Abstract

CD151, a master regulator of laminin-binding integrins (α6β4, α6β1, and α3β1), assembles these integrins into complexes called tetraspanin-enriched microdomains. CD151 protein expression is elevated in 31% of human breast cancers and is even more elevated in high-grade (40%) and estrogen receptor–negative (45%) subtypes. The latter includes triple-negative (estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER2 negative) basal-like tumors. CD151 ablation markedly reduced basal-like mammary cell migration, invasion, spreading, and signaling (through FAK, Rac1, and lck) while disrupting epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-α6 integrin collaboration. Underlying these defects, CD151 ablation redistributed α6β4 integrins subcellularly and severed molecular links between integrins and tetraspanin-enriched microdomains. In a prototypical basal-like mammary tumor line, CD151 ablation notably delayed tumor progression in ectopic and orthotopic xenograft models. These results (a) establish that CD151-α6 integrin complexes play a functional role in basal-like mammary tumor progression; (b) emphasize that α6 integrins function via CD151 linkage in the context of tetraspanin-enriched microdomains; and (c) point to potential relevance of CD151 as a high-priority therapeutic target, with relative selectivity (compared with laminin-binding integrins) for pathologic rather than normal physiology.

Introduction

CD151 (SFA-1, PETA-3), one of 33 proteins in the mammalian tetraspanin protein family (1), is widely expressed on the surface of many cell types, where it associates strongly with laminin-binding integrins (α3β1, α6β1, α6β4, and α7β1) and more weakly with a few additional integrins (2). Hence, CD151 is well positioned to modulate integrin-dependent cell spreading, migration, signaling, and adhesion strengthening (3–5). CD151 may function by linking laminin-binding integrins to other tetraspanins (e.g., CD9, CD81, CD82, and CD63), signaling molecules (phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase and protein kinase C), and other proteins within tetraspanin-enriched microdomains (1, 6).

CD151-associated integrins (α3β1, α6β1, and α6β4) play critical roles in kidney and skin development (7). CD151 itself may support kidney and skin development and other functions in humans (8). Mice lacking CD151 are viable and fertile, with no obvious developmental defects (9) or showing kidney defects (10), depending on genetic background. Under pathologic conditions, CD151-null mice showed in vivo defects in wound healing (11) and angiogenesis (12). Ex vivo analyses of CD151-null cells and tissues revealed selected alterations in cell outgrowth, migration, aggregation, proliferation, morphology, and signaling (9, 12, 13).

Whereas other tetraspanins suppress tumor cell invasion and metastasis (14), CD151 promotes tumor malignancy (15), and the CD151 gene is up-regulated in human keratinocytes during epithelial-mesenchymal transition (16). In addition, CD151 expression correlated with poor prognosis, enhanced metastasis, or increased motility in several cancer types (e.g., ref. 17). Removal of CD151 by antisense, siRNA knockdown, or knockout may affect the phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase (PI3K), Akt, and Rac1 pathways (12, 18). In addition, CD151 depletion may either increase (12, 19) or decrease (12, 20) cell motility, whereas effects on cell adhesion vary from minimal to substantial (12, 13, 20, 21), perhaps due to effects on integrin activation (21) and/or internalization (20). Thus, CD151 has diverse and unpredictable functions in different cellular environments.

At present, little has been done about CD151 in breast cancer. The α6β4 integrin (after disconnection from hemidesmosome intermediate filaments) promotes mammary tumor cell motility and invasion by activating the PI3K/Akt pathway or small GTPase Rac1/nuclear factor κB (22, 23). α6β4 may also promote mammary tumorigenesis by amplifying signaling of ErbB family members (24). In human breast cancers, expression of integrin α6 and/or β4 is associated with the estrogen receptor–negative basal-like subtype, high tumor grade, and increased mortality (25–27). Given the CD151 association with laminin-binding integrins, we hypothesized that CD151 influences mammary tumor progression. Indeed, we found elevated CD151 in high-grade and estrogen receptor– negative tumors, including the “triple-negative” (estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER2 negative) basal-type human breast cancers. CD151 ablation yielded marked alterations in integrin-mediated cell invasion, migration, and/or spreading in mammary cell lines (MCF-10A and MDA-MB-231) with basal-like gene expression patterns (28). We also gained new insights into CD151 effects on integrin signaling, distribution, and collaboration with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Supporting the relevance of these findings, CD151 ablation delayed human mammary tumor progression in mouse xenograft models.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and reagents

The majority of studies were carried out using immortalized MCF-10A and malignant MDA-MB-231 cells. The former are well suited for analysis of CD151 effects on migration of confluent cell monolayers and integrin organization in cell monolayers. The latter are better suited for studies of cell invasion, epidermal growth factor (EGF)–stimulated responses, signaling, and tumor progression. Both cell types are useful for studies of CD151 contributions to integrin molecular complexes. A few other cell mammary cell lines are also included to illustrate the generality of the findings. Human basal-like mammary epithelial cell lines (MCF-10A, MDA-MB-231, BT549, and Hst578; ref. 28) and J110 (estrogen receptor–positive metastatic mouse mammary line; ref. 29) were cultured in DMEM or RPMI 1640 with 10% FCS (Life Technologies, Inc.), 10 mmol/L HEPES, and antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin). A Hoechst dye effluxing mammary cell subline (s-MCF-7) was selected for high sensitivity to EGF. In vivo passaged p-MDA-MB-231 cells were from nude mouse tumors and were treated with control siRNA (clones C1 and C2) or CD151 siRNA (clones K1, K2, and K3).

Anti-CD151 monoclonal antibodies (mAb) include 5C11, 1A5 (15), and FITC-conjugated IIG5a (GeneTex, Inc.). Anti-CD9 mAb MM2/57 (unconjugated and FITC conjugated) was from Biosource. mAbs to tetraspanins CD81 (M38) and CD82 (M104); mAbs to integrin α2 (A2-IIE10), integrin α3 (A3-X8), integrin α6 (GöH3), integrin β1 (TS2/16), and integrin β4 (3E1, ASC-8); and rabbit polyclonal antibodies to the integrin α3A and α6A cytoplasmic domains were referenced elsewhere (5, 12). Anti-β1 mAb 9EG7 was from PharMingen. Antibodies to FAK, Y397-phosphorylated FAK, Fyn, Src, and p130Cas were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Antibodies to phosphorylated Src, Lck, and FAK (Y925) were from Cell Signaling Technology. PI3K inhibitor (Ly294002) was from Calbiochem and mitomycin C was from Sigma.

Human tissue array analyses

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor samples annotated with pathologic and prediagnosis clinical data were obtained under an Institutional Review Board (IRB)–approved protocol (Partners IRB #2000-P-001448) from Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Immunohistochemistry was done on four paraffin tissue microarrays of 124 primary human breast tumors containing two representative 0.6-mm cores of each tumor and representative cores of normal breast tissues. For CD151 immunohistochemistry, primary antibody (clone RLM30, Novacostra) was used at 1:50 dilution and detected using DAKO EnVision+ System (DAKO). Immunoreactivity was scored semiquantitatively by a breast pathologist (A.R.) using a scale of 0 to 3+, where 1+ staining approximates that in normal breast myoepithelial cells. Each single intensity score is based on two tissue cores, with 0 to 1+ indicating low, and 2 to 3+ indicating high/overexpressed.

siRNA and shRNA targeting

siRNAs were purchased from Dharmacon and used to target human CD151 (#4, GCAGGUCUUUGGCAUGA; #2, CCUCAAGAGUGACUACAUCUU), α6 integrin (CAAGACAGCUCAUAUUGAUUU), α3 integrin (UUACAGAGACUUUGACCGAUU), CD9 (CCAAGAAGGACGUACUCGAUU), CD81 (CCACCAACCUCCUGUAUCUUU), and CD82 (a pool of four siRNAs). Cells were seeded (1.0 × 105/mL, 12–20 h) before siRNA transfection using Lipofectamine 2000. To enhance knockdown, cells were typically transfected again 2 d later.

For stable knockdown of human CD151, oligo AGTACCTGCTGTTTACCTACA (20) was cloned into lentivirus expression vector plenti-U6BX (Cellogenetics, Inc.) and verified by DNA sequencing. Viral titers were determined by HEK 293T cell infection. Infected cells were sorted by flow cytometry (with mAb 5C11) for CD151 absence.

Matrigel invasion, migration, and spreading assays

To assess invasion, cells were detached using nonenzymatic EDTA-containing dissociation buffer (Life Technologies). Then, cells (3 × 104–5.0 × 104) in serum-free DMEM with 0.02% bovine serum albumin (BSA) were added to transwell chambers containing 8-μm membranes precoated with Matrigel (BD Biocoat). Chamber bottoms contained serum-free medium ± 10 ng/mL EGF. After invasion through Matrigel (12–18 h, 37°C), membranes were washed, dried, fixed, and stained (Giemsa, Sigma), and then cells were counted.

For monolayer scratch assays, 20% to 30% confluent cells in 24-well plates were transfected with siRNA for 5 d. Confluent cells were starved for ~12 h and gaps were scratched by pipette tip. After removing loose cells, DMEM/F12 was added, which contained MCF-10A–specific supplement at 1% dilution, ± 10 ng/mL EGF. Cell images were acquired with a monochrome charge-coupled device camera (RT SPOT, Diagnostic Instruments) on an Axiovert 135 inverted microscope (Zeiss Co.) and were controlled by IP Lab software (Scanalytics) running on a G4 Macintosh computer. Cell gaps were quantitated using Scion Image vs.62 (Scion Corp.). For spreading assays, cells (suspended at 37°C, 45 min) were plated onto 48-well plates precoated with extracellulae matrix substrates and photographed after 45 min, as indicated above. Cells defined as spread showed a flattened morphology that was not phase bright by light microscopy.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

For confocal analyses, cells cultured on coverslips were treated with siRNAs (5–6 d), stained with various primary antibodies, then incubated with secondary antibody (FITC- or Alexa 594–conjugated goat anti-mouse or anti-rat) alone or combined (Molecular Probes). Cells were visualized under a Zeiss LSM 510 laser-scanning confocal microscope. Using LSM510 Meta software, z-axis images were acquired at 0.5- to 1-μm increments.

Immunoprecipitation, [3H]-palmitate labeling, and signaling assays

For metabolic labeling, siRNA-treated cells (80–90% confluent) were washed in PBS, serum starved (3–4 h), pulsed for 1 to 2 h in medium containing 0.2 to 0.3 mCi/mL [3H]-palmitic acid plus 5% dialyzed fetal bovine serum, and then lysed in 1% Brij-96 for 5 h at 4°C. Immunoprecipitation and detection of [3H]-palmitate–labeled proteins was as described (12, 30, 31). To assess protein phosphorylation, cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (1% Triton X-100, 1% deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS), and then phosphorylated proteins were either immunoprecipitated and blotted with anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (4G10, UBI) or directly blotted in cell lysates using phospho-specific antibodies. Rac1 activation was assessed with a glutathione S-transferase (GST)-PBD pull-down assay kit (UBI).

Nude mouse xenograft assays

For ectopic analysis, five nude mice were each injected s.c. at two sites with MDA-MB-231 cells (1 × 106 per site). For orthotopic analysis, MDA-MB-231 cells were injected into mammary fat pads of 10 nude mice (two sites each, 7.5 × 105 cells per site). Tumor sizes were measured with calipers and volumes were calculated (L × W × H × 0.52). Animals were maintained until tumors reached a width of 2 cm or mice became moribund. Apoptotic index was determined by terminal deoxyribonucleotidyl transferase–mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining, using the DeadEnd Fluorometric TUNEL System (Promega Co.), on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor sections.

Results

CD151 in normal and malignant human mammary epithelial cells

Samples of normal and malignant human breast tissues were analyzed for CD151 protein expression (Fig. 1A). In normal breast tissue, CD151 was in the basal-myoepithelial cell layer surrounding both ducts and lobular alveolae (Fig. 1A-a, b). Staining was predominantly cytoplasmic with regions of basal or basolateral membrane accentuation. By comparison, a range of CD151 patterns were seen in human breast tumor tissue microarray samples. Some tumors showed absent (score 0, Fig. 1A-c) or only modest CD151 protein (score 1+, Fig. 1A-d). Others showed moderate to high CD151 (score 2+, Fig. 1A-e, f; score 3+, Fig. 1A-g, h). CD151 localization varied from predominantly membranous (Fig. 1A-e, g) to mostly cytoplasmic (Fig. 1A-f, h). CD151 was overexpressed in 31% of invasive breast tumors and significantly correlated with high tumor grade and estrogen receptor negativity (Fig. 1B; Supplementary Table S1). Estrogen receptor–negative/HER2-negative tumors showing the highest proportion of CD151 overexpression (45% in Supplementary Table S1) were also entirely progesterone receptor negative and contained a basal-like gene expression profile (data not shown). Estrogen receptor–negative/HER2-positive tumors also showed elevated CD151 expression (Supplementary Table S1, 40%). By contrast, luminal tumors (estrogen receptor positive and HER2 negative) had the lowest proportion of CD151 expression (45% versus 17%, respectively; P < 0.003). CD151 expression was not associated with patient age, tumor size, ductal or lobular histology, lymph node metastasis, the presence of peritumoral lymphovascular invasion, or HER2 overexpression in this cohort of patients. Long-term outcome and distant metastatic recurrence data are not yet available.

Figure 1.

CD151 protein expression in human breast carcinoma. A, immunohistochemistry for CD151 was done on paraffin sections of tissue microarrays containing samples of normal breast tissue (a and b) and invasive breast tumors (c–h). a, normal breast duct (×40). b, normal breast lobule (×100); arrows, representative CD151-positive cells in the basal/myoepithelial layer. c and d, human tumors with absent and low degree of CD151 immunostaining, respectively (×40). e and f, human tumors with moderate 2+ overexpression of CD151 predominantly located on the membrane or in cytoplasm, respectively (×40). g and h, human tumors with marked 3+ overexpression of CD151 on the membrane or in cytoplasm, respectively (×40). B, human breast cancer tissue microarray samples (a total of 124 patients) were subdivided according to modified Bloom-Richardson grade and estrogen receptor protein expression. The percent of each subgroup expressing high CD151 (3+ or 2+) is indicated. For further details, see Supplementary Table S1.

CD151 effects on mammary cell invasion and motility

For CD151 functional studies, we focused mostly on two distinct, but prototypical, myoepithelial-basal derived mammary cell lines: immortalized MCF-10A and malignant MDA-MB-231. Treatment with siRNA reduced CD151 protein levels by >90% in MCF-10A cells, as seen by blotting (Fig. 2A, right), metabolic labeling (Fig. 5B), or flow cytometry (data not shown). Mobilization of MCF-10A cells into a gap (scratched into a confluent cell monolayer) was reduced by nearly 50% for CD151 siRNA–treated cells compared with control cells (Fig. 2A). Similar results were obtained when CD151 was stably silenced (>95%) by stable shRNA expression in MCF-10A cells (data not shown). Knockdown of integrin α6, but not integrin α3, essentially eliminated motility (data not shown). Because α6 mostly associates with β4 in MCF-10A cells (data not shown), motility in Fig. 2A must depend on integrin α6β4. Neither proliferation nor survival of MCF-10A cells was affected by CD151 silencing (data not shown).

Figure 2.

CD151 supports mammary epithelial cell migration and invasion. A, after treatment with siRNAs, MCF-10A cells, grown to confluence, were then incubated in a 24-well plate with serum-free medium containing 10 μg/mL mitomycin C at room temperature for 1 h. After gaps were scratched into cell monolayers, 0.5 mL of serum-free medium containing 10 ng/mL EGF was added, and gaps were evaluated after 0 and 18 h at 37°C. Percentage of gap closure was determined by measuring the mean change in gap width at three representative sites in three independent experiments (n = 3) *, P < 0.05. Right, siRNA knockdown efficiency. MCF-10A cells in 24-well plates were treated with siRNAs [mock, control (Cntl), or CD151#4] for 5 d, and cell lysates (in RIPA buffer) were blotted for CD151 (mAb 1A5) and β-actin. B, after treatment with siRNAs, MDA-MB-231 cells (5 × 104) in serum-free medium containing 0.1% BSA were added to the top of Matrigel-coated transwell chambers. Serum-free medium (0.75 mL) containing 10 ng/mL EGF and 0.1% BSA was added to the bottom of transwell chambers. After ~18 h at 37°C, cells that had invaded through the Matrigel were fixed, stained, and photographed, and the mean number of invaded cells was determined from triplicate chambers. Bar, 100 μm. Right, siRNA efficiency. MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with siRNAs and then lysates were blotted for tetraspanins CD151 (mAb 1A5) and CD9 (mAb MM2/57). The two rows of numbers below the figure indicate percent knockdown values for CD151 and CD9, respectively, as determined by densitometry. C, after treatment with siRNAs (alone or in combination), MDA-MB-231 cells were again analyzed for invasion through Matrigel, as in B. D, a metastatic mouse mammary tumor cell line (J110) was treated with siRNA to murine CD151 (70% knockdown) or murine α6 integrin (>80% knockdown). Invasion was then analyzed as in B. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Figure 5.

CD151 affects the molecular organization of integrins. A, MCF-10A cells were initially seeded onto coverslips and treated with siRNAs for 5 d. Live MCF-10A cells were incubated with primary anti-integrin antibodies for 1 h at 4°C and then stained with Alexa Fluor 594–conjugated secondary antibody. After washing, cells were further stained with FITC-conjugated CD151 antibody. After staining, cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde (20 min, 4°C) and mounted on slides using Prolong antifade solution (Molecular Probes) and then ventral sections were visualized by confocal miscopy. Antibodies used were mAb GoH3 (integrin α6; a and d), mAb X8 (integrin α3; g and j), mAb IIE10 (integrin α2; m and n), and mAb 5C11 (CD151; c, f, i, and l). Right, merged green and red staining. Ventral sections of cells were visualized by confocal microscopy. a–c, g, h, and m, treated with control siRNA; d–f, j–l, and n, treated with CD151 siRNA. Bar, 50 μm. B, MCF-10A cells were treated with siRNAs, labeled with [3H]-palmitate, and then lysed in 1% Briji-96 buffer. Immunoprecipitations of α2, α3, and α6 integrins and CD151 were carried out with mAbs IIE10, X8, GoH3, and 5C11. Note that the integrin β1 subunit does not appear because it does not undergo palmitoylation. Bottom, immunoblots for α3, α6, and CD9, present in the immunoprecipitated complexes. The identity of CD81 (top) was confirmed by immunoblotting (data not shown). We assume that the band just below CD81 is claudin-1 because it is known to be palmitoylated and it associates closely with CD9 (50) and thus would be recruited via CD151 into a complex with α3 and α6 integrins.

CD151 was also silenced in MDA-MB-231 cells (>80–90%; Fig. 2B, right), resulting in 78% reduction of invasion through Matrigelcoated transwell chambers (Fig. 2B). Stable silencing of MDA-MB-231 CD151 (by shRNA) yielded similar results (data not shown). By contrast, silencing of tetraspanins CD82 and CD9 minimally reduced invasion (Fig. 2B). Although CD9 silencing slightly elevated MDA-MD-231 invasion (Fig. 2B and C), silencing of CD9 and CD151 together mimicked the CD151 effect (Fig. 2C), suggesting that CD151 silencing is dominant. We also silenced CD151 (by ~90%) in malignant mouse breast cancer J110 cells. Again, invasion through Matrigel was significantly reduced (Fig. 2D). Knockdown of α6 integrin protein (by 80–90%; data not shown) also caused a >50% reduction in invasion by J110 cells (Fig. 2D), and α6 integrin silencing caused a >47% decrease in invasion by MDA-MB-231 cells (data not shown). Hence, CD151 contributes considerably to α6 integrin–dependent motility and invasion in multiple mammary cell lines.

CD151 effects on integrin-dependent cell spreading and EGF stimulation

MDA-MB-231 cells spread on laminin-1 in an integrin-dependent manner (i.e., spreading was blocked by anti–integrin α6 antibody; data not shown). This spreading was increased (~31–63%) on stimulation with EGF, which can activate integrin functions (Fig. 3A and B). By contrast, cells lacking CD151 showed lower initial spreading (~8%) that was not stimulated by EGF (Fig. 3A and B). CD151 ablation did not affect cell spreading on fibronectin (Fig. 3C), and MDA-MB-231 cells did not spread on BSA-coated surfaces (data not shown). EGF stimulation also failed to rescue defective Matrigel invasion caused by CD151 ablation, as seen in p-MDA-MB-231 (Fig. 3C), s-MCF-7 (Fig. 3D), and BT549 (data not shown) cells. In these multiple mammary cell lines, invasion was stimulated by EGF when CD151 was present, but was not stimulated when CD151 was ablated. Two additional stimulators, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and insulin-like growth factor I (which also activate integrins via inside-out signaling), showed similar inability to overcome CD151 depletion effects on MDA-MB-231 cell invasion and spreading (data not shown).

Figure 3.

CD151 effects on EGF-stimulated mammary cell spreading and invasion. A, after siRNA treatment, MDA-MB-231 cells were suspended in serum-free medium at 37°C for 45 min, and then plated onto laminin-1–or fibronectin (Fn)-coated 24-well plates with or without EGF (10 ng/mL). After 45 min, representative fields were photographed. B, percentages of spread cells were determined (n = 4). Note: No cell spreading was observed on plastic surfaces coated with BSA (data not shown). C, invasion was also analyzed (as in Fig. 2B) with or without EGF (10 μg/mL) added to the bottom of the invasion chamber. After tumor formation in nude mice, MDA-MB-231 cells were reisolated (now called p-MDA-MB-231). These passaged sublines were isolated from tumors originating from MDA-MB-231 cells that had been treated with control shRNA (C1) or CD151 shRNA (K1 and K2; see also Fig. 6C). D, a subline of MCF-7 was enriched for Hoechst dye exclusion and elevated EGFR (now called s-MCF-7) and was analyzed for invasion as in C.

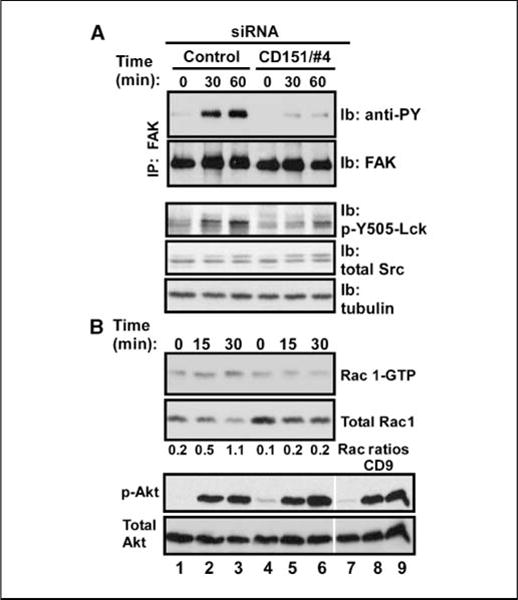

CD151 affects cell signaling

Treatment of MDA-MB-231 cells with 4-amino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-7-(t-butyl)-pyrazolo[3,4-d]-pyrimidine, a specific inhibitor of Src family kinases, completely abolished cell spreading on laminin-1 substrate (data not shown), suggesting a role for Src family kinase–mediated tyrosine phosphorylation. Within 30 to 60 minutes after plating on laminin-1, CD151-silenced MDA-MB-231 cells showed reduced tyrosine phosphorylation of FAK (Fig. 4A), a kinase crucial for tumor invasion (32). Surprisingly, CD151 ablation did not affect activation of src (which typically modulates FAK), as assessed by blotting with anti-pY416 (present in Src, Fyn, and Yes kinases), after cell plating on laminin-1 or fibronectin (data not shown). Phosphorylation of FAK-Y925, which is mediated by Src (33), was also unaffected (data not shown), although overall FAK tyrosine phosphorylation was diminished (Fig. 4A). However, CD151 ablation did diminish activation (at Y505) of lck, an Src family kinase member implicated in mammary tumor progression (ref. 34; Fig. 4A, bottom).

Figure 4.

Impact of CD151 ablation on integrin-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation cascade. A, after siRNA treatment, MDA-MB-231 cells were detached, washed, and suspended in serum-free DMEM containing 0.1% BSA. Cells were then kept in suspension for 45 min at 37°C to remove residual growth factor effects before being plated on laminin-1. At the indicated times, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer. After immunoprecipitation of FAK from MDA-MB-231 cells, we analyzed FAK tyrosine phosphorylation (mAb 4G10) and total FAK by immunoblotting. Total cell lysates were also probed for activated Lck (p-Y505-Lck), total Src, and tubulin. B, to assess activation of small GTPase Rac1, cell lysates (prepared as in A) were incubated with GST-PBD beads (45 min, 4°C) to recover activated Rac1 (Rac1-GTP form). Beads were washed and boiled, and released proteins were blotted with anti-Rac1 antibody (top). Total Rac1 protein in lysates was also blotted to serve as a control (bottom). Note that the observed increase in total Rac1 is due to unequal dilution of starting lysates; the actual amount of Rac1 is unchanged. Activated Akt (p-Akt) and total Akt were also blotted with antibodies to phospho-Akt (p-S473) and total Akt.

The Rac and Akt signaling pathways exert major influence on cell morphology, motility, and migration (35, 36). Consistent with this, CD151 ablation markedly reduced integrin-dependent Rac1 activation in MDA-MB-231 cells plated on Matrigel for 30 minutes (Fig. 4B). However, Akt activation was not notably altered in CD151-silenced cells plated on Matrigel (Fig. 4B), although CD151 and associated integrins modulate Akt activation in other cell types (see Discussion) and the PI3K/Akt pathway is critical for MDA-MB-231 cell invasion (37).

CD151 affects integrin subcellular distribution, but not expression levels

We assumed that the CD151 effects seen in Figs. 2–4 arise due to CD151 effects on laminin-binding integrins. However, silencing of CD151 did not affect either the surface expression or activation of α6β1, α3β1, or α6β4 on either MCF-10A or MDA-MB-231 cells (data not shown). Furthermore, amounts of α3 and α6 integrins were unchanged, as seen by biosynthetic labeling and immunoblotting (Fig. 5B). Hence, although CD151 can closely associate with laminin-binding integrins such as α3β1 and α6β4, it is not required for their expression or activation.

Next, we analyzed CD151 ablation effects on integrin distribution in MCF-10A cells. As seen in ventral sections, integrin α6 and CD151 are present in broad patches aligned near cell-cell boundaries (Fig. 5A, a–c). However, CD151 depletion markedly diminished this pattern of staining as bands of α6 became thinner and more proximal to cell-cell boundaries, whereas CD151 staining itself was greatly diminished (Fig. 5A, d–f). By contrast, CD151 depletion minimally affected integrin α3 staining (Fig. 5A, compare g–i with j–l) and did not affect integrin α2 staining (Fig. 5A-m, n). Hence, CD151 markedly affects the subcellular distribution of α6 integrins (which in this case is mostly α6β4).

CD151 affects integrin associations with other proteins

CD151 may link laminin-binding integrins to other proteins within the plasma membrane (38, 39). Hence, we tested whether CD151 depletion would disconnect α3 and α6 integrins from cell-surface partners. Metabolic labeling with [3H]-palmitate was carried out because tetraspanins and many of their partner proteins are typically palmitoylated, and this method of labeling has proved to be more informative than other types of labeling (12, 30, 31). From [3H]-palmitate–labeled MCF-10A lysate, recovery of α6β4 integrin was not diminished on ablation of CD151 [Fig. 5B, lanes 5–7; see β4 (top) and α6 immunoblot (third row)]. However, recovery was diminished for CD151 itself, tetraspanins CD9 and CD81, and at least five other proteins (white arrowheads, lane 6). Similarly, immunoprecipitation of α3 integrin was not diminished (Fig. 5B, second row, lanes 2–4), but levels of CD151 and nearly all other associated proteins were decreased (Fig. 5B,top, lane 3). Diminished recovery of CD9 as an integrin partner, due to CD151 ablation, was confirmed by CD9 immunoblotting (see Figs. 5B, bottom, lanes 2, 3 and 5, 6). In addition, immunoprecipitation of α6 integrin yielded a small amount of α3 (Fig. 5B, second row, lanes 5 and 7), which was lost when CD151 was ablated (lane 6), whereas α2 integrin yielded no prominent proteins, consistent with α2 not associating with tetraspanins (Fig. 5B, lane 1). As shown here for MCF-10A cells (Fig. 5B), α3 and α6 integrin complexes were similarly disrupted on CD151 ablation in MDA-MB-231 cells (data not shown). Together, these results strongly support a critical role for CD151 in linking α3 and α6 integrins to multiple components within tetraspanin-enriched microdomains.

CD151 accelerates MDA-MB-231 tumor progression in vivo

Soft agar assays were carried out using 5,000 and 10,000 MDA-MB-231 cells per 60-mm dish. No differences were observed in colony numbers, size of colonies, or rate of colony development between control and CD151-knockdown cells. Next, we tested whether CD151 affects tumor progression in vivo, using MDA-MB-231 nude mouse xenograft models. In a preliminary ectopic (s.c.) injection experiment, nude mice were injected with MDA-MB-231 cells expressing either control shRNA or CD151 shRNA. Tumors arising from control MDA-MB-231 cells appeared by 8 to 9 weeks, whereas CD151-ablated cells did not yield detectable tumors until 11 to 12 weeks (Fig. 6A). MDA-MB-231 cells were also injected into mammary fat pads, and primary tumor growth was analyzed (Fig. 6B). Again, tumor appearance and growth were markedly delayed (by 4–5 weeks) in mice injected with CD151-ablated cells. However, analysis of H&E-stained slides from several tumors revealed no obvious morphologic differences between tumors formed from CD151-positive and CD151-ablated MDA-MB-231 cells. In addition, from several representative tumors, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded slides were prepared, and TUNEL staining was carried out to detect apoptotic cells. Although there was a trend toward a higher apoptotic index in CD151-ablated tumors, results did not reach statistical significance (data not shown). In addition, cells were recovered from independent MDA-MB-231 tumors from both control mice (C1 and C2) and CD151-knockdown mice (K1, K2, and K3) and then cultured in vitro. Blotting of CD151 confirmed that control MDA-MB-231 cells indeed contained abundant CD151, whereas CD151-ablated cells expressed little or no CD151 (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

CD151 accelerates tumor formation in vivo. A, MDA-MB-231 cells expressing either control or CD151 shRNA were then injected s.c. into nude mice, and tumor formation was monitored. B, MDA-MB-231 cells expressing shRNA were injected into mammary fat pads of nude mice. Mice were terminated when they became moribund or when tumors reached 2 cm (in any dimension). Statistical significance was analyzed with the log-rank test. C, after tumor formation in nude mice, MDA-MB-231 cells were reisolated and cultured in vitro. From these sublines (C1 and C2 from control-shRNA expressing cells; K1, K2, and K3 from CD151-knockdown cells), cell lysates were prepared and blotted for CD151 (with mAb 1A5) and integrin α3 (with rabbit polyclonal antibody).

Discussion

A role for CD151 in breast cancer had not previously been shown. Here we show that CD151 overexpression occurs, at least to some extent, in all subtypes of human breast cancer, with expression most significantly elevated in patient tissue samples that were of high grade and/or of the estrogen receptor–negative type. Among estrogen receptor–negative samples, CD151 was elevated most frequently in triple-negative basal-like tumors. Here we focused mostly on the role of CD151 in basal-like cells. Its role in other types of mammary cells and tumors will be addressed elsewhere.

Not only is CD151 significantly up-regulated in basal-like human breast cancer samples but it also seems to play a functional role. CD151 depletion, via RNA interference, caused a marked delay in tumor formation by MDA-MB-231 cells, as seen in both ectopic and orthotopic xenograft models. Hence, CD151 seems to accelerate mammary tumor progression in this basal-type cell line. Elevated CD151 expression was previously linked to poor prognosis in human lung (40) and prostate cancers (17). However, CD151 had not previously been shown to promote in vivo tumor progression in breast cancer or in any other type of cancer. Depletion of CD151 had no effect in vitro on proliferation or survival of MDA-MB-231 cells. Furthermore, in vivo studies showed that MDA-MB-231 tumor morphology was not altered, and apoptosis was not significantly increased in tumors formed from CD151-ablated cells. Hence, CD151 most likely affects the early stages of MDA-MB-231 tumor formation, in which cells initially encounter the extracellular matrix and invade into surrounding mammary fat pad tissue. Consistent with this, CD151 indeed affected the invasion and migration by basal-like mammary cells.

To learn how CD151 functions, we carried out in vitro studies using two different human basal-like mammary cell lines (immortalized MCF-10A and malignant MDA-MB-231 cells), with supporting results obtained using a few other cell lines. On ablation of CD151, but not other tetraspanins, MDA-MB-231 cell invasion through Matrigel was decreased by >80%. Support of invasion by CD151 is consistent with in vitro results seen in other tumor cell types (17, 40). In MCF-10A cells, removal of CD151 markedly impaired cell migration, consistent with a promigratory role for CD151 in epidermal carcinoma cells (20) but contrasting with antimigratory roles for CD151 in other cells (12, 19). CD151 is known to support adhesion strengthening (5), and cell migration is biphasic with respect to adhesion strength. Hence, we suggest that removal of CD151 may either impair or enhance cell migration depending on whether initial adhesion strength conditions are optimal or excessive, respectively.

CD151 closely associates with laminin-binding integrins (α3β1, α6β1, and α6β4) and affects their functions (3–5). Using mammary cell lines, we found CD151 association with α3β1, α6β1 and α6β4 integrins, and silencing of CD151 affected cell migration, invasion, spreading, and signaling on laminin, but not fibronectin. In our studies, depletion of CD151 from MDA-MB-231 cells mostly modulated α6 integrin functions. Elsewhere, MDA-MB-231 invasion and migration were shown to be α6β4 dependent (e.g., ref. 41). However, we cannot rule out contributions also from α3β1. Like CD151, laminin-binding integrins play a functional role in mammary tumors (24, 42). Furthermore, like CD151, laminin-binding integrins are elevated in human breast cancer (26), with α6β4 being a major marker of estrogen receptor–negative basal-like mammary tumors (25, 43).

Thus far, little insight has emerged about the mechanisms by which CD151 affects integrins. Although CD151 expression might affect integrin turnover (20), neither we nor others (12, 20, 21) observed any effect on integrin expression levels. Results elsewhere have suggested that the effects of CD151 on α3β1 integrin activation might underlie its effects on cell adhesion (21). However, removal of CD151 did not diminish an integrin β1 epitope commonly associated with integrin activation (data not shown). Here we show that CD151 affects the distribution and biochemical organization of α6 integrins on mammary cell lines. On MCF-10A cells, removal of CD151 altered α6 integrin localization to the cell periphery. Removal of CD151 also diminished the associations of α6 and α3 integrins with at least five other proteins, including other tetraspanins (CD9 and CD81). These results are consistent with CD151-integrin complexes functioning in the context of a larger constellation of proteins known as tetraspanin-enriched microdomains (1, 6). Major alterations in the integrin microenvironment, due to CD151 depletion, help to explain changes in integrin-dependent cell migration, invasion, spreading, and signaling.

On CD151 silencing, we observed diminished signaling through Rac1 and FAK in MDA-MB-231 cells plated on laminin-1. Because Rac1 and FAK typically play critical roles during invasion and migration, these results are consistent with CD151 silencing affecting mammary cell invasion and migration. Laminin-binding integrins and CD151 itself (12) can also markedly affect signaling through the PI3K/Akt pathway. Indeed, treatment of MDA-MB-231 cells with PI3K inhibitor Ly294002 almost completely abolished spreading and migration on laminin-1 substrate (data not shown). Hence, it was surprising that CD151 depletion did not decrease Akt signaling in MDA-MB-231 cells. One possibility is that the abundance of constitutively activated Ras found in MDA-MB-231 cells (44) maintains Akt in an activated state regardless of CD151. In an unexpected finding, CD151 ablation decreased activation of Lck but not Src (or Fyn or Yes). Although Src typically contributes to FAK signaling, Lck can also contribute (45), suggesting that CD151 depletion in MDA-MB-231 cells may impair Lck-FAK rather than Src-FAK signaling. Lck was recently implicated as playing a role during mammary tumor progression (34). Thus, decreased signaling through Lck may also contribute to the functional effects of CD151 depletion on MDA-MB-231 cells.

Functional and physical collaboration between α6 integrins and ErbB receptors has been noted (46, 47). For example, EGF stimulation of epithelial cells disrupts hemidesmosomes, releasing α6β4 to participate in cell motility and invasion (46, 48). We have not observed direct physical association of α6 integrins with ErbB receptors. Nonetheless, three results suggest that CD151 depletion disrupts integrin collaboration with EGFR: (a) Ablation of CD151 diminished EGF-dependent MCF-10A cell migration. (b) CD151 removal caused cell invasion and spreading deficits (in three different cell types) that could not be overcome by adding EGF, and in fact, (c) EGF no longer stimulated cell spreading and/or migration at all in CD151-silenced cells. These results are particularly relevant for basal-like mammary tumors because they tend to show elevated EGFR (25). Phorbol ester treatment also did not overcome CD151-knockdown effects on cell invasion and spreading (data not shown). Impaired responses to EGF and PMA, arising from CD151 silencing, again may be due to disruption of the α6 integrin microenvironment. In this regard, EGFR and protein kinase C (a target of PMA) have previously been linked to tetraspanins such as CD82, CD81, and CD9 (1, 49). Hence, ablation of CD151 may lead to diminished integrin proximity for these other tetraspanins and their associated signaling molecules.

In conclusion, we show here that CD151 is significantly elevated in multiple subtypes of breast cancer, including the basal-like subtype. Using prototype basal-like mammary cell lines, we show that CD151 contributes to mammary tumor progression. Whereas we mostly focused on basal-like mammary cells, CD151-depletion also affected invasion and/or EGF responsivity for two estrogen receptor–positive mammary cell lines [murine J110 cells (29) and an EGF-sensitive subline of MCF-7]. These results suggest that CD151 can also contribute to other types of breast cancer. In terms of mechanism, CD151 determines the molecular organization of laminin-binding integrins on the cell surface, thereby affecting integrin-dependent mammary cell morphology, migration, invasion, adhesion, signaling, EGFR cross talk, and ultimately, tumor progression in vivo. A previous study showed that CD151 could enhance tumor progression by supporting pathologic angiogenesis in host mice (12). Now we show that tumor cell CD151 also plays a key role, thus pointing to multiple levels of CD151 contributions, and emphasizing that CD151 may be a high-priority therapeutic target in certain breast cancers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support: NIH grant CA42368 (M.E. Hemler), a National Cancer Institute-Harvard Specialized Program of Research Excellence breast cancer award, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (A.L. Richardson), and a Claudia Adams Barr Award (X.H. Yang). M. Brown received sponsored research support and is a consultant to Novartis Co.

Footnotes

Supplementary data for this article are available at Cancer Research Online (http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/).

References

- 1.Hemler ME. Tetraspanin proteins mediate cellular penetration, invasion and fusion events, and define a novel type of membrane microdomain. Ann Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19:397–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111301.153609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitter S, Sincock PM, Jolliffe CN, Ashman LK. Transmembrane 4 superfamily protein CD151 (PETA- 3) associates with β1 and αIIbβ3 integrins in haemopoietic cell lines and modulates cell-cell adhesion. Biochem J. 1999;338:61–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sincock PM, Fitter S, Parton RG, Berndt MC, Gamble JR, Ashman LK. PETA-3/CD151, a member of the transmembrane 4 superfamily, is localised to the plasma membrane and endocytic system of endothelial cells, associates with multiple integrins and modulates cell function. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:833–44. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.6.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yánez-Mó M, Alfranca A, Cabañas C, et al. Regulation of endothelial cell motility by complexes of tetraspan molecules CD81/TAPA-1 and CD151/PETA-3 with α3β1 integrin localized at endothelial lateral junctions. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:791–804. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.3.791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lammerding J, Kazarov AR, Huang H, Lee RT, Hemler ME. Tetraspanin CD151 regulates α6β1 integrin adhesion strengthening. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7616–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1337546100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nydegger S, Khurana S, Krementsov DN, Foti M, Thali M. Mapping of tetraspanin-enriched microdomains that can function as gateways for HIV-1. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:795–807. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belkin AM, Stepp MA. Integrins as receptors for laminins. Microsc Res Tech. 2000;51:280–301. doi: 10.1002/1097-0029(20001101)51:3<280::AID-JEMT7>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karamatic Crew V, Burton N, Kagan A, et al. CD151, the first member of the tetraspanin (TM4) superfamily detected on erythrocytes, is essential for the correct assembly of human basement membranes in kidney and skin. Blood. 2004;104:2217–23. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wright MD, Geary SM, Fitter S, et al. Characterization of mice lacking the tetraspanin superfamily member CD151. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5978–88. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5978-5988.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sachs N, Kreft M, van den Bergh Weerman MA, et al. Kidney failure in mice lacking the tetraspanin CD151. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:33–9. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200603073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cowin AJ, Adams D, Geary SM, Wright MD, Jones JC, Ashman LK. Wound healing is defective in mice lacking tetraspanin CD151. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:680–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takeda Y, Kazarov AR, Butterfield CE, et al. Deletion of tetraspanin Cd151 results in decreased pathologic angiogenesis in vivo and in vitro. Blood. 2007;109:1524–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-041970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lau LM, Wee JL, Wright MD, et al. The tetraspanin superfamily member, CD151 regulates outside-in integrin αIIbβ3 signalling and platelet function. Blood. 2004;104:2368, 75. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4430. 104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wright MD, Moseley GW, van Spriel AB. Tetraspanin microdomains in immune cell signalling and malignant disease. Tissue Antigens. 2004;64:533–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2004.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Testa JE, Brooks PC, Lin JM, Quigley JP. Eukaryotic expression cloning with an antimetastatic monoclonal antibody identifies a tetraspanin (PETA-3/CD151) as an effector of human tumor cell migration and metastasis. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3812–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zavadil J, Bitzer M, Liang D, et al. Genetic programs of epithelial cell plasticity directed by transforming growth factor-β. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6686–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111614398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ang J, Lijovic M, Ashman LK, Kan K, Frauman AG. CD151 protein expression predicts the clinical outcome of low-grade primary prostate cancer better than histologic grading: a new prognostic indicator? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:1717–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng ZZ, Liu ZX. Activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase Akt pathway mediates CD151-induced endothelial cell proliferation and cell migration. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:340–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia-Lopez MA, Barreiro O, Garcia-Diez A, Sanchez-Madrid F, Penas PF. Role of tetraspanins CD9 and CD151 in primary melanocyte motility. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:1001–9. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winterwood NE, Varzavand A, Meland MN, Ashman LK, Stipp CS. A critical role for tetraspanin CD151 in α3β1 and α6β4 integrin-dependent tumor cell functions on laminin-5. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:2707–21. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-11-1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishiuchi R, Sanzen N, Nada S, et al. Potentiation of the ligand-binding activity of integrin α3β1 via association with tetraspanin CD151. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1939–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409493102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaw LM, Rabinovitz I, Wang HH, Toker A, Mercurio AM. Activation of phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase by the α6β4 integrin promotes carcinoma invasion. Cell. 1997;91:949–60. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80486-9. 91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zahir N, Lakins JN, Russell A, et al. Autocrine laminin-5 ligates α6β4 integrin and activates RAC and NFnB to mediate anchorage-independent survival of mammary tumors. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:1397–407. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo W, Pylayeva Y, Pepe A, et al. β4 integrin amplifies ErbB2 signaling to promote mammary tumorigenesis. Cell. 2006;126:489–502. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–52. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diaz LK, Cristofanilli M, Zhou X, et al. β4 integrin subunit gene expression correlates with tumor size and nuclear grade in early breast cancer. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1165–75. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedrichs K, Ruiz P, Franke F, Gille I, Terpe H-J, Imhof BA. High expression level of α6 integrin in human breast carcinoma is correlated with reduced survival. Cancer Res. 1995;55:901–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neve RM, Chin K, Fridlyand J, et al. A collection of breast cancer cell lines for the study of functionally distinct cancer subtypes. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:515–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Torres-Arzayus MI, Yuan J, DellaGatta JL, Lane H, Kung AL, Brown M. Targeting the AIB1 oncogene through mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition in the mammary gland. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11381–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang X, Claas C, Kraeft SK, et al. Palmitoylation of tetraspanin proteins: modulation of CD151 lateral interactions, subcellular distribution, and integrin-dependent cell morphology. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:767–81. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-05-0275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang X, Kovalenko OV, Tang W, Claas C, Stipp CS, Hemler ME. Palmitoylation supports assembly and function of integrin-tetraspanin complexes. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:1231–40. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200404100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schlaepfer DD, Mitra SK, Ilic D. Control of motile and invasive cell phenotypes by focal adhesion kinase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1692:77–102. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitra SK, Hanson DA, Schlaepfer DD. Focal adhesion kinase: in command and control of cell motility. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:56–68. doi: 10.1038/nrm1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chakraborty G, Rangaswami H, Jain S, Kundu GC. Hypoxia regulates cross-talk between Syk and Lck leading to breast cancer progression and angiogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:11322–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512546200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ridley AJ, Allen WE, Peppelenbosch M, Jones GE. Rho family proteins and cell migration. Biochem Soc Symp. 1999;65:111–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoeli-Lerner M, Toker A. Akt/PKB signaling in cancer: a function in cell motility and invasion. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:603–5. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.6.2561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoon SO, Shin S, Mercurio AM. Hypoxia stimulates carcinoma invasion by stabilizing microtubules and promoting the Rab11 trafficking of the α6β4 integrin. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2761–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hemler ME. Tetraspanin functions and associated microdomains. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:801–11. doi: 10.1038/nrm1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berditchevski F. Complexes of tetraspanins with integrins: more than meets the eye. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:4143–51. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.23.4143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tokuhara T, Hasegawa H, Hattori N, et al. Clinical significance of CD151 gene expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:4109–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rabinovitz I, Mercurio AM. The integrin α6β4 functions in carcinoma cell migration on laminin-1 by mediating the formation and stabilization of actin-containing motility structures. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1873–84. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.7.1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chung J, Mercurio AM. Contributions of the α6 integrins to breast carcinoma survival and progression. Mol Cells. 2004;17:203–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yehiely F, Moyano JV, Evans JR, Nielsen TO, Cryns VL. Deconstructing the molecular portrait of basal-like breast cancer. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:537–44. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ogata H, Sato H, Takatsuka J, De Luca LM. Human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells fail to express the neurofibromin protein, lack its type I mRNA isoform and show accumulation of P-MAPK and activated Ras. Cancer Lett. 2001;172:159–64. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00648-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goldmann WH. p56(lck) Controls phosphorylation of filamin (ABP-280) and regulates focal adhesion kinase (pp125(FAK)) Cell Biol Int. 2002;26:567–71. doi: 10.1006/cbir.2002.0900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mariotti A, Kedeshian PA, Dans M, Curatola AM, Gagnoux-Palacios L, Giancotti FG. EGF-R signaling through Fyn kinase disrupts the function of integrin α6β4 at hemidesmosomes: role in epithelial cell migration and carcinoma invasion. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:447–58. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200105017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Falcioni R, Antonini A, Nistico P, et al. α6β4 and α6β1 integrins associate with ErbB-2 in human carcinoma cell lines. Exp Cell Res. 1997;236:76–85. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rabinovitz I, Tsomo L, Mercurio AM. Protein kinase Ca phosphorylation of specific serines in the connecting segment of the β4 integrin regulates the dynamics of type II hemidesmosomes. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4351–60. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4351-4360.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Odintsova E, Voortman J, Gilbert E, Berditchevski F. Tetraspanin CD82 regulates compartmentalisation and ligand-induced dimerization of EGFR. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4557–66. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kovalenko OV, Yang XH, Hemler ME. A novel cysteine cross-linking method reveals a direct association between claudin-1 and tetraspanin CD9. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:1855–67. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700183-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.