Virus persistence is increased by NK cells that inhibit antiviral CD4+ TFH cells and early B cell responses.

Keywords: host defense, antibody, immune regulation, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, mice

Abstract

There is a need to understand better how to improve B cell responses and immunity to persisting virus infections, which often cause debilitating illness or death. People with chronic virus infection show evidence of improved virus control when there is a strong neutralizing antibody response, and conversely, B cell dysfunction is associated with higher viral loads. We showed previously that NK cells inhibit CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses to disseminating LCMV infection and that depletion of NK cells attenuates chronic infection. Here, we examined the effect of NK cell depletion on B cell responses to LCMV infection in mice. Whereas mice infected acutely generated a peak level of antibody soon after the infection was resolved, mice infected chronically showed a continued increase in antibody levels that exceeded those after acute infection. We found that early NK cell depletion rapidly increased virus-specific antibody levels to chronic infection, and this effect depended on CD4+ T cells and was associated with elevated numbers of CXCR5+CD4+ TFH cells. However, the NK cell-depleted mice controlled the infection and by 1 mo pi, had lower TFH cell numbers and antibody levels compared with mice with sustained infection. Finally, we show that NK cell depletion improved antiviral CD8+ T cell responses only when B cells and virus-specific antibody were present. Our data indicate that NK cells diminish immunity to chronic infection, in part, by suppressing TFH cell and antibody responses.

Introduction

Chronic virus infections cause significant health burdens worldwide [1]. In the absence of treatment, these viruses can lead to AIDS in the case of HIV or cirrhosis and liver cancer in the cases of HBV and HCV. The balance between infection control versus persistence hinges on the effectiveness of adaptive immune responses. However, T and B cell responses to infection are tightly regulated through complex mechanisms that need to be better unraveled. A deeper understanding of the cellular and molecular processes that limit antiviral immune responses is needed to develop novel therapeutic approaches to treat infection.

Small animal models have been especially helpful in unraveling how chronic virus infections affect adaptive immune responses. As there are variants of LCMV that differ in the ability to persist in mice, this model has been particularly useful for understanding the immunobiology of acute versus chronic infection. In this model, it has been shown that immune responses to chronic virus infections develop normally early on but typically, become ineffective within days. Some virus-specific T cell populations decline excessively in number, leading to small pools of cells that cannot eliminate infection. Other virus-specific T cell populations are maintained across time in a dysfunctional state; these “exhausted” cells are characterized by poor cytokine output, weak cytolytic activity, and impaired proliferative capacity [2, 3]. Importantly, the T cell exhaustion process has also been observed in humans persistently infected with chronic viruses [1]. The underlying mechanisms causing these effects are still being unraveled, but current evidence shows that T cell-based immunity is undermined by excessive TCR signaling as a result of prolonged periods of exposure to antigen [4–7], sustained inflammatory signals from type I IFNs [8–10], elevated levels of suppressive cytokines [11, 12], and the expression of inhibitory surface receptors, including PD-1, LAG-3, and others [13, 14]. CD4+ T cells improve control of persistent infection [15, 16], in part, as a result of their expression of IL-21, which directly sustains virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses [17–19]. CD4+ TFH cells are thought to enhance somatic hypermutation in B cells that leads to high-affinity antibody and neutralizing antibody [20, 21]. Recently, our laboratory [22] and others [23–26] have identified a role for NK cells in modulating CD8+ and CD4+ T cell responses during disseminating LCMV infection. Through direct effects on CD8+ T cells and indirect mechanisms through APCs and CD4+ T cells, NK cells dramatically reduce CD8+ T cell responses, leading to T cell exhaustion and virus persistence.

B cells have also been shown in mouse models to play a critical role in immune protection against disseminated virus infection in mice [27–31], partly as a result of their role in sustaining T cell responses [27, 28] and their expression of virus-specific antibody [32–35]. Additionally, in patients with HIV, B cells often become dysfunctional or are deleted during chronic infection [36, 37], which may perpetuate the infection. Conversely, there is a positive correlation between individuals who develop robust, broadly neutralizing antibody and protection against HIV [20, 38]. It is well established that neutralizing antibody is important for protection against infections, but virus-specific, non-neutralizing antibody also contributes to the clearance of chronic virus infection in mice [32–35]. Beyond antibody production, B cells improve cellular immunity to infection. B cells contribute to the development of lymphoid organ structures before infection, thus impacting the number of T cells that are available to respond to infection and the number of type 1 IFN-producing cells [39]. B cells are needed for optimal TFH responses, and they sustain memory and effector T cell responses following acute infection [27, 28]. B cells play a critical role during chronic virus infections. For example, BCKO mice are unable to resolve chronic virus infection [27–31]. Furthermore, BCR-transgenic mice that have normal frequencies of B cells but cannot make LCMV-specific antibody show prolonged viral persistence following infection with widely disseminating strains of LCMV [32, 34]. Thus, B cells can foster cellular immune responses through the expression of cytokines, costimulatory molecules, and MHC molecules. However, B cells can show functional deficiencies during chronic virus infection [36, 37], which may compromise protection. Thus, there is a need to understand better how to increase B cell responses and immune protection against persistent infection.

Given that NK cells limit antiviral CD4+ T cell responses and that CD4+ T cells drive B cell and CD8+ T cell responses, we examined whether NK cells interfere with B cell responses during chronic LCMV infection. Here, we show that NK cell depletion increased the number of TFH cells during the early stages of infection, resulting in a greater GC B cell response and higher T-dependent antiviral antibody levels at early times compared with NK cell-replete mice. The enhanced humoral immune response following NK cell depletion contributed toward improved virus clearance and the prevention of CD8+ T cell exhaustion. At later times, however, the removal of NK cells resulted in reduced TFH and B cell responses, presumably as a result of the diminished levels of infectious virus. Thus, NK cells have diverse functions in shaping humoral immune responses during chronic virus infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and virus

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and bred as a colony at UNC-Chapel Hill. The BCR transgenic VH12/Vκ4 mice were generated and provided by Dr. Steve Clarke (UNC-Chapel Hill) [40]. The depletion of NK cells was accomplished by intraperitoneal administration of 2 doses of 75 μg anti-NK1.1 (PK136; Bio X Cell, West Lebanon, NH, USA) on days −3 and −2; control mice were administered either 2 doses of 75 μg mouse IgG2a isotype control (C1.18.4; Bio X Cell) or PBS. The depletion of CD4+ T cells was accomplished by intraperitoneal administration of 2 doses of 250 μg anti-CD4 (GK1.5; Bio X Cell) on days −1 and 2; control mice were administered 2 doses of 250 μg rat IgG2b isotype control (LTF-2; Bio X Cell). The depletion of CD8+ T cells was accomplished by intraperitoneal administration of 2 doses of 250 μg anti-CD8a (2.43; Bio X Cell) on days −1 and 3; control mice were administered 2 doses of 250 μg rat IgG2b isotype control (LTF-2; Bio X Cell). Viral stocks of plaque-purified LCMV were prepared from infected BHK-21 monolayers. Adult mice (8–10 wk old) were infected by intravenous administration of 2 × 106 PFU of LCMV-Clone13 or intraperitoneal administration of 2 × 105 PFU of LCMV-Armstrong. Infectious LCMV in serum, liver, lung, and kidney was quantified by plaque assay on Vero cell monolayers, as described previously [41]. All mouse experiments were performed in accordance with the UNC-Chapel Hill Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Quantitation of anti-LCMV antibody

Virus-specific Igs were measured by ELISA [42]. ELISA plates (Greiner Bio-One, Monroe, NC, USA) were coated with cell lysate prepared from LCMV-infected BHK-21 cells. Clarified sera were diluted and added to the wells. The following antibodies were used for detection of antiviral antibodies: total IgM and IgG were detected with HRP-conjugated goat polyclonal antibody to mouse IgM and IgG, respectively (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA); IgG1 was detected with biotin-XX-goat anti-mouse IgG1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and HRP-avidin D (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA); and IgG2c was detected with HRP-conjugated AffiniPure goat anti-mouse IgG Fcγ subclass 2c (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA). The highest dilution at which the OD value reached 1.5, which was roughly equivalent to half of the maximal response, was calculated to determine the amount of LCMV-specific antibody in each sample.

Flow cytometry and intracellular cytokine staining

Single-cell leukocyte suspensions were prepared from spleens, and erythrocytes were removed by use of ammonium-chloride-potassium lysing buffer (Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA). Single-cell suspensions of splenocytes were surface stained with combinations of fluorescently labeled mAb that are specific for B220 (RA3-6B2), CD4 (RM4-5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD19 (6D5), CD44 (IM7), CD62L (MEL-14), CD84 (mCD84.7), CD138 (281-2), Fas (Jo2; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), GL7 (GL7; eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), ICOS (7E.17G9), IFN-γ (XMG1.2), IgD (11-26c.2a), LAG-3 (C9B7W), NK1.1 (PK136), PD-1 (RMP1-30), SLAMF6 (330-AJ), Thy1.1 (HIS5.1; eBioscience), and TNF-α (MPG-XT22). For CXCR5 staining, the primary CXCR5 antibody (2G8; BD Biosciences) was used in combination with PE-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG or biotin-conjugated AffiniPure goat anti-rat IgG (H+L; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories), followed by streptavidin-allophycocyanin conjugate (Invitrogen). All antibodies were purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA), except where indicated. The Db/GP33–41 and I-Ab/GP66–77 tetramers were provided by the NIH Tetramer Core facility at Emory University (Atlanta, GA, USA). The intracellular cytokine staining assay was performed as described previously [43, 44]. In brief, splenocytes were stimulated ex vivo with LCMV peptides for 5–6 h in the presence of brefeldin A, followed by surface staining for CD8, fixation, permeabilization, and staining for IFN-γ and TNF. Cell staining was analyzed by 4-color flow cytometry by use of a BD Biosciences FACSCalibur and analyzed by FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR, USA).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by use of Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) with the use of an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test to evaluate the significance of differences between groups. Significance levels are indicated in the figure legends.

RESULTS

NK cell depletion improves early antibody responses to chronic virus infection by increasing virus-specific CD4+ TFH cell number

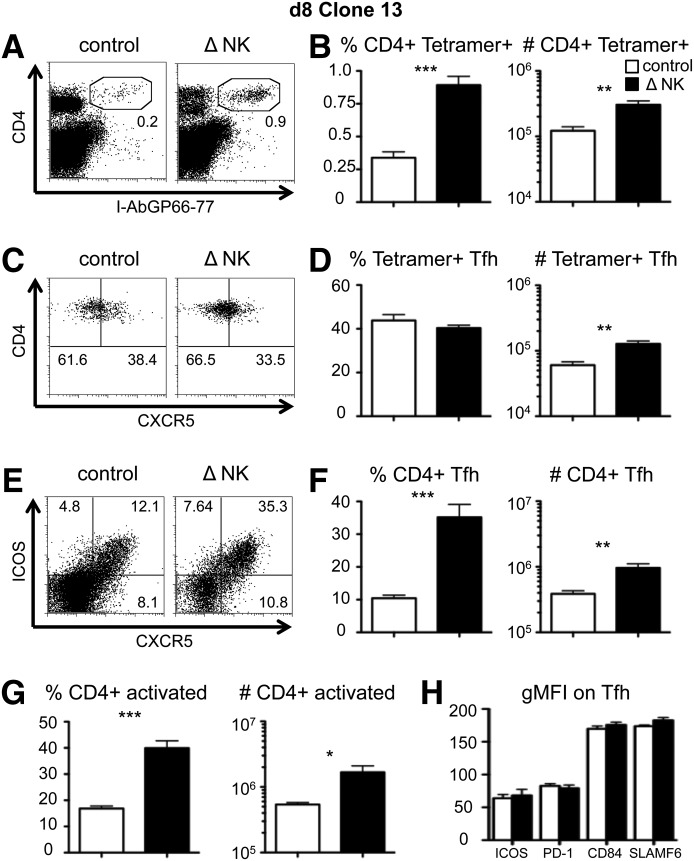

NK cells restrict the total CD4+ T cell response [22, 23, 45], but their effects specifically on TFH cells have not been reported. As expected, NK cell depletion increased the expansion of Clone13-specific CD4+ T cells, as detected by increases in the frequency and total number of I-Ab GP66–77 tetramer staining cells at day 8 pi (Fig. 1A and B). We measured CXCR5 expression on the tetramer+ cells to determine whether NK cell depletion modulated differentiation into the TFH subset (Fig. 1C). The percentage of tetramer+ CD4+ T cells that expressed CXCR5 was unchanged by NK cell depletion (Fig. 1D); however, as a result of the increased accumulation of tetramer+ cells (Fig. 1B), there was a parallel 2- to 3-fold increase in the total number of LCMV-specific TFH cells (Fig. 1D). Similar results were seen when we followed adoptively transferred TCR-transgenic SMARTA CD4+ T cells that recognize the same epitope as the endogenous tetramer+ cells. NK cell depletion concomitantly increased the total number of SMARTA CD4+ T cells and the number of CXCR5+ SMARTA CD4+ T cells without affecting the relative frequency of SMARTA cells expressing CXCR5 (data not shown). To extend our analysis to include CD4+ T cells of other specificities (tetramer+ and others), we measured the total number of TFH cells in mice following Clone13 infection in the presence or absence of NK cells. We found that the frequencies and total numbers of TFH cells and activated CD4+ T cells increased 3-fold following NK cell depletion (Fig. 1E–G). In all CD4+ T cell populations measured (total CD4, tetramer+, SMARTA), there were no apparent differences in the expression of the TFH effector proteins ICOS, PD-1, CD84, and SLAMF6 in the presence or absence of NK cells (Fig. 1H, and data not shown), suggesting that NK cells do not alter the cell-surface phenotype of TFH cells. Nevertheless, further analyses of transcription factor expression in these CD4+CXCR5+ cells, their localization in GC regions, and their ability to help B cell differentiation directly are required to rule out conclusively a role for NK cells in regulating TFH lineage specification. Thus, NK cells limit the magnitude of the TFH cell population by modulating the overall number of virus-specific CD4+ T cells and do not appear to restrict the TFH subset specifically.

Figure 1. NK cells reduce the early CD4+ TFH cell response during chronic virus infection.

WT B6 mice were treated with PK136 (Δ NK) or control antibody at days −2 and −3 before infection with Clone13. Splenocytes were harvested at day 8 pi for analysis. (A) An example of CD4 and I-Ab/GP66–77 tetramer staining of live splenocytes. (B) The I-Ab/GP66–77 tetramer+ CD4+ T cell frequency among all splenocytes (left) and the total number of I-Ab/GP66–77 tetramer+ CD4+ T cells (right) in the spleen. (C) An example of CD4 and CXCR5 expression on gated CD4+ I-Ab/GP66–77+ CD8− CD19− cells. (D) The percentage of CXCR5+ cells among tetramer+ CD4 cells (left) and the total number of I-Ab/GP66–77 tetramer+ TFH cells (right)/spleen. (E) An example of CXCR5 and ICOS staining on all CD4+ CD8− CD19− cells. (F) The CXCR5+ ICOS+ cell frequency among CD4+ T cells (left) and the total number of CXCR5+ ICOS+ TFH cells (right)/spleen. (G) The CD44hi CD62Llo (activated) cell frequency among all CD4+ T cells (left) and total number of activated CD4+ T cells (right) in the spleen. (H) The geometric mean fluorescence intensity (gMFI) of the indicated TFH cell markers on CXCR5+ CD4+ CD8− CD19− cells. The data represent 6–9 mice from 3 experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

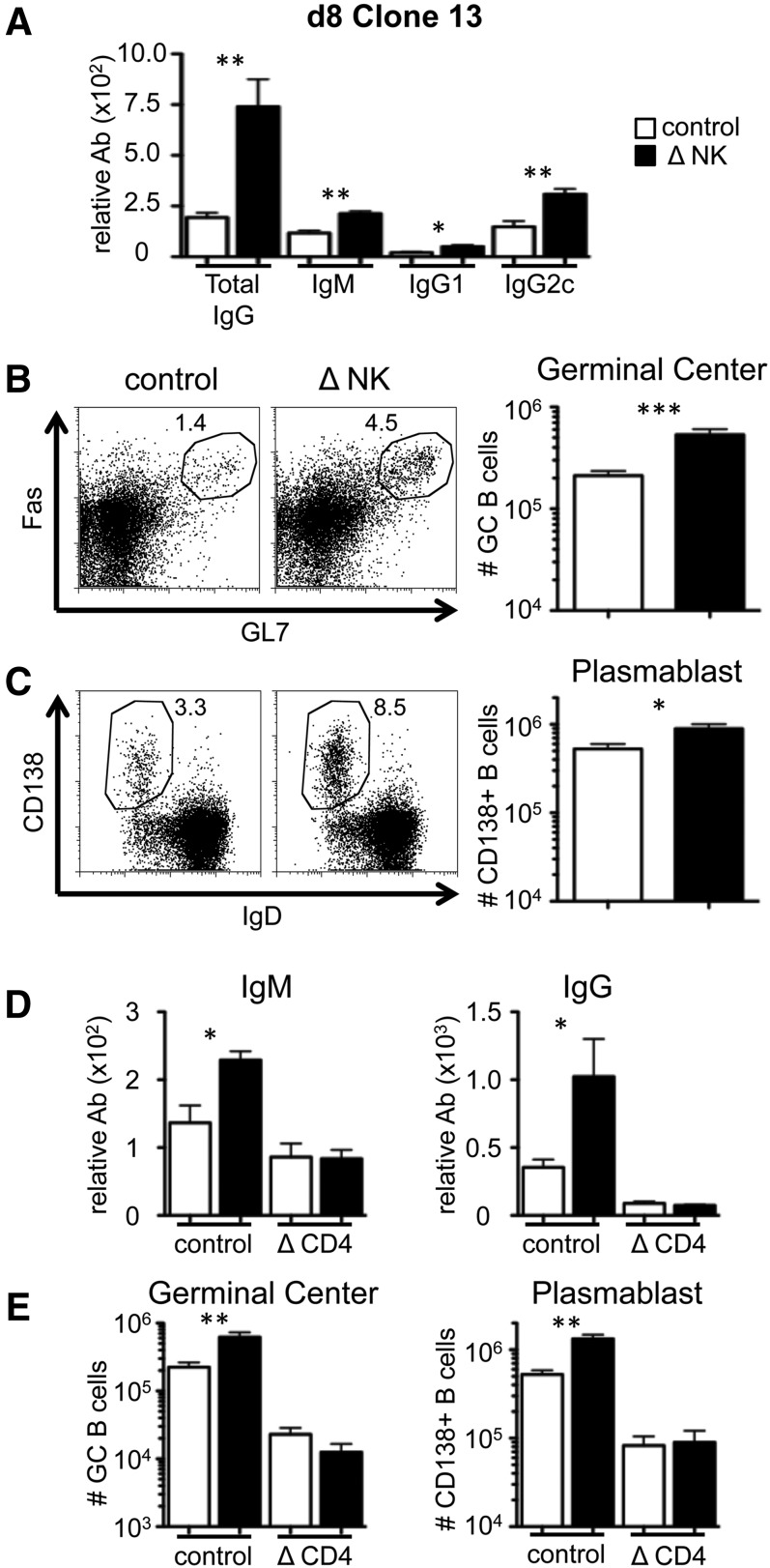

To determine whether the enhanced TFH response following NK cell depletion impacted the B cell response, we measured serum anti-LCMV antibodies and the frequencies of activated B cells in the presence or absence of NK cells. At day 8 following Clone13 infection, NK cell depletion enhanced the level of anti-LCMV IgG by 4-fold (Fig. 2A). NK cell depletion increased IgG1 and IgG2c isotypes, as well as virus-specific IgM (Fig. 2A). Consistent with the increase in antibody production, there was a 2- to 3-fold increase in the frequency and number of GC-phenotype B cells (Fig. 2B) and CD138+ IgD− plasmablast cells (Fig. 2C) in the absence of NK cells. These data indicate that NK cells negatively regulate B cell responses during the early stages of disseminated viral infection.

Figure 2. NK cell depletion enhances early B cell responses during chronic virus infection.

WT B6 mice were treated with PK136 (Δ NK) or control antibody at days −2 and −3 before infection with Clone13. (A) The serum levels of anti-LCMV total IgG, IgM, IgG1, and IgG2c at day 8 pi were measured by ELISA. (B) An example of Fas and GL7 staining on gated B220+ cells (left) and the total number of GC B cells (right) within the spleen at day 8. (C) An example of CD138 and IgD staining on gated B220+ cells (left) and the total number of plasmablast B cells (right) within the spleen at day 8. The data represent 6–9 mice from 3 experiments. (D and E) In addition to NK cell depletion, some mice were treated with GK1.5 (Δ CD4) or control antibody at day −1 before infection and day 2 to remove CD4+ T cells. (D) The serum levels of anti-LCMV IgM (left) and total IgG (right) at day 8 pi. (E) The total number of GC (left) and plasmablast (right) B cells in the spleen at day 8 pi. The data represent 6 mice from 2 experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

The data in Fig. 1 show that NK cells regulate CD4+ TFH cells during chronic virus infection, which may explain the improved IgG, GC, and plasmablast responses when NK cells are removed (Fig. 2A–C). However, it could be that B cells are direct targets of NK cell-mediated activities. Therefore, we examined whether NK cell depletion improves antibody responses that are independent of TFH cells. Cohorts of mice were treated with GK1.5 antibody to deplete CD4+ T cells or with isotype antibody, followed by NK cell depletion and infection. Virus-specific antibody responses were measured at day 8 pi with Clone13. Whereas CD4+ T cell depletion modestly reduced the virus-specific IgM response, there was a major decrease in IgG levels (Fig. 2D). In CD4-replete mice, NK cell depletion improved IgM and IgG responses (Fig. 2D). However, NK cell depletion in CD4+ T cell-deficient mice failed to improve antibody levels (Fig. 2D). NK cell depletion also did not increase the numbers of GC and plasmablast B cells in CD4+ T cell-deficient mice (Fig. 2E). Thus, NK cells constrain T-help-dependent B cell responses but do not regulate T-help-independent B cell responses, which suggests that “unhelped” B cells are not direct targets of NK cells.

To determine whether NK cell depletion would influence incipient TFH and B cell responses and hasten the production of antiviral antibodies, we quantified tetramer+ and total CD4+ TFH cells at day 5 of Clone13 infection. Similar to day 8, the size of the LCMV-specific CD4+ response was greatly enhanced by NK cell depletion without affecting the frequency of tetramer+ cells that expressed CXCR5 (Supplemental Fig. 1A–D). The total number of tetramer+ TFH cells was enhanced as a result of the increased accumulation of all CD4+ T cells (Supplemental Fig. 1B and D). The frequency and magnitude of the total CD4+ TFH cell population (including cells that do not bind the I-AbGP66–77 tetramer) were also elevated at day 5 following NK cell depletion (Supplemental Fig. 1E and F). Consistent with the large TFH response, the NK cell depletion increased the number of GC B cells and the serum levels of IgG, although the number of splenic CD138+ plasmablast cells appeared unaffected (Supplemental Fig. 1G and H). These data indicate that NK cells reduce the early stages of the adaptive immune response, including virus-specific antibody.

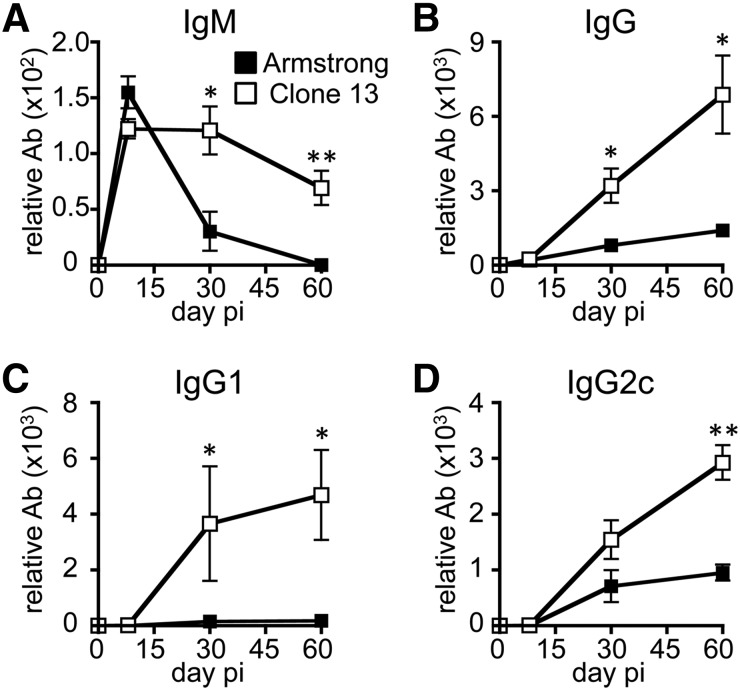

NK cell depletion promotes virus clearance, leading to lower antibody levels at late stages of infection

CD4+ T cells maintain their ability to stimulate antibody production from B cells for an extended time during chronic infection [46, 47]. Multiple reports have shown that CD4+ T and B cell antibody production are crucial for the eventual resolution of chronic virus infections [30, 32–35, 48, 49]. We characterized the effects of virus persistence on B cell function by infecting mice with LCMV variants that result in acute (Armstrong) or persistent (Clone13) infection and measured anti-LCMV antibodies in the serum. Following acute infection, virus-specific IgM levels peaked 1 wk after infection and then declined to the limits of detection of the assay with time (Fig. 3A). In contrast, Clone13 induced a similar initial level of IgM at 1 wk, but this level was sustained for at least 2 mo (Fig. 3A). Following acute infection, virus-specific IgG increases in the serum for 2–3 wk before stabilizing [42]. Consistent with that pattern, there was an increase in antiviral IgG between days 8 and 30, with little to no further increase in antibody afterward (Fig. 3B). Most of the virus-specific antibody following Armstrong infection was of the IgG2c subtype (Fig. 3D, and data not shown). By comparison, Clone13 infection resulted in enhanced virus-specific IgG levels overall (Fig. 3B), and IgG1 and IgG2c subtypes were elevated compared with the mice infected acutely (Fig. 3C and D). Thus, the continued presence of virus during Clone13 infection enhances B cell IgG production and sustains IgM production.

Figure 3. Persistent infection enhances serum levels of antiviral antibody over time.

WT B6 mice were infected with LCMV-Armstrong or -Clone13. The serum levels of anti-LCMV IgM (A), total IgG (B), IgG1 (C), and IgG2c (D) at days 8, 29, and 60 pi were measured by ELISA. The data represent 6 mice from 2 experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

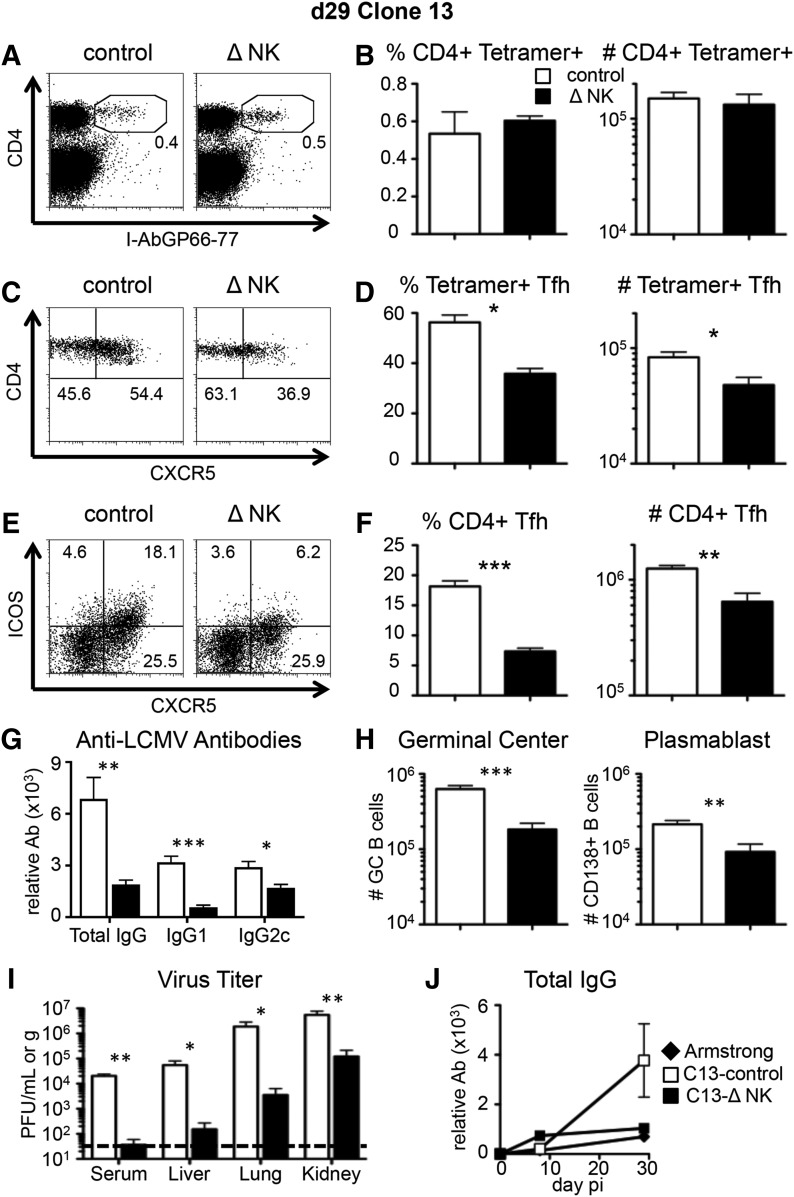

To evaluate whether early NK cell depletion has long-lasting effects on TFH cell abundance and antibody level, we measured CXCR5 expression on LCMV-specific CD4+ T cells at day 29 pi. At this later time-point, there was no difference in the frequency or total number of tetramer+ CD4 cells in the 2 groups (Fig. 4A and B). In contrast to day 8, however, the frequency of LCMV-specific CXCR5+ cells at day 29 was lower in mice depleted of NK cells, and there were fewer tetramer+ TFH cells (Fig. 4C and D). Similar results were seen when we extended the analysis to include all CD4+ T cells, as the frequency and total number of TFH cells were higher in the presence of NK cells (Fig. 4E and F). Therefore, NK cell depletion before infection inhibits the outgrowth of TFH cells that occurs during the later stages of chronic infection [46].

Figure 4. NK cell depletion reduces TFH cell responses at later times during chronic virus infection.

WT B6 mice were treated with PK136 (Δ NK) or control antibody at days −2 and −3 before infection with LCMV-Clone13. Splenocytes were harvested at day 29 pi for analysis. (A) An example of CD4 and I-Ab/GP66–77 tetramer staining on all splenocytes. (B) The I-Ab/GP66–77 tetramer+ CD4 cell frequency among all splenocytes (left) and the total number of I-Ab/GP66–77 tetramer+ CD4 T cells (right) within the spleen at day 29. (C) An example of CD4 and CXCR5 staining on gated CD4+ I-Ab/GP66–77 + CD8− CD19− cells. (D) The CXCR5+ cell frequency among tetramer+ CD4 cells (left) and the total numbers of I-Ab/GP66–77 tetramer+ TFH cells within the spleen at day 29. (E) An example of CXCR5 and ICOS staining on bulk-gated CD4+ CD8− CD19− cells. (F) The CXCR5+ ICOS+ cell frequency among CD4+ T cells (left) and the total numbers of CXCR5+ ICOS+ TFH cells within the spleen at day 29 (right). (G) The serum levels of anti-LCMV total IgG, IgG1, and IgG2c were measured by ELISA. (H) The total number of GC B cells (left) and plasmablast B cells (right)/spleen. (I) The level of infectious virus was measured by plaque assay in the serum, liver, lung, and kidney. The dashed line indicates the limit of detection. (J) The serum levels of anti-LCMV total IgG across time in Armstrong- or Clone13-infected mice were measured by ELISA. (A–I) Data represent 6–9 mice from 3 experiments. (J) Data are from 1 experiment, representative of 3, with 3 mice/group. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Early NK cell depletion led to fewer TFH cells during late stages of chronic infection (day 29), and this corresponded to reductions in the B cell response at that time. We saw lower LCMV-specific total IgG, IgG1, and IgG2c in mice depleted of NK cells (Fig. 4G). Furthermore, the numbers of GC and plasmablast B cells at day 29 pi were reduced in mice that had been depleted of NK cells early on (Fig. 4H). These data indicate that the long-term effects of NK cell depletion on chronic-stage TFH differentiation parallel a reduction in the B cell response.

NK cell depletion expedites clearance of chronic LCMV infection [22–24]. Consistent with those findings, we observed a 45- to 500-fold reduction in virus titers at day 29 pi in the NK cell-depleted mice compared with the control-treated mice (Fig. 4I). Thus, the late T cell and antibody responses toward Clone13 in mice treated with NK1.1 resemble the responses found after acute infection (Fig. 3). We considered that this finding may be a result of the expedited control of the infection and minimal CD8+ T cell exhaustion in the NK-depleted mice [22]. Therefore, we compared antiviral IgG responses following acute infection with those of mice given Clone13 and depleted of NK cells. As expected, the serum antibody level in Armstrong-infected mice closely matched NK-depleted mice infected with Clone13, whereas NK intact mice infected with Clone13 had higher levels of antibody (Fig. 4J). These data suggest that NK cell depletion so effectively reduces virus loads that B cells are not further stimulated by antigen to become antibody-secreting cells.

Immune control of disseminated virus infection requires B cells, CD4+ T cells, and CD8+ T cells

NK cell depletion promotes quicker viral clearance, and as described above, these changes in virus titer can significantly impact the subsequent T and B cell responses. At day 8 of Clone13 infection, NK cell depletion results in greater CD4+ T cell, CD8+ T cell, and B cell responses (Figs. 1 and 2 and ref. [22]); thus, we sought to understand the primary cell type needed to resolve the infection. It is well documented that CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells are required to control infection [15, 49]; however, there is a body of evidence that implicates B cells in immune control. BCKO mice fail to eliminate chronic infection [27–29, 33, 48], and B cell-sufficient mice that cannot make virus-specific antibody also fail to control chronic strains of LCMV [32–34].

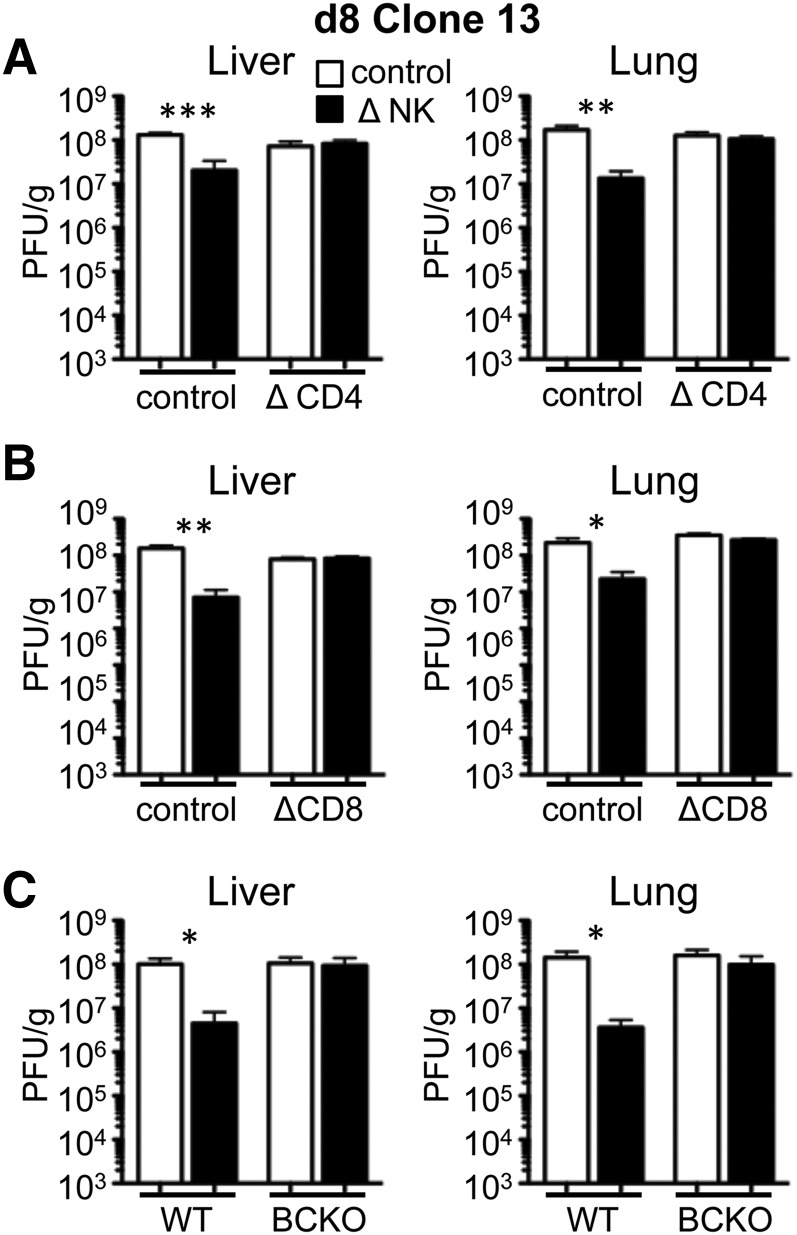

At day 8 in WT mice, NK1.1 treatment led to decreased levels of infectious virus in the liver and lung, as seen before (Fig. 5 and ref. [22]). We first assessed virus clearance following antibody-mediated (GK1.5) depletion of CD4+ T cells. The removal of NK cells in CD4-depleted mice had no effect on virus titer in the liver or lung at day 8 (Fig. 5A). These data are consistent with previous results showing no beneficial effect of NK depletion on CD8+ T cells or virus titer in the absence of CD4+ T cells [23]. We also found that NK cell depletion did not improve virus control in mice depleted of CD8+ T cells (Fig. 5B). NK cell depletion also failed to improve virus control in BCKO mice (µMT−/−; Fig. 5C). In total, these data suggest that NK cells control the magnitude of the T cell response, but virus clearance depends on the presence of CD4+ T, CD8+ T, and B cells, which act cooperatively to sustain antiviral defenses.

Figure 5. NK cell depletion expedites virus clearance but requires CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and B cells.

2(A) WT B6 mice were treated with PK136 (Δ NK) or control antibody at days −2 and −3 before infection with Clone13. The mice were additionally treated with GK1.5 (Δ CD4) or control antibody at day −1 before infection and day 2 pi. The level of infectious virus was measured by plaque assay in liver (left) and lung (right) tissues on day 8 pi. (B) WT B6 mice were treated with PK136 (Δ NK) or control antibody at days −2 and −3 before infection with Clone13. The mice were additionally treated with 2.43 (ΔCD8) or control antibody at day −1 before infection and day 3 pi. The level of infectious virus was measured by plaque assay in liver (left) and lung (right) tissues on day 8 pi. (C) WT B6 or μMT (BCKO) mice were treated with PK136 (Δ NK) or control antibody at days −2 and −3 before infection with Clone13. The level of infectious virus was measured by plaque assay in liver (left) and lung (right) tissues on day 7.5 pi. Data for each panel represent 5–6 mice from 2 experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

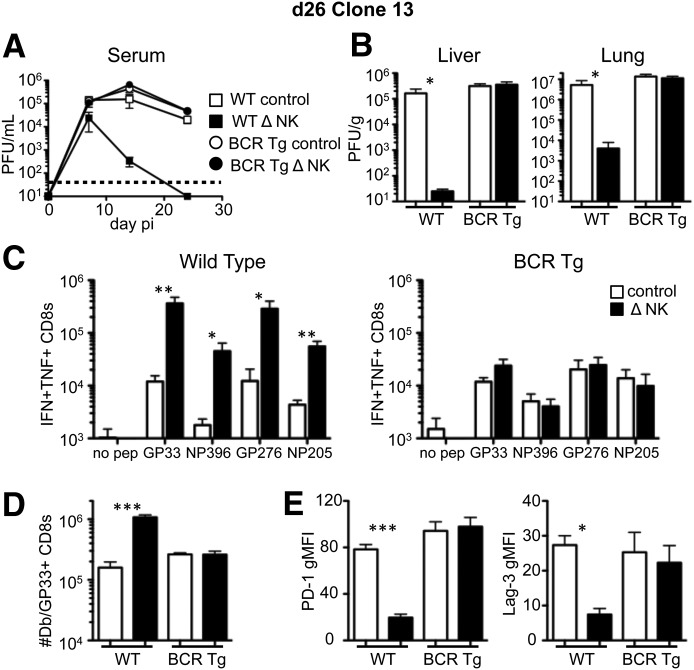

Mice that are congenitally deficient in B cells have multiple defects in lymphoid architecture, which contribute to poor IFN responses [27, 39] and weak T cell responses to LCMV [27, 28]. Thus, it may be that the beneficial effects of NK cell depletion on viral clearance require B cells or that T cell responses are inept in the BCKO environment and cannot be rescued by NK cell depletion. Therefore, we evaluated whether virus-specific antibody production is required for expedited viral clearance following NK cell depletion. BCR-transgenic (VH12/Vκ4) mice [40] have B cells that are specific for phosphatidyl choline and have normal lymphoid architecture but are unable to mount LCMV-specific antibody responses (data not shown). The VH12/Vκ4 mice were depleted of NK cells or not and then given Clone13; their viral titer was quantified in the blood over time and in the liver and lung at day 26. Whereas nontransgenic mice showed a reduction in viral load when NK cells were depleted, the NK cell-depleted VH12/Vκ4 mice did not have reduced viral burden in the serum over time or within various tissues at day 26 compared with NK cell-replete VH12/Vκ4 mice (Fig. 6A and B). Consistent with our earlier findings [22], NK cell depletion in nontransgenic mice increased the number of IFN-γ+TNF+ cytokine-producing CD8+ T cells (Fig. 6C, left). However, NK cell depletion did not improve CD8+ T cell responses in the VH12/Vκ4 mice (Fig. 6C, right). In nontransgenic mice, NK cell depletion increased the number of LCMV-specific CD8+ T cells and reduced their expression of the exhaustion markers, PD-1 and LAG-3; however, this effect did not occur in the VH12/Vκ4 mice (Fig. 6D and E). Therefore, the beneficial effects of NK cell depletion on CD8+ T cell responses and clearance of disseminated infection depend on B cells and their production of antiviral antibodies.

Figure 6. B cell antibody production is required for NK cell depletion-mediated virus clearance and prevention of CD8+ T cell exhaustion.

WT B6 or VH12/Vκ4 [BCR transgenic (BCR Tg)] mice were treated with PK136 (Δ NK) or control antibody at days −2 and −3 before infection with Clone13. The level of infectious virus was measured by plaque assay over time in the serum (A) and in the liver (left) and lung (right) tissues (B) on day 26 pi. (C) The total number of splenic CD8+ T cells producing IFN-γ and TNF-α in response to the indicated LCMV peptides was measured by intracellular cytokine staining in WT (left) and BCR-transgenic (right) mice at day 26 pi. (D) The total number of Db/GP33–41 tetramer+ CD8 T cells within the spleen at day 26 pi. (E) The geometric mean fluorescence intensity of PD-1 (left) and LAG-3 (right) on gated Db/GP33–41 tetramer+ CD8 T cells at day 26 pi. Data represent 5 mice from 2 experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

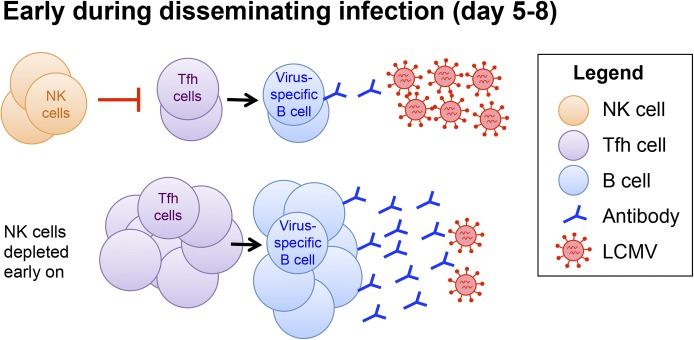

NK cells play a protective role in antiviral immunity for many infections. However, NK cells limit T cell responses during chronic LCMV infection, perhaps to reduce the immunopathological consequences of antiviral T cell responses to a disseminated infection. Herein, we examined the effects of NK cells on B cells and a subset of CD4+ T cells that stimulates B cell differentiation into memory cells and IgG-producing plasma cells. We found that antibody responses continue to rise during chronic infection compared with acute infection, and this was associated with a greater virus-specific TFH response. NK cell depletion further increased the TFH cell response early on, and there were corresponding increases in virus-specific antibody, GC-phenotype B cells, and plasmablasts that depended on CD4+ T cells (Fig. 7). The effects of NK cell depletion on virus clearance and prevention of CD8+ T cell exhaustion required B cell and antibody production. Thus, in the context of a disseminated virus infection, NK cells restrict humoral immune responses and lead to CD8+ T cell exhaustion and virus persistence.

Figure 7. NK cells act early to limit humoral immune responses to disseminated infection.

The data in Figs. 1, 2, and 5 are consistent with a model in which NK cells suppress incipient virus-specific CD4+ T cell responses, including the TFH subset that is specialized for delivering help to B cells. (Upper) In the presence of NK cells, the TFH response is reduced, which leads to lower virus-specific B cell responses and sustained viral burden. (Lower) When NK cells are depleted, TFH cells expand to a greater extent and promote the B cell response. The increased antiviral antibody levels following NK cell depletion reduce the viral load, permitting expedited clearance.

The results of this and other studies indicate that NK cell depletion can enhance CD4+ T, CD8+ T, and B cell responses and subsequently increase the clearance of persistent LCMV infection. Previous results have indicated that each of the 3 cell types is required for virus elimination [15, 30, 34, 48, 49]. Here, we show that the improved immune control caused by NK cell depletion is thwarted by the removal of any 1 subset (CD4, CD8, or B; Fig. 5). We speculate that CD4+ T, CD8+ T, and B cells have nonredundant roles in virus clearance. For example, CD8+ T cells are important for lysis of infected cells; B cell antibody production reduces the overall viral burden through virus opsonization, neutralization, and an unidentified mechanism(s) [27, 28, 32, 33]; and CD4+ T cells critically support both CD8+ T and B cell responses.

There is evidence in noninfectious model systems that NK cells regulate B cell responses. In some studies, NK cells inhibit B cells. For example, cloned mouse NK cells can recognize and kill B cells [50], and in vivo induction of NK cells with poly(I:C) reduces antibody responses to pneumococcal vaccine and sRBCs [51]. NK cells can kill B cells directly [52], and there is evidence that NK cells can inhibit B cells indirectly by killing essential dendritic cell populations that sustain B cell responses [51, 53]. However, other data show that activated NK cells enhance B cell responses [54–57], in part, by direct cell–cell contact or by releasing IFN-γ to stimulate B cell proliferation, Ig class-switching, and antigen presentation to CD4+ T cells. Additionally, NK cell depletion reduces antibody responses to Brucella abortus infection in mice [57]. Cumulatively, studies in nonviral models indicate that NK cells can positively or negatively influence B cell responses. Our data now show that NK cells significantly inhibit early antiviral antibody responses during chronic infection (Fig. 2).

As seen when comparing the Armstrong and Clone13 strains of LCMV (Fig. 3), long-term antibody production is greatly affected by viral persistence. To wit, the NK-depleted mice showed 4-fold decreased levels of virus-specific IgG in the serum at day 29 compared with infected NK cell-replete mice (Fig. 4). The decreased antibody production following NK1.1 treatment was most apparent on the IgG1 subtype, but the total numbers of TFH cells, GCs, and plasmablast B cells were also decreased at this later time (Fig. 4). Thus, NK cell depletion has opposite effects on B cell responses, depending on when the B cell response is measured. The difference in outcome is most likely a result of differences in viral load between the groups. At early times, B cells are stimulated by high viral loads in both groups of mice, and NK cell depletion improves the antibody response. At late times, the infection is largely controlled in the NK cell-depleted mice, and B cells no longer receive signaling by antigen, whereas the NK cell-replete mice continue to have elevated viral loads that further stimulate B cells. Thus, NK cell depletion abbreviates chronic infection, thereby preventing the long-term induction of virus-specific antibody.

One caveat for our experimental approach is that the PK136 antibody also depletes NKT cells, so some of the effects that we have attributed to NK cells could be partially a result of the loss of NKT cells. However, evidence from other laboratories suggests that NKT cells unlikely play a major role in inhibiting T and B cell responses. First, Cd1d knockout mice that lack NKT cells [58] show improved T cell responses to Clone13 when given the PK136 antibody [59]. Furthermore, Nfil3-deficient mice, which have reduced frequencies of conventional NK cells but normal NKT cell populations [60], more quickly eliminate Clone13 compared with WT mice [24]. Whereas we have not ruled out minor suppressive effects mediated by NKT cells, the findings from other laboratories that use different approaches suggest that the ablation of NK cells, as opposed to NKT cells, regulates T cell activity during chronic LCMV infection.

There are a number of potential mechanisms by which NK cells limit B cell responses. It could be that NK cell regulation of CD4+ T cells indirectly inhibits humoral immunity. TFH cells are crucial in the development of GCs and antibody isotype switching [21]. Situations in which TFH cells are reduced, i.e., ICOS deficiency or following IL-2 administration, result in significant reductions in humoral immunity [61–63]. Therefore, NK cell-mediated restriction of the TFH cell subset is a plausible explanation for defects in B cell responses. An additional possibility is that NK cell cytotoxicity or inhibitory cytokine production directly targets B cell activation. We feel that this is unlikely, as there is no effect of NK cell depletion in the absence of CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2D and E). In particular, NK cells do not reduce IgM production in the absence of CD4 help, despite the fact that IgM is less dependent on CD4 cells than GC formation and IgG production. Nevertheless, it could be that NK cells directly inhibit a subset of B cells that have received CD4+ T cell help.

It is well recognized that CD4+ T cells “help” B cell responses. However, new evidence suggests that B cells can help T cells [64, 65]. BCKO mice have reduced CD4+ T cell memory responses following acute LCMV infection and have deficiencies in immunity to chronic infection [27, 28]. Our results provide additional evidence that B cells contribute to CD8+ T cell responses, as the effects of NK cell depletion in reducing T cell exhaustion were dependent on B cell production of LCMV-specific antibodies (Fig. 6), consistent with earlier reports showing that a virus-specific antibody contributes to long-term control of chronic LCMV infection [33–35, 48]. One possible explanation for this is that antiviral antibodies act early to lower the virus titer directly to prevent T cell exhaustion. Another possibility is that NK cell depletion only improves CD4+ T cells that have been stimulated by dendritic cells presenting material derived from antigen-antibody complexes.

A set of papers recently identified an inhibitory role for type I IFN in limiting antiviral T cell responses during the chronic stage of LCMV infection [9, 10]. In those experiments, an antibody-mediated blockade of type-I IFNR led to improved clearance of Clone13 infection. Interestingly, type I IFN activates NK cells during LCMV infection [66]. Furthermore, therapeutic depletion of NK cells during the chronic stage can also promote virus clearance in a manner that depends on CD4+ T cells [67]. In view of our findings here, it could be that type I IFN exacerbates virus persistence by activating the immune-suppressive functions of NK cells, leading to reduced TFH cell numbers and subsequent B cell responses.

How is it advantageous to the host for NK cells to restrict humoral immune responses? It is possible that the benefit is a consequence of NK cell-mediated protection from T cell-dependent immune pathology. NK cells regulate CD4+ and CD8+ T cells during chronic LCMV infection in ways that critically impact virus persistence and immunopathology [23]. Therefore, the effect of NK cell depletion on humoral immunity, which is dependent on CD4+ T cells, may be secondary to the benefit of restricting T cell pathology. There may be other benefits of NK cell regulation of B cell responses outside of antiviral immunity, such as in the regulation of antibody production during autoimmune responses, which is also affected by TFH cells [68]. For example, Schuster et al. [45] showed that NK cell activity during chronic MCMV infection controls CD4+ T cell responses and prevents autoantibody production. Consistent with this hypothesis, the presence of regulatory NK cells that modulate T and B cell-dependent autoimmune diseases has been described recently [69, 70].

There is a great effort to understand how to increase TFH cells and broadly neutralizing antibody before or during HIV infection [71, 72]. Our data implicate NK cell modulation as a potential approach to improve concurrently virus-specific CD4+ TFH, CD8+ T, and B cell responses. The increased B cell response as a result of NK cell depletion is crucial for virus clearance and likely is involved in preventing CD8+ T cell exhaustion. NK cell receptor polymorphisms (i.e., KIR2DL3, KIR2DL2) play a role in virus resolution and immune pressure during HCV and HIV infections in humans, so it would be interesting to determine if these NK polymorphisms influence humoral immunity during chronic virus infections. As a result of the interplay among B, CD4+, and CD8+ T cells, our results suggest that optimal vaccine-induced immune responses against chronic virus infections in people should engage components of humoral and cellular immunity.

AUTHORSHIP

K.D.C. planned and performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. H.C.K performed experiments and analyzed data. J.K.W. supervised the project, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, by U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants R01AI074862 and R56AI110682 (to J.K.W.) and NIH Grant T32AI7273-27 (to K.D.C.). Additional support included start-up funds from UNC-Chapel Hill. The authors thank Steve Clarke (UNC-Chapel Hill) for kindly providing the VH12/Vκ4 mice.

Glossary

- BCKO

B cell deficient

- BHK

baby hamster kidney

- CD62L

cluster of differentiation 62 ligand

- Db

H-2Db

- GC

germinal center

- GP

glycoprotein

- HBV/HCV

hepatitis B/C virus

- I-Ab

H-2-IAb

- KIR

killer cell Ig-like receptor

- LAG-3

lymphocyte activation gene 3

- LCMV

lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus

- PD-1

programmed cell death protein 1

- pi

postinfection

- SLAMF6

signaling lymphocytic activation molecule family member 6

- TFH

T follicular helper

- UNC-Chapel Hill

University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

SEE CORRESPONDING EDITORIAL ON PAGE 139

The online version of this paper, found at www.jleukbio.org, includes supplemental information.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Virgin H. W., Wherry E. J., Ahmed R. (2009) Redefining chronic viral infection. Cell 138, 30–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yi J. S., Cox M. A., Zajac A. J. (2010) T-Cell exhaustion: characteristics, causes and conversion. Immunology 129, 474–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wherry E. J. (2011) T Cell exhaustion. Nat. Immunol. 12, 492–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richter K., Brocker T., Oxenius A. (2012) Antigen amount dictates CD8+ T-cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection irrespective of the type of antigen presenting cell. Eur. J. Immunol. 42, 2290–2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuller M. J., Zajac A. J. (2003) Ablation of CD8 and CD4 T cell responses by high viral loads. J. Immunol. 170, 477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wherry E. J., Blattman J. N., Ahmed R. (2005) Low CD8 T-cell proliferative potential and high viral load limit the effectiveness of therapeutic vaccination. J. Virol. 79, 8960–8968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Most R. G., Murali-Krishna K., Lanier J. G., Wherry E. J., Puglielli M. T., Blattman J. N., Sette A., Ahmed R. (2003) Changing immunodominance patterns in antiviral CD8 T-cell responses after loss of epitope presentation or chronic antigenic stimulation. Virology 315, 93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y., Swiecki M., Cella M., Alber G., Schreiber R. D., Gilfillan S., Colonna M. (2012) Timing and magnitude of type I interferon responses by distinct sensors impact CD8 T cell exhaustion and chronic viral infection. Cell Host Microbe 11, 631–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson E. B., Yamada D. H., Elsaesser H., Herskovitz J., Deng J., Cheng G., Aronow B. J., Karp C. L., Brooks D. G. (2013) Blockade of chronic type I interferon signaling to control persistent LCMV infection. Science 340, 202–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teijaro J. R., Ng C., Lee A. M., Sullivan B. M., Sheehan K. C., Welch M., Schreiber R. D., de la Torre J. C., Oldstone M. B. (2013) Persistent LCMV infection is controlled by blockade of type I interferon signaling. Science 340, 207–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brooks D. G., Trifilo M. J., Edelmann K. H., Teyton L., McGavern D. B., Oldstone M. B. (2006) Interleukin-10 determines viral clearance or persistence in vivo. Nat. Med. 12, 1301–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ejrnaes M., Filippi C. M., Martinic M. M., Ling E. M., Togher L. M., Crotty S., von Herrath M. G. (2006) Resolution of a chronic viral infection after interleukin-10 receptor blockade. J. Exp. Med. 203, 2461–2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blackburn S. D., Shin H., Haining W. N., Zou T., Workman C. J., Polley A., Betts M. R., Freeman G. J., Vignali D. A., Wherry E. J. (2009) Coregulation of CD8+ T cell exhaustion by multiple inhibitory receptors during chronic viral infection. Nat. Immunol. 10, 29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wherry E. J., Ha S. J., Kaech S. M., Haining W. N., Sarkar S., Kalia V., Subramaniam S., Blattman J. N., Barber D. L., Ahmed R. (2007) Molecular signature of CD8+ T cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Immunity 27, 670–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matloubian M., Concepcion R. J., Ahmed R. (1994) CD4+ T cells are required to sustain CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell responses during chronic viral infection. J. Virol. 68, 8056–8063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Battegay M., Moskophidis D., Rahemtulla A., Hengartner H., Mak T. W., Zinkernagel R. M. (1994) Enhanced establishment of a virus carrier state in adult CD4+ T-cell-deficient mice. J. Virol. 68, 4700–4704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yi J. S., Du M., Zajac A. J. (2009) A vital role for interleukin-21 in the control of a chronic viral infection. Science 324, 1572–1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fröhlich A., Kisielow J., Schmitz I., Freigang S., Shamshiev A. T., Weber J., Marsland B. J., Oxenius A., Kopf M. (2009) IL-21R on T cells is critical for sustained functionality and control of chronic viral infection. Science 324, 1576–1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elsaesser H., Sauer K., Brooks D. G. (2009) IL-21 is required to control chronic viral infection. Science 324, 1569–1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Locci M., Havenar-Daughton C., Landais E., Wu J., Kroenke M. A., Arlehamn C. L., Su L. F., Cubas R., Davis M. M., Sette A., Haddad E. K., Poignard P., Crotty S.; International AIDS Vaccine Initiative Protocol C Principal Investigators (2013) Human circulating PD-1+CXCR3−CXCR5+ memory Tfh cells are highly functional and correlate with broadly neutralizing HIV antibody responses. Immunity 39, 758–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crotty S. (2011) Follicular helper CD4 T cells (TFH). Annu. Rev. Immunol. 29, 621–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook K. D., Whitmire J. K. (2013) The depletion of NK cells prevents T cell exhaustion to efficiently control disseminating virus infection. J. Immunol. 190, 641–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waggoner S. N., Cornberg M., Selin L. K., Welsh R. M. (2012) Natural killer cells act as rheostats modulating antiviral T cells. Nature 481, 394–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lang P. A., Lang K. S., Xu H. C., Grusdat M., Parish I. A., Recher M., Elford A. R., Dhanji S., Shaabani N., Tran C. W., Dissanayake D., Rahbar R., Ghazarian M., Brüstle A., Fine J., Chen P., Weaver C. T., Klose C., Diefenbach A., Häussinger D., Carlyle J. R., Kaech S. M., Mak T. W., Ohashi P. S. (2012) Natural killer cell activation enhances immune pathology and promotes chronic infection by limiting CD8+ T-cell immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 1210–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crouse J., Bedenikovic G., Wiesel M., Ibberson M., Xenarios I., Von Laer D., Kalinke U., Vivier E., Jonjic S., Oxenius A. (2014) Type I interferons protect T cells against NK cell attack mediated by the activating receptor NCR1. Immunity 40, 961–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu H. C., Grusdat M., Pandyra A. A., Polz R., Huang J., Sharma P., Deenen R., Köhrer K., Rahbar R., Diefenbach A., Gibbert K., Löhning M., Höcker L., Waibler Z., Häussinger D., Mak T. W., Ohashi P. S., Lang K. S., Lang P. A. (2014) Type I interferon protects antiviral CD8+ T cells from NK cell cytotoxicity. Immunity 40, 949–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Misumi I., Whitmire J. K. (2014) B Cell depletion curtails CD4+ T cell memory and reduces protection against disseminating virus infection. J. Immunol. 192, 1597–1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whitmire J. K., Asano M. S., Kaech S. M., Sarkar S., Hannum L. G., Shlomchik M. J., Ahmed R. (2009) Requirement of B cells for generating CD4+ T cell memory. J. Immunol. 182, 1868–1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Homann D., Tishon A., Berger D. P., Weigle W. O., von Herrath M. G., Oldstone M. B. (1998) Evidence for an underlying CD4 helper and CD8 T-cell defect in B-cell-deficient mice: failure to clear persistent virus infection after adoptive immunotherapy with virus-specific memory cells from muMT/muMT mice. J. Virol. 72, 9208–9216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomsen A. R., Johansen J., Marker O., Christensen J. P. (1996) Exhaustion of CTL memory and recrudescence of viremia in lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-infected MHC class II-deficient mice and B cell-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 157, 3074–3080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bründler M. A., Aichele P., Bachmann M., Kitamura D., Rajewsky K., Zinkernagel R. M. (1996) Immunity to viruses in B cell-deficient mice: influence of antibodies on virus persistence and on T cell memory. Eur. J. Immunol. 26, 2257–2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Straub T., Schweier O., Bruns M., Nimmerjahn F., Waisman A., Pircher H. (2013) Nucleoprotein-specific nonneutralizing antibodies speed up LCMV elimination independently of complement and FcγR. Eur. J. Immunol. 43, 2338–2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richter K., Oxenius A. (2013) Non-neutralizing antibodies protect from chronic LCMV infection independently of activating FcγR or complement. Eur. J. Immunol. 43, 2349–2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bergthaler A., Flatz L., Verschoor A., Hegazy A. N., Holdener M., Fink K., Eschli B., Merkler D., Sommerstein R., Horvath E., Fernandez M., Fitsche A., Senn B. M., Verbeek J. S., Odermatt B., Siegrist C. A., Pinschewer D. D. (2009) Impaired antibody response causes persistence of prototypic T cell-contained virus. PLoS Biol. 7, e1000080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hangartner L., Zellweger R. M., Giobbi M., Weber J., Eschli B., McCoy K. D., Harris N., Recher M., Zinkernagel R. M., Hengartner H. (2006) Nonneutralizing antibodies binding to the surface glycoprotein of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus reduce early virus spread. J. Exp. Med. 203, 2033–2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zellweger R. M., Hangartner L., Weber J., Zinkernagel R. M., Hengartner H. (2006) Parameters governing exhaustion of rare T cell-independent neutralizing IgM-producing B cells after LCMV infection. Eur. J. Immunol. 36, 3175–3185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moir S., Ho J., Malaspina A., Wang W., DiPoto A. C., O’Shea M. A., Roby G., Kottilil S., Arthos J., Proschan M. A., Chun T. W., Fauci A. S. (2008) Evidence for HIV-associated B cell exhaustion in a dysfunctional memory B cell compartment in HIV-infected viremic individuals. J. Exp. Med. 205, 1797–1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kwong P. D., Mascola J. R. (2012) Human antibodies that neutralize HIV-1: identification, structures, and B cell ontogenies. Immunity 37, 412–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Louten J., van Rooijen N., Biron C. A. (2006) Type 1 IFN deficiency in the absence of normal splenic architecture during lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection. J. Immunol. 177, 3266–3272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clarke S. H., Arnold L. W. (1998) B-1 Cell development: evidence for an uncommitted immunoglobulin (Ig)M+ B cell precursor in B-1 cell differentiation. J. Exp. Med. 187, 1325–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahmed R., Salmi A., Butler L. D., Chiller J. M., Oldstone M. B. (1984) Selection of genetic variants of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus in spleens of persistently infected mice. Role in suppression of cytotoxic T lymphocyte response and viral persistence. J. Exp. Med. 160, 521–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whitmire J. K., Slifka M. K., Grewal I. S., Flavell R. A., Ahmed R. (1996) CD40 ligand-deficient mice generate a normal primary cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response but a defective humoral response to a viral infection. J. Virol. 70, 8375–8381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Whitmire J. K., Tan J. T., Whitton J. L. (2005) Interferon-gamma acts directly on CD8+ T cells to increase their abundance during virus infection. J. Exp. Med. 201, 1053–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Foster, B., Prussin, C., Liu, F., Whitmire, J. K., Whitton, J. L. (2007) Detection of intracellular cytokines by flow cytometry. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. Chapter 6, Unit 6.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schuster I. S., Wikstrom M. E., Brizard G., Coudert J. D., Estcourt M. J., Manzur M., O’Reilly L. A., Smyth M. J., Trapani J. A., Hill G. R., Andoniou C. E., Degli-Esposti M. A. (2014) TRAIL+ NK cells control CD4+ T cell responses during chronic viral infection to limit autoimmunity. Immunity 41, 646–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fahey L. M., Wilson E. B., Elsaesser H., Fistonich C. D., McGavern D. B., Brooks D. G. (2011) Viral persistence redirects CD4 T cell differentiation toward T follicular helper cells. J. Exp. Med. 208, 987–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harker J. A., Lewis G. M., Mack L., Zuniga E. I. (2011) Late interleukin-6 escalates T follicular helper cell responses and controls a chronic viral infection. Science 334, 825–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Planz O., Ehl S., Furrer E., Horvath E., Bründler M. A., Hengartner H., Zinkernagel R. M. (1997) A critical role for neutralizing-antibody-producing B cells, CD4(+) T cells, and interferons in persistent and acute infections of mice with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus: implications for adoptive immunotherapy of virus carriers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 6874–6879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zajac A. J., Blattman J. N., Murali-Krishna K., Sourdive D. J. D., Suresh M., Altman J. D., Ahmed R. (1998) Viral immune evasion due to persistence of activated T cells without effector function. J. Exp. Med. 188, 2205–2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nabel G., Allard W. J., Cantor H. (1982) A cloned cell line mediating natural killer cell function inhibits immunoglobulin secretion. J. Exp. Med. 156, 658–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abruzzo L. V., Rowley D. A. (1983) Homeostasis of the antibody response: immunoregulation by NK cells. Science 222, 581–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Storkus W. J., Dawson J. R. (1986) B cell sensitivity to natural killing: correlation with target cell stage of differentiation and state of activation. J. Immunol. 136, 1542–1547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shah P. D., Gilbertson S. M., Rowley D. A. (1985) Dendritic cells that have interacted with antigen are targets for natural killer cells. J. Exp. Med. 162, 625–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koh C. Y., Yuan D. (2000) The functional relevance of NK-cell-mediated upregulation of antigen-specific IgG2a responses. Cell. Immunol. 204, 135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gao N., Jennings P., Yuan D. (2008) Requirements for the natural killer cell-mediated induction of IgG1 and IgG2a expression in B lymphocytes. Int. Immunol. 20, 645–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gao N., Jennings P., Guo Y., Yuan D. (2011) Regulatory role of natural killer (NK) cells on antibody responses to Brucella abortus. Innate Immun. 17, 152–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jennings P., Yuan D. (2009) NK cell enhancement of antigen presentation by B lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 182, 2879–2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smiley S. T., Kaplan M. H., Grusby M. J. (1997) Immunoglobulin E production in the absence of interleukin-4-secreting CD1-dependent cells. Science 275, 977–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Welsh R. M., Waggoner S. N. (2013) NK cells controlling virus-specific T cells: rheostats for acute vs. persistent infections. Virology 435, 37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kamizono S., Duncan G. S., Seidel M. G., Morimoto A., Hamada K., Grosveld G., Akashi K., Lind E. F., Haight J. P., Ohashi P. S., Look A. T., Mak T. W. (2009) Nfil3/E4bp4 is required for the development and maturation of NK cells in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 206, 2977–2986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Akiba H., Takeda K., Kojima Y., Usui Y., Harada N., Yamazaki T., Ma J., Tezuka K., Yagita H., Okumura K. (2005) The role of ICOS in the CXCR5+ follicular B helper T cell maintenance in vivo. J. Immunol. 175, 2340–2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bossaller L., Burger J., Draeger R., Grimbacher B., Knoth R., Plebani A., Durandy A., Baumann U., Schlesier M., Welcher A. A., Peter H. H., Warnatz K. (2006) ICOS deficiency is associated with a severe reduction of CXCR5+CD4 germinal center Th cells. J. Immunol. 177, 4927–4932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ballesteros-Tato A., León B., Graf B. A., Moquin A., Adams P. S., Lund F. E., Randall T. D. (2012) Interleukin-2 inhibits germinal center formation by limiting T follicular helper cell differentiation. Immunity 36, 847–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.León B., Ballesteros-Tato A., Misra R. S., Wojciechowski W., Lund F. E. (2012) Unraveling effector functions of B cells during infection: the hidden world beyond antibody production. Infect. Disord. Drug Targets 12, 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lund F. E. (2008) Cytokine-producing B lymphocytes-key regulators of immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 20, 332–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Biron C. A., Nguyen K. B., Pien G. C., Cousens L. P., Salazar-Mather T. P. (1999) Natural killer cells in antiviral defense: function and regulation by innate cytokines. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17, 189–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Waggoner S. N., Daniels K. A., Welsh R. M. (2014) Therapeutic depletion of natural killer cells controls persistent infection. J. Virol. 88, 1953–1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vinuesa C. G., Tangye S. G., Moser B., Mackay C. R. (2005) Follicular B helper T cells in antibody responses and autoimmunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5, 853–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tian Z., Gershwin M. E., Zhang C. (2012) Regulatory NK cells in autoimmune disease. J. Autoimmun. 39, 206–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fogel L. A., Yokoyama W. M., French A. R. (2013) Natural killer cells in human autoimmune disorders. Arthritis Res. Ther. 15, 216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Streeck H., D’Souza M. P., Littman D. R., Crotty S. (2013) Harnessing CD4⁺ T cell responses in HIV vaccine development. Nat. Med. 19, 143–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Burton D. R., Ahmed R., Barouch D. H., Butera S. T., Crotty S., Godzik A., Kaufmann D. E., McElrath M. J., Nussenzweig M. C., Pulendran B., Scanlan C. N., Schief W. R., Silvestri G., Streeck H., Walker B. D., Walker L. M., Ward A. B., Wilson I. A., Wyatt R. (2012) A blueprint for HIV vaccine discovery. Cell Host Microbe 12, 396–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]