Abstract

A critique of cash assistance programs is that beneficiaries may spend the money on “temptation goods” such as alcohol and tobacco. We exploit a change in the payment schedule of Peru’s conditional cash transfer program to identify the impact of benefit receipt frequency on the purchase of temptation goods. We use annual household data among cross-sectional and panel samples to analyze the effect of the policy change on the share of the household budget devoted to four categories of temptation goods. Using a difference-in-differences estimation approach, we find that larger, less frequent payments increased the expenditure share of alcohol by 55–80% and sweets by 10–40%, although the absolute magnitudes of these effects are small. Our study suggests that less frequent benefits scheduling may lead cash recipients to make certain types of temptation purchases.

Keywords: temptation goods, conditional cash transfers, impulse purchases, alcohol, tobacco, Peru

1 Introduction

A common critique of cash assistance programs is that beneficiaries may squander the money or use it in ways that reduce their welfare. A particular source of concern is that husbands will wrest the money from their wives and use it to feed their own vices, such as alcohol and tobacco (John, 2008; Wang, Sindelar and Busch, 2006). This concern has prompted some programs to give cash transfers preferentially to a female head of the household, who are thought to be more likely to invest in their children’s human capital (Lundberg, Pollak and Wales, 1997). Behavioral economists have noted that, in addition to intra-household bargaining between spouses, cash transfers can spur intra-personal bargaining conflicts. Many individuals experience a short-run impatience that leads a present self to neglect the long-run consumption plans of past selves and the consequences of impulsive consumption for future selves (Laibson, 1997; O’Donoghue and Rabin, 1999). As a result, present-biased individuals are tempted to spend income on goods that benefit the present consumer but not his future incarnations. Banerjee and Mullainathan (2010) refer to these purchases as “temptation goods.”

In this study, we consider whether the timing of income receipt promotes the purchase of health-related temptation goods among beneficiaries of a conditional cash transfer (CCT) program in Peru. We narrow our focus to temptation goods for two main reasons. First, as cash assistance programs have proliferated in developing countries, researchers and policymakers have begun to understand their impacts on the health and welfare of recipients. The consumption of temptation goods represents an unintended consequence that has rarely been incorporated into evaluations of program effectiveness, despite temptation spending being indicative of a wasteful and potentially welfare-reducing use of program funds. Second, the health and economic impacts of temptation purchasing likely fall disproportionately on low-income populations. Low-income groups face a long list of complex and competing demands for their mental resources. As a result, they may have limited cognitive “bandwidth” available to devote to willpower (Mullainathan and Shafir, 2013). Several studies find that cognitive performance decreases when a person is mentally taxed (Mani et al., 2013; Spears, 2011), and low-income families are most likely to face this mental strain.

Much of the evidence on temptation purchasing comes from payday or “first-of-the-month” effects. In many contexts, the timing of household purchasing behavior is sensitive to the timing of income receipt, often displaying signs of a regular cycle. Recipients tend to make larger or more frequent discretionary purchases around the time of receipt of a regular income stream. Researchers have documented this pattern among Social Security recipients and vehicle loan recipients in the U.S., paycheck recipients in the U.K., and pensioners in Japan (Stephens, 2003, 2006, 2008; Stephens and Unayama, 2011). In addition, several studies have found a monthly consumption cycle for recipients of food assistance in the U.S. (Wilde and Ranney, 2000; Shapiro, 2005; Hastings and Washington, 2010). These consumption cycles are highly suggestive that individuals have a short-run impatience, or present bias (Huffman and Barenstein, 2005).1 Patterns of cycling may have particularly serious consequences for low-income households, for example, increasing their risk of health problems as a result of food shortfalls at month’s end (Seligman et al., 2014).

While research has pointed to temptation purchasing in high-income countries, the evidence in low-and middle-income countries tends to downplay its importance. Evans and Popova (2014) conduct a systematic review of the effects of cash transfer programs in low-and middle-income countries on alcohol and tobacco consumption. They identify 19 studies drawn largely from unpublished material, including eight randomized controlled trials. All but two show a negative or null effect of transfers on alcohol and tobacco consumption. The authors suggest several factors that may offset the income effect of transfers on temptation purchasing: cash transfers may induce a substitution effect that increases the value of health and schooling among recipients; social messaging from programs may lead to mental labeling of cash transfers for health and schooling; and money is often targeted to women who are less likely to use alcohol and tobacco.

The findings from Evans and Popova (2014) appear to be robust to different measures of consumption, different estimation strategies, and different countries, although the existing literature does have certain limitations. Several studies suffer from weak methods, for example, being under-powered to detect an effect or using a pre-post design. Several studies focus solely on consumption by children and adolescents, who are not the principal recipients of the transfers nor the primary consumers of temptation goods. As such, they may have limited scope to respond behaviorally to the transfers. At least one study measures outcomes using indicator variables for whether respondents consumed any temptation goods. We hypothesize that cash transfers are more likely to operate on the intensive margin for adults, whose consumption habits are well established, for example, making them more likely to purchase an extra pack of cigarettes than to initiate a smoking habit. Finally, the demand for temptation goods may be manifested through the consumption of goods aside from tobacco or alcohol, such as sweets, that have been far less studied.

In this study, we exploit a change in the payment schedule of Peru’s CCT program to identify the impact of benefit receipt frequency on the purchasing practices of member households. Starting in January 2010, the payment schedule in the Juntos CCT program in Peru changed from once a month to once every two months. The total annual payment did not change. We hypothesize that larger, less frequent payments lead households to make more temptation purchases. The policy puts more money in the hands of households at one time, which may trigger two behavioral mechanisms that contribute to the purchase of temptation goods. First, present-biased preferences may make recipients who are flush with cash more likely to splurge on temptation goods, a conclusion supported by the literature on payday effects. Second, households are more likely to be in a state of heightened arousal at the end of the month when they are low on cash, and consumers in a viscerally aroused state are more likely to over-estimate their preferences for consuming temptation goods. This tendency is reflected in the old adage never to shop on an empty stomach for fear of consuming more than needed. Behavioral economists refer to the tendency to project one’s current state onto one’s predictions for the future as “projection bias” (Loewenstein, O’Donoghue and Rabin, 2003). Projection bias may lead hungry consumers to “over-consume” unhealthy goods and consumers in a state of craving to “over-consume” alcohol or tobacco (Read and van Leeuwen, 1998; Badger et al., 2007). Consumers are most likely to find themselves in these visceral states at the time that they receive the transfer.

We determine the impact of the payment schedule change using a difference-in-differences estimation strategy, before and after the policy change for Juntos recipient and non-recipient households. The control group consists of households in comparable low-income districts where Juntos was not available. Using household data from 2007 to 2012, we analyze the impact of the payment schedule change on the share of the household budget devoted to four categories of temptation expenditures: alcohol, tobacco, sweets and sugary foods, and soft drinks. We derive a series of demand equations using a Quadratic Almost Ideal Demand System to study the impact of benefits scheduling on temptation purchasing. We test for temptation purchasing in a repeated cross-section and a panel of households. We include area-level fixed effects in the repeated cross-sectional analysis and household fixed effects in the panel analysis. Thus, in the panel sample, we identify the policy impact by analyzing the purchasing behavior of the same households over time before and after the policy change, controlling for time-invariant confounders.

Two studies have addressed temptation purchasing among beneficiaries in the Juntos CCT program in Peru. Dasso and Fernandez (2013) use quasi-random variation in the payment dates for districts and survey interview dates of respondents in order to isolate the effect of having “cash in hand.” They find that households who recently received a Juntos payment have higher consumption of sweets and soft drinks, each measured as an indicator for any consumption. Consumption of alcohol did not change for those who had cash in hand. Interestingly, the effects on temptation purchasing are concentrated in 2010, the year immediately after the policy under study here went into effect. As part of a broader evaluation of the Juntos program, Perova (2010) examines alcohol consumption among recipient households and a set of control households. Using a difference-in-differences estimator, she finds that Juntos decreased expenditures on alcoholic beverages by 0.15 Peruvian nuevos soles per month.2 Using an instrumental variables approach that accounts for selection into the program, the sign on the alcohol coefficient flips; Juntos increased expenditures on alcohol by 0.28 soles per month, a small but statistically significant amount. Our study builds on this literature by testing for temptation purchasing using a natural experiment and testing how the design of a CCT program can encourage or discourage temptation purchasing.

We find that larger, less frequent payments increased the share of expenditures spent on alcohol and sweets and perhaps tobacco, but not those spent on soft drinks. The less frequent payment system increased alcohol expenditures about 55–80% and expenditures on sweets about 10–40%, although these large relative gains are from a very small base. We find evidence that the effect of the scheduling change is concentrated almost exclusively on the intensive margin. Our study highlights the importance of benefits scheduling for the purchasing behavior of social welfare recipients. Policymakers may be able to curtail the degree to which public program recipients use their benefits on temptation goods simply by distributing payments more frequently over time.

2 Background

From 1980 to 2000, the Peruvian countryside was ravaged by a guerrilla war between Maoist insurgents and a government counterinsurgency. In the wake of the political violence, the Peruvian government searched for ways to build national solidarity and to assist affected areas. In 2005, Peru established the Juntos (“Together”) program, inspired by and modeled after successful CCT programs in countries like Mexico, Brazil, and Colombia. A number of impact evaluations have found that CCT programs, which condition the receipt of cash on meeting specified criteria, lead to large improvements in the health, economic, and educational outcomes of beneficiaries (Ranganathan and Lagarde, 2012; Fiszbein and Schady, 2009; Baird et al., 2013). The objectives of Peru’s program were twofold: poverty alleviation in the short run by providing cash to households and disruption of intergenerational poverty in the long run by developing human capital via improved access to schooling and health services (Perova and Vakis, 2009). Program enrollment has grown steadily from about 2,000 villages (70 districts) in 2005 to 28,000 villages (646 districts) in 2010 to more than 37,000 villages (1,083 districts) in 2013.

Cash assistance in Juntos, as with other CCTs, is tied to several conditionalities, including school attendance, infant vaccination, well-child visits, nutrition supplementation for infants, prenatal and postnatal care, and parental education about nutrition, health, and hygiene at health clinics. Program eligibility is determined in three stages: the selection of eligible districts, the selection of eligible households within eligible districts, and community-level validation of the beneficiary list (Perova and Vakis, 2009). Districts are selected based on exposure to violence during the guerrilla war, the amount of poverty and extreme poverty, the poverty gap, or average income shortfall relative to the poverty line, and the amount of child malnutrition (Perova and Vakis, 2009). Eligible households have a child under the age of 14 or a pregnant woman and are selected based on a proxy means test. Community members, local authorities, and officials from the Ministry of Education and Health then validate the households selected for inclusion and exclusion.

Juntos provides a fixed, lump-sum payment to eligible households that does not vary by household size or number of children. As a fraction of average household expenditures, Juntos is less generous than most other CCT programs in Latin America, with the exception of the programs in Honduras and Bolivia (Perova and Vakis, 2012). The Juntos transfer is equivalent to 10–15% of average monthly household expenditures, compared to 25% in Mexico and 30% in Colombia (Fernandez and Saldarriaga, 2013; Perova and Vakis, 2012). Through December 2009, Juntos recipient households received 100 soles per month. Starting in January 2010, the government moved from a monthly to a bimonthly payment schedule, such that Juntos households received 200 soles every two months. Districts are assigned to receive Juntos payments via one of three mechanisms: at a local branch of Banco de Nación, by armored van delivery to the village or district center, or at the offices of correspondent banks of Banco de Nación. In 2010, 55.4% of beneficiaries picked up a check at Banco de Nación, 42.6% received their payment at the village or district center, and 2.0% at a correspondent bank of Banco de Nación. When the program moved to bimonthly payments, it substantially reduced the program’s operating costs for payment disbursement and delivery.

Consumption of temptation-related behaviors in Peru is typical for a Latin American country. In 2010, the prevalence of tobacco use in Peru was about 18% for men and 5% for women (Ng et al., 2014a), slightly higher than the regional average. In 2005, adult per-capita consumption of alcohol was about 7 liters, compared to 9 liters on average in the Americas (World Health Organization, 2011). In 2011, Peruvians consumed 56 liters of soft drinks per capita, slightly below its neighbors (e.g., 65 liters in Bolivia and Ecuador and 68 liters in Colombia), according to Euromonitor data. About 9% of adult men and 25% of adult women in Peru are obese, typical for women but below average for men in other Latin American countries ( Ng et al., 2014b).

3 Data

We use a difference-in-differences estimation strategy to determine the impact of the change in the CCT payment schedule on the budget share of certain categories of temptation goods. The policy change took effect on January 1, 2010. A challenge for the analysis is identifying a valid control group, as a key assumption of difference-in-differences models is that the average pre-treatment time trend is the same for the treatment and control groups. We constructed the control group from low-income households in districts that are not eligible for the CCT program. The expansion of the Juntos program into new districts did not occur in a systematic way. According to interviews with program managers, haphazard events such as adverse weather conditions helped determine the order in which districts were incorporated into the program (Perova and Vakis, 2012). The lack of a systematic rollout plan provides a basis for using the matched districts as controls.

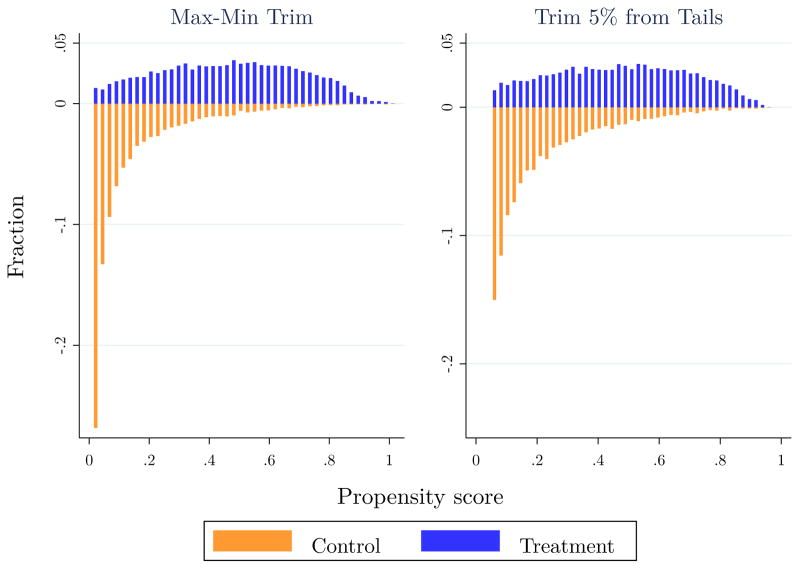

In order to improve comparability, we estimated a propensity score and trimmed the sample to ensure the balance of covariates between the treatment and control groups, thereby meeting the so-called overlap condition. This condition ensures that treatment observations have comparison observations “nearby” in the propensity score distribution and is an important precondition for estimating causal effects (Heckman, Ichimura and Todd, 1997; Imbens and Rubin, 2015). The estimated propensity score included the full set of covariates in Table 1, plus variables for net household income and interview month. We further restrict the sample to the highlands and rainforest regions of Peru where the Juntos program has been targeted,3 districts that have median net income below 30,000 soles, and households that have net income below 45,000 soles. The latter two cutoffs are based on the income distributions for Juntos households and districts. The main analysis uses a max-min trim rule that trims observations in each group above the maximum or below the minimum support. As a specification check, we also adopt a rule that trims the outer 5% of the tails of the distribution. Both distributions are shown in Appendix Figure A3. Prior to trimming, there were 72,543 observations in the cross-sectional sample after restricting region and community type to villages of less than 4,000 residents. After trimming, there were 30,246 observations in the cross-sectional sample. The corresponding size of the panel sample is 16,795 and 9,046 observations.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics among sample households

| Variable | Cross-section

|

Panel

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Treatment | Control | Treatment | |

| log(Expenditures) | 8.557 | 8.410 | 8.516 | 8.365 |

| (1.012) | (0.702) | (1.007) | (0.700) | |

| Household size | 3.962 | 5.516 | 4.150 | 5.622 |

| (2.212) | (1.999) | (2.259) | (2.055) | |

| Household members who are adult (%) | 0.701 | 0.476 | 0.690 | 0.467 |

| Head is male (%) | 0.809 | 0.848 | 0.814 | 0.849 |

| Education of head (%) | ||||

| None | 0.098 | 0.122 | 0.093 | 0.118 |

| At least some primary | 0.538 | 0.632 | 0.578 | 0.623 |

| At least some secondary | 0.279 | 0.228 | 0.256 | 0.234 |

| At least some tertiary | 0.085 | 0.018 | 0.073 | 0.026 |

| Native language of head (%) | ||||

| Spanish | 0.619 | 0.309 | 0.624 | 0.314 |

| Quechua | 0.283 | 0.648 | 0.278 | 0.639 |

| Other | 0.098 | 0.043 | 0.098 | 0.047 |

| Marital status of head (%) | ||||

| Married or cohabitating | 0.725 | 0.842 | 0.740 | 0.845 |

| Widowed, divorced, or separated | 0.219 | 0.139 | 0.208 | 0.139 |

| Single | 0.056 | 0.019 | 0.052 | 0.016 |

| Respondent is male (%) | 0.276 | 0.175 | 0.267 | 0.174 |

| District poverty (%) | 0.060 | 0.099 | 0.060 | 0.101 |

| Community type (%) | ||||

| Rural, 1–140 residents | 0.163 | 0.189 | 0.157 | 0.204 |

| Rural, 141–400 residents | 0.480 | 0.673 | 0.515 | 0.684 |

| Urban, 1–400 residents | 0.168 | 0.102 | 0.161 | 0.079 |

| Urban, 401–4,000 residents | 0.188 | 0.036 | 0.167 | 0.033 |

| Region (%) | ||||

| Highlands | 0.601 | 0.911 | 0.610 | 0.908 |

| Rainforest | 0.399 | 0.089 | 0.390 | 0.092 |

| Year (%) | ||||

| 2007 | 0.162 | 0.096 | 0.156 | 0.107 |

| 2008 | 0.158 | 0.152 | 0.206 | 0.204 |

| 2009 | 0.159 | 0.165 | 0.222 | 0.214 |

| 2010 | 0.156 | 0.165 | 0.279 | 0.298 |

| 2011 | 0.183 | 0.205 | 0.137 | 0.177 |

| 2012 | 0.183 | 0.202 | - | - |

|

| ||||

| Number of observations | 20,529 | 9,717 | 6,032 | 3,014 |

| Number of districts | 416 | 321 | 228 | 273 |

Note: This table displays means of variables and standard deviations of continuous variables in parentheses. The control group consists of households from non-Juntos districts.

We focus our attention on four expenditure categories of temptation goods: alcohol, tobacco, sweets, and soft drinks. These categories have been identified in the behavioral economics literature as meeting the definition of temptation goods or being susceptible to present-biased preferences (Banerjee and Mullainathan, 2010; Gruber and Köszegi, 2001; Rabin, 2013; Evans and Popova, 2014). Alcohol expenditures includes spending on all alcoholic products, including whisky, rum, pisco (a Peruvian brandy), beer, and wine. Tobacco expenditures includes spending on all tobacco products. Expenditures on sweets includes pastries, candies, and chocolates. Expenditures on soft drinks includes spending on all carbonated beverages, aside from mineral water.

Our main dependent variable is the expenditure share by category. As alternate outcome measures, we consider an indicator of whether the household purchased any goods from a given category and the expenditure share conditional on any purchases within the category. These two outcomes allow us to differentiate between the policy’s impacts on the intensive and extensive margins. It also takes into account the large number of “corner” solutions (i.e., zero expenditures) for many of our categories, including alcohol and tobacco. We assume that consumers have weakly separable preferences across expenditure categories and time periods.

3.1 Household Survey Data

This study uses data from Peru’s Encuesta Nacional de Hogares (ENAHO), an annual survey of individuals and households collected by the National Institute of Statistics (Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática, or INEI). Geocoded microdata from in-person interviews are publicly available at the district level from 1997 onward.4 The study has a probabilistic, stratified, multi-stage sampling design within each department. In urban areas, the primary sampling unit is an urban population center with 2,000 or more residents, and the secondary sampling unit is a cluster that has an average of 120 private residences. In rural areas, the primary sampling unit is an urban population center with 500 to 2,000 residents or a Rural Registration Area (AER, using the acronym in Spanish) that has on average 100 residences, and the secondary sampling unit in urban population centers is a cluster that has an average of 120 private residences. The study is designed for a level of inference at the region × urbanicity level.

We use the cross-sectional and panel samples of households in ENAHO. We use the repeated cross-sectional data collected from 2007 through 2012. Prior to 2007, the survey identified Juntos recipients only if the household responded in the affirmative to a general screening question about whether it had received government assistance, which may lead to systematic under-reporting. The panel sample covers the period from 2007 through 2011, although many households are replaced after two waves because the survey follows the place of residence rather than the household residing there. Juntos participation is determined in ENAHO by a question asking, “In the last 6 months, did you receive any public or private transfers, for example, Juntos program transfers?” The survey included information from 261 of the 638 districts (40%) enrolled in Juntos in 2009 and 159 of the 646 districts (25%) in 2010 (Dasso and Fernandez, 2013). Perova and Vakis (2012) compare administrative data from Juntos and survey-weighted responses about Juntos participation in ENAHO and find that the percentage difference is 8% in 2008 and 1% in 2009.

ENAHO includes questions on household consumption of roughly 200 food and beverage items during the prior 15 days. Tobacco consumption is based on the prior 30 days. The food and beverage data are reported by the head of the household or the head’s spouse. Specific questions include: whether anyone in the household obtained, consumed, purchased, or received the item; how the item was obtained (purchase, self-supply, donation, etc.); if bought, how often it was bought or obtained; in what quantity it was bought; where it was bought; and how much was the total amount of the purchase. For all expenditure categories, we restrict analysis to items that households purchased. All expenditures are annualized and deflated to 2009 terms using the consumer price index constructed for ENAHO. Because the expenditure data are collected at the household level, we are not able to analyze within-household consumption patterns.

3.2 Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 shows the descriptive characteristics among sample households. In our cross-sectional sample, the control group consisting of households from non-Juntos districts includes 20,529 observations, and the treatment group consisting of Juntos recipient households includes 9,717 observations. The comparable numbers for the panel sample is about one-third of the size, 6,032 observations in the control group and 3,014 observations in the treatment group. Although we constructed the control group based on the characteristics of the treatment group, there are still significant differences between the groups. For example, 9% of households in the treatment group reside in the rainforest, compared to 40% in the control group drawn from non-Juntos districts.

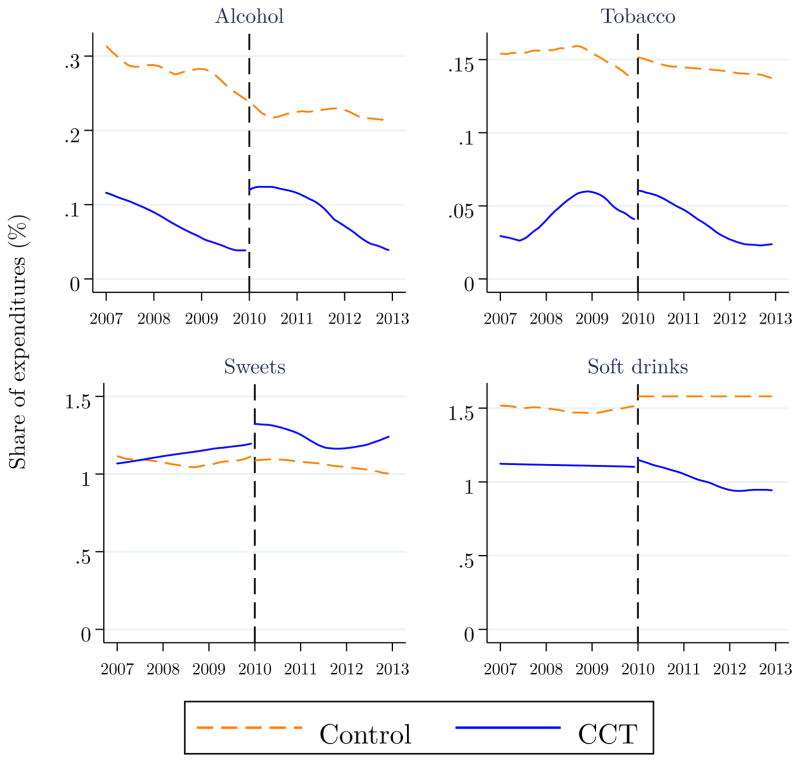

The crucial assumption in a difference-in-differences estimator is that the outcome variables would have grown at the same rate between baseline and follow-up in both treatment and control groups had the policy change not taken place. This common trends assumption is not directly testable, but we observe pre-treatment behavior to give an indication of whether the assumption is likely to hold. Figure 1 shows the share of expenditures by temptation category and month for Juntos recipient households and the control group of households from non-Juntos districts. We make use of the fact that ENAHO quasi-randomly assigns districts to an interview month, in order to construct month-by-month means. We see that, in the pre-policy period, the outcome variables follow a roughly similar trajectory for Juntos recipient households and the control group of households from non-Juntos districts. In Appendix Figure A1, we show that a similar pattern holds for the panel sample, and in Appendix Figure A2, we show that the by-group trends in total expenditures track each other even more closely in pre-policy period. We test the trend difference during the pre-treatment period by interacting our treatment indicator with year dummies in the period before the policy change. We do not find significantly different trends for any of the outcome variables (Table 2), although wide confidence intervals may leave us underpowered to detect the changes. Still, this gives us a measure of confidence that the common trends assumption holds for the outcomes used in the analyses of the cross-sectional sample. In Appendix Table A1, we test for common trends in the panel sample, and find a violation for soft drinks, which could indicate that control households are not comparable for this category. Figure 1 also indicates that the share of expenditures varies greatly by category, and in all cases the share spent on each temptation goods is relatively modest. While soft drinks constitute 1–2% of total expenditures on average, tobacco products constitute less than 0.2%.

Figure 1.

Shares of expenditures, by month and category (Cross-sectional sample)

Note: This figure fits a local polynomial smooth to the monthly trend for the expenditure share by category. Separate trends are plotted for the periods before and after the policy change.

Table 2.

Test of common trends assumption (Cross-sectional sample)

| Budget shares (percent)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | Tobacco | Sweets | Soft drinks | |

| CCT | −0.19** | −0.06** | −0.15 | −0.28** |

| (0.09) | (0.03) | (0.21) | (0.14) | |

| CCT × 2008 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.10 |

| (0.09) | (0.03) | (0.11) | (0.13) | |

| CCT × 2009 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.01 |

| (0.09) | (0.02) | (0.13) | (0.13) | |

| Year, ref = 2007 | ||||

| 2008 | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.11 | −0.12 |

| (0.09) | (0.02) | (0.08) | (0.09) | |

| 2009 | −0.03 | 0.00 | −0.03 | −0.14 |

| (0.08) | (0.02) | (0.08) | (0.09) | |

| Constant | 5.59* | −0.09 | 10.05* | −3.27** |

| (2.87) | (0.35) | (5.55) | (1.40) | |

|

| ||||

| Full set of covariates | Yes | |||

| Region fixed eects | Yes | |||

| Community type F.E. | Yes | |||

| Number of observations | 13,836 | |||

| Number of districts | 617 | |||

Note: This table displays the differences between CCT recipient households and non-CCT district controls in the pre-policy change period among the cross-sectional sample. The coefficients on the interaction of the treatment indicator and year is an indication of whether the two groups have common trends before the policy change. The regressions include all covariates from the models in Table A6. Robust standard errors are clustered at the district level.

Another important assumption that we make in the analyses using the cross-sectional sample is that temporal changes in the composition of the sample do not vary between the treatment and control groups. The absence of compositional changes would suggest that no observable changes affected the samples aside from a change in pay frequency. To measure compositional changes, we compare the difference in average means of baseline characteristics in the pre- and post-policy periods, normalized by standard deviation. We separately assess changes in the treatment and control groups. The results indicate that the changes in sample composition are generally small in both samples (Appendix Tables A2 and A3). All but two variables have a normalized change over time of less than 0.25, implying that the samples are relatively well balanced over time (Imbens and Rubin, 2015). The differences occur for log(Expenditures) and district poverty. Average expenditures likely grew in line with general economic improvement in Peru during this time period. Similarly, district poverty may have diminished over time as the Juntos program expanded to less indigent communities on average. To the extent that there are covariate differences over time, it would only introduce bias if the changes are not balanced between the treatment group and control group.

4 Results

4.1 Policy Effects on Temptation Expenditures

In this section, we describe the impact of a change in the frequency of CCT payments on the share of expenditures spent on four categories of temptation goods. We conduct difference-in-differences analyses of changes in temptation expenditure shares before and after the policy change for Juntos recipient households and control households from non-Juntos districts. We hypothesize that larger, less frequent payments will increase the expenditure shares spent on the temptation goods. We use a model of consumer demand to determine the change in consumer expenditure patterns that result from implementation of the Juntos benefits scheduling policy. To do so, we follow the literature on demand systems that specifies expenditure shares as the dependent variable (Deaton, 1986). Let the expenditure share for the jth good in household i and year t be:

where pijtqijt are the household’s expenditures on good j and Xit are total expenditures.

We derive a series of Engel curves from a Quadratic Almost Ideal Demand System (QUAIDS) that is quadratic in the logarithm of total expenditures (Banks, Blundell and Lewbel, 1997). QUAIDS is a generalization of the Almost Ideal Demand System developed by Deaton and Muellbauer (1980) to give a first-order approximation of household expenditures. The model allows for aggregation across consumers and is consistent with the axioms of utility maximization under consumer theory. QUAIDS more flexibly models the relationship between total household expenditures and the shares of expenditures on certain categories of goods.

We run models with a repeated cross-sectional sample and a panel sample. Using the repeated cross-sectional sample, our main equation takes the form:

| (1) |

where CCTit is the treatment indicator for household participation in the CCT program; Postt is an indicator for post-policy implementation, turned on from 2010 through 2012; Zit is a vector of household- and area-level characteristics; θt are year fixed effects; and εijt is a random error term. This formulation is similar to Deaton, Ruiz-Castillo and Thomas (1989) and adopts the standard convention that prices are the same for all households within each cluster. Our panel analyses are robust to violations of this assumption.

In the cross-sectional models, we control for a number of household and area-level covariates (Zit). These help to account for compositional differences between the treatment and control groups. Covariates include household size, the percentage of household members who are adults (18 years or older), the age, sex, education (none, at least some primary, at least some secondary, or at least some tertiary), and native language (Spanish, Quechua, other) of the household head, the community type as measured by the community’s population size and urbanicity (< 140 rural, 140–400 rural, < 401 urban, 401–4,000 urban), and the region of Peru (north highlands, central highlands, south highlands, and rainforest).5

In the models with the panel sample, we estimate regressions of the following form:

| (2) |

where μi are household fixed effects. In these models, our estimation strategy uses within-household variation in temptation expenditure shares before and after the policy change, providing a better estimate of the changes due to the policy as compared to the cross-sectional models. This refinement comes at a cost, as the panel sample (N = 9, 046) is much smaller than the cross-sectional sample (N = 30, 246) and thus leads to less precisely estimated effects. In the panel models, the household fixed effects absorb all time-invariant household- and community-level characteristics. In all cross-sectional and panel models, we estimate heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors clustered at the district level.

We start by calculating the unadjusted difference-in-differences estimates of the policy’s impact on expenditure shares consumed by temptation good (Appendix Tables A4 and A5). The policy is estimated to increase the expenditure share spent on alcohol by about 0.1 to 0.2 percentage points in both samples. The effect on sweets narrowly misses marginal significance in the cross-sectional sample and is 0.4 percentage points in the panel sample. We find no significant effect on tobacco or soft drinks, and the latter is negative.

We next present the main difference-in-difference estimates in Table 3, based on Equations 1 and 2. The variable of interest, CCT it ×Postt, is displayed for each outcome by temptation expenditure category. In Panel A of Table 3, we analyze the impact on budget shares. The coefficients represent the change in the share of expenditures spent on each given category of expenditures. Using the cross-sectional sample, we find that decreasing the frequency of payments led to an increase in the budget share spent on alcohol and a decrease in the budget share spent on soft drinks. Using the panel sample, we observe increased expenditures on alcohol, tobacco, and sweets. However, the absolute changes in expenditure shares are small in magnitude.6 In particular, these effect sizes correspond roughly to annual consumption of an extra 12 cans of domestic beer, an extra 37 cigarettes, and an extra 118 candy bars, assuming prices of 1.8 soles per beer can, 8 soles per pack of cigarettes, and 0.5 soles per candy bar.

Table 3.

Policy impact on outcomes

| Alcohol | Tobacco | Sweets | Soft drinks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A. Budget shares (%)

| ||||

| Cross-section | 0.11*** | 0.01 | 0.10 | −0.17** |

| (0.04) | (0.02) | (0.07) | (0.09) | |

| [30,246] | [30,246] | [30,246] | [30,246] | |

| Panel | 0.17* | 0.11** | 0.45*** | −0.09 |

| (0.09) | (0.05) | (0.15) | (0.26) | |

| [9,046] | [9,046] | [9,046] | [9,046] | |

|

| ||||

| Panel B. Indicator for any expenditures

| ||||

| Cross-section | −0.0034 | 0.0008 | −0.0224 | −0.0177 |

| (0.0053) | (0.0074) | (0.0156) | (0.0145) | |

| [30,246] | [30,246] | [30,246] | [30,246] | |

| Panel | 0.0221 | 0.0266* | 0.0445 | 0.0168 |

| (0.0146) | (0.0157) | (0.0372) | (0.0350) | |

| [9,046] | [9,046] | [9,046] | [9,046] | |

|

| ||||

| Panel C. Conditional budget shares (%)

| ||||

| Cross-section | 2.49*** | 0.11 | 0.45*** | 0.00 |

| (0.78) | (0.19) | (0.12) | (0.15) | |

| [1,413] | [2,418] | [15,823] | [11,909] | |

| Panel | 3.23 | 1.46** | 0.65** | −0.18 |

| (5.28) | (0.74) | (0.29) | (0.40) | |

| [420] | [711] | [4,691] | [3,572] | |

Note: This table displays the impact of the policy change on outcomes for the cross-sectional and panel samples. The cross-sectional models include the covariates listed in Table A6 and fixed effects for year, region, and community type. The panel models include a quadratic for log(expenditures) and fixed effects for year and household. Robust standard errors, clustered at the district level, are shown in parentheses. Sample sizes are shown in brackets. The full regression output is provided in Appendix Tables A6 to A11.

Significance:

p < 0.01

p < 0.05

p < 0.10.

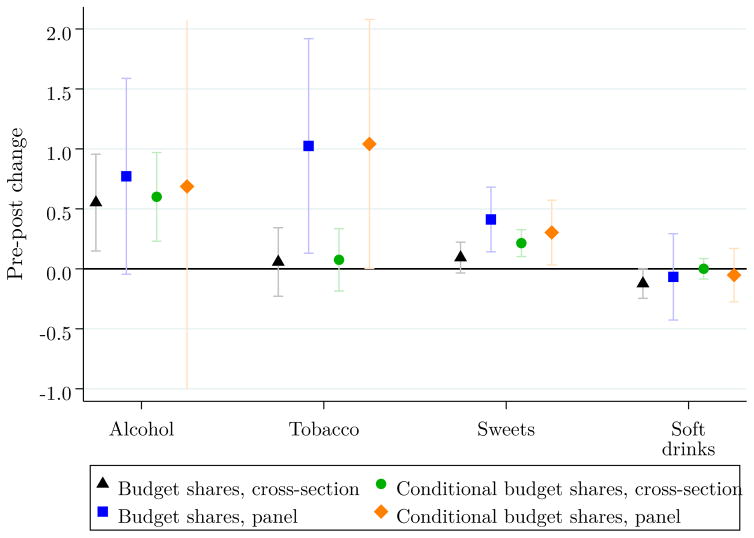

In Figure 2, we quantify the relative magnitude of the policy’s impacts by calculating the percentage change in each dependent variable. The relative increase in alcohol use amounts to 55%, and the relative decrease in soft drinks are 12%, respectively. Using the panel sample, we find that the decreased frequency of payments marginally increased alcohol expenditure shares by 77%, and significantly increased expenditures on tobacco shares by 102% and sweets shares by 41%. The non-effect for soft drinks could be due to selection bias, as we find different by-group trends in soft drink expenditures before the policy went into effect (Appendix Table A1).

Figure 2.

Relative change in outcomes following the policy change

Note: This figure shows the relative change in (conditional) budget shares in the post period, based on the regression results for the cross-sectional and panel samples in Table 3. The percentage change is calculated as the effect size divided by the mean of the dependent variable. Error bars represent a 95% confidence interval.

We next try to determine whether the effects are concentrated on the extensive (Panel B) or intensive (Panel C) margins. In Panel B of Table 3, we analyze the policy impact on an indicator for the purchase of any goods within the category. None of the coefficients reaches statistical significance at conventional levels. In Panel C of Table 3, we analyze the policy impact on conditional budget shares—that is, on the share of expenditures conditional on the purchase of any goods in the category—in order to measure the inframarginal effect. Using the cross-sectional sample, we find that the decreased frequency of payments significantly increased the conditional budget share for alcohol by 60% and sweets by 21%. Using the panel sample, the effects on conditional expenditure shares of alcohol and sweets are of similar magnitude: 68% for alcohol and 30% for sweets. We also observe a significant effect on conditional tobacco shares of 104%. None of the other conditional outcomes changed by a significant amount.

Figure 2 provides a visual summary of the main results. There is a consistent, positive effect of the policy change on budget shares spent on alcohol and sweets, and a positive effect for tobacco shares in the panel models only. The policy does not seem to have affected the budget shares spent on soft drinks. The similar magnitudes of estimated changes in budget shares and conditional budget shares suggest that the policy change operates principally on the intensive margin.

4.2 Decomposition of Changes in Budget Shares

We next decompose the total change in budget shares into the portions attributable to the extensive and intensive margins. Following McDonald and Moffitt (1980), we combine linear probability models of purchase or no purchase with OLS models of budget shares on the intensive margin to address selection into the purchase decision in two steps. First, we estimate a linear probability model of the probability of purchasing temptation goods during the recall period as a function of the covariates in Equation 1.7 Second, we estimate the expected budget shares conditional on positive budget shares as a function of these same variables. We then recover the total derivative of our outcome with respect to our treatment variable using the McDonald-Moffitt procedure described next.

Let E(y) be the expected value of outcome y; E(y*) be the expected value of y, conditional on y being greater than zero; and F(z) be the probability that y is greater than zero. Then, E(y) = F(z)E(y*). The total derivative of E(y) with respect to the treatment variable x is:

| (3) |

We can disaggregate the total change in y into two parts as represented by the two terms on the right-hand side of the equation: 1) the first term is the change in the intensive margin, or the change in y of those with positive expenditures; and 2) the second term is the change in the extensive margin, or the change in the probability of y > 0 weighted by the expected value of y if above zero. We repeat this procedure 400 times per temptation category and compute the bootstrapped standard errors.

We show the results of the decomposition in Table 4. The first column of results gives the total change in unconditional expected budget shares from before and after the policy change. The second and third columns of results decompose this unconditional change into changes along the extensive and intensive margins: the change in the expected probability of purchase from before and after the policy change, and the expected change in budget shares, given expenditures are greater than zero. The fourth column expresses the fraction of the unconditional change that is attributable to changes in the intensive margin. We find that all of the unconditional change in alcohol and sweets spending occurs on the intensive margin, as does 89% of the unconditional change in tobacco spending. The remaining category, soft drinks, did not experience significant increases in spending in the post-policy period, and the decomposition does not yield a significant change.

Table 4.

Decomposition of changes in budget shares

| Change in unconditional mean budget shares (%) | Change in budget shares on extensive margin (%) | Change in budget shares on intensive margin (%) | Change in intensive/change in total (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | 0.10*** | −0.01 | 0.12*** | 113.86 |

| (0.04) | (0.02) | (0.04) | ||

| Tobacco | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 88.67 |

| (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.01) | ||

| Sweets | 0.19*** | −0.05* | 0.24*** | 125.06 |

| (0.06) | (0.03) | (0.05) | ||

| Soft drinks | −0.06 | −0.06 | 0.00 | −0.72 |

| (0.06) | (0.04) | (0.05) |

Note: Bootstrapped standard errors with 400 repetitions are shown in parentheses.

Significance:

p < 0.01

p < 0.05

p < 0.10.

4.3 Robustness of the Results

We run a series of sensitivity analyses to determine the robustness of our results. In Panels A and B of Table 5, we check whether the results are robust to alternative measures of the outcome variables: annualized expenditures and annualized expenditures conditional on any purchases of the good. These outcome measures also have the benefit of being directly interpretable. The results are generally in line with our main findings, such that expenditures on alcohol and sweets remain positive and significant in most of the models. Expenditures conditional on any purchases increased by 70 to 125 soles for alcohol (equivalent to about 40 to 70 cans of domestic beer) and 10 to 33 soles for sweets. However, there are also some notable differences. Tobacco expenditures are not statistically significant across any of the models. In contrast, soft drink expenditures decreased by 27 to 48 soles among those households that purchased any soft drinks.

Table 5.

Robustness checks

| Alcohol | Tobacco | Sweets | Soft drinks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A. Expenditures

| ||||

| Cross-section | 1.337 | 0.044 | 2.100 | −15.433*** |

| (1.570) | (0.706) | (3.206) | (4.142) | |

| [30,246] | [30,246] | [30,246] | [30,246] | |

| Panel | 8.568* | 0.021 | 23.916*** | −17.962* |

| (4.458) | (1.451) | (8.390) | (9.970) | |

| [9,046] | [9,046] | [9,046] | [9,046] | |

|

| ||||

| Panel B. Conditional expenditures

| ||||

| Cross-section | 69.771** | 1.404 | 10.191** | −26.752*** |

| (33.008) | (8.031) | (4.579) | (7.737) | |

| [1,413] | [2,418] | [15,823] | [11,909] | |

| Panel | 124.537 | −25.291 | 32.898** | −48.194** |

| (225.483) | (27.263) | (14.405) | (20.996) | |

| [420] | [711] | [4,691] | [3,572] | |

|

| ||||

| Panel C. Budget shares (%), trimming propensity score at 5% and 95%

| ||||

| Cross-section | 0.07* | 0.02 | 0.09 | −0.14 |

| (0.04) | (0.02) | (0.08) | (0.10) | |

| [17,797] | [17,797] | [17,797] | [17,797] | |

| Panel | 0.17* | 0.14* | 0.56*** | −0.08 |

| (0.09) | (0.08) | (0.19) | (0.26) | |

| [5,477] | [5,477] | [5,477] | [5,477] | |

|

| ||||

| Panel D. Budget shares (%), immediate effects in 2010

| ||||

| Cross-section | 0.15*** | 0.03 | 0.16* | −0.05 |

| (0.06) | (0.02) | (0.10) | (0.12) | |

| [18,785] | [18,785] | [18,785] | [18,785] | |

| Panel | 0.16 | 0.14** | 0.46*** | 0.10 |

| (0.10) | (0.06) | (0.17) | (0.20) | |

| [7,686] | [7,686] | [7,686] | [7,686] | |

|

| ||||

| Panel E. Frequency of purchases per week

| ||||

| Cross-section | 0.2302 | - | 0.0764** | −0.0056 |

| (0.1458) | - | (0.0350) | (0.0233) | |

| [1,413] | [15,823] | [11,909] | ||

| Panel | 1.9361 | - | 0.1829** | −0.0263 |

| (1.6272) | - | (0.0896) | (0.0604) | |

| [420] | [4,691] | [3,572] | ||

|

| ||||

| Panel F. Expenditures

| ||||

| Transfers per capita | 0.0650*** | 0.0296*** | 0.0715** | 0.1227*** |

| (0.0234) | (0.0108) | (0.0311) | (0.0391) | |

| [30,246] | [30,246] | [30,246] | [30,246] | |

Note: The cross-sectional models include the covariates listed in Table A6 and fixed effects for year, region, and community type. The panel models include a quadratic for log(expenditures) and fixed effects for year and household. Robust standard errors, clustered at the district level, are shown in parentheses. Sample sizes are shown in brackets. Significance:

p < 0.01

p < 0.05

p < 0.10.

In Panel C of Table 5, we use an alternate rule for trimming the sample in order to achieve greater overlap of the propensity score distributions between the treatment group and control group.8 We do so by dropping all observations in either group with propensity scores less than 0.05 or greater than 0.95. This rule reduces the cross-sectional sample by 41% to 17,797 observations and the panel sample by 39% to 5,477 observations. Despite the smaller sample, the regression results are very similar.

One concern might be that our estimates of the treatment effect incorporate secular changes that occurred in the years following the benefits scheduling change. In order to test this assertion, we estimate the immediate effects of the scheduling change in the year after it went into effect. Panel D of Table 5 shows that the patterns are broadly similar when we restrict the post-policy period to 2010. In the cross-sectional sample, the effect on budget share spent on sweets achieves marginal statistical significance, whereas in the panel sample, the effect on the budget share spent on alcohol moves just beyond marginal significance.9

An important consideration for interpreting our main results is whether households substituted away from other goods as a result of the increased spending on alcohol and sweets during the post-policy period. In particular, increased spending on alcohol and sweets could driven by fewer purchases of “lumpy” durable goods, an artifact in the data unrelated to behavioral biases. We explore this issue in Appendix Table A16 by estimating the policy’s effect on budget shares for 12 categories of goods that, added together, comprise total spending. We see no evidence of increased spending on durables such as electronics, appliances, and vehicles. In fact, the budget share for electronics increased significantly for recipient households in the post-policy period. Thus, we rule out that the effects are due to changes in bulk purchasing of non-food products. We consider next changes in bulk food purchases and food storage in the post-policy period.

Our decomposition indicates that expenditures on the intensive margin drive the policy’s effects on alcohol, tobacco, and sweets. However, this result does not address whether consumers purchase these temptation goods more frequently, in larger quantities, or of a higher quality. ENAHO includes data on the frequency of purchases of foods consumed inside the home. Among our outcome variables, frequency data are available for alcohol, sweets, and soft drinks. We look at the frequency of purchases per week for each of these categories in Panel E of Table 5. After the benefits scheduling change went into effect, the frequency of sweets purchases increased significantly albeit by less than once per week. The point estimate for the frequency of alcohol purchases is larger and positive, but not statistically significant. These results indicate that bulk purchasing is not a driver of the increased temptation spending in the post-policy period, because bulk purchasing should lead to fewer purchases of larger quantitites. If anything, we find evidence of the opposite.

Finally, we use an alternate strategy to identify the intensive margin of treatment. Exploiting variation in household size, we identify the effect of transfer size per capita on household expenditures on temptation goods in the cross-sectional sample. The model takes the form:

| (4) |

where Transferit is the per-capita transfer amount and the dependent variable Xijt represents the total expenditures on goods in temptation category j. Each additional 100 soles of per-capita transfers—the amount paid per month—increases expenditures on alcohol and sweets by 7 soles, tobacco by 3 soles, and soft drinks by 12 soles (Panel F of Table 5). In practical terms, the effect sizes roughly translate into 4 cans of domestic beer, half a pack of cigarettes, and 6 cans of soda. These results rely on a similar identification strategy to some prior studies of temptation goods (Angelucci, 2008; Bazzi, Sumarto and Suryahadi, 2012; Schluter and Wahba, 2010), and reinforce that the amount of the transfer is an important factor affecting the consumption decision, along with the frequency of the transfer.

5 Discussion

This study evaluates the consequences of a decreased frequency of payments to benefits recipients in Peru’s CCT program. The advantages of evaluating this natural experiment include: district-by-district program eligibility permit a treatment/control design; the change in the frequency of payments did not alter the total transfer amount; the household data capture a rich set of temptation goods; and the policy under investigation suggests a concrete approach to tempering the amount of temptation purchasing undertaken by recipients.

We find that a decrease in the frequency of payments as a result of an exogenous policy change increased the consumption of certain temptation goods, notably alcohol and sweets. The changes appear to be concentrated on the intensive margin, as predicted. We find mixed support for an increase in the household budget spent on tobacco and no increase for soft drinks. Our difference-in-differences approach cannot fully rule out that the estimated impact of less frequent benefits scheduling is driven by unobserved differences between the control group and treatment group, although the results appear to be robust to several specification checks. The increased consumption of alcohol due to the frequency of transfers contrasts with the prior literature documenting no effect of cash transfers per se on temptation purchases (Evans and Popova, 2014). The welfare implications of the observed shifts in consumption are complicated because alcohol, tobacco, and sugar consumption can lead to habit formation.10 Present-biased individuals may not take fully into account the impact of habit formation on future welfare (Acland and Levy, 2015). Thus, optimal consumption rests on estimates of behavioral parameters for habit formation and present bias. Empirical estimates for present bias are generally not available, although the best available evidence indicates that consumers exhibit a high degree of present bias for tobacco and junk food (Gruber and Köszegi, 2001; Levy, 2010; Sadoff, Samek and Sprenger, 2015). Further empirical evidence could shed light on whether interventions designed to reduce temptation consumption are welfare enhancing.

A limitation of the analysis is that expenditures are reported by a single individual in the household, which may lead to measurement error of our outcome variable. Future studies might address the gender effects for temptation spending. In descriptive analyses (not shown), we find that male respondents report significantly more expenditures on alcohol by 77% and on tobacco by 50%, relative to female respondents, controlling for household size. This is highly indicative that female respondents systematically underreported expenditures on these temptation goods, perhaps because they were not fully aware of purchases made by male household members. Such mismeasurement of our dependent variables would decrease the precision with which the parameters are estimated, and it would mechanically bias the estimated coefficients toward zero. In contrast, the relative effect sizes reported in Figure 2 would not be subject to this bias. As such, we place greater confidence in the magnitudes of the relative effect sizes than the absolute effect sizes. Our relative effect estimates imply that alcohol expenditure shares increased by 55% to 80% following the policy change, and sweets expenditure shares increased by about 10% to 40%.

This study contributes to an important question in the literature: to what extent does the frequency of cash transfers stimulate the consumption of temptation goods? We show that the share of the household budget spent on alcohol and sweets does increase, and this result has implications for the overall effectiveness of the CCT program in Peru. The heterogeneity in the policy’s impact by type of temptation good could be reflective of several factors, including cultural influences on preferences for each good, price of each good, prevalence of consumption of each good, and potential misreporting. The study also raises a question that is theoretical in nature about how to model consumer behavior. Under the standard model, the permanent income hypothesis states that current consumption should not respond to predictable sources of income. If individuals are sensitive to the frequency of anticipated sources of income, it would suggest that economists should explore alternative models of consumer behavior, especially models that capture present-biased preferences.

Many types of temptation goods, including several of the ones under study here, are known to be risk factors for a variety of negative health outcomes. Behavioral scientists have long searched for interventions that might reduce the consumption of temptation goods, such as alcohol, tobacco, and sweets. Our study proposes and indirectly tests a particular approach to limiting the consumption of temptation goods. We find that less frequent payments lead households to purchase more alcohol and more sweets. The potential under-reporting in our sample challenges our ability to determine the cost-effectiveness of the benefits scheduling change. In programs such as Juntos, where the transfers are delivered to recipients by truck, the administrative costs incurred by the government may well outweigh any negative consequences of increased temptation purchases. In settings where benefits are delivered through electronic transfers, as is becoming increasingly common, the administrative costs of spreading payments throughout the benefits schedule would be much smaller. In such cases, the health benefits from reduced temptation consumption could offset the added administrative costs, making a more compelling argument for such a policy. Shapiro (2005) concludes that doubling the frequency of electronic transfers of food benefits in the U.S. would not justify the added administrative costs. His inquiry focuses solely on the effects of more frequent transfers on the quantity of calories consumed, ignoring any benefits from consuming fewer temptation goods. A next step is to investigate whether policies that increase the frequency of cash payments reduce the consumption of temptation goods, as our results indicate. In addition, analyses of individual-level data would help to parse which individuals in the household are responsible for temptation purchases and the intra-household allocation of resources. Both of these factors are important for understanding the welfare implications and health impacts of the change in benefits scheduling.

Appendix A

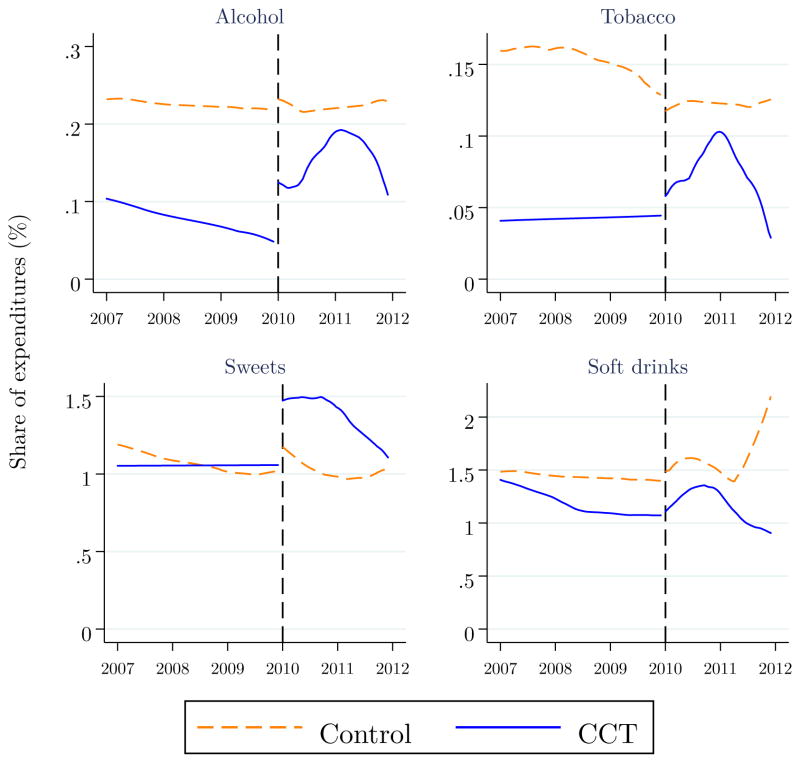

Figure A1.

Budget shares, by month and category (Panel sample)

Note: This figure fits a local polynomial smooth to the monthly trend for budget shares by category among the panel sample. Separate trends are plotted for the periods before and after the policy change.

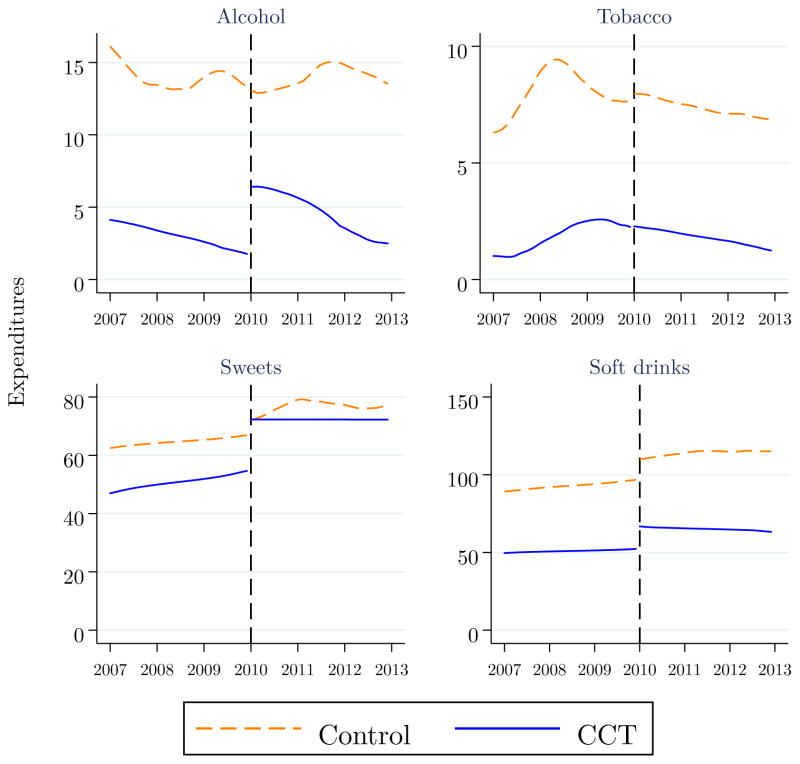

Figure A2.

Expenditures, by month and category (Cross-sectional sample)

Note: This figure fits a local polynomial smooth to the monthly trend for expenditures by category. Separate trends are plotted for the periods before and after the policy change.

Table A1.

Test of common trends assumption (Panel sample)

| Budget shares (%)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | Tobacco | Sweets Soft drinks | ||

| CCT | −0.09 | −0.15*** | −0.33 | −0.32 |

| (0.08) | (0.04) | (0.23) | (0.23) | |

| CCT × 2008 | −0.20 | 0.03 | 0.53** | −0.11 |

| (0.17) | (0.04) | (0.23) | (0.24) | |

| CCT × 2009 | −0.14 | 0.05 | 0.46* | 0.10 |

| (0.10) | (0.04) | (0.27) | (0.23) | |

| Year, ref = 2007 | ||||

| 2008 | 0.24 | 0.01 | −0.40** | 0.03 |

| (0.17) | (0.03) | (0.17) | (0.16) | |

| 2009 | 0.12 | −0.02 | −0.31 | −0.13 |

| (0.09) | (0.04) | (0.21) | (0.16) | |

| Constant | 14.15 | 0.11 | 16.05 | 0.72 |

| (9.84) | (0.86) | (18.68) | (3.43) | |

|

| ||||

| Household fixed effects | Yes | |||

| Number of observations | 5,107 | |||

| Number of districts | 359 | |||

Note: This table displays the differences between CCT recipient households and non-CCT district controls in the pre-policy change period among the panel sample. The coefficients on the interaction of the treatment indicator and year is an indication of whether the two groups have common trends before the policy change. The regressions also include a quadratic term for log(expenditures). Robust standard errors are clustered at the district level.

Significance:

p < 0.01

p < 0.05

p < 0.10.

Table A2.

Compositional changes (Cross-sectional sample)

| Control

|

Diff/SD | CCT

|

Diff/SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |||

| log(Expenditures) | 8.457 | 8.648 | 0.189 | 8.232 | 8.536 | 0.433 |

| Household size | 4.094 | 3.84 | −0.115 | 5.649 | 5.422 | −0.114 |

| Household members who are adult | 0.686 | 0.714 | 0.110 | 0.461 | 0.487 | 0.161 |

| Head is male | 0.815 | 0.803 | −0.031 | 0.855 | 0.843 | −0.033 |

| Education of head | ||||||

| None | 0.095 | 0.101 | 0.021 | 0.119 | 0.123 | 0.012 |

| Some primary | 0.544 | 0.532 | −0.024 | 0.635 | 0.63 | −0.010 |

| Some secondary | 0.278 | 0.281 | 0.007 | 0.227 | 0.229 | 0.005 |

| Some tertiary | 0.084 | 0.087 | 0.011 | 0.019 | 0.017 | −0.014 |

| Native language of head | ||||||

| Spanish | 0.619 | 0.620 | 0.002 | 0.300 | 0.315 | 0.032 |

| Quechua | 0.283 | 0.283 | 0.000 | 0.668 | 0.633 | −0.073 |

| Other | 0.099 | 0.098 | −0.003 | 0.032 | 0.051 | 0.095 |

| Marital status of head | ||||||

| Married or cohabiting | 0.739 | 0.712 | −0.060 | 0.852 | 0.836 | −0.044 |

| Widowed, divorced, or separated | 0.206 | 0.232 | 0.063 | 0.13 | 0.145 | 0.043 |

| Single | 0.055 | 0.056 | 0.006 | 0.018 | 0.02 | 0.010 |

| Respondent is male | 0.288 | 0.266 | −0.049 | 0.208 | 0.152 | −0.147 |

| District poverty | 0.063 | 0.056 | −0.152 | 0.107 | 0.094 | −0.315 |

| Community type | ||||||

| Rural, 0–140 residents | 0.163 | 0.163 | 0.000 | 0.196 | 0.184 | −0.031 |

| Rural, 141–400 residents | 0.487 | 0.475 | −0.024 | 0.67 | 0.675 | 0.011 |

| Urban, 0–400 residents | 0.166 | 0.171 | 0.013 | 0.102 | 0.102 | 0.000 |

| Urban, 401–4,000 residents | 0.184 | 0.191 | 0.018 | 0.031 | 0.039 | 0.044 |

| Region | ||||||

| Highlands | 0.599 | 0.603 | 0.008 | 0.929 | 0.899 | −0.106 |

| Rainforest | 0.401 | 0.397 | −0.008 | 0.071 | 0.101 | 0.107 |

|

| ||||||

| Number of observations | 9,827 | 4,009 | 10,702 | 5,708 | ||

Note: This table displays the pre-post changes for non-CCT and CCT households in the cross-sectional sample. The magnitude of the compositional changes are expressed as the difference in means divided by the pooled standard deviation (Diff/SD).

Table A3.

Compositional changes (Panel sample)

| Control

|

Diff/SD | CCT

|

Diff/SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |||

| log(Expenditures) | 8.493 | 8.550 | 0.057 | 8.234 | 8.510 | 0.396 |

| Household size | 4.251 | 4.007 | −0.108 | 5.665 | 5.574 | −0.044 |

| Household members who are adult | 0.683 | 0.700 | 0.064 | 0.461 | 0.473 | 0.075 |

| Head is male | 0.813 | 0.815 | 0.005 | 0.860 | 0.836 | −0.067 |

| Education of head | ||||||

| None | 0.0868 | 0.101 | 0.048 | 0.112 | 0.124 | 0.037 |

| Some primary | 0.579 | 0.577 | −0.004 | 0.620 | 0.625 | 0.010 |

| Some secondary | 0.261 | 0.249 | −0.028 | 0.241 | 0.226 | −0.035 |

| Some tertiary | 0.074 | 0.073 | −0.004 | 0.027 | 0.025 | −0.013 |

| Native language of head | ||||||

| Spanish | 0.645 | 0.596 | −0.101 | 0.299 | 0.330 | 0.065 |

| Quechua | 0.264 | 0.297 | 0.074 | 0.665 | 0.610 | −0.115 |

| Other | 0.091 | 0.107 | 0.054 | 0.035 | 0.060 | 0.118 |

| Marital status of head | ||||||

| Married or cohabiting | 0.746 | 0.732 | −0.032 | 0.860 | 0.827 | −0.091 |

| Widowed, divorced, or separated | 0.199 | 0.219 | 0.049 | 0.127 | 0.152 | 0.072 |

| Single | 0.055 | 0.049 | −0.023 | 0.013 | 0.020 | 0.063 |

| Respondent is male | 0.278 | 0.251 | −0.059 | 0.201 | 0.145 | −0.148 |

| District poverty | 0.063 | 0.054 | −0.257 | 0.108 | 0.094 | −0.438 |

| Community type | ||||||

| Rural, 0–140 residents | 0.148 | 0.169 | 0.058 | 0.202 | 0.207 | 0.012 |

| Rural, 141–400 residents | 0.516 | 0.513 | −0.006 | 0.703 | 0.662 | −0.088 |

| Urban, 0–400 residents | 0.156 | 0.168 | 0.033 | 0.0682 | 0.0915 | 0.085 |

| Urban, 401–4,000 residents | 0.180 | 0.150 | −0.080 | 0.027 | 0.039 | 0.067 |

| Region | ||||||

| Highlands | 0.598 | 0.627 | 0.059 | 0.925 | 0.889 | −0.125 |

| Rainforest | 0.402 | 0.373 | −0.059 | 0.075 | 0.111 | 0.125 |

|

| ||||||

| Number of observations | 3524 | 2508 | 1583 | 1431 | ||

Note: This table displays the pre-post changes for non-CCT and CCT households in the panel sample. The magnitude of the compositional changes are expressed as the difference in means divided by the pooled standard deviation (Diff/SD).

Table A4.

Difference-in-difference estimates of the policy’s impact on budget shares (Cross-sectional sample)

| Pre | Post | Time difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Budget share spent on alcohol (%) | |||

| CCT | 0.067 | 0.086 | 0.019 |

| (0.011) | (0.015) | (0.018) | |

| Control | 0.288 | 0.211 | −0.078 |

| (0.037) | (0.021) | (0.035) | |

|

| |||

| Group difference | −0.221 | −0.125 | |

| (0.039) | (0.026) | ||

|

|

|||

| Difference-in-difference | 0.097** | ||

| (0.039) | |||

| B. Budget share spent on tobacco (%) | |||

| CCT | 0.046 | 0.039 | −0.007 |

| (0.008) | (0.007) | (0.008) | |

| Control | 0.154 | 0.146 | −0.008 |

| (0.017) | (0.018) | (0.017) | |

|

| |||

| Group difference | −0.107 | −0.107 | |

| (0.019) | (0.019) | ||

|

|

|||

| Difference-in-difference | 0.001 | ||

| (0.018) | |||

| C. Budget share spent on sweets (%) | |||

| CCT | 1.136 | 1.223 | 0.086 |

| (0.042) | (0.046) | (0.052) | |

| Control | 1.083 | 1.057 | −0.026 |

| (0.068) | (0.051) | (0.050) | |

|

| |||

| Group difference | 0.053 | 0.166 | |

| (0.080) | (0.069) | ||

|

|

|||

| Difference-in-difference | 0.113 | ||

| (0.072) | |||

| D. Budget share spent on soft drinks (%) | |||

| CCT | 1.096 | 1.015 | −0.081 |

| (0.051) | (0.039) | (0.052) | |

| Control | 1.484 | 1.566 | 0.082 |

| (0.063) | (0.078) | (0.070) | |

|

| |||

| Group difference | −0.388 | −0.552 | |

| (0.081) | (0.087) | ||

|

|

|||

| Difference-in-difference | −0.163* | ||

| (0.087) | |||

Note: Robust standard errors, clustered by district, are in parentheses.

Significance:

p < 0.01

p < 0.05

p < 0.10.

Table A5.

Difference-in-difference estimates of the policy’s impact on budget shares (Panel sample)

| Pre | Post | Time difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Budget share spent on alcohol (%) | |||

| CCT | 0.073 | 0.133 | 0.060 |

| (0.021) | (0.133) | (0.060) | |

| Control | 0.328 | 0.204 | −0.125 |

| (0.067) | (0.038) | (0.071) | |

|

| |||

| Group difference | −0.255 | −0.071 | |

| (0.070) | (0.053) | ||

|

|

|||

| Difference-in-difference | 0.184** | ||

| (0.081) | |||

| B. Budget share spent on tobacco (%) | |||

| CCT | 0.044 | 0.064 | 0.020 |

| (0.013) | (0.019) | (0.016) | |

| Control | 0.146 | 0.129 | −0.017 |

| (0.023) | (0.025) | (0.031) | |

|

| |||

| Group difference | −0.102 | −0.065 | |

| (0.026) | (0.031) | ||

|

|

|||

| Difference-in-difference | 0.037 | ||

| (0.035) | |||

| C. Budget share spent on sweets (%) | |||

| CCT | 1.051 | 1.348 | 0.298 |

| (0.060) | (0.074) | (0.084) | |

| Control | 1.062 | 1.062 | 0.001 |

| (0.105) | (0.089) | (0.124) | |

|

| |||

| Group difference | −0.011 | 0.286 | |

| (0.121) | (0.116) | ||

|

|

|||

| Difference-in-difference | 0.397** | ||

| (0.150) | |||

| D. Budget share spent on soft drinks (%) | |||

| CCT | 1.110 | 1.188 | 0.078 |

| (0.080) | (0.071) | (0.097) | |

| Control | 1.452 | 1.627 | 0.175 |

| (0.092) | (0.136) | (0.148) | |

|

| |||

| Group difference | −0.341 | −0.438 | |

| (0.122) | (0.153) | ||

|

|

|||

| Difference-in-difference | −0.097 | ||

| (0.176) | |||

Note: Robust standard errors, clustered by district, are in parentheses.

Significance:

p < 0.01

p < 0.05

p < 0.10.

Figure A3.

Propensity score distributions (Cross-sectional sample)

Note: This figure shows the propensity score distribution using a rule that trims observations in each group above the maximum or below the minimum in the other group (left) and a rule that trims the outer 5% from the tails of the distribution (right).

Table A6.

Policy effects on budget shares (Cross-sectional sample)

| Budget shares (%)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | Tobacco | Sweets | Soft drinks | |

| CCT | −0.19*** | −0.05* | −0.02 | −0.22** |

| (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.13) | (0.09) | |

| CCT × Post | 0.11*** | 0.01 | 0.10 | −0.17** |

| (0.04) | (0.02) | (0.07) | (0.09) | |

| log(Expenditures) | −0.67* | −0.41 | −1.57 | −0.17 |

| (0.36) | (0.32) | (0.96) | (0.80) | |

| log(Expenditures)2 | 0.04* | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.00 |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.06) | (0.05) | |

| Household size | 0.00 | 0.01*** | −0.06*** | −0.03** |

| (0.01) | 0.00 | (0.01) | (0.01) | |

| % of adults in household | 0.06 | 0.03 | −0.79*** | −0.16 |

| (0.05) | (0.03) | (0.12) | (0.11) | |

| Head is male | 0.35*** | 0.17*** | −0.01 | 0.43*** |

| (0.06) | (0.03) | (0.08) | (0.10) | |

| Education, ref = none | ||||

| Some primary | −0.04 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| (0.08) | (0.03) | (0.07) | (0.09) | |

| Some secondary | −0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| (0.08) | (0.03) | (0.07) | (0.09) | |

| Some tertiary | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.26** |

| (0.09) | (0.03) | (0.09) | (0.11) | |

| Language, ref = Spanish | ||||

| Quechua | 0.04 | −0.06*** | −0.07 | −0.11 |

| (0.04) | (0.02) | (0.06) | (0.09) | |

| Other | −0.12* | −0.03 | −0.06 | 0.06 |

| (0.07) | (0.05) | (0.12) | (0.17) | |

| Marital status, ref = married | ||||

| Widowed, divorced, or separated | 0.18*** | 0.10*** | −0.03 | 0.19* |

| (0.06) | (0.03) | (0.08) | (0.11) | |

| Single | 0.13 | 0.07** | 0.28 | 0.18 |

| (0.08) | (0.03) | (0.19) | (0.13) | |

| Respondent is male | 0.11*** | 0.02 | −0.12*** | 0.32*** |

| (0.04) | (0.01) | (0.04) | (0.05) | |

| District poverty | −0.47 | −0.09 | −0.95* | −2.17*** |

| (0.32) | (0.17) | (0.54) | (0.81) | |

| Constant | 3.08** | 1.87 | 9.83** | 2.22 |

| (1.51) | (1.33) | (4.02) | (3.44) | |

|

| ||||

| Year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Region fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Community type fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Number of observations | 30,246 | 30,246 | 30,246 | 30,246 |

| Number of districts | 737 | 737 | 737 | 737 |

| Mean of dependent variable | 0.19 | 0.12 | 1.11 | 1.37 |

Note: This table displays the impact of the policy change on budget shares for the cross-sectional sample. Robust standard errors, clustered at the district level, are shown in parentheses.

Significance:

p < 0.01

p < 0.05

p < 0.10.

Table A7.

Policy effects on budget shares (Panel sample)

| Budget shares (%)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | Tobacco | Sweets | Soft drinks | |

| CCT × Post | 0.17* | 0.11** | 0.45*** | −0.09 |

| (0.09) | (0.05) | (0.15) | (0.26) | |

| log(Expenditures) | −1.3 | 0.1 | −0.56 | −5.22 |

| (1.60) | (0.14) | (0.98) | (4.36) | |

| log(Expenditures)2 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.29 |

| (0.09) | (0.01) | (0.06) | (0.26) | |

| Constant | 5.76 | −0.06 | 3.88 | 24.35 |

| (6.83) | (0.66) | (4.11) | (18.30) | |

|

| ||||

| Year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Household fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Number of observations | 9,046 | 9,046 | 9,046 | 9,046 |

| Number of clusters | 501 | 501 | 501 | 501 |

| Mean of dependent variable | 0.22 | 0.11 | 1.11 | 1.40 |

Note: This table displays the impact of the policy change on budget shares for the panel sample. Robust standard errors, clustered at the district level, are shown in parentheses.

Significance:

p < 0.01

p < 0.05

p < 0.10.

Table A8.

Policy effects on any category expenditures (Cross-sectional sample)

| Indicator for any expenditures

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | Tobacco | Sweets | Soft drinks | |

| CCT | −0.0203*** | −0.0318*** | 0.1169*** | 0.0160 |

| (0.0059) | (0.0100) | (0.0167) | (0.0139) | |

| CCT × Post | −0.0034 | 0.0008 | −0.0224 | −0.0177 |

| (0.0053) | (0.0074) | (0.0156) | (0.0145) | |

| log(Expenditures) | −0.0519*** | 0.006 | −0.0850*** | −0.0771*** |

| (0.0126) | (0.0161) | (0.0255) | (0.0237) | |

| log(Expenditures)2 | 0.0042*** | 0.0002 | 0.0152*** | 0.0147*** |

| (0.0008) | (0.0011) | (0.0017) | (0.0016) | |

| Household size | −0.0009 | 0.0055*** | −0.0216*** | −0.0160*** |

| (0.0008) | (0.0020) | (0.0021) | (0.0023) | |

| % of adults in household | 0.0009 | 0.0123 | −0.2711*** | −0.1116*** |

| (0.0070) | (0.0107) | (0.0183) | (0.0178) | |

| Head is male | 0.0410*** | 0.0559*** | 0.0088 | 0.0667*** |

| (0.0057) | (0.0074) | (0.0116) | (0.0115) | |

| Education, ref = none | ||||

| Some primary | −0.0087* | −0.0107** | 0.0072 | 0.0105 |

| (0.0047) | (0.0053) | (0.0107) | (0.0099) | |

| Some secondary | −0.0166*** | −0.0191*** | 0.0098 | 0.0027 |

| (0.0052) | (0.0071) | (0.0125) | (0.0116) | |

| Some tertiary | −0.008 | −0.0429*** | 0.0062 | −0.0581*** |

| (0.0075) | (0.0093) | (0.0163) | (0.0172) | |

| Language, ref = Spanish | ||||

| Quechua | 0.0134*** | −0.0238*** | 0.0110 | 0.0255** |

| (0.0051) | (0.0069) | (0.0125) | (0.0100) | |

| Other | −0.0064 | −0.0087 | 0.0455 | 0.0827*** |

| (0.0077) | (0.0170) | (0.0310) | (0.0171) | |

| Marital status, ref = married | ||||

| Widowed, divorced, or separated | 0.0159*** | 0.0158** | −0.0076 | 0.0359*** |

| (0.0056) | (0.0068) | (0.0109) | (0.0108) | |

| Single | 0.0108 | 0.0170* | 0.0027 | 0.0559*** |

| (0.0074) | (0.0089) | (0.0167) | (0.0150) | |

| Respondent is male | 0.0153*** | 0.0115** | −0.0503*** | 0.0400*** |

| (0.0039) | (0.0051) | (0.0079) | (0.0079) | |

| District poverty | −0.0387 | 0.0439 | −0.0958 | −0.1536 |

| (0.0402) | (0.0682) | (0.1136) | (0.0977) | |

| Constant | 0.1591*** | −0.0624 | 0.4091*** | −0.0539 |

| (0.0496) | (0.0653) | (0.1005) | (0.0959) | |

|

| ||||

| Year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Region fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Community type fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Number of observations | 30,246 | 30,246 | 30,246 | 30,246 |

| Number of districts | 737 | 737 | 737 | 737 |

| Mean of dependent variable | 0.0467 | 0.0799 | 0.5231 | 0.3937 |

Note: This table displays the impact of the policy change on an indicator variable for any expenditures of the category for the cross-sectional sample. Robust standard errors, clustered at the district level, are shown in parentheses. Significance:

p < 0.01

p < 0.05

p < 0.10.

Table A9.

Policy effects on any category expenditures (Panel sample)

| Indicator for any expenditures

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | Tobacco | Sweets | Soft drinks | |

| CCT × Post | 0.0221 | 0.0266* | 0.0445 | 0.0168 |

| (0.0146) | (0.0157) | (0.0372) | (0.0350) | |

| log(Expenditures) | −0.0573 | −0.0033 | 0.0548 | −0.1666** |

| (0.0413) | (0.0395) | (0.0862) | (0.0798) | |

| log(Expenditures)2 | 0.0048* | 0.0017 | 0.0058 | 0.0200*** |

| (0.0026) | (0.0025) | (0.0055) | (0.0050) | |

| Constant | 0.1839 | −0.0102 | −0.3607 | 0.3306 |

| (0.1648) | (0.1578) | (0.3436) | (0.3271) | |

|

| ||||

| Year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Household fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Number of observations | 9,046 | 9,046 | 9,046 | 9,046 |

| Number of clusters | 501 | 501 | 501 | 501 |

| Mean of dependent variable | 0.0464 | 0.0786 | 0.5186 | 0.3949 |

Note: This table displays the impact of the policy change on an indicator variable for any expenditures of the category for the panel sample. Robust standard errors, clustered at the district level, are shown in parentheses.

Significance:

p < 0.01

p < 0.05

p < 0.10.

Table A10.

Policy effects on conditional budget shares (Cross-sectional sample)

| Conditional budget shares (%)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | Tobacco | Sweets | Soft drinks | |

| CCT | −2.21*** | −0.09 | −0.63*** | −0.89*** |

| (0.58) | (0.13) | (0.06) | (0.10) | |

| CCT × Post | 2.42*** | 0.08 | 0.46*** | 0.02 |

| (0.69) | (0.16) | (0.07) | (0.11) | |

| log(Expenditures) | −33.05*** | −19.63*** | −20.12*** | −3.061*** |

| (1.79) | (0.45) | (0.28) | (0.50) | |

| log(Expenditures)2 | 1.75*** | 1.07*** | 1.09*** | 1.62*** |

| (0.11) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.03) | |

| Household size | 0.06 | 0.04** | −0.02 | 0.07*** |

| (0.10) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.02) | |

| % of adults in household | 0.58 | 0.44*** | −0.63*** | −0.24 |

| (0.80) | (0.17) | (0.10) | (0.15) | |

| Head is male | 1.24** | 0.25* | 0.15** | 0.27** |

| (0.58) | (0.14) | (0.07) | (0.11) | |

| Education, ref = none | ||||

| Some primary | 0.04 | 0.23* | 0.18*** | −0.10 |