Abstract

Yes-associated protein (YAP), the central mediator of Hippo pathway, not only regulates a diversity of cellular processes during development but also plays a pivotal role in tumorigenesis. YAP is overexpressed in many types of human cancers with its expression level being associated with patient outcomes. Thus, inhibiting YAP function could provide a novel therapeutic approach. Verteporfin, a photosensitizer, which has been used in photodynamic therapy (PDT), was recently identified as an inhibitor of the interaction of YAP with TEAD, which, in turn, blocks transcriptional activation of targets downstream of YAP. However, the mechanism by which Verteporfin inhibits YAP activity remains to be elucidated. We demonstrate that overexpression of YAP stimulates cell proliferation whereas knocking down YAP or treating cells with Verteporfin inhibited cell proliferation, even in the presence of growth factors. Protoporphyrin IX, another photosensitizer, did not have similar activity demonstrating specificity to Verteporfin. Verteporfin induced sequestration of YAP in cytoplasm through increasing levels of 14-3-3σ, a YAP chaperon protein that retains YAP in cytoplasm and targets it for degradation in the proteosome. Interestingly, while knockdown of YAP had no effect on the ability of Verteporfin to induce 14-3-3σ, p53 is required for this effect of Verteporfin. This provides potential approaches to select patients likely to benefit from Verteporfin.

Keywords: Verteporfin, YAP, 14-3-3σ, endometrial cancer

Introduction

The Yes-associated protein (YAP), a key downstream effector in the HIPPO signaling cascade, which was originally identified in Drosophila, has emerged as a major contributor to cancer pathophysiology [1-3]. Lats1/2 in the HIPPO pathway phosphorylates YAP leading to cytosolic sequestration of YAP and subsequent proteosome mediated degradation. Inactivation of HIPPO allows YAP to translocate to the nucleus where it acts as a transcriptional co-activator of the TEAD program, which increases the transcription of many oncogenes while inhibiting the expression of tumor suppressors. YAP has been proposed to function as an oncogene in most cancers, with nuclear localization of YAP correlating with poor prognosis [4]. Thus perturbation of YAP levels or functions could improve outcomes for cancer patients.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is an established cancer treatment using the interaction of a photosensitizer and light in an oxygenated environment [5]. Verteporfin is a second-generation photosensitizer approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2000 for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration [6]. Initial studies of focused on cell killing through photodynamic therapy [7,8]. However, Verteporfin has demonstrated activity independent of light-activation for example in inhibiting autophagosome and autophagy [9,10]. Recently verteporfin has been proposed to inhibit proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma cells and retinoblastoma cells through suppressing YAP activity [11,12]. In this study, we explore mechanisms by which Verteporfin regulates YAP function. The resulting data provides insight into potential approaches to use Verteporfin in the therapy of cancer patients.

Methods

Reagents and materials

Antibodies to YAP for WB, 14-3-3σ for WB, EGFR, Histone3, MEK1 were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology; 14-3-3σ for IF staining was from VWR International; YAP for IF staining, p53, Erk2, β-actin, γ-actin, α/β-tubulin from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. EGF (10 ng/ml) was from Sigma. ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool siRNA libraries were obtained from Dharmacon for human YAP1 (L-012200-00). YAP and YAPS127A plasmids were obtained from Dr. Ju-Seog Lee Lab (MD Anderson Cancer Center). X-tremeGENE HP DNA Transfection Reagent (06366236001) was from Roche Diagnostics. Lipofectamine® RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent was from Invitrogen (13778150). Verteporfin and Protoporphyrin IX were ordered from Sigma.

Cell culture and transient transfection

KLE, EFE184 and NOU-1 cell lines were obtained from the Characterized Cell Line Core Facility of the MD Anderson Cancer Center and routinely propagated as a monolayer culture with, respectively, DMEM F12, RPMI1640 and DMEM, all supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS). Cells were cultured at 37°C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2. HCT116 cells were from Dr. Bert Vogelstein (The Ludwig Center for Cancer Genetics and Therapeutics and Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center, Baltimore). MEF p53 wt and p53-/-cells were from Dr. Flores Lab (MD Anderson cancer center, Houston).

For siRNA knock down studies, cells were reverse transfected with siRNA with RNAiMAX reagent (Invitrogen) using 4-6*103 cells/well in a 96-well plate or 2*104 cells/well of a 6-well plate for the KLE and EFE184 cell lines, 8*103 cells/well in a 96-well plate or 3*105 cells/well in a 6-well plate for the NOU-1 cell line; For overexpression, 24 h after seeding cells, cells were transfected with plasmid and X-tremeGENE reagent using the manufacturer’s instructions.

Sulforhodamine B assay

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates and then treated as described. The inhibition effects on cell growth were determined using sulforhodamine B (SRB) as described previously [13-15]. Adherent cells were fixed with cold (4°C) 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) in a 96-well microplate for 1 h at 4°C and then washed with deionized water and air dried at room temperature. Next, 0.4% (w/v) SRB in 1% acetic acid solution was added into each well and incubated at room temperature for 30 min; then the cells were washed with 1% acetic acid and air dried at room temperature. Bound SRB was solubilized with 100-200 μl of 10 mM unbuffered Tris-base solution (pH 10.5). Absorbance was read at 540-560 nm without reference wavelength. Each experiment was performed at least three times in triplicate determinations.

Western blots

Cells were washed twice in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then lysed in RIPA Lysis Buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The resulting suspension was centrifuged for 10 min, 14,000 rpm at 4°C. The supernatant was then collected, and the protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific). Cell lysates were incubated with 6× SDS sample buffer for 5 min at 100°C and then were run on SDS-PAGE gels, transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes, and probed with the appropriate primary and secondary antibodies. Protein bands were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, GE Healthcare).

Immunofluoresence microscopy

Cells were fixed for 10 min in 4% paraformaldehyde. The fixed cells were permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 2 min on ice. After blocking for 1 h at room temperature with 1% bovine serum albumin, the cells were stained using primary antibodies (1:1000), 4°C, overnight as indicated. After washing three times with PBS, cells were incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies (1:2500) at room temperature for 1 h. After washing three times with PBS, the slides were mounted with antifade reagent with DAPI.

Reverse phase protein array

Cells were washed twice in ice-cold PBS and then lysed in reverse phase protein array (RPPA) lysis buffer (provided by CCSG supported RPPA core facility of MD Anderson cancer center) for 30 min with frequent vortexing on ice. The resulting suspension was centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 rpm. The supernatant was then collected and the protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific). Protein concentration was adjusted to 1 mg/mL using lysis buffer. Cell lysates were incubated with 4× SDS sample buffer for 5 min at 100°C, and then samples were sent to the RPPA core facility of the MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Results

YAP1 is overexpressed in women cancers and promotes cell proliferation

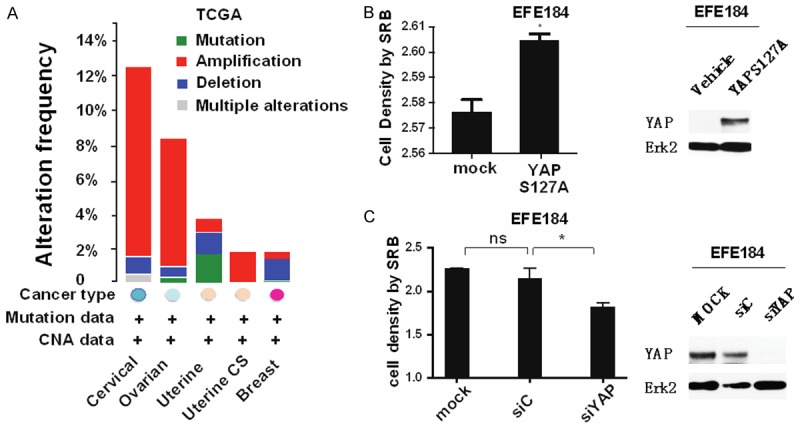

Using the cancer genome atlas data (http://www.cbioportal.org) for patients with “women’s cancer” (breast, cervix, ovarian and uterine cancer) on the CBio website, we found YAP1 gene was amplified in a portion of patients of each of these disease (Figure 1A). Similar data was present across all cancer in the TCGA as well as in our own endometrial cancer studies (data not shown). High grade and late stage of endometrial cancer was associated with elevated YAP1 levels compared with the low grade and early stage, while the low grade and early stage had a higher p-YAPS127. P-YAPS127 is retained in the cytoplasm preventing association of YAP1 with TEAD in the nucleus and thus abrogating expression of downstream TEAD targets. Thus YAP1 is implicated in the pathophysiology of women cancers. In support of this contention, increasing or decreasing YAP levels in cell lines, enhanced or decreased cell proliferation, respectively (Figure 1B and 1C).

Figure 1.

YAP1 is overexpressed in women’s cancers and nuclear-localized YAP promotes cell proliferation. A. YAP1 protein expression level in women cancers including ovarian, cervix, endometrial and breast cancer, and uterine carcinoma sarcoma, Data from CBio website. YAP is amplified in a subset of these cancers. B. In EFE184 cells, overexpression of YAPS127A, the nuclear-localized, constitutively active mutant of YAP1, enhances cell proliferation (Left panel). Right panel is Western blot of YAPS127A protein expression. At 48 h after transfection, cells in the 96-well plate were processed for SRB assay to measure cell proliferation while cells in the 6-well plate were collected for western blotting with the indicated antibodies. Erk2 was used as a loading control. C. Knocking down of YAP attenuates cell proliferation. EFE184 cells were transfected with siYAP and siControl. At 48 h after transfection, cells were collected for SRB assay and Western blot. Conclusion: Nuclear YAP promotes cell proliferation.

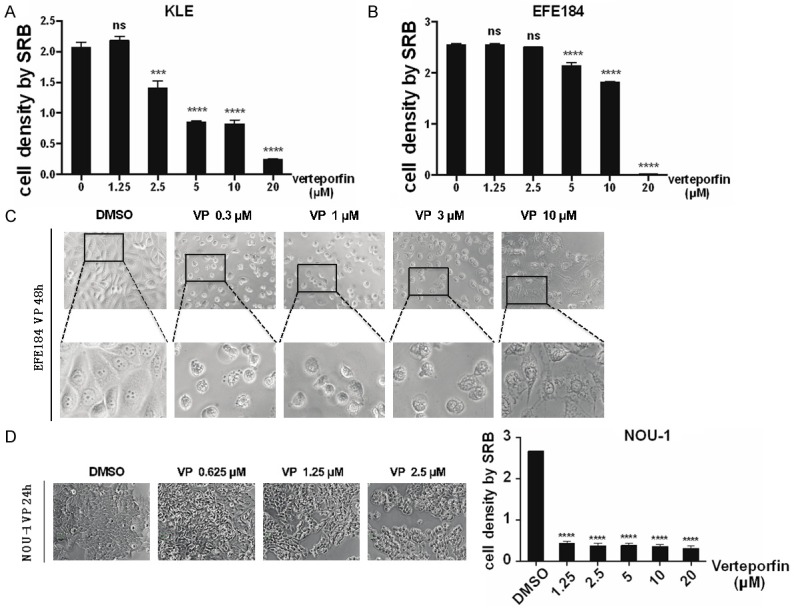

Verteporfin inhibits cell proliferation

Verteporfin treatment of KLE cells and EFE184 cells, induced a dose and time dependent decrease of cell proliferation (Figure 2A, 2B). Prolonged incubation with Verteporfin induced cell death with the vacuolization in cells (Figure 2C). Compared with KLE and EFE184 cells, NOU-1 cells were more sensitive (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Verteporfin inhibits cell proliferation. A. Cell proliferation is inhibited by Verteporfin in a dose dependent manner. KLE cells were treated with Verteporfin (VP) at 0.1 μM, 0.3 μM, 1 μM, 3 μM, 10 μM. 24 h after treatment, cell viability was measured by SRB. Statistical significance was calculated using two way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, ****P<0.0001, ***P<0.001, **P<0.01, *P<0.5, ns means non-significant. Error bars represent Mean ± SD of triplicates. B. EFE184 were treated the same as for KLE. Cell viability was measured by SRB. C. KLE and EFE184 cells were treated with Verteporfin of 0.3 μM, 1 μM, 3 μM, 10 μM. 24 h after treatment, cells were observed under the microscope and imaged. Top panel, morphological change of EFE184 cells. Bottom panel, enlargements of the pictures. D. NOU-1 cells were treated with Verteporfin of 0.625 μM, 1.25 μM, 2.5 μM. At 24 h after treatment, cells were observed under the microscope and imaged. At the same time, cells were collected for SRB assay. Statistical significance was calculated using the same way with that in A. DMSO was used as vehicle control. Conclusion: Verteporfin inhibits proliferation of multiple endometrial cell lines.

Verteporfin but not Protoporphyrin IX decreases YAP levels

We selected Protoporphyrin IX (PPIX), another derivation of porphyrin, to see whether all photosensitizers have a similar effect with that of Verteporfin. 3 μM Verteporfin for 20 h caused the vacuolation of cells and inhibited cell proliferation. The decrease in proliferation was associated with cell death as assessed with a LIVE/DEAD kit, (data not shown). In contrast, Protoporphyrin IX did exhibit similar effects of cell proliferation, morphology and death (Figure 3A). As assessed by western blotting, Verteporfin, but not Protoporphyrin IX, induced a dose and time dependent increase in YAP levels (Figure 3B). Low concentrations were able to completely abrogate YAP expression at delayed times as were high doses of Verteporfin (10 µM) at short time (1 hr) (data not shown). Thus the ability of Verteporfin, but not Protoporphyrin IX to induce dose and time dependent decreases in cell proliferation is associated with an ability to decrease YAP levels.

Figure 3.

Verteporfin decreases YAP levels. A. EFE184 cells were treated with Verteporfin and Protoporphyrin IX (PPIX) at 0.1 μM, 0.3 μM, 1 μM, 3 μM, 10 μM. At 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, or 96 h after treatment, cells were collected for SRB assay to determine cell proliferation. Cells at 20 h after treatment were also observed under the microscope and imaged. The left panel shows morphology. B. EFE184 cells and NOU-1 cells were treated with Verteporfin and Protoporphyrin IX. At 24 h after treatment, cell lysates were subjected to western blotting with the indicated antibodies. Erk2 and α/β tubulin were used as a loading control. Conclusion: Verteporfin but not Protoporphyrin IX decreases YAP expression.

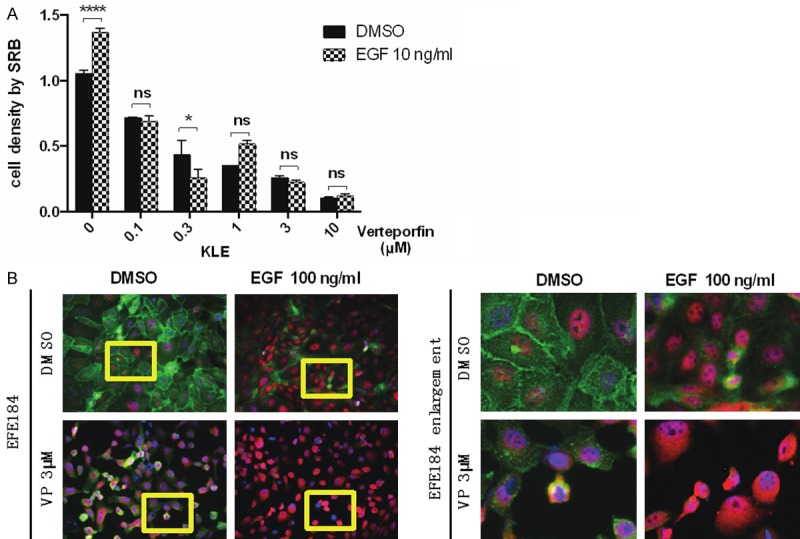

Nuclear localization of YAP

YAP must translocate to the mediate the TEAD transcription program. Translocation of YAP to the nucleus can be induced by growth factors such as EGF. Consistent with the effects of Verteporfin on YAP levels, Verteporfin inhibited EGF-induced proliferation (Figure 4A). In contrast, the HIPPO pathway activation increases LATS kinase activity, which leads to phosphorylation of YAP and its sequestration in the cytoplasm through binding to 14-3-3σ [1]. In endometrial cells, the majority of YAP was localized to the nucleus which was further increased by EGF treatment (Figure 4B). Concurrently EGF decreased cell surface EGFR levels likely due to internalization and degradation. Strikingly, Verteporfin decreased both basal and EGF-induced YAP nuclear localization resulting in increases in cytosolic YAP. However, Verteporfin did not reverse the effects of EGR on EGFR levels indicating that its action was downstream of EGFR activation and internalization (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Verteporfin affects YAP location. A. KLE cells and NOU-1 cells (data not shown) were treated with Verteporfin at 0.1 μM, 0.3 μM, 1 μM, 3 μM, 10 μM. 24 h after treatment, Verteporfin was removed and cells were treated with EGF (10 ng/ml) for 48 h. Cell proliferation was measured by SRB. Statistical significance was calculated using two way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, ****P<0.0001, ***P<0.001, **P<0.01, *P<0.5, ns means non-significant. Error bars represent Mean ± SD of triplicates. B. EFE184 cells were treated with Verteporfin (3 μM) and EGF (10 ng/ml) simultaneously for 48 h. The cellular location of YAP was determined by immunofluorescence staining. The green color refers to EGFR, while the red color refers to YAP. The pictures at the right side are the enlargement of yellow frames in pictures at the left side. Conclusion: Verteporfin sequesters YAP in the cytosol.

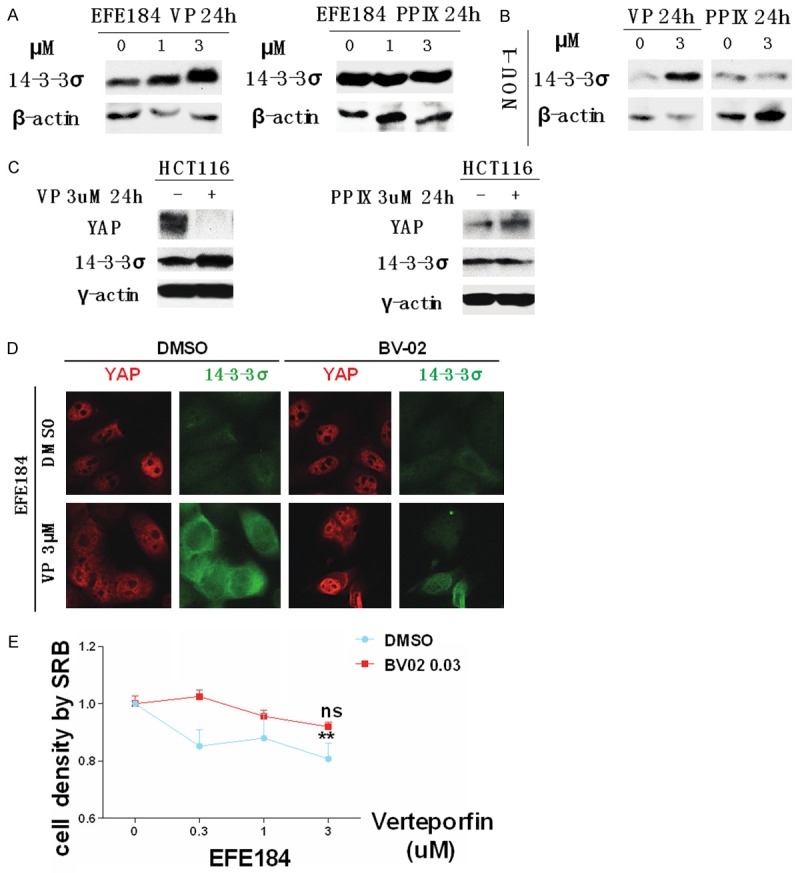

Verteporfin increases 14-3-3σ levels, which promotes the translocation of YAP from nuclear to cytoplasm

Phosphorylated YAP associates with cytoplasmic 14-3-3σ [1], thus, we investigated the effects of Verteporfin on 14-3-3σ levels. Western blotting showed that Verteporfin but not Protoporphyrin IX, increases 14-3-3σ in multiple cell lines including EFE184 NOU-1 and HCT116 (colon cancer line) (Figure 5A-C). Immunofluorescence indicated that Verteporfin increased 14-3-3σ primarily in the cytoplasm similar to the effects of Verteporfin on YAP. Strikingly, the BV-02 nonpeptidic inhibitor of 14-3-3σ [16], antagonized the effects of Verteporfin resulting in and increase of nuclear YAP (Figure 5D). As indicated in Figure 5E, BV-02 markedly increases nuclear YAP levels in both basal conditions and in Verteporfin treated cells.

Figure 5.

Verteporfin increases the level of 14-3-3σ, which promotes the translocation of YAP from nucleus to cytoplasm. A. EFE184 cells were treated with 1 μM and 3 μM Verteporfin and Protoporphyrin IX for 24 h. Cells were collected for western blotting with the indicated antibodies. β-actin was used as a loading control. B. NOU-1 cells were treated with 3 μM of Verteporfin and Protoporphyrin IX for 24 h. Western blotting was performed with the indicated antibodies. β-actin was used as a loading control. C. HCT116 cells were treated in same way with that in EFE184 and NOU-1. In all cells tested, 14-3-3σ was increased by Verteporfin but not by Protoporphyrin IX. D. EFE184 cells were treated with 3 μM of Verteporfin and 1 μM of 14-3-3σ inhibitor BV-02. 24 h after treatment, cells were processed to immunofluorescence staining to observe the location of 14-3-3σ and YAP. The green color represents 14-3-3σ; the red color represents YAP. E. EFE184 cells were treated with Verteporfin with or without BV-02 for 24 h. 0.03 μM BV-02 antagonized the effects of Verteporfin. Cell proliferation was measured by SRB. Statistical significance was calculated by two way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, ****P<0.0001, ***P<0.001, **P<0.01, P<0.5, ns means non-significant. Error bars represent Mean ± SD of triplicates. “ns” refers to the comparison between 0 μM verteporfin and 3 μM verteporfin + 0.03 μM BV-02. “**” refers to the comparison between 0 μM verteporfin and 3 μM verteporfin. Conclusion: Verteporfin increases 14-3-3σ which sequesters YAP in the cytosol.

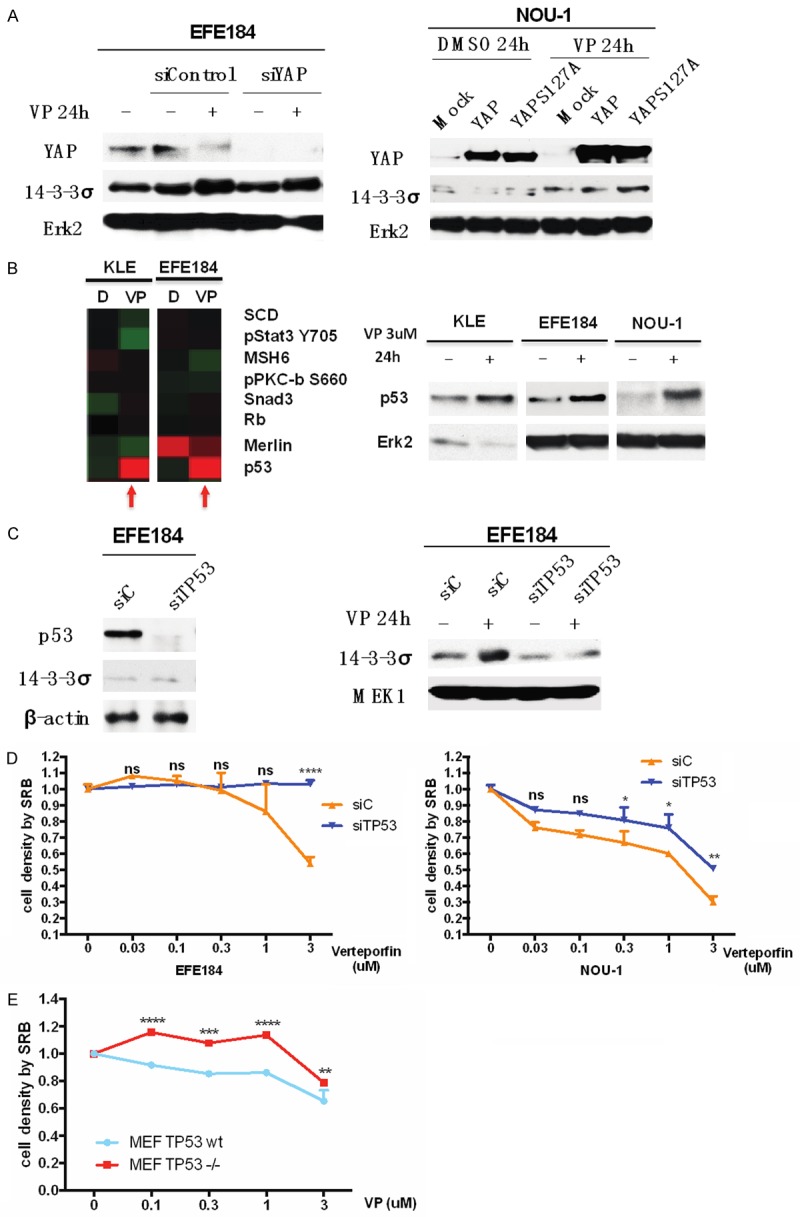

The increase of 14-3-3σ induced by verteporfin requires the interference of p53

To determine whether YAP regulated 14-3-3σ, we decreased and increased YAP levels and found that altering YAP levels did not alter the effects of Verteporfin on 14-3-3σ (Figure 6A). Since 14-3-3σ could be regulated by p53 (ref please), and RPPA and western blotting data showing that Verteporfin (Figure 6B), we determine whether p53 is necessary for Verteporfin to regulate 14-3-3σ. Intriguingly, knock down of TP53, attenuated the ability of Verteporfin to increase 14-3-3σ, and decreased the effects of Verteporfin on cell proliferation (Figure 6C, 6D). Consistent with TP53 being required for the effects of Verteporfin on cell proliferation, the effects of Verteporfin were attenuated in TP53 null murine embryo fibroblasts (Figure 6E). It is important to note that Nou-1 endometrial cancer cell lines studied above are TP53 wild type.

Figure 6.

The increase of 14-3-3σ level induced by verteporfin is p53-dependent. A. EFE184 cells and NOU-1 cells were transfected with siYAP and siControl constructs. At 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with 3 μM of Verteporfin. Western blotting was employed with the indicated antibodies. Erk2 was used as a loading control. In the absence of YAP, Verteporfin still increases 14-3-3σ. B. KLE cells and EFE184 cells were treated with 3 μM of Verteporfin for 24 h. Cells were subjected to a RPPA assay. The graph at the left side is a screenshot of heatmap of RPPA data. At the same time, KLE, EFE184 and NOU-1 were treated in same way and then were processed to western blotting with the indicated antibodies. Erk2 was used as a loading control. Verteporfin increases p53 levels. C. EFE184 cells were transfected with siTP53 and siControl constructs, and 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with or without 3 μM Verteporfin for 24 h. Cells were subjected to western blotting with the indicated antibodies. β-actin and MEK1 were used as a loading control. P53 is required for Verteporfin to increase 14-3-3σ. D. EFE184 and NOU-1 were treated in same way with in C. Cell proliferation was determined by SRB assay. Two way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (between siTP53 and siControl) were used, ****P<0.0001, **P<0.01, *P<0.5, ns means non-significant. Error bars represent Mean ± SD of triplicates. E. TP53-wt and TP53-null MEF cells were treated with Verteporfin in a dose series from 0.03 μM to 3 μM for 24 h. Cell proliferation was determined by SRB assay. Two way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (between MEF TP53 wt and MEF TP53 null) were used, ****P<0.0001, ***P<0.001, **P<0.01, ns means non-significant. Error bars represent Mean ± SD of triplicates. Conclusion: TP53 is required for optimal effects of Verteporfin on 14-3-3σ and cell proliferation.

Discussion

Although YAP also has been implicated as a tumor suppressor under particular circumstances including in breast cancer [17], in most cases, YAP has been proposed to function as oncogenes, with nuclear localization of YAP/TAZ correlating with poor prognosis [4]. The potential action of YAP as a tumor suppressor may be independent of its transcriptional co-activator function with YAP acting as a scaffolding protein in the cytosol [18-22]. Recent literature reported YAP overexpression is not only an early event in rat and human liver tumorigenesis but also a critical event in the clonal expansion of carcinogen-initiated hepatocytes and oval cells, and the disruption of YAP-TEAD interaction induced by Verteporfin may provide an important approach for the treatment of YAP-overexpressing cancers [23]. Nuclear YAP expression was associated with poor outcome in urothelial cell carcinoma patients who received perioperative chemotherapy. Verteporfin inhibiting YAP function inhibited tumor cell proliferation and restored sensitivity to cisplatin [24]. Thus inhibition of YAP levels or function with Verteporfin warrants exploration as a therapeutic approach particularly in cancer with wild type TP53 where the effects of Verteporfin are most clearly manifest. Our studies with endometrial cells lines, the association of YAP levels with clinical characteristics in endometrial cancer and the observation that TP53 is wild type in most type 1 endometrial cancers, suggest that Verteporfin may be effective in this disease.

Verteporfin has been used to treat patients as a photosensitizer with limited toxicity. Recent evidence that Verteporfin can alter functions associated with tumor pathophysiology including autophagy and inhibition of YAP function independent of its action as a photosensitizer support its evaluation as a cancer therapeutic [9-11]. We demonstrated that Verteporfin decreases nuclear YAP levels and function as a consequence of increasing cytosolic 14-3-3σ and trapping YAP in the cytosol. Our RPPA data indicates that Verteporfin also increases 14-3-3ζ and 14-3-3ε levels suggesting that multiple 14-3-3 family members might contribute to trapping YAP in the cytosol.

14-3-3 is a highly conserved family of 28- to 33-kDa acidic proteins consisting of seven members (β, γ, ε, ζ, η, σ, and τ (also named θ)). They regulate many critical events such as autophagy [25], apoptosis [26], cell cycle progression [27], DNA damage response [28], cytoskeletal rearrangements [29], and transcriptional regulation [30] (refs please). As 14-3-3 proteins regulate autophagy, this raises the intriguing possibility that the effects of Verteporfin on autophagy may be secondary to effects of Verteporfin on inducing 14-3-3 family members. The major activity of 14-3-3 proteins is thought to be the sequestration of phosphorylated proteins in the cytosol with subsequent targeting for degradation in the proteasome. The different 14-3-3 proteins sequester unique sets of targets. For example, 14-3-3σ is the key family member retaining c-Abl in the cytoplasm [31]. Thus targeting 14-3-3σ has been regarded as a therapeutic option in CML [32]. Mancini et al. identified a nonpeptidic inhibitor of 14-3-3σ, BV02, which released c-Abl from 14-3-3σ increasing the proapoptotic function of c-Abl [16]. In addition, 14-3-3β binds histone deacetylase 4 (HDAC4) and HDAC5 [33,34], 14-3-3θ binds Bad [35] and Bcl2-associated X protein (Bax) [36], and 14-3-3ζ binds apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (Ask1) [37] and Forkhead-Related Family of Mammalian Transcription Factor-1 (Fkhrl1) [38]. Thus 14-3-3 family proteins sequester multiple key oncogenic regulators.

TAZ (a homolog of YAP) as well as YAP sequestered in the cytosol by 14-3-3 decreasing its transcriptional co-activation function [39]. Phosphorylation of Ser89 in the RSHSSP motive which is equivalent to, RAHSSP in YAP is a consensus 14-3-3 binding motive [40]. In addition to LATS in the HIPPO pathway other kinases such as AKT can phosphorylate YAP with for example AKT [41].

The induction of 14-3-3σ by DNA damage is dependent on TP53 and ectopic expression of p53 induces 14-3-3σ and conversely, 14-3-3σ contributes to further activation of p53 in a feed forward loop [42]. Interesting Verteporfin increased p53 levels and further p53 was required for the effects of Verteporfin on 14-3-3σ and cell proliferation. Thus the effects of Verteporfin may be most clearly manifest in cells with wild type p53.

Taken together our studies suggest that repurposing Verteporfin as a cancer therapeutic may demonstrate monotherapy or more likely combination therapy activity in in tumors where YAP signaling is critical to tumor pathophysiology and in particular in tumors where p53 is wild type. Type 1 endometrial cancer is an obvious candidate for the therapeutic evaluation of Verteporfin.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Shanghai Outstanding Youth Training Plan of China (grant no. XYQ2011062) which provided support for Chao Wang and NCI grants P30CA016672, U01CA168394, P50CA098258 to GBM.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Zhao B, Wei X, Li W, Udan RS, Yang Q, Kim J, Xie J, Ikenoue T, Yu J, Li L, Zheng P, Ye K, Chinnaiyan A, Halder G, Lai ZC, Guan KL. Inactivation of YAP oncoprotein by the Hippo pathway is involved in cell contact inhibition and tissue growth control. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2747–2761. doi: 10.1101/gad.1602907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oh H, Irvine KD. Yorkie: the final destination of Hippo signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:410–417. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pan D. The hippo signaling pathway in development and cancer. Dev Cell. 2010;19:491–505. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao B, Li L, Lei Q, Guan KL. The Hippo-YAP pathway in organ size control and tumorigenesis: an updated version. Genes Dev. 2010;24:862–874. doi: 10.1101/gad.1909210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dougherty TJ, Gomer CJ, Henderson BW, Jori G, Kessel D, Korbelik M, Moan J, Peng Q. Photodynamic therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:889–905. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.12.889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henney JE. From the Food and Drug Administration. JAMA. 2000;283:2779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pogue BW, O’Hara JA, Demidenko E, Wilmot CM, Goodwin IA, Chen B, Swartz HM, Hasan T. Photodynamic therapy with verteporfin in the radiation-induced fibrosarcoma-1 tumor causes enhanced radiation sensitivity. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1025–1033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt-Erfurth U, Hasan T. Mechanisms of action of photodynamic therapy with verteporfin for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration. Surv Ophthalmol. 2000;45:195–214. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(00)00158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donohue E, Tovey A, Vogl AW, Arns S, Sternberg E, Young RN, Roberge M. Inhibition of autophagosome formation by the benzoporphyrin derivative verteporfin. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:7290–7300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.139915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donohue E, Thomas A, Maurer N, Manisali I, Zeisser-Labouebe M, Zisman N, Anderson HJ, Ng SS, Webb M, Bally M, Roberge M. The autophagy inhibitor verteporfin moderately enhances the antitumor activity of gemcitabine in a pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma model. J Cancer. 2013;4:585–596. doi: 10.7150/jca.7030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu-Chittenden Y, Huang B, Shim JS, Chen Q, Lee SJ, Anders RA, Liu JO, Pan D. Genetic and pharmacological disruption of the TEADYAP complex suppresses the oncogenic activity of YAP. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1300–1305. doi: 10.1101/gad.192856.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brodowska K, Al-Moujahed A, Marmalidou A, Meyer Zu Horste M, Cichy J, Miller JW, Gragoudas E, Vavvas DG. The clinically used photosensitizer Verteporfin (VP) inhibits YAP-TEAD and human retinoblastoma cell growth in vitro without light activation. Exp Eye Res. 2014;124:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papazisis KT, Geromichalos GD, Dimitriadis KA, Kortsaris AH. Optimization of the sulforhodamine B colorimetric assay. J Immunol Methods. 1997;208:151–158. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(97)00137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vichai V, Kirtikara K. Sulforhodamine B colorimetric assay for cytotoxicity screening. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1112–1116. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rubinstein LV, Shoemaker RH, Paull KD, Simon RM, Tosini S, Skehan P, Scudiero DA, Monks A, Boyd MR. Comparison of in vitro anticancer-drug-screening data generated with a tetrazolium assay versus a protein assay against a diverse panel of human tumor cell lines. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990;82:1113–1118. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.13.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mancini M, Corradi V, Petta S, Barbieri E, Manetti F, Botta M, Santucci MA. A new nonpeptidic inhibitor of 14-3-3 induces apoptotic cell death in chronic myeloid leukemia sensitive or resistant to imatinib. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;336:596–604. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.172536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yuan M, Tomlinson V, Lara R, Holliday D, Chelala C, Harada T, Gangeswaran R, Manson-Bishop C, Smith P, Danovi SA, Pardo O, Crook T, Mein CA, Lemoine NR, Jones LJ, Basu S. Yes-associated protein (YAP) functions as a tumor suppressor in breast. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:1752–1759. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Azzolin L, Panciera T, Soligo S, Enzo E, Bicciato S, Dupont S, Bresolin S, Frasson C, Basso G, Guzzardo V, Fassina A, Cordenonsi M, Piccolo S. YAP/TAZ incorporation in the betacatenin destruction complex orchestrates the Wnt response. Cell. 2014;158:157–170. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Azzolin L, Zanconato F, Bresolin S, Forcato M, Basso G, Bicciato S, Cordenonsi M, Piccolo S. Role of TAZ as mediator of Wnt signaling. Cell. 2012;151:1443–1456. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenbluh J, Nijhawan D, Cox AG, Li X, Neal JT, Schafer EJ, Zack TI, Wang X, Tsherniak A, Schinzel AC, Shao DD, Schumacher SE, Weir BA, Vazquez F, Cowley GS, Root DE, Mesirov JP, Beroukhim R, Kuo CJ, Goessling W, Hahn WC. beta-Catenin-driven cancers require a YAP1 transcriptional complex for survival and tumorigenesis. Cell. 2012;151:1457–1473. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barry ER, Morikawa T, Butler BL, Shrestha K, de la Rosa R, Yan KS, Fuchs CS, Magness ST, Smits R, Ogino S, Kuo CJ, Camargo FD. Restriction of intestinal stem cell expansion and the regenerative response by YAP. Nature. 2013;493:106–110. doi: 10.1038/nature11693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levy D, Adamovich Y, Reuven N, Shaul Y. The Yes-associated protein 1 stabilizes p73 by preventing Itch-mediated ubiquitination of p73. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:743–751. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perra A, Kowalik MA, Ghiso E, Ledda-Columbano GM, Di Tommaso L, Angioni MM, Raschioni C, Testore E, Roncalli M, Giordano S, Columbano A. YAP activation is an early event and a potential therapeutic target in liver cancer development. J Hepatol. 2014;61:1088–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ciamporcero E, Shen H, Ramakrishnan S, Yu Ku S, Chintala S, Shen L, Adelaiye R, Miles KM, Ullio C, Pizzimenti S, Daga M, Azabdaftari G, Attwood K, Johnson C, Zhang J, Barrera G, Pili R. YAP activation protects urothelial cell carcinoma from treatment-induced DNA damage. Oncogene. 2015 doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.219. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pozuelo-Rubio M. Regulation of autophagic activity by 14-3-3zeta proteins associated with class III phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:479–492. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenquist M. 14-3-3 proteins in apoptosis. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2003;36:403–408. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2003000400001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gardino AK, Yaffe MB. 14-3-3 proteins as signaling integration points for cell cycle control and apoptosis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2011;22:688–695. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aristizabal-Corrales D, Fontrodona L, Porta-dela-Riva M, Guerra-Moreno A, Ceron J, Schwartz S Jr. The 14-3-3 gene par-5 is required for germline development and DNA damage response in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:1716–1726. doi: 10.1242/jcs.094896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Angrand PO, Segura I, Volkel P, Ghidelli S, Terry R, Brajenovic M, Vintersten K, Klein R, Superti-Furga G, Drewes G, Kuster B, Bouwmeester T, Acker-Palmer A. Transgenic mouse proteomics identifies new 14-3-3-associated proteins involved in cytoskeletal rearrangements and cell signaling. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:2211–2227. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600147-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carrasco JL, Castello MJ, Vera P. 14-3-3 mediates transcriptional regulation by modulating nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of tobacco DNA-binding protein phosphatase-1. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:22875–22881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512611200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mancini M, Veljkovic N, Corradi V, Zuffa E, Corrado P, Pagnotta E, Martinelli G, Barbieri E, Santucci MA. 14-3-3 ligand prevents nuclear import of c-ABL protein in chronic myeloid leukemia. Traffic. 2009;10:637–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dong S, Kang S, Lonial S, Khoury HJ, Viallet J, Chen J. Targeting 14-3-3 sensitizes native and mutant BCR-ABL to inhibition with U0126, rapamycin and Bcl-2 inhibitor GX15-070. Leukemia. 2008;22:572–577. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ellis JJ, Valencia TG, Zeng H, Roberts LD, Deaton RA, Grant SR. CaM kinase IIdeltaC phosphorylation of 14-3-3beta in vascular smooth muscle cells: activation of class II HDAC repression. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;242:153–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grozinger CM, Schreiber SL. Regulation of histone deacetylase 4 and 5 and transcriptional activity by 14-3-3-dependent cellular localization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:7835–7840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.140199597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zha J, Harada H, Yang E, Jockel J, Korsmeyer SJ. Serine phosphorylation of death agonist BAD in response to survival factor results in binding to 14-3-3 not BCL-X(L) Cell. 1996;87:619–628. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nomura M, Shimizu S, Sugiyama T, Narita M, Ito T, Matsuda H, Tsujimoto Y. 14-3-3 Interacts directly with and negatively regulates proapoptotic Bax. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:2058–2065. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207880200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang L, Chen J, Fu H. Suppression of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1-induced cell death by 14-3-3 proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:8511–8515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brunet A, Bonni A, Zigmond MJ, Lin MZ, Juo P, Hu LS, Anderson MJ, Arden KC, Blenis J, Greenberg ME. Akt promotes cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting a Forkhead transcription factor. Cell. 1999;96:857–868. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kanai F, Marignani PA, Sarbassova D, Yagi R, Hall RA, Donowitz M, Hisaminato A, Fujiwara T, Ito Y, Cantley LC, Yaffe MB. TAZ: a novel transcriptional co-activator regulated by interactions with 14-3-3 and PDZ domain proteins. EMBO J. 2000;19:6778–6791. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.24.6778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yaffe MB, Rittinger K, Volinia S, Caron PR, Aitken A, Leffers H, Gamblin SJ, Smerdon SJ, Cantley LC. The structural basis for 14-3-3: phosphopeptide binding specificity. Cell. 1997;91:961–971. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80487-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Basu S, Totty NF, Irwin MS, Sudol M, Downward J. Akt phosphorylates the Yes-associated protein, YAP, to induce interaction with 14-3-3 and attenuation of p73-mediated apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2003;11:11–23. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00776-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hermeking H, Lengauer C, Polyak K, He TC, Zhang L, Thiagalingam S, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. 14-3-3 sigma is a p53-regulated inhibitor of G2/M progression. Mol Cell. 1997;1:3–11. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]