Abstract

With great theoretical and practical significance, locating influential nodes of complex networks is a promising issue. In this paper, we present a dynamics-sensitive (DS) centrality by integrating topological features and dynamical properties. The DS centrality can be directly applied in locating influential spreaders. According to the empirical results on four real networks for both susceptible-infected-recovered (SIR) and susceptible-infected (SI) spreading models, the DS centrality is more accurate than degree, k-shell index and eigenvector centrality.

Spreading dynamics represents many important processes in nature and society1,2, such as the propagation of computer viruses3 and traffic congestion4, reaction diffusion5, spreading of infectious diseases6 and cascading failures7. The estimation of nodes’ spreading influences can help in hindering epidemics or accelerating innovation8, and similar methods can be further applied in identifying influential spreaders in social networks9, quantifying the influence of scientists and their publications10, evaluating the impacts of injection points in the diffusion of microfinance11, finding drug targets in directed pathway networks12, predicting essential proteins in protein interaction networks13, and so on.

The significance of this issue triggers a variety of novel approaches in identifying influential spreaders in networks, which can be roughly categorized into three classes. Firstly, some scientists argued that the location of a node is more important than its immediate neighbors, and thus proposed k-shell index14,15 and its variants16,17,18,19 as indicators of spreading influences. Secondly, some scientists quantified a node’s influence only accounting for its local surroundings20,21,22. Thirdly, some scientists evaluated nodes’ influences according to the steady states of some introduced dynamical processes, such as random walk23,24 and iterative refinement25.

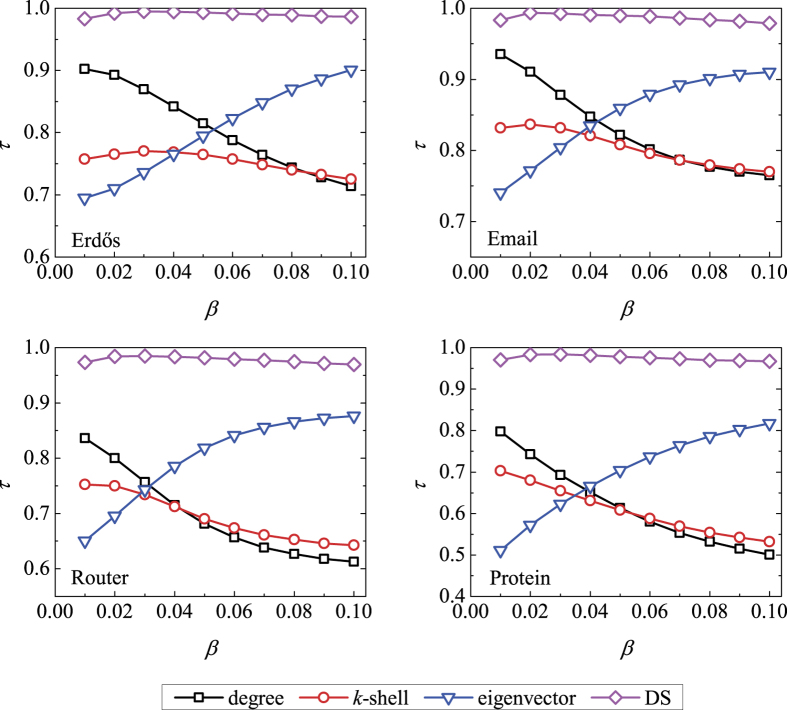

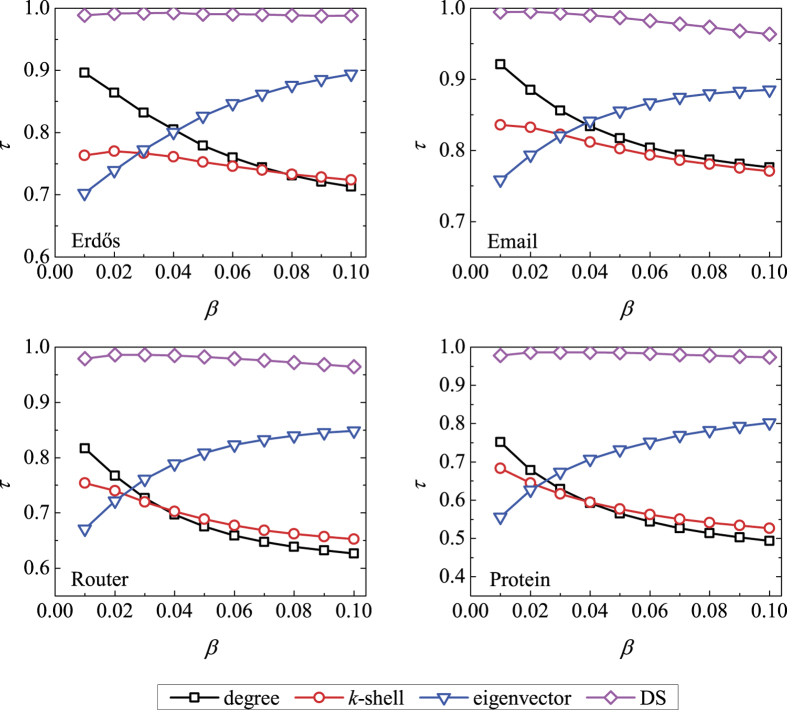

The above-mentioned approaches only take into account the topological features, while recent experiments indicate that the performance of structural indices is very sensitive to the specific dynamics on networks26,27,28. For example, when the spreading rate is very small, the degree usually performs better than the eigenvector centrality29 and k-shell index14, while when the infectivity is very high, the eigenvector centrality is the best one among the three (see Figs 1 and 2, with details shown later). To the best of our knowledge, there are few works taking into account the properties of the underlying spreading dynamics30,31,32. Encoding the interplay between topology and dynamics, Klemm et al.30 suggested that the eigenvector centrality can be used in estimating nodes’ dynamical influences in the susceptible-infected-recovered (SIR) spreading model (also called susceptible-infected-removed model)33. Li et al.31 provided complementary explanation of the suitability of eigenvector centrality based on perturbation around the equilibrium of the epidemic dynamics and discussed the limitations of eigenvector centrality for homogeneous community networks. Both the above two works did not pay enough attention to the specific parameters in the spreading models, and thus their suggested index only works well in a limited range of the parameter space. Bauer and Lizier32 proposed an approach based on counting the number of possible infection walks with different lengths to approximate the number of infected nodes generated by a given initially infected node. Their method is an effective one to predict the outbreak size over a wide range of spreading rate but less efficient due to the considerable computational cost. In addition, for the fundamental complexity in counting the number of paths connecting two nodes, their method could not be formulated in a compact analytical form.

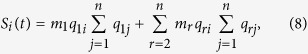

Figure 1. The accuracy of four centrality measures in evaluating nodes’ spreading influences according to the SIR model (μ = 1) in the four real networks, quantified by the Kendall’s Tau.

The spreading rate β varies from 0.01 to 0.10, and the time step is set as t = 5. Each data point is obtained by averaging over 104 independent runs.

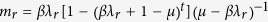

Figure 2. The accuracy of four centrality measures in evaluating nodes’ spreading influences according to the SI model (μ = 0) in the four real networks, quantified by the Kendall’s Tau.

The spreading rate β varies from 0.01 to 0.10, and the time step is set as t = 5. Each data point is obtained by averaging over 104 independent runs.

In this paper, we describe the infectious probabilities of nodes by a matrix differential function that accounts both topological features and dynamical properties. Accordingly, we propose a dynamics-sensitive (DS) centrality to predict the outbreak size at given time step, which can be directly applied in quantifying the spreading influences of nodes. According to the empirical results on four real networks, for both the SIR model33 and the susceptible-infected (SI) model34,35, the DS centrality can locate influential nodes accurately and performs particularly well in the early stage of spreading. The method proposed in this paper can be extended to other Markov processes on networks.

Dynamics-Sensitive Centrality

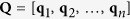

A simple undirected connected network G = (V, E) with  nodes and

nodes and  links could be described by an adjacency matrix

links could be described by an adjacency matrix  where aij = 1 if node i is connected with node j, and aij = 0 otherwise. A is binary and symmetric with zeros along the main diagonal, and thus its eigenvalues are real and can be arrayed in a descending order as

where aij = 1 if node i is connected with node j, and aij = 0 otherwise. A is binary and symmetric with zeros along the main diagonal, and thus its eigenvalues are real and can be arrayed in a descending order as  . Since A is a symmetric and real-valued matrix, it can be factorized as

. Since A is a symmetric and real-valued matrix, it can be factorized as  , where

, where  ,

,  and qi is the eigenvector of the eigenvalue λi.

and qi is the eigenvector of the eigenvalue λi.

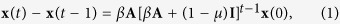

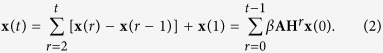

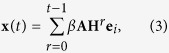

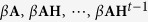

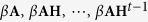

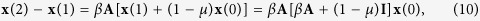

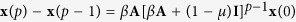

We consider a discrete-time spreading model where an infected node would infect its neighbors with spreading rate β and recover with recovering rate μ (see Materials and Methods for details). Denote x(t) (t > 0) as an approximation of the cumulative probabilities that nodes are excited between time step 1 and t, and then x(t) − x(t − 1) (t > 1) is approximated as the probabilities of nodes to be infected at time step t. If i is the only initially infected node, then xi(0) = 1 and xj≠i(0) = 0. In the first time step, x(1) = βAx(0), and for t > 1, we have (see the derivation in Materials and Methods)

|

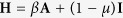

where I is the identity matrix. Denoting  , then

, then  represents the probabilities of nodes to be infected at time step t, and thus the cumulative probabilities of nodes to have been infected between time step 1 and t can be approximated as

represents the probabilities of nodes to be infected at time step t, and thus the cumulative probabilities of nodes to have been infected between time step 1 and t can be approximated as

|

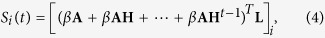

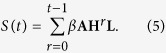

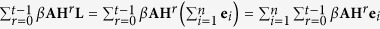

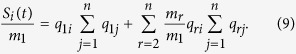

We define Si(t) to be the spreading influence of node i at time step t, which can be quantified by the sum of infected probabilities of all nodes, given i the initially infected seed. According to Eq. (2), the infected probabilities can be written as

|

where ei = (0, …, 0, 1, 0, …, 0)T is an n × 1 vector with only the ith element being 1. As all elements other than the ith one of ei are zero, x(t) is indeed the sum of all the ith columns of  . Given x(0) = ei, Si(t) is defined as the sum of all elements of x(t), which is equal to the sum of all elements in the ith columns of

. Given x(0) = ei, Si(t) is defined as the sum of all elements of x(t), which is equal to the sum of all elements in the ith columns of  , as

, as

|

where L = (1, 1, …, 1)T is an n × 1 vector whose components are all 1. Obviously, AT = A, HT = H and AH = HA, so the spreading influence of all nodes can be described by the vector

|

Notice that,  , and

, and  is the infected probabilities of all nodes given node i the only initially infected seed according to Eq. (2), so S(t) can also be roughly explained as the sum of infected probabilities over the n cases with every node being the infected seed once. This relationship shows an underlying symmetry, that is, in an undirected network, the node having higher influence is also the one apt to be infected. The readers are warned that such conclusion is not mathematically rigorous since we have ignored the complicated entanglement by allowing the elements of x(t) being larger than 1.

is the infected probabilities of all nodes given node i the only initially infected seed according to Eq. (2), so S(t) can also be roughly explained as the sum of infected probabilities over the n cases with every node being the infected seed once. This relationship shows an underlying symmetry, that is, in an undirected network, the node having higher influence is also the one apt to be infected. The readers are warned that such conclusion is not mathematically rigorous since we have ignored the complicated entanglement by allowing the elements of x(t) being larger than 1.

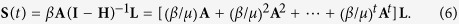

The eigenvectors of H are the same to the ones of A and βλi + 1 − μ is the ith eigenvalue of H, corresponding to qi. When βλ1 + 1 − μ < 1, i.e. β/μ < 1/λ1 (for the case μ ≠ 0), HtL could converge to null vector when t→∞ and S(t) could be written by the following way

|

For simplicity, in the SIR model, we set μ = 1, and then

|

where (AtL)i counts the total number of walks of length t from node i to all nodes in the network, weighted by βt that decays as the increase of the length t. As S(t) quantifies nodes’ spreading influences, we call it dynamics-sensitive (DS) centrality, where the term dynamics-sensitive emphasizes the fact that S(t) is determined not only by the network structure (i.e., A), but also the dynamical parameters (i.e., β and t). In particular, when t = 1, the initially infected node only has the chance to infect its neighbors and Si(1) = (βAL)i with (AL)i being exactly the degree of node i. When μ = 0 (corresponding to the SI model) or β ≥ 1/λ1, S(t) would be infinite when t→∞, which could not reflect the spreading influences. In fact, there are two underlying assumptions. Firstly, the DS centrality calculates the probabilities of the nodes to be infected at time step t by linear coupling instead of nonlinear coupling. For example, if a susceptible node has m infected neighbors, the probability of the node to be infected is approximated as mβ by the DS centrality, instead of 1 − (1 − β)m, which is the exact probability of the node to be infected. Secondly, the DS centrality calculates the probabilities of nodes to be infected under the assumption that the nodes are susceptible at time steps t. Notice that, our main goal is to find out the ranking of spreading influences of nodes, namely to identify influential nodes. As every node’s infected probability is overestimated, the ranking may be less affected. Thus far, we are still not aware of the impacts on the ranking, while fortunately, as later indicated by the extensive numerical results, the DS centrality performs much better than other well-known indices for a very broad ranges of β and t that cover most practical scenarios.

Results

We test the performance of DS centrality in evaluating the nodes’ spreading influences according to the SIR model and SI model, with varying spreading rate β. Four real networks, including a scientific collaboration network, an email communication network, the Internet at the router level and a protein-protein interaction network, are used for the empirical analysis (see data description in Materials and Methods), and three well-known indices, including degree, k-shell index and eigenvector centrality, are used as benchmark methods for comparison (see Materials and Methods for the definitions of those indices). Given the time step t, the spreading influence of an arbitrary node i is quantified by the number of infected nodes (for SI model) or the number of infected and recovered nodes (for SIR model) at t, where the spreading process starts with only node i being initially infected. Here we use Kendall’s Tau τ36 to measure the correlation between nodes’ spreading influences and the considered centrality measure, where τ is in the range [−1, 1] and the larger τ corresponds to the better performance (see Materials and Methods for the definition of τ).

As shown in Fig. 1, the Kendall’s Tau τ for the DS centrality is between 0.968 and 0.995 for  , indicating that the ranking lists generated by the DS centrality and the real SIR spreading process are highly identical to each other. In comparison, the DS centrality performs better than degree, k-shell index and eigenvector centrality since the DS centrality takes into account one more parameter β. As shown in Fig. 2, similar results are also observed for the SI model where the DS centrality performs better than others. The results for larger β and t are respectively shown in Figs S1 and S2 of Supplementary Information, where the DS centrality still could locate influential nodes accurately. Meanwhile, Fig. S3 shows that the DS centrality also performs much better than other compared indices in evaluating the nodes’ spreading influences for μ = 0.3 and 0.7 in the SIR model.

, indicating that the ranking lists generated by the DS centrality and the real SIR spreading process are highly identical to each other. In comparison, the DS centrality performs better than degree, k-shell index and eigenvector centrality since the DS centrality takes into account one more parameter β. As shown in Fig. 2, similar results are also observed for the SI model where the DS centrality performs better than others. The results for larger β and t are respectively shown in Figs S1 and S2 of Supplementary Information, where the DS centrality still could locate influential nodes accurately. Meanwhile, Fig. S3 shows that the DS centrality also performs much better than other compared indices in evaluating the nodes’ spreading influences for μ = 0.3 and 0.7 in the SIR model.

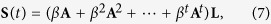

Since A is a symmetric, real-valued matrix, the DS centrality S(t) can be written in the following way by decomposing A

|

where  for 1 ≤ r ≤ n. Rewriting Eq. (8) into

for 1 ≤ r ≤ n. Rewriting Eq. (8) into

|

With the increase of t and β,  will converge to 0, and thus the ranking lists generated by S(t) will be identical to q1, which is exactly the same to the eigenvector centrality. This relationship is in accordance with the results presented in Figs S1 and S2, where the difference between the eigenvector centrality and DS centrality gets smaller as the increase of β and t.

will converge to 0, and thus the ranking lists generated by S(t) will be identical to q1, which is exactly the same to the eigenvector centrality. This relationship is in accordance with the results presented in Figs S1 and S2, where the difference between the eigenvector centrality and DS centrality gets smaller as the increase of β and t.

Conclusion and Discussions

Estimating the spreading influences and then identifying influential nodes are fundamental task before any regulation on the spreading process. For such task, most known works only took into account the topological information8. Recently, Aral and Walker37 showed that the attributes of nodes are highly correlated with nodes’ influences and tendencies to be influenced. In this paper, in addition to the topological information, we get down to the underlying spreading dynamics and propose a dynamics-sensitive (DS) centrality, which is a kind of weighted sum of walks ending at the target node, where both the spreading rate and spreading time are accounted in the weighting function. The DS centrality can be directly applied in quantifying the spreading influences of nodes. According to the empirical analyses of the SIR model and SI model at given time step on four real networks, the DS centrality can locate influential nodes much more accurately than degree, k-shell index and eigenvector centrality. In fact, it is unfair to directly compare the DS centrality with the above structure-based indices since the DS centrality takes into account one more parameter β, while the present result is still significant as it gives an elegant way to account the specific dynamics and shows the remarkable improvement by introducing the parameter β, which may be expected but not yet well demonstrated before this paper.

The DS centrality performs particularly well in the early stage of spreading, which provides a powerful tool in early detection of potential super-spreaders for epidemic control. Notice that, we did not consider the asymptotical case with t→∞, since after sufficiently long spreading time, all nodes in the network would be infected under large spreading rate, especially in the SI model. In such case, different nodes spreading influences are not distinguishable.

The DS centrality tells us an often ignored fact that the most influential nodes are dependent not only on the network topology but also on the spreading dynamics. Given different models and parameters, the relative influences of nodes are also different. Roughly speaking, if the spreading rate is small, we can focus on the close neighborhood of a node since it is not easy to form a long spreading pathway (i.e., βt decays very fast as the increase of t when β is small) while if the spreading rate is high, the global topology should be considered. A clear limitation of this work is that before calculating the DS centrality, we have to know the spreading rate that is usually a hidden parameter. This parameter can be effectively estimated according to the early spreading process38 and then we can calculate the DS centralities by varying the spreading rates over the estimated range and see which nodes are the most influential ones in average. In addition to the identification of the most influential node, a related but more challenging problem is to find the most influential sets of nodes39. The DS centrality could not be directly extended to solve this problem, however, similar to the present idea, the dynamical information is very necessary in dealing with this problem40.

Some other centralities related to specific dynamical processes have also been proposed recently, including routing centrality41, epidemic centrality42, diffusion centrality43, percolation centrality44 and game centrality45. Comparing with these centralities, similar to the works by Klemm et al.30,46,47, this paper provides a more general framework that could deal with other Markov processes and thus can be extended and applied in many other important dynamics, such as the Ising model48, Boolean dynamics49, voter model50, synchronization51, and so on. For example, Zhou et al.35 considered a variant SIR spreading model where an infected node can only contact one neighbor in one time step. In this case, the adjacency matrix A in the DS centrality could be replaced by D−1 A, where D is an n × n matrix where ith main diagonal element is the degree of node i and other elements are 0. Then the DS centrality can be extended to this spreading model. Furthermore, the DS centrality can also be directly extended to asymmetrical networks and weighted networks. We hope this work could highlight the significant role of underlying dynamics in quantifying the individual nodes’ importance, and then the difference between lists of critical nodes for different dynamical processes could be considered as their distinguished properties.

Materials and Methods

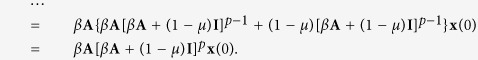

Derivation of Eq. (1)

The probabilities of nodes to be infected at time step t = 2 can be approximated as

|

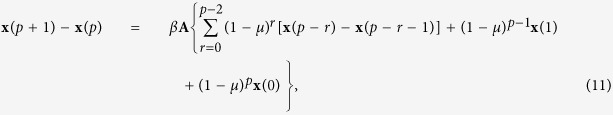

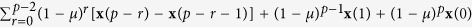

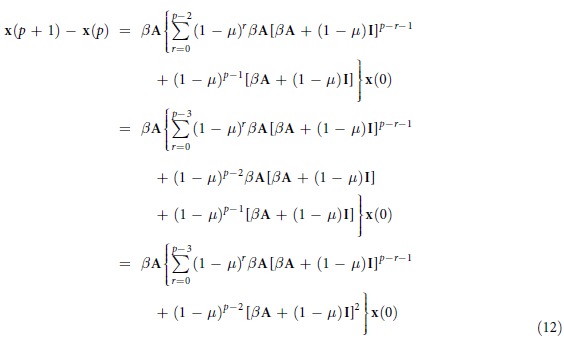

where x(1) + (1 − μ)x(0) is the probabilities that nodes still have the ability to infect the susceptible nodes at time step 2. We assume that when t ≤ p,  , then for t = p + 1, we have

, then for t = p + 1, we have

|

where  is the probabilities that nodes still have the ability to infect the susceptible nodes at time step p + 1. Therefore, we can get that

is the probabilities that nodes still have the ability to infect the susceptible nodes at time step p + 1. Therefore, we can get that

|

|

Therefore, according to the mathematical induction, Eq. (1) is established.

Spreading Model

Here we apply the susceptible-infected-recovered (SIR) model (also called the susceptible-infected-removed model)33. In the SIR model, there are three kinds of individuals: (i) susceptible individuals that could be infected, (ii) infected individuals having been infected and being able to infect susceptible individuals, and (iii) recovered individuals that have been recovered and will never be infected again. In this paper, the spreading process starts with only one seed node being infected initially, and all other nodes are initially susceptible. At each time step, each infected node makes contact with its neighbors and each susceptible neighbor is infected with a probability β. Then each infected node enters the recovered state with a probability μ. In the main text we set μ = 1, and for other values of μ, the results are very similar (see SI). In the standard SI model, nodes can only be susceptible or infected, corresponding to the case with μ = 0. In this paper, the model, analysis and simulations are all based on the discrete-time dynamics.

Benchmark Methods

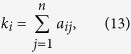

The degree of an arbitrary node i is defined as the number of its neighbors, namely

|

where aij is the element of matrix A. Degree centrality is widely applied for its simplicity and low computational cost, which works especially well in evaluating nodes’ spreading influences when the spreading rate is small.

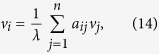

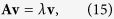

The main idea of eigenvector centrality is that a node’s importance is not only determined by itself, but also affected by its neighbors’ importance29. Accordingly, eigenvector centrality of node i, vi, is defined as

|

where λ is a constant. Obviously, Eq. (13) can be written in a compact form as

|

where  . That is to say, v is the eigenvector of the adjacency matrix A and λ is the corresponding eigenvalue. Since the considered network is a simple undirected connected network and thus the adjacency matrix A is irreducible. According to Perron-Frobenius Theorem52, the elements in the leading eigenvector are strictly positive. Since the influences of nodes should be strictly positive, v must be the leading eigenvector corresponding to the largest eigenvalue of A, say v = q1.

. That is to say, v is the eigenvector of the adjacency matrix A and λ is the corresponding eigenvalue. Since the considered network is a simple undirected connected network and thus the adjacency matrix A is irreducible. According to Perron-Frobenius Theorem52, the elements in the leading eigenvector are strictly positive. Since the influences of nodes should be strictly positive, v must be the leading eigenvector corresponding to the largest eigenvalue of A, say v = q1.

Kitsak et al.14 argued that k-shell index (i.e., coreness) is a better index than degree to locate the influential nodes. The k-shell can be obtained by the so-called k-core decomposition53. The k-core decomposition process is initiated by removing all nodes with degree k = 1. This causes new nodes with degree k ≤ 1 to appear. These are also removed and the process is continued until all remaining nodes are of degree k > 1. The removed nodes (together with associated links) form the 1-shell, and their k-shell indices are all one. We next repeat this pruning process for the nodes of degree k = 2 to extract the 2-shell, that is, in each step the nodes with degree k ≤ 2 are removed. We continue with the process until we have identified all higher-layer shells and all network nodes have been removed. Then each node i is assigned a k-shell index ci.

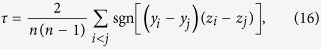

Kendall’s Tau

For each node i, we denote yi as its spreading influence and zi the target centrality measure (e.g., degree, k-shell index, eigenvector centrality and DS centrality), the accuracy of the target centrality in evaluating nodes’ spreading influences can be quantified by the Kendall’s Tau36, as

|

where sgn(y) is a piecewise function, when y > 0, sgn(y) = +1; y < 0, sgn(y) = −1; when y = 0, sgn(y) = 0. τ measures the correlation between two ranking lists, whose value is in the range [−1, 1] and the larger τ corresponds to the better performance.

Data Description

Four real networks are studied in this paper as follows. (i) Erdös, a scientific collaboration network, where nodes are scientists and edges represent the co-authorships. The data set can be freely downloaded from the web site http://wwwp.oakland.edu/enp/thedata/. (ii) Email54, which is the email communication network of University Rovira i Virgili (URV) of Spain, involving faculty members, researchers, technicians, managers, administrators, and graduate students. (iii) Router55, the Internet at the router level, where each node represents a router and an edge represents a connection between two routers. (iv) Protein56, an initial version of a proteome-scale map of human binary protein-protein interaction. Basic statistical properties of the above four networks are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Basic statistical features of Erdös, Email, Router and Protein networks, including the number of nodes n, the number of the edges e, the average degree  and the reciprocal of the largest eigenvalue 1/λ1.

and the reciprocal of the largest eigenvalue 1/λ1.

| Network | n | e |  |

1/λ1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erdös | 454 | 1313 | 5.784 | 0.079 |

| 1133 | 5451 | 9.622 | 0.048 | |

| Router | 2114 | 6632 | 6.274 | 0.036 |

| Protein | 2783 | 6007 | 4.317 | 0.063 |

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Liu, J.-G. et al. Locating influential nodes via dynamics-sensitive centrality. Sci. Rep. 6, 21380; doi: 10.1038/srep21380 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the valuable discussion with Wen-Xu Wang and Liming Pan, as well as the Erdös Number Project in Oakland University for the data set. This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos 71171136, 61374177, 11222543 and 61433014), JGL is supported by the Program for Professor of Special Appointment (Eastern Scholar) at Shanghai Institutions of Higher Learning and the Shuguang Program Project of Shanghai Educational Committee (Grant No. 14SG42).

Footnotes

Author Contributions J.-G.L., J.-H.L. and T.Z. designed research, J.-G.L., J.-H.L. and Q.G. perform research, J.-G.L., J.-H.L. and T.Z. analysed data, and J.-G.L., J.-H.L., Q.G. and T.Z. wrote the paper.

References

- Zhou T., Fu Z. Q. & Wang B. H. Epidemic dynamics on complex networks. Porg. Nat. Sci. 16, 452 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Pastor-Satorras R., Castellano C., Van Mieghem P. & Vespignani A. Epidemic processes in complex networks. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 925 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Kephart J. O., Sorkin G. B., Chess D. M. & White S. R. Fighting computer viruses. Sci. Am. 277, 56 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Li D. et al. Percolation transition in dynamical traffic network with evolving critical bottlenecks. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 69 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colizza V., Pastor-Satorras R. & Vespignani A. Reaction-diffusion processes and metapopulation models in heterogeneous networks. Nat. Phys. 3, 276 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Keeling M. J. & Rohani P. Modeling Infectious Diseases in Humans and Animals. Princeton University Press, Princeton (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Motter A. E. Cascade control and defense in complex networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 098701 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei S. & Makse H. A. Spreading dynamics in complex networks. Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment 2013, P12002 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- González-Bailón S., Borge-Holthoefer J., Rivero A. & Moreno Y. The dynamics of protest recruitment through an online network. Sci. Rep. 1, 197 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y. B., Lü L. & Li M. Quantifying the influence of scientists and their publications: distinguishing between prestige and popularity. New. J. Phys. 14, 033033 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A., Chandrasekhar A. G., Duflo E. & Jackson M. O. The diffusion of microfinance. Science 341, 1236498 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csermely P., Korcsmáros T., Kiss H. J., London G. & Nussinov R. Structure and dynamics of molecular networks: a novel paradigm of drug discovery: a comprehensive review. Pharmacol. Ther. 138, 333 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Zhang H., Wang J. X. & Pan Y. A new essential protein discovery method based on the integration of protein-protein interaction and gene expression data. BMC Syst. Biol. 6, 15 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitsak M. et al. Identification of influential spreaders in complex networks. Nat. Phys. 6, 888 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Castellano C. & Pastor-Satorras R. Competing activation mechanisms in epidemics on networks. Sci. Rep. 2, 371 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng A. & Zhang C. J. Ranking spreaders by decomposing complex networks. Phys. Lett. A 377, 1031 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. G., Ren Z. M. & Guo Q. Ranking the spreading influence in complex networks. Physica A 392, 4154 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Lin J. H., Guo Q., Dong W. Z., Tang L. Y. & Liu J. G. Identifying the node spreading influence with largest k-core values. Phys. Lett. A 378, 3279 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Tang M., Zhou T. & Do Y. Improving the accuracy of the k-shell method by removing redundant links: From a perspective of spreading dynamics. Sci. Rep. 5, 13172 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D. B., Lü L., Shang M. S., Zhang Y. C. & Zhou T. Identifying influential nodes in complex networks. Physica A 391, 1777 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Chen D. B., Gao H., Lü L. & Zhou T. Identifying influential nodes in large-scale directed networks: the role of clustering. PLoS ONE 8, e77455 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei S., Muchnik L., Andrade J. S. Jr., Zheng Z. & Makse H. A. Searching for superspreaders of information in real-world social media. Sci. Rep. 4, 5547 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lü L., Yeung C. H., Zhang Y. C. & Zhou T. Leaders in social networks, the delicious case. PLoS ONE 6, e21202 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Zhou T., Lü L. & Chen D. B. Identifying influential spreaders by weighted LeaderRank. Physica A 404, 47 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Ren Z. M., Zeng A., Chen D. B., Liao H. & Liu J. G. Iterative resource allocation for ranking spreaders in complex networks. EPL 106, 48005 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Borge-Holthoefer J., Rivero A. & Moreno Y. Locating privileged spreaders on an online social network. Phys. Rew. E 85, 066123 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borge-Holthoefer J. & Moreno Y. Absence of influential spreaders in rumor dynamics. Phys. Rew. E 85, 026116 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Tang M., Zhou T. & Do Y. Core-like groups resulting in invalidation of k-shell decomposition analysis. Sci. Rep. 5, 9602 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti S. P. Centrality and network flow. Soc. Netw. 27, 55 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Klemm K., Serrano M. A., Eguiluz V. M. & San Miguel M. A measure of individual role in collective dynamics. Sci. Rep. 2, 292 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P., Zhang J., Xu X. K. & Small M. Dynamical influence of node revisited: a markov chain analysis of epidemic process on networks. Chin. Phys. Lett. 29, 048903 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Bauer F. & Lizier J. T. Identifying influential spreaders and efficiently estimating infection numbers in epidemic models: a walk counting approache. EPL 99, 68007 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Hethcote H. W. The mathematics of infectious diseases. SIAM Rev. 42, 599 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Barthélemy M., Barrat A., Pastor-Satorras R. & Vespignani A. Velocity and hierarchical spread of epidemic outbreaks in scale-free networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 178701 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T., Liu J. G., Bai W. J., Chen G. & Wang B. H. Behaviors of susceptible-infected epidemics on scale-free networks with identical infectivity. Phys. Rev. E 74, 056109 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall M. G. A new measure of rank correlation. Biometrika 30, 81 (1938). [Google Scholar]

- Aral S. & Walker D. Identifying influential and susceptible members of social networks. Science 68, 337 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D. B., Xiao R. & Zeng A. Predicting the evolution of spreading on complex networks. Sci. Rep. 4, 6108 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempe D., Kleinberg J. & Tardosé É. Maximizing the spread of influence through a social network. Proceedings of the 9th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (pp. 137–146, AAAI Press, 2015).

- Morone F. & Makse H. A. Influence maximization in complex networks through optimal percolation. Nature 524, 65 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolev S., Elovici Y. & Puzis R. Routing betweenness centrality. J. ACM 57(4), 25 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šikić M., Lančić A., Antulov-Fantulin N. & Štefančić H. Epidemic centrality – is there an underestimated epidemic impact of network peripheral nodes? Eur. Phys. J. B 86, 440 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Ide K., Zamami R. & Namatame A. Diffusion Centrality in Interconnected Networks. Proc. Comput. Sci. 24, 227 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Piraveenan M., Prokopenko M. & Hossain L. Percolation centrality: Quantifying graph-theoretic impact of nodes during percolation in networks. PLoS One 8, e53095 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simko G. I. & Csermely P. Nodes having a major influence to break cooperation define a novel centrality measure: game centrality. PLoS One 8, e67159 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanbarnejad F. & Klemm K. Impact of individual nodes in Boolean network dynamics. EPL 99, 58006 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Klemm K. Searchability of Central Nodes in Networks. J. Stat. Phys. 151, 707 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Dorogovtsev S. N., Goltsev A. V. & Mendes J. F. Critical phenomena in complex networks. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 1275 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman S. A. The Origins of Order. Oxford University Press, New York, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano C., Fortunato S. & Loreto V. Statistical physics of social dynamics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 591 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Arenas A., Díaz-Guilera A., Kurths J., Moreno Y. & Zhou C. Synchronization in complex networks. Phys. Rep. 469 93 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Hom R. A. & Johnson C. R. Matrix Analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1985). [Google Scholar]

- Seidman S. B. Network structure and minimum degree. Soc. Net. 5, 269 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- Guimera R., Danon L., Diaz-Guilera A., Giralt F. & Arenas A. Self-similar community structure in a network of human interactions. Phys. Rew. E 68, 065103 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi R. A. & Ahmed N. K. The Network Data Repository with Interactive Graph Analytics and Visualization. Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI Press, 2015).

- Rual J. F. et al. Towards a proteome-scale map of the human protein-protein interaction network. Nature 437, 1173 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.