Abstract

Objectives

To characterise pregnancy course and outcomes in women with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy (ARVD/C).

Methods

From a combined Johns Hopkins/Dutch ARVD/C registry, we identified 26 women affected with ARVD/C (by 2010 Task Force Criteria) during 39 singleton pregnancies >13 weeks (1–4 per woman). Cardiac symptoms, treatment and episodes of sustained ventricular arrhythmias (VAs) and heart failure (HF) ≥ Class C were characterised. Obstetric outcomes were ascertained. Incidence of VA and HF were compared with rates in the non-pregnant state. Long-term disease course was compared with 117 childbearing-aged female patients with ARVD/C who had not experienced pregnancy with ARVD/C.

Results

Treatment during pregnancy (n=39) included β blockers (n=16), antiarrhythmics (n=6), diuretics (n=3) and implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) (n=28). In five pregnancies (13%), a single VA occurred, including two ICD-terminated events. Arrhythmias occurred disproportionately in probands without VA history (p=0.045). HF, managed on an outpatient basis, developed in two pregnancies (5%) in women with pre-existing overt biventricular or isolated right ventricular disease. All infants were live-born without major obstetric complications. Caesarean sections (n=11, 28%) had obstetric indications, except one (HF). β Blocker therapy was associated with lower birth weight (3.1±0.48 kg vs 3.7±0.57 kg; p=0.002). During follow-up children remained healthy (median 3.4 years), and mothers were without cardiac mortality or transplant. Neither VA nor HF incidence was significantly increased during pregnancy. ARVD/C course (mean 6.5±5.6 years) did not differ based on pregnancy history.

Conclusions

While most pregnancies in patients with ARVD/C were tolerated well, 13% were complicated by VA and 5% by HF.

Introduction

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy (ARVD/C) is an inherited cardiomyopathy, characterised by fibro-fatty replacement of the right ventricular (RV) myocardium, which predisposes patients to ventricular arrhythmias (VAs), RV dysfunction and an increased risk of sudden cardiac death.1 2 Patients typically present in their second to fifth decade with symptoms associated with VAs.3 Inheritance of ARVD/C is autosomal dominant with reduced penetrance and marked variable expressivity.4 5 Consistent with this, ARVD/C is equally common in men and women, although men have a somewhat worse disease course.3 5 Mutations, primarily in genes encoding the cardiac desmosome, can be identified in up to two-thirds of patients.6

Although ARVD/C is frequently diagnosed in childbearing-aged women,6 little is known about pregnancy and ARVD/C. Published data are limited to one small case series and seven isolated case reports7–14 describing a total of 13 pregnancies. Thus, beyond appreciation that there are likely risks associated with the hemodynamic and hormonal changes of pregnancy,15 little disease-specific data exist to guide obstetric care of patients with ARVD/C. Taking advantage of a combined registry of American and Dutch patients with ARVD/C, we therefore developed a study to (1) characterise pregnancy course and outcomes in women with ARVD/C, (2) identify women at highest risk for adverse outcomes during pregnancy and (3) compare overall disease course of childbearing-aged patients who did and did not experience an ARVD/C-affected pregnancy.

Methods

Study population

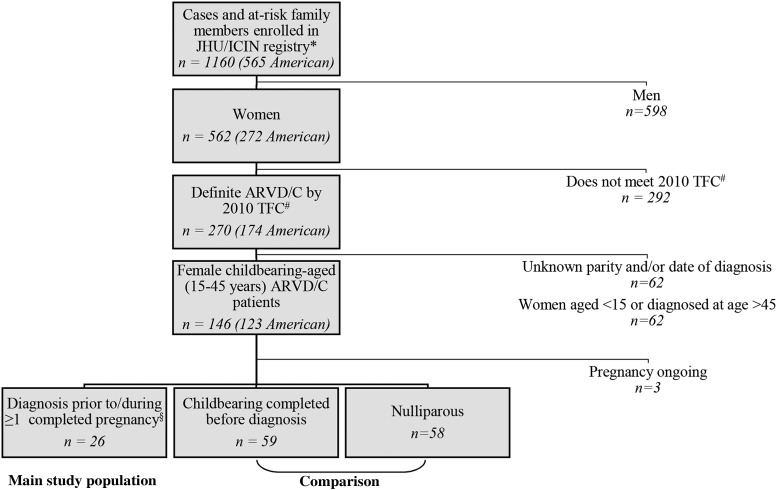

The study population was drawn from the Johns Hopkins and Interuniversity Cardiology Institute of the Netherlands ARVD/C registries. Both prospectively follow patients with ARVD/C. As shown in figure 1 and the online supplementary methods, for this study we included female registry enrolees who met diagnostic 2010 Task Force Criteria (TFC)16 while childbearing aged (15–45 years) and for whom childbearing history (parity) was available. Twenty-six women were diagnosed with ARVD/C prior to or during at least one completed pregnancy and constituted our main study population. The remaining childbearing-aged patients with ARVD/C served as a comparison group. All registry enrolees provided informed consent. The study was approved by the respective institutional review boards.

Figure 1.

Ascertainment of the study population. The study population was drawn from the Johns Hopkins arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy (ARVD/C) registry (arvd.com) and the Interuniversity Cardiology Institute of the Netherlands ARVD/C registry (*University Medical Center Utrecht, Academic Medical Center Amsterdam and University Medical Center Groningen enrolees). #Diagnosis was based on fulfilment of the 2010 Task Force Criteria.16 §First-trimester fetal loss excluded.

ARVD/C characteristics

Demographics, family history and cardiac characteristics were obtained by examination of medical records and patients’ self-report as per registry protocol (see online supplementary methods). Genotype was derived from direct sequencing of the desmosomal genes and the PLN gene through either our research17 18 or commercially available testing. ARVD/C diagnosis was established when 2010 TFC were fulfilled.

Cardiac events included: (1) sustained VA and (2) onset of heart failure (HF) ≥ Class C. Sustained VA was a composite measure of spontaneous sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT), aborted sudden cardiac death or appropriate implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) intervention, as described previously.17 In women with multiple endpoints, the first event was considered the censoring event. Onset of Class C HF was defined based on modified guidelines of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association.19

Pregnancy course and outcomes

Cardiac and obstetric course were evaluated for each ARVD/C-affected pregnancy. Maternal phenotype was assessed at evaluation preceding pregnancy with ARVD/C, during pregnancy and at last follow-up. For this assessment, major structural RV abnormalities were considered those meeting major structural TFC based on review of echocardiography, cardiac MRI and RV angiography. Left ventricular (LV) dysfunction was defined as LV ejection fraction below 55%. Cardiac treatment prior to and during each pregnancy was recorded. Each pregnancy was evaluated for VA and HF, which were collectively considered major events. New or worsening ARVD/C-related symptoms were recorded.

The primary obstetric outcome was the rate of live-born children without health issues related to pregnancy and/or delivery. For each pregnancy, gestational duration, type of delivery, birth weight, obstetric complications and perinatal health were evaluated. Maternal and child health at last clinical follow-up were also assessed.

Comparison of major events in pregnant and non-pregnant women

Likelihood of VA, HF, cardiac transplant and death at last follow-up was compared between women who had and had not experienced pregnancy with ARVD/C. Incidence rates of VA and HF in the pregnant versus non-pregnant state were also compared.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were reported as frequency (%) and compared between groups by the χ2 or Fisher's exact test. Continuous variables were summarised as either mean±SD or median (IQR) and compared across groups using a t test, or Mann–Whitney U test as appropriate. Incidence rates of VA and HF were calculated as number of first VA and HF events per person-year in the pregnant versus non-pregnant state. Mid-P exact tests were used to compare incidence rates. A p value <0.05 was considered significant. SPSS (V.22; SPSS) statistical software was used.

Results

Pregnant subjects

The main study population included 26 women (21 American) who experienced at least one viable pregnancy (>13 weeks) while affected with ARVD/C. First pregnancies began a median 1.1 years (IQR 0.5–3.8) after diagnosis. Nearly half (12/26, 46%) received genetic counselling prior to at least one pregnancy. Table 1 shows clinical characteristics at first pregnancy.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics at first pregnancy with ARVD/C

| Case | Clinically recognised ARVD/C | Proband | Mutation | Age at diagnosis (years) | Structure TFC | Tissue TFC | Depolarisation TFC | Repolarisation TFC | Arrhythmias TFC | Family history/genetics TFC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yes | Yes | PKP2 | 21 | Major | 0 | Minor | Major | Minor | Major |

| 2 | Yes | Yes | PLN | 29 | 0* | Minor | Minor | 0 | 0 | Major |

| 3 | Yes | Yes | PKP2 | 30 | Major | Minor | Minor | Major | Minor | Major |

| 4 | Yes | Yes | 0 | 29 | 0 | n/a | Minor | Major | Minor | 0 |

| 5 | Yes | Yes | 0 | 23 | 0 | n/a | Minor | Major | Minor | Major |

| 6 | Yes | Yes | 0 | 28 | Major | n/a | 0 | Major | Minor | 0 |

| 7 | Yes | Yes | 0 | 30 | Major | n/a | 0 | Major | Minor | 0 |

| 8 | Yes | Yes | 0 | 28 | Major | n/a | Minor | Major | Minor | 0 |

| 9 | Yes | Yes | n/a | 27 | 0 | n/a | n/a | Major | Minor | Minor |

| 10 | Yes | No | PKP2 | 19 | 0 | n/a | Minor | Major | Minor | Major |

| 11 | Yes | No | PKP2 | 27 | Major | n/a | Minor | 0 | Minor | Major |

| 12 | Yes | No | PKP2 | 32 | 0 | n/a | 0 | Minor | Minor | Major |

| 13 | Yes | No | PKP2 | 28 | Major | n/a | 0 | Major | Minor | Major |

| 14 | Yes | No | PKP2 | 21 | Major | n/a | 0 | 0 | Minor | Major |

| 15 | Yes | No | 0 | 32 | 0 | 0 | Minor | 0 | Minor | Major |

| 16 | Yes | No | 0 | 34 | 0 | n/a | Minor | 0 | Minor | Major |

| 17 | Yes | No | 0 | 29 | 0 | n/a | 0 | Major | Minor | Major |

| 18 | Yes | No | 0 | 31 | 0 | n/a | Minor | Major | 0 | Major |

| 19 | No | Yes | PKP2 | 22 | n/a | n/a | 0 | Major | n/a | Major |

| 20 | No | Yes | PKP2 | 22 | 0 | n/a | 0 | Major | 0 | Major |

| 21 | No | Yes | DSP and DSG2 | 31 | n/a | n/a | Minor | Major | Minor | Major |

| 22 | No | No | PKP2 | 34 | 0 | n/a | 0 | Major | n/a | Major |

| 23 | No | No | PKP2 | 31 | 0 | n/a | 0 | Major | 0 | Major |

| 24 | No | No | PKP2 | 29 | n/a | n/a | n/a | Major | Minor | Major |

| 25 | No | Yes | PKP2 | 31 | Minor | n/a | 0 | Minor | n/a | Major |

| 26 | No | No | PKP2 | 25 | Major | n/a | 0 | Major | n/a | Major |

*None.

ARVD/C, arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy; n/a, not available; TFC, 2010 ARVD/C Task Force Criteria.16

Pregnancies

These 26 women experienced 39 singleton pregnancies progressing beyond the first trimester (range 1–4, mean age 31.3±3.6) and 6 clinically recognised first trimester losses while affected with ARVD/C (table 2). The majority (n=29, 74%) of viable pregnancies began after ARVD/C was clinically recognised and treated, 7 (18%) began after the patient met TFC but ARVD/C was not yet clinically recognised and 3 (8%) pregnancies were ongoing at diagnosis. Sixteen (41%) pregnancies began in the setting of major structural RV abnormalities (n=7), history of VA (n=5) or both (n=4) and were considered potentially high risk. No pregnancy began in the setting of HF. An additional 18 pregnancies (0–4 per woman)—including three miscarriages—had been completed by these women prior to ARVD/C diagnosis without any major cardiac events.

Table 2.

Pregnancy course and outcomes

| Characteristics at start pregnancy | Obstetrics | Treatment in pregnancy | Events during pregnancy | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Maternal age | Clinically recognised ARVD/C | High-risk pregnancy | GP* | Result | Duration | Delivery | Obstetric complications | Child's age at last follow-up | Medication | ICD | Increase symptoms | VA | HF onset |

| 1 | 27 | Yes | VA+RV structure | G1P0 | Live birth | 35 weeks | Vaginal | No | 2 years | B, dose *2 | Yes | Palpitations/PVCs | No | No |

| 30 | Yes | G2P1 | Miscarriage | <13 weeks | ||||||||||

| 30 | Yes | VA+RV structure | G3P1 | Live birth | Full term | Vaginal | No | 2 months | B, add flecainide in second trimester | Yes | Palpitations/PVCs | No | No | |

| 2 | 30 | Yes | No | G2P1 | Live birth | Full term | Vaginal | No | 10 years | None | Yes | Fatigue, palpitations | No | No |

| 40 | Yes | No | G3P2 | Live birth | Full term | Vaginal | No | 12 months | Start B in 23rd week | Yes | PVCs/NSVTs | No | No | |

| 3 | 37 | Yes | VA+RV structure | G1P0 | Live birth | Full term | Vaginal | Dysmaturity | 2 years | B+ diuretics when needed | Yes | Dyspnoea, palpitations | No | Yes |

| 4 | 32 | Yes | VA | G1P0 | Live birth | Full term | C-section | No | 4 years | Sotalol | No | No | No | No |

| 33 | Yes | VA | G2P1 | Live birth | Full term | C-section | No | 2 years | Sotalol | Yes | No | No | No | |

| 36 | Yes | G3P2 | Miscarriage | <13 weeks | ||||||||||

| 5 | 29 | Yes | No | G1P0 | Live birth | 34 weeks | C-section | Preterm contractions | 1 month | Sotalol+diuretics≤7 days | Yes | Mild dyspnoea | No | No |

| 6 | 28 | Yes | RV structure | G1P0 | Live birth | Full term | Vaginal | Child: scalp laceration infection due to use of vacuum | 5 years | B; change atenolol to metoprolol | Yes | Palpitations | Third week: ICD discharge | No |

| 7 | 33 | Yes | VA+RV structure | G1P0 | Live birth | Full term | C-section | No | 9 months | B | Yes | No | No | No |

| 8 | 28 | Yes | VA | G1P0 | Live birth | Full term | Vaginal | No | 9 months | B | Yes | No | No | No |

| 9 | 29 | Yes | G1P0 | Miscarriage | <13 weeks | |||||||||

| 30 | Yes | No | G2P0 | Live birth | Full term | Vaginal | No | 4 years | B | Yes | No | No | No | |

| 31 | Yes | No | G3P1 | Live birth | Full term | Vaginal | Temporary intrauterine growth restriction | 3 years | Stop B→VA→restart B | Yes | No | 18th week: antitachycardia pacing | No | |

| 33 | Yes | VA | G4P2 | Live birth | Full term | Vaginal | 23 months | B | Yes | No | No | No | ||

| 34 | Yes | VA | G5P3 | Live birth | Full term | Vaginal | Meconium-stained amniotic fluid | 3 months | B | Yes | No | No | No | |

| 10 | 24 | Yes | No | G1P0 | Live birth | Full term | Vaginal | No | 6 years | None (stop B in 4th–8th week) | Yes | No | No | No |

| 26 | Yes | No | G2P1 | Live birth | Full term | Vaginal | Preterm contractions | 5 years | None (stop B in 4th–8th week) | Yes | No | No | No | |

| 28 | Yes | No | G3P2 | Live birth | Full term | Vaginal | No | 3 years | None (stop B in 4th–8th week) | Yes | No | No | No | |

| 11 | 31 | Yes | RV structure | G1P0 | Live birth | Full term | C-section | No | 5 years | B; stop valsartan; 22nd week: + diuretics; 32nd week: + digoxin, increase diuretics | Yes | Dyspnoea, oedema, fatigue | No | Yes |

| 12 | 33 | Yes | No | G3P1 | Live birth | Full term | Vaginal | No | 2 years | None | Yes | No | No | No |

| 13 | 30 | Yes | RV structure | G1P0 | Live birth | Full term | C-section | Child: hypoglycaemia in macrosomia | 16 years | None | Yes | No | No | No |

| 34 | Yes | G2P1 | Miscarriage | <13 weeks | No | No | ||||||||

| 35 | Yes | RV structure | G3P1 | Live birth | Full term | C-section | No | 11 years | None | Yes | No | No | No | |

| 14 | 25 | Yes | RV structure | G1P0 | Live birth | Full term | Vaginal | No | 3 years | None | Yes | No | No | No |

| 27 | Yes | G2P1 | Miscarriage | <13 weeks | No | No | ||||||||

| 28 | Yes | RV structure | G3P1 | Live birth | Full term | Vaginal | No | Newborn | None | Yes | No | No | No | |

| 15 | 32 | Yes | No | G5P2 | Live birth | Full term | Vaginal | No | 3 years | None | No | No | No | No |

| 16 | 34 | Yes | No | G2P1 | Live birth | Full term | Vaginal | No | 18 months | None | No | No | No | No |

| 17 | 32 | Yes | No | G3P2 | Live birth | Full term | Vaginal | No | 2 years | B | Yes | Palpitations/PVCs | No | No |

| 18 | 32 | Yes | No | G2P1 | Live birth | Full term | Vaginal | No | 4 months | None | No | No | No | No |

| 19 | 31 | No | No | G1P0 | Live birth | Full term | C-section | No | 9 years | None | No | No | No | No |

| 33 | No | No | G2P1 | Live birth | Full term | C-section | No | 7 years | Start B since VA | Yes | Palpitations | 12 weeks: VT | No | |

| 20 | 23 | No | No | G2P1 | Live birth | Full term | Vaginal | No | 9 years | None | No | No | No | No |

| 21 | 32 | No | No | G2P1 | Live birth | Full term | C-section | No | 18 months | Stop B in 4th week →VA→start sotalol | Yes | PVCs | 6th week: VT+short VF | No |

| 22 | 34 | No | No | G3P2 | Live birth | Full term | Vaginal | No | 6 years | None | No | No | No | No |

| 23 | 34 | No | No | G3P2 | Live birth | Full term | C-section | No | 6 years | None | No | No | No | No |

| 24 | 29 | No | No | G2P1 | Live birth | Full term | Vaginal | No | 22 years | None | No | Palpitations/PVCs | No | No |

| 31 | No | G3P2 | Miscarriage | <13 weeks | ||||||||||

| 31 | No | RV structure | G4P2 | Live birth | Full term | Vaginal | No | 19 years | None | No | Fatigue | No | No | |

| 25 | 31 | No | No | G1P0 | Live birth | Full term | Vaginal | No | 3 years | Start B since VA | Yes | No | 6 weeks: VT | No |

| 32 | Yes | No | G2P1 | Live birth | Full term | Vaginal | No | 2 years | B, dose *2 when needed | Yes | Palpitations | No | No | |

| 26 | 25 | No | No | G1P0 | Live birth | Full term | Vaginal | Meconium stained amniotic fluid | 5 years | None | No | No | No | No |

*Gravidity–parity: gravidity refers to the number of times a subject has been pregnant including the current pregnancy, parity to the number of times a subject has given birth to a fetus with a gestational age of 24 weeks or more.

ARVD/C, arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy; B, β blocker; C-section, caesarean section; GP, gravidity–parity; HF, heart failure ≥ Class C19; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; NSVT, non-sustained ventricular tachycardia; PVC, premature ventricular complex; RV structure, structural abnormalities of the right ventricle that met major structural 2010 Task Force Criteria16; VA, sustained ventricular arrhythmia or appropriate ICD therapy for a ventricular arrhythmia; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, sustained ventricular tachycardia.

Cardiac management and outcomes of ARVD/C pregnancies

Cardiac and obstetric course and medical management of each ARVD/C affected pregnancy are described in detail in table 2. Treatment during pregnancy included β blockers (n=16), antiarrhythmics (n=6), diuretics (n=3) and ICDs (n=28). ICDs were implanted during three pregnancies.

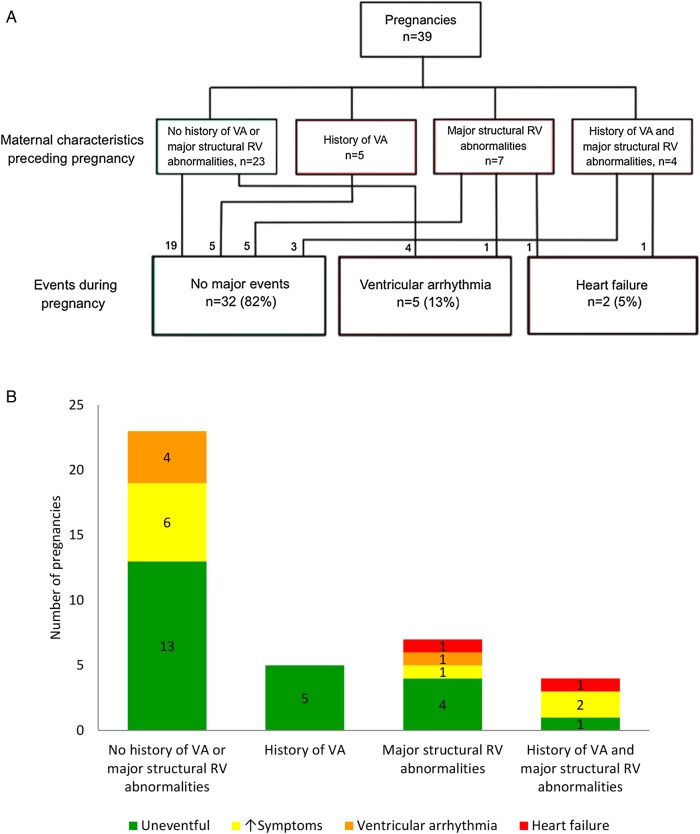

As summarised in figure 2, most pregnancies (n=32, 82%) were completed without major cardiac events (VA or HF). Among these pregnancies, nine involved new or worsening palpitations/premature ventricular complexes (n=7) and/or fatigue/dyspnoea (n=3). These symptoms were successfully treated via starting/increasing β blockers (n=3), adding flecainide (n=1) or short-term use of diuretics (n=1). In four symptomatic pregnancies (case 2—G2P1, case 17, case 24—G2P1 and G4P2), no medication adjustments were required.

Figure 2.

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy (ARVD/C) pregnancies affected by major cardiac events stratified by prepregnancy cardiac history. A. Most pregnancies were completed without major cardiac events. Heart failure ≥ Class C occurred exclusively in high-risk pregnancies begun with major structural right ventricular (RV) abnormalities (by 2010 Task Force Criteria16). Ventricular arrhythmias did not recur during pregnancy. VA, sustained ventricular arrhythmia or appropriate implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy for a ventricular arrhythmia. B. Worsening cardiac symptoms occurred in the absence of major cardiac events in 9 pregnancies.

Seven pregnancies were complicated by VA (n=5) or HF (n=2). As shown in table 3, the likelihood of a major cardiac event was not significantly increased in pregnancies begun in women with a prior history of VA and/or major structural RV abnormalities.

Table 3.

Association of major cardiac events during pregnancy with demographic, clinical and obstetric characteristics

| Overall (n=39) | Major cardiac events (n=7) | No major events (n=32) | p Value major event vs none | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VA (n=5) | HF (n=2) | ||||

| Maternal characteristics | |||||

| Age (at conception; mean, years) | 31.3±3.6 | 31.7±1.9 | 34.4±4.7 | 31.0±3.7 | 0.34 |

| Nationality (% American) | 31 (79) | 5 (100) | 1 (50) | 25 (78) | 1.0 |

| Primigravida (%) | 14 (36) | 2 (40) | 2 (100) | 10 (31) | 0.23 |

| Proband (%) | 21 (54) | 5 (100) | 1 (50) | 15 (47) | 0.10 |

| Mutation carrier (%) | 25 (64) | 3 (60) | 2 (100) | 20 (63) | 0.65 |

| ARVD/C history prepregnancy | |||||

| Recognised disease (%) | 29 (74) | 2 (40) | 2 (100) | 25 (78) | 0.34 |

| ICD implanted (%) | 25 (64) | 2 (40) | 2 (100) | 21 (66) | 0.69 |

| Cardiac characteristics prepregnancy | |||||

| Sustained VT/ICD shock (%, VA) | 9 (23) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 8 (25) | 1.0 |

| Major structural RV disease by 2010 TFC* (%) | 11/37 (30) | 1 (20) | 2 (100) | 8/30 (27)* | 0.40 |

| LV ejection fraction <55% (%) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 1 (3) | 0.33 |

| Heart failure ≥ Class C (%, HF) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0(0) | 1.0 |

| Obstetric outcomes | |||||

| Liveborn (%) | 39 (100) | 5 (100) | 2 (100) | 32 (100) | 1.0 |

| Delivery (% vaginal) | 28 (72) | 3 (60) | 1 (50) | 24 (75) | 0.38 |

| Birth weight (mean, kg)† | 3.4±0.6 | 3.0±0.4 | 2.9±1.3 | 3.5±0.6† | 0.047 |

| Full-term delivery (% ≥37 weeks) | 37 (95) | 5 (100) | 2 (100) | 30 (94) | 1.0 |

*RV structure prepregnancy was unavailable in two cases.

†Birth weight was unavailable for one full-term healthy infant.

ARVD/C, arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy; HF, heart failure ≥ Class C19; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LV, left ventricular; RV, right ventricular; TFC, 2010 Task Force Criteria16; VA, sustained ventricular arrhythmia or appropriate ICD therapy; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Ventricular arrhythmias

A single episode of VA complicated five pregnancies of five women without a prior history of sustained VAs. Interruption of β blockade was associated with two of these events.

Two VAs were terminated by appropriate ICD interventions. The first was an ICD discharge in the third week of a primigravida (case 6) who had increasingly frequent non-sustained VT prepregnancy. The second was a second trimester episode of anti-tachycardia pacing following a trial β blocker interruption. With restarted β blocker therapy this woman (case 9) completed this pregnancy without further VA and had three other uneventful pregnancies maintained on β blockers.

Three women experienced episodes of sustained VT prior to appropriate clinical recognition of their disease. Case 19 had a haemodynamically stable VT in week 12 of her second pregnancy. She was externally cardioverted, began metoprolol and received an ICD 3 days later. Case 21 had a haemodynamically unstable VT in the sixth week of her second pregnancy—2 weeks after discontinuing metoprolol. VT was terminated by cardioversion, sotalol 240 mg daily started and an ICD placed in week 22. Finally, a sustained VT in the sixth gestational week was the initial clinical presentation of a primigravida (case 25) subsequently treated with metoprolol 75 mg daily and ICD placement.

Overall, VA occurred more frequently in pregnancies of probands (5/21, 24%) than family members (0/18, 0%; p=0.05). Surprisingly, probands with no prepregnancy history of VA were most at risk (5/12 (42%) vs 0/9 (0%) probands with prepregnancy VA; p=0.045).

Heart failure

Two pregnancies of primagravidae were complicated by the onset of HF. Case 3 had a prepregnancy history of VA, major structural RV abnormalities and mild tricuspid insufficiency. She presented with dyspnoea and palpitations and was diagnosed with RV-predominant HF with severe tricuspid insufficiency in the fifth gestational month. She was successfully treated on an outpatient basis with diuretics and had an uncomplicated full-term vaginal delivery. During 2 years of follow-up, she was stable with partially improved tricuspid valve function.

Case 11 had overt biventricular disease prepregnancy (LV ejection fraction 30%–35%). Following recognition of pregnancy, she discontinued valsartan and was managed on metoprolol 25 mg daily. She developed dyspnoea, mild lower extremity oedema and increased fatigue in the fifth month and was diagnosed with biventricular HF with a decreasing LV ejection fraction (25%–30%) and mild-to-moderate pulmonary hypertension. Outpatient management was achieved with diuretics and digoxin. An uncomplicated caesarean section, indicated due to hemodynamic concerns, was performed at 39 weeks. With restart of valsartan and continued use of diuretics and digoxin, she is stable 5 years postpartum with unchanged LV function.

While HF was rare, it occurred in one of two pregnancies begun in the setting of LV dysfunction. In contrast, 9/10 (90%) pregnancies begun with major structural disease restricted to the RV were without HF.

Obstetric outcomes

All viable pregnancies progressing beyond the first trimester resulted in live-born children. Thirty-seven (95%) were delivered full term, and the other two preterm at 34 and 35 weeks. All were delivered in hospital. A total of 11 caesarean sections (28%) were performed: one exclusively for ARVD/C-related reasons (HF), the remainder for primarily obstetric indications. Minor obstetric complications (table 2) were noted in seven pregnancies (18%); no major obstetric complications occurred. As shown in table 3, birth weight was significantly lower (but normal) in pregnancies complicated by a major event (3.0±0.63 kg vs 3.5±0.57 kg no major events; p=0.047). This may be partly attributable to β blockade as birth weight was significantly lower in women taking β blockers beyond the eighth week (n=16) (3.1±0.48 kg vs 3.7±0.57 kg; p=0.002). There were no other differences in obstetric outcomes associated with major cardiac events during pregnancy. All children were alive and well at last follow-up at a median age of 3.4 years (IQR 1.6–6.8).

Association of ARVD/C course with pregnancy history

We explored whether experiencing pregnancy while affected with ARVD/C was associated with long-term disease course by comparing women who had pregnancies with ARVD/C with the remainder of our population of female childbearing-aged patients. As shown in table 4, at ARVD/C diagnosis there were no significant differences in clinical or demographic characteristics between women who later became pregnant and those who did not. After a mean 6.5±5.6 years of follow-up, there were likewise no significant differences in likelihood of having experienced a sustained VA or HF and no difference in likelihood of major RV structural dysfunction. All patients with ARVD/C who became pregnant were without cardiac mortality or transplant at last follow-up with none lost to follow-up. One woman died 1 year after her last delivery from breast cancer.

Table 4.

Association of long-term clinical course of childbearing-aged patients with ARVD/C with pregnancy history

| All (n=143) | Pregnancy with ARVD/C* (n=26) | No pregnancies while diagnosed (n=117) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Proband (%) | 83 (58) | 13 (50) | 70 (60) | 0.36 |

| Mutation carrier (%) | 95 (67) | 16 (64) | 79 (68) | 0.69 |

| European ancestry | 138 (96) | 26 (100) | 112 (96) | 0.59 |

| Clinical characteristics at diagnosis | ||||

| Age (median, IQR) | 30 (21–39) | 28 (25–32) | 31 (21–41) | 0.14 |

| Sustained VT/VF (% VA) | 50 (35) | 6 (23) | 44 (38) | 0.16 |

| Heart failure ≥ Class C (%) | 2 (1.7) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.4) | 1.0 |

| Major RV structural abnormalities by Task Force Criteria (n=132) | 54/132 (41) | 8/25 (32) | 46/107 (43) | 0.31 |

| Cardiac outcomes at last follow-up | ||||

| Sustained VT/ICD shock (% VA) | 73 (51) | 12 (46) | 61 (52) | 0.58 |

| Heart failure ≥ Class C (%) | 16 (11) | 2 (8) | 14 (12) | 0.73 |

| Major RV structural abnormalities (by TFC) | 68 (48) | 10 (39) | 58 (50) | 0.31 |

| Transplant | 3 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 3 (2.6) | 1.0 |

| Death | 4 (3) | 1 (4) | 3 (3) | 0.56 |

| Follow-up duration (mean years from diagnosis) | 6.5±5.6 | 8.2±5.3 | 6.1±5.6 | 0.08 |

*Pregnancy proceeding beyond the first trimester. ARVD/C, arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; RV, right ventricular; TFC, 2010 ARVD/C Task Force Criteria16; VA, sustained ventricular arrhythmia or appropriate ICD therapy for a ventricular arrhythmia; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Incidence rate of VAs and HF in pregnant and non-pregnant women

Finally, to test whether incidence of VA and HF was more likely during pregnancy, we compared incidence rates of both in the pregnant and non-pregnant state. Among female patients with ARVD/C aged 15–45 years, the incidence rate of VA was 0.138 (CI 0.10 to 0.18) per non-pregnant person-year versus 0.274 (CI 0.10 to 0.61) per pregnant person-year (p=0.17). For HF, the observed incidence rates were 0.020 per person-year (CI 0.012 to 0.034) in non-pregnant versus 0.070 per person-year (CI 0.012 to 0.23) in pregnant state (p=0.16).

Discussion

Main findings

We investigated cardiac and obstetric outcomes of pregnant patients with ARVD/C ascertained from two large ARVD/C registries. Our study has four main findings. First, the majority of pregnancies were without major cardiac events. Sustained VA complicated 13% of pregnancies and HF 5%. Second, pregnancies resulted in live-born infants without major obstetric concerns and all children healthy at last follow-up. Third, at last follow-up, all pregnant patients with ARVD/C were without cardiac mortality or transplant and did not differ from other childbearing-aged patients with ARVD/C. Finally, the likelihood of experiencing a first sustained VA or developing HF was not significantly increased during pregnancy.

Prior reports of pregnancy in patients with ARVD/C

Only 13 pregnancies in patients with ARVD/C have been described in the literature, in contrast to far more robust populations for other inherited cardiomyopathies and arrhythmia syndromes.20 Bauce et al7 reported six Italian patients with mild-to-moderate ARVD/C who tolerated pregnancy well. Two authors described cases diagnosed during pregnancy who following ICD implantation and initiation of β blocker therapy delivered healthy infants.8 9 Güdücu et al10 describe an established ARVD/C patient with worsening symptoms during her second pregnancy due to β blocker interruption. In contrast, two primigravidae had full-term uncomplicated pregnancies while maintained on β blockers.11 12 Finally, Iriyama et al13 and Anouar et al14 each report an uneventful pregnancy with caesarean delivery in an established patient. The results of our study confirm and significantly extend these findings as we assessed cardiac and obstetric outcomes of sixfold more pregnancies than the largest prior report.7

Most ARVD/C pregnancies were without major cardiac events

We found most pregnancies, including those begun in the setting of major structural RV abnormalities and/or a history of sustained VAs, were free from major cardiac events. Isolated episodes of VA complicated five pregnancies of probands without prepregnancy VA history. The occurrence of four of these VAs in the first trimester might be related to an arrhythmogenic effect of hormonal changes at this time.21 22 Altogether, these results suggest fairly good arrhythmic outcomes when ARVD/C is well established and treatment adequate, particularly given the typical arrhythmic course of ARVD/C.6 HF developed in the second trimester of two women with pre-existing significant structural disease as hemodynamic load increased. Of note, HF did not develop in 90% of pregnancies begun with isolated RV abnormalities.

The reason for this favourable outcome is uncertain. In patients with ARVD/C, increased hemodynamic stress associated with exercise promotes arrhythmias and also negatively modifies cardiac structure.23 In contrast to exercise, the relatively shorter term and gradually developing nature of hemodynamic load during pregnancy might limit this process. In animal models, the myocardial response to volume- or pressure-induced stress is different in male and female hearts, with preserved ejection fraction and less fibrosis in female models. In addition, the interrelationship between oestrogen and testosterone may contribute to sex differences in disease manifestation.24 Similar mechanisms may also be protective in pregnancy.

Favourable obstetric outcomes

The obstetric course of patients with ARVD/C was largely unremarkable. All pregnancies resulted in healthy children without major obstetric complications. Both prematurity (6.5% of American subjects) and birth weights were normal,25 26 although women taking β blockers or experiencing major events during pregnancy had children with a significantly lower birth weight. First trimester losses represented a normal rate of 13% of clinically recognised pregnancies.27 Of 11 caesarean sections, only one was exclusively ARVD/C indicated (HF). The 28% caesarean-section rate was unremarkable, given the population rates of 33% in the USA and 17% in the Netherlands.28

No differences in long-term ARVD/C course and incidence of cardiac events

Among women of childbearing age with ARVD/C, the incidence rate of VA and HF was not significantly elevated during pregnancy. All pregnant patients with ARVD/C were without cardiac mortality or transplant at last follow-up. Furthermore, there was no difference in likelihood of sustained VA or HF at last follow-up between these mothers and women who had not experienced pregnancy with ARVD/C. This suggests that pregnancy does not lead to a precipitous decline in most women. Some caution while interpreting these data is warranted as pregnancy is, of course, not randomly selected.

Implications for clinical care

Our results suggest most patients with ARVD/C can be managed successfully through pregnancy and highlight several management considerations. Preconception arrhythmia management should be optimised using drugs with low fetal toxicity. ICD implantation, if indicated based on prepregnancy risk stratification,6 17 should be performed prior to pregnancy. Preconception assessment of biventricular structure and function is helpful since HF is more likely in those with structural abnormalities. LV dysfunction is associated with poor pregnancy outcomes in women with dilated cardiomyopathy20 and appears likely to be so for patients with ARVD/C as well. Genetic counselling to discuss the heritable nature of ARVD/C should be offered. Following recognition of pregnancy, discontinuation of medication with low fetal risk (eg, β blockers) is not advised. Vaginal delivery with cardiac monitoring is reasonable in many cases. For uneventful pregnancies, a 3-month postpartum visit followed by usual cardiac care is recommended as pregnancy is not expected to worsen long-term disease course.

Study limitations

Data were obtained from two registries; as such, management decisions were at the discretion of the treating physician and hence vary between pregnancies and between subjects. In particular, variability in evaluation of cardiac structure and function precluded definitive analysis of possible structural progression during pregnancy. While ARVD/C management is similar in America and the Netherlands,5 6 obstetric care differs substantially which may have influenced outcomes. However, while Dutch women have high rates of care by midwives, home-births, drug-free deliveries and relatively low caesarean section rates,28 the Dutch patients with ARVD/C had medically managed pregnancies with hospital deliveries.

Our study included no women with HF diagnosed prepregnancy, a population likely at very high risk. Ascertainment of subjects through a registry of living patients also creates a selection bias that may mask catastrophic pregnancy outcomes. With regard to comparison of long-term outcomes in the overall population, women obviously self-selected whether to become pregnant and hence may differ in some systematic way beyond the data shown in table 4. In particular, a subset of women may have been advised against pregnancy, but data on medical advice given regarding childbearing are unavailable.

Conclusions

We found most pregnancies in women with ARVD/C are tolerated well. Even most patients with a prior history of sustained VAs and isolated RV structural disease had favourable outcomes. However, β-blocker therapy was associated with lower birth weight and patients with pre-existing overt biventricular disease are likely at significant risk for developing HF as pregnancy progresses.

Key messages.

What is already known on this subject?

Only 13 pregnancies in women with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy have been described in the literature in one small case series and seven case reports.

What might this study add?

We assess cardiac and obstetric outcomes of 39 pregnancies, triple the number previously reported. We also compare incidence of ventricular arrhythmias and heart failure in the pregnant and non-pregnant state, and long-term outcomes of childbearing-aged patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy (ARVD/C) who became pregnant with those who did not.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

This study significantly enhances the evidence base for patients with ARVD/C considering pregnancy and their physicians. These results suggest that most pregnancies of patients with ARVD/C are tolerated well. However, 13% of pregnancies were complicated by sustained ventricular arrhythmias and 5% by onset of heart failure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the patients with ARVD/C who have made this work possible.

Footnotes

Contributors: Each author meets the ICMJE recommended guidelines for authorship credit. There are quite a few authors as this study involved data collected over a decade in two countries. Each author revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version submitted. Each agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Specific contributions include: conception and design of the study: CAJ, JPvT, HC, SDR, MPvdB, KYvS-Z, DPJ and CT; acquisition and analysis of data: CAJ, ARH, ASJMtR, JAG, ACS, AAW, HT, DPJ, RNWH, HC, JPvT, CT and BM; interpretation of data: CAJ, ARH, ASJMtR, MPvdB, AAW, DPJ, SDR, RNWH, HC, JPvT, KYvS-Z, CT and BM; drafting the work: ARH, CAJ, JPvT and ASJMtR.

Funding: The Johns Hopkins ARVD/C Program is supported by the Leyla Erkan Family Fund for ARVD Research, the Dr. Satish, Rupal and Robin Shah ARVD Fund at Johns Hopkins, the Bogle Foundation, the Dr. Francis P. Chiaramonte Private Foundation, the Healing Hearts Foundation, the Campanella family, the Patrick J. Harrison Family, the Peter French Memorial Foundation and the Wilmerding Endowments. The authors also wish to acknowledge funding from the St. Jude Medical Foundation (investigator-initiated grant to HC, salary support for CAJ and CT). This work was performed during ASJMtR's tenure as the Mark Josephson and Hein Wellens Research Fellow of the Heart Rhythm Society. We acknowledge the support from the Netherlands Cardiovascular Research Initiative, the Dutch Heart Foundation, Dutch Federation of University Medical Centers, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development and the Royal Netherlands Academy of Sciences (AAW, MPvdB and JPvT).

Competing interests: HC is a consultant for Medtronic, Inc. and St. Jude Medical and receives research funding from the St. Jude Medical Foundation and Boston Scientific Corp. CAJ and CT receive salary support from these grants.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Johns Hopkins Medicine IRB, Ethics boards of University Medical Center Utrecht, University Medical Center Groningen and the Academic Medical Center—Amsterdam.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Details of ARVD/C Task Force Criteria are available from the corresponding author pending appropriate data use agreements.

References

- 1.Marcus FI, Fontaine GH, Guiraudon G, et al. . Right ventricular dysplasia: a report of 24 adult cases. Circulation 1982;65:384–98. 10.1161/01.CIR.65.2.384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corrado D, Thiene G, Nava A, et al. . Sudden death in young competitive athletes: clinicopathologic correlations in 22 cases. Am J Med 1990;89:588–96. 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90176-E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalal D, Nasir K, Bomma C, et al. . Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia: a United States experience. Circulation 2005;112:3823–32. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.542266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray B. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy (ARVD/C): a review of molecular and clinical literature. J Genet Couns 2012;21:494–504. 10.1007/s10897-012-9497-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhonsale A, Groeneweg JA, James CA, et al. . Impact of genotype on clinical course in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy-associated mutation carriers. Eur Heart J 2015;36:847–55. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Groeneweg JA, Bhonsale A, James CA, et al. . Clinical presentation, long-term follow-up, and outcomes of 1001 arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy patients and family members. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2015;8:437–46. 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.114.001003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauce B, Daliento L, Frigo G, et al. . Pregnancy in women with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2006;127:186–9. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doyle NM, Monga M, Montgomery B, et al. . Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy with implantable cardioverter defibrillator placement in pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2005;18:141–4. 10.1080/14767050500226500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agir A, Bozyel S, Celikyurt U, et al. . Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy in pregnancy. Int Heart J 2014;55:372–6. 10.1536/ihj.13-255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Güdücu N, Kutay SS, Ozenç E, et al. . Management of a rare case of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia in pregnancy: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2011;5:300 10.1186/1752-1947-5-300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee LC, Bathgate SL, Macri CJ. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia in pregnancy: a case report. J Reprod Med 2006;51:725–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cozzolino M, Perelli F, Corioni S, et al. . Successful obstetric management of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2014;78:266–71. 10.1159/000364870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iriyama T, Kamei Y, Kozuma S, et al. . Management of patient with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy during pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2013;39:390–4. 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2012.01954.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anouar J, Mohamed S, Kamel K. Management of a rare case of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia in pregnancy: a case report. Pan Afr Med J 2014;19:246 10.11604/pamj.2014.19.246.3773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Tintelen JP, Pieper PG, Van Spaendonck-Zwarts KY, et al. . Pregnancy, cardiomyopathies, and genetics. Cardiovasc Res 2014;101:571–8. 10.1093/cvr/cvu014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marcus FI, McKenna WJ, Sherrill D, et al. . Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: proposed modification of the task force criteria. Circulation 2010;121:1533–41. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.840827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhonsale A, James CA, Tichnell C, et al. . Risk stratification in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy-associated desmosomal mutation carriers. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2013;6:569–78. 10.1161/CIRCEP.113.000233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Groeneweg JA, van der Zwaag PA, Olde Nordkamp LR, et al. . Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy according to revised 2010 task force criteria with inclusion of non-desmosomal phospholamban mutation carriers. Am J Cardiol 2013;112:1197–206. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hunt SA, Baker DW, Chin MH, et al. . ACC/AHA guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1995 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure). Circulation 2001;104:2996–3007. 10.1161/hc4901.102568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krul SP, van der Smagt JJ, van den Berg MP, et al. . Systematic review of pregnancy in women with inherited cardiomyopathies. Eur J Heart Fail 2011;13:584–94. 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Regitz-Zagrosek V, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Borghi C, et al. , European Society of Gynecology (ESG), Association for European Paediatric Cardiology (AEPC), German Society for Gender Medicine (DGesGM). ESC guidelines on the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy: the Task Force on the Management of Cardiovascular Diseases during Pregnancy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2011;32:3147–97. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oral E, Genç MR. Hormonal monitoring of the first trimester of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2004;31:767–78. 10.1016/j.ogc.2004.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sawant AC, Bhonsale A, te Riele AS, et al. . Exercise has a disproportionate role in the pathogenesis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy in patients without desmosomal mutations. J Am Heart Assoc 2014;3:e001471 10.1161/JAHA.114.001471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyer S, van der Meer P, van Tintelen JP, et al. . Sex differences in cardiomyopathies. Eur J Heart Fail 2014;16:238–47. 10.1002/ejhf.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blencowe H, Cousens S, Oestergaard MZ, et al. . National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications. Lancet 2012;379:2162–72. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60820-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems—10th revision (ICD-10) Version: 2015; disorders related to length of gestation and fetal growth (P05-P08). http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2015/en#/P05-P08 (accessed 11 Jun 2015).

- 27.Delabaere A, Huchon C, Deffieux X, et al. . Epidemiology of loss pregnancy. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 2014;43:764–75. 10.1016/j.jgyn.2014.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization. World Health Statistics reports 2014. http://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/EN_WHS2014_Part3.pdf?ua=1 (accessed 27 Apr 2015).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.