Abstract

Ovarian cancer patients are generally diagnosed at FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) stage III/IV, when ascites is common. The volume of ascites correlates positively with the extent of metastasis and negatively with prognosis. Membrane GRP78, a stress-inducible endoplasmic reticulum chaperone that is also expressed on the plasma membrane (memGRP78) of aggressive cancer cells, plays a crucial role in the embryonic stem cell maintenance. We studied ascites effects on ovarian cancer stem-like cells using a syngeneic mouse model. Our study demonstrates that ascites-derived tumor cells from mice injected intraperitoneally with murine ovarian cancer cells (ID8) express increased memGRP78 levels compared to ID8 cells from normal culture. We hypothesized that these ascites associated memGRP78+ cells are cancer stem-like cells (CSC). Supporting this hypothesis, we show that memGRP78+ cells isolated from murine ascites exhibit increased sphere forming and tumor initiating abilities compared to memGRP78− cells. When the tumor microenvironment is recapitulated by adding ascites fluid to cell culture, ID8 cells express more memGRP78 and increased self-renewing ability compared to those cultured in medium alone. Moreover, compared to their counterparts cultured in normal medium, ID8 cells cultured in ascites, or isolated from ascites, show increased stem cell marker expression. Antibodies directed against the carboxy-terminal domain of GRP78: 1) reduce self-renewing ability of murine and human ovarian cancer cells pre-incubated with ascites and 2) suppress a GSK3α-AKT/SNAI1 signaling axis in these cells. Based on these data, we suggest that memGRP78 is a logical therapeutic target for late stage ovarian cancer.

Keywords: animal model of ovarian cancer, ascites, membrane GRP78, cancer stem-like cell, tumor initiating activity

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the most lethal gynecologic malignancy (1). 76% of ovarian cancer patients are diagnosed at stage III/IV, with a 5-year survival rate of 18%–45% (2). Ascites occurs in 17% of FIGO stage I/II ovarian cancer patients and 89% of patients at stage III/IV (3). Standard management of ovarian cancer consists of surgical staging, operative tumor debulking, and intravenous chemotherapy (2). While more than 80% of advanced stage patients benefit from first-line therapy, most patients suffer from recurrence within 18 months of diagnosis (4). This high relapse rate may result from failure of conventional therapy to remove cancer stem-like cells (CSCs) (5). CSCs are slow-cycling, therapy-resistant tumor cells capable of self-renewal. CSCs play a crucial role in tumor initiation and metastasis (6–8).

Glucose regulated protein 78 (GRP78) is a stress-inducible endoplasmic reticulum (ER) chaperone that is also expressed on the plasma membrane (memGRP78) of aggressive cancers (9, 10). GRP78 protects cells from stress by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway and inhibiting pro-apoptotic cascades. However, if the ER is severely stressed GRP78 can promote cell death. Two functional domains of GRP78 have been characterized: an amino-terminal domain that drives PI3K/AKT activity (11, 12), and a carboxy (COOH)-terminal domain that promotes apoptotic signaling (13, 14). Our previous work demonstrates that targeting GRP78 with mouse IgGs against the GRP78 COOH-terminal domain causes tumor cell apoptosis by activating the caspase pathway (13, 14), resulting in delayed tumor growth, and prolonged survival in a mouse melanoma model (15).

GRP78 maintains survival of embryonic (16) and adult mammary stem cells (17), and is highly expressed in hematopoietic stem cells (18). Overexpression of GRP78 correlates with malignant transformation in epithelial ovarian tumor cells (19), while inducible knockout of GRP78 in the hematopoietic system suppresses Pten-null leukemogenesis (20). MemGRP78 is associated with increased cancer stemness in head and neck cancer (21). Based on these findings, in addition to our laboratory’s studies of memGRP78 functions in cancer(11–15, 22), in the current work, we investigated functions for memGRP78 in in ovarian cancer stemness.

To test the hypothesis that memGRP78 is an ovarian CSC marker, we utilized a syngeneic, immunocompetent ovarian cancer model (23). We chose this model because GRP78 autoantibodies circulating in cancer patients activate memGRP78 (11, 12, 24). We now demonstrate that memGRP78 expression is increased in ovarian cancer cells isolated from ascites in vivo and ovarian cancer cells treated with ascites in vitro. We also show that memGRP78+ cells possess higher tumorigenic potential and stemness properties than memGRP78− cells. Neutralizing memGRP78 with anti-COOH terminal domain antibodies suppresses ovarian cancer cell sphere-forming ability. Our work is the first to demonstrate that memGRP78+ CSCs are enriched by ascites and that memGRP78 is a logical target for eliminating ovarian CSCs.

Material and Methods

Cell culture

ID8 cells (mouse epithelial ovarian cancer cell line obtained in 2006 from Dr. Kathy Roby, Kansas University Medical Center) were maintained in DMEM (high glucose, Gibco-Life Technologies; Carlsbad, CA) containing 4% fetal bovine serum, 1× penicillin streptomycin. Comparison of these cells to the original published ID8 cell line is described (Supplementary Fig. S1). ID8-GFP was a gift from Dr. Brent Berwin (Dartmouth Medical School; 2007). Both ID8 and ID8-GFP cells were shown to be mycoplasma-free (3/20/2010) and tested to be identical by STR DNA profiling (11/05/14). Human ovarian cancer cell lines [OvCar3 (1/20/14) and ES2 (6/6/13)] were purchased from Duke Cell Culture Facility (CCF) and cultured under ATCC recommended conditions. OvCar3 (12/06/13) and ES2 (06/20/09) cells were shown to be mycoplasma-free and authenticated using STR DNA profiling before being frozen by Duke CCF. 50% ascites treatment conditions were adjusted to normal culture conditions with regard to FBS and glucose concentrations.

Antibodies

Antibody sources were as follows: GRP78 N20 and C20 [Santa Cruz Biotech (Santa Cruz, CA)]; OCT4, SOX9 and GSK3 [Millipore (Temecula, CA)]; CD133 and SCA1 [Biolegend (San Diego, CA)]; SNAI1, p-GSK3, AKT and p-AKT [Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA)]. GRP78 C38 and C107 antibodies were produced in our laboratory (15).

Mouse studies

Animal experimentation was performed according to the regulations of the Duke Institutional Animal Care & Use Committee. ID8 cells were injected into the mouse peritoneum of female 6–8 week-old C57BL/6 mice (Charles River; Raleigh, NC). End points for euthanasia included lethargy, decreased motility, or cross-sectional abdominal diameter increase greater than 1/3.

Ascites

De-identified patient ascites samples (Ov476, Ov480) were obtained from informed subjects with FIGO stage IIIC grade 2 ovarian serous adenocarcinoma (Duke University IRB approved protocol Pro00013710). For murine ascites, mice were euthanized and peritoneal fluid was collected and centrifuged twice at 500×g for 5 minutes to separate cellular and acellular fractions. Acellular fractions from multiple mice were pooled and filtered through 0.22 µm sterile filters.

Microarray analysis

Total RNA was isolated (Qiagen RNeasy® Micro kit, Valencia, CA) according to manufacturer's protocol and analyzed by Mouse Genome 430 2.0 Array (Affymetrix; Santa Clara, CA) (GEO accession number GSE61285). Array data were then normalized by Robust Multiarray Averaging (RMA) for further analysis. RMA is a normalization procedure for microarrays that background corrects, normalizes and summarizes the probe level information from the Affymetrix microarray data. To identify differentially expressed genes, we applied SAM 4.01 Excel Add-In (25) that provides the estimate of False Discovery Rate (FDR) for multiple testing. Using the FDR threshold of 2.5%, we identified 1257 probesets whose expression values were extracted, mean-centered and clustered by Cluster 3.0 and viewed by Treeview v1.6 (26). These selected genes (Supplemental table 1) were then deposited into Gather (gather.genome.duke) (27) to determine the enrichment for the Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG (KEGG). For the stemness score, the mean expression level of 38 stemness-related genes was calculated as “stemness score” in a multi-gene signature approach (28, 29) and compared by t-test to avoid quantitative bias from any single gene.

Flow cytometric analysis

ID8 cells (95% confluence) were harvested using dissociation buffer (Gibco). C20 was used for memGRP78 staining. 7-AAD (BD Biosciences) was used to exclude dead cells. Cells were fixed and permeabilized using Cytofix/Cytoperm™ Kit (BD Biosciences) before OCT4 staining. Antibody binding was assessed using a Guava Easycyte Plus flow cytometer (Millipore).

Cell sorting

Red blood cells were removed from the cellular fraction of murine ascites using RBC lysis buffer (BD Biosciences). Remaining cells were prepared with Fc block and anti-CD11b antibody coated magnetic beads (558013, BD Biosciences) and macrophages were removed with a BD magnet. The remaining sample was stained with F4/80, 7AAD, and GRP78 N20 and sorted by Duke Cancer Institute Flow Cytometry Shared Resource to select for the F4/80−, 7AAD− and memGRP78+ or F4/80−, 7AAD− and memGRP78− populations.

Sphere formation assay

Single cell suspensions were plated in 24-well ultralow attachment plates (Corning, NY) at 6 × 103 cells/well (ID8 and OvCar3) and 1 × 103 cells/well (ES2) in primary assay. Cells were grown in serum-free DMEM supplemented with 1% methyl cellulose (Sigma-Aldrich), B27 (Invitrogen), 20 ng/mL EGF, 20 ng/ mL bFGF (BD Biosciences), and 4 µg/ml bovine insulin (Invitrogen). Spheres were cultured for 7–14 days, after which all spheres (diameter >50 µm) were counted in the well. For serial passages, spheres were dissociated to single cells with trypsin, and 6 × 103 cells plated and cultured in ultra-low attachment plates for 14 days.

DiD retention

ID8 cells were labeled with DiD dye (Life Technologies) using the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were split into two groups beinh cultured in either medium or 50% acellular ascites. DiD intensity was measured on day 7. Similar experiments were performed with DiO, Dil (Life Technologies) and Cyto-ID Red (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY).

Statistical analysis

Prism (version 5.0; GraphPad Software) was used to perform statistical analyses. Two-tailed Student t test was used to test differences in sample means for data with normally distributed means. Chi squared test was used to evaluate the survival difference in animal studies. Likelihood ratio test of single-hit model was performed as a standard statistical analysis method for limiting dilution studies. p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Acellular ascites increases ovarian cancer cell stemness

A syngeneic mouse model was established by injecting murine epithelial ovarian cancer cells (ID8 cells) intraperitoneally into C57BL/6 mice. We observed a strong linear regression correlation between the volume of ascites and tumor burden (R2=0.49) (Supplementary Fig. S2.A). Mice had shortened survival when injected with ID8 cells isolated from ascites or with ID8 cells plus ascites supernatant from ID8 tumor-bearing mice as compared to mice receiving ID8 cells from normal culture (Supplementary Fig. S2.B). These results indicate that acellular ascites derived from ID8 tumor-bearing mice is capable of driving ovarian cancer progression.

We next tested the effect of ascites on ID8 cell self-renewing ability. Equal numbers of ID8 cells from normal culture, ID8 cells isolated from ascites, or ID8 cells pre-treated with ascites for 7 days were seeded into sphere culture. Increasing concentrations of ascites were associated with enhanced sphere forming ability (Supplementary Fig. S3.A–B). We chose 50% ascites for further studies because it effectively increased memGRP78 expression and sphere-forming ability of these cells. For all conditions, glucose and FBS concentration was normalized to that of control medium.

ID8 cells isolated from ascites and ascites pre-treated ID8 cells exhibited increased sphere-forming ability compared to ID8 cells in regular medium (Fig. 1.A). Of note, our sphere assay includes methylcellulose to avoid nonspecific cell aggregation (30). As shown in Fig. 1.A, primary spheres, when dissociated, efficiently established secondary spheres, thus displaying CSC behaviors. Protein concentration was normalized with albumin as a control for the 50% ascites treatment and no significant difference from normal cell culture was detected (Supplementary Fig. S3.C).

Figure 1. Ascites enriches for CSCs.

A. ID8 cells were cultured for the indicated times in medium or 50% acellular ascites from ID8 bearing mice. 6×103 cells/well were seeded in a primary sphere assay, and then harvested, trypsinized and passaged to form secondary spheres. Y axis represents spheres ≥ 50µm +/− SD. B. Competition between ascites pre-treated and untreated ID8-GFP cells in sphere formation. Left: ID8-GFP cells were pre-treated with acellular ascites derived from tumor-bearing mice for 7 days and then mixed 1:1 with untreated ID8 cells. The mixture was seeded into a sphere assay (primary spheres). On day 7, primary spheres were trypsinized and seeded into a sphere assay (secondary spheres). Pictures were taken from 5 random fields. A representative field is shown for primary spheres at 2.5×, secondary spheres at 2.5×, primary spheres at 20× and secondary spheres at 20×. Right: Quantification of % ID8-GFP and ID8 cells in 5 fields at 20× magnification from primary and secondary sphere assays. Red arrows indicate GFP+ spheres and white arrows indicate GFP-spheres. C. Culturing in vivo ascites cells in vitro for 7 days (re-cultured) (left panel) or re-culturing ID8 cells pre-treated with ascites for 7 days (ascites treated 7 days) in culture for 9 days (ascites off 9 days) (right panel) decreases their sphere-forming ability. Error bars represent SD from 3 trials in triplicate. D. After 7 day ascites treatment, 34.5% of ID8 cells became Annexin V positive, while 7.7% ID8 cells were positive in normal culture. E. ID8 cells were labeled with DiD on day 0 and split into two groups, receiving either medium or 50% ascites for 7 days. The majority of ascites treated ID8 cells maintained DiD label on day 7, while most ID8 cells in medium lost the dye. F–G. OvCar3 or ES2 cells were pre-treated with 50% ascites from either of two ovarian cancer patients (Ov476, Ov480) for 7 days and sphere number was counted. Error bars represent SD from 3 different trials in triplicate for this figure.

To confirm that ascites increases sphere-forming ability of ovarian cancer cells, we employed a competition strategy between ascites pre-treated and untreated cells. ID8-GFP cells, which share the same proliferation rate as ID8 cells (data not shown), were pre-treated with acellular ascites for 7 days and then mixed 1:1 with untreated ID8 cells. The cell mixture was seeded into a sphere assay. Serial passage of primary sphere cells into a secondary sphere assay was also performed. Pictures were taken from 5 different fields (Fig. 1.B. left panel) and the percentages of ID8-GFP and ID8 cells from sphere assays were quantified. As shown in Fig. 1.B, spheres are composed mostly of ascites pre-treated ID8-GFP cells.

To test whether increased sphere-forming ability was reversible by removing ascites, we re-cultured ID8 cells isolated from ascites in ascites-free medium or removed ascites from ascites treated ID8 cells. In both situations sphere-forming ability of ID8 cells was decreased significantly (Fig. 1.C).

Increased sphere-forming ability of ascites pre-treated ID8 cells could reflect either ascites stimulation of CSC signaling or ascites enrichment of a stem cell population. To differentiate between these possibilities we included ID8 cells exposed to acellular ascites for 4 hours, a short incubation promoting signaling but not sufficient for enrichment of a tumor cell sub-population. Sphere-forming ability of ID8 cells exposed to ascites for 4 hours was similar to that of untreated ID8 cells (Fig. 1.A), supporting the enrichment hypothesis. After 7 days ascites treatment, 34.5% ID8 ovarian cancer cells were Annexin V positive compared to 7.7% ID8 cells in normal medium (Fig. 1.D). Collectively, our findings suggest that ID8 ovarian cancer cells are heterogeneous. While bulk tumor cells do not survive in an ascites microenvironment, a sub-population of cells with cancer stem-like behavior survives ascites exposure.

To provide further evidence for ascites enrichment of a slow-cycling CSC population, we labeled ID8 cells with a lipophilic tracer (DiD) that is diluted in proliferating cells, but maintained in non-proliferating/slow-proliferating cells. We detected 0% DiD+ cells in ID8 cells cultured for 7 days in normal medium. In contrast, 66.7% of cells treated with 50% acellular ascites for 7 days were DiD+ (Fig. 1.E). Similar results were observed using 3 other lipophilic dyes (data not shown).

To begin to validate our findings in human ovarian cancer, human ovarian cancer cell lines were pre-incubated with either of two patient ascites samples. Notably, these human ascites samples increased sphere-forming ability of both human ovarian cancer lines compared to untreated cells (Fig. 1.F–G.).

Microarray analysis of stemness-related genes in ascites treated ID8 cells

We performed microarray analysis on untreated and ascites-pretreated ID8 cells (Fig. 2.A). Gene expression profiles were interrogated with Affymetrix mouse 430A2 arrays (GEO accession number GSE61285) and normalized by RMA. To identify differentially expressed genes while considering FDR, we used SAM (25) to identify 1257 probesets (707 induced and 550 repressed, Supplemental Table 1) with 2.5% of FDR. Expression of these genes was extracted, mean-centered and clustered to generate the overview heatmap (Fig 2A). GO and KEGG enrichments of these selected genes were performed (GEO accession number GSE61285).

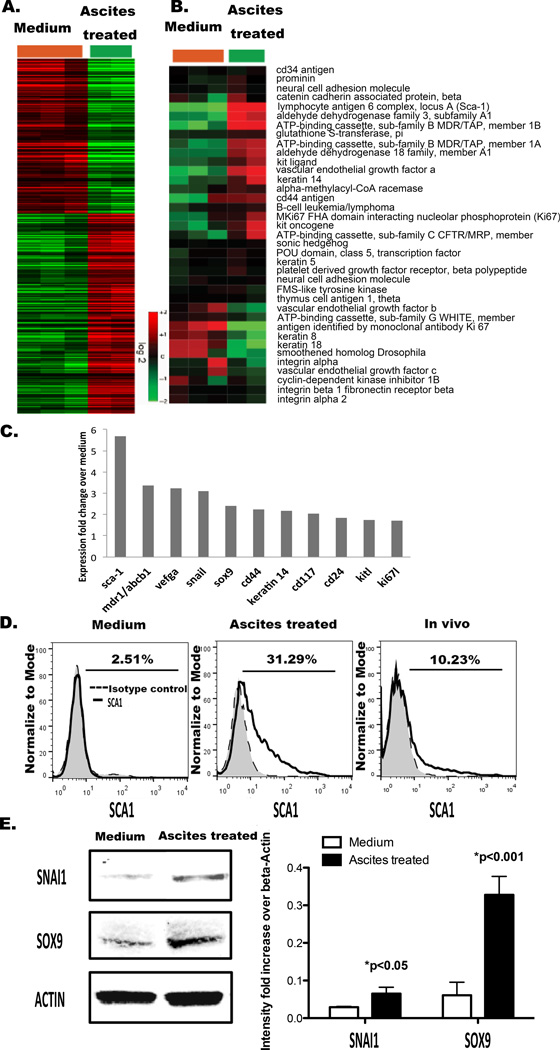

Figure 2. Incubating murine ovarian cancer cells with ascites increases stemness gene expression.

A. Hierarchy cluster of 1257 probesets identified by SAM to be differentially expressed between ID8 cells (n=3) and ascites treated ID8 cells (n=2). The heatmap showed the mean-centered expression values of the selected genes (red: induced, green: repressed) B. Expression levels of 38 stemness-associated genes were extracted, mean-centered and arranged by hierarchical clustering (Supplementary Table 2). C. Stemness associated genes significantly upregulated after ascites pretreatment of tumor cells for 7 days. D. SCA1 expression on ID8 cells, ID8 cells treated with ascites for 7 days and ID8 cells from ascites. Representative of 3 different experiments. E. Western blotting for SNAI1 and SOX9 in ID8 cells and ID8 cells treated with ascites for 7 days. Quantification was by densitometry. Error bars represent SD from 3 trials in triplicate.

We next investigated how ascites treatment of ovarian cancer cells affected expression of 38 genes that was previously reported to associate with cancer stemness (31). To avoid the bias of any individual stem-related gene, we took a multi-gene “signature” approach that provides a quantitative measurement of the “stemness” of each sample (31–32). When the mean expression values of all 38 genes were calculated as a “stemness-score”, ascites-treated samples had a significantly higher stemness-score than control cells (Fig. 2.B; Supplementary Table 2). The expression of 11 stemness genes (Sca-1/Ly6a, Abcb1a/b, Vegfa, Snai1, Sox9, Krt14, Cd44, Kit, Cd24, Kitl, and Ki67l) was upregulated by ascites (Fig. 2.C). Sca-1 (Ly6a), stem cell antigen-1, is a murine CSC marker (32, 33). Snai1 contributes to a stem-like phenotype in ovarian cancer (34–36). Sox9 converts differentiated breast cancer cells to CSCs (36).

To show that these stemness genes were upregulated at the protein level in ascites-treated ovarian cancer cells, we next performed flow cytometry and western blotting (Fig. 2.C). By flow cytometry, we detected increased SCA1 expression in ascites treated ID8 cells, as well as in ID8 cells harvested from ascites in vivo compared to that in control ID8 cells (Fig. 2.D). Compared to normal culture, ascites treatment also increased expression of SNAI1 and SOX9 significantly (Fig. 2.E).

MemGRP78 expression in ascites-associated ovarian cancer cells

We next studied ascites effects on memGRP78 expression. MemGRP78 levels were significantly higher in ID8 cells isolated from ascites compared to that in ID8 cells cultured in normal medium (Fig. 3. upper panel). When in vivo cells were cultured in normal medium for 7 days, the memGRP78 level shifted back to parental cell levels, leading us to hypothesize that survival of a memGRP78-expressing ovarian cancer cell subpopulation is supported by soluble ascites factors. To test this hypothesis we cultured ID8 cells with acellular ascites for 7 days and found that the % memGRP78 + cells increased significantly from 7.5% (parental) to 43.2% (ascites 7 days), almost reaching the level of in vivo tumor cells (Fig. 3. bottom panel). Removal of ascites from these cells for 9 days restored memGRP78 + expression to baseline levels (ascites off 9 days). Notably, memGRP78 levels remained at baseline following short-term ascites exposure (Fig. 3. bottom panel). The reversibility in memGRP78 induction by ascites correlates with the reversibility of ascites enhanced sphere-forming ability of ID8 cells (Fig. 1.C), supporting the hypothesis that memGRP78 is an ovarian CSC marker.

Figure 3. Ascites increases memGRP78 expression on ID8 cells.

MemGRP78 expression was assessed by flow cytometry using C20 antibody. Top panel: % memGRP78 + cells minus background in ID8 cells (parental), ID8 cells freshly isolated from murine ascites (In vivo), and ID8 cells isolated from ascites after being recultured in normal medium for 7 days (recultured) are shown. Bottom panel: ID8 cells were incubated with 50% ascites for 4 hours or 7 days. Ascites was removed and cells were recultured in normal medium for 9 days (Ascites off 9 days).

MemGRP78 is associated with stemness

To further test whether memGRP78 is a stem cell marker in murine ovarian cancer cells, we sorted ascites-derived tumor cells into memGRP78 + and – populations and characterized their self-renewing activity in a sphere assay. 7AAD+ dead cells and F4/80+ macrophages were excluded and the gate for memGRP78+ and – was set at the extreme ends to insure purity (37) (Fig. 4.A). Although memGRP78+ cells proliferated slower than memGRP78− cells and unsorted tumor cells (Supplementary Fig. S4), memGRP78 + cells formed more spheres than memGRP78− cells (Fig. 4.B). These studies suggest that memGRP78+ ovarian cancer cells are similar to CSCs, which are characterized by their slow-cycling cells capable of sphere formation (6–8).

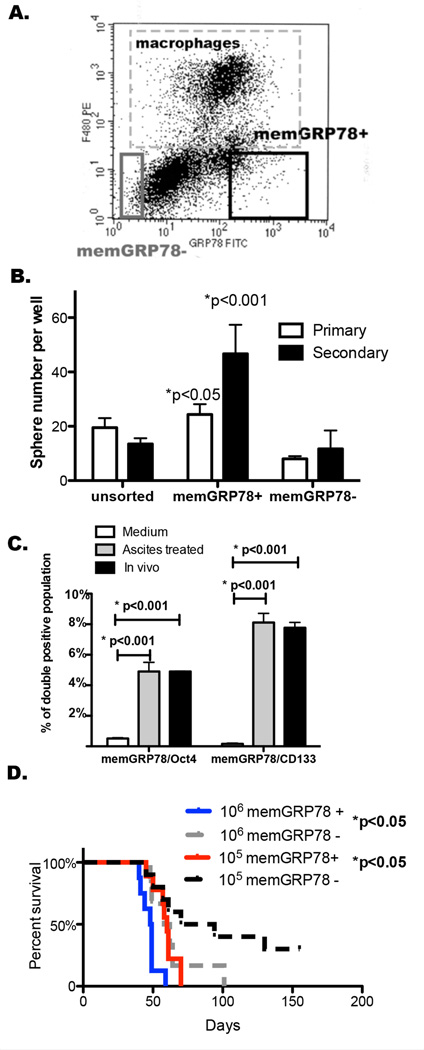

Figure 4. MemGRP78+ cells exhibit increased sphere-forming ability/tumor initiating activity compared to memGRP78− cells.

A. Gating for memGRP78 +/− cells from ascites cells generated in ID8 cell bearing mice. B. Sphere-forming ability of memGRP78 + and memGRP78 – gated tumor cells. 103 cells/well were seeded in a sphere assay. Primary spheres were trypsinized and passaged to form secondary spheres. Y axis represents spheres ≥ 50µm +/− SD. Similar results were obtained in 3 experiments. C. Bar graph showing the double positive population for GRP78 and OCT4 or CD133 (n=2). D. Survival of mice injected with 106 or 105 memGRP78+ tumor cell was shortened compared to that of memGRP78− tumor cells (n=10). Log-rank test was performed between memGRP78+ and – groups at either cell number trial.

We then performed double staining of memGRP78 and two stem cell markers {Octamer-binding transcription factor 4 (OCT4) (38) and CD133 (Prom1) (39)}. Acellular ascites treatment for 7 days increased the OCT4/memGRP78 and CD133/memGRP78 double positive populations. ID8 cells isolated from ascites had 4.9% memGRP78+/OCT4+ cells (Fig. 4.C) and 7.8% CD133+/memGRP78+ cells (Fig. 4.C).

Limiting dilution transplantation assay is a standard method for assessing tumor-initiating activity associated with cancer stemness. We investigated the ability of memGRP78+ and memGRP78− cells to initiate tumor growth when injected at cell numbers ranging from 103 to 106. More mice developed tumors or tumor associated ascites in memGRP78+ cells injected groups than those injected with memGRP78− cells at 103 to 105 injection numbers (Table 1). Likelihood ratio test of single-hit model was performed as a standard statistical analysis method for limiting dilution studies of stem cells (40) and detected p<0.05 between memGRP78+ vs memGRP78− cells. Moreover, mice bearing 106 and 105 memGRP78+ cells died sooner than those bearing memGRP78− cells (Fig. 4.D).

Table 1.

MemGRP78+ or memGRP78− tumor cells were sorted from ascites generated in ID8 cell bearing mice. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 103 to 106 of these sorted cell populations, and tumor take rate was determined. Likelihood ratio test of single-hit model was performed and showed p<0.05.

| memGRP78 positive | memGRP78 negative | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell # injected | Tumor detected | Tumor take rate | Tumor detected | Tumor take rate |

| 106 | 9/9 | 100% | 6/6 | 100% |

| 105 | 10/10 | 100% | 7/10 | 70% |

| 104 | 7/10 | 70% | 5/10 | 50% |

| 103 | 2/10 | 20% | 0/10 | 0 |

GRP78 antibodies suppress sphere formation

Monoclonal antibodies developed by our laboratory (C38, C107), and a commercial antibody (C20) directed against the COOH-terminal domain of GRP78 suppress tumor growth in melanoma and prostate models (13, 15). We studied effects of these antibodies on ovarian cancer cells. ID8 cells were treated for 7 days with 50% acellular ascites. Antibodies (C38, C107, isotype control at 10 µg/ml; C20 or goat IgG at 5 µg/ml) were added on day 5. On day 7 each group was harvested and sphere-forming ability was determined. Ascites treatment significantly increased sphere number. Notably, C38 and C20 antibodies, but not C107, decreased sphere numbers (Fig. 5.A).

Figure 5. GRP78 antibodies suppress ovarian cancer sphere forming ability and prolong mouse survival in a syngeneic model of ovarian cancer.

A. ID8 cells were pre-treated with ascites obtained from ID8 bearing mice for 7 days plus 10µg/ml C38, mouse isotype control (IgG2b), 5µg/ml C20 or goat IgG for 2 days. Y axis represents spheres ≥ 50µm. Error bars represent SD from 3 trials in triplicate. B. Mouse study was performed on 4 groups of mice (n=10/group) receiving C38, C107, IgG2b control or PBS. We injected 400µg antibody or PBS per mouse 5 days before implanting 105 ID8 cells isolated from ascites. Following implantation, 200µg antibody or 200µl PBS were delivered intraperitoneally every other week until the endpoint. C. C20 or goat IgG was added to ID8 cells from medium or 7-day ascites pre-treatment conditions. After 2 days, cells were lysed and extracts probed for phospho-AKT, phospho-GSK3, and SNAI1 by western blotting. A representative blot is shown. D. Densitometry of three independent experiments (western blotting). E–F. OvCar3 or ES2 cells were incubated with Ov480 ascites for 7 days plus 10µg/ml C38, C107, mouse isotype control (IgG2b), 5µg/ml C20 or goat IgG for 2 days. Y axis represents spheres ≥ 50µm. Error bars represent SD from 3 trials in triplicate.

To test antibody activity in vivo, 400µg antibody per mouse was injected intraperitoneally 5 days before implanting 105 ascites tumor cells. Following implantation, 200µg antibody was delivered intraperitoneally every other week until the endpoint. Mice receiving C38 or C107 antibodies had significantly lengthened survival (C38 median=64 days, C107 median=64 days) compared to those receiving IgG2b (median=55 days) (Fig. 5.B).

We next investigated signaling pathways associated with memGRP78-expressing ovarian CSCs. Ascites treatment of ID8 cells significantly increased AKT and GSK3α phosphorylation (Fig. 5.C), and GSK3α phosphorylation/inactivation led to increased SNAI1 levels (41, 42), associated with enhanced CSC behaviors (35, 43). Notably, C20 blocked these signaling events by binding to memGRP78 (Fig. 5.C and D) (13, 14). These data suggest that a memGRP78-AKT-GSK3-SNAI1 signaling axis is associated with stemness of ascites-derived murine ovarian cancer cells.

To begin to validate our findings in human ovarian cancer cell lines, we incubated OvCar3 or ES2 cells with acellular human ascites and treated them with either C38, C107, C20 or isotype control IgG. C38, C107 and C20 suppressed sphere-forming ability of ascites pre-treated OvCar3 and ES2 cells (Fig. 5.E–F).

Discussion

We demonstrate that treatment of murine ovarian cancer cells with acellular ascites enriches for memGRP78 + cells with CSC properties. We also show an ability of human ascites to enrich for human ovarian CSC in vitro. Further studies are needed to show that ascites enriches for a CSC population relevant to human ovarian cancer disease. Collectively, our findings raise the important question of whether blocking the occurrence of ascites and/or clinical removal of ascites may be a useful adjuvant to other ovarian cancer therapies.

We are currently investigating which ascites soluble factor(s) maintain ovarian CSCs. GRP78 ligands are potential candidates. We identified in murine ascites several GRP78 ligands [anti-GRP78 antibodies, alpha-2-macroglobulin (α2M) and murinoglobulin] that activate the amino terminal domain of GRP78 (11) (Supplementary Fig. S5). Further studies are needed to determine the importance of these ascites factors in the maintenance of ascites-enriched ovarian CSC.

GRP78 is generally associated with pro-proliferative activities (11, 12). However, CSCs are slow-cycling cells (6, 7). Although forming tumors faster in vivo, memGRP78+ cells have a slower proliferation rate than memGRP78− cells (Supplementary Fig. S4). Interestingly, the DiD retention study showed that most of the ascites pre-treated ID8 cells were slow-cycling cells (Fig. 1.E), correlating with the finding that memGRP78+ ovarian cancer cells are slowly proliferating.

Our studies show that memGRP78+ murine ovarian cancer cells exhibit increased tumorigenicity compared to memGRP78− cells (Table 1). These results confirm similar findings in head and neck cancer (21), but differ from a study showing that GRP78+ colon cancer cells exhibit reduced tumorigenicity compared to GRP78− cells (44). We attribute differences between these studies to the fact that our work, but not the study of Hardy et al, excluded dead cells during sorting. Dead cells expose their endoplasmic reticulum, which is a major source of GRP78. The findings of Hardy et al. are likely complicated by their inclusion of a large percentage of dead GRP78+ cells in their tumor injection study.

Cancer stem cells are a heterogeneous population consisting of cells in different differentiation stages, each stage expressing distinct CSC markers (45). The difference in % SCA1+ cells found in vivo versus in vitro likely reflects the fact that: 1) SCA1 is expressed only during specific CSC differentiation stages and 2) this SCA1-expressing stem cell sub-population is represented more frequently in our in vitro ascites enrichment model than in the in vivo model. This phenomenon may be attributable to microenvironmental regulation of CSC differentiation state. In contrast, memGRP78 is expressed equally on cancer cells from our in vitro model and from ascites cells in vivo, suggesting that memGRP78 is a universal murine CSC marker.

We demonstrated that ascites increased cancer stem cell markers (SOX9 and SNAI1) in ID8 cells (Fig. 2.D). Activation of GSK3, a differentiation related gene that is inactivated by AKT (46), reduces Snai-1 mRNA and SNAI1 protein levels (41, 42). Antibodies against the COOH-terminal GRP78 domain blocked AKT and GSK3α phosphorylation, thus reducing SNAI1 expression level and stem-cell activities. These data demonstrate efficacy of these GRP78 antibodies in reducing CSC markers in murine ovarian cancer cells.

Our in vivo study, showing that a GRP78 COOH terminal domain antibody (C38) prolonged survival of ovarian cancer bearing mice, indicates a potential clinical application of targeting memGRP78. Although C107 only showed a modest effect on sphere formation in vitro (Fig. 5.A), mice receiving this antibody survived longer than control mice. This finding may be attributable to different conformations of memGRP78 on tumor cells in vitro vs in vivo, with the epitope for C107 being more accessible in vivo. We believe that efficacy of GRP78 antibodies will be increased when combined with chemotherapy. According to our model, chemotherapy should target the fast proliferating tumor bulk cells whereas anti-COOH terminal domain GRP78 antibodies will target CSCs. Combination studies are currently under investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

No financial support was received for these studies.

We thank the Duke Microarray Core facility for technical support and the generation of microarray data. The authors also thank Dr. Xiao-fan Wang, Dr. Gustaaf de Ridder, Dr. Rupa Ray, and Sturgis Payne for providing comments.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest: N/A.

References

- 1. Cancer.org [Internet] Atlanta: American Cancer Society, Inc; c1913 [updated 2014 August 11;cited 2014 September 19]. Available from: http://www.cancer.org/cancer/ovariancancer/detailedguide/ovarian-cancer-key-statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hennessy BT, Coleman RL, Markman M. Ovarian cancer. Lancet. 2009;374:1371–1382. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61338-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burges A, Wimberger P, Kumper C, Gorbounova V, Sommer H, Schmalfeldt B, et al. Effective relief of malignant ascites in patients with advanced ovarian cancer by a trifunctional anti-EpCAM x anti-CD3 antibody: a phase I/II study. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2007;13:3899–3905. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jayson GC, Kohn EC, Kitchener HC, Ledermann JA. Ovarian cancer. Lancet. 2014;384:1376–1388. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwon MJ, Shin YK. Regulation of ovarian cancer stem cells or tumor-initiating cells. International journal of molecular sciences. 2013;14:6624–6648. doi: 10.3390/ijms14046624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moore N, Lyle S. Quiescent, slow-cycling stem cell populations in cancer: a review of the evidence and discussion of significance. Journal of oncology. 2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/396076. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li L, Bhatia R. Stem cell quiescence. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2011;17:4936–4941. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee AS. GRP78 induction in cancer: therapeutic and prognostic implications. Cancer research. 2007;67:3496–3499. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Defresne F, Bouzin C, Guilbaud C, Dieu M, Delaive E, Michiels C, et al. Differential influence of anticancer treatments and angiogenesis on the seric titer of autoantibody used as tumor and metastasis biomarker. Neoplasia. 2010;12:562–570. doi: 10.1593/neo.10238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quinones QJ, de Ridder GG, Pizzo SV. GRP78: a chaperone with diverse roles beyond the endoplasmic reticulum. Histology and histopathology. 2008;23:1409–1416. doi: 10.14670/HH-23.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Misra UK, Deedwania R, Pizzo SV. Activation and cross-talk between Akt, NF-kappaB, and unfolded protein response signaling in 1-LN prostate cancer cells consequent to ligation of cell surface-associated GRP78. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:13694–13707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511694200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Misra UK, Mowery Y, Kaczowka S, Pizzo SV. Ligation of cancer cell surface GRP78 with antibodies directed against its COOH-terminal domain up-regulates p53 activity and promotes apoptosis. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2009;8:1350–1362. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Misra UK, Pizzo SV. Ligation of cell surface GRP78 with antibody directed against the COOH-terminal domain of GRP78 suppresses Ras/MAPK and PI 3-kinase/AKT signaling while promoting caspase activation in human prostate cancer cells. Cancer biology & therapy. 2010;9:142–152. doi: 10.4161/cbt.9.2.10422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Ridder GG, Ray R, Pizzo SV. A murine monoclonal antibody directed against the carboxyl-terminal domain of GRP78 suppresses melanoma growth in mice. Melanoma research. 2012;22:225–235. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e32835312fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo S, Mao C, Lee B, Lee AS. GRP78/BiP is required for cell proliferation and protecting the inner cell mass from apoptosis during early mouse embryonic development. Molecular and cellular biology. 2006;26:5688–5697. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00779-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spike BT, Kelber JA, Booker E, Kalathur M, Rodewald R, Lipianskaya J, et al. CRIPTO/GRP78 signaling maintains fetal and adult mammary stem cells ex vivo. Stem cell reports. 2014;2:427–439. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wey S, Luo B, Lee AS. Acute inducible ablation of GRP78 reveals its role in hematopoietic stem cell survival, lymphogenesis and regulation of stress signaling. PloS one. 2012;7:e39047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang LW, Lin CY, Lee CC, Liu TZ, Jeng CJ. Overexpression of GRP78 is associated with malignant transformation in epithelial ovarian tumors. Applied immunohistochemistry & molecular morphology : AIMM / official publication of the Society for Applied Immunohistochemistry. 2012;20:381–385. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e3182434113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wey S, Luo B, Tseng CC, Ni M, Zhou H, Fu Y, et al. Inducible knockout of GRP78/BiP in the hematopoietic system suppresses Pten-null leukemogenesis and AKT oncogenic signaling. Blood. 2012;119:817–825. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-357384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu MJ, Jan CI, Tsay YG, Yu YH, Huang CY, Lin SC, et al. Elimination of head and neck cancer initiating cells through targeting glucose regulated protein78 signaling. Molecular cancer. 2010;9:283. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Ridder GG, Gonzalez-Gronow M, Ray R, Pizzo SV. Autoantibodies against cell surface GRP78 promote tumor growth in a murine model of melanoma. Melanoma research. 2011;21:35–43. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e3283426805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roby KF, Taylor CC, Sweetwood JP, Cheng Y, Pace JL, Tawfik O, et al. Development of a syngeneic mouse model for events related to ovarian cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:585–591. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.4.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arap MA, Lahdenranta J, Mintz PJ, Hajitou A, Sarkis AS, Arap W, et al. Cell surface expression of the stress response chaperone GRP78 enables tumor targeting by circulating ligands. Cancer cell. 2004;6:275–284. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:5116–5121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang X, Lucas JE, Chen JL, LaMonte G, Wu J, Wang MC, et al. Functional interaction between responses to lactic acidosis and hypoxia regulates genomic transcriptional outputs. Cancer research. 2012;72:491–502. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang JT, Nevins JR. GATHER: a systems approach to interpreting genomic signatures. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2926–2933. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chi JT, Wang Z, Nuyten DS, Rodriguez EH, Schaner ME, Salim A, et al. Gene expression programs in response to hypoxia: cell type specificity and prognostic significance in human cancers. PLoS medicine. 2006;3:e47. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen JL, Merl D, Peterson CW, Wu J, Liu PY, Yin H, et al. Lactic acidosis triggers starvation response with paradoxical induction of TXNIP through MondoA. PLoS genetics. 2010;6:e1001093. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jensen JB, Parmar M. Strengths and limitations of the neurosphere culture system. Molecular neurobiology. 2006;34:153–161. doi: 10.1385/MN:34:3:153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klonisch T, Wiechec E, Hombach-Klonisch S, Ande SR, Wesselborg S, Schulze-Osthoff K, et al. Cancer stem cell markers in common cancers - therapeutic implications. Trends in molecular medicine. 2008;14:450–460. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xin L, Lawson DA, Witte ON. The Sca-1 cell surface marker enriches for a prostate-regenerating cell subpopulation that can initiate prostate tumorigenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:6942–6947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502320102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grange C, Lanzardo S, Cavallo F, Camussi G, Bussolati B. Sca-1 identifies the tumor-initiating cells in mammary tumors of BALB-neuT transgenic mice. Neoplasia. 2008;10:1433–1443. doi: 10.1593/neo.08902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mani SA, Guo W, Liao MJ, Eaton EN, Ayyanan A, Zhou AY, et al. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell. 2008;133:704–715. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kurrey NK, Jalgaonkar SP, Joglekar AV, Ghanate AD, Chaskar PD, Doiphode RY, et al. Snail and slug mediate radioresistance and chemoresistance by antagonizing p53-mediated apoptosis and acquiring a stem-like phenotype in ovarian cancer cells. Stem cells. 2009;27:2059–2068. doi: 10.1002/stem.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guo W, Keckesova Z, Donaher JL, Shibue T, Tischler V, Reinhardt F, et al. Slug and Sox9 cooperatively determine the mammary stem cell state. Cell. 2012;148:1015–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raha D, Wilson TR, Peng J, Peterson D, Yue P, Evangelista M, et al. The cancer stem cell marker aldehyde dehydrogenase is required to maintain a drug-tolerant tumor cell subpopulation. Cancer research. 2014;74:3579–3590. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peng S, Maihle NJ, Huang Y. Pluripotency factors Lin28 and Oct4 identify a sub-population of stem cell-like cells in ovarian cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:2153–2159. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baba T, Convery PA, Matsumura N, Whitaker RS, Kondoh E, Perry T, et al. Epigenetic regulation of CD133 and tumorigenicity of CD133+ ovarian cancer cells. Oncogene. 2009;28:209–218. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu Y, Smyth GK. ELDA: extreme limiting dilution analysis for comparing depleted and enriched populations in stem cell and other assays. Journal of immunological methods. 2009;347:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bachelder RE, Yoon SO, Franci C, de Herreros AG, Mercurio AM. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 is an endogenous inhibitor of Snail transcription: implications for the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. The Journal of cell biology. 2005;168:29–33. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou BP, Deng J, Xia W, Xu J, Li YM, Gunduz M, et al. Dual regulation of Snail by GSK-3beta-mediated phosphorylation in control of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nature cell biology. 2004;6:931–940. doi: 10.1038/ncb1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fan F, Samuel S, Evans KW, Lu J, Xia L, Zhou Y, et al. Overexpression of snail induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and a cancer stem cell-like phenotype in human colorectal cancer cells. Cancer medicine. 2012;1:5–16. doi: 10.1002/cam4.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hardy B, Raiter A, Yakimov M, Vilkin A, Niv Y. Colon cancer cells expressing cell surface GRP78 as a marker for reduced tumorigenicity. Cellular oncology. 2012;35:345–354. doi: 10.1007/s13402-012-0094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang DG. Understanding cancer stem cell heterogeneity and plasticity. Cell research. 2012;22:457–472. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Force T, Woodgett JR. Unique and overlapping functions of GSK-3 isoforms in cell differentiation and proliferation and cardiovascular development. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:9643–9647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800077200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.