Abstract

Importance

Multiple lines of evidence suggest a deficit in dopamine release in prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. Despite the prevalence of the concept of prefrontal cortical hypodopaminergia in schizophrenia, in vivo imaging of dopamine release in prefrontal cortex has not been possible until recently, when the validity of using the PET D2/3 radiotracer [11C]FLB457 in combination with the amphetamine paradigm was clearly established.

Objectives

1) To test amphetamine induced dopamine release in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) in drug free or drug naïve patients with schizophrenia (SCZ) and healthy controls (HC) matched for age, gender, ethnicity and familial socioeconomic status, 2) to test BOLD fMRI activation during a working memory task in the same subjects and 3) to examine the relationship between PET and fMRI outcome measures.

Design, Setting and Participants

PET imaging with [11C]FLB457 before and following 0.5 mg/kg P.O. amphetamine. BOLD fMRI during the self-ordered working memory task (SOWT). 20 patients with schizophrenia and 21 healthy controls participated.

Main outcome measure

The percent change in binding potential (ΔBPND) in DLPFC following amphetamine, BOLD activation during the SOWT compared to the control task, and the correlation between these two outcome measures.

Results

We observed: 1) significant differences in the effect of amphetamine on DLPFC BPND (ΔBPND in HC: − 7.5 ± 11%, SCZ: +1.8 ± 11%, p = 0.013), 2) a generalized blunting in dopamine release in SCZ involving most extrastriatal regions and the midbrain, 3) a significant relationship between ΔBPND and BOLD activation in DLPFC in the overall sample including patients with SCZ and HC.

Conclusions and Relevance

These results provide the first in vivo evidence for a deficit in the capacity for dopamine release in DLPFC in schizophrenia, and suggest a more widespread deficit extending to many cortical and extrastriatal regions, including the midbrain. This contrasts with the well-replicated excess in dopamine release in the associative striatum in schizophrenia, and suggests a differential regulation of striatal dopamine release in associative striatum versus extrastriatal regions. Furthermore, dopamine release in the DLPFC relates to working memory-related activation of this region, suggesting that blunted release may affect frontal cortical function.

Introduction

The concept of cortical hypodopaminergia in schizophrenia1 has emerged from converging lines of evidence showing that working memory (WM) is deficient in schizophrenia2, that WM depends critically on optimal prefrontal dopamine (DA) transmission in non-human primates3–10, that it is associated with abnormal prefrontal activation during functional brain imaging studies in schizophrenia11, and that it can improve with DA agonists12–15. Furthermore, post-mortem studies reported a decrease in tyrosine hydroxylase immunolabeling in prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia16–18. While Positron Emission Tomography (PET) studies have investigated alterations in cortical D1 receptor availability19–21, there have been no in vivo studies examining capacity for DA release in frontal cortex in schizophrenia, a gap that contrasts with the considerable body of evidence from in vivo PET imaging studies showing an increase in stimulant-induced DA release in the striatum of patients with schizophrenia22–24.

One major impediment to PET studies of cortical DA release has been the lack of a suitable PET radiotracer. For reasons that are not completely understood, D1 radiotracers have not proven to be sensitive to stimulant-induced DA release 25 whereas D2/D3 tracers have. While radiotracers such as [11C]raclopride and [11C]-(+)-PHNO are useful for detecting acute fluctuations in DA levels in the striatum, the very low density and limited anatomical distribution of DA D2/D3 receptors in cortex26 precludes their use for quantitative imaging of D2/D3 receptors in the cortex. [11C]FLB457 is a higher-affinity PET tracer that has been shown to provide reliable quantification of amphetamine-induced DA release in cortex27,28 (test-retest reproducibility ≤ 15% using conventional compartment analysis methods), although it cannot be quantified in striatum due to its slow washout in this high D2/D3 receptor density region. However, there are challenges in working with this tracer. Most D2/D3 tracers show negligible specific binding in the cerebellum, allowing the use of the cerebellum as a reference region29. This is not the case for [11C]FLB457, as approximately 20% of [11C]FLB457 cerebellum distribution volume VT can be displaced by the D2 partial agonist aripiprazole30.

In the current study, we measured amphetamine-induced DA release in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) in patients with schizophrenia (SCZ) and matched healthy controls (HC) using [11C]FLB457 PET imaging. We implemented a kinetic model with shared parameters across 9 cortical regions, that addressed both the lack of a reference region and the low cortical signal, to quantify receptor availability and DA release. We hypothesized that cortical DA release capacity, especially in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) would be reduced in SCZ compared to HC. We also examined a number of brain regions where D2/D3 receptor availability is intermediate between striatal and cortical binding, including midbrain (substantia nigra, ventral tegmental area), thalamus, and medial temporal regions (amygdala, hippocampus). To test the functional significance of cortical DA release capacity, we used functional MRI (fMRI) to measure changes in the BOLD signal in the DLPFC during performance of the Self-Ordered Working Memory Task (SOWT), and examined associations between cortical DA release capacity and WM task-related DLPFC activation. Finally, we examined the relationships between [11C]FLB457 PET and WM-sensitive performance in SCZ and HC subjects, and clinical symptomatology in patients.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the New York State Psychiatric Institute (NYSPI) of Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) and the Yale University Human Investigation Committee. All participants provided written informed consent following an independent assessment of capacity by a psychiatrist who was not a member of the research team. Patients were recruited from the inpatient and outpatient research facilities at NYSPI. Healthy controls were recruited through advertisements. Medical screening procedures included a physical examination and history, blood and urine tests, an electrocardiogram and a structural magnetic resonance imaging scan of the brain.

Inclusion criteria for patients were: (1) lifetime DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed.) diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective or schizophreniform disorder; (2) no bipolar disorder; (3) no antipsychotics for 3 weeks prior to the PET scan; (5) no history of violent behavior. Inclusion criteria for healthy controls were: (1) absence of any current or past DSM-IV Axis-I diagnosis; and (2) no family history (first-degree) of psychotic illness.

Exclusion criteria for both groups: significant medical and neurological illnesses, current misuse of substances other than nicotine, positive urine drug screen, pregnancy and nursing. Groups were matched for age, gender, ethnicity, parental socioeconomic status, and nicotine smoking (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics.

| HC (n = 21) | SCZ patients (n = 20; 1 schizoaffective, 19 schizophrenia) |

p* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 32.6 ± 8.1 | 33.1 ± 10.2 | .887 |

| Sex (F/M) | 11/10 | 10/10 | .879 |

| Ethnicity (C/AA/Hisp/As/mixed) | 2/8/6/2/3 | 1/9/7/1/2 | .913 |

| Parental SES | 35.9 ± 11.3 | 42.6 ± 14.5 | .133 |

| Participant SES | 37.4 ± 14.2 | 21.4 ± 8.0 | <.001 |

| Nicotine smoking (No/Yes) | 18/3 | 15/5 | .638 |

| Drug-naïve/drug-free | - | 6/14 | |

| Onset psychotic symptoms (yrs) | - | 17.3 ± 7.8 | |

| Duration of psychotic illness (yrs) | - | 13.2 ± 11.3 | |

| Drug-free interval (months) | - | 38.4 ± 67.3, (n = 14) |

2 group t tests for continuous variables, χ2 for categorical.

Abbreviation: SES = socioeconomic status.

PET Imaging Study Design

Subjects underwent two PET scans on one day with [11C]FLB457 at the Yale University PET Center. A 90 min baseline scan was acquired, followed immediately by oral administration of amphetamine (0.5 mg/kg) and a second 90 min scan 3 hr after amphetamine administration. Arterial plasma data were collected to form metabolite-corrected input functions. Data were acquired on an HR+ scanner (Siemens, Knoxville TN) and reconstructed by filtered back projection with correction for attenuation, randoms and scatter. Data were binned into a sequence of frames of increasing duration.

PET Data Analysis

Preprocessing

A high resolution T1-weighted MRI scan was acquired for each subject. Regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn on each subject’s MRI according to previously described criteria 20,31,32 (See eMethods.1 for operational definitions of amygdala and hippocampus), and included, in addition to the DLPFC, our a priori ROI, the medial frontal cortex (MFC), orbito-frontal cortex (OFC), anterior cingulate (A. CING), occipital cortex (OCC), parietal cortex (PAR), temporal cortex (TEMP), sub-genu of the cingulate (GEN), insula, cerebellum, and 5 subcortical regions: amygdala (AMYG), hippocampus (HIPP), midbrain encompassing substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area (SN/VTA), thalamus (THAL) and uncus. PET data were coregistered to the MRI data using normalized maximization of mutual information (SPM8) and the ROIs were transferred to the coregistered PET using MEDx software (Medical Numerics, Germantown MD). Time activity curves were generated as the average activity in each frame for each ROI.

Kinetic Analysis

Data were analyzed with a two tissue compartment model 29,33 (2TC) that additionally incorporated a set of shared parameter estimates across regions, in order to improve reliability of fits by estimating a reduced parameter set compared to conventional 2TC. For each subject, VND, the distribution volume of the nondisplaceable compartment, and k4, the specific binding dissociation constant, were fitted to a single value across cortical regions for both baseline and post-amphetamine scans (See eMethods.2, eTable.1, eFigure.1). The parameters K1, the brain delivery constant and k3, proportional to receptor availability, were fitted in each region and condition. Data were weighted by frame duration; all regions were weighted equally. The same procedure was applied separately to the higher binding subcortical regions, in order to allow for the possibility that the fitting procedure might assign different k4 values in those regions. Distribution volume (VT) was estimated in each region and condition. Binding potential (BPND) was estimated directly from the ratio k3/k4. We report BPND, the relative change following amphetamine (ΔBPND), VT and ΔVT.

Statistics

In DLPFC, two group t tests were applied to baseline BPND, ΔBPND, baseline VT and ΔVT. Additionally, linear mixed modeling with ROI as repeated measure and group and ROI as fixed variables was applied across all 14 regions. Two-sided t tests were applied to scan parameters including injected activity, injected mass, plasma free fraction (fp) and estimated VND and k4. Parameter estimates are reported as mean ± standard deviation.

fMRI Data Analysis

A subset of 16 SCZ and 18 HC participated in a BOLD fMRI study in which they performed the SOWT (among the 20 SCZ and 21 HC subjects, 4 SCZ and 2 HC declined to participate in the fMRI procedures, and one HC’s data were unusable due to poor image quality). Complete details of the task as well as acquisition and analysis are in eMethods.3. Briefly, structural and BOLD images were acquired on a Philips 1.5 T Intera scanner. BOLD images during SOWT task performance were acquired at a 3 mm isotropic voxel size with a TR of 2 s, separated into 9 runs of 160 volumes each. BOLD images underwent slice-timing correction, motion realignment, and coregistration to the T1-weighted structural images. A separate set of BOLD images were normalized to the ICBM template for voxelwise statistical analysis.. The SOWT task consists of a presentation of 8 different geometric shapes on a projection screen. Subjects select one of the shapes; on each successive trial, the positions of shapes on the screen are randomly reordered, and subjects are instructed to select a shape they haven’t picked previously. Thus subjects are required to hold up to 7 distinct items in working memory. There was a monetary incentive for correct answers ($0.25 per correct response). Complete analysis of the BOLD response to the SOWT will be presented elsewhere (Van Snellenberg et al, in submission). Here, we report only the relationship between BOLD and PET data. We regressed DLPFC ΔBPND against overall BOLD activation in DLPFC voxels that were significantly activated during the SOWT. A second-level TASK - CONTROL contrast was calculated on the ICBM-normalized BOLD data to identify voxels showing significant activation during SOWT performance. This group-level map was transformed to the individual subjects’ T1 space and the intersection of the activated region with their DLPFC ROI was used to extract BOLD signal change values within DLPFC for each participant. We used this approach to restrict analysis to DLPFC voxels that showed evidence of involvement in the SOWT.

Neurocognitive and Clinical Measures

Diagnostic status was determined with the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies34 in patients with SCZ followed by a consensus diagnosis conference and an abbreviated version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders35 in HC. Severity of symptoms was assessed with the Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale (PANSS)36, obtained at the start of the PET day. Participant and parental socio-economic status were calculated according to the Hollingshead scale37. Clinical assessments were administered by trained interviewers.

As additional measures of WM, we also assessed performance on the N-back task38 and the Letter Number Span (LNS)39. Both tasks were acquired once on the day preceding the PET scans and a second time after the second PET scan. The n-back task contained three levels of difficulty, including 1, 2 and 3 back. Adjusted hit rate (AHR, the percent of properly identified targets corrected for false positives, see eMethods.4) was assessed as in Abi-Dargham et al20, and ranged from a maximum possible score of 1 for perfect performance to −1 if all true targets were missed and all non-targets were incorrectly identified as targets.

Results

PET Scan Parameters

Injected activity, injected mass, plasma free fraction fp for baseline and amphetamine conditions and estimated VND and k4 are shown in Table 3. There were no significant group differences in any of these.

Table 3.

Scan Parameters

| HC (n = 21) | SCZ (n = 20) | 2 grp t (p) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base ID (MBq) | 175 ± 20 | 177 ± 21 | 0.77 |

| Amph ID (MBq) | 174 ± 30 | 179 ± 20 | 0.50 |

| Base IM (µg) | 0.26 ± 0.13 | 0.24 ± 0.15 | 0.61 |

| Amph IM (µg) | 0.28 ± 0.17 | 0.26 ± 0.17 | 0.68 |

| Base SA (MBq/nmol) | 400 ± 467 | 417 ± 229 | 0.88 |

| Amph SA (MBq/nmol) | 344 ± 259 | 367 ± 176 | 0.74 |

| fp (Base) | 0.30 ± 0.09 | 0.27 ± 0.08 | 0.21 |

| fp (Amph) | 0.29 ± 0.08 | 0.26 ± 0.08 | 0.25 |

| Plasma amph (ng/mL) | 82.6 ± 14.2 | 81.4 ± 24.6* | 0.86 |

| Estimated VND | 3.27 ± 0.55 | 2.97 ± 0.86 | 0.20 |

| Estimated k4 | 0.023 ± 0.008 | 0.022 ± 0.005 | 0.50 |

| Cerebellum VT (base) | 4.56 ± 1.08 | 4.19 ± 0.95 | 0.23 |

| Cerebellum VT (amph) | 4.43 ± 1.11 | 4.29 ± 1.11 | 0.68 |

Plasma amphetamine available in n = 19 SCZ.

Abbreviations: ID = injected dose of radioactivity, IM = injected mass of radiotracer, SA = Specific Activity, Base = baseline scan, amph = post-amphetamine scan, fp, VND, k4 and VT as in Innis et al 200729

PET Results

Baseline DLPFC BPND did not differ significantly between groups but ΔBPND did (HC: −7.5 ± 11%, SCZ: +1.8 ± 11%, p = 0.013) (Table 4). Linear mixed modeling of ΔBPND showed a statistically significant effect of group (F(1,39) = 6.95, p = 0.012) but no significant effect of ROI or group by ROI interaction. While the interaction term was not significant, two regions reached trend level group differences including DLPFC (p = 0.087) and SN/VTA (p = 0.096). BPND was higher in drug-naïve than drug-free patients but there were no significant differences in any PET outcome measure when age was included as a covariate (see eResults.1). VT results are shown in eTable2. Baseline DLPFC VT did not differ significantly between groups. There was a significant difference in DLPFC ΔVT (HC: - 5 ± 7%, SCZ +1 ± 7%, p = 0.013). Linear mixed modeling of ΔVT showed a statistically significant effect of group (F(1,39) = 4.11, p = 0.049) but no significant effect of ROI or group by ROI interaction.

Table 4.

BPND

| HC | SCZ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Post-Amph | ΔBPND | Baseline | Post-Amph | ΔBPND | |

| DLPFC | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | −7.5 ± 11.4% | 1.8 ± 0.7 | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 11.1% |

| OFC | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | −5.5 ± 13.9% | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 2.6 ± 11.3% |

| MFC | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | −4.7 ± 13.2% | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 0.9 ± 10.9% |

| A. CING | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 2 ± 0.5 | −4.9 ± 15.7% | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 2.3 ± 0.7 | 3.6 ± 12.5% |

| OCC CTX | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 1.6 ± 0.5 | −6.5 ± 12.1% | 1.8 ± 0.7 | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 2.1 ± 10.0% |

| PAR CTX | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | −6.1 ± 9.8% | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 1.0 ± 10.4% |

| TEMP CT | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 3.2 ± 0.8 | −5.3 ± 10.0% | 3.4 ± 1.0 | 3.4 ± 0.9 | 0.2 ± 8.6% |

| SUB GEN | 2.4 ± 0.7 | 2.3 ± 0.5 | −1.5 ± 18.1% | 2.6 ± 1.0 | 2.6 ± 0.8 | 5.4 ± 18.0% |

| INSULA | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 3.2 ± 0.7 | −4.1 ± 10.2% | 3.6 ± 1.1 | 3.7 ± 1.0 | 2.3 ± 9.8% |

| AMYGDALA | 5.6 ± 1.7 | 5.4 ± 1.5 | −1.9 ± 16.5% | 5.8 ± 2.4 | 5.9 ± 2.5 | 2.0 ± 11.0% |

| HIPPOCAMPUS | 2.5 ± 0.9 | 2.3 ± 0.7 | −5.1 ± 14.4% | 2.6 ± 1.5 | 2.6 ± 1.5 | 0.5 ± 11.9% |

| SN/VTA | 4.6 ± 1.3 | 4.4 ± 1.2 | −4.5 ± 12.7% | 5.0 ± 2.5 | 5.1 ± 2.5 | 2.7 ± 10.8% |

| THALAMUS | 6.2 ± 1.9 | 5.9 ± 1.6 | −3.0 ± 11.7% | 6.3 ± 2.5 | 6.5 ± 2.6 | 2.8 ± 10.1% |

| UNCUS | 3.8 ± 1.2 | 3.6 ± 1.2 | −5.9 ± 17.5% | 4.0 ± 1.8 | 4.0 ± 1.9 | −1.1 ± 11.6% |

See PET methods for abbreviations

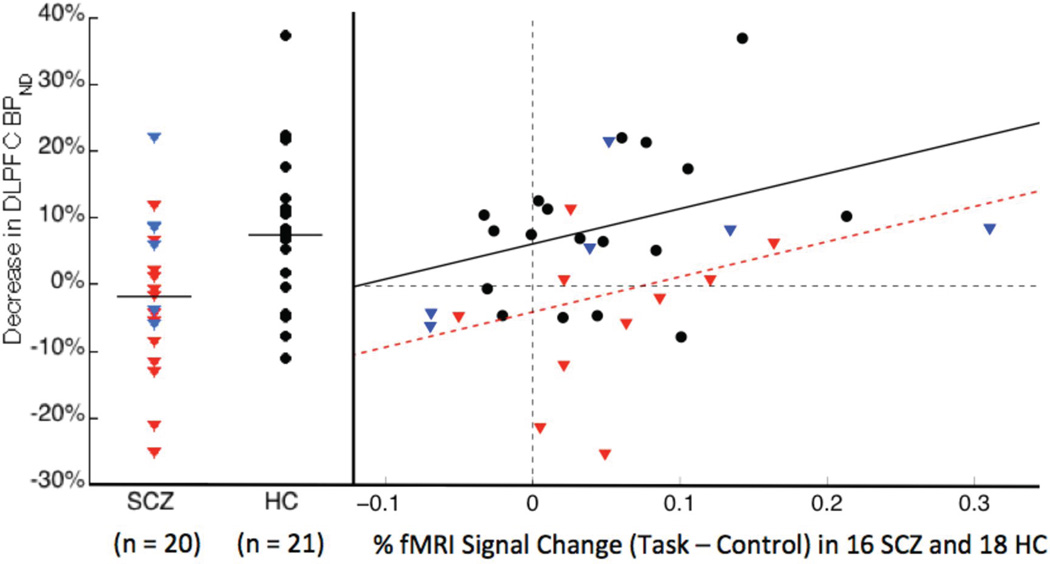

Associations with fMRI Activation

A significant relationship between DLPFC ΔBPND and BOLD activation in DLPFC was observed in SCZ and HC. Regression of ΔBPND onto BOLD activation had a significant effect of group (β = −10.2, t31 = −2.707; P = 0.0109) and a significant effect of BOLD (β = 52.9; t31 = 2.211; P = 0.0345), but no group by BOLD interaction, thus the most parsimonious model contained the same slope for both groups but different intercepts: BPND% decrease (HC) = 53 * BOLD (HC) % increase +6%, BPND% decrease (SCZ) = 53 * BOLD (SCZ) % increase − 4% (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scatterplot of DLPFC ΔBPND (left) and regression of DLPFC ΔBPND onto fMRI BOLD increase during SOWT (right). HC data is in black circles, drug-free SCZ data in red triangles and drug-naïve SCZ in blue triangles. Left: Group means are given by horizontal lines. Right: the lines represent the best linear model fit of the data, with slope equal to 53% for both groups and intercepts of 6% in HC and −4% in SCZ.

Associations with Working Memory Performance and Symptoms

Patients performed significantly worse on the following WM measures: baseline 1-back and post-amphetamine 2-back task and on baseline and post-amphetamine LNS (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical and Neurocognitive assessments

| Assessment | HC (n = 21) | SCZ (n = 20) | 2 grp t (p) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PANSS positive symptoms | 7.0 ± 0.2 | 15.1 ± 4.7 | <.001 |

| PANSS negative symptoms | 9.0 ± 2.5 | 13.6 ± 5.59 | .001 |

| PANSS general symptoms | 17.9 ± 2.5 | 30.4 ± 8.2 | <.001 |

| 1-back baseline AHR | .998 ± .007 | .953 ± .061 | .005 |

| 1-back post-amphetamine AHR |

.991 ± .025 | .947 ± .092 | .060 |

| 2-back baseline AHR | .863 ± .158 | .777 ± .248 | .209 |

| 2-back post-amphetamine AHR |

.916 ± .146 | .768 ± .212 | .014 |

| 3-back baseline AHR | .747 ± .229 | .654 ± .310 | .296 |

| 3-back post-amphetamine AHR |

.730 ± .200 | .608 ± .238 | .088 |

| LNS baseline | 16.7 ± 3.3 | 13.7 ± 3.5 | .010 |

| LNS post-amphetamine | 17.6 ± 3.9 | 14.4 ± 3.0 | .009 |

Abbreviations: PANSS = positive and negative symptom scale, AHR = adjusted hit rate, LNS = letter number sequencing task

In SCZ, there were no correlations between WM performance and DLPFC BPND, ΔBPND, VT, or ΔVT. In HC, WM performance correlated with DLPFC BPND (baseline 2-back, ρ = .50, p = .031, baseline 3-back, ρ = .79, p <.001, SOWT, ρ = .50, p = .031) and VT (baseline 3-back, ρ = .68, p = 0.001) in the DLPFC. Exploratory analyses of correlations at each level of the SOWT revealed significant correlations between DLPFC BPND and WM performance when WM load was greatest (step 7: r = 0.48, p = 0.042, step 8: r = 0.66, p = 0.003). Exploratory analyses including all fourteen ROIs, using a linear mixed model with ROIs as repeated measures resulted in an overall positive association between BPND in the analyzed regions and baseline 2-back (F(1,16.9) = 4.99, p = 0.039), 3-back (F(1,16.9) = 14.18, p = 0.002) and SOWT (F(103.4) = 8.08, p = 0.005) in HC. The same design applied to VT showed an overall positive association of VT with baseline 3-back (F(1,16.6) = 14.18, p = 0.002) in HC. There were no significant correlations between WM performance and ΔBPND or ΔVT in HC. There were no significant correlations between PANSS scores (Table 2) and BPND, ΔBPND VT, or ΔVT..

Discussion

In this study we observed that patients with schizophrenia show blunted amphetamine-induced DA release in the DLPFC in vivo. This deficit in DA release extended to other extrastriatal regions including midbrain. We also observed a correlation between this index of DA release capacity and WM-related activation of the DLPFC, as measured with BOLD fMRI.

Despite the prevalence of the concept of hypodopaminergia in schizophrenia, there had been no empirical evidence for decreased cortical DA release prior to this study. This was related to the difficulty in measuring DA release in the cortex due to the low level of cortical D2 receptors26 and the small range of displacement of D2 radiotracers by DA. Here, we adopted and optimized an [11C]FLB457 displacement paradigm shown to be a valid and reliable proxy for changes in extracellular DA following an amphetamine challenge27,40,41.

Precise quantification of [11C]FLB457 displacement is challenging both because the signal is quite small despite the high affinity of [11C]FLB457, and because the cerebellum cannot be used as a suitable reference tissue. Considering these factors, we developed a kinetic approach that was sensitive enough to detect a small change within a small signal. The shared parameter method we’ve applied here took advantage of the fact that [11C]FLB457 kinetics are similar in many cortical regions, and greater parsimony can be achieved through the dramatic reduction of the number of estimated parameters. In simulations (see eMethods.2), we extensively tested cases in which the underlying assumptions of the shared parameter method - uniform k4 across cortical regions and between scans, uniform VND between scans - were intentionally violated, and found that the method performed more precisely than conventional 2TC. We also note that the average estimated VND is 70% of cerebellum VT, in agreement with Narendran et al30.

In the primate PFC, [11C]FLB457 displacement correlates with changes in extracellular DA across doses of amphetamine41. Amphetamine increases synaptic and extracellular DA by reversing the DA transporter42. Microdialysis measures the summed effects of a given drug on synaptic release, extrasynaptic release, and uptake. D2/D3 tracer displacement on the other hand is considered an index of synaptic DA release. This interpretation comes from the fact that while the PET measure reliably correlates with microdialysis measurements of extracellular DA across doses of a given DA-releasing drug, the slopes of these correlations differ across drugs and across brain regions. This presumably reflects differences in the relative contributions of DA release and uptake. This may be important for our interpretation of regional differences in amphetamine-induced D2/D3 tracer displacement in SCZ. Regulation of DA release and reuptake in the cortex and other extra-striatal regions differs from regulation in the striatum43–46. For example, in the cortex and other regions with noradrenergic inputs, but not in the striatum, the norepinephrine transporter (NET) is also a major regulator of extracellular DA levels43,44,47,48. A decrease in amphetamine-induced release in the DLPFC observed in SCZ could reflect decreased synthesis and vesicular storage, altered metabolism, or altered regulation of synaptic DA by the DAT or NET.

Surprisingly, our PET study uncovered widespread lower DA release in SCZ compared to HC encompassing most cortical and extrastriatal regions, including the ventral midbrain. Notably, this observation appears to be inconsistent with [18F]FDOPA PET and post-mortem findings supporting an increase in DA synthesis and/or storage in the midbrain in SCZ49. Further experiments are needed to confirm whether the increase in [18F]FDOPA uptake and decreased DA release capacity in the midbrain co-exist within the same patients or whether they reflect an uncoupling of DA synthesis and release in the midbrain.

The contrast between the generalized DA deficit in cortical and extrastriatal regions and the increase in DA release in the striatum in SCZ24,50–52 is particularly intriguing. This dissociation may reflect abnormal local presynaptic regulation of DA specific to the striatum existing on a background of DA release deficits. Alternatively, a discrete DA neuron subpopulation within the midbrain, innervating the associative striatum (AST), may be over-active. Taken together, the apparently discordant abnormalities across the midbrain, striatum and cortex raises the possibility that SCZ involves a widespread DA release deficit, co-existing with abnormal local dysregulation of DA release or uptake in the striatum (particularly AST), and possible uncoupling of DA synthesis and storage from dendritic DA release in the midbrain. More basic research is required to clarify the mechanisms regulating DA synthesis, vesicular storage, release and reuptake - and their coupling - in midbrain, cortex and striatum45,46.

Since DA is important for frontal cortex-dependent cognition including WM, we examined the relationship between DLPFC DA release capacity and fMRI BOLD activation within the DLPFC during WM performance. DA release correlated with BOLD activation, and did not differ between groups. The relationship between BOLD and DA release suggests that fluctuations in DA release in the DLPFC may modulate the strength of the hemodynamic (and presumably neuronal) response to cognitive “processing demands” placed on DLPFC circuitry. Interestingly, while release capacity correlated with the cortical response to the WM challenge, it did not predict performance, which was impaired in patients with SCZ. One potential explanation is that WM performance is tightly coupled to DA release dynamics during cognitive challenges53, a measure not captured by amphetamine-induced release. Notably, we found a positive association between D2 BPND and WM performance in HC but not in SCZ. Consistent with reports that D2 stimulation can effectively gate synaptic plasticity in cortical projection neurons54, this finding suggests that under normal conditions, D2 availability may be a rate-limiting factor for WM whereas in SCZ, WM capacity is limited by mechanisms upstream or independent of DLPFC D2 receptors.

In summary, our study established that in SCZ, amphetamine-induced DA release is deficient. This contrasts with the well-replicated increased DA storage and release in the striatum in SCZ. Moreover, the relationships between DA indices and prefrontal cortical function during WM are complex and may be modulated in part by the availability of DA receptors. These findings highlight the need to fully determine the molecular mechanisms regulating DA synthesis, storage, release and reuptake, and examine how these mechanisms operate in different DA projection fields. Such studies will lead to an understanding of the complex dopaminergic phenotype in schizophrenia, and advance the development of a coordinated treatment strategy for symptoms and cognitive disturbances in this disorder.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the staff of the Division of Translational Imaging at the New York State Psychiatric Institute and the staff of Yale University School of Medicine PET Center, whose hard work and expertise made this study possible.

Funding support for this study was provided by NIMH 1 P50 MH066171-01A1, The Sylvio O. Conte Center for the study of Dopamine Dysfunction in Schizophrenia

References

- 1.Weinberger DR, Berman KF, Daniel DG. Mesoprefrontal cortical dopaminergic activity and prefrontal hypofunction in schizophrenia. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1992;15(Suppl 1 Pt A):568A–569A. doi: 10.1097/00002826-199201001-00296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green MF. What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry. 1996 Mar;153(3):321–330. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnsten AF, Goldman-Rakic PS. Noise stress impairs prefrontal cortical cognitive function in monkeys: evidence for a hyperdopaminergic mechanism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(4):362–368. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.4.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnsten AF, Cai JX, Murphy BL, Goldman-Rakic PS. Dopamine D1 receptor mechanisms in the cognitive performance of young adult and aged monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994 Oct;116(2):143–151. doi: 10.1007/BF02245056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sawaguchi T, Goldman-Rakic PS. D1 dopamine receptors in prefrontal cortex: involvement in working memory. Science. 1991;251(4996):947–950. doi: 10.1126/science.1825731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sawaguchi T, Goldman-Rakic PS. The role of D1-dopamine receptor in working memory: local injections of dopamine antagonists into the prefrontal cortex of rhesus monkeys performing an oculomotor delayed-response task. J Neurophysiol. 1994 Feb;71(2):515–528. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.2.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castner SA, Goldman-Rakic PS. Enhancement of working memory in aged monkeys by a sensitizing regimen of dopamine D1 receptor stimulation. J. Neurosci. 2004 Feb 11;24(6):1446–1450. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3987-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castner SA, Williams GV, Goldman-Rakic PS. Reversal of antipsychotic-induced working memory deficits by short-term dopamine D1 receptor stimulation. Science. 2000;287(5460):2020–2022. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cai JX, Arnsten AF. Dose-dependent effects of the dopamine D1 receptor agonists A77636 or SKF81297 on spatial working memory in aged monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997 Oct;283(1):183–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnsten AF, Jin LE. Molecular influences on working memory circuits in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2014;122:211–231. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-420170-5.00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minzenberg MJ, Laird AR, Thelen S, Carter CS, Glahn DC. Meta-analysis of 41 functional neuroimaging studies of executive function in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009 Aug;66(8):811–822. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barch DM, Carter CS. Amphetamine improves cognitive function in medicated individuals with schizophrenia and in healthy volunteers. Schizophr Res. 2005 Sep 1;77(1):43–58. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barch DM, Ceaser A. Cognition in schizophrenia: core psychological and neural mechanisms. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012 Jan;16(1):27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daniel DG, Weinberger DR, Jones DW, et al. The effect of amphetamine on regional cerebral blood flow during cognitive activation in schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 1991;11(7):1907–1917. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-07-01907.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glahn DC, Ragland JD, Abramoff A, et al. Beyond hypofrontality: a quantitative meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies of working memory in schizophrenia. Hum Brain Mapp. 2005 May;25(1):60–69. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akil M, Edgar CL, Pierri JN, Casali S, Lewis DA. Decreased density of tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactive axons in the entorhinal cortex of schizophrenic subjects. Biol. Psychiatry. 2000;47(5):361–370. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00282-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akil M, Pierri JN, Whitehead RE, et al. Lamina-specific alterations in the dopamine innervation of the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenic subjects. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(10):1580–1589. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.10.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akil M, Lewis DA. The cathecolaminergic innervation of the human entorhinal cortex: comparisons of schizophrenics and controls. Schizophrenia Res. 1995;15:S25. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abi-Dargham A, Mawlawi O, Lombardo I, et al. Prefrontal dopamine D1 receptors and working memory in schizophrenia. J. Neurosci. 2002 May 1;22(9):3708–3719. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03708.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abi-Dargham A, Xu X, Thompson JL, et al. Increased prefrontal cortical D(1) receptors in drug naive patients with schizophrenia: a PET study with [(1)(1)C]NNC112. Journal of psychopharmacology. 2012 Jun;26(6):794–805. doi: 10.1177/0269881111409265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okubo Y, Suhara T, Suzuki K, et al. Decreased prefrontal dopamine D1 receptors in schizophrenia revealed by PET. Nature. 1997;385(6617):634–636. doi: 10.1038/385634a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laruelle M, ABi-Dargham A. Dopamine as the wind of the psychotic fire: new evidence from brain imaging studies. J Psychopharmacology. 1999 doi: 10.1177/026988119901300405. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laruelle M. Imaging dopamine transmission in schizophrenia A review and meta- analysis. Q J Nucl Med. 1998;42(3):211–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howes OD, Kambeitz J, Kim E, et al. The nature of dopamine dysfunction in schizophrenia and what this means for treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012 Aug;69(8):776–786. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abi-Dargham A, Simpson N, Kegeles L, et al. PET studies of binding competition between endogenous dopamine and the D-1 radiotracer [C-11]NNC 756. Synapse. 1999 May;32(2):93–109. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199905)32:2<93::AID-SYN3>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kessler RM, Whetsell WO, Ansari MS, et al. Identification of extrastriatal dopamine D2 receptors in postmortem human brain with [125I]epidipride. Brain Res. 1993;609:237–343. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90878-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Narendran R, Frankel WG, Mason NS, et al. Positron emission tomography imaging of amphetamine-induced dopamine release in the human cortex: a comparative evaluation of the high affinity dopamine D2/3 radiotracers [11C]FLB 457 and [11C]fallypride. Synapse. 2009;63(6):447–461. doi: 10.1002/syn.20628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Narendran R, Mason NS, May MA, et al. Positron emission tomography imaging of dopamine D(2)/(3) receptors in the human cortex with [(1)(1)C]FLB 457: reproducibility studies. Synapse. 2011 Jan;65(1):35–40. doi: 10.1002/syn.20813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Innis RB, Cunningham VJ, Delforge J, et al. Consensus nomenclature for in vivo imaging of reversibly binding radioligands. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2007 Sep;27(9):1533–1539. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Narendran R, Mason NS, Chen CM, et al. Evaluation of dopamine D(2)/(3) specific binding in the cerebellum for the positron emission tomography radiotracer [(1)(1)C]FLB 457: implications for measuring cortical dopamine release. Synapse. 2011 Oct;65(10):991–997. doi: 10.1002/syn.20926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abi-Dargham A, Martinez D, Mawlawi O, et al. Measurement of striatal and extrastriatal dopamine D-1 receptor binding potential with [C-11]NNC 112 in humans: Validation and reproducibility. J Cerebr Blood F Met. 2000 Feb;20(2):225–243. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200002000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kegeles LS, Slifstein M, Xu XY, et al. Striatal and Extrastriatal Dopamine D-2/D-3 Receptors in Schizophrenia Evaluated With [F-18]fallypride Positron Emission Tomography. Biological Psychiatry. 2010 Oct;68(7):634–641. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Slifstein M, Laruelle M. Models methods for derivation of in vivo neuroreceptor parameters with PET and SPECT reversible radiotracers. Nucl. Med. Bio. 2001;28:595–608. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(01)00214-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nurnberger JI, Jr, Blehar MC, Kaufmann CA, et al. Diagnostic interview for genetic studies Rationale, unique features, and training NIMH Genetics Initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(11):849–859. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950110009002. discussion 863-844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0) New York: Biometrics Research Dept., New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The Positive Negative Syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schiz. Bull. 1987;13:261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hollingshead AB. Four factor index of social status. New Haven, Connecticut: Working paper published by the author; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen JD, Forman SD, Braver TS, Casey BJ, Servan-Schreiber D, Noll DC. Activation of the prefrontal cortex in a nonspatial working memory task with functional MRI. Human Brain Mapping. 1994;1:293–304. doi: 10.1002/hbm.460010407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale - Third Edition Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Narendran R, Mason NS, May MA, et al. Positron Emission Tomography Imaging of Dopamine D2/3 Receptors in the Human Cortex With C-11 FLB 457: Reproducibility Studies. Synapse. 2011 Jan;65(1):35–40. doi: 10.1002/syn.20813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Narendran R, Jedema HP, Lopresti BJ, et al. Imaging dopamine transmission in the frontal cortex: a simultaneous microdialysis and [11C]FLB 457 PET study. Mol Psychiatry. 2014 Mar;19(3):302–310. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sulzer D, Maidment NT, Rayport S. Amphetamine and other weak bases act to promote reverse transport of dopamine in ventral midbrain neurons. J Neurochem. 1993;60(2):527–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bymaster FP, Katner JS, Nelson DL, et al. Atomoxetine increases extracellular levels of norepinephrine and dopamine in prefrontal cortex of rat: A potential mechanism for efficacy in Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002 Nov;27(5):699–711. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mazei MS, Pluto CP, Kirkbride B, Pehek EA. Effects of catecholamine uptake blockers in the caudate-putamen and subregions of the medial prefrontal cortex of the rat. Brain Res. 2002 May 17;936(1–2):58–67. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02542-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abercrombie ED, DeBoer P, Heeringa MJ. Biochemistry of somatodendritic dopamine release in substantia nigra: an in vivo comparison with striatal dopamine release. Advances in pharmacology (San Diego, Calif.) 1998;42:133–136. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60713-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siciliano CA, Calipari ES, Ferris MJ, Jones SR. Biphasic mechanisms of amphetamine action at the dopamine terminal. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for NeuroScience. 2014 Apr 16;34(16):5575–5582. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4050-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tanda G, Pontieri FE, Frau R, Di Chiara G. Contribution of blockade of the noradrenaline carrier to the increase of extracellular dopamine in the rat prefrontal cortex by amphetamine and cocaine. Eur J Neurosci. 1997 Oct;9(10):2077–2085. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamamoto BK, Novotney S. Regulation of extracellular dopamine by the norepinephrine transporter. Journal of neurochemistry. 1998 Jul;71(1):274–280. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71010274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Howes OD, Williams M, Ibrahim K, et al. Midbrain dopamine function in schizophrenia and depression: a post-mortem and positron emission tomographic imaging study. Brain. 2013 Nov;136(Pt 11):3242–3251. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guillin O, Abi-Dargham A, Laruelle M. Neurobiology of dopamine in schizophrenia. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007;78:1–39. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(06)78001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Toda M, Abi-Dargham A. Dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia: making sense of it all. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007 Aug;9(4):329–336. doi: 10.1007/s11920-007-0041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miyake N, Thompson J, Skinbjerg M, Abi-Dargham A. Presynaptic dopamine in schizophrenia. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2011 Apr;17(2):104–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00230.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eshel N, Tian J. Dopamine gates sensory representations in cortex. Journal of neurophysiology. 2014;111(11):2161–2163. doi: 10.1152/jn.00795.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu TX, Yao WD. D1 and D2 dopamine receptors in separate circuits cooperate to drive associative long-term potentiation in the prefrontal cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010 Sep 14;107(37):16366–16371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004108107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.