Abstract

Abilities related to musical aptitude appear to have a long history in human evolution. To elucidate the molecular and evolutionary background of musical aptitude, we compared genome-wide genotyping data (641 K SNPs) of 148 Finnish individuals characterized for musical aptitude. We assigned signatures of positive selection in a case-control setting using three selection methods: haploPS, XP-EHH and FST. Gene ontology classification revealed that the positive selection regions contained genes affecting inner-ear development. Additionally, literature survey has shown that several of the identified genes were known to be involved in auditory perception (e.g. GPR98, USH2A), cognition and memory (e.g. GRIN2B, IL1A, IL1B, RAPGEF5), reward mechanisms (RGS9), and song perception and production of songbirds (e.g. FOXP1, RGS9, GPR98, GRIN2B). Interestingly, genes related to inner-ear development and cognition were also detected in a previous genome-wide association study of musical aptitude. However, the candidate genes detected in this study were not reported earlier in studies of musical abilities. Identification of genes related to language development (FOXP1 and VLDLR) support the popular hypothesis that music and language share a common genetic and evolutionary background. The findings are consistent with the evolutionary conservation of genes related to auditory processes in other species and provide first empirical evidence for signatures of positive selection for abilities that contribute to musical aptitude.

Human abilities to appreciate and practice music are well preserved in evolution1,2,3. The discovery of 40,000-year old flutes in recent archaeological excavations has suggested that recognizable musical behaviours must have existed several years before that4. An inter-species evolutionary background of musical behaviour has also been suggested3. What are the reasons for the existence of music and musical abilities throughout human history?Are there any genetic alleles that transmit musical practices through generations?

The majority of human-specific traits, including advanced cognitive abilities, are thought to have evolved as a result of positive selection5. Favourable alleles proliferate in the gene pool showing high allele frequencies associated with the beneficial trait, whereas damaging alleles that might cause harmful effects to the trait may disappear from the gene pool. Alleles under positive selection increase in prevalence in a population, leaving “signatures” or patterns of genetic variation on the DNA sequence6. Therefore, the identification of genes/regions under positive selection would provide novel insights into the molecular genetic background of human-specific traits7. Studies on the positive selection signals in human evolution have identified genes underlying wide spectrum of biological functions like dietary adaptation, physical appearance, behaviour, sensory systems and cognitive abilities7. For example, genes associated with cognition-related traits like visual perception, language, speech and song-learning (e.g. opsin genes and FOXP2) have been found to be under positive selection in human evolution8,9.

Musical aptitude is fundamental and necessary for many music related activities including for example creativity in music, music performance and dance. Here, we have applied genomic and bioinformatics approaches to assign the regions of positive selection associated with musical aptitude in the human genome. Musical aptitude relies upon the ability to perceive and understand intensity, pitch, timbre and tone duration, as well as the rhythm and structure they form in music. In genetic terms, it represents a complex cognitive trait in humans. Previously, we have performed a genome-wide linkage and association study with musical aptitude, which identified genes related to inner-ear development and cognition as being crucial for musical aptitude10. Here, we used three metrics, two haplotype-based methods haploPS11 and XP-EHH12, and the allele frequency-based method FST13 to identify subject-specific, genome-wide differential positive selection signals in musical aptitude.

Results

Candidate selection regions identified by haploPS

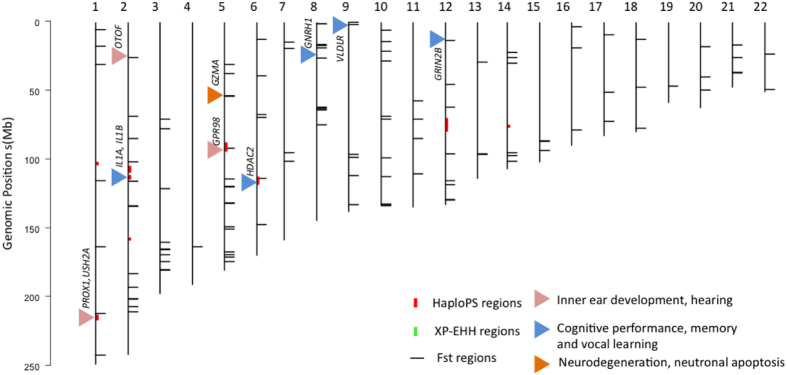

With 74 cases and 74 controls (Table 1, Supplementary Table S1), haploPS identified 46 candidate selection regions in the cases at 5% significance threshold and 86 selection regions in the controls at 10% significance threshold. Case specific signals are those identified at 5% significance level in the cases but are still absent at 10% significance threshold in the controls. Twelve case specific selection regions were identified (Fig. 1 and Table 2).

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants.

| Cases | Controls | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| COMB | Min | 125 | 76 |

| Max | 148 | 117.25 | |

| Mean | 137.41 | 100.30 | |

| Age | Min | 18 | 13 |

| Max | 70 | 86 | |

| Mean | 44.41 | 44.99 | |

| Gender | Males | 38 | 27 |

| Females | 36 | 47 |

Figure 1. Selection regions identified by haploPS, XP-EHH and Fst.

The red bars denote case specific regions identified by haploPS, green bars denotes the regions identified by XP-EHH in case. Fst selection regions are denoted as black lines. Genes with functions that are relevant to music aptitude such as hearing, cognitive performance and neurodegenerative functions are marked by triangles.

Table 2. Case specific selection signals identified by haploPS.

| Chr | Start position | End position | Genetic Distance(cM) | Adjustd haploPS P-value | Estimated frequency | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 213862164 | 216608268 | 3.269 | 0.0391 | 0.05 | LINC00538, PROX1, SMYD2, PTPN14, CENPF, KCNK2, KCTD3, USH2A |

| 1 | 102959259 | 103763252 | 0.356 | 0.0292 | 0.4 | COL11A1 |

| 2 | 158193407 | 158291539 | 0.176 | 0.0197 | 0.9 | CYTIP |

| 2 | 112409842 | 113989236 | 1.360 | 0.0342 | 0.1 | ANAPC1, MERTK, TMEM87B, FBLN7, ZC3H8, ZC3H6, RGPD8, TTL, POLR1B, CHCHD5, FLJ42351, SLC20A1, CKAP2L, IL1A, IL1B, IL37, IL36G, IL36A, IL36B, IL36RN, IL1F10, IL1RN, PSD4, PAX8 |

| 2 | 105982753 | 109034995 | 3.846 | 0.0115 | 0.05 | FHL2, LOC285000, NCK2, C2orf40, UXS1, PLGLA, RGPD3, ST6GAL2, LOC729121, RGPD4, SLC5A7, SULT1C3, SULT1C2, SULT1C2P1, SULT1C4 |

| 5 | 175136782 | 175202064 | 0.310 | 0.0373 | 0.9 | |

| 5 | 89001243 | 93774632 | 3.206 | 0.0378 | 0.05 | MIR3660, CETN3, MBLAC2, POLR3G, LYSMD3, GPR98, LUCAT1, ARRDC3, ARRDC3, NR2F1, NR2F1, MIR548AO, FAM172A, MIR2277, POU5F2, KIAA0825 |

| 6 | 113555945 | 117792143 | 2.872 | 0.0280 | 0.05 | MARCKS, LOC285758, FLJ34503, HDAC2, HS3ST5, FRK, TPI1P3, NT5DC1, COL10A1, TSPYL4, TSPYL1, DSE, FAM26F, TRAPPC3L, FAM26E, FAM26D, RWDD1, RSPH4A, ZUFSP, KPNA5, FAM162B, GPRC6A, RFX6, VGLL2, ROS1 |

| 12 | 76280316 | 79305654 | 4.981 | 0.0077 | 0.05 | PHLDA1, NAP1L1, BBS10, OSBPL8, ZDHHC17, CSRP2, E2F7, NAV3, SYT1 |

| 12 | 71139664 | 76116463 | 4.088 | 0.0053 | 0.05 | PTPRR, TSPAN8, LGR5, ZFC3H1, THAP2, TMEM19, RAB21, TBC1D15, MRS2P2, TPH2, TRHDE, TRHDE, LOC100507377, ATXN7L3B, KCNC2, CAPS2, GLIPR1L1, GLIPR1L2, GLIPR1, KRR1 |

| 14 | 76064624 | 76439634 | 0.246 | 0.0440 | 0.6 | FLVCR2, C14orf1, TTLL5, TGFB3 |

| 17 | 63154324 | 63353913 | 0.343 | 0.0362 | 0.55 | RGS9 |

The best two regions were found at chromosome 12 (12q15–q21.2, haploPS P-value = 0.0053; 12q21.2, haploPS P-value = 0.0077). Both regions contained many brain-related but also other genes (Table 2). In the other resulted regions, we also identified genes with brain functions but also genes with numerous other effects, as most of the resulting haplotypes extended several megabase pairs long and included several genes. For example, the third best region at 2q12 (haploPS P-value = 0.0115) extended nearly 3 Mb and included NCK2 that is linked to the growth of neuronal cells via Robo-Slit-pathway14.

Among the rest of the 9 case specific regions, we identified a few genes that are functionally related to brain functions and hearing. The region at 2q13 containing IL1A and IL1B is found to be under selection uniquely in the cases (haploPS P-value = 0.0343). Both genes were found to affect cognition, where IL1B was associated with baseline cognitive performance among older adults, and IL1B was associated with working memory15,16. A case-specific signal on chromosome 17 (haploPS P-value = 0.0362) contained RGS9 gene, which belongs to the regulator of G-protein signaling (RGS) gene family17. The longer splice variant of RGS9 (RGS9-2) is specifically expressed in the striatum, which is involved in controlling movement, motivation, mood and reward and is known to be affected by music18,19. There is evidence for a specific functional interaction between RGS9-2 and striatal D2-like dopamine receptors20. Music-induced reward is further elucidated by the release of dopamine in the mesolimbic striatum when experiencing peak emotional arousal during music listening21.

A case specific signal on chromosome 5 (5q14.3) encapsulating the GPR98 (haploPS P-value = 0.0378), also known VLGR1, has been found to associate with Usher syndrome type 2C, whose major symptoms include sensorineural deafness. GPR98 is required for normal development of auditory hair bundles22. Furthermore, GPR98 was identified by Nam et al. to be among the 58 neurological genes evolving under positive selection specifically in songbird lineage (zebra finch), when compared to the chicken lineage, and was differentially expressed in song control nuclei of zebra finch brain suggesting a function in birdsong23. The region on chromosome 1q32.3–41 contains USH2A (haploPS P-value = 0.0391), which encodes usherin, and is responsible for most of the Usher syndrome cases that are characterized by deafness and blindness. USH2A is found to be essential in the normal development of cochlear hair cells that may in turn affect hearing sensitivity24.

Positive selection regions identified by XP-EHH

XP-EHH identified 9 selection regions in the cases, using the controls as the reference population. (Fig. 1 and Table 3) Within top signals, RAPGEF5, a member of the Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factors, was found. Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factors members are found to be enriched in the brain and act as regulators of the interplay between Rap proteins and Ras protein, which are implicated in region-specific learning and memory functions25,26. The exact function of RAPGEF5 is not clearly elucidated; however, another member of the same family, RAPGEF4, was shown to play an important role in memory retrieval25,26. Among genes within a significant selection region on chromosome 8 encapsulates the GNRH1 gene, which belongs to the hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) family. The GnRH family has been linked to hippocampal sex differences in the zebra finch and implies that the difference may contribute to sex differences in song learning and memory27. Most of the other genes had unknown function.

Table 3. Selection signals detected by XP-EHH in cases, using controls as the reference population.

| Chr | Start position | End position | peakID | Peak XP-EHH score | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 63361822 | 63567957 | 1 | 5.1412 | |

| 2 | 204833578 | 205051247 | 7 | 4.9179 | |

| 4 | 18332045 | 18553713 | 4 | 5.1927 | |

| 7 | 22010092 | 22222507 | 6 | 6.4088 | RAPGEF5 |

| 8 | 25194779 | 25406521 | 8 | 4.9747 | DOCK5, GNRH1, KCTD9, CDCA2 |

| 10 | 114980485 | 115180485 | 9 | 4.9126 | |

| 12 | 21360603 | 21569820 | 2 | 5.2474 | SLCO1B1, SLCO1A2, IAPP |

| 16 | 86307223 | 86525343 | 3 | 6.2781 | LOC146513, LINC00917, FENDRR |

| 21 | 17658842 | 17875056 | 5 | 4.9894 | LINC00478 |

Candidate selection regions identified by FST

A total of 128 significant regions were identified from the FST analysis (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S2). Of them, the top 20 signals are shown in Table 4. The most significant region detected by FST metric at 5q11.2 covers GZMA, GPX8, MCIDAS, CCNO and DHX29 genes (regional FST = 0.1393). (Fig. 1 and Table 4). The function of GZMA was implicated in the neurodegeneration mechanisms28 and was down-regulated after listening to classical music in experienced listeners in our recent study29. GRIN2B on chromosome 12 encodes a subunit of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor, a subtype of ionotropic glutamate-gated ion channel whose role is known in learning and brain plasticity. Polymorphisms in GRIN2B were found significantly associated with cognitive performance; brain structure in the temporal lobe30,31. GRIN2B is among the singing regulated transcripts, expressed in the striatum of finch32,33.

Table 4. Top 20 selection regions identified by Fst.

| Chr | Start | End | No. of snp | window.fst | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 54392373 | 54563480 | 38 | 0.139 | GZMA,CDC20B,GPX8,MIR449A,MIR449B,MIR449C,MCIDAS,CCNO,DHX29 |

| 5 | 54187813 | 54379426 | 57 | 0.136 | ESM1,GZMK |

| 5 | 120328270 | 120524720 | 40 | 0.120 | |

| 22 | 49484533 | 49683905 | 142 | 0.094 | |

| 18 | 13271319 | 13471199 | 60 | 0.088 | LDLRAD4, MIR5190 |

| 10 | 6657775 | 6857219 | 101 | 0.087 | LINC00707 |

| 1 | 18090975 | 18289252 | 76 | 0.087 | ACTL8 |

| 12 | 118885039 | 119083566 | 54 | 0.086 | |

| 13 | 96590060 | 96777428 | 19 | 0.085 | UGGT2, HS6ST3 |

| 12 | 115616511 | 115816442 | 81 | 0.085 | |

| 14 | 30395066 | 30593866 | 48 | 0.084 | PRKD1 |

| 8 | 75207653 | 75405213 | 42 | 0.083 | JPH1,GDAP1 |

| 5 | 174481433 | 174678058 | 87 | 0.082 | |

| 12 | 129547345 | 129745507 | 129 | 0.082 | TMEM132D |

| 3 | 165751527 | 165942272 | 34 | 0.081 | |

| 14 | 101743391 | 101942768 | 63 | 0.081 | |

| 20 | 49960636 | 50160035 | 71 | 0.080 | NFATC2,MIR3194 |

| 9 | 133250275 | 133442778 | 73 | 0.080 | ASS1 |

| 12 | 13927062 | 14125734 | 78 | 0.079 | GRIN2B |

| 11 | 111037249 | 111233450 | 61 | 0.079 | C11orf53,C11orf92,C11orf93,MIR4491,POU2AF1 |

Interestingly, FOXP1 on chromosome 3p13 (regional Fst 0.07361) and VLDLR chromosome 9p24.2 (regional FST = 0.0646), which are well-known genes involved in human language development and cognitive disorders were also identified34,35. The VLDLR gene is a direct target of FOXP2, which is a transcription factor identified to be critical for learned vocal-motor behaviour such as singing and speech36. VLDLR, together with FOXP2 were found to be members of singing-regulated gene networks unique to the song-specialized basal ganglia subregion, striatopallidal area X in the zebra finch. The protein product of VLDLR, very-low-density lipoprotein receptor (Vldlr) is a member of the Reelin pathway, which was identified to be underlying learned vocalization37. Overexpression of VLDLR also results in hyperactivity and impaired memory in rats38.

OTOF identified in a candidate selection region detected by FST metric (regional FST = 0.063) on chromosome 2p23, has been substantially studied for its role in hearing and multiple mutations in this gene have been reported to be associated with hearing loss39. OTOF encodes a transmembrane protein otoferlin, which was demonstrated to function in the exocytosis at the auditory inner hair cell ribbon synapse.

Gene ontology classification

Gene ontology classification (GeneTrail2, Hypergeometric distribution test, Benjamini and Yekutieli false discovery rate adjustment method40) of the genes falling within the candidate selection regions identified by HaploPS, XP-EHH and FST window statistics revealed the enrichment of genes responsible for inner ear development (DICER1, FGF20, CUX1, SPARC, KIF3A, TGFB3, LGR5, GPR98, PAX8, COL11A1, USH2A, and PROX1) (p-value 0.002) and cellular component assembly involved in morphogenesis of different organs (DICER1, PCM1, TBC1D7, KIF3A, CCNO, MCIDAS, IQCB1, FOXP1, HDAC2, BMP10, TTLL5, BBS10, RSPH4A, and PROX1) (p-value 0.002).

Discussion

In this empirical study, three metrics (haploPS, XP-EHH and FST) were used to identify positive selection regions underlying musical aptitude in the human genome. The definition of the phenotype was based on pattern recognition41 combined with sensory capacities to detect pitch and duration10. With the musical aptitude phenotypes, we partitioned the study subjects into cases (higher musical aptitude scores) and controls (lower musical aptitude scores). Regions showing differential evidence of positive selection between cases and controls were subsequently identified as candidate genomic regions of positive selection associated with COMB scores (Fig. 1).

Biological interpretation of selection regions is difficult. On one hand, the function of the majority of the genes identified in selection regions is unknown. On the other hand, haplotype based methods identify long-range haplotypes that underpin natural selection signals. The large regions may extend over multiple genes, and we are not able to underpin the actual selected gene. We have listed in the results the genes whose functions were well-studied and related to brain functions, hearing and are expressed in songbirds’ brain. However, we would like to emphasize that the genes mentioned may not represent the actual gene under selection, and more functional studies on the genes are needed to elucidate the functional importance of the selection regions. As musical aptitude is a complex cognitive trait, there is a possibility that these areas may contain genes related to other music-related phenotypes like general cognitive capacities.

Several genes affecting inner ear development (DICER1, FGF20, CUX1, SPARC, KIF3A, TGFB3, LGR5, GPR98, PAX8, COL11A1, USH2A, and PROX1) were identified to be under positive selection as observed in gene ontology analysis. The finding is plausible as the structure and function of the auditory system is very similar in modern humans and the first primates, suggesting high evolutionary conservation of auditory perception among species42,43,44.

FOXP2 has been implicated in human speech and language45 and it has been the target of positive selection during recent human evolution46. Another candidate gene VLDLR is known to be a direct target gene of human FOXP2, which is a transcription factor identified to be critical for learned vocal-motor behaviour such as singing and speech36,46. A number of studies have reported an overlap between the neural and behavioural resources of language and music47,48, thus suggesting a common evolutionary background of language and musical abilities. Our results support these findings.

Interestingly, the candidate regions contained several genes that are known to be involved in the song perception and production processes of songbirds (e.g., FOXP1, GPR98, RGS9, GRIN2B, VDLDR), which further suggest a possible evolutionary conservation of biological processes related to musical aptitude. For example, several of the candidate genes detected by FST were reported to be responsible for song learning32 and singing33 in songbirds. The findings are consistent with the convergent evolution of genes related to auditory processes and communication in other species43. In total, ~5% of the identified candidate genes were known to be responsible for vocal learning and singing in songbirds32,33. Particularly, one of the identified candidate genes GPR98, is known to be expressed in the song control nuclei of vocalizing songbird (zebra finch), and has been found to be under positive selection in songbird lineage32, thus making it a plausible candidate gene for the evolutionary advantage of human musical aptitude. The identified selection region containing GPR98 extended more than 4 Mb on chromosome 5 by haploPS (Table 2). Part of the 4 Mb region overlaps with a region identified with FST although the overlapping region does not cover GPR98. Further studies are needed to investigate whether the common selection region detected by the two methods is linked to musical aptitude. Moreover, GPR98 and USH2A genes are not only associated with hearing but also with vision. Synesthesia is a condition where one sensory stimulus can cause a sensation in other sensory stimuli. Synesthesia has been reported in musicians who can hear sounds in different colors48. This finding suggests a common molecular background of sensory perception skills.

Common region between haploPS and FST was found at chromosome 6 (haploPS P-value = 0.0280; FST = 0.06616) where MARCKS, LOC285758, FLJ34503 and HDAC2 genes were found from the shared region. Histone deacetylase 2 encoded by HDAC2 represses genes that are crucial for learning and memory by histone deacetylation and affects cognition by suppressing synaptic excitation and enhancing inhibitory synaptic function in hippocampal neurons49,50.

The reward value of music has been suggested as a reason for the possible positive selection for musical aptitudes in human evolution, where increased dopamine secretion induced by listening to music has been justified to play a role18,19,20,21. Recent genomic studies of music perception and performance have further provided evidence for genes related to dopaminergic pathways affected by listening and performing music29,51. Among these genes, the expression of RGS2 was increased after listening to music29 and RGS2 has also been implicated in song learning and singing in songbirds52. In this study, another member of the RGS-gene family, RGS9, was identified in a selection region using haploPS. Interestingly, both RGS2 and RGS9 are expressed in striatum where the strongest reward value of musical stimuli has been demonstrated53. Dorsal component of striatal regions accompanied with prefrontal cortex is activated by expectations and the fulfilment of expectations leads to dopamine release in the striatum54. In fact, the phenotype used in this study defines the ability to form expectations in music structure55,56,57,58. Thus, the RGS proteins represent novel candidate genes underlying the evolution of music, whose association with musical aptitude needs further verification.

The study population is an isolated population59, and longer stretches of haplotypes are expected than those observed in cosmopolitan populations. We cannot exclude the possibility that the observed haplotypes are characteristic to the Finnish population. HaploPS searches for signals of positive selection by first searching for long haplotypes at each haplotype frequency across the genome. Uncharacteristically long haplotypes are identified from the distribution of haplotype length and the distribution of the number of SNPs on the haplotypes to represent positive selection regions. The method has been applied to isolated populations, such as the aboriginal populations from Southeast Asia, to detect positive selection signals60. Simulations have also shown that in the presence of strong bottlenecks in European populations, the false positive rate of haploPS is still well maintained11. For example, in the extreme case where inbreeding coefficient equals 0.3, the false positive rate of haploPS is 6.7%. XP-EHH is also a haplotype-based selection method that requires a reference population to detect selection signals in the target population. In this study, using the same population controls as the reference population eliminates the potential bias that may be caused by different demographic histories of reference and target populations (Figure S1). Significant XP-EHH scores are expected to be associated with musical aptitude. For methodological differences, the resulting signals from XP-EHH were shorter than those of haploPS and thus, the regions included only a few genes. Though both methods are haplotype-based, not many overlapping signals are expected as demonstrated in previous studies11. Indeed, we did not observe common signals between the results of the two methods. Although study material was partially shared between this study and a recent genome-wide linkage and association study on musical aptitude10, the identified genomic regions did not overlap substantially. However, the genes related to the inner-ear development and cognitive processes were identified in both the studies.

The significance thresholds of the selection methods haploPS, XP-EHH and FST are the verified cutoff values and used in previous studies implementing the methods11,12. Application of selection detection methods in case-control settings help linking candidate case-specific selection regions to phenotypes under selection, and thus facilitate biological interpretations of positive selection regions. Our selected genes discussed above represent top statistically significant genes that have a link to the phenotype used in this study. At the same time, we do acknowledge the other genes that we did not discuss in the manuscript. Musical aptitude is a polygenic trait, and our study has identified multiple selection regions related to musical aptitude, using haplotype-based and frequency-based selection methods. Future direction includes applying reliable selection methods that are designed for detecting polygenic selection, once such methods are available61.

We and others3,10,62,63 have proposed that musical aptitude is necessary for the development of music culture. As genetic evolution is much slower than cultural evolution, we hypothesize that the genetic variants associated with musical aptitude have a pivotal role in the development of music culture. This is supported by studies on song learning behaviour in songbirds that have taught that the evolution of song culture is the result of a multigenerational process where the song is developed by vertical transmission in a species-specific fashion suggesting genetic constraints64. This emphasizes the importance of selection of parental singing skills and their genetic background in evolution. In parallel, musical aptitude in humans needs early exposure to music to be developed and that is mediated through teaching, imitation and other forms of social learning3,6. Our study serves as a starting point to identify molecules and pathways that contribute to the evolution of musical traits. Obviously, further studies are required to assess the crosstalk between genetic variants and the aforementioned environmental exposure of music, at different ages, in larger study materials and in different populations.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

The Ethical Committee of the Helsinki University Central Hospital approved the study and written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their parents. The methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Participants and phenotypes

We surveyed 283 unrelated Finnish subjects (age range 13–86; 40% males) where the musical aptitude of each subject was assessed using three music tests: the auditory structuring ability test (Karma Music Test, KMT)41,55 and Carl Seashore’s subtests of pitch (SP) and time discrimination (ST)56. The KMT is based on pattern recognition where small, abstract sound patterns are repeated to form hierarchic structures41. KMT measures the recognition of melodic contour, grouping, relational pitch processing, and gestalt principles55. The KMT is based on pattern recognition in a group of tones that are heard three times. The fourth time the pattern is either the same or changed that the listeners are asked to recognize55. Pattern recognition in KMT is related to cued associations in music structure and sound sequence learning also present in speech and motor sequence learning56. An example of three items belonging to KMT can be listened on http://www.hi.helsinki.fi/music/english/samples.htm. Seashore’s test for pitch (SP) measures the ability to detect the difference in pitch of two sequential tones, whereas Seashore’s test for time (ST) measures the ability to detect small differences in tone duration. The auditory structuring ability can be considered conceptionally unrelated although somewhat correlated to these sensory capacities10,41. To get a more comprehensive phenotype for musical aptitude, a combined test score (COMB; range 75–150) was introduced to represent the measured musical aptitude as a single variable, and it was computed as the sum of the three test scores after suitable adjustment to bring the scores to the same scale10. We clarify here that the definition of a fundamental human capability such as musical aptitude cannot depend on changing cultural definitions of music. The auditory structuring ability contains the ability to identify temporal aspect in time (detecting sound patterns in time) that is related to pattern recognition in many other fields like in poetry (comprising language and speech), visual Morse code and in several types of sport that would also be highly musical activities.

With the COMB phenotypes, we partitioned the study subjects into cases (higher musical aptitude scores) and controls (lower musical aptitude scores). Regions showing differential evidence of positive selection between cases and controls are subsequently identified as candidate genomic regions of positive selection associated with musical aptitude. Genes affecting COMB scores were identified to be underlying the evolution of musical aptitude in the population. To accomplish this, a linear regression was fitted between the COMB score and age of samples. The distribution of the residual is roughly normal (Shapiro-Wilk normality test p-value = 1.56 × 10−4). We defined samples with residuals smaller than −10 as controls with low COMB scores and those with residual larger than 11 as cases with high COMB scores. A total of 74 controls representing low musical aptitude and 74 cases representing high musical aptitude were obtained for downstream analysis. The COMB scores range from 75 to 150. As a result of assigning cases and controls, controls have their scores below 117.25 and cases above 125 (Table 1). PCA analysis has shown the cases and controls are homogenous to the Finnish population (Supplementary Figure S1). Variations in music test scores suggest that the predisposing alleles may have been targeted for selection.

Genotyping and quality control criteria

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood using the phenol-chloroform method. Genotyping was performed on the Illumina HumanOmniExpress 12 1.0 V SNP chip (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Genotype calls were performed with GenomeStudio. Quality control of the genotype data was performed using the PLINK software65. Of the 290 samples in the original dataset, we removed a sample from subsequent analyses if the sample exhibited any of the following: (i) more than 5% missing genotypes across all the SNPs; (ii) excess heterozygosity, which is indicative of sample contamination; (iii) a high level of identity-by-state genotypes, which is indicative of relatedness or duplicates in which case we retained only the sample in each pairing with the higher call rate. SNPs were excluded if they: (i) remained monomorphic across all samples; (ii) exhibited a minor allele frequency <5%; (iii) exhibited more than 5% missing genotypes; and (v) exhibited gross deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium as defined by PHWE < 10 7. This yielded a combined dataset of 641,417 SNPs across 283 samples.

Haplotype phasing

The phases of the haplotypes for 283 samples were estimated from the genotype data with the software Beagle version 3.3.266. This was performed with all 283 samples within a single batch run.

Positive selection analysis

We aimed to find differential positive selection signals that are present in the cases, but absent in the controls. To locate signature of positive selection, we performed genome-wide scans of selection signals using three metrics: haplotype-based methods haploPS11 and XP-EHH12, and the allele frequency based method FST13.

HaploPS is used to identify selection signals in both cases and controls, and case specific signals can then be identified from the comparison. HaploPS searches for uncharacteristically long haplotypes when compared to the rest of the haplotypes in the genome at a given frequency11. At each given focal SNP, haploPS quantifies the length of longest haplotype formed around this SNP at a pre-defined frequency based on the genetic distance spanned (in cM) and the number of SNPs on the haplotype. An empirical significance score was calculated by quantifying the relative length of each haplotype at a given frequency after scaling by the total number of regions found across the whole genome. A positive selection region was identified if the empirical measure of the region is smaller than the significance threshold of 0.05. This procedure was performed within the population across haplotype frequencies that range from 0.05 to 0.95 at a step-size of 0.05. Genomic regions identified at multiple haplotype frequencies in the same region were represented by the significant haplotype with the highest frequency in the region. Differential selection signals were defined as regions that are significant at 5% significance level in the cases, but still fail at 10% threshold in the controls.

The cross-population extended haplotype homozygosity (XP-EHH) used the control data as the reference population and cases as the target such that the XP-EHH results will represent selection signals that are specific to the cases. The XP-EHH compares the extended haplotype homozygosity between two populations at each focal SNP12. XP-EHH analyses a common set of SNPs that are present in both populations, and SNPs located within 1 Mb of a focal SNP were used to calculate the XP-EHH score, defined as the logarithm of the ratio of the area under the EHH curves for the target population to that of the reference population. The genome-wide raw XP-EHH statistics were standardized to a distribution with zero mean and unit variance. SNPs in the top 0.1% are taken as significant SNPs. Significant regions are identified by combining SNPs of significant XP-EHH scores that are less than 200 kb apart. If two SNPs both have significant XP-EHH scores and are less than 200 kb apart, then the two SNPs forms a region. More SNPs are added to the region if they are significant are less than 200 kb away from the region.

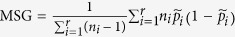

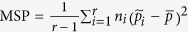

We used FST as another indicator of differential positive selection between the cases and the controls. FST quantifies the allele frequency differences between cases and controls, and regions with contiguous stretches of large FST values are expected to harbour positive selection signals. In more detail, the Weir & Hill’s FST13 was calculated between cases and controls for the 641417 SNPs with the expression FST = (MSP−MSG)/(MSP + |(n_c −1)*MSG), where  and

and  . ni is the sample size of each population. After calculating the Weir and Hill unbiased FST for all SNPs in the dataset, we divided the whole genome into 200 kb non-overlapping windows and computed a window statistic (mean FST of top 3 SNPs). Regions undergoing positive selection are expected to have large population frequency difference between cases and controls. In each window, windows with less than 5 SNPs were dropped from the analysis, and the average of the top three FST values was taken as the test statistics of the window. Based on the window statistics, we define the windows with statistics in the top 1% of the distribution as significant regions of positive selection. Regions showing differential evidence of positive selection between cases and controls were subsequently identified as candidate genomic regions of positive selection associated with musical aptitude.

. ni is the sample size of each population. After calculating the Weir and Hill unbiased FST for all SNPs in the dataset, we divided the whole genome into 200 kb non-overlapping windows and computed a window statistic (mean FST of top 3 SNPs). Regions undergoing positive selection are expected to have large population frequency difference between cases and controls. In each window, windows with less than 5 SNPs were dropped from the analysis, and the average of the top three FST values was taken as the test statistics of the window. Based on the window statistics, we define the windows with statistics in the top 1% of the distribution as significant regions of positive selection. Regions showing differential evidence of positive selection between cases and controls were subsequently identified as candidate genomic regions of positive selection associated with musical aptitude.

Gene ontology classification

The selection regions were annotated using human genome build hg19. We used Genetrail2 (http://genetrail2.bioinf.uni-sb.de/) to categorize the biological functions of the candidate genes identified by all the three methods (haploPS, XP-EHH and FST). A hypergeometric distribution test with a false discovery rate of 0.005 was used for the overrepresentation analysis. The clustering of gene families in a single candidate locus may lead to the inflated significance of some genes. To avoid this problem, overrepresented gene ontology terms were reported only if the enriched genes were detected across multiple candidate genetic loci.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Liu, X. et al. Detecting signatures of positive selection associated with musical aptitude in the human genome. Sci. Rep. 6, 21198; doi: 10.1038/srep21198 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The work is supported by the Academy of Finland (#13771), the Finnish Cultural Foundation and the Biomedicum Helsinki Foundation.

Footnotes

Author Contributions X.L. participated in the design of the study, carried out the statistical and bioinformatics data analyses and interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. C.K. performed part of the bioinformatics analyses and drafted the manuscript. J.O. participated in collecting the sample and drafted the manuscript. P.R. and L.U.-V., collected the sample and participated drafting the manuscript. K.K. participated in collecting the sample, designed the music tests and drafted the manuscript. Y.-Y.T. participated in the design of the study and supervised the statistical and bioinformatics data analyses and interpretation. I.J. conceived the idea of the study, coordinated the study, interpreted the results and drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Brown S., Merker B. & Wallin N. An introduction to evolutionary musicology. In the Origins of Music (eds. Wallin N, Merker B & Brown S.) 3–24 (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Morley I. A multi-disciplinary approach to the origins of music: perspectives from anthropology, archaeology, cognition and behaviour. J. Anthropol Sci. 92, 147–177 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honing H., Ten Cate C., Peretz I. & Trehub S. E. Without it no music: cognition, biology and evolution of musicality. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 370, 20140088 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conard N. J., Malina M. & Munzel S. C. New flutes document the earliest musical tradition in southwestern Germany. Nature 460, 737–740 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabeti P. C. et al. Positive natural selection in the human lineage. Science 312, 1614–1620 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laland K. N., Odling-Smee J. & Myles S. How culture shaped the human genome: bringing genetics and the human sciences together. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 137–148 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallender E. J. & Lahn B. T. Positive selection on the human genome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 13 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyue S. K. et al. Adaptive evolution of color vision genes in higher primates. Science 269, 1265–1267 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enard W. et al. Molecular evolution of FOXP2, a gene involved in speech and language. Nature 418, 869–72 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oikkonen J. et al. A genome-wide linkage and association study of musical aptitude identifies loci containing genes related to inner ear development and neurocognitive functions. Mol. Psychiatry 20(2), 275–82 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. et al. Detecting and characterizing genomic signatures of positive selection in global populations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 92, 866–881 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabeti P. C. et al. Genome-wide detection and characterization of positive selection in human populations. Nature 449, 913–918 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir B. S. & Hill W. G. Estimating F-statistics. Annu. Rev. Genet. 36, 721–750 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Round J. E. & Sun H. The adaptor protein Nck2 mediates Slit1-induced changes in cortical neuron morphology. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 47, 265–73 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benke K. S. et al. The association of genetic variants in interleukin-1 genes with cognition: Findings from the cardiovascular health study. Exp. Gerontol. 46, 1010–1019 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClay J. L. et al. Genome-wide pharmacogenomic study of neurocognition as an indicator of antipsychotic treatment response in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 36, 616–626 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman Z. et al. RGS9 modulates dopamine signaling in the basal ganglia. Neuron 38, 941–952 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatorre R. J. & Salimpoor V. N. From perception to pleasure: Music and its neural substrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110, Suppl 2: 10430–7 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitin D. J. & Tirovolas A. K. Current advances in the cognitive neuroscience of music. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1156, 211–231 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taymans J. M., Leysen J. E. & Langlois X. Striatal gene expression of RGS2 and RGS4 is specifically mediated by dopamine D1 and D2 receptors: Clues for RGS2 and RGS4 functions. J. Neurochem. 84, 1118–1127 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salimpoor V. N., Benovoy M., Larcher K., Dagher A. & Zatorre R. J. Anatomically distinct dopamine release during anticipation and experience of peak emotion to music. Nat Neurosci 14, 257–262 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee J. et al. The very large G-protein-coupled receptor VLGR1: a component of the ankle link complex required for the normal development of auditory hair bundles. J. Neurosci. 26, 6543–6553 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam K. et al. Molecular evolution of genes in avian genomes. Genome Biol. 11, R68 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. et al. Usherin is required for maintenance of retinal photoreceptors and normal development of cochlear hair cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 4413–4418 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki H. et al. A Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor enriched highly in the basal ganglia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 13278–83 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostroveanu A., van der Zee E. a., Eisel U. L. M., Schmidt M. & Nijholt I. M. Exchange protein activated by cyclic AMP 2 (Epac2) plays a specific and time-limited role in memory retrieval. Hippocampus 20, 1018–1026 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire N., Ferris J. K., Arckens L., Bentley G. E. & Soma K. K. Gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) and gonadotropin inhibitory hormone (GnIH) in the songbird hippocampus: regional and sex differences in adult zebra finches. Peptides 46, 64–75 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iłżecka J. Granzymes A and B levels in serum of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clin. Biochem. 44, 650–3 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanduri C. et al. The effect of listening to music on human transcriptome. PeerJ 3, e830 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milnik A. et al. Association of KIBRA with episodic and working memory: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 159 B, 958–969 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauppi K., Nilsson L.-G., Adolfsson R., Eriksson E. & Nyberg L. KIBRA Polymorphism Is Related to Enhanced Memory and Elevated Hippocampal Processing. J. Neurosci. 31, 14218–14222 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfenning A. R. et al. Convergent transcriptional specializations in the brains of humans and song-learning birds. Science 346, 1256846–1256846 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O W. et al. Core and region-enriched networks of behaviorally regulated genes and the singing genome. Science 346, 1256780 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Heston J. B., Burkett Z. D. & White S. A. Expression analysis of the speech-related genes FoxP1 and FoxP2 and their relation to singing behavior in two songbird species. J. Exp. Biol. 216, 3682–92 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdan F. F. et al. De novo mutations in FOXP1 in cases with intellectual disability, autism, and language impairment. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 87, 671–678 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernes S. C. et al. High-throughput analysis of promoter occupancy reveals direct neural targets of FOXP2, a gene mutated in speech and language disorders. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 1232–50 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard A., Miller J., Fraley E. R., Horvath S. & White S. Molecular microcircuitry underlies functional specification in a basal ganglia circuit dedicated to vocal learning. Neuron 73, 537–552 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata K. et al. Vldlr overexpression causes hyperactivity in rats. Mol. Autism 3, 11 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux I. et al. Otoferlin, Defective in a Human Deafness Form, Is Essential for Exocytosis at the Auditory Ribbon Synapse. Cell 127, 277–289 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y., Drai D., Elmer G., Kafkafi N. & Golani I. Controlling the false discovery rate in behavior genetics research. Behav. Brain Res. 125, 279–284 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karma K. Musical aptitude definition and measure validation: Ecological validity can endanger the construct validity of musical aptitude tests. Psychomusicology A J. Res. Music Cogn. 19, 79–90 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Montealegre-Z F., Jonsson T., Robson-Brown K. A., Postles M. & Robert D. Convergent evolution between insect and mammalian audition. Science 338, 968–71 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker J. et al. Genome-wide signatures of convergent evolution in echolocating mammals. Nature 502, 228–31 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- G Z. et al. Comparative genomics reveals insights into avian genome evolution and adaptation. Science (80-.). 346, 1311–1320 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai C. S., Fisher S. E., Hurst J. A., Vargha-Khadem F. & Monaco A. P. A forkhead-domain gene is mutated in a severe speech and language disorder. Nature 413, 519–23 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayub Q. et al. FOXP2 targets show evidence of positive selection in European populations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 92, 696–706 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel A. D. Language, music, syntax and the brain. Nat. Neurosci. 6, 674–681 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PK G. et al. Absolute pitch exhibits phenotypic and genetic overlap with synesthesia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 22, 2097–2104 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gräff J. et al. An epigenetic blockade of cognitive functions in the neurodegenerating brain. Nature 483, 222–226 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson J. E. et al. Histone deacetylase 2 cell autonomously suppresses excitatory and enhances inhibitory synaptic function in CA1 pyramidal neurons. J. Neurosci. 33, 5924–9 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanduri C. et al. The effect of music performance on the transcriptome of professional musicians. Sci. Rep. 5, 9506 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton D. F. The genomic action potential. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 74, 185–216 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salimpoor V. N. et al. Interactions between the nucleus accumbens and auditory cortices predict music reward value. Science (80-.). 340, 216–219 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boileau I. et al. Modeling sensitization to stimulants in humans: an [11C]raclopride/positron emission tomography study in healthy men. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 63, 1386–1395 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karma K. Auditory and Visual Temporal Structuring: How Important is Sound to Musical Thinking? Psychol. Music 22, 20–30 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Seashore C., Lewis D. & Saetveit J. Seashore Measures of Musical Talent (Revised). Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 298 (1960). [Google Scholar]

- Justus T. & Hutsler J. J. Fundamental issues in the evolutionairy psychology of music: Assessing Innateness and Domain Specificity. Music Percept. 23, 1–28 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Leaver A. M., Van Lare J., Zielinski B., Halpern A. R. & Rauschecker J. P. Brain activation during anticipation of sound sequences. J. Neurosci. 29, 2477–2485 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varilo T. et al. The age of human mutation: genealogical and linkage disequilibrium analysis of the CLN5 mutation in the Finnish population. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 58, 506–12 (1996). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Saw W.-Y., Ali M., Ong R. T.-H. & Teo Y.-Y. Evaluating the possibility of detecting evidence of positive selection across Asia with sparse genotype data from the HUGO Pan-Asian SNP Consortium. BMC Genomics 15, 332 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian W., Deng L., Lu D. & Xu S. Genome-Wide Landscapes of Human Local Adaptation in Asia. PLoS One 8 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulli K. et al. Genome-wide linkage scan for loci of musical aptitude in Finnish families: evidence for a major locus at 4q22. J Med Genet 45, 451–456 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honing H. & Ploeger A. Cognition and the Evolution of Music: Pitfalls and Prospects. Top. Cogn. Sci. 4, 513–524 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipkind D. & Tchernichovski O. Colloquium Paper: Quantification of developmental birdsong learning from the subsyllabic scale to cultural evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 108, 15572–15579 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S. et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 559–575 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning S. R. & Browning B. L. Rapid and accurate haplotype phasing and missing-data inference for whole-genome association studies by use of localized haplotype clustering. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 1084–1097 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.