Abstract

Understanding molecular mechanisms underlying plant salinity tolerance provides valuable knowledgebase for effective crop improvement through genetic engineering. Current proteomic technologies, which support reliable and high-throughput analyses, have been broadly used for exploring sophisticated molecular networks in plants. In the current study, we compared phosphoproteomic and proteomic changes in roots of different soybean seedlings of a salt-tolerant cultivar (Wenfeng07) and a salt-sensitive cultivar (Union85140) induced by salt stress. The root samples of Wenfeng07 and Union85140 at three-trifoliate stage were collected at 0 h, 0.5 h, 1 h, 4 h, 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h after been treated with 150 mm NaCl. LC-MS/MS based phosphoproteomic analysis of these samples identified a total of 2692 phosphoproteins and 5509 phosphorylation sites. Of these, 2344 phosphoproteins containing 3744 phosphorylation sites were quantitatively analyzed. Our results showed that 1163 phosphorylation sites were differentially phosphorylated in the two compared cultivars. Among them, 10 MYB/MYB transcription factor like proteins were identified with fluctuating phosphorylation modifications at different time points, indicating that their crucial roles in regulating flavonol accumulation might be mediated by phosphorylated modifications. In addition, the protein expression profiles of these two cultivars were compared using LC MS/MS based shotgun proteomic analysis, and expression pattern of all the 89 differentially expressed proteins were independently confirmed by qRT-PCR. Interestingly, the enzymes involved in chalcone metabolic pathway exhibited positive correlations with salt tolerance. We confirmed the functional relevance of chalcone synthase, chalcone isomerase, and cytochrome P450 monooxygenase genes using soybean composites and Arabidopsis thaliana mutants, and found that their salt tolerance were positively regulated by chalcone synthase, but was negatively regulated by chalcone isomerase and cytochrome P450 monooxygenase. A novel salt tolerance pathway involving chalcone metabolism, mostly mediated by phosphorylated MYB transcription factors, was proposed based on our findings. (The mass spectrometry raw data are available via ProteomeXchange with identifier PXD002856).

Cultivated soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merrill) is one of the most important legume crops (1, 2), and is estimated to contributes to 30% of edible vegetable oil and 69% of protein-rich food or feed supplements worldwide (3). However, the yield of soybean is significantly reduced under environmental stresses such as salinity especially during the early vegetative growth stage (3, 4). Soil salinity is estimated to affect at least 20% of the irrigated land worldwide (5, 6) and could affect 50% of the cultivated land by year 2050 (7).

High salinity causes oxidative stress and ionic imbalance in plant cells, and further inhibits the growth and development of the whole plant (6, 8, 9). Elimination of excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS)1 via glutathione-ascorbate cycle and maintaining tolerable salt levels inside the plant cells through exportation or compartmentalization are generally accepted as two major strategies used by plants to survive salinity stress (10). Plants have evolved a series of adaptive mechanisms to sense and respond to salinity cues and these include active involvements of multiple phosphorylation cascades, such as salt overly sensitive (SOS) pathway, phosphatidic acid (PA)-mediated activation of calcium-dependent protein kinase (CDPK), abscisic acid (ABA)-regulated activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades (11–14). Phosphorylation of specific signaling components are known to be initiated at critical time points after plants been subjected to the salt stresses (15) and they coordinate specific metabolic processes, cell-wall porosity and lateral root initiation to help plants adapt to salt stresses (10, 13, 16).

Recently, major high throughput strategies including transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic approaches, have been used to dissect the responses of soybean root to salinity stress (17–21). However, most of these studies were focused on relatively late responses to salinity (e.g. over 48 h after Na+ treatment), earlier signal events minutes after the treatments were apparently ignored. Signaling events through protein phosphorylation are well known to play critical roles mediating appropriate physiological responses in determining the salt-tolerant capability of different soybean species. Many techniques have recently been developed for the specific enrichment of phosphopeptides; these includes immobilized metal affinity chromatography (22), strong cation-exchange chromatography (23, 24), and TiO2 affinity chromatography (25). The TiO2 affinity chromatography has been generally accepted as one of the most effective approaches in enrichment of phosphopeptides (26).

Glycine max cultivar Union85140 and Glycine soja cultivar Wenfeng07 are salinity sensitive- and tolerant-cultivar, respectively; their drastic difference in salt tolerance enable us to explore the critical proteins contributing the salt tolerance in cultivated soybeans (27, 28). In the present research, we compared the proteomes and phosphoproteomes of these two soybean species at different time points after salinity treatment. Technologies including TiO2 affinity chromatography, 2-DE MS/MS, and LC-MS/MS were used to generate the row proteome and phosphoproteome data; large-scale bioinformatic analyses including gene ontology (GO) enrichment and phosphorylation motif enrichment were conducted to identified interested targets; functional characterization of selected target genes using gain-of-function composites in soybean and loss-of-function mutant of their homologs in Arabidopsis were conducted to confirm their role in regulating plant tolerance to salt stresses. Our results reveal that normal chalcone metabolism plays a potential role in regulating plant responses to salt stresses in soybean and provide new insights into the mechanism contributing to the difference in salt tolerance of these two soybean cultivars.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plant Materials and Stress Treatments

Seeds of Glycine max cultivar Union85140 (a salt sensitive species) and Glycine soja cultivar Wenfeng07 (a salt tolerant species) were kindly provided by Prof. Lijuan Qiu from the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. The seeds were surface sterilized with 5% NaClO for 5 min and rinsed three times with sterile distilled H2O. Seeds were germinated in wet filter paper at room temperature (about 22–25 °C) with 40–60% humidity. The seedlings were transferred to 1/4 fold Hoagland's solution. Seedlings at three-trifoliate stage were treated with 150 mm NaCl for 0 h, 0.5 h, 1 h, 4 h, 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h before the root samples were collected for analyses. All the samples were stored at −80 °C until use.

Protein Extraction

Total proteins from roots was extracted as described by Lv et al (29) with minor modifications. Briefly, about 4 g of root tissue for each sample was ground into fine powder in liquid nitrogen. The powder was thoroughly suspended in 45 ml of precooled TCA/Acetone (v:v = 1: 9); the homogenate was settled for overnight and then centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 15 min. The pellet was washed three times with acetone and the residual acetone was removed by vacuum. All the above experiments were carried out at 4 °C. 50 mg white powder was resuspended in 800 μl SDT lysis buffer (4% SDS, 100 mm Tris-HCl, 1 mm DTT, 1 mm PMSF, pH7.6, including one-fold PhosSTOP phosphatase inhibitor mixture from Roche), and boiled for 15 min in water bath, and followed by 100 s of sonication. After centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, the protein in supernatant was quantified via BCA (bicinchoninic acid) method (30).

Protein Digestion with Prior Filter Aided Sample Preparation

Approximately 1.5 mg aliquot of dissolved protein for each sample was processed by the filter aided sample preparation method to remove SDS in the samples (31). Briefly, dithiothreitol (DTT) was added to the protein solution to reach 100 mm, and then boiled for 5 min. 25 μl aliquot of each sample was mixed with 200 μl UA buffer (8 m Urea, 150 mm Tris-HCl pH 8.0), loaded into a Microcon filtration devices (Millipore, with a MWCO of 10 kd), and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 15 min; 200 μl of fresh UA buffer was added to dilute the concentrate in the device and centrifuged again. The volume of concentrate was brought to 100 μl with UA buffer supplemented with 50 mm iodoacetamide (IAA) and the sample was shaken at 600 rpm for 1 min. After 30 min incubation at room temperature, the samples were diluted with 40 μl of digestion buffer (contains 5 μg of trypsin). The mixture was shaken at 600 rpm for 1 min, and incubated at 37 °C for 16–18 h. After digestion, the peptide solution was passed through a Microcon filtration device (MWCO 10 kd), and the concentration of the collected peptides was estimated based on their OD at 280 nm (32).

Eight-plex iTRAQ Labeling

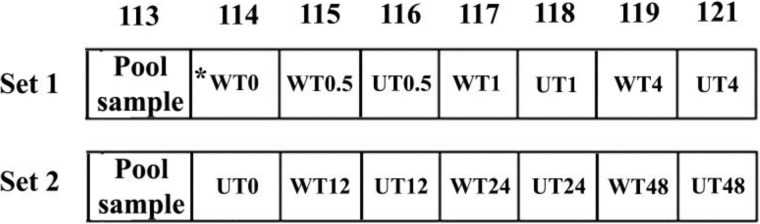

For every eight-plex set, a pooled sample was obtained by combing two groups of samples representing seven time points (a control and six salt treatments) from two cultivars (Union 85140 and Wenfeng07). These pooled samples serve as normalizing reference for the peptide content in samples from all the tested eight-plex sets. A 200 μg digested peptides of each sample was subjected to AB Sciex iTRAQ labeling (Fig. 1). The eight-plex iTRAQ labeling was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. A total of six eight-plex sets of iTRAQ samples were used for the three biological replicates.

Fig. 1.

Sample set of quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis. For each biological replication, two eight-plex iTRAQ sets were used for the seven time points (C, T0.5, T2, T4, T12, T24 and T48). A pool sample, combined equally with all the 14 samples, was included in each eight-plex iTRAQ set for normalization between different sets. *W: Wenfeng07; U: Union 85140; T0∼T48: Plant treated with 150 mm NaCl for 0 h, 0.5 h, 1 h, 4 h, 12 h, 24 h and 48 h.

Phosphopeptide Enrichment

Phosphopeptides were enriched using TiO2 beads as described by Ostasiewicz et al. (33) with minor changes. Labeled peptide solutions were lyophilized and acidified by dissolving into DHB buffer (3% 2, 5-DiHydroxyBenzoic acid, 80% ACN and 0.1% TFA). The 25 μg of TiO2 beads (10 μ in diameter, Sangon Biotech) were added to 50 μl peptide solution and spun down after 2 h incubation at room temperature. The pellets were packed into plastic tips (fit to 10 μl pipette), washed 3 times with 20 μl of wash solution 1 (20% acetic acid, 300 mm octanesulfonic acid sodium salt and 20 mg/ml DHB) then followed by three times with 20 μl wash solution 2 (70% water; 30% ACN). The enriched phosphopeptides were eluted using freshly prepared ABC buffer (50 mm ammonium phosphate, pH 10.5) and lyophilized for MS analysis.

NanoRPLC-MS/MS Analysis of Phosphorylated Peptides

The lyophilized phosphopeptides were subjected to capillary liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry using a two dimensional EASY-nLC1000 system coupled to a Q Exactive Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). In nanoLC separation system, mobile phase A solution contains 2% acetonitrile (ACN) and 0.1% formic acid in water, and mobile phase B solution contains 84% ACN and 0.1% formic acid. The Thermo EASY SC200 trap column (RP-C18, 3 μm, 100 mm × 75 μm) was pre-equilibrated with mobile phase A before peptides loading. The phosphopeptides were initially transferred to the SC001 column (150 μm × 20 mm, RP-C18) using 0.1% formic acid solution. The peptides were then separated via the trap column using a gradient of 0–55% mobile phase B for 220 min with a flow rate of 250 nL/min followed by a 8 min rinse with 100% of mobile phase B. The trap column was re-equilibrated to the initial conditions for 12 min. The MS data of each sample were acquired for 300–1800 m/z at the resolution of 70 k. The 20 most abundant ions from each MS scan were subsequently dissociated by higher energy collisional dissociation (HCD) in alternating data-dependent mode. The HCD generated MS/MS spectra were acquired with a resolution no less than 17,500.

Phosphopeptide Identification and Quantitative Analysis

The raw HCD files were analyzed by Mascot2.2 and Proteome Discoverer1.4 and searched against a peptide database derived from the Glycine max genome sequence (“uniprot_Glycine_74305_20140429.fasta” downloaded from http://www.uniprot.org/on April 29, 2014, which includes 74, 305 nonredundant predicted peptide sequences) (34). The Mascot search parameters were list in Table I. The Proteome Discoverer 1.4 was used for integrating the spectra intensity (> 200) of the eight-plex reporter ions. The quantitative value of phosphopeptides at different treatment time points was normalized using the pooled sample as a reference and converted to log2 value of fold-change. The phosphopeptides pass the cutoff and detected in at least two replicates were used for assessment of significant change in response to NaCl stress. In this research, two statistical approaches were used for significance analysis. The “significance A” value previously described by Cox and Mann (35) was adapted to evaluate the changes between the treated (samples) and untreated (control, T0) root tissues in each biological replicate with each of which includes three technical replicates. A Student's t test was performed using the standard deviation of the pooled sample (standard) between different biological replicates for assessing the global variability of all tested samples (29). The phosphopeptides that passed both Significance A < 0.05 and p value < 0.05 were considered significantly changed (36).

Table I. Parameters of mascot search.

| Type of search | MS/MS Ion search |

|---|---|

| Enzyme | Trypsin |

| Mass values | Monoisotopic |

| Max missed cleavages | 2 |

| Fixed modifications | Carbamidomethyl (C), Itraq8plex(N-term), iTRAQ8plex(K) |

| Variable modifications | Oxidation (M) |

| Peptide mass tolerance | ± 20 ppm |

| Fragment mass tolerance | 0.1 Da |

| Protein mass | Unrestricted |

| Database | Uniprot Glycine.fasta |

| Database pattern | Decoy |

| Peptide FDR | ≦ 0.01 |

Protein Shotgun Identifications by Thermo Scientific LTQ Velos

To construct a comprehensive database of salt responsive proteins in soybean, the LTQ Velos Mass Spectrometer coupled to Zorbax 300SB-C18 peptide traps (Agilent Technologies, Wilmington, DE), was used for protein identifications (37). In which, the analytical column is 0.15 mm × 150 mm (RP-C18) (Column Technology Inc., Fremont, CA). Each sample was analyzed three times and the peptides/proteins identified were combined and listed in supplemental Table S1 and S2.

2-DE Gel Based MALDI-TOF/TOF Mass Spectrometer Analysis for Protein Identification

0.2% (w/v) DTT and 0.5% IPG buffer (Lot No.: 17–6000-87, GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ) were added into the 200 μg samples before IEF. Total 250 μl samples containing about 200 μg proteins were applied to the dry IPG strips (13 cm, pH 3–10 nonlinear, GE healthcare). The program of IEF was as followed: rehydration at 20 °C for 12 h, 30 V for 8 h, 150 V for 2 h, 500 V for 0.5 h, 1000 V for 0.5 h, 4500 V for 4000 v·hrs, 8000 V for 66000 v·hrs. Focused strips were first equilibrated by incubating in equilibration buffer (pH 8.8, 2% (w:v) SDS, 6 m urea, 50 mm Tris-HCl, 30% glycerol (v:v) containing 1% DTT (w:v) for 15 min, followed by incubation in the abovementioned equilibration buffer containing 4% (w:v) iodoacetamide (IAA) for also 15 min. The second dimension separation was conducted on the 12% acrylamide SDS-PAGE. The PAGE gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue for over 2 h. Then, all these gels were captured by magic scanner with the same contrast and brightness. Sequentially, spots in these gel images were analyzed using ImageMasterTM 2D Platinum 5.0 software (GE Healthcare) and their relative volumes (% Vol) were represented as relative abundances. Each sample had at least two independent replicates and the differentially expressed protein spots' relative volumes were compared with Student's t test analysis (p ≤ 0.05). Spots with significant changes were excised out, and destained with 100 μl destaining solution combined with 25 mm ammonium bicarbonate and 50% (v: v) methanol in Milli-Q water. The gel crystals were dehydrated in 100% acetonitrile and vacuum-dried. Then, gel plugs were rehydrated with 10 μg/μl of trypsin in 25 mm ammonium bicarbonate on ice for 40 min and transferred into 30 °C incubator for 16–18 h digestion. Finally, 80% acetonitrile with 20% trifluoroacetic acid (v:v) was used to extracted digested peptides from the gels. MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometer 4700 Proteomics Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, USA) was applied to identify mass spectrometry of digested peptide. The MS scans were acquired among the mass range from m/z 700 to 3500 Da and the mass errors were less than 50 ppm. The MS precursor ions corresponding to porcine trypsin autolysis products (m/z 805.417, m/z 906.505, m/z 1153.574, m/z 2163.057, and m/z 2273.160) were excluded. All MS and MS/MS spectra were search via the MASCOT search engine against the soybean database (source: http://www.phytozome.net/soybean). The proteins were annotated against Uniprot database. The annotations were confirmed by comparison to the annotation of the top protein hits from the online blast search against the NCBI protein database.

Quantitative RT-PCR Analysis

RNA isolation, mRNA reverse transcription and qRT-PCR methods were performed as described by Wang et al. (38) with mini modifications. The root samples were frozen with liquid N2 and total RNAs were extracted with TRIZOL Reagent (Invitrogen). The genomic DNA was removed with DNase I and cDNA was synthesized using the Plant RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The primers were generated with NCBI online Primer-BLAST against the G. max genome (39). The soybean actin11 gene was used as a reference for normalization. Quantitative RT-PCR used SYBRTM Premix Ex Taq™ (TaKaRa, Shiga, Japan) and the reaction was conducted on a CFX96 System (Bio-Rad). The gene specific primers are listed in supplemental Table S3.

Bioinformatic Analysis

Peptide motifs were extracted using the motif-X algorithm (40). The width of the generated motifs was set as seven amino acids and serine or threonine was selected as the central amino. Gene oncology (GO) analysis was carried as described by Lv et al. (29). The cis-elements recognized by transcription factor binding were identified using JASPAR software (41, 42).

Scavenging Activity of the Superoxide Anion (O2−) Assay

This assay was based on the method of Zhang et al. (43) with slight modifications. Antioxidant enzymes were extracted with 10 ml of 0.05 m phosphate buffer (pH 5.5) from 0.5 g root homogenate. The extract was centrifuged at 12,000 × g (4 °C) for 10 min. 1 ml collected supernatant (crude enzyme extract) was added into 4 ml the reaction buffer, which was consist of 2 ml 0.05 m phosphate buffer, 1 ml 0.05 m guaiacol (substrate, overdose) and 1 ml 2% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). The increased absorbance at 470 nm due to the enzyme-dependent guaiacol oxidation was recorded every 30 S until the reaction time reached 4 min. The enzyme's radical scavenging activity (RSA) was defined as: RSA = (g/min), where w is the weight of fresh root (g), Vt is the volume of crude enzyme used in the reaction mixture (ml), Ve is the total volume of extracted crude enzyme (ml), Δt is the cost time of the reaction (min).

Free Radical Scavenging Activity on ABTS·+

The ABTS cationic radical (ABTS·+) decolorization assay was done by the method of Re et al. (44). ABTS·+ working solution was generated by adding 2.45 mm potassium persulphate (final concentration) to 7 mm ABTS (final concentration). This working solution was incubated in dark at room temperature for 12–16 h until it gave an absorbance of 0.70 ± 0.02 at 734 nm. Ten microliters of extracts were mixed with 1.0 ml of working ABTS·+ solution and incubated at 30 °C for 30 min and the absorbance of reaction mixture was measured at 734 nm. The enzyme's radical scavenging activity was expressed as: RSA = × Df × M0 (mm/g/min), where ΔOD is the reduced absorbance value, Δt is the reaction time (min), Df is the dilution factor, w is the weight of fresh root (g), M0 is the original ABTS·+ concentration.

Na+ and K+ Ion Content Analyses

Na+ and K+ ion contents were detected followed the methods proposed by Qi et al. (45) using the flame atomic absorption spectrophotometer (Shimadzu AA-6300C). The content was expressed as: milligram ion per gram fresh weight (mg/g FW).

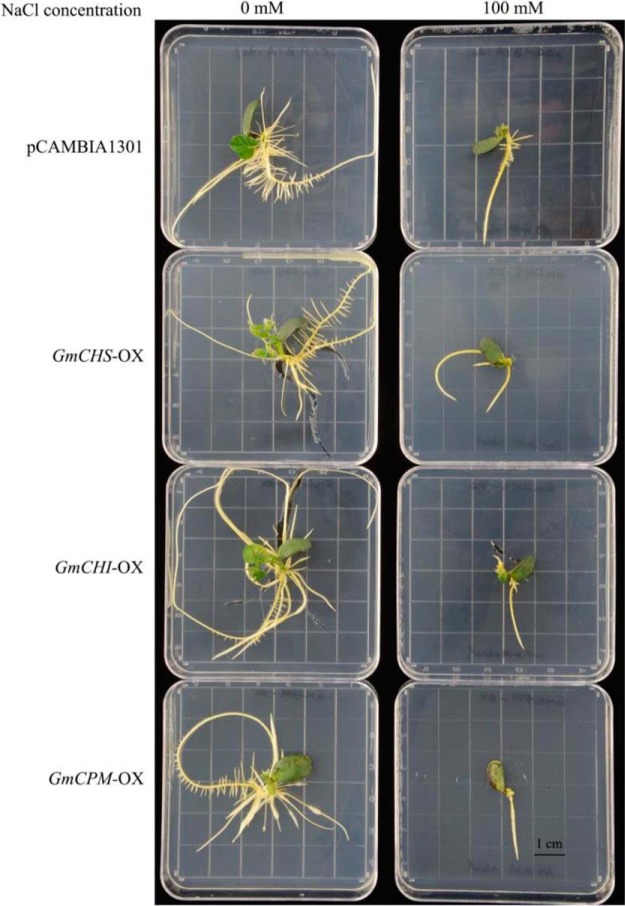

Gain-of-function Test of GmCHS, GmCHI, and GmCPM in Soybean Hairy Root System

The full-length CDSs of GmCHS (Glyma01g43880.1), GmCHI (Glyma04g40030.1), and GmCPM (Glyma07g14460.1) from Wenfeng07 was cloned into the pCAMBIA1301 vector between NcoI and BglII sites downstream of the 35S promoter. The original pCAMBIA1301 vector was used as a negative control. All these constructs were transformed into the salt-sensitive cultivar Union85140 via agrobacterium rhizogenes strain K599 as previously described (3). The composites were treated in 1/2 fold MS medium with 100 mm NaCl or without NaCl. The seedlings were weighted 10 days after salt treatment.

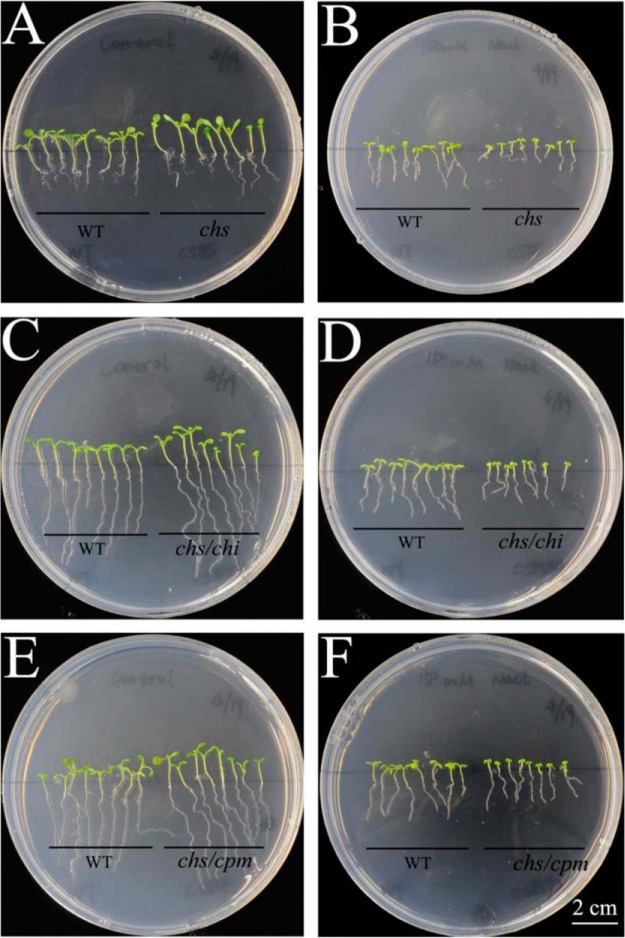

Loss-of-function Test of AtCHS, AtCHI and AtCPM in Arabidopsis thaliana

The seeds of deletion mutants chs, chs/chi, chs/cpm (Seed stock number: CS85, CS8584, CS8592) were got from ABRC (Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center) and germinated on 1/2 Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium. 5 days after germination, the seedlings were transferred to 1/2 MS medium with or without 150 mm NaCl. The photos of plants were taken 10 days after salt treatment.

RESULTS

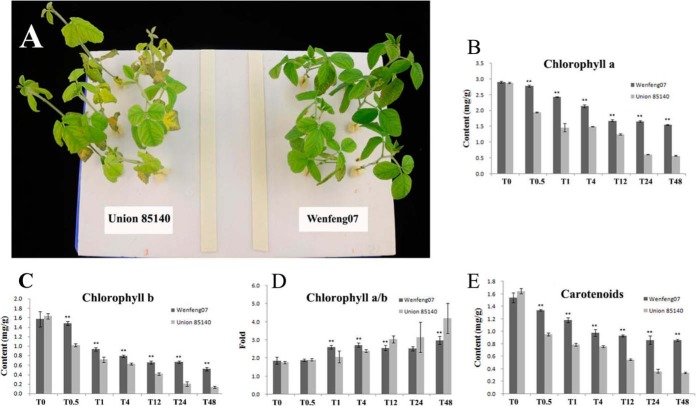

Salt stress is well known to cause leaf chlorosis by reducing chlorophyll a, b, and total chlorophyll content (46). After NaCl treatment, we found that the relative contents of chlorophyll a, b, and carotenoids in Union85140 decreased more than that in Wenfeng07 (Fig. 2). In addition, the chlorophyll a/b ratio in Union85140 increased less than that in Wenfeng07 at each time points. These results confirmed that Wenfeng07 is significantly more tolerant to salt stress than Union85140 at the physiological level.

Fig. 2.

Different tolerances of Wenfeng07 and Union85140 to salt stress. A, the cultivar Wenfeng07 showed significant stronger tolerance than Union85140. B–E, chlorophyll content analysis. Error bars represent standard error of three biological replicates.

ROS Elimination Capacity and Na+/K+ Content in Roots of the Two Soybean Cultivars

The antioxidant property in plant tissue is generally accepted to correlate with plant tolerance to various abiotic stresses including salinity, and it is usually represented by general radical scavenging capacities of peroxidases (POD), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), glutathione S-transferase (GST), and superoxide dismutase (SOD).

The antioxidant properties in salt-treated root tissue of the two cultivars were analyzed using H2O2 guaiacol, DPPH (2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) and ABTS (2, 2′ -azinobis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline 6-sulfonate)) radical scavenging capacity assays as previously described (47). As shown in Fig. 3A and 3B, there was no significant difference (p > 0.05) between Wenfeng07 and Union 85140 in their superoxide scavenging capacities under normal condition (T0). The scavenging capacities of the superoxide anion (SASA) in these two variants increased consistently at the early stage after salt-treatment (from 1.39 ± 0.03 g−1*min−1 in T0 to 4.87 ± 0.12 g−1*min−1 at time point T4). Starting from 4th hr (T4) of salt treatment, SASA values in these two cultivars were found to decline from their climaxes. Interestingly, SASA values in the salt-tolerant Wenfeng07 were shown to be higher than that in the salt-sensitive Union 85140 at the first four sampling times after salt treatment (from T0.5 to T12), but declined quicker and to a much lower level than that in Union 85140 24 h after the treatment. Similar to SASA, ABTS●+ scavenging potentials in the two tested cultivars displayed peak values at T1 after a short increase, then started to decrease in the rest of the stress treatment. Consistent with their salt tolerance, the ABTS●+ scavenging capability of Wenfeng07 were found to be significantly higher than that of Union 85140 (p < 0.05) all the time.

Fig. 3.

Measurement of physiological indices. A and B, analysis of ROS scavenger enzymes' activities. C and D, Na+ and K+ relative content analysis (mg per gram fresh wieght). Error bars represent standard error of three biological replicates.

In addition, the Na+ content and Na+/K+ ratio were compared in the two cultivars. Our results showed that, changes in Na+ content and the Na+/K+ ratio exhibited similar dynamic patterns at different time points in these two cultivars (Fig. 3C and 3D). The salt tolerant wenfeng07 accumulated higher level of Na+ (7.0671 ± 0.5495 mg/g FW) than the salt sensitive Union85140 (1.5189 ± 0.0026 mg/g FW) under control condition. The root Na+/K+ ratio in wenfeng07 (0.1829 ± 0.0143-fold) was also significantly higher than that in Union85140 (0.0350 ± 0.0001-fold). After treatment, two peak values of the root Na+ content were observed at time points T4 and T24 (Fig. 3C).

Protein Expression Profiles Revealed by LC-MS/MS

To obtain a comprehensive observation on soybean responses to salinity and to search for clues to the mechanistic differences resulting drastic difference in their tolerance, LC-MS/MS was used to analyze root samples of the two compared species of the soybean subjected to salt stress as described in the previous section. Results of three biological replicates are included in supplemental Tables S1 and S2, and major discoveries are summarized in Table II. A total of 46410 peptides out of 14702 proteins were identified from Wenfeng07 and 46710 peptides out of 14585 proteins from Union85140 (Table II). Of these, 4464 and 4409 nonredundant proteins were found from Wenfeng07 and Union85140 respectively.

Table II. The differential expressed proteins that were identified by LC-MSMS at different time-points.

| Control | T0.5 | T1 | T4 | T12 | T24 | T48 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wenfeng07 | Peptides | 2526 | 3209 | 4020 | 3610 | 3306 | 3394 | 3140 |

| Non-redundant peptides | 1427 | 1660 | 1979 | 1952 | 1790 | 1865 | 1747 | |

| Non-redundant protein | 1854 | 2055 | 2217 | 2146 | 2199 | 2115 | 2116 | |

| Union 85140 | Peptides | 2888 | 3575 | 3939 | 2809 | 3503 | 3311 | 3330 |

| Non-redundant peptides | 1611 | 1897 | 2048 | 1597 | 1868 | 1842 | 1885 | |

| Non-redundant protein | 1880 | 2160 | 2344 | 1902 | 2097 | 2171 | 2031 |

In total, there were 89 differential expressed proteins been identified by LC-MSMS between these two cultivars (Table III). In detail, 25 and 20 proteins were specifically detected in Wenfeng07 and Union85140 roots, respectively (Table III). Among the 25 proteins specifically presented in Wenfeng07, many of them including MYB transcription factors (TFs), ethylene-responsive transcription factor 6, chalcone synthase, cytochrome P450 monooxygenase CYP51G1, glutamate receptor and a PDR-like ABC-transporter were previously reported to be related with stress responses (23, 25, 29). Although among the 20 proteins specifically detected in Union85140, the auxin pathway related proteins (such as auxin response factor, auxin-induced protein AUX22 and PIN6a), drought stress responsive protein (KS-type dehydrin SLTI629) and many kinases (such as serine/threonine protein kinase and stress-induced receptor-like kinase 2), might contribute to its general response to salinity stress. Additionally, different homologs of a protein family presented differential expressions in the two varieties. For example, for eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3, the subunit F was expressed with higher abundance in Wenfeng07 roots, whereas the M subunit was expressed with higher abundance in Union85140 roots. Similar dynamics were found in hypersensitive induced reaction protein and nodulin proteins. In addition, the ascorbate peroxidase 2, GST 8, pathogenesis-related protein and two superoxide dismutases (I1LKZ3 and I1LR93) showed opposite trends in these two varieties—they were down-regulated in Wenfeng07, but up-regulated in Union85140.

Table III. The differential expressed proteins that were identified (LC-MSMS) between two variants. Note: “-” indicates no detectable signal been found in sample collected at this (these) time point(s); the amount of “+” shows the number of detectable signal(s) been found in sample collected at this (these) time point(s).

| Protein description | Accession No. | Soybean Gene IDs | Wenfeng07 |

Union 85140 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Stress | Control | Stress | |||

| 14-3-3 protein | Q8LJR3 | Glyma18g53610.1 | − | + | − | − |

| 2-hydroxyisoflavanone dehydratase | Q5NUF3 | Glyma01g45020.1 | − | + | − | +++++ |

| Alcohol-dehydrogenase | Q9ZT38 | Glyma04g41990.1 | − | − | − | + |

| ascorbate peroxidase 1 | Q76LA8 | Glyma11g15680.5 | − | ++++++ | + | ++++++ |

| ascorbate peroxidase 2 | Q39843 | Glyma12g07780.3 | + | − | − | + |

| Auxin response factor | K7KH37 | Glyma03g41920.2 | − | − | − | + |

| Auxin-induced protein AUX22 | P13088 | Glyma08g22190.1 | − | − | − | + |

| Catalase-1/2 | P29756 | Glyma17g38140.1 | − | ++++++ | + | +++++ |

| Catalase-3 | O48560 | Glyma14g39810.1 | − | ++++ | − | +++ |

| Chalcone isomerase 4B | Q53B71 | Glyma04g40030.1 | − | + | − | + |

| Chalcone synthase | Q6X0M9 | Glyma05g28610.2 | − | + | − | − |

| Chalcone synthase 1 | P24826 | Glyma08g11620.1 | − | + | − | − |

| Chalcone synthase 2 | P17957 | Glyma08g11630.2 | − | + | − | − |

| Chalcone synthase 3 | P19168 | Glyma08g11635.1 | − | + | − | − |

| Chalcone synthase 5 | P48406 | Glyma01g43880.1 | − | + | − | − |

| Chalcone synthase 7 | P30081 | Glyma08g11530.1 | − | +++ | + | + |

| Chalcone synthase 9 | B3F5J6 | Glyma08g11610.1 | − | + | − | − |

| Chalcone synthase CHS4 | Q6X0N0 | Glyma08g11520.1 | − | + | − | − |

| Chalcone-flavonone isomerase family protein | Q6X0M8 | Glyma01g22880.1 | − | + | − | − |

| Cytochrome P450 monooxygenase | Q2LAJ9 | Glyma07g14460.1 | − | + | − | − |

| Cytochrome P450 monooxygenase | Q2LAL0 | Glyma09g05440.1 | − | − | − | + |

| Ethylene-responsive transcription factor 6 | C6T283 | Glyma12g35550.1 | − | + | − | − |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 | I1JPD4 | Glyma03g32950.5 | − | ++ | − | +++ |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 | I1JK05 | Glyma03g00470.1 | − | ++ | − | ++ |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 | I1JQD9 | Glyma03g36470.1 | − | +++++ | − | ++ |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 | I1M228 | Glyma13g31200.1 | − | ++ | − | ++ |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 | C6TC72 | Glyma18g03340.1 | − | + | − | − |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 | I1KXJ9 | Glyma08g40110.1 | − | + | − | + |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 | C6TL4 | Glyma12g00510.1 | − | + | − | ++ |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 | I1L3W4 | Glyma09g29540.1 | − | + | − | + |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 | I1JUS7 | Glyma04g08570.1 | − | + | + | + |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 | C6TED0 | Glyma20g22090.1 | − | − | + | + |

| Ferritin Fer182 | I1MYZ9 | Glyma18g02800.2 | − | − | − | + |

| Glutamate receptor | I1KFC6 | Glyma06g46130.1 | − | + | − | − |

| Glutathione S-transferase GST 15 | Q9FQE3 | Glyma10g33650.1 | − | − | − | + |

| Glutathione S-transferase GST 24 | Q9FQD4 | Glyma14g03470.1 | − | − | − | ++ |

| Glutathione S-transferase GST 8 | Q9FQF0 | Glyma07g16910.1 | + | ++ | − | +++ |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | Q38IX0 | Glyma04g01750.1 | − | − | − | ++ |

| Heat shock protein 90–2 | B6EBD6 | Glyma14g01530.1 | − | +++++ | − | ++++ |

| Histone H2A OS | C6SV65 | Glyma19g42760.1 | + | ++++ | + | + |

| Hsp70-Hsp90 organizing protein 1 | Q43468 | Glyma17g14660.1 | − | + | − | + |

| Hypersensitive induced reaction protein 1 | G8FVT3 | Glyma19g02370.1 | − | − | − | ++ |

| Hypersensitive induced reaction protein 3 | G8FVT2 | Glyma05g01360.3 | − | − | + | ++ |

| Isoflavone reductase homolog 2 | Q9SDZ0 | Glyma04g01380.1 | − | +++++ | + | ++++++ |

| KS-type dehydrin SLTI629 | A9XE62 | Glyma19g29210.1 | − | − | − | + |

| Late-embryogenesis abundant protein 1 | C6TLT7 | Glyma14g04180.1 | − | ++++++ | + | ++++++ |

| Leucine-rich repeat family protein/protein kinase family protein | C6ZRY3 | Glyma10g08010.1 | − | − | − | ++ |

| Lysine–tRNA ligase | I1L9B1 | Glyma10g08040.1 | − | + | − | − |

| MATE efflux family protein | I1K9K1 | Glyma06g09550.1 | − | + | − | − |

| Mitochondrial phosphate transporter | O80412 | Glyma19g27380.2 | + | +++++ | + | ++++++ |

| Mitochondrial Rho GTPase | I1LBC8 | Glyma10g29580.1 | − | + | − | − |

| Mitogen-activated protein kinase 2 | Q5K6N6 | Glyma02g15690.2 | − | + | − | + |

| MYB transcription factor MYB107 | Q0PJJ3 | Glyma08g20270.1 | − | + | − | − |

| MYB transcription factor MYB130 | Q0PJG6 | Glyma01g40220.1 | − | + | − | − |

| MYB transcription factor MYB91 | Q0PJH2 | Glyma07g00930.1 | − | + | − | − |

| NAK-type protein kinase | C6ZRR4 | Glyma14g39290.1 | − | − | − | + |

| Nodulin 35 | Q9ZWU0 | Glyma10g23790.1 | − | ++ | − | − |

| Nodulin-44 | P04672 | Glyma13g44100.1 | − | − | − | + |

| Pathogenesis-related protein | C6SZ24 | Glyma17g03340.1 | + | +++++ | + | ++++++ |

| PDR-like ABC-transporter | Q1M2R7 | Glyma03g32520.1 | − | ++ | − | − |

| Peroxisomal ascorbate peroxidase | B0M196 | Glyma12g03610.1 | − | +++ | + | + |

| Phosphate transporter | Q8W198 | Glyma19g27380.2 | − | ++++++ | + | ++++++ |

| Phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase | Q43439 | Glyma02g42430.1 | − | + | − | ++ |

| Phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C | Q43443 | Glyma14g06450.1 | − | + | − | ++ |

| PIN6a | M9WP18 | Glyma14g27900.1 | − | − | − | + |

| Plamsma membrane-associated AAA- | Q2HZ34 | Glyma13g39830.1 | + | ++ | − | ++++ |

| Plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase | Q9FVE7 | Glyma06g04900.1 | − | + | − | − |

| PR10-like protein | C6T1G1 | Glyma05g38110.1 | − | ++ | + | ++++ |

| PR-5 protein | B6ZHC0 | Glyma01g42661.1 | − | ++ | + | ++ |

| Protein kinase Pti1 | C6TCB9 | Glyma10g44212.2 | − | +++ | − | ++ |

| Protein ROOT HAIR DEFECTIVE 3 | I1KGC2 | Glyma07g01230.1 | − | +++++ | + | ++++++ |

| Pti1 kinase-like protein | C6ZRP9 | Glyma17g04410.2 | − | + | − | − |

| Pto kinase interactor | C6ZRX5 | Glyma02g01150.1 | − | − | − | + |

| Putative chalcone isomerase 4 | Q53B72 | Glyma06g14820.1 | − | ++++++ | + | ++++++ |

| Putative receptor-like protein kinase 2 | Q49N12 | Glyma13g34100.1 | − | + | + | +++++ |

| Serine/threonine protein kinase | C6ZRR6 | Glyma19g40820.1 | − | + | − | + |

| Serine/threonine protein kinase | C6ZRT7 | Glyma20g38980.2 | − | + | − | ++ |

| Serine/threonine protein kinase | C6TDV2 | Glyma10g01200.1 | − | − | − | + |

| Somatic embryogenesis receptor-like kinase- | C6FF61 | Glyma08g19270.1 | − | − | − | + |

| Sterol 24-C methyltransferase 2–1 | D2D5G3 | Glyma04g02271.1 | − | + | − | − |

| Sterol 24-C methyltransferase 2–2 | D2D5G4 | Glyma06g02330.1 | − | + | − | − |

| Stress-induced protein SAM22 | P26987 | Glyma07g37240.2 | − | ++ | + | ++++ |

| Stress-induced receptor-like kinase 2 | B2ZNZ2 | Glyma15g02450.1 | − | − | − | + |

| Superoxide dismutase | I1JYA9 | Glyma04g39930.1 | − | ++ | + | ++ |

| Superoxide dismutase | I1LCI3 | Glyma10g33710.1 | − | +++++ | + | ++ |

| Superoxide dismutase [Cu-Zn] | I1LKZ3 | Glyma11g19840.3 | + | +++++ | − | +++++ |

| Superoxide dismutase [Cu-Zn] | I1LR93 | Glyma12g08650.1 | + | +++++ | − | +++++ |

| Superoxide dismutase [Cu-Zn] | I1LTN6 | Glyma12g30260.1 | − | ++++ | − | ++++ |

| Superoxide dismutase [Fe], chloroplastic | P28759 | Glyma20g33880.2 | + | +++++ | + | ++ |

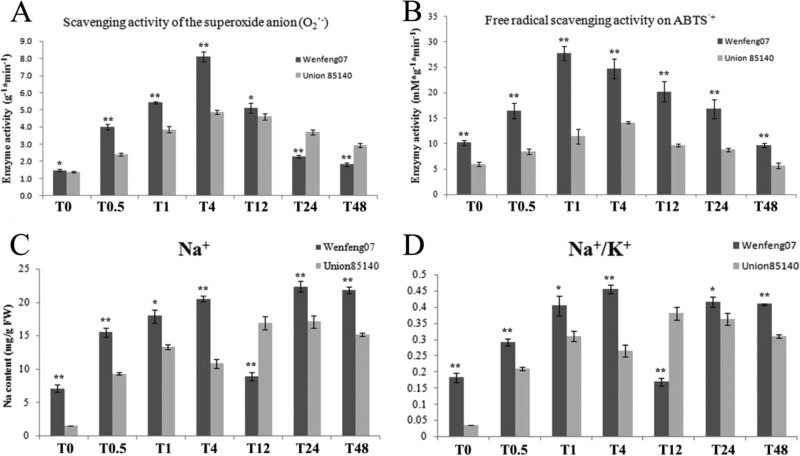

Transcriptional Expression Analysis of the Salt Responsive Genes

To explore the changes of abovementioned salt responsive proteins at the transcriptional level, 89 primer pairs of the genes encoding these proteins (supplemental Table S3) were synthesized for transcriptional-level analysis via quantitative RT-PCR. Among the 89 differentially expressed proteins, the transcriptional expression patterns of these genes in the salt treatment group were divided into three groups based on their differences between Wenfeng07 and Union85140 (Fig. 4). The first group (28 genes) had higher expression levels in Wenfeng07 than those in Union85140 at most time points, including genes encoding SOD (Glyma11g19840.2, Glyma12g08650.1, and Glyma04g39930.1), serine/threonine protein kinase (Glyma19g40820.1 and Glyma20g38980.2), MYB transcription factor MYB91 (Glyma07g00930.1), MYB transcription factor MYB107 (Glyma08g20270.1), GST 15 (Glyma10g33650.1), and cytochrome P450 monooxygenase (Glyma07g14460.1). The second group had lower expression levels in Wenfeng07 at most time points, with 39 genes encoding stress-induced receptor-like kinase (Glyma15g02450.1), sterol 24-C methyltransferase (Glyma04g02271.1 and Glyma08g19270.1), Pto kinase interactor (Glyma02g01150.1), protein kinase Pti1 (Glyma10g44212.2), PR10-like protein (Glyma05g38110.1), phosphate transporter (Glyma19g27380.2), MYB transcription factor MYB130 (Glyma01g40220.1), and hypersensitive induced reaction protein (Glyma05g01360.3). The remaining 22 genes were in the third group, among which the gene transcriptional expressions were mostly higher at T1 and T4 in Wenfeng07 but lower at other time points, such as chalcone isomerase (Glyma06g14820.1 and Glyma04g40030.1). Generally, the protein-encoding genes involved in the chalcone metabolism pathway (chalcone synthase, chalcone isomerase, and cytochrome P450 monooxygenase) showed higher expression levels in Wenfeng07. Members of the GmMYB TF family were differentially activated in the two cultivars.

Fig. 4.

Clustering heat map of differentially expressed proteins. Each column represents a time point of NaCl concentration. The color codes represent the average values of three biological replicates. The abbreviations of gene names were listed in supplemental Table S3.

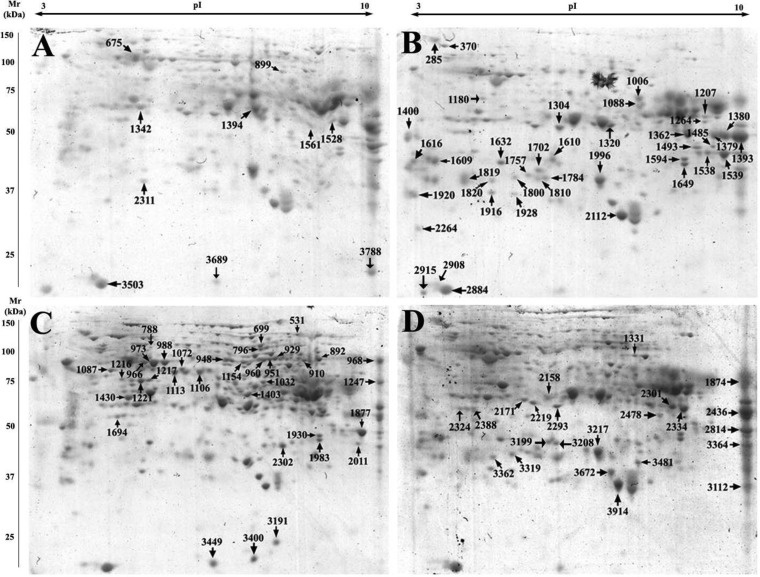

2-DE Mapping and Identification of Differentially Expressed Proteins

The 2-DE MS/MS strategy was applied to visualize and quantitatively analyze the defense-related proteins in the roots of two soybean varieties at times T0 and T4. The results showed that 115 protein spots (including 90 nonredundant proteins) of about 900 reproducible spots, demonstrated significant changes between T4 and T0 and were successfully identified using MALDI-TOF/TOF-MS (Table IV and V). In particular, 46 differentially expressed proteins were identified from Wenfeng07 and 69 proteins from Union85140 (Fig. 5 and supplemental Fig. S1, Table IV and V).

Table IV. Differentially expressed proteins in Wenfeng07 under the salinity stress.

| Spots No. | Protein No. | Protein description | Theoretial MW/pI | Matched peptide | Protein score | CI% | Changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 675 | Glyma10g33680.1 | chaperonin CPN60–2, mitochondrial-like isoform 1 | 61393.4/5.75 | 15 | 116 | 100 | Down |

| 3689 | Glyma10g39780.7 | ubiquitin 11 | 17168.2/6.75 | 5 | 177 | 100 | Down |

| 1342 | Glyma13g41960.1 | fructokinase-2-like | 35375.4/5.29 | 19 | 356 | 100 | Down |

| 1304/1394 | Glyma04g01380.1 | isoflavone reductase homolog 2 | 33918.7/5.6 | 14 | 273 | 100 | Down/down |

| 1528/1561 | Glyma09g02800.1 | Ferrodoxin NADP oxidoreductase | 42241.3/8.38 | 15 | 223 | 100 | Down/down |

| 2908/3503/2844 | Glyma17g03350.1 | stress-induced protein SAM22 | 16746.6/4.93 | 13 | 325 | 100 | Down/up |

| 1320 | gi 62546339 | PIP2,2 | 30750.91/8.26 | 9 | 230 | 100 | Up |

| 1180 | Glyma01g01180.1 | malic enzyme/malate dehydrogenase (NADP+) | 64985.8/5.83 | 6 | 100 | 100 | Up |

| 2170 | Glyma03g05480.1 | disease resistance response protein 206-like | 22015.6/9.88 | 6 | 92 | 100 | Up |

| 1466 | Glyma03g23890.1 | NADP-dependent alkenal double bond reductase P1-like | 37896.5/5.94 | 13 | 214 | 100 | Up |

| 1819 | Glyma03g26060.1 | stellacyanin-like | 19158.2/5.14 | 3 | 68 | 99.97 | Up |

| 1485 | Glyma04g16350.2 | prohibitin-1, mitochondrial-like isoform 1 | 30373/7.93 | 17 | 231 | 100 | Up |

| 1616 | Glyma04g37120.1 | elongation factor 1-delta-like | 24972.7/4.42 | 8 | 190 | 100 | Up |

| 1400 | Glyma04g40550.2 | nascent polypeptide-associated complex subunit alpha-like protein 2-like | 14753.6/5.04 | 7 | 236 | 100 | Up |

| 1702 | Glyma06g39710.1 | proteasome subunit alpha type-6 | 27366.9/5.58 | 16 | 309 | 100 | Up |

| 1493 | Glyma06g47520.1 | prohibitin-1, mitochondrial-like | 30300.9/7.96 | 18 | 399 | 100 | Up |

| 1632 | Glyma07g33780.1 | caffeoyl-CoA O-methyltransferase-like | 28053.4/5.46 | 14 | 295 | 100 | Up |

| 899 | Glyma08g02100.2 | monodehydroascorbate reductase, chloroplastic-like | 52130.1/8.36 | 12 | 169 | 100 | Up |

| 1800 | Glyma08g17810.4 | proteasome subunit alpha type-2-A-like | 25562.2/5.51 | 12 | 163 | 100 | Up |

| 1538 | Glyma08g24950.1 | prohibitin-1, mitochondrial-like | 30462.1/7.96 | 14 | 148 | 100 | Up |

| 1594 | Glyma08g40800.1 | mitochondrial outer membrane protein porin of 36 kDa-like | 29786.4/7.07 | 14 | 219 | 100 | Up |

| 2915 | Glyma09g04530.1 | ABA-responsive protein ABR17 | 16522.5/4.68 | 8 | 156 | 100 | Up |

| 1916 | Glyma09g08340.1 | groes chaperonin, putative | 26640.2/6.77 | 18 | 310 | 100 | Up |

| 1264 | Glyma11g33560.1 | cytosolic glutamine synthetase GSbeta1 | 38966.5/5.48 | 13 | 274 | 100 | Up |

| 1264 | Glyma12g00430.1 | putative quinone-oxidoreductase homolog, chloroplastic-like | 34810.4/8.27 | 12 | 149 | 100 | Up |

| 1820 | Glyma12g31850.3 | protein usf-like | 26332.2/5.38 | 10 | 104 | 100 | Up |

| 2112 | Glyma13g32300.1 | flavoprotein wrbA-like | 21653/6.43 | 10 | 442 | 100 | Up |

| 285 | Glyma13g40130.1 | protein disulfide isomerase-like 1–4-like isoform 1 | 62343.4/4.72 | 15 | 165 | 100 | Up |

| 1920 | Glyma14g09440.1 | cysteine proteinase RD21a-like | 50977.4/5.37 | 11 | 200 | 100 | Up |

| 1207 | Glyma14g36850.1 | fructose-bisphosphate aldolase, cytoplasmic isozyme-like | 38330/7.12 | 11 | 145 | 100 | Up |

| 1610 | Glyma14g40670.2 | cysteine proteinase 15A-like | 40216.1/6.82 | 8 | 216 | 100 | Up |

| 1362 | Glyma15g15200.1 | glucan endo-1,3-beta-glucosidase, basic isoform-like | 43758.5/8.75 | 11 | 447 | 100 | Up |

| 1928 | Glyma15g19970.1 | 20 kDa chaperonin, chloroplastic-like | 26653.2/7.79 | 10 | 108 | 100 | Up |

| 370 | Glyma16g00410.1 | stromal 70 kDa heat shock-related protein, chloroplastic-like | 73709.4/5.2 | 19 | 230 | 100 | Up |

| 2264 | Glyma16g33710.1 | Kunitz trypsin protease inhibitor-like precursor | 23640.1/5.17 | 6 | 172 | 100 | Up |

| 1609 | Glyma17g35720.1 | cysteine proteinase RD21a-like | 52082/5.55 | 12 | 413 | 100 | Up |

| 1649 | Glyma18g16260.1 | mitochondrial outer membrane protein porin of 36 kDa-like | 29814.4/7.88 | 17 | 254 | 100 | Up |

| 3788 | Glyma19g42760.1 | Histone H2A OS | 14684/10.36 | 6 | 329 | 100 | Down |

| 1996 | Glyma20g38560.1 | chalcone flavonone isomerase | 23250.2/6.23 | 16 | 432 | 100 | Up |

| 1303/1314 | Glyma17g02260.1 | copper amino oxidase | 75776/6.21 | 14 | 147 | 100 | Up/down |

| 1379/1784 | Glyma03g28850.1 | glucan endo-1,3-beta-glucosidase precursor | 38088.3/8.72 | 18 | 510 | 100 | Up/up |

| 1380/1393 | Glyma05g22180.1 | peroxidase 73-like | 35475/9.03 | 12 | 245 | 100 | Up/up |

| 1539/1941 | Glyma09g37570.1 | peroxisomal voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein | 29737.6/8.57 | 14 | 351 | 100 | Up/Up |

| 1757/1810 | Glyma12g07780.2 | ascorbate peroxidase 2 | 27108.8/5.65 | 15 | 262 | 100 | Up/Down |

| 1006/1088 | Glyma12g32160.1 | peroxidase 39-like | 35644.1/7.12 | 9 | 214 | 100 | Up/Up |

| 2155/2168 | Glyma15g41550.1 | cytosolic phosphoglycerate kinase | 42408.6/5.96 | 10 | 103 | 100 | Up/Up |

Table V. Differentially expressed proteins in Union85140 under the salinity stress.

| Spots No. | Protein ID | Protein description | Theoretial MW/pI | Matched peptide | Protein score | CI% | Changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 796 | Glyma02g44080.1 | T-complex protein 1 subunit eta-like | 60234.2/6.19 | 9 | 130 | 100 | Down |

| 988 | Glyma03g34830.1 | enolase-like | 47628.4/5.49 | 19 | 473 | 100 | Down |

| 1072 | Glyma03g38190.2 | S-adenosylmethionine synthase 1-like isoform 1 | 43196.7/5.57 | 13 | 205 | 100 | Down |

| 1221 | Glyma04g39380.2 | actin-7-like | 41688.9/5.31 | 15 | 214 | 100 | Down |

| 968 | Glyma05g24110.1 | elongation factor 1-alpha-like isoform 1 | 49232.7/9.15 | 6 | 54 | 81.467 | Down |

| 910 | Glyma05g28490.1 | serine hydroxymethyltransferase 2 | 51686.1/6.9 | 11 | 152 | 100 | Down |

| 1217 | Glyma05g32220.2 | actin-7-like | 41711.9/5.37 | 14 | 228 | 100 | Down |

| 1216 | Glyma06g15520.2 | actin-7-like | 37069.6/5.38 | 8 | 92 | 99.995 | Down |

| 948 | Glyma07g30210.1 | methylmalonate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase [acylating], mitochondrial-like | 57578.5/6.53 | 15 | 139 | 100 | Down |

| 699 | Glyma07g33570.1 | ferredoxin-nitrite reductase, chloroplastic-like | 65836.6/6.47 | 23 | 271 | 100 | Down |

| 960 | Glyma07g36040.1 | ferric leghemoglobin reductase-2 precursor | 52968.7/6.9 | 14 | 152 | 100 | Down |

| 1210 | Glyma08g03120.1 | biotin carboxylase precursor | 58770.2/7.22 | 20 | 194 | 100 | Down |

| 892 | Glyma08g11490.2 | serine hydroxymethyltransferase 2 | 51733.2/7.59 | 18 | 294 | 100 | Down |

| 1154 | Glyma08g17490.1 | probable inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase | 35562.5/7.68 | 11 | 136 | 100 | Down |

| 3400 | Glyma08g24760.1 | ripening related protein | 17750.8/5.96 | 11 | 229 | 100 | Down |

| 1486 | Glyma08g24950.1 | prohibitin-1, mitochondrial-like | 30462.1/7.96 | 14 | 145 | 100 | Down |

| 1930 | Glyma08g40800.1 | mitochondrial outer membrane protein porin of 36 kDa-like | 29786.4/7.07 | 13 | 184 | 100 | Down |

| 951 | Glyma10g29600.1 | seryl-tRNA synthetase-like | 51333.1/6.03 | 11 | 76 | 99.81 | Down |

| 2302 | Glyma11g07540.1 | Transcription factor APFI-like protein | 29247.9/6.36 | 10 | 119 | 100 | Down |

| 1334 | Glyma11g08920.1 | isocitrate dehydrogenase | 39315.3/6.47 | 11 | 140 | 100 | Down |

| 1106 | Glyma1337s00200.1 | S-adenosylmethionine synthase-like | 43027.7/5.65 | 17 | 391 | 100 | Down |

| 2011 | Glyma13g01040.2 | Mitochondrial outer membrane protein porin | 29738.2/8.66 | 9 | 87 | 99.984 | Down |

| 2222 | Glyma13g32300.2 | flavoprotein wrbA-like | 21112.7/6.09 | 7 | 66 | 98.052 | Down |

| 574 | Glyma13g41370.1 | protein TOC75–3, chloroplastic-like | 87454/7.29 | 22 | 236 | 100 | Down |

| 1263/2324/2388 | Glyma13g41960.1 | fructokinase 2 | 35375.4/5.29 | 17 | 272 | 100 | Down |

| 1032 | Glyma14g02530.3 | dihydrolipoyllysine-residue succinyltransferase component of 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex 2, mitochondrial-like | 50131.5/9.17 | 10 | 128 | 100 | Down |

| 3449 | Glyma15g13140.1 | actin-depolymerizing factor 2-like | 10414.2/5.65 | 6 | 215 | 100 | Down |

| 1113 | Glyma15g21890.2 | S-adenosylmethionine synthase-like isoform 1 | 43025.8/5.5 | 22 | 472 | 100 | Down |

| 3191 | Glyma15g31520.1 | ripening related protein | 21494.8/6.29 | 10 | 148 | 100 | Down |

| 929 | Glyma17g04210.1 | dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase, mitochondrial-like | 52854.5/6.9 | 13 | 148 | 100 | Down |

| 531 | Glyma17g35890.1 | polyadenylate-binding protein 2-like | 71880/5.7 | 12 | 120 | 100 | Down |

| 1694 | Glyma17g37050.1 | proteasome subunit alpha type-1-A-like isoform 1 | 30956.4/5.07 | 12 | 183 | 100 | Down |

| 1983 | Glyma18g16260.1 | mitochondrial outer membrane protein porin of 36 kDa-like | 29814.4/7.88 | 16 | 264 | 100 | Down |

| 973 | Glyma19g37520.1 | enolase | 47643.4/5.4 | 20 | 507 | 100 | Down |

| 439 | Glyma20g19980.1 | chaperonin CPN60–2, mitochondrial-like isoform 1 | 60983.3/6.38 | 12 | 83 | 99.965 | Down |

| 1087 | Glyma20g38030.1 | 26S protease regulatory subunit 6A homolog A-like | 47425.4/4.98 | 23 | 331 | 100 | Down |

| 1527/1535/1544/1877/2814 | Glyma09g37570.1 | peroxisomal voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein | 29737.6/8.57 | 11 | 320 | 100 | Down/up/down/down/up |

| 1229 | Glyma02g46380.2 | pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component subunit beta, mitochondrial-like | 38696.8/5.7 | 11 | 127 | 100 | Up |

| 3364 | Glyma03g05480.1 | disease resistance response protein 206-like | 22015.6/9.88 | 7 | 122 | 100 | Up |

| 1402 | Glyma03g23890.1 | NADP-dependent alkenal double bond reductase P1-like | 37896.5/5.94 | 11 | 249 | 100 | Up |

| 3112 | Glyma03g38630.1 | germin-like protein 1 | 22832.2/9.06 | 5 | 180 | 100 | Up |

| 675 | Glyma04g01220.1 | phosphatidylinositol transfer-like protein III | 70795.2/8.44 | 12 | 57 | 83.799 | Up |

| 2219/2293 | Glyma04g01380.1 | isoflavone reductase homolog 2 | 33918.7/5.6 | 16 | 347 | 100 | Up |

| 2436 | Glyma05g22180.1 | peroxidase 73-like | 35475/9.03 | 10 | 229 | 100 | Up |

| 3481 | Glyma05g38160.1 | Protein yrdA, putative | 27715.5/8.34 | 12 | 157 | 100 | Up |

| 1151 | Glyma06g12780.3 | alcohol dehydrogenase 1-like | 36891.4/5.77 | 16 | 357 | 100 | Up |

| 2158 | Glyma07g33780.1 | caffeoyl-CoA O-methyltransferase-like | 28053.4/5.46 | 10 | 140 | 100 | Up |

| 3103 | Glyma07g37250.2 | Stress-induced protein SAM22 | 15524.9/4.74 | 8 | 228 | 100 | Up |

| 3319 | Glyma08g17810.4 | proteasome subunit alpha type-2-A-like | 25562.2/5.51 | 11 | 216 | 100 | Up |

| 788 | Glyma09g40690.1 | 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate-independent phosphoglycerate mutase | 60831/5.51 | 7 | 182 | 100 | Up |

| 697 | Glyma10g41330.2 | ATP synthase subunit beta, mitochondrial-like | 58664.8/8.83 | 18 | 479 | 100 | Up |

| 1438 | Glyma11g07490.1 | isoflavone reductase homolog A622-like | 33978.9/6.12 | 12 | 187 | 100 | Up |

| 1160 | Glyma11g33560.1 | cytosolic glutamine synthetase GSbeta1 | 38966.5/5.48 | 11 | 194 | 100 | Up |

| 1978 | Glyma11g34380.2 | tropinone reductase homolog At1g07440 | 29159.8/7.56 | 9 | 164 | 100 | Up |

| 3362 | Glyma12g31850.3 | protein usf-like | 26332.2/5.38 | 6 | 74 | 99.731 | Up |

| 3914 | Glyma13g32300.1 | flavoprotein wrbA-like | 21653/6.43 | 8 | 325 | 100 | Up |

| 2478 | Glyma14g36850.1 | fructose-bisphosphate aldolase, cytoplasmic isozyme-like | 38330/7.12 | 14 | 201 | 100 | Up |

| 3217 | Glyma15g04290.1 | triosephosphate isomerase, cytosolic-like | 27181.1/5.87 | 16 | 494 | 100 | Up |

| 1874 | Glyma15g13550.1 | peroxidase C3-like isoform 1 | 38103.7/8.62 | 6 | 108 | 100 | Up |

| 2301 | Glyma15g13680.1 | Ferredoxin–NADP reductase, root isozyme, chloroplastic | 42164.3/8.52 | 12 | 174 | 100 | Up |

| 2334 | Glyma15g15200.1 | glucan endo-1,3-beta-glucosidase, basic isoform-like | 43758.5/8.75 | 13 | 468 | 100 | Up |

| 1936 | Glyma15g27660.1 | alpha-amylase/subtilisin inhibitor-like isoform 1 | 23521.5/4.77 | 9 | 137 | 100 | Up |

| 2171 | Glyma17g10880.3 | malate dehydrogenase, chloroplastic-like | 43120.4/8.11 | 11 | 185 | 100 | Up |

| 2109 | Glyma17g15690.1 | expansin-like B1-like | 27650.4/6.3 | 7 | 229 | 100 | Up |

| 3672 | Glyma20g38560.1 | chalcone flavonone isomerase | 23250.2/6.23 | 16 | 456 | 100 | Up |

| 1218/1388 | Glyma12g32160.1 | peroxidase precursor | 35644.1/7.12 | 13 | 226 | 100 | Up/up |

| 969/970/1276 | Glyma09g01270.2 | fumarylacetoacetase-like | 40512.1/6.49 | 14 | 197 | 100 | Up/Up/down |

| 3199/3208 | Glyma02g40820.1 | isocitrate dehydrogenase (NADP) (EC 1.1.1.42) | 46050.5/5.87 | 18 | 156 | 100 | Up/up/up |

| 1979/1983/2133 | Glyma06g18110.7 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 36662/8.30 | 3 | 199 | 100 | Up/up/up |

Fig. 5.

Different expressed proteins in Wenfeng07 and Union85140 identified by 2-D MS/MS under salinity stress (at time points T0 and T4). SDS-PAGE gels were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue; A and B, 2-D maps of root proteome of Wenfeng07 at time points T0 and T4, respectively; C and D, 2-D maps of root proteome of Union85140 at time points T0 and T4, respectively.

The results showed that the chalcone flavonone isomerase/chalcone isomerase was also up-regulated in both Wenfeng07 and Union85140, supporting the LC-MS/MS observations. Interestingly, the ascorbate peroxidase 2 (APX2) protein showed two different isoelectric points (Spots 1757 and 1810 in Fig. 5) in Wenfeng07 roots. In addition, Spot 1757 was up-regulated whereas Spot 1810 was down-regulated. Similarly, the stress-induced protein SAM22 and copper amino oxidase proteins also had two different isoelectric points and different mass weights. These two proteins showed opposite down/up change trends after salt treatment in Wenfeng07. In Union85140, the peroxisomal voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein, fumarylacetoacetase-like, isocitrate dehydrogenase (NADP) (EC 1.1.1.42) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase protein showed three or more spots in the 2-DE gels. Altogether, 14 nonredundant proteins were identified from two or three DEP spots with different isoelectric points and/or molecular weights in the two soybean varieties (Table VI). This implied that the isoforms of the abovementioned proteins might play significant roles in the two varieties.

Table VI. Differential expressed proteins identified with two or more spots on 2-DE gels. *W: Wenfeng07; U: Union 85140.

| Uniprot accession No. | Protein description | IDs on 2D gel | Theoretial MW/pI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q9ZNZ6 | peroxidase precursor | 1218/1388 | 35644.1/7.12 |

| I1LU76 | peroxidase 39-like | 1006/1088 | 35644.1/7.12 |

| I1MRA7 | copper amino oxidase; diamine oxidase | 1303/1314 | 75776/6.21 |

| I1MJC7 | cytosolic phosphoglycerate kinase | 2155/2168 | 42408.6/5.96 |

| C6T8Y4 | Ferrodoxin NADP oxidoreductase | 1528/1561 | 42241.3/8.38 |

| I1M561 | fructokinase 2 | 1263/2324/2388 | 35375.4/5.29 |

| I1KZY9 | fumarylacetoacetase-like | 969/970 | 40512.1/6.49 |

| C6TL98 | glucan endo-1,3-beta-glucosidase precursor | 1379/1784 | 38088.3/8.72 |

| C6T857 | isocitrate dehydrogenase (NADP) (EC1.1.1.42) | 3199/3208 | 46050.5/5.87 |

| Q9SDZ0 | isoflavone reductase homolog 2 | 2219/2293 | 33918.7/5.6 |

| Q39843 | l-ascorbate peroxidase 2 | 1757/1810 | 27108.8/5.65 |

| C6THQ0 | peroxidase 73-like | 1380/1393 | 35475/9.03 |

| I1L602 | peroxisomal voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein | 1527/1535/1544/1539/1877/1941/2814 | 29737.6/8.57 |

| Q43453 | stress-induced protein SAM22 | 2908/3503 | 16746.6/4.93 |

Phosphopeptide Identification and Quantitative Analysis

The intensity of each phosphopeptide was normalized to the mean of intensities of all phosphopeptides within each biological replicate. Subsequently, the log2 intensity value changes (salt stress time point Tx/T0) in each condition were calculated for each phosphopeptide (supplemental Table S4). The Student's t test (p values) was performed using the standard deviation of the pooled sample (standard) between different biological replicates for assessing the global variability of all tested samples (supplemental Table S4).

In total, 5509 phosphorylated sites corresponding to 2692 phosphoproteins were identified (supplemental Tables S4 and S5), and 2344 phosphoproteins containing 3744 phosphorylation sites were quantitatively analyzed. Of these, 34.04% of phosphopeptides were detected in all three biological replicates, and 24.29% in two biological replicates (Fig. S2A). In addition, 31.41% of phosphoproteins were detected in all three biological replicates, and 24.97% in two biological replicates (supplemental Fig. S2B). Besides, there were 673 protein, which were found by LC-MSMS approaches (supplemental Tables S1 and S2), been also identified as phosphoproteins (supplemental Tables S4 and S5).

Identification of Differentially Expressed Proteins with Phosphorylation Sites

Among the 179 differentially expressed nonredundant proteins (89 nonredundant proteins from LC-MS/MS and 90 nonredundant proteins from 2-DE MS/MS), 16 proteins were also identified as phosphoproteins (Table VII, Fig. 5 and supplemental Fig. S1), such as PIP2,2 (Uniprot accession No. C6TBC3), stress-induced protein SAM22 (Uniprot accession no. Q43453), histone H2A OS (Uniprot accession no. C6SV65), eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit C (Uniprot accession no. I1JQD9) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase cytosolic-like (Uniprot accession no. I1KC70). These phosphoproteins were involved in signal transduction, chromosome remodeling, gene translation, and energy metabolism (10–14, 29).

Table VII. Differential expressed proteins identified with reliable phosphorylated sites.

| Protein No. | Uniprot accession No. | Protein description | Phosphorylated peptide | Phosphorylated site (probabilities) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glyma09g40690.1 | I1L6W0 | 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate-independent phosphoglycerate mutase | AHGTAVGLPTEDDMGNSEVGHNALGAGR/AHGTAVGLPTEDDMGNSEVGHNALGAGR | T(4): 0.0; T(10): 0.0; S(17): 100.0/T(4): 0.0; T(10): 95.9; S(17): 4.1 |

| Glyma01g45020.1 | Q5NUF3 | 2-hydroxyisoflavanone dehydratase | LLSSENVAASPEDPQTGVSSK | S(3): 0.0; S(4): 0.0; S(10): 100.0; T(16): 0.0; S(19): 0.0; S(20): 0.0 |

| Glyma06g12780.3 | C6TD82 | alcohol dehydrogenase 1-like | IIGVDLVSSR | S(8): 100.0; S(9): 0.0 |

| Glyma11g33560.1 | C6TJN5 | cytosolic glutamine synthetase GSbeta1 | WNYDGSSTGQAPGEDSEVIIYPQAIFR | Y(3): 0.0; S(6): 33.3; S(7): 33.3; T(8): 33.3; S(16): 0.0; Y(21): 0.0 |

| Glyma11g33560.1 | C6TJN5 | cytosolic glutamine synthetase GSbeta1 | WNYDGSSTGQAPGEDSEVIIYPQAIFR | Y(3): 0.0; S(6): 33.3; S(7): 33.3; T(8): 33.3; S(16): 0.0; Y(21): 0.0 |

| Glyma04g37120.1 | C6SXP1 | elongation factor 1-delta-like | AAVAEDDDDDDVDLFGEETEEEK | T(19): 100.0 |

| Glyma03g36470.1 | I1JQD9 | eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit C | YFVDNASDSDDSDGQK/SDSEASQYDNEK | Y(1): 0.0; S(7): 100.0; S(9): 100.0; S(12): 100.0/S(1): 100.0; S(3): 0.0; S(6): 0.0; Y(8): 0.0 |

| Glyma14g36850.1 | C6TMG1 | fructose-bisphosphate aldolase, cytoplasmic isozyme-like | LASISVENVESNR/LADGASESLHVEDYK/GILAADESTGTIGK | S(3): 98.5; S(5): 1.5; S(11): 0.0/S(6): 0.1; S(8): 99.9; Y(14): 0.0/S(8): 98.3; T(9): 1.7; T(11): 0.0 |

| Glyma06g18110.7 | I1KC70 | glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, cytosolic-like | EASYDEIK | S(3): 98.9; Y(4): 1.1 |

| Glyma19g42760.1 | C6SV65 | histone H2A OS | GEIGSASQEF | S(5): 0.0; S(7): 100.0 |

| Glyma19g29210.1 | A9XE62 | KS-type dehydrin SLTI629 | EHGHEHGHDSSSSSDSD/EHGHEHGHDSSSSSDSD/EHGHEHGHDSSSSSDSD | S(10): 32.9; S(11): 32.9; S(12): 32.9; S(13): 0.6; S(14): 0.6; S(16): 0.0/S(10): 91.0; S(11): 8.3; S(12): 4.5; S(13): 0.5; S(14): 4.7; S(16): 91.0/S(10): 0.5; S(11): 0.5; S(12): 67.0; S(13): 67.0; S(14): 67.0; S(16): 98.1 |

| Glyma10g08010.1 | C6ZRY3 | leucine-rich repeat family protein/protein kinase family protein | EEDFSYSGIFPSTR/SSELNPFANWEQNTNSGTAPQLK | S(5): 0.0; Y(6): 0.0; S(7): 0.0; S(12): 98.3; T(13): 1.7/S(1): 0.0; S(2): 0.0; T(14): 33.3; S(16): 33.3; T(18): 33.3 |

| Glyma01g01180.3 | I1J4J8 | malic enzyme OS | IWLVDSK | S(6): 100.0 |

| Glyma14g39290.1 | C6ZRR4 | NAK-type protein kinase | VQSPNALVIHPR | S(3): 100.0 |

| gi 62546339 | C6TBC3 | PIP2,2 | DVEQVTEQGEYSAK | T(6): 0.0; Y(11): 1.1; S(12): 98.9 |

| Glyma17g03350.1 | Q43453 | stress-induced protein SAM22 | SVENLEGNGGPGTIK | S(1): 100.0; T(13): 0.0 |

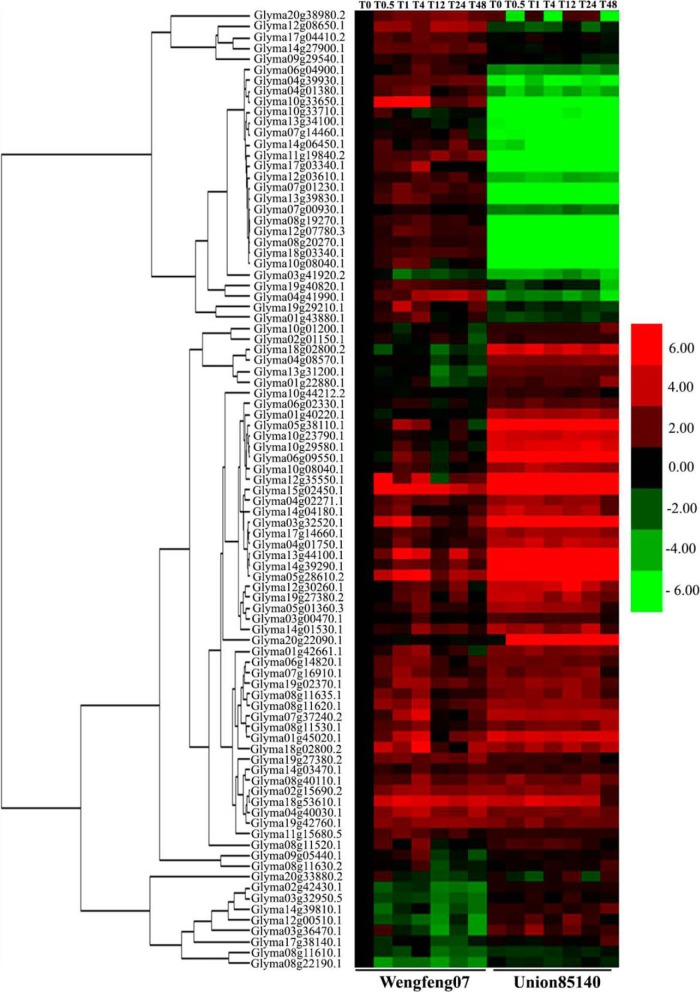

Phosphorylation Motif Analysis for Quantitative Phosphopeptides

To extract overrepresented patterns from the 1164 quantitative phosphorylated peptides with differential changes between the two cultivars, the software MEME Suite and motif-X were used to analyze the motifs generated at different time points after salinity treatment from the two soybean cultivars. The intensities of phosphopeptides from Wenfeng07 (IpW) were compared with those from Union85140 (IpU) and the ratio values (IpW:IpU) with significant (p value < 0.05) differences were divided into two groups. When the intensity value IpW > IpU, its corresponding phosphopeptide was categorized into the Up group, whereas the phosphopeptide with IpW < IpU was categorized into the Down group. The Up group represented the peptides with higher phosphorylation level in the salt-tolerant cultivar and lower phosphorylation level in the salt-sensitive cultivar. There were ten phosphorylation motifs enriched from the Up group (Fig. 6A) and 14 motifs enriched from the Down group (Fig. 6B). In addition, Ser and Thr were observed as the central phosphorylated amino acid residue in both groups, with much higher frequency for Ser. In both the Up and Down groups, the amino acid closely neighboring the phosphorylated Ser/Thr was mainly Pro or Asp (Fig. 6). There were six phosphorylation motifs ([sP], [xDsDx], [xsxxD], [xsxSx], [xsxDx], and [Sxxsx]) enriched from both Up and Down groups. Four motifs ([xsxPx], [xsDxE], [xsxEx], and [Pt]) were only found in the Up group, and eight ([xPxsPx], [xDsx], [xsxDD], [xsSPx], [Dxxsx], [Axxsx], [xtPx], and [xtDx]) only in the Down group. These differentially regulated motifs were then searched for their target kinases in relevant databases, for example, [sP] is a potential substrate of plant MAPK and [sDxE] is recognized by casein kinase-II (29, 48, 49).

Fig. 6.

Phosphorylation motifs enriched from sequence of peptide with different modification levels in two cultivars. A, phosphorylation motifs extracted from the phosphopeptides in the Up group by motif-X. B, phosphorylation motifs extracted from the phosphopeptides in the Down group by motif-X.

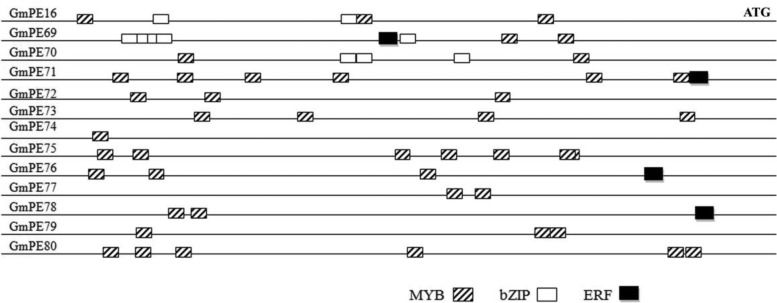

The Phosphorylated TFs and Their Specific Binding Motif in Enzymes Involved in Chalcone Metabolism

Several transcription factors, including MYB, bZIP, WRKY, ERF, BTF and GTE families were identified with fluctuating phosphorylation modifications at different time points of salt treatment (supplemental Tables S4 and S5). For example, ten GmMYB family proteins were quantitatively analyzed on one or more phosphorylated peptides. Interestingly, the phosphorylated peptide TVPSAsG in GmMYB I1KQI5 was detected in both cultivars, and another phosphorylated peptide FsPNLNQNPNPNLGK could only be detected in Union85140 (supplemental Tables S4 and S5), indicating that phosphorylation of the same protein could be modified at different sites in the two cultivars and might generate various activations. In addition, the phosphorylated peptide QKIDDsDESPNPK in GmMYB K7MQI8 in both cultivars was only detected at late time points (T12-T48) (supplemental Table S4). Similar results were observed in GmMYBs (K7LAB8 and I1JE71), GmbZIPs (Q00M78, I1JDF7, K7MV95, and C6T6L1), GmWRKY (I1MT25)and GmERF (I1KN17). This suggested a temporary regulation of this modification in response to salt stress.

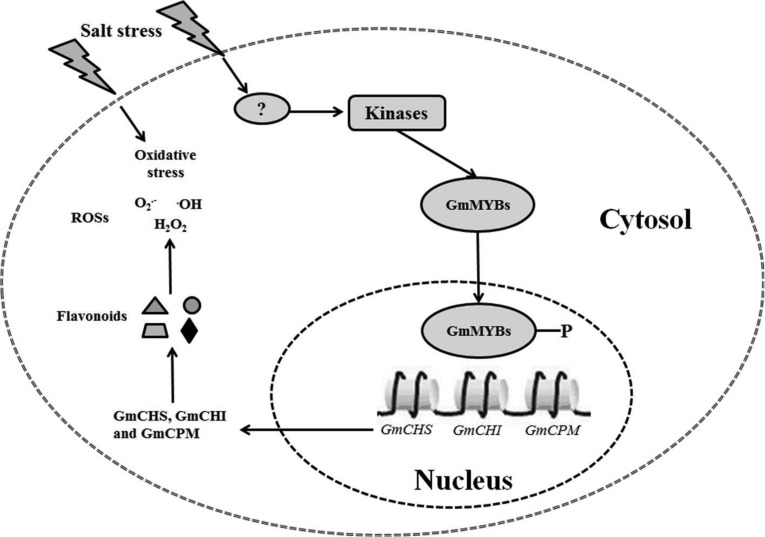

To reveal the potential interaction network between TFs and differentially expressed proteins, the TF-specific binding motifs of the promoters from enzymes involved in chalcone metabolism are summarized in Fig. 7. Motif structures of these promoters were retrieved from the JASPAR database (50). All the promoters of genes encoding chalcone synthase (GmCHS), chalcone isomerase (GmCHI), and cytochrome P450 monooxygenase (GmCMP) were predicted to contain the conserved motifs recognized by MYBs, indicating that the promoters of these 13 enzymes should be regulated by this TF family. In addition, promoters of the two GmCMP and one GmCHI also included motifs recognized by bZIP. Additionally, GmERF had potential binding motifs in promoters of some GmCHS, GmCMP and GmCHI genes. Because their activities might be regulated by phosphorylation modifications, these TFs should play significant roles in the bridge between stress signal and the transcription of salt responsive genes.

Fig. 7.

TFs specific binding motifs in promoters of GmCHS, GmCHI and GmCMP genes in soybean. All the promoters (2000 bp) of tested genes were scanned for discovering conserved motifs recognized by MYB, bZip and ERF TFs (88% threshold) at JASPAR (http://jaspar.genereg.net/cgi-bin/jaspar_db.pl?rm=browse&db=core&tax_group=plants). The abbreviations of gene names were listed in supplemental Table S3.

Rapid Function Tests of the Genes Involved in Chalcone Metabolism

In this research, the enzymes involved in chalcone metabolism were proposed to have potential correlations with soybean salt tolerance at both proteomic and transcriptional levels. To further validate that the chalcone synthase (CHS), chalcone isomerase (CHI) and cytochrome P450 monooxygenase (CPM) were determinants of plant salt-tolerance, gain-of-function and loss-of-function analyses were tested in soybean composites (Fig. 8) and A. thaliana mutants (Fig. 9), respectively, at seedling stage.

Fig. 8.

Effects of salinity stress on seedlings of soybean composites. The seedlings of negative control (Union85140/pCAMBIA1301), gmchs-ox (Union85140/GmCHS), gmchi-ox (Union85140/GmCHI) and gmcpm-ox ((Union85140/GmCPM)) composites were treated in 1/2 MS medium with or without 100 mm NaCl for 10 days. Bar: 1 cm.

Fig. 9.

Effects of salinity stress on seedlings of Arabidopsis thaliana mutants. The germination of Col-0 (WT), chs, chs/chi and chs/cpm plants grown in 1/2 Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium for 5 days and then transferred to 1/2 MS medium with or without 150 mm NaCl for 10 days. A and B, comparison of salt tolerance between WT and deletion mutant chs. C and D, comparison of salt tolerance between WT and double deletion mutant chs/chi. E and F: comparison of salt tolerance between WT and double deletion mutant chs/cpm. A, C, E: 0 mm NaCl; B, D, F: 150 mm NaCl; Bar: 2 cm.

When subjected to NaCl treatments, the Union85140/gmchs-ox composites showed higher tolerance than Union85140/pCAMBIA1301 (negative control) (Fig. 8), indicating that chalcone was a positive regulating factor in salt tolerance. Both of the gain-of-function Union85140/gmchi-ox and Union85140/gmcpm-ox composites (Fig. 8) showed a slight lower tolerance than the negative control. Similar results were observed in Arabidopsis, the single deletion mutant (chs) showed significantly lower tolerance than wild type (Fig. 9A and 9B), indicating that chalcone was a positive regulating factor in salt tolerance. Both of the loss-of-function double mutants chs/cpm (Fig. 9C and 9D) and chs/chi (Fig. 9E and 9F) also showed lower tolerance than wild type. However, these double mutants (chs/cpm and chs/chi) showed higher tolerance than the single deletion mutant (chs), suggesting that chalcone isomerase and cytochrome P450 monooxygenase were two negative regulating factors in salt tolerance. To summarize, chalcone synthase dominated the response to salt stress in chalcone metabolism.

DISCUSSION

Compared with the salt-sensitive Union85140, the salt-tolerant Wenfeng07 showed no significant advantage in exportation or compartmentalization of salts, but much higher capacity for ROS elimination within 48 h of NaCl treatment. Plants have evolved very complex mechanisms for ROS elimination at the transcription, translation and post-translational modification levels (12, 13, 15, 29, 51). The present study involved a comparative analysis of salt stress responses between a salt-tolerant and a salt-sensitive soybean variety using proteomic and phosphoproteomic approaches. Among them, 89 representative differentially expressed proteins were checked with their changes at transcriptional level using quantitative RT-PCR. Our results confirmed the view that expression differences at proteomic level are involved in functional proteins, whereas differences at phosphoproteomic level are mainly related to regulatory proteins (29). Interestingly, a series of proteins related to ROS scavenging and protein folding/degradation—such as GST, APX, SOD, heat shock protein 90–2, and Hsp70-Hsp90 organizing protein 1—were involved in salt responses of both salt-tolerant and salt-sensitive varieties, which were almost in accordance with previous studies (17, 52, 53). However, tolerance discriminations were possibly dominated by: (1) synthesis of flavonoid/isoflavonoid involved in the salicylic acid defense pathway by chalcone metabolism (54, 55) in Wenfeng07, compared with initiation of lateral roots by auxin response factor, auxin-induced protein AUX22 and PIN6a (10) in Union85140; (2) up-regulation of ERF and MYB TFs for activating MAPK and SOS pathways to eliminate ROS and excessive salts (12, 13) in Wenfeng07; and (3) regulating innate immunity via cytochrome P450 monooxygenase, chalcone isomerase, and sterol 24-C methyltransferase (56, 57) specifically in Wenfeng07.

However, phosphoproteomic comparisons revealed the details of dissimilarities in stress signal perception and transduction, transcription/translation of response genes and protein transporting. The protein samples were analyzed based on 2-DE MS/MS and LC MS/MS proteomics. A total of 89 differentially expressed nonredundant proteins were identified in LC MS/MS analysis and 90 in 2-DE MS/MS analysis. Of the 179 nonredundant differentially expressed proteins from LC-MS/MS and 2-DE MS/MS, 16 were also identified as phosphoproteins, including the stress-induced protein SAM22, histone H2A OS, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit C, elongation factor 1-delta-like, fructose-bisphosphate aldolase, cytosolic glutamine synthetase GSbeta1 for signal transduction, chromosome remodeling, gene translation, energy and small molecular metabolism, etc.

Perception of Salinity and Signal Transduction

The SOS system (e.g. SOS1: H9CDQ2, supplemental Table S4) acts as a central hub in preventing Na+ toxicity in the plant, especially for Wenfeng07. The most common role of the SOS system is to sequestrate Na+ ions from the plant cytosol (58). In general, the high salt stress suddenly triggers a cytosolic Ca2+ signature (59), which can be perceived by the calcineurin B-like protein, SOS3 and Ser/Thr protein kinase, SOS2 (60). After perceiving the Ca2+ signature, SOS3 is phosphorylated by the protein kinase SOS2. The SOS2/SOS3 complex activates the plasma membrane Na+/H+ antiporter, SOS1. Downstream of the SOS cascade, SOS1 mediates Na+ efflux at the root epidermis (61). In our study, there were many SOS2 and SOS3 homologs found with multiphosphorylated sites and with different regulation levels. For example, GmSOS2 (K7KTI3) was observed with four phosphorylation sites, in which phosphor-Ser in peptide LPEsPREGSEEDNFLENLTGMPIR only occurred at early time points T0.5-T4, but the phosphor-Ser in peptide EGsEEDNFLENLTGMPIR only occurred at late time points T12-T48 (supplemental Table S4). Interestingly, GmSOS3 (C6T458), both in Wenfeng07 and Union85140, was detected at T0 and all treatment times except T4 (supplemental Table S4). In addition, another GmSOS3 homolog (K7KLX6), from both cultivars, was detected at time points T12-T48.

The Ca2+ signature could also be perceived by calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs or CPKs) (62). The latter two transmit the signal into phosphorylation cascades capable of modulating gene expression and target protein activity (63). CDPKs, through their interaction with ion channels and transporters, seem to represent part of membrane-delimited plant stress responses (64). In the present study, the GmCDPK (D3G9M7) in Wenfeng07 showed much higher phosphorylation levels than Union85140 for time points T0.5-T48 (supplemental Table S4). This suggested that this GmCDPK might significantly contribute to the salt tolerance of Wenfeng07.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and hormones are key elements in intricate switches used by plants to trigger highly dynamic responses to changing environment. Although ROS may have deleterious effects in cells, they also act as signal transduction molecules involved in mediating responses to environmental stresses (65). Plant plasticity in response to the environment is linked to a complex signaling module in which ROS and antioxidants operate together with hormones, including auxin (66). The auxin resistant double-mutant tir1 afb2 showed increased tolerance to salinity as measured by chlorophyll content, germination rate and root elongation. In addition, mutant plants displayed reduced hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and superoxide anion (O2−−.) levels, as well as enhanced antioxidant metabolism (67). Microarray analyses indicated that auxin responsive genes are repressed by oxidative and salt treatments in rice (68). More recently, the transcriptomic data of Blomster et al. (69) showed that various aspects of auxin homeostasis and signaling are modified by apoplastic ROS. Together, these findings suggest that the suppression of auxin signaling might be a strategy of plants to enhance their tolerance to abiotic stress, including salinity. In this study, the auxin response factor K7M7H1 was found with phosphorylated serine (in peptide sPPQPR). However, this modification was only detected at late time points T12-T48 (supplemental Table S4). Recent research found that a salt-responsive ethylene response factor1 (ERF1) regulates ROS-dependent signaling during the initial response to salt stress (13). However, the GmERF (I1KN17) was only observed with phosphorylation modification in the sensitive cultivar Union85140 (supplemental Table S4).

Other reported pathways of salt signaling include mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK or MPK) cascades (70). A MAPK cascade consists of a MAPK kinase (MAPKkk)–MAPK kinase (MAPKK/MKK)–MAPK module that links salt-signal receptors to downstream targets (71). For a rapid signal transduction, the GmMAPKK2 (Uniprot accession no. Q5JCL0) showed a much higher level phosphorylation modification after NaCl treatment in both Wenfeng07 and Union85140 (supplemental Table S4).

Metabolism of Small Molecules Related to Detoxification and Defense Pathways

Under salinity stress, the plant employs detoxification and defense pathways to increase their tolerance (58). Several abiotic stresses, such as salt, drought and cold can induce ROS accumulation including O2−−., H2O2 and hydroxyl radicals (10). Suitable concentrations of ROS are acquired as substrates in lipid, sugar and protein metabolisms. Peak values of ROS concentration usually act as signals for inducing ROS scavengers, which are mainly substrates involved in these metabolisms. In this study, copper amino oxidase and quinone oxidoreductase, which produces ROS (72, 73), were up-regulated after salt treatment. Meanwhile, universal scavengers, such as APX, SOD, GST and POD, also showed up-regulation in roots of both salt-sensitive and -tolerant soybean. Among these scavengers, APX has been shown to reduce H2O2 to H2O, with the concomitant generation of monodehydroascorbate. Many reports demonstrating that APX overexpression can enhance the salt tolerance of different plants have confirmed that APX plays an important role in scavenging ROS produced by salinity stress (74–77). Moreover, the two homologs of APX might have different efficiencies in ROS elimination, because APX2 was significantly up-regulated in the tolerant cultivar (Wenfeng07), whereas APX1 was significantly up-regulated in the sensitive cultivar (Union85140) after salt treatment. This result is consistent with findings in two rice APXs (78).

Chalcone Metabolism Pathway is Involved in Soybean Tolerance to Salt Stress

Up to now, the chalcone metabolism pathway has mainly been considered as a feasible strategy for enhancing plant immunity to microbes (79–81). In plants, chalcone biosynthesis begins with the hydroxylation of cinnamic acid by cytochrome P450 monooxygenase (82). The intermediate product p-coumaric acid is then activated by 4-coumaroyl:CoA ligase, yielding p-coumaroyl-coenzyme A (CoA) (83, 84). Subsequently, malonyl-CoA is added to p-coumaroyl-CoA and yields tetrahydroxychalcone by the enzyme chalcone synthase. Finally, chalcone isomerase converts the C15 compound tetrahydroxychalcone into (2S)-flavanones (85–87). These flavonoids, including a diverse family of polyphenols, have been proven with health-promoting effects especially in preventing various human pathological risks (88, 89). Hence, significant amounts of research have been stimulated to elucidate the biosynthetic networks of flavonoids (90, 91). However, there are very few reports on the contribution of chalcone metabolism to plant salt tolerance (92, 93). Recently, a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase mutant was shown to be involved in a series of abiotic stresses including ABA and salt in Arabidopsis (94). Our proteomic and phosphoproteomic analyses showed that key enzymes, such as cytochrome P450 monooxygenase, chalcone synthase and chalcone isomerase, were correlated with salt stress especially in tolerant cultivar Wenfeng07. Their salt-responsive dynamics were also confirmed at the transcriptional level. The functions of these enzymes were preliminarily tested in soybean composites and Arabidopsis mutants. Both the gain of function and loss-of-function tests demonstrated that cytochrome P450 monooxygenase and chalcone isomerase were negatively related with salt tolerance in plant seedlings, whereas chalcone synthase was positively related.

Interestingly, 10 MYB (MYB like) transcription factors (TFs) were identified with significantly changed phosphorylation sites (supplemental Table S4 and S5). Commonly, MYB TFs play crucial roles in flavonol accumulation by regulating the expression of series genes coding for key enzymes involved in chalcone metabolism in plants (95–97). In addition, three chalcone metabolism enzymes have been found in response to salt stress. These results indicate that the network between phosphorylated MYB TFs and chalcone metabolism enzymes might play potential crucial roles in soybean's tolerance to salinity.

CONCLUSION

Plants have evolved a set of physiological and biochemical responses for adaptation to salinity stress. Generally, glutathione and proline as well as several secondary metabolites, such as flavonoids, play a pivotal role in tolerance/detoxification of plants (98–100).