Abstract

Background

This study evaluated the extent to which the addition of disulfiram and contingency management for adherence and abstinence (CM), alone and in combination, might enhance the effects of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for cocaine use disorders.

Methods

Factorial randomized double blind (for medication condition) clinical trial where CBT served as the platform and was delivered in weekly individual sessions in a community-based outpatient clinic. 99 outpatients who met DSM-IV criteria for current cocaine dependence were assigned to receive either disulfiram or placebo, and either CM or no CM. Cocaine and other substance use was assessed via a daily calendar with thrice weekly urine sample testing for 12 weeks with a one-year follow-up (80% interviewed at one year).

Results

The primary hypothesis that CM and disulfiram would produce the best cocaine outcomes was not confirmed, nor was there a main effect for disulfiram. For the primary outcome (percent days of abstinence, self report), there was a significant interaction, with the best cocaine outcomes were seen for the combination of CM and placebo, with the two groups assigned to disulfiram associated with intermediate outcomes, and poorest cocaine outcome among those assigned to placebo and no CM. The secondary outcome (urinalysis) indicated a significant effect favoring CM over no CM but the interaction effect was not significant. One year follow-up data indicated sustained treatment effects across conditions.

Conclusions

CM enhances outcomes for CBT treatment of cocaine dependence, but disulfiram provided no added benefit to the combination of CM and CBT. Clinical trials.gov identifier: NCT00350870

Keywords: cocaine dependence, disulfiram therapy, contingency management, cognitive therapies, randomized trial

1. INTRODUCTION

Although cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has comparatively strong evidence for its efficacy as treatment for cocaine dependence (Dutra et al., 2008) and appears to be a particularly durable approach (Carroll et al., 1994b), outcomes may be enhanced when combined with pharmacotherapy and/or behavioral therapies that target complementary outcomes and mechanisms (Carroll et al., 2004c). One such approach is disulfiram, which has comparatively good empirical support for the treatment of cocaine dependence (Carroll et al., 2004a; Cubells, 2006; Oliveto et al., 2011; Suh et al., 2006). Disulfiram may contribute to reductions in cocaine use by (1) diminishing some of the reinforcing aspects of cocaine when it is used (Baker et al., 2007; Carroll et al., 1998b, 1994a; Cubells, 2006; Schroeder et al., 2011), and (2) helping cocaine users who also abuse alcohol refrain from concurrent cocaine-alcohol use (McCance-Katz et al., 1998) and hence alcohol-precipitated relapses to cocaine use. Disulfiram may complement CBT in several ways: First, by helping patients achieve longer periods of abstinence during treatment, disulfiram may facilitate greater exposure to and more effective learning of CBT skills and techniques. Second, the ability to implement coping skills for urges to use may be improved if patients perceive cocaine as less reinforcing while taking disulfiram. Third, disulfiram improves early retention, potentially ‘holding’ patients in treatment until the effects of CBT have an opportunity to emerge (Carroll et al., 1998b, 2000a). However, disulfiram’s efficacy is dependent on patient adherence which can be problematic among substance users (O’Farrell and Litten, 1992).

Another evidence-based approach for cocaine dependence that may improve CBT’s potency is CM (Dutra et al., 2008). One advantageous feature of CM is the precision and specificity with which it can be combined with other therapies to target their specific weaknesses (Carroll et al., 2004c; Petry et al., 2001): Reinforcement of submission of drug-free urine specimens reliably produces abstinence (Higgins et al., 2000; Lussier et al., 2006; Petry et al., 2006); in addition, CM can increase adherence and outcome with medications like disulfiram where efficacy is undercut by noncompliance by reinforcing compliance (Sorensen et al., 2007; Rigsby et al., 2000; Carroll et al., 2001). Although the effects of CM and disulfiram tend to weaken when no longer administered (Carroll et al., 2000a; Higgins et al., 2000), CBT’s effects are often more durable and strengthen after treatment ends, presumably due to the persistence of skills learned. Thus, combining CBT with potent but more short-lived approaches that may enhance retention in CBT and foster greater exposure to its active ingredients via CM may ultimately enhance its efficacy.

The current trial evaluated the extent to which outcomes from CBT treatment of cocaine dependence could be enhanced by adding CM, disulfiram, and the combination of CM and disulfiram via a 2×2 factorial design. We hypothesized (1) a main effect for disulfiram over placebo, (2) a main effect of CM over no CM, and (3) an interaction of CM and disulfiram showing superiority of the combined treatments being added to CBT.

2. METHODS

2.1 Participants

Participants were recruited from individuals seeking outpatient treatment for cocaine dependence at the APT Foundation, a private non-profit community based substance abuse treatment center. Individuals were included as participants if they were 18 years or older and met current DSM-IV criteria for current cocaine dependence, as assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) interviews at baseline. Individuals were excluded if they (1) were currently dependent on another drug (except tobacco) or whose principal drug use was not cocaine, (2) met lifetime DSM-IV criteria for a non-substance-induced psychotic or bipolar disorder, (3) had a current medical condition which would contraindicate disulfiram treatment (e.g. hepatic or cardiac issues, hypertension, pregnancy), as assessed by baseline physical examination (including EKG, urinalysis and blood work), or (4) were not sufficiently stable for outpatient treatment and had not received addiction treatment in the past 90 days.

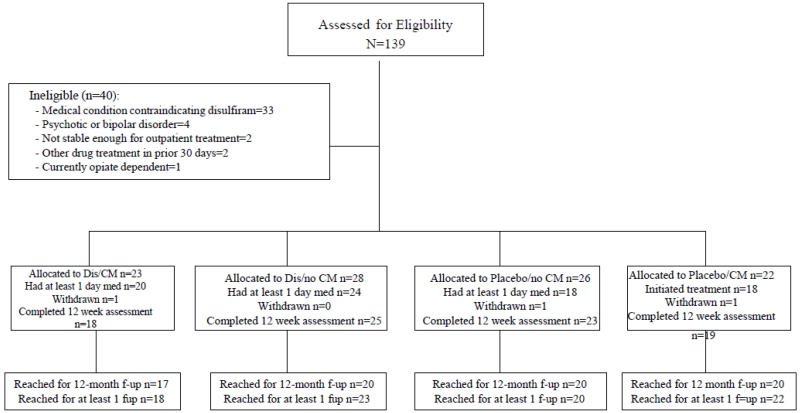

Ninety-nine of the 139 individuals screened were determined to be eligible for the study, provided informed consent and were randomized. Reasons for ineligibility are described in Figure 1. A computerized urn randomization program used in several previous trials (Ball et al., 2007; Carroll et al., 2004a, 2009; Stout et al., 1994) was used to produce equivalent group size and balance groups with respect to baseline level of cocaine use (more or less than 11 days per month), presence of alcohol dependence (yes/no), gender and ethnicity (ethnic minority/non-minority).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram.

2.2 Treatments

All participants received weekly individual CBT. Participants also met thrice weekly with research staff blind to medication condition who collected urine and breath samples, dispensed study medication, and monitored other clinical symptoms. Adverse events and blood pressure were monitored weekly.

2.2.1 Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

CBT was delivered in 50-minute individual weekly sessions by 12 clinicians (3 held doctorates and 9 were masters level PhD candidates; mean age 33.5; mean 4.6 years of experience in delivering CBT) who completed a two-day didactic seminar, and demonstrated competence in CBT by meeting pre-specified criteria for competence on the basis of ratings of audiotapes of their training cases using a validated treatment process rating system (Carroll et al., 1998a, 2000b). As described in the manual (Carroll, 1998), the goal of CBT is abstinence from cocaine and other substances via functional analysis of high risk situations, development of effective coping strategies and altering maladaptive cognitions associated with the maintenance of cocaine use.

2.2.2 Disulfiram

Participants assigned to disulfiram treatment were prescribed 250 mg of disulfiram daily, the dose used in previous trials (Carroll et al., 2004a, 1998b; George et al., 2000; Petrakis et al., 2000). Participants assigned to placebo received identical capsules in order to maintain the blind. All study medication capsules contained a riboflavin tracer (Del Boca et al., 1996; Kapur et al., 1992; Young et al., 1984) to monitor compliance. Of 1,218 urine samples collected (1121 positive for the tracer), 92% were consistent with participant self-report; only 91 (8%) did not fluoresce in cases where the patient indicated they had taken their study medication since the last visit. A randomly selected subset of 98 samples was sent to a commercial laboratory for analysis of riboflavin level. Of these, 77 (79%) matched the staff determination (73 positive; 4 negative).

All participants were cautioned not to drink alcohol while in the study and to presume they were taking disulfiram. Breath samples were collected prior to thrice weekly dispensing of medication. Of 1,298 breath samples collected during the trial, only one indicated recent alcohol use. To evaluate the medication blind, participants and the project nurse were asked to guess medication assignment at the end of the trial. Sixty-four percent of the 73 participants guessed their condition correctly, significantly better than chance (X2= −2.50, p = .012). The project nurse, who dispensed medication and assessed adverse events, guessed no better than chance (49%).

2.2.3 Contingency management (CM)

In this condition, in addition to standard CBT and study medication as described above, participants earned chances to draw prizes from a bowl contingent on two independent behaviors (medication adherence and cocaine negative urine specimens). Using procedures described by Petry (Budney and Higgins, 1998; Petry, 2000; Petry et al., 2000, 2006), participants earned at least one draw each time they ingested study medication witnessed by staff and each time they submitted a submitted a cocaine-free urine specimen. The number of draws earned escalated by one each time the participant exhibited each behavior up to 7 draws maximum for medication adherence and cocaine abstinence per visit. Failure to attend the clinic for medication administration or to take the medication resulted in a reset in the number of medication adherence draws to one at the next visit. Similarly, if a participant submitted a cocaine-positive urine specimen or failed to submit a specimen on a scheduled assessment session, the number of draws decreased back down to one for the next negative sample submitted. Participants consistently abstinent from cocaine and fully compliant with medication visits could earn a maximum of 462 draws during the 12-week treatment period (231 for cocaine-free urine samples and 231 possible medication adherence draws).

The expected mean value of prizes drawn for participants who were eligible for the maximum number of draws was $800 over the 12-week period. The bowl contained 750 plastic coins. Of those, 75 were small prizes ($1 value, fast food restaurant coupons, food items, bus tokens), 20 were medium prizes ($5 value; choice of mugs, makeup, toiletries), 15 were large prizes, worth up to $20 in value (movie tickets, phone cards, watches), and three were jumbo prizes worth up to $100 (music players, small television) (Petry et al., 2007, 2001).

2.3 Assessments

Participants were assessed before treatment, weekly during treatment (urine and breath samples were completed three times weekly; participants received a gift card worth $5 for each completed assessment), at the 12-week treatment termination point, and at follow-up interviews conducted at three-month intervals through a year after treatment termination. In cases where a randomized participant did not initiate (n=19) or dropped out of treatment, he or she was interviewed at the 12-week point and throughout follow-up in order to collect data from the intention-to-treat sample, regardless of level of treatment involvement. Thus, complete 12 week self-report data were available for 85 of 99 (86%) of the randomized sample.

The Substance Use Calendar, similar to the Timeline Follow Back (Robinson et al., 2012), was administered weekly during treatment to collect detailed day-by-day self-reports of cocaine, alcohol, and other drug use for the three months prior to baseline assessment, throughout the 84-day treatment period and at each follow-up interview (18 months total). Self-reports of cocaine were verified through onsite urine toxicology screens (ToxCup Drug Screen Cup 5 with adulterant checks) that were obtained three times weekly during treatment and at each follow-up.

Follow-up interviews included collection of urine/breath samples and the Substance Use Calendar and were conducted one, three, six, nine and 12 months after the 12-week termination point. Of the 99 individuals randomized, 88% were reached for at least one follow-up, and 79 (80%) were reached for the final 12-month follow-up. There were no significant differences across treatment conditions in terms of rates of follow-up overall or at any specific follow-up point.

2.4 Data analyses

The primary outcome measure was self-reported cocaine use (operationalized as percent days of cocaine use during treatment). Percent of cocaine-negative urine toxicology screens was included a secondary measure because thrice weekly data collection can lead to overestimation of cocaine use due to carry-over effects (Preston et al., 1997). Following FDA recommendations, we included another secondary measure, a dichotomous indicator of ‘treatment success’, that is, percentage of participants achieving three or more weeks of continuous abstinence, which has been shown to be an indicator of good long-term cocaine outcomes in several previous studies (Carroll et al., 2014; Donovan et al., 2012).

ANOVA models were used to analyze primary and secondary cocaine outcome variables using a standard two-factor design. To analyze changes in frequency of cocaine use over time, random effect regression models (Bryk and Raudenbush, 1987) were used to evaluate change across time for frequency of cocaine use with the same factors. A piecewise random effect regression model (Singer and Willett, 2003) was used to evaluate change across treatment phases (comparing differences in slope between the treatment versus follow-up periods) by treatment condition. In addition to the principal analyses conducted on the 99 participants randomized to treatment (intention to treat sample), supplemental analyses were also conducted for the 80 who initiated treatment (treatment exposed sample). Results were consistent across analysis samples, thus only data from the intention to treat sample are presented here.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Sample characteristics

Sample characteristics by treatment condition are presented in Table 1; there were no statistically significant differences across groups on multiple demographic and baseline substance use variables. The sample was predominantly male (73.7%), ethnic minority (African American, 49.5%, Latino/a 7.1%), single (71.7%), unemployed (66.7%), and had at least a high school education (85.9%). Participants reported they used cocaine an average of 14.1 days of the past 28 and drank alcohol an average of 7.6 days of the past 28.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic, psychiatric, and substance use characteristics by treatment condition

| Disulfiram/ CM1 |

Disulfiram/ no CM |

Placebo/ no CM |

Placebo/ CM |

Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n= 23 | n= 28 | n= 26 | n= 22 | n= 99 | F or X2 | p |

| Number (percent) female | 7 (30.4%) | 9 (32.1%) | 4 (15.4%) | 7 (31.8%) | 27 (27.3%) | 2.53 | .47 |

| Ethnicity, number (%) | |||||||

| Caucasian | 14 (60.9) | 11(39.3) | 11 (42.3) | 3 (13.6) | 39 (39.4) | 13.89 | .13 |

| African-American | 8 (34.8) | 14 (50) | 12 (46.2) | 15 (68.2) | 49 (49.5) | ||

| Latino | 0 (0) | 3 (10.7) | 2 (7.7) | 2 (9.1) | 7 (7.1) | ||

| Multiracial/other | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.8) | 2 (9.1) | 4 (4.0) | ||

| Number (%) completed high school | 22 (95.7) | 24 (85.7) | 21 (80.8) | 18 (81.8) | 85 (85.9) | 2.67 | .45 |

| Number (%) never married/living alone | 14 (60.9) | 19 (67.9) | 23 (88.5) | 15 (68.2) | 71 (71.7) | 5.27 | .15 |

| Number (%) unemployed | 14 (60.9) | 17 (60.7) | 22 (84.6) | 13 (59.1) | 66 (66.7) | 5.13 | .16 |

| Number (%) alcohol use disorder – lifetime2 | 17 (73.9) | 24 (85.7) | 19 (73.1) | 14 (63.6) | 74 (74.7) | 3.27 | .35 |

| Number (%) major depression – lifetime2 | 3 (13.0) | 5 (17.9) | 6 (23.1) | 4 (18.2) | 18 (18.2) | 0.83 | .84 |

| Number (%) anxiety disorder – lifetime2 | 2 (8.7) | 2 (7.1) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 5 (5.1) | 2.14 | .54 |

| Number (%) on probation or parole | 6 (26.1) | 5 (17.9) | 5 (19.2) | 5 (22.7) | 21 (21.2) | 0.61 | .90 |

| Age, mean (standard deviation) | 39.3 (6..3) | 39.8 (7.5) | 39.6 (8.8) | 38.5 (7.4) | 39.3 (7.5) | 0.14 | .94 |

| Days of alcohol use, 28 prior to baseline, mean (SD) | 7.6 (9.2) | 8.7 (7.9) | 8.6 (9.9) | 4.7 (6.4) | 7.5 (8.5) | 1.15 | .33 |

| Days cocaine use, past 28, mean (SD) | 16.0 (8.0) | 13.6 (8.0) | 14.6 (7.4) | 12.0 (6.9) | 14.1 (7.6) | 1.08 | .36 |

| Years of regular cocaine use, mean (SD) | 8.2 (5.5) | 11.1 (7.4) | 11.3 (7.0) | 8.1 (7.3) | 9.8 (6.9) | 1.59 | .20 |

| Total # months incarcerated, lifetime, mean (SD) | 18.2 (34.0) | 24.9 (47.9) | 23.5 (30.9) | 23.3 (46.9) | 22.6 (40.2) | 0.13 | .94 |

Note.

Indicates prize based contingency management (CM),

indicates ascertained via Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID).

3.2 Treatment adherence and CM delivery

As shown in Table 2, there were no differences across treatment group, medication (disulfiram versus placebo), or contingency management (CM versus no CM) in terms of days retained in the 84 day treatment protocol, number of scheduled CBT sessions completed, percentage of study days the participant reported taking their study medication as prescribed, or number of urine specimens collected. In terms of exposure to CM reinforcement, there were no statistically significant differences across treatment conditions (Disulfiram+CM versus Placebo+CM) in terms of total number of opportunities to draw prizes (mean=141.1 draws, sd=147.3), total prizes received (mean= 84.1, sd=94.6), or estimated cash value of prizes received (mean $415.4, sd=661.9). Similarly, there were no statistically significant differences across groups in terms of exposure to number of opportunities earned for drawing prizes based on cocaine-free urines (mean=51.7, sd=73.5) or taking study medication as prescribed (mean=89.3, sd=79.5).

Table 2.

Adherence and primary outcomes by treatment condition

| Placebo/ no CM1 |

Disulfiram / no CM |

Placebo/ CM | Disulfiram/ CM |

TOTAL | Disulfiram | CM | Disulfiram by CM |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n=26 | n=28 | n=22 | n=23 | n=99 | |||||||||||

| mean | sd | mean | sd | mean | sd |

mea

n |

sd |

mea

n |

sd | F | p | F | p | F | p | |

|

Treatment adherence

indicators |

||||||||||||||||

| Days retained in treatment protocol2 |

24.9 | 31.0 | 43.1 | 37.5 | 36.7 | 33.4 | 43.2 | 35.7 | 36.9 | 34.9 | 3.13 | .08 | 0.73 | .40 | 0.70 | .40 |

| Mean percent days compliant with study medication |

90.4 | 12.5 | 87.3 | 15.8 | 89.2 | 18.6 | 88.4 | 11.8 | 88.7 | 14.7 | 0.33 | .57 | 0.00 | .98 | 0.11 | .74 |

| Percent treatment days of abstinence from alcohol, self-report |

91.6 | 16.7 | 88.1 | 23.0 | 93.4 | 21.5 | 90.0 | 23.1 | 90.6 | 20.9 | 0.58 | .45 | 0.16 | .69 | 0.00 | .99 |

| Primary outcome | ||||||||||||||||

| Percent treatment days abstinence from cocaine-self report |

72.2 | 27.3 | 79.2 | 18.1 | 91.1 | 13.6 | 69.6 | 31.7 | 77.8 | 24.4 | 2.02 | .16 | 0.85 | .36 | 7.84 | .01 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||||||||||||

| Percent cocaine-negative urines submitted3 |

28.7 | 36.8 | 39.5 | 40.8 | 60.5 | 35.3 | 41.2 | 40.3 | 43.1 | 39.3 | 0.08 | .79 | 4.74 | .03 | 2.19 | .14 |

| Percent of participants abstinent three or more continuous weeks (number, %) |

2 | 8.7% | 7 | 25% | 9 | 40.9% | 6 | 26.1% | 24 | 24.2 % |

1.10 | .30 | 0.01 | .93 | 3.7 | .05 |

3.3 Cocaine use during treatment

Of 1,135 urine specimens collected during the 12 week treatment phase, 1003 (88.4%) were consistent with the participants’ self-reports of recent cocaine use, 106 (9.3%) tested negative for cocaine although the participant reported recent cocaine use, and 26 (2.3%) were positive for cocaine in cases where the participant had denied use. This rate compares favorably with previous studies of cocaine-dependent and other substance using samples evaluating the accuracy of self-report data using the methods described here (Babor et al., 2000; Zanis et al., 1994).

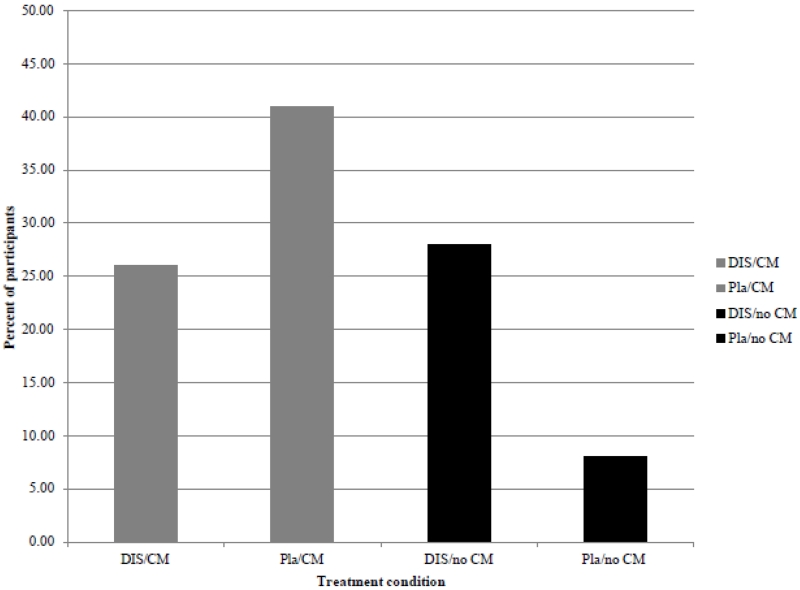

Primary and secondary outcomes by condition are shown in Table 2. There were no main effects of condition (CM or medication) for percent days of self-reported abstinence from cocaine during treatment, but there was a significant interaction of CM and medication condition (p<0.01). For patients assigned to placebo, CM was associated with a higher percentage of abstinent days (91%), than those not assigned to CM (72%); for those assigned to disulfiram, CM’s effects were less pronounced (69% for CM, 79% no CM). Regarding the secondary outcomes, there was a statistically significant effect of CM on percent of cocaine-negative urine specimens (no CM 36.6% negative; CM 55.9% negative, p=.03), but the interaction was not significant. For the percent of participants who were continuously abstinent from cocaine for 3 or more weeks, effects were also similar in that there was a CM by medication interaction as illustrated in Figure 2. There were no statistically significant interactions of treatment condition on the cocaine outcomes for the subgroup of subjects who presented with a lifetime diagnosis of alcohol abuse or dependence (ps>.10, data not shown).

Figure 2.

Percentage of participants in each condition attaining three or more weeks of abstinence at any point in the trial, self-report

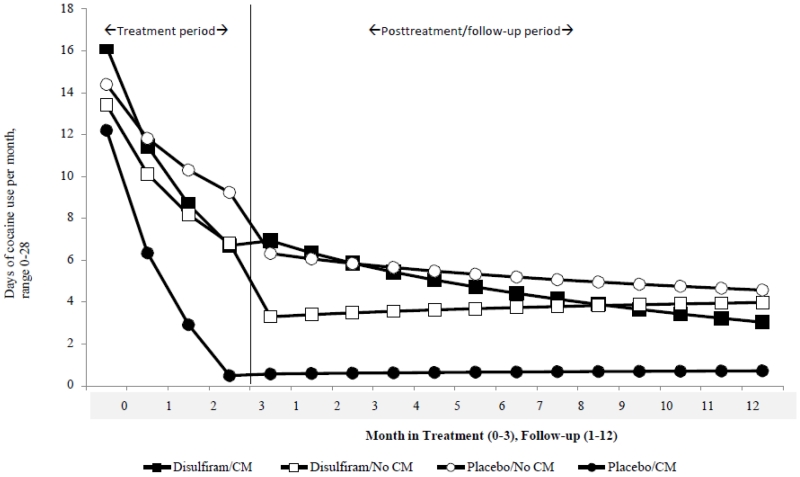

3.4 Efficacy of study treatments within treatment through follow-up

Random effects regression models evaluating the rates of change in frequency of cocaine use over time by condition indicated that for the within-treatment data, results were consistent with those reported above and indicated significant effects of time (F=87.5, p<.001) and CM by time (F=11.5, p=.001), indicating greater change from baseline to end of treatment for participants assigned to CM, but no significant treatment by time effect for disulfiram. As illustrated in Figure 3, the greatest difference was found between the group assigned to CM/placebo compared with the no CM/placebo groups, with intermediate effects seen for both groups assigned to disulfiram.

Figure 3.

Change in frequency of cocaine use over time (days of use per month), from baseline to posttreatment and to end of follow-up, by treatment condition, estimates from random regression analyses.

Cocaine use during the one year follow-up was also analyzed via piecewise random effects regression (treating the within-treatment and follow-up phases as a main effect factor and including interaction terms for treatment conditions and phase)(Singer and Willett, 2003). These analyses indicate significant effects for time (F=83.0; p<.001) and phase (F=53.3; p<.001), suggesting that participants as a group reduced their frequency of cocaine use from pretreatment to the end of follow-up and the frequency of cocaine use differed by phase. There were also significant effects for CM by time (F=6.8, p=.01), suggesting greater reduction in cocaine use overall for those assigned to CM, as well as an interaction of medication by CM by phase (F=8.3, p<.01) similar to those reported above.

3.5 Adverse events by medication condition

Study medications were well tolerated, and reports of most adverse effects did not differ across treatment conditions. These included headache (reported by 26.2% of participants), diarrhea or constipation (19.7%), drowsiness (18%), or restlessness (16.4%). Only two symptoms were reported by significantly more frequently for participants assigned to disulfiram compared with placebo; these included nausea or vomiting (26.5% for disulfiram versus 7.4% for placebo, X2=3.70, p=.05), and aftertaste (41.2% versus 11.1%, X2=6.77, .01). Blood pressure was monitored weekly during treatment by the study nurse; frequency of elevated blood pressure (above 130 systolic or diastolic over 90) did not differ across medication conditions (20.5% in disulfiram versus 22.2%; in placebo, NS).

Retention and treatment outcomes by genotype and treatment condition are presented in Table 2 for rs1611115. In general, individuals with the CT/TT genotype had better outcomes when assigned to disulfiram versus placebo, and individuals with the CC genotype had better outcomes when assigned to placebo than disulfiram. These effects were statistically significant for the dichotomous indicator (3 or more weeks of continuous abstinence) and reached trend level for retention in treatment.

4. DISCUSSION

Data from this randomized trial evaluating CM and disulfiram to enhance outcomes of CBT treatment for cocaine dependence suggested the following: First, the primary hypothesis regarding better outcomes for the combined CM and disulfiram was not confirmed. Rather, analyses of the primary outcomes indicated a significant interaction effect such that those assigned to CM and placebo had best outcomes, those assigned to no CM and placebo had poorest outcomes, with mixed results for the disulfiram group such that disulfiram did not appear to further enhance CM’s effects. Second, analyses based on results of urine toxicology screens indicated a significant main effect for CM, most likely reflecting reinforcement of cocaine-negative urine specimens. Third, follow-up cocaine outcomes remained improved across treatment conditions, with best overall outcomes for those assigned to CM and placebo. Furthermore, little to no ‘rebound’ after cessation of CM and/or medication was seen during the follow-up period. Finally, disulfiram appeared safe in this sample, with no significant difference in cardiovascular effects or hypertension across medication groups, concerns that have been raised regarding its use with cocaine abusers (Roache et al., 2011). There were some differences in reported frequency of nausea/vomiting, which may reflect some ‘testing’ of the disulfiram effect by participants. Overall, results of this study were consistent with the existing strong level of support for CM for the treatment of cocaine dependence. In this study, CM was associated with rapid, and comparatively durable, reductions in cocaine use. It is of note that all participants in this study also received CBT, which has been shown to be a relatively durable approach in a number of cocaine treatment trials (Carroll and Onken, 2005).

Contrary to our a priori hypotheses, however, CM was not associated with significantly better retention in treatment or adherence with medication. Participants assigned to CM did receive reinforcement at a meaningful level of reward (approximately $400 per participant) commensurate with multiple studies where prize based contingency management has been shown to be effective (Petry et al., 2007). A comparatively large number of participants dropped out of the protocol between randomization and initiation of treatment (n=19). However, once treatment was initiated, retention in treatment, medication compliance, and number of urines submitted did not differ across conditions. Given that all participants received a small compensation for providing self-report and urine specimens thrice weekly, it is possible that this was sufficient to support medication compliance for those that initiated treatment. Hence, while CM did have an effect on submission of cocaine-free urine specimens, reinforcing medication adherence appeared not to yield an advantage to simply providing medication alone with CBT when attendance was reinforced.

In contrast, the efficacy of disulfiram presented a more complex picture in this sample. There was no evidence of a main effect of disulfiram on either alcohol (use of which was comparatively low during treatment) or cocaine use. Participants generally avoided alcohol use while in treatment, although some testing of the disulfiram effect likely occurred, as reflected in the increased rates of nausea for those assigned to disulfiram. Contrary to our previous findings (Carroll et al., 2004b), there was no evidence that disulfiram was differentially effective among those with or without a history of alcohol dependence. Consistent with a growing body of literature (Malcolm et al., 2008; Roache et al., 2011), disulfiram appeared safe in this sample, with no serious adverse events or hypertension or cardiac events attributable to disulfiram treatment. Adverse events were relatively mild, and the few that were significantly different between disulfiram and placebo appeared consistent with the disulfiram-ethanol reaction.

While there was no overall main effect of disulfiram over placebo, either within treatment or during follow-up, statistically significant disulfiram-CM interactions were seen for the primary and the dichotomous ‘success’ outcome, with similar, if not statistically significant, effects for the biological (urine) indicator. In general, best outcomes were seen for the combination of CM and placebo, with the two groups assigned to disulfiram associated with intermediate outcomes, and poorest cocaine outcome among those assigned to the ‘double control’ condition (placebo + no CM). This suggests marked heterogeneity in response to disulfiram. This trial included several important design features intended to enhance internal validity, including random assignment to treatment using an urn variable program, use of the riboflavin tracer to monitor medication compliance across conditions, thrice weekly collection of urine specimens in conjunction with monitored medication ingestion, and a one-year follow-up with collection of follow-up data from 88% of the intention-to-treat sample. Nevertheless, limitations of this trial included fairly high attrition, with the majority of participants not completing the full 12-week course of treatment. While the factorial design, which enhanced power to evaluate main effects of disulfiram and CM, as well as efforts to contact and interview individuals who dropped out of treatment yielded complete data from 88% of the sample, the overall sample size had limited power to evaluate interaction effects or permit subgroup analyses, as we did not reach our targeted recruitment goal of 120. Despite these limitations, results from this study underscored the benefit of CM in reducing cocaine use, and indicated the addition of disulfiram did not further enhance CM’s effects.

Highlights.

Disulfiram and contingency management may improve cocaine treatment outcomes

In a sample of cocaine users, these treatments were evaluated alone and in combination.

Adding contingency management (CM) to cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) improved cocaine outcomes both within treatment and through follow-up.

The addition of disulfiram did not enhance the effects of CBT or CM in this sample.

Acknowledgement

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of David Iamkis for invaluable assistance with medication preparation and delivery, Karen Hunkele, Theresa Babuscio, and Tami Frankforter for data management and analysis, Joanne Corvino for training and quality assurance, and Elizabeth Vollono in carrying out the study. We express special thanks to the staff and patients at the APT Foundation and its Central Medical Unit.

Support was provided by National Institute on Drug Abuse grants R01 DA019078, P50-DA09241, K12 DA00167 and K05-DA00457.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial disclosures:

None of the authors have other relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Conflict of interest:

None

Contributors

Author Carroll was PI of the NIDA award, oversaw training, implementation, and data analyses, and authored the first draft of the article.

Author Nich contributed to grant preparation, data analysis, and reviewed/contributed and approved the manuscript.

Author Eagan contributed to grant preparation, oversaw trial implementation, and reviewed/contributed and approved the manuscript.

Author Shi contributed to grant preparation, served as the trial physician, and reviewed/contributed and approved the manuscript.

Author Ball contributed to grant preparation, study implementation, and reviewed, contributed to and approved the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Babor TF, Steinberg K, Anton RF, Del Boca FK. Talk is cheap: measuring drinking outcomes in clinical trials. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2000;61:55–63. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JR, Jatlow PM, Mccance-Katz EF. Disulfiram effects on reponses to intravenous cocaine administration. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball SA, Martino S, Nich C, Frankforter TL, Van Horn D, Crits-Christoph P, Woody GE, Obert JL, Farentinos C, Carroll KM, National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials, N. Site matters: multisite randomized trial of motivational enhancement therapy in community drug abuse clinics. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2007;75:556–567. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Application of hierarchical linear models to assessing change. Psych. Bull. 1987;101:147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Higgins ST. A Community Reinforcement Plus Vouchers Approach: Treating Cocaine Addiction. NIDA; Rockville, MD: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM. A Cognitive-Behavioral Approach: Treating Cocaine Addiction. NIDA; Rockville, Maryland: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Ball SA, Nich C, O’Connor PG, Eagan D, Frankforter TL, Triffleman EG, Shi J, Rounsaville BJ. Targeting behavioral therapies to enhance naltrexone treatment of opioid dependence: efficacy of contingency management and significant other involvement. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2001;58:755–761. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Connors GJ, Cooney NL, DiClemente CC, Donovan DM, Longabaugh RL, Kadden RM, Rounsaville BJ, Wirtz PW, Zweben A. Internal validity of Project MATCH treatments: discriminability and integrity. J. Consult.Clin. Psychol. 1998a;66:290–303. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.2.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Fenton LR, Ball SA, Nich C, Frankforter TL, Shi J, Rounsaville BJ. Efficacy of disulfiram and cognitive-behavioral therapy in cocaine-dependent outpatients: a randomized placebo controlled trial. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2004a;64:264–272. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Fenton LR, Ball SA, Nich C, Frankforter TL, Shi J, Rounsaville BJ. Efficacy of disulfiram and cognitive behavior therapy in cocaine-dependent outpatients: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2004b;61:264–272. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Kiluk BD, Nich C, DeVito EE, Decker S, LaPaglia D, Duffey D, Babuscio TA, Ball SA. Toward empirical identification of a clinically meaningful indicator of treatment outcome: features of candidate indicators and evaluation of sensitivity to treatment effects and relationship to one year follow up cocaine use outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;137:3–19. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Martino S, Suarez-Morales L, Ball SA, Miller WR, Rosa C, Anez LM, Paris MP, Nich C, Frankforter TL, Matthews J, Szapocznik J. A multisite randomized effectiveness study of motivational enhancement therapy for Spanish-speaking substance abusers. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2009;77:993–999. doi: 10.1037/a0016489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Nich C, Ball SA, McCance-Katz E, Rounsaville BJ. Treatment of cocaine and alcohol dependence with psychotherapy and disulfiram. Addiction. 1998b;93:713–728. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9357137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Nich C, Ball SA, McCance-Katz EF, Frankforter TF, Rounsaville BJ. One year follow-up of disulfiram and psychotherapy for cocaine-alcohol abusers: Sustained effects of treatment. Addiction. 2000a;95:1335–1349. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95913355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Nich C, Sifry R, Frankforter T, Nuro KF, Ball SA, Fenton LR, Rounsaville BJ. A general system for evaluating therapist adherence and competence in psychotherapy research in the addictions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000b;57:225–238. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Onken LS. Behavioral therapies for drug abuse. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2005;162:1452–1460. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Gordon LT, Nich C, Jatlow P, Bisighini RM, Gawin FH. Psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for ambulatory cocaine abusers. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1994a;51:177–187. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950030013002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Kosten TR. Choosing a behavioral therapy platform for pharmacotherapy of substance users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004c;75:123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Nich C, Gordon LT, Wirtz PW, Gawin FH. One year follow-up of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for cocaine dependence: Delayed emergence of psychotherapy effects. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1994b;51:989–997. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950120061010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca FK, Kranzler HR, Brown J, Korner PF. Assessment of medication compliance in alcoholics through UV light detection of a riboflavin tracer. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1996;20:1412–1417. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan DM, Bigelow GE, Brigham GS, Carroll KM, Cohen AJ, Gardin JG, Hamilton JA, Huestis MA, Hughes JR, Lindblad R, Marlatt GA, Preston KL, Selzer JA, Somoza EC, Wakim PG, Wells EA. Primary outcome indices in illicit drug dependence treatment research: systematic approach to selection and measurement of drug use end-points in clinical trials. Addiction. 2012;107:694–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03473.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Basden SL, Leyro TM, Powers MB, Otto MW. A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2008;165:179–187. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George TP, Chawarski MC, Pakes JA, Carroll KM, Kosten TR, Schottenfeld RS. Disulfiram versus placebo for cocaine dependence in buprenorphine-maintained subjects: a preliminary trial. Biol. Psychiatry. 2000;47:1080–1086. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00310-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Wong CJ, Badger GJ, Haug-Ogden DE, Dantona RL. Contingent reinforcement increases cocaine abstinence during outpatient treatment and one year follow-up. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000;68:64–72. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S, Ganguli R, Ulrich R, Ranghu U. Use of random-sequence riboflavin as a marker of medication compliance in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 1992;6:49–53. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(91)90020-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussier JP, Heil SH, Mongeon JA, Badger GJ, Higgins ST. A meta-analysis of voucher-based reinforcement therapy for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2006;101:192–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malcolm R, Olive MF, Lechner W. The safety of disulfiram for the treatment of alcohol and cocaine dependence in randomized clinical trials: Guidance for clinical practice. Exp. Opin. Drug Safety. 2008;7:459–472. doi: 10.1517/14740338.7.4.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCance-Katz EF, Kosten TR, Jatlow PM. Concurrent use of cocaine and alcohol is more potent and potentially more toxic than use of either alone--a multiple dose study. Biol. Psychiatry. 1998;44 doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(97)00426-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell TJ, Litten RZ. Techniques to enhance compliance with disulfiram. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Research. 1992;16:1035–1041. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb00695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveto A, Poling J, Mancino MJ, Feldman Z, Cubells JF, Pruzinsky R, Gonsai K, Cargile C, Sofuoglu M, Chopra MP, Gonzalez-Haddad G, Carroll KM, Kosten TR. Randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial of disulfiram for the treatment of cocaine dependence in methadone-stabilized patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;113:184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrakis IL, Carroll KM, Gordon LT, Nich C, McCance-Katz E, Rounsaville BJ. Disulfiram treatment for cocaine dependence in methadone maintained opioid addicts. Addiction. 2000;95:219–228. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9522198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. A comprehensive guide to the application of contigency management procedures in clinical settings. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;58:9–25. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Alessi SM, Hanson T, Sierra S. Randomized trial of contingent prizes versus vouchers in cocaine-using methadone patients. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2007;75:983–991. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Martin B, Cooney JL, Kranzler HR. Give them prizes and they will come: contingency management treatment of alcohol dependence. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000;68:250–257. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Peirce JM, Stitzer ML, Blaine JD, Roll JM, Cohen A, Obert J, Killeen T, Saladin ME, Cowell M, Kirby KC, Sterling R, Royer-Malvestuto C, Hamilton J, Booth RE, Macdonald M, Liebert M, Rader L, Burns R, DiMaria J, Copersino ML, Stabile PO, Kolodner K, Li R, for the Clinical Trials Network Effect of prize-based incentives on outcomes in stimulant abusers in outpatient psychosocial treatment programs: a national drug abuse Clinical Trials Network study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2006;62:1148–1156. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Petrakis I, Trevisan L, Wiredu L, Boutros N, Martin B, Kosten TR. Contingency management interventions: from research to practice. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2001;20:33–44. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston KL, Silverman K, Schuster CR, Cone EJ. Assessment of cocaine use with quantitative urinalysis and estimation of new uses. Addiction. 1997;92:717–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigsby MO, Rosen MI, Beauvais J, Cramer JA, Rainey PM, O’Malley SS, Dieckhaus KD, Rounsaville BJ. Cue dose training with monetary reinforcement: pilot study of an antiretroviral adherence intervention. J. Gen. Int. Med. 2000;15:841–847. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.00127.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roache JD, Kahn R, Newton TF, Wallace CL, Murff WL, De La Garza R, 2nd, Rivera O, Anderson A, Mojsiak J, Elkashef A. A double-blind, placebo-controlled assessment of the safety of potential interactions between intravenous cocaine, ethanol, and oral disulfiram. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;119:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SM, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Leo GI. Reliability of the Timeline Followback for cocaine, cannabis, and cigarette use. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2012;28:154–162. doi: 10.1037/a0030992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applying Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurence. Oxford University Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen JL, Haug NA, Delucchi KL, Gruber V, Kletter E, Batki SL, Tulsky JP, Barnett P, Hall S. Voucher reinforcement improves medication adherence in HIV-positive methadone patients: a randomized trial. Drug. Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout RL, Wirtz PW, Carbonari JP, DelBoca FK. Ensuring balanced distribution of prognostic factors in treatment outcome research. J. Stud. Alcohol Suppl. 1994;12:70–75. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh JJ, Pettinati HM, Kampman KM, O’Brien CP. The status of disulfiram: a half of a century later. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2006;26:290–302. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000222512.25649.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young LM, Haakenson CM, Lee KK, van Eeckhout JP. Riboflavin use as a drug marker in Veterans Aministration Cooperative Studies. Control. Clin. Trials. 1984;5:497–504. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(84)90010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanis DA, McLellan AT, Randall M. Can you trust patient self-reports of drug use during treatment? Drug Alcohol Depend. 1994;35:127–132. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]