Abstract

Objectives

We examined effects of long-term medical marijuana legalization on cigarette co-use in a sample of adults.

Methods

We conducted secondary analysis using data from the 2014 US Tobacco Attitudes and Beliefs Survey, which consisted of cigarette smokers, aged ≥ 45 years (N = 506). Participants were categorized by their state residence, where medical marijuana was (1) illegal, (2) legalized < 10 years, and (3) legalized ≥ 10 years. The Web-based survey assessed participants’ marijuana use, beliefs and attitudes on marijuana, and nicotine dependence using Fagerstrom Tolerance for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) and Hooked on Nicotine Checklist (HONC) scores.

Results

In cigarette smokers aged ≥ 45 years, long-term legalization of medical marijuana was associated with stable positive increases in marijuana use prevalence (ever in a lifetime) (p = .005) and frequency (number of days in past 30 days) (unadjusted p = .005; adjusted p = .08). Those who reported marijuana co-use had greater FTND and HONC scores after adjusting for covariates (p = .05).

Conclusions

These preliminary findings warrant further examination of the potential impact of long-term legalization of medical marijuana on greater cigarette and marijuana co-use in adults and higher nicotine dependence among co-users at the population level.

Keywords: tobacco control, marijuana policy, public health policy, marijuana use, nicotine dependence, cigarette, marijuana co-use

As of January 2015, 23 US states and Washington DC have legalized the use of medical marijuana and at least 10 states are considering legalization of recreational marijuana through either their state legislatures or ballot measures. Increasing statewide legalization of medical marijuana has resulted in changes to the landscape of marijuana use, by increasing both exposure and access, including the availability of various modalities, both combustible and non-combustible, that could affect patterns of use over time. In the US, lifetime prevalence of marijuana use among adults was approximately 43% in 2001-20031 and past 12-month prevalence was approximately 4% in 2001-2002.2 Previous studies have shown a consistently strong association between marijuana and tobacco co-use, including tobacco use with blunts (marijuana rolled in tobacco leaves)3 and mulling or as spliffs (adding tobacco to marijuana joints).4 There is also growing evidence to support a “reverse gateway” effect of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) in marijuana on cigarette initiation and progression toward nicotine dependence.5-8 However, most studies have focused primarily on youth and adolescent populations and little is known about marijuana and tobacco co-use in adults. As more states legalize the use of medical and recreational marijuana, over time, these policies likely will impact patterns of both marijuana and tobacco use across age groups.

According to data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), in the past decade, marijuana use prevalence in the past 30 days increased approximately 20%.3 At present, 11 states have legalized medical marijuana for 10 or more years with California being the first to pass legislation in 1996 with Proposition 215. These states represent those that have had the most time to enact the policy and for their population to respond to greater exposure and access to legal marijuana. For example, 4 of these states with 10 or more years of medical marijuana legalization (or “long-term” legalization), California (18 years), Oregon (16 years), Washington (16 years), and Colorado (14 years), accounted for 89% of $2.7 billion in legal marijuana sales in 2014.9 Additionally, as of 2015, possession and sale of recreational marijuana was legal in Colorado, Washington, Oregon, and the District of Columbia. The legal marijuana industry is rapidly growing and states that were early adopters of the policy are taking the lead in sales. An established infrastructure along with high sales figures is a good indication of the demand for marijuana in and around these states. An analysis of epidemiologic data has shown that adults who resided in states with (vs without) medical marijuana legalization were nearly 2-times more likely to report marijuana use in the past year and marijuana abuse/dependence.10

A report on marijuana legalization from Vermont, where medical marijuana was legalized in 2004 (and recreational use is being considered) found that those who self-reported marijuana use in the past 30 days were 3 times more likely to report cigarette use.3 Increasingly, there is strong empirical evidence to strengthen the notion that marijuana use during early adolescence can lead to cigarette initiation and nicotine dependence.7,8,11,12 Two longitudinal cohort studies have shown that adolescents who self-reported marijuana use were significantly more likely to initiate cigarette use and become nicotine dependent,7,11 with up to an 8-fold increase in the odds of initiation.7 Similar effects were reported in a study among women aged 18-29 years in which marijuana use was linked to initiation of cigarette smoking, regular cigarette smoking, and progression to nicotine dependence.12 These data suggest that an increase in marijuana use prevalence could have a likely impact on tobacco initiation and nicotine dependence.

Given the strong association between marijuana and cigarette co-use, the proliferation of legalized medical marijuana could have the unintended effect of increasing co-use across populations. Implications for marijuana and cigarette co-use include the potential for greater adverse health effects by compounding risks associated with using either tobacco or marijuana alone. The synergistic effects of regularly using combusted marijuana and tobacco are understudied. But, the adverse health effects of cigarette use are well-established13,14 and previous studies have reported a number of health risks associated with both acute and chronic marijuana use.15,16 Acute marijuana use has been linked to increased risk of car crashes while intoxicated,17 and chronic marijuana use (daily or near-daily use) has been linked to dependence,18,19 impaired cognitive and brain function,20,21,21-24 psychotic symptoms and disorders,25-28 anxiety and depressive disorders,29 respiratory risks,30,31 cardiovascular effects,32-35 and testicular cancer.36-38 Therefore, studies are needed to examine if statewide policies on medical marijuana have an influence on patterns of cigarette and/or marijuana use and co-use to assess need and strategies to reduce risks associated with these substances.

As more states legalize medical marijuana, and some are considering legalization of recreational marijuana, the landscape of marijuana is rapidly changing toward an expanding medical marijuana market. Researchers and policymakers can gain insight from states with the longest history of medical marijuana legalization as past experiences have shown that statewide policies can effectively change social norms and health behaviors.44 The primary aim of this study was to examine whether adult cigarette smokers who resided in states with long-term legalization of medical marijuana had a (1) higher prevalence and frequency of marijuana use; (2) greater nicotine dependence; or (3) social acceptability of marijuana.

METHODS

Study Design and Sample

Secondary analyses were conducted using data from the 2014 US Tobacco Attitudes and Behavior Survey, which consisted mostly of current cigarette smokers aged 45 years and over. This survey purposefully focused on the upper smoking age categories because these groups are often understudied in tobacco control research. This Web-based survey was administered by Qualtrics, a commercial marketing research company that aggregates online panels to create nationally representative samples from which to randomly select survey participants. A total of 11,676 individuals were invited to take the survey; overall, 2186 clicked on the survey to yield a response rate of 19%, an above average response rate among online surveys conducted by Qualtrics. Participants were sent one email notification soliciting their participation and offered $10 for completing the survey. Questionnaire items assessed attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors on traditional (eg, cigarettes), new-and-emerging tobacco products (eg, e-cigarettes), and marijuana.

Questionnaire Items

Statewide legalization of medical marijuana

Participants were asked to indicate their state of residence and these states were categorized into one of 3 groups: states in which medical marijuana was (1) illegal, (2) legalized < 10 years, or (3) legalized ≥ 10 years (ie, long-term legalization). As of December 2013, marijuana for medicinal use was illegal in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming (N = 27). Medical marijuana has been legalized for < 10 years in Arizona, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, and Rhode Island (N = 12) and legalized for ≥ 10 years in Alaska, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Maine, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, South Carolina, Vermont, and Washington (N = 11).

Marijuana use prevalence and frequency

Marijuana use prevalence (including blunts) was assessed for ever use during the lifetime and current use in the past 30 days. Participants were asked: “During your entire life, about how many times did you EVER use marijuana [blunts], even a little?” and dichotomized to either “never” or “ever” having used marijuana. For measures of current use, participants were asked: “In the last 30 days, on about how many days did you use marijuana?” In addition, among those who reported current use, we assessed the frequency of marijuana use in the past 30 days.

Nicotine dependence

The survey assessed nicotine dependence using both the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) and the Hooked on Nicotine Checklist (HONC). Detailed descriptions of each scale, items, and scoring are published elsewhere.45,46 In brief, FTND is a 6-item scale that has been shown to be reliable47 with mixed validity.48 In the present study, total FTND scores were calculated and also categorized accordingly: low (1-2), low-to-moderate (3-4), moderate (5-7), and high (8+). HONC is a 10-item scale which has shown to be a reliable and valid measure of nicotine dependence, specifically, “diminished autonomy over tobacco,” in both adolescent and adult populations.48 A “yes” response to any one item, a score above zero, indicates dependence with higher scores reflecting greater dependence.45,48 Total HONC scores were calculated and also categorized around the sample mean (< 5 or ≥ 5) for comparison across state legalization categories. A study by Wellman et al48 compared the HONC and FTND and found that the HONC had higher internal consistency along with other advantages including measure of a clearly defined construct with each item having face validity to asses diminished autonomy.49 In the present study, FTND and HONC categories were used to assess baseline nicotine dependence levels and total scores for comparison of nicotine dependence between participants who reported current marijuana use versus no marijuana use.

General attitudes and beliefs about marijuana including social norms

The survey assessed participants’ general attitudes and beliefs about marijuana, including social norms, and responses were compared across state legalization categories. Items that assessed general attitudes and beliefs asked participants to rate on a 4-point Likert-type scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” whether medical marijuana should be legal, recreational marijuana should be legal, marijuana is affordable or accessible (easy to get), it's ok to smoke medical marijuana in outdoor (eg, parks) or indoor (eg, malls, theaters) public spaces, and it's ok to smoke marijuana in the house. Items that accessed social norms asked on a 4-point scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” whether their friends or family think it is ok (socially acceptable) if the participant used marijuana. Participants were also asked to respond either “yes” or “no” to whether “any of your friends,” or “anyone you lived with,” or “your mate, person you live with, spouse, or significant other” has/have ever used marijuana.

Statistical Analysis

Chi-square tests were conducted to compare sample characteristics across state medical marijuana legalization categories (ie, illegal, legalized < 10 years, legalized ≥ 10 years) to identify any significant differences in age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, community (ie, urban, suburban, rural), FTND score categories, HONC score categories around the sample mean (< 5 or ≥ 5), and marijuana use prevalence and frequency. We calculated prevalence of one or more days of use in a lifetime and in the past 30 days, and frequency, or mean (SD) number of days of marijuana use in the past 30 days, and compared them across state legalization categories; these models adjusted for potential covariates including age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, FTND score, and community (ANCOVA). We compared total mean (SD) HONC and FTND scores for marijuana users versus non-marijuana users in the past 30 days; adjusted models accounted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, and community (ANCOVA). Logistic regression models calculated odds ratios of responding “strongly/agree” or “yes” to items that assessed attitudes and beliefs on marijuana including social norms given the participant's residence in a state that had legalized medical marijuana for ≥ 10 years (vs states where medical marijuana was illegal). Adjusted models accounted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, FTND score, community, and ever use of marijuana or blunts. In this exploratory analysis, we used a standard p-value of < .05 and a less rigorous threshold of < .10 to set the statistical significance for each test. The latter was used given the known limitations of the available dataset and dearth of other datasets for this analysis to gain insight on how to approach future studies. All analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

A total of 549 participants completed the online survey; 92% indicated that they were 45 years or older and “regularly smoke cigarettes.” Final sample characteristics included a mean (SD) age of 57.0 (7.3) years; 57% were female; 83% were non-Hispanic Whites, followed by 9% Blacks or African Americans; 62% had an education level of at least a high school degree or GED, followed by 34% with a college degree or above; and 48% resided in a suburban community. Overall, this sample of adult cigarette smokers aged ≥ 45 years had a mean (SD) FTND score of 4.4 (2.1) (low-to-moderate dependence) and a total HONC score of 5.3 (2.2). Table 1 shows most participants resided in states where medical marijuana was illegal (N = 299, 59%), followed by states where legalization occurred < 10 years ago (N = 112, 22%), then ≥ 10 years ago (N = 95, 19%). In this sample, states where medical marijuana was illegal had the highest percentage of non-Hispanic Whites (86%), followed by states that legalized < 10 years ago (82%), then ≥ 10 years ago (76%) (p = .04).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Cigarette Smokers Aged 45 Years and over from the Tobacco Attitudes and Behaviors Survey by State Residence – Years of Statewide Legalization of Medical Marijuana (N = 506), N (%)

| Statewide Medical Marijuana Policy |

p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illegal | Legal < 10 Years | Legal ≥ 10 Years | ||

| (N = 299) | (N = 112) | (N = 95) | ||

| Age, years | ||||

| 45-59 years | 198 (66%) | 73 (65%) | 66 (69%) | .79 |

| ≥ 60 years | 101 (34%) | 39 (35%) | 29 (31%) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 129 (43%) | 49 (44%) | 41 (43%) | .99 |

| Female | 170 (57%) | 63 (56%) | 54 (57%) | |

| Race/ Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 258 (86%) | 92 (82%) | 72 (76%) | .04* |

| Black or African-American | 26 (9%) | 11 (9%) | 9 (9%) | |

| Other | 15 (5%) | 9 (9%) | 14 (14%) | |

| Education | ||||

| < High school | 15 (5%) | 6 (5%) | 2 (2%) | .65 |

| High school or GED | 182 (61%) | 67 (60%) | 64 (67%) | |

| ≥ College | 102 (34%) | 39 (35%) | 29 (31%) | |

| Community | ||||

| Urban | 73 (24%) | 32 (29%) | 35 (37%) | .06† |

| Suburban | 143 (48%) | 58 (52%) | 44 (46%) | |

| Rural | 83 (28%) | 22 (20%) | 16 (17%) | |

| Fagerstrom Score | ||||

| Low (1-2) | 58 (19%) | 28 (25%) | 24 (25%) | .26 |

| Low to moderate (3-4) | 88 (29%) | 42 (38%) | 29 (31%) | |

| Moderate (5-7) | 126 (42%) | 32 (29%) | 34 (36%) | |

| High (8+) | 27 (9%) | 10 (9%) | 8 (8%) | |

| Hooked on Nicotine Checklist | ||||

| < 5 (below mean) | 64 (21%) | 30 (27%) | 15 (16%) | .16 |

| ≥ 5 (equal or above mean) | 235 (79%) | 82 (73%) | 80 (84%) | |

| Marijuana Use | ||||

| Ever (≥ 1 lifetime) | 204 (68%) | 82 (73%) | 81 (85%) | <.01* |

| Past 30 days (≥ 1 day) | 43 (14%) | 9 (8%) | 17 (18%) | .10 |

χ2, p < 05

p < .10

Marijuana Use

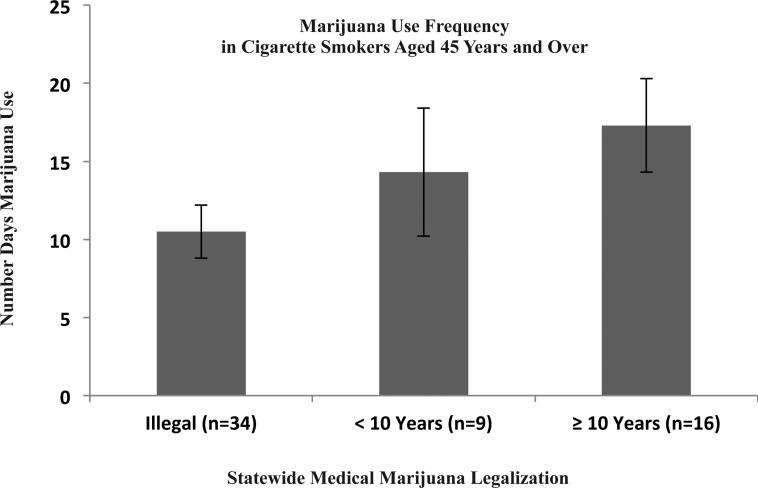

Overall, 73% of adult cigarette smokers aged ≥ 45 years responded “yes” to ever using marijuana in their lifetime. As expected, Table 1 indicates states that legalized medical marijuana for more years were associated with greater percentages of participants who responded “yes” to ever using marijuana: 85% in states with ≥ 10 years, 73% in states with < 10 years of legalization, and 68% in states where medical marijuana was illegal (p = .005). In cigarette smokers who reported “ever” using marijuana (N = 367), 59 participants, or 16%, indicated past 30-day use with a mean (SD) of 12.6 (11.0) days (data not shown). Figure 1 shows that 11% of the sample were cigarette and marijuana co-users, and their marijuana use frequency, or mean (SD) number of days, in the past 30 days was positively associated with years of statewide legalization of medical marijuana: 10.5 (10.0) days in states where medical marijuana was illegal, 17.3 (11.8) days in states that legalized ≥ 10 years ago, and 14.3 (12.3) days in states that legalized < 10 years ago (p = .04), although this significance was attenuated after adjusting for covariates (p = .08).

Figure 1.

Mean Number of Days of Marijuana Use in Cigarette Smokers Aged ≥ 45 Years Reporting Marijuana Use in the Past 30 Days, Grouped by State Residence – Number of Years of Statewide Legalization of Medical Marijuana

Nicotine Dependence

In this sample of adult cigarette smokers, the overall mean (SD) FTND score was 4.4 (2.1), which was in the low-moderate range for nicotine dependence, and the overall HONC score was 5.3 (2.2). Table 2 provides a comparison of both unadjusted and adjusted mean (SD) FTND and HONC scores among current marijuana users versus non-marijuana users in the overall sample of adult cigarette smokers and across state legalization categories. Cigarette smokers who indicated using marijuana in the past 30 days (vs no marijuana use) had higher FTND scores (5.1 vs 4.3; p = .01) and HONC scores (5.9 vs 5.2; p = .05). This difference in nicotine dependence, in which cigarette and marijuana co-users had higher levels of nicotine dependence, was stable across state legalization categories.

Table 2.

Comparison of Mean (SD) Nicotine Dependence Scores among Cigarette Smokers Aged 45 Years and over Reporting Marijuana Use vs Non-use in the Past 30 Days

| Past 30-Day Marijuana Use |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | p-value | |||

| N | (N = 69) | (N = 437) | Unadjusted | Adjusted a | |

| FTNDb Score | |||||

| Overall | 506 | 5.1 (2.4) | 4.3 (2.1) | <.01* | .01* |

| State Legalization | |||||

| Illegal | 299 | 5.2 (2.5) | 4.4 (2.1) | .04* | .12 |

| < 10 Years | 112 | 5.0 (2.5) | 4.0 (1.9) | .15 | .40 |

| ≥ 10 Years | 95 | 5.1 (2.1) | 4.2 (2.1) | .14 | .09† |

| HONCb Score | |||||

| Overall | 506 | 5.9 (1.5) | 5.2 (2.3) | .01* | .05† |

| State Legalization | |||||

| Illegal | 299 | 5.7 (1.5) | 5.3 (2.4) | .23 | .49 |

| < 10 Years | 112 | 6.4 (1.1) | 4.9 (2.3) | .04* | .03* |

| ≥ 10 Years | 95 | 6.1 (1.7) | 5.5 (1.9) | .20 | .05† |

ANOVA/ANCOVA, p < .05

p < .10

Note.

Adjusted models accounted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, and community (ie, urban, suburban, rural)

Abbreviations: FTND=Fagerstrom Tolerance for Nicotine Dependence; HONC=Hooked on Nicotine Checklist

General Attitudes and Beliefs about Marijuana

Table 3 presents odds ratios of agreement with items that assessed general attitudes and beliefs on marijuana given participants’ residence in states with long-term legalization of medical marijuana (or ≥ 10 years, and states where medical marijuana was illegal as the reference category). In this sample, there were no significant differences in participants’ views on whether medical or recreational marijuana should be legal and whether marijuana is affordable depending on state legalization categories. As expected, participants were more likely to “strongly agree” or “agree” that marijuana was accessible (“easy to get”) in states with long-term legalization; however, this association was not statistically significant. Participants were no more or less likely to “strongly agree” or “agree” to whether it is ok to smoke marijuana in the house, smoke medical marijuana in outdoor spaces, or smoke medical marijuana in indoor spaces given their state's legalization categories.

Table 3.

Odds Ratio of Responding “Strongly Agree / Agree” or “Yes” to Items that Assessed General Attitudes and Beliefs Including Social Norms on Marijuana in Participants Who Resided in States with Long-term Legalization of Medical Marijuana (≥ 10 years)a

| Unadjusted |

Adjustedb |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Responses | % | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| General Attitudes & Beliefs | |||||||||

| Medical marijuana should be legal | 506 | SA or A | 88% | 1.15 | 0.56-2.34 | .71 | 1.05 | 0.49-2.24 | .90 |

| Marijuana for recreational use should be legal | 506 | SA or A | 56% | 1.30 | 0.82-2.08 | .27 | 1.04 | 0.62-1.72 | .89 |

| Marijuana is affordable | 506 | SA or A | 47% | 1.16 | 0.73-1.84 | .54 | 1.12 | 0.69-1.80 | .65 |

| It's easy to get marijuana | 506 | SA or A | 75% | 1.54 | 0.89-2.68 | .13 | 1.44 | 0.81-2.56 | .22 |

| It's ok to smoke marijuana in the house | 506 | SA or A | 41% | 1.38 | 0.87-2.20 | .17 | 1.21 | 0.74-1.99 | .45 |

| It's ok to smoke medical marijuana in outdoor public spaces | 506 | SA or A | 43% | 1.04 | 0.65-1.66 | .86 | 0.99 | 0.61-1.60 | .95 |

| It's ok to smoke medical marijuana in indoor public spaces | 506 | SA or A | 14% | 0.99 | 0.50-1.99 | .98 | 1.12 | 0.54-2.29 | .76 |

| Social Norms | |||||||||

| Friends think it's ok (socially acceptable) for me to use marijuana | 424 | SA or A | 38% | 1.62 | 0.97-2.70 | .06† | 1.31 | 0.76-2.26 | .33 |

| Family thinks it's ok (socially acceptable) for me to use marijuana | 506 | SA or A | 21% | 1.55 | 0.90-2.66 | .11 | 1.46 | 0.83-2.57 | .19 |

| As far as you know, has/have... | |||||||||

| any of your friends ever used marijuana? | 459 | Yes | 78% | 1.74 | 0.89-3.42 | .11 | 0.91 | 0.42-1.98 | .82 |

| anyone you lived with ever used marijuana? | 460 | Yes | 54% | 1.65 | 1.00-2.73 | .05† | 1.11 | 0.62-1.98 | .74 |

| your mate, person you live with, spouse, significant other ever used marijuana | 385 | Yes | 39% | 1.26 | 0.73-2.17 | .41 | 1.08 | 0.58-2.03 | .80 |

*Logistic regression, p < .05

p < .10

Note.

Reference category = states where medical marijuana was illegal

Adjusted OR's accounted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, FTND score, community (ie, urban, suburban, rural), and ever use of marijuana or blunts

Social Norms about Marijuana

Participants were more likely to respond “yes” to knowing someone who has ever used marijuana in states with long-term legalization of medical marijuana. This association was nearly statistically significant in those who have lived with someone who has ever used marijuana (OR=1.65; CI: 1.00-2.73; p = .05), and not after adjusting for covariates. Additionally, participants were more likely to respond “strongly agree” or “agree” that their friends or family members think it is ok (socially acceptable) for the participant to use marijuana in those who lived in long-term legalization states. This association was nearly statistically significant among those who indicated their friends think it is ok for the participant to use marijuana (OR=1.62; CI: 0.97-2.70; p = .06); although, again, the effect was lost after adjusting for covariates.

DISCUSSION

In a sample of adult cigarette smokers aged ≥ 45 years, long-term statewide legalization of medical marijuana (≥ 10 years) was associated with greater marijuana prevalence use and frequency. These preliminary findings suggest that long-term legalization of medical marijuana could play a role in cigarette and marijuana co-use in adults. Additionally, among these adult cigarette smokers, those who used marijuana had greater dependence on nicotine. Although it is possible that legalization of medical marijuana helped to shape social norms around marijuana,10 in the present study, attitudes and beliefs including social norms concerning marijuana were not significantly different across state legalization categories. These early findings, taken together, warrant a closer examination of the relationship between co-use of cigarettes and marijuana at the population level amidst a continuing trend towards legalization of medical marijuana.

Long-term Legalization of Medical Marijuana and Marijuana Use

As expected, marijuana use prevalence and frequency was highest among adult cigarette smokers who resided in states with long-term legalization of medical marijuana. These findings were consistent with data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), which indicated adults who lived in states that legalized medical marijuana were more likely to report marijuana use (OR: 1.92; 95% CI: 1.49-2.47) and marijuana abuse/dependence (OR: 1.81; 95% CI: 1.22-2.67) in the past year.10 The present study is unique because: (1) the sample specifically focuses on adult cigarette smokers aged ≥ 45 years who represent the upper age categories of smokers who are underrepresented in tobacco control research; and (2) it adds that increased marijuana use prevalence and frequency could be a function of time, specifically, number of years since legalization. This analysis on “long-term” legalization cannot be repeated with most national datasets that limit public access to certain variables including state of residence in their effort to protect the identity of survey participants. Larger datasets are needed to repeat this analysis and improve these results. The US has yet to reach full saturation in which all states have legalized both the use of medical and recreational marijuana, but is headed in this direction. Thus, if these findings are valid, we can expect further increases in cigarette and marijuana co-use among adults in the near future.

Co-use of Cigarettes and Marijuana and Nicotine Dependence

These preliminary findings suggest that long-term legalization could be linked to increased cigarette and marijuana co-use in adults and these co-users were associated with greater cigarette nicotine dependence. The findings are consistent with epidemiologic studies on cigarette and marijuana co-use in adolescents.7,11,12 Although the underlying mechanism is unclear, animal models have shown that rats with prior exposure to THC, compared to those with no prior exposure, were 3-times more likely to self-administer nicotine.8 Researchers have proposed that pre-exposure to THC during adolescence brain development had lasting alterations in both the cannabinoid and opioid systems to later interact with the nicotinic-acetylcholine (or nicotine reward) system to explain the higher self-administration of nicotine.50 Therefore, it is possible that cigarette and marijuana co-use may be involved in a gateway effect.5-8 These studies on adolescents are relevant in our sample of adults because those who were aged 45 years and older represent the Baby Boomer Generation and were likely an adolescent during the 1960s and 1970s where the counterculture of the era promoted widespread use of marijuana.51 Therefore, it is likely initiation of marijuana occurred during adolescence and therefore could have played a role in cigarette and marijuana co-use later as adults.

Other possible explanations for this positive association between marijuana use and nicotine dependence include individual behavioral factors (eg, mixing tobacco with marijuana)6,7 and potential confounders such as mental health disorders52,53 and other risky behaviors.54 However, because causality cannot be established,8 these relationships are limited in their interpretation. In summary, these findings support the existing evidence for a positive relationship between marijuana and nicotine dependence and adds to the literature that this relationship was observed in a sample of adults aged 45 years and over. An implication of this finding is that increases in marijuana use could moderate the effects of nicotine dependence and therefore create greater challenges in cessation among adult cigarette smokers. Studies are needed to understand the role of marijuana legalization on patterns of co-use, including initiation and re-initiation of cigarettes and/or marijuana, nicotine and THC dependence, health risks of dual-use, and potential challenges in cessation treatments.

Limitations

Limitations of this study included a small sample of current marijuana users that might explain some of the nearly and non-significant findings. Generalizability of these results is limited to a small sample of adult cigarette smokers aged ≥ 45 years, and therefore, not representative of the US population. A possible reason for a relatively low response rate in the Web-based survey might be attributed to a single email blast (vs multiple email blasts) to solicit survey participation. Future surveys may need to employ effective strategies including the use of external and/or intrinsic motivation to improve response rates. Yet, we conducted this study because these data were available for this particular analysis which allowed categorization of participants by their state residence (data unavailable anywhere else). Study measures did not characterize the modality of marijuana use, specifically, combustible (eg, hand pipes, water pipes, rolling papers, hookahs, homemade devices, vaporizers) versus non-combustible (eg, tinctures or liquid cannabis extracts, ingestible oils, edibles, topicals). As marijuana use increases, epidemiologic data are needed to assess the various modalities of use (particularly combustible vs non-combustible), frequency of use (dose over time), and health outcomes including potential benefits. On the federal level, marijuana is a Schedule 1 controlled substance, which might make participants more reluctant to report use, and thereby underestimate the true prevalence. Studies have shown that compared to members of other age groups, older adults are more likely to underreport the use of illicit drugs including marijuana.39-41 Single items that assessed general attitudes and beliefs, including social norms, were not tested previously, and therefore, have limited validity. A strength of this study was the use of 2 measures of nicotine dependence including the HONC which is a valid and reliable measure of nicotine dependence among adults.48

Conclusions

It may be possible that the effects of statewide legalization of medical marijuana on patterns of marijuana use and co-use with cigarettes occur over time. Data are needed to monitor these rapidly evolving policies to conduct longitudinal epidemiologic analysis to assess changes in use at the population level across age groups. In the meantime, we can gather insight on available data particularly from states that were early adopters of legalization. These preliminary data suggest that patterns of use could be a function of time (length of time after legalization) and that co-use might be associated with greater nicotine dependence. Further study is needed to corroborate these findings and to determine whether legalization of medical marijuana might have implications for tobacco control and treatment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute and Food and Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products (1P50CA180890 and CA-113710). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Food and Drug Administration.

Footnotes

Human Subjects Statement

The University of California, San Francisco Human Research Protection Program approved this study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

None declared.

Contributor Information

Julie B. Wang, Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education, Cardiovascular Research Institute, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA..

Janine K. Cataldo, School of Nursing, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA..

References

- 1.Degenhardt L, Chiu WT, Sampson N, et al. Epidemio-logical patterns of extra-medical drug use in the United States: evidence from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, 2001-2003. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90(2-3):210–223. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Compton WM, Grant BF, Colliver JD, et al. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States: 1991-1992 and 2001-2002. JAMA. 2004;291(17):2114–2121. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caulkins JP, Kilmer B, Kleiman MAR, et al. Considering Marijuana Legalization: Insights for Vermont and Other Jurisdictions. Vol. 2015. Rand Corporation; Santa Monica, CA: [December 27, 2015]. pp. 1–218. Available at: http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR800/RR864/RAND_RR864.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bélanger RE, Akre C, Kuntsche E, et al. Adding tobacco to cannabis--its frequency and likely implications. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(8):746–750. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Humfleet GL, Haas AL. Is marijuana use becoming a “gateway” to nicotine dependence? Addiction. 2004;99(1):5–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tullis LM, Dupont R, Frost-Pineda K, Gold MS. Marijuana and tobacco: a major connection? J Addict Dis. 2003;22(3):51–62. doi: 10.1300/J069v22n03_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patton GC, Coffey C, Carlin JB, et al. Reverse gateways? Frequent cannabis use as a predictor of tobacco initiation and nicotine dependence. Addiction. 2005;100(10):1518–1525. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Panlilio LV, Zanettini C, Barnes C, et al. Prior exposure to THC increases the addictive effects of nicotine in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(7):1198–1208. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ArcView Market Research [December 21, 2015];The state of legal marijuana markets. 2015 Available at: http://www.arcviewmarketresearch.com/.

- 10.Cerdá M, Wall M, Keyes KM, et al. Medical marijuana laws in 50 states: investigating the relationship between state legalization of medical marijuana and marijuana use, abuse and dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;120(1-3):22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Timberlake DS, Haberstick BC, Hopfer CJ, et al. Progression from marijuana use to daily smoking and nicotine dependence in a national sample of U.S. adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(2-3):272–281. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agrawal A, Madden PAF, Bucholz KK, et al. Transitions to regular smoking and to nicotine dependence in women using cannabis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;95(1-2):107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.US Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. USDHHS, Office of Smoking and Health; Atlanta, GA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 14.US Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. USDHHS, Office of Smoking and Health; Atlanta, GA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall W, Solowij N. Adverse effects of cannabis. Lancet. 1998;352(9140):1611–1616. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)05021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall W. What has research over the past two decades revealed about the adverse health effects of recreational cannabis use? Addiction. 2014;110(1) doi: 10.1111/add.12703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smiley AM. Marijuana: on-road and driving simulator studies. Alcohol, Drugs Driv. 1986;2(3-4):121–134. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall W, Pacula RLP. Cannabis Use and Dependence: Public Health and Public Policy. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Budney AJ, Roffman R, Stephens RS, Walker D. Marijuana dependence and its treatment. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2007;4(1):4–16. doi: 10.1151/ascp07414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crane NA, Schuster RM, Fusar-Poli P, Gonzalez R. Effects of cannabis on neurocognitive functioning: recent advances, neurodevelopmental influences, and sex differences. Neuropsychol Rev. 2013;23(2):117–137. doi: 10.1007/s11065-012-9222-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solowij N, Pesa N. Cannabis and cognition: short and long-term effects. Marijuana and Madness. 2012;2:91–102. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solowij N, Stephens RS, Roffman RA, et al. Cognitive functioning of long-term heavy cannabis users seeking treatment. JAMA. 2002;287(9):1123–1131. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.9.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solowij N, Battisti R. The chronic effects of cannabis on memory in humans: a review. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2008;1(1):81–98. doi: 10.2174/1874473710801010081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meier MH, Caspi A, Ambler A, et al. Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(40):E2657–E2664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206820109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Os J, Bak M, Hanssen M, et al. Cannabis use and psychosis: a longitudinal population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(4):319–327. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henquet C, Krabbendam L, Spauwen J, et al. Prospective cohort study of cannabis use, predisposition for psychosis, and psychotic symptoms in young people. BMJ. 2005;330(7481):11. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38267.664086.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arseneault L, Cannon M, Poulton R, et al. Cannabis use in adolescence and risk for adult psychosis: longitudinal prospective study. BMJ. 2002;325(7374):1212–1213. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Swain-Campbell NR. Cannabis dependence and psychotic symptoms in young people. Psychol Med. 2003;33(1):15–21. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall W. The health and psychological effects of cannabis use. Curr Issues Crim Justice. 1994:6. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tetrault JM, Crothers K, Moore BA, et al. Effects of marijuana smoking on pulmonary function and respiratory complications: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(3):221–228. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.3.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tashkin DP, Baldwin GC, Sarafian T, et al. Respiratory and immunologic consequences of marijuana smoking. J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;42(11 Suppl):71S–81S. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.2002.tb06006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones RT. Cardiovascular system effects of marijuana. J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;42(11 Suppl):58S–63S. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.2002.tb06004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sidney S. Cardiovascular consequences of marijuana use. J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;42(11 Suppl):64S–70S. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.2002.tb06005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gottschalk LA, Aronow WS, Prakash R. Effect of marijuana and placebo-marijuana smoking on psychological state and on psychophysiological cardiovascular functioning in anginal patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1977;12(2):255–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mittleman MA, Lewis RA, Maclure M, et al. Triggering myocardial infarction by marijuana. Circulation. 2001;103(23):2805–2809. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.23.2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daling JR, Doody DR, Sun X, et al. Association of marijuana use and the incidence of testicular germ cell tumors. Cancer. 2009;115(6):1215–1223. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lacson JCA, Carroll JD, Tuazon E, et al. Population-based case-control study of recreational drug use and testis cancer risk confirms an association between marijuana use and nonseminoma risk. Cancer. 2012;118(21):5374–5383. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trabert B, Sigurdson AJ, Sweeney AM, et al. Marijuana use and testicular germ cell tumors. Cancer. 2011;117(4):848–853. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dinitto DM, Choi NG. Marijuana use among older adults in the U.S.A.: user characteristics, patterns of use, and implications for intervention. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(5):732–741. doi: 10.1017/S1041610210002176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Glintborg B, Olsen L, Poulsen H, et al. Reliability of self-reported use of amphetamine, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, cannabinoids, cocaine, methadone, and opiates among acutely hospitalized elderly medical patients. Clin Toxicol. 2008;46(3):239–42. doi: 10.1080/15563650701586397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rockett IRH, Putnam SL, Jia H, Smith GS. Declared and undeclared substance use among emergency department patients: a population-based study. Addiction. 2006;101(5):706–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Current Cigarette Smoking among Adults in the United States. CDC; Atlanta, GA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cataldo J, Peterson AB, Hunter M, et al. E-cigarette marketing and older smokers: road to renormalization. Am J Health Behav. 2015;39(3):361–371. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.39.3.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sallis JF, Owen N, Fisher EB. Ecological models of health behavior. In: Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice . Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2008. pp. 465–486. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wellman RJ, DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, et al. Measuring adults’ loss of autonomy over nicotine use: the Hooked on Nicotine Checklist. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7(1):157–161. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331328394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom K-O. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Addiction. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pomerleau CS, Carton SM, Lutzke ML, et al. Reliability of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire and the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence. Addict Behav. 1994;19(1):33–39. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)90049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wellman RJ, Savageau JA, Godiwala S, et al. A comparison of the Hooked on Nicotine Checklist and the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence in adult smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8(4):575–580. doi: 10.1080/14622200600789965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Fletcher K, et al. Susceptibility to nicotine dependence: the development and assess ment of nicotine dependence in youth 2 study. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):e974–e983. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dinieri JA, Hurd YL. Rat models of prenatal and adolescent cannabis exposure. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;829:231–242. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-458-2_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Colliver JD, Compton WM, Gfroerer JC, Condon T. Projecting drug use among aging baby boomers in 2020. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16(4):257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rey JM, Tennant CC. Cannabis and mental health. BMJ. 2002;325(7374):1183–1184. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grant BF. Comorbidity between DSM-IV drug use disorders and major depression: results of a national survey of adults. J Subst Abuse. 1995;7(4):481–497. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(95)90017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miles DR, van den Bree MB, Gupman AE, et al. A twin study on sensation seeking, risk taking behavior and marijuana use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;62(1):57–68. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00165-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]