Abstract

Mycobacteria have a unique cell wall, which is rich in drug targets. The cell wall core consists of a peptidoglycan layer, a mycolic acid layer, and an arabinogalactan polysaccharide connecting them. The detailed structure of the cell wall core is largely, although not completely, understood and will be presented. The biosynthetic pathways of all three components reveal significant drug targets that are the basis of present drugs and/or have potential for new drugs. These pathways will be reviewed and include enzymes involved in polyisoprene biosynthesis, soluble arabinogalactan precursor production, arabinogalactan polymerization, fatty acid synthesis, mycolate maturation, and soluble peptidoglycan precursor formation. Information relevant to targeting all these enzymes will be presented in tabular form. Selected enzymes will then be discussed in more detail. It is thus hoped this chapter will aid in the selection of targets for new drugs to combat tuberculosis.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, drug discovery, cell wall, arabinogalactan, mycolic acids, peptidoglycan, drug target

INTRODUCTION

This review is written primarily for scientists versed and interested in drug discovery but not necessarily experts on the M. tuberculosis cell wall. The idea is to put forth the information on the myriad of potential targets (approximately 60 enzymes are noted) and what is known about them so that informed target selection can be performed. We believe this to be timely as new resources are available to academia, such as screening via the NIH roadmap, to attempt to actually develop new drugs and, of course, the need for new tuberculosis (TB) drugs keeps increasing. Much of the meat of this review will be in the form of key tables that highlight every known enzyme involved in M. tuberculosis cell wall biosynthesis. In addition, for some targets, we will comment on their development or potential development as drug discovery targets in somewhat idiosyncratic and anecdotal fashion, based frequently on our own research.

Clearly for a discussion of cell wall biosynthetic targets it is necessary to review both the structure of the cell wall and the pathway by which it is biosynthesized. Hence, both are included in this review as background material for the discussion of targets. Thus the role and context of each enzyme in the tables can be readily established both in terms of its ultimate product and its position in the biosynthetic pathway.

Our goal to identify cell wall biosynthetic enzymes as drug targets necessarily embraces the targeted approach to new anti-bacterials and more specifically anti-tuberculosis drugs. The efficacy of this approach to new anti-bacterials in general has proven disappointing in recent years, and has to some extent called the entire approach into question [1,2,3,4]. In the case of TB drugs the most exciting new drug candidates have not been targeted against any specific enzyme. However, the approach has proven most dramatically valid in the drugs against the human immunodeficiency virus protease in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, and it will only take one or two successes in targeting individual bacterial enzymes to quickly change the current gloom over the targeted approach in bacteria. While we would agree that whole bacterial screening approaches have been inappropriately deemphasized, we would also argue that it is far from time to give up on the targeted approach. Indeed we hope this review stimulates thinking on just which cell wall enzymes can be most effectively targeted.

M. TUBERCULOSIS CELL WALL STRUCTURE

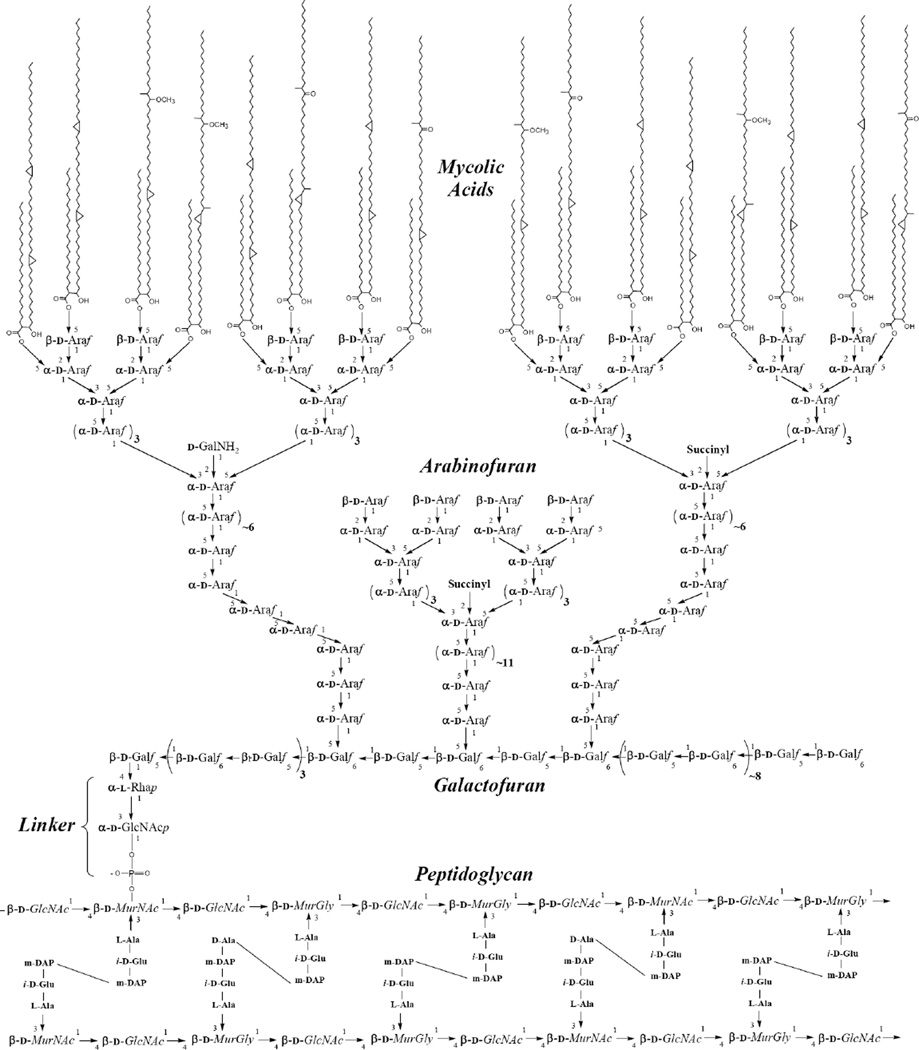

The cell wall of mycobacteria is essential for viability. This cellular envelope consists of a highly impermeable layer of the unique 70–90 carbon mycolic acids covalently attached to the peptidoglycan (PG) layer by way of the connecting polysaccharide, arabinogalactan (AG) as shown in Fig. (1). This arrangement is largely responsible for the ability of mycobacteria to replicate in the hostile environment of the macrophage, and to resist the action of a large number of chemotherapeutic agents [5,6,7].

Fig 1.

The structure of the mycolyl arabinogalactan peptidoglycan core of M. tuberculosis. The mycolic acids are shown attached to two thirds of the arabinans in an all or nothing fashion but this is not known. It is known that they are attached to 4 neighboring non-reducing end arabinosyl groups rather than 1,2, or 3 [196]. Three arabinan chains per galactan are shown attached according to recent data [12] and the length of the arabinan are according to recent data in the author’s (M.M.) laboratory.

The mycolic acids, as shown in Fig. (1), contain 76–89 carbon atoms and are in essentially 5 different forms as marked on the figure (α, cis keto, trans keto, cis methoxy and trans methoxy). There is evidence that all the various forms are required for pathogenicity of M. tuberculosis [8]. The structure and biogenesis of the mycolates have been reviewed [8,9].

The mycolic acids are attached to arabinosyl residues of AG at position 5 (Fig. (1)). The arrangement of the arabinosyl residues within the arabinan is now essentially known (Fig. (1)). Thus, approximately 30 arabinosyl residues are present as a highly branched polymer, three of which are attached to the galactan [10]. There are specific numbers and linkages of arabinosyl residues coming from each branch point [10,11] as shown in Fig. (1). It has been shown in Corynebacterium glutamicum [12] that the three arabinan chains are attached to the 5-positions of the galactan on the residues shown in Fig. (1), and this arrangement is likely to be present in M. tuberculosis as well. The galactan is a linear polymer of approximately 30 alternating β-1,5 and β-1,6 residues[13] as shown in Fig. (1). The galactan itself is attached to the 4 position of the rhamnosyl residues of a specific linker region (α-l-Rhap-(1→3)-α-β-d-GlcNAc-1-P) which is in turn attached to O-6 of a muramic acid residue in the peptidoglycan. Approximately 10% of the muramic acid residues are substituted with an AG molecule [14].

There are known drugs to each of the three components. Thus isoniazid (INH) a front line drug against tuberculosis, inhibits (among other things) the synthesis of mycolic acids [15]. Ethambutol, another effective therapeutic, inhibits biosynthesis of the arabinan component of arabinogalactan [16]. Finally, although M. tuberculosis is generally considered resistant to β-lactams (due to the impermeability of the mycolate layer [17]), it is susceptible to the peptidoglycan drug cycloserine.

M. TUBERCULOSIS CELL WALL BIOSYNTHETIC PATHWAY

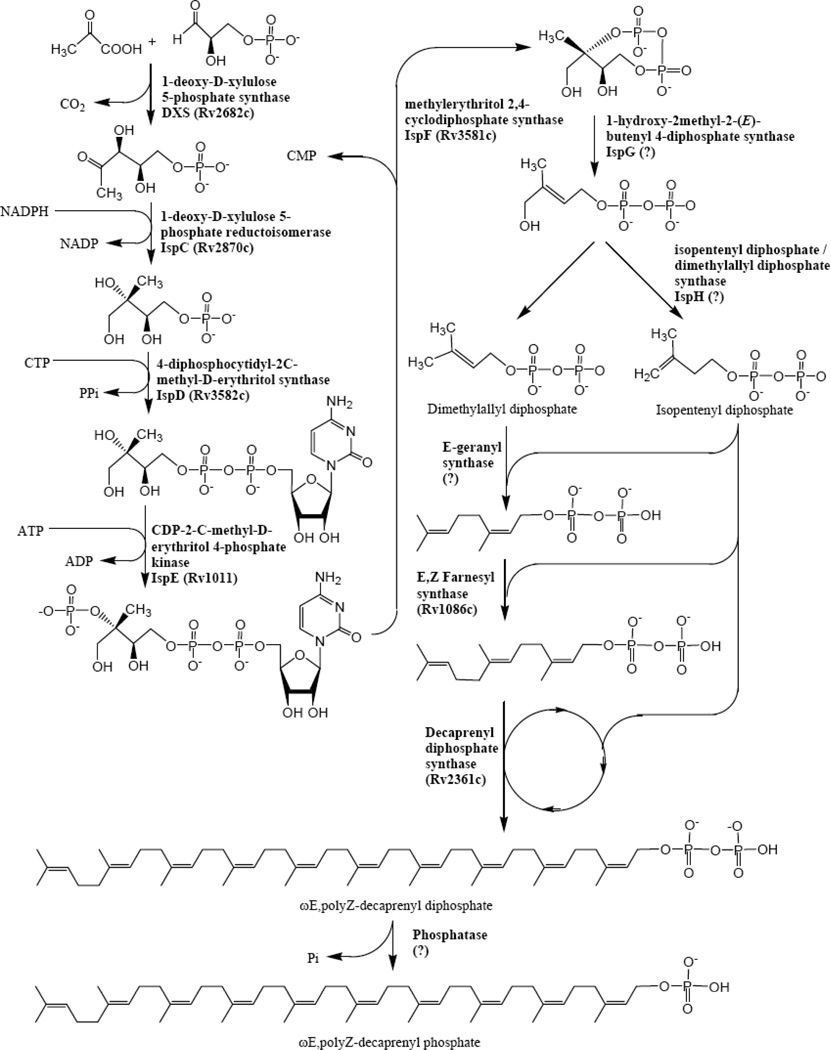

The biosynthetic pathway of the M. tuberculosis cell wall is summarized in four figures (Figs. (2–5)). Firstly, the pathways for the formation necessary donor and carrier molecules are shown. Decaprenyl phosphate is a key carrier molecule for the synthesis of AG [18], PG, and possibly mycolic acids. Its biosynthesis is shown in Fig. (2). The synthesis of decaprenyl phosphate is usefully grouped as pre-polymerization [i.e. the formation of isopentyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP)] and polymerization events leading to decaprenyl phosphate (Fig. (2)). Recent work has identified IPP synthesis as a potentially rich source of drug targets in bacteria. In eukaryotes, IPP is synthesized by condensation of acetyl Coenzyme A (CoA) to form 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl CoA which is reduced to mevalonate, and subsequently, decarboxylated to form the five carbon molecule, IPP [19]. However, a series of studies [20,21,22,23,24,25,26] have clearly shown that some bacteria (but not all) use a different pathway for IPP/DMAPP biosynthesis as shown in Fig. (2). This pathway has widely become known as the MEP pathway as 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) is the first committed precursor in the synthesis of IPP.

Fig 2.

The biosynthesis of decaprenyl phosphate. The pathway can be seen as two parts, with the first part being the formation of the monomers dimethylallyl diphosphate and isopentyl diphosphate, and the second part being the polymerization utilizing those compounds.

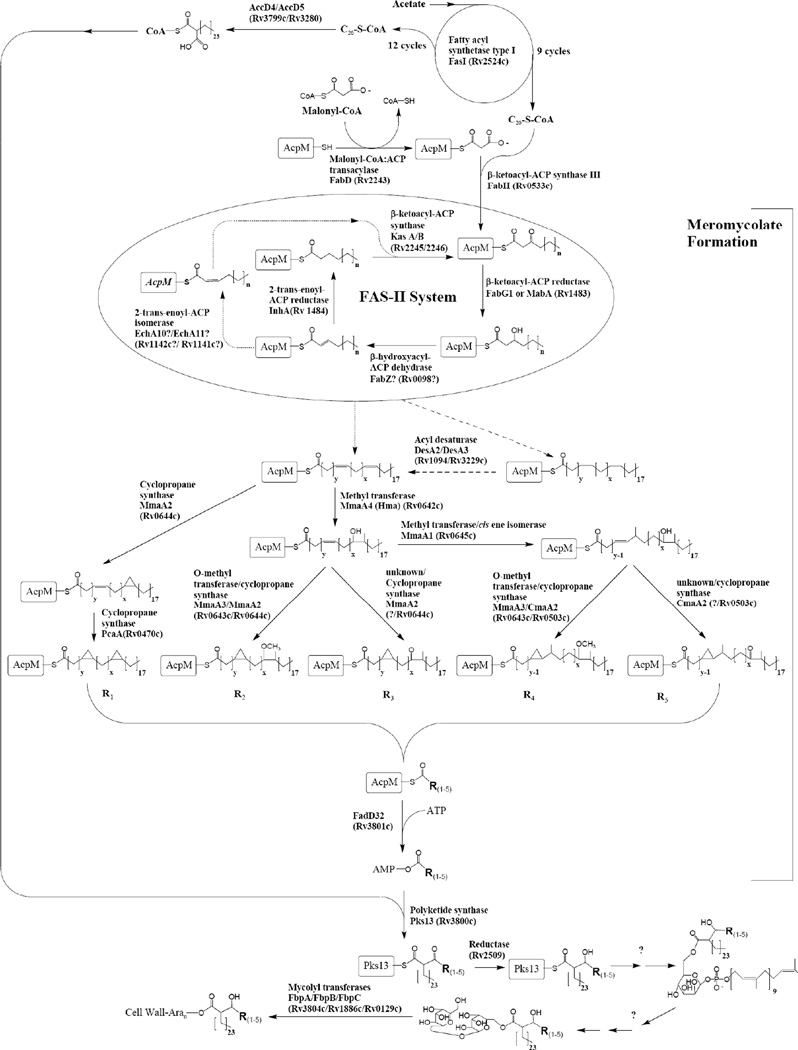

Fig 5.

The biosynthetic pathway of mycolic acids. At the top of the figure the formation of activated C26-CoA is shown, which is one half of the condensation shown at the bottom of the figure. The remainder of the figure is concerned with the formation of the meromycolates. The pathway for the formation of the double bonds in the meromycolates remains unclear and two possibilities are shown. One of these requires isomerization of the normal cis double bond to trans, and the other the use of desaturase enzymes. These two possibilities are shown using dotted lines.

In regards to the polymerization reactions, the polyprenyl phosphate involved in the synthesis of the M. tuberculosis cell-wall core has been identified as decaprenylphosphate (Dec-P) [27,28], which has 50 carbon atoms as opposed to the much more commonly utilized undecaprenyl phosphate. Typically, Z-prenyl diphosphate synthases, which synthesize undecaprenyl diphosphate, utilize E,E-farnesyl diphosphate as the allylic acceptor synthesizing long-chain products with the a common diE, polyZ stereo conformation [29,30,31,32]. M. tuberculosis is unusual in that it has 2 genes (Rv1086 and Rv2361c) encoding proteins with significant sequence similarity to undecaprenyl diphosphate synthase (UPS). Rv1086 encodes an E,Z-farnesyl diphosphate [33,34] and Rv2361c encodes a decaprenyl diphosphate synthase [33,35], that adds seven isoprene units to E,Z-farnesyl diphosphate synthesized by Rv1086.

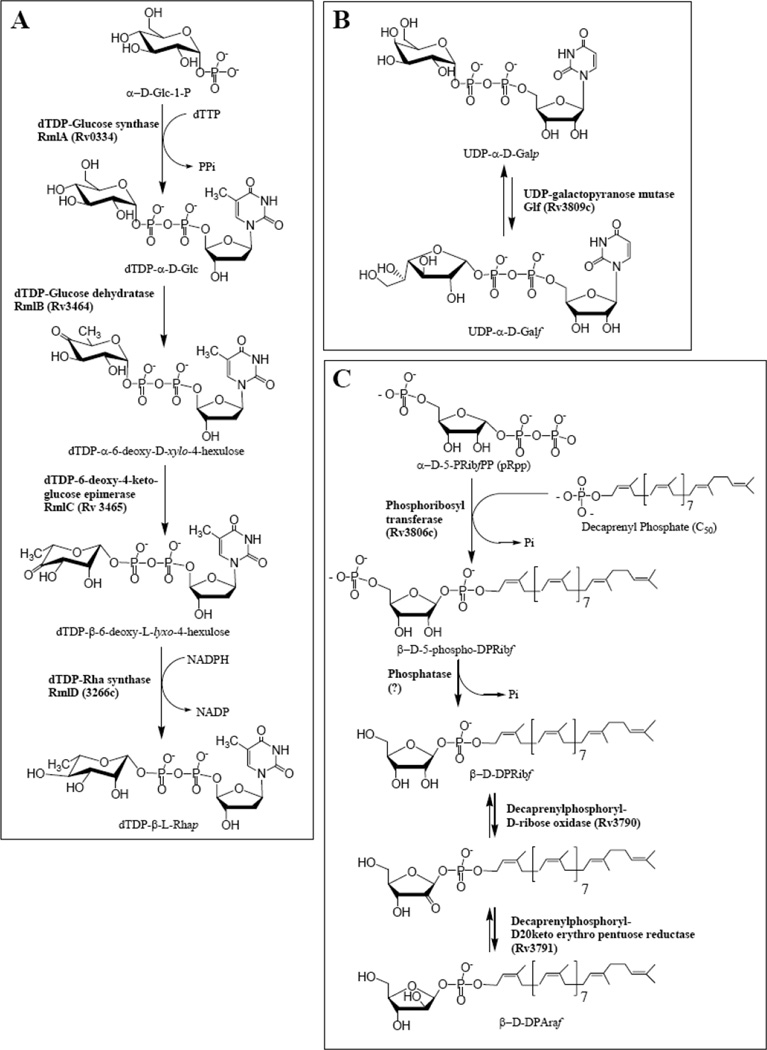

The biosynthesis of the various sugar donors required for AG polymerization are shown in Fig. (3). Many of these enzymes, as opposed to the enzymes involved in polymerization (Fig. (4)) are soluble and have been further advanced as drug targets. The biosynthetic pathways shown here are mostly known with a great deal of certainty, and several of these enzymes will be discussed as drug targets below.

Fig 3.

The biosynthesis of the activated sugars required for AG biosynthesis: (A) The biosynthetic pathway for the formation of dTDP-Rha; (B) the biosynthetic pathway for the formation of UDP-Galf; (C) the biosynthetic pathway for the formation of decaprenylphosphoryl-D-arabinose.

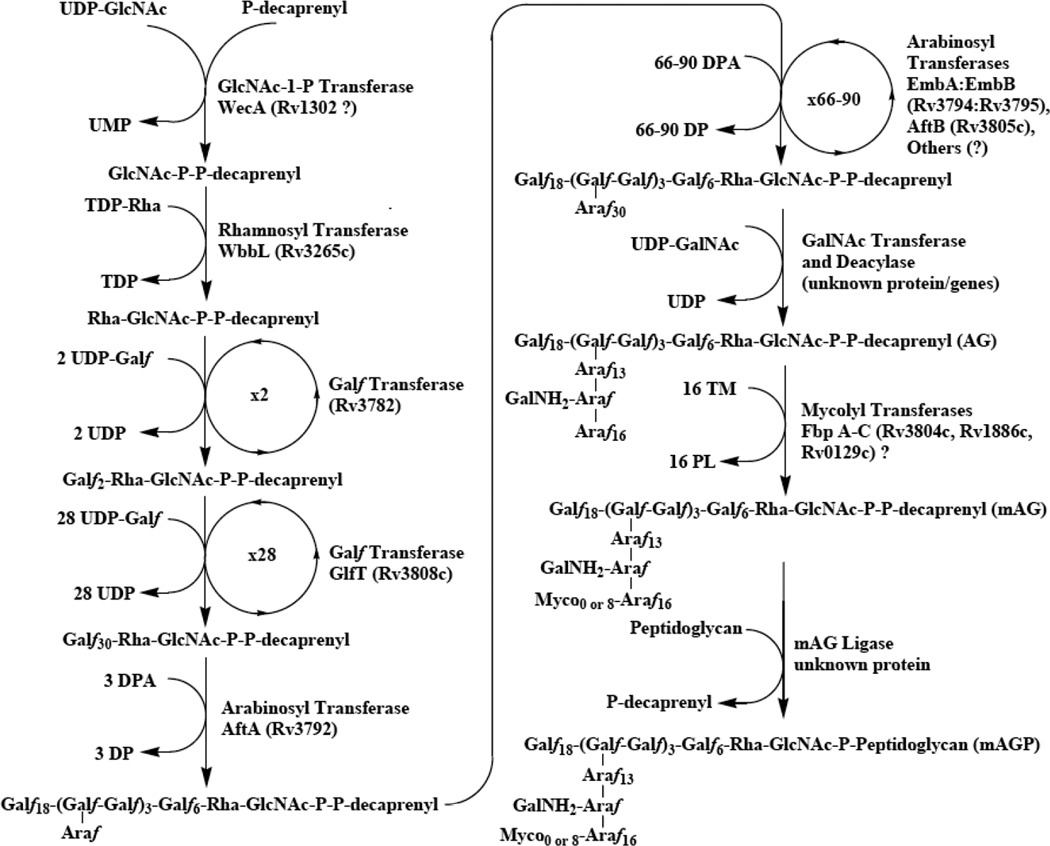

Fig 4.

The biosynthetic pathway of mycolyl arabinogalactan. The polymer is formed on decaprenyl phosphate as shown. The order of the later events is not yet known; the ligation to peptidoglycan is shown as the last step. However, the arabinan and mycolates or just the mycolates may be added after ligation to peptidoglycan. The addition of the succinyl residue is not shown and the addition of the GalNH2 residue as shown in the figure is, in fact, speculative.

In Fig. (4), the polymerization of AG is shown along with the attachment of mycolic acids and the attachment of the entire polymer to peptidoglycan. As mentioned above the molecule is synthesized on the carrier decaprenyl phosphate. The first sugar, GlcNAc, is attached as α-GlcNAc-1-P resulting in a diphosphate bridge to the carrier lipid. The attachment of the rhamnosyl, galactofuranosyl, and arabinofuranosyl proceeds subsequently. The enzyme WbbL[36] attaches the rhamnosyl residues and is discussed as a drug target below. The galactan is biosynthesized by two bifunctional galactofuranosyl transferases, with the first two residues added to the rhamnosyl residue by the galactofuranosyl transferase encoded by Rv 3782 [37], and the remaining 1,5 and 1,6 galactofuranosyl residues added by the bifunctional galactofuranosyl transferase GlfT [38,39,40]. Excitingly, the arabinosylation is now becoming at least somewhat understood. The first arabinosyl residue is added to three places on the galactan (Fig. (4)) [41] followed by the action of α-1,5 Araf transferase, AftA [41]. It now seems likely that the next α-1,5 residues are added by the so called Emb proteins, the known targets of ethambutol [42]. Thus, if EmbC is knocked out essentially all arabinosylation of lipoarabinomannan (LAM) is terminated [43], and if EmbB or EmbA is terminated the structure of AG is altered [44] (LAM is polymer related to AG but where the arabinosyl residues are attached to mannan rather than galactan and this polymer is not covalently attached to peptidoglycan.). Finally, if the analog of EmbA/B is knocked out of corynebacteria only single arabinosyl residues are added to the galactan [12]. The most straightforward explanation of these results is that Emb proteins are responsible for the addition of the next α-1,5 residues to the AftA attached arabinosyl residues; and this explanation has recently received further substantiation by the inhibition of α-1,5 arabinosyl transferase activity with ethambutol [45]. The presence of two closely related AG Emb proteins, EmbA and EmbB may be explained by the formation of an active heterodimer although this has not been experimentally shown. Clearly at least one α-1,3 arabinosyl transferase remains to be identified, and most profoundly, how the formation of the exact number of arabinosyl residues shown after the various branches in Fig. (1) occurs is unknown. Still it is appearing that the arabinan is built up on the galactan directly, without any biosynthetic intermediates such as lipid linked arabinans, and the arabinosyl transferases are being identified.

Finally the order of the later events in the pathway are not known; specifically it is not known when the transfer of the growing AG molecule to peptidoglycan occurs—it could be before arabinosylation, during arabinosylation, after arabinosylation but before mycolylation, or after all these events have occurred as illustrated without evidence in the figure. It also follows that it is unknown as to when the mycolic acids are attached; they might well be attached after attachment of AG to PG rather than before as shown in the figure.

Our understanding of the biosynthesis of the mycolic acids has advanced greatly in the last decade and has been reviewed [8,9]. The pathway, as it is now known, is presented in Fig. (5). This pathway is now largely understood except for the last few steps after the condensation of the meromycolate and the C-26 fatty acid. Unique and important drugs targets are found in this pathway. Important concepts include the formation of C-20 and C-26 by a Type I fatty acid synthase (FAS I) system, elongation of C-20 by a Type II fatty acid synthase (FAS II) system to form the meromycolates, modification of the meromycolates (cyclopropanation etc.), condensation of the meromycolate and C-26 by PKS-13, and finally maturation of the mycolic acid and its attachment to AG.

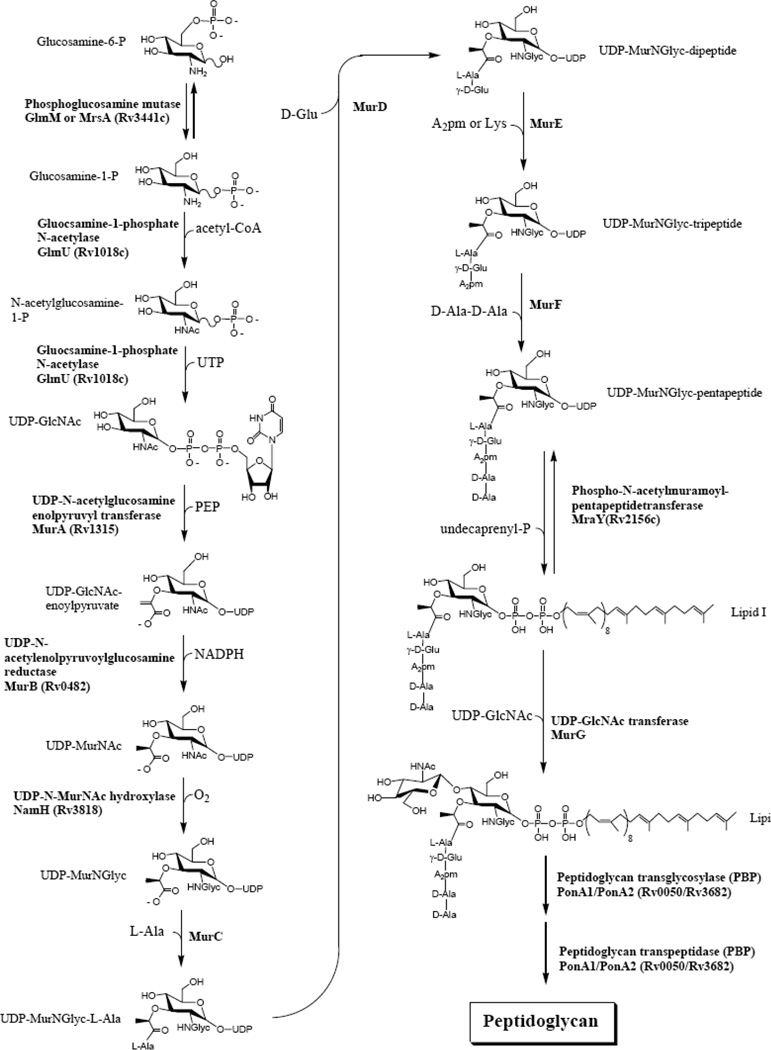

Finally, the biosynthetic pathway of peptidoglycan is shown in Fig. (6). This pathway for the most part has not been shown directly in M. tuberculosis, but rather by the comparison of the genome sequence with the known biosynthetic pathway of peptidoglycan in other organisms, especially E. coli where the peptidoglycan is almost identical. The only difference is the oxygenation of the N-acetyl group on the muramic acid to an N-glycosyl group (Fig. (6)), but this enzyme may not be a good target as it is not essential [46]. The targeting of peptidoglycan biosynthesis is an important and vibrant field much bigger than M. tuberculosis alone, and is not emphasized in this review, although a few targets that maybe especially appropriate for new TB drugs are discussed below.

Fig 6.

The formation of peptidoglycan. Shown is the standard PG formation pathway used by most bacteria with the only differences being the oxidation of the acetyl group on muramic acid to a glycolyl group. Not shown is the amidation and methylation of glycolipid II that has been recently demonstrated [28].

In summary, with Figs. (2–6), the entire biosynthetic pathway (with still a few gaps) of mycolyl arabinogalactan peptidoglycan (mAGP) is presented. This now allows us to discuss individual targets.

M. TUBERCULOSIS CELL WALL BIOSYNTHETIC TARGETS

The cell wall core biosynthetic enzymes and their potential as drug targets will be discussed in groups corresponding to Figs. (2–6). Relevant aspects of each enzyme are listed in Tables 1–5 where each table corresponds to a pathway shown in one of the figures.

Table 1.

Analysis of Decaprenyl Phosphate Biosynthetic Enzymes (see Fig. (2))

| Target | Plus | Minus |

|---|---|---|

| 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase (DXS) Rv2682c |

|

|

| 1-Deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase (IspC) Rv2870c |

||

| 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D- erythritol synthase (IspD) Rv3582c |

||

| CDP-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4- phosphate kinase (IspE) Rv1011 |

|

|

| methylerythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase (IspF) Rv3581c |

|

|

| 1-hydroxy-2-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl 4- diphosphate synthase (IspG) Rv2868c? |

|

|

| isopentenyl diphosphate / dimethylallyl diphosphate synthase (IspH) Rv1110 or Rv3382? |

|

|

| E,Z Farnesyl synthase (1086c) | ||

| Decaprenyl diphosphate synthase (2361c) |

|

Table 5.

Analysis of Peptidoglycan Biosynthetic Enzymes (See Fig. (6))

| Target | Plus | Minus |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphoglucosamine mutase (GlmM and also known as MrsA) Rv3441c |

|

|

| Glucosamine-1-phosphate N-acetylase (GlmU) Rv1018c |

|

|

| UDP-N-acetylglucosamine enolpyruvyl transferase (MurA) Rv1315 |

|

|

| UDP-N- acetylenolpyruvoylglucosamine reductase (Mur B) Rv0482 |

|

|

| UDP-N-MurNAc hydroxylase (NamH) Rv3818 |

|

|

| Formation of UDP-MurNGlyc- pentapeptide: Mur C,D,E,F (the enzymes that add the rest of the amino acids) and D Ala/D Ala ligase |

|

|

| Phospho-N-acetylmuramoyl- pentappeptidetransferase (MraY) Rv2156c |

|

|

| UPD-N-acetylglucosamine-N- acetylmuramyl- (pentapeptide)pyrophosphoryl- undecaprenol-N-acetylglucosamine transferase (MurG) Rv2153c |

|

|

| Peptidoglycan transglycosylase [PBP] PonA1 Rv0050 and PonA2 Rv3682 |

|

|

| Peptidoglycan transpeptidase [PBP] PonA1 Rv0050 and PonA2 Rv3682 |

|

|

Decaprenyl Phosphate Synthesis

Basic characteristics of the enzymes involved in decaprenyl phosphate synthesis (Fig. (2)) are provided in Table 1. The MEP pathway forming the polymerization precursors is considered first. An advantage of targeting pre-polymerization events is that isopentyl diphosphate and dimethylallyl diphosphate are required for menaquinone biosynthesis, and thus, inhibiting enzymes required for their synthesis should shut down both energy formation and cell wall biosynthesis. Hence considerable effort as of late has been applied to inhibiting enzymes such as IspC (Fig. (2) and Table 1). 1-Deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase (DXS) catalyzes the first step of the mevalonate independent pathway via condensation of pyruvate and glyceraldehyde-3-phopshate (GAP). This reaction has been characterized as a thiamin diphosphate dependent acyloin condensation between C2 and C1 of pyruvate and GAP to yield 1-deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate (DXP) [23]. DXS has been cloned from several sources including E. coli [23,26,47], Streptomyces spp. [47,48], Rhodobacter capsulatus [49], Pseudomonas aeruginosa [50], Synechococcus leopoliensis [51], several plant spp. [52,53,54], and M. tuberculosis [55,56]. DXS from M. tuberculosis has been enzymatically characterized [55] and the crystal structure of the enzyme from E. coli has been solved [57]. Overall, there is considerable interest in screening for inhibitors of DXS activity as potential antibiotics, herbicides or anti-malarials. However, relatively little information about the enzymatic properties of these transketolases from pathogens has been published, a situation that may be problematic in terms of drug development given the predicted similarities with eukaryotic transketolases at the amino acid level.

The second reaction, rearrangement and reduction of DXP to form MEP is catalyzed by IspC, which is encoded by Rv2870c in M. tuberculosis [31,58]. The gene encoding this enzyme has also been cloned from Z. mobilis, E. coli, Mentha x piperita, Arabidopsis thaliana, Synechocystis sp., Streptomyces coelicolor and P. aeruginosa [48,50,59,60,61,62,63] and detailed kinetic data has been collected for the E. coli [60] and the M. tuberculosis enzymes [58,64]. In addition, a significant number of structures have been solved for this enzyme from several sources [65,66,67,68,69,70] making this enzyme an ideal potential drug target. However, high density transposon mutagenesis indicate that Rv2870c is not essential in M. tuberculosis [71], and the antibiotic fosmidomycin, which has been shown to inhibit IspC [72,73] in a number of organisms, is not active against Mycobacterium tuberculosis [58], even though the MEP pathway appears to be the sole IPP biosynthetic pathway in this organism. Indeed, it has been shown that Rv2870c is inhibited by fosmidomycin at concentrations that are comparable to other DXP reductoisomerases [50,58, 59,74,75]. Rv2870c can complement an inactivated chromo-somal copy of IspC in Salmonella enterica and the complemented strain remains sensitive to fosmidomycin. Thus, M. tuberculosis resistance to fosmidomycin is not due to intrinsic properties Rv2870c and the enzyme appears to be a valid drug target in this pathogen, despite the prediction that it is not essential.

Once MEP is formed it is converted to 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate by the consecutive action of IspD, IspE and IspF [76,77,78,79]. Finally IspG and IspH act sequentially to convert 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate into IPP and DMAPP via 1-hydroxy-2-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl 4-diphosphate. Interestingly, a single enzyme, IspH, forms both IPP and DMAPP [80]. Little has been published regarding the properties of the M. tuberculosis versions of these enzymes, although IspD, IspE and IspF have been identified as Rv3582c, Rv1011 and Rv3581c respectively, cloned, expressed and at least partially characterized (authors, unpublished data). In general, it is thought that all of the MEP pathway enzymes after IspC will also provide good drug targets. IspE is a particularly interesting potential drug target, as a good deal is known about development of kinase inhibitors and IspE appears to be an unusual kinase. The E. coli version of IspE displays the α/β fold characteristic of the galactose kinase/homoserine kinase/mevalonate kinase/phosphomevalonate kinase superfamily, but appears to bind adenosine in the unusual syn orientation of the base with respect to the ribose across the glycosidic bond [81,82]. Although IspE-H all appear to be reasonable potential drug targets, all present significant difficulty in development of assays amenable to high throughput screening (HTS) in that the required substrates are not readily available (Table 1).

Once synthesized, IPP and DMAPP are polymerized into longer polyprenyl diphosphate molecules via sequential addition of IPP to allylic diphosphates. These reactions are catalyzed by enzymes known as polyprenyl diphosphate synthases, and are specific for the type of stereochemistry (E or Z) of the introduced allylic double bond. The first amino acid sequence of a Z-polyprenyl diphosphate synthase was reported in 1998, when UPS was cloned from Micrococcus luteus and characterized [83]. Typically, Z-prenyl diphosphate synthases, which synthesize undecaprenyl diphosphate utilize E,E-farnesyl diphosphate as the allylic acceptor synthesizing long-chain products with the a common diE, polyZ stereo conformation [29,30,31,32]. M. tuberculosis is unusual in that it has 2 genes (Rv1086 and Rv2361c) encoding proteins with significant sequence similarity to UPS. Rv1086 encodes an E,Z-farnesyl diphosphate [33,34] and Rv2361c encodes a decaprenyl diphosphate synthase [33,35], that adds seven isoprene units to E,Z-farnesyl diphosphate (E,Z-FPP) synthesized by Rv1086.

The enzymes involved in polymerization of IPP to from decaprenyl diphosphate, Rv1086 and Rv2361c, have been cloned and expressed in the authors’ laboratories [33,35] and recently X-ray structures obtained with various substrates and analogs (J. Naismith and D. Crick unpublished results). Efforts to obtained specific inhibitors are underway, while keeping in mind that human dolichol synthase (or cis-isoprenyltransferase) may have a similar structure [84]. High density transposon mutagenesis experiments predict that Rv2361c is likely essential in M. tuberculosis H37Rv [71]; however, the enzyme encoded by Rv1086 is not predicted to be essential [71]. Data indicate that Rv2361c is capable of synthesizing E,Z-FPP although at a much reduced catalytic efficiency [35]; therefore, Rv2361c may be able to compensate for the deletion of Rv1086 at least when grown in vitro. Thus, Rv1086 may not be a good drug target in M. tuberculosis as speculated earlier [34], even though synthesis of Dec-P appears to be essential.

Formation of Arabinogalactan Precursor Molecules

Basic characteristics of the enzymes involved in arabinogalactan precursor synthesis (Fig. (3)) are provided in Table 2. With the exception of the last two enzymes involved in decaprenylphosphoryl-d-arabinose synthesis, these enzymes are well understood as are the pathways they are involved in. Most of the enzymes are soluble and all have been expressed and at least somewhat characterized [85,86,87,88,89,90]. All of them are essential for growth of M. tuberculosis according to insertion mutagenesis [71] except for Glf which had a somewhat marginal score and likely its product UDP-Galf could have been obtained from adjacent growing bacterial colonies. In addition RmlB [91], RmlC [91], RmlD [92], and Glf [93] have been shown to be essential in M. smegmatis by knocking the genes out in the presence of a rescue plasmid with a temperature sensitive origin of replication. Crystal structures have been obtained for RmlA-D in various species of bacteria [94,95,96,97,98,99,100], including RmlC from M. tuberculosis in the presence and absence of the substrate analog dTDP-rhamnose [101]. Glf has also been crystallized from several species including M. tuberculosis [94,97]. However attempts to get co-crystals containing substrate or substrate analogs have not been successful.

Table 2.

Analysis of Arabinogalactan Precursor Biosynthetic Enzymes (See Fig. (3))

| Target | Plus | Minus |

|---|---|---|

| dTDP-Glucose synthase (RmlA) Rv0334 |

|

|

| dTDP-Glucose dehydratase (RmlB) Rv3464 |

|

|

| dTDP-6-deoxy-4-keto-glucose epimerase (RmlC) Rv3465 |

|

|

| dTDP-Rha synthase (RmlD) Rv3266c |

|

|

| UDP-Galactopyanose Mutase (Glf) Rv3809c |

|

|

| Phosphoribosyl transferase Rv3806c |

|

|

| Decaprenylphosphoryl-D-ribose oxidase Rv3790 |

|

|

| decaprenylphosphoryl-D-2-keto erythro pentuose reductase Rv3791 |

|

|

| UDP-GlcNAc formation enzymes (see Table 5). |

Enzymatic assays in microtiter plate format have also been published for several of these enzymes. Two fundamentally different assays for Glf exist, one based on enzymatic activity [85] and the other based on binding of a fluorescently labeled substrate analog leading to a fluorescence polarization assay [102,103]. A problem with obtaining enzymatic activity of Glf is the requirement that the FAD co-factor be in the reduced FADH2 form. In our hands this has required the use of the rather strong reducing agent, dithionite. This reagent is not compatible with the microtiter plate assay that uses sodium periodate and thus that assay is limited to crude preparations of Glf where FAD is reduced by NADH by an unknown mechanism. The fluorescence polarization assay bypasses this problem in that only substrate binding and not enzymatic reactivity is required. Encouragingly, inhibitors of Glf has been identified using that method [103]. At present in the author’s (McNeil’s) laboratory inhibitors of Glf are being approached by developing an assay where Glf is coupled to the galactofuranosyl transferase GlfT (see below) although, difficulties with the dithionite remain an issue.

An enzymatic assay for RmlB-D suitable for microtiter plates has also been published [86]. This assay is relatively straightforward in that the reduction of NADPH is monitored at OD340. Enzyme concentrations can be adjusted so that inhibitors for all 3 or any specific enzyme can be detected although compromises in optimal substrate concentrations might be an issue. Recent efforts have focused on assaying for RmlC, in which case RmlB is used in a pre-incubation to prepare the dTDP-4-keto-6-deoxyglucose substrate and RmlD is used in large excess as a “helper” enzyme. RmlC has many attractive components of a good drug target. The enzyme is soluble, crystal structures with substrate analogs are available, the enzyme is essential, evidence that its inhibition could be lethal has been presented since inhibition of WbbL downstream in the same pathway results in cell death [36], and clues as to the structure of the transition state, and conformation changes of the sugar residue have been published [101].

In theory all eight precursor formation enzymes of Table 2 are reasonable drug targets in that they are all essential for growth of M. tuberculosis and have been cloned and expressed. However the last two enzymes in decaprenylphosphoryl-d-arabinose synthesis have not been expressed robustly and an assay appropriate for microtiter plates is not immediately obvious. In contrast, an assay for phosphoribosyl transferase should be straight forward based on detection of released PPi but such an assay has not yet been accomplished. Targeting of arabinose metabolism might be more effective at the level of arabinosyl transferases as discussed below.

Arabinogalactan Polymerization Biosynthetic Enzymes

Basic characteristics of the enzymes involved in arabinogalactan polymerization (Fig. (4)) are provided in Table 3. In general these enzymes are not as well studied as the enzymes that form arabinogalactan precursors, but that state of affairs is quickly changing. Although none of the enzymes identified for rhamnosyl and galactosyl polymerization are integral membrane proteins, they do tend to be membrane associated proteins. None of the proteins have had a structure determined on them to date.

Table 3.

Analysis of Arabinogalactan Polymerization Biosynthetic Enzymes (See Fig. (4))

| dTDP-Rha:α-D-GlcNAc-pyrophosphate polyprenol, α-3-L-rhamnosyltransferase (WbbL) Rv3265c |

|

|

| Galactofuranosyl transferase Rv3782 |

|

|

| Galactofuranosyl transferase (GlfT) Rv3808c |

|

|

| α-5-arabinosyl transferase (EmbB and EmbA) Rv3794 and Rv3795 |

|

|

| Decaprenylphosphoryl-D-arabinose:5- galactofuranosyl arabinosyltransferase (AftA) Rv3792 |

|

|

| β-arabinosyl transferase (AftB) Rv3805c |

|

|

| α-3-arabinosyl transferase (attaches an α arabinosyl residues to C-3 of an α-1,5- arabinosyl residue) |

|

|

| Arabinogalactan/peptidoglycan ligase. |

|

|

The two most highly studied of these glycosyl transferases are the rhamnosyl transferase, WbbL [36], and major galactan polymerase, GlfT [38,39,40]. To target these enzymes requires robust expression, preparation of both the sugar donor and acceptor, and development of an assay appropriate for microtiter plates. These requirements are slowly being met. For WbbL, the most recalcitrant problem is the production of soluble enzyme in reasonable amounts. Currently in the McNeil lab, reasonable amounts of membrane associated WbbL can be produced; efforts to improve on expression are on going at least in his lab and the lab of Ben Davis (Ben Davis personal communication). The acceptor for WbbL, GlcNAc-P-P-decaprenyl, is reasonably amenable to chemical synthesis [104] and has recently been prepared (Michio Kurosu personal communication and Ben Davis personal communication). The donor, dTDP-Rha can be prepared enzymatically [18,36] and chemically (Ben Davis personal communication). It is anticipated that microtiter plate based assays will be based on detection of the dTDP, either by release of phosphate, coupling to lactate dehydrogenase [105], or by coupling to ATP production.

Soluble GlfT has been produced in reasonable amounts [38]. The donor substrate UDP-Galf is difficult to produce but can be prepared in reasonable yields both chemically [106] and chemically/enzymatically [107]. Various synthetic acceptors have been prepared chemically [38,108]. As with WbbL, the read out for a microtiter plate assay will most likely be based on detection of UDP. Efforts to couple GlfT with Glf are ongoing in the McNeil laboratory; the largest hurdle to overcome is the necessity in our hands for dithionite in order to get reproducibly active Glf, and dithionite can interfere with various enzymes and assays. Finally, it should be noted that the galactofuranosyl transferase, encoded by Rv3782, which adds two Galf residues to the rhamnosyl linker unit [37], can also be targeted in much the same way as GlfT.

The arabinosyl transferases (Fig. (4)) are becoming more understood. Two have been clearly identified, AftA [41] the enzyme that adds the first single arabinosyl residue to galactan (Fig. (4)), and AftB (Rv3805c) [45] the enzyme that adds the terminal arabinosyl residue to the AG. AftA has been expressed from E. coli in soluble form [41]. An improved chemical synthesis of the donor decaprenylphosphoryl-d-arabinose has been recently reported [109]. Currently the galactan acceptor for AftA has been prepared from Corynebacterium glutamicum in which aftA has been knocked out; whether this could be used for screening for inhibitors is not clear. Further, as discussed earlier, the EmbA/EmbB arabinosyl transferase is likely an α-1,5 transferase, although as also discussed earlier other α-1,5 transferases may also be present.

Additional arabinosyl transferase activities are detected in crude M. smegmatis extracts using specifically designed acceptors [110,111,112]. Both α-1,5 transferase activity can be seen or α-1,3 followed by β1,2 depending on the oligoarabinoside substrate (Delphi Chatterjee personal communication). The donor can be prepared directly as chemically synthesized decaprenylphosphoryl-d-arabinose, or indirectly by feeding the crude membranes radioactive phosphoribosyl diphosphate which is converted to decaprenylphosphoryl-d-arabinose by the membranes. An exciting possibility to screen for inhibitors of these arabinosyl transferases is the attachment of the acceptor to scintillation proximity beads; such work is currently in progress (Delphi Chatterjee personal communication).

Finally it should be noted, arabinogalactan/peptidoglycan ligase remains refractory to efforts thus far to develop a facile assay for it or to identify the protein/gene, although its activity can be demonstrated [113]. This enzyme is functionally parallel to the ligase that attaches teichoic acids to peptidoglycan in many gram positive bacteria [113] where it has also not yet been identified.

Mycolic Acid Biosynthesis

Basic characteristics of the enzymes involved in mycolic acid biosynthesis (Fig. (5)) are provided in Table 4. The enzymology of mycolic acid biosynthesis is a remarkable radiation of typical bacterial fatty acid anabolic pathways with some very unique aspects. This segment of cell wall biosynthesis is widely considered to be among the most validated, largely because the mode of action of INH involves this enzymatic machinery. Despite the complexities of the mode of action of INH, the effect of this prodrug on mycolic acid biosynthesis certainly plays a role in its efficacy, and does provide some level of validation of the entire pathway as a useful target for antibiotic development [64,114,115].

Table 4.

Analysis of Mycolic Acid Biosynthetic Enzymes (see Fig. (5))

| Target | Plus | Minus |

|---|---|---|

| Acyl carrier protein phosphopantetheinyl transferase (AcpS) Rv2523c |

|

|

| Fatty acid synthase type I (FasI) Rv2524c |

|

|

| Malonyl-CoA:ACP transacylase (FabD) Rv2243 |

|

|

| β-ketoacyl-ACP synthase-III (FabH) Rv0533c |

|

|

| β-ketoacyl-ACP reductase (FabG1 or MabA) Rv1483 |

|

|

| β-hydroxyacyl-ACP hydratase/dehydratase/isomerase (FabA, FabZ) Rv0241c, Rv0636, Rv0130 and others. |

|

|

| 2-trans-enoyl-ACP-reductase (InhA) Rv1484 |

||

| β-ketoacyl-ACP synthase (KasA) Rv2245 |

||

| β-ketoacyl-ACP synthase (KasB) Rv2246 |

||

| Acyl-ACP desaturases (DesA1 and DesA2) Rv0824c or Rv1094 |

|

|

| Meromycolyl-AcpM methyltransferases Cyclopropane synthases; (MmaA2) Rv0644c, (PcaA) Rv0470c, (Mma4) Rv0642c, (Mma3) Rv0643c, (Mma2) Rv0644c, (Mma1) Rv0645c, (Cma2) Rv0503c |

|

|

| Meromycolyl Carboxylase (AccA3) Rv3285, (AccD4) Rv3799c, (AccD5) Rv3280 |

|

|

| Fatty Acyl-AMP ligase (FadD32) Rv3801c |

|

|

| Condensase (Pks13) Rv3800c |

|

|

| Mycolyl transferase (FbpA, FbpB, FbpC) (Rv3804c, Rv1886c, Rv0129c) |

|

|

As with all fatty acid biosynthetic systems, mycolic acid synthesis proceeds with a growing fatty acyl chain attached to an obligate prosthetic group that must be post-translationally attached to key carrier proteins (or domains) of the biosynthetic apparatus. This enzyme-catalyzed modification involves the attachment of a 4’-phosphopantethiene to a hydroxyl group of an invariant serine of the carrier protein. Mycobacteria possess two such phosphopantetheinyl transferases for activating lipid biosynthesis, but they are not redundant and only one of these (Rv2523c or AcpS) is involved in phosphopantetheinylation of the two fatty acid synthase systems in mycobacteria [116]. Targeting this enzyme would have the benefit of disrupting both cell wall specific mycolic acid synthesis, and the synthesis of vital components of the plasma membrane. The stability of existing pools of already phosphopantetheinylated acyl carrier proteins (or domains) is unknown, however, and the kinetics of killing following the inhibition of AcpS are therefore somewhat unpredictable and require further validation.

The starting point for mycolic acid synthesis is the workhorse FAS I protein that generates short-chain primers for the dissociated FAS II system. This essential enzyme encodes all of the biochemical reactions necessary for chain elongation in the production of saturated fatty acids. This enzyme has been purified, and HTS-amenable assays using simple substrates have been developed [117]. One complication with targeting the FAS I system is the highly conserved nature of these systems throughout living systems, making inhibition of human FAS I a problem. Another complication is that the large size of this enzyme (two 500kD monomers for an active dimer), and the presence of multiple discrete active sites will complicate lead optimization efforts.

The primers generated from the FAS I system are passed off to the dedicated machinery of the Type II fatty acid synthase system as their CoA esters, and are loaded on the essential mycolic acid-specific acyl carrier protein AcpM (Rv2244) [118] by the action of the β-ketoacyl ACP synthase III, FabH (Rv0533c). FabH catalyzes a two-step process during which the acyl chain from a CoA ester is first transferred to an active site cysteine, and then subsequently condensed with malonyl-AcpM to yield the first β-ketoacyl intermediate for the repetitive enzymes of the FAS II system. The availability of both apo and substrate-bound crystals of FabH would greatly facilitate structure-based design for this target, however saturating transposon mutagenesis experiments in two independent strains of M. tuberculosis have revealed the surprising result that FabH activity is not essential, greatly diminishing its value as a potential target [71]. FabH activity requires malonyl-AcpM which is formed by the enzyme malonyl-CoA AcpM transacylase, FabD (Rv2243). FabD has been biochemically characterized [119] and high-resolution crystal structures of homologs of this enzyme have been solved [120]. Enthusiasm for this target is diminished, however, by the presence of a second isoform, FabD2 (Rv0649), that has recently shown to be biochemically active [121]. So although saturating transposon mutagenesis gave no conclusive essentiality results with respect to FabD itself [71], FabD2 has been found to be non-essential and it seems likely that FabD would be non-essential as well.

AcpM bound β-keto thioesters enter the cycle of fatty acid synthesis through the action of FabG1, also called MabA (Rv1483), an enzyme that reduces these to the corresponding β-hydroxy thioesters at the expense of NADPH. The enzyme is one of two nicotinamide-dependent enzymes required for mycolic acid elongation, and is one relevant target for an INH-NADP adduct by which it is inhibited in vitro very efficiently [122]. The crystal structure of FabG1 from M. tuberculosis has been solved, and the enzyme presents a straightforward assay that could easily be adapted to HTS [123,124]. Surprisingly, this enzyme has been found to be non-essential by transposon mutagenesis, a result that underscores the need for confirmatory evidence by site-directed mutagenesis since this seems unlikely to be substantiated by site-specific gene inactivation.

β-Hydroxyacyl-AcpM products of FabG1 are next dehydrated by the action of a (3R)-hydroxyacyl dehydratase to the corresponding trans olefins. The prototype for this transformation is the FabZ protein of E. coli but a second type of dehydratase (FabA) also exists in this organism that has an additional trans (E) Δ2-cis (Z) Δ3 isomerase activity. Unfortunately, neither FabZ nor FabA are easily identifiable based upon simple sequence homology from M. tuberculosis. Bioinformatic analysis suggests that there are between 6 and 11 proteins that may encode R-specific hydratases/dehydratases, many of which occur clustered with proteins with defined function in mycolic acid biosynthesis, four of these are essential [125]. Biochemical analyses of at least two of these proteins, Rv3389c and Rv0130 have been performed in the hydratase direction and have demonstrated that the expected β-hydroxyacyl product is formed. Rv3389c was found to be nonessential by saturating transposon mutagenesis, a finding confirmed recently by site-specific inactivation with no affect on lipid biosynthesis[71,125]. The crystal structures of Rv0130 and Rv0216 (another of the putative hydratase/dehydratase family) have been solved, although the latter protein was not found to be catalytically active with crotonyl-CoA [126,127]. Thus, there remains considerable ambiguity as to the identity and number of dehydratases involved so this target remains elusive.

InhA (Rv1484) is the 2-trans-enoyl-ACP-reductase that completes a cycle of 2-carbon extension producing the final saturated lipid at the expense of NADH. As the name InhA implies, this target was discovered as a target for the front-line chemotherapeutic INH, which is an acyl hydrazide prodrug that requires oxidative activation by the mycobacterial catalase, KatG [128]. The activated species forms a stable adduct with nicotinamide cofactors and inhibits enzymes dependent upon these, including InhA [129]. The necessity for prodrug activation, widespread resistance due to KatG mutation and the complexity of the effects of isoniazid adducts with nicotinamide cofactors have resulted in extensive interest in direct inhibitors of InhA that would circumvent the requirement for activation. The enzyme is soluble, multiple crystal structures with both substrates and various inhibitors bound are available, and a straightforward assay based upon NADH oxidation has been developed [130,131]. Not surprisingly therefore, there has been considerable effort in both screening and lead optimization of hits, with activity directed at InhA, notably including derivatives of alkyl diphenyl ethers [132] and pyrrolidine carboxamides [133] which have affinities for the enzyme in the nanomolar range. The alkyl diphenyl ethers are also very active against whole M. tuberculosis in culture [132], including drug resistant strains, and these compounds are perhaps the most encouraging of all early leads of new cell wall drugs against tuberculosis. It seems important to note that this strategy began with both a known target and known compounds, rather than beginning with what appears to be a good target with no known drugs against it. Equally important to note, with respect to InhA, that despite that this is widely considered perhaps one of the most well validated of cell-wall targets, highly-specific inhibitors have antibacterial activity, and inhibition of this target leads to the death of actively growing bacilli, this gene has been found to be non-essential by transposon mutagenesis. An inspection of the original Transposon Site Hybridization (TraSH) data from that experiment reveals that the representation of mutants in the output pool was, in fact, suppressed for inhA (the actual ratio was 0.39) but it was not suppressed more than the five-fold cut-off used by these authors. Conditional expression systems using either temperature-sensitive mutants, or inducible acetamide promoters have convincingly demonstrated essentiality [134,135].

Chain elongation can continue by the condensation of a malonyl-CoA molecule onto the AcpM-bound substrate via the action of one of the two β-ketoacyl ACP synthases, KasA (Rv2245) or KasB (Rv2246). Although definitive biochemical analysis has not yet clearly defined the roles of these two proteins, in vitro overexpression data suggests that KasA performs the initial elongation steps producing ACP-bound mero acids of about 40 carbons in length, while KasB extends these to an average length of about 54 carbons [136]. Like InhA, conditional expression of KasA has been shown to induce lysis of actively growing cells, but both KasA and KasB were found to be essential by TraSH [71,134]. In contrast, KasB has been shown to be non-essential in M. marinum although these bacilli were compromised for in vivo survival and had highly permeable cell walls with shorter mycolic acids [137]. An HTS-compatible assay for these enzymes has been developed, [138] and a crystal structure for the KasB protein has been reported [139]. Co-crystals of a related enzyme, FabF from E. coli with thiolactomycin, cerulenin [140], and more recently platensimycin [141] have been reported.

Chain elongation to form the full AcpM-bound meromycolic acid likely occurs coincident with structural modifications at both the “distal” and “proximal” ends [142]. These structural modifications all radiate from a cis double bond that is installed into the growing fatty acid, most likely by one of the three putative soluble diiron desaturases (DesA1, DesA2, and DesA3) encoded in the M. tuberculosis genome based on studies in M. smegmatis [143]. These soluble enzymes are related to plant desaturases and are non-heme-containing oxygen activating systems. The function of one of these, DesA3, has been proposed to be introduction of a double bond into stearoyl-CoA at the Δ9 position, and this protein has been shown to be an integral membrane protein with a soluble NADPH oxidoreductase [144,145] partner Rv3230c [145]. DesA1 (Rv0824c) and DesA2 (Rv1094) appear to be soluble proteins, and structural features from a recent crystal structure of DesA2 suggests that it may form part of the Δ5-desaturase involved in mycolic acid modification [146]. While there is obviously additional biochemical development of this system to be done, the importance of introducing meromycolic acid modifications is highlighted by the fact that both DesA1 and DesA2 are essential genes [71,146]. An alternative pathway of desaturation is also possible and illustrated in Fig. (5). In this scenario the trans double bond normally introduced during elongation is isomerized [8] followed by continued elongation.

Introduction of an olefin into the meromycolic acid is simply a way of activating these lipids for the final group of modification enzymes, the meromycolyl-AcpM methyl transferases. This amazing group of 7 proteins is most closely related to the E. coli cyclopropane fatty acid synthase and share with this enzyme an S-adenosyl-(l)-methionine-dependent methyl transfer. Subtle alterations at the active site of these enzymes generate remarkable chemical diversity from the high-energy cationic intermediate formed from methyl group transfer [147]. This can result in both cis and trans cyclopropane rings, α-methyl alcohols or methoxy ethers, functional groups that represent the only non-paraffinic moieties within the highly hydrophobic mycolic acid domain of the cell envelope. Both the geometry of these alterations and the extent of hydrophilic character can have dramatic effects on the cell surface, membrane fluidity and permeability [9,148,149]. The composition of the cell envelope is highly dynamic and responds to environmental changes; including internalization within human cells [148]. Structural features as specific as trans cyclopropane versus cis cyclopropane have been shown to influence the host innate immune system [150,151]. Probably because of this plasticity, none of the individual enzymes have been shown to be essential. Nonetheless, these enzymes present a unique opportunity as potential drug targets since the crystal structures of 5 of these enzymes have now been reported, and the binding site for S-adenosyl-l-methionine is highly conserved among the entire group [152,153]. The advantage of targeting this highly conserved region in multiple enzymes lies in lowering the probability of emergence of resistance [147]. A coupled colorimetric assay based upon the liberation of S-adenosyl-d-homocysteine that has been used to identify inhibitors of the E. coli cyclopropane fatty acid synthase could be adapted for screening, and in vitro assay conditions have been reported [142,154].

The penultimate step in mycolic acid biosynthesis is the Claisen condensation of the long meromycolic acid chain with the shorter 24 or 26 carbon α-branch to form the α-acyl-β-ketomycolic acid that is reduced to the final α-acyl-β-hydroxymycolic acid. Through some elegant studies in Corynebacterium glutamicum, both the mechanism and the enzymes involved in this process have been clarified. The meromycolate is first carboxylated by the enzymatic action of a multi-subunit acyl-CoA-carboxylase composed of AccA3 (Rv3285, the biotin carboxyl carrier protein), AccD4 and AccD5 (Rv3799c and Rv3280, the two apparently required subunits of the acyl-CoA carboxylase) [155]. AccA3 and AccD4 were predicted to be essential by transposon mutagenesis (67), a prediction that has been experimentally validated for AccD4 [155]. AccD5 was shown in the same study to co-immunoprecipitate with AccD4 but has not been reported to be essential. Thus the enzymes of the carboxylase complex that activates the meroacid for the condensase are nearing a level of biochemical resolution at which they could reasonably be proposed as new targets. It is interesting that in the broad-spectrum antibiotic development area, this target has begun to get increasing attention. It has been identified as the major target of the pseudopeptide pyrrolidinedione moiramide B, which has been the subject of considerable lead optimization efforts [156]. The alpha-branch acid is activated as an acyl-adenylate and loaded directly onto the condensase (Pks13, Rv3800c) by the enzyme FadD32 (Rv3801c) which is a fatty acyl-AMP ligase, a member of the acyl-CoA synthetase family of enzymes that has been shown to transfer the adenylated fatty acid directly to a polyketide synthase in place of CoA [157]. Purified FadD32 was shown in in vitro assays to function in activation of long-chain fatty acids, and transfer of these to Pks13 and a conceptual assay based upon ATP depletion are easy to imagine. Ultimately Pks13, loaded with the alpha branch acyl chain, catalyzes the condensation of the (presumably AcpM-bound) carboxylated meromycolate to form the α-acyl-β-keto mycolic acid [158]. This condensation step is obviously essential and would be a valuable target, yet considerable work remains to be done on the biochemistry of this enzymatic reaction, and simplified surrogate substrates for the AcpM-bound meromycolic acid will have to be developed.

The final steps involved in; (1) reduction of the β-keto to a β-hydroxy group, (2) transfer of the fully formed mycolic acid to the polyprenol lipid carrier [159], (3) translocation to an appropriate site for esterification, and (4) transfer from the carrier polyprenol to trehalose all remain biochemically too undefined to discuss as potential targets. However, just at this article was being completed the reductase was identified as Rv2509 by knocking out the analogous gene in Corynebacterium glutamicum and analyzing the resulting ketomycolates found on trehalose [160]

The presence of trehalose is clearly essential for mycolic acids to end up esterified properly to mycobacterial cell walls [161]. There are three mycolyl transferases, members of the Antigen 85 complex, that use trehalose-bound mycolates in trans-esterification reactions amongst the mono and dimycolyated forms of trehalose, and probably to cell wall arabinogalactan [162]. The three proteins appear to be somewhat functionally redundant, none are essential and independent knockouts of single enzymes show little phenotype, while double knockouts of these show moderate phenotypes [163]. An in vitro assay has been developed for these and a proof of concept inhibitor developed, but transfer of mycolic acid to a defined acceptor has not been biochemically demonstrated and these would be difficult targets to pursue.

Peptidoglycan Biosynthesis

The arrangement and sequence of genes responsible for PG synthesis in M. tuberculosis is similar to that in other bacteria [164], suggesting that the biochemistry is also similar [165]. Basic characteristics of the M. tuberculosis enzymes involved in peptidoglycan synthesis (Fig. (6)) are shown in Table 5. The bad news is that known peptidoglycan drugs are generally not effective against M. tuberculosis. β-lactams are in general thought to be ineffective against M. tuberculosis due to a combination of the permeability barrier and β-lactamases [17]. Occasionally this idea is challenged and it remains possible that the correct β-lactam and/or β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor cocktail could be effective against M. tuberculosis. In this regard, a brief mouse study using ethambutol (to help with permeability) and Augmentin (Amoxicillin and Clavulanic Acid) failed to control the growth of M. tuberculosis in mice (Anne Lenaerts and Michael McNeil unpublished). Fosfomycin, a MurA inhibitor, is ineffective against M. tuberculosis due to an alteration in a single amino acid residue in mycobacterial MurA [166] and perhaps to lack of uptake of this phosphonate [58]. d-Cycloserine inhibits l-alanine racemase and dipeptidyl synthetase, and thus preventing incorporation of d-alanyl-d-alanine into the pentapeptide side chains of PG. Although it is used as an anti-tuberculosis agent, this use is severely limited because d-cycloserine also generates central nervous system toxicity [167].

The topic of bacterial PG synthesis, in general, has been extensively reviewed [168,169,170,171,172]. Although there has been interest in the PG biosynthetic pathway as a drug target for many years, underexploited drug targets still exist in this pathway [173,174,175,176,177]. These potential targets include MurA-F (found in the cytosol), mraY and MurG (membrane bound proteins) and the transglycosylase/transpeptidases (penicillin-binding proteins or PBPs, which act extracellularly). Thus, the concept that PG synthesis is a source of underexploited drug targets appears to be particularly true for mycobacterial pathogens. In particular GlmU (Figs. (3 & 6)) is essential for formation of UDP-GlcNAc, a sugar donor for both PG and AG biosynthesis. It catalyzes both the acetylation of GlcNH2-1-phosphate and the reaction of the resulting product GlcNAc-1-phosphate with UTP to form UDP-GlcNAc [178]. The N-acetylation reaction is unique to bacteria as GlcNH2-6-phosphate is N acetylated in eukaryotes and thus is an attractive drug target. Crystal structures of this domain of the enzyme are available for other bacteria [179,180] and efforts to obtain the structure of the M. tuberculosis enzyme are on going (James Naismith personal communication). The enzyme has been expressed in soluble and active form in the McNeil laboratory and development of a microtiter plate assay based on the detection of the SH group in released Coenzyme A is in progress. Since other drugs against PG biosynthesis often result in uncontrolled hydrolysis of the peptidoglycan and subsequent cell lysis it can be hoped a similar affect might occur with inhibitors of GlmU.

There are, in addition, some aspects of PG synthesis that are unique to mycobacteria and related organisms that may also have potential in the drug discovery setting. The glycan chains are composed of alternating units of β 1→4 linked GlcNAc and MurNGlyc, whereas, most other bacteria contain N-acetylmuramic acid. The oxidation of the N-acetyl group to N-glycolyl is catalyzed by a recently identified enzyme designated NamH [46]. Although there is no indication that this modification is essential for M. tuberculosis survival, M. smegmatis mutants devoid of namH show increased sensitivity to β-lactams and lysozyme [46]. The free carboxylic acid groups of the A2pm or D-isoglutamic acid residues of mycobacterial PG may be amidated, and some of the free carboxylic groups of the D-isoglutamic acid residues may also be modified by the addition of a glycine residue in peptide linkage [181]. Determination of the importance of these modifications to the survival of the bacillus awaits identification of the enzymes responsible and their biochemical and genetic definition.

Acknowledgments

The McNeil lab gratefully acknowledges the support of the National Institute of Health (AI33706 and AI057836), and the Crick lab by National Institute of Health (AI049151 and AI065357-020010). We also gratefully appreciate the scientific and editorial contributions of Victoria Jones.

ABBREVIATIONS

- TB

Tuberculosis

- PG

Peptidoglycan

- AG

Arabinogalactan

- IPP

Isopentyl diphosphate

- DMAPP

Dimethylallyl diphosphate

- MEP

2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 4-phopshate

- Dec-P

Decaprenyl phosphate

- mAGP

Mycolyl arabinogalactan peptidoglycan

- HTS

High throughput screening

- DXS

1-Deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase

- GAP

Glyceraldehyde-3-phopshate

- DXP

1-Deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate

- UPS

Undecaprenyl diphosphate synthase

- E,Z-FPP

E,Z, farnesyl diphosphate

- LAM

Lipoarabinomannan

- INH

Isoniazid

- CoA

Coenzyme A

- FAS I

Type I fatty acid synthase

- FAS II

Type II fatty acid synthase

- TraSH

Transposon Site Hybridization

REFERENCES

- 1.Projan SJ. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2002;2:513. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(02)00197-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stein J. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 2005;14:107. doi: 10.1517/13543784.14.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talbot GH, Bradley J, Edwards JE, Gilbert D, Scheld M, Bartlett JG. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2006;42:657. doi: 10.1086/499819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mills SD. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2006;71:1096. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Draper P. In: The Biology of Mycobacteria. Ratledge C, Sanford J, editors. I. London: Academic Press; 1982. pp. 9–52. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petit JF, Lederer E. In: The Mycobacteria, a Sourcebook. Kubica GP, Wayne LG, editors. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1984. pp. 301–322. [Google Scholar]

- 7.McNeil M, Brennan PJ. Res. Microbiol. 1991;142:451. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(91)90120-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takayama K, Wang C, Besra GS. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2005;18:81. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.1.81-101.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barry CE, III, Lee RE, Mdluli K, Sampson AE, Schroeder BG, Slayden RA, Yuan Y. Prog. Lipid Res. 1998;37:143. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(98)00008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee A, Khoo K-H, Wu S, Scherman M, Torrelles J, Chatterjee D, McNeil MR. Biochemistry in Press. 2007 doi: 10.1021/bi060688d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Besra GS, Khoo K-H, McNeil M, Dell A, Morris HR, Brennan PJ. Biochemistry. 1995;34:4257. doi: 10.1021/bi00013a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alderwick LJ, Radmacher E, Seidel M, Gande R, Hitchen PG, Morris HR, Dell A, Sahm H, Eggeling L, Besra GS. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:32362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506339200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daffe M, Brennan PJ, McNeil M. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:6734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McNeil M, Daffe M, Brennan PJ. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:18200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winder FG. In: The Biology of the Mycobacteria. Ratledge C, Standford J, editors. Vol. 1. London: Academic Press; 1982. pp. 354–442. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takayama K, Kilburn JO. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1493. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.9.1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jarlier V, Gutmann L, Nikaido H. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1937. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.9.1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mikusova K, Mikus M, Besra G, Hancock I, Brennan PJ. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:7820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rip JW, Rupar CA, Ravi K, Carroll KK. Progress in Lipid Research. 1985;24:269. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(85)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou D, White RH. Biochemical Journal. 1991;273:627. doi: 10.1042/bj2730627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rohmer M, Knani M, Simonin P, Sutter B, Sahm H. Biochemical Journal. 1993;295:517. doi: 10.1042/bj2950517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horbach S, Sahm H, Welle R. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 1993;111:135. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb06375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sprenger GA, Schorken U, Wiegert T, Grolle S, deGraaf AA, Taylor SV, Begley TP, BringerMeyer S, Sahm H. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:12857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.12857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duvold T, Bravo JM, PaleGrosdemange C, Rohmer M. Tetrahedron Letters. 1997;38:4769. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Putra SR, Lois LM, Campos N, Boronat A, Rohmer M. Tetrahedron Letters. 1998;39:23. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lois LM, Campos N, Putra SR, Danielsen K, Rohmer M, Boronat A. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:2105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takayama K, Goldman DS. J. Biol. Chem. 1970;245:6251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahapatra S, Yagi T, Belisle JT, Espinosa BJ, Hill PJ, McNeil MR, Brennan PJ, Crick DC. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:2747. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.8.2747-2757.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Apfel CM, Takacs S, Fountoulakis M, Stieger M, Keck W. Journal of Bacteriology. 1999;181:483. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.2.483-492.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allen CM, Keenan MV, Sack J. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1976;175:236. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(76)90504-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baba T, Allen CM. Biochemistry. 1978;17:5598. doi: 10.1021/bi00619a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muth JD, Allen CM. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1984;230:49. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(84)90085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schulbach MC, Brennan PJ, Crick DC. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:22876. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003194200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schulbach MC, Mahapatra S, Macchia M, Barontini S, Papi C, Minutolo F, Bertini S, Brennan PJ, Crick DC. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:11624. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007168200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaur D, Brennan PJ, Crick DC. Journal of Bacteriology. 2004;186:7564. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.22.7564-7570.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mills JA, Motichka K, Jucker M, Wu HP, Uhlik BC, Stern RJ, Scherman MS, Vissa VD, Pan F, Kundu M, Ma YF, McNeil M. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:43540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407782200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mikusova K, Belanova M, Kordulakova J, Honda K, McNeil MR, Mahapatra S, Crick DC, Brennan PJ. J. Bacteriol. 2006;118:6592. doi: 10.1128/JB.00489-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rose NL, Completo GC, Lin SJ, McNeil M, Palcic MM, Lowary TL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:6721. doi: 10.1021/ja058254d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kremer L, Dover LG, Morehouse C, Hitchin P, Everett M, Morris HR, Dell A, Brennan PJ, McNeil MR, Flaherty C, Duncan K, Besra GS. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:26430. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102022200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mikusova K, Yagi T, Stern R, McNeil MR, Besra GS, Crick DC, Brennan PJ. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:33890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006875200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alderwick LJ, Seidel M, Sahm H, Besra GS, Eggeling L. J. Biol. Chem. 2006 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600045200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Belanger AE, Besra GS, Ford ME, Mikusova K, Belisle J, Brennan PJ, Inamine JM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:11919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang N, Torrelles JB, McNeil MR, Escuyer VE, Khoo KH, Brennan PJ, Chatterjee D. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;50:69. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Escuyer VE, Lety MA, Torrelles JB, Khoo KH, Tang JB, Rithner CD, Frehel C, McNeil MR, Brennan PJ, Chatterjee D. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:48854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102272200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seidel M, Alderwick LJ, Birch HL, Sahm H, Eggeling L, Besra GS. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700271200. M700271200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raymond JB, Mahapatra S, Crick DC, Pavelka MS. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuzuyama T, Takagi M, Takahashi S, Seto H. Journal of Bacteriology. 2000;182:891. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.4.891-897.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cane DE, Chow C, Lillo A, Kang I. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 2001;9:1467. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hahn FM, Eubanks LM, Testa CA, Blagg BSJ, Baker JA, Poulter CD. Journal of Bacteriology. 2001;183:1. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.1.1-11.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Altincicek B, Hintz M, Sanderbrand S, Wiesner J, Beck E, Jomaa H. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2000;190:329. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miller B, Heuser T, Zimmer W. FEBS Letters. 1999;460:485. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01397-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bouvier F, d’Harlingue A, Suire C, Backhaus RA, Camara B. Plant Physiology. 1998;117:1423. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.4.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Estevez JM, Cantero A, Romero C, Kawaide H, Jimenez LF, Kuzuyama T, Seto H, Kamiya Y, Leon P. Plant Physiology. 2000;124:95. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lange BM, Wildung MR, McCaskill D, Croteau R. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:2100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bailey AM, Mahapatra S, Brennan PJ, Crick DC. Glycobiology. 2000;10:46. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bailey AM, Mahapatra S, Brennan PJ, Crick DC. Unpublished data. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xiang S, Usunow G, Lange G, Busch M, Tong L. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282:2676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610235200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dhiman RK, Schaeffer ML, Bailey AM, Testa CA, Scherman H, Crick DC. Journal of Bacteriology. 2005;187:8395. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.24.8395-8402.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grolle S, Bringer-Meyer S, Sahm H. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2000;191:131. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Koppisch AT, Fox DT, Blagg BSJ, Poulter CD. Biochemistry. 2002;41:236. doi: 10.1021/bi0118207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kuzuyama T, Takahashi S, Watanabe H, Seto H. Tetrahedron Letters. 1998;39:4509. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Proteau PJ, Woo YH, Williamson RT, Phaosiri C. Organic Letters. 1999;1:921. doi: 10.1021/ol990839n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schwender J, Muller C, Zeidler J, Lichlenthaler HK. FEBS Letters. 1999;455:140. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00849-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Argyrou A, Blanchard JS. Biochemistry. 2004;43:4375. doi: 10.1021/bi049974k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mac Sweeney A, Lange R, Fernandes RPM, Schulz H, Dale GE, Douangamath A, Proteau PJ, Oefner C. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2005;345:115. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reuter K, Sanderbrand S, Jomaa H, Wiesner J, Steinbrecher I, Beck E, Hintz M, Klebe G, Stubbs MT. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:5378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109500200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ricagno S, Grolle S, Bringer-Meyer S, Sahm H, Lindqvist Y, Schneider G. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta-Proteins and Proteomics. 2004;1698:37. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Steinbacher S, Kaiser J, Eisenreich W, Huber R, Bacher A, Rohdich F. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:18401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300993200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yajima S, Hara K, Sanders JM, Yin FL, Ohsawa K, Wiesner J, Jomaa H, Oldfield E. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2004;126:10824. doi: 10.1021/ja040126m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yajima S, Nonaka T, Kuzuyama T, Seto H, Ohsawa K. Journal of Biochemistry. 2002;131:313. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a003105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sassetti CM, Boyd DH, Rubin EJ. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;48:77. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kuzuyama T, Shimizu T, Takahashi S, Seto H. Tetrahedron Letters. 1998;39:7913. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zeidler J, Schwender J, Muller C, Wiesner J, Weidemeyer C, Beck E, Jomaa H, Lichtenthaler HK. Zeitschrift fur Naturforschung C-A Journal of Biosciences. 1998;53:980. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jomaa H, Wiesner J, Sanderbrand S, Altincicek B, Weidemeyer C, Hintz M, Turbachova I, Eberl M, Zeidler J, Lichtenthaler HK, Soldati D, Beck E. Science. 1999;285:1573. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5433.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mueller C, Schwender J, Zeidler J, Lichtenthaler HK. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2000;28:792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Herz S, Wungsintaweekul J, Schuhr CA, Hecht S, Luttgen H, Sagner S, Fellermeier M, Eisenreich W, Zenk MH, Bacher A, Rohdich F. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:2486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040554697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Luttgen H, Rohdich F, Herz S, Wungsintaweekul J, Hecht S, Schuhr CA, Fellermeier M, Sagner S, Zenk MH, Bacher A, Eisenreich W. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:1062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rohdich F, Wungsintaweekul J, Fellermeier M, Sagner S, Herz S, Kis K, Eisenreich W, Bacher A, Zenk MH. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:11758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.11758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rohdich F, Kis K, Bacher A, Eisenreich W. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2001;5:535. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rohdich F, Zepeck F, Adam P, Hecht S, Kaiser J, Laupitz R, Grawert T, Amslinger S, Eisenreich W, Bacher A, Arigoni D. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:1586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337742100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Miallau L, Alphey MS, Kemp LE, Leonard GA, McSweeney SM, Hecht S, Bacher A, Eisenreich W, Rohdich F, Hunter WN. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:9173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533425100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wada T, Kuzuyama T, Satoh S, Kuramitsu S, Yokoyama S, Unzai S, Tame JRH, Park SY. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:30022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304339200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shimizu N, Koyama T, Ogura K. Journal of Bacteriology. 1998;180:1578. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.6.1578-1581.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shridas P, Rush JS, Waechter CJ. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2003;312:1349. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Scherman MS, Winans K, Bertozzi CR, Stern R, Jones VC, McNeil MR. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003;47:378. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.1.378-382.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ma Y, Stern RJ, Scherman MS, Vissa V, Yan W, Jones VC, Zhang F, Franzblau SG, Lewis WH, McNeil MR. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001;45:1407. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.5.1407-1416.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stern RJ, Lee TY, Lee TJ, Yan W, Scherman MS, Vissa VD, Kim SK, Wanner BL, McNeil MR. Microbiology. 1999;145:663. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-3-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Weston A, Stern RJ, Lee RE, Nassau PM, Monsey D, Martin SL, Scherman MS, Besra GS, Duncan K, McNeil MR. Tuber. Lung Dis. 1998;78:123. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8479(98)80005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ma Y, Mills JA, Belisle JT, Vissa V, Howell M, Bowlin K, Scherman MS, McNeil M. Microbiology. 1997;143:937. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-3-937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lee R, Monsey D, Weston A, Duncan K, Rithner C, McNeil M. Anal. Biochem. 1996;242:1. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Li W, Xin Y, McNeil MR, Ma Y. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;342:170. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ma Y, Pan F, McNeil MR. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:3392. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.12.3392-3395.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pan F, Jackson M, Ma Y, McNeil MR. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183:3991. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.13.3991-3998.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Beis K, Srikannathasan V, Liu H, Fullerton SWB, Bamford VA, Sanders DAR, Whitfield C, McNeil MR, Naismith JH. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2005;348:971. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.02.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Blankenfeldt W, Kerr ID, Giraud MF, McMiken HJ, Leonard G, Whitfield C, Messner P, Graninger M, Naismith JH. Structure. (Camb. ) 2002;10:773. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00770-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Allard STM, Giraud MF, Whitfield C, Graninger M, Messner P, Naismith JH. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2001;307:283. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sanders DR, Steins AG, McMahon SA, McNeil MR, Whitfield C, Naismith JH. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001;8:858. doi: 10.1038/nsb1001-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Allard STM, Giraud M-F, Whitfield C, Messner P, Naismith JH. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2000;56(Pt 2):222. doi: 10.1107/s0907444999016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Blankenfeldt W, Asuncion M, Lam JS, Naismith JH. Embo Journal. 2000;19:6652. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.24.6652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Giraud M-F, Leonard GA, Field RA, Berlind C, Naismith JH. Nature Struct. Biol. 2000;7:398. doi: 10.1038/75178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dong C, Major LL, Srikannathasan V, Errey JC, Giraud MF, Lam JS, Graninger M, Messner P, McNeil MR, Field RA, Whitfield C, Naismith JH. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;365:146. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Carlson EE, May JF, Kiessling LL. Chemistry & Biology. 2006;13:825. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Soltero-Higgin M, Carlson EE, Phillips JH, Kiessling LL. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2004;126:10532. doi: 10.1021/ja048017v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Imperiali B, Zimmerman JW. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:6485. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gosselin S, Alhussaini M, Streiff MB, Takabayashi K, Palcic MM. Anal. Biochem. 1994;220:92. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Marlow AL, Kiessling LL. Organic Letters. 2001;3:2517. doi: 10.1021/ol016170d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Errey JC, Mukhopadhyay B, Kartha KPR, Field RA. Chemical Communications. 2004:2706. doi: 10.1039/b410184g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Pathak AK, Pathak V, Seitz L, Maddry JA, Gurcha SS, Besra GS, Suling WJ, Reynolds RC. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2001;9:3129. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Liav A, Huang HR, Ciepichal E, Brennan PJ, McNeil MR. Tetrahedron Letters. 2006;47:545. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Pathak AK, Pathak V, Maddry JA, Suling WJ, Gurcha SS, Besra GS, Reynolds RC. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2001;9:3145. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00180-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lee RE, Brennan PJ, Besra GS. Glycobiology. 1997;7:1121. doi: 10.1093/glycob/7.8.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Khasnobis S, Zhang J, Angala SK, Amin AG, McNeil MR, Crick DC, Chatterjee D. Chem. Biol. 2006;13:787. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]