Abstract

Multidrug therapy is a standard practice when treating infections by nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM), but few treatment options exist. We conducted this study to define the drug-drug interaction between clofazimine and both amikacin and clarithromycin and its contribution to NTM treatment. Mycobacterium abscessus and Mycobacterium avium type strains were used. Time-kill assays for clofazimine alone and combined with amikacin or clarithromycin were performed at concentrations of 0.25× to 2× MIC. Pharmacodynamic interactions were assessed by response surface model of Bliss independence (RSBI) and isobolographic analysis of Loewe additivity (ISLA), calculating the percentage of statistically significant Bliss interactions and interaction indices (I), respectively. Monte Carlo simulations with predicted human lung concentrations were used to calculate target attainment rates for combination and monotherapy regimens. Clofazimine alone was bacteriostatic for both NTM. Clofazimine-amikacin was synergistic against M. abscessus (I = 0.41; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.29 to 0.55) and M. avium (I = 0.027; 95% CI, 0.007 to 0.048). Based on RSBI analysis, synergistic interactions of 28.4 to 29.0% and 23.2 to 56.7% were observed at 1× to 2× MIC and 0.25× to 2× MIC for M. abscessus and M. avium, respectively. Clofazimine-clarithromycin was also synergistic against M. abscessus (I = 0.53; 95% CI, 0.35 to 0.72) and M. avium (I = 0.16; 95% CI, 0.04 to 0.35), RSBI analysis showed 23.5% and 23.3 to 53.3% at 2× MIC and 0.25× to 0.5× MIC for M. abscessus and M. avium, respectively. Clofazimine prevented the regrowth observed with amikacin or clarithromycin alone. Target attainment rates of combination regimens were >60% higher than those of monotherapy regimens for M. abscessus and M. avium. The combination of clofazimine with amikacin or clarithromycin was synergistic in vitro. This suggests a potential role for clofazimine in treatment regimens that warrants further evaluation.

INTRODUCTION

The treatment of diseases caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) is a challenge, partly due to the natural resistance of NTM to most antibiotics. Treatment outcomes are generally poor, and current treatment recommendations have a very limited evidence base, since very few clinical trials have been performed (1, 2).

Multidrug therapy is a standard practice when treating mycobacterial infections. However, the pharmacodynamic (PD) interactions among the combined drugs are largely unknown. Understanding these interactions will help to identify synergistic combinations with increased antibacterial killing, which ultimately can result in a better treatment outcome.

One of the promising combinations is amikacin and clofazimine, given the key role of amikacin in the treatment of NTM infections (2, 3) and the unique characteristics of clofazimine, like its prolonged half-life, its preferential accumulation inside macrophages (4), and the recently found bactericidal activity only after 2 weeks of treatment in the mouse model of tuberculosis (5).

Clarithromycin, on the other hand, has substantial in vitro and clinical activity against Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), and it has been long considered the cornerstone for Mycobacterium abscessus treatment (3).Hence, the examination of its interaction with clofazimine is interesting.

Previous studies showed in vitro synergy between clofazimine and amikacin against both rapidly and slowly growing NTM (1, 6). The combination clarithromycin-clofazimine also showed synergy against MAC strains in checkerboard evaluation (7). These checkerboard titrations offer no information on the mechanism of synergistic activity, the exact killing activity of these combinations, or its concentration dependence. We therefore investigated the pharmacodynamic interactions between clofazimine and amikacin, and clofazimine and clarithromycin, against two key NTM species, using time-kill assays analyzed with two pharmacodynamic drug interaction models: the response surface model of Bliss independence (RSBI) and isobolographic analysis of Loewe additivity (ISLA) (8, 9).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and antibiotics.

Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. abscessus CIP 104536 (Collection of Institute Pasteur) and Mycobacterium avium subsp. hominissuis IWGMT49 (International Working Group on Mycobacterial Taxonomy) type strains were used. Stocks of each strain were preserved at −80°C in Trypticase soy broth with 40% glycerol and were thawed for each assay. Pure powders of amikacin, clarithromycin, and clofazimine obtained from Sigma-Aldrich were dissolved in water, methanol, and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), respectively.

Susceptibility testing.

MICs were determined at the beginning and at the end of the experiments, following CLSI recommendations (10), by broth microdilution in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (CAMHB); commercially available panels were used for amikacin and clarithromycin (RAPMYCO Sensititre, SLOWMYCO Sensititre; Trek Diagnostics/Thermo Fisher), while for clofazimine, manual broth microdilution was performed in Middlebrook 7H9 broth (BD Biosciences). The unexposed M. abscessus type strain was used as a quality control during all MIC determinations.

Mutation analysis.

Mutation analysis of rrs and rrl was performed to detect mutations associated with amikacin and clarithromycin resistance, respectively, in mycobacteria exposed to the two antibiotics in the drug-drug interaction experiments. Briefly, mycobacterial suspensions were heat inactivated at 95°C for 30 min, and then DNA was extracted using MagNAPure LC (Roche Life Science). Relevant fragments of rrs and rrl were amplified using previously described primers and PCR conditions (11, 12). Sequence analyses were performed to detect mutations at codon 1408 in rrs and codons 2058 and 2059 in rrl.

Time-kill assays for single drugs.

The inoculum consisted of mycobacteria in the early logarithmic phase of growth. Individual bottles of 20 ml of Middlebrook 7H9 with oleic acid-bovine albumin-dextrose-catalase growth supplement (BD Biosciences) and 0.05% Tween 80, containing increasing concentrations (from 0.062× to 8× MIC for M. abscessus and 0.062× to 32× MIC for M. avium) of clofazimine, were cultured with the inoculum (∼105 to 106 CFU/ml) at 30°C for M. abscessus and 37°C for M. avium, under shaking conditions at 100 rpm (GFL); ventilation through a bacterial filter (FP 30/0.2 Ca/S; Whatman GmbH) was incorporated. A drug-free and inoculum-free bottle with medium served as the growth and sterility controls, respectively. At defined time points (3, 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h for M. abscessus and 12, 24, 36, 48, 72, 96, 120, 144, 168, and 240 h for M. avium), 10 μl from undiluted samples and samples serially diluted 10-fold in normal saline were plated in triplicate on Middlebrook 7H11 agar plates (BD Biosciences). Plates were incubated for 3 to 5 days at 30°C for M. abscessus, or 7 to 9 days at 37°C for M. avium, and the CFU per milliliter were calculated (lower limit of detection, 33.3 CFU/ml).

Time-kill assays for drug-drug interaction.

Following the same protocol as described above, time-kill assays for M. abscessus and M. avium were performed with four concentrations (from 0.25× to 2× MIC) of each antibiotic alone and in paired combination with clofazimine. MICs for amikacin, clarithromycin, and clofazimine were checked by duplicate at the final sampling time, when colonies were present.

Pharmacodynamic drug interaction analysis.

In order to assess the nature and the magnitude of the in vitro interactions between clofazimine and amikacin or clarithromycin against NTM, the data obtained with time-kill assays were analyzed using the response surface analysis of Bliss independence (RSBI) and the isobolographic analysis of Loewe additivity (ISLA) as described previously (8, 9). The RSBI was used to describe the kinetics of pharmacodynamic interactions at different time points, whereas the ISLA was used to describe the full concentration-effect relationships of the drugs alone and in combination at the end of the experiment.

For that purpose, the percentage of bacterial load at each drug concentration and combination was calculated by dividing the log10 CFU per milliliter with the log10 CFU per milliliter of growth control at each sampling time throughout the experiment. Bliss synergy and antagonism was concluded if the observed bacterial load was statistically significantly (P < 0.05) lower or higher than the expected bacterial load derived from Bliss independence; otherwise, Bliss independence was deemed (8, 9). In order to assess the pharmacodynamic interactions at the entire range of drug concentrations with the ISLA, concentration-effect curves were constructed using the reduction in log10 CFU per milliliter compared to growth control at the end of each experiment and analyzed with sigmoidal maximum-effect (Emax) model after nonlinear regression analysis with global fitting, i.e., shared Emax and minimum effect (Emin) (Graphpad Prism 5.03; Graphpad Inc.). The interaction index (I) was calculated for the stasis effect, i.e., 0-log10 CFU/ml reduction compared to the initial inoculum, as the ratio ECmix/ECadd, where ECmix is the effective concentration of the mixture and ECadd is the effective concentration of a theoretical additive combination, as described previously (8, 9). All analyses were made using multiples of the MIC. Synergy or antagonism was concluded when the I was statistically significantly (P < 0.05) lower or higher than 1; otherwise, additivity was claimed.

Monte Carlo analysis.

In order to bridge the findings to concentrations in humans, Monte Carlo analysis was performed to predict how many patients treated with standard dosing regimens will attain free lung concentrations (Cmax) associated with stasis for strains of both mycobacterial species with MICs usually observed for these species, i.e., 4 to 128 mg/liter for amikacin, 0.125 to 4 mg/liter for clarithromycin, and 0.03 to 4 mg/liter for clofazimine. The mean ± SD target serum Cmax values were 55.3 ± 16.88 mg/liter for amikacin, 2.31 ± 1.89 mg/liter for clarithromycin, and 0.43 ± 0.19 mg/liter for clofazimine (13). In order to determine the free lung concentrations, the epithelial lining fluid (ELF)/serum concentration ratios of 0.5 for amikacin (14) and 8 for clarithromycin (15) were used, whereas for clofazimine, the total lung/serum concentration ratio of 30 (found in mice) was used after taking into account the 85% protein binding (5). Monte Carlo simulation analysis was performed using the normal random number generator function of Excel spreadsheet (MS Office 2007) for 10,000 patients.

RESULTS

Susceptibility.

MICs for clofazimine, clarithromycin, and amikacin were 0.5, 4, and 32 mg/liter for M. abscessus CIP 104536 and 0.06, 4, and 8 mg/liter for M. avium IWGMT49.

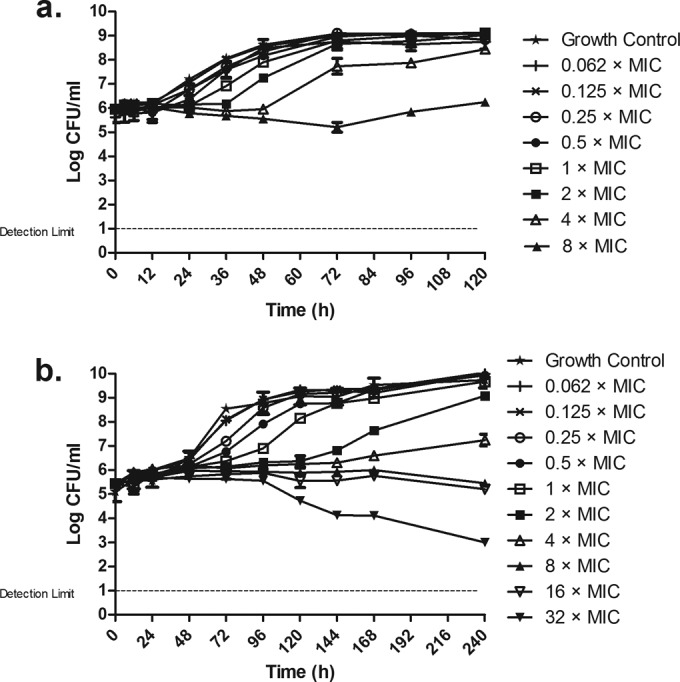

Time-kill assays for single-drug exposure.

Growth and killing curves of M. abscessus and M. avium exposed to different concentrations of clofazimine are shown in Fig. 1. For M. abscessus (Fig. 1a), the effect of clofazimine mainly consisted of inhibition of growth that was concentration dependent. Regrowth appeared after the initial inhibition. Because of solubility issues of clofazimine, concentrations higher than 8× MIC could not be evaluated for M. abscessus.

FIG 1.

Time-kill curves of M. abscessus CIP 104536 (a) and M. avium IWGMT49 (b) exposed to different concentrations of clofazimine. Antibiotic concentrations are indicated by different symbols. Errors bars represent SDs from the replicates.

For M. avium (Fig. 1b), the clofazimine effect was in general stronger than that observed for M. abscessus. Again, the effect was a concentration-dependent inhibition of growth. The highest concentration, 32× MIC, did show some killing effect, particularly from 96 to 240 h.

Single exposures of amikacin and clarithromycin were previously described for both M. abscessus (16) and M. avium (17).

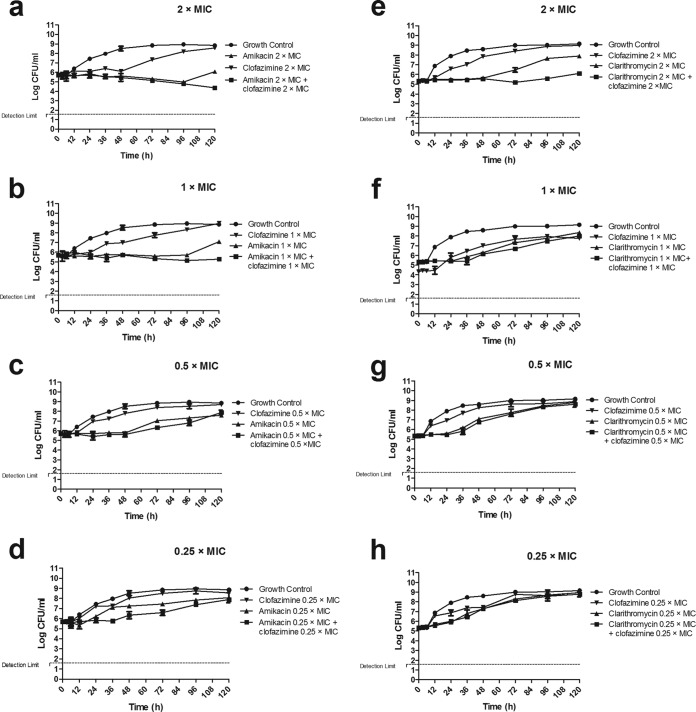

Time-kill assays for combinations. (i) M. abscessus.

The time-kill curves of the drug combinations clofazimine-amikacin and clofazimine-clarithromycin at the different concentrations are shown in Fig. 2 and 3. The effect of clofazimine was consistent with that in the single-drug assay at all concentrations (Fig. 1). Amikacin inhibited growth at concentrations 0.25× and 0.5× MIC and showed discrete killing at 1× and 2× MIC, although regrowth appeared after 96 h at both concentrations. The combination of clofazimine-amikacin showed an inhibitory effect at 0.25× and 0.5× MIC and discrete killing at 1× and 2× MIC but did not reveal the regrowth observed with amikacin alone (Fig. 2a to d). The MICs of the two antibiotics for the colonies exposed to clofazimine, amikacin, and the combination, for 120 h, were identical to those measured prior to the experiment. No mutations in rrs were detected in M. abscessus colonies exposed to amikacin alone or clofazimine-amikacin at the end of the experiment.

FIG 2.

Time-kill curves of M. abscessus CIP 104536 exposed to clofazimine and amikacin (a to d) and clofazimine and clarithromycin (e to h), alone and combined at 2× MIC, 1× MIC, 0.5× MIC, and 0.25× MIC of each drug. No killing was observed in most combinations, except in the paired combination consisting of 2× MIC amikacin and clofazimine. Errors bars represent SDs from the replicates.

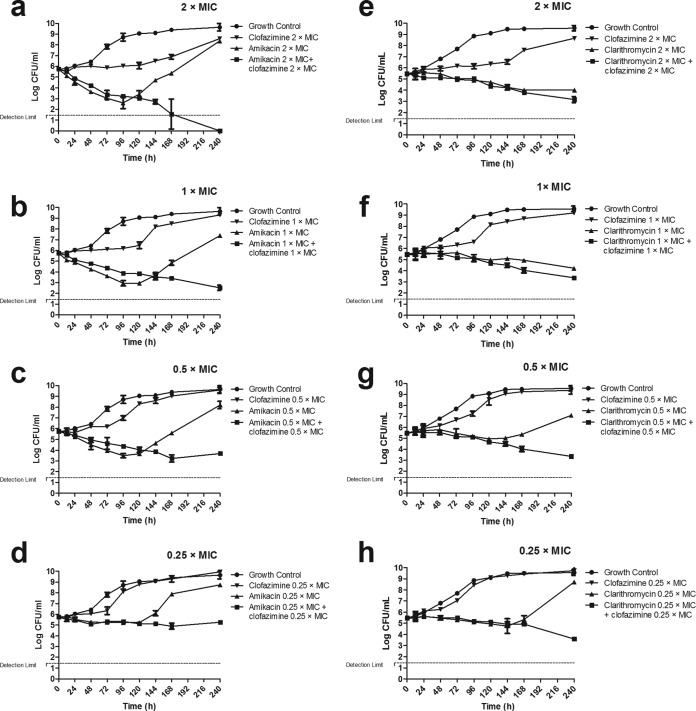

FIG 3.

Time-kill curves of M. avium IWGMT49 exposed to clofazimine and amikacin (a to d) and clofazimine and clarithromycin (e to h), alone and combined at 2× MIC, 1× MIC, 0.5× MIC, and 0.25× MIC of each drug. Modest killing was observed with most combinations, except with the paired combination consisting of 2× MIC of amikacin and clofazimine. Errors bars represent SDs from the replicates.

Clarithromycin inhibited growth, particularly at 2× MIC (Fig. 2e), but regrowth readily appeared after 48 h. For the combination of clofazimine-clarithromycin, the greatest effect was observed at the paired concentrations of 2× MIC, which prevented the regrowth observed with clarithromycin alone. Again, the MICs of both antibiotics for the colonies exposed to clofazimine-clarithromycin and the combination, for 120 h, were identical to those measured prior to the experiment; no mutations in rrl were detected in M. abscessus exposed to clarithromycin or the clofazimine-clarithromycin combination.

(ii) M. avium.

When M. avium IWGMT49 was exposed to clofazimine and amikacin, alone and in combination, in the same experiment (Fig. 3a to d) the killing effect was greater than that observed for M. abscessus. Clofazimine only inhibited the growth; amikacin effect was stronger and faster, especially at 0.5×, 1×, and 2×MIC, but regrowth appeared after 96 to 120 h. The combination of clofazimine-amikacin, at all concentrations, prevented regrowth, and its effect was maximal at the end of the experiment. The MIC for the mycobacteria exposed to clofazimine after 240 h remained the same, whereas amikacin-exposed bacteria showed MICs higher than the initial MICs (>64 mg/liter, versus 8 mg/liter). This increase in MIC was not observed for bacteria exposed to the combination clofazimine-amikacin, in which the amikacin MIC did not change. Colonies exposed to amikacin alone, at any concentration, showed the A1408G mutation in the rrs product, but this mutation was not found in colonies exposed to any of the clofazimine-amikacin combinations.

For the set of experiments with the combination of clofazimine-clarithromycin (Fig. 3e to h), clarithromycin killing effect was observed for all concentrations; however, after 144 h, regrowth was observed, especially at 0.25× and 0.5× MIC. The combination of clofazimine-clarithromycin showed sustained killing at all concentrations, and no regrowth was observed until 240 h.

The MIC of clofazimine for the mycobacteria exposed to this antibiotic for 240 h remain identical to those measured prior to the experiment, but the clarithromycin MIC was higher (>64 mg/liter, versus 4 mg/liter) in bacteria exposed to clarithromycin alone. Again, this increase was not observed in colonies exposed to the combination of clofazimine-clarithromycin. The A2058G mutation in the rrl product was found only in colonies exposed to 0.25× and 0.5× MIC clarithromycin alone, not in colonies exposed to any of the clofazimine-clarithromycin combinations.

Interaction analysis.

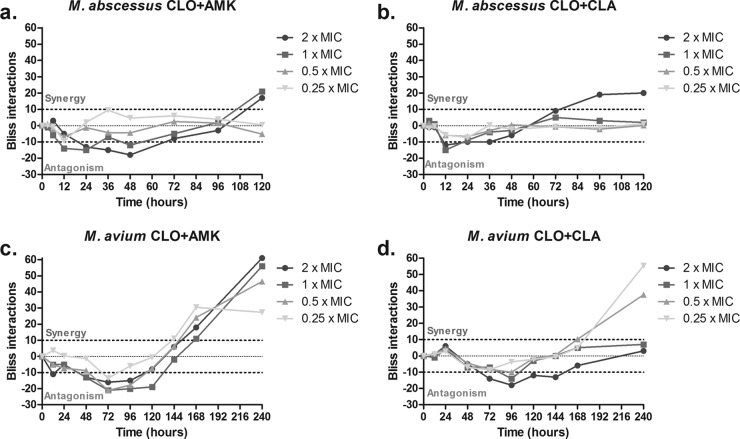

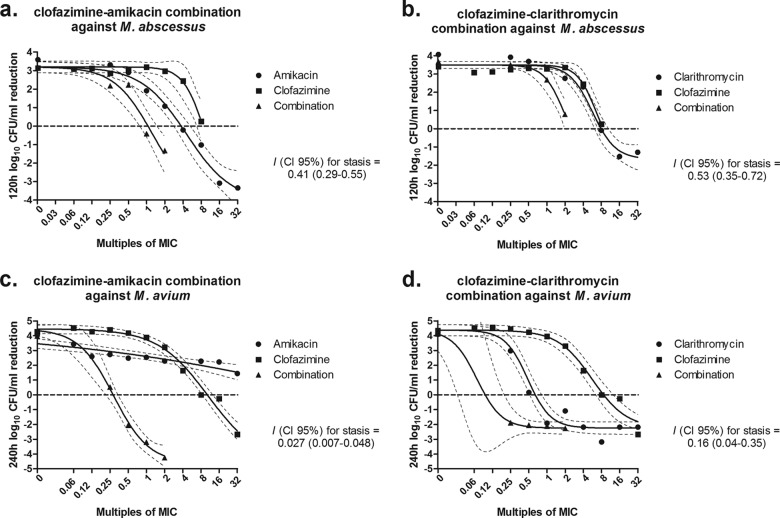

The RSBI analysis of the combination of clofazimine-amikacin against M. abscessus showed independent interactions within the first 12 h which converted to antagonistic interactions at 24 to 48 h and ultimately to synergistic interaction of 29.0% and 28.4% at the end of the experiment for 2× and 1× MIC, respectively (Fig. 4a). Isobolographic analysis of the full concentration-effect relationship of the same combination showed synergy at the end of the experiment at concentrations of ≥1× MIC with an I of 0.41 and a 95% CI of 0.29 to 0.55 (Fig. 5a); stasis was achieved at 4× and 8× MIC of amikacin and clofazimine alone; for the combination, stasis was found at 1× MIC of both drugs.

FIG 4.

Time course of Bliss interactions of clofazimine and amikacin (CLO+AMK) and clofazimine and clarithromycin (CLO+CLA) combinations at 2×, 1×, 0.5×, and 0.25× the respective MICs against M. abscessus (a and b) and M. avium (c and d). Dotted lines represent the significance level for synergistic (+10%) and antagonistic (−10%) interactions. Note the antagonistic interaction at earlier time points followed by the synergistic interaction at later time points.

FIG 5.

Concentration-effect curves of clofazimine and amikacin (left graphs) and clofazimine and clarithromycin (right graphs) combinations against M. abscessus CIP 104536 after 120 h (a and b) and M. avium IWGMT49 after 240 h (c and d). I, interaction index.

The RSBI analysis of the combination clofazimine-clarithromycin against M. abscessus also showed independence in the first 12 h which converted to antagonistic interactions at high concentrations, but ultimately synergistic interactions of 23.5% were observed only at 2× MIC (Fig. 4b). Similarly, ISLA of the same combination showed synergistic interaction reaching stasis at 2× MIC when the drugs were combined. For each drug alone, the endpoint was reached at 8× MIC (I = 0.53; 95% CI, 0.35 to 0.72 (Fig. 5b).

For the combination clofazimine-amikacin against M. avium, the RSBI analysis showed independence up to 48 h, then antagonism up to 120 h, and synergy at the end of the experiment, of 23.2 to 56.7% at all concentrations (Fig. 4c). Strong synergy was found with the ISLA (I = 0.027; 95% CI, 0.007 to 0.048) since stasis was found at 0.5× MIC of the drugs in combination; the same endpoint was reached at 8× MIC and >32× MIC for clofazimine and amikacin alone (Fig. 5c). The same profile of interactions was found for the combination clofazimine-clarithromycin; with RSBI analysis, independence was observed up to 48 h, then antagonism up to 120 h, and ultimately synergy. However, the synergistic interactions were found at concentrations of 0.25× and 0.5× MIC (53.3% and 23.3%, respectively) (Fig. 4d). This was also confirmed with the ISLA (I = 0.16; 95% CI, 0.04 to 0.35), with stasis observed at combinations with <0.25× MIC of each drug, whereas the same endpoint was reached at 0.5× MIC of clarithromycin and 8× MIC of clofazimine alone (Fig. 5d). Interestingly, at combinations with >1× MIC of each drug, the effect was similar to the effect of clarithromycin alone, indicating no interaction as the RSBI analysis showed at the end of the experiment.

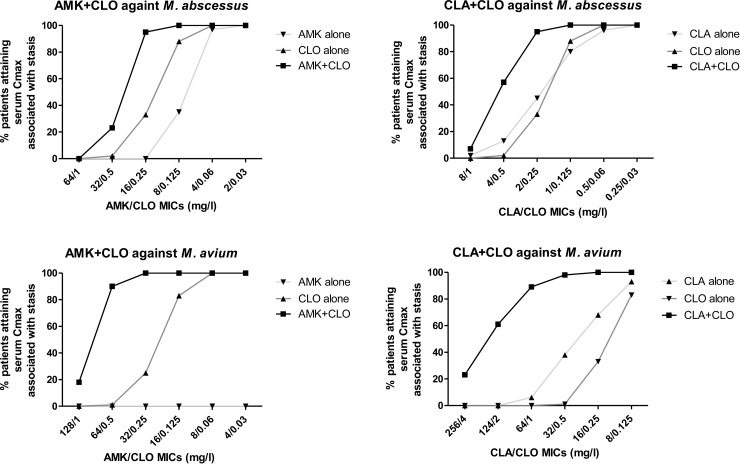

Monte Carlo simulations.

The percentages of patients that will attain lung concentrations associated with stasis of both M. abscessus and M. avium are shown in Fig. 6. For M. abscessus, target attainment rates with clofazimine-amikacin and clofazimine-clarithromycin combinations were higher than with monotherapy regimens, particularly for isolates with amikacin/clofazimine MICs of 16/0.25 mg/liter and clarithromycin/clofazimine MICs of 2/0.25 mg/liter, respectively (>60% difference between combination and monotherapy regimens). For M. avium, a >60% difference was found for the clofazimine-amikacin combination for isolates with amikacin/clofazimine MICs 32 to 128/0.25 to 1 mg/liter and for the clofazimine-clarithromycin combination for isolates with clarithromycin/clofazimine MICs of 32 to 124/0.5 to 2 mg/liter. High (>95%) and low (<5%) target attainment rates were found for all monotherapy and combination regimens for M. abscessus isolates with amikacin/clofazimine/clarithromycin MICs of ≤4/0.06/0.5 mg/liter and ≥64/1/8 mg/liter and for M. avium isolates with amikacin/clofazimine/clarithromycin MICs of ≤8/0.06/8 mg/liter and ≥128/1/256 mg/liter, respectively (except amikacin monotherapy against M. avium, for which target was not attained even for isolates with very low MICs).

FIG 6.

Percentages of patients achieving serum concentrations associated with stasis for M. abscessus and M. avium isolates with increasing MICs for mean daily doses of 15.05 ± 3.62 mg/kg of amikacin (AMK), 14.33 ± 5.09 mg/kg of clarithromycin (CLA), and 1.62 ± 0.28 mg of clofazimine (CLO) alone and in combination corresponding to Cmaxvalues of 55.30 ± 16.88 mg/liter, 2.31 ± 1.89 mg/liter, and 0.43 ± 0.19 mg/liter, respectively (13).

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the activity of clofazimine and the drug-drug interaction in the combinations clofazimine-amikacin and clofazimine-clarithromycin against M. abscessus and M. avium. Although the effect of clofazimine alone was poor, we found synergy, at specific concentrations, for both combinations against both species. The combined therapy prevented the regrowth observed when amikacin or clarithromycin was used alone.

Clofazimine is the prototype riminophenazine antibiotic with in vitro activity against most mycobacteria (1, 4). Its main clinical use so far is in the multidrug treatment of leprosy and multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (18). For the treatment of MAC pulmonary disease, a clofazimine-ethambutol-macrolide regimen was suggested to be as effective as a rifampin-ethambutol-macrolide regimen (2, 19). Our in vitro results support the role of clofazimine for the treatment of M. avium disease, as we found synergistic effects between clofazimine and amikacin or clarithromycin. Its role still needs to be determined but may be to replace rifamycins in patients who do not tolerate those drugs, or as an add-on in the early phase of treatment of severe fibro-cavitary MAC pulmonary disease, when amikacin is also added to the rifampin-ethambutol-macrolide regimen (2, 3). The regrowth observed in experiments with M. avium exposed to amikacin and clarithromycin was associated with an increase in MIC and the appearance of mutations in rrs (A1408G) and rrl (A2058G) (11, 12). Clofazimine prevented this mutational resistance from emerging.

For the treatment of M. abscessus, clofazimine is used, but there is less supportive clinical evidence of its efficacy (20). Amikacin and clarithromycin are cornerstones of treatment, but outcomes remain poor (2, 3). The evaluation of new multidrug regimens is urgently needed, and the inclusion of clofazimine should be considered.

In contrast to M. avium, M. abscessus showed regrowth when exposed to amikacin and clarithromycin alone, but without increases in MICs for these compounds; no mutation was found in the target genes and codons evaluated. This suggests the presence of other mechanisms to decrease susceptibility; adaptive resistance through the expression of efflux pumps has been hypothesized to be linked to reversible low levels of resistance in other mycobacteria (21, 22). Clofazimine may prevent the activation of these mechanisms.

The current 100-mg-once-daily dose of clofazimine (19, 20) has a very limited evidence base. In MAC-infected patients, it yields a peak plasma drug concentration of 0.43 mg/liter (13), close to the MIC we found in this study for M. abscessus CIP 104536 and 8× MIC of M. avium IWGMT49. Clofazimine levels are much higher in tissues than in blood, and the drug accumulates particularly in macrophages, similar to the macrolides (18). Whether the current 100-mg-once-daily dose leads to active concentrations at the site of infection in patients with M. abscessus or M. avium pulmonary disease is not known. A pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) study of clofazimine in the mouse model suggested that lower doses could be effectively used for treatment of tuberculosis (5), but this should be investigated for NTM.

Monte Carlo analysis showed that the number of patients attaining concentrations associated with stasis in vitro was higher in combination than in monotherapy regimens for a wide range of MICs for both mycobacterial species, particularly for M. avium because of the stronger synergy found for this species. The lowest target attainment rates were found for amikacin, which may be explained by the lower amikacin concentrations in tissue than in serum. The currently evaluated inhaled liposomal amikacin could overcome this by delivering larger amounts of the antibiotic directly to the lung (23).

The use of Bliss independence and Loewe additivity analyses (8, 9) allowed us to describe the kinetics of pharmacodynamic interactions and the full concentration-effect relationship. The use of a global response surface model to describe the entire time-concentration-response surface is challenging (24), because of the complexity of pharmacodynamic interactions ranging from antagonistic to synergistic interactions at different time points. We found that after a short period of independent interactions, first antagonism was observed and later synergy. The initial antagonistic interaction, where the effect of combination is similar to the effect of the most active drug without the effect of the least active drug, might be explained by slow intracellular accumulation of the least active drug or a differential effect on mycobacterial subpopulations. Antagonism has been found previously for amikacin combinations against mycobacterial species as well as other antimycobacterial drugs targeting both RNA and DNA synthesis against M. avium (25, 26). The exact mechanisms of these interactions need further investigation.

Our study had some limitations. First, only combinations at fixed-ratio concentrations of 1×:1× MIC were analyzed, prohibiting the investigation of complex concentration-dependent pharmacodynamic interactions. Second, for comparative purposes, all analyses were intentionally performed using multiples of the MICs determined with broth microdilution formats that most labs are using as reference standards. Because MICs may be different in different test systems and media, extrapolation of the present findings should be done using MICs determined as in the present study, i.e., RAPMYCO Sensititre panels in CAMHB for amikacin and clarithromycin and broth microdilution method in Middlebrook 7H9 broth for clofazimine. Third, although time-kill assays allow a more dynamic evaluation than MIC, they do not provide actual dynamic concentrations of the antibiotics, as it occurs during the course of therapy in humans. Nevertheless, we found synergistic combinations that can be further tested in dynamic PK-PD models. Fourth, the emergence of resistance was investigated partially by detecting MIC increases after exposure and resistance-associated mutations in selected colonies. An alternative approach could have been plating of samples on plates containing several magnitudes of the MIC of the drugs under study.

In conclusion, clofazimine is not very active itself but prevents regrowth of M. avium and M. abscessus exposed to amikacin and clarithromycin. This synergistic activity supports a role for clofazimine as part of a combined therapy with amikacin or clarithromycin for M. avium and, to some extent, for M. abscessus. Its role should be further evaluated with dynamic PK-PD models and hopefully later in clinical trials.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

B.E.F. was supported by a Doctoral Fellowship from the Instituto Colombiano para el Desarrollo de la Ciencia y la Tecnología Francisco José de Caldas, COLCIENCIAS, Colombian government (no. 529-2012).

We thank Claudia Congiu for her assistance with the molecular biology work.

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.van Ingen J, Totten SE, Helstrom NK, Heifets LB, Boere MJ, Daley CL. 2012. In vitro synergy between clofazimine and amikacin in treatment of nontuberculous mycobacterial disease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:6324–6327. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01505-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Ingen J, Ferro BE, Hoefsloot W, van Soolingen D. 2013. Drug treatment of pulmonary antituberculous mycobacterial disease in HIV-negative patients: the evidence. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 11:1065–1077. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2013.830413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, Catanzaro A, Daley C, Gordin F, Holland SM, Horsburg R, Huitt G, Lademaco MF, Iseman M, Olivier K, Ruoss S, von Reyn CF, Wallace RJ Jr, Winthrop K, ATS Mycobacterial Diseases Subcommittee . 2007. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175:367–416. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reddy VM, O'Sullivan JF, Gangadharam PR. 1999. Antimycobacterial activities of riminophenazines. J Antimicrob Chemother 43:615–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swanson RV, Adamson J, Moodley C, Ngcobo B, Ammerman NC, Dorasamy A, Moodley S, Mgaga Z, Tapley A, Bester LA, Singh S, Grosset JH, Almeida DV. 2015. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of clofazimine in the mouse model of tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:3042–3305. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00260-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shen GH, Wu BD, Hu ST, Lin CF, Wu KM, Chen JH. 2010. High efficacy of clofazimine and its synergistic effect with amikacin against rapidly growing mycobacteria. Int J Antimicrob Agents 35:400–404. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fattorini L, Piersimoni C, Tortoli E, Xiao Y, Santoro C, Ricci ML, Orefici G. 1995. In vitro and ex vivo activities of antimicrobial agents used in combination with clarithromycin, with or without amikacin, against Mycobacterium avium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 39:680–685. doi: 10.1128/AAC.39.3.680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meletiadis J, Petraitis V, Petraitiene R, Lin P, Stergiopoulou T, Kelaher AM, Sein T, Schaufele RL, Bacher J, Walsh TJ. 2006. Triazole-polyene antagonism in experimental invasive pulmonary aspergillosis: in vitro and in vivo correlation. J Infect Dis 194:1008–1018. doi: 10.1086/506617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meletiadis J, te Dorsthorst DTA, Verweij PE. 2006. The concentration-dependent nature of the in vitro amphotericin B-itraconazole interaction against Aspergillus fumigatus: isobolographic and response surface analysis of complex pharmacodynamic interactions. Int J Antimicrob Agents 28:439–449. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2011. Susceptibility testing of mycobacteria, Nocardia, and other aerobic actinomycetes; approved standard, 2nd ed CLSI document M24-A2. CLSI, Wayne, PA. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nessar R, Reyrat JM, Murray A, Gicquel B. 2011. Genetic analysis of new 16S rRNA mutations conferring aminoglycoside resistance in Mycobacterium abscessus. J Antimicrob Chemother 66:1719–1724. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bastian S, Veziris N, Roux AL, Brossier F, Gaillard JL, Jarlier V, Cambau E. 2011. Assessment of clarithromycin susceptibility in strains belonging to the Mycobacterium abscessus group by erm(41) and rrl sequencing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:775–781. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00861-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Ingen J, Egelund EF, Levin A, Totten SE, Boeree MJ, Mouton JW, Aarnoutse RE, Heifets LB, Peloquin CA, Daley CL. 2012. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of pulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex disease treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 186:559–565. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0682OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tayman C, El-Attug MN, Adams E, van Schepdael A, Debeer A, Allegaert K, Smits A. 2011. Quantification of amikacin in bronchial epithelial lining fluid in neonates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:3990–3993. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00277-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikawa K, Kikuchi E, Kikuchi J, Nishimura M, Derendorf H, Morikawa N. 2014. Pharmacokinetic modelling of serum and bronchial concentrations for clarithromycin and telithromycin, and site-specific pharmacodynamic simulation for their dosages. J Clin Pharm Ther 39:411–417. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferro BE, van Ingen J, Wattenberg M, van Soolingen D, Mouton JW. 2015. Time-kill kinetics of antibiotics active against rapidly growing mycobacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:811–817. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferro BE, van Ingen J, Wattenberg M, van Soolingen D, Mouton JW. 2015. Time-kill kinetics of slowly growing mycobacteria common in pulmonary disease. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:2838–2843. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cholo MC, Steel HC, Fourie PB, Germishuizen WA, Anderson R. 2012. Clofazimine: current status and future prospects. J Antimicrob Chemother 67:290–298. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Field SK, Cowie RL. 2003. Treatment of Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex lung disease with a macrolide, ethambutol and clofazimine. Chest 124:1482–1486. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.4.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jarand J, Levin A, Zhang L, Huitt G, Mitchell JD, Daley CL. 2011. Clinical and microbiologic outcomes in patients receiving treatment for Mycobacterium abscessus pulmonary disease. Clin Infect Dis 52:565–571. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burian J, Ramón-García S, Howes CG, Thompson CJ. 2012. WhiB7, a transcriptional activator that coordinates physiology with intrinsic drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 10:1037–1047. doi: 10.1586/eri.12.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmalstieg AM, Srivastava S, Belkaya S, Deshpande D, Meek C, Leff R, van Oers NS, Gumbo T. 2012. The antibiotic resistance arrow of time: efflux pump induction is a first step in the evolution of mycobacterial drug resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:4806–4815. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05546-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olivier KN, Gupta R, Daley CL, Winthrop KL, Ruoss S, Addrizzo-Harris DJ, Flume P, Dorgan D, Salathe MA, Brown-Elliott BA, Wallace RJ, Griffith DE. 2014. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of liposomal amikacin for inhalation (Arikace®) in patients with recalcitrant nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 189:A4126. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drusano GL, Neely M, van Guilder M, Schumitzky A, Brown D, Fikes S, Peloquin C, Louie A. 2014. Analysis of combination drug therapy to develop regimens with shortened duration of treatment for tuberculosis. PLoS One 9:e101311. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chiodini RJ. 1991. Antimicrobial activity of rifabutin in combination with two and three other antimicrobial agents against strains of Mycobacterium paratuberculosis. J Antimicrob Chemother 27:171–176. doi: 10.1093/jac/27.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kent RJ, Bakhtiar M, Shanson DC. 1992. The in-vitro bactericidal activities of combinations of antimicrobial agents against clinical isolates of Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare. J Antimicrob Chemother 30:643–650. doi: 10.1093/jac/30.5.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]