Abstract

Sigma-1 receptors (σ1Rs) are structurally unique intracellular proteins that function as chaperones. σ1Rs translocate from the mitochondria-associated membrane to other sub-cellular compartments, and can influence a host of targets, including ion channels, G-protein-coupled receptors, lipids, and other signaling proteins. Drugs binding to σRs can induce or block the actions of σRs. Studies indicate that stimulant self-administration induces reinforcing effects of σR agonists, due to dopamine transporter actions. Once established the reinforcing effects of σR agonists are independent of dopaminergic mechanisms traditionally thought to be critical in the reinforcing effects of stimulants. Self-administered doses of σR agonists do not increase dopamine concentrations in the nucleus accumbens shell, a transmitter and brain region considered important for reinforcing effects of abused drugs. However, the self-administration of σR agonists is blocked by σR antagonists. Several effects of stimulants have been blocked by σR antagonists, including reinforcing effects assessed by a place-conditioning procedure. However, the self-administration of stimulants is largely unaffected by σR antagonists, indicating fundamental differences in the mechanisms underlying these two procedures used to assess reinforcing effects. When σR antagonists are administered in combination with dopamine uptake inhibitors an effective and specific blockade of stimulant self-administration is obtained. Actions of stimulant drugs related to their abuse induce unique changes in σR activity and the changes induced potentially create redundant, and once established, independent reinforcement pathways. Concomitant targeting of both dopaminergic pathways and σR proteins produces a selective antagonism of stimulant self-administration, suggesting new avenues for combination chemotherapies to specifically combat stimulant abuse.

Keywords: σRs, chaperone protein, drug abuse, cocaine, methamphetamine, self-administration, reinforcing effects

Introduction

The present paper focuses on the involvement of sigma receptors (σRs) in psychomotor stimulant abuse and the potential of the plasticity of these receptors to be involved in changes that occur with long-term use that are the basis for phenomena that come under the umbrella of the term “addiction.” There have been a number of excellent comprehensive and recent reviews that have focused more broadly on σRs (e.g. Maurice and Su, 2009; Zamanillo et al., 2012), as well as a number of previous reviews of the behavioral effects of various ligands for the σR (e.g. Leonard, 2004; Skuza and Wedzony, 2004). The interested reader is referred to those papers for a more comprehensive overview and an introduction to the literature on the behavioral pharmacology of σRs.

The scientific literature on σRs traces back to the proposal by Martin and colleagues (Martin et al., 1976) that σRs were a subtype of opioid receptor that were responsible for “psychotomimetic” effects of various opioid agonists observed in the spinal dog preparation. The prototype agonist for these effects was the benzomorphan derivative, SKF 10,047. Subsequent studies of the pharmacology of SKF 10,047 indicated differences in the pharmacology of its enantiomers, and that the psychotomimetic effects of SKF 10,047 were not antagonized by the opioid-receptor antagonist, naloxone (Vaupel, 1983). Confusion regarding the pharmacology of various putative σR ligands including SKF 10,047, resulted from affinity for the 1-(1-phenylcyclohexyl)piperidine (PCP) binding site within the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptor complex (Quirion, et al., 1981), and similar behavioral effects of putative σR drugs and PCP (Holtzman, 1982). The subsequent identification and characterization of more selective ligands, including dizocilpine for the PCP site (Wong et al., 1986) and 1,3 di-o-tolylguanidine (DTG) for sigma sites (Weber et al, 1986) allowed for the pharmacological identification of σR sites that were unique from other known binding sites in the central nervous system (see (Matsumoto et al., (1986) for a review).

Pharmacological and molecular studies have distinguished two subtypes of σRs. The σ1R has been cloned and characterized as a 25 kDa single polypeptide having no homology with any other known mammalian proteins. Recent studies have indicated that σ1Rs are expressed throughout the CNS and have been implicated in a variety of physiological functions and disease states (Maurice and Su, 2009). The σ2R, a 18–21 kDa protein, was first proposed on the basis of photoaffinity labeling studies using a DTG analog (Hellewell and Bowen, 1990). Recently, progesterone receptor membrane component-1 (PGRMC-1) was identified as the potential molecular entity of σ2R (Xu et al., 2011). Although there is ongoing debate on the bona fide identity of the σ2R (Ruoho, 2013), this finding will significantly drive further explorations on the identity and physiological function of σ2Rs.

Current Understanding of σ1Rs: Structure, Molecular Function and Subcellular Distribution

The σ1R is predominantly expressed at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and is an integral membrane protein with two transmembrane domains at the N-terminus and the center of the protein (Hayashi and Su, 2007). The σ1R shares no homology with any mammalian proteins, but shares 30% identity with a yeast C8-C7 sterol isomerase (Hanner et al., 1996). The second transmembrane domain of the σ1R shares over 80% identity with the sterol-binding pocket of sterol isomerase (Hanner et al., 1996), supporting the hypothesis that the σ1R is a sterol-binding protein utilizing the membrane-embedded domain for association with lipid ligands.

The σ1R C-terminus has chaperone activity that prevents protein aggregation (Hayashi and Su, 2007). It has been suggested that the chaperone domain resides in the lumen of the ER, stabilizing ER lumenal or membrane proteins (Hayashi and Su, 2007). Chaperone activity of σ1Rs is regulated by a direct protein-protein interaction with binding immunoglobulin protein/78 kDa glucose-regulated protein (BiP/GRP-78), another ER chaperone (Hayashi and Su, 2007) (Figure 1). Depletion of Ca2+ in the ER, or activation of IP3 receptors via Gq-coupled metabotrophic receptors at the plasma membrane induces a dissociation of σ1Rs and BiP (Hayashi and Su, 2007; Hayashi et al, 2011). Further, oxidative stress can also regulate the association between BiP and σ1R (Hayashi et al., 2011). Thus, a wide range of neuronal activities which lead to oxidative stress or Ca2+ mobilization contribute to the dissociation of the σ1R from BiP.

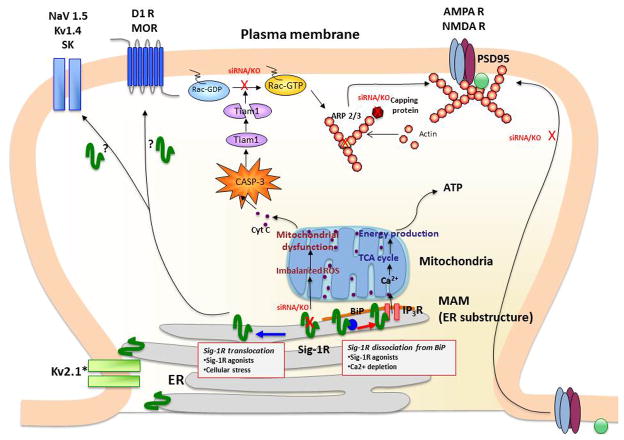

Figure 1.

σ1Rs are ER proteins highly clustered at the mitochondria-associated ER membrane (MAM). Under un-stressed conditions, σ1Rs regulate IP3 receptor-mediated Ca2+ mobilization at the MAM. Ca2+ directly influxed from MAM to mitochondria activates ATP production. When σ1Rs at the MAM are depleted in neurons, this causes various mitochondrial dysfunctions, including aggregated mitochondria, membrane potential changes and increased ROS production. These are followed by cytochrome c release and the activation of caspase-3. The activated caspase-3 induces the cleavage and inactivation of the Rac 1 specific GEF Tiam1, leading to the failure of Rac GDP switching to Rac GTP. The failure of the Tiam1-Rac pathway causes the disrupted cytoskeleton network and actin polymerization, that partly involves reduced activities of capping proteins and branching proteins Arp2/3. Consequently, neurons depleted of σ1Rs fail to promote maturation of dendritic spines and recruitment of AMPA/NMDA to post-synaptic membranes as evident of those receptors remained in the dendritic shaft. σ1Rs may also modulate post-synaptic proteins, including a variety of ion channels (Na+, K+ channels) and G protein-coupled receptors (DA D2, μ opioid receptors), by translocating to the proximity of postsynaptic density. Used with permission of the authors (Katz et al., 2011).

A unique characteristic of σ1Rs is that their chaperone actions can be induced by synthetic exogenous ligands, as well as cations (Hayashi and Su, 2007). Further, an endogenous ligand, N,N-dimethyltryptamine has been proposed (Fontanilla et al., 2009). Drugs identified as σ1R agonists induce a dissociation of σ1Rs and BiP (Hayashi and Su, 2007; Hayashi et al, 2011). Additionally, ligands exist that can block the effects of those compounds that induce chaperone actions in an agonist-antagonist manner (Hayashi and Su, 2007; Hayashi et al, 2011) (Figure 1).

One major locus of σ1R clustering is a subdomain of ER which is associated with mitochondria (mitochondria-associated ER membrane: MAM) (Hayashi and Su, 2007) (Figure 1). At the MAM the ER directly provides Ca2+ to mitochondria via IP3 receptors and transports phospholipids and sterols to mitochondria (Hayashi et al., 2009). The Ca2+ provided to mitochondria activates the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and ATP synthesis (Rizzuto et al., 1999). σ1R chaperoning IP3 receptors at the MAM potentiates Ca2+ influx from the MAM to mitochondria (Hayashi and Su, 2007), thus likely regulating mitochondrial bioenergetics and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation (Figure 1).

Other loci of σ1R clustering are the thin layers of ER cisternae adjacent to the post-synaptic plasma membranes of the ventral horn spinal motor neurons (Mavlyutov et al., 2010). The post-synaptic clusters of σ1Rs are specific to cholinergic synapses (Mavlyutov et al., 2010). Thus, in specific neuron types, σ1Rs are constitutively expressed at the ER subdomains opposing the plasma membrane (Figure 1). Similar plasma membrane clustering of σ1Rs was observed in living NG108 neuroblastoma x glioma hybrid cells when enhanced yellow fluorescent protein-tagged σ1Rs were expressed (Hayashi and Su, 2007).

σ1R Regulation of Plasma Membrane Proteins

The elucidation of molecular mechanism by which σ1Rs regulate plasma membrane events is expanding as various novel roles for σ1R regulation of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and ion channels (Aydar et al., 2002; Navarro et al., 2010) are documented. σ1Rs tonically regulate activity of potassium, NMDA, and sodium channels (Aydar et al., 2002; Fontanilla et al., 2009; Martina et al., 2007) (Figure 1). Recent studies indicate possible interactions between σ1Rs and GPCRs, such as μ opioid and DA receptors (Kim et al., 2010; Navarro et al., 2010) (Figure 1). In light of the nature of molecular chaperones, studies suggest that σ1Rs regulate plasma membrane proteins via physical protein-protein interactions (Aydar et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2012; Navarro et al, 2010). Although further studies are essential for clarification, growing evidence from recent molecular and cell biological studies is beginning to elucidate possible mechanisms that may in part explain plasma membrane actions of σ1Rs.

Change in MAM Loci

At the MAM, σ1Rs are normally highly stationary (Hayashi and Su, 2003), possibly due to their tight association with cholesterol/ceramide-rich lipid microdomains (Hayashi and Fujimoto, 2010). With cellular stress or binding of agonists, σ1Rs become mobile at the ER membrane (Morin-Surn et al., 1999; Hayashi and Su, 2003) moving along the membrane from deep intracellular loci (e.g., MAM) to more peripheral subcellular ER locations (Figure 1) (Hayashi and Su, 2003). Greater than 70% of σ1Rs localized on membranes other than the MAM (e.g., ER membranes in neurites) are highly mobile, with a mobility speed that can reach approximately 8–10 μm/min (Hayashi and Su, 2003, 2007). With ligand binding, σ1Rs redistribute from detergent-insoluble lipid microdomains to soluble membrane domains (Hayashi and Su, 2003; Palmer et al., 2007), gaining mobility at the ER. The resulting peripherally distributed σ1Rs (e.g., σ1Rs at cholinergic synapses of motor neurons (Mavlyutov et al., 2010) may reach close proximity to the plasma membrane and physically associate with proteins at the plasma membrane (Figure 1).

Translocation from ER or Release

Some ER chaperones are known to translocate from ER to other intracellular organelles, or be released extracellularly (Sun et al., 2006; Johnson et al, 2001). The translocation of ER chaperones involves a hindrance of an ER retention/retrieval motif via protein-protein interactions (Johnson et al., 2001; Crofts et al., 1998). Localization of σ1Rs at the ER may be determined by the double-arginine ER retention motif at the N-terminus of the protein that is utilized for a retrieval of ER proteins from a coat protein complex-I operated ER-Golgi secretory pathway to the ER. The wild-type σ1Rs are indeed co-immunoprecipitated with COP-I, a protein complex that coats vesicles for retrograde transport from Golgi to the ER and between Golgi compartments. This finding indicates that σ1Rs are actively retrieved from the ER-Golgi secretory pathway to the ER. The deletion of the double-arginine motif produces an exclusive relocation of σ1Rs from ER to the cytoplasm or cytosolic lipid droplet-like structures (Hayashi and Su, 2003). In contrast, mutations at the double-arginine motif disrupt the association of σ1Rs with COP-I (Sharma et al., 2010). The NMDA receptor NR1-1a subunit is also known to possess the triple-arginine ER retention motif (Yang et al., 2007). Whether the interaction of σ1Rs with ion channel subunits or GPCRs at the ER may hinder the double-arginine motif of σ1Rs, thus triggering the departure of the complex for the plasma membrane is an untested, but intriguing possibility.

Protein Folding

Virtually all plasma membrane proteins are originally synthesized in the ER. Newly synthesized proteins are properly folded through interactions with ER molecular chaperones, which is followed by the entering of the proteins into the ER-Golgi secretory pathway for further modification and delivery to final destinations (e.g., plasma membrane) (Schroder and Kaufman, 2005). A recent study demonstrated that the σ1R agonist, cutamesine, enhances the secretion of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) from neuroblastoma cells (Fujimoto et al., 2012).

Lipids comprising the transport vesicles control protein transport via the ER-Golgi secretory pathway (Sprong et al., 2001). Cholesterol and sphingolipids form lipid raft microdomains which play a pivotal role in trafficking and sorting of plasma membrane proteins at the ER and Golgi (Sprong et al., 2001). Importantly, recent studies indicate that σ1Rs regulate lipid transport at the ER, and lipid raft formation at the plasma membrane (Hayashi and Su, 2003, 2005; Takebayashi et al., 2004). These findings support a notion that activity of σ1Rs is involved in the transport of proteins as well as lipids between ER and plasma membranes. It should be noted that the transport of proteins from the ER to the plasma membrane is highly efficient, generally taking less than 30 min (Schroder and Kaufmann, 2005). Specifically, protein delivery at dendritic spines is thought to be much faster because the necessary machinery for protein synthesis and trafficking is packed in the ER (Aridor et at., 2004; Mu et al., 2003). Thus, it is plausible that σ1Rs may indirectly regulate the protein expression on the surface of neurons in a relatively short time frame by controlling protein transport.

Heteromers

In addition to altering protein folding, σ1Rs may interact with plasma membrane bound receptors as heterodimers. For example, Navarro et al. (2010) found that cocaine binding to σ1R influenced intracellular signaling induced by the dopamine D1 receptor agonist, SKF 81297. Further, D1Rs and σ1Rs were found to heteromerize in transfected cells, suggested by energy transfer in the absence of ligands in studies detected using Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer assays. Additionally, actions of cocaine mediated by σ1Rs may lead to an increase in the level of D1-σ1Rs heteromers (Navarro et al., 2010). Interestingly, a study by this same group also showed D2-σ1Rs heteromers, possibly heterotetramers, but that this interaction reduced D2R signaling (Navarro et al., 2013).

Regulation of Cell Morphology

Several studies have indicated that σ1Rs may affect a wide range of cellular functions by regulating cell morphologies. Neurite sprouting induced by nerve-growth factor in PC12 cells is enhanced by σ1R agonists (Takebayashi et al., 2002). Additionally, nerve growth factor as well as chronic treatment with σ1R agonists both up-regulated endogenous σ1R expression in PC12 cells (Takebayashi et al., 2002). A later, similar finding of nerve growth factor-induced neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells revealed that the σ1R agonist SA4503 stimulated σ1R binding to IP3 receptors, as well as the pathways downstream from trophic factor receptors that include PLC-γ, PI3K, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), JNK and Pas/Raf/MAPK (Nishimura et al., 2008).

Synaptic plasticity and the consequential effects on neuronal function are also influenced by σ1Rs. Aberrant morphologies were observed in hippocampal neurons with knockdown of σ1R by siRNAs (Tsai et al., 2009). Further, dendrite extension and branching during early stages of neuronal development were influenced by σ1Rs. With σ1Rs depletion by siRNAs in late stages neurons failed to form the mushroom-like spines as well as functional synapses that possess clustered assemblies of AMPA/NMDA receptors and postsynaptic density scaffolding protein PSD-95 (Tsai et al., 2009) (Figure 1). The aberrant morphologies caused by σ1R depletion were associated with malfunctions of mitochondria, followed by accumulation of ROS and activation of caspase-3 (CASP-3). In σ1R knockdown neurons, ROS-activated CASP-3 degrades T-lymphoma invasion and metastasis-inducing protein 1 (Tiam1) by proteolytic cleavages, thus subsequently reducing the active form of Rac1-GTP [50] (Figure 1). Further, the mitochondria dysfunction and aberrant neuronal morphogenesis produced by σ1R knockdown were blocked by ROS scavengers, such as Tempol and N-acetylcysteine (Tsai et al., 2009), indicating that σ1Rs are key modulators in maintaining the balance of oxidative stress in the neurons. A microarray analysis of rat primary neurons further demonstrated that σ1R knockdown produced alterations of a cluster of transcripts involved in remodeling of the actin-based cytoskeleton network. The transcripts include those of actin capping proteins and actin-related protein 2/3 (ARP2/3) (Tsai et al., 2010) (Figure 1). Together, these findings indicate that σ1Rs are important regulators of cellular morphology and neuronal plasticity at both the early (e.g., neurite sprouting, dendrite extension, and dendrite branching) and late (e.g., spine maturation, synaptogenesis) stages of neuronal differentiation.

σR Subtypes

A wide variety of structurally diverse compounds has been found to displace radioligands designed to selectively bind to σRs (Matsumoto, 2007; Itzhak, 1994). It has been generally accepted that the (+)-enantiomer of the benzomorphan, pentazocine, serves well as a radioligand for the σ1R (de Costa et al., 1989; Bowen et al., 1993). Unfortunately, there is no comparably selective ligand for characterizing the binding of ligands to the σ2 subtype. However, DTG (Weber et al., 1986) has been used in the presence of excess amounts of cold (+)-pentazocine to block σ1 sites and thus characterize σ2R binding. Sufficient progress has been made in characterizing the selectivity or lack thereof of various ligands using these assays (Matsumoto, 2007). Garcés-Ramírez et al. (Enomoto, 2003), and several other studies as per citations in Table 1, characterized the binding at σ1 and σ2 receptors of the several drugs used in the behavioral studies reviewed below. Those studies indicated that both PRE-084 and (+)-pentazocine were selective σ1R ligands whereas DTG, and BD 1008, BD 1047, and cocaine, were not selective among σR subtypes. In contrast, BD 1063 was preferential for σ1Rs, though it was only about 70-fold selective.

Table 1.

Inhibition by various compounds of specific binding to σ1, or σ2 receptors and the dopamine transporter. The values listed are Ki values with 95% confidence limits in parentheses, with exceptions as noted.

| Compound | σ1 Ki Value ± SEM (nM) or 95% CLs | σ2 Ki Value ± SEM (nM) or 95% CLs | DAT Ki Value ± SEM (nM) or 95% CLs | Original Report |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BD 1008 | 2.13 (1.77 – 2.56) | 16.6 (13.0 – 21.1) | 2,510 (2,250 – 2,790) | Garcés-Ramírez et al., 2010 |

| BD 1047 | 3.13 (2.68 – 3.65) | 47.5 (36.7 – 61.4) | 3,220 (2,820 – 3,670) | Garcés-Ramírez et al., 2010 |

| BD 1063 | 8.81 (7.15 – 10.9) | 625 (447 – 877) | 8,020 (7,100 – 9,060) | Garcés-Ramírez et al., 2010 |

| Cocaine | 5,190 (3,800 – 7,060) | 19,300 (16,000 – 23,300) | 76.6 (72.6 – 80.5) | Garcés-Ramírez et al., 2010 |

| DTG | 57.4 (49.3 – 66.7) | 21.9 (14.8 – 32.4) | 93,500 (80,00 – 109,000) | Garcés-Ramírez et al., 2010 |

| Methylphenidate | 6,780 (4,520 – 10,200) | 37,400 (21,200 – 66,100) | 65.8 (61.2 – 70.8) | Hiranita, JPET 2011 |

| Nomifensine | 8,240 (5,360 – 12,700) | 65,200 (54,300 – 78,300) | 21.0 (18.9 – 23.3) | Hiranita, JPET 2011 |

| (+)-Pentazocine | 4.59 (4.26 – 4.97) | 224 (195 – 257) | NT | Hiranita JPET 2013 |

| PRE-084 | 53.2 (44.8 – 63.2) | 32,100 (23,100 – 44,700) | 19,600 (17,600 – 21,900) | Garcés-Ramírez et al., 2010 |

| Rimcazole | 883 (661 – 1,180) | 238 (171 – 329) | 96.6 (77.3 – 121) | Hiranita, JPET 2011 |

| SH 3-24 | 22.9 (18.5 – 28.2) | 20.0 (15.7 – 25.6) | 12.2 (10.8 – 13.8) | Hiranita, JPET 2011 |

| SH 3-28 | 19.0 (15.3 – 23.6) | 47.2 (40.4 – 55.2) | 188 (166 – 213) | Hiranita, JPET 2011 |

| WIN 35,428 | 5,700 (4,060 – 8,020) | 4,160 (3,120 – 5,550) | 5.24* (4.92 – 5.57) | Hiranita, JPET 2011 |

The value for affinity of WIN 35,428 at the DAT, (+)-pentazocine at σ1, and DTG at σ2 receptors are Kd values obtained from homologous competition studies. The values reported for all compounds were determined using identical assay conditions. For the [3H]DTG assay, the data often modeled better for two than one binding site, and the Ki values for the higher affinity site are displayed in the table, as that site is the site recognized as the σ2 receptor. The low affinity site is currently not identified. Obtained values for the low affinity DTG site and their 95% confidence limits in nM were as follows: BD 1008: 20,500 (9,640 – 43,500); BD 1047: 55,300 (25,000 – 122,000); BD 1063: 53,700 (16,500 – 174,000).DTG 3,520 (257 – 48,20); Rimcazole: 25,900 (3,620 – 185,000); SH 3–24:12,700 (1,300 – 124,000).

Interactions Among σR Ligands and Stimulant Effects

A previous paper reviewed the effects of various σR ligands on neurotransmission by classically recognized neurotransmitters (Katz et al. 2011). Much of the literature has focused on dopaminergic effects of σR ligands (e.g. Gonzales -Alvear and Werling, 1994). As mentioned above, cocaine has affinity for σRs, a finding first reported by Sharkey et al. (1988). Although the affinity of cocaine for σRs is in the μM range, Sharkey et al. argued that concentrations in brain sufficient to bind to σRs would be reached at high doses of cocaine that produce acute toxic effects. Several studies have examined more closely interactions between cocaine and σR ligands. For example, the σR antagonists, rimcazole and BMY 14802 blocked cocaine-induced locomotor stimulation (Menkel et al., 1991). Other studies showed that sensitized locomotor responses to cocaine or methamphetamine were blocked by σR antagonists (Ujike et al., 1992; Witkin et al., 1993), and still other studies have found that the convulsive effects and lethality induced by cocaine are blocked by σR antagonists, and that σ1R antisense injected via indwelling cannulae to the lateral ventricles attenuated the convulsive and locomotor stimulant effects of cocaine, whereas a mismatch sequence was relatively less active (Liu et al., 2007).

σR Ligands and Reinforcing Effects of Stimulant Drugs

Though effects of σR antagonists on cocaine-induced locomotor stimulation have been well documented, fewer studies have examined σR involvement in the reinforcing effects of stimulants. Romieu et al., (2000, 2002, 2003) reported that the σR antagonists, NE 100, BD 1047 and progesterone blocked acquisition and expression of cocaine-induced place conditioning. Other σR antagonists reported to block place conditioning include the σ1 preferential antagonist, AC 927 (Matsumoto et al., 2011) and the slightly σ2 preferential antagonist, CM 156 (Xu et al., 2012). In addition, there is one report (Mori et al., 2014) that SA 4503, a σR agonist (Matsumoto, 2007) attenuates acquisition of place preference induced by morphine, cocaine and methamphetamine, whereas (+)-pentazocine was inactive, which begs the question of whether the effect was mediated by σRs.

Though σRs have been reported to block place conditioning induced by stimulants, the σR antagonist, BD 1047, failed to substantially affect cocaine self-administration across a range of doses from 1 to 30 mg/kg (Martin-Fardon et al., 2007). In a further assessment of reinstatement of cocaine self-administration induced by cocaine there were small effects of BD 1047. The absence of an effect of σR antagonists on cocaine self administration was replicated in a further study of several σR antagonists (BD 1047, BD 1008, BD 1063, AC 927, NE 100) across a range of cocaine doses (Hiranita et al., 2010, 2011).

The difference between outcomes in self administration and place conditioning may be due to the species studied. All of the studies detailed above showing effects of σR ligands, with the exception of the study by Mori et al. (2014), used mice, whereas the self-administration studies were conducted in rats. The difference may also be due to the indirect nature of assessment of reinforcing effects inherent in the place conditioning procedure. Further, the study by Martin-Fardon and colleagues (2007) assessed the effects of σR antagonists on established behavior, whereas the place conditioning studies assessed the effects of σR antagonists on the acquisition of the conditioned behavior. It would be of value to assess the effects of σR antagonists on the acquisition of self administration. Nonetheless, these seemingly disparate outcomes in procedures assessing “reinforcing” effects emphasize that a consideration of the methods used and the environmental circumstances surrounding the effects can be critical to the outcome. The behaviors expressed in self-administration, place-conditioning, and other procedures are a function of only marginally overlapping sets of variables, and as such, drugs can have quite different effects that depend on the conditions of the study.

In contrast to the negative results obtained with σR antagonists in rats trained to self-administer cocaine, pretreatment with the σR agonists, DTG and PRE-084, produced a dose-related potentiation of cocaine self administration, evidenced by a leftward shift in the cocaine dose-effect curve (Hiranita et al., 2010). PRE-084 was approximately three-fold more potent than DTG (Hiranita et al., 2010). This leftward shift, or potentiation of the self-administration of cocaine, was similar to the effects of dopamine uptake inhibitors on cocaine self-administration (Schenk et al., 2002; Barrett et al., 2004). Because the potentiation of cocaine self-administration by σR agonists was similar to that produced by dopamine uptake inhibitors which are themselves self-administered, whether σR agonists would be self-administered was subsequently tested. In subjects with a history of cocaine self-administration the σR receptor agonists, DTG and PRE-084, were self-administered when substituted for cocaine (Hiranita et al., 2010). PRE-084 was three times more potent than DTG when self-administered as it was when administered as a pretreatment to rats self-administering cocaine. The self-administration data stand in contradistinction to the lack of substantive effects of σR agonists when administered alone in behavioral procedures related to drug abuse, such as locomotor activation (Maj et al., 1996; Skuza and Rogóz, 2009) or place conditioning (Romieu et al., 2002; Mori et al., 2014).

The disconnect between results with self-administration and place conditioning is further substantiated with studies in which attempts were made to use σR ligands for place conditioning. In particular, the groundwork was laid with studies by Romieu et al. (2000, 2002, 2003) that reported negative results in place conditioning attempts with the standard σR agonists (e.g. PRE-084, igmesine, pregnenolone) and antagonists (e.g. BD 1047, NE 100, progesterone). Several other studies replicated these outcomes (e.g. Sage et al., 2013, Mori et al., 2012; Mori et al., 2014).

The substitution for cocaine by σR agonists raised the question of whether these drugs would be self-administered in experimentally naïve subjects. A study of the reinforcing effects of the σR agonists, PRE-084 and (+)-pentazocine, (Hiranita et al., 2013) was conducted with doses that previously maintained the highest rates of responding in cocaine experienced subjects (Hiranita et al., 2010). The initial exposure to i.v. σR agonist availability occurred over the course of 28 daily experimental sessions in which each response on the right lever in a two-lever experimental chamber produced either 0.32 mg/kg, i.v. injections of either PRE-084 or (+)-pentazocine in separate groups of rats. That number of sessions is about three-fold greater than that sufficient for the acquisition of cocaine self-administration under these same conditions. Nonetheless, there was no appreciable acquisition of self-administration of either σR agonist. In a subsequent phase of the study the potential for self-administration of a range of doses of PRE-084, from 0.1 to 10.0 mg/kg/inj, was assessed. Over that range there was no appreciable self-administration of the compound (data not shown).

Cocaine (0.32 mg/kg/inj) was subsequently made available for self-administration over the ensuing fourteen daily sessions in subjects that failed to acquire self-administration of either σR agonist. During those sessions, acquisition of cocaine self-administration was obtained with each response on the right lever producing a cocaine injection (data not shown). After cocaine self-administration was acquired and stable from one session to the next, PRE-084 or (+)-pentazocine (each at 0.32 mg/kg/inj) were substituted for cocaine in the subjects that previously failed to acquire self-administration of those drugs. In the very first session, and for 10 subsequent sessions, responding was well-maintained by either σR agonist on the right lever which previously produced cocaine injections (Figure 2a and 2b). In the next sequence of daily sessions, and for seven sessions in total, each response on the left lever, on which responses had never previously produced consequences, now produced injections of the σR agonists, and the right lever was no longer active. On the first of these sessions, subjects switched from virtually no responding on the left lever in the previous session to high rates of responding on this newly active lever (Figure 2a and 2b). Additionally, responding was virtually eliminated on the previously active right lever, and remained at low levels through the duration of that condition. In the next of the daily sessions, responses on neither of the levers had consequences and responding decreased to low rates on the left lever, and remained at low rates on the right lever (Figure 2a and 2b). Finally σR agonist injections were again made available for responses on the left lever and responding was promptly re-acquired (Figure 2a and 2b; Hiranita et al., 2013).

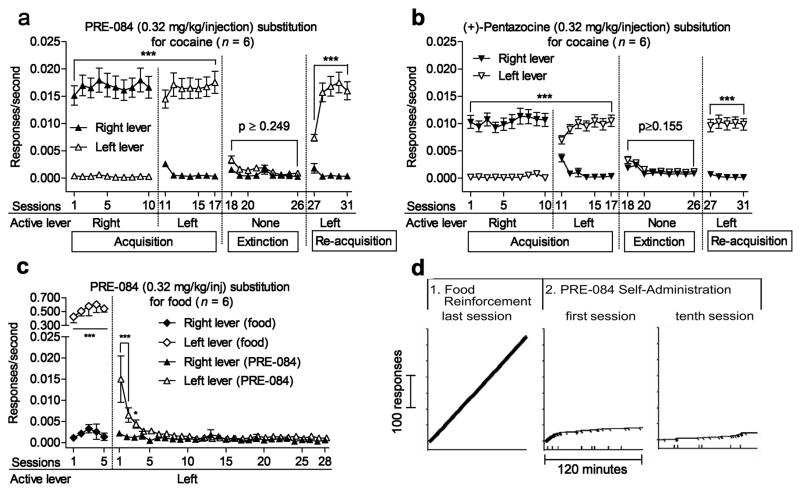

Figure 2.

Selective σ1R agonist self-administration after cocaine experience, but not after experience with food reinforcement. Each point represents the mean ±SEM of six subjects. a, b: Self-administration of selective σ1R agonists (a: PRE-084; b: (+)-pentazocine) when each response produced an injection. Reversal of active and inactive levers, extinction, and reacquisition each had the effects expected for a reinforcing agent. c: A food reinforcement history was not sufficient to induce reinforcing effects of PRE-084. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, compared with responding on the inactive lever (post-hoc Bonferroni t-test). d: Performances of a representative subject in real time: Horizontal axes represent time and the vertical axes represent cumulative responses. Each food presentation or PRE-084 injection produced a diagonal slash mark on the record. The first record is from the last session of responding maintained by food reinforcement with food presentations so frequent that the slash marks are contiguous and render the cumulative record a thick line. The second record is from the immediately following session, the first opportunity to self-administer 0.32 mg/kg/inj of PRE-084 after experience with food reinforcement. This record shows the extinction of responding previously maintained by food reinforcement. The record from the tenth session confirms no acquisition of PRE-084 self-administration. Adapted from Hiranita et al. (2013).

An analogous study was conducted with food-reinforced responding (Hiranita et al., 2013). Rats were trained on an FR 1-response schedule of food reinforcement on the left of the two response levers in the experimental chamber. The rats were then surgically catheterized, and then retrained with food reinforcement for another five daily sessions. On the next of the daily sessions each response on the left lever produced an injection of 0.32 mg/kg of PRE-084 rather than a food pellet. Over the course of the next five daily sessions response rates progressively declined to the point that response rates on the active and inactive (right) levers were similar (Figure 2c). Cumulative records of responding (Figure 2d) show the constant high rate of responding during the last session of food reinforcement, a negatively accelerated temporal pattern of responding during the first session of FR 1-response PRE-084 injection characteristic of extinction (e.g. Catania, 2013), and the low overall rate of occasional responding that was sustained for the remainder of the 28 daily sessions of FR 1-response PRE-084 injection. These results indicate that the maintenance of responding with PRE-084 was not simply due to high persistent rates of operant responding on which the schedule of σR agonist was superimposed. In addition, as the subjects received relatively large numbers of injections during the extinction of responding within the first several sessions of FR 1-response PRE-084 injection, the absence of sustained maintenance of responding with PRE-084 injections could not have been due to inadequate exposure to the contingency between responses and consequences.

The primary pharmacological mechanisms involved in the self administration of cocaine and σR agonists were contrasted in studies with dopamine and σR antagonists (Hiranita et al., 2013). Subjects were trained under an FR 5-response schedule of cocaine self-administration (each fifth response produced and injection) with doses increasing across components of the daily experimental sessions. In the first component responses had no scheduled consequences (extinction or EXT), whereas in subsequent components, that each followed a 2-min “timeout” period with all chamber lights off and no scheduled consequences for responses, the dose was increased from 0.03 to 1.0 mg/kg. Details of the procedure or similar ones have been published (Schenk et al., 2002; Barrett et al., 2004; Hiranita et al., 2009).

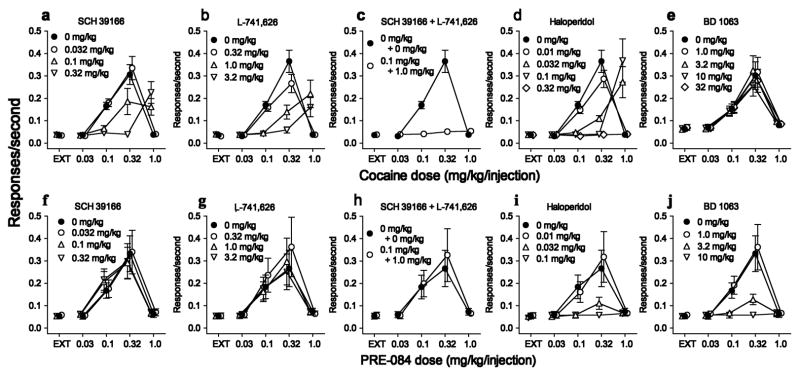

The dopamine D1 receptor antagonist, SCH 39166, produced dose-related rightward shifts in the cocaine self-administration dose-effect curve (Figure 3a). Similar antagonist effects were obtained with the dopamine D2 preferential antagonist, L741, 626; whereas combinations of minimally effective doses of SCH 39166 and L741, 626 produced an insurmountable antagonism across the range of cocaine doses studied (Figure 3b and 3c, respectively). The non-selective D1/D2 dopamine antagonist haloperidol also produced dose-related rightward shifts in the cocaine self-administration dose-effect curve (Figure 3d). In contrast, the σR antagonist BD 1063, consistent with previous reports (Hiranita et al., 2010), was inactive against cocaine self-administration over a range of doses from 1 to 32 mg/kg (Figure 3e).

Figure 3.

Sensitivity of cocaine self-administration, and insensitivity of PRE-084 self-administration, to dopamine receptor antagonism. Vertical axes: Responses per sec. Horizontal axes: Cocaine or PRE-084 injection dose in mg/kg, log scale. Rats (N=6) were trained to self-administer cocaine under a fixed-ratio five-response schedule of reinforcement. Sessions were divided into five 20-min components with different doses of cocaine available in successive components. Consequences of responding in the successive components were: nothing (extinction, EXT); and 0.032 – 1.0 mg/kg/injection in the subsequent four components. All antagonists except BD 1063 (5-min before sessions) were administered i.p., 30-min before sessions. Each point represents the mean ±SEM of response rates on the active of two levers in the chamber. a–c: Effects of antagonists selective for dopamine D1-like receptors (SCH 39166), D2-like receptors (L-741,626), and the combination of minimally active doses of each. SCH 39166 and L-741,626 shifted the cocaine self-administration dose-effect curve rightward and the combination produced an insurmountable antagonism over the range of tested doses of cocaine. d: The non-selective dopamine receptor antagonist, haloperidol, produced a dose-related rightward shift in the cocaine self-administration dose-effect curve. e: The σ1R antagonist, BD 1063, did not substantially affect cocaine self-administration. f–h: The dopamine antagonists and their combination did not substantially affect PRE-084 self-administration. i,j: Haloperidol and BD 1063, respectively, dose-dependently decreased maximal PRE-084 self-administration. Adapted from Hiranita et al. (2013).

In these same subjects PRE-084 was occasionally substituted for cocaine, with and without pretreatments with various antagonists. In contrast to their effects on cocaine self-administration, the dopamine antagonists were inactive against PRE-084 self-administration (Figure 3f, g). Similarly inactive was the combination of the D1 and D2 receptor dopamine receptor antagonists (Figure 3h). In contrast to these attempts to pharmacologically modify the self-administration of PRE-084 with selective dopamine receptor subtype antagonists or their combination, haloperidol blocked the self-administration of PRE-084 in a dose-related manner (Figure 3i). A similar blockade of PRE-084 was obtained with the σR antagonist BD 1063 (Figure 3j). The antagonism by haloperidol is not unexpected as haloperidol, in addition to being a dopamine antagonist, has σR antagonist effects (Hayashi and Su, 2007). The antagonism studies suggested that self-administration of the σR agonist, PRE-084, was independent of dopamine systems, as the dopamine antagonists effective against cocaine were ineffective against PRE-084.

To further study this potential dopamine independence the effects of PRE-084 on dopamine concentrations in the nucleus accumbens shell were examined (Hiranita et al., 2013). The nucleus accumbens shell has been shown to be an important brain structure for the effects of abused drugs (Pontieri et al., 1995; Tanda et al., 1997). Nucleus accumbens shell dopamine was assessed by means of in vivo microdialysis (Tanda et al., 1997). A dose-related increase in dopamine was produced by PRE-084 at doses of 1.0 to 10 mg/kg, which was similar regardless of whether subjects had experience with cocaine self-administration. The increase in dopamine concentration was significant at 10 mg/kg of PRE-084, though not at lower doses. This dose was 100-fold higher than the minimal dose self-administered. These dose comparisons suggest that dopamine was not involved in the reinforcing effects of the lower self-administered doses of PRE-084. Additionally, increases in dopamine concentration produced by high doses of PRE-084 were not blocked by the σR antagonists, BD 1063 or BD 1008 (Garcés-Ramírez et al., 2011). These microdialysis data are consistent with the suggestion above that reinforcing effects of PRE-084 were dopamine independent.

The generality of the induction of σR agonist self-administration was assessed in several additional studies (Hiranita et al., 2014). Rats were trained to self-administer the dopamine releaser, d-methamphetamine (0.1 mg/kg/inj), the mu-opioid receptor agonist, heroin (0.01 mg/kg/inj), and the non-competitive N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor/channel antagonist ketamine (0.32 mg/kg/inj). Each of these doses was one that produced maximal rates of self-administration in studies of the self-administration dose-effect curve. As with cocaine, self-administration of d-methamphetamine induced reinforcing effects of PRE-084 and (+)-pentazocine (0.032–1.0 mg/kg/inj, each). In contrast, self-administration of neither heroin nor ketamine induced PRE-084 or (+)-pentazocine self-administration over the range of doses that were self-administered in subjects with d-methamphetamine experience. Though the σ1R agonists did not maintain responding in subjects with histories of heroin or ketamine self-administration, substitution for those drugs was obtained with other drugs: remifentanil substituted for heroin and (+)-MK 801 substituted for ketamine. Further, the σR antagonist BD 1008 dose-dependently blocked PRE-084 self-administration but was inactive as an antagonist of d-methamphetamine, heroin, or ketamine self-administration. In contrast, PRE-084 self-administration was affected neither by the dopamine receptor antagonist, (+)-butaclamol, nor the opioid antagonist, (−)-naltrexone. As expected these antagonists were active against d-methamphetamine and heroin self-administration, respectively.

The results indicate that experience specifically with indirect-acting dopamine agonists induces reinforcing effects of previously inactive σ1R agonists. This plasticity is not simply due to some kind of response persistence, as ongoing high rates of food reinforced behavior did not function similarly, and changing the consequences of responses on two levers accordingly changed the behavior. The induction of the effect, at this point, appears related to the dopamine transporter as neither heroine nor ketamine self-administration functioned similarly to cocaine. However methamphetamine another stimulant drug that acts through the dopamine transporter, did induce σR agonist self-administration.

As detailed above, cocaine binds to σRs (Sharkey et al., 1988; Garcés-Ramírez et al., 2011), though with affinity less than that for the dopamine transporter. However, levels of cocaine achieved with systemic injection are in the μM range (Nicolaysen et al., 1988; Pettit and Pettit, 1994) and sufficient for binding to sigma receptors (Table 1). Affinity for σRs has also been reported for methamphetamine (e.g. Nguyen et al., 2005; Hiranita et al., 2014). Thus it is possible that actions at σRs contribute to the behavioral effects of cocaine involved in its abuse. It is further suggested that once induced, σ1R agonist actions of these stimulants may function as an additional pathway by which these drugs exert their reinforcing effects. It is therefore hypothetically possible that this redundant pathway to reinforcement by these two stimulant drugs may play an essential role in the intractability to medical treatment of stimulant abuse, particularly when those treatments target dopamine systems. This consideration suggests new approaches for the development of combination chemotherapies to combat stimulant dependence.

The paper by Hiranita et al. (2010) investigated the effects of a variety of σR antagonists and found them to be uniformly inactive in blocking cocaine self-administration. The study of a variety of σR antagonists was deemed important as it is recognized that drugs more often than not have multiple effects on biological systems, and as a result the effects of a single agent or lack thereof does not prove the case for an entire class of drugs. Studies conducted subsequent to the 2010 paper surprisingly found rimcazole and several related compounds to effectively block cocaine self-administration (Hiranita et al., 2011). Rimcazole is a σR antagonist that was developed by Welcome labs for the treatment of schizophrenia (Gilmore et al., 2004). Although the compound failed in clinical trials due to lack of efficacy as well as some frequency of seizures, the drug was used frequently before and for some time after the development of σR antagonists with greater affinity (de Costa et al., 1992, 1993). Hiranita et al. (2011) examined the effects of rimcazole and two close structural analogues, SH 3–24 and SH 3–28, on the self-administration of cocaine. In contrast to the lack of effect on cocaine self-administration of other σR antagonists (Hiranita et al., 2010), all three of these compounds produced dose-related decreases in cocaine self-administration. In addition these decreases in self-administration were selective as they were obtained at doses that had no effects on comparable responding maintained by food reinforcement (Hiranita et al. 2011).

The compelling question presented by this outcome is what action of the rimcazole and its analogues renders these drugs effective where other σR antagonists failed. Previous studies indicated that rimcazole binds to the dopamine transporter in addition to σRs (Izenwasser et al., 1993; Valchar et al., 1993). In fact, the affinity of rimcazole for the dopamine transporter is greater than its affinity for σRs and the rimcazole analogs studied have similar effects (Table 1). However, on the face of it, a combination of actions at the dopamine transporter and sigma antagonism seems unlikely to have the effects found with rimcazole and its analogs. As reported by Hiranita et al. (2010) selective σR antagonists have no effect on stimulant self-administration. And as mentioned above, dopamine transport inhibitors potentiate the self-administration of cocaine (Schenk et al., 2002; Barrett et al., 2004; Hiranita et al., 2009), as evidenced by dose-related leftward shifts in the cocaine self-administration dose-effect curve. It is unclear how a combination of inactivity and potentiation would together result in a dose-dependent antagonism of cocaine self-administration.

If however this combination of activities resident in rimcazole and its analogs is the key to their effectiveness, then it should be possible to synthesize the effects of rimcazole by administering a selective antagonist at σRs in combination with a selective dopamine transport inhibitor. In order to ensure that any effects obtained with this combination were not idiosyncratic to the particular compounds selected for study, combinations among three different dopamine uptake inhibitors and three different σR antagonists were assessed (Hiranita et al. 2011).

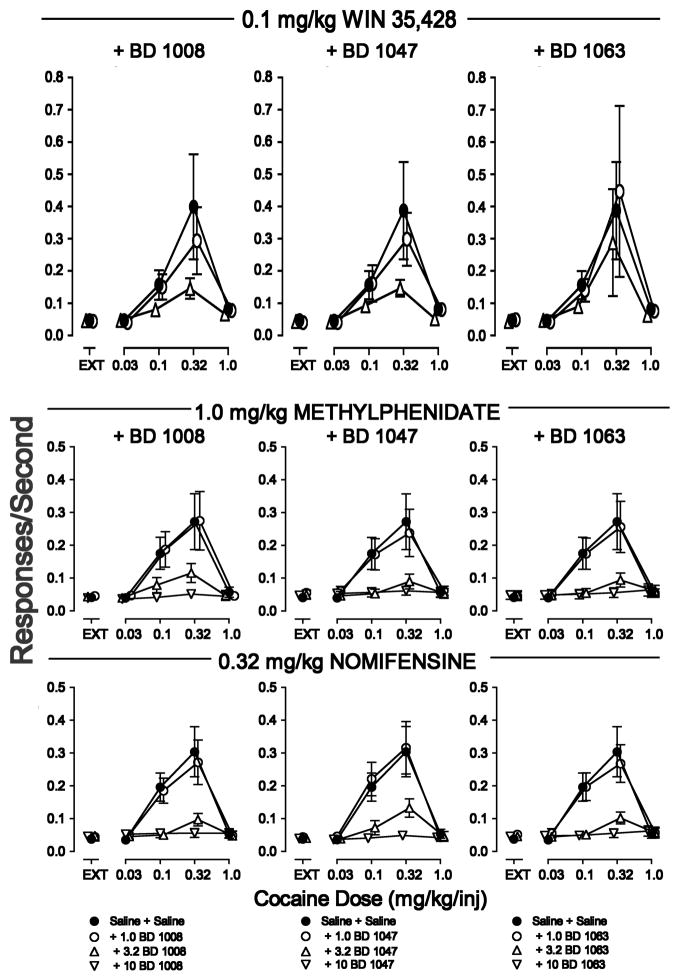

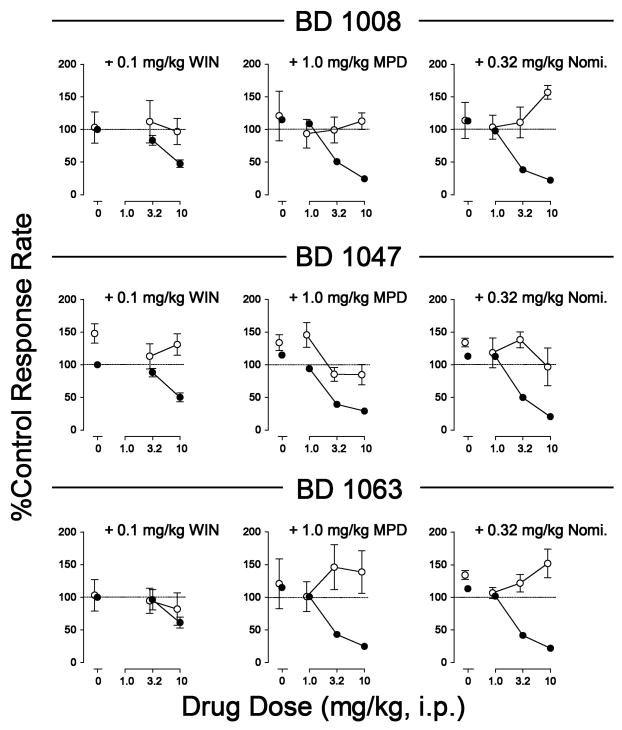

As shown previously, the cocaine dose-effect curve was an inverted U-shaped function of cocaine dose per injection and each of the dopamine uptake inhibitors produced dose-related leftward shifts in the cocaine dose-effect curve. Combinations of WIN 35,428, methylphenidate, or nomifensine with the σR antagonists BD 1008, BD 1047, and BD 1063 resulted in decreases in maximal self-administration of cocaine (Figure 4). The doses of dopamine uptake inhibitors that were effective in combination with the the σR antagonists were the highest doses that did not shift the cocaine dose-effect curve leftward. Further, with those doses of the dopamine uptake inhibitors the σR antagonists dose-dependently decreased maximal self-administration of cocaine (Hiranita et al. 2011). Similar results of a combination of σR antagonist and a dopamine uptake inhibitor were found effective in blocking methamphetamine but not heroin or ketamine self-administration (Hiranita et al., 2014).

Figure 4.

Effects of pre-session treatments with dopamine uptake inhibitors combined with σR antagonists on cocaine self-administration. Vertical axes: Responses per sec. Horizontal axes: Cocaine injection dose in mg/kg, log scale. Each point represents the mean ± SEM (N=6). WIN 35,428 (0.1 mg/kg, 5 min prior), methylphenidate (1.0 mg/kg, 5 min prior) or nomifensine (0.32 mg/kg, 5 min prior) were combined with BD 1008, BD 1047, and BD 1063 (each at doses of 1.0, 3.2 and 10 mg/kg and at 5, 15, or 5 min prior, respectively). All injectons were i.p. Each row shows effects of one of the dopamine uptake inhibitors with each of the three σR antagonists. Adapted from Hiranita et al. (2011).

At a higher dose of WIN 35,428, and likely the other dopamine uptake inhibitors, the cocaine dose-effect curve was shifted to the left, though maximal self administration was decreased with increasing doses of the σR antagonists (Hiranita et al., 2011). That essentially the same interactions were obtained with structurally different dopamine uptake inhibitors and different dopamine σR antagonists suggests that this decrease in efficacy of cocaine in the self-administration procedure was not an idiosyncratic effect of a particular drug combination but was more generally a result of a fundamental dynamic interaction among the drugs.

In addition to decreasing the maximal efficacy of cocaine in the self-administration procedure, the combinations of σR antagonists and dopamine uptake inhibitors produced selective effects similar to those seen with rimcazole and its analogs. Combinations of the drugs that decreased cocaine self-administration had little if any effect on comparable rates of responding maintained by food presentation (Figure 5). That selectivity was least apparent with combinations of WIN 35,428 and BD 1063; and that combination was least effective at the doses studied in decreasing cocaine self-administration (Figure 4). WIN 35,428 has equal affinity for σ1Rs and σ2Rs whereas the other dopamine uptake inhibitors are σ1R preferential. Because BD 1063 is preferential for σ1Rs compared to the other σR antagonists, it may be the case that σ2R affinity of WIN 35,428 is not sufficiently blocked by BD 1063 interfering with the antagonism either by a necessity for that action to be antagonized or by a direct σ2R mediated effect that interferes with the antagonism.

Figure 5.

Effects of pre-session treatments with dopamine uptake inhibitors combined with σR antagonists on maximal responding maintained by cocaine injection or food presentation. Both cocaine injection and food reinforcement were scheduled as described above for cocaine injection in the caption to figure 3. For food reinforcement the first of the five components was EXT, followed by 1, 2, 3, and 4 pellets per reinforcement occasion in the next four components, respectively. Subjects were given their daily (15 g) ration of food (Harlan Rodent Chow) 60 min before sessions, so that their response rates approached those maintained by cocaine. Vertical axes: Response rates as percentage of control response rates (sessions prior to drug tests). Horizontal axes: mg/kg of σR antagonists administered i.p. in combination with designated dopamine uptake inhibitors, log scale. Dopamine uptake inhibitors and σR antagonists were administered i.p. 5 min before sessions except BD 1047 (15 min). Data shown are from the 4th 20-min component of the session. Adapted from Hiranita et al. (2011).

Taken together the studies with rimcazole analogs and combinations of specific dopamine transport inhibitors with selective σR antagonists indicate that σR agonist actions may initiate reinforcing effects though a redundant pathway and that when both dopaminergic pathways are modulated by dopamine transport inhibitors along with antagonism of sigma receptors it is possible to effectively achieve blockade of stimulant self-administration. These outcomes suggest new avenues for the development of treatments for stimulant dependence.

Working hypotheses for mechanism underlying σR – DAT interactions

The results described above on the induction of σR agonist self-administration by stimulant drugs, together with the data on effects of combinations of σR antagonists and dopamine transport inhibitors, suggests that both short-term and long-term outcomes need be considered. In the short-term, the induction of reinforcing effects of σR agonists by stimulant self-administration likely relies upon a direct interaction of the σR and the dopamine transporter. Studies by Khoshbouei and colleagues (Lin et al., 2012) and Hong et al. (2013) have documented interactions of the dopamine transporter with σRs. These studies have shown the co-immunoprecipitation of σR and dopamine transporter in transfected cells suggesting protein-protein interactions among these entities. Interestingly this co-immunoprecipitation is enhanced in the presence of methamphetamine (Lin et al., 2012).

Recent findings with regard to the dopamine transporter may also have a bearing on the present findings. Hong and Amara (2010) have conducted studies on the interaction of the dopamine transporter with cholesterol. In those studies cholesterol increased binding of the cocaine analogue, WIN 35,428, to the dopamine transporter. Further, substituted cysteine accessibility studies suggested that cholesterol changed the conformational equilibrium of the dopamine transporter to favor a conformation open to the extracellular space (Hong and Amara, 2010). Two more recent studies (Penmatsa et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2015) have identified a cholesterol binding site on the dopamine transporter that, consistent with the Hong and Amara (2010) results, is speculated to stabilize the dopamine transporter in a conformation open to the extracellular space by hindering the movement of transmembrane segment 1a (Penmatsa et al., 2013). In this way cholesterol may play a critical role in regulating dopamine transport. A previous study (Palmer et al., 2007) has indicated that cholesterol binds to σRs. These studies suggest that the binding of σR to cholesterol may decrease cholesterol availability for binding the dopamine transporter, thereby shifting the dopamine transporter equilibrium towards cytosolic opening rather than opening to the extracellular space. Other studies have suggested that an equilibrium shift towards inward dopamine transporter conformations decreases stimulant-like actions of dopamine transport inhibitors and may be involved in the antagonism of stimulant effects (Loland et al., 2008; see review by Reith et al., 2015).

While speculative at present, this suggestion is not entirely without support. For example, exposure of HEK293 cells to σR agonists, (+)-pentazocine or PRE-084, followed by washout increases the binding of the cocaine analog WIN 35,428 to the dopamine transporter and increases dopamine uptake. The increase in binding was a result of an increase in Bmax rather than an increase in affinity, and the increase in uptake was the result of an increase in Vmax, rather than a change in Km (Hong et al., 2013).

Longer-term effects established in behavioral pharmacology studies suggest that once induced by exposure to psychomotor stimulant drugs the σR agonist reinforcing actions are independent of dopamine systems. The evidence for that conclusion comes from the studies showing that while cocaine self-administration is blocked by dopamine receptor antagonists, σR agonist self-administration is not. Conversely σR agonist self-administration is blocked by σR antagonists whereas cocaine self-administration is not. Further, microdialysis studies indicated that self-administered doses of PRE-084 did not increase extracellular dopamine concentrations in the nucleus accumbens shell (Garcés–Ramírez et al., 2011).

In considering these outcomes, the chaperone nature of the σR protein (Hayashi and Su, 2007) suggests that it may be having its effects by interacting with another protein, and the induction of reinforcing effects of σR agonists virtually ensures that the effect involves a partner membrane protein. As detailed above, the elucidation of molecular mechanisms by which σ1Rs regulate plasma membrane events is expanding and the involvement of several other proteins including, opioid receptors (Kim et al., 2010), potassium channels (Kourrich et al., 2013), as well as σ1-dopamine D1 receptor heteromers (Navarro et al., 2010), have been implicated in activity at σRs. However, these early findings should not induce tunnel vision excluding other candidates. The mechanisms underlying long-term changes are as unclear as the particular protein partner(s) with potential candidates as detailed above.

In summary, with mechanistic details still to be worked out, it is clear that actions of stimulant drugs related to their abuse induce unique changes in σR activity. Further, the changes induced potentially create redundant, and once established independent, reinforcement pathways – a reinforcement metastasis. Concomitant targeting of both the well-known reinforcing pathways initiated by blockade of the dopamine transporter, as well as σR proteins produces an effective and selective antagonism of stimulant self-administration, suggesting new avenues for combination chemotherapies to specifically combat stimulant abuse.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due Gianluigi Tanda, Paul L. Soto, Christopher R. McCurdy, and Theresa Kopajtic for the many contributions to experiments, conceptual approaches, and all-around collegiality. The staff of the Medicinal Chemistry Section of the NIDA Intramural Research Program kindly synthesized some of the compounds used in the studies described. Funding for the experiments originating in our laboratories was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse Intramural Research Program. Takato Hiranita was supported in part by the NIDA IRP and by a fellowship from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. Subjects used in the studies published from the NIDA Intramural Research Program were maintained in facilities fully accredited by the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, and those experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the institute’s Animal Care and Use Committee.

References

- Aridor M, Guzik AK, Bielli A, Fish KN. Endoplasmic reticulum export site formation and function in dendrites. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3770–3776. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4775-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydar E, Palmer CP, Klyachko VA, Jackson MB. The sigma receptor as a ligand-regulated auxiliary potassium channel subunit. Neuron. 2002;34:399–410. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00677-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett AC, Miller JR, Dohrmann JM, Caine SB. Effects of dopamine indirect agonists and selective D1-like and D2-like agonists and antagonists on cocaine self-administration and food maintained responding in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47(Suppl 1):256–273. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen WD, Tolentino PJ, Kirschner BN, Varghese P, de Costa BR, Rice KC. Sigma receptors and signal transduction: Negative modulation of signaling through phosphoinositide-linked receptor systems. NIDA Res Monogr. 1993;133:69–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania AC. Learning. 5. USA: Sloan Publishing, Cornwall on Hudson, NY; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Crofts AJ, Leborgne-Castel N, Pesca M, Vitale A, Denecke J. BiP and calreticulin form an abundant complex that is independent of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Plant Cell. 1998;10:813–824. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.5.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Costa BR, Bowen WD, Hellewell SB, Walker JM, Thurkauf A, Jacobson AE, Rice KC. Synthesis and evaluation of optically pure [3H]-(+)-pentazocine, a highly potent and selective radioligand for sigma receptors. FEBS Lett. 1989;251:53–58. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81427-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Costa BR, Radesca L, Di Paolo L, Bowen WD. Synthesis, characterization, and biologic evaluation of a novel class of N-arylethyl-N-alkyl-2-1-pyrrolidinyl.ethylamines: structural requirements and binding affinity at the σ-receptor. J Med Chem. 1992;35:38–47. doi: 10.1021/jm00079a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Costa BR, He XH, Linders JTM, Dominguez C, Gu ZQ, Williams W, Bowen WD. Synthesis and evaluation of conformationally restricted N-w2-3,4-dichlorophenyl.ethylx-N-methyl-2-1-pyrrolidinyl.ethylamines at s receptors: II Piperazines, bicyclic amines, bridged bicyclic amines and miscellaneous compounds. J Med Chem. 1993;36:2311–2320. doi: 10.1021/jm00068a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontanilla D, Johannessen M, Hajipour AR, Cozzi NV, Jackson MB, Ruoho AE. The hallucinogen N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT) is an endogenous sigma-1 receptor regulator. Science. 2009;323:934–937. doi: 10.1126/science.1166127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto M, Hayashi T, Urfer R, Mita S, Su T-P. Sigma-1 receptor chaperones regulate the secretion of brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Synapse. 2012;66:630–639. doi: 10.1002/syn.21549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcés-Ramírez L, Green JL, Hiranita T, Kopajtic TA, Mereu M, Thomas A, Mesangeau C, Narayanan S, McCurdy CR, Katz JL, Tanda G. Sigma receptor agonists: Receptor binding and effects on mesolimbic dopamine neurotransmission assessed by microdialysis in rats. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;69:208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore DL, Liu Y, Matsumoto RR. Review of the pharmacological and clinical profile of rimcazole. CNS drug reviews. 2004;10(1):1–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2004.tb00001.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Alvear GM, Werling LL. Regulation of [3H] dopamine release from rat striatal slices by sigma receptor ligands. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1994;271(1):212–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanner M, Moebius FF, Flandorfer A, Knaus HG, Striessnig J, Kempner E, Glossmann H. Purification, molecular cloning, and expression of the mammalian sigma1-binding site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8072–8077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.8072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Fujimoto M. Detergent-resistant microdomains determine the localization of sigma-1 receptors to the endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria junction. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;77:517–528. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.062539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Su TP. Intracellular dynamics of sigma-1 receptors (sigma(1) binding sites) in NG108-15 cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003a;306:726–733. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.051292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Su TP. Sigma-1 receptors (sigma(1) binding sites) form raft-like microdomains and target lipid droplets on the endoplasmic reticulum: Roles in endoplasmic reticulum lipid compartmentalization and export. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003b;306:718–725. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.051284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Su TP. The potential role of sigma-1 receptors in lipid transport and lipid raft reconstitution in the brain: Implication for drug abuse. Life Sci. 2005;77:1612–1624. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Su TP. Sigma-1 receptor chaperones at the ER-mitochondrion interface regulate Ca(2+) signaling and cell survival. Cell. 2007a;131:596–610. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Su TP. Subcellular Localization and Intracellular Dynamics of Sigma-1 Receptors. In: Matsumoto RR, Bowen WD, Su T-P, editors. Sigma Receptors: Chemistry, Cell Biology and Clinical Implications. Springer; New York, NY, USA: 2007b. pp. 151–164. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Rizzuto R, Hajnoczky G, Su TP. MAM: More than just a housekeeper. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Tsai SY, Mori T, Fujimoto M, Su TP. Targeting ligand-operated chaperone sigma-1 receptors in the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2011;15:557–577. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2011.560837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellewell SB, Bowen WD. A sigma-like binding site in rat pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells: decreased affinity for (+)-benzomorphans and lower molecular weight suggest a different sigma receptor form from that of guinea pig brain. Brain Research. 1990;527:244–253. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91143-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiranita T, Soto PL, Tanda G, Katz JL. Reinforcing effects of σ-receptor agonists in rats trained to self-administer cocaine. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2010;332:515–524. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.159236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiranita T, Soto PL, Kohut SJ, Kopajtic T, Cao J, Newman AH, Tanda G, Katz JL. Decreases in cocaine self-administration with dual inhibition of the dopamine transporter and σ receptors. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2011;339:662–677. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.185025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiranita T, Mereu M, Soto PL, Tanda G, Katz JL. Self-administration of cocaine induces dopamine-independent self-administration of sigma agonists. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013a;38:605–615. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiranita T, Soto PL, Tanda G, Kopajtic TA, Katz JL. Stimulants as specific inducers of dopamine-independent σ agonist self-administration in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013b;347:20–29. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.207522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiranita T, Kohut SJ, Soto PL, Tanda G, Kopajtic TA, Katz JL. Preclinical efficacy of N-substituted benztropine analogs as antagonists of methamphetamine self-administration in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2014 Jan;348:174–191. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.208264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman SG. Phencyclidine-like discriminative stimulus properties of opioids in the squirrel monkey. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1982;77:295–300. doi: 10.1007/BF00432758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong W, Amara SG. Membrane cholesterol modulates the outward facing conformation of the dopamine transporter and alters cocaine binding. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:32616–32626. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.150565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong WC, Amara SG, Su T-P. Exploring the association of the dopamine transporter with the sigma-1 receptor. Soc Neurosci Abstr Program No 22807 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Itzhak Y. Multiple sigma binding sites in the brain. In: Itzhak Y, editor. Sigma receptors. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1994. p. 113. [Google Scholar]

- Izenwasser S, Newman AH, Katz JL. Cocaine and several σ receptor ligands inhibit dopamine uptake in rat caudate-putamen. European journal of pharmacology. 1993;243(2):201–205. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90381-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S, Michalak M, Opas M, Eggleton P. The ins and outs of calreticulin: From the ER lumen to the extracellular space. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:122–129. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)01926-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz JL, Su T-P, Hiranita T, Hayashi T, Tanda G, Kopajtic T, Tsai S-Y. A role for sigma receptors in stimulant self administration and addiction. Pharmaceuticals. 2011;4:880–914. doi: 10.3390/ph4060880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim FJ, Kovalyshyn I, Burgman M, Neilan C, Chien CC, Pasternak GW. Sigma 1 receptor modulation of G-protein-coupled receptor signaling: Potentiation of opioid transduction independent from receptor binding. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;77:695–703. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.057083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kourrich S, Hayashi T, Chuang JY, Tsai SY, Su TP, Bonci A. Dynamic interaction between sigma-1 receptor and Kv1. 2 shapes neuronal and behavioral responses to cocaine. Cell. 2013;152(1):236–247. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard BE. Sigma receptors and sigma ligands: background to a pharmacological enigma. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2004;37(Suppl):S166–S170. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-832674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M, Goodwin SJ, Khoshbouei H. Sigma-1 receptor interacts with the dopamine transporter and methamphetamine increases the frequency of this interaction. Soc Neurosci Abstr Program No 42.19. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Yu Y, Shaikh J, Pouw B, Daniels A, Chen GD, Matsumoto RR. In Sigma Receptors. Springer US; 2007. σ Receptors and Drug Abuse; pp. 315–336. [Google Scholar]

- Loland CJ, Desai RI, Zou M-F, Cao J, Grundt P, Gerstbrein K, Sitte HH, Newman AH, Katz JL, Gether U. Relationship between conformational changes in the dopamine transporter and cocaine-like subjective effects of uptake inhibitors. Molecular Pharmacology. 2008;73:813–823. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.039800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maj J, Rogóz Z, Skuza G. Some behavioral effects of 1,3-di-o-tolylguanidine, opipramol and sertraline, the sigma site ligands. Pol J Pharmacol. 1996;48(4):379–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin WR, Eades CG, Thompson JA, Huppler RE, Gilbert PE. The effects of morphine- and nalorphine-like drugs in the nondependent and morphine-dependent chronic spinal dog. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1976;197:517–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martina M, Turcotte ME, Halman S, Bergeron R. The sigma-1 receptor modulates NMDA receptor synaptic transmission and plasticity via SK channels in rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 2007;578:143–157. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.116178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Fardon R, Maurice T, Aujla H, Bowen WD, Weiss F. Differential effects of sigma1 receptor blockade on self-administration and conditioned reinstatement motivated by cocaine vs natural reward. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:1967–1973. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto R. In: σ receptors: historical perspective and background. Matsumoto Rae R, Bowen Wayne D, Su Tsung Ping., editors. Springer Science & Business Media; 2007. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto RR, Bowen WD, Su TP. Sigma Receptors: Chemistry, Cell Biology and Clinical Implications. Springer Science + Business Media, LLC; New York, NY, USA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto RR, Li S-M, Katz JL, Fantegrossi WE, Coop A. Effects of the selective sigma receptor ligand, 1-(2-phenethyl)piperidine oxalate (AC927), on the behavioral and toxic effects of cocaine. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;118:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurice T, Su TP. The pharmacology of sigma-1 receptors. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;124:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavlyutov TA, Epstein ML, Andersen KA, Ziskind-Conhaim L, Ruoho AE. The sigma-1 receptor is enriched in postsynaptic sites of C-terminals in mouse motoneurons. An anatomical and behavioral study. Neuroscience. 2010;167:247–255. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori T, Yoshizawa K, Nomura M, Isotani K, Torigoe K, Tsukiyama Y, Narita M, Suzuki T. Sigma-1 receptor function is critical for both the discriminative stimulus and aversive effects of the kappa-opioid receptor agonist U-50488H. Addiction biology. 2012;17:717–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori T, Rahmadi M, Yoshizawa K, Itoh T, Shibasaki M, Suzuki T. Inhibitory effects of SA4503 on the rewarding effects of abused drugs. Addiction biology. 2014;19:362–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2012.00488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin-Surun MP, Collin T, Denavit-Saubie M, Baulieu EE, Monnet FP. Intracellular sigma1 receptor modulates phospholipase C and protein kinase C activities in the brainstem. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8196–8199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu Y, Otsuka T, Horton AC, Scott DB, Ehlers MD. Activity-dependent mRNA splicing controls ER export and synaptic delivery of NMDA receptors. Neuron. 2003;40:581–594. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00676-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen EC, McCracken KA, Liu Y, Pouw B, Matsumoto RR. Involvement of sigma (σ) receptors in the acute actions of methamphetamine: receptor binding and behavioral studies. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49(5):638–645. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro G, Moreno E, Aymerich M, Marcellino D, McCormick PJ, Mallol J, Cortes A, Casado V, Canela EI, Ortiz J, et al. Direct involvement of sigma-1 receptors in the dopamine D1 receptor-mediated effects of cocaine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:18676–18681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008911107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro G, Moreno E, Bonaventura J, Brugarolas M, Ferré D, Aguinaga D, Mallol J, Cortés A, Casadó V, Lluís C, Ferre S, Franco R, Canela E, McCormick PJ. Cocaine inhibits dopamine D2 receptor signaling via sigma-1-D2 receptor heteromers. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e61245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaysen LC, Pan H-T, Justice JB., Jr Extracellular cocaine and dopamine concentrations are linearly related in rat striatum. Brain Research. 1988;456:317–323. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90234-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura T, Ishima T, Iyo M, Hashimoto K. Potentiation of nerve growth factor-induced neurite outgrowth by fluvoxamine: Role of sigma-1 receptors, IP3 receptors and cellular signaling pathways. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer CP, Mahen R, Schnell E, Djamgoz MB, Aydar E. Sigma-1 receptors bind cholesterol and remodel lipid rafts in breast cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11166–11175. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penmatsa A, Wang KH, Gouaux E. X-ray structure of dopamine transporter elucidates antidepressant mechanism. Nature. 2013;503(7474):85–90. doi: 10.1038/nature12533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit bHO, Pettit AJ. Disposition of cocaine in blood and brain after a single pretreatment. Brain Research. 1994;651:261–268. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90705-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontieri FE, Tanda G, Di Chiara G. Intravenous cocaine, morphine, and amphetamine preferentially increase extracellular dopamine in the “shell” as compared with the “core” of the rat nucleus accumbens. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1995;92(26):12304–12308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reith MEA, Blough BE, Hong WC, Jones KT, Schmitt KC, Baumann MH, Partilla JS, Rothman RB, Katz JL. Behavioral, biological, and chemical perspectives on atypical agents targeting the dopamine transporter. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2015;147:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzuto R, Pinton P, Brini M, Chiesa A, Filippin L, Pozzan T. Mitochondria as biosensors of calcium microdomains. Cell Calcium. 1999;26:193–199. doi: 10.1054/ceca.1999.0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romieu P, Martin-Fardon R, Maurice T. Involvement of the σ1 receptor in thecocaine-induced conditioned place preference. Neuroreport. 2000;11:2885–2888. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200009110-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romieu P, Phan VL, Martin-Fardon R, Maurice T. Involvement of the sigma1 receptor in cocaine-induced conditioned place preference: possible dependence on dopamine uptake blockade. 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romieu P, Martin-Fardon R, Bowen WD, Maurice T. ζ1 Receptor-Related Neuroactive Steroids Modulate Cocaine-Induced Reward. The Journal of neuroscience. 2003;23:3572–3576. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-09-03572.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruoho A. Will the true sigma2 receptor please stand up? Soc Neurosci Abstr 631.08 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Sage AS, Oelrichs CE, Davis DC, Fan KH, Nahas RI, Lever SZ, Miller DK. Effects of N-phenylpropyl-N′-substituted piperazine sigma receptor ligands on cocaine-induced hyperactivity in mice. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2013;110:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk S. Effects of GBR 12909; WIN 35,428 and indatraline on cocaine self-administration and cocaine seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;160:263–270. doi: 10.1007/s00213-001-0972-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder M, Kaufman RJ. The mammalian unfolded protein response. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:739–789. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey J, Glen KA, Wolfe S, Kuhar MJ. Cocaine binding at sigma receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 1988;149:171–174. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P, Ignatchenko V, Grace K, Ursprung C, Kislinger T, Gramolini AO. Endoplasmic reticulum protein targeting of phospholamban: A common role for an N-terminal di-arginine motif in ER retention? PLoS One. 2010;5:e11496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skuza G, Rogóz Z. Antidepressant-like effect of PRE-084, a selective sigma1 receptor agonist, in Albino Swiss and C57BL/6J mice. Pharmacol Rep. 2009;61(6):1179–83. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(09)70181-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skuza G, Wedzony K. Behavioral pharmacology of sigma-ligands. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2004;37(Suppl):S183–S188. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-832676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprong H, van der Sluijs P, van Meer G. How proteins move lipids and lipids move proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:504–513. doi: 10.1038/35080071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun FC, Wei S, Li CW, Chang YS, Chao CC, Lai YK. Localization of GRP78 to mitochondria under the unfolded protein response. Biochem J. 2006;396:31–39. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]