Abstract

Neuropeptide Y (NPY) is a sympathetic neurotransmitter with pleiotropic actions, many of which are highly relevant to tumor biology. Consequently, the peptide has been implicated as a factor regulating the growth of a variety of tumors. Among them, two pediatric malignancies with high endogenous NPY synthesis and release – neuroblastoma and Ewing sarcoma – became excellent models to investigate the role of NPY in tumor growth and progression. The stimulatory effect on tumor cell proliferation, survival and migration, as well as angiogenesis in these tumors is mediated by two NPY receptors, Y2R and Y5R, which are expressed in either a constitutive or inducible manner. Of particular importance are interactions of the NPY system with the tumor microenvironment, as hypoxic conditions commonly occurring in solid tumors strongly activate the NPY/Y2R/Y5R axis. This activation is triggered by hypoxia-induced up-regulation of Y2R/Y5R expression and stimulation of dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPPIV), which converts NPY to a selective Y2R/Y5R agonist, NPY3-36. While previous studies focused mainly on the effects of NPY on tumor growth and vascularization, they also provided insight into the potential role of the peptide in tumor progression into a metastatic and chemoresistant phenotype. This review summarizes our current knowledge of the role of NPY in neuroblastoma and Ewing sarcoma and its interactions with the tumor microenvironment in the context of findings in other malignancies, as well as discusses future directions and potential clinical implications of these discoveries.

Keywords: neuropeptide Y (NPY), neuroblastoma, Ewing sarcoma, tumor biology

Neuropeptide Y (NPY) as a pleiotropic factor with functions relevant to tumor biology

NPY is a 36 amino-acid sympathetic neurotransmitter abundant in the brain and released from peripheral sympathetic neurons during their activation, e.g. by chronic stress or hypoxia (Zukowska-Grojec, 1995). Acting via its Y1-Y5 receptors (Y1R – Y5R), the peptide exerts pleiotropic effects that control various functions of the organism. Importantly, many of these actions of NPY, including stimulation of cell proliferation, migration and survival, as well as regulation of cell differentiation, are highly relevant to tumor growth and progression (Han et al., 2012; Hansel et al., 2001; Kitlinska et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2010; Pons et al., 2003; Son et al., 2011). Consequently, recent years brought significant progress in our understanding of the peptide’s role in regulation of tumor growth, as well as some evidence for its contribution to cancer progression toward a metastatic and chemoresistant phenotype.

NPY has been implicated as a growth-promoting factor in various malignancies, including breast and prostate cancer (Lenkinski et al., 2008; Magni and Motta, 2001; Medeiros et al., 2011; Medeiros and Jackson, 2013; Ruscica et al., 2007; Sheriff et al., 2010; Ueda et al., 2013). Among them, two pediatric tumors with high endogenous NPY expression – neuroblastoma and Ewing sarcoma - have proven to be excellent tools to investigate the role of the peptide in tumor biology (Hong et al., 2015; Kitlinska et al., 2005; Lu et al., 2010; Lu et al., 2011; Tilan et al., 2014b; Tilan et al., 2013b). Our studies revealed that despite their different origins and means of NPY system regulation, these two tumor types share common functional responses to the peptide. These similarities implicate the universal nature of NPY actions and suggest that our findings can be relevant to other malignancies that do not express NPY, yet are exposed to the peptide released systemically from sympathetic neurons (Tilan and Kitlinska, 2010). Such an understanding of NPY’s role in tumor biology is particularly important in relation to pathologies associated with elevated systemic levels of the peptide, e.g. severe chronic stress. In this review, we will describe the pleiotropic actions of NPY that we have identified in neuroblastoma and Ewing sarcoma and its interactions with the tumor microenvironment. We will present our results in the context of previously reported data gathered in other tumor types, as well as discuss the potential implications of these findings. As work on the role of NPY in tumor biology is ongoing, we will also identify gaps in the current knowledge and potential future directions in research.

Neuroblastoma and Ewing sarcoma as models of NPY-rich tumors

Neuroblastoma is a pediatric malignancy developing very early in life, often in infancy (Maris, 2010). The disease is extremely heterogeneous, with phenotypes ranging from spontaneously regressing, to highly aggressive and metastatic tumors. While the low-grade tumors are curable, treatment of metastatic neuroblastoma remains a clinical challenge, with event-free survival for patients with high-risk disease remaining below 50% (Cohn et al., 2009). Neuroblastomas develop from precursors of sympathetic neurons, most often in adrenal glands or peripheral sympathetic ganglia, and metastasize mainly to the bone marrow and bones (Maris et al., 2010). A very specific type of neuroblastoma, stage 4S, develops in infancy and presents at diagnosis with metastases to skin, bone marrow and liver, yet commonly regresses or matures with time without treatment (Cohn et al., 2009).

Due to their sympathetic origin neuroblastomas express neuronal markers, including NPY and its receptors (Kitlinska et al., 2005; Maris, 2010). We have shown that NPY and its Y2R are universally expressed in neuroblastoma cells and tissues, while Y5R is an inducible receptor, e.g. under hypoxic conditions (Tab. 1) (Czarnecka et al., 2015; Kitlinska et al., 2005; Lu et al., 2010). Further studies revealed a crucial role for both pathways in different aspects of neuroblastoma biology.

Table 1.

NPY system expression and functions in various tumor types and cells from tumor microenvironment

| Cell type | Factors expressed in vitro

|

Factors expressed in vivo | Identified functions

|

References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constitutively expressed | Inducible | Inducing factors | Pathway | Function | |||

|

| |||||||

|

Pediatric malignancies – tumor cells and cells from their microenvironment

| |||||||

| Neuroblastoma | NPY, Y2R | Y5R | Pro-apoptotic conditions: hypoxia, serum withdrawal, chemotherapy, lack of attachment; BDNF | NPY, Y2R, Y5R | NPY/Y2R NPY/Y5R BDNF/Y5R transactivation |

Proliferation Survival Survival |

(Kitlinska et al., 2005; Lu et al., 2010) (Czarnecka et al., 2015) (Czarnecka et al., 2015) |

|

| |||||||

| Ewing sarcoma | NPY, Y1R, Y5R | Y2R, DPPIV | Hypoxia | NPY, Y1R, Y2R, Y5R, DPPIV | NPY/Y1R/Y5R NPY/Y2R/Y5R |

Cell death Proliferation and migration of cancer stem cells |

(Kitlinska et al., 2005; Lu et al., 2011) (Tilan et al., 2013b) |

|

| |||||||

| Endothelial cells | NPY, Y1R | Y2R, Y5R | Hypoxia, NPY | Y2R, Y5R | NPY/Y2R/Y5R | Proliferation, migration | (Kitlinska et al., 2005; Lu et al., 2010; Movafagh et al., 2006; Tilan et al., 2013b) |

|

| |||||||

| Osteoblasts | Y1R | NPY/Y1R | Inhibition of differentiation | (Lee et al., 2010) | |||

|

| |||||||

|

Other tumor types

| |||||||

| Breast cancer | Y1R, Y5R | Y1R, Y5R | NPY/Y1R | Inhibition of estrogen-induced proliferation | (Amlal et al., 2006) | ||

| NPY/Y5R | Proliferation, migration, VEGF release | (Medeiros et al., 2011; Medeiros and Jackson, 2013; Sheriff et al., 2010) | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Prostate cancer | Y1R | NPY, Y1R | NPY/Y1R NPY |

Regulation of proliferation Biomarker of malignant phenotype |

(Ruscica et al., 2007) (Rasiah et al., 2006; Ueda et al., 2013) |

||

|

| |||||||

| Melanoma | NPY | NPY | Association with invasive phenotype | (Gilaberte et al., 2012) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Cholangio-carcinoma | NPY, Y2R | NPY/Y2R | Inhibition of cell proliferation and invasiveness | (DeMorrow et al., 2011) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Colorectal Cancer | NPY | NPY | Inhibition of invasiveness | (Ogasawara et al., 1997) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Pheochromo-cytoma | NPY, Y1R, Y2R, Y5R | NPY | Systemic NPY | Biomarker of malignant phenotype | (de et al., 1995; Grouzmann et al., 1990) | ||

Ewing sarcoma is an aggressive malignancy developing in bones or soft tissues of children and adolescents (Lessnick and Ladanyi, 2012). These tumors frequently relapse after initial treatment and metastasize to the lungs and distant bones. While the outcome of patients with localized disease has recently improved, the prognosis remains dismal for those with metastases at diagnosis, particularly when dissemination to bone is present (8–14% event-free survival) (Ladenstein et al., 2010; Parasuraman et al., 1999; Womer et al., 2012). The Ewing sarcoma cell of origin is controversial, as the data point to neural crest, mesenchymal or even endothelial cells at early stages of their differentiation (Coles et al., 2008; Monument et al., 2013; Staege et al., 2004; Todorova, 2014; von Levetzow et al., 2011). Nevertheless, these tumors exhibit some neuronal properties, including expression of specific markers. Importantly, despite differences in tumor localization and degree of neuronal differentiation, the common feature of Ewing sarcoma tumors is the presence of a characteristic chromosomal translocation leading to the fusion of the Ewing sarcoma breakpoint region1 (EWSR1) gene with an E26 transformation-specific (ETS) transcription factor (EWS-ETS), most often Friend leukemia integration 1 transcription factor (FLI1) (Toomey et al., 2010). This aberrant transcriptional activity of EWS-FLI1 fusion protein is believed to trigger a malignant transformation of Ewing sarcoma, but also induce a neuronal phenotype of Ewing sarcoma. Indeed, NPY and its Y1R and Y5R are transcriptional targets of EWS-FLI1 (Hancock and Lessnick, 2008; Smith et al., 2006). Consequently, an NPY/Y1R/Y5R autocrine loop is highly and constitutively expressed in Ewing sarcoma (Kitlinska et al., 2005; Korner et al., 2008; Lu et al., 2011; van Valen et al., 1992). However, we have also discovered that this pattern of NPY system expression and thereby its functions change dramatically in the hypoxic tumor environment, switching its activity to the NPY/Y2R/Y5R pathway (Tab. 1) (Lu et al., 2011; Tilan et al., 2013b).

In summary, even though basal expression of the NPY system measured in neuroblastoma and Ewing sarcoma cells cultured in vitro is utterly different, the same NPY/Y2R/Y5R axis is active in vivo in the hypoxic tumor microenvironment of both types of tumors. During the course of our studies, we have gathered compelling evidence that this pathway serves as a growth-promoting and potentially pro-metastatic mechanism that is common for both malignancies, and perhaps also other tumors.

Systemic NPY as a marker of adverse tumor phenotype

Due to high NPY synthesis within tumor tissues, both neuroblastoma and Ewing sarcoma tend to release the peptide into the systemic circulation, which results in its elevated levels in the blood (Cohen et al., 1990; Dotsch et al., 1998; Kitlinska et al., 2005; Kogner et al., 1994; Lu et al., 2010; Tilan et al., 2014b). Interestingly, however, despite constitutive and universal expression of NPY in both tumor types, its release varies between patients. Thus, in some cases serum NPY concentrations are highly elevated, while in others NPY levels are comparable to the healthy control (Tilan et al., 2014b). Importantly, elevated systemic NPY levels correlate with adverse tumor phenotype in both malignancies. In neuroblastoma, high plasma NPY is observed in children with advanced disease and associates with poor clinical outcome (Cohen et al., 1990; Dotsch et al., 1998; Kogner et al., 1994). A similar trend of increased serum NPY was observed in patients with metastatic Ewing sarcoma, as compared to those with localized disease and to healthy control (Tilan et al., 2014b). Such variability in peptide release independent of its levels of synthesis suggests secretion of the peptide as a potential mechanism regulating its functions that are mediated by surface receptors. In this way, the ability of tumor cells to release NPY may affect tumor phenotype.

In line with our findings in pediatric malignancies, other groups have reported associations of elevated plasma NPY with metastasis in pheochromocytoma, an adulthood tumor that develops from sympathoadrenal system (Tab. 1) (de et al., 1995; Grouzmann et al., 1990). Furthermore, in prostate cancer patients, proteomics analysis of sera identified NPY as a marker of malignant disease (Ueda et al., 2013). In agreement with this, an increase in NPY expression in tissues was found to be an early event in prostate cancer development (Rasiah et al., 2006). Altogether, these findings implicated NPY as a factor that promotes tumor progression and warranted investigations into its functions and potential mechanisms of actions, as summarized below. Moreover, the ability to detect NPY in the serum of patients with advanced tumors suggests its potential clinical utility as a prognostic factor, as well as a biomarker for minimally invasive, longitudinal disease monitoring.

NPY in regulation of tumor cell proliferation

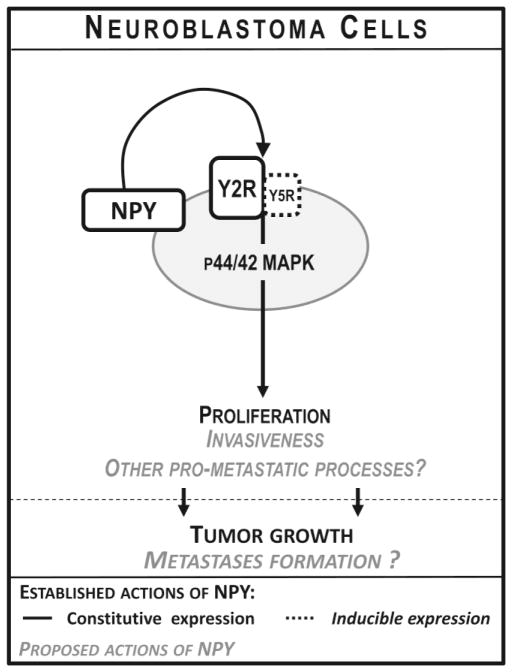

Associations of high systemic NPY with adverse disease phenotype observed in various malignancies raised a question as to its potential role in tumor growth and progression. Indeed, we have found that in neuroblastoma a constitutively expressed NPY/Y2R autocrine loop, acting via p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), is essential for maintaining basal levels of tumor cell proliferation (Fig. 1) (Kitlinska et al., 2005; Lu et al., 2010). Consequently, blocking this pathway led to a decrease in neuroblastoma cell proliferation, both in vitro and in vivo, and an inhibition of tumor growth in a mouse xenograft model (Lu et al., 2010). Moreover, treatment with Y2R antagonist resulted in an induction of apoptosis mediated by BCL-2-interacting mediator of cell death (Bim), the pathway known to be activated in response to growth factor withdrawal (Lu et al., 2010). The proliferative effect of the constitutively active NPY/Y2R axis was further enhanced in the presence of Y5R, which was expressed in some neuroblastoma cell lines in an inducible manner (Czarnecka et al., 2015; Kitlinska et al., 2005). This phenomenon is in line with known interactions between NPY receptors that have been shown to enhance cell sensitivity to the peptide and augment its effects (Gehlert et al., 2007; Movafagh et al., 2006; Pons et al., 2008).

Figure 1. Actions of NPY in neuroblastoma.

Neuroblastoma cells constitutively express NPY and its Y2R. Activity of this autocrine NPY/Y2R loop is essential for maintaining neuroblastoma cell proliferation mediated by the p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. The mitogenic effect of NPY is further enhanced by inducible Y5R. NPY also stimulates neuroblastoma cell invasiveness, and, based on clinical data, may be involved in tumor metastasis.

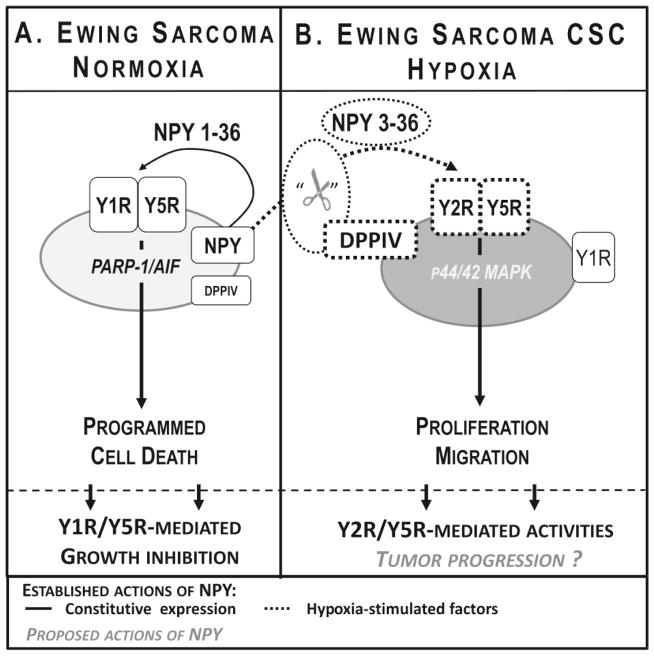

Under basal cell culture conditions, Ewing sarcoma cells seem to be entirely different than neuroblastoma cells in terms of NPY system expression and response to the peptide. Due to the transcriptional activity of EWS-FLI1, Ewing sarcoma cells constitutively express high levels of NPY and its Y1R and Y5R, while Y2R is not detectable in vitro, under basal culture conditions (Tab 1) (Kitlinska et al., 2005; Lu et al., 2011). Paradoxically, our initial studies indicated that simultaneous activation of Y1R and Y5R triggers Ewing sarcoma cell death (Fig. 2A) (Kitlinska et al., 2005). However, we have also discovered that NPY functions dramatically change in the hypoxic tumor environment (Lu et al., 2011; Tilan et al., 2013b). Hypoxia induces expression of Y2R and further up-regulates NPY and Y5R, while Y1R expression remains unchanged (Tab 1) (Tilan et al., 2013b). Simultaneously, hypoxic conditions stimulate expression of dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPPIV) – a protease that cleaves full length NPY1-36 to its shorter form, NPY3-36. This truncated form of NPY no longer activates Y1R, but remains active at other NPY receptors, thereby becoming a selective Y2R/Y5R agonist (Mentlein et al., 1993). These coordinated changes in NPY system expression occurring in the hypoxic environment lead to activation of the NPY3-36/Y2R/Y5R axis, which results in an increased proliferation of hypoxic tumor cells (Fig. 2B) (Tilan et al., 2013b). Remarkably, this hypoxia-induced proliferative effect was observed primarily in Ewing sarcoma cells with high aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) activity (ALDHhigh cells), which are known to have cancer stem cell properties (Awad et al., 2010; Tilan et al., 2013b). These cancer stem cells are believed to be responsible for tumor initiation, as well as subsequent relapse and metastases. Since hypoxia has been shown to promote an aggressive phenotype of various tumors, including Ewing sarcoma, these data indicate that the proliferative effect of NPY in hypoxic cancer stem cells may lead to their propagation and facilitate further tumor progression (Aryee et al., 2010; Batra et al., 2004; Dunst et al., 2001; Kilic et al., 2007; Knowles et al., 2010; Magwere and Burchill, 2011; Tilan et al., 2013b). This hypothesis is currently under investigation in our laboratory.

Figure 2. Hypoxia as a regulator of NPY actions in Ewing sarcoma.

A. Under normoxic conditions Ewing sarcoma cells constitutively express NPY and its Y1R and Y5R. Paradoxically, this autocrine loop is able to stimulate non-apoptotic programmed cell death mediated by the poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1/apoptosis inducing factor (PARP-1/AIF) pathway.

B. Functions of NPY in Ewing sarcoma reverse under hypoxic conditions. Hypoxia further up-regulates expression of NPY and Y5R, induces expression of Y2R and stimulates activity of dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPPIV), the enzyme converting NPY to a selective Y2R/Y5R agonist, NPY3-36. These hypoxia-induced changes lead to over-activation of the NPY/Y2R/Y5R pathway, resulting in proliferation and migration of Ewing sarcoma cells. Notably, these changes are the most apparent in Ewing sarcoma cancer stem cells (CSCs), known to be responsible to the tumor progression to a chemoresistant and metastatic phenotypes, implicating a role for the peptide in these processes.

Altogether, our studies implicate NPY/Y2R/Y5R as a proliferative pathway that could be either constitutively active, or induced by the tumor microenvironment. Among such environmental factors, hypoxia seems to be one of the major regulators of NPY actions, serving as a molecular switch in Ewing sarcoma cells (Tilan et al., 2013b). We have also observed a hypoxia-induced increase in Y5R expression in neuroblastoma cells (unpublished data), where this receptor serves as an enhancer of Y2R-mediated proliferative effects (Kitlinska et al., 2005). Similarly, the proliferative effect of NPY mediated by Y5R was observed in breast cancer cells (Tab. 1) (Medeiros et al., 2011; Sheriff et al., 2010). However, these studies were performed mainly in vitro, and the exact actions of the peptide in different subtypes of breast cancers in the context of the natural tumor microenvironment remain to be determined. For example, NPY acting via Y1R also expressed in breast cancer cells has been shown to inhibit estrogen-induced proliferation (Amlal et al., 2006). Interestingly, based on our unpublished preliminary data, breast cancer cells do not express endogenous NPY, suggesting that the effects on tumor cell proliferation are mediated solely by the systemic peptide that is released from peripheral sympathetic neurons.

Tumor cell survival and chemoresistance

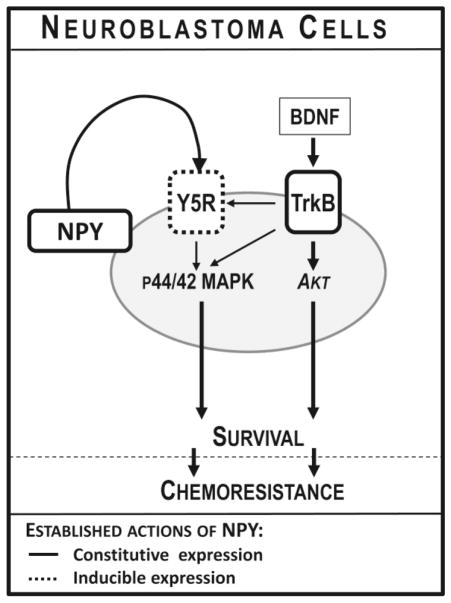

The main evidence for the role of NPY in promoting tumor cell survival and resistance to therapy come from our study on neuroblastoma. We have found that in addition to its role in augmenting proliferative effects of Y2R, Y5R acts as a survival factor for neuroblastoma cells (Czarnecka et al., 2015). While often not detectable under basal cell culture conditions, Y5R is induced in pro-apoptotic conditions, including serum withdrawal, hypoxia and chemotherapy (Tab 1). As these factors up-regulate NPY expression and release as well, these coordinated changes lead to activation of the NPY/Y5R pathway, which promotes neuroblastoma cell survival and resistance to chemotherapy via activation of the p44/42 MAPK pathway (Fig. 3) (Czarnecka et al., 2015). Consequently, chemoresistant cell lines derived from neuroblastoma patients with relapsing tumors have elevated NPY and Y5R expression, as compared to the corresponding cell lines obtained from the same patients at diagnosis. A similar increase in Y5R expression was observed in tissues from chemotherapy-treated neuroblastoma tumors. In line with this, blocking Y5R inhibited neuroblastoma xenograft growth via an increase in apoptosis and sensitized resistant neuroblastoma cells to chemotherapy (Czarnecka et al., 2015). This data supports previous clinical observations indicating associations of high NPY levels in neuroblasts infiltrating bone marrow, as well as a lack of normalization of systemic NPY after treatment with rapid neuroblastoma relapse and its fatal outcome (Dotsch et al., 1998; Nowicki et al., 2006; Rascher et al., 1993). As neuroblastoma cells originate from precursors of sympathetic neurons, the pro-survival effect of NPY in these cells is in line with its known neuroprotective activity in various types of normal neurons that are known to be mediated by the p44/42 MAPK pathway (Decressac et al., 2012; Malva et al., 2012).

Figure 3. Pro-survival effect of NPY in neuroblastoma.

Expression of Y5R is induced in neuroblastoma cells under pro-apoptotic conditions, including growth factor withdrawal, chemotherapy, lack of attachment and hypoxia. This activation of the NPY/Y5R pathway promotes neuroblastoma cell survival via activation of the p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. Y5R expression is also induced by brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a known neuroblastoma survival factor. Upon BDNF stimulation, tropomyosin-related kinase B receptor (TrkB) transactivates Y5R, which augments the pro-survival effects of this neurotrophin. Such TrkB-Y5R cross-talk selectively enhances BDNF-induced p44/42 MAPK, but not Akt activation. Both NPY- and BDNF-dependent Y5R stimulation promotes neuroblastoma cell resistance to chemotherapy.

In addition to mediating the pro-survival effects of NPY, Y5R is also involved in the signaling of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) via interactions with its cognate receptor, tropomyosin-related kinase B receptor (TrkB) (Czarnecka et al., 2015). BDNF is a known survival factor for neuroblastoma, involved in its chemoresistance (Ho et al., 2002; Jaboin et al., 2003; Jaboin et al., 2002; Li et al., 2007). In line with this, elevated expression of BDNF receptor, TrkB, is associated with worse prognosis in neuroblastoma patients (Brodeur et al., 2009; Brodeur et al., 1997; Nakagawara, 2001; Nakagawara et al., 1994; Nakagawara and Brodeur, 1997). The pro-survival effects of BDNF are mediated by two major pathways – phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt (PI3K/Akt) and p44/42 MAPK (Han and Holtzman, 2000; Ho et al., 2002; Jaboin et al., 2003; Jaboin et al., 2002; Klocker et al., 2000; Li et al., 2007; Skaper et al., 1998). We have shown that BDNF, acting via its TrkB receptor, up-regulates synthesis and release of NPY and induces Y5R expression (Tab 1) (Czarnecka et al., 2015). Once present in neuroblastoma cells, Y5R is trans-activated by TrkB upon BDNF stimulation, which selectively enhances BDNF-induced p44/42 MAPK activation and pro-survival activity of this neurotrophin (Fig. 3). Consequently, blocking Y5R signaling inhibits the ability of BDNF to promote neuroblastoma cell survival and resistance to therapy (Czarnecka et al., 2015). This cross-talk between NPY and BDNF pathways is in line with the known ability of Y5R to interact with other surface receptors, as well as interactions of the NPY system with synergistic pathways, such as the adrenergic axis (Gehlert et al., 2007; Movafagh et al., 2006; Pellieux et al., 2000; Pons et al., 2008; Pons et al., 2003).

In contrast to neuroblastoma, endogenous activity of the NPY/Y1R/Y5R autocrine loop promotes cell death rather than survival in Ewing sarcoma (Fig. 2A) (Kitlinska et al., 2005; Lu et al., 2011). This effect is mediated by the poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1/apoptosis inducing factor (PARP-1/AIF) pathway, which is known to trigger non-apoptotic programmed cell death (Lu et al., 2011). However, as described above, this activity is suppressed in the hypoxic tumor microenvironment and it does not seem to affect tumor growth, as Ewing sarcoma patients with elevated systemic NPY have a more adverse tumor phenotype (Tilan et al., 2014b; Tilan et al., 2013b). Instead, hypoxia-induced up-regulation of NPY3-36 release and Y5R expression may activate the NPY/Y5R pathway alone (Tilan et al., 2013b). Whether or not such a switch in NPY signaling may have a pro-survival effect in Ewing sarcoma, as seen in neuroblastoma cells, remains to be determined. Interestingly, the association of high NPY levels with future relapse has also been reported in prostate cancer (Tab. 1), suggesting a contribution of the NPY axis to therapy resistance in a broader range of malignancies (Rasiah et al., 2006).

Tumor vascularization

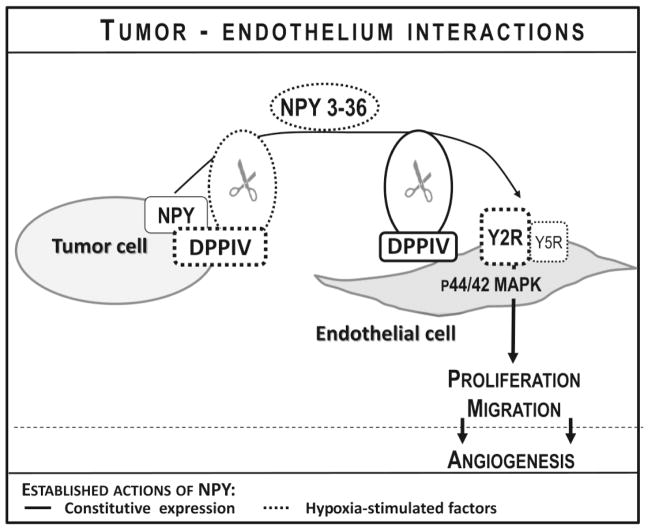

In addition to its direct effects on tumor cells, NPY can also affect the tumor microenvironment. One of the best-described functions of NPY that mediate tumor-host interactions is its angiogenic activity (Kitlinska et al., 2005; Lu et al., 2010; Medeiros and Jackson, 2013; Tilan et al., 2013b). The ability of NPY to stimulate blood vessel formation has been shown using a variety of models, including hindlimb ischemia, retinopathy and wound healing (Ekstrand et al., 2003; Koulu et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2003b; Niskanen et al., 2000; Tilan et al., 2013a; Yoon et al., 2002). Our studies have revealed a crucial role for the peptide in the vascularization of NPY-rich tumors (Kitlinska et al., 2005; Lu et al., 2010; Tilan et al., 2013b).

Y2R is the main angiogenic receptor of NPY (Ekstrand et al., 2003; Koulu et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2003a; Lee et al., 2003b). However, the role for Y5R in enhancing the effects of NPY in endothelial cells has also been demonstrated (Tab 1) (Movafagh et al., 2006). In both neuroblastoma and Ewing sarcoma tumors endothelium within tumor vasculature is highly positive for Y2R. We have shown that the expression of this receptor in endothelial cells is induced by hypoxia, which sensitizes them to the proliferative effects of NPY (Lu et al., 2010; Tilan et al., 2013b). Simultaneously, hypoxia-induced up-regulation of NPY expression and DPPIV activity in Ewing sarcoma cells leads to elevated peptide release in its cleaved form, NPY3-36, further promoting activation of endothelial Y2R and thereby stimulating proliferation (Fig. 4) (Tilan et al., 2013b). DPPIV is also present in endothelial cells themselves and its activity is essential for activation of Y2Rs in the presence of constitutively expressed Y1R in these cells (Ghersi et al., 2001; Kitlinska et al., 2003). Consequently, treatment of both neuroblastoma and Ewing sarcoma xenografts with Y2R antagonist resulted in a significant decrease in tumor vascularization (Lu et al., 2010; Tilan et al., 2013b). Interestingly, vasculature within neuroblastoma tumors is also highly positive for Y5R (unpublished data). While the Y5R antagonist alone did not inhibit vascularization of neuroblastoma xenografts, it is plausible that the combination of both Y2R and Y5R antagonists could have an enhanced anti-angiogenic effect (Czarnecka et al., 2015).

Figure 4. Effect of NPY on tumor vascularization.

NPY released from tumor cells acts on endothelial cells, stimulating their proliferation, migration and ultimately vessel formation. Y2R is the main angiogenic receptor of NPY, while Y5R enhances this effect. Expression of these pro-angiogenic receptors is induced in endothelial cells by hypoxia or the presence of their ligand, NPY. The angiogenic activity of NPY is augmented by dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPPIV), the enzyme that converts NPY to a selective Y2R/Y5R agonist, NPY3-36, and facilitates activation of these two receptors in endothelial cells. DPPIV is constitutively expressed in endothelial cells and can be induced in tumor cells by hypoxia.

In addition to its direct effects on endothelial cells, NPY has also been shown to interact with the main hypoxia-inducible angiogenic pathway – vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) axis (Lee et al., 2003b). In line with this, NPY treatment in breast cancer cells stimulated VEGF release (Medeiros and Jackson, 2013). Whether or not this mechanism is crucial for vascularization of NPY-rich pediatric tumors has not been investigated.

While angiogenesis is the main process providing blood supply to solid tumors, some tumor types, including Ewing sarcoma, have developed vascular mimicry as an alternative way of increasing tissue perfusion (Sun et al., 2004). In this process, hypoxic tumor cells form pseudo-vessels (also called blood lakes) without a contribution from normal vascular cells (van der Schaft et al., 2005). Interestingly, aside from its presence in endothelial cells within Ewing sarcoma vasculature, Y2R was also abundantly expressed in tumor cells surrounding blood lakes in these tumors (Tilan et al., 2013b). The elevated expression of Y2R in these structures could simply reflect the hypoxic state of the cells that build blood lakes. However, the contribution of NPY/Y2R signaling to their formation cannot be excluded and deserves further investigation.

Tumor invasiveness and metastases

While the evidence for the effect of NPY on the growth of various tumor types is growing, its role in promoting tumor metastases is a new area of research. In tumors with endogenous NPY expression – neuroblastoma, Ewing sarcoma and pheochromocytoma – elevated systemic NPY is associated with the presence of metastases (Cohen et al., 1990; Dotsch et al., 1998; Grouzmann et al., 1990; Kogner et al., 1994; Tilan et al., 2014b). Notably, in neuroblastoma, this was true also for stage 4S tumors, which present with metastases at early stages despite their overall good prognosis, implicating NPY as a general marker of the metastatic disease (Dotsch et al., 1998). Moreover, high tissue NPY was associated with an invasive phenotype of melanoma and prostate cancer (Gilaberte et al., 2012; Rasiah et al., 2006). In line with these clinical findings, we have observed a stimulatory effect of the peptide on tumor cell motility and invasiveness. We have shown that hypoxia-inducible NPY3-36/Y2R/Y5R pathway promotes migration of ALDHhigh cancer stem cells in Ewing sarcoma (Fig. 2B) (Tilan et al., 2013b). Since hypoxia facilitates the development of distant metastases, and cancer stem cells are believed to be responsible for their initiation, our data strongly implicate the NPY axis as a mediator of this effect (Das et al., 2008; Mujcic et al., 2014; Toffoli and Michiels, 2008; Zhou and Zhang, 2008). In line with this notion, in the in vivo model of Ewing sarcoma, NPY and Y5R were highly up-regulated in distant metastases, as compared to the corresponding primary tumors (Hong et al., 2015). Expression of Y2R, in turn, was elevated in tissues derived from local relapses, suggesting its role in tumor cell invasiveness. The latter observation is in agreement with our clinical data. While Y5R was highly expressed in all human Ewing sarcoma tissues, immunostaining for Y2R was variable and its high levels tended to associate with worse patient survival (Tilan et al., 2013b).

As described above, our data implicate the NPY/Y2R/Y5R pathway in various stages of Ewing sarcoma metastasis. However, we have also observed an NPY-induced increase in invasiveness of neuroblastoma cells, which express Y2R and Y5R (Fig. 1, unpublished data). Similarly, NPY has been shown to stimulate the migration of breast cancer cells via its Y5R (Tab 1) (Medeiros et al., 2011). Altogether, these findings warrant further investigations into the role of NPY in tumor metastasis. Importantly, the invasive and migratory properties of tumor cells described above are only part of this complex process, as formation of metastases requires interactions between tumor and host cells as well. The role of NPY in these aspects of metastasis thus far remains unexplored.

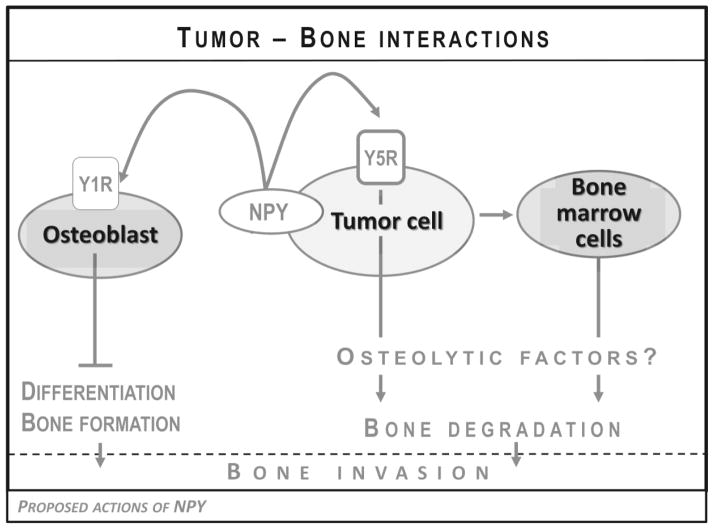

Bone invasion

Among its many pleiotropic functions, NPY is also a known regulator of bone homeostasis (Baldock et al., 2007; Igwe et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2010; Lee and Herzog, 2009). While some of its effects depend on the central regulation of bone physiology, peripherally, the peptide has been shown to inhibit osteoblast differentiation via Y1R present in these cells (Tab. 1) (Baldock et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2010; Lee and Herzog, 2009). These local actions in the bone environment can be highly relevant to NPY-rich tumors. Ewing sarcoma often presents as a primary osseous tumor, while both neuroblastoma and Ewing sarcoma metastasize to the bone at the advanced stage of the disease (Lessnick and Ladanyi, 2012; Maris, 2010). These bone lesions are considered osteolytic. However, bone remodeling of any kind, including tumor-induced bone destruction, requires both osteoblastic and osteoclastic activity, while the final effect depends on the balance between these processes. Thus, blocking the osteoblast differentiation that is induced by tumor-derived NPY could shift this balance toward osteolysis observed in neuroblastoma and Ewing sarcoma bone lesions (Fig. 5). This potential shift could be particularly relevant to pediatric patients, with ongoing bone formation processes.

Figure 5. Proposed mechanisms of bone destruction induced by tumor-derived NPY.

NPY released from tumor cells can directly inhibit osteoblast differentiation via Y1R expressed in these cells and thereby shift the bone homeostasis toward osteolysis. Moreover, elevated NPY and Y5R expression in bone metastases suggests that the NPY/Y5R autocrine loop in tumor cells may increase their capability of invading bone tissue. This may be due to the increased release of osteolytic factors, either directly from tumor cells or indirectly, via interactions with bone marrow cells.

In support of this hypothesis, we reported that the degree of bone destruction in Ewing sarcoma primary tumors derived from our in vivo xenograft model correlated with the level of NPY release from these tumors and was significantly reduced by NPY shRNA (Hong et al., 2015). Moreover, in these primary osseous tumors, the expression of NPY exhibited a characteristic gradient, with an increased intensity of NPY immunostaining in tumor cells directly surrounding bone invasion areas, as compared to cells distant from bone. The highest NPY expression was observed in tumor cells directly invading bone. These observations from the animal model correlated with elevated systemic levels of NPY and its tumor tissue mRNA observed in Ewing sarcoma patients with bone tumors, as compared to those with extraosseous lesions (Tilan et al., 2014b).

In the in vivo model of Ewing sarcoma, high NPY release from the tumor cells was also associated with frequent distant metastases to the bones, while pulmonary metastases prevailed in the tumors derived from cells not releasing the peptide (Hong et al., 2015). Notably, expression of both NPY and Y5R was highly elevated specifically in bone, but not soft tissue metastases.

Altogether, our data strongly support the role for the NPY/Y5R axis in tumor-induced bone invasion. However, further studies are required to decipher the mechanisms of this effect. The interactions of tumor-derived NPY with osteoblasts and perhaps other cells within the bone microenvironment may partially explain this phenomenon (Fig. 5). However, the elevated Y5R expression that is characteristic for bone metastases suggests that activation of the NPY/Y5R axis in Ewing sarcoma cells may change their phenotype and increase their capability to invade bone tissue. This could be, for example, associated with the release of other osteolytic factors (Fig. 5). Studies designed to elucidate these mechanisms are currently in progress in our laboratory.

Other aspects of NPY actions

Aside from multiple activities of NPY that are currently under investigation in the context of tumor biology, there are also other aspects of its multifaceted functions that could be relevant to oncology. For example, activation of Y2R in neuroblastoma cells has been shown to stimulate glycolysis, the main metabolic pathway activated in hypoxic cells to produce ATP under low oxygen conditions (Wang et al., 2015). As such, this pathway is crucial for tumor cells to survive hypoxia. Given high expression of Y2R in neuroblastoma and its induction in hypoxic Ewing sarcoma cells, the NPY/Y2R axis may contribute to this survival mechanism (Lu et al., 2010; Tilan et al., 2013b).

Furthermore, NPY has been shown to regulate the differentiation of a variety of cells (Han et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2010; Son et al., 2011). Of particular interest is the role of the Y1R/Y5R pathway in maintaining human embryonic stem cell self-renewal and pluripotency (Son et al., 2011). As these two receptors are also highly and constitutively expressed in Ewing sarcoma cells, it is plausible that the NPY/Y1R/Y5R may play a role in maintaining a highly undifferentiated phenotype of these tumors (Kitlinska et al., 2005; Lu et al., 2011). Both Y1R and Y5R can also be expressed in breast cancer cells (Amlal et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2015; Medeiros et al., 2011; Medeiros and Jackson, 2013; Reubi et al., 2001; Sheriff et al., 2010). As defects in cell differentiation are central to the malignant tumor phenotype, this aspect of NPY actions is certainly worth exploring.

Clinical implications

As described above, in both neuroblastoma and Ewing sarcoma high NPY release associates with a malignant phenotype, while our experimental data support the role for a NPY/Y2R/Y5R axis in their growth and dissemination (Cohen et al., 1990; Czarnecka et al., 2015; Dotsch et al., 1998; Hong et al., 2015; Kitlinska et al., 2005; Kogner et al., 1994; Lu et al., 2010; Lu et al., 2011; Tilan et al., 2014b; Tilan et al., 2013b). Thus, elucidating the processes underlying these actions of NPY may lead to the development of novel therapies preventing tumor progression in both neuroblastoma and Ewing sarcoma patients. The benefits from such therapies include the following characteristics: 1) Pleiotropic effects. Our data indicate that NPY is involved in multiple processes stimulating tumor growth and progression. Using in vivo xenograft models, we have already demonstrated that treatment with Y2R antagonist inhibits angiogenesis in both pediatric tumor types, while in neuroblastoma Y2R and Y5R antagonists inhibit tumor growth via their anti-proliferative and anti-apoptotic activities, respectively (Czarnecka et al., 2015; Lu et al., 2010; Tilan et al., 2013b). The effects of such treatments on disease progression, e.g. metastasis and chemoresistance, remain to be determined. Nevertheless, current data strongly support this notion. 2) Universal nature. NPY is expressed in all cases of neuroblastoma and Ewing sarcoma (Kitlinska et al., 2005; Lu et al., 2010; Lu et al., 2011; Tilan et al., 2014a). Thus, therapies targeting this pathway may apply to a broad group of neuroblastoma and Ewing sarcoma patients. Recent improvements in pediatric patient outcome occurred due to the introduction of similar biology-based therapies, e.g. retinoic acid-induced differentiation, suggesting that targeting the Y2R/Y5R axis may become an equally successful treatment (Maris, 2010). 3) Translatability. A variety of potent and specific NPY receptor antagonists is already available and their number is growing. Many of them have been used in animal models and clinical trials, giving promise for the rapid translation of the preclinical findings (Erondu et al., 2006; Erondu et al., 2007; Kitlinska et al., 2005; Lu et al., 2010; Lu et al., 2011). 4) Safety. Blocking NPY and its receptors does not interfere with normal development, since mice lacking the peptide or its Y2R or Y5R have no major defects (Lin et al., 2004; Thorsell and Heilig, 2002). Similarly, no significant side effects associated with administration of NPY receptor antagonists in animals and people have been reported (Criscione et al., 1998; Erondu et al., 2006; Erondu et al., 2007; Lecklin et al., 2002; Malmstrom, 2001; Sajdyk et al., 1999). These features are crucial in the treatment of pediatric patients.

A potential clinical challenge associated with blocking NPY actions in cancer patients would be interfering with its known orexigenic effect and role in the regulation of energy homeostasis, as anorexia-cachexia syndrome is one of the most important factors contributing to morbidity and mortality in this population (Laviano et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2011). Yet, among all NPY receptors, Y2R present in the brain is the one responsible for anorexigenic effects of NPY. Consequently, the administration of Y2R antagonists increases food intake via central effects (Zhang et al., 2011). On the other hand, blocking Y2R in the periphery shifts the energy balance from fat accumulation to an increase in lean mass, the loss of which is the main problem in cachexic patients (Laviano et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2011). Thus, blocking the NPY/Y2R axis in cancer patients can potentially alleviate the detrimental effects of anorexia-cachexia syndrome. On the other hand, selective inhibition of Y5R signaling has indeed been shown to decrease food intake via its central activities (Zhang et al., 2011). However, although the weight loss induced by Y5R antagonist was statistically significant, the effect was minor and therefore not clinically meaningful (Erondu et al., 2006; Erondu et al., 2007). Thus, while the potential anorexigenic effects of Y5R blockage in cancer patients would have to be carefully monitored, they also do not seem to be severe. Lastly, the use of a brain-impenetrable Y5R antagonist could prevent such adverse central effects, while preserving peripheral activities on tumor growth and metastasis.

Aside from direct inhibition of NPY signaling with selective receptor antagonists, the high and universal expression of its surface receptors provides an opportunity for targeting neuroblastoma and Ewing sarcoma cells with ligands carrying radionuclides and chemotherapeutics in imaging and therapeutic applications, as previously proposed (Bohme and Beck-Sickinger, 2015). A similar strategy using the catecholamine analog, metaiodobenzylguanidin, has been successfully employed for monitoring neuroblastoma and is currently in clinical trials for its treatment (Maris, 2010; Yanik et al., 2015).

Implications for role of neuronal NPY in tumor biology

Aside from being synthesized in tumor cells, NPY is also released systemically from sympathetic neurons (Zukowska-Grojec, 1995). Thus, the growth-promoting actions of the peptide identified in NPY-rich pediatric tumors may also be relevant to other tumor types that express its receptors, yet do not synthesize the endogenous peptide. For example, as described above, in breast cancer, activation of Y5R stimulates cancer cell proliferation and migration (Medeiros et al., 2011; Medeiros and Jackson, 2013; Sheriff et al., 2010; Ueda et al., 2013). Importantly, systemic release of NPY may be triggered by factors common in cancer patients, such as chronic psychological stress or local hypoxia (Zukowska-Grojec, 1995). In line with this, chronic stress has been shown to increase the frequency and extent of bone metastasis in a breast cancer model (Campbell et al., 2012). While this particular study focused on the role of the adrenergic system and used a stress model favoring catecholamine release, the role of NPY in this process cannot be excluded, particularly given previously established synergistic interactions between these two systems (Pellieux et al., 2000; Pons et al., 2003). NPY release can also change with the metabolic state of the patients. For example, in an animal model of melanoma, host obesity increased tumor growth and Y2R blocked this effect by interfering with tumor vascularization (Alasvand et al., 2015). Thus, implications of studies performed on neuroblastoma and Ewing sarcoma as models of NPY-rich tumors may reach far beyond pediatric malignancies that endogenously express NPY. Nevertheless, it is important to remember that despite many similarities between actions of the peptide in different tumor types, its effects are still tumor specific. For example, in colorectal cancer and cholangiocarcinoma NPY inhibits cancer cell proliferation and invasiveness, while in prostate cancer cells its effects vary between cell lines (Tab. 1) (DeMorrow et al., 2011; Ogasawara et al., 1997; Ruscica et al., 2007). Yet, studies confirming these findings in an orthotopic tumor microenvironment are still needed, as a full understanding of NPY actions in particular tumor types and their environment is crucial for designing rational therapies targeting this pathway.

Conclusions

Recent years have brought significant progress in our understanding of the role of NPY in promoting tumor growth, as well as new insights into its effects on tumor progression to a metastatic and chemoresistant phenotype. Of particular importance are interactions of the NPY system with the tumor microenvironment and the profound effect of hypoxia on its expression pattern and functions (Lu et al., 2010; Tilan et al., 2013b). These findings underscore an importance of investigating NPY actions in the natural tumor microenvironment. While the work on deciphering the mechanisms by which NPY can affect complex processes underlying tumor progression is still in progress, the existing data strongly support the value of the peptide and its receptors as therapeutic targets in oncology. Moreover, strong associations of elevated systemic NPY with adverse disease phenotype implicate its role in tumor stratification and monitoring.

Highlights.

NPY regulates numerous processes involved in tumor growth and progression, including cell proliferation, survival, differentiation, motility and angiogenesis.

Pediatric malignancies with high endogenous NPY expression – neuroblastoma and Ewing sarcoma – are excellent models to identify functions of NPY in tumor biology.

The actions of NPY promoting neuroblastoma and Ewing sarcoma growth and progression are mediated by its Y2R and Y5R that could become therapeutic targets for these tumors.

Expression pattern and functions of the NPY system are regulated by the hypoxic tumor microenvironment, underscoring the importance of investigating its activity in orthotopic in vivo models.

The results of the studies on NPY-rich pediatric tumors may be relevant to other malignancies expressing NPY receptors and exposed to the peptide released from sympathetic neurons, particularly in pathological conditions associated with elevated systemic NPY, such as chronic stress.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants: UL1TR000101 (previously UL1RR031975) through the Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program, 1RO1CA123211, 1R21CA198698, R01 CA197964-01 and 1R03CA178809, as well as funding from Children’s Cancer Foundation to JK. The experiments were performed with use of Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center Shared Resources supported by NIH/NCI grant P30-CA051008.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alasvand M, Rashidi B, Javanmard SH, Akhavan MM, Khazaei M. Effect of blocking of neuropeptide Y Y2 receptor on tumor angiogenesis and progression in normal and diet-induced obese C57BL/6 Mice. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;7:46883. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v7n7p69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amlal H, Faroqui S, Balasubramaniam A, Sheriff S. Estrogen up-regulates neuropeptide Y Y1 receptor expression in a human breast cancer cell line. Cancer research. 2006;66:3706–3714. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aryee DN, Niedan S, Kauer M, Schwentner R, Bennani-Baiti IM, Ban J, Muehlbacher K, Kreppel M, Walker RL, Meltzer P, Poremba C, Kofler R, Kovar H. Hypoxia modulates EWS-FLI1 transcriptional signature and enhances the malignant properties of Ewing’s sarcoma cells in vitro. Cancer research. 2010;70:4015–4023. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad O, Yustein JT, Shah P, Gul N, Katuri V, O’Neill A, Kong Y, Brown ML, Toretsky JA, Loeb DM. High ALDH activity identifies chemotherapy-resistant Ewing’s sarcoma stem cells that retain sensitivity to EWS-FLI1 inhibition. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13943. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldock PA, Allison SJ, Lundberg P, Lee NJ, Slack K, Lin EJ, Enriquez RF, McDonald MM, Zhang L, During MJ, Little DG, Eisman JA, Gardiner EM, Yulyaningsih E, Lin S, Sainsbury A, Herzog H. Novel role of Y1 receptors in the coordinated regulation of bone and energy homeostasis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:19092–19102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700644200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batra S, Reynolds CP, Maurer BJ. Fenretinide cytotoxicity for Ewing’s sarcoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumor cell lines is decreased by hypoxia and synergistically enhanced by ceramide modulators. Cancer research. 2004;64:5415–5424. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohme D, Beck-Sickinger AG. Drug delivery and release systems for targeted tumor therapy. J Pept Sci. 2015;21:186–200. doi: 10.1002/psc.2753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodeur GM, Minturn JE, Ho R, Simpson AM, Iyer R, Varela CR, Light JE, Kolla V, Evans AE. Trk receptor expression and inhibition in neuroblastomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3244–3250. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodeur GM, Nakagawara A, Yamashiro DJ, Ikegaki N, Liu XG, Azar CG, Lee CP, Evans AE. Expression of TrkA, TrkB and TrkC in human neuroblastomas. J Neurooncol. 1997;31:49–55. doi: 10.1023/a:1005729329526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JP, Karolak MR, Ma Y, Perrien DS, Masood-Campbell SK, Penner NL, Munoz SA, Zijlstra A, Yang X, Sterling JA, Elefteriou F. Stimulation of host bone marrow stromal cells by sympathetic nerves promotes breast cancer bone metastasis in mice. PLoS Biol. 2012;10:e1001363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen PS, Cooper MJ, Helman LJ, Thiele CJ, Seeger RC, Israel MA. Neuropeptide Y expression in the developing adrenal gland and in childhood neuroblastoma tumors. Cancer research. 1990;50:6055–6061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn SL, Pearson AD, London WB, Monclair T, Ambros PF, Brodeur GM, Faldum A, Hero B, Iehara T, Machin D, Mosseri V, Simon T, Garaventa A, Castel V, Matthay KK. The International Neuroblastoma Risk Group (INRG) classification system: an INRG Task Force report. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:289–297. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.6785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles EG, Lawlor ER, Bronner-Fraser M. EWS-FLI1 causes neuroepithelial defects and abrogates emigration of neural crest stem cells. Stem cells (Dayton, Ohio) 2008;26:2237–2244. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criscione L, Rigollier P, Batzl-Hartmann C, Rueger H, Stricker-Krongrad A, Wyss P, Brunner L, Whitebread S, Yamaguchi Y, Gerald C, Heurich RO, Walker MW, Chiesi M, Schilling W, Hofbauer KG, Levens N. Food intake in free-feeding and energy-deprived lean rats is mediated by the neuropeptide Y5 receptor. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:2136–2145. doi: 10.1172/JCI4188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czarnecka M, Trinh E, Lu C, Kuan-Celarier A, Galli S, Hong SH, Tilan JU, Talisman N, Izycka-Swieszewska E, Tsuei J, Yang C, Martin S, Horton M, Christian D, Everhart L, Maheswaran I, Kitlinska J. Neuropeptide Y receptor Y5 as an inducible pro-survival factor in neuroblastoma: implications for tumor chemoresistance. Oncogene. 2015;34:3131–3143. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das B, Tsuchida R, Malkin D, Koren G, Baruchel S, Yeger H. Hypoxia enhances tumor stemness by increasing the invasive and tumorigenic side population fraction. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1818–1830. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de SSP, Denker J, Bravo EL, Graham RM. Production, characterization, and expression of neuropeptide Y by human pheochromocytoma. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2503–2509. doi: 10.1172/JCI118310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decressac M, Pain S, Chabeauti PY, Frangeul L, Thiriet N, Herzog H, Vergote J, Chalon S, Jaber M, Gaillard A. Neuroprotection by neuropeptide Y in cell and animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:2125–2137. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMorrow S, Onori P, Venter J, Invernizzi P, Frampton G, White M, Franchitto A, Kopriva S, Bernuzzi F, Francis H, Coufal M, Glaser S, Fava G, Meng F, Alvaro D, Carpino G, Gaudio E, Alpini G. Neuropeptide Y inhibits cholangiocarcinoma cell growth and invasion. American journal of physiology. 2011;300:C1078–1089. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00358.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotsch J, Christiansen H, Hanze J, Lampert F, Rascher W. Plasma neuropeptide Y of children with neuroblastoma in relation to stage, age and prognosis, and tissue neuropeptide Y. Regul Pept. 1998;75–76:185–190. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(98)00067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunst J, Ahrens S, Paulussen M, Burdach S, Jurgens H. Prognostic impact of tumor perfusion in MR-imaging studies in Ewing tumors. Strahlenther Onkol. 2001;177:153–159. doi: 10.1007/s00066-001-0804-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrand AJ, Cao R, Bjorndahl M, Nystrom S, Jonsson-Rylander AC, Hassani H, Hallberg B, Nordlander M, Cao Y. Deletion of neuropeptide Y (NPY) 2 receptor in mice results in blockage of NPY-induced angiogenesis and delayed wound healing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:6033–6038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1135965100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erondu N, Gantz I, Musser B, Suryawanshi S, Mallick M, Addy C, Cote J, Bray G, Fujioka K, Bays H, Hollander P, Sanabria-Bohorquez SM, Eng W, Langstrom B, Hargreaves RJ, Burns HD, Kanatani A, Fukami T, MacNeil DJ, Gottesdiener KM, Amatruda JM, Kaufman KD, Heymsfield SB. Neuropeptide Y5 receptor antagonism does not induce clinically meaningful weight loss in overweight and obese adults. Cell metabolism. 2006;4:275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erondu N, Wadden T, Gantz I, Musser B, Nguyen AM, Bays H, Bray G, O’Neil PM, Basdevant A, Kaufman KD, Heymsfield SB, Amatruda JM. Effect of NPY5R antagonist MK-0557 on weight regain after very-low-calorie diet-induced weight loss. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md. 2007;15:895–905. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehlert DR, Schober DA, Morin M, Berglund MM. Co-expression of neuropeptide Y Y1 and Y5 receptors results in heterodimerization and altered functional properties. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74:1652–1664. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghersi G, Chen W, Lee EW, Zukowska Z. Critical role of dipeptidyl peptidase IV in neuropeptide Y-mediated endothelial cell migration in response to wounding. Peptides. 2001;22:453–458. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(01)00340-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilaberte Y, Roca MJ, Garcia-Prats MD, Coscojuela C, Arbues MD, Vera-Alvarez JJ. Neuropeptide Y expression in cutaneous melanoma. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2012;66:e201–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grouzmann E, Gicquel C, Plouin PF, Schlumberger M, Comoy E, Bohuon C. Neuropeptide Y and neuron-specific enolase levels in benign and malignant pheochromocytomas. Cancer. 1990;66:1833–1835. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19901015)66:8<1833::aid-cncr2820660831>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han BH, Holtzman DM. BDNF protects the neonatal brain from hypoxic-ischemic injury in vivo via the ERK pathway. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5775–5781. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05775.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han R, Kitlinska JB, Munday WR, Gallicano GI, Zukowska Z. Stress hormone epinephrine enhances adipogenesis in murine embryonic stem cells by up-regulating the neuropeptide Y system. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock JD, Lessnick SL. A transcriptional profiling meta-analysis reveals a core EWS-FLI gene expression signature. Cell cycle (Georgetown, Tex) 2008;7:250–256. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.2.5229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansel DE, Eipper BA, Ronnett GV. Neuropeptide Y functions as a neuroproliferative factor. Nature. 2001;410:940–944. doi: 10.1038/35073601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho R, Eggert A, Hishiki T, Minturn JE, Ikegaki N, Foster P, Camoratto AM, Evans AE, Brodeur GM. Resistance to chemotherapy mediated by TrkB in neuroblastomas. Cancer research. 2002;62:6462–6466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong SH, Tilan JU, Galli S, Izycka-Swieszewska E, Polk T, Horton M, Mahajan A, Christian D, Jenkins S, Acree R, Connors K, Ledo P, Lu C, Lee YC, Rodriguez O, Toretsky JA, Albanese C, Kitlinska J. High neuropeptide Y release associates with Ewing sarcoma bone dissemination - in vivo model of site-specific metastases. Oncotarget. 2015;6:7151–7165. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igwe JC, Jiang X, Paic F, Ma L, Adams DJ, Baldock PA, Pilbeam CC, Kalajzic I. Neuropeptide Y is expressed by osteocytes and can inhibit osteoblastic activity. J Cell Biochem. 2009;108:621–630. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaboin J, Hong A, Kim CJ, Thiele CJ. Cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity is blocked by brain-derived neurotrophic factor activation of TrkB signal transduction path in neuroblastoma. Cancer Lett. 2003;193:109–114. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00723-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaboin J, Kim CJ, Kaplan DR, Thiele CJ. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor activation of TrkB protects neuroblastoma cells from chemotherapy-induced apoptosis via phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase pathway. Cancer research. 2002;62:6756–6763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilic M, Kasperczyk H, Fulda S, Debatin KM. Role of hypoxia inducible factor-1 alpha in modulation of apoptosis resistance. Oncogene. 2007;26:2027–2038. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitlinska J, Abe K, Kuo L, Pons J, Yu M, Li L, Tilan J, Everhart L, Lee EW, Zukowska Z, Toretsky JA. Differential effects of neuropeptide Y on the growth and vascularization of neural crest-derived tumors. Cancer research. 2005;65:1719–1728. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitlinska J, Lee EW, Li L, Pons J, Estes L, Zukowska Z. Dual role of dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP IV) in angiogenesis and vascular remodeling. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;524:215–222. doi: 10.1007/0-306-47920-6_26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klocker N, Kermer P, Weishaupt JH, Labes M, Ankerhold R, Bahr M. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor-mediated neuroprotection of adult rat retinal ganglion cells in vivo does not exclusively depend on phosphatidyl-inositol-3′-kinase/protein kinase B signaling. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6962–6967. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-06962.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles HJ, Schaefer KL, Dirksen U, Athanasou NA. Hypoxia and hypoglycaemia in Ewing’s sarcoma and osteosarcoma: regulation and phenotypic effects of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor. BMC cancer. 2010;10:372. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogner P, Bjork O, Theodorsson E. Plasma neuropeptide Y in healthy children: influence of age, anaesthesia and the establishment of an age-adjusted reference interval. Acta Paediatr. 1994;83:423–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb18134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korner M, Waser B, Reubi JC. High expression of neuropeptide Y1 receptors in ewing sarcoma tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5043–5049. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koulu M, Movafagh S, Tuohimaa J, Jaakkola U, Kallio J, Pesonen U, Geng Y, Karvonen MK, Vainio-Jylha E, Pollonen M, Kaipio-Salmi K, Seppala H, Lee EW, Higgins RD, Zukowska Z. Neuropeptide Y and Y2-receptor are involved in development of diabetic retinopathy and retinal neovascularization. Ann Med. 2004;36:232–240. doi: 10.1080/07853890410031236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladenstein R, Potschger U, Le Deley MC, Whelan J, Paulussen M, Oberlin O, van den Berg H, Dirksen U, Hjorth L, Michon J, Lewis I, Craft A, Jurgens H. Primary disseminated multifocal Ewing sarcoma: results of the Euro-EWING 99 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3284–3291. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.9864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laviano A, Meguid MM, Inui A, Muscaritoli M, Rossi-Fanelli F. Therapy insight: Cancer anorexia-cachexia syndrome--when all you can eat is yourself. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2005;2:158–165. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecklin A, Lundell I, Paananen L, Wikberg JE, Mannisto PT, Larhammar D. Receptor subtypes Y1 and Y5 mediate neuropeptide Y induced feeding in the guinea-pig. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;135:2029–2037. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EW, Grant DS, Movafagh S, Zukowska Z. Impaired angiogenesis in neuropeptide Y (NPY)-Y2 receptor knockout mice. Peptides. 2003a;24:99–106. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(02)00281-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EW, Michalkiewicz M, Kitlinska J, Kalezic I, Switalska H, Yoo P, Sangkharat A, Ji H, Li L, Michalkiewicz T, Ljubisavljevic M, Johansson H, Grant DS, Zukowska Z. Neuropeptide Y induces ischemic angiogenesis and restores function of ischemic skeletal muscles. J Clin Invest. 2003b;111:1853–1862. doi: 10.1172/JCI16929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee NJ, Doyle KL, Sainsbury A, Enriquez RF, Hort YJ, Riepler SJ, Baldock PA, Herzog H. Critical role for Y1 receptors in mesenchymal progenitor cell differentiation and osteoblast activity. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:1736–1747. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee NJ, Herzog H. NPY regulation of bone remodelling. Neuropeptides. 2009;43:457–463. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenkinski RE, Bloch BN, Liu F, Frangioni JV, Perner S, Rubin MA, Genega EM, Rofsky NM, Gaston SM. An illustration of the potential for mapping MRI/MRS parameters with genetic over-expression profiles in human prostate cancer. MAGMA. 2008;21:411–421. doi: 10.1007/s10334-008-0133-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessnick SL, Ladanyi M. Molecular pathogenesis of Ewing sarcoma: new therapeutic and transcriptional targets. Annu Rev Pathol. 2012;7:145–159. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Zhang J, Liu Z, Woo CW, Thiele CJ. Downregulation of Bim by brain-derived neurotrophic factor activation of TrkB protects neuroblastoma cells from paclitaxel but not etoposide or cisplatin-induced cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:318–326. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S, Boey D, Herzog H. NPY and Y receptors: lessons from transgenic and knockout models. Neuropeptides. 2004;38:189–200. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Xu Q, Cheng L, Ma C, Xiao L, Xu D, Gao Y, Wang J, Song H. NPY1R is a novel peripheral blood marker predictive of metastasis and prognosis in breast cancer patients. Oncol Lett. 2015;9:891–896. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Everhart L, Tilan J, Kuo L, Sun CC, Munivenkatappa RB, Jonsson-Rylander AC, Sun J, Kuan-Celarier A, Li L, Abe K, Zukowska Z, Toretsky JA, Kitlinska J. Neuropeptide Y and its Y2 receptor: potential targets in neuroblastoma therapy. Oncogene. 2010 doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Tilan JU, Everhart L, Czarnecka M, Soldin SJ, Mendu DR, Jeha D, Hanafy J, Lee CK, Sun J, Izycka-Swieszewska E, Toretsky JA, Kitlinska J. Dipeptidyl peptidases as survival factors in Ewing sarcoma family of tumors: implications for tumor biology and therapy. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:27494–27505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.224089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magni P, Motta M. Expression of neuropeptide Y receptors in human prostate cancer cells. Ann Oncol. 2001;12(Suppl 2):S27–29. doi: 10.1093/annonc/12.suppl_2.s27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magwere T, Burchill SA. Heterogeneous role of the glutathione antioxidant system in modulating the response of ESFT to fenretinide in normoxia and hypoxia. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmstrom RE. Vascular pharmacology of BIIE0246, the first selective non-peptide neuropeptide Y Y(2) receptor antagonist, in vivo. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;133:1073–1080. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malva JO, Xapelli S, Baptista S, Valero J, Agasse F, Ferreira R, Silva AP. Multifaces of neuropeptide Y in the brain--neuroprotection, neurogenesis and neuroinflammation. Neuropeptides. 2012;46:299–308. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maris JM. Recent advances in neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2202–2211. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maris JM, Morton CL, Gorlick R, Kolb EA, Lock R, Carol H, Keir ST, Reynolds CP, Kang MH, Wu J, Smith MA, Houghton PJ. Initial testing of the aurora kinase A inhibitor MLN8237 by the Pediatric Preclinical Testing Program (PPTP) Pediatric blood & cancer. 2010;55:26–34. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros PJ, Al-Khazraji BK, Novielli NM, Postovit LM, Chambers AF, Jackson DN. Neuropeptide Y stimulates proliferation and migration in the 4T1 breast cancer cell line. International journal of cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1002/ijc.26350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros PJ, Jackson DN. Neuropeptide Y Y5-receptor activation on breast cancer cells acts as a paracrine system that stimulates VEGF expression and secretion to promote angiogenesis. Peptides. 2013;48:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2013.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mentlein R, Dahms P, Grandt D, Kruger R. Proteolytic processing of neuropeptide Y and peptide YY by dipeptidyl peptidase IV. Regul Pept. 1993;49:133–144. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(93)90435-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monument MJ, Bernthal NM, Randall RL. Salient features of mesenchymal stem cells-implications for Ewing sarcoma modeling. Frontiers in oncology. 2013;3:24. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Movafagh S, Hobson JP, Spiegel S, Kleinman HK, Zukowska Z. Neuropeptide Y induces migration, proliferation, and tube formation of endothelial cells bimodally via Y1, Y2, and Y5 receptors. Faseb J. 2006;20:1924–1926. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4770fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mujcic H, Hill RP, Koritzinsky M, Wouters BG. Hypoxia signaling and the metastatic phenotype. Curr Mol Med. 2014;14:565–579. doi: 10.2174/1566524014666140603115831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawara A. Trk receptor tyrosine kinases: a bridge between cancer and neural development. Cancer letters. 2001;169:107–114. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00530-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawara A, Azar CG, Scavarda NJ, Brodeur GM. Expression and function of TRK-B and BDNF in human neuroblastomas. Molecular and cellular biology. 1994;14:759–767. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawara A, Brodeur GM. Role of neurotrophins and their receptors in human neuroblastomas: a primary culture study. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:2050–2053. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)00280-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niskanen L, Voutilainen-Kaunisto R, Terasvirta M, Karvonen MK, Valve R, Pesonen U, Laakso M, Uusitupa MI, Koulu M. Leucine 7 to proline 7 polymorphism in the neuropeptide y gene is associated with retinopathy in type 2 diabetes. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2000;108:235–236. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-7748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowicki M, Ostalska-Nowicka D, Miskowiak B. Prognostic value of stage IV neuroblastoma metastatic immunophenotype in the bone marrow: preliminary report. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:150–152. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.024687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogasawara M, Murata J, Ayukawa K, Saimi I. Differential effect of intestinal neuropeptides on invasion and migration of colon carcinoma cells in vitro. Cancer Lett. 1997;116:111–116. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)00167-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman S, Langston J, Rao BN, Poquette CA, Jenkins JJ, Merchant T, Cain A, Pratt CB, Pappo AS. Brain metastases in pediatric Ewing sarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma: the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital experience. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1999;21:370–377. doi: 10.1097/00043426-199909000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellieux C, Sauthier T, Domenighetti A, Marsh DJ, Palmiter RD, Brunner HR, Pedrazzini T. Neuropeptide Y (NPY) potentiates phenylephrine-induced mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in primary cardiomyocytes via NPY Y5 receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:1595–1600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.030533197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pons J, Kitlinska J, Jacques D, Perreault C, Nader M, Everhart L, Zhang Y, Zukowska Z. Interactions of multiple signaling pathways in neuropeptide Y-mediated bimodal vascular smooth muscle cell growth. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;86:438–448. doi: 10.1139/y08-054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pons J, Kitlinska J, Ji H, Lee EW, Zukowska Z. Mitogenic actions of neuropeptide Y in vascular smooth muscle cells: synergetic interactions with the beta-adrenergic system. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;81:177–185. doi: 10.1139/y02-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rascher W, Kremens B, Wagner S, Feth F, Hunneman DH, Lang RE. Serial measurements of neuropeptide Y in plasma for monitoring neuroblastoma in children. J Pediatr. 1993;122:914–916. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(09)90018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasiah KK, Kench JG, Gardiner-Garden M, Biankin AV, Golovsky D, Brenner PC, Kooner R, O’Neill GF, Turner JJ, Delprado W, Lee CS, Brown DA, Breit SN, Grygiel JJ, Horvath LG, Stricker PD, Sutherland RL, Henshall SM. Aberrant neuropeptide Y and macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1 expression are early events in prostate cancer development and are associated with poor prognosis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:711–716. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reubi JC, Gugger M, Waser B, Schaer JC. Y(1)-mediated effect of neuropeptide Y in cancer: breast carcinomas as targets. Cancer research. 2001;61:4636–4641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscica M, Dozio E, Motta M, Magni P. Modulatory actions of neuropeptide Y on prostate cancer growth: role of MAP kinase/ERK 1/2 activation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;604:96–100. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-69116-9_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajdyk TJ, Vandergriff MG, Gehlert DR. Amygdalar neuropeptide Y Y1 receptors mediate the anxiolytic-like actions of neuropeptide Y in the social interaction test. European journal of pharmacology. 1999;368:143–147. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheriff S, Ali M, Yahya A, Haider KH, Balasubramaniam A, Amlal H. Neuropeptide Y Y5 receptor promotes cell growth through extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling and cyclic AMP inhibition in a human breast cancer cell line. Mol Cancer Res. 2010;8:604–614. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaper SD, Floreani M, Negro A, Facci L, Giusti P. Neurotrophins rescue cerebellar granule neurons from oxidative stress-mediated apoptotic death: selective involvement of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J Neurochem. 1998;70:1859–1868. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70051859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R, Owen LA, Trem DJ, Wong JS, Whangbo JS, Golub TR, Lessnick SL. Expression profiling of EWS/FLI identifies NKX2.2 as a critical target gene in Ewing’s sarcoma. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:405–416. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son MY, Kim MJ, Yu K, Koo DB, Cho YS. Involvement of neuropeptide Y and its Y1 and Y5 receptors in maintaining self-renewal and proliferation of human embryonic stem cells. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine. 2011;15:152–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00956.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staege MS, Hutter C, Neumann I, Foja S, Hattenhorst UE, Hansen G, Afar D, Burdach SE. DNA microarrays reveal relationship of Ewing family tumors to both endothelial and fetal neural crest-derived cells and define novel targets. Cancer research. 2004;64:8213–8221. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-4059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B, Zhang S, Zhao X, Zhang W, Hao X. Vasculogenic mimicry is associated with poor survival in patients with mesothelial sarcomas and alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas. Int J Oncol. 2004;25:1609–1614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorsell A, Heilig M. Diverse functions of neuropeptide Y revealed using genetically modified animals. Neuropeptides. 2002;36:182–193. doi: 10.1054/npep.2002.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilan J, Kitlinska J. Sympathetic neurotransmitters and tumor angiogenesis-link between stress and cancer progression. Journal of oncology. 2010;2010:539706. doi: 10.1155/2010/539706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilan J, Krailo M, Barkauskas D, Galli S, Mtaveh H, Long J, Wang H, Hawkins K, Lu C, Jeha D, Izycka-Swieszewska E, Lawlor ER, Toretsky J, Kitlinska J. Systemic levels of neuropeptide Y and dipeptidyl peptidase activity in Ewing sarcoma patients – associations with tumor phenotype and survival. Cancer. 2014a doi: 10.1002/cncr.29090. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilan JU, Everhart LM, Abe K, Kuo-Bonde L, Chalothorn D, Kitlinska J, Burnett MS, Epstein SE, Faber JE, Zukowska Z. Platelet neuropeptide Y is critical for ischemic revascularization in mice. FASEB J. 2013a doi: 10.1096/fj.12-213546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilan JU, Krailo M, Barkauskas DA, Galli S, Mtaweh H, Long J, Wang H, Hawkins K, Lu C, Jeha D, Izycka-Swieszewska E, Lawlor ER, Toretsky JA, Kitlinska JB. Systemic levels of neuropeptide Y and dipeptidyl peptidase activity in patients with Ewing sarcoma-associations with tumor phenotype and survival. Cancer. 2014b;121:697–707. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilan JU, Lu C, Galli S, Izycka-Swieszewska E, Earnest JP, Shabbir A, Everhart LM, Wang S, Martin S, Horton M, Mahajan A, Christian D, O’Neill A, Wang H, Zhuang T, Czarnecka M, Johnson MD, Toretsky JA, Kitlinska J. Hypoxia shifts activity of neuropeptide Y in Ewing sarcoma from growth-inhibitory to growth-promoting effects. Oncotarget. 2013b;4:2487–2501. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorova R. Ewing’s sarcoma cancer stem cell targeted therapy. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2014;9:46–62. doi: 10.2174/1574888x08666131203123125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toffoli S, Michiels C. Intermittent hypoxia is a key regulator of cancer cell and endothelial cell interplay in tumours. The FEBS journal. 2008;275:2991–3002. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey EC, Schiffman JD, Lessnick SL. Recent advances in the molecular pathogenesis of Ewing’s sarcoma. Oncogene. 2010;29:4504–4516. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda K, Tatsuguchi A, Saichi N, Toyama A, Tamura K, Furihata M, Takata R, Akamatsu S, Igarashi M, Nakayama M, Sato TA, Ogawa O, Fujioka T, Shuin T, Nakamura Y, Nakagawa H. Plasma low-molecular-weight proteome profiling identified neuropeptide-Y as a prostate cancer biomarker polypeptide. J Proteome Res. 2013;12:4497–4506. doi: 10.1021/pr400547s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Schaft DW, Hillen F, Pauwels P, Kirschmann DA, Castermans K, Egbrink MG, Tran MG, Sciot R, Hauben E, Hogendoorn PC, Delattre O, Maxwell PH, Hendrix MJ, Griffioen AW. Tumor cell plasticity in Ewing sarcoma, an alternative circulatory system stimulated by hypoxia. Cancer research. 2005;65:11520–11528. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Valen F, Winkelmann W, Jurgens H. Expression of functional Y1 receptors for neuropeptide Y in human Ewing’s sarcoma cell lines. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1992;118:529–536. doi: 10.1007/BF01225268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Levetzow C, Jiang X, Gwye Y, von Levetzow G, Hung L, Cooper A, Hsu JH, Lawlor ER. Modeling initiation of Ewing sarcoma in human neural crest cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19305. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]