Abstract

Linking marine epizootics to a specific aetiology is notoriously difficult. Recent diagnostic successes show that marine disease diagnosis requires both modern, cutting-edge technology (e.g. metagenomics, quantitative real-time PCR) and more classic methods (e.g. transect surveys, histopathology and cell culture). Here, we discuss how this combination of traditional and modern approaches is necessary for rapid and accurate identification of marine diseases, and emphasize how sole reliance on any one technology or technique may lead disease investigations astray. We present diagnostic approaches at different scales, from the macro (environment, community, population and organismal scales) to the micro (tissue, organ, cell and genomic scales). We use disease case studies from a broad range of taxa to illustrate diagnostic successes from combining traditional and modern diagnostic methods. Finally, we recognize the need for increased capacity of centralized databases, networks, data repositories and contingency plans for diagnosis and management of marine disease.

Keywords: marine disease, aetiology, diagnostics, marine epizootics

1. Introduction

Marine diseases may have important ecological, economic, conservation and human health impacts [1–4]. An increase in the reported frequency and severity of marine diseases [5,6] demands that complementary tools and approaches be used for rapid and effective diagnosis. Such tools are also critical to establish the essential baseline data (box 1) necessary for comparative investigations of marine epizootics [6,16,17]. Technologic approaches have recently advanced by leaps and bounds, providing exciting new diagnostic tools such as high-throughput sequencing, -omics (e.g. genomics, proteomics and metabolomics), optics, analytical chemistry and molecular biology. However, to fully understand the disease process and to place it within an ecological context, results from these novel methods must be interpreted alongside data collected by more classic or traditional means such as gross observation of lesions, transect surveys, microscopic observation of cellular changes, disease transmission assays in experimental conditions, histopathology and microbiology [18,19]. An effective approach for disease diagnosis and identification also requires examination of the problem at multiple levels of biological complexity (figure 2), starting with an environmental assessment and continuing to the genome level. In an effort to improve research and mitigate future disease events, we outline a series of approaches to effectively and comprehensively evaluate marine epizootics, and provide case studies to emphasize the utility and context of different approaches.

Figure 2.

Disease diagnosis concentric ring. The many layers of disease diagnoses include the environment, population/community, organism, cell and gene. Photos by Morgan Eisenlord (environment), Drew Harvell (population/community), and Gary Cherr/Nature McGinn (cell/tissue).

(a). Past and current marine disease diagnoses: lessons from mass mortalities of echinoderms

In January 1983, a mass die-off of the Caribbean sea urchin (Diadema antillarum) started in Panama and swept through the Caribbean, causing 85–100% mortality in local populations [20–22]. This massive decline contributed to a phase shift from corals to macroalgae-dominated reefs [22–24] and, until recently, this epizootic was unparalleled in the immediate and cascading destruction it caused to a marine ecosystem. Even now, 30 years later, D. antillarum populations and the reefs that depend on them have yet to recover [25,26], and Caribbean coral reef ecosystems are in continuous decline due to synergisms with stressors including overfishing, hurricanes, declines in water quality, thermal stress and disease [3,5].

Published records of the D. antillarum mass mortality included photographs and descriptions of gross lesions, and some local environmental data, host behavioural changes and host population densities [21,27,28]. The disease was not correlated with temperature or salinity, and other urchin species stayed healthy, suggesting a host-specific pathogen or condition as the culprit [20]. The rapid spread also suggested a water-borne agent [28], with a possible source in ballast waters transported from the Pacific Ocean to the Caribbean Sea by ships traversing the Panama Canal [20]. Because the scientific community failed to diagnose the disease at the time and did not properly preserve samples for later analysis, the pathogen and environmental circumstances that transformed Caribbean coral reef communities were never determined.

Three decades after the Diadema die-off, a massive marine disease event occurred in the northeast Pacific ocean and now rocky intertidal populations along the west coast of the USA are at the precipice of a transformation similar to that observed in the Caribbean coral reefs. Beginning in June 2013, a disease known as ‘sea star wasting disease’ (SSWD) caused mass mortality in 20 sea star species [29]. The number of host species affected, geographical range, time scale and associated death is unprecedented [30–32]. Cascading large-scale ecological impacts may occur as a consequence of this event. For example, the loss of ochre (Pisaster ochraceus) and sunflower (Pycnopodia helianthoides) sea stars could lead to massive shifts in the intertidal and subtidal communities [24,33].

In contrast to the Caribbean urchin die-off, the response to the SSWD event was rapid and coordinated. Supported by emergency funding, scientists identified a potential causative agent and its ecological context using classic (gross examination, microbiology, histopathology and transmission electron microscopy (TEM)) and modern (high-throughput sequencing metagenomics and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)) diagnostic techniques, coupled with transmission experiments to identify a virus associated with SSWD [29]. Also, citizen scientists used social media to document baseline conditions and disease spread (C. M. Miner 2015, personal communication (to C.A.B.)). The SSWD event exemplifies how scientists can proactively evaluate an ongoing disease event, at multiple scales of biological complexity, using a union of modern and classic methods.

2. Systems-based and iterative approach to disease diagnosis

(a). Environment

Changing environmental factors can have major effects on disease [3]. This is especially true for the marine environment in which host health is intimately tied to the quality and characteristics of their aquatic habitat. Shifts in water temperature or salinity can lead to thermal or osmotic stress; low dissolved oxygen can lead to catastrophic die-offs or chronic poor health [34,35]; and pollutants can affect immune-competency [36,37]. For these reasons, environmental parameters such as habitat type, temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, pH, substrate and depth might indicate anomalies associated with disease, or allow investigators to rule out alternative hypotheses (box 2). For example, marine mammal strandings can be caused by storm events, harmful algae blooms (e.g. Pseudo-nitzschia spp (box 3)), oil spills, boat strikes, or fishing bycatch or discards. Such covariates, if recorded, can give insight into the cause of death, injury or disease. Furthermore, human activities might affect disease risk, and metadata can acknowledge these correlations by, for example, determining if the collection location is affected by fishing, industry, sewage (box 4) or agriculture. If environmental physical or chemical variables cannot be measured during an outbreak, at minimum an accurate date and location reference will facilitate downstream analysis of concurrent long-term, broad-scale datasets from nearby monitoring programmes that include variables such as salinity, temperature and aerial imagery, or even data on species densities and community composition.

Box 2. Understanding the epidemiology and pathogenesis of withering syndrome caused by ‘Candidatus Xenohaliotis californiensis’: a symphony of modern and classic.

The disease withering syndrome (WS) results from a complex relationship among its abalone hosts, the bacterial pathogen (a rickettsia-like organism ‘Candidatus Xenohaliotis californiensis’ (WS-RLO, [38]), and the environment (temperature anomalies) [39–43]. A recently discovered bacteriophage hyperparasite further complicates the disease dynamics in this system [44]. Although first observed 30 years ago in one abalone species, the black abalone (Haliotis cracherodii) [42,45], the aetiology of WS was not accurately identified until 2000, 15 years after its discovery. Initial losses of abalone were attributed to starvation and high temperature during an El Niño event in 1983 [42], but disease spread over time suggested an infectious disease [46]. Subsequently, a previously unknown renal coccidian parasite was suspected [47] as the aetiology of WS but was later shown to be non-pathogenic for adult abalone [48]. Several factors led researchers down the wrong road in diagnosing this disease: (i) available diagnostic tools were limited to light and electron microscopy and field observations; (ii) background information on abalone health was lacking; (iii) understanding of abalone physiology and biology was rudimentary; and (iv) the physiology of WS pathogen (uncultivable, long incubation period, thermal range and wide host infectivity but varying host pathogenicity) was not known.

Only when a suite of classic methods including field observations, histology and transmission studies (with and without antibiotics) were used in combination was it determined that WS in susceptible host species is caused by the RLO at high seawater temperatures [40,42,43,49]. However, taxonomic placement of the WS-RLO required sequencing of the 16S gene [38,50]. Sequencing paved the way for development of PCR [51], ISH [50] and qPCR [52] methods to help better understand field dynamics. These modern methods have allowed us to better understand the transmission and field dynamics of WS [41,53–55].

Identification of the WS-RLO phage was prompted by microscopic observations of what appeared to be a novel RLO based on its size, shape and staining characteristics. However, PCR and ISH suggested that the newly observed RLO was the WS-RLO. Electron microscopy was needed to discover that the WS-RLO was infected by a phage [38] (figure 3). These observations highlight the danger in using nucleic acid-based tests alone and the need for classical, visual methods in diagnosis. Recently, shotgun metagenomics were used on phage-infected samples, to identify the presence of a phage and to characterize its genome (S. Langevin and C. S. Friedman 2015, unpublished data).

Box 3. A non-infectious disease example: identifying domoic acid toxicosis in California sea lions.

Multidisciplinary collaboration and integration of data from several sources (figure 2) were necessary to first identify acute DA toxicosis in stranded California sea lions (CSL: Zalophus californianus) [56,57] (figure 4). In spring 1998, a cluster of CSLs stranding along the central California coast were experiencing seizures but were in good body condition [56,57]. Comprehensive diagnostics on these animals, including serology, culture, histopathology with special stains and PCR, revealed no infectious or traumatic aetiology [57]. However, histopathology did reveal brain lesions similar to those seen in rodents and primates experimentally exposed to DA, a potent neurotoxin [58]. Analytic procedures (liquid chromatography mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), high performance liquid chromatography-ultraviolet and microplate receptor binding) identified DA in serum, urine and/or faeces of some CSL, as well as in plankton and a primary CSL prey item, collected from the same time and region as the strandings. Also coincident with the strandings was a bloom of Pseudo-nitzschia australis, a DA producing diatom, detected using Pseudo-nitzschia species-specific DNA probes. Pseudo-nitzschia australis frustules were detected via scanning electron microscopy in DA-positive faeces from stranded CSLs, and in prey viscera [58,59]. Although DA was not detected in all CSLs with neurologic disease, based on the evidence presented above, collected through multidisciplinary efforts and using both modern and classic methods, the cluster of CSL stranding with neurologic disease was attributed to acute DA toxicosis [57]. While identification of DA in consumed food or in body fluids provides a definitive diagnosis for acute DA toxicosis, rapid clearance of DA [60] and rapid gastrointestinal transit of digesta in CSL [61] often preclude this. Therefore, technological developments since 1998 have focused on improving diagnosis and have resulted in modern approaches such as matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) peptide profiling and neural networks to detect cases of acute DA toxicosis [62]. Improvements of more classic approaches include the development of a solid-phase extraction LC-MS/MS method allowing for DA determination at previously undetectable trace levels in seawater and marine mammal samples [63], thus increasing diagnostic sensitivity.

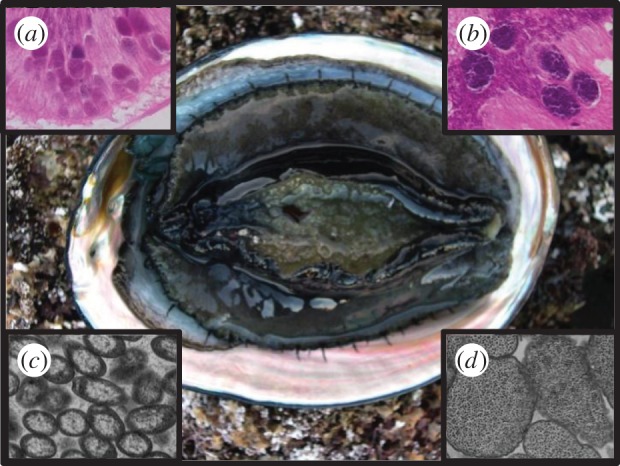

Figure 3.

Withered black abalone, Haliotis cracherodii (photo by David Armstrong); and the WS-disease causing RLO (insets: light (a) and transmission (c) micrographs) and the phage microparasite of the RLO (insets: light (b) and transmission (d) micrographs). (Photos by Carolyn Friedman.)

Figure 4.

California sea lion (Zalophus californianus), and the DA producing diatom, Pseudo- nitzschia australis. (Photo by Jan Rines, University of Rhode Island.)

More recently, a syndrome characterized by epilepsy and caused by chronic DA toxicity [64,65] has been described and named DA epileptic disease. CSLs affected by chronic DA differ in presentation from those with acute toxicosis as they have intermittent seizures, are asymptomatic between seizures, exhibit unusual behaviours and strand individually (versus in clusters as with acute DA cases). Diagnostics reveal no traumatic or infectious aetiology [64,65], but do reveal characteristic lesions in the brain using MRI of live animals or histopathology of dead animals (revealing hippocampal atrophy). These chronic DA cases have raised questions about what other effects chronic DA exposure might have and how these might affect CSL health on both individual and population scales [64,65]. Identifying chronically affected animals can be difficult (MRI is expensive and brain histopathology is only possible on those already dead); therefore, current efforts focus on developing more sensitive, cost-effective, non-invasive diagnostic methods. Examples using more modern diagnostic techniques include an enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect a DA-specific antibody in chronically exposed CSLs [59] and proteomic analysis of CSL plasma to detect chronic DA toxicosis [66].

Box 4. Insights into changing disease dynamics from long-term ecological monitoring: the case of white pox disease in elkhorn coral.

In October 1996, a citizen scientist observed novel disease signs on elkhorn coral, Acropora palmata, at a reef near Key West, FL, USA (figure 5). The citizen contacted coral reef scientists who initiated an investigation of the outbreak by photographing affected colonies, describing gross signs and collecting tissue samples [87]. Photographic monitoring of the affected reef and other reefs in the Florida Keys continued and aetiology investigations were initiated. SMLs were collected from lesions and apparently healthy tissue on affected host corals and from apparently healthy host corals at locations throughout the Caribbean including the Florida Keys, Bahamas and Mexico. Culturing followed by modern redox chemistry biochemical characterization (Biolog analyses) identified four bacteria species associated with lesions and not with apparently healthy tissue. These suspect pathogens were used in challenge experiments with the host coral to satisfy Koch's postulates. These classic techniques identified the bacterium, Serratia marcescens, as a pathogen responsible for white pox disease (WPX) signs [86]. Thus, when this bacterium is confirmed from A. palmata exhibiting WPX, the disease is specifically diagnosed as acroporid serratiosis [86]. Source tracking investigations, combining classic culture and modern molecular techniques, identified human wastewater as a source of S. marcescens [88,89] contributing to initiation of upgrades (in-ground-waste to central sewer systems with at least secondary treatment) in sewage treatment Florida Key-wide, with a completion date in late 2015 [90]. qPCR has since been developed to more rapidly detect the S. marcescens pathogen from SMLs of affected hosts [91,92].

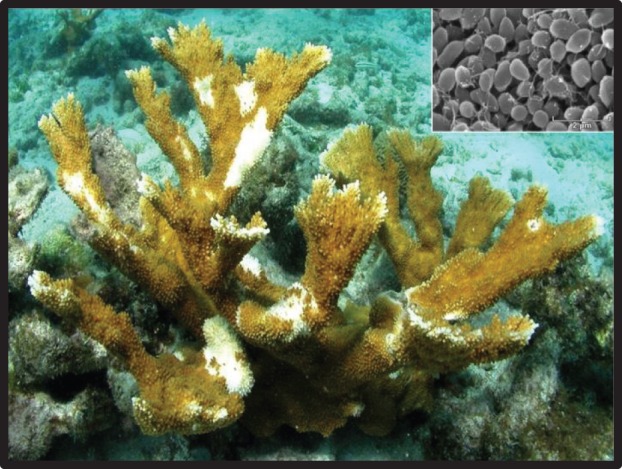

Figure 5.

Caribbean elkhorn coral, Acropora palmata, colony affected with white pox disease. White pox signs are characterized by circular, oblong or pyriform lesions of tissue loss that are located randomly and coral colony wide and are multifocal to coalescing in distribution (Photo by James W. Porter). The bacterium Serratia marcescens (SEM inset) is a pathogen that causes white pox signs. Pathogen identification from white pox lesions diagnoses acroporid serratiosis. (Photo by Shawn Polson.)

Today WPX is common throughout the Caribbean [93–95]. Affected A. palmata populations are monitored extensively, and, when checked, S. marcescens is found (diagnosing acroporid serratiosis) in some, but not all disease cases [86,88,92,93,96]. These findings suggest an additional, unknown WPX agent and classify acroporid serratiosis as one form of WPX [97]. Long-term A. palmata monitoring in the Florida Keys shows a shift from high whole coral colony death in the mid-to-late 1990s and early 2000s to low whole coral colony death since the mid-2000s suggesting decreased pathogen virulence, altered aetiology or increased host resistance [97].

This case study illustrates how multi-decadal ecological monitoring can give insights into changing disease dynamics. Investigations of WPX now combine classic and modern approaches to assess spatial and temporal variation in individual host corals and candidate pathogens (e.g. histopathology, SML whole microbial community, genomics) and to assess how water quality and temperature affect disease.

(b). Community and population

The resident community of organisms can act as potential hosts or vectors and may affect disease outbreaks and/or provide a mechanism of transmission to a particular host or vector. Identifying disease spillover from an alternative host might help explain precipitous declines in a focal host [67]. Non-native species can amplify an endemic pathogen, increasing transmission to the native host or introduce exotic pathogens [68]. Furthermore, observations of the entire community could help determine why a disease has emerged at a particular place and time. For example, identification of Pseudo-nitzschia spp. frustules and domoic acid (DA) in sea lion prey were necessary for initially identifying acute DA toxicity in California sea lions (box 3). A more subtle example is the link between predator and prey species, where a loss of a key predator leads to increases in host density of the prey species followed by a density-dependent disease outbreak [69].

Disease transmission can be sensitive to host population density and demography. Dense host populations often result in more host–host contact, which can facilitate disease spread. Hence information on host density might help explain why some populations seem to experience disease more than others. As an example, bacterial epizootics in sea urchins are more likely at sites with many sea urchins [69]. Population connectivity and demography can be important for disease spread and host recovery. Information about population connectivity can assist in indicating the likelihood of disease spillover to susceptible populations and how long it will take decimated populations to recover after an epizootic. Populations may vary in susceptibility to a pathogen or disease due to local adaptation and or environmental conditions; genetic and population connectivity data for a given species are often lacking or limited (e.g. [39,70–72]). Population-level data are also essential for proper management of disease-affected individuals or when restoring depleted species within and outside disease zones [73].

(c). Organism

The first indication of an epizootic is often through observation of abnormalities on the organismal level. Abnormal behaviour or physical appearance might be noted via direct observation, and gross pathology noted during necropsy. Notable examples include seizure activity in California sea lions [56,73] (box 3), spinning behaviour in menhaden [74] or white spots on the carapace of penaeid shrimp [75]. Such observations will guide sample collection for micro-scale analyses including clinical pathology, toxicology, microscopy, genomics and microbiology. One step in exploring causality is showing that a proposed disease-causing agent is present in diseased animals but absent in healthy tissues and animals. Hence macro- and micro-scale data should be collected from both affected and apparently unaffected tissues, animals and locations. The collection of such data also helps in tracking the spread of the disease within hosts and among locations. Data associated with the collected samples should include metadata such as body size, sex and other phenotypic attributes. Advancements in digital technology and real-time communication provide field biologists and citizen scientists a means to contact experts for guidance in sample and data collection, and also provide a means of accurately ‘describing’ disease signs through photography, even when the collectors lack the precise descriptive terminology of experts [76,77]. Modern digital tools also create a ‘digital paper trail’ that contributes to the necessary aetiological history during a diagnostic investigation. The SSWD epizootic is an example of how disease spread can be documented using every-day modern technology. As sick sea star images became available online, it became easy for citizen scientists to correctly identify and systematically record observations of the event in real time.

(d). Tissues and cells

Visual signs may indicate a specific disease, but not all diseases show clear pathognomonic signs such as lesions, behaviours or tissue discoloration, and further diagnostics are necessary for a definitive diagnosis. Light microscopy of samples such as fixed and stained tissues, tissue scrapings, tissues squashes or circulating cells may show cellular-level damage or infection and has been the gold standard for disease diagnosis (and sometimes, the only diagnostic tool) for many decades [78,79]. It remains an essential tool. Light microscopy may also discern parasite identity in conjunction with differential staining used to elucidate subcellular components linked to a specific taxon. Although viral morphology cannot be observed using light microscopy, microscopic observations of cellular changes may suggest a specific aetiology such as a specific viral infection [80,81] or suggest viral type [75]. Pathogen presence can then be confirmed using additional special stains or molecular methods (described below) and morphology can be confirmed using electron microscopy [82]. Just as for macro-scale observations, micro-scale observations benefit from comparison with normal healthy tissue. Therefore, sampling tissues in addition to the lesion is critical because the aetiologic agent can be at the lesion margin or in the surrounding healthy tissue, not in its necrotic or visually damaged centre. For example, bacterial lesions, such as those caused by Aeromonas salmonicida infection of fish skin, are rapidly invaded by opportunists making culture of the primary pathogen difficult unless early lesions or the leading edge of a lesion are cultured [83]. In some instances, samples from sessile invertebrates can be obtained for some diseases without removing the animal itself. For example, pathogens that cause diseases of corals have been isolated from coral surface mucus layers (SMLs) collected in situ using sterile syringes [84–86] (box 4), while other diseases have required extraction of tissue from collected coral fragments [98,99].

With advancements in molecular methods, the gold standard of disease diagnostics is changing. Modern approaches often now pair histology with an antigen-based or nucleic acid assay to confirm pathogen identification [79]. By linking histological techniques with more modern methods such as immunohistochemistry [100] or in situ hybridization (ISH), one can confirm the identity and abundance of a pathogen [50,101]. This is especially important for parasites that cannot be visualized by light microscopy using standard tissue stains (e.g. viruses) or do not have distinctive, confirmatory features (e.g. most bacteria and many protists). For example, some protists, such as haplosporidia, have plasmodial stages that lack defining characteristics. Until the development of ISH assays for these pathogens, co-infection of two haplosporidians, Haplosporidium nelsoni and H. costale, were not known to be common and oyster (Crassostrea virginica) disease outbreaks may have been incorrectly diagnosed [102]. Another exciting advancement is laser capture micro-dissection developed to capture specific pieces of tissue from histology sections from which DNA or RNA can be extracted for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [53,103] or high-throughput sequencing. This advance truly represents the successful pairing of classic techniques with modern technological advances in robotics and computing.

Classic methods are still used to isolate a pure culture of a putative pathogen. Culture takes advantage of the organism's ability to grow on or metabolize specific substrates and allows for observation of different life-history stages (e.g. growing cysts and spores) and examination of morphology, taxonomy and physiology of the pathogen. The ability to culture an organism is a prerequisite for efforts to fulfil Koch's (or for viruses, River's) postulates to confirm that the isolated pathogen is the causative agent of the disease in controlled experiments [104,105]. However, a lack of suitable marine invertebrate cell lines to isolate and propagate viruses, plus the inability to culture obligate intracellular bacteria, and other obligate intracellular parasites, can hinder diagnosis [106,107]. For non-culturable microorganisms, filtration is a useful method to separate microorganisms based on their size. Recently, filtration has been used to separate viruses from larger microbes (bacteria, fungal or protists) for use in challenge studies and led to the identification of a viral aetiology for SSWD [29] and the molluscan (or ‘ostreid’) herpesvirus OsHV-1 [82,108,109]. However, filtration or culture needs to be paired with complementary techniques to confirm pathogen identity and disease causation. For example, Burge et al. [82] paired modern-specific qPCR and reverse transcriptase (RT) qPCR with classic electron microscopy to confirm OsHV-1 aetiology in the Pacific oyster in California.

(e). Gene

(i). Use of marker genes for pathogen identification and surveillance

When it is not possible to fulfil Koch's postulates, gene-sequence technology can be used to help identify pathogens associated with disease, and or assist in building a body of cumulative evidence suggesting a particular aetiology [110,111]. Modern diagnostic laboratories use gene- and genome-based methods for pathogen identification and surveillance [112,113]. These methods involve sequence analysis and discovery (i.e. sequence-dependent; e.g. 16S clone or amplicon analysis or metagenomics) or detection and or quantification of a target sequence (sequence-independent; e.g. ISH and quantitative PCR) or of a broad suite of sequences (e.g. microarrays). Despite the nuanced differences among these methods, all target one or more known pathogen genes for analysis. Most sequence-independent methods target a single pathogen to detect its presence or absence (e.g. PCR and microarrays) [113,114]. Others use highly sensitive, DNA-based quantification (copy number) of a target gene or genes (i.e. qPCR) or RNA-based gene expression (RT qPCR) [82]. Although the term ‘sequence-independent’ implies that no DNA sequencing is conducted during these techniques, these methods do require a priori knowledge of genome sequence homologies. For example, fluorescent ISH (FISH) and qPCR methods that target complementary gene sequences for quantitative fluorescent labelling each require that researchers know the sequence of the gene they target in order to develop an appropriate probe/primer set.

(ii). High-throughput sequencing approaches for novel pathogen discovery

Recent technological advances in sequence-dependent methods have significantly increased the efficiency and rate of pathogen detection, while substantially reducing the cost. Since the mid-2000s approximately a dozen new high-throughput sequencing (HTS) platforms (e.g. Illumina, PacBio, Ion Torrent) have become available and may provide more efficient ways of finding new potential pathogens. Disease outbreak investigations can employ one or both of the two standard sequencing-dependent approaches that use HTS, namely metagenomics and amplicon sequence analysis. Metagenomics approaches use HTS and bioinformatics analysis to evaluate microbial community composition and function to look for associations between specific organisms and disease. For example, Ng et al. [115] described an unknown anellovirus responsible for the death of captive California sea lions. Similarly, Hewson et al. [29] successfully used shotgun viral metagenomics to develop the qPCR primer/probe combination used to identify a potential causative agent in the recent SSWD event. Due to their power, metagenomic techniques generate millions of sequences, presenting computational challenges [112]. Moreover, because metagenomic analyses depend on sequence databases, new pathogens might not be identifiable by basic metagenomic annotation platforms [112] and may require more advanced methods (e.g. kmer analysis and self-forming map analyses). Amplicon analysis, or the highly parallelized study of variations in a single marker gene, is a tool distinct from metagenomics that can detect novel pathogens. Whereas metagenomics looks at random genomic sequence from a community, amplicon analysis uses PCR to amplify a target gene that is experimentally linked to a known ‘tag’ sequence for sample identification. A single marker gene is amplified among target organisms such as the 16S rRNA gene in bacteria and archaea, the 18S and ITS for eukaryotic genes, and viral capsid DNA and RNA polymerases [113]. Both metagenomics and amplicon sequencing allow detection of potentially novel pathogens, and can be helpful in identification of pathogens more rapidly during an outbreak situation.

3. Merging the classic and the modern to effectively study disease in the marine environment

To effectively study disease in the marine environment requires integration of multiple data-streams, including results from both classic and modern techniques. The case studies (boxes 1–5) included here illustrate the necessity of a union of modern and classic techniques. We have discussed multiple diagnostic methods in earlier sections. Some tools are for pathogen discovery, such as the amplicon or metagenomics diagnostics, and must be paired with appropriate classic approaches to confirm diagnosis. Following pathogen discovery, diagnostic assays can be designed to detect specific pathogens, but proper validation is needed before broad use [79], and uncoupling of classic methods from the modern can lead to issues in disease diagnosis (box 5). Validation should include: analytical sensitivity (limit of detection) and specificity (ability to measure the target and not others in a sample), diagnostic sensitivity (rate of false negative detection) and specificity (rate of false positive detection), reproducibility, and repeatability [79]. As part of assay validation, a gold standard, often light or electron microscopy, is necessary (for calculation of diagnostic sensitivity and specificity). We acknowledge the difficulty in assay validation, and paired approaches for disease diagnoses is a prudent approach.

Box 1. Surveillance is necessary for detection: the case of VHSV in the Pacific Northwest.

In 1988, two Washington fish hatcheries were surprised to find their returning Chinook salmon Oncorhynchus tshawytscha and Coho salmon O. kisutch tested positive for viral haemorrhagic septicaemia virus (VHSV; figure 1), a disease previously known only from freshwater. The industry destroyed 3.8 million salmon eggs in an attempt to contain the virus [7,8]. Subsequent testing of marine species such as Pacific cod Gadus macrocephalus and Pacific herring Clupea pallasii demonstrated their infection with VHSV in wild populations [9–11]. Molecular tools led to a better understanding of the differences among different VHSV strains, including virulence and host susceptibilities. The combined tools of the epidemiologist and the molecular virologist have clarified transmission dynamics of this pathogen and its rhabdovirus cousins, infectious haematopoietic necrosis virus and spring viraemia of carp virus [12–14]. Risk-based surveillance has controlled disease in aquaculture settings, resulting in the elimination of VHSV from Denmark's rainbow trout O. mykiss farms [15].

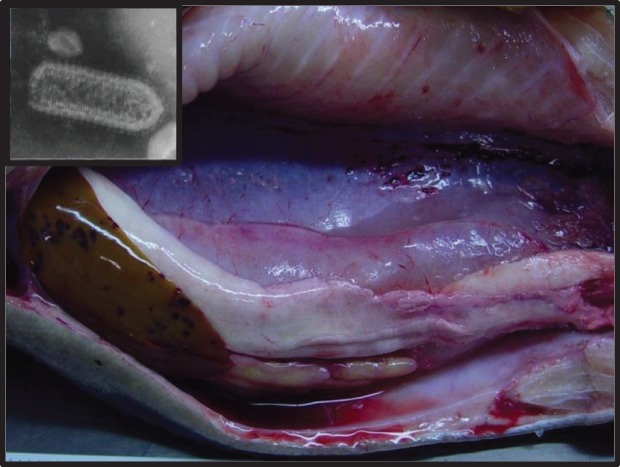

Figure 1.

Internal lesions of VHSV-infected Oncorhynchus mykiss. Diffuse, multifocal haemorrhaging of liver, testes, intestine, swim bladder, skeletal muscle and perivisceral adipose tissue visible. Inset: Transmission electron micrograph of rhabdovirus. (Photo by Aquatic Animal Health Program, Cornell University.)

Box 5. Molecular tools are most powerful when combined with traditional tools, the case of infectious salmon anaemia virus in the Pacific Northwest.

Infectious salmon anaemia virus (ISAV) is the cause of a deadly disease of Atlantic salmon; it has caused a considerable impact on marine aquaculture productions in Norway, Chile, and on the East, but not the West, coasts of the USA and Canada [79]. One of the challenges in managing this pathogen lies in the difficulty in propagating the virus using cell lines, which is the traditional method for fish virus detection [79,116]. Some of the low virulence strains of the virus have been resistant to cell culture [117]. Molecular methods have been developed and are an integral part of ISAV detection and management [78,79], although confirmation of ISAV requires a rigorous combination of cell culture, histology, PCR and sequencing.

In 2011, there was an uncoupling of the traditional methods from the modern during an investigation for the presence of ISAV on the west coast of Canada. Genetic material suggestive of ISAV was reported in free-ranging sockeye salmon using only RT qPCR [117]. Though these results were not confirmed by other methods, the concerns these initial findings raised led to the initiation of an extensive follow-up study employing cell culture, PCR and sequencing. No evidence of disease or virus was detected in seven species of salmonids in the Pacific Northwest from Oregon to Alaska [117]. These results confirm decades of routine monitoring using traditional methods in the Pacific Northwest. This case study is an example of how the use of modern, cutting-edge technologies can be key in pathogen investigations, but that the most effective and efficient approach does not disregard traditional methods, but instead integrates all of the tools that are available.

(a). Final thoughts

We have reviewed classic and modern approaches for diagnosing marine diseases. For those interested in more details, our electronic supplementary material contains key references (books, websites, how-to-guides) on data and samples to collect, storage and preservation methods, and diagnostic tests. Outbreak response will further improve as new diagnostic tools are refined and taught. The development of centralized databases, reporting networks and data repositories for marine disease observations will allow a more rapid and comprehensive response. In addition, simple real-time diagnostic tools for farmers, fishers or citizen scientists, such as the Shrimple [118] or other future technological advances, will make marine diagnostics commonplace. However, we hope that our various examples have shown that, although advanced technologies have greatly improved our ability to rapidly and accurate identify the aetiologic agents of disease and epizootics in the marine environment, these tools are only useful when combined with data from more classic approaches. In addition, national contingency plans for diagnosis and management of both current and unexpected diseases are necessary [112,119]. Finally to understand the importance of disease in the marine ecosystem, we need long-term, baseline data with which to compare findings during a disease investigation.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge helpful discussions with other members of the EIMD-RCN. Additionally, N. Rivlin provided technical assistance and C. Closek, R. Carnegie and C. Marino editorial comments. We also thank the anonymous reviewers who provided helpful comments.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed to writing and revising the article. C.A.B., C.S.F., R.G., M.H., K.D.L., L.D.M., K.C.P., K.P.S. and R.V.T. were responsible for the concept and design of the article.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was conducted as part of the Ecology of Infectious Marine Disease Research Coordination Network (EIMD-RCN) (http://www.eeb.cornell.edu/ecologymarinedisease/Home/Home.html) funded by National Science Foundation (NSF) Ecology and Evolution of Infectious Diseases grant OCE-1215977. K.P.S. acknowledges funding provided by NSF-NIH Ecology of Infectious Disease program grant EF1015032. K.C.P. was supported by the NSF (OCE-1335657). NSF grant IOS no. 1017458 to L.D.M. C.A.B. and C.S.F. acknowledge support from California Sea Grant (NA10OAR4170060).

References

- 1.Sweet MJ, Bateman KS. 2015. Diseases in marine invertebrates associated with mariculture and commercial fisheries. J. Sea Res. 104, 16–32. ( 10.1016/j.seares.2015.06.016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lafferty KD, Harvell CD, Conrad JM, Friedman CS, Kent ML, Kuris AM, Powell EN, Rondeau D, Saksida SM. 2015. Infectious diseases affect marine fisheries and aquaculture economics. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 7, 471–496. ( 10.1146/annurev-marine-010814-015646) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burge CA, et al. 2014. Climate change influences on marine infectious diseases: implications for management and society. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 6, 249–277. ( 10.1146/annurev-marine-010213-135029) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim K, Dobson AP, Gulland FMD, Harvell CD. 2005. Diseases and the conservation of marine biodiversity. In Marine conservation biology: the science of maintaining the sea's biodiversity (eds Norse EA, Chowder LB), pp. 149–166. Washington, DC: Island Press. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harvell CD, et al. 1999. Emerging marine diseases–climate links and anthropogenic factors. Science 285, 1505–1510. ( 10.1126/Science.285.5433.1505) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ward JR, Lafferty KD. 2004. The elusive baseline of marine disease: are diseases in ocean ecosystems increasing? PLoS Biol. 2, 542–547. ( 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020120) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brunson R, True J, Yancey J. 1989. VHS virus isolated at Makah National Fish Hatchery. In Fish Health Sect. Am. Fish. Soc. Newsletter 17, pp. 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hopper K. 1989. The isolation of VHSV from Chinook salmon at Glenwood Springs, Orcas Islands, Washington. Fish Health Sect. Am. Fish. Soc. Newsletter 17, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyers T, Sullivan J, Emmenegger E, Follett J, Short S, Batts W, Winton J. 1991. Isolation of viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus from Pacific cod Gadus macrocephalus in Prince William Sound, Alaska. In Proc. 2nd Int. Symp. on Viruses of Lower Vert, 29–31 July 1991, Corvallis, OR, USA, pp. 83–91. Oregon State University.

- 10.Meyers TR, Short S, Lipson K, Batts WN, Winton JR, Wilcock J, Brown E. 1994. Association of viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus with epizootic hemorrhages of the skin in Pacific Herring Clupea harengus pallasi from Prince William Sound and Kodiak Island, Alaska, USA. Dis. Aqu. Organ. 19, 27–37. ( 10.3354/dao019027) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyers TR, Sullivan J, Emmenegger E, Follett J, Short S, Batts WN, Winton JR. 1992. Identification of viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus isolated from Pacific Cod Gadus macrocephalus in Prince-William-Sound, Alaska, USA. Dis. Aqu. Organ. 12, 167–175. ( 10.3354/dao012167) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emmenegger EJ, et al. 2011. Development of an aquatic pathogen database (AquaPathogen X) and its utilization in tracking emerging fish virus pathogens in North America. J. Fish Dis. 34, 579–587. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2011.01270.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hershberger P, Gregg J, Grady C, Collins R, Winton J. 2010. Kinetics of viral shedding provide insights into the epidemiology of viral hemorrhagic septicemia in Pacific herring. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 400, 187–193. ( 10.3354/meps08420) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Padhi A, Verghese B. 2012. Molecular evolutionary and epidemiological dynamics of a highly pathogenic fish rhabdovirus, the spring viremia of carp virus (SVCV). Vet. Microbiol. 156, 54–63. ( 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.10.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bang Jensen B, Ersboll AK, Korsholm H, Skall HF, Olesen NJ. 2014. Spatio-temporal risk factors for viral haemorrhagic septicaemia (VHS) in Danish aquaculture. Dis. Aquat. Organ 109, 87–97. ( 10.3354/dao02706) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lafferty KD, Porter JW, Ford SE. 2004. Are diseases increasing in the ocean? Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 35, 31–54. ( 10.1146/Annurev.Ecolsys.35.021103.105704) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shilova IN, et al. 2014. A microarray for assessing transcription from pelagic marine microbial taxa. ISME J. 8, 1476–1491. ( 10.1038/ismej.2014.1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Work T, Meteyer C. 2014. To understand coral disease, look at coral cells. EcoHealth 11, 610–618. ( 10.1007/s10393-014-0931-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gulland FM, Hall AJ. 2007. Is marine mammal health deteriorating? Trends in the global reporting of marine mammal disease. EcoHealth 4, 135–150. ( 10.1007/s10393-007-0097-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lessios HA, Cubit JD, Robertson DR, Shulman MJ, Parker MR, Garrity SD, Levings SC. 1984. Mass mortality of Diadema antillarum on the Caribbean coast of Panama. Coral Reefs 3, 173–182. ( 10.1007/BF00288252) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lessios HA. 1988. Mass mortality of Diadema antillarum in the Caribbean; what have we learned? Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 19, 371–393. ( 10.1146/Annurev.Es.19.110188.002103) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carpenter RC. 1988. Mass mortality of a Caribbean sea-urchin; immediate effects on community metabolism and other herbivores. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 85, 511–514. ( 10.1073/pnas.85.2.511) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paine RT. 1995. A conversation on refining the concept of keystone species. Conserv. Biol. 9, 962–964. ( 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1995.09040962.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paine RT. 1966. Food web complexity and species diversity. Am. Nat. 100, 65–75. ( 10.1086/282400) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lessios HA. 2005. Diadema antillarum populations in Panama twenty years following mass mortality. Coral Reefs 24, 125–127. ( 10.1007/s00338-004-0443-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levitan DR, Edmunds PJ, Levitan KE. 2014. What makes a species common? No evidence of density-dependent recruitment or mortality of the sea urchin Diadema antillarum after the 1983–1984 mass mortality. Oecologia 175, 117–128. ( 10.1007/s00442-013-2871-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lessios HA. 1988. Population-dynamics of Diadema antillarum (Echinodermata, Echinoidea) following mass mortality in Panama. Mar. Biol. 99, 515–526. ( 10.1007/Bf00392559) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lessios HA, Robertson DR, Cubit JD. 1984. Spread of Diadema mass mortality through the Caribbean. Science 226, 335–337. ( 10.1126/science.226.4672.335) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hewson I, et al. 2014. Densovirus associated with sea-star wasting disease and mass mortality. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 17 278–17 283. ( 10.1073/pnas.1416625111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dungan ML, Miller TE, Thomson DA. 1982. Catastrophic decline of a top carnivore in the Gulf of California rocky intertidal zone. Science 216, 989–991. ( 10.1126/science.216.4549.989) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eckert G, Engle JM, Kushner D. 1999. Sea star disease and population declines at the Channel Islands. In Proc. of the Fifth California Islands Symp., pp. 390–393. Washington, DC: Minerals Management Service.

- 32.Bates AE, Hilton BJ, Harley CD. 2009. Effects of temperature, season and locality on wasting disease in the keystone predatory sea star Pisaster ochraceus. Dis. Aquat. Org. 86, 245–251. ( 10.3354/dao02125) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blanchette CA, Richards DV, Engle JM, Broitman BR, Gaines SD. 2005. Regime shifts, community change and population booms of keystone predators at the Channel Islands. In Proc. of the Sixth California Islands Symp. (eds DK Garcelon, CA Schwemm), pp. 435–442. National Park Service Technical Publication CHIS-05-01. Arcata, CA: Institute for Wildlife Studies.

- 34.Taylor JC, Miller JM. 2001. Physiological performance of juvenile southern flounder, Paralichthys lethostigma (Jordan and Gilbert, 1884), in chronic and episodic hypoxia. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 258, 195–214. ( 10.1016/S0022-0981(01)00215-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thronson A, Quigg A. 2008. Fifty-five years of fish kills in coastal Texas. Est. Coasts 31, 802–813. ( 10.1007/s12237-008-9056-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moreau P, Faury N, Burgeot T, Renault T. 2015. Pesticides and ostreid herpesvirus 1 infection in the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas. PLoS ONE 10, e0130628 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0130628) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Renault T. 2015. Immunotoxicological effects of environmental contaminants on marine bivalves. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 46, 88–93. ( 10.1016/j.fsi.2015.04.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friedman CS, Andree KB, Beauchamp KA, Moore JD, Robbins TT, Shields JD, Hedrick RP. 2000. 'Candidatus Xenohaliotis californiensis’, a newly described pathogen of abalone, Haliotis spp., along the west coast of North America. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microb. 50, 847–855. ( 10.1099/00207713-50-2-847) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miner CM, Altstatt JM, Raimondi PT, Minchinton TE. 2006. Recruitment failure and shifts in community structure following mass mortality limit recovery prospects of black abalone. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 327, 107–177. ( 10.3354/meps327107) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moore JD, Robbins TT, Friedman CS. 2000. Withering syndrome in farmed red abalone Haliotis rufescens: thermal induction and association with a gastrointestinal Rickettsiales-like prokaryote. J. Aquat. Anim. Health 12, 26–34. () [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Friedman CS, Wight N, Crosson LM, VanBlaricom GR, Lafferty KD. 2014. Reduced disease in black abalone following mass mortality: phage therapy and natural selection. Front. Microbiol. 5, 10 ( 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00078) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tissot BN. 1988. Mass mortality of black abalone in Southern-California. Am. Zool. 28, A69. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Friedman CS, Biggs W, Shields JD, Hedrick RP. 2002. Transmission of withering syndrome in black abalone, Haliotis cracherodii leach. J. Shellfish Res. 21, 817–824. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Friedman CS, Crosson LM. 2012. Putative phage hyperparasite in the rickettsial pathogen of abalone, ‘Candidatus Xenohaliotis californiensis’. Microb. Ecol. 64, 1064–1072. ( 10.1007/s00248-012-0080-4). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haaker P, Parker D, Togstad H, Richards D, Davis G, Friedman C. 1992. Mass mortality and withering syndrome in black abalone, Haliotis cracherodii in California. In Abalone of the world: biology, fisheries and culture. Proc. of the First Int. Symp. on abalone (eds SA Shepherd, MJ Tegner, S AGuzman del Proo), pp. 214–224. Cambridge, UK: University Press.

- 46.Lafferty KD, Kuris AM. 1993. Mass mortality of the abalone Haliotis cracherodii on the Channel Islands: tests of epidemiological hypotheses. Mar. Ecol. Progress Ser. 96, 239–248. ( 10.3354/meps096239) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Friedman CS, Roberts W, Kismohandaka G, Hedrick RP. 1993. Transmissibility of a coccidian parasite of abalone, Haliotis spp. J. Shellfish Res. 12, 201–205. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Friedman CS, Gardner GR, Hedrick RP, Stephenson M, Cawthorn RJ, Upton SJ. 1995. Pseudoklossia haliotis sp.n. (Apicomplexa) from the kidney of California abalone, Haliotis spp (Mollusca). J. Invert. Pathol. 66, 33–38. ( 10.1006/jipa.1995.1057) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Friedman CS, Scott BB, Strenge RE, Vadopalas B, Mccormick TB. 2007. Oxytetracycline as a tool to manage and prevent losses of the endangered white abalone, Haliotis sorenseni, caused by withering syndrome. J. Shellfish Res. 26, 877–885. ( 10.2983/0730-8000(2007)26%5B877:Oaattm%5D2.0.Co;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Antonio DB, Andree KB, Moore JD, Friedman CS, Hedrick RP. 2000. Detection of Rickettsiales-like prokaryotes by in situ hybridization in black abalone, Haliotis cracherodii, with withering syndrome. J. Invert. Pathol. 75, 180–182. ( 10.1006/jipa.1999.4906) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Andree KB, Friedman CS, Moore JD, Hedrick RP. 2000. A polymerase chain reaction assay for the detection of genomic DNA of a Rickettsiales-like prokaryote associated with withering syndrome in California abalone. J. Shellfish Res. 19, 213–218. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Friedman CS, Wight N, Crosson LM, White SJ, Strenge RM. 2014. Validation of a quantitative PCR assay for detection and quantification of 'Candidatus Xenohaliotis californiensis’. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 108, 251–259. ( 10.3354/dao02720) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Crosson LM, Wight N, VanBlaricom GR, Kiryu I, Moore JD, Friedman CS. 2014. Abalone withering syndrome: distribution, impacts, current diagnostic methods and new findings. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 108, 261–270. ( 10.3354/dao02713) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ben-Horin T, Lenihan HS, Lafferty KD. 2013. Variable intertidal temperature explains why disease endangers black abalone. Ecology 94, 106–168. ( 10.1890/11-2257.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lafferty KD, Ben-Horin T. 2013. Abalone farm discharges the withering syndrome pathogen into the wild. Front. Microbiol. 4, 373 ( 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00373) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gulland FMD, Haulena M, Fauquier D, Langlois G, Lander ME, Zabka T, Duerr R. 2002. Domoic acid toxicity in Californian sea lions (Zalophus californianus): clinical signs, treatment and survival. Vet. Rec. 150, 475–480. ( 10.1136/vr.150.15.475) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gulland F. 2000. Domoic acid toxicity in California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) stranded along the central California coast, May–October 1998. In Report to the National Marine Fisheries Service Working Group on Unusual Marine Mammal Mortality Events. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-OPR-17. US Department of Commerce.

- 58.Scholin CA, et al. 2000. Mortality of sea lions along the central California coast linked to a toxic diatom bloom. Nature 403, 80–84. ( 10.1038/47481) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lefebvre KA, et al. 1999. Detection of domoic acid in northern anchovies and California sea lions associated with an unusual mortality event. Nat. Toxins 7, 85–92. () [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Truelove J, Iverson F. 1994. Serum domoic acid clearance and clinical observations in the cynomolgus monkey and Sprague-Dawley bat following single iv-dose. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 52, 479–486. ( 10.1007/BF00194132) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Helm RC. 1994. Rate of digestion in 3 species of pinnipeds. Can. J. Zool. 62, 1751–1756. ( 10.1139/z84-258) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Neely BA, Soper JL, Greig DJ, Carlin KP, Favre EG, Gulland FMD, Almeida JS, Janech MG. 2012. Serum profiling by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry as a diagnostic tool for domoic acid toxicosis in California sea lions. Proteome Sci. 10, 12 ( 10.1186/1477-5956-10-18) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang ZH, Maucher-Fuquay J, Fire SE, Mikulski CM, Haynes B, Doucette GJ, Ramsdell JS. 2012. Optimization of solid-phase extraction and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry for the determination of domoic acid in seawater, phytoplankton, and mammalian fluids and tissues. Anal. Chim. Acta 715, 71–79. ( 10.1016/j.aca.2011.12.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Goldstein T, et al. 2008. Novel symptomatology and changing epidemiology of domoic acid toxicosis in California sea lions (Zalophus californianus): an increasing risk to marine mammal health. Proc. R. Soc. B 275, 267–276. ( 10.1098/rspb.2007.1221) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ramsdell JS, Gulland FM. 2014. Domoic acid epileptic disease. Mar. Drugs 12, 1185–1207. ( 10.3390/md12031185) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Neely BA, Ferrante JA, Chaves JM, Soper JL, Almeida JS, Arthur JM, Gulland FMD, Janech MG. 2015. Proteomic analysis of plasma from California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) reveals apolipoprotein E as a candidate biomarker of chronic domoic acid toxicosis. PLoS ONE 10, 18 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0123295) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McCallum H. 2012. Disease and the dynamics of extinction. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 367, 2828–2839. ( 10.1098/rstb.2012.0224) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Torchin ME, Lafferty KD, Kuris AM. 2002. Parasites and marine invasions. Parasitology124, S137–S151 ( 10.1017/S0031182002001506) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lafferty KD. 2004. Fishing for lobsters indirectly increases epidemics in sea urchins. Ecol. Appl. 14, 1566–1573. ( 10.1890/03-5088) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chambers MD, VanBlaricom GR, Hauser L, Utter F, Friedman CS. 2006. Genetic structure of black abalone (Haliotis cracherodii) populations in the California islands and central California coast: impacts of larval dispersal and decimation from withering syndrome. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 331, 173–185. ( 10.1016/j.jembe.2005.10.016) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hamm DE, Burton RS. 2000. Population genetics of black abalone, Haliotis cracherodii, along the central California coast. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 254, 235–247. ( 10.1016/s0022-0981(00)00283-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chambers MD, VanBlaricom G, Friedman CS, Hurn H, Garcelon D, Schwemm C.2005. Drift card simulation of larval dispersal from San Nicolas Island, CA, during black abalone spawning season. In Proc. of the Sixth California Islands Symp. (eds DK Garcelon, CA Schwemm), pp. 421–434, Technical Publication CHIS-05-01. Arcata, CA: Institute for Wildlife Studies.

- 73.Subasinghe RP, McGladdery SE, Hill BJ. 2004. Surveillance and zoning for aquatic animal diseases. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper 451. Rome, Italy: FAO. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stephens EB, Newman MW, Zachary AL, Hetrick FM. 1980. A viral aetiology for the annual spring epidemics of Atlantic menhaden Brevoortia tyrannus (Latrobe) in Chesapeake Bay. J. Fish Dis. 3, 387–398. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2761.1980.tb00423.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lightner DV, Redman RM. 1998. Shrimp diseases and current diagnostic methods. Aquaculture 164, 201–220. 10.1016/S0044-8486(98)00187-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Work TM, Aeby GS. 2006. Systematically describing gross lesions in corals. Dis. Aqu. Organ. 70, 155–160. ( 10.3354/Dao070155) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Munson L, Craig LE, Miller MA, Kock ND, Simpson RM, Wellman ML, Sharkey LC, Birkebak TA, Trainin ACVP. 2010. Elements of good training in anatomic pathology. Vet. Pathol. 47, 995–1002. ( 10.1177/0300985810377725) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Luna LG. 1968. Manual of histologic staining methods of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. New York, NY: Blakiston Division, McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- 79.World Organisation for Animal Health. 2015. Manual of diagnostic tests for aquatic animals 2015. Paris, France: Office International des Epizooties.

- 80.Burge CA, Griffin FJ, Friedman CS. 2006. Mortality and herpesvirus infections of the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas in Tomales Bay, California, USA. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 72, 31–43. ( 10.3354/dao072031) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Burge CA, et al. 2007. Summer seed mortality of the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas Thunberg grown in Tomales Bay, California, USA: the influence of oyster stock, planting time, pathogens, and environmental stressors. J. Shellfish Res. 26, 163–172. ( 10.2983/0730-8000(2007)26%5B163:SSMOTP%5D2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Burge CA, Friedman CS. 2012. Quantifying ostreid herpesvirus (OsHV-1) genome copies and expression during transmission. Microb. Ecol. 63, 596–604. ( 10.1007/s00248-011-9937-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Noga EJ. 2011. Fish disease: diagnosis and treatment. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kushmaro A, Rosenberg E, Fine M, Loya Y. 1997. Bleaching of the coral Oculina patagonica by Vibrio AK-1. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 147, 159–165. ( 10.3354/meps147159) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Richardson LL, Goldberg WM, Carlton RG, Halas JC. 1998. Coral disease outbreak in the Florida Keys: plague type II. Revista De Biol. Trop. 46, 187–198. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Patterson KL, Porter JW, Ritchie KE, Polson SW, Mueller E, Peters EC, Santavy DL, Smiths GW. 2002. The etiology of white pox, a lethal disease of the Caribbean elkhorn coral, Acropora palmata. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 8725–8730. ( 10.1073/pnas.092260099) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Holden C. 1996. Coral disease hotspot in the Florida Keys. Science 274, 2017 ( 10.1126/science.274.5295.2017a) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sutherland KP, Porter JW, Turner JW, Thomas BJ, Looney EE, Luna TP, Meyers MK, Futch JC, Lipp EK. 2010. Human sewage identified as likely source of white pox disease of the threatened Caribbean elkhorn coral, Acropora palmata. Environ. Microbiol. 12, 1122–1131. ( 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02152.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sutherland KP, Shaban S, Joyner JL, Porter JW, Lipp EK. 2011. Human pathogen shown to cause disease in the threatened Elkhorn coral Acropora palmata. PLoS ONE 6, e23468. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0023468) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.USEPA 2013. Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Water Quality Protection Program: Report to Congress. Atlanta, GA: United States Environmental Protection Agency, Region 4 Office.

- 91.Joyner J, Wanless D, Sinigalliano CD, Lipp EK. 2014. Use of quantitative real-time PCR for direct detection of Serratia marcescens in marine and other aquatic environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 1679–1683. ( 10.1128/AEM.02755-13) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Joyner JL, Sutherland KP, Kemp DW, Berry B, Griffin A, Porter JW, Amador MH, Noren HK, Lipp EK. 2015. Systematic analysis of white pox disease in Acropora palmata of the Florida Keys and role of Serratia marcescens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 4451–4457. ( 10.1128/AEM.00116-15) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rodríguez-Martínez RE, Banaszak AT, McField MD, Beltrán-Torres AU, Álvarez-Filip L. 2014. Assessment of Acropora palmata in the mesoamerican reef system. PLoS ONE 9, e96140 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0096140) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rogers CS, Muller EM. 2012. Bleaching, disease and recovery in the threatened scleractinian coral Acropora palmata in St. John, US Virgin Islands: 2003–2010. Coral Reefs 31, 807–819. ( 10.1007/s00338-012-0898-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Williams DE, Miller MW. 2012. Attributing mortality among drivers of population decline in Acropora palmata in the Florida Keys (USA). Coral Reefs 31, 369–382. ( 10.1007/s00338-011-0847-y) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lesser MP, Jarett JK. 2014. Culture-dependent and culture-independent analyses reveal no prokaryotic community shifts or recovery of Serratia marcescens in Acropora palmata with white pox disease. Fems Microbiol. Ecol. 88, 457–467. ( 10.1111/1574-6941.12311) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sutherland KP, Berry B, Park A, Kemp DW, Kemp KM, Lipp EK, Porter JW. 2016. Shifting white pox aetiologies affecting Acropora palmata in the Florida Keys, 1994–2014. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 371, 20150205 ( 10.1098/rstb.2015.0205) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ben-Haim Y, Rosenberg E. 2002. A novel Vibrio sp pathogen of the coral Pocillopora damicornis. Mar. Biol. 141, 47–55. ( 10.1007/s00227-002-0797-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ushijima B, Videau P, Aeby GS, Callahan SM. 2013. Draft genome sequence of Vibrio coralliilyticus strain OCN008, Isolated from Kane'ohe Bay, Hawai'i. Genome Announc. 1, e00786-13. ( 10.1128/genomeA.00786-13) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ramos-Vara JA, Miller MA. 2014. When tissue antigens and antibodies get along: revisiting the technical aspects of immunohistochemistry: the red, brown, and blue technique. Vet. Pathol. 51, 42–87. ( 10.1177/0300985813505879) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Carnegie RB, Barber BJ, Distel DL. 2003. Detection of the oyster parasite Bonamia ostreae by fluorescent in situ hybridization. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 55, 247–252. ( 10.3354/dao055247) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Stokes NA, Burreson EM. 2001. Differential diagnosis of mixed Haplosporidium costale and Haplosporidium nelsoni infections in the eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica, using DNA probes. J. Shellfish Res. 20, 207–213. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Small H, Sturve J, Bignell J, Longshaw M, Lyons B, Hicks R, Feist S, Stentiford G. 2008. Laser-assisted microdissection: a new tool for aquatic molecular parasitology. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 82, 151 ( 10.3354/dao01983) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Koch R. 1893. Ueber den augenblicklichen Stand der bakteriologischen Choleradiagnose [About the instantaneous state of the bacteriological diagnosis of cholera]. Zeitschrift für Hygiene und Infektionskrankheiten 14, 31–38. ( 10.1007/BF02284324) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rivers TM. 1937. Viruses and Koch's postulates. J. Bacteriol. 33, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rinkevich B. 2005. Marine invertebrate cell cultures: new millennium trends. Mar. Biotechnol. 7, 429–439. ( 10.1007/s10126-004-0108-y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rinkevich B. 2011. Cell cultures from marine invertebrates: new insights for capturing endless stemness. Mar. Biotechnol. 13, 345–354. ( 10.1007/s10126-010-9354-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Arzul I, Renault T, Lipart C. 2001. Experimental herpes-like viral infections in marine bivalves: demonstration of interspecies transmission. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 46, 1–6. ( 10.3354/dao046001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Schikorski D, Renault T, Saulnier D, Faury N, Moreau P, Pepin JF. 2011. Experimental infection of Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas spat by ostreid herpesvirus 1: demonstration of oyster spat susceptibility. Vet. Res. 42, 27 ( 10.1186/1297-9716-42-27) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Fredricks DN, Relman DA. 1996. Sequence-based identification of microbial pathogens: a reconsideration of Koch's postulates. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 9, 18–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lipkin WI. 2010. Microbe hunting. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. R 74, 363–377. ( 10.1128/Mmbr.00007-10) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.World Organization for Animal Health. 2015. Biotechnology in the diagnosis of infectious diseases. In Manual of diagnostic tests for aquatic animals2015. See http://www.oie.int/fileadmin/Home/eng/Health_standards/tahm/GUIDE_3.2_BIOTECH_DIAG_INF_DIS.pdf.

- 113.Bass D, Stentiford GD, Littlewood DT, Hartikainen H. 2015. Diverse applications of environmental DNA methods in parasitology. Trends Parasitol. 31, 499–513. ( 10.1016/j.pt.2015.06.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Small HJ, Williams TD, Sturve J, Chipman JK, Southam AD, Bean TP, Lyons BP, Stentiford GD. 2010. Gene expression analyses of hepatocellular adenoma and hepatocellular carcinoma from the marine flatfish Limanda limanda. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 88, 127 ( 10.3354/dao02148) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ng TFF, Suedmeyer WK, Wheeler E, Gulland F, Breitbart M. 2009. Novel anellovirus discovered from a mortality event of captive California sea lions. J. Gen. Virol. 90, 1256–1261. ( 10.1099/vir.0.008987-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.American Fisheries Society. 2012. Suggested procedures for the detection and identification of certain finfish and shellfish pathogens. Bethesda, MD: American Fisheries Society. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Amos KH, et al. 2014. U.S. response to a report of infectious salmon anemia virus in western North America. Fisheries 39, 501–506. ( 10.1080/03632415.2014.967348) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Powell JWB, Burge EJ, Browdy CL, Shepard EF. 2006. Efficiency and sensitivity determination of Shrimple®, an immunochromatographic assay for white spot syndrome virus (WSSV), using quantitative real-time PCR. Aquaculture 257, 167–172. ( 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2006.03.010) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Groner ML, et al. 2016. Managing marine disease emergencies in an era of rapid change. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 371, 20150364 ( 10.1098/rstb.2015.0364) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.