Abstract

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) terminates the action of acetylcholine at cholinergic synapses thereby preventing rebinding of acetylcholine to nicotinic post-synaptic receptors at the neuromuscular junction. Here we show that AChE is not localized close to these receptors on the post-synaptic surface, but is instead clustered along the presynaptic membrane and deep in the post-synaptic folds. Because AChE is anchored by ColQ in the basal lamina and is linked to the plasma membrane by a transmembrane subunit (PRiMA), we used a genetic approach to evaluate the respective contribution of each anchoring oligomer. By visualization and quantification of AChE in mouse strains devoid of ColQ, PRiMA or AChE, specifically in the muscle, we found that along the nerve terminus, the vast majority of AChE is anchored by ColQ that is only produced by the muscle, whereas very minor amounts of AChE are anchored by PRiMA that is produced by motoneurons. In its synaptic location, AChE is therefore positioned to scavenge ACh that effluxes from the nerve by non-quantal release. AChE-PRiMA, produced by the muscle, is diffusely distributed along the muscle in extra-junctional regions.

Keywords: acetylcholinesterase, acetylcholine, Collagen Q, PRiMA, synapse structure, electron microscopy, muscle activity

Introduction

The primary function of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) is catalysis of the rapid hydrolysis of released acetylcholine (ACh). In the absence of AChE, excess ACh prolongs end plate decay in the neuromuscular junction by rebinding to postsynaptic receptors before diffusing from the synapse (Katz and Miledi, 1973; Magleby and Terrar, 1975). This excess of ACh may initially desensitize nAChR and over prolonged periods alter post-synaptic organization (post-synaptic myopathy) (Kasprzak and Salpeter, 1985) and diminish muscle strength. Several lines of evidence suggest that ACh also acts through presynaptic receptors and modulates synaptic transmission. Antidromic firing of action potentials in motor nerves is associated with AChE inhibition, and many authors have suggested that this firing results from a presynaptic action of ACh (Ferry and Kelly, 1988). On the other hand, inhibition of AChE has revealed that ACh leaks continuously from the nerve terminal through non-quantal release (NQR) driven by the vesicular acetylcholine transporter (Vyskocil et al., 2009). Indeed, the presynaptic terminal is sensitive to ACh, but whether AChE is distributed near the nerve terminal or the muscle endplate, and whether appreciable ACh concentration gradients exist within the synapse have not been established.

In muscle, AChE is found in multiple oligomeric assemblies. Early experiments demonstrated that AChE is clustered in the basal lamina mainly in post-synaptic folds (McMahan et al., 1978; Salpeter, 1969). The asymmetric or collagen-tailed forms of AChE are associated with the basal lamina through collagen Q (ColQ) subunits, each strand of triple helical ColQ organizes a tetramer of AChE subunits (Dvir et al., 2004; Krejci et al., 1997; Massoulié and Millard, 2009). Deletion of the ColQ gene in mice or ColQ mutation in humans eliminates all collagen-tailed forms from muscle, and as a result, AChE is virtually undetectable at neuromuscular junctions (NMJs) (Donger et al., 1998; Feng et al., 1999; Ohno et al., 1998). These observations suggest that the presence of AChE at the NMJ depends mainly, if not exclusively, on its association with ColQ. However, in addition to AChE-ColQ, total muscle extracts also contain AChE tetramers not associated with ColQ. Early experiments suggested that non-ColQ bound AChE tetramers accumulate in the perijunctional region around the NMJ (Gisiger and Stephens, 1988) and possibly in the nerve terminal (Leung et al., 2009). These AChE tetramers are probably associated with PRiMA, a small transmembrane protein that links AChE tetramers to the plasma membrane (Perrier et al., 2002; Xie et al., 2008).

Here we reevaluate the nature, localization, origin of AChE in the primary cleft between the nerve and the muscle. We take advantage of several strains of knockout mice in which the genes encoding the AChE catalytic subunit or its anchoring proteins were deleted or modified (Camp et al., 2008; Dobbertin et al., 2009; Feng et al., 1999). Through high resolution light and electron microscopic analyses of each knockout strain, we found that AChE isoforms are differentially distributed within the synaptic cleft and at junctional and extrajunctional locations along the muscle fiber.

Experimental Procedures

Experimental Mouse strains

Experiments were performed on four strains of mice: (1) WT mice, (2) mice nullizygous for a mutated PRiMA gene in which the domain of interaction with AChE has been deleted (PRiMA−/−) (Dobbertin et al., 2009), (3) mice nullizygous for a mutated ColQ gene in which the domain of interaction with AChE is deleted (ColQ−/−) (Feng et al., 1999), (4) mice nullizygous for AChE1irr, in which the enhanceosome region in the first intron of the AChE gene is deleted (achei1rr−/−) (Camp et al., 2008). (5) mice nullizygous for AChE, in which the sequence coding the complete catalytic domain of the AChE gene is deleted (AChE−/−) (Xie et al., 2000).

Genotypes were determined by PCR using DNA from crude tissue extracts after alkaline hydrolysis using a mix of allele specific primers and HotStart TaqDNA polymerase (Qiagen). Mice from the experimental strains were 1 to 2 months old and were of a genetic background equivalent to an F2 or F3 mating of B6 or D2 strains.

All experiments were performed in accordance with the policies of the French Agriculture and Forestry Ministry, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, and the University of California, San Diego’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (National Institutes of Health assurance number A3033-1; United States Department of Agriculture Animal Research Facility registration number 93-R-0437), and in accordance with the policy on the use of animals in neuroscience research issued by the Society for Neuroscience.

Tissue Preparation for Histological Detection of AChE

Mice were deeply anesthetized with sodium chloral hydrate. At least 5 animals per group were perfused transcardially with a mixture of 2% paraformaldehyde and 0.2% glutaraldehyde, as previously described (Bernard et al., 1999). The tibialis anterior muscle was dissected and fixed overnight in 2% paraformaldehyde. Bundles of 20 muscle fibers were teased out and treated free-floating in solution. Alternatively, 70 µm thick sections from spinal cord at the level of L2-L4 were cut on a vibrating microtome and collected in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). This lumbar spinal level was chosen because the cell bodies of motoneurons located in this region project to the tibialis anterior. The muscle fibers and spinal cord sections were cryoprotected with sucrose, freeze-thawed and stored in PBS until used.

Immunohistochemistry

AChE was detected by immunohistochemistry using two different rabbit polyclonal antibodies, one raised against rat AChE (A63) (Marsh et al., 1984), and one raised against mouse AChE (Jennings et al., 2003). AChE was detected at the NMJ at the confocal microscopic level by immunofluorescence, and at the electron microscopic level by the post-embedding immunogold method.

Immunofluorescence

AChE was stained at the NMJ either alone or in association with α-bungarotoxin (α-BTX) which was used to identify the nicotinic receptors (nAChRs) at the postsynaptic membrane of the NMJ, or with the vesicular transporter of ACh (VAChT) to identify nerve terminals. Briefly, after perfusion-fixation, muscle fibers were incubated in 4% normal donkey serum (NDS) for 30 min. For the sole detection of AChE, specimens were incubated with an anti-AChE antibody (1:1000) supplemented with 1% NDS for 15 h at room temperature. After washing, muscle fibers were incubated with an Alexa Fluor® 568 donkey anti-rabbit antibody (Molecular Probes). When AChE and nAChR were codetected, muscle fibers were incubated in a mixture of Alexa Fluor® 568 donkey anti-rabbit antibody and Alexa Fluor® 488 α-BTX (α-BTX, 30 nM) to visualize postsynaptic receptor densities. When AChE and VAChT were codetected, muscle fibers were incubated in a mixture of antibodies raised to AChE and VAChT (raised in goat, dilution: 1:500, AB1578 Chemicon) overnight at room temperature. After washing, the muscle fibers were incubated in a mixture of secondary antibodies, Alexa Fluor® 568-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit antibody for AChE and Alexa Fluor® 488-donkey anti-goat antibody for VAChT. Fibers were mounted in Vectashield. Images of randomly selected endplates were collected using a Confocal Zeiss LSM 510 microscope equipped with an oil-immersion lens (Plan-Neofluar 63x) at the SCM, université Paris Descartes microscopy facility.

Immunogold

AChE was detected at the electron microscopic level using the pre-embedding immunogold method, as previously described (Bernard et al., 1999). After perfusion-fixation, as described above, muscle fibers were incubated in 4% normal donkey serum (NDS) for 30 min and then with AChE antibody (1:1000) supplemented with 1% NDS for 15 h at room temperature. After washing, muscle fibers were incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to gold particles (1.4 nm in diameter; Nanoprobes, NY, USA, 1:100 in PBS/BSA) for 2 h. The fibers were then washed and post-fixed in 1% glutaraldehyde for 10 min. After washing in acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7), the signal of the gold immunoparticles was amplified using a silver enhancement kit (HQ silver ; Nanoprobes; NY, USA) with a 2 min incubation at RT in the dark. After treatment of sections with 1% osmium, dehydration and embedding in resin, ultrathin sections were cut, stained with lead citrate, and examined in a Philips CM120 electron microscope (Eindhoven, The Netherlands) equipped with a camera (Morada, Soft Imaging System, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

A similar procedure was used to detect fasciculin2 and α-BTX. In brief, after incubation overnight in a solution containing 0.8 µM biotinylated fasciculin2 (Krejci et al., 2006) or 30nM biotinylated α-BTX (Molecular Probes), biotin was detected using streptavidin coupled to gold particles (1.4 nm in diameter; Nanoprobes, NY, USA, 1:100 in PBS/BSA). Intensification of gold particles, fixation, embedding and observations were processed as described above. The specificity of fasciculin2 labeling was demonstrated by the absence of staining in muscles of AChE knockout mice.

Histochemical Detection of AChE

AChE was detected by histochemistry (Tago et al., 1986). Free-floating muscle fibers or spinal cord sections were first incubated for 30 min in a mixture of 60 µM CuSO4, 10 µM K3Fe(CN)6, 100 µM sodium citrate, in 0.1 M maleate buffer, pH 6.0 with 0.05 µM iso-OMPA to inhibit BChE activity (Sigma-Aldrich Chimie, St.Quentin-Fallavier, France). Muscle fibers and sections were next incubated in the same mixture supplemented with 36 µM acetylthiocholine, the substrate for AChE, at room temperature in the dark for 30 min. When the level of expression of AChE was very low, incubation was lengthened (3 h for ColQ knockout strains and 18 h for achei1rr knockout strains). Samples were thoroughly washed with several changes of 50 mM Tris-HC1 buffer (pH 7.6). Samples were then incubated for 5 min in 0.04% 3,3’-diaminobenzidine in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.6), the solution was supplemented with 0.015% H2O2, and the incubation was prolonged for 10 min at room temperature. After a brief wash with Tris-HCl buffer, the muscle fibers or sections were mounted on glass slides, air dried, and mounted and covered in Eukitt mounting medium (Freiburg, Germany). Images of randomly selected endplates and the ventral horn of the spinal cord were collected using an Olympus upright microscope (BX61) equipped with an oil-immersion lens (x 60) and a cooled video camera (Qimaging, Retiga 2000R, Burnaby, Canada) with a color conversion filter. Digitizing was accomplished using the image analysis system Image-Pro Plus (Silver Spring, USA).

Preparation of Muscles for Biochemical Analysis of AChE

Muscles were carefully dissected in oxygenated Ringer’s solution, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. To visualize the NMJ in the tibialis anterior (TA) muscle, mice were injected in the tail vein with 5 µg of fluorescent bungarotoxin (α-bungarotoxin, Alexa Fluor® 488 conjugate, B-13422, Invitrogen, France). After an hour the mice were sacrificed, and muscles were removed and kept in cold oxygenated Ringer’s solution until they were dissected under binocular optics illuminated by fluorescence. We dissected NMJ free segments of muscle (approximately 1/3 of the total muscle). Since the amount of AChE extracted from an aneural region of a single TA muscle was too low for analysis in sucrose gradients, 3 muscles were pooled. We compared aneural regions of the TA from the right leg with entire TA muscle from the left leg, because the level of G4 is highly variable between animals but identical in left and right legs from the same animal (Jasmin and Gisiger, 1990).

Biochemical Analysis of AChE

Muscles were pulverized in liquid nitrogen and transferred to a glass-glass Potter homogenizer. The proteins were extracted in 8 volumes of 10 mM HEPES pH 7.2, 0.8 M NaCl, 1% CHAPS, 10 mM EDTA, 2 mM benzamidine; in some experiments 20 µg/ml leupeptin and 40 µg/ml pepstatin were added. The extract was mixed thoroughly on a vortex mixer at 4°C for 2 h, and then centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min at 20,000 g.

AChE molecular forms were separated in 5–20% sucrose gradients containing 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, 0.8 M NaCl, 0.2% BRIJ 97, and 10 mM EDTA. The exchange of BRIJ for CHAPS allows the separation of non-amphiphilic from amphiphilic forms. To substitute BRIJ for CHAPS, a 1% final concentration of BRIJ 97 was added to each sample before loading on the gradient. The gradients were centrifuged in an SW41 rotor for 19 h at 36,000 rpm, and about 48 fractions were collected. Positions of internal sedimentation standards (β-galactosidase, 16 S and alkaline phosphatase, 6.1 S) were used to convert fraction numbers to S values. AChE activity was evaluated by the hydrolysis of 0.75 mM acetylthiocholine in the presence of 1 mM DTNB and of 10−5 M iso-OMPA. The assay medium contained 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, rather than phosphate buffer, to reduce background.

Results

Distinct subsynaptic localization of AChE and nAChR in the primary cleft of the NMJ

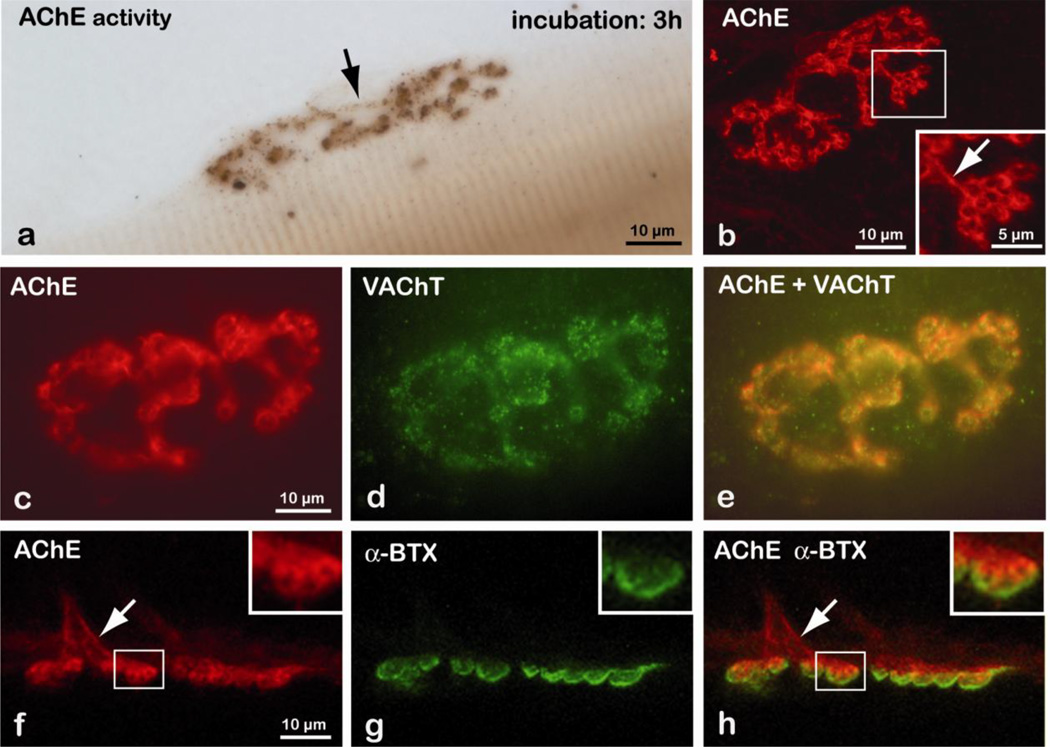

AChE is a landmark protein in the NMJ as revealed by its enzymatic activity in figure 1a and by a specific antibody in figure 1b. However, the precise distribution of AChE along the basal lamina within subsynaptic space is not resolved at the light microscopy level or by detection of the hydrolysis product, thiocholine. To localize AChE at the subsynaptic level, we used an anti-AChE antibody and visualized AChE by electron microscopy. We found two regions of synaptic localization of AChE: 1) in the primary cleft of the NMJ in close apposition to the presynaptic nerve terminal, 2) in the secondary postsynaptic endplate folds of the muscle fiber. AChE was virtually absent at the membrane crests between folds on the postsynaptic membrane (figure 1c). To comparatively analyze AChE and nAChR localization we used two homologous three-fingered peptide toxins, biotinylated bungarotoxin which binds specifically to AChR, and biotinylated fasciculin2 which binds specifically to AChE. As shown in figure 2, AChE is obviously clustered along the presynaptic membrane and in the folds whereas the nicotinic receptors are clustered at the crests of the post synaptic membrane. No labeling of AChE is seen in the terminal Schwann cells, in the intracellular area of the nerve terminal, or in the muscle cell.

Figure 1. Subcellular and Subsynaptic Localization of AChE at the NMJ.

a) AChE activity was detected by histochemistry (HC) b) AChE protein was labeled with an anti-AChE antibody by immunohistochemistry (IHC) at the light microscopic level. c) AChE detection by the immunogold method with silver intensification at the electron microscope level. Immunogold particles for AChE are located in the primary cleft and in secondary folds. In the primary cleft, particles are seen in contact with the presynaptic membrane. Nonexistent or miniscule labeling was seen on the postsynaptic membrane at the crests between the folds. In secondary folds, immunogold particles are mostly seen in association with the membrane. No labeling is associated with the terminal Schwann cells (Sc), or inside the muscle cell (mc).

Figure 2. Distinct Subsynaptic Distributions of AChE and AChR at the NMJ.

AChE and nAChR were detected using biotinylated toxins: fasciculin2 and α-bungarotoxin, respectively. Biotin was revealed at the electron microscopic level with gold-coupled streptavidin and the signal was amplified with silver intensification. Note that in the primary cleft, nAChR is located at the postsynaptic membrane, whereas AChE is clustered in association with the presynaptic membrane. t, nerve terminal and mc, muscle cell.

NMJ AChE is anchored by ColQ in the basal lamina and by PRiMA on the nerve terminal

To examine the respective contributions of PRiMA and ColQ to the localization of AChE at the NMJ, AChE was visualized in control (figure 3a, b, c) and knockout mice. In the PRiMA−/− strain, the morphology of the NMJ was unchanged and AChE staining was indistinguishable from that of the wild type mouse (figure 3e, f, g). Conversely, in the ColQ−/− strain, both morphology and AChE labeling were abnormal when compared to the wild type (figure 3i, j, k). Staining in the NMJ appeared to be fragmented, as shown by α-bungarotoxin labeling (figure 3k), and did not display the normal pretzel-like shape. AChE labeling and α-bungarotoxin labeling were superimposed, but not colocalized. The time necessary to visualize AChE histochemically in ColQ knockout mice was 3 hours vs. 30 minutes for the WT animal (figure 3i vs. 3a), indicating that quantitatively the contribution of PRiMA anchored AChE species at the NMJ is quite small. The specificity of AChE labeling was demonstrated by the absence of histochemical and immunohistochemical signals in the AChE−/− knockout animal (figure 3m, n).

Figure 3. AChE Distribution at the NMJ in WT, PRiMA−/− and ColQ−/− mice.

a,e,i,m: AChE activity is localized by histochemistry. The time of incubation is noted. AChE protein is detected using an anti-AChE polyclonal antibody (red in b, f, j, and n) and nicotinic receptors, as a marker of the post-synaptic membrane, are labeled using α-bungarotoxin (α-BTX, green in c, g, k, o). AChE and AChR labeling overlap (d,h,l,p) in WT mice (a,b,c,d) and in the PRiMA−/− knockout (e,f,g,h). In the ColQ−/− knockout, AChE activity is detected at a lower intensity (i) and labeling displays a distinctly different shape (j,k) from that seen in the WT mouse. The specificity of AChE labeling with the antibody is verified by the absence of signal in AChE−/− tissue, which is used as a control (m, n).

To further study the localization of AChE-PRiMA, NMJs of the ColQ−/− knockout mice were stained to show AChE activity histochemically, and AChE protein immunochemically. We found that AChE staining was present in round subcellular elements that appear to lie on the surface of the muscle fiber (figure 4a). Immunohistochemical analysis shows that AChE labeling is associated with both pre-terminal regions of the nerve (arrows in figure 4b, f, h) and with nerve terminals (enlargements in inset squares in 4b, f, and h). Confocal microscopy showed that AChE labeling is associated with the membranes of round-shaped structures (figure 4b). To investigate the nature of these round-shaped vesicles, the NMJs were doubly labeled with antibodies against AChE and the vesicular ACh transporter (VAChT, a marker of cholinergic nerve terminals (figure 4d, e)). We found a strict colocalization of VAChT and AChE staining, indicating that AChE-PRiMA is localized only in terminals (figure 4c, d, e). We then found that nAChR and AChE labeling are strictly dissociated (figure 4 f, g h).

Figure 4. Cellular and Subcellular Detection of AChE at the NMJ in ColQ−/− Knockout Mice.

a–b: AChE histochemical and immunohistochemical labeling are associated with pre-terminal (arrows) and terminal membranes of the motoneuron (enlargements in the inset square in b). c–e: Immunoreactivity for AChE (c, red) and for the vesicular ACh transporter (d, green). Merge of the 2 labels shows: e) colocalization of AChE with a marker of cholinergic terminals. f–h) Detection of AChE with antibody (f, red) and nicotinic postsynaptic receptors with. α-bungarotoxin (g, green). (h) Histochemistry and immunohistochemistry show a distinct localization of AChE and AChR.

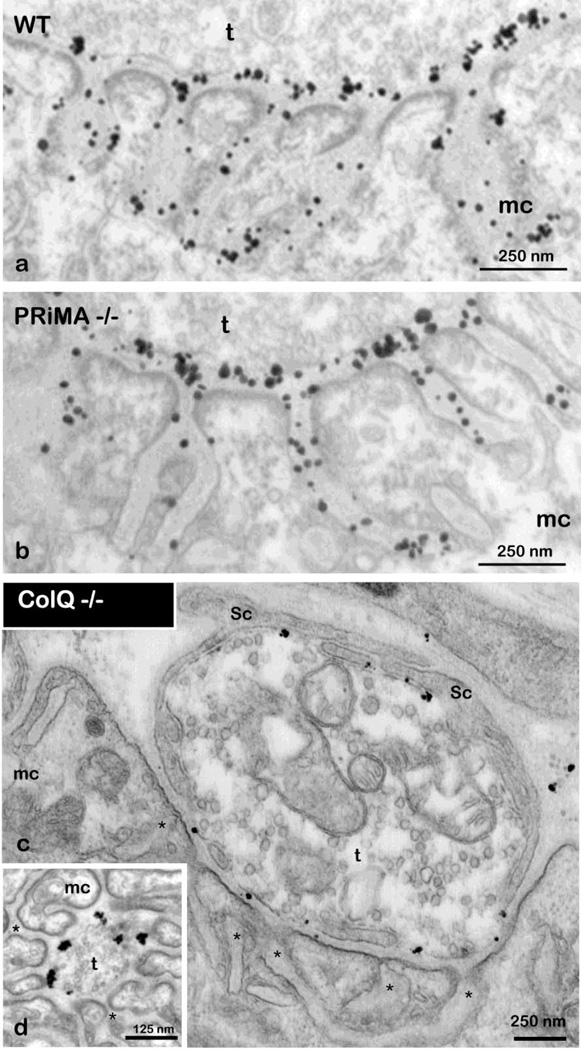

To further explore the respective contributions of ColQ and PRiMA in the localization of AChE along the nerve terminal, we used immunolocalization at the electron microscopic level. In the PRiMA−/− strain, AChE (AChE-ColQ) was detected along the presynaptic membrane and in the postsynaptic folds; the staining was very similar to that found in the WT animal, as shown in figure 5 a and b. In the ColQ−/− strain, AChE (AChE-PRiMA) was detected only along the presynaptic membrane, never along the post-synaptic membrane, neither in the folds nor in the perijunctional domain (figure 5 c, d). Note the very low number of gold particles compared to the number found in the WT and PRiMA−/− strains, revealing the great predominance of the ColQ species of AChE.

Figure 5. Subcellular Detection of AChE at the NMJ in ColQ and PRiMA −/− Knockout Mice by Electron Microscopy.

AChE is detected at the NMJ as in figure 1c. a) WT; b) PRiMA−/− and c,d) ColQ−/− In PRiMA−/− mice, immunogold particles for AChE have a similar localization to that in WT animals. In ColQ−/− animals, immunoparticles for AChE are detected in association with the external surface of the membrane of motoneuron terminals facing the muscle cell. t, nerve terminal and mc, muscle cell.

Cellular origin of AChE-ColQ and AChE-PRiMA at the NMJ

To address the question of the cellular origin of AChE-ColQ accumulated at the NMJ (nerve or muscle) and AChE-PRiMA in junctional and extrajunctional regions, we used a knockout mouse strain, achei1rr−/−, in which a muscle regulatory element, an enhanceosome in the AChE gene, was deleted so that AChE mRNA from cells forming the NMJ is expressed in motor neurons, but not in muscle fibers of the knockout mice (Camp et al., 2008). The achei1rr−/− mice have less than 2% of the total AChE found in muscle homogenates of WT mice. At the NMJs of these knockout mice, AChE was still visible by histochemistry, but its visualization required greatly prolonged incubation times (18h; figure 6a compared to 30 min in WT). The staining was present in round subcellular elements that appeared to lie at the surface of the muscle fiber and were similar to those observed in the ColQ−/− strain (figure 3i). AChE labeling was also seen at the surface of pre-terminal nerve segments (arrows in figure 6a). To determine whether AChE is anchored by ColQ or by PRiMA at the NMJs of the achei1rr−/− knockouts, we generated a double (PRiMA−/−/achei1rr−/−) knockout mouse. As shown in figure 6b, AChE labeling was completely absent in the PRiMA−/−/achei1rr−/−knockout; this result was indistinguishable from what was seen in the AChE−/− null knockout that was used as a control (data not shown), demonstrating that small residual AChE in the AChE1irr mouse is anchored selectively by PRiMA.

Figure 6. Origin of AChE-ColQ and AChE-PRiMA at the NMJ.

a) Histochemical staining is detected at the surface of the muscle fiber after 18 hours. AChE labeling is also seen in pre-terminals (arrow in a). b) No AChE labeling is detected in the double knockout PRiMA−/−/achei1rr−/−, arrows in b point to the nerve. Histochemical staining is detected in the ventral horn of the spinal cord after 1 hour. In the achei1rr−/− knockout strain (c) as in wild type mice (e), AChE labeling is seen at the surface of the neuron. Conversely, in the absence of PRiMA, AChE is restricted to motoneuron cell bodies in the PRiMA−/− knockout (f), and in the double knockout, PRiMA−/−/achei1rr−/− (d).

To verify whether the small amounts of residual AChE at the NMJ in achei1rr−/− strain arise from the motoneuron, we analyzed AChE in the spinal cord. AChE labeling was very similar to that seen in the WT spinal cord, including AChE found at the surface of nerve processes (figure 6c, e). In contrast, when PRiMA was absent, as expected in either in the PRiMA−/− or PRiMA−/−/achei1rr−/− knockout strain, AChE was restricted to the cell bodies of the motoneurons and did not extend to the axon trunk or the dendritic tree (figure 6d, f). Taken together, these results establish that the small, residual quantities of AChE produced by the nerve that migrate to the NMJ are exclusively anchored by PRiMA and not by ColQ, and that the vast majority of muscle AChE is produced by the muscle, not the nerve.

Biochemical analysis of AChE-ColQ and AChE-PRiMA at the NMJ

To further clarify the contributions of ColQ and PRiMA in the assembly of AChE molecular forms in muscle and specifically at the NMJ, we analyzed hydrodynamically the assembled species of AChE in knockout mouse strains devoid of either ColQ or PRiMA. As shown in figure 7a, WT AChE was distributed in 6 peaks of activity when separated in high ionic strength sucrose gradients containing the detergent BRIJ 97. Peaks at 16.1 S (A12) and 12.5 S (A8) correspond to the collagen-tailed forms containing 3 or 2 tetramers of AChE. These forms are soluble at high ionic strength and are assembled only by ColQ, since they were absent in the ColQ−/− knockout. The 9.2 S peak corresponds to amphiphilic AChE tetramers that associate with the BRIJ detergent, producing a characteristic shift in sedimentation coefficient. These tetramers assemble only with PRiMA since they were absent in the PRiMA−/− knockout. A 10.5 S peak, representing a very minor component of AChE, corresponds to non-amphiphilic AChE tetramers that do not interact with detergent. Two peaks around 4.5 S correspond to amphiphilic dimers and non-amphiphilic monomers, and the 2.4 S peak corresponds to amphiphilic monomers.

Figure 7. Nature and Distribution of AChE Molecular Forms in the Mouse Tibialis Anterior Muscle.

a) In wild type muscle extracts (left panel), AChE activity is resolved into six peaks by ultracentrifugation in sucrose gradients (see method). Three grey peaks correspond to heteromeric-oligomers that are pictured over the gradient profile: A12, 3 AChE tetramers and a trimeric ColQ (16.1 S), A8, 2 AChE tetramers and a trimeric ColQ (12.5 S), G4a, 1 AChE tetramer and a PRiMA subunit (9.3 S, amphiphilic tetramer). Three peaks correspond to homomeric-oligomers: tetramer (10.5 S, non- amphiphilic tetramer), amphiphilic dimer G2a (together with non- amphiphilic monomer) (4.5 S) and an amphiphilic monomer G1a (2.4 S). In the ColQ−/− knockout (middle panel) and in the PRiMA−/− knockout (right panel), the muscles were extracted and loaded using the same conditions as for the WT.

b) Sedimentation profiles of extracts from total (left panel, full circles) and aneural muscle segments (right panel, open circles) of WT tibialis anterior muscle. Each sample was extracted with the same volume of buffer per weight of frozen muscle. Samples containing an equal amount of protein were loaded on gradients and AChE activity was measured.

To quantify AChE molecular forms at or around the NMJ, we compared the molecular forms of AChE in extracts from a complete tibialis anterior muscle and from muscle segments where NMJs are absent. Because the AChE-PRiMA content varied from muscle to muscle and animal to animal, but was identical between paired left and right leg muscles, we compared complete right versus the contralateral, dissected left muscle. To allow quantitative comparisons, identical volumes of buffer per tissue weight and quantity of protein were applied to sucrose gradients. As shown in figure 7b, the peak corresponding to the AChE-PRiMA complex (9.2 S) had slightly less AChE activity in aneural muscle extracts than in total muscle extracts, whereas the AChE-ColQ complexes (16.1 S and 12.5 S) were virtually absent in the aneural muscle extracts, indicating that AChE-PRiMA is distributed along the muscle fibers and not appreciably concentrated at or around the NMJ.

Discussion

The localization, cellular origin, and function of the multiple molecular forms of AChE at the NMJ present long standing questions not easily resolved because of the absence of tools available to distinguish between these AChE forms. Recently, we developed complementary genetic, histochemical and biochemical approaches that have enabled us to obtain unique data on the subcellular distribution and function of the two AChE hetero-oligomers, AChE-PRiMA and AChE-ColQ, at the NMJ and in extrajunctional regions.

Unexpected results emerged from these studies: 1) AChE-ColQ found post-synaptically, is exclusively in synaptic folds and is not at localized at synaptic crests. 2) AChE accumulates along the pre-synaptic nerve terminal membrane on the side opposite postsynaptic nicotinic receptors. Clearly AChE and nAChR display distinct and well separated localizations at the synapse. 3) Most of the AChE along the nerve terminal is anchored by ColQ, and only a small fraction is anchored by the neuronal membrane anchor, PRiMA. 4) PRiMA is produced at very low density along the muscle.

At the NMJ, AChE-ColQ is clustered along the presynaptic membrane and in the secondary post-synaptic folds, whereas the small quantity of AChE-PRiMA in the synapse is localized at the nerve terminal

Complex procedures used to obtain and quantify specific labeling have established that AChE is located in both the primary cleft and secondary folds of the NMJ (Rogers et al., 1969; Salpeter, 1969). More recently, labeling with iodinated fasciculin2 confirmed the previous AChE localization and quantification, at similar resolution (Anglister et al., 1998). Histochemical detection of AChE activity was also used to reveal the localization of the enzyme; however, diffusion of the reaction product that was generated did not allow a precise determination of AChE localization in the basal lamina (Couteaux and Taxi, 1952). All of the above authors assumed that AChE is homogeneously distributed along the pre and post-synaptic membranes. However, in a unique and elegant experiment, the formation of the thioreactive precipitate was reduced by competition of acetylthiocholine with ACh and the precipitate was found close to the nerve terminal membrane and in the post synaptic folds, but not close to the nAChR (Schatz and Veh, 1987). In the current study we employed antibodies of improved selectivity, as well as toxins, both at the electron microscopic resolution, to establish that AChE localizes along the presynaptic membrane of the primary cleft and in the folds, but not on the postsynaptic membrane proximal to the nAChRs (Fig. 2c,Fig. 4a,Fig. 7). In order to distinguish the contribution of AChE-PRiMA and AChE-ColQ molecular forms in this labeling, we employed knockout mouse strains in which the two structural subunits, ColQ and PRiMA, had been individually deleted and expression of AChE from muscle nuclei had been repressed. The findings of very low amounts of synaptic AChE in ColQ−/− mice (only AChE-PRiMA was present in Fig. 3 i,j,l) and essentially WT levels of synaptic AChE in the PRiMA−/− knockout (only AChE-ColQ was present in Fig. 3e,f,h, 4b), demonstrated that the AChE at the presynaptic nerve terminal membrane was mainly AChE-ColQ with a very minor contribution of AChE-PRiMA.

Indeed the localization of AChE along the nerve terminal depends upon a trans-synaptic molecule, ColQ, a triple helical, basal lamina collagen that extends 50nm in length. At its C-terminal domain ColQ may bind MusK at the post-synaptic membrane (Cartaud et al., 2004) and in the collagen domain ColQ interacts with heparin sulfate proteoglycan through two different heparin binding sites (Deprez et al., 2003). At its N-terminal domain, the PRAD domain organizes AChE into a tetramer (Bon et al., 1997) and consequently each trimer of collagen can cluster 12 catalytic subunits. This unexpected organization concentrates and stabilizes AChE along the nerve terminal membrane, where AChE-ColQ density should not be influenced directly by vesicle fusion and membrane dynamics of the presynaptic nerve terminal.

At the NMJ AChE-ColQ is only produced by the muscle cell, AChE-PRiMA is produced by the nerve terminal and in far smaller quantities. In extrajunctional regions, although overall surface densities are very low, substantial amounts of AChE-PRiMA are found

The presence of both isoforms of AChE at presynaptic membranes raises the question of their respective cellular origins. Is AChE-ColQ produced by the nerve as are other extracellular matrix proteins such as agrin? This question has been addressed both in vitro and in vivo. In cell culture, it was proposed that asymmetric AChE forms were only produced by the muscle when chicken muscle was cocultured with rat motoneurons (Vallette et al., 1990). A mixed origin of AChE was proposed when explants of spinal cord were associated with human muscle cells (Jevsek et al., 2004). These authors did not characterize the oligomers accumulated at the nerve-muscle contact. In vivo, when the nerve regenerates within the ghost of the basal lamina in the absence of muscle, AChE was observed at the muscle-nerve contact, but the nature of AChE isoform was not identified (Anglister, 1991). Alternatively, several experiments in vivo, in rabbit, suggest that AChE-ColQ is transported by both axonal and retrograde flow (Di Giamberardino and Couraud, 1978; Fernandez et al., 1980). These studies did not demonstrate that the AChE-ColQ complex accumulates at the NMJ. In contrast, we establish here that in mouse muscles, AChE-ColQ, accumulating at the NMJ, is not synthesized and transported by the motoneuron, but is produced only by the muscle cell. First, we showed that NMJ AChE labeling is virtually absent in the AChei1rr knockout strain, a strain lacking the enhanceosome in the AChE gene necessary for AChE expression in muscle cells (Camp et al., 2008). Second, in the PRiMA−/− strain, AChE is retained in the cell body of the motoneuron and does not migrate down the axon, a finding that has also been demonstrated in neurons in the striatum (Dobbertin et al., 2009).

That PRiMA mRNA and protein are expressed both in the spinal cord (motoneuron) and in muscle might indicate that AChE-PRiMA contributes quantitatively to AChE expression at the NMJ (Tsim et al., 2010), however, we have shown in several ways that AChE-PRiMA localization at the NMJ is minimal. Having established the very small amounts of AChE-PRiMA found in the neuromuscular junction, one must still account for the large amount of AChE-PRiMA that is found in muscle. Since the amounts of the AChE-PRiMA species are similar in innervated and aneural areas of muscle, this form of AChE arises from low level expression across the muscle surface. Since AChE-PRiMA is absent in AChE1irr, the complex must arise from expression of AChE and PRiMA subunits from nuclei of the muscle fibers controlling extrajunctional expression of AChE. Indeed AChE-PRiMA in muscle fibers was mainly located at extrasynaptic sites, probably at the cell surface as previously proposed for the tetramer (Younkin et al., 1982) and corresponds to the enzyme isoform that varies in amount between muscle subtypes which can be regulated by muscle exercise (Boudreau-Larivière et al., 1997; Gisiger et al., 1994; Lomo et al., 1985).

Having established the low contribution of AChE-PRiMA at the NMJ, it remains to be determined the respective contribution of AChE-PRiMA at the pre and post synaptic membranes; this is a complex issue because the quantity of AChE-PRiMA is very low at the NMJ, but high and variable in the extrajunctional domain. In the ColQ knockout, we visualized AChE only on the nerve terminal and never in the post or peri-synaptic area. It is possible that AChE antibodies did not penetrate into the folds as suggested by the difference of labeling between toxin (figure 2b) and antibody (figure 1c), but this should not be the case in the perijunctional area. Alternatively AChE-PRiMA should be increased at the nerve terminal of ColQ mutant as a compensatory mechanism. On the other hand, time lapse imaging and recovery after photo-bleaching have shown that extrajunctional AChE migrates to the junctional area, mainly the perisynaptic space (Martinez-Pena y Valenzuela and Akaaboune, 2007). This suggests that AChE-PRiMA may contribute to the postsynaptic AChE. In accordance with ours results, the contribution of this enzyme is low (5%). Finally, the quantity and distribution of AChE-PRiMA at the NMJ should be different between muscles but it does not seem to simply correlate with the abundance of AChE-PRiMA in the total muscle.

AChE which is located along the nerve terminals is strategically positioned to scavenge ACh that effluxes from the nerve by non-quantal release (NQR)

Inhibition of AChE has previously shown that ACh is released not only by the fusion of vesicles to the presynaptic membrane (quantal release) but also by a non-quantal pathway in frog (Katz and Miledi, 1977) and in mammals (Vyskocil and Illés, 1977). The function of this non quantal release (NQR) is not clear, but the quantity of ACh that effluxes from the nerve by NQR appears to be quantitatively important. The molecular basis of the NQR depends upon the vesicular ACh transporter (vAChT) (Zemkova et al., 1990) and possibly upon the high affinity choline transporter (ChT), because the NQR is reduced by the local application of vesamicol (an inhibitor of vAChT) or hemicholinium (an inhibitor of ChT) (Vyskocil et al., 2009). In the synaptic vesicle membranes, vAChT loads the vesicle with ACh against a proton gradient. Recently it was found that ChT is found mainly on the vesicle membrane (Ferguson et al., 2003). After fusion of the vesicles to the plasma membrane, ChT takes up choline. Concurrently vAChT is targeted to the plasma membrane where it is positioned to drive reverse transport from the cytoplasm to the synaptic cleft, alone or in association with ChT. It is probable that this reverse transport is an intrinsic property of the transporter and is a residual consequence of this compulsory membrane fusion step of synaptic transmission.

The presence of AChE at the nerve terminal appears to be the simplest way to scavenge non-quantal release of ACh. In this study we show that at the NMJ, AChE along the nerve terminal is anchored by ColQ produced by the muscle, but resides close to the pre-synaptic terminal. We have previously shown that AChE in the striatum is mainly anchored by PRiMA along the axon of the cholinergic neurons (Dobbertin et al., 2009). Indeed, along the presynaptic cholinergic boutons AChE should destroy a continuous leakage or efflux of ACh, and uptake by high affinity ChT of the choline product of AChE catalyzed hydrolysis should facilitate the rapid and quantitative recycling of ACh. Taken together, the present studies provide additional evidence supporting a previously unappreciated function of AChE, the control of non-quantal release or leakage of ACh at the nerve terminal and consequent reinforcement of the temporal control or precision of quantal ACh release.

Because of its accessibility and discrete anatomy, the neuromuscular junction has been extensively studied as a model synapse from both physiological and pharmacological perspectives. Contemporary genetic approaches coupled with immunohistochemical analyses at the electron microscopy level enable one to deconstruct this complex system by expressing only certain forms of AChE and controlling AChE expression of both nerve and muscle origins. Future studies will explore how AChE disposition affects postsynaptic excitation and muscle contraction.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr P. Guicheney, A. Rouche and P. Bozin (INSERM U582, Institut de myologie, Paris, France) for electron microscopy facilities. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (P42-ES010337) and (R37-GM18360-35) to P.T. and by grants from Inserm, Association Française contre les Myopathies (AFM), Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR Neuroscience), Bonus Qualité Recherche Université Paris Descartes to EK. EK is supported by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), AH by AFM and ANR and EG by ANR maladies rares. We thank Dr Philippe Ascher for critical reading and helpful discussions.

Acronyms

- α-BTX

α-bungarotoxin

- ACh

Acetylcholine

- AChE

acetylcholinesterase

- AChE1irr

mouse strain lacking AChE expression in muscle

- BChE

butyrylcholinesterase

- ChT

high affinity choline transporter

- ColQ

collagen Q

- nAChR

nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- NDS

normal donkey serum

- NMJ

neuromuscular junction

- NQR

non-quantal release

- PRiMA

proline-rich membrane anchor

- VAChT

vesicular acetylcholine transporter

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anglister L. Acetylcholinesterase from the motor nerve terminal accumulates on the synaptic basal lamina of the myofiber. J. Cell Biol. 1991;115:755–764. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.3.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglister L, Eichler J, Szabo M, Haesaert B, Salpeter MM. 125I-labeled fasciculin 2: a new tool for quantitation of acetylcholinesterase densities at synaptic sites by EM-autoradiography. J. Neurosci. Methods. 1998;81:63–71. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(98)00015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard V, Levey AI, Bloch B. Regulation of the subcellular distribution of m4 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in striatal neurons in vivo by the cholinergic environment: evidence for regulation of cell surface receptors by endogenous and exogenous stimulation. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:10237–10249. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-23-10237.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bon S, Coussen F, Massoulié J. Quaternary associations of acetylcholinesterase. II. The polyproline attachment domain of the collagen tail. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:3016–3021. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.5.3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau-Larivière C, Gisiger V, Michel RN, Hubatsch DA, Jasmin BJ. Fast and slow skeletal muscles express a common basic profile of acetylcholinesterase molecular forms. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;272:C68–C76. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.1.C68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camp S, De Jaco A, Zhang L, Marquez M, De la Torre B, Taylor P. Acetylcholinesterase expression in muscle is specifically controlled by a promoter-selective enhanceosome in the first intron. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:2459–2470. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4600-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartaud A, Strochlic L, Guerra M, Blanchard Bt, Lambergeon M, Krejci E, Cartaud J, Legay C. MuSK is required for anchoring acetylcholinesterase at the neuromuscular junction. J. Cell Biol. 2004;165:505–515. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couteaux R, Taxi J. Recherches histochimiques sur la distribution des activités cholinestérasiques au niveau de la synapse myoneurale. Archives d'anatomie microscopique et de morphologie expérimentale. 1952;352 [Google Scholar]

- Deprez P, Inestrosa NC, Krejci E. Two different heparin-binding domains in the triple-helical domain of ColQ, the collagen tail subunit of synaptic acetylcholinesterase. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:23233–23242. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301384200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giamberardino L, Couraud JY. Rapid accumulation of high molecular weight acetylcholinesterase in transected sciatic nerve. Nature. 1978;271:170–172. doi: 10.1038/271170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbertin A, Hrabovska A, Dembele K, Camp S, Taylor P, Krejci E, Bernard Vr. Targeting of acetylcholinesterase in neurons in vivo: a dual processing function for the proline-rich membrane anchor subunit and the attachment domain on the catalytic subunit. J. Neurosci. 2009:4519–4530. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3863-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donger C, Krejci E, Serradell AP, Eymard B, Bon S, Nicole S, Chateau D, Gary F, Fardeau M, Massoulié J, Guicheney P. Mutation in the human acetylcholinesterase-associated collagen gene, COLQ, is responsible for congenital myasthenic syndrome with end-plate acetylcholinesterase deficiency (Type Ic) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1998;63:967–975. doi: 10.1086/302059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvir H, Harel M, Bon S, Liu W-Q, Vidal M, Garbay C, Sussman JL, Massoulié J, Silman I. The synaptic acetylcholinesterase tetramer assembles around a polyproline II helix. EMBO J. 2004;23:4394–4405. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng G, Krejci E, Molgo J, Cunningham JM, Massoulié J, Sanes JR. Genetic analysis of collagen Q: roles in acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase assembly and in synaptic structure and function. J. Cell Biol. 1999;144:1349–1360. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.6.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SM, Savchenko V, Apparsundaram S, Zwick M, Wright J, Heilman CJ, Yi H, Levey AI, Blakely RD. Vesicular localization and activity-dependent trafficking of presynaptic choline transporters. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:9697–9709. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-30-09697.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez HL, Duell MJ, Festoff BW. Bidirectional axonal transport of 16S acetylcholinesterase in rat sciatic nerve. J. Neurobiol. 1980;11:31–39. doi: 10.1002/neu.480110105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferry CB, Kelly SS. The nature of the presynaptic effects of d-tubocurarine at the mouse neuromuscular junction. The Journal of Physiology. 1988;403:425–437. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisiger V, Bélisle M, Gardiner PF. Acetylcholinesterase adaptation to voluntary wheel running is proportional to the volume of activity in fast, but not slow, rat hindlimb muscles. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1994;6:673–680. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisiger V, Stephens HR. Localization of the pool of G4 acetylcholinesterase characterizing fast muscles and its alteration in murine muscular dystrophy. Journal of neuroscience research. 1988;19:62–78. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490190110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasmin BJ, Gisiger V. Regulation by exercise of the pool of G4 acetylcholinesterase characterizing fast muscles: opposite effect of running training in antagonist muscles. Journal of Neuroscience. 1990;10:1444. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-05-01444.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings LL, Malecki M, Komives EA, Taylor P. Direct analysis of the kinetic profiles of organophosphate-acetylcholinesterase adducts by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Biochemistry. 2003;42:11083–11091. doi: 10.1021/bi034756x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jevsek M, Mars T, Mis K, Grubic Z. Origin of acetylcholinesterase in the neuromuscular junction formed in the in vitro innervated human muscle. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004;20:2865–2871. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasprzak H, Salpeter MM. Recovery of acetylcholinesterase at intact neuromuscular junctions after in vivo inactivation with di-isopropylfluorophosphate. J. Neurosci. 1985;5:951–955. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-04-00951.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B, Miledi R. The binding of acetylcholine to receptors and its removal from the synaptic cleft. The Journal of Physiology. 1973;231:549–574. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B, Miledi R. Transmitter leakage from motor nerve endings. Proc. R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci. 1977;196:59–72. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1977.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krejci E, Martinez-Pena y Valenzuela I, Ameziane R, Akaaboune M. Acetylcholinesterase dynamics at the neuromuscular junction of live animals. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:10347–10354. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507502200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krejci E, Thomine S, Boschetti N, Legay C, Sketelj J, Massoulié J. The mammalian gene of acetylcholinesterase-associated collagen. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:22840–22847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung KW, Xie HQ, Chen VP, Mok MKW, Chu GKY, Choi RCY, Tsim KWK. Restricted localization of proline-rich membrane anchor (PRiMA) of globular form acetylcholinesterase at the neuromuscular junctions--contribution and expression from motor neurons. FEBS J. 2009;276:3031–3042. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomo T, Massoulié J, Vigny M. Stimulation of denervated rat soleus muscle with fast and slow activity patterns induces different expression of acetylcholinesterase molecular forms. J. Neurosci. 1985;5:1180–1187. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-05-01180.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magleby KL, Terrar DA. Factors affecting the time course of decay of end-plate currents: a possible cooperative action of acetylcholine on receptors at the frog neuromuscular junction. The Journal of Physiology. 1975;244:467–495. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp010808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh D, Grassi J, Vigny M, Massoulié J. An immunological study of rat acetylcholinesterase: comparison with acetylcholinesterases from other vertebrates. J. Neurochem. 1984;43:204–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1984.tb06698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Pena y Valenzuela I, Akaaboune M. Acetylcholinesterase mobility and stability at the neuromuscular junction of living mice. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:2904–2911. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-02-0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massoulié J, Millard CB. Cholinesterases and the basal lamina at vertebrate neuromuscular junctions. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2009;9:316–325. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahan UJ, Sanes JR, Marshall LM. Cholinesterase is associated with the basal lamina at the neuromuscular junction. Nature. 1978;271:172–174. doi: 10.1038/271172a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno K, Brengman J, Tsujino A, Engel AG. Human endplate acetylcholinesterase deficiency caused by mutations in the collagen-like tail subunit (ColQ) of the asymmetric enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:9654–9659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrier AL, Massoulié J, Krejci E. PRiMA: the membrane anchor of acetylcholinesterase in the brain. Neuron. 2002;33:275–285. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00584-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers AW, Darzynkiewicz Z, Salpeter MM, Ostrowski K, Barnard EA. Quantitative studies on enzymes in structures in striated muscles by labeled inhibitor methods. I. The number of acetylcholinesterase molecules and of other DFP-reactive sites at motor endplates, measured by radioautography. J. Cell Biol. 1969;41:665–685. doi: 10.1083/jcb.41.3.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salpeter MM. Electron microscope radioautography as a quantitative tool in enzyme cytochemistry. II. The distribution of DFP-reactive sties at motor endplates of a vertebrate twitch muscle. J. Cell Biol. 1969;42:122–134. doi: 10.1083/jcb.42.1.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatz CR, Veh RW. High-resolution localization of acetylcholinesterase at the rat neuromuscular junction. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1987;35:1299–1307. doi: 10.1177/35.11.3655326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tago H, Kimura H, Maeda T. Visualization of detailed acetylcholinesterase fiber and neuron staining in rat brain by a sensitive histochemical procedure. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1986;34:1431–1438. doi: 10.1177/34.11.2430009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsim K, Leung K, Mok K, Chen V, Zhu K, Zhu J, Guo A, Bi C, Zheng K, Lau D, Xie H, Choi R. Expression and localization of PRiMA-Linked globular form acetylcholinesterase in vertebrate neuromuscular junctions. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience. 2010;40:40–46. doi: 10.1007/s12031-009-9251-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallette FM, De la Porte S, Koenig J, Massoulié J, Vigny M. Acetylcholinesterase in cocultures of rat myotubes and spinal cord neurons: effects of collagenase and cis-hydroxyproline on molecular forms, intra- and extracellular distribution, and formation of patches at neuromuscular contacts. J. Neurochem. 1990;54:915–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb02338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyskocil F, Illés P. Non-quantal release of transmitter at mouse neuromuscular junction and its dependence on the activity of Na+-K+ ATP-ase. Pflugers Arch. 1977;370:295–297. doi: 10.1007/BF00585542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyskocil F, Malomouzh AI, Nikolsky EE. Non-quantal acetylcholine release at the neuromuscular junction. Physiol Res. 2009;58:763–784. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.931865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W, Stribley JA, Chatonnet A, Wilder PJ, Rizzino A, McComb RD, Taylor P, Hinrichs SH, Lockridge O. Postnatal developmental delay and supersensitivity to organophosphate in gene-targeted mice lacking acetylcholinesterase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293:896–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie HQ, Leung KW, Chen VP, Lau FTC, Liu LS, Choi RCY, Tsim KWK. The promoter activity of proline-rich membrane anchor (PRiMA) of globular form acetylcholinesterase in muscle: suppressive roles of myogenesis and innervating nerve. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2008;175:79–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younkin SG, Rosenstein C, Collins PL, Rosenberry TL. Cellular localization of the molecular forms of acetylcholinesterase in rat diaphragm. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:13630–13637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemkova H, Vyskocil F, Edwards C. The effects of nerve terminal activity on non-quantal release of acetylcholine at the mouse neuromuscular junction. The Journal of Physiology. 1990;423:631–640. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]