Significance

Inactivation of the tumor-suppressor gene breast cancer susceptibility type 1 (BRCA1) triggers abnormal microtubule assembly during mitosis, causing chromosome missegregation and aneuploidy. Unraveling how BRCA1 is regulated during mitosis and how it contributes to microtubule assembly is pivotal to understand its tumor-suppressor function. We showed that BRCA1 is positively regulated during mitosis by the tumor-suppressor kinase checkpoint kinase 2 (Chk2). This regulation is required for the recruitment of a protein phosphatase, which restrains oncogenic Aurora-A kinase activity bound to BRCA1. Unleashed Aurora-A, in turn, can negatively regulate the mitotic function of BRCA1. Thus we define a network in which the Chk2–BRCA1 tumor-suppressor axis restrains oncogenic Aurora-A to ensure proper function of BRCA1 in mitosis essential for normal regulation of microtubule dynamics and chromosome segregation.

Keywords: mitosis, chromosome segregation, aneuploidy, protein phosphatase, tumor suppressor

Abstract

BRCA1 (breast cancer type 1 susceptibility protein) is a multifunctional tumor suppressor involved in DNA damage response, DNA repair, chromatin regulation, and mitotic chromosome segregation. Although the nuclear functions of BRCA1 have been investigated in detail, its role during mitosis is little understood. It is clear, however, that loss of BRCA1 in human cancer cells leads to chromosomal instability (CIN), which is defined as a perpetual gain or loss of whole chromosomes during mitosis. Moreover, our recent work has revealed that the mitotic function of BRCA1 depends on its phosphorylation by the tumor-suppressor kinase Chk2 (checkpoint kinase 2) and that this regulation is required to ensure normal microtubule plus end assembly rates within mitotic spindles. Intriguingly, loss of the positive regulation of BRCA1 leads to increased oncogenic Aurora-A activity, which acts as a mediator for abnormal mitotic microtubule assembly resulting in chromosome missegregation and CIN. However, how the CHK2–BRCA1 tumor suppressor axis restrains oncogenic Aurora-A during mitosis to ensure karyotype stability remained an open question. Here we uncover a dual molecular mechanism by which the CHK2–BRCA1 axis restrains oncogenic Aurora-A activity during mitosis and identify BRCA1 itself as a target for Aurora-A relevant for CIN. In fact, Chk2-mediated phosphorylation of BRCA1 is required to recruit the PP6C–SAPS3 phosphatase, which acts as a T-loop phosphatase inhibiting Aurora-A bound to BRCA1. Consequently, loss of CHK2 or PP6C-SAPS3 promotes Aurora-A activity associated with BRCA1 in mitosis. Aurora-A, in turn, then phosphorylates BRCA1 itself, thereby inhibiting the mitotic function of BRCA1 and promoting mitotic microtubule assembly, chromosome missegregation, and CIN.

Breast cancer type 1 susceptibility protein (BRCA1) is a major and multifunctional tumor-suppressor protein involved in the regulation of chromatin organization, gene expression, DNA damage response, and DNA repair (1–3). In addition to its functions in interphase, BRCA1 also is required for faithful execution of mitosis. Consequently, loss of BRCA1 results in abnormal mitotic progression, chromosome missegregation, and chromosomal instability (CIN), hallmark phenotypes of human cancer (4–6). However, the mitotic function of BRCA1 and its regulation during mitosis is little understood. BRCA1 localizes to centrosomes throughout the cell cycle and is phosphorylated during mitosis on S988 by the checkpoint kinase 2 (Chk2). This positive regulation is essential to ensure proper mitotic spindle assembly and chromosomal stability (5, 7, 8). Importantly, we recently have found that the loss of CHK2 or of Chk2-mediated phosphorylation on BRCA1 causes an increase in microtubule plus-end assembly rates, which results in transient spindle geometry defects facilitating the generation of erroneous microtubule–kinetochore attachments. These defects finally lead to chromosome missegregation and the induction of aneuploidy, thus constituting CIN (6).

Interestingly, BRCA1 associates with the Aurora-A kinase during mitosis (6). Aurora-A is a key mitotic kinase encoded by the AURKA oncogene and is involved in various functions during mitosis, including centrosome separation and spindle assembly (9, 10). Aurora-A activation occurs at mitotic centrosomes and requires its autophosphorylation within the T-loop at threonine-288. Subsequent inactivation of Aurora-A can be mediated by the serine/threonine protein phosphatase 6 (PP6), which acts as the T-loop phosphatase for Aurora-A, and involves the catalytic subunit (PP6C) as well as regulatory subunits referred to as “Sit4-associated proteins” (SAPS1-3) and ankyrin repeat proteins (11–13). Significantly, in human cancer, AURKA frequently is overexpressed, and increased activity of AURKA is sufficient to induce enhanced microtubule plus end assembly rates, chromosome missegregation, and CIN (6). Thus, overexpression of AURKA and loss of the CHK2–BRCA1 axis result in the same mitotic abnormalities triggering CIN. Moreover, loss of the Chk2-mediated phosphorylation of BRCA1 causes an increase in BRCA1-bound Aurora-A kinase activity at mitotic centrosomes, which mediates the induction of abnormal microtubule plus end dynamics and CIN (6). However, the molecular mechanism by which the loss of the CHK2–BRCA1 tumor-suppressor axis unleashes oncogenic Aurora-A activity during mitosis and the mitotic target for Aurora-A relevant for the induction of increased microtubule dynamics and CIN remain unknown.

Results

The PP6C–SAPS3 Protein Phosphatase Associates with BRCA1 During Mitosis in a Chk2-Dependent Manner.

Loss of Chk2-mediated phosphorylation of BRCA1 during mitosis causes increased binding of active Aurora-A kinase to BRCA1, thereby triggering an increase in mitotic microtubule assembly rates and leading to chromosome missegregation and CIN (6). To gain insights into the mechanism of how the CHK2–BRCA1 tumor-suppressor axis negatively regulates the activity levels of oncogenic Aurora-A, we performed BRCA1 immunoprecipitation experiments combined with SILAC (stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture)-based mass spectrometry analyses. This approach allowed the comparative and quantitative analyses of proteins bound to BRCA1 during mitosis in the presence (in HCT116 cells) or absence (in isogenic HCT116-CHK2−/− cells) of Chk2 as outlined in Fig. S1A. Mass spectrometry analyses identified a total of 515 proteins coimmunoprecipitating with BRCA1 (Dataset S1). The interaction of most of these proteins was not or was little regulated by Chk2, and among those were several known BRCA1-interacting proteins including BARD1, BRIP1/BACH1, and HSP90 (Fig. S1B and Dataset S1), thereby validating the approach. Importantly, among the proteins that showed reduced interaction with BRCA1 upon loss of CHK2 [heavy/light (H/L) ratio >2], we found SAPS3, also known as PPP6R3 (H/L ratio = 2.7; Dataset S1: GI: 88941982). SAPS3 (GI: 194382030) also was identified in our previous mass spectrometry analyses (14) as a BRCA1-interacting protein. This protein immediately caught our attention, because SAPS3 represents a regulatory subunit of PP6 (12), which recently has been identified as a T-loop phosphatase for Aurora-A (11). Therefore, we reasoned that SAPS3-PP6 might represent the missing link for the Chk2–BRCA1–dependent regulation of Aurora-A activity during mitosis, and hence we focused on SAPS3 as a previously unidentified BRCA1-interacting protein.

Fig. S1.

(A) Workflow for the identification of proteins that associate with BRCA1 during mitosis in a Chk2-dependent manner. HCT116 cells were labeled with heavy amino acids (Lys-6, Arg-6), and HCT116 or HCT116-CHK2−/− cells were labeled with light amino acids (Lys-0, Arg-0). After mitotic cell synchronization the whole-cell lysates were mixed 1:1, BRCA1 was immunopurified, and associated proteins were identified by LC-MS analysis. (B) Examples of known BRCA1-interacting proteins identified from SILAC-mass spectrometry analysis using mitotic HCT116 and HCT116-CHK2−/− cells in comparison with SAPS3. H/L ratios are shown indicating the change in their interaction with BRCA1 upon the loss of CHK2. See also Dataset S1. (C) The Aurora-A–TPX2 interaction is not altered after the loss of CHK2. HCT116 or HCT116-CHK2−/− cells were synchronized in mitosis, and TPX2 was immunoprecipitated. Representative Western blots show the detection of TPX2-bound total Aurora-A and active (pT288) Aurora-A. (D) The Aurora-A–TPX2 interaction is not altered after the loss of the S988 phosphorylation site in BRCA1. Endogenous BRCA1 was replaced by an S988E mutant of BRCA1, and TPX2 was immunoprecipitated from mitotic cells. Representative Western blots show the detection of TPX2-bound total Aurora-A and active (pT288) Aurora-A. (E) Increased binding of active Aurora-A to BRCA1 upon inhibition of serine/threonine phosphatases by okadaic acid or after the loss of CHK2. BRCA1 was immunoprecipitated from whole-cell lysates derived from mitotically synchronized HCT116 or HCT116-CHK2−/− cells and was treated with DMSO (control) or with 0.5 µM okadaic acid for 1 h. BRCA1-bound Aurora-A (total) and active Aurora-A (pT288-Aurora-A) were detected on Western blots. Representative Western blots are shown.

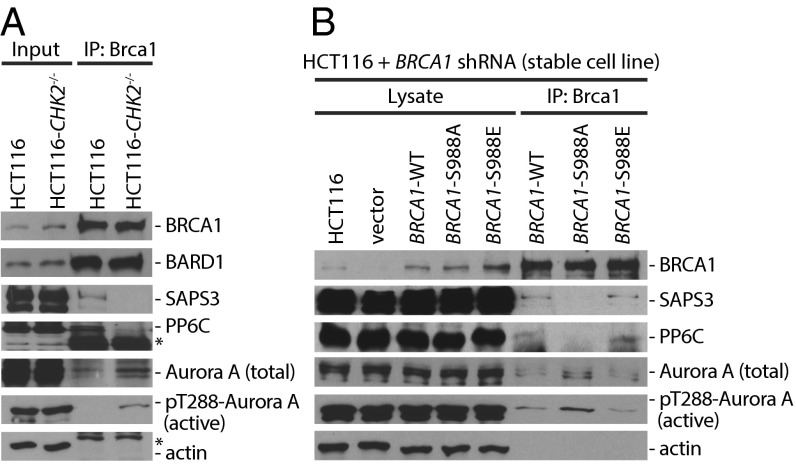

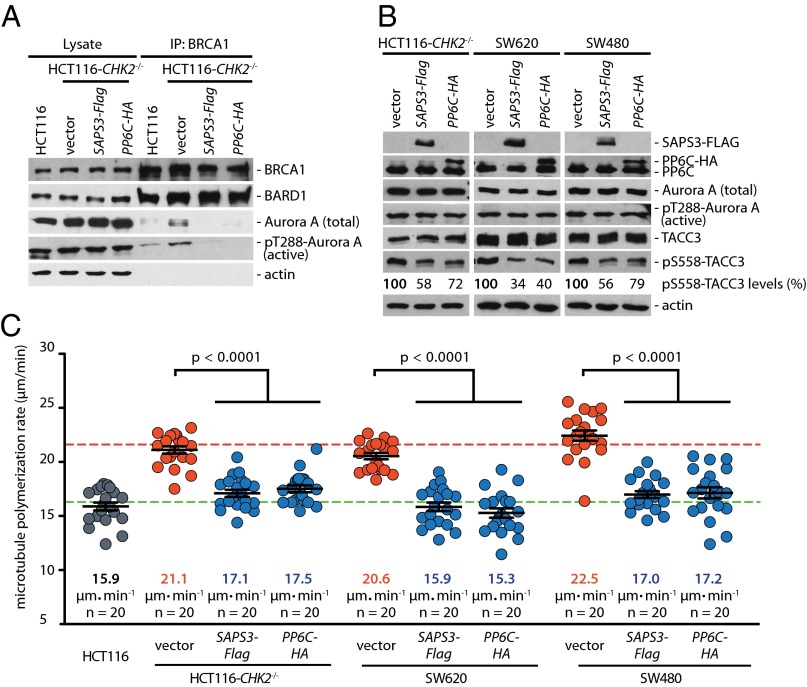

Immunoprecipitation experiments using mitotic cell extracts verified the reduced interaction of SAPS3 and PP6C with BRCA1 upon loss of Chk2 (Fig. 1A). Loss of the PP6–BRCA1 interaction was accompanied by an increased binding of active, autophosphorylated Aurora-A (phospho-Thr-288) to BRCA1 (Fig. 1A). To test whether the Chk2-mediated phosphorylation of BRCA1 on S988 is required for the recruitment of PP6C-SAPS3 to BRCA1, we performed BRCA1 reconstitution experiments. We expressed WT or nonphosphorylatable (S988A) or phospho-mimetic (S988E) mutants of BRCA1 in HCT116 cells harboring a stable shRNA-mediated knockdown of BRCA1 and analyzed the BRCA1–PP6 interaction. Indeed, the nonphosphorylatable BRCA1 mutant protein could no longer bind to PP6C-SAPS3, and, again, the loss of this interaction was associated with increased binding of active Aurora-A to BRCA1 (Fig. 1B). In contrast, the interaction of Aurora-A with its well-known binding partner TPX2 was not affected by the loss of CHK2 or by the loss of the S988-phosphorylation site in BRCA1 (Fig. S1 C and D). These results suggest that loss of the recruitment of the phosphatase complex might be responsible for increased activity of Aurora-A bound to BRCA1. In line with this reasoning, treatment of cells with the serine/threonine protein phosphatase inhibitor okadaic acid also increased the amount of active Aurora-A kinase associated with BRCA1 (Fig. S1E).

Fig. 1.

The PP6C-SAPS3 protein phosphatase is recruited to BRCA1 in a Chk2-dependent manner. (A) Detection of PP6C and SAPS3 as BRCA1-interacting proteins. BRCA1 was immunoprecipitated from whole-cell lysates derived from HCT116 cells and from HCT116-CHK2−/− cells synchronized in mitosis, and BARD1, SAPS3, PP6C, and total and active Aurora-A (pT288) were detected on Western blots. Representative Western blots are shown. (B) The interaction of BRCA1 with PP6C-SAPS3 requires Chk2-mediated phosphorylation of BRCA1. HCT116 cells stably expressing shRNAs targeting BRCA1 were reconstituted with BRCA1-WT or with the S988A or S988E mutants. BRCA1 proteins were immunoprecipitated, and SAPS3, PP6C, and total and active Aurora-A were detected on Western blots. Representative Western blots are shown.

PP6C-SAPS3 Restrains BRCA1-Bound Aurora-A Activity to Ensure Proper Microtubule Assembly Rates During Mitosis.

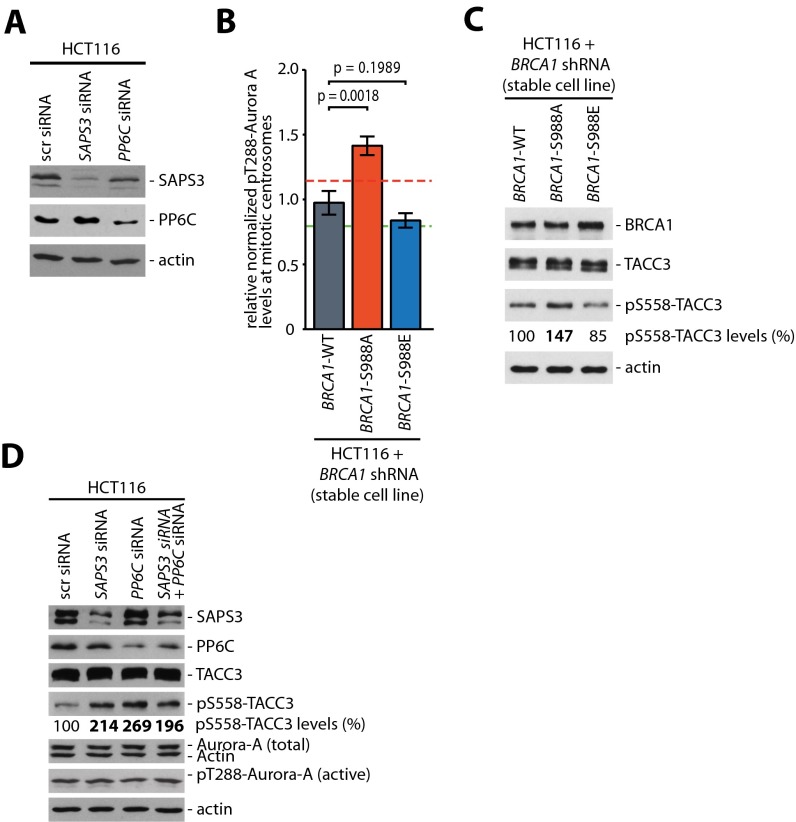

To address whether PP6C-SAPS3 restrains the activity of Aurora-A bound to BRCA1, we depleted SAPS3 and/or PP6C (Fig. S2A) and assessed Aurora-A bound to BRCA1. Indeed, loss of PP6C or SAPS3 was sufficient to increase a subpool of active Aurora-A in complex with BRCA1 but did not significantly alter the overall Aurora-A levels and activity in whole-cell lysates (Fig. 2A). Because our previous work has shown that the loss of the Chk2–BRCA1 axis results in an increase in Aurora-A activity localized at mitotic centrosomes (6), we performed quantitative immunofluorescence microscopy to detect Aurora-A spatially. We found that, very similar to the increase in Aurora-A activity seen after the loss of CHK2 (6) and after the loss of the Chk2-mediated phosphorylation site of BRCA1 (Fig. S2B and ref. 6), loss of the PP6C or SAPS3 caused an ∼40% increase in active Aurora-A localized at mitotic centrosomes, but the overall levels of Aurora-A at centrosomes remained unchanged (Fig. 2B). As a consequence of the increase in centrosomal Aurora-A kinase activity upon loss of PP6C-SAPS3 or after loss of the Chk2-mediated phosphorylation site of BRCA1, the phosphorylation of the bona fide centrosomal Aurora-A target TACC3, which represents a robust marker for centrosomal Aurora-A activity, was increased (Fig. S2 C and D) (6, 15, 16).

Fig. S2.

(A) siRNA-mediated repression of SAPS3 and PP6C in HCT116 cells. HCT116 cells were transfected with siRNAs targeting SAPS3 or PP6C, and protein levels were detected in whole-cell lysates. Representative Western blots are shown. (B) Phosphorylation of BRCA1 on S988 restrains Aurora-A activity on mitotic centrosomes. Detection of active Aurora-A (pT288) and centrin-2 at mitotic centrosomes in HCT116 cells with stable BRCA1 knockdown (BRCA1 shRNA) and re-expression of WT BRCA1 (BRCA1-WT) or nonphosphorylatable (-S988A) or phospho-mimetic (-S988E) mutants of BRCA1. The signal intensities were normalized to signals from centrosomal centrin-2 and were quantified. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; t test; n = 77 (WT), 40 (S988A), or 85 (S988E) cells. (C) Detection of increased phosphorylation of TACC3 on S558 after the loss of the Chk2-mediated phosphorylation site of BRCA1. Cells from B were synchronized in mitosis, and BRCA1 and total and phosphorylated TACC3 were detected on Western blots. Representative Western blots are shown. pS558-TACC3 levels were quantified by densitometry. (D) Detection of increased phosphorylation of TACC3 on S558 after the repression of PP6C or SAPS3. HCT116 cells transfected with siRNAs targeting PP6C or SAPS3 were synchronized in mitosis, and SAPS3, PP6C, total and active Aurora-A, and total and phosphorylated TACC3 were detected on Western blots. Representative Western blots are shown. pS558-TACC3 levels were quantified by densitometry.

Fig. 2.

Repression of PP6C-SAPS3 is sufficient to increase the activity of centrosomal Aurora-A and accelerates microtubule assembly rates. (A) Repression of PP6C or SAPS3 increases the binding of active Aurora-A to BRCA1. PP6C and/or SAPS3 were repressed in HCT116 cells by siRNAs, and BRCA1 was immunoprecipitated from mitotic cell lysates. The indicated proteins were detected on Western blots. Representative Western blots are shown. (B) Repression of PP6C or SAPS3 increases centrosomal Aurora-A activity. Detection of total or active Aurora-A (pT288) and centrin-2 at mitotic centrosomes in HCT116 cells upon siRNA-mediated repression of PP6C or SAPS3. (Lower) Representative immunofluorescence images of Aurora-A or active pT288-Aurora-A (red), centrin-2 (green), and chromosomes (blue). (Scale bar, 10 µm.) (Upper) The signal intensities were normalized to signals form centrosomal centrin-2 and quantified. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; t test; n = 100 cells. (C) Repression of PP6C or SAPS3 increases mitotic microtubule assembly rates. Microtubule plus-end assembly rates were determined in bipolar metaphase or monopolar spindles after siRNA-mediated repression of PP6C or SAPS3. To inhibit Aurora-A activity partially, mitotic cells were treated with the Aurora-A inhibitor MLN8054 (0.06 µM) for 1 h. Scatter dot plots show average assembly rates (20 microtubules per cell). Green dashed line, normal values; red dashed line, abnormally increased values. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; t test; n = 20–30 cells from three independent experiments.

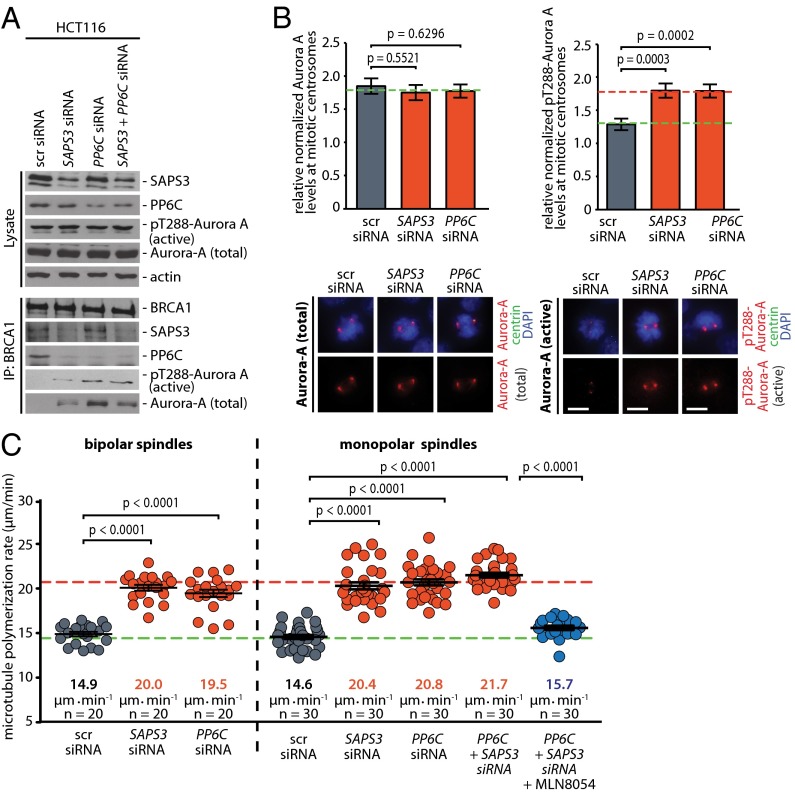

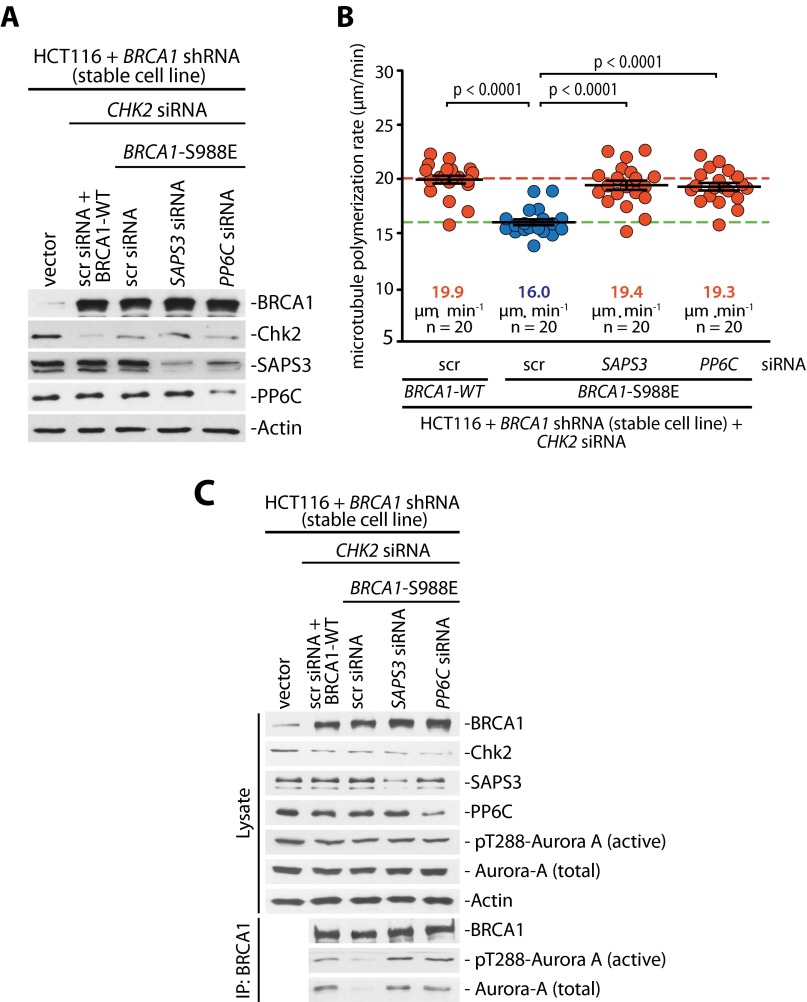

Because increased Aurora-A activity can trigger an increase in mitotic microtubule assembly rates as an underlying mechanism for subsequent chromosome missegregation and CIN (6), we determined microtubule plus-end assembly rates by live cell microscopy, tracking EB3-GFP comets in mitotic cells (Fig. S3 and Movies S1–S4) (6, 17). Very similar to the loss of CHK2 (Fig. 3C) (6), the loss of PP6C-SAPS3 was sufficient to trigger an increase in microtubule plus-end assembly rates in both bipolar metaphase spindles and monopolar spindles after synchronization of cells using a Eg5/KSP inhibitor (Fig. 2C). Importantly, this increase in microtubule growth was suppressed upon treatment with the Aurora-A–specific inhibitor MLN8054 (Fig. 2C), indicating that the induction of abnormal microtubule assembly rates in response to loss of the PP6C-SAPS3 phosphatase is mediated by increased Aurora-A activity. Moreover, we found that the ability of a phospho-mimetic mutant of BRCA1 (S988E) to restore proper microtubule plus-end assembly rates in the absence of Chk2 requires SAPS3 and PP6C (Fig. S4 A and B), indicating that SAPS3 and PP6C act through BRCA1 to regulate microtubule plus-end assembly. Consistently, the suppression of active Aurora-A bound to BRCA1 upon mimicking the Chk2-mediated phosphorylation also was dependent on SAPS3 and PP6C (Fig. S4C). Together, our results strongly suggest that the S988-phosphorylation–dependent recruitment of PP6C-SAPS3 represents a key requirement to prevent an Aurora-A–mediated increase in microtubule plus-end growth.

Fig. S3.

Schematic depiction of the measurement of microtubule plus-end assembly rates using EB3-GFP tracking in living cells. (A) Measurements in bipolar metaphase spindles. EB3-GFP comets within the indicated analysis zone are detected, and their velocity is determined over time. (B) Still images of Movies S1 and S2 showing bipolar metaphase spindles used to measure microtubule plus-end assembly rates. (Scale bars, 10 µm.) (C) Measurements in monopolar spindles. EB3-GFP was detected in cells synchronized in prometaphase by treatment with the Eg5/KSP inhibitor dimethylenastron. Microtubule plus-end assembly rates do not differ between bipolar and monopolar spindles. (D) Still images of Movies S3 and S4 showing monopolar spindles used to measure microtubule plus-end assembly rates. (Scale bars, 10 µm.)

Fig. 3.

Overexpression of PP6C-SAPS3 inhibits centrosomal and BRCA1-bound Aurora A activity and suppresses increased microtubule assembly rates in colorectal cancer cells. (A) Overexpression of PP6C or SAPS3 in CHK2-deficient HCT116 cells decreases the interaction of active Aurora-A with BRCA1. HCT116 cells overexpressing PP6C-HA or SAPS3-FLAG were synchronized in mitosis, and BRCA1 was immunoprecipitated. Total and active Aurora-A (pT288) bound to BRCA1 was detected on Western blots. Representative Western blots are shown. (B) Overexpression of PP6C or SAPS3 decreases the centrosomal activity of Aurora A. PP6C-HA or SAPS3-FLAG was expressed in HCT116-CHK2−/−, SW620, or SW480 cells and synchronized in mitosis. Total and phosphorylated TACC3 was detected as a marker for centrosomal Aurora-A activity on Western blots, and phosphorylated TACC3 was quantified. Representative Western blots are shown. (C) The overexpression of PP6C or SAPS3 restores normal microtubule assembly rates in HCT116-CHK2−/−, SW620, and SW480 cells. Microtubule plus-end assembly rates were determined in the different cell lines in the absence or presence of PP6C or SAPS3 overexpression. Scatter dot plots show average assembly rates (20 microtubules per cell). Green dashed line, normal values; red dashed line, abnormally increased values. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; t test; n = 20 cells from three independent experiments.

Fig. S4.

PP6C-SAPS3 acts through BRCA1 to regulate mitotic microtubule growth. (A) Detection of BRCA1, Chk2, SAPS3, and PP6C in cells after siRNA-mediated depletion of CHK2, SAPS, or PP6C and after concomitant replacement of endogenous BRCA1 with an S988E mutant. Representative Western blots are shown. (B) Determination of microtubule plus-end assembly rates in cells after the loss of CHK2 and the expression of a BRCA1-S988E mutant in the presence or absence of SAPS3 or PP6C. Scatter dot plots show average assembly rates (20 microtubules per cell). Data are shown as mean ± SEM; t test; n = 20 cells from three independent experiments. (C) BRCA1 was immunoprecipitated from cells after loss of CHK2 and concomitant expression of a BRCA1-S988E mutant in the presence or absence of SAPS3 or PP6C. The indicated proteins were detected on Western blots. Representative Western blots are shown.

Overexpression of PP6C-SAPS3 Suppresses Increased Microtubule Assembly Rates in Colorectal Cancer Cells.

Because loss of the Chk2-mediated phosphorylation of BRCA1 results in the removal of PP6C-SAPS3 from BRCA1, leading to the induction of Aurora-A activity and increased microtubule assembly rates (Figs. 1 and 2), we reasoned that overexpressing PP6C-SAPS3 would suppress Aurora-A activity and might restore proper microtubule dynamics. Indeed, the overexpression of SAPS3 or PP6C in CHK2-deficient HCT116 cells significantly suppressed the levels of active Aurora-A bound to BRCA1 (Fig. 3A), caused a significant reduction of TACC3 phosphorylation (Fig. 3B), and was sufficient to restore normal mitotic microtubule assembly rates (Fig. 3C). Similarly, centrosomal Aurora-A activity was suppressed and proper microtubule assembly rates were restored in response to PP6C or SAPS3 overexpression in SW620 and SW480 colorectal cancer cells, which also are characterized by Aurora-A–mediated increased microtubule assembly rates (Fig. 3 B and C) (6).

Increased Aurora-A Activity Targets BRCA1 During Mitosis.

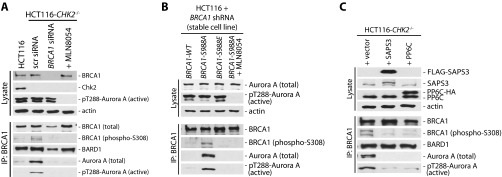

Our data demonstrate that the loss of CHK2 or PP6C-SAPS3 results in increased Aurora-A activity that triggers an increase in microtubule assembly rates. What, however, is the crucial target for Aurora-A that mediates abnormal microtubule dynamics during mitosis? Because Aurora-A is bound to BRCA1, we wondered whether this interaction might reflect a kinase–substrate interaction. To address this possibility, we raised antibodies against phosphorylated S308 of BRCA1, which represents a putative Aurora-A phosphorylation site. Using these phospho-specific antibodies, we detected only very weak phosphorylation of BRCA1 in mitotic HCT116 cells. However, in isogenic CHK2-deficient cells, in which active Aurora-A bound to BRCA1 is increased, the S308 phosphorylation of BRCA1 was clearly increased also. Moreover, treatment of cells with MLN8054 abolished BRCA1-S308 phosphorylation, indicating that Aurora-A indeed mediates this phosphorylation of BRCA1 (Fig. 4A and Fig. S5A). Similarly, loss of the Chk2-target site of BRCA1 upon reconstitution with a S988A mutant not only led to an increase in active Aurora-A bound to BRCA1 but also induced BRCA1-308 phosphorylation (Fig. S5B). These results indicate that phosphorylation of BRCA1 on S308 is mediated by Aurora-A and that Aurora-A activity is predetermined by the Chk2-mediated phosphorylation of BRCA1 on S988. Because S988 phosphorylation is required for the recruitment of the PP6C-SAPS3 phosphatase complex to BRCA1, we consequently found that loss of the phosphatase also results in an increase in Aurora-A–mediated phosphorylation of BRCA1 on S308 (Fig. 4B). Vice versa, overexpression of PP6C or SAPS3 in CHK2-deficient HCT116 cells not only caused a decrease in active Aurora-A bound to BRCA1 but also decreased BRCA1 phosphorylation on S308 (Fig. S5C). Thus, increased Aurora-A activity bound to BRCA1 causes increased BRCA1 phosphorylation on S308, and this increased phosphorylation might represent the relevant trigger for increased mitotic microtubule dynamics and chromosome missegregation.

Fig. 4.

Increased Aurora-A–mediated BRCA1 phosphorylation on S308 upon the loss of CHK2 or after repression of PP6C-SAPS3. (A) Phosphorylation of BRCA1 on S308 is induced by the loss of CHK2 and is dependent on Aurora A kinase activity. Parental HCT116 and HCT116-CHK2−/− cells were synchronized in mitosis, and BRCA1 was immunoprecipitated. Total and S308 phosphorylated BRCA1 and total and active (pT288) Aurora-A proteins were detected on Western blots. In addition, cells were treated with MLN8054 for 1 h to inhibit Aurora-A activity. Representative Western blots are shown. (B) Repression of PP6C or SAPS3 induces BRCA1 phosphorylation on S308. HCT116 cells were transfected with siRNAs targeting PP6C or SAPS3, and BRCA1 was immunoprecipitated from mitotic cell lysates. The phosphorylation on S308 of BRCA1 and its binding to BARD1 and Aurora-A were analyzed. Representative Western blots are shown.

Fig. S5.

(A) Detection of BRCA1 protein phosphorylated on S308. Phospho-specific antibodies recognizing BRCA1 phosphorylated on S308 were generated in rabbits and used to detect phosphorylated BRCA1 in mitotic cells. HCT116 cells and isogenic CHK2-deficient cells were synchronized in mitosis, and BRCA1 was immunoprecipitated. Subsequently, phosphorylated BRCA1 and Aurora-A proteins bound to BRCA1 were detected on Western blots. To verify the specificity of the phospho-specific antibodies, BRCA1 was repressed by the use of siRNAs, and cells were treated with 0.5 µM of the Aurora-A inhibitor MLN8054 to inhibit Aurora-A kinase activity. Representative Western blots are shown. (B) The phosphorylation of BRCA1 on S308 is induced after loss of the Chk2-mediated phosphorylation of BRCA1. Stable BRCA1-knockdown cells were reconstituted with BRCA1-WT or with BRCA1-S988A or BRCA1-S988E mutants, and BRCA1 proteins were immunoprecipitated from mitotic cell lysates. In addition, cells expressing BRCA1-S988A were treated with MLN8054 to inhibit Aurora-A kinase activity. BRCA1 phosphorylated on S308 and Aurora-A was detected, and representative Western blots are shown. (C) Overexpression of PP6C or SAPS3 decreases BRCA1 phosphorylation on S308. PP6C-HA or SAPS3-FLAG was overexpressed in CHK2-deficient HCT116 cells, and BRCA1 was immunoprecipitated form mitotic cell lysates. The phosphorylation of BRCA1 on S308 and BRCA1-associated proteins was detected. Representative Western blots are shown.

Aurora-A–Mediated Phosphorylation of BRCA1 Determines Mitotic Microtubule Assembly Rates and Faithful Chromosome Segregation.

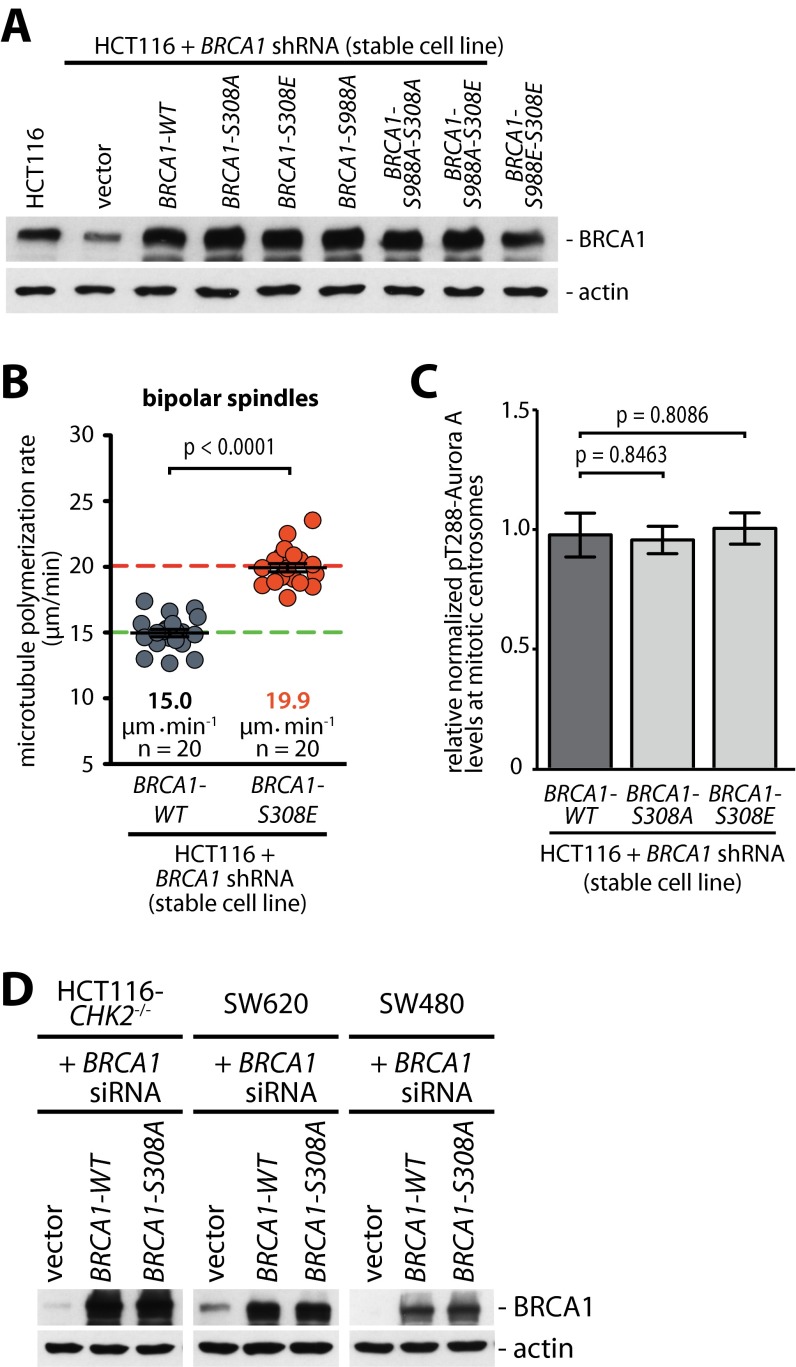

To test whether Aurora-A–mediated phosphorylation of BRCA1 on S308 is indeed functionally involved in the regulation of mitotic microtubule plus-end assembly, we reconstituted BRCA1-knockdown cells with various BRCA1 phospho-site mutants (Fig. S6A) and determined the microtubule assembly rates in mitosis. In fact, the loss of the Chk2-mediated phosphorylation site of BRCA1 (S988A mutant), which is associated with increased S308 phosphorylation of BRCA1 (Fig. 4B), results in an increase in microtubule assembly rates (Fig. 5A). Very similarly, mimicking a constitutive phosphorylation on S308 (S308E mutant), but not the loss of S308 phosphorylation (S308A mutant), was sufficient to cause an increase in microtubule plus-end assembly rates (Fig. 5A and Fig. S6B). Importantly, although the increased rates of microtubule growth in cells expressing the S988A mutant can be suppressed by inhibiting Aurora-A, this suppression is not possible in cells expressing the S308E mutant (Fig. 5A). This result is in line with our findings showing that the S988A mutant increases centrosomal Aurora-A activity (Fig. S2B), whereas the S308 phosphorylation status does not affect Aurora-A activity (Fig. S6C). Thus, these findings suggest that the Aurora-A–mediated (S308) rather than the Chk2-mediated (S988) phosphorylation of BRCA1 represents the crucial trigger for abnormal microtubule dynamics in mitosis. To support the hierarchy of these two phosphorylations on BRCA1 further, we combined S988 and S308 mutations. In fact, increased microtubule assembly rates triggered by the loss of the Chk2-mediated phosphorylation of BRCA1 (S988A mutant) can be fully suppressed not only by Aurora-A inhibition (Fig. 5A) but also by concomitant loss of the Aurora-A–mediated phosphorylation site (S308A mutant) (Fig. 5B). On the other hand, mimicking the phosphorylation of S308 (S308E mutant) increases microtubule growth rates regardless of the phosphorylation status of S988 (S988A or S988E) (Fig. 5B). Moreover, expression of the BRCA1 mutant, which no longer can be phosphorylated by Aurora-A (S308A mutant), is sufficient to suppress the increase in microtubule growth in CHK2-deficient HCT116 cells as well as in SW620 and SW480 cells, where abnormal microtubule growth was shown to be dependent on increased Aurora-A activity (Fig. 5C) (6). Significantly, this suppression of abnormally increased microtubule growth also led to the suppression of the generation of lagging chromosomes during anaphase in those cells (Fig. 5D) indicating that the Aurora-A–mediated phosphorylation of BRCA1 on S308 indeed represents the key event that contributes to the increase in microtubule assembly rates leading to chromosome missegregation and CIN.

Fig. S6.

(A) Reconstitution of BRCA1 expression in stable BRCA1-knockdown cells. HCT116 cells stably carrying a plasmid expressing shRNAs targeting BRCA1 were transfected with plasmids encoding for WT BRCA1 or the indicated nonphosphorylatable or phospho-mimetic or combination mutants of BRCA1. Representative Western blots detecting BRCA1 are shown. (B) Microtubule assembly in bipolar mitotic spindles was measured in HCT116 cells reconstituted with WT BRCA1 or a S308E-BRCA1 mutant. Scatter dot plots show average assembly rates (20 microtubules per cell). Green dashed line, normal values; red dashed line, abnormally increased values. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; t test; n = 20 cells from three independent experiments. (C) Phosphorylation of BRCA1 on S308 does not influence Aurora-A activity on mitotic centrosomes. Detection of active Aurora-A (pT288) and centrin-2 at mitotic centrosomes in HCT116 cells with stable BRCA1 knockdown (BRCA1 shRNA) and after re-expression of WT BRCA1 (BRCA1-WT) or nonphosphorylatable (S308A) or phospho-mimetic (S308E) BRCA1 mutants. The signal intensities were normalized to signals from centrosomal centrin-2 and quantified. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; t test; n = 77 (WT), 82 (S308A), or 78 (S308E) cells. (D) Replacement of endogenous BRCA1 with the BRCA1-S308A mutant in HCT116-CHK2−/−, SW620, and SW480 cells. Cells were transfected with siRNAs targeting BRCA1, and BRCA1-WT or BRCA-S308A was re-expressed. Representative Western blots show the detection of BRCA1.

Fig. 5.

Aurora-A–mediated phosphorylation of BRCA1 increases mitotic microtubule assembly rates. (A) Phosphorylation of BRCA1 on S308 is sufficient to increase microtubule plus-end assembly rates during mitosis. Stable BRCA1-knockdown cells were reconstituted with BRCA1-WT or with BRCA1-S988A, -S308A, or -S308E mutants and were treated with DMSO (control) or 0.06 µM MLN8054 to inhibit Aurora-A activity partially. Average mitotic microtubule assembly rates are based on the analyses of 20 microtubules per cell. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; t test; n = 20 cells from three independent experiments. (B) Phosphorylation of BRCA1 on S308 is a key event in regulating microtubule assembly rates. Mitotic microtubule plus-end assembly rates were measured in stable BRCA1-knockdown cells after reconstitution with the indicated double mutants of BRCA1. Scatter dot plots show average assembly rates (20 microtubules per cell). Data are shown as mean ± SEM; t test; n = 20 cells from three independent experiments. (C) Loss of S308 phosphorylation of BRCA1 restores normal microtubule assembly rates in colorectal cancer cells. Microtubule plus-end growth rates were determined in HCT116-CHK2−/−, SW620, and SW480 cells with or without the replacement of endogenous BRCA1 with a BRCA1-S308A mutant. Scatter dot plots show average assembly rates (20 microtubules per cell). Data are shown as mean ± SEM; t test; n = 20 cells from three independent experiments. (D) Loss of the S308 phosphorylation of BRCA1 suppresses the generation of lagging chromosomes in colorectal cancer cells. HCT116-CHK2−/−, SW620, and SW480 cells with or without replacement of endogenous BRCA1 with a BRCA1-S308A mutant were synchronized in anaphase, and the proportion of cells exhibiting lagging chromosomes was determined. Green dashed line, normal values; red dashed lines, abnormally increased values. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; t test; n = 2–4 with a total of 200–400 anaphase cells evaluated.

Discussion

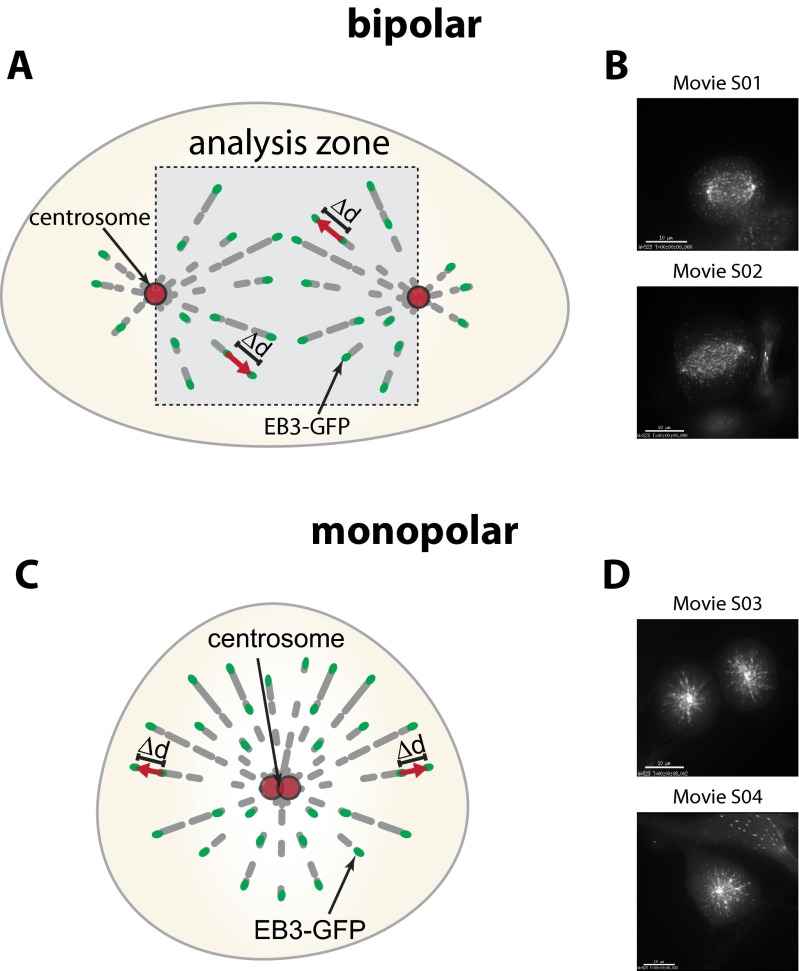

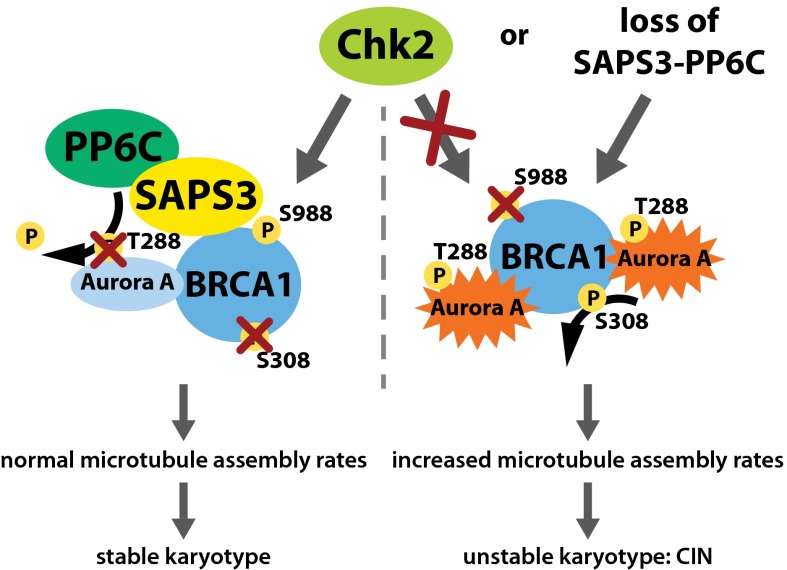

The tumor suppressor BRCA1 is an important regulator of mitosis, and its loss is tightly linked to whole-chromosome CIN and the generation of aneuploidy (4–6, 18). Importantly, BRCA1 can ensure chromosomal stability by dampening microtubule plus-end assembly rates during mitosis (6). Our work presented here uncovered a dual regulatory circuit that controls the mitotic function of BRCA1 to ensure proper microtubule plus-end assembly and chromosomal stability (see the model in Fig. 6). We found that mitotic BRCA1 is inactivated through phosphorylation on S308 by the oncogenic Aurora-A kinase, leading to an increase in microtubule assembly rates, the induction of chromosome missegregation, and CIN (6). In normal cells, however, this unscheduled inactivation of BRCA1 is prevented by the tumor suppressor CHK2, which phosphorylates BRCA1 on S988, leading to the recruitment of the SAPS3-PP6C protein phosphatase complex. The PP6 phosphatase, in turn, keeps BRCA1-bound Aurora-A activity low by dephosphorylating its T-loop autophosphorylation (11). Thus, PP6 protects BRCA1 from being inactivated by Aurora-A during mitosis.

Fig. 6.

Model summarizing the mitotic regulation of BRCA1 required for the maintenance of proper microtubule assembly and chromosomal stability. Aurora-A can inactivate the mitotic function of BRCA1 by direct phosphorylation on S308, resulting in increased microtubule assembly, chromosome missegregation, and CIN. During normal mitosis, however, BRCA1 is phosphorylated by Chk2 on S988, triggering the recruitment of the SAPS3-PP6 phosphatase complex to BRCA1 and thereby leading to dephosphorylation of Aurora-A restraining Brca1-bound Aurora-A activity. The limited Aurora-A activity, in turn, limits BRCA1 phosphorylation on S308 and thus, its inactivation. In cancer cells, the overexpression of oncogenic AURKA or the loss of the tumor suppressors CHK2 or PP6 leads to failure of this fail-safe mechanism and promotes the Aurora-A–dependent inactivation of BRCA1, resulting in CIN and aneuploidy as seen upon loss of BRCA1.

Currently, how BRCA1 dampens mitotic microtubule plus-end assembly is not known. However, possible targets of BRCA1 include proteins known as “+TIPs” that are localized to growing microtubule plus ends. +TIPs represent a protein network that shapes the microtubule plus ends and contributes to their dynamic behavior (19, 20). There is a growing list of +TIPs, but currently it is unclear how they act together to regulate microtubule dynamics (21, 22). Interestingly, we obtained the first evidence, to our knowledge, that the loss of the Chk2–BRCA1 axis might influence +TIPs. Increased microtubule plus-end growth upon loss of CHK2 can be suppressed by partial repression of the processive plus tip-associated microtubule polymerase ch-TOG (6), indicating that the polymerase might be either hyperactive or hyper-recruited to plus tips in the absence of Chk2–BRCA1. However, Aurora-A, Chk2, and BRCA1 are localized to mitotic centrosomes (10, 23, 24), raising the question of how centrosomal proteins can regulate events at microtubule plus tips. Interestingly, in addition to their localization at the plus tips, several +TIPs, including ch-TOG, also are localized at mitotic centrosomes (25). Although the function of +TIPs at centrosomes is unclear, it is interesting to speculate that the Chk2–BRCA1 pathway might modulate a centrosomal subpool of +TIPs that subsequently are recruited to the microtubule plus end where they regulate microtubule dynamics.

An important outcome from our work presented here is the identification of a regulatory network centered on the mitotic function of BRCA1 that is essential for the maintenance of chromosomal stability and therefore is important for our understanding of BRCA1-driven tumorigenesis and tumor progression (5, 26). Our results suggest that not only BRCA1, but also the positive BRCA1 regulators Chk2 and SAPS3-PP6, might represent important tumor-suppressor genes. Indeed, CHK2 is a tumor suppressor that frequently is down-regulated in lung and colorectal cancer, and its loss mimics the loss of BRCA1 and causes whole-chromosome missegregation and CIN (5, 6, 27, 28). Similarly, PP6C mutations that affect the formation of holoenzymes are detected in melanoma and have been shown to affect mitosis (29,30). On the other hand, Aurora-A can act as a negative regulator of BRCA1 in mitosis, and, as such, AURKA represents a well-established oncogene that is overexpressed in various human malignancies and is clearly associated with chromosome missegregation and CIN (6, 9, 10). In addition, recent work from our laboratories has identified the centrosomal protein Cep72 as a putative oncogene in colorectal cancer that can bind to BRCA directly and inhibits its mitotic function to regulate microtubule growth (14). In sum, our work not only reveals a key regulatory circuit on BRCA1 but also provides a network of cancer-associated genetic lesions that might contribute to the functional inactivation of BRCA1 during mitosis. These alterations of essential coregulators of BRCA1 might contribute to genome instability in tumor entities other than breast and ovarian cancer in which BRCA1 mutations are prevalent.

Materials and Methods

Human Cell Lines, Cell Treatments, Antibodies, cDNAs, and si/shRNAs.

Details on human cell lines, cell treatments, antibodies, cDNAs, and si/shRNAs are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Mass Spectrometry Analyses.

BRCA1 was immunoprecipitated from SILAC-labeled cells, and associated proteins were identified by mass spectrometry analyses as detailed in SI Materials and Methods.

Measurement of Microtubule Plus-End Assembly Rates.

Determination of microtubule plus-end assembly rates was described previously (6).

Statistical Analyses.

All data are shown as mean ± SEM. Where indicated, Student’s t tests were calculated by using the Prism software package, version 4 (GraphPad).

SI Materials and Methods

Human Cell Lines.

HCT116 and isogenic CHK2-deficient cells were a gift from Bert Vogelstein, John Hopkins University, Baltimore (31). RKO, SW620, and SW480 colorectal cancer cell lines were from ATCC. HCT116 cell lines with reduced BRCA1 expression (HCT116 + BRCA1 shRNA) were maintained as described in detail previously (5). All cell lines were cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium containing 10% FCS, 1% glutamine, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, and 100 U/mL penicillin (Sigma).

Cell Treatments and Cell-Cycle Synchronization.

To synchronize cells in mitosis, cells were treated with 2 µM dimethylenastron (Calbiochem) for 16 h or were synchronized at G1/S by a double thymidine block and were released into fresh medium for 8 h. For full and partial inhibition of Aurora-A activity, cells were treated with 0.5 µM or 0.06 µM MLN8054, respectively.

cDNAs.

HA-tagged BRCA1 cDNAs were kindly provided by Jay Chung, NIH, Bethesda (32). Mutated HA-tagged BRCA1 cDNAs (S308A, S308E, S988A-S308A, S988A-S308E, and S988E–S308E) were generated by PCR amplification on BRCA1-WT cDNA using the following oligonucleotides: BRCA1-S308A forward, 5′-CCGAATTCTGTAATAAGGCCAAACAGCCTGGC-3′; BRCA1-S308E forward, 5′-CTGAATTCTGTAATAAGGAGAAACAGCCTGGC-3′; and BRCA1 reverse, 5′-AAGGTACCAATGAAATACTGC-3′. The cDNA fragments obtained were cloned into pcDNA3-BRCA1 (WT, S988A, or S988E). pcDNA3-FLAG-SAPS3, kindly provided by David Brautigan, University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, VA (12), was used to express SAPS3. pcDNA3-HA-PP6C was described previously (13). pEGFP-EB3 was kindly provided by Linda Wordeman, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle.

siRNAs and shRNA Plasmids.

The following siRNA sequences were used:

Scrambled (control): 5′-CAUAAGCUGAGAUACUUCA-3′

SAPS3: 5′-GCUCAGAACCGCAAACUUAd(T)d(T)-3′

PP6C: 5′-AGACAGAUAACACAGGUCU-3′

BRCA1: 5′-GGAACCUGUCUCCACAAAGd(T)d(T)-3′

CHK2: 5′-CCUUCAGGAUGGAUUUGCCAAUC-3′

The shRNA expressing pSUPER plasmids targeting BRCA1 were described previously (5).

Transfections of Cell Lines.

Transient DNA transfections were carried out using polyethylenimine (PEI; Sigma) or by electroporation using a Bio-Rad electroporator at 300 V and 500 µF. All siRNA transfections were carried out using INTERFERin transfection reagent (Polyplus) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Generation of Phosphorylated S308-BRCA1–Specific Antibodies.

Rabbits were immunized by using a synthetic phosphopeptide spanning the region around S308 in the human BRCA1 sequence [KAEFCNKS(P)KQPGLARS]. Whole serum was used for affinity purification with the phosphopeptide and depletion against the nonphosphopeptide (Davids Biotechnologie).

SILAC Duplex Labeling and Immunoprecipitation.

HCT116 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing heavy or light Arg+Lys (SILAC-K6-R6-Kit; Silantes), and CHK2-deficient HCT116 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing only light Arg+Lys (SILAC-K6-R6-Kit; Silantes) for 4 wk. The labeled cells were synchronized in mitosis by treatment with 2 µM dimethylenastron (Calbiochem) for 16 h and were lysed in 50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.25% (vol/vol) Nonidet P-40, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 1 mM DTT, protease inhibitor, and phosphatase inhibitor mixtures (Roche). BRCA1 was immunoprecipitated from 14 mg of whole-cell lysate (H:L, 1:1 mix) using 12 µg anti-BRCA1 antibody (D-9; Santa Cruz) and protein-G Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare). Proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE and analyzed by LC-MS after tryptic in-gel-digestion.

LC-MS Peptide Analysis.

Peptides were loaded on an Acclaim PepMap 100 precolumn (100 µm × 2 cm, C18, 3 µm, 100 Å) (Thermo Scientific) at a flow rate of 25 µL/min for 6 min in 100% solvent A [98% water, 2% (vol/vol) acetonitrile, 0.07% (vol/vol) trifluoroacetic acid]. Analytical peptide separation by reverse-phase chromatography was performed on an Acclaim PepMap100 precolumn (75 µm × 25 cm, C18, 3 µm, 100 Å) (Thermo Scientific) running a gradient from 98% solvent A [water, 0.1% (vol/vol) formic acid] and 2% solvent B [80% (vol/vol) acetonitrile, 20% water, 0.1% (vol/vol) formic acid] to 42% solvent B within 95 min and to 65% solvent B within the next 26 min at a flow rate of 300 nL/min. (Solvents and acids were purchased from Fisher Chemicals.) Chromatographically eluting peptides were on-line ionized by nano-electrospray using the Nanospray Flex Ion Source (Thermo Scientific) at 2.4 kV and were continuously transferred into the mass spectrometer. Full scans within the mass range of 300–1,850 m/z were taken from the Orbitrap-FT analyzer at a resolution of 30.000 with parallel data-dependent top 10 MS2-fragmentation with the LTQ Velos Pro linear ion trap with collision-induced dissociation (Thermo Fisher). Data acquisition was performed with XCalibur 2.2 software (Thermo Fisher). Proteins were identified and quantified using the MaxQuant version 1.4.1.2 software (33) using a UniProt-derived Homo Sapiens-specific protein database. The resulting protein list was processed further using Perseus version 1.4.1.3 software (34).

Immunoprecipitation.

Cells were lysed in 50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.25% (vol/vol) Nonidet P-40, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 1 mM DTT, protease inhibitor, and phosphatase inhibitor mixtures (Roche). Two milligrams of the lysate was incubated with 1.5 µg anti-Brca1 (D-9; Santa Cruz) or 0.5 µg anti-TPX2 (18D5; Santa Cruz) antibodies, and immunocomplexes were precipitated using protein-G Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare).

Western Blotting.

Cells were lysed in lysis buffer [50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, 1% (vol/vol) Nonidet P-40, 0.1% (wt/vol) SDS, 0.1% sodium desoxycholate, protease inhibitor, and phosphatase inhibitor mixtures (Roche)]. Proteins were resolved on 7.5% or 12% SDS polyacrylamide gels and blotted onto nitrocellulose or PVDF membranes (GE Healthcare) using semidry or tank-blot procedures. For Western blot experiments the following antibodies and dilutions were used: anti-Chk2 (1:800; DCS-270; Santa Cruz); anti–β-actin (1:40,000; AC-15; Sigma); anti-Brca1 (1:500; C-20 or D-9; Santa Cruz); anti–Brca1–pS308 (1:100, this study); anti-BARD1 (1:300; H300; Santa Cruz); anti–Aurora-A (1:2,000; H130; Santa Cruz); anti–phospho-T288–Aurora-A (1:2,000; Cell Signaling); anti–phospho-Aurora-A (pT288), -B (pT232), -C (pT198) (1:2,000; Cell Signaling); anti-TACC3 (1:1,000; H300; Santa Cruz); anti–phospho-S558-TACC3 (1:1,000; D8H10; Cell Signaling); anti-SAPS3 (1:500; Bethyl Laboratories); anti-TPX2 (1:800; 18D5, Santa Cruz); anti-FLAG (1:1,000; Santa Cruz); and anti-PP6C (1:1,000; Bethyl Laboratories). For immunodetection secondary anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibodies conjugated to HRP were used (1:10,000) (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Proteins were detected by enhanced chemoluminescence. Quantification of Western blot bands was performed using the Image J software (NIH).

Immunofluorescence Microscopy.

Cells were synchronized by a double thymidine block and after a release of 8 h were fixed with methanol at −20 °C for 6 min. The following antibodies and dilutions were used for immunofluorescence microscopy experiments: anti–Aurora-A (1:500; H130, Santa Cruz); anti–phospho-T288-Aurora-A (1:200; Cell Signaling); and anti–centrin-2 (1:250; Abcam). Secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor-488/-594 (1:1,000; Molecular Probes) were used. Microscopy of fixed cells was performed on a DeltaVision-ELITE microscope (Applied Precision/GE Healthcare) equipped with a PCO Edge scientific complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (sCMOS) camera (PCO). Images were recorded with a z-optical spacing of 0.2 µm and were analyzed for signal intensity. Pixel quantification of the centrosomal signals of total and active Aurora A was carried out using softWoRx 5.0 software (Applied Precision) and was normalized to signal intensities derived from centrosomal signals for centrin-2.

Measurement of Microtubule Plus-End Assembly Rates.

Cells were transfected with pEGFP-EB3 and treated with 2 µM dimethylenastron (Calbiochem) for 2 h (monopolar spindles) or were left untreated (bipolar metaphase spindles). Four sections with a z-optical spacing of 0.4 µm were taken every 2 s using a DeltaVision Elite microscope and a PCO Edge sCMOS camera (PCO) at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Images were deconvolved using softWoRx 6.0 software (Applied Precision). Average microtubule assembly rates (in micrometers per minute) were calculated on data received for 20 individual microtubules per cell (n = 20–30 cells).

Detection of Lagging Chromosomes During Anaphase.

The proportion of cells exhibiting lagging chromosomes during anaphase were determined as described previously (6).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Bert Vogelstein, Jay Chung, David Brautigan, and Linda Wordeman for plasmids and cell lines; Heike Krebber for sharing equipment and reagents; and Franziska Fries and Eric Schoger for general laboratory support. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (H.B. and G.H.B.) and by DFG Grant KFO179 (to H.B.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. D.P. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1525129113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Silver DP, Livingston DM. Mechanisms of BRCA1 tumor suppression. Cancer Discov. 2012;2(8):679–684. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Savage KI, Harkin DP. BRCA1, a ‘complex’ protein involved in the maintenance of genomic stability. FEBS J. 2015;282(4):630–646. doi: 10.1111/febs.13150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu Q, et al. BRCA1 tumour suppression occurs via heterochromatin-mediated silencing. Nature. 2011;477(7363):179–184. doi: 10.1038/nature10371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joukov V, et al. The BRCA1/BARD1 heterodimer modulates ran-dependent mitotic spindle assembly. Cell. 2006;127(3):539–552. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stolz A, et al. The CHK2-BRCA1 tumour suppressor pathway ensures chromosomal stability in human somatic cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(5):492–499. doi: 10.1038/ncb2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ertych N, et al. Increased microtubule assembly rates influence chromosomal instability in colorectal cancer cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16(8):779–791. doi: 10.1038/ncb2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kais Z, Parvin JD. Regulation of centrosomes by the BRCA1-dependent ubiquitin ligase. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7(10):1540–1543. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.10.7053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stolz A, Ertych N, Bastians H. Loss of the tumour-suppressor genes CHK2 and BRCA1 results in chromosomal instability. Biochem Soc Trans. 2010;38(6):1704–1708. doi: 10.1042/BST0381704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bischoff JR, et al. A homologue of Drosophila aurora kinase is oncogenic and amplified in human colorectal cancers. EMBO J. 1998;17(11):3052–3065. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marumoto T, Zhang D, Saya H. Aurora-A - a guardian of poles. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(1):42–50. doi: 10.1038/nrc1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeng K, Bastos RN, Barr FA, Gruneberg U. Protein phosphatase 6 regulates mitotic spindle formation by controlling the T-loop phosphorylation state of Aurora A bound to its activator TPX2. J Cell Biol. 2010;191(7):1315–1332. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201008106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stefansson B, Brautigan DL. Protein phosphatase 6 subunit with conserved Sit4-associated protein domain targets IkappaBepsilon. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(32):22624–22634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601772200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bastians H, Ponstingl H. The novel human protein serine/threonine phosphatase 6 is a functional homologue of budding yeast Sit4p and fission yeast ppe1, which are involved in cell cycle regulation. J Cell Sci. 1996;109(Pt 12):2865–2874. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.12.2865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lüddecke S, et al. The putative oncogene CEP72 inhibits the mitotic function of BRCA1 and induces chromosomal instability. Oncogene. 2015 doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kinoshita K, et al. Aurora A phosphorylation of TACC3/maskin is required for centrosome-dependent microtubule assembly in mitosis. J Cell Biol. 2005;170(7):1047–1055. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200503023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LeRoy PJ, et al. Localization of human TACC3 to mitotic spindles is mediated by phosphorylation on Ser558 by Aurora A: A novel pharmacodynamic method for measuring Aurora A activity. Cancer Res. 2007;67(11):5362–5370. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stepanova T, et al. Visualization of microtubule growth in cultured neurons via the use of EB3-GFP (end-binding protein 3-green fluorescent protein) J Neurosci. 2003;23(7):2655–2664. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02655.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu X, et al. Centrosome amplification and a defective G2-M cell cycle checkpoint induce genetic instability in BRCA1 exon 11 isoform-deficient cells. Mol Cell. 1999;3(3):389–395. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80466-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galjart N. Plus-end-tracking proteins and their interactions at microtubule ends. Curr Biol. 2010;20(12):R528–R537. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akhmanova A, Steinmetz MO. Tracking the ends: A dynamic protein network controls the fate of microtubule tips. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(4):309–322. doi: 10.1038/nrm2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta KK, Alberico EO, Näthke IS, Goodson HV. Promoting microtubule assembly: A hypothesis for the functional significance of the +TIP network. BioEssays. 2014;36(9):818–826. doi: 10.1002/bies.201400029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tamura N, Draviam VM. Microtubule plus-ends within a mitotic cell are ‘moving platforms’ with anchoring, signalling and force-coupling roles. Open Biol. 2012;2(11):120132. doi: 10.1098/rsob.120132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsvetkov L, Xu X, Li J, Stern DF. Polo-like kinase 1 and Chk2 interact and co-localize to centrosomes and the midbody. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(10):8468–8475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211202200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsu LC, White RL. BRCA1 is associated with the centrosome during mitosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(22):12983–12988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.12983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang K, Akhmanova A. Microtubule tip-interacting proteins: A view from both ends. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23(1):94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ricke RM, van Ree JH, van Deursen JM. Whole chromosome instability and cancer: A complex relationship. Trends Genet. 2008;24(9):457–466. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cybulski C, et al. CHEK2 is a multiorgan cancer susceptibility gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75(6):1131–1135. doi: 10.1086/426403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang P, et al. CHK2 kinase expression is down-regulated due to promoter methylation in non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer. 2004;3:14. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-3-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hammond D, et al. Melanoma-associated mutations in protein phosphatase 6 cause chromosome instability and DNA damage owing to dysregulated Aurora-A. J Cell Sci. 2013;126(Pt 15):3429–3440. doi: 10.1242/jcs.128397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gold HL, et al. PP6C hotspot mutations in melanoma display sensitivity to Aurora kinase inhibition. Mol Cancer Res. 2014;12(3):433–439. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jallepalli PV, Lengauer C, Vogelstein B, Bunz F. The Chk2 tumor suppressor is not required for p53 responses in human cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(23):20475–20479. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213159200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee JS, Collins KM, Brown AL, Lee CH, Chung JH. hCds1-mediated phosphorylation of BRCA1 regulates the DNA damage response. Nature. 2000;404(6774):201–204. doi: 10.1038/35004614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cox J, et al. Andromeda: A peptide search engine integrated into the MaxQuant environment. J Proteome Res. 2011;10(4):1794–1805. doi: 10.1021/pr101065j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cox J, Mann M. 1D and 2D annotation enrichment: A statistical method integrating quantitative proteomics with complementary high-throughput data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13(Suppl 16):S12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-S16-S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu, et al. Identification of a RING protein that can interact in vivo with the BRCA1 gene product. Nat Genet. 1996;14(4):430–440. doi: 10.1038/ng1296-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cantor, et al. BACH1, a novel helicase-like protein, interacts directly with BRCA1 and contributes to its DNA repair function. Cell. 2001;105(1):149–160. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00304-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stecklein SR, et al. BRCA1 and HSP90 cooperate in homologous and non-homologous DNA double-strand-break repair and G2/M checkpoint activation. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(34):13650–13655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203326109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.