Abstract

The innate immune system is the first line of defense against invading pathogens. Innate immune cells recognize molecular patterns from the pathogen and mount a response to resolve the infection. The production of proinflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species, phagocytosis, and induced programmed cell death are processes initiated by innate immune cells in order to combat invading pathogens. However, pathogens have evolved various virulence mechanisms to subvert these responses. One strategy utilized by Gram-negative bacterial pathogens is the deployment of a complex machine termed the type III secretion system (T3SS). The T3SS is composed of a syringe-like needle structure and the effector proteins that are injected directly into a target host cell to disrupt a cellular response. The three human pathogenic Yersinia spp. (Y. pestis, Y. enterocolitica, and Y. pseudotuberculosis) are Gram-negative bacteria that share in common a 70 kb virulence plasmid which encodes the T3SS. Translocation of the Yersinia effector proteins (YopE, YopH, YopT, YopM, YpkA/YopO, and YopP/J) into the target host cell results in disruption of the actin cytoskeleton to inhibit phagocytosis, downregulation of proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine production, and induction of cellular apoptosis of the target cell. Over the past 25 years, studies on the Yersinia effector proteins have unveiled tremendous knowledge of how the effectors enhance Yersinia virulence. Recently, the long awaited crystal structure of YpkA has been solved providing further insights into the activation of the YpkA kinase domain. Multisite autophosphorylation by YpkA to activate its kinase domain was also shown and postulated to serve as a mechanism to bypass regulation by host phosphatases. In addition, novel Yersinia effector protein targets, such as caspase-1, and signaling pathways including activation of the inflammasome were identified. In this review, we summarize the recent discoveries made on Yersinia effector proteins and their contribution to Yersinia pathogenesis.

Keywords: Type III secretion, Yersinia, Effectors, Innate, Virulence

Core tip: The study of Yersinia type III secretion system effector proteins has provided critical insights into bacterial pathogenic strategies and host innate immune responses. Identification of the crystal structure of YpkA revealed how a bacterial effector can counteract phagocytosis at multiple levels including inhibition of actin polymerization by sequestering actin, inhibition of actin signaling molecules via both its kinase and dissociation-like inhibitor domains, and inhibition of actin-cytoskeletal components via phosphorylation. YpkA/YopO multisite autophosphorylation may allow YpkA/YopO to bypass regulation by host phosphatases and thus prolong its ability to interfere with phagocytosis. Additionally, an emerging theme is the role of caspases in anti-Yersinia host defenses.

INTRODUCTION

The Yersinia genus consists of Gram-negative coccobacilli or rod-shaped bacteria in which three are pathogenic to humans: Y. pestis, the causative agent of the plague, and the two enteric pathogens, Y. enterocolitica, and Y. pseudotuberculosis[1]. Infected fleas serve as a vector for the transmission of Y. pestis to humans. Alternatively, the pneumonic form of the plague can be transmitted from an infected individual to another person via aerosolized droplets. Y. enterocolitica and Y. pseudotuberculosis are transmitted through ingestion of contaminated food or water. Upon transmission, Y. pestis migrates to regional lymph nodes where it utilizes the type III secretion system (T3SS; see below) to evade host immune cells. In doing so, Y. pestis is capable of replicating extracellularly and causes bubonic plague. If the infection becomes systemic it can result in the septicemic and pneumonic forms of plague. Y. enterocolitica and Y. pseudotuberculosis also have a trophism for lymphoid tissue whereupon ingestion the pathogens cross the specialized epithelial M cells found in the ileal tract of the small intestine. Once across the epithelial tissue of the small intestine Y. enterocolitica and Y. pseudotuberculosis infect the underlying lymphoid tissue such as the Peyer’s patches and mesenteric lymph nodes resulting in gastrointestinal diseases[2]. Systemic infections by the two enteric Yersinia pathogens are rare in humans, but mouse infection models show colonization of other tissues such as the spleen and liver.

The T3SS is a virulence mechanism found in a wide array of Gram-negative bacteria that are pathogenic to mammals or plants, as well as in symbiotic bacteria of plants and insects[3]. The T3SS is composed of a needle-like syringe termed the injectisome and the effector proteins that are injected directly into a target host cell from the bacterium’s cytosol to disrupt, hijack, or mimic host signaling proteins. Although the T3SS may be used for different functions depending on the life cycle and infection process of the pathogenic bacteria, it is primarily used to subvert the host response to favor survival of the pathogen. Bacterial pathogens lacking the T3SS, expressing a translocation-defective T3SS, or expressing an effectorless T3SS are attenuated in vivo, and thus underscore the essential role of the T3SS to bacterial virulence.

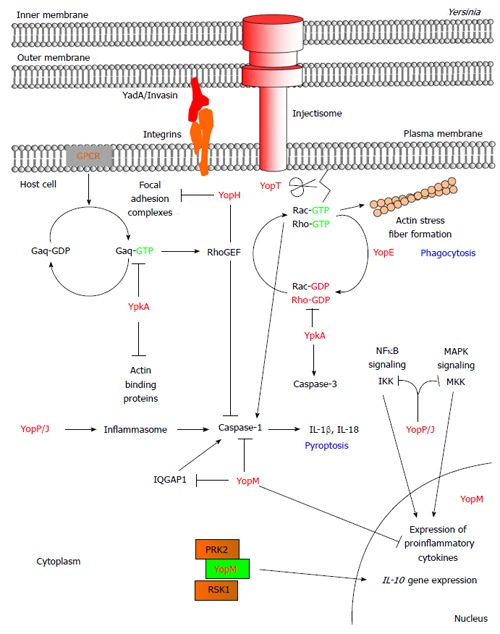

All three pathogenic Yersinia species share in common a 70 kb virulence plasmid that encodes proteins of the T3SS[4]. Expression of the proteins is observed at 37 °C under low Ca2+ concentration in vitro whereas in vivo it is also dependent on cellular contact of the Yersinia bacterium with the target host cell. Adhesion of the Yersinia bacterium to a target host cell is mediated through the binding of adhesion proteins such as invasin (Inv) and YadA to host cell surface proteins[5]. Once attached, the injectisome forms a pore at the plasma membrane of the host cell and subsequently translocates the effector proteins termed Yersinia outer proteins (Yops). There are 6 known Yop effector proteins that are translocated through the injectisome by pathogenic Yersinia species to disrupt the host response: YopE, YopH, YopT, YpkA (YopO in Y. enterocolitica), YopJ (YopP in Y. enterocolitica), and YopM (Table 1). Once in the target host cell these effector proteins function in concert to thwart the host response by altering the actin cytoskeletal structures to inhibit phagocytosis, as well as induce cell death and downregulate proinflammatory responses (Figure 1)[6].

Table 1.

The Yersinia effector proteins, their host substrates, and cellular effects

| Yop effectors | Enzymatic function | Target substrates | Cellular effects |

| YpkA/YopO | Serine/threonine kinase | Gαq, EVL, VASP, WASP, WIP, gelsolin, mDia1, INF2, and cofilin | Disruption of the actin cytoskeleton to contribute to inhibition of phagocytosis; additional effects are unknown |

| Guanine nucleotide dissociation-like inhibitor | RhoA, Rac1, and Rac2 | Disruption of the actin cytoskeleton to contribute to inhibition of phagocytosis | |

| YopE | GTPase activating protein | RhoA, Cdc42, Rac2, and RhoG | Disruption of the actin cytoskeleton to contribute to inhibition of phagocytosis; inhibition of caspase-1 activation and maturation of IL-18 and IL-1β |

| YopH | Protein tyrosine phosphatase | FAK, p130Cas, paxillin, Fyb, SKAP-HOM, PRAM-1, SLP-76, Vav, PLCγ2, p85, Gab1, Gab2, Lck, and LAT | Disruption of focal adhesion complexes and actin stress fibers to inhibit phagocytosis; inhibition of proinflammatory cytokine and MCP-1 production; inhibition of early calcium response and ROS production; inhibition of the PI3K/Akt pathway |

| YopP/J | Acetyltransferase/cysteine protease/deubiquintase | TRAF2, TRAF6, IκBα, MAPKKKs, MAPKKs, IKKβ, RICK, and eIF2α | Inhibition of adhesion molecules, proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine production; activation of caspase-1 and maturation of IL-18 and IL-1β; induction of apoptosis |

| YopT | Cysteine protease | RhoA, Rac1, Cdc42, and RhoG | Disruption of the actin cytoskeleton to contribute to inhibition of phagocytosis; inhibition of NFκB |

| YopM | Leucine-rich repeat protein | RSK and PRK isoforms, caspase-1, and IQGAP1 | Inhibition of proinflammatory cytokine production; inhibition of caspase-1 activation; induction of apoptosis; induction of anti-inflammatory cytokine production |

IL: Interleukin; FAK: Focal adhesion kinase; PLC-γ2: Phospholipase C-γ2; MAPK: Mitogen-activated protein kinase; MAPKK: MAPK kinase; MAPKKK: MAPKK kinase; Akt: Protein kinase B; NFκB: Nuclear factor kappa b; IKKβ: Inhibitor of kappa B kinase beta; IκBα: Inhibitor of kappa B alpha; IQGAP1: IQ motif containing GTPase activating protein 1; Lck: Lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase; LAT: Linker for activation of T cell; eIF2α: Eukaryotic initiation factor 2; PRK: Protein kinase C-related kinase; RSK: Ribosomal S6 protein kinase; VASP: Vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein; WASP: Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein; WIP: WASP-interacting protein; p130Cas: Crk associated tyrosine kinase substrate; Fyb: Fyn-binding protein; SKAP-HOM: Src kinase-associated phosphoprotein 55 homologue; PRAM-1: PML-retinoic acid receptor alpha regulated adaptor molecule 1; SLP-76: SH2 domain containing leukocyte protein of 76 kDa; EVL: Ena/VASP-like; INF2: Inverted formin 2; TRAF: TNF-receptor associated factor; RICK: Rip-like interacting caspase-like apoptosis-regulatory protein kinase; MCP-1: Monocyte chemotactic protein 1; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; PI3K: Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; mDia1: Mammalian diaphanous 1; Gab: Grb-associated-binder.

Figure 1.

Modulation of host signaling pathways by the Yersinia effector proteins. Pathogenic Yersinia utilizes the T3SS to subvert the host innate immune response. During an infection, the Yersinia bacterium adheres onto the target host cell by using adhesion proteins such as YadA and invasin to bind onto host β1 integrin. This enables the injectisome of the T3SS to form a pore at the host plasma membrane and the subsequent translocation of the Yersinia effector proteins directly into the cytoplasm. The Yersinia effector proteins localize to distinct subcellular locations where they mimic host proteins/functions to disrupt host signaling pathways. The Ser/Thr kinase YpkA binds actin monomers resulting in YpkA autophosphorylation and kinase activation. Upon GPCR activation of the host G protein Gαq, YpkA binds to and phosphorylates Gαq to inhibit Gαq-mediated activation of the Rho GTPases and subsequent actin stress fiber formation. YpkA also uses actin as bait for actin binding proteins (i.e., VASP, cofilin, and WASP) whereby YpkA then phosphorylates these proteins. In addition, YpkA binds onto the Rho GTPases, RhoA and Rac1, to inhibit the exchange of GDP for GTP. YopE is a GAP protein that facilitates the intrinsic GTPase activity of the Rho proteins resulting in their inactivation. The cysteine protease, YopT, disrupts the actin cytoskeleton by cleaving post-translationally modified Rho GTPases. Cleavage of the Rho proteins results in the mislocalization and inactivation of the Rho proteins. YopH, a PTPase, dephosphorylates focal adhesion components such as FAK, p130Cas, paxillin, Fyb, SKAP-HOM, PRAM-1, and SLP-76 to disrupt focal adhesion complexes, β1 integrin signaling, and activation of the Rho protein, Rac1. Together, the enzymatic activity of YpkA, YopE, YopT, and YopH affects organization of the actin cytoskeleton to inhibit phagocytosis. YopP/J is an acetyltransferase with deubiquitinase activity and a putative cysteine protease function. YopP/J targets signaling components of the MAPK and NFκB signaling pathways following activation of Toll-like receptor 4 to inhibit production of proinflammatory cytokines. In addition to inhibiting the MAPK and NFκB signaling pathways, YopP/J activates the inflammasome complex resulting in the maturation of caspase-1, the production of IL-1β and IL-18, and the cell death process termed pyroptosis. YopE and YopT were implicated in inhibiting inflammasome and caspase-1 activation by targeting Rac1. YopM is a protein with leucine-rich repeats that localizes to the cytoplasm and the nucleus of the cell. The translocation of YopM results in the inhibition of proinflammatory cytokine production. Cytoplasmically-localized YopM inhibits caspase-1 activity by binding to the upstream component, IQGAP1, to pro-caspase-1, or to mature caspase-1. YopM also binds onto the PRK and RSK isoforms and inhibits phosphatase-mediated deposphorylation of these two host kinases. The underlying function of targeting these two kinases by YopM is still unclear, but is linked to the production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10. T3SS: Type III secretion system; GPCR: G protein-coupled receptor; IL: Interleukin; FAK: Focal adhesion kinase; MAPK: Mitogen-activated protein kinase; NFκB: Nuclear factor kappa b; IQGAP1: IQ motif containing GTPase activating protein 1; PRK: Protein kinase C-related kinase; RSK: Ribosomal S6 protein kinase; GAP: GTPase activating protein; VASP: Vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein; WASP: Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein; p130Cas: Crk associated tyrosine kinase substrate; Fyb: Fyn-binding protein; SKAP-HOM: Src kinase-associated phosphoprotein 55 homologue; PRAM-1: PML-retinoic acid receptor alpha regulated adaptor molecule 1; SLP-76: SH2 domain containing leukocyte protein of 76 kDa.

Both the innate and adaptive immune systems mount a response to combat against invading pathogens with the former being the first line of defense[7]. Macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells, and natural killer (NK) cells are innate immune cells that respond to resolving the infection. Upon ligand binding by receptors such as pattern recognition receptors innate immune cells engage in phagocytosis, production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and induction of inflammation and cell death to combat the pathogen. All three Yersinia species are capable of downregulating innate immune responses to promote survival of the Yersinia pathogens. Cells of the innate immune system are also involved in activating the adaptive immune response, and thus highlight the significance of why pathogens evolved effective mechanisms to disarm the innate immune system.

Recent studies are unveiling new target substrates and signaling pathways that are inhibited by the Yersinia effector proteins. The discovery of the crystal structure of YpkA, the identification of multisite YpkA autophosphorylation to activate its kinase domain, and the establishment that YpkA phosphorylates actin-binding proteins are shedding light on YpkA and its molecular function within the host cell. Additionally recent findings emphasize the central role of caspases in anti-Yersinia host defenses. Yersinia effector proteins and their effects on the host innate immune response are the focus of this review. Although we will be focusing our discussions on findings within the past 5 years, we will also draw upon relevant studies performed in the prior years.

YERSINIA OUTER PROTEINS

YopH inhibits early response of innate immune cells to enhance Yersinia virulence

YopH is a 50 kDa protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTPase) containing an N-terminal substrate binding domain and a C-terminal PTPase domain[8,9]. Mouse infection studies showed that YopH is essential to enhance Yersinia virulence, especially at the early stages of an infection to evade innate immune cells[10-13]. Studies on YopH and its PTPase activity demonstrate that it inhibits phagocytosis by epithelial cells, macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells when working in concert with other Yops[10,14-19]. Translocation of YopH into these immune cells results in inhibition of the early calcium signaling and ROS production, as well as the production of some proinflammatory cytokines [tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin (IL)-10, and IL-1β] and the chemokine, monocyte chemotactic protein 1[18,20-22]. YopH was recently implicated to function in concert with YopE to inhibit integrin β1-mediated inflammasome activation in epithelial cells; however whether YopH also inhibits inflammasome activation in immune cells still remains to be determined[23].

YopH targets kinases and/or adapter proteins of innate immune cells

To date, it has been reported that YopH binds to and dephosphorylates the focal adhesion kinase (FAK), Crk associated tyrosine kinase substrate (p130Cas), and paxillin in epithelial cells whereas p130Cas, Fyn-binding protein, and SKAP-HOM are targeted in macrophages[17,24-26]. Although not discussed here, YopH also affects the adaptive immune system where it targets lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase, linker for activation of T cell, as well as SLP-76 in T-cells[27,28]. Interestingly, YopH only targets a subset of these proteins in a cell specific manner. Recently, the translocation of YopH was shown to directly or indirectly affect phosphorylation of the PRAM-1/SKAP-HOM and the SLP-76/Vav/phospholipase C-γ2 (PLC-γ2) signaling cascades in polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs)[21]. Moreover, the Grb-associated binder 1 and 2 (Gab1 and Gab2) adapter proteins, the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) subunit, p85, and the Vav adapter protein were shown to associate with recombinant YopH in a pulldown experiment. The dephosphorylation of the p85 subunit of PI3K by YopH accounts for the previously reported YopH-mediated dephosphorylation of PI3K to perturb PI3K-dependent chemokine production[22,29]. Interestingly, the p85 subunit of the PI3K protein complex (p85/p110) binds onto the Gab proteins enabling signal transduction through the PI3K signaling pathway following activation of the cell surface receptor[30]. Thus, YopH may exploit the Gab1, Gab2, and Vav adapter proteins in order to gain access to signaling molecules.

YopE facilitates GTPase activity of the Rho family of GTPases

YopE is a 23 kDa GTPase activating protein (GAP) that is translocated by Yersinia into the target host cell where it exerts its GAP activity on the Rho family of GTPases (for a review refer to[31]). YopE is essential to Yersinia virulence in vivo due to its effective ability to inhibit phagocytosis by innate immune cells[32]. Earlier findings showed that YopE stimulates the GTPase activity of RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42 in vitro; however the selective targeting of the Rho proteins in cellulo or in vivo depends on the cellular localization of YopE and the Rho proteins[31,33-36]. In addition to the well studied Rho GTPases, YopE also targets RhoG and Rac2[33,35,37]. Intriguingly, activation of a Rho GTPase can mediate the activation of another Rho protein, and thus YopE may be targeting multiple Rho GTPases at once to enhance Yersinia virulence.

YopE-mediated inhibition of the Rho GTPases also perturbs inflammasome activation and ROS production

The GAP activity of YopE on Rho proteins causes disruption of the actin cytoskeleton and inhibits phagocytosis; however, inactivating the Rho proteins also has other effects[38]. Thinwa et al[23] demonstrated that infection of epithelial cells with the YopE-deficient Y. enterocolitica mutant in part induces the maturation of caspase-1 and IL-18; a hallmark of inflammasome activation[39]. The discovery that YopE inhibits inflammasome activation is not new, but does corroborate the previously reported finding that YopE inhibits maturation of caspase-1 and caspase-1-mediated responses in macrophages[40].

Once in the lymphoid tissue Yersinia utilizes the T3SS to evade the host immune response. Infection of mice with a Y. pseudotuberculosis mutant strain deficient in expressing YopE showed higher association of Yersinia with PMNs one day post infection. Furthermore, the mutant can colonize and disseminate better in PMN-depleted mice[13]. The translocation of YopE into neutrophils enables Yersinia to thwart the neutrophil response. The inhibition of ROS production along with phagocytosis by YopE is crucial for Yersinia colonization of the spleen of infected mice[37]. Since Rac2 is primarily expressed in hematopoetic cells it is likely that YopE targets Rac2 in immune cells such as neutrophils to perturb the killing of Yersinia during an infection. Additionally, the YopE-mediated inhibition of RhoG was speculated to affect proper neutrophil functions since RhoG-/- murine neutrophils are deficient in proper ROS production when stimulated with different agonists[35,41]. Although the reported Rac2-dependent ROS production is independent of RhoG, the activation of Rac2 at the early time points upon agonist stimulation was affected in RhoG knockout neutrophils[37,41]. Thus, it appears that YopE may be targeting multiple signaling pathways in immune cells that mediate the production of ROS.

YopT targets the Rho family of GTPases

The cysteine protease, YopT, is a 35.5 kDa protein that is translocated into the target host cell by pathogenic Yersinia to target the Rho family of GTPases[42-44]. YopT is a member of the “CA” clan of cysteine proteases containing the conserved Cys, His, and Asp amino acids required for the catalytic activity of cysteine proteases[43]. The catalytic action of YopT was observed to act upon the post-translationally modified Rho GTPases where YopT cleaves upstream of the isoprenylated cysteine residue resulting in the mislocalization of the membrane-bound Rho protein, and the disruption of the actin cytoskeleton[45]. Unlike the other Yops, YopT is not found in all pathogenic Yersinia species namely in some serotypes of Y. pseudotuberculosis due to an internal deletion of the yopT gene. Thus, the molecular role of YopT is complemented by the other translocated Yops such as YopE in the yopT-deficient Yersinia strain as demonstrated in mouse infection studies[42,46]. Moreover, the inhibition of Rac1 by YopT and YopE inactivates caspase-1 suggesting an overlap of function between YopT and some of the other Yop effector(s)[40].

YopT has been demonstrated to play a role in inhibiting phagocytosis by macrophages and neutrophils, but not by dendritic cells[47]. The Rho GTPases are key signaling molecules involved in remodeling the actin cytoskeleton to mediate phagocytosis[48,49]. YopT has been shown to cleave the post-translationally modified RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42 in vitro[50]. However, the enzymatic activity of YopT appears to be more selective in targeting different Rho protein(s) depending on the cell type and subcellular localization of the Rho proteins[35,51]. In addition to targeting the well studied Rho proteins, YopT also cleaves membrane bound RhoG to inhibit RhoG-mediated uptake of Yersinia; however, since RhoG is also required for proper neutrophil functions, it remains to be tested whether YopT also affects other response mediated by RhoG in immune cells[35,41].

YopT induces expression of host’s KLF2 and GILZ to inhibit NFκB signaling

The translocation of YopT results in decreased IL-8 production suggesting that the catalytic activity of YopT on Rho proteins not only results in the disruption of the actin cytoskeleton, but also modifies the host transcriptional profile[22,46,52,53]. YopT was shown to mediate expression of the zinc-finger transcription factor, Kruppel-like factor 2 (KLF2), and the leucine zipper, glucocorticoid induced-leucine zipper (GILZ), in macrophages and/or epithelial cells upon infection with Yersinia[54,55]. In host cells both KLF2 and GILZ inhibit the NFκB signaling pathway to downregulate NFκB-mediated proinflammatory responses[56,57]. Thus, YopT usurps a normal host regulatory mechanism to counteract anti-Yersinia immune responses. However, it is still unclear at what stage(s) of Yersinia infection KLF2 and GILZ expression are required to promote Yersinia pathogenesis.

The multi-domains of YpkA/YopO

Yersinia protein kinase A (YpkA; YopO in Y. enterocolitica) is an 80 kDa serine/threonine (Ser/Thr) kinase that when translocated into the target cell causes disruption of the actin cytoskeleton[58]. Interestingly, YpkA is a multifaceted effector protein with regards to the functional eukaryotic-like enzymatic domains that include a Ser/Thr kinase domain and a guanine nucleotide dissociation-like inhibitor (GDI) domain[59,60]. YpkA is the only Yersinia effector protein with two enzymatic domains. Activities of both domains affect the actin cytoskeleton by targeting the activation state of the Rho GTPases, RhoA and Rac1. Rho GTPases cycle between an active GTP-bound and an inactive GDP-bound state where the former is catalyzed by guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) to exchange GDP for GTP. Active Rho proteins activate downstream effectors to remodel the actin cytoskeleton to regulate cellular processes such as phagocytosis[49]. The intrinsic Rho GTPase activity is facilitated by GAP that hydrolyze GTP resulting in the inactivation of the Rho proteins. Inactive Rho proteins are bound to GDI and are kept in an inactivate state. Similar to host GDI, the GDI domain of YpkA binds directly to the Rho GTPases to inhibit GTP loading whereas the kinase domain targets the alpha subunit of the heterotrimeric G protein complex, Gq, to inhibit activation of downstream Rho proteins by the LARG RhoGEF[60,61]. However, the YpkA GDI domain alone can mediate the disrupted actin cytoskeleton phenotype, and thus underscores the prediction that the kinase activity of YpkA also targets additional host signaling pathways (see below). Although mouse infection studies with Yersinia mutant strains expressing either a kinase inactive YpkA mutant or only the GDI domain controversially argue one domain being more essential than the other, these studies taken together suggest that both domains of YpkA contribute to Yersinia virulence[30,59,62,63].

The secretion/translocation domain of YpkA (Sec/Trans; amino acids 1-77) located at its N-terminus mediates translocation of YpkA into the host cell[64]. Intriguingly though, multiple regulatory domains also overlap with the Sec/Trans domain of YpkA. To date, the chaperone binding domain (amino acids 20-77), the membrane localization domain (MLD; amino acids 20-90), and the substrate-binding domain (SBD; amino acids 40-49) all overlap with the Sec/Trans domain[65,66]. Salomon et al[67] also showed that residues located within amino acids 1-125 of YpkA mediate binding to phosphoinositides to perhaps localize YpkA to the plasma membrane after being translocated. Altogether, the MLD, SBD, and phosphoinositide-binding residues may regulate an aspect of YpkA activity such as the phosphorylation of Gαq and/or the selective inhibition of Rho proteins. Downstream of these domains is the kinase domain (amino acids 150-400), the GDI domain (amino acids 431-612), and the actin binding domain (ABD; amino acids 709-729).

Kinase activation of YpkA and the targeting of actin regulating proteins

YpkA is expressed as an inactive kinase in the Yersinia bacterium[59]. The kinase activity of YpkA is activated by binding onto globular actin via the ABD upon translocation into the target cell[68]. The crystal structure of the Y. enterocolitica YopO-actin complex showed that actin binding allosterically positions the catalytic and activation loops of YpkA in an active conformation[69]. Actin binding induces YpkA autophosphorylation on Ser90 and Ser95 in vitro[59,66,68]. Interestingly, mutation of Ser90 and Ser95 to alanine on YpkA does not affect its kinase activity in cellulo whereas mutation of all serine residues on YpkA resulted in a catalytically inactive kinase[66]. Further analysis showed that mutation of all serine residues to alanine within amino acids 436-710 to alanine does not affect YpkA kinase activity in vitro or in cellulo. Moreover, mutation of serine residues to alanine within amino acids 1-150 or 150-400 results in decreased YpkA autophosphorylation in vitro, but has no effect on its kinase activity in cellulo; however, mutation of all serine residues to alanine within amino acids 1-400 results in an inactive YpkA kinase mutant[66]. Together, the results suggest that once translocated YpkA autophosphorylates on multiple serine residues within its N-terminus to activate its kinase domain. Additionally, due to the fact that YpkA is translocated at a lower level relative to other Yersinia effectors, it appears that the YpkA kinase activity has been fine tuned to where it can function efficiently within the target host cell by autophosphorylation on multiple serine residues[58]. It is predicted that this multisite autophosphorylation mechanism by YpkA enables it to bypass the regulatory control imposed by host proteins such as phosphatases.

YpkA-mediated phosphorylation of Gαq results in the inhibition of the Gαq signaling cascade[61]. Activation of Gαq and its effector, phospholipase C, regulates an array of cellular responses such as neuronal signaling, platelet aggregation, cell growth and proliferation, and development[70]. However, further study is still needed to establish the molecular contribution of YpkA-mediated inhibition of Gαq to Yersinia pathogenesis. Although it remains to be explored, YpkA may be targeting Gαq-mediated NFκB activation through the scaffolding protein, CARMA3. CARMA family members form a complex with Bcl10, MALT1, and TRAF6 to activate NFκB resulting in the induction of a proinflammatory response[71]. Alternatively, YpkA may be targeting Gαq to inhibit activation of the dual oxidase-dependent production of ROS[71,72]. The production of ROS is involved in mediating killing of pathogens by directly damaging the pathogen cellular components (i.e., DNA damage and amino acid modification), as well as indirectly by regulating responses such as phagosomal protease activity and immune signaling[73]. In addition to binding directly to Gαq to mediate phosphorylation, YpkA utilizes actin as bait to recruit the actin filament elongators (EVL and VASP), the formin proteins (mDia1 and INF2), the nucleation-promoting factors (WASP and WIP), the actin filament severing protein (gelsolin), and the actin depoylmerizing protein (cofilin) for phosphorylation in vitro[69]. Since all of these proteins are involved in regulating actin assembly and disassembly, these proteins are likely targeted by YpkA to inhibit some aspect of phagocytosis as reported for VASP[74]. An alternative mechanism of phagocytosis (also known as bacterial uptake) is activated by binding of the Yersinia adhesion proteins, Inv and YadA, to host β1 integrin. Subsequently, focal adhesion proteins and Rac1 signal downstream molecules to remodel the actin cytoskeleton resulting in uptake of Yersinia[1]. Uptake of E. coli expressing the YadA protein by human umbilical vein endothelial cells was inhibited by the kinase activity of YpkA[68]. Phosphorylation of proteins regulating actin polymerization by YpkA may be responsible for the inhibition of bacterial uptake via the YadA-β1 integrin signaling pathway.

YpkA inhibits the Rac GTPases

Early studies on YpkA identified the Rho GTPases as target substrates of the YpkA GDI domain where binding of YpkA to RhoA and Rac1 inhibits their activation[60,75,76]. Moreover, phagocytosis of opsonized sheep red blood cells (IgG-sRBC) by COS-7 cells expressing the Fcγ receptor showed that YpkA localizes to phagocytic cups and inhibits phagocytosis[77]. This is achieved through the selective inhibition of Rac1 by the GDI domain of YpkA suggesting that once translocated into innate immune cells YpkA inhibits Fcγ receptor-mediated phagocytosis. Interestingly, the Rac2 isoform was also identified as an interacting partner of YpkA[69,77]. Rac2 is primarily expressed in hematopoietic cells at varying levels depending on the immune cell type and is involved in activation of the NADPH oxidase to produce ROS, as well as phagocytosis[78]. Thus, it is tempting to suggest that aside from targeting Rac1 for inhibition YpkA also inhibits Rac2 activity in immune cells. Additionally, the Rac1- and Rac2-regulated protein, PLC-γ2 isoform, was identified as an interacting partner with the YopO-actin complex[69,79]. This further supports the speculation that YpkA also targets Rac2 signaling in immune cells.

The many target substrates of YopP/J

YopJ (YopP in Y. enterocolitica) is a 34 kDa acetyltransferase with a deubiquitinating and putative cysteine protease function which was previously shown to inhibit production of proinflammatory molecules. YopP/J suppresses a proinflammatory response by interfering with the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and NFκB signaling pathways[80-84]. More recently, YopJ was reported to acetylate the MAPKK kinase family member, TAK1, and the Ser/Thr kinase, RICK, to inhibit their activity[85,86]. Production of chemoattractants (KC, MIP-2, and G-CSF) and adhesion molecules are also effected by YopP/J presumably to inhibit the early recruitment of neutrophils to the site of infection; however, inhibition of chemoattractant expression levels in vivo may involve the function of other Yop effectors[87-89]. Moreover, the YopJ homolog, YopP, of Y. enterocolitica inhibits phosphorylation of the Tyk2 kinase and STAT4 of the Jak-STAT signaling pathway through a yet-to-be identified mechanism[90]. Of all the effectors that Yersinia translocates, it should be noted that YopP/J translocates at various amounts depending on the Yersinia strain which reflects its associated cytotoxicity[87,91,92]. This was further seen in studies conducted with different concentrations of recombinant YopJ[93-95].

YopP/J induces apoptosis through caspase-8

Similar to what was observed with extracellular Yersinia, translocation of YopJ by intracellular Yersinia induces apoptosis of macrophages[96]. Apoptosis is a process initiated by an extracellular “death” signal (extrinsic pathway) or an intracellular signal (intrinsic pathway) that converges on the mitochondria and the release of cytochrome C. The extrinsic and intrinsic pathway involve the activation of caspase-8 or caspase-9, respectively, and the subsequent processing of the effector caspases (e.g. caspase-3) to induce apoptosis[97]. YopP/J-mediated inhibition of the MAPK and NFκB signaling pathways, along with Toll-like receptor 4 signaling, induces apoptosis of macrophages and dendritic cells[98-102]. This reported YopJ-induced cellular apoptosis was shown to be a result of signal transduction via the receptor-interacting Ser/Thr kinase 1 (RIPK1), Fas-associated death domain and caspase-8 signaling cascade to induce apoptosis[103,104]. Additionally, activated caspase-8 mediates the maturation of the inflammasome-associated caspase-1[103,104]. Although inflammasome activation triggers the cell death process termed pyroptosis, YopJ-induced cell death is primarily through caspase-8-induced apoptosis[105,106]. However, in contrast to the experimental findings reported, YopJ-mediated activation of caspase-1 was observed in cells undergoing necrosis[107]. Since activated RIPK3 is downstream of RIPK1, and is the signaling molecule that triggers programmed necrosis termed necroptosis, it is likely the candidate for the observed necrosis[107,108]. In support of this is the evidence that YopJ-mediated activation of caspase-8 suppresses RIPK3 induced necrosis[103,104]. Thus, there appears to be an intimate crosstalk between caspase-8 and RIPK3 in determining the fate of a Yersinia infected cell containing YopP/J.

YopP/J utilizes host signaling pathways to promote Yersinia virulence

YopP/J activity affects macrophages, dendritic cells, NK cells, and to varying degrees neutrophils[90,98,109-111]. However, activity of YopP/J in vivo varies depending on the Yersinia strain, YopP/J variant, experimental parameters, and infection model[62,92,112-115]. Nevertheless, translocation of YopP/J results in the inhibition of key signaling pathways that mediate a proinflammatory response, and also induces production of specific cytokines[83,89,116-118]. In particular is the well established observation that YopJ activity on the MAPK and NFκB signaling pathways mediates the maturation of caspase-1[98,103-105]. Activated caspase-1 cleaves pro-IL-18 and pro-IL-1β to produce active IL-18 and IL-1β[39]. Studies using RIPK3/caspase-8 knockout mice showed reduced cytokine production in response to Yersinia infection, and thus, underscores the crucial role of caspase-8 and caspase-1 in mediating a host response to Yersinia when the MAPK and NFκB signaling pathways are inhibited[103,104]. Why would Yersinia utilize YopJ to induce the activation of caspase-8 and caspase-1? Is it a mechanism evolved by the host to counteract a Yersinia infection when the MAPK and NFκB signaling pathways are inhibited, or is it a virulence strategy employed by Yersinia? Recent studies are alluding to both situations being the case and are dependent on the association of caspase-1 with inflammasome components, NLRP12, NLRP3/ASC or NOD2[85,106,111]. Thus, although the functions of IL-18 and IL-1β induce an anti-Yersinia response, Yersinia may also exploit the normal functions of these cytokines at certain stages of infection to promote Yersinia virulence. YopJ was also linked to the inhibition of the host alpha subunit of the eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2α). Although the underlying mechanism and biological relevance is still unclear, modulating eIF2α activity by YopJ results in an increased cellular invasion of MEF cells by Yersinia and decreased cytokine production[119].

YopM is indispensable to Yersinia virulence

YopM is a leucine-rich repeat (LRR) protein that localizes to both the cytoplasm and the nucleus of the target host cell upon translocation[120,121]. The molecular contribution of YopM to Yersinia pathogenesis is still unclear; however, it has been shown to target immune cells to effect different immune cell populations of the spleen and liver of infected mice, downregulate proinflammatory responses, and upregulate the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10[122-125]. IL-10 downregulates the production of proinflammatory cytokines by multiple innate immune cells, as well as regulates T cell function and proliferation[126]. The production of IL-10 was proposed to counteract the PMN response against Yersinia; however whether YopM is solely responsible for inducing production of IL-10 remains to be further explored[124]. YopM was also shown to inhibit platelet aggregation[127]. Although YopM is required to enhance Yersinia virulence in mouse infection models, varying results suggest that the route of infection and mouse strain used affects the reported contribution of YopM to Yersinia pathogenesis[122]. Moreover, this could also be attributed to the LRR motifs of the YopM variants, as well as the natural route of infection of the pathogenic Yersinia species.

YopM targets extra- and intracellular host proteins

Of the six effectors that are translocated by the T3SS of the pathogenic Yersinia species into the target host cell, YopM has been shown to also be secreted into the extracellular matrix where it binds α-thrombin and α1-antitrypsin[128-130]. Extracellular YopM can also penetrate culture cells[131]. Whether YopM enters the target host cells by crossing the lipid bilayer or via the T3SS it targets the ribosomal S6 protein kinase (RSK) and the protein kinase C-related kinase (PRK) isoforms[132,133]. Dephosphorylation of the RSK isoforms by phosphatase was inhibited by YopM in cellulo and in vitro[134]. The YopM mutant variant of Y. pseudotuberculosis 32777 that is defective in binding RSK1 and PRK2 was unable to induce IL-10 production[133]. More recently, YopM has been shown to inhibit the activity of mature caspase-1. This is achieved by the binding of YopM to the substrate-binding site of caspase-1, inhibition of recruitment of pro-caspase-1 to the inflammasome complex, and/or by targeting the scaffold protein, IQ motif containing GAP 1 (IQGAP1), which is known to activate caspase-1[135,136]. Moreover, YopM has also been shown to activate caspase-3 to presumably induce apoptosis of PMNs and/or macrophages in the liver of infected mice, and thus promote Yersinia virulence[137].

CONCLUSION

A major theme emerging from studies of the Yersinia effector proteins is the important role caspases play in host anti-Yersinia defenses. In particular are the effects of the Yersinia effector proteins on caspase-1 activity. Upon the detection of a pathogen by innate immune cells, the inflammasome complex is activated by the oligomerization of nucleotide-binding domain and LRR- containing (NLR) family of proteins. The caspase activation and recruitment domain found on NLRs or an associated adaptor protein such as ASC then recruits pro-caspase-1. Subsequently, autoproteolytic cleavage of pro-caspase-1 is induced to produce the mature caspase-1 form. Mature caspase-1 then mediates the maturation of IL-1β and IL-18, as well as induces pyroptosis. The targeting of Rac1 by YopE and YopT inhibits maturation of caspase-1 whereas the binding of IQGAP1, pro-caspase-1, and caspase-1 by YopM inhibits inflammasome activation, or the enzymatic function of caspase-1. Moreover, the dephosphorylation of FAK by YopH inhibits caspase-1 activation in epithelial cells which suggests that YopH also inhibits caspase-1 activity when translocated into innate immune cells. Alternatively, YopP/J was shown to activate caspase-1 through inflammasome activation, as well as the extrinsic cell death pathway. Whether this is beneficial or detrimental to Yersinia pathogenesis depends on the stage of infection; however, the kinetics of caspase-1 activation in the presence of multiple Yersinia effector proteins requires further exploration. An additional translocated Yop protein, YopK, which is involved in regulating translocation of the Yersinia effector proteins also inhibits inflammasome activation (for a review on YopK refer to[138]. Lastly, although YpkA has not been shown to affect caspase-1 activation or its activity, a study has shown that YpkA induces cellular apoptosis of murine macrophages through the intrinsic pathway which activates caspase-3[139]. Altogether, the Yersinia effector proteins effectively enable pathogenic Yersinia spp. to thwart the host innate immune response by regulating some aspect of programmed cell death, as well as inhibit the induction of proinflammatory cytokine production and phagocytosis. Future studies may lead to the identification of novel targets for the Yersinia effector proteins and thus additional targets for therapeutic interventions.

Footnotes

Supported by The ASM Robert D Watkins Graduate Fellowship and UC Davis Hellman Fellowship.

Conflict-of-interest statement: Authors declare no conflict of interests for this article.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: June 25, 2015

First decision: August 16, 2015

Article in press: November 4, 2015

P- Reviewer: Freire-De-Lima CG, Rangel-Corona R S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Jiao XK

References

- 1.Fällman M, Gustavsson A. Cellular mechanisms of bacterial internalization counteracted by Yersinia. Int Rev Cytol. 2005;246:135–188. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(05)46004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mowat AM. Anatomical basis of tolerance and immunity to intestinal antigens. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:331–341. doi: 10.1038/nri1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.He SY, Nomura K, Whittam TS. Type III protein secretion mechanism in mammalian and plant pathogens. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1694:181–206. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cornelis GR. The Yersinia Ysc-Yop ‘type III’ weaponry. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:742–752. doi: 10.1038/nrm932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mikula KM, Kolodziejczyk R, Goldman A. Yersinia infection tools-characterization of structure and function of adhesins. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:169. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Navarro L, Alto NM, Dixon JE. Functions of the Yersinia effector proteins in inhibiting host immune responses. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005;8:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medzhitov R, Janeway C. Innate immunity. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:338–344. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008033430506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Black DS, Montagna LG, Zitsmann S, Bliska JB. Identification of an amino-terminal substrate-binding domain in the Yersinia tyrosine phosphatase that is required for efficient recognition of focal adhesion targets. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:1263–1274. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Montagna LG, Ivanov MI, Bliska JB. Identification of residues in the N-terminal domain of the Yersinia tyrosine phosphatase that are critical for substrate recognition. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:5005–5011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009045200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bliska JB, Guan KL, Dixon JE, Falkow S. Tyrosine phosphate hydrolysis of host proteins by an essential Yersinia virulence determinant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1187–1191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bölin I, Wolf-Watz H. The plasmid-encoded Yop2b protein of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is a virulence determinant regulated by calcium and temperature at the level of transcription. Mol Microbiol. 1988;2:237–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1988.tb00025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Logsdon LK, Mecsas J. Requirement of the Yersinia pseudotuberculosis effectors YopH and YopE in colonization and persistence in intestinal and lymph tissues. Infect Immun. 2003;71:4595–4607. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.8.4595-4607.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Westermark L, Fahlgren A, Fällman M. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis efficiently escapes polymorphonuclear neutrophils during early infection. Infect Immun. 2014;82:1181–1191. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01634-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adkins I, Köberle M, Gröbner S, Bohn E, Autenrieth IB, Borgmann S. Yersinia outer proteins E, H, P, and T differentially target the cytoskeleton and inhibit phagocytic capacity of dendritic cells. Int J Med Microbiol. 2007;297:235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersson K, Magnusson KE, Majeed M, Stendahl O, Fällman M. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis-induced calcium signaling in neutrophils is blocked by the virulence effector YopH. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2567–2574. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2567-2574.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fahlgren A, Westermark L, Akopyan K, Fällman M. Cell type-specific effects of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis virulence effectors. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11:1750–1767. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Persson C, Carballeira N, Wolf-Watz H, Fällman M. The PTPase YopH inhibits uptake of Yersinia, tyrosine phosphorylation of p130Cas and FAK, and the associated accumulation of these proteins in peripheral focal adhesions. EMBO J. 1997;16:2307–2318. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.9.2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Persson C, Nordfelth R, Andersson K, Forsberg A, Wolf-Watz H, Fällman M. Localization of the Yersinia PTPase to focal complexes is an important virulence mechanism. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:828–838. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosqvist R, Bölin I, Wolf-Watz H. Inhibition of phagocytosis in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis: a virulence plasmid-encoded ability involving the Yop2b protein. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2139–2143. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.8.2139-2143.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cantwell AM, Bubeck SS, Dube PH. YopH inhibits early pro-inflammatory cytokine responses during plague pneumonia. BMC Immunol. 2010;11:29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-11-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rolán HG, Durand EA, Mecsas J. Identifying Yersinia YopH-targeted signal transduction pathways that impair neutrophil responses during in vivo murine infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:306–317. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sauvonnet N, Lambermont I, van der Bruggen P, Cornelis GR. YopH prevents monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 expression in macrophages and T-cell proliferation through inactivation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway. Mol Microbiol. 2002;45:805–815. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thinwa J, Segovia JA, Bose S, Dube PH. Integrin-mediated first signal for inflammasome activation in intestinal epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2014;193:1373–1382. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Black DS, Bliska JB. Identification of p130Cas as a substrate of Yersinia YopH (Yop51), a bacterial protein tyrosine phosphatase that translocates into mammalian cells and targets focal adhesions. EMBO J. 1997;16:2730–2744. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Black DS, Marie-Cardine A, Schraven B, Bliska JB. The Yersinia tyrosine phosphatase YopH targets a novel adhesion-regulated signalling complex in macrophages. Cell Microbiol. 2000;2:401–414. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2000.00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamid N, Gustavsson A, Andersson K, McGee K, Persson C, Rudd CE, Fällman M. YopH dephosphorylates Cas and Fyn-binding protein in macrophages. Microb Pathog. 1999;27:231–242. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1999.0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alonso A, Bottini N, Bruckner S, Rahmouni S, Williams S, Schoenberger SP, Mustelin T. Lck dephosphorylation at Tyr-394 and inhibition of T cell antigen receptor signaling by Yersinia phosphatase YopH. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:4922–4928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308978200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerke C, Falkow S, Chien YH. The adaptor molecules LAT and SLP-76 are specifically targeted by Yersinia to inhibit T cell activation. J Exp Med. 2005;201:361–371. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de la Puerta ML, Trinidad AG, del Carmen Rodríguez M, Bogetz J, Sánchez Crespo M, Mustelin T, Alonso A, Bayón Y. Characterization of new substrates targeted by Yersinia tyrosine phosphatase YopH. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sármay G, Angyal A, Kertész A, Maus M, Medgyesi D. The multiple function of Grb2 associated binder (Gab) adaptor/scaffolding protein in immune cell signaling. Immunol Lett. 2006;104:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2005.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aepfelbacher M, Roppenser B, Hentschke M, Ruckdeschel K. Activity modulation of the bacterial Rho GAP YopE: an inspiration for the investigation of mammalian Rho GAPs. Eur J Cell Biol. 2011;90:951–954. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosqvist R, Forsberg A, Rimpiläinen M, Bergman T, Wolf-Watz H. The cytotoxic protein YopE of Yersinia obstructs the primary host defence. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:657–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aili M, Isaksson EL, Hallberg B, Wolf-Watz H, Rosqvist R. Functional analysis of the YopE GTPase-activating protein (GAP) activity of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:1020–1033. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Black DS, Bliska JB. The RhoGAP activity of the Yersinia pseudotuberculosis cytotoxin YopE is required for antiphagocytic function and virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:515–527. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohammadi S, Isberg RR. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis virulence determinants invasin, YopE, and YopT modulate RhoG activity and localization. Infect Immun. 2009;77:4771–4782. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00850-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roppenser B, Röder A, Hentschke M, Ruckdeschel K, Aepfelbacher M. Yersinia enterocolitica differentially modulates RhoG activity in host cells. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:696–705. doi: 10.1242/jcs.040345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Songsungthong W, Higgins MC, Rolán HG, Murphy JL, Mecsas J. ROS-inhibitory activity of YopE is required for full virulence of Yersinia in mice. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12:988–1001. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01448.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aili M, Hallberg B, Wolf-Watz H, Rosqvist R. GAP activity of Yersinia YopE. Methods Enzymol. 2002;358:359–370. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)58102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.von Moltke J, Ayres JS, Kofoed EM, Chavarría-Smith J, Vance RE. Recognition of bacteria by inflammasomes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31:73–106. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schotte P, Denecker G, Van Den Broeke A, Vandenabeele P, Cornelis GR, Beyaert R. Targeting Rac1 by the Yersinia effector protein YopE inhibits caspase-1-mediated maturation and release of interleukin-1beta. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25134–25142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401245200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Condliffe AM, Webb LM, Ferguson GJ, Davidson K, Turner M, Vigorito E, Manifava M, Chilvers ER, Stephens LR, Hawkins PT. RhoG regulates the neutrophil NADPH oxidase. J Immunol. 2006;176:5314–5320. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.9.5314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iriarte M, Cornelis GR. YopT, a new Yersinia Yop effector protein, affects the cytoskeleton of host cells. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:915–929. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shao F, Merritt PM, Bao Z, Innes RW, Dixon JE. A Yersinia effector and a Pseudomonas avirulence protein define a family of cysteine proteases functioning in bacterial pathogenesis. Cell. 2002;109:575–588. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00766-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zumbihl R, Aepfelbacher M, Andor A, Jacobi CA, Ruckdeschel K, Rouot B, Heesemann J. The cytotoxin YopT of Yersinia enterocolitica induces modification and cellular redistribution of the small GTP-binding protein RhoA. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:29289–29293. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.41.29289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shao F, Vacratsis PO, Bao Z, Bowers KE, Fierke CA, Dixon JE. Biochemical characterization of the Yersinia YopT protease: cleavage site and recognition elements in Rho GTPases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:904–909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252770599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Viboud GI, Mejía E, Bliska JB. Comparison of YopE and YopT activities in counteracting host signalling responses to Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:1504–1515. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grosdent N, Maridonneau-Parini I, Sory MP, Cornelis GR. Role of Yops and adhesins in resistance of Yersinia enterocolitica to phagocytosis. Infect Immun. 2002;70:4165–4176. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4165-4176.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Caron E, Hall A. Identification of two distinct mechanisms of phagocytosis controlled by different Rho GTPases. Science. 1998;282:1717–1721. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5394.1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Groves E, Dart AE, Covarelli V, Caron E. Molecular mechanisms of phagocytic uptake in mammalian cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:1957–1976. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7578-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fueller F, Schmidt G. The polybasic region of Rho GTPases defines the cleavage by Yersinia enterocolitica outer protein T (YopT) Protein Sci. 2008;17:1456–1462. doi: 10.1110/ps.035386.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aepfelbacher M, Trasak C, Wilharm G, Wiedemann A, Trulzsch K, Krauss K, Gierschik P, Heesemann J. Characterization of YopT effects on Rho GTPases in Yersinia enterocolitica-infected cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:33217–33223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303349200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bohn E, Müller S, Lauber J, Geffers R, Speer N, Spieth C, Krejci J, Manncke B, Buer J, Zell A, et al. Gene expression patterns of epithelial cells modulated by pathogenicity factors of Yersinia enterocolitica. Cell Microbiol. 2004;6:129–141. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hoffmann R, van Erp K, Trülzsch K, Heesemann J. Transcriptional responses of murine macrophages to infection with Yersinia enterocolitica. Cell Microbiol. 2004;6:377–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dach K, Zovko J, Hogardt M, Koch I, van Erp K, Heesemann J, Hoffmann R. Bacterial toxins induce sustained mRNA expression of the silencing transcription factor klf2 via inactivation of RhoA and Rhophilin 1. Infect Immun. 2009;77:5583–5592. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00121-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Köberle M, Göppel D, Grandl T, Gaentzsch P, Manncke B, Berchtold S, Müller S, Lüscher B, Asselin-Labat ML, Pallardy M, et al. Yersinia enterocolitica YopT and Clostridium difficile toxin B induce expression of GILZ in epithelial cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40730. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ayroldi E, Migliorati G, Bruscoli S, Marchetti C, Zollo O, Cannarile L, D’Adamio F, Riccardi C. Modulation of T-cell activation by the glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper factor via inhibition of nuclear factor kappaB. Blood. 2001;98:743–753. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.3.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Das H, Kumar A, Lin Z, Patino WD, Hwang PM, Feinberg MW, Majumder PK, Jain MK. Kruppel-like factor 2 (KLF2) regulates proinflammatory activation of monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:6653–6658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508235103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Håkansson S, Galyov EE, Rosqvist R, Wolf-Watz H. The Yersinia YpkA Ser/Thr kinase is translocated and subsequently targeted to the inner surface of the HeLa cell plasma membrane. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:593–603. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.5251051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Galyov EE, Håkansson S, Forsberg A, Wolf-Watz H. A secreted protein kinase of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is an indispensable virulence determinant. Nature. 1993;361:730–732. doi: 10.1038/361730a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Prehna G, Ivanov MI, Bliska JB, Stebbins CE. Yersinia virulence depends on mimicry of host Rho-family nucleotide dissociation inhibitors. Cell. 2006;126:869–880. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Navarro L, Koller A, Nordfelth R, Wolf-Watz H, Taylor S, Dixon JE. Identification of a molecular target for the Yersinia protein kinase A. Mol Cell. 2007;26:465–477. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Galyov EE, Håkansson S, Wolf-Watz H. Characterization of the operon encoding the YpkA Ser/Thr protein kinase and the YopJ protein of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4543–4548. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.15.4543-4548.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wiley DJ, Nordfeldth R, Rosenzweig J, DaFonseca CJ, Gustin R, Wolf-Watz H, Schesser K. The Ser/Thr kinase activity of the Yersinia protein kinase A (YpkA) is necessary for full virulence in the mouse, mollifying phagocytes, and disrupting the eukaryotic cytoskeleton. Microb Pathog. 2006;40:234–243. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cornelis GR, Boland A, Boyd AP, Geuijen C, Iriarte M, Neyt C, Sory MP, Stainier I. The virulence plasmid of Yersinia, an antihost genome. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1315–1352. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1315-1352.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Letzelter M, Sorg I, Mota LJ, Meyer S, Stalder J, Feldman M, Kuhn M, Callebaut I, Cornelis GR. The discovery of SycO highlights a new function for type III secretion effector chaperones. EMBO J. 2006;25:3223–3233. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pha K, Wright ME, Barr TM, Eigenheer RA, Navarro L. Regulation of Yersinia protein kinase A (YpkA) kinase activity by multisite autophosphorylation and identification of an N-terminal substrate-binding domain in YpkA. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:26167–26177. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.601153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Salomon D, Guo Y, Kinch LN, Grishin NV, Gardner KH, Orth K. Effectors of animal and plant pathogens use a common domain to bind host phosphoinositides. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2973. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Trasak C, Zenner G, Vogel A, Yüksekdag G, Rost R, Haase I, Fischer M, Israel L, Imhof A, Linder S, et al. Yersinia protein kinase YopO is activated by a novel G-actin binding process. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:2268–2277. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610071200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee WL, Grimes JM, Robinson RC. Yersinia effector YopO uses actin as bait to phosphorylate proteins that regulate actin polymerization. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22:248–255. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wettschureck N, Offermanns S. Mammalian G proteins and their cell type specific functions. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:1159–1204. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00003.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Blonska M, Lin X. NF-κB signaling pathways regulated by CARMA family of scaffold proteins. Cell Res. 2011;21:55–70. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ha EM, Lee KA, Park SH, Kim SH, Nam HJ, Lee HY, Kang D, Lee WJ. Regulation of DUOX by the Galphaq-phospholipase Cbeta-Ca2+ pathway in Drosophila gut immunity. Dev Cell. 2009;16:386–397. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Paiva CN, Bozza MT. Are reactive oxygen species always detrimental to pathogens? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:1000–1037. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ke Y, Tan Y, Wei N, Yang F, Yang H, Cao S, Wang X, Wang J, Han Y, Bi Y, et al. Yersinia protein kinase A phosphorylates vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein to modify the host cytoskeleton. Cell Microbiol. 2015;17:473–485. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Barz C, Abahji TN, Trülzsch K, Heesemann J. The Yersinia Ser/Thr protein kinase YpkA/YopO directly interacts with the small GTPases RhoA and Rac-1. FEBS Lett. 2000;482:139–143. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dukuzumuremyi JM, Rosqvist R, Hallberg B, Akerström B, Wolf-Watz H, Schesser K. The Yersinia protein kinase A is a host factor inducible RhoA/Rac-binding virulence factor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:35281–35290. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003009200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Groves E, Rittinger K, Amstutz M, Berry S, Holden DW, Cornelis GR, Caron E. Sequestering of Rac by the Yersinia effector YopO blocks Fcgamma receptor-mediated phagocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:4087–4098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.071035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yamauchi A, Kim C, Li S, Marchal CC, Towe J, Atkinson SJ, Dinauer MC. Rac2-deficient murine macrophages have selective defects in superoxide production and phagocytosis of opsonized particles. J Immunol. 2004;173:5971–5979. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.10.5971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kadamur G, Ross EM. Mammalian phospholipase C. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013;75:127–154. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mittal R, Peak-Chew SY, McMahon HT. Acetylation of MEK2 and I kappa B kinase (IKK) activation loop residues by YopJ inhibits signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:18574–18579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608995103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mukherjee S, Keitany G, Li Y, Wang Y, Ball HL, Goldsmith EJ, Orth K. Yersinia YopJ acetylates and inhibits kinase activation by blocking phosphorylation. Science. 2006;312:1211–1214. doi: 10.1126/science.1126867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Orth K, Xu Z, Mudgett MB, Bao ZQ, Palmer LE, Bliska JB, Mangel WF, Staskawicz B, Dixon JE. Disruption of signaling by Yersinia effector YopJ, a ubiquitin-like protein protease. Science. 2000;290:1594–1597. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5496.1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sweet CR, Conlon J, Golenbock DT, Goguen J, Silverman N. YopJ targets TRAF proteins to inhibit TLR-mediated NF-kappaB, MAPK and IRF3 signal transduction. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:2700–2715. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhou H, Monack DM, Kayagaki N, Wertz I, Yin J, Wolf B, Dixit VM. Yersinia virulence factor YopJ acts as a deubiquitinase to inhibit NF-kappa B activation. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1327–1332. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Meinzer U, Barreau F, Esmiol-Welterlin S, Jung C, Villard C, Léger T, Ben-Mkaddem S, Berrebi D, Dussaillant M, Alnabhani Z, et al. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis effector YopJ subverts the Nod2/RICK/TAK1 pathway and activates caspase-1 to induce intestinal barrier dysfunction. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11:337–351. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Paquette N, Conlon J, Sweet C, Rus F, Wilson L, Pereira A, Rosadini CV, Goutagny N, Weber AN, Lane WS, et al. Serine/threonine acetylation of TGFβ-activated kinase (TAK1) by Yersinia pestis YopJ inhibits innate immune signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:12710–12715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008203109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Denecker G, Tötemeyer S, Mota LJ, Troisfontaines P, Lambermont I, Youta C, Stainier I, Ackermann M, Cornelis GR. Effect of low- and high-virulence Yersinia enterocolitica strains on the inflammatory response of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Infect Immun. 2002;70:3510–3520. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.7.3510-3520.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Vagima Y, Zauberman A, Levy Y, Gur D, Tidhar A, Aftalion M, Shafferman A, Mamroud E. Circumventing Y. pestis Virulence by Early Recruitment of Neutrophils to the Lungs during Pneumonic Plague. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004893. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhou L, Tan A, Hershenson MB. Yersinia YopJ inhibits pro-inflammatory molecule expression in human bronchial epithelial cells. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2004;140:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Koch I, Dach K, Heesemann J, Hoffmann R. Yersinia enterocolitica inactivates NK cells. Int J Med Microbiol. 2013;303:433–442. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zauberman A, Cohen S, Mamroud E, Flashner Y, Tidhar A, Ber R, Elhanany E, Shafferman A, Velan B. Interaction of Yersinia pestis with macrophages: limitations in YopJ-dependent apoptosis. Infect Immun. 2006;74:3239–3250. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00097-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhang Y, Bliska JB. YopJ-promoted cytotoxicity and systemic colonization are associated with high levels of murine interleukin-18, gamma interferon, and neutrophils in a live vaccine model of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection. Infect Immun. 2010;78:2329–2341. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00094-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pandey AK, Sodhi A. Recombinant YopJ induces apoptosis in murine peritoneal macrophages in vitro: involvement of mitochondrial death pathway. Int Immunol. 2009;21:1239–1249. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxp086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pandey AK, Sodhi A. Recombinant YopJ induces apoptotic cell death in macrophages through TLR2. Mol Immunol. 2011;48:392–398. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sodhi A, Pandey AK. In vitro activation of murine peritoneal macrophages by recombinant YopJ: production of nitric oxide, proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Immunobiology. 2011;216:358–366. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zhang Y, Romanov G, Bliska JB. Type III secretion system-dependent translocation of ectopically expressed Yop effectors into macrophages by intracellular Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2011;79:4322–4331. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05396-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jin Z, El-Deiry WS. Overview of cell death signaling pathways. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4:139–163. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.2.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gröbner S, Adkins I, Schulz S, Richter K, Borgmann S, Wesselborg S, Ruckdeschel K, Micheau O, Autenrieth IB. Catalytically active Yersinia outer protein P induces cleavage of RIP and caspase-8 at the level of the DISC independently of death receptors in dendritic cells. Apoptosis. 2007;12:1813–1825. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0100-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gröbner S, Schulz S, Soldanova I, Gunst DS, Waibel M, Wesselborg S, Borgmann S, Autenrieth IB. Absence of Toll-like receptor 4 signaling results in delayed Yersinia enterocolitica YopP-induced cell death of dendritic cells. Infect Immun. 2007;75:512–517. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00756-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Monack DM, Mecsas J, Ghori N, Falkow S. Yersinia signals macrophages to undergo apoptosis and YopJ is necessary for this cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10385–10390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhang Y, Bliska JB. Role of Toll-like receptor signaling in the apoptotic response of macrophages to Yersinia infection. Infect Immun. 2003;71:1513–1519. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.3.1513-1519.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zhang Y, Ting AT, Marcu KB, Bliska JB. Inhibition of MAPK and NF-kappa B pathways is necessary for rapid apoptosis in macrophages infected with Yersinia. J Immunol. 2005;174:7939–7949. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Philip NH, Dillon CP, Snyder AG, Fitzgerald P, Wynosky-Dolfi MA, Zwack EE, Hu B, Fitzgerald L, Mauldin EA, Copenhaver AM, et al. Caspase-8 mediates caspase-1 processing and innate immune defense in response to bacterial blockade of NF-κB and MAPK signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:7385–7390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403252111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Weng D, Marty-Roix R, Ganesan S, Proulx MK, Vladimer GI, Kaiser WJ, Mocarski ES, Pouliot K, Chan FK, Kelliher MA, et al. Caspase-8 and RIP kinases regulate bacteria-induced innate immune responses and cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:7391–7396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403477111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lilo S, Zheng Y, Bliska JB. Caspase-1 activation in macrophages infected with Yersinia pestis KIM requires the type III secretion system effector YopJ. Infect Immun. 2008;76:3911–3923. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01695-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zheng Y, Lilo S, Brodsky IE, Zhang Y, Medzhitov R, Marcu KB, Bliska JB. A Yersinia effector with enhanced inhibitory activity on the NF-κB pathway activates the NLRP3/ASC/caspase-1 inflammasome in macrophages. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002026. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zheng Y, Lilo S, Mena P, Bliska JB. YopJ-induced caspase-1 activation in Yersinia-infected macrophages: independent of apoptosis, linked to necrosis, dispensable for innate host defense. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36019. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Pasparakis M, Vandenabeele P. Necroptosis and its role in inflammation. Nature. 2015;517:311–320. doi: 10.1038/nature14191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Adkins I, Schulz S, Borgmann S, Autenrieth IB, Gröbner S. Differential roles of Yersinia outer protein P-mediated inhibition of nuclear factor-kappa B in the induction of cell death in dendritic cells and macrophages. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57:139–144. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47437-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Spinner JL, Seo KS, O’Loughlin JL, Cundiff JA, Minnich SA, Bohach GA, Kobayashi SD. Neutrophils are resistant to Yersinia YopJ/P-induced apoptosis and are protected from ROS-mediated cell death by the type III secretion system. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9279. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Vladimer GI, Weng D, Paquette SW, Vanaja SK, Rathinam VA, Aune MH, Conlon JE, Burbage JJ, Proulx MK, Liu Q, et al. The NLRP12 inflammasome recognizes Yersinia pestis. Immunity. 2012;37:96–107. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Brodsky IE, Medzhitov R. Reduced secretion of YopJ by Yersinia limits in vivo cell death but enhances bacterial virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000067. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lemaître N, Sebbane F, Long D, Hinnebusch BJ. Yersinia pestis YopJ suppresses tumor necrosis factor alpha induction and contributes to apoptosis of immune cells in the lymph node but is not required for virulence in a rat model of bubonic plague. Infect Immun. 2006;74:5126–5131. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00219-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Monack DM, Mecsas J, Bouley D, Falkow S. Yersinia-induced apoptosis in vivo aids in the establishment of a systemic infection of mice. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2127–2137. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.2127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Siefker DT, Echeverry A, Brambilla R, Fukata M, Schesser K, Adkins B. Murine neonates infected with Yersinia enterocolitica develop rapid and robust proinflammatory responses in intestinal lymphoid tissues. Infect Immun. 2014;82:762–772. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01489-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bose R, Thinwa J, Chaparro P, Zhong Y, Bose S, Zhong G, Dube PH. Mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent interleukin-1α intracrine signaling is modulated by YopP during Yersinia enterocolitica infection. Infect Immun. 2012;80:289–297. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05742-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Palmer LE, Hobbie S, Galán JE, Bliska JB. YopJ of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is required for the inhibition of macrophage TNF-alpha production and downregulation of the MAP kinases p38 and JNK. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:953–965. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Schesser K, Spiik AK, Dukuzumuremyi JM, Neurath MF, Pettersson S, Wolf-Watz H. The yopJ locus is required for Yersinia-mediated inhibition of NF-kappaB activation and cytokine expression: YopJ contains a eukaryotic SH2-like domain that is essential for its repressive activity. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:1067–1079. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Shrestha N, Bahnan W, Wiley DJ, Barber G, Fields KA, Schesser K. Eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2) signaling regulates proinflammatory cytokine expression and bacterial invasion. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:28738–28744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.375915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Benabdillah R, Mota LJ, Lützelschwab S, Demoinet E, Cornelis GR. Identification of a nuclear targeting signal in YopM from Yersinia spp. Microb Pathog. 2004;36:247–261. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Skrzypek E, Cowan C, Straley SC. Targeting of the Yersinia pestis YopM protein into HeLa cells and intracellular trafficking to the nucleus. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:1051–1065. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Höfling S, Grabowski B, Norkowski S, Schmidt MA, Rüter C. Current activities of the Yersinia effector protein YopM. Int J Med Microbiol. 2015;305:424–432. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Kerschen EJ, Cohen DA, Kaplan AM, Straley SC. The plague virulence protein YopM targets the innate immune response by causing a global depletion of NK cells. Infect Immun. 2004;72:4589–4602. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.8.4589-4602.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.McPhee JB, Mena P, Zhang Y, Bliska JB. Interleukin-10 induction is an important virulence function of the Yersinia pseudotuberculosis type III effector YopM. Infect Immun. 2012;80:2519–2527. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06364-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ye Z, Kerschen EJ, Cohen DA, Kaplan AM, van Rooijen N, Straley SC. Gr1+ cells control growth of YopM-negative yersinia pestis during systemic plague. Infect Immun. 2009;77:3791–3806. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00284-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Couper KN, Blount DG, Riley EM. IL-10: the master regulator of immunity to infection. J Immunol. 2008;180:5771–5777. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.5771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Leung KY, Reisner BS, Straley SC. YopM inhibits platelet aggregation and is necessary for virulence of Yersinia pestis in mice. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3262–3271. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.10.3262-3271.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Heusipp G, Spekker K, Brast S, Fälker S, Schmidt MA. YopM of Yersinia enterocolitica specifically interacts with alpha1-antitrypsin without affecting the anti-protease activity. Microbiology. 2006;152:1327–1335. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28697-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Hines J, Skrzypek E, Kajava AV, Straley SC. Structure-function analysis of Yersinia pestis YopM’s interaction with alpha-thrombin to rule on its significance in systemic plague and to model YopM’s mechanism of binding host proteins. Microb Pathog. 2001;30:193–209. doi: 10.1006/mpat.2000.0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Reisner BS, Straley SC. Yersinia pestis YopM: thrombin binding and overexpression. Infect Immun. 1992;60:5242–5252. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.12.5242-5252.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]