2.48 |

| H4A–H5B | 6.77 | 6.81 | 6.80 |

| H4A–H6A | 0.96 | 0.95 | 1.00 |

| H4B–H5A | 11.7 | 12.1 | 12.3 |

| H4B–H5B | 1.60 | 1.60 | 1.62 |

| H4B–H6A | –0.09 | 0.00 | –0.34 |

| H5A–H5B | –20.00 | –19.90 | –20.00 |

| H5A–H6A | 3.26 | 3.19 | 3.25 |

| H5B–H6A | 4.76 | 4.64 | 4.72 |

| B | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| δ (ppm) | 1b-800 | 1b-400 | 1b-900 |

| H10A | 2.641 | 2.641 | 2.641 |

| H13B | 1.870 | 1.872 | 1.871 |

| H14B | 1.054 | 1.057 | 1.056 |

| H15B | 1.194 | 1.195 | 1.195 |

| H1A | 4.480 | 4.478 | 4.479 |

| H2A | 3.260 | 3.259 | 3.260 |

| H4A | 2.516 | 2.518 | 2.518 |

| H4B | 1.966 | 1.970 | 1.969 |

| H5A | 2.023 | 2.025 | 2.025 |

| H5B | 2.348 | 2.349 | 2.349 |

| H6A | 5.851 | 5.852 | 5.851 |

| H9A | 2.923 | 2.923 | 2.923 |

| C | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| LW (Hz) | 1b-800 | 1b-400 | 1b-900 |

| H10A | 0.13 | 1.19 | 0.62 |

| H13B | 0.26 | 1.73 | 0.44 |

| H14B | 0.70 | 1.90 | 0.83 |

| H15B | 0.57 | 1.88 | 0.74 |

| H1A | 0.33 | 1.82 | 0.33 |

| H2A | 0.58 | 1.77 | 0.70 |

| H4A | 3.53 | 2.82 | 3.53 |

| H4B | 4.49 | 2.54 | 4.49 |

| H5A | 2.48 | 2.25 | 2.48 |

| H5B | 0.50 | 1.82 | 0.73 |

| H6A | 0.61 | 1.91 | 0.66 |

| H9A | 0.45 | 1.81 | 0.63 |

The small but diagnostic differences in the J values and increased signal widths of H-4A, H-4B, and H-5B reflect the field-dependent dynamic of the 8-membered ring system (see main text).

Overall, we learn from this comparison that dynamic effects play enough of a role in HiFSA profiles such that they have subtle but characteristic effects on the determined coupling constants in complex signals. When interpreting these subtle effects, one has to keep in mind that the observed coupling constants represent weighted averages of the coupling constants of all conformers. Therefore, dynamic effects influence coupling constants as determined by HiFSA and include temperature, field strength, and sample concentration. Furthermore, line distances in 1H NMR spectra are not coupling constants, unless the spin system is pure first order, which is rarely truly the case and is certainly not the case in aquatolide. Representing an iterative method, HiFSA determines the “experimental” coupling constants, but the underlying NMR experiment, detects conformationally averaged coupling on the (slow) NMR time scale. As a result, unless all populations and their abundance are known, the “true” underlying J values cannot be determined.

Conclusions

Understanding the reasons for misassignment is as important as correcting structures. The following points summarize key lessons to be learned, or reminded of, from the aquatolide case.

Point 1: 1D 1H NMR Data is Indispensable

The proper acquisition and accurate interpretation of 1D 1H data (the “mother of all NMR spectra”) is a crucial first step in structure elucidation. Especially for the purpose of obtaining preliminary structural information, 1H spectra will usually be the first 1D spectra acquired, and this choice is largely driven by sensitivity, due to the limited levels of material frequently encountered early in an isolation protocol. Subsequent 1D and 2D experiments will expand on and/or confirm the 1D 1H data. Although the 1D 13C data is particularly important to elucidate proton-deficient molecules, NMR spectra of both nuclei are important for subsequent structural dereplication. The importance of 1D 1H data should be respected, beginning with acquisition of the data, and followed through with the appropriate post-acquisition processing. In particular, Lorentzian–Gaussian or other resolution enhancement post-acquisition processing, including zero-filling, can be used to observe the greater details of coupling patterns present in complex signals. However, it must be conceded that even meticulous processing may not reveal all of the signal information and, therefore, coupling information due to signal overlap, exceedingly small coupling values, and signal-to-noise issues, may still make extraction of all of the spectral information problematic.

In this context, it should be noted that standard 1H NMR spectra acquired under quantitative conditions are entirely fit for the purpose of qHNMR quantitation, allowing for the assessment of the purity of the investigated compounds. As qHNMR spectra need to be acquired with good signal-to-noise (S/N), they elegantly serve the dual purpose10 of enabling recognition of splitting/coupling patterns through resolution-enhanced post-acquisition processing and LC-independent purity assessment as required by journals.10

Point 2: Protons and Carbons are Indicators of Backbone Geometry

Computational evaluation of structures using both 1H and 13C data, together with the calculation of Δδ values, is the first tier in the evaluation of a proposed structure. Prediction of coupling constants based on the optimized geometry of the proposed structure is the second tier of 1H spectra evaluation. Finally, the observed coupling information may be further enhanced with iterative fitting processes utilizing the quantum mechanical spin information inherent in the structural geometry in a third tier of evaluation. Although HiFSA may ultimately reveal inconsistencies in a proposed structure, a careful analysis of the HiFSA parameters must still be undertaken even in the case of a good fit.

Primarily, the evaluated 3J coupling constants should be consistent with the dihedral angles present in the proposed 3D molecular structure. Of particular concern are instances of unobservable 3J coupling constants due to dihedral angles near 90°: the lack of measurable coupling differs significantly from missing J values in reported tables or QuILTs. Therefore, it is a necessary requirement to verify both what is observed and what is not observed. It is difficult to know from the literature how often unobservable 3J couplings occur in structural elucidation: as “unobservables”, they cannot be observed and thus are not reported, but so are many other obvious couplings.

Whereas the computation of average and maximum 13C chemical shift deviations is an accepted means of assessing the plausibility of (revised) structures,31 the accuracy of available 1H chemical shift prediction tools is not yet sufficient to establish analogue measures for 1H-based computer-aided structure elucidation (CASE; http://www.acdlabs.com/comm/elucidation/2013_10.php). However, precise and accurate reporting of 1H NMR data (see ref (16) and below) is an important and powerful instrument of both dereplication and structure elucidation.

Point 3: 1D 1H NMR Data is Information-Rich

The simplicity of the 1D 1H NMR experiment has a tendency to hide the information richness of the spectra. In fact, with the exception of proton-deficient compounds, the assortment of multibond couplings (2–7J) that encodes the network of proton resonances of a given molecule provides plentiful structural information, and all of them have to be compatible with the proposed structure. A generally useful approach is to challenge “multiplets” as particularly information-rich signals. One efficient means of mining this information is to perform full spin analysis (HiFSA), which captures the 1H spin network assignments in a QM-proof manner. Spin simulation software, required for this purpose, has been available since the 1960s (LAOCOON), and modern tools are more powerful than ever. It is important to note that the assignment of all chemical shifts and couplings requires spectral simulation to account for non-first-order effects, which are frequently observed even with “simple” molecules and at high magnetic field strengths.

Part of the realization of the information richness is the consideration of long-range couplings as both a subtlety to be explored and a great resource for structural information. The occurrence of long-range couplings indicates particular and sometimes unique structural characteristics. For example, in the aquatolide case, allylic 4J, homoallylic 5J, and strained ring 4J “twofold W” couplings were observed. Although long-range couplings might be viewed as minor and “esoteric”, they can impart important and valuable constraints as to the plausibility of a particular structure.

Point 4: 2D NMR Supports but does not Replace 1D NMR

Because of the general accessibility of 2D data, 1D NMR experiments have taken a “backseat” in the structure elucidation toolbox. However, it is important to realize that one cannot rely solely on the workhorse 2D NMR spectra (COSY, HSQC, HMBC). The evidence contained in 1D data sets, particularly in the 1H domain involving abundant J coupling, simply cannot be ignored when making conclusions about the structure; all of the data, including the 1D 1H information, has to match. Collectively, 2D NMR experiments can serve to confirm structural assignments, including those made from 1D 1H analyses, but not replace or even “override” them as evidence. Another important reflection resulting from the aquatolide case: although the lack of an HMBC (or any other 2D) cross-peak can be diagnostic, it is predominantly a lack of information. It can be due to either structural constraints or be an artifact of the acquisition parameters. The observation of an unexpected strong HMBC cross-peak is a clear warning sign of a wrong structure. In fact, peak intensities and JC,H coupling values play an important role in the correct interpretation of HMBC and other 2D NMR experiments that involve J coupling mechanisms.

Point 5: FID Archives

Proper preservation and dissemination of experimental FIDs in electronic format is an important aspect of any structural elucidation process. This conforms to the principle of the dissemination of scientific research results. Adequate information must be supplied in order that research results may be reproduced. The availability of FIDs permits a comparison of the NMR data for published structures with NMR data for newly acquired compounds either by isolation or by synthesis for facilitating dereplication and identifying novel structures.

Dereplication based solely on typically published 1H chemical shift and multiplicity tables is insufficient. Even if high resolution spectra (images) are included in the Supporting Information of a publication, the opportunity for accurate dereplication cannot be achieved. Therefore, the original FIDs in electronic format should be supplied as part of the dissemination of published work.

Point 6: Free Databases

The compilation and maintenance of databases, such as the crystallography open database,32 is a worthwhile contribution to the field of structure elucidation. Fledgling NMR FID databases have emerged,33,34 but a concerted effort by both journal editors and publication authors to participate is overdue. One unresolved but important aspect is the status of the distributed information. Most desirable for scientific purposes are Free Archives which, similar to Free Software, are not just freely accessed, but also associated with distribution rights that establish the freedom to use the data portion of an ongoing evolutionary process and methodology improvement with reference to the original authors.

Point 7: Dereplication Requires Reproducibility of Chemistry as a Central Science

The consistency of structure elucidation reports and their efficient dissemination has broad implications not only for accurate publication of chemical structures but also for exploitation of these structures for their biological, pharmaceutical, and environmental applications. In the current situation, as described in the Introduction, much research has been expended for the synthesis of molecules exhibiting interesting biological activities, only to find that the structures originally reported were incorrect.8,35 The reproducibility of new structures and related discoveries rests on the ability of future researchers to dereplicate the structure and possibly reassess the sample, or at least its 1H NMR spectrum. The HiFSA-based dereplication of synthetic relative to isolated aquatolide presented in the section “HiFSA of Synthetic Aquatolide” exemplifies the efficiency of the approach.

Dereplication and reproducibility are two sides of the same coin. Near-identical (but not really identical!) chemical properties are the breeding ground for wrong assignments, misidentification, synthetic chemistry misdirection, and wasted time and resources, leading to long-lasting confusion in upstream and downstream research. Concerning 1H NMR, subtleties drive dereplication. In fact, attention to detail can turn standard 1D 1H NMR into a powerful dereplication tool. This applies particularly to natural products, as their combinatorial, biosynthetic origin makes the existence of very close or near-identical congeners with partial stereochemical variations very likely. At the same time, 1D 13C NMR represents a complementary approach to dereplication that is readily automated due to the simplistic pure shift nature of 1H broad-band decoupled 13C spectra.

There are numerous cases of natural products that represent near-identical molecules, which are highly likely to produce near-identical NMR spectra (e.g., the [iso-]silybins),13 but are also likely associated with distinct biological properties and/or taxonomic sources, and sometimes new chemical structures (e.g., leubethanol from the plant Leucophyllum frutescens vs elisabethanol from the gorgonian octacoral Pseudopterogorgia elisabethae).36 Even when congeneric molecules are not near-identical themselves, but only with regard to their (highly similar) 1H NMR spectra, the comprehensive 1H NMR analysis is well-suited to produce compelling structural evidence as well as highly specific data for structural dereplication and reproducibility (see below). One example of a new chemical structure investigated using this approach is the new antituberculosis drug lead ecumicin.37 Finally, it is important to point out that chemical shifts exhibit solvent dependence; therefore, this is another significant consideration in NMR-based dereplication.

Best Practices Enhance Reproducibility

From a conceptual perspective, successful dereplication requires unideterminant structural parameters. HiFSA profiles can be considered as one unideterminant data set for a given structure and provides a potential substitute for the mixed melting point determination representing the gold standard for chemical identity, especially if the second cannot be determined due to practical/sample limitations. Consequently, the following tenets are simple ways to enhance reproducibility by means of best practices in NMR-based structural analysis: (i) assign all protons (and carbons) and all couplings; (ii) report chemical shifts (δ) precisely to three or even better four decimal places (≤1 ppb); (iii) report coupling constants (J) precisely to one or even better two decimals (≤100 mHz); (iv) perform full spin analysis (e.g., HiFSA) and report complete sets of 1H spin parameters, e.g., as supporting text or vendor-specific but open formats, such as PERCH PMS files; and (v) make raw NMR data (FIDs) publically accessible and part of publications.

Certainly, there are additional best practices related to the acquisition of 1H NMR spectra, which will in turn enhance the reliability and reproducibility of interpretation. These best practices include (i) the habit of depleting dissolved oxygen in the sample (freeze–pump–thaw or He degassing) and (ii) being cognizant of how solvents affect the acquisition and characteristics of 1H NMR spectra. For example, the chloroform deuterium signal may be difficult to lock at high fields;38 thus, solvent effects on line shape (viscosity) and shimming (split fields) should also be considered.

Documentation and Completeness of Structural Evidence

The QuILTs introduced herein are highly comprehensive representations of NMR structural evidence. The QuILT format is more intuitive for human use than the ubiquitous tabular or graphical formats used in the laboratory and in publications today. In particular, QuILTs simplify the assessment of the completeness of the NMR structural information, as empty boxes are spotted readily and represent the only allowed gaps, indicating a lack of correlation that is in line with the proposed structure.

Moreover, QuILTs are flexible in accommodating the most common NMR experiments: 1D 1H (1H J-QuILT in Figure 3), homonuclear (e.g., NOESY QuILT in Figure 7; can be expanded to, e.g., TOCSY), and heteronuclear (e.g., HMBC QuILT in Figure 8; can be expanded to HSQC as diagonal) spectra can all be transposed in the QuILT format.

Finally, the QuILT format can be readily standardized and provide NMR data in a machine readable, unified format, making it an ideal reporting format for computational processing. Potential downstream applications of data published in QuILT format include, but are not limited to, spectroscopic databases, dereplication, and computer-assisted structure elucidation tools.

Limitations of Evidence in Structure Elucidation

Collectively, all above points reflect on the generally well-known but sometimes forgotten fact that spectroscopic structure elucidation is based on indirect rather than direct evidence and is the product of deductive reasoning rather than a “picture” of the molecule. As a result, spectroscopic evidence is intrinsically limited, and respecting this limitation is key to sound structure elucidation. The imperative of always considering alternative structures is one valuable means of addressing this challenge. Another is to distinguish the difference between the terms “proof” and “consistent with” in structure elucidation documents. The case of aquatolide exemplifies some of the pitfalls, but also new insights, that can be gained from adhering to these principles as closely as possible.

Experimental Section

NMR Spectroscopy

The NMR measurements were described previously for the natural aquatolide (800 MHz)2 and the synthetic material (400 MHz).30 A sample of unnatural (−)-aquatolide (1.1 mg in 0.7 mL CDCl3) was also subject to 900 MHz NMR analysis. For reprocessing of the 1H FID, the chemical shift of the residual solvent signals, CHCl3, at δH 7.2600 was used as the chemical shift reference. The 800 MHz data for Figure 3A and Figure 5A were processed using Lorentzian–Gaussian apodization functions with LB values of −1.0 to −3.0 Hz and Gaussian factors of 0.10–0.30, centering the Gaussian function at 10–30% of the acquisition time. For HiFSA, reprocessing using a mild Lorentzian–Gaussian window function (line broadening = −0.3, Gaussian factor = 0.05) prior to two zero fills to 256 K and Fourier transformation.

Computer-Aided NMR Spectral Analysis

The 1H iterative full spin analysis (HiFSA) was performed by PERCH NMR software package (ver. 2013.1) as described previously.9,39 The optimized spectral parameters were saved as PERCH parameter text files (*.pms). Four and two decimal places for δH and J values, respectively, were considered significant. The measurements of interatomic distances were performed with the free software Avogadro (http://avogadro.openmolecules.net) v1.1.140 using the MOL files exported by PERCH.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Laura Gauthier, UIC, for creative input and to Dr. Holger Schimanski, Bayer HealthCare, Leverkusen (Germany), for providing jVisualizer published under the GNU General Public License v2. We are also grateful to one anonymous reviewer for very helpful practical considerations and relevant references regarding 1H NMR and nD NMR-based structure elucidation in general. This work received support from Grant U41 AT008706 from the NIH (NCCIH and ODS). The construction of the UIC CSB and the purchase of the 900 MHz NMR spectrometer was generously funded by Grant P41 GM068944 to Dr. Peter Gettins from NIGMS.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b02456.

M.N. is founder of Perch Solutions Limited. The other authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- San Feliciano A.; Medarde M.; Miguel del Corral J. M.; Aramburu A.; Gordaliza M.; Barrero A. F. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989, 30, 2851–2854. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)99142-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lodewyk M. W.; Soldi C.; Jones P. B.; Olmstead M. M.; Rita J.; Shaw J. T.; Tantillo D. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 18550–18553. 10.1021/ja3089394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seetharamsingh B.; Rajamohanan P. R.; Reddy D. S. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 1652–1655. 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terayama N.; Yasui E.; Mizukami M.; Miyashita M.; Nagumo S. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 2794–2797. 10.1021/ol5006856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Q.; Young K.; Zakarian A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 5907–5910. 10.1021/jacs.5b03531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong X.; Li Y.; Zhang J.; Han F. S. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 720–723. 10.1021/ol503734x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L. Y.; Tong R. B. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 1966–1969. 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaou K. C.; Snyder S. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 1012–1044. 10.1002/anie.200460864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napolitano J. G.; Lankin D. C.; McAlpine J. B.; Niemitz M.; Korhonen S.-P.; Chen S.-N.; Pauli G. F. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 9963–9968. 10.1021/jo4011624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauli G. F.; Chen S.-N.; Simmler C.; Lankin D. C.; Gödecke T.; Jaki B. U.; Friesen J. B.; McAlpine J. B.; Napolitano J. G. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 9220–9231. 10.1021/jm500734a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodewyk M. W.; Siebert M. R.; Tantillo D. J. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 1839–1862. 10.1021/cr200106v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain R.; Bally T.; Rablen P. R. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 4017–4023. 10.1021/jo900482q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napolitano J. G.; Lankin D. C.; Graf T. N.; Friesen J. B.; Chen S.-N.; McAlpine J. B.; Oberlies N. H.; Pauli G. F. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 2827–2839. 10.1021/jo302720h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam J.-W.; Phansalkar R.; Lankin D. C.; Bisson J.; McAlpine J. B.; Leme A.; Vidal C.; Ramirez B.; Niemitz M.; Bedran-Russo A.; Chen S.-N.; Pauli G. F. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 7495–7507. 10.1021/acs.joc.5b01082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bally T.; Rablen P. R. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 4818–4830. 10.1021/jo200513q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauli G. F.; Chen S.-N.; Lankin D. C.; Bisson J.; Case R.; Chadwick L. R. d.; Gödecke T.; Inui T.; Krunic A.; Jaki B. U.; McAlpine J. B.; Mo S.; Napolitano J. G.; Orjala J.; Lehtivarjo J.; Korhonen S.-P.; Niemitz M. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 1473–1487. 10.1021/np5002384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutcliffe L. H.; Walker S. M. J. Phys. Chem. 1967, 71, 1555–1557. 10.1021/j100865a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiberg K. B.; Connor D. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1966, 88, 4437–4441. 10.1021/ja00971a025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan R.; Sonntag F. I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967, 89, 407–410. 10.1021/ja00978a042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham R. J.; Cooper M. A.; Salmon J. R.; Whittaker D. Org. Magn. Reson. 1972, 4, 489–507. 10.1002/mrc.1270040409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barfield M.; Chakrabarti B. Chem. Rev. 1969, 69, 757–778. 10.1021/cr60262a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gamba A.; Mondelli R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1971, 12, 2133–2135. 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)96801-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuvaraj C.; Pandiarajan K. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2011, 49, 253–257. 10.1002/mrc.2724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackman L. M.; Sternhell S.. Applications of nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy in organic chemistry, 2nd ed.; Pergamon Press: Oxford, NY, 1969; Vol. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Gagnaire D.; Payo-Subiza E. Bull. Soc. Chim. Belg. 1963, 2633. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A.; Wagner G.; Ernst R. R.; Wüthrich K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981, 103, 3654–3658. 10.1021/ja00403a008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suyama T. L.; Gerwick W. H.; McPhail K. L. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011, 19, 6675–6701. 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson R. T.; Buevich A. V.; Martin G. E.; Parella T. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 3887–3894. 10.1021/jo500333u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman R.; Morris G. A. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1978, 684–686. 10.1039/c39780000684. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saya J. M.; Vos K.; Kleinnijenhuis R. A.; van Maarseveen J. H.; Ingemann S.; Hiemstra H. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 3892–3894. 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b01888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robien W. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 2009, 28, 914–922. 10.1016/j.trac.2009.03.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grazulis S.; Daskevic A.; Merkys A.; Chateigner D.; Lutterotti L.; Quiros M.; Serebryanaya N. R.; Moeck P.; Downs R. T.; Le Bail A. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D420–D427. 10.1093/nar/gkr900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalstabakken K. A.; Harned A. M. J. Chem. Educ. 2013, 90, 941–943. 10.1021/ed300787v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig C.; Easton J.; Lodi A.; Tiziani S.; Manzoor S.; Southam A.; Byrne J.; Bishop L.; He S.; Arvanitis T.; Günther U.; Viant M. Metabolomics 2012, 8, 8–18. 10.1007/s11306-011-0347-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Willwacher J.; Heggen B.; Wirtz C.; Thiel W.; Fürstner A. Chem. - Eur. J. 2015, 21, 10416–10430. 10.1002/chem.201501491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Salinas G. M.; Rivas-Galindo V. M.; Said-Fernández S.; Lankin D. C.; Muñoz M. A.; Joseph-Nathan P.; Pauli G. F.; Waksman N. J. Nat. Prod. 2011, 74, 1842–1850. 10.1021/np2000667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao W.; Kim J.-Y.; Chen S.-N.; Cho S.-H.; Choi J.; Jaki B. U.; Jin Y.-Y.; Lankin D. C.; Lee J.-E.; Lee S.-Y.; McAlpine J. B.; Napolitano J. G.; Franzblau S. G.; Suh J.-W.; Pauli G. F. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 6044–6047. 10.1021/ol5026603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Zijl P. C. M. J. Magn. Reson. 1987, 75, 335–344. 10.1016/0022-2364(87)90039-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Napolitano J. G.; Gödecke T.; Rodriguez Brasco M. F.; Jaki B. U.; Chen S.-N.; Lankin D. C.; Pauli G. F. J. Nat. Prod. 2012, 75, 238–248. 10.1021/np200949v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanwell M.; Curtis D.; Lonie D.; Vandermeersch T.; Zurek E.; Hutchison G. J. Cheminf. 2012, 4, 17. 10.1186/1758-2946-4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.