Abstract

Selenocysteine (Sec) is translated from the codon UGA, typically a termination signal. Codon duality extends the genetic code; coexistence of two competing UGA-decoding mechanisms, however, immediately compromises proteome fidelity. Selenium availability tunes reassignment of UGA to Sec. We report a CRL2 ubiquitin ligase-mediated protein quality control system that specifically eliminates truncated proteins consequent of reassignment failures. Exposing the peptide immediately N-terminal to Sec, a CRL2 recognition degron, promotes protein degradation. Sec incorporation destroys the degron, protecting read-through proteins from detection by CRL2. Our findings reveal a coupling between directed translation termination and proteolysis-assisted protein quality control, as well as a cellular strategy to cope with fluctuations in organismal selenium intake.

The canonical genetic code includes 20 amino acids. Additionally, selenocysteine (Sec/U) and pyrrolysine (Pyl/O) are the 21st and 22nd amino acids and coded by the otherwise termination codons UGA and UAG, respectively (1, 2). Sec is co-translationally incorporated into selenoproteins, a distinct set of proteins largely functioning as oxidoreductases with Sec in the active sites (3–5). At least 25 selenoproteins have been identified in humans (6). Translating UGA into Sec requires a Sec insertion sequence (SECIS) element in the 3’ untranslated region (3’UTR) of mRNA transcripts, Sec-tRNA, Sec-specific elongation factor (eEFSec), and the SECIS-binding protein SBP2 (7–10). This renders UGA/Sec redefinition failure prone, facing competition between Sec-tRNA and the release factor for UGA decoding (11). The reassignment efficiency is greatly influenced by dietary selenium (12). Stop codon reprograming expands the genetic code at the risk of introducing premature translational termination due to missed stop codon reassignment. Cells process potentially detrimental truncated proteins produced from failed UGA to Sec translation via previously undetermined mechanisms.

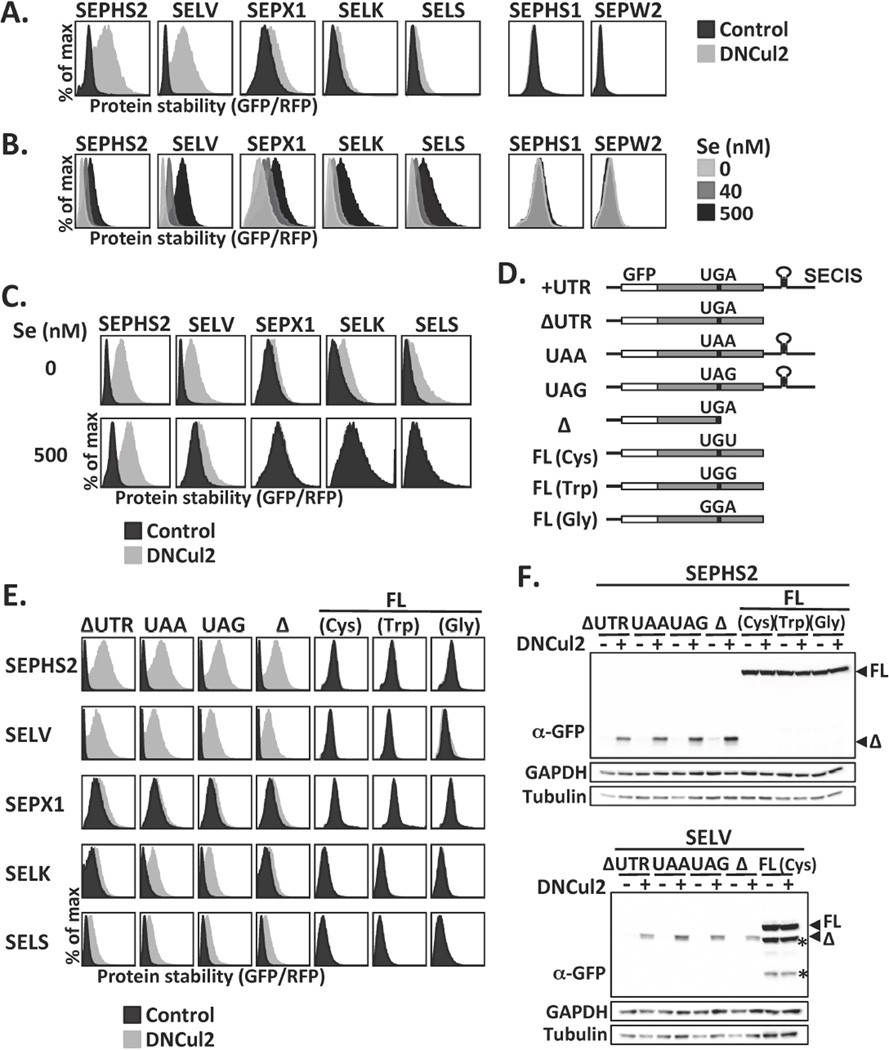

We developed GPS, a cell-based system for measuring global protein stability (13). In this system, the expression cassette contains a single promoter with an internal ribosome entry site, permitting the expression of two fluorescent proteins from one mRNA transcript. The first fluorescent protein RFP is the internal control, while the second fluorescent protein GFP is fused to the N-terminus of the protein of interest. The GFP/RFP ratio is a surrogate for protein stability measurements reading the relative steady-state abundance of GFP-fusion protein over RFP (13, 14). Coupling GPS with functional ablation of ubiquitin ligase, we generated a generic platform to isolate ubiquitin ligase substrates (14, 15). This strategy identified 102 substrates for the CRL2 ubiquitin ligase, including the five selenoproteins SEPHS2, SELV, SEPX1/MSRB1, SELK and SELS/VIMP from a GPS library containing 15,483 human open reading frames (ORFs) (Fig. S1A, S1B). We subcloned these selenoprotein genes into backgrounds resembling native transcripts (+UTR, Fig. 1D). Inhibition of CRL2 activity by either genetic perturbation or pharmacological treatment stabilized these selenoproteins, but not their paralogs without Sec (SEPHS1 and SEPW2) (Fig. 1A, S1C, S1D). The stability of selenoproteins was positively correlated with selenium availability (Fig. 1B); selenium supplementation attenuated CRL2-mediated selenoprotein degradation (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Selenoprotein degradation by CRL2. (A) HEK293T GPS reporter cells expressing selenoproteins from the UTR construct were treated or not treated with dominant-negative Cul2 (DNCul2), and then analyzed. (B) GPS assay for cells cultured in serum-free medium supplemented with various concentrations of sodium selenite. (C) GPS assay for cells cultured in serum-free medium with or without sodium selenite supplement and DNCul2 treatment. (D) A schematic representation and nomenclature of each selenoprotein mutant construct. (E) GPS analysis of selenoprotein mutants in (D). Full-length and truncated selenoproteins are presented using different x-axis scales to avoid off-scaling. (F) Western blot analysis of SEPHS2 or SELV mutants. Full-length (FL) and truncated (Δ) selenoproteins are indicated by arrowheads. Asterisks mark degradation products from full-length SELV. GAPDH and tubulin were loading controls.

The five selenoproteins identified share no sequence similarity (Fig. S1E). We generated various selenoprotein mutants to uncover the determinants for their degradation (Fig. 1D). Analysis of selenoprotein constructs exclusively expressing truncated proteins (ΔUTR, Δ, UAA, UAG) and those producing only full-length proteins (FL) via replacement of UGA to other codons, revealed that CRL2 selectively targeted truncated but spared full-length selenoproteins (Fig. 1E, 1F, S2A, S2B).

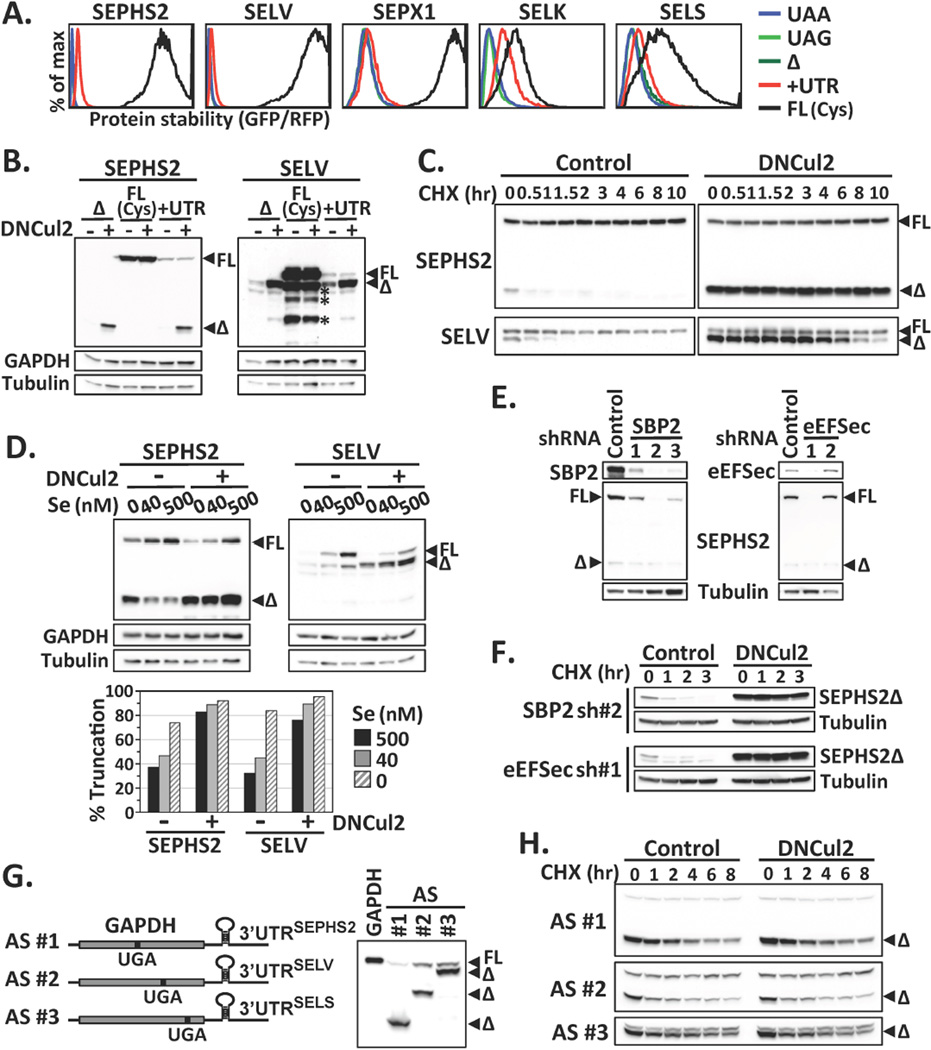

We asked whether CRL2 is responsible for removing prematurely terminated selenoproteins arising from failures in UGA/Sec reprograming. Full-length selenoproteins were more stable than truncated ones (Fig. 2A); the stability of selenoproteins expressed from the UTR construct fell in between, as expected from a mixture of full-length and truncated proteins. Indeed, two populations of proteins were translated from the UTR containing mRNAs upon CRL2 suppression, a shorter product terminated at the UGA codon and a longer read-through product, with the former as the only CRL2 substrate (Fig. 2B). Similar to full-length selenoproteins created by substituting the UGA codon (Fig. 1E, 1F), Sec-containing full-length selenoproteins were stable and exempted from CRL2 surveillance (Fig. 2C, S2C). Selenium availability had no effect on the stability of truncated or full-length selenoproteins (Fig. S2D). Rather, it enhanced the efficiency of Sec insertion (Fig. 2D). The accumulation of truncated selenoproteins was heightened by CRL2 inhibition, regardless of the selenium supplies (Fig. 2D, S2E). Endogenously made truncated selenoproteins were accumulated upon CRL2 inhibition (Fig. S3). Taken together, these results reveal a role of CRL2 as a gatekeeper in selenoprotein quality control.

Figure 2.

Failures in Sec incorporation and selenoprotein degradation. (A) Protein stability comparison among various forms of selenoproteins by GPS. (B) Western blot analysis of SEPHS2 or SELV mutants. Asterisks indicate degradation products from full-length SELV. (C) The stability of SEPHS2 or SELV proteins expressed from the UTR construct was subjected to cycloheximide (CHX)-chase analysis. (D) Cells expressing SEPHS2 or SELV from the UTR construct were cultured in serum-free medium supplied with graded increase of extracellular sodium selenite, with or without DNCul2 treatment, and analyzed by Western blotting. The percentage of truncated selenoprotein is shown below. (E) Cells expressing SEPHS2 from the UTR construct were treated with shRNAs for SBP2 or eEFSec and then analyzed by Western blotting. (F) The protein stability of SEPHS2 in cells treated with shRNAs for SBP2 or eEFSec was analyzed by CHX-chase. (G) A schematic representation of GAPDH artificial selenoprotein (AS) transcripts. Cells expressing wild-type GAPDH or AS were analyzed by Western blotting. The introduced in-frame UGA codon terminated GAPDH at the amino acid positions 152, 247 and 301. (H) CHX-chase analysis of GAPDH expressed from AS transcripts in (G).

CRL2 can recognize truncated SELK and SELS, even though these two proteins differ from their full-length counterparts by only three or two amino acids, respectively (Fig. S1E). CRL2 may recognize truncated selenoproteins by sensing incomplete translation via scouting the untranslated region of mRNA transcripts. Alternatively, components in Sec incorporation machinery may assist CRL2 to distinguish UGA-terminated selenoproteins. However, selenoproteins expressed from constructs lacking 3’UTRs or sequences 3’ to UGA remained CRL2 substrates (Fig. 1E, 1F). Protein half-lives of truncated selenoproteins from transcripts with or without 3’UTR were comparable (Fig. S4A). Moreover, knocking down SBP2 or eEFSec, trans-acting elements essential for Sec incorporation, decreased Sec insertion efficiency, but did not influence CRL2-mediated degradation (Fig. 2E, 2F). To examine whether CRL2-mediated degradation exhibits substrate specificity, we created artificial selenoproteins; CRL2 could not target UGA-terminated GAPDH made from GAPDH transcripts with in-frame UGA codons within the ORF and 3’UTR from authentic selenoproteins (Fig. 2G, 2H). Collectively, our data support the notion of direct recognition of truncated protein products by CRL2.

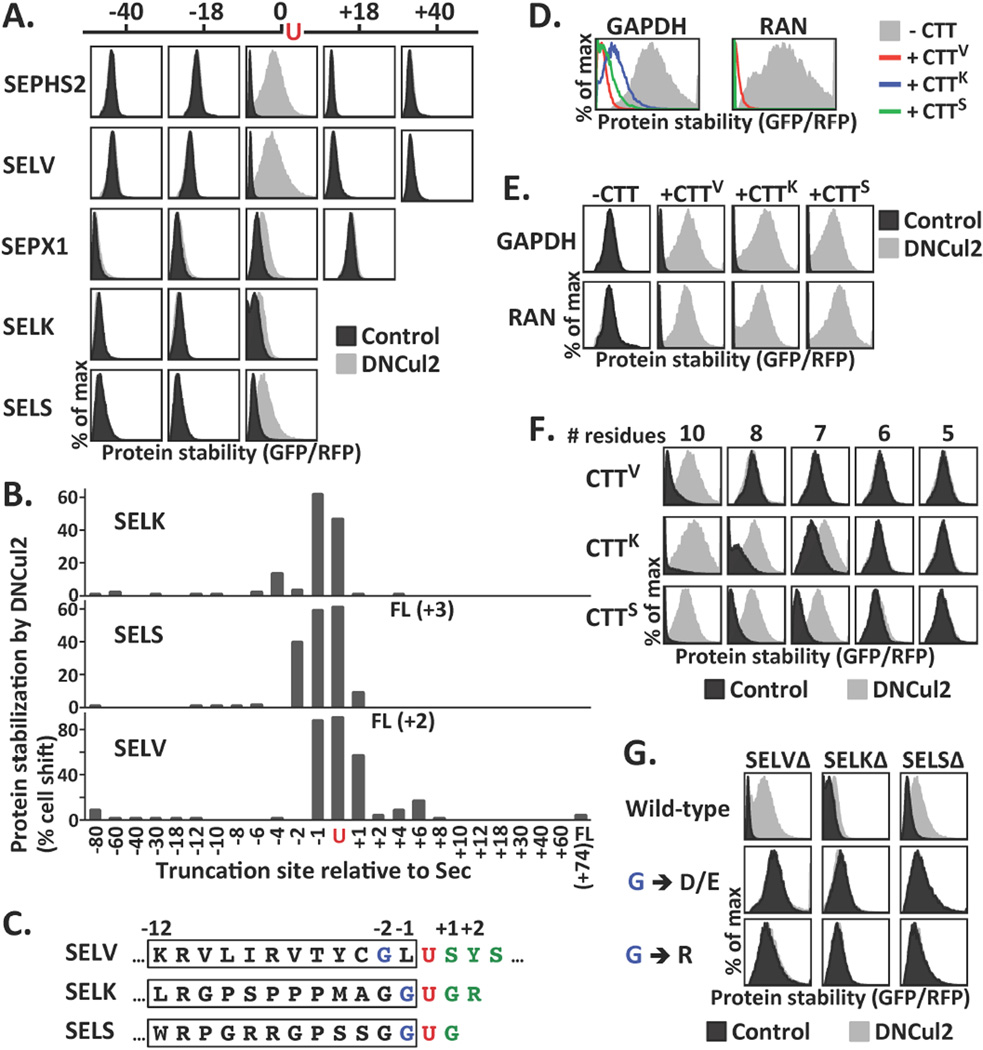

We systematically shortened (−) or extended (+) the length of the UGA-terminated selenoprotein (Δ) to elucidate how CRL2 recognized truncated selenoproteins. Truncations had to be made at the position within one to two amino acid residues originally translated into Sec so as to promote CRL2-mediated degradation (Fig. 3A, 3B, S4B). A 12-residue C-terminal tail of UGA-terminated selenoproteins (CTT) was sufficient to promote CRL2-mediated degradation (Fig. 3C, S5A, S5B). Fusion of CTTs to GAPDH and RAN, which are not natural CRL2 substrates, resulted in their degradation by CRL2 (Fig. 3D, 3E). Thus CTTs comprise transferable CRL2 degrons (degradation signals). The minimal CRL2 degrons can be as small as 10 or 7 residues in length (Fig. 3F).

Figure 3.

Identification of the determinants for CRL2-mediated selenoprotein degradation. (A) Selenoproteins of various lengths were compared for their stability upon DNCul2 treatment. The truncation site relative to Sec is labeled above. Constructs expressing proteins longer than UGA-terminated proteins carried a UGA-to-UGU mutation. Because the stability varied dramatically among proteins, the plots were scale-adjusted for optimal resolution. The GFP/RFP ratios from separate plots cannot be compared directly. (B) By GPS assay, stabilization of selenoproteins truncated at various locations after DNCul2 treatment was quantified. (C) The sequences near Sec in SELV, SELK and SELS. The Sec, its N-terminal glycine, and C-terminal residues are labeled in red, blue and green, respectively. The 12-residue C-terminal tail (CTT) is marked with a box. (D–E) The protein stability of GAPDH or RAN without or with CTT tags at the C-terminus was analyzed. CTTV, CTTK, CTTS represent the CTT of SELVΔ, SELKΔ and SELSΔ, respectively. (F) The stability of GAPDH tagged with various lengths of CTTs. (G) The stability of UGA-terminated selenoproteins with mutations in the glycine N-terminal to Sec.

We identified a critical glycine at the −1 position of SELK and SELS, or at the −2 position of SELV (Fig. 3C). Replacing this glycine with other amino acids abolishes CRL2-dependent degradation (Fig. 3G, S5B). Changing the leucine at the −1 position of SELV, next to this glycine, did not affect SELV degradation (Fig. S5C). The residues C-terminal to Sec, covering the degron, can tolerate more extreme replacement (Fig. S5D). Fusing the C-terminal end of UGA-terminated selenoproteins to GFP fully abrogated selenoprotein degradation (Fig. S5E). An illegitimate C-terminus, once exposed, triggers CRL2-mediated selenoprotein quality control. Rather than serving as a general inspector to eliminate every abnormal selenoproteins, CRL2 mediates the degradation to clear truncated translational products of unsuccessful UGA to Sec decoding.

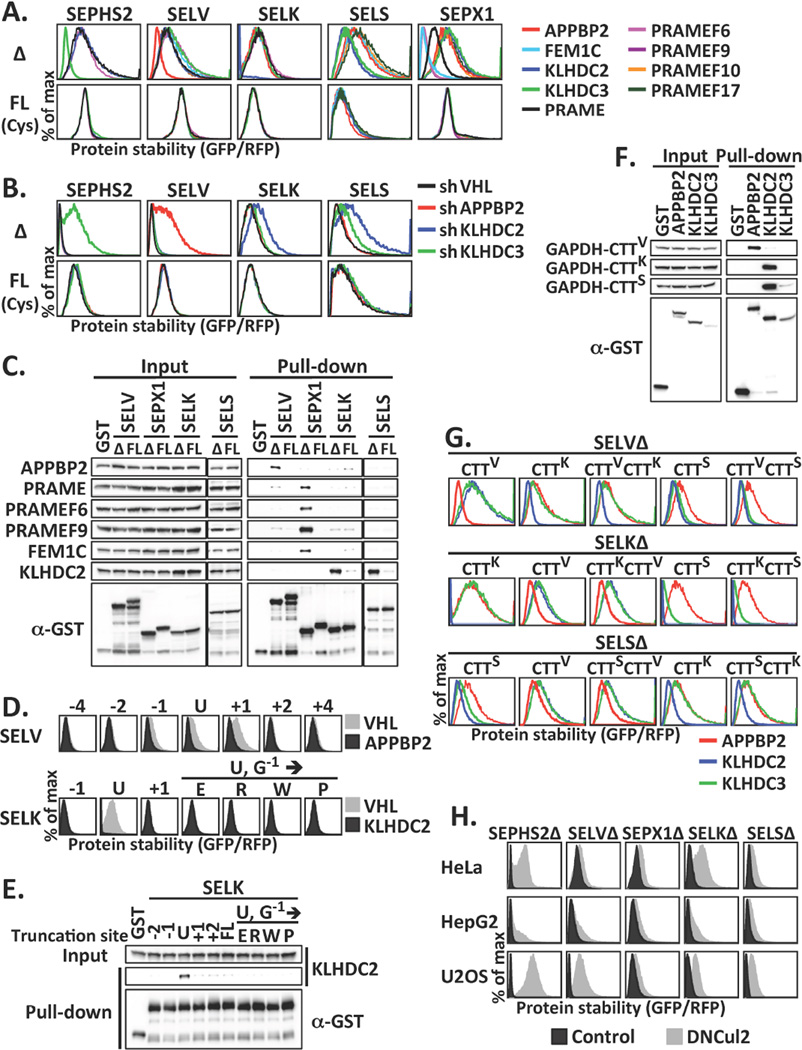

CRL2 is a modular ubiquitin ligase that utilizes an interchangeable set of BC-box proteins as substrate receptors when forming approximately 40 unique CRL2 complexes with a host of substrate specificities (16–19). We found that CRL2 targeted various UGA-terminated selenoproteins via distinct BC-box proteins (Fig. 4A, 4B, S6). KLHDC3, APPBP2 and KLHDC2 were used to target SEPHS2, SELV and SELK, respectively; SELS could be targeted by both KLHDC2 and KLHDC3. SEPX1 could be recognized by four BC-box proteins, namely PRAME, PRAMEF6, PRAMEF9 and FEM1C. Each BC-box protein was preferentially associated with the corresponding UGA-terminated selenoprotein over the full-length one (Fig. 4C, S6D, S6E). Furthermore, the substrate selectivity of CRL2 was attributed to BC-box proteins (Fig. 4D, 4E). Supporting that CTTs comprise CRL2 degrons, GAPDH-CTT fusions confer binding to the acceptor BC-box proteins (Fig. 4F). Swapping respective BC-box proteins can be achieved by exchanging CTTs or adding an extra CTT C-terminal to UGA-terminated selenoprotein (Fig. 4G, S7A).

Figure 4.

The BC-box proteins contribute to CRL2 recognition of truncated selenoproteins. (A) GPS assay for cells carrying UGA-terminated (Δ) or full-length (FL) selenoproteins infected with viruses expressing various BC-box proteins. (B) GPS assay for cells expressing Δ or FL selenoproteins treated with shRNAs against BC-box proteins. FL and Δ selenoproteins were presented using different x-axis scales. (C) GST pull-down using lysates expressing HA-tagged BC-box proteins and GST or GST-tagged Δ or FL selenoproteins. (D) GPS assay for cells expressing various forms of SELV or SELK infected with viruses expressing VHL, APPBP2, or KLHDC2. The truncation sites relative to Sec are labeled above. (E) GST pull-down using lysates expressing HA-tagged KLHDC2 and GST or various forms of GST-tagged SELK. (F) GST pull-down using lysates expressing GFP-tagged GAPDH-CTT fusion and GST or GST-tagged BC-box proteins. (G) The protein stability of truncated selenoproteins terminated with various CTTs. (H) The stability of UGA-terminated selenoproteins in various cells.

In examining the prevalence of proteolysis-assisted selenoprotein quality control, we detected CRL2-mediated quality surveillance for SEPHS2, SELV, SEPX1, SELK and SELS in all cell types tested (Fig. 4H, S8A). We surveyed six additional selenoproteins and identified one more CRL2 substrate, SEPW1. CRL2 also selectively degraded the UGA-terminated while sparing the read-through version of SEPW1 (Fig. S8B). Regardless of involvement of CRL2, full-length selenoproteins were more stable than their truncated counterparts, and truncated proteins were degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (Fig. S8C, S8D).

When selenium is limited, the transcripts of some, but not all, selenoproteins are driven toward degradation by the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay pathway (20–22). CRL2 provides an additional layer of defense against translational errors due to the duality in codon assignment. The tiered and complementary nature of these two safeguards grants robustness and fidelity of selenoprotein quality control. Here we report a mechanism by which CRL2 recognizes aberrant selenoproteins via various substrate receptors. We have allocated the peptide immediately N-terminal to Sec as the CRL2-targeting degron triggering degradation when placed at the C-terminal end of a protein (Fig. S9A). The CRL2 degrons are highly conserved across species (Fig. S9B). The BC-box proteins responsible for selenoprotein recognition do not share common substrate recognition motifs. Instead, they contain various structural motifs involved in general protein-protein interaction, such as Kelch, LRR, ANK and TPR repeats (Fig. S7B). APPBP2, KLHDC2, KLHDC3, PRAME and FEM1C have all been implicated in human diseases, although selenoproteins are their only identified substrates to date. Beyond exclusively serving as selenoprotein-specific inspectors, these CRL2 substrate receptors may play a broader role in targeted protein degradation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank HH Chuang, MD Tsai, CH Yeang, LY Chen, JY Leu and A Pena for suggestions, YF Chen, PY Hsieh, TT Lee, SY Lin, CY Tai and MC Tsai for technical assistance, and SJ Elledge, DE Hill and M Vidal for reagents. The CRL2 GPS screen was initiated at SJE’s laboratory and completed in HCY’s laboratory. Orbitrap data were acquired at the Academia Sinica Common Mass Spectrometry Facilities located at the Institute of Biological Chemistry. This work was supported by Career Development Award 101-CDA-L05 from Academia Sinica and MOST grant 103-2311-B-001-034-MY3 awarded to HCY, MOST grant 102-2113-M-019-003-MY2 to PHH, and NIH grant AG011085 to SJE.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambrogelly A, Palioura S, Soll D. Natural expansion of the genetic code. Nature chemical biology. 2007;3:29–35. doi: 10.1038/nchembio847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lobanov AV, Turanov AA, Hatfield DL, Gladyshev VN. Dual functions of codons in the genetic code. Critical reviews in biochemistry and molecular biology. 2010;45:257–265. doi: 10.3109/10409231003786094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee SR, et al. Mammalian thioredoxin reductase: oxidation of the C-terminal cysteine/selenocysteine active site forms a thioselenide, and replacement of selenium with sulfur markedly reduces catalytic activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:2521–2526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050579797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hatfield DL, Gladyshev VN. How selenium has altered our understanding of the genetic code. Molecular and cellular biology. 2002;22:3565–3576. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.11.3565-3576.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhong L, Holmgren A. Essential role of selenium in the catalytic activities of mammalian thioredoxin reductase revealed by characterization of recombinant enzymes with selenocysteine mutations. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275:18121–18128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000690200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kryukov GV, et al. Characterization of mammalian selenoproteomes. Science. 2003;300:1439–1443. doi: 10.1126/science.1083516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papp LV, Lu J, Holmgren A, Khanna KK. From selenium to selenoproteins: synthesis, identity, and their role in human health. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2007;9:775–806. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Driscoll DM, Copeland PR. Mechanism and regulation of selenoprotein synthesis. Annual review of nutrition. 2003;23:17–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.23.011702.073318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatfield DL, Carlson BA, Xu XM, Mix H, Gladyshev VN. Selenocysteine incorporation machinery and the role of selenoproteins in development and health. Progress in nucleic acid research and molecular biology. 2006;81:97–142. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(06)81003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donovan J, Copeland PR. Threading the needle: getting selenocysteine into proteins. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2010;12:881–892. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehta A, Rebsch CM, Kinzy SA, Fletcher JE, Copeland PR. Efficiency of mammalian selenocysteine incorporation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:37852–37859. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404639200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howard MT, Carlson BA, Anderson CB, Hatfield DL. Translational redefinition of UGA codons is regulated by selenium availability. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:19401–19413. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.481051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yen HC, Xu Q, Chou DM, Zhao Z, Elledge SJ. Global protein stability profiling in mammalian cells. Science. 2008;322:918–923. doi: 10.1126/science.1160489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emanuele MJ, et al. Global identification of modular cullin-RING ligase substrates. Cell. 2011;147:459–474. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yen HC, Elledge SJ. Identification of SCF ubiquitin ligase substrates by global protein stability profiling. Science. 2008;322:923–929. doi: 10.1126/science.1160462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahrour N, et al. Characterization of Cullin-box sequences that direct recruitment of Cul2-Rbx1 and Cul5-Rbx2 modules to Elongin BC-based ubiquitin ligases. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:8005–8013. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706987200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamura T, et al. VHL-box and SOCS-box domains determine binding specificity for Cul2-Rbx1 and Cul5-Rbx2 modules of ubiquitin ligases. Genes & development. 2004;18:3055–3065. doi: 10.1101/gad.1252404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okumura F, Matsuzaki M, Nakatsukasa K, Kamura T. The Role of Elongin BC-Containing Ubiquitin Ligases. Frontiers in oncology. 2012;2:10. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petroski MD, Deshaies RJ. Function and regulation of cullin-RING ubiquitin ligases. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2005;6:9–20. doi: 10.1038/nrm1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sunde RA, Raines AM, Barnes KM, Evenson JK. Selenium status highly regulates selenoprotein mRNA levels for only a subset of the selenoproteins in the selenoproteome. Bioscience reports. 2009;29:329–338. doi: 10.1042/BSR20080146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seyedali A, Berry MJ. Nonsense-mediated decay factors are involved in the regulation of selenoprotein mRNA levels during selenium deficiency. Rna. 2014;20:1248–1256. doi: 10.1261/rna.043463.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun X, et al. Nonsense-mediated decay of mRNA for the selenoprotein phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase is detectable in cultured cells but masked or inhibited in rat tissues. Molecular biology of the cell. 2001;12:1009–1017. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.4.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.