Abstract

Objective: To investigate the correlation between spiritual beliefs and depression in an urban population.

Method: A convenience sample of adult patients of an urban primary care clinic completed a self-administered questionnaire consisting of the Zung Depression Scale and the Spiritual Involvement and Beliefs Scale (SIBS).

Results: Among 122 respondents, 99 (81%) reported that they consider themselves religious. Responses from the Zung Depression Scale found that 76 (62%) of the patients were depressed and 46 (38%) were not. The Pearson correlation coefficient between the Zung Depression Scale and the SIBS was −0.36 (p < .0001). Backward stepwise regression analysis revealed that SIBS score and physical health predicted the Zung Depression Scale score. Age, gender, ethnicity, religious affiliation, and income showed no significant association with depression. Analysis of individual SIBS items revealed that high spirituality scores on items in the domain of intrinsic beliefs, such as belief in a higher power (p < .01), the importance of prayer (p < .0001), and finding meaning in times of hardship (p < .05), were associated negatively with depression. Attendance of religious services had no significant association with depression.

Conclusion: Appropriate encouragement of a patient's spiritual beliefs may be a helpful adjunct to treating depression.

Depression is a common diagnosis in primary care practices, accounting for 6% to 20% of all patient visits.1–3 Similarly, spiritual attitudes greatly influence patients' approach to medical care. A nationwide survey in 1990 found that 75% of the population reports that their approach to life is grounded in their faith.4 In a study of patients in a primary care setting, 40% of patients wish that their doctors would discuss their faith with them.5

Several studies have shown a positive association between religious commitment and mental health. In a meta-analysis, Larson et al.6 pooled all of the studies pertaining to spirituality and mental health over an 11-year period from 2 leading psychiatric journals. In the review, 84% of the studies showed a positive association between spiritual attitudes and mental health, 13.5% of the studies showed no statistical association, and 2.5% of the studies showed a negative association. Various aspects of spirituality have been associated with a lower prevalence of depression in a wide variety of specific populations, including college students,7 the elderly,8,9 disabled veterans,10 and women recovering from hip fractures.11 This association extends beyond simple survey results to depressive behaviors; a survey in Washington County, Md., showed that people who did not attend religious services were 4 times as likely to commit suicide than those who attended church regularly.12

Despite the variety of these studies, there have been few studies correlating depression and spirituality among the urban poor. Given the stressors present in many urban communities, such as increased rates of poverty, crime, and chronic illness, a patient's spiritual life could be an important coping mechanism, especially when other support systems are limited.13–16 Many prior studies emphasize church attendance and belief in a higher power as measures of spirituality.7–10,12,17 However, in addition to church attendance, other qualities have been recognized as important to one's spirituality: an “inner life” of prayer and meditation, attitudes toward other people, and belief in a relationship with a higher power. The present study was undertaken to better understand the association between depression and spirituality in urban patients in order to provide insight into this important coping mechanism.

METHOD

Design, Participants, and Setting

The potential association between spiritual beliefs and depressive symptoms in an urban population was investigated by administering a written questionnaire to a convenience sample of patients older than 18 years in the waiting room at a multispecialty primary care clinic in Waterbury, Conn. Participation was voluntary, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Any identifying information was removed and stored separately from questionnaire data. Only subjects who fully completed the study instruments were included in the final data analysis. The study design and materials were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at St. Mary's Hospital (Waterbury, Conn.), an affiliate of the Yale Primary Care Internal Medicine Residency Program.

Survey Instrument

The questionnaire was composed of 2 previously validated scales: the Zung Depression Scale18 and the Spiritual Involvement and Beliefs Scale (SIBS).19 The Zung Depression Scale is a self-administered form with 20 questions addressing the presence of symptoms such as hopelessness, helplessness, and anhedonia. The instrument is scored on an ordinal scale, and a high composite score has a strong correlation with the diagnosis of depression.20 Comparison between the Zung Depression Scale score and DSM-III criteria revealed a sensitivity of 97%, a specificity of 63%, a positive predictive value of 77%, and a negative predictive value of 95%.20 Furthermore, previous studies have established morbidity cutoff scores as a guide in determining the clinical severity of depressive symptoms (i.e., no depression or mild, moderate, or severe symptoms).21

Spirituality was assessed using the SIBS.19 This scale, developed by Hatch et al. in 1998, queries various aspects of spirituality using language that is not exclusive to the Judeo-Christian tradition.8,19,22,23 The SIBS consists of 26 questions scored on a 5-point ordinal scale (strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, or strongly disagree). Factor analysis identified 4 loosely specific domains: (1) internal beliefs, (2) external practices, (3) personal application such as practicing humility and forgiveness toward other people, and (4) existential and meditative beliefs.19 Internal beliefs are assessed with items such as, “I can find meaning in times of hardship.” External practices are categorized with statements such as, “During the last month, I participated in spiritual activities with at least one other person (0 times, 1–5 times, etc.).” Humility and forgiveness are assessed with statements such as, “When I wrong someone, I make an effort to apologize.” Existential and meditative beliefs are investigated using statements such as, “A spiritual force influences my life.” The SIBS is tightly correlated to other instruments in the literature, and since the language used in the scale is not specific to Judeo-Christian terminology,19 it is user-friendly to those who consider themselves “spiritual” but not “religious.”

Overall health was assessed using Dartmouth Primary Care Cooperative Information Functional Health Assessment (COOP) charts.24

Analyses

Completed questionnaires were separated from identifying information and entered into a secure Microsoft Excel database.25 Three statistical methods were used to analyze the data. First, composite scores for the Zung Depression Scale and the SIBS were calculated and compared via the Pearson's correlation coefficient. Second, backward stepwise regression was performed to evaluate the impact of socioeconomic status, demographic variables, and overall physical health. A p value greater than .25 was used for removal. Third, each item of the SIBS scale was compared to a patient's depression score. Scores of high spirituality, “strongly agree” or “agree” in a positively phrased item, were compared with pooled neutral and low spirituality scores. Chi-square analysis was used to determine significance between the number of depressed and nondepressed patients for the possible responses for each SIBS item. Analyses were conducted using JMP4 Statistical Software.26

RESULTS

Three hundred four questionnaires were distributed to patients in the waiting room. Of these, 122 (40%) were returned with each item in the instrument completed. In nearly every case, participants who were called for their appointment prior to completing the instrument handed in an incomplete instrument. There were no significant demographic differences between those who completed and those who did not complete the instrument.

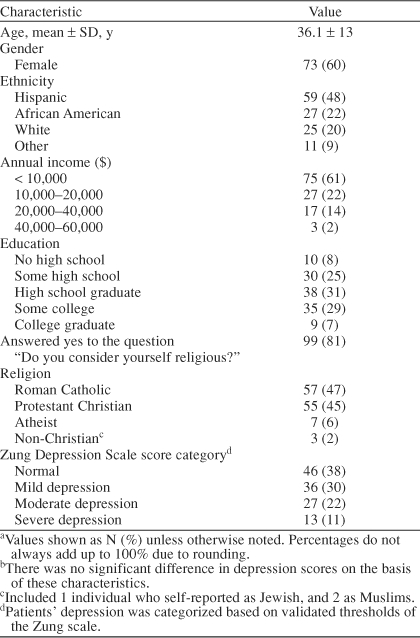

Table 1 shows demographic information for the respondent population of those who fully completed the instrument. Our respondents were from several ethnic groups and tended to be Roman Catholic or Protestant Christian. When asked the yes/no question, “Do you consider yourself religious?” 81% answered in the affirmative. The high prevalence of income of under $10,000/year and lack of graduation from high school is representative of the patient population of the clinic.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of 122 Survey Respondents in an Urban Clinica,b

The prevalence of depressive symptoms in the participant population, based on responses on the Zung Depression Scale, was higher than the U.S. national average of 6% to 20%.1–3 Of 122 participants with complete questionnaires, 46 (38%) had scores in the normal range, 36 (30%) had mild symptoms, 27 (22%) had moderate depressive symptoms, and 13 (11%) had severe symptoms (Table 1).

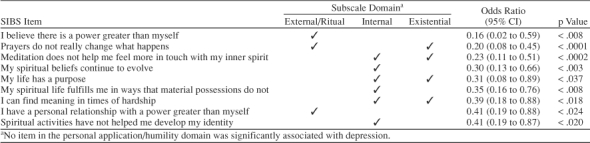

The Pearson correlation coefficient between responses on the Zung Depression Scale and the SIBS was −0.36 (p < .0001), suggesting that a higher spirituality index score is associated with a lower depressive symptoms score.18,19 Tables 2 and 3 detail which SIBS items revealed a statistical difference between depressed and nondepressed patients.

Table 2.

Spiritual Involvement and Belief Scale (SIBS) Items With Significant Difference Between Depressed and Nondepressed Patients

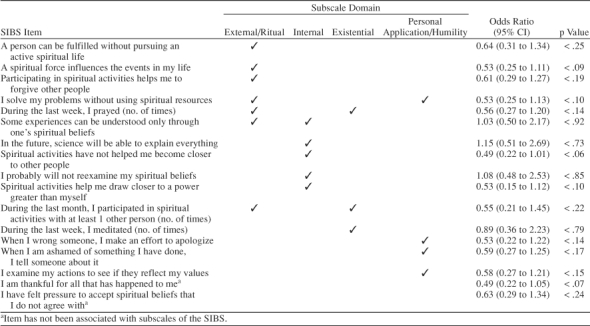

Table 3.

Spiritual Involvement and Belief Scale (SIBS) Items With No Significant Difference Between Depressed and Nondepressed Patients

The negative correlation observed seems driven by certain key items on the SIBS, which are grouped in the subscale domain of “internal” spirituality (Table 2). For example, SIBS items significantly associated with fewer depressive symptoms included “I can find meaning in times of hardship” (p < .018) and “My life has a purpose” (p < .037). Also, 2 variables from the “external/ritual belief” domain revealed the strongest odds ratios against depression. “I believe there is a power greater than myself” (p < .008) revealed an odds ratio of 0.16 (95% CI = 0.02 to 0.59), which suggests that those who scored this variable highly were more than 6 times less likely to be depressed. Those with a high spirituality score (those who responded “disagree” or “strongly disagree”19) for the variable “Prayers do not really change what happens” (p < .0001) were 5 times less likely to be depressed. These data suggest that a person's belief systems—in particular, a belief in a higher power and in the importance of prayer—are associated with not being depressed.

In contrast, items pertaining to certain “external” religious practices were not associated with any particular Zung Depression Scale score (Table 3): “During the last week, I prayed (≥ 10, 7–9, 4–6, 1–3) times” (p < .14); “During the last week, I meditated (≥ 10, 7–9, 4–6, 1–3) times” (p < .791); “During the last month, I participated in spiritual activities with at least one other person (> 15, 11–15, 6–10, 1–5, 0) times” (p < .22). The quantity of one's religious practices appears less important than the quality.

Furthermore, the relational qualities of spirituality—humility and personal application—were not significantly associated with a lack of depressive symptoms. These items include “When I wrong someone, I make an effort to apologize” (p < .143) and “When I am ashamed of something I have done, I tell someone about it” (p < .173).

The final backward stepwise regression model included the SIBS (p < .0002) and overall health (p < .0001) as significant variables influencing depression. The overall regression coefficient (R2) was 0.38, indicating that more than one third of the variability in the data can be explained by the model. While gender, age, income, education, and religion affiliation were not statistically significant, they were not adequately powered. While patients with poorer physical health were more depressed, this association did not affect the significance of the association between depression and spirituality.

DISCUSSION

In our poor, urban, multiethnic sample, as in previous studies,7–12,17 higher overall spirituality scores correlated with fewer depressive symptoms. However, in contrast with previous studies of middle-class populations in which church attendance predicted against depression,7–10,12,17 quantity of prayer and attendance of religious services did not make a difference in depressive symptoms in this sample.

This study raises several provocative questions. Belief in a higher power, a purpose in one's life, or the power of prayer may protect a person from depression—especially given the potentially overwhelming social stressors associated with life in the inner city. However, lack of faith may merely be another symptom of the “helplessness, hopelessness, anhedonia” that characterize clinical depression. Although it may be tempting to ascribe a causal relationship between spirituality and depression, these data are associational only.

In many studies, a person's attendance of worship services has been found to predict against depression.7–10,12,17 The church's social support has been postulated as a reason why churchgoers are less depressed.9,10,12 However, a selection bias may cloud this association: depressed patients may be too debilitated to attend religious services. Among our population, however, there was no association between attendance of religious services and depressive symptoms. Depressed individuals were just as likely to attend religious services, to pray, and to meditate as nondepressed individuals. Is the impact of the church community not enough to mitigate depression given the stressors of the inner city? Does the church function as a sanctuary for the depressed and nondepressed alike? Is there a certain quality, rather than quantity, of worship, prayer, or meditation that is more effective in alleviating depression? Further study in this arena may answer many of these questions.

Nonetheless, among impoverished patients, whose life pressures can be severe13–16 and depression levels high, encouraging appropriate involvement in spiritual activities or incorporating religious imagery into a therapeutic regimen may have a benefit. The success of identifying a “higher power” in 12-step programs for the treatment of alcoholism and narcotic addiction suggests that incorporating spiritual language may have a benefit. Membership in Alcoholics Anonymous enables 60% to 80% of alcoholics to drink less or not at all for up to a year, and 40% to 50% achieve sobriety for many years.27 In a 1981 study, patients suffering from opioid addiction who used religious imagery and language had improved rates of abstinence at 1 year compared with those who did not use religious imagery (41% vs. 5%).28

Among patients who are religious, 2 studies suggest that incorporating religious belief in the therapy of depressed patients results in improved depression scores when compared with treating patients conventionally.29,30 However, 3 studies have shown no difference in using religious imagery as an adjunctive to therapy for depressed patients.31–33 An appropriate study remains to be conducted among the urban poor.

This study has several potential limitations. The 40% completion rate raises a concern for possible selection bias expressed in participant refusal. Yet, review of the partially completed questionnaires revealed that the last remaining items were usually left unanswered, suggesting that failure to complete the survey was due to the arrival of appointment times for patients in the waiting room; this was confirmed by repeated reports from patients. Also, the criterion for inclusion of questionnaires in the analysis was rigorous: the instrument had to be completely filled out to be included in the data analysis. Upon review of the demographic data, there was no statistical difference between patients who completed and patients who did not complete the questionnaire (data not shown). The rate of return may also have been hindered by low education levels and high levels of depression, which might lead to a low reading speed.

In summary, this study surveyed an urban population and found that higher spirituality scores correlated with fewer depressive symptoms. In particular, belief in a higher power, having a relationship with a higher power, and belief in prayer showed significant difference between depressed and nondepressed individuals. Finding patient-sensitive ways to encourage patients' intrinsic belief system may benefit their depressive symptoms. Further, understanding a patient's spiritual life, and its impact on mental health, gives care providers insight into a significant coping mechanism. This remains an exciting arena of research where the interrelationship among spirituality, medicine, and mental health may find common ground to incorporate a new modality in the care of our impoverished, depressed patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Stephen Huot, M.D.; Jeffrey Stein, M.D.; and Caroline Kim, M.D., M.P.H., for their support and guidance during this project.

Footnotes

Funding was provided by an internal grant from the Yale University Program in Primary Care Internal Medicine for resident research projects.

REFERENCES

- Barry KL, Fleming MF, and Manwell LB. et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with current and lifetime depression in older adult primary care patients. Fam Med. 1998 30:366–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, Von Korff M. Recognition, management, and outcomes of depression in primary care. Arch Fam Med. 1995;4:99–105. doi: 10.1001/archfami.4.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson C, Civic D, Glass D. Prevalence and correlates of depressive syndromes among adults visiting an Indian Health Service primary care clinic. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 1995;6:1–12. doi: 10.5820/aian.0602.1995.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begin AE, Jensen JP. Religiosity and psychotherapists: a national survey. Psychotherapy. 1990;27:3–7. [Google Scholar]

- King DE, Bushwick B. Beliefs and attitudes of hospital patients about faith healing and prayer. J Fam Pract. 1994;39:349–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson DB, Sherrill KA, and Lyons JS. et al. Associations between dimensions of religious commitment and mental health reported in American Journal of Psychiatry and the Archives of General Psychiatry: 1978–1989. Am J Psychiatry. 1992 149:557–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehring RJ, Brennan PF, Keller ML. Psychological and spiritual well-being in college students. Res Nurs Health. 1987;10:391–398. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770100607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman DM, Kasl SV, Ostfeld AM. Psychosocial predictors of mortality among the elderly poor: the role of religion, well-being, and social contacts. Am J Epidemiol. 1984;119:410–423. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL. Religious involvement and the health of the elderly: some hypotheses and an initial test. Soc Forces. 1987;66:226–238. [Google Scholar]

- Miller JF. Assessment of loneliness and spiritual well-being in chronically ill and healthy adults. J Prof Nurs. 1985;2:45–49. doi: 10.1016/s8755-7223(85)80010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pressman P, Lyons JS, and Larson DB. et al. Religious belief, depression, and ambulation status in elderly women with broken hips. Am J Psychiatry. 1990 147:758–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comstock GW. Church attendance and health. J Chronic Dis. 1972;25:665–672. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(72)90002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowle S, Steward-Brown S. Deprivation and health: deprivation contributes to chronic illness [letter] BMJ. 1994;308:203–204. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6922.203c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis G, Sloggett A. Suicide, deprivation, and unemployment: record linkage study. BMJ. 1998;37:1283–1286. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7168.1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes R, Gale S. Mortality, long-term illness and deprivation in rural and metropolitan wards of England and Wales. Health Place. 1999;5:301–312. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(99)00020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newacheck PW. Poverty and childhood chronic illness. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1994;148:1143–1149. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1994.02170110029005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stack S. The effect of the decline in institutionalized religion on suicide: 1954–1978. J Sci Study Relig. 1983;22:239–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zung WK. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63–70. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01720310065008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch RL, Burg MA, and Naberhaus DS. et al. The Spiritual Involvement and Beliefs Scale: development and testing of a new instrument. J Fam Pract. 1998 46:476–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zung WWK, Magruder-Habib K, and Velez R. et al. The comorbidity of anxiety and depression in general medical patients: a longitudinal study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990 51(suppl 6):77–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zung WWK. The role of rating scales in the identification and management of the depressed patient in the primary care setting. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51(suppl 6):72–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paloutzian R, Ellison C. Loneliness, spiritual well-being and the quality of life. In: Peplau LA, ed. Loneliness: A Sourcebook of Current Theory, Research, and Therapy. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. 1982 224–237. [Google Scholar]

- Allport GW, Ross JM. Personal religious orientation and prejudice. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1967;5:432–433. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.5.4.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson EC, Wasson J, and Kirk J. et al. Assessment of function in routine clinical practice: description of the COOP Chart method and preliminary findings. J Chronic Dis. 1987 40(suppl 1):55S–69S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Microsoft Excel [computer, program] Redmond, Wash: Microsoft Corporation. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- JMP Statistical Software [computer, program] Version 4.04. Cary, NC: SAS Institute. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Emrick CD, Tonigan JS, and Montgomery H. et al. Alcoholics Anonymous: what is currently known? In: McCrady BS, Miller WR. Research on Alcoholics Anonymous: Opportunities and Alternatives. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Center for Alcohol Studies. 1993 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Desmond M. Religious programs and careers. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1981;8:71–83. doi: 10.3109/00952998109016919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Propst LR, Ostrom R, and Watkins P. et al. Comparative efficacy of religious and nonreligious cognitive-behavioral therapy for the treatment of clinical depression in religious individuals. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992 60:94–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Propst LR. The comparative efficacy of religious and non religious imagery for the treatment of mild depression in religious individuals. Cogn Ther Res. 1980;4:167–178. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson WB, Ridley CR. Brief Christian and non-Christian rational-emotive therapy with depressed Christian clients: an exploratory study. Couns Values. 1992;36:220–229. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson WB, Devries R, and Ridley CR. et al. The comparative efficacy of Christian and secular rational-emotive therapy with Christian clients. J Psychol Theol. 1994 22:130–140. [Google Scholar]

- Pecheru D, Edwards KJ. A comparison of secular and religious versions of cognitive therapy with depressed Christian college students. J Psychol Theol. 1984;12:45–54. [Google Scholar]