Abstract

Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) is an enzyme key regulator in folate metabolism. Deficiencies in MTHFR result in increased levels of homocysteine, which leads to reduced levels of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM). In the brain, SAM donates methyl groups to catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT), which is involved in neurotransmitter analysis. Using the MTHFR-deficient mouse model the purpose of this study was to investigate levels of monoamine neurotransmitters and amino acid levels in brain tissue. MTHFR deficiency affected levels of both glutamate and γ-aminobutyric acid in within the cerebellum and hippocampus. Mthfr−/− mice had reduced levels of glutamate in the amygdala and γ-aminobutyric acid in the thalamus. The excitatory mechanisms of homocysteine through activation of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor in brain tissue might alter levels of glutamate and γ-aminobutyric acid.

Abbreviations: 5-HIAA, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid; 5-methylTHF, 5-methyltetrahydrofolate; COMT, catechol-O-methyltransferase; HPLC, high performance liquid chromatography; MTHFR, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; SAM, S-adenosylmethionine; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; DOPAC, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid; HVA, homovanillic acid; 5-HT, serotonin.

Keywords: Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, S-Adenosylmethionine, Homocysteine, Monoamine neurotransmitters, Glutamate, γ-Aminobutyric acid

1. Introduction

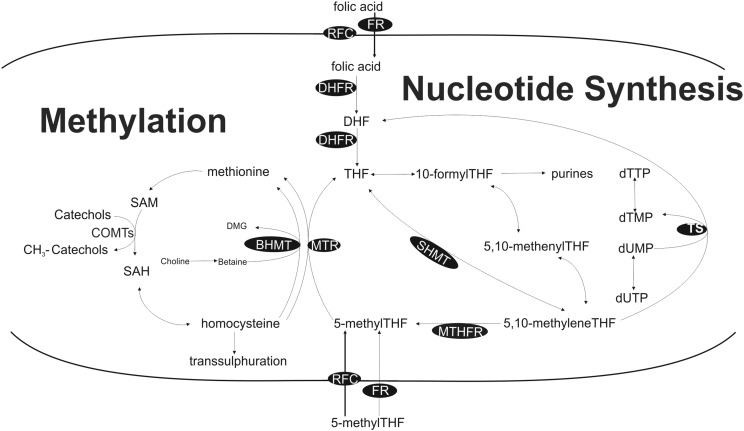

Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) is an important enzyme in folate metabolism since it generates the main circulating form of folate, 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (5-methylTHF), which can serve as a methyl donor for the remethylation of homocysteine to methionine and subsequently the generation of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) (Fig. 1). Through methylation SAM is involved in lipid metabolism and also donates a methyl group to catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT), which catalyzes synthesis of neurotransmitters in the brain [1], [2]. Increased levels of homocysteine, as a result of folate deficiency, have been linked to low levels of monoamine neurotransmitter levels in patients with depression [3].

Fig. 1.

One-carbon metabolism and related biological roles (methylation and nucleotide synthesis). Enzymes indicated in black circles. Abbreviations: BHMT — betaine homocysteine methyltransferase; CHDH — choline dehydrogenase; COMT — catechol-O-methyltransferase; DHFR — dihydrofolate reductase; dTMP — deoxythymidine monophosphate; dTTP — deoxythymidine triphosphate; dUMP — deoxyuridine monophosphate; dUTP — deoxyuridine triphosphate; FR — folate receptor; MTHFR — methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; MTR — methionine synthase; MTRR — methionine synthase reductase; RFC — reduced folate carrier; SAM — S-adenosylmethionine; SAH S-adenosylhomocysteine; and TS — thymidylate synthase.

Many polymorphisms of MTHFR have been described in the human population and the most common is a polymorphism at base pair 677, a conversion from C to T which results in a missense mutation causing an alanine to valine conversion [4]. Homozygosity has been reported in 5–20% of North American and European populations [5]. These individuals have reduced enzyme activity (heterozygotes 65% and homozygotes 30% compared to controls [6]) and slightly elevated levels of plasma homocysteine, which is highly dependent on folate status [5], [7]. Individuals with the TT genotype have increased risk of developing cognitive impairment [8], late onset Alzheimer's disease [9], as well as depression and schizophrenia [10]. Another condition involved in MTHFR deficiency is an inborn error of metabolism, which results in a severe deficiency in the enzyme and leads to homocystinuria. Patients with a severe MTHFR deficiency have significantly elevated levels of homocysteine and reduced levels of methionine and present with neurological and vascular complications [11], [12], [13].

In order to investigate the effects of MTHFR deficiency on neurological function in vivo, a knockout mouse model for MTHFR was developed, Mthfr+/− and Mthfr−/− mice have elevated levels of plasma homocysteine [14]. Mthfr+/− mice model the polymorphism at base pair 677, as they have elevated levels of plasma homocysteine when compared to wildtype mice but are phenotypically normal. Whereas Mthfr−/− mice model the severe form of MTHFR deficiency, these mice have significantly elevated levels of homocysteine and have motor and cognitive impairments [15]. In brain tissue, both Mthfr+/− and Mthfr−/− mice have significantly reduced levels of DNA methylation and S-adenosylhomocysteine [14] and Mthfr−/− mice have reduced levels of 5-methylTHF [14], [16] and SAM [14]. Additionally, behavioral studies have reported impairments in cognitive and motor function [15], [17]. The purpose of this study was to investigate whether levels of monoamine neurotransmitters and amino acids are altered in different brain regions of MTHFR-deficient mice.

2. Materials and methods

All experiments were approved by the Landesamt für Gesundtheit und Soziales Berlin and performed in accordance with the German Animal Welfare Act. At 3-months of age blood and brain tissue from C57BL/6 male mice was collected and processed for post-mortem neurochemical analyses using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as described previously [18]. The levels of dopamine, serotonin, and their metabolites dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) in the amygdala, caudate putamen, cerebellum, dorsal raphe, hippocampus, medial prefrontal cortex, nucleus accumbens, and thalamus, amygdalae were measured by HPLC with electrochemical detection. Glutamate and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) were determined by HPLC with fluorescence detection. We worked with male mice in this study to avoid sex differences that have been previously described in MTHFR mice [19] and neurotransmitter analysis [20].

Blood samples taken from the same mice were centrifuged at 7000 ×g for 7 min at 4 °C to obtain the plasma. HPLC was used to measure plasma homocysteine concentrations by a diagnostic laboratory at Charite University Medicine (Labor 28, Berlin).

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare genotype groups for each measurement followed by Tukey's post-hoc test if applicable. Significance level was set at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

Mthfr+/− and Mthfr−/− had significantly higher plasma homocysteine levels when compared to Mthfr+/+ mice (Table 1, p < 0.05).

Table 1.

Plasma homocysteine concentrations and quantification of neurotransmitters and amino acids in different brain regions of Mthfr+/+, Mthfr+/− and Mthfr−/− mice1.

|

Mthfr+/+ |

Mthfr+/− |

Mthfr−/− |

p value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma homocysteine (μM) |

8.2 ± 0.8 |

13.6 ± 1.4 |

71.1 ± 6.9 |

*b, c |

| Brain area & neurotransmitter (μMol/g protein) | ||||

| Amygdala | ||||

| Dopamine | 52.6 ± 12.3 | 74.8 ± 20.6 | 46.4 ± 10.5 | NS |

| DOPAC | 7.9 ± 1.7 | 10.1 ± 3.0 | 6.9 ± l.l | NS |

| 5-HT | 57.0 ± 8.1 | 87.0 ± 10.9 | 94.3 ± 10.5 | *c |

| 5-HIAA | 17.2 + 2.0 | 25.9 + 4.0 | 23.6 + 3.5 | NS |

| HVA | 14.9 ± 2.8 | 14.6 ± 2.3 | 10.8 ± l.l | NS |

| Glutamate | 101.4 ± 4.9 | 121.3 ± 5.8 | 113.9 ± 6.2 | *a |

| GABA | 24.7 ± 1.7 | 27.6 ± 3.2 | 27.9 ± 4.0 | NS |

| Caudate putamen | ||||

| Dopamine | 739.8 ± 50.2 | 770.9 ± 30.4 | 728.4 ± 39.5 | NS |

| DOPAC | 46.6 ± 2.5 | 46.9 ± 2.5 | 49.1 ± 4.4 | NS |

| 5-HT | 24.6 ± 2.6 | 16.1 ± 3.2 | 18.7 ± 4.0 | NS |

| 5-HIAA | 10.1 ± 1.4 | 8.2 ± 1.3 | 7.7 ± 1.8 | NS |

| HVA | 55.4 ± 3.1 | 57.2 ± 3.2 | 51.1 ± 3.0 | NS |

| Glutamate | 92.1 ± 3.1 | 93.6 ± 4.8 | 81.2 ± 4.9 | NS |

| GABA | 17.5 ± 0.9 | 17.6 ± 0.4 | 15.6 ± 0.7 | NS |

| Cerebellum | ||||

| Dopamine | 1.3 ± 0.05 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.08 | *a |

| DOPAC | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 3.7 ± 0.8 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | NS |

| 5-HT | 3.8 ± 0.3 | 6.5 ± 1.4 | 5.1 ± 0.72 | NS |

| 5-HIAA | 3.3 ± 0.3 | 5.8 ± 1.0 | 5.1 ± 0.4 | *b |

| HVA | 0.6 ± 0.08 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.05 | NS |

| Glutamate | 69.7 ± 2.2 | 77 ± 2.2 | 68.3 ± 1.9 | *d |

| GABA | 15.3 ± 0.5 | 18.0 ± 0.8 | 18.4 ± 0.8 | *b, c |

| Dorsal raphe | ||||

| Dopamine | 11.5 ± 1.4 | 9.8 ± 1.2 | 9.6 ± 1.2 | NS |

| DOPAC | 5.0 ± 0.7 | 4.3 ± 0.6 | 4.3 ± 0.7 | NS |

| 5-HT | 104.9 ± 20 | 85.3 ± 12.5 | 86.3 ± 15.0 | NS |

| 5-HIAA | 54.2 ± 12.5 | 39.5 ± 6.7 | 35.2 ± 5.7 | NS |

| HVA | 13.9 ± 2.9 | 14.4 ± 2.9 | 8.3 ± 1.6 | NS |

| Glutamate | 67.1 ± 2.2 | 80.5 ± 4.4 | 77.5 ± 9.3 | NS |

| GABA | 33.6 ± 1.7 | 38.6 ± 2.6 | 28.7 ± 3.2 | NS |

| Hippocampus | ||||

| Dopamine | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | NS |

| DOPAC | 5.4 ± 0.9 | 4.0 ± 1.0 | 3.6 ± 0.6 | NS |

| 5-HT | 21.8 ± 1.3 | 21.7 ± 1.0 | 20.1 ± 1.9 | NS |

| 5-HIAA | 19.8 ± 1.2 | 16.2 ± 1.0 | 15.3 ± 1.8 | *a |

| HVA | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.08 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | *d |

| Glutamate | 90.2 ± 2.3 | 81.6 ± 3.5 | 76.0 ± 4.9 | *c |

| GABA | 20.5 ± 1.0 | 18.4 ± l.l | 15.5 ± 1.0 | *c |

| Medial prefrontal cortex | ||||

| Dopamine | 72.2 ± 31.0 | 71.0 ± 23.7 | 74.8 ± 29.2 | NS |

| DOPAC | 9.5 ± 1.8 | 8.4 ± 1.5 | 10.9 ± 2.3 | NS |

| 5-HT | 31.6 ± 3.4 | 41.3 ± 6.7 | 41.8 ± 6.9 | NS |

| 5-HIAA | 17.8 ± 3.3 | 20.1 ± 2.9 | 16.6 ± 3.1 | NS |

| HVA | 12.5 ± 1.8 | 10.5 ± 2.2 | 11.8 ± 1.5 | NS |

| Glutamate | 106.7 ± 7.7 | 121.5 ± 7.5 | 102.4 ± 10.0 | NS |

| GABA | 18.4 ± 1.7 | 21.1 ± 1.7 | 20.7 ± 2.8 | NS |

| Nucleus accumbens | ||||

| Dopamine | 633.0 ± 128.7 | 617.7 ± 171.2 | 1015 ± 115.4 | NS |

| DOPAC | 65.5 ± 12.1 | 56.4 ± 12.8 | 85.4 ± 12.8 | NS |

| 5-HT | 80.2 ± 16.9 | 50.2 ± 9.4 | 111.0 ± 9.2 | NS |

| 5-HIAA | 31.0 ± 6 | 18.5 ± 3.3 | 33.9 ± 5.1 | NS |

| HVA | 81.7 ± 10.2 | 52.3 ± 13.3 | 89.2 ± 6.1 | NS |

| Glutamate | 192.7 ± 24.6 | 147.0 ± 26.5 | 193.0 ± 7.9 | NS |

| GABA | 70.3 ± 6.1 | 56.0 ± 12.0 | 79.5 ± 9.5 | NS |

| Thalamus | ||||

| Dopamine | 11.4 ± 2.7 | 14.9 ± 2.7 | 14.1 ± 3.2 | NS |

| DOPAC | 2.9 ± 0.5 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | NS |

| 5-HT | 33.1 ± 5.4 | 39.5 ± 4.9 | 26.7 ± 3.9 | NS |

| 5-HIAA | 18.1 ± 2.0 | 20.1 ± 3.4 | 14.5 ± 2.5 | NS |

| HVA | 7.3 ± 1.0 | 7.6 ± 0.3 | 6.4 ± 0.4 | NS |

| Glutamate | 97.6 ± 3.4 | 97.8 ± 3.9 | 91.9 ± 5.2 | NS |

| GABA | 21.3 ± l.l | 19.7 ± 1.4 | 15.4 ± 1.2 | *c |

All values are means ± SEM; n = 6–8 per group.

Significant one-way ANOVA.

p < 0.05, Tukey's post-hoc, Mthfr+/+ vs. Mthfr+/−.

p < 0.05, Tukey's post-hoc, Mthfr+/+ vs. Mthfr−/−.

p < 0.05, Tukey's post-hoc, Mthfr+/− vs. Mthfr−/−.

There were few changes in monoamine neurotransmitter levels and respective metabolites. Serotonin levels were increased in Mthfr−/− in the amygdala when compared to Mthfr+/+ mice (Table 1, p < 0.05). Dopamine levels within the cerebellum were different between genotype groups (Table 1, one-way ANOVA, F (2, 23) = 8.45, p < 0.01). 5-HIAA was increased in the cerebellum of Mthfr+/− (Table 1, p < 0.05) and there was a genotype effect in the hippocampus (Table 1, one-way ANOVA, F (2, 21) = 3.35, p < 0.05).

Glutamate levels were different between genotype groups within the amygdala (Table 1, one-way ANOVA, F (2, 21) = 3.45, p < 0.05). Mthfr−/− mice had reduced levels of glutamate in the cerebellum (Table 1, p < 0.05) compared to Mthfr+/− mice, and hippocampus (Table 1, p < 0.05) compared to Mthfr+/+ mice. Cerebellar GABA levels were increased in Mthfr+/− and Mthfr−/− when compared to Mthfr+/+ mice (Table 1, p < 0.05). While, GABA levels were reduced in hippocampus (Table 1, p < 0.05) and thalamus (Table 1, p < 0.05) of Mthfr−/− mice compared to Mthfr+/+.

4. Discussion

Increased levels of plasma homocysteine have been linked to impaired monoamine synthesis as a result of reduced levels of SAM [1]. In the present study using a hyperhomocysteinemic MTHFR-deficient mouse model we investigated levels of the monoamine neurotransmitters, dopamine, 5-HT, and their respective metabolites, as well as the amino acids, glutamate and GABA in different brain areas. We confirmed that Mthfr+/− (~ 14 μM) and Mthfr−/− (~ 70 μM) have significantly elevated levels of plasma homocysteine as previously reported in earlier work [14], [15], [21]. We identified that Mthfr−/− have increased levels of serotonin in the amygdala, whereas Mthfr+/− have increased levels of cerebellar dopamine levels. Levels of 5-HIAA are increased in Mthfr+/− mice in the cerebellum and reduced in the hippocampus of Mthfr+/− and Mthfr−/− mice. Additionally, hippocampal levels of HVA levels were reduced in Mthfr−/− mice. More significantly, in Mthfr+/− and Mthfr−/− mice glutamate and GABA levels were changed in the amygdala, cerebellum, hippocampus and thalamus. Interestingly, when we examined whole brain levels of monoamine neurotransmitter and amino acid levels, no differences between genotype groups were observed (data not shown).

The cerebellum and hippocampus are susceptible to a deficiency in MTHFR as previously described [15], [22], [23], [24]. More specifically, the cerebellum has the highest levels of homocysteine [25], which may make it more vulnerable to damage via homocysteine and change levels of metabolism of dopamine, serotonin and amino acids, specifically glutamate and GABA. Previous work has shown that homocysteine results in stimulation of the glutamate subunit on the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor [26], it may be the increased levels of glutamate and GABA within the cerebellum are to counter the excitatory effects of homocysteine. On the other hand, deficiencies in MTHFR have been shown to impair hippocampal function [15], [24]. There is ongoing neurogenesis within the dentate gyrus during adulthood [27] which may increase the demand for folate. In the present study we identified that glutamate is increased in amygdala and GABA is decreased in the thalamus as a result of severe MTHFR deficiency, this is novel data.

In the present study, a deficiency in MTHFR does not result in significant changes of monoamine neurotransmitter levels in majority of brain areas measured. This could be a result of compensation in Mthfr+/− and Mthfr−/− mice, since the deficiency is present from conception. In the peripheral nervous system, choline metabolism is significantly altered in MTHFR mice [28]. During folate deficiency choline can serve as an alternative methyl donor for remethylation of homocysteine to methionine via betaine S-homocysteine methyltransferase, however this enzyme is not highly expressed in brain tissue [29]. Interestingly, both serotonin and dopamine are also present in the peripheral nervous system. We propose that synthesis of serotonin and dopamine may be compensated in the peripheral nervous system, since previous data has shown that SAM levels are not changed in the liver of Mthfr+/− and Mthfr−/− mice possibly as a result of choline compensation [14].

This study has a number of limitations, the first being that tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) which has been described as the rate limiting step required in the synthesis of monoamine neurotransmitters. Interestingly, BH4 structurally resembles folate and has been described to be reduced in endothelial cells when increased levels of homocysteine are present [30]. An additional study measuring levels of BH4 in brain tissue of MTHFR-deficient mice may be beneficial in understanding how this deficiency affects monoamine neurotransmission. Furthermore, studies measuring more monoamine neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine as well as catechol-A-methyltransferase (COMT) levels in different brain areas may help dissect the effect of MTHFR deficiency, elevated levels of plasma homocysteine and reduced SAM levels on neurotransmitter synthesis in this mouse model. C57Bl/6 mice have previously been shown to be less susceptible to MTHFR deficiency in comparison to BALB/c mice [21], therefore additional studies are may be warranted to investigate levels of monoamine neurotransmitter levels in BALB/c mice.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Rima Rozen (McGill University, Montreal, Canada) for her generous gift of the MTHFR mice. NMJ was funded by the Fonds de recherche du Québec Santé, Canada. FW was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft KFO 247.

Contributor Information

N.M. Jadavji, Email: nafisa.jadavji@charite.de.

F. Wieske, Email: Franziska.Wieske@uniklinikum-dresden.de.

U. Dirnagl, Email: ulrich.dirnagl@charite.de.

C. Winter, Email: Christine.Winter@uniklinikum-dresden.de.

References

- 1.Schatz R.A., Wilens T.E., Sellinger O.Z. Decreased transmethylation of biogenic amines after in vivo elevation of brain S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine. J. Neurochem. 1981;36:1739–1748. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1981.tb00426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiang P., Gordon R., Tal J., Zeng G., Doctor B., Pardhasaradhi K. S-Adenosylmethionine and methylation. FASEB J. 1996;10:471–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bottiglieri T., Laundy M., Crellin R., Toone B.K., Carney M.W.P., Reynolds E.H. Homocysteine, folate, methylation and monoamine metabolism in depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2000;69:228–232. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.69.2.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frosst P., Blom H.J., Milos R., Goyette P., Sheppard C.A., Matthews R.G. A candidate genetic risk factor for vascular disease: a common mutation in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase. Nat. Genet. 1995;10:111–113. doi: 10.1038/ng0595-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacques P.F., Bostom A.G., Williams R.R., Ellison R.C., Eckfeldt J.H., Rosenberg I.H. Relation between folate status, a common mutation in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, and plasma homocysteine concentrations. Circulation. 1996;93:7–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rozen R. Molecular genetic aspects of hyperhomocysteinemia and its relation to folic acid. Clin. Invest. Med. 1996;19:171–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rozen R. Encycl. Med. Genomics Proteomics. Taylor & Francis; 2005. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene polymorphism—clinical implications; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ford A.H., Flicker L., Hankey G.J., Norman P., van Bockxmeer F.M., Almeida O.P. Homocysteine, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T polymorphism and cognitive impairment: the health in men study. Mol. Psychiatry. 2012;17:559–566. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coppedè F., Tannorella P., Pezzini I., Migheli F., Ricci G., Caldarazzo lenco E. Folate, homocysteine, vitamin B12, and polymorphisms of genes participating in one-carbon metabolism in late-onset Alzheimer's disease patients and healthy controls. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2012;17:195–204. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilbody S., Lewis S., Lightfoot T. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) genetic polymorphisms and psychiatric disorders: a HuGE review. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007;165:1–13. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engelbrecht V., Rassek M., Huismann J., Wendel U. MR and proton MR spectroscopy of the brain in hyperhomocysteinemia caused by methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1997;18:536–539. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fattal-Valevski A., Bassan H., Korman S.H., Lerman-Sagie T., Gutman A., Harel S. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency: importance of early diagnosis. J. Child Neurol. 2000;15:539–543. doi: 10.1177/088307380001500808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bishop L., Kanoff R., Charnas L., Krenzel C., Berry S. a, Schimmenti L. a. Severe methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) deficiency: a case report of nonclassical homocystinuria. J. Child Neurol. 2008;23:823–828. doi: 10.1177/0883073808315410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Z., Karaplis A.C., Ackerman S.L., Pogribny I.P., Melnyk S., Lussier-Cacan S. Mice deficient in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase exhibit hyperhomocysteinemia and decreased methylation capacity, with neuropathology and aortic lipid deposition. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:433–443. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.5.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jadavji N.M., Deng L., Leclerc D., Malysheva O., Bedell B.J., Caudill M.A. Severe methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency in mice results in behavioral anomalies with morphological and biochemical changes in hippocampus. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2012;106:149–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghandour H., Chen Z., Selhub J., Rozen R. Nutrient–gene interactions mice deficient in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase exhibit tissue-specific distribution of folates 1. J. Nutr. 2004;134:2975–2978. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.11.2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan A., Tchantchou F., Graves V., Rozen R., Shea T.B. Dietary and genetic compromise in folate availability reduces acetylcholine, cognitive performance and increases aggression: critical role of S-adenosyl methionine. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 2008;12:252–261. doi: 10.1007/BF02982630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winter C., Djodari-Irani A., Sohr R., Morgenstern R., Feldon J., Juckel G. Prenatal immune activation leads to multiple changes in basal neurotransmitter levels in the adult brain: implications for brain disorders of neurodevelopmental origin such as schizophrenia. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12:513–524. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708009206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levav-rabkin T., Blumkin E., Galron D., Golan H.M. Sex-dependent behavioral effects of Mthfr deficiency and neonatal GABA potentiation in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2011;216:505–513. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vries G.J. Sex differences in neurotransmitter systems. J. Neuroendocrinol. 1990;2:1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1990.tb00385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawrance A.K., Racine J., Deng L., Wang X., Lachapelle P., Rozen R. Complete deficiency of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase in mice is associated with impaired retinal function and variable mortality, hematological profiles, and reproductive outcomes. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2011;34:147–157. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9127-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Z., Schwahn B.C., Wu Q., He X., Rozen R. Postnatal cerebellar defects in mice deficient in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2005;23:465–474. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sontag J.-M., Wasek B., Taleski G., Smith J., Arning E., Sontag E. Altered protein phosphatase 2A methylation and Tau phosphorylation in the young and aged brain of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) deficient mice. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:214. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwahn B.C., Laryea M.D., Chen Z., Melnyk S., Pogribny I., Garrow T. Betaine rescue of an animal model with methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency. Biochem. J. 2004;382:831–840. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Broch O.J., Ueland P.M. Regional distribution of homocysteine in the mammalian brain. J. Neurochem. 1984;43:1755–1757. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1984.tb06105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim W., Pae Y. Involvement of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor and free radical in homocysteine-mediated toxicity on rat cerebellar granule cells in culture. Neurosci. Lett. 1996;216:117–120. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)13011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cameron H.A., Mckay R.D.G. Adult Neurogenesis Produces a Large Pool of New Granule Cells in the Dentate Gyrus. 2001;417:406–417. doi: 10.1002/cne.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwahn B.C., Chen Z., Laryea M.D., Wendel U., Lussier-Cacan S., Genest J. Homocysteine–betaine interactions in a murine model of 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency. FASEB J. 2003;17:512–514. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0456fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caudill M.A. Folate and choline interrelationships: metabolic and potential health implications. In: Bailey L.B., editor. Folate Heal. Dis. 2nd edition. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 2009. pp. 449–465. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bottiglieri T., Reynolds E. Folate and neurological disease: basic mechanisms. In: Bailey L.B., editor. 2nd edition. CRC Press; 2009. pp. 355–372. (Folate Heal. Dis.). [Google Scholar]