ABSTRACT

The genesis of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae involves acquisition of CTXϕ, a single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) filamentous phage that encodes cholera toxin (CT). The phage exploits host-encoded tyrosine recombinases (XerC and XerD) for chromosomal integration and lysogenic conversion. The replicative genome of CTXϕ produces ssDNA by rolling-circle replication, which may be used either for virion production or for integration into host chromosome. Fine-tuning of different ssDNA binding protein (Ssb) levels in the host cell is crucial for cellular functioning and important for CTXϕ integration. In this study, we mutated the master regulator gene of SOS induction, lexA, of V. cholerae because of its known role in controlling levels of Ssb proteins in other bacteria. CTXϕ integration decreased in cells with a ΔlexA mutation and increased in cells with an SOS-noninducing mutation, lexA (Ind−). We also observed that overexpression of host-encoded Ssb (VC0397) decreased integration of CTXϕ. We propose that LexA helps CTXϕ integration, possibly by fine-tuning levels of host- and phage-encoded Ssbs.

IMPORTANCE Cholera toxin is the principal virulence factor responsible for the acute diarrheal disease cholera. CT is encoded in the genome of a lysogenic filamentous phage, CTXϕ. Vibrio cholerae has a bipartite genome and harbors single or multiple copies of CTXϕ prophage in one or both chromosomes. Two host-encoded tyrosine recombinases (XerC and XerD) recognize the folded ssDNA genome of CTXϕ and catalyze its integration at the dimer resolution site of either one or both chromosomes. Fine-tuning of ssDNA binding proteins in host cells is crucial for CTXϕ integration. We engineered the V. cholerae genome and created several reporter strains carrying ΔlexA or lexA (Ind−) alleles. Using the reporter strains, the importance of LexA control of Ssb expression in the integration efficiency of CTXϕ was demonstrated.

INTRODUCTION

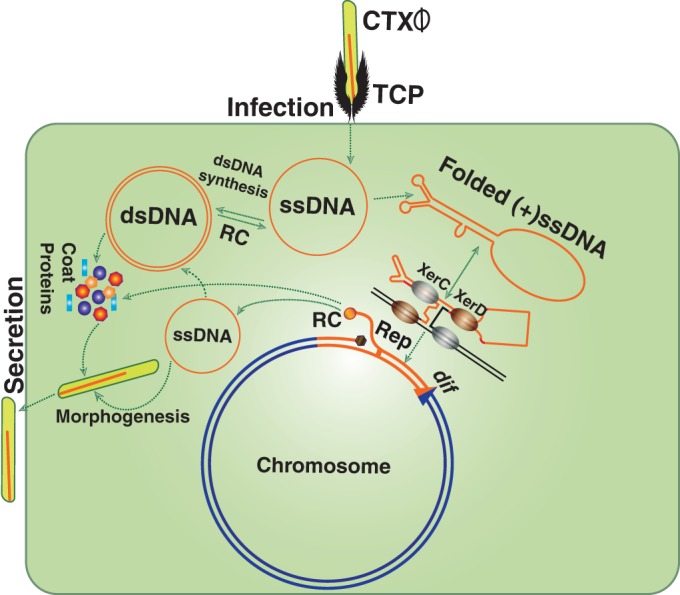

CTXϕ is a lysogenic filamentous phage encoding cholera toxin (CT). The phage introduces its single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) genome into Vibrio cholerae and integrates site specifically at dif1 and/or dif2 using two host-encoded tyrosine recombinases, XerC and XerD (1–4) (Fig. 1). The ∼7.0-kb genome of CTXϕ is organized into two modules, called RS2 and core (5). The functions of RstA and RstB, which constitute part of the RS2 region, are crucial for rolling-circle replication and integration, respectively (5). Core region-encoded proteins are indispensable for phage morphogenesis and CT production (1). In toxigenic isolates of V. cholerae, tandem repeats of the CTXϕ prophage are often found in either one or both chromosomes (6). Several functions encoded by the host and phage genomes, including ssDNA binding proteins (Ssbs) that bind to linear or folded ssDNA, play an important role in CTXϕ integration. The phage and related mobile genetic elements contribute significantly to the plasticity of the V. cholerae genome and provide important functions to the host that are involved in different genetic processes, including DNA replication, recombination, and repair (7, 8). RstB, a phage-encoded ssDNA binding protein, plays an important role in phage lysogeny. The role of RstB in CTXϕ integration is possibly related to maintenance of the folded ssDNA structure of its purine-rich (+)attP. The (+)attP is a forked hairpin structure formed by the ∼150-bp region including attP1 and attP2 in the (+)ssDNA genome of CTXϕ (5, 9). Among others, RecA and Ssb (VC0397) are two important host-encoded ssDNA binding proteins that are crucial for host biology (10, 11). RecA and its homologues are ubiquitous in all forms of life and recognize ssDNA and damaged double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) species to form nucleoprotein filaments and promote recombination between two homologous DNA molecules (12). Purine-rich DNA sequences and folded secondary structures formed due to intrastrand base pairing of ssDNA are two major constraints to RecA polymerization (13). In contrast, Ssb has high affinity for all the species of ssDNA and plays major role in upholding linear ssDNA structure during replication by preventing intrastrand DNA base pairing (14). Interestingly, all three genes encoding RstB, RecA, and Ssb belong to LexA regulon and carry an “SOS box” in their promoter regions. Their expression levels are tightly repressed, moderately repressed, or derepressed by LexA, depending on the level of ssDNA species in the cell (15, 16).

FIG 1.

Diagram showing key steps in the life cycle of CTXϕ. The phage recognizes a V. cholerae cell by sensing the presence of cell surface receptor using the toxin-coregulated pilus (TCP). CTXϕ delivers its ssDNA genome into the host cytoplasm, where it is either converted into a replicative double-stranded phage genome (pCTXϕ) or directly integrated into dif1/dif2 by exploiting two host-encoded tyrosine recombinases, XerC and XerD. Productions of virions from the prophage genome relies on rolling-circle (RC) replication.

LexA directly or indirectly participates in DNA damage repair, stabilizes the replication fork, inhibits cell division, and plays a central role in the bacterial SOS response (17, 18). The LexA protein contains two distinct domains: an N-terminal winged helix-turn-helix DNA binding domain and a C-terminal interactive and latent protease domain (7, 17–19). In Escherichia coli and other gammaproteobacteria, LexA binds to a 16-bp-long DNA sequence consisting of a palindromic motif, 5′-TACTGT(AT)4ACAGTA-3′, of more than 40 genes (20). The derepression of SOS-inducible genes is typically induced by elevated level of ssDNA species in the cytosol. RecA becomes activated once it binds to Mg2+ ions and ATP and polymerizes on ssDNA to form the right-handed helical nucleoprotein helix (21). In E. coli, RecA-DNA-ATP filament induces autocatalytic protease activity of LexA, which introduces a specific cleavage in its Ala84-Gly85 peptide bond. This inactivates the repressor and induces expression of SOS-inducible genes. Not all ssDNA species induce the SOS response.

We conducted genetic and molecular studies to gain insights into the molecular mechanisms that allow the SOS master regulator LexA to manipulate expression of different genes in the presence of the folded ssDNA genome of CTXϕ and influence the integration of CTXϕ in V. cholerae. We constructed several V. cholerae reporter strains to monitor the specificity and efficiency of CTXϕ integration in ΔlexA or lexA (Ind−) cells. In E. coli and other bacteria, RecA-induced autocleavage of LexA takes place in its flexible loop region linking the N-terminal DNA binding domain and the C-terminal dimerization domain. Cleavage removes LexA from the promoter regions of its target genes and derepresses SOS genes. In V. cholerae, LexA cleavage takes place between Ala91 and Gly92 (22). Substitution of either residue disrupts cleavage and creates noncleavable (Ind−) LexA protein. We constructed lexA (Ind−) V. cholerae strains to explore the integration efficiency of CTXϕ in an SOS-noninducing environment. We further dissected the efficiency of CTXϕ integration in the presence or absence of RecA, RstB, and Ssb proteins in different V. cholerae cells. Finally, we determined the pathway by which LexA promotes integration of CTXϕ and possibly other ssDNA phages in V. cholerae and related bacterial cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, phages, and growth conditions.

Relevant characteristics of the genetically modified V. cholerae strains, phages, and plasmids used in this study are listed in Tables 1 and 2. All V. cholerae strains are derivatives of whole-genome-sequenced strain N16961. Recombinant vectors were derived from either ColE1- or R6Koriγ-carrying plasmids. Both V. cholerae and E. coli strains were grown under shaking or static conditions at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium unless otherwise indicated. The antibiotics ampicillin (100 μg/ml), kanamycin (40 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (3 μg/ml), streptomycin (100 to 1,000 μg/ml), and rifampin (Rif) (1 μg/ml) were added when required. Overexpression of Ssb from an arabinose-inducible promoter was induced by the addition of 0.1% arabinose. The CTXϕ::Cm virion was isolated from engineered dif1- and dif2-deficient V. cholerae BS2 cells.

TABLE 1.

Relevant bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype and/or phenotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| V. cholerae strains | ||

| N16961 | wt, O1 El Tor Stpr | 16 |

| BS1 | N16961 ΔTLCϕ-CTXϕ-dif1::lacZ-dif1 Δdif2 Stpr Spcr | 3 |

| BS2 | N16961 ΔTLCϕ-CTXϕ-dif1 Δdif2 Stpr Spcr Rifr | 3 |

| BS11 | BS1 ΔrecA Stpr Spcr | 3 |

| BS13 | N16961(pssb) Ampr | This study |

| BS20 | BS1 ΔlexA::aph1 Stpr Spcr Kanr | This study |

| BD14a | BS1 lexA (Ind−) Stpr Spcr | This study |

| BD15 | BS20::pAP1 Stpr Spcr Zeor | This study |

| BD16 | BD14a::pAP1 Stpr Spcr Zeor | This study |

| AP7 | N16961 ΔrecA Stpr | This study |

| E. coli strains | ||

| FCV14 | DH5α λpir+ ΔxerC::aph | 31 |

| β2163 | F− RP4-2-Tc::Mu ΔdapA::erm-pir | 31 |

TABLE 2.

Relevant plasmids and phages used in this study

| Plasmid or phage | Genotype and phenotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pSW23T | pSW23::oriTRP4 oriVR6K Camr | 32 |

| pBAD24 | pBR322 ori araC bla Ampr | 33 |

| pKAS32 | oriR6K mobRP4 rpsL bla; conjugative vector; Ampr | 34 |

| pDS132 | oriR6K mobRP4 sacB cat; conjugative vector; Camr | 35 |

| pUC4K | ColE1 lacZα la aph; source of the aph1 gene; Ampr Kanr | Laboratory stock |

| pUC18 | oripMB lacZα bla Ampr | Laboratory stock |

| pBD3 | pSW23T::lexA region; Camr | This study |

| pBS51 | pSW23T::ΔlexA::aph1 Camr Kanr | This study |

| pBS52 | pKAS32::ΔlexA::aph1 Ampr Kanr | This study |

| pBS59 | pSW23T::attPVGJ Camr | This study |

| pBS66 | pSW23T::RS2 Camr | 3 |

| pBS126 | pSW23T::attPTLC Camr | 26 |

| pBD6 | pSW23T::lexA (Ind−) Camr | This study |

| pBD32 | pKAS32::lexA (Ind−) Ampr | This study |

| pBD60 | pSW23T::attPCTX | 31 |

| pBD63 | pBD62::lacZ Zeor | 31 |

| pAP1 | pBD63::PrecN-lacZec Zeor | This study |

| pDA1 | pBAD24::ssb Ampr | This study |

| pBD79 | pUC18::upstream-downstream regions of recA; Ampr | This study |

| pDA2 | pDS132::upstream-downstream regions of recA; Camr | This study |

| Phages | ||

| CTXϕ:Cm | CTXϕ::cat::R6K::RP4 Camr | 31 |

| RS1:Cm | RS1::cat::R6K::RP4 Camr | 4 |

| VGJϕ | VGJϕ::kan::R6K::RP4 Kanr | 25 |

| TLCϕ | TLCϕ::cat::R6K::RP4 Camr | 26 |

Construction of isogenic mutants.

Construction of isogenic ΔlexA, lexA (Ind−), and other relevant V. cholerae cells was performed by sequential integration/excision methods using derivatives of suicide vectors carrying rpsL or sacB as a counterselectable marker (Table 2). Recombinant vector pBS52, a derivative of suicide vector pKAS32 carrying the ΔlexA::aph1 allele, was used for the construction of the ΔlexA V. cholerae strain (Table 2). The vector was introduced into V. cholerae by conjugation, and transconjugants were selected in the presence of ampicillin. Excision of the native allele with plasmid backbone was confirmed by PCR and DNA sequencing. Relevant phenotypes of lexA mutants were confirmed based on a previous report (23). Although E. coli ΔlexA is not viable in a wild-type (wt) genetic background, this phenotype is different for V. cholerae strain N16961. Similarly, an SOS-noninducing V. cholerae strain was constructed by using suicide vector pBD32, a derivative of pKAS32 carrying the lexA (Ind−) allele (Table 2). PCR and DNA sequencing confirmed the genotype of lexA (Ind−) V. cholerae. Markerless deletion of recA gene was carried out using suicide vector pDA2, a derivative of pDS132 carrying upstream and downstream regions of recA of V. cholerae strain N16961 (Table 2). Both the genotype and phenotype of N16961ΔrecA derivative strain AP7 were confirmed by PCR using primers P152-P153 (Table 3) and UV sensitivity assays, respectively.

TABLE 3.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Use | Sequence (5′ → 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| P148 | Cloning of lexA region | CGAGCAAGGCATGTTCACAG |

| P149 | Cloning of lexA region | CGATCTCATCCAGAATGTCG |

| P150 | Construction of ΔlexA::aph1 allele | GCGATGCATCGGCTTCATGAGTCACCTGTC |

| P151 | Construction of ΔlexA::aph1 allele | GCGATGCATCGCAACAGCACTTGGATGTG |

| P309 | Construction of lexA (Ind−) allele | GTGAACCGATTCTTGCTCAAG |

| P310 | Construction of lexA (Ind−) allele | CATCGGCAACGCGGCCAATCAAAGGC |

| P359 | Cloning of ssb | CGGGAATTCACCATGGCAAGCCGTGGCGTGAAC |

| P360 | Cloning of ssb | CCGCTGCAGCTAAAACGGGATGTCGTCATC |

| P367 | PrecN-lacZec fusion | CGCGTCGACGCTTGGCTGGTCGAGCAAAC |

| P368 | PrecN-lacZec fusion | CGCCTGCAGCATGTTTGCACCTGTATGAT |

| P152 | Deletion of recA | TGTGACCCACGATCAGGATG |

| P153 | Deletion of recA | CAGTTGCAGAACGTCAGTC |

| P172 | Deletion of recA | CCGTCTAGACGTTAATCAGTTTGCGGGTGAGTGGC |

| P173 | Deletion of recA | GGCGAGCTCCCGACGTTTTCTAGGTCGTTG |

Construction of recombinant vectors.

For the deletion of the lexA gene, recombinant vector pBS52 was constructed in the following way. First, a 2.2-kb lexA region carrying the lexA open reading frame (ORF) and 600-bp upstream and downstream sequences was amplified from the chromosome of N16961 using primer pair P148-P149 (Table 3), and the amplified product was cloned into EcoRI-digested pSW23T to generate the recombinant vector pBD3. pBD3 was PCR amplified using primers P150-P151 (Table 3), and the amplified product was digested with NsiI. The kanamycin resistance gene cassette (aph1) was digested out from pUC4K (Table 2) with PstI and cloned into NsiI-digested pBD3. The resulting vector was named pBD51. The ΔlexA::aph1 allele was digested from pBD51 with EcoRI and cloned into similarly digested suicide vector pKAS32 to create the allele replacement vector pBS52 (Table 2). Similarly, an inverse PCR method was used to introduce the A91D mutation in pBD6 to develop the lexA (Ind−) allele. First, the Ala91-encoding codon (GCG) of the lexA gene was replaced by an Asp-encoding codon (GAU) using primers P309-P310 (Table 3). The lexA (Ind−) allele was confirmed by DNA sequencing. Subsequently, the lexA (Ind−) allele was transferred from pSW23T to suicide vector pKAS32 to develop pBD32 (Table 2). Suicide plasmid pDA2 carrying upstream and downstream regions of recA of V. cholerae was constructed by the following method. First, upstream and downstream regions of recA were amplified from BS11 using primers P178-P179 (Table 3). The amplified product was digested with XbaI-SacI and cloned into similarly digested cloning vector pUC18. The resulting vector was named pBD79 (Table 2). Then, the upstream and downstream regions of recA were transferred into suicide vector pKAS32 by using XbaI-SacI. The newly developed vector was designated pDA2 (Table 2). Reporter plasmid pAP1 carrying the E. coli β-galactosidase-encoding gene lacZec fused with the recNvc promoter was constructed by using our previously reported plasmid pBD63 (Table 2). The recNvc promoter was amplified from the N16961 genome using primers P367-P368 (Table 3) and fused with the lacZec ORF using PstI-SalI. The fusion was confirmed by DNA sequencing, and the plasmid was named pAP1. The chloramphenicol resistance gene cassette, cat, along with R6Koriγ and RP4 was inserted in the CTXϕ genome between the ctxB gene and attP1 site by sequential cloning. The CTXϕ genome was obtained from the N16961 chromosome by PCR, and fusion was done with the help of EcoRI-SalI. PCR and DNA sequencing confirmed recombinant CTXϕ::Cm.

Transformation, conjugation, and electroporation.

Rubidium chloride-treated E. coli cells were used for transformations. Conjugation was done between diaminopimelic acid (DAP) auxotroph E. coli β2163 donors and wt or mutant V. cholerae cells on 0.44-μm sterile filter paper. The conjugation plate was supplemented with 0.3 mM DAP. Exponentially growing (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of ∼0.3) donor and recipient cells were mixed in a 1/2 ratio and incubated at 37°C overnight. Conjugants were selected based on antibiotic resistance traits of conjugative plasmids and DAP auxotrophy of donor cells. At least 500 ng plasmid DNA was used for electroporation. Both the competent cells and plasmids were resuspended in G buffer (137 mM sucrose, 1 mM HEPES, pH 8.0). Electrocompetent cells (40 μl) were mixed with plasmid DNA in a prechilled microcentrifuge tube (MCT) and transferred to a 0.1-cm electroporation cuvette, and electroporation was done at 1,400 V for a ∼5-ms pulse.

In vivo integration assays.

E. coli β2163 donors and V. cholerae recipients were grown to early log phase (OD600 of 0.3) and mixed in a 1/2 ratio in LB supplemented with 0.3 mM, DAP and the mixtures were spotted on the top of a sterile 0.44-μm filters paper placed on a nutrient-rich Luria agar (LA) plate and incubated for 3 h. Conjugants were selected based on the resistance trait of plasmid and DAP auxotrophy. The specificity of CTXϕ::Cm and its truncated derivatives pBS66 and pBD60 was checked by using X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) on the selection plate. Efficiency of integration of CTXϕ::Cm, RS2::Cm (pBS66), and RS1::Cm (pMEV30) was measured at 37°C after 8 h of growth in LB supplemented with appropriate doses of antibiotics. In the case of Ssb-inducible strains, Ssb production was induced for 3 h in liquid culture with 0.1% arabinose before plating.

β-Galactosidase activity assays.

β-Galactosidase activity in the cell lysates of V. cholerae reporter strains was measured using a β-galactosidase enzyme activity detection kit (Sigma, USA). Briefly, different reporter strains were grown in LB medium at 37°C under shaking conditions until the culture OD600 reached ∼0.6. Next, 0.5 ml of culture was centrifuged to collect the cell pellet. The cells were washed in Z buffer (60 mM Na2HPO4, 40 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, pH 7.4) and lysed with kit-provided lysis buffer. o-Nitrophenyl β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG) was added to the cell lysate and incubated at 37°C until yellow color became apparent. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 1 M sodium bicarbonate solution. β-Galactosidase enzyme activity was measured according to the instructions of the β-galactosidase enzyme activity assay kit manufacturer (Sigma, USA).

Detection of Rif-resistant cells.

V. cholerae strains were grown overnight in LB supplemented with a sub-MIC (0.01 μg/ml) of rifampin (Rif). The cultures were washed in M9 minimal medium. Appropriate dilutions of resuspended cells were plated on LA plates supplemented with the MIC of Rif as reported previously (23).

UV sensitivity assay.

The UV sensitivity assay for all the reporter strains was performed as described previously (15). Briefly, V. cholerae cells were grown to early log phase (OD600 of ∼0.4), and serial dilutions of cultures were plated on LA medium. Plates were exposed to UV at 0 to 40 J/m2 for 15 s in the absence of light and incubated in the dark at 37°C for 16 h. The numbers of colonies on irradiated and nonirradiated plates were counted, and ratios were calculated.

RESULTS

Construction and characterization of isogenic ΔlexA and lexA (Ind−) V. cholerae reporter strains to monitor CTXϕ integration.

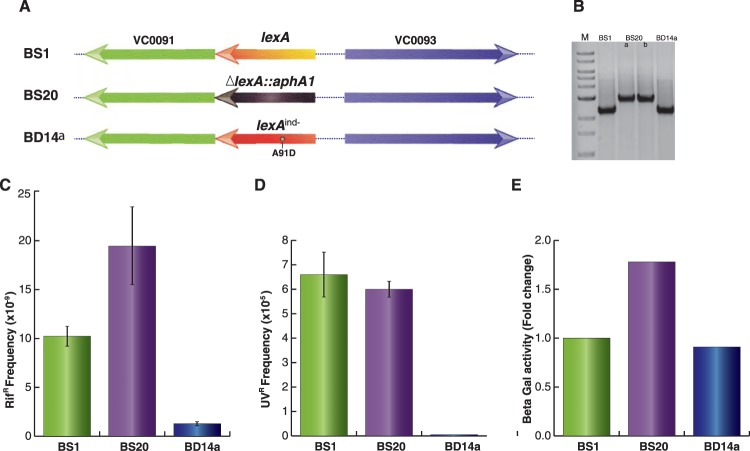

Since CTXϕ can replicate and integrate in the chromosome of V. cholerae, we sought to develop an assay to distinguish cells carrying either integrative or replicative phage DNA. To this end, we selected genetically engineered cells of V. cholerae (BS1) carrying a functional lacZ::dif1 allele at the replication terminus region of large chromosome (3). We then deleted the chromosomal lexA gene from BS1 by the allele replacement method (Fig. 2A). Similarly, we created an SOS-noninducing lexA allele [lexA (Ind−)] by replacing alanine with aspartic acid (A91D) at the Ala91-Gly92 peptide bond position in V. cholerae LexA. Relevant genotypes of ΔlexA and lexA (Ind−) cells were confirmed by PCR and DNA sequencing (Fig. 2B). Phenotypes of both types of cells were confirmed by measuring development of antibiotic resistance in the presence of a sub-MIC of Rif (Fig. 2C). The sub-MIC of Rif (0.01 μg/ml) was chosen as the concentration 100-fold lower than the MIC (1 μg/ml) for V. cholerae. The sub-MIC of Rif induces the bacterial SOS response and stimulates mutagenesis through the activation of error-prone DNA polymerase (DinB/VC2287), as reported previously (23). We observed that ΔlexA V. cholerae cells developed about 15-fold-higher levels of Rifr CFU than lexA (Ind−) cells (Fig. 2C). We also measured the survival ability of wt, ΔlexA, and lexA (Ind−) V. cholerae strains upon brief exposure to UV. Our data showed that SOS-negative BD14a [lexA (Ind−)] is highly sensitive to exposure to UV (Fig. 2D). We further tested phenotypes of ΔlexA and lexA (Ind−) cells using reporter plasmid pAP1 (Table 2) carrying the lacZ gene under the control of the V. cholerae recN promoter. We observed an ∼2-fold reduction of β-galactosidase activity in lexA (Ind−) cells compared to ΔlexA cells (Fig. 2E).

FIG 2.

Construction and characterization of ΔlexA and lexA (Ind−) V. cholerae strains. (A) Schematic representation of the lexA locus of V. cholerae reporter strains engineered in this study. In BS20, kanamycin resistance-encoding aphA1 replaced the lexA gene. The lexA (Ind−) allele was created by site-directed mutagenesis and used to replace the native lexA gene by the sequential allele exchange method. (B) The lexA loci of all three reporter strains were amplified by PCR and resolved in a 1% agarose gel. In the first lane, a 1-kb ladder was used to confirm the desired size of the amplicon. (C) Spontaneous mutation frequency after treatment with a sublethal concentration of rifampin. All three strains were grown overnight in LB supplemented with 0.01 μg/ml rifampin and plated on appropriate selection plates. The mutation frequency, corresponding to the rifampin-resistant CFU, was calculated based on the total number of CFU. (D) UV sensitivity assay of different V. cholerae strains engineered in this study. Serial dilutions of exponential cultures were subjected to a short exposure to UV. Frequency was determined based on the numbers of colonies on irradiated plates relative to those on nonirradiated plates. (E) Determination of the recN promoter activity after fusion to the lacZ reporter gene. The PrecN-lacZ fusion was chromosomally integrated into the reporter strain at the dif1 locus using vector pAP1. Exponential-phase cultures (500 μl) of V. cholerae were used to measure the β-galactosidase activity.

LexA deficiency affects CTXϕ integration.

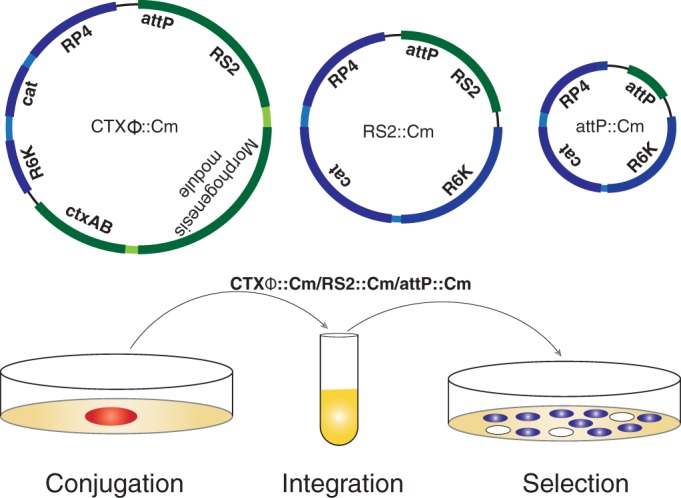

We next investigated the specificity and efficiency of CTXϕ integration in lacZ-dif1 reporter strains carrying different lexA alleles. First, a dif1-specific CTXϕ carrying the conditionally replicating vector pSW23T (Table 2) between ctxB and the attP region was engineered and isolated from dif-deficient V. cholerae cells (Fig. 1). The isolated CTXϕ::Cm genome was used to infect all three reporter strains. The genome of CTXϕ was introduced into V. cholerae cells by either conjugation or electroporation. The specificity and efficiency of integration were monitored by screening blue/white colonies (Fig. 3). All three reporter strains carrying the lacZ-dif1 allele express functional β-galactosidase and turn blue in the presence of X-Gal in the selection plate. Any integration event in the dif1 site of the lacZ-dif1 allele in the chromosome of V. cholerae disrupts β-galactosidase production, and thus the white colonies on selection plates represent the V. cholerae population carrying the CTXϕ lysogen. We observed that compared to that in wt cells, there was a 2-fold reduction of CTXϕ integration in lexA-negative strains (Table 4). The reduced level of integration of CTXϕ was not linked with morphogenesis proteins and virion production, because a similar level of reduction was observed when only the replication and integration module of CTXϕ (RS2) was delivered in the same reporter strain (Fig. 3; Table 4). We tested the statistical significance of reduced level of integration of RS2 in ΔlexA V. cholerae cells using an unpaired t test with Welch's correction. We observed that the difference in integration efficiency is statistically significant between BS1 and BS20 (P = 0.0035) and BD14 and BS20 (P = 0.0011) but that the difference between BS1 and BD14 is not significant (P = 0.067).

FIG 3.

Schematic depiction of phage genomes and in vivo integration assay. CTXϕ and its derivatives carrying the replicative (RS2) or only the integrative (attP) module were fused with a conditionally replicative vector pSW23T carrying the origin of transfer (RP4) and chloramphenicol resistance traits (Cam). Genomic DNA of CTXϕ::Cm or its derivatives was isolated from dif-deficient BS2 V. cholerae cells and were introduced into λpir-carrying β2163 E. coli cells. CTXϕ::Cm was introduced into lacZ-dif1 reporter strains by conjugation or electroporation. Integrations were monitored at 37°C by screening blue/white colonies on selection plates supplemented with X-Gal and antibiotics at appropriate doses.

TABLE 4.

Integration frequencies of CTXϕ and its RS2 elements in wt, ΔlexA, and lexA (Ind−) V. cholerae reporter strainsa

| IMEXb | Host | % integration (mean ± SD)c | No. of screened colonies |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTXϕ | BS1 | 5.46 ± 0.44 | 393 |

| RS2 | BS1 | 11.6 ± 1.36 | 697 |

| CTXϕ | BS20 (ΔlexA) | 2.48 ± 1.5 | 850 |

| RS2 | BS20 (ΔlexA) | 3.86 ± 1.5 | 381 |

| CTXϕ | BD14a [lexA (Ind−)] | 6.34 ± 1.4 | 609 |

| RS2 | BD14a [lexA (Ind−)] | 13.97 ± 1.39 | 345 |

V. cholerae cells carrying replicative or integrative forms of CTXϕ or RS2 form blue and white colonies on the selection plate. The selection plate contained the chromogenic substance X-Gal and Str and Cam antibiotics.

IMEX, integrative mobile element exploiting Xer recombination.

The integration frequency was estimated by counting blue and white colonies. The standard deviation was calculated from at least three independent experiments.

We further extended our analyses to find out whether the reduced level of integration was linked with the replication function of CTXϕ. We removed the replication module of CTXϕ and introduced only the integration module, attP, in V. cholerae cells carrying different lexA alleles (Fig. 3). We observed that the efficiency of integration of (+)attP CTXϕ was also compromised in ΔlexA V. cholerae cells (Table. 5). The sequential subtractions of different functional modules of CTXϕ genome clearly indicated that repression by LexA is linked to the integration reaction and important for acquisition of CTXϕ in the genome of the cholera pathogen.

TABLE 5.

Integration frequencies of attPCTX, attPVGJ, and attPTLC elements in lacZ-dif1 reporter strains carrying different lexA alleles

| IMEXa | Host | Integration frequency, 10−7 (mean ± SD)b | No. of screened colonies |

|---|---|---|---|

| attPCTX | BS1 | 387 ± 273 | 1,160 |

| attPCTX | BS20 (ΔlexA) | 103 ± 65 | 310 |

| attPCTX | BD14a [lexA (Ind−)] | 960 ± 394 | 2,880 |

| attPVGJ | BS1 | 1,687 ± 716 | 5,060 |

| attPVGJ | BS20 (ΔlexA) | 2,110 ± 285 | 6,330 |

| attPVGJ | BD14a [lexA (Ind−)] | 250 ± 215 | 1,050 |

| attPTLC | BS1 | 340 ± 255 | 1,020 |

| attPTLC | BS20 (ΔlexA) | 1,543 ± 298 | 4,630 |

| attPTLC | BD14a [lexA (Ind−)] | 213 ± 81 | 640 |

IMEX, integrative mobile element exploiting Xer recombination.

Since all the plasmids carrying phage attachment sites were conditionally replicative, the integration frequency was estimated by counting numbers of white colonies on the selection plates and the total number of conjugants was obtained using a replicative plasmid carrying a similar genetic backbone without attP. The standard deviation was calculated from at least three independent experiments.

Increased (+)attPCTX integration in the V. cholerae lexA (Ind−) mutant.

LexA inactivation allows expression of several DNA binding proteins in SOS-positive cells. Some of these proteins have strong affinity to ssDNA and could influence CTXϕ integration by altering the folded structure of (+)attP of CTXϕ. To address this possibility, we monitored the integration efficiencies of CTXϕ, RS2, and (+)attPCTX in SOS-noninducing V. cholerae reporter strains. In SOS-noninducing cells, LexA cleavage was impeded by introducing an A91D change in the protein because Ala91 contributes to the formation of the Ala91-Gly92 scissile peptide bond. Surprisingly, the integration efficiency of attP(+) of CTXϕ was greatly increased in lexA (Ind−) V. cholerae cells (Table 5). This is in marked contrast to the integration efficiency of (+)attP of CTXϕ in wt and ΔlexA V. cholerae cells (Table 5). Although the integration efficiency of CTXϕ and the RS2 element is slightly increased in SOS noninducing cells, the differences of their integration efficiency between SOS-inducing and -noninducing cells are not distinct like for (+)attP of CTXϕ (Table 4).

Stimulation in the lexA (Ind−) mutant is linked to ssDNA integration of CTXϕ.

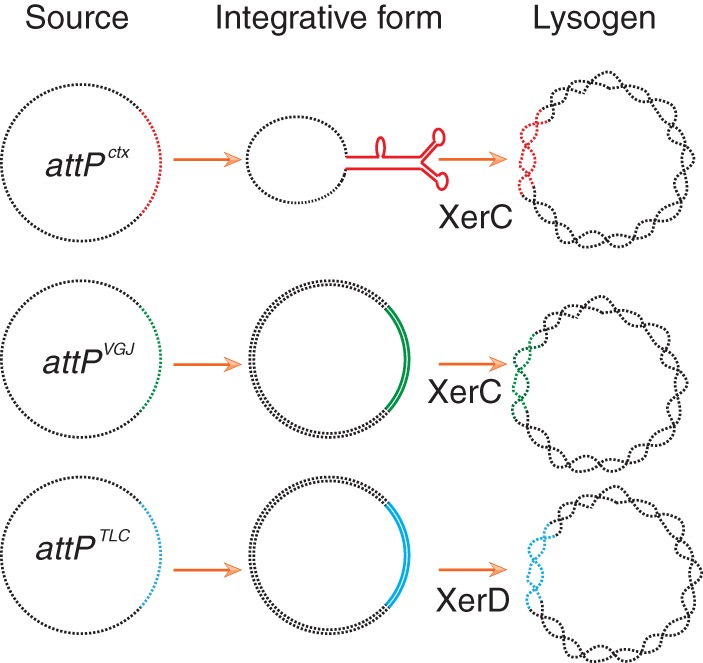

A crucial step in CTXϕ integration is that the ssDNA genome needs to fold into a stem-loop structure to mimic the double-stranded DNA binding site of XerC and XerD (Fig. 1) (24). The increase and decrease of integration efficiency of CTXϕ in lexA (Ind−) and ΔlexA cells, respectively, may be linked to the ssDNA substrate or to the recombinase activity. To assess such possibilities, we introduced the integration modules of two related ssDNA filamentous phages, VGJϕ and TLCϕ (Fig. 4). Like CTXϕ, both the phages use the same host-encoded XerC and XerD recombinases, but their integration in the chromosome of the cholera pathogen relies on the double-stranded attP substrates (25, 26). We observed that integration of VGJϕ and TLCϕ is not increased in lexA (Ind−) V. cholerae cells (Table 5). In contrast, the integration efficiency of VGJϕ or TLCϕ was increased in ΔlexA V. cholerae cells (Table 5). Since integration of VGJϕ or TLCϕ relies on its replicative dsDNA genome, these results indicate that LexA possibly helps only the ssDNA substrate for integration.

FIG 4.

Scheme depicting the integrative forms of the attachment sites of three different vibriophages. Black lines represent vector backbone and chromosomal DNA. Enzymes catalyzing the first step of integration are specified.

Integration of satellite phage RS1 also increases in lexA (Ind−) V. cholerae cells.

Like CTXϕ, the satellite filamentous phage RS1 also exploits the same host recombination machinery for lysogenic conversion. Although the attachment sites of the two phages are quite similar, their replication and morphogenesis modules are not. In contrast to the case for CTXϕ, the replication-integration module of RS1 encodes an additional function, RstC, which interacts with phage-encoded repressor RstR and plays important role in its life cycle. We monitored the specificity and efficiency of RSI integration in the presence or absence of the lexA or lexA (Ind−) allele. We introduced the RS1::Cm genome into V. cholerae by conjugation, and integration was monitored after 8 h of incubation. Like that of CTXϕ, RSI integration was also reduced in ΔlexA cells (Table 6). In contrast, RS1 integration was slightly increased in lexA (Ind−) cells (Table 6).

TABLE 6.

Integration frequencies of the RS1::Cm element in wt, ΔlexA, and lexA (Ind−) V. cholerae reporter strains

| Host | % integration (mean ± SD)a | No. of screened colonies |

|---|---|---|

| BS1 | 5.86 ± 1.57 | 577 |

| BS20 (ΔlexA) | 1.14 ± 0.2 | 760 |

| BD14a [lexA (Ind−)] | 7.32 ± 2.36 | 678 |

The integration frequency was determined as described for Table 4. The standard deviation was calculated from at least three independent experiments.

The increase in integration of (+) attPCTX in V. cholerae lexA (Ind−) is RstB and Ssb dependent.

To gain insight into mechanisms by which LexA contributes to CTXϕ integration, we focused on the three abundant ssDNA binding proteins, RecA, RstB, and Ssb, in toxigenic cholera strains. LexA tightly or moderately represses the expression of all three ssDNA binding proteins during normal physiological conditions (7, 27).

First, we compared CTXϕ integration in RecA-positive and RecA-deficient V. cholerae cells (Table 7). We did not observe any drastic change of CTXϕ integration in the presence or absence of RecA function (Table 7). This could be due to the fact that RecA binds poorly to folded DNA structure and purine-rich DNA sequences, which are dominant features of the functional (+)attPCTX structure. We then used wt and ΔrstB V. cholerae cells to monitor the integration of (+)attPCTX in the presence and absence of RstB. We observed a 10-fold reduction in (+)attPCTX integration in the absence of RstB (Table 7).

TABLE 7.

Integration frequencies of attPCTX in presence or absence of the three ssDNA binding proteins RecA, Ssb, and RstB

| Host | Integration frequency, 10−7 (mean ± SD)a | No. of screened colonies |

|---|---|---|

| N16961 (wt) | 3,733 ± 470 | 1,120 |

| AP7 (ΔrecA) | 3,660 ± 640 | 1,100 |

| BS1 (ΔrstB recA+) | 387 ± 273 | 1,160 |

| BS11 (ΔrstB ΔrecA) | 253 ± 117 | 760 |

| BS1 (ΔrstB pssb) | <1 | 107 |

| BS13 (rstB+ pssb) | 13 ± 7 | 260 |

The integration frequency was determined as described for Table 5. The standard deviation was calculated from at least three independent experiments.

Ssb is an essential protein; hence, deletion of the gene encoding the protein is not possible. To overcome this issue, we overexpressed Ssb (VC0397) in the reporter strain and monitored (+)attPCTX integration. Overexpression was done from an arabinose-inducible promoter. We observed that in the absence of RstB, Ssb overexpression completely abolished (+)attPCTX integration (Table 7). The presence of RstB partially compensated for the deleterious effect of Ssb in (+)attPCTX integration (Table 7). We conclude that LexA possibly helps CTXϕ integration in V. cholerae strains by maintaining the optimal level of Ssb under normal physiological conditions.

DISCUSSION

In toxigenic V. cholerae, two most important traits, CT production and antibiotic resistance, which are directly linked to the fitness of the pathogen, are acquired as ssDNA of CTXϕ (2, 28). Once inside the cell, ssDNA elements of both traits form folded structure and provide recognition sites for tyrosine recombinases to catalyze the integration reaction (29). Both the ssDNA genome and the folded structure of the CTXϕ genome are essential for its chromosomal integration. Bacterial cells, including V. cholerae, encode several ssDNA binding proteins with different specificities and affinities to their ssDNA substrates (16). Different genes encoding ssDNA binding proteins are derepressed during SOS induction. SOS induction is a well-studied cellular process, and it is crucial for bacterial genome plasticity. In light of recent studies, it is becoming clear that in bacteria the SOS response makes substantial contributions to acquisition and dissemination of virulence factors, emergence of pathogens with multiple drug resistance, and survival of bacteria upon exposure to harsh environmental conditions (7). In CTXϕ lysogens of V. cholerae, RecA, Ssb, and RstB are three most important ssDNA binding proteins and are crucial for genome plasticity and integrity. While RecA is important for the maintenance of genomic integrity and plasticity, Ssb is crucial for genome duplication (30). RstB, a phage-encoded ssDNA binding protein, is crucial for integration of CTXϕ (9). The SOS master regulator LexA represses all three proteins at different levels under normal physiological conditions.

To explore the mechanism, we introduced complete or truncated derivatives of CTXϕ into ΔlexA or lexA (Ind−) V. cholerae cells. We observed that for both versions of CTXϕ, integration efficiency was compromised in the absence of LexA. To rule out the possibility that the reduced level of integration was linked to neither the morphogenesis module nor the replication module, we performed further analysis using only the integrative module of CTXϕ. Higher levels of reduction of (+)attPCTX integration were observed in SOS-induced cells. This inference is further strengthened by the observation that integration increases severalfold in the presence of noncleavable LexA (Table 5).

This increase was limited to only the ssDNA mode of integration. Several other vibriophages, such as VGJϕ, VSKϕ, and TLCϕ, also exploit the same host recombinases to integrate into the dif1 site of V. cholerae chromosome. We extended our analysis to understand whether the recombinases or substrate for the same attP of other vibriophages are influenced in the absence of lexA or in the presence of the lexA (Ind−) allele in the reporter strains. We observed that such LexA effects were limited to only CTXϕ and its ssDNA (+)attPCTX sequence. Since (+)attPCTX has no SOS box, we suggest that the decrease or increase of repression or induction associated with the lexA-negative or lexA (Ind−) cells, respectively, is possibly linked to the differential expression of some of the ssDNA binding protein-encoding genes belonging to the LexA regulon.

For the above reason, we created several derivatives of V. cholerae reporter strains and showed that overexpression of Ssb drastically reduced the efficiency of (+)attPCTX integration. Similarly, like others, we also observed that the presence of RstB promotes (+)attPCTX integration. In vivo, RstB might compete with Ssb and help (+)attPCTX in maintenance of the double-fork hairpin structure, which is crucial for CTXϕ integration. It is interesting to note that although LexA represses both genes, the repression levels are not identical for the two. After infection, the ssDNA genome of CTXϕ converted to replicative double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). V. cholerae cells maintain several copies of replicative CTXϕ genomes, and hence there are multiple copies of rstB genes. This possibly helps the phage to produce an adequate amount of RstB to compete with Ssb. This scenario is not similar to production of the extrachromosomal CTXϕ genome from the integrated phage genome. Derepression of RstA is crucial for CTXϕ production, and thus LexA cleavage favors prophage replication (22), (27).

On the other hand, our results show that the presence or absence of RecA does not significantly influence (+)attPCTX integration. Several studies demonstrated that the affinity of RecA for purine-rich DNA sequence, which is very dominant in the spacer region of (+)attPCTX, and folded ssDNA is very poor. Both features limit RecA-ssDNA nucleoprotein filament formation (13). The RecA-ssDNA nucleoprotein filament is essential to induce the latent protease activity of LexA for its autocleavage and for initiation of the SOS response. This could possibly explain how the ssDNA genome of CTXϕ bypasses the cellular SOS response and integrates efficiently in the chromosome.

Conclusion.

This study has revealed that in contrast to most other ssDNA filamentous phages, CTXϕ makes use of the LexA repressor for efficient lysogenic conversion of the host. The purine-rich folded (+)attPCTX structure possibly limits RecA binding, and thus, in the absence of RecA-ssDNA-ATP nucleoprotein filament, LexA keeps repressed the expression of several DNA repair proteins, including Ssbs, and helps CTXϕ integration. LexA also represses expression of RstB, but due to multiple copy numbers of the replicating genome of CTXϕ, its optimal level is possibly not limited.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank F. X. Barre and Christophe Possoz, I2CB-CNRS, France, for the generous gift of plasmids, support, and critical reading of the manuscript. We acknowledge Rajkumar Halder, DDRC, THSTI, and Rupak K. Bhadra, CSIR-IICB, Kolkata, for their valuable suggestions and critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Bipasa Saha, Naveen Kumar, and Mayanka Dayal for their excellent technical assistance.

The work was supported by the Department of Biotechnology (grant no. BT/MB/THSTI/HMC-SFC/2011), GOI.

We declare no conflict of interest.

B.D. conceived and designed the experiments; B.D., A.P., A.D., S.B., O.M., P.K., and S.S. performed the experiments; B.D. and A.P. analyzed the data; G.B.N. contributed reagents, materials, and analysis tools; and B.D. and G.B.N. contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Funding Statement

The funder had no role in study design, data collection analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Waldor MK, Mekalanos JJ. 1996. Lysogenic conversion by a filamentous phage encoding cholera toxin. Science 272:1910–1914. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Val ME, Bouvier M, Campos J, Sherratt D, Cornet F, Mazel D, Barre FX. 2005. The single-stranded genome of phage CTX is the form used for integration into the genome of Vibrio cholerae. Mol Cell 19:559–566. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Das B, Bischerour J, Val ME, Barre FX. 2010. Molecular keys of the tropism of integration of the cholera toxin phage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:4377–4382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910212107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das B. 2014. Mechanistic insights into filamentous phage integration in Vibrio cholerae. Front Microbiol 650:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waldor MK, Rubin EJ, Pearson GD, Kimsey H, Mekalanos JJ. 1997. Regulation, replication, and integration functions of the Vibrio cholerae CTXphi are encoded by region RS2. Mol Microbiol 24:917–926. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3911758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chun J, Grim CJ, Hasan NA, Lee JH, Choi SY, Haley BJ, Taviani E, Jeon YS, Kim DW, Lee JH, Brettin TS, Bruce DC, Challacombe JF, Detter JC, Han CS, Munk AC, Chertkov O, Meincke L, Saunders E, Walters RA, Huq A, Nair GB, Colwell RR. 2009. Comparative genomics reveals mechanism for short-term and long-term clonal transitions in pandemic Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:15442–15447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907787106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baharoglu Z, Mazel D. 2014. SOS, the formidable strategy of bacteria against aggressions. FEMS Microbiol Rev 38:20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bikard D, Loot C, Baharoglu Z, Mazel D. 2010. Folded DNA in action: hairpin formation and biological functions in prokaryotes. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 74:570–588. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00026-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falero A, Caballero A, Ferran B, Izquierdo Y, Fando R, Campos J. 2009. DNA binding proteins of the filamentous phages CTXphi and VGJphi of Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol 191:5873–5876. doi: 10.1128/JB.01206-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frost LS, Leplae R, Summers AO, Toussaint A. 2005. Mobile genetic elements: the agents of open source evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol 3:722–732. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen I, Christie PJ, Dubnau D. 2005. The ins and outs of DNA transfer in bacteria. Science 310:1456–1460. doi: 10.1126/science.1114021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Z, Yang H, Pavletich NP. 2008. Mechanism of homologous recombination from the RecA-ssDNA/dsDNA structures. Nature 453:489–484. doi: 10.1038/nature06971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bar-Ziv R, Libchaber A. 2001. Effects of DNA sequence and structure on binding of RecA to single-stranded DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:9068–9073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151242898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shlyakhtenko LS, Lushnikov AY, Miyagi A, Lyubchenko YL. 2012. Specificity of binding of single-stranded DNA-binding protein to its target. Biochemistry 51:1500–1509. doi: 10.1021/bi201863z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Courcelle J, Khodursky A, Peter B, Brown PO, Hanawalt PC. 2001. Comparative gene expression profiles following UV exposure in wild-type and SOS-deficient Escherichia coli. Genetics 158:41–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heidelberg JF, Eisen JA, Nelson WC, Clayton RA, Gwinn ML, Dodson RJ, Haft DH, Hickey EK, Peterson JD, Umayam L, Gill SR, Nelson KE, Read TD, Tettelin H, Richardson D, Ermolaeva MD, Vamathevan J, Bass S, Qin H, Dragoi I, Sellers P, McDonald L, Utterback T, Fleishmann RD, Nierman WC, White O, Salzberg SL, Smith HO, Colwell RR, Mekalanos JJ, Venter JC, Fraser CM. 2000. DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature 406:477–483. doi: 10.1038/35020000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butala M, Zgur-Bertok D, Busby SJ. 2009. The bacterial LexA transcriptional repressor. Cell Mol Life Sci 66:82–93. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8378-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang AP, Pigli YZ, Rice PA. 2010. Structure of the LexA-DNA complex and implications for SOS box measurement. Nature 466:883–886. doi: 10.1038/nature09200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Butala M, Klose D, Hodnik V, Rems A, Podlesek Z, Klare JP, Anderluh G, Busby SJ, Steinhoff HJ, Zgur-Bertok D. 2011. Interconversion between bound and free conformations of LexA orchestrates the bacterial SOS response. Nucleic Acids Res 39:6546–6557. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erill I, Campoy S, Barbe J. 2007. Aeons of distress: an evolutionary perspective on the bacterial SOS response. FEMS Microbiol Rev 31:637–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogawa T, Yu X, Shinohara A, Egelman EH. 1993. Similarity of the yeast RAD51 filament to the bacterial RecA filament. Science 259:1896–1899. doi: 10.1126/science.8456314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quinones M, Kimsey HH, Waldor MK. 2005. LexA cleavage is required for CTX prophage induction. Mol Cell 17:291–300. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baharoglu Z, Mazel D. 2011. Vibrio cholerae triggers SOS and mutagenesis in response to a wide range of antibiotics: a route towards multiresistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:2438–2441. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01549-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Das B, Bischerour J, Barre FX. 2011. Molecular mechanism of acquisition of the cholera toxin genes. Indian J Med Res 133:195–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Das B, Bischerour J, Barre FX. 2011. VGJphi integration and excision mechanisms contribute to the genetic diversity of Vibrio cholerae epidemic strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:2516–2521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017061108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Midonet C, Das B, Paly E, Barre FX. 2014. XerD-mediated FtsK-independent integration of TLCvarphi into the Vibrio cholerae genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kimsey HH, Waldor MK. 2009. Vibrio cholerae LexA coordinates CTX prophage gene expression. J Bacteriol 191:6788–6795. doi: 10.1128/JB.00682-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mazel D. 2006. Integrons: agents of bacterial evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol 4:608–620. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Das B, Martinez E, Midonet C, Barre FX. 2013. Integrative mobile elements exploiting Xer recombination. Trends Microbiol 21:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lusetti SL, Cox MM. 2002. The bacterial RecA protein and the recombinational DNA repair of stalled replication forks. Annu Rev Biochem 71:71–100. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.083101.133940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Das B, Kumari R, Pant A, Sen Gupta S, Saxena S, Mehta O, Nair GB. 2014. A novel, broad-range, CTXφ-derived stable integrative expression vector for functional studies. J Bacteriol 196:4071–4080. doi: 10.1128/JB.01966-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Demarre G, Guerout AM, Matsumoto-Mashimo C, Rowe-Magnus DA, Marliere P, Mazel D. 2005. A new family of mobilizable suicide plasmids based on broad host range R388 plasmid (IncW) and RP4 plasmid (IncPalpha) conjugative machineries and their cognate Escherichia coli host strains. Res Microbiol 156:245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guzman LM, Belin D, Carson MJ, Beckwith J. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J Bacteriol 177:4121–4130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skorupski K, Taylor RK. 1996. Positive selection vectors for allelic exchange. Gene 169:47–52. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00793-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Philippe N, Alcaraz JP, Coursange E, Geiselmann J, Schneider D. 2004. Improvement of pCVD442, a suicide plasmid for gene allele exchange in bacteria. Plasmid 51:246–255. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]