Abstract

Miltefosine causes leishmanial death, but the possible mechanism(s) of action is not known. The mode of action of miltefosine was investigated in vitro in Leishmania donovani promastigotes as well as in extra- and intracellular amastigotes. Here, we demonstrate that miltefosine induces apoptosis-like death in L. donovani based on observed phenomena such as nuclear DNA condensation, DNA fragmentation with accompanying ladder formation, and in situ labeling of DNA fragments by the terminal deoxyribonucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling method. Understanding of miltefosine-mediated death will facilitate the design of new therapeutic strategies against Leishmania parasites.

Miltefosine (1-O-hexadecylphosphocholine), an alkylphosphocholine and a membrane-active synthetic ether-lipid analogue originally developed for the treatment of cutaneous metastasis from mammary carcinomas (21, 32), has proved to be an effective treatment for human visceral leishmaniasis (25, 38, 52-55). It has been hailed as potentially the first oral treatment of human leishmaniasis (8, 15, 16, 20, 25, 31, 47, 50). The leishmaniacidal activities of miltefosine have been associated with perturbation of the alkyl-phospholipid metabolism and the biosynthesis of alkyl-anchored glycolipids and glycoproteins (33, 34). Although potential antitumor cell mechanisms of action of miltefosine have been elaborated in mammalian cells (13, 44), its exact mode(s) of cytotoxicity has not been determined in Leishmania spp. (9, 25, 39, 46, 48, 55). It has been known to induce apoptotic death in various cancer cell lines (13, 28, 32, 43, 60). However, it is not yet established whether miltefosine can bring about apoptosis-like death in all the forms of Leishmania parasite.

There are now increasing numbers of reports regarding unicellular organisms undergoing apoptosis-like death, whose induction is not obligatory but activated under threatening circumstances (1, 36, 49). Cell death resembling metazoan apoptosis has been reported in several parasitic protozoans (4, 10, 30, 36, 49, 59, 61). Apoptosis greatly affects the host-parasite relationship, since the survival of the parasite inside the vector as well as in the macrophage requires strict control of the population of the parasite (12, 58). Apoptosis could be a useful mechanism to avoid killing of the entire population (36) and thus influence the chemotherapeutic strategies to limit the parasite (11).

In the present study we sought to determine the mode of action of miltefosine in Leishmania donovani promastigotes as well as extra- and intracellular amastigotes. We have demonstrated that miltefosine causes apoptosis-like death in L. donovani. Our data set the stage for future development of this class of drug for better treatment of leishmaniasis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Miltefosine was a kind gift from Zentaris (Frankfurt, Germany). RPMI 1640 culture medium was from Gibco BRL. Fetal calf serum was obtained from Biological Industries (Kibbutz Beit Haemek, Israel). ApoAlert DNA fragmentation assay kit was purchased from BD Biosciences Clontech (Palo Alto, Calif.). Mouse monoclonal anti-poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) antibody was purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, Calif.). A phototope-horseradish peroxidase Western blot detection kit and anti-mouse immunoglobulin G antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, Mass.). All other chemicals, unless attributed explicitly, were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, Mo.). All the plasticwares used were from Tarsons (Kolkata, India).

Promastigote culture and treatments.

Promastigotes of L. donovani (strain MHOM/80/IN/Dd8) were cultured as described previously (23, 24, 27, 40-42). Briefly, 0.5 × 106 cells/ml were routinely inoculated and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (pH 7.2, containing 25 mM HEPES) enriched with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum and antibiotics, at 24°C for 96 h before subculturing reaching up to 20 × 106 to 25 × 106 cells/ml. For the drug treatment, different concentrations of miltefosine (as indicated in the respective experiments) were added after 48 h of proliferation of the cells. The untreated and miltefosine-treated samples were further incubated for another 48 h at 24°C and harvested. Drug solutions were prepared as 10 mM stocks in the appropriate medium immediately before the assay.

Isolation of macrophages and amastigotes and in vitro infection of macrophages by amastigotes.

Peritoneal macrophages were isolated from Chinese hamsters as described previously (7). The Leishmania-infected Chinese hamster model already exists in the National Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research. Intracellular amastigotes were isolated and purified from spleens of Leishmania-infected hamsters as described by Hart et al. (18). In vitro macrophage infection was performed per the standard protocol that is followed in our laboratory. Briefly, isolated macrophages were washed with prewarmed RPMI 1640 medium. They were then seeded on coverslips in tissue culture plates and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 24 h. Nonadherent cells were removed by two washes with prewarmed phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4). Adherent macrophages were infected with amastigotes at a parasite-to-macrophage ratio of 20:1 for 3 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. Noninternalized amastigotes were removed by gentle washing twice with PBS. Infected macrophages were further incubated in the presence or absence of the drug for 24 h. Macrophages were stained with Giemsa stain, and the amastigotes inside the macrophage (100 macrophages per treatment) were counted under a microscope. The use of animals for all the experiments was in compliance with the relevant laws and guidelines of the institutional animal ethics committee.

In vitro cell cytotoxicity (antileishmanial activity) assay.

MTT [3-(4,5-imethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] cell proliferation assay is a colorimetric assay system, which measures the mitochondrial enzyme reduction of tetrazolium dye (MTT) into an insoluble formazan product by the viable cells. The antileishmanial activity was performed by the MTT assay as described earlier (40). Briefly, 0.125 × 106 L. donovani promastigotes from a logarithmic phase culture were grown in a flat-bottom 96-well culture microplate with 300 μl of culture medium. They were treated with or without various concentrations of miltefosine after 48 h and allowed to grow further for another 48 h. MTT solution was added to each well to a final concentration of 400 μg/ml, and the plates were incubated for 3 h at 24°C. Cells were centrifuged at 6,000 × g for 10 min. Pellets (purple formazan product, indicative of the reduction of MTT) were dissolved in 100 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide and further incubated for 15 min. The absorbance was read on an automated microplate reader (Powerpack 200; Biotek Instruments, Winooski, Vt.) at 540 nm. The amount of color produced is directly proportional to the number of viable (metabolically active) cells. Relative numbers of live cells could therefore be determined based on the optical absorbance of the sample. The value for the blank well was subtracted from each well of treated and untreated (control) cells, and the mean percentage of posttreatment viable cells was calculated relative to the control as follows: % viable cells = (AT − AB)/(AC − AB) × 100, where AC is the absorbance of the control (mean value), AT is the absorbance of the treated cells (mean value), and AB is the absorbance of the blank (mean value). Results were expressed as the concentration inhibiting parasite growth by 50% (50% inhibitory concentration [IC50]). Cell proliferation was also measured by cell counting in a Neubauer chamber.

Determination of cellular morphology.

To observe changes in cellular morphology, untreated and miltefosine-treated cells were harvested by low-speed centrifugation (1,600 × g) and resuspended in PBS. Aliquots of the suspension were placed on glass slides, covered with coverslips, and sealed. Cells were observed under magnifications of ×100 on a Nikon E600 microscope equipped with a differential interference contrast module (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). For recording of alterations in cellular morphology, treated and untreated cells were observed at different time points. Images were processed using Image-Pro Express (Media Cybernetics, Madison, Wis.) and Adobe Photoshop 5.5 (Adobe Systems Inc., Mountain View, Calif.) softwares. At least 20 microscopic fields were observed for each sample.

Detection of DNA condensation by propidium iodide staining.

To observe the DNA condensation in promastigotes and amastigotes, untreated and miltefosine-treated cells were stained with propidium iodide (PI) as described previously (44), with minor modifications. Briefly, cells were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde onto poly(l-lysine)-coated slides. The adherent cells were permeabilized with 0.2% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 for 1 min and washed with PBS. They were then incubated with PI (10 μg/ml) for 2 min. Subsequently, cells were observed using a Nikon E600 microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan), and images were processed as described above. At least 20 microscopic fields were observed for each sample.

Oligonucleosomal-DNA fragmentation assay.

To determine the presence of DNA fragments generated as a function of cell death, total cellular DNA from promastigotes as well as extracellular amastigotes was isolated by a previously described procedure (45) with minor modifications. Briefly, pellets of 10 × 106 cells were treated with sarcosyl detergent lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, 10 mM EDTA, 0.5% [wt/vol] sodium-N-lauryl sarcosine; pH 7.5) and proteinase K (15.6 mg/ml) and incubated overnight at 50°C. The lysates were then extracted with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 5 min. To the upper phase, 0.3 M sodium acetate and 100% ethanol (twice the volume) were added, and the mixture was kept overnight at −20°C. The sample was centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 min. The DNA pellet was washed with 0.5 ml of 70% (vol/vol) ethanol and solubilized in TE (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA; pH 8.0). RNase A (0.3 mg/ml) treatment was given for 1 h at 37°C. Extracted DNA was quantified spectrophotometrically at 260/280 nm. A total of 10 μg of DNA was mixed with tracking dye and run on 1% agarose gels containing ethidium bromide in TAE buffer (40 mM Tris-acetate, 1 mM EDTA; pH 8.0). Gels were run for 2 h at 50 V and visualized under UV light.

In situ labeling of DNA fragments by TUNEL.

In situ detection of DNA fragments by terminal deoxyribonucleotidyltransferase (TdT)-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) was performed using the ApoAlert DNA fragmentation assay kit following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, L. donovani promastigotes and extracellular amastigotes treated with or without miltefosine were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (wt/vol) and placed on poly(l-lysine)-coated slides. In situ TUNEL assay for intracellular amastigotes was done with amastigote-infected macrophages grown on coverslips as described by Holzmuller et al. (20) with minor modifications. Cells were permeabilized with 0.2% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 and equilibration buffer (200 mM potassium cacodylate, 25 mM Tris-HCl, 0.2 mM dithiothreitol, bovine serum albumin [0.25 mg/ml], 2.5 mM cobalt chloride) for 10 min at room temperature. Slides were layered with TUNEL reaction mixture containing nucleotide mix (50 μM fluorescein-12-dUTP, 100 μM dATP, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA; pH 7.6) and TdT and incubated for 1 h at 37°C in a humid chamber. The samples were counterstained with PI (10 μg/ml) and visualized under a Nikon E600 fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Images were captured and processed as described above. At least 20 microscopic fields were observed for each sample.

Statistical analysis.

In vitro antileishmanial activity was expressed as the IC50 by linear regression analysis. Values expressed are means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) from three independent experiments.

RESULTS

Determination of in vitro IC50 of miltefosine-mediated death in L. donovani promastigotes.

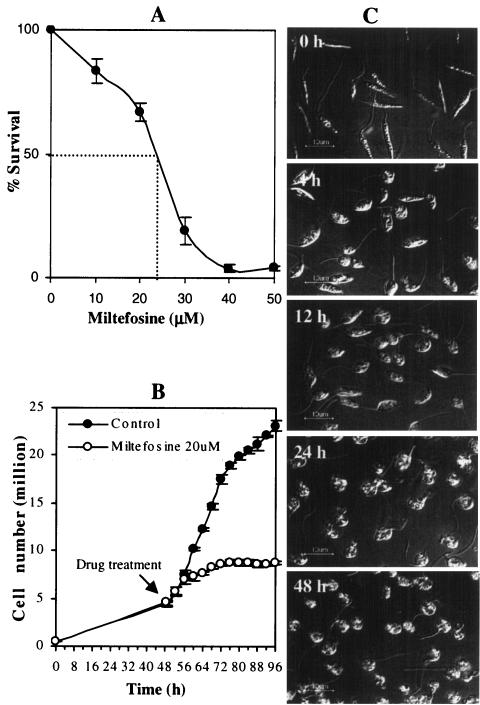

In order to determine the concentration of miltefosine at which approximately 50% death of L. donovani promastigotes would occur, we had tested the effect of several concentrations of the drug using the MTT assay. Data show a biphasic killing of Leishmania promastigotes under the in vitro conditions (Fig. 1A). The death profile was initially slow when concentrations up to 20 μM were used. Subsequently, a very rapid and dose-dependent death occurred with miltefosine concentrations between 20 and 50 μM, reaching approximately 100% at around 40 μM. Approximately 50% death was observed with miltefosine at a concentration of 25 μM (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Leishmaniacidal activity of miltefosine on L. donovani promastigotes. (A) Cell viability of promastigotes treated with or without different concentrations of miltefosine was measured by MTT assay as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as the means ± SEM (error bars) of three independent experiments. (B) Cell number (live and moving) of promastigotes treated with or without miltefosine (25 μM) at different time points after miltefosine treatment. Results are expressed as the means ± SEM (error bars) of three independent experiments. (C) Promastigotes at different time points after miltefosine (25 μM) treatment.

Determination of miltefosine-mediated regulation of proliferation and morphology of L. donovani promastigotes.

In order to obtain a clue(s) to the possible action of miltefosine in causing the death of L. donovani promastigotes, they were treated with or without a 25 μM concentration (IC50) of miltefosine and observed under a microscope at 4-h intervals after drug treatment up to another 46 h. No effect of the drug was observed till the first 4 h after drug treatment (Fig. 1B). The average number of cells at the time of drug treatment was 5 million/ml. The drug-treated cells grew up to 7 to 8 million/ml in the next 8 h after treatment and remained constant till 96 h compared to the untreated samples, which grew up to 20 to 25 million/ml till 96 h (Fig. 1B). A visual inspection under a differential interference contrast microscope of promastigotes with or without treatment with the IC50 of miltefosine at 4, 12, 24, and 48 h after treatment revealed cell shrinkage, beginning around 4 h after drug treatment. Approximately 50% of cells developed the phenotype compared to the control. By the end of 48 h, almost all the cells showed cytoplasmic condensation and shrinkage, resulting in complete circularization and substantial reduction in size compared to the control samples (Fig. 1C).

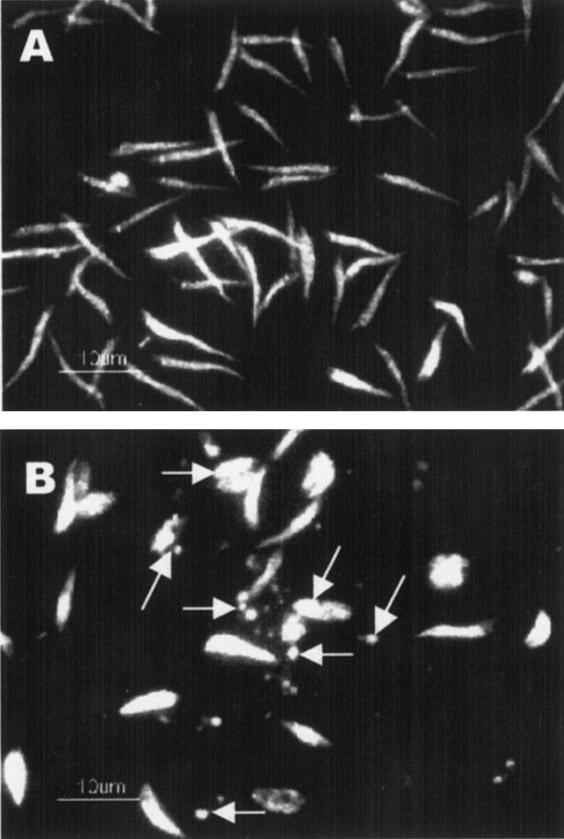

Determination of mode of miltefosine-mediated death in promastigotes of L. donovani. (i) Miltefosine treatment induces nuclear condensation.

Having observed that miltefosine treatment induces death and severe morphological changes in promastigotes, we next investigated the mode of miltefosine-induced cell death. We undertook a study of the condensation of nuclear material, which is a part of the process leading to apoptosis. Propidium iodide was used as a stain to detect nuclear condensation. Condensed nuclei exhibit brighter red fluorescence than noncondensed nuclei, which show dull red fluorescence. Promastigotes treated with 25 μM miltefosine showed bright red fluorescent spots compared to the normal dull red fluorescence in untreated cells (Fig. 2B versus A). Data suggest that nuclear condensation occurs in L. donovani promastigotes during the miltefosine-induced cell killing, which is suggestive of an apoptosis-like death process.

FIG. 2.

DNA condensation in L. donovani promastigotes after miltefosine treatment. L donovani promastigotes were treated with or without miltefosine (25 μM) for 48 h and were subjected to PI staining. (A) Untreated promastigotes; (B) miltefosine-treated promastigotes. Arrows indicate representative condensed nuclei. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

(ii) Determination of PARP cleavage in L. donovani promastigotes during miltefosine-mediated cell death.

PARP is a DNA repair enzyme that undergoes cleavage during the process of induction of apoptosis. Since the presence of cleaved PARP is a feature of apoptosis, we sought to detect cleaved PARP in miltefosine-treated Leishmania promastigotes. Cells treated with or without the IC50 of miltefosine showed no cleavage of PARP under any condition tested (data not shown). Previously PARP-independent protozoan apoptosis has been reported (22, 35, 51).

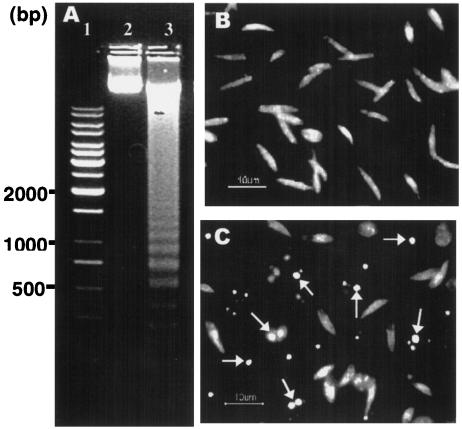

(iii) Oligonucleosomal-DNA fragmentation analysis of treated promastigotes indicates apoptosis-like cell death.

Based on the data suggesting nuclear condensation in promastigotes, we sought to further investigate the possibility of apoptotic cell death mediated by miltefosine. Degradation of nuclear DNA into nucleosomal units is one of the hallmarks of apoptotic cell death (10). Oligonucleosomal-DNA fragmentation analysis of promastigotes treated with 25 μM miltefosine showed clear fragmentation of genomic DNA into oligonucleosomal fragments in the characteristic ladder form in agarose gel electrophoresis as seen during apoptosis, compared to untreated promastigotes (Fig. 3A, compare lanes 3 and 2).

FIG. 3.

DNA fragmentation in L. donovani promastigotes with or without miltefosine treatment. (A) Genomic DNA (10 μg) from treated and untreated promastigotes was resolved on 1% agarose gel. Lane 1, 1-kb ladder (MBI Fermentas); lane 2, DNA from untreated promastigotes; lane 3, DNA from promastigotes treated with an IC50 dose of miltefosine. (B) In situ TUNEL-stained untreated promastigotes. (C) In situ TUNEL-stained promastigotes treated with an IC50 dose of miltefosine. Arrows indicate representative TUNEL-positive cells. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

To further characterize the changes occurring in the nuclear material during cell death mediated by miltefosine, in situ TUNEL staining was performed to detect the free ends of DNA after breakage, which is one of the important biochemical hallmarks of eukaryotic apoptosis (10). Promastigotes treated with 25 μM miltefosine showed TdT-labeled nuclei, which brightly fluoresced yellowish green, indicating DNA fragmentation, compared to untreated promastigotes, which did not show any TUNEL-positive cells (Fig. 3C and B). Observed data thus provide strong evidence suggesting that miltefosine causes death of L. donovani promastigotes by inducing an apoptosis-like process.

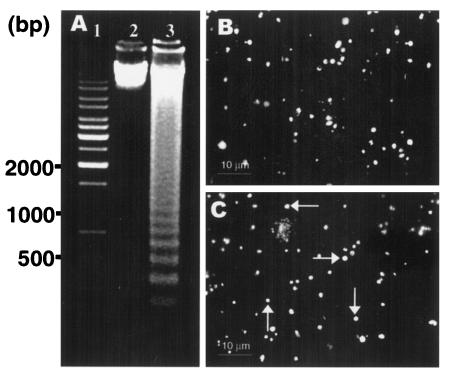

Determination of mechanism of miltefosine-mediated death in amastigotes of L. donovani.

Miltefosine induces oligonucleosomal-DNA fragmentation in extracellular amastigotes. Having observed miltefosine-mediated apoptosis-like processes in promastigotes, we extended similar studies to the Leishmania amastigote, which is the infective stage of the parasite (5, 14, 26). Amastigotes isolated from the spleens of infected Chinese hamsters were subjected to similar drug treatment, and genomic DNA was analyzed for the presence of oligonucleosomal fragments by the same procedure described above. Extensive DNA fragmentation into oligonucleosomal fragments in ladder form could be detected in miltefosine-treated amastigotes (Fig. 4A, lanes 3 and 2). Untreated amastigotes did not show any DNA fragmentation (Fig. 4A, lane 2). Endonuclease activity was also evaluated by using an in situ TUNEL staining method. TdT-labeled nuclei, which brightly fluoresced yellowish green, were detected in miltefosine-treated amastigotes whereas labeling was absent in the untreated amastigotes (Fig. 4C and B). Thus, miltefosine was able to induce DNA fragmentation leading to apoptosis-like death in the Leishmania amastigotes in a way similar to that observed in the promastigotes.

FIG. 4.

DNA fragmentation in L. donovani amastigotes with or without miltefosine treatment. (A) Genomic DNA (10 μg) from treated and untreated amastigotes was resolved on 1% agarose gel. Lane 1, 1-kb ladder (MBI Fermentas); lane 2, DNA from untreated amastigotes; lane 3, DNA from amastigotes treated with an IC50 dose of miltefosine. (B) In situ TUNEL-stained untreated amastigotes. (C) In situ TUNEL-stained amastigotes treated with an IC50 dose of miltefosine. Arrows indicate representative TUNEL-positive cells. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

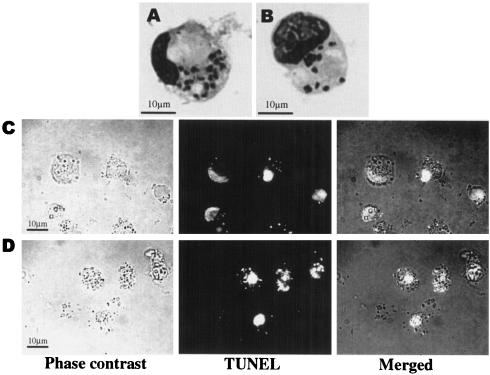

In situ DNA fragmentation mediated by miltefosine on intracellular amastigotes of L. donovani.

Having observed apoptosis-like phenomena induced by miltefosine in extracellular amastigotes, we decided to conclusively prove miltefosine-mediated apoptosis-like death in the clinically relevant infective stage of Leishmania within the host cell and studied the effects of the drug on intracellular amastigotes in infected macrophages. Peritoneal macrophages isolated from Chinese hamsters were infected in vitro with amastigotes and cultured in the presence (25 μM) or absence of miltefosine. Treatment with miltefosine killed intracellular L. donovani amastigotes as detected by the reduction in the number of intracellular amastigotes per macrophage by Giemsa staining (Fig. 5B versus A). The amastigote-infected macrophages treated with or without miltefosine (25 μM) were subjected to an in situ TUNEL assay. The nuclear DNA fragmentation of intracellular amastigotes, as determined by the green fluorescence, was clearly visible inside the macrophages treated with miltefosine compared to the untreated amastigotes, which did not pick up green stain (Fig. 5D versus C). Macrophage nuclei were stained red, indicating that no damage to the macrophage nuclei was caused by miltefosine treatment at this concentration. Our results thus confirm that miltefosine induces apoptosis-like death process in L. donovani.

FIG. 5.

In situ analysis (TUNEL staining) of apoptosis in L. donovani amastigote-infected macrophages. (A) Giemsa-stained macrophage infected with amastigotes. (B) Giemsa-stained macrophage infected with amastigotes treated with 25 μM miltefosine. (C) In situ TUNEL-stained untreated amastigote-infected macrophages. (D) In situ TUNEL-stained amastigote-infected macrophages treated with an IC50 dose of miltefosine. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Apoptosis-like changes have been reported for Trypanosoma cruzi (1), Leishmania amazonensis (36), and L. donovani (10), in response to G-418 antibiotic, heat shock, and hydrogen peroxide, respectively. In order to clarify the mode of action of miltefosine against L. donovani, we have investigated the type of cell death induced by this drug and observed that at the IC50 the drug precipitates a type of cell death in Leishmania that shares many characteristics with metazoan apoptosis. PI staining, oligonucleosomal-DNA fragmentation, and in situ TUNEL staining of condensed and fragmented nuclei due to miltefosine treatment revealed the strong possibility of an apoptosis-like mode of cell death in L. donovani promastigotes. Similar observations were reported recently by Paris et al. (37). Further studies in the extracellular and intracellular amastigotes established that miltefosine indeed induces apoptosis-like death in L. donovani.

Considerable similarities exist between metazoan apoptosis and protozoan apoptosis (11). Observations of both DNA condensation and DNA laddering are in agreement with prominent features observed during metazoan apoptosis. PARP, a DNA repair enzyme, is cleaved by caspases in metazoans during apoptosis (57). A similar process involving the cleavage of a PARP-like protein during apoptosis in Leishmania due to treatment with hydrogen peroxide has been reported using antibody raised against mammalian PARP (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.) (10); however, the molecular size of the PARP-like protein that was detected in Leishmania by the antibody was found to be less (78-kDa intact protein and 63-kDa cleaved fragments) (10) than the sizes of proteins in mammalian systems (113-kDa intact protein and 85-kDa cleaved fragments) (29) tested so far. Leishmania major cysteine proteinases has been reported to process human nuclear PARP into a 40-kDa fragment (3) and not into the 85-kDa fragment that is processed by human effector caspases (29). In our study no PARP cleavage could be detected by the antibody in Leishmania due to miltefosine treatment. Caspase-independent apoptosis has been reported in several organisms (35, 46, 51). A recent report finds no caspase homologue yet in unicellular eukaryotes (2). While genes encoding metacaspases, belonging to an ancestral metacaspase/paracaspase/caspase superfamily, have been identified in plants, fungi, and several unicellular eukaryotes, including protozoa (2), no information is available about their potential involvement in cell death (3). Alternative pathways resulting in caspase-independent apoptotic cell death have been reported in promastigotes and amastigotes of L. major and Leishmania mexicana upon serum deprivation (11, 61). Nuclease activation independent of caspase 1, caspase 3, calpain, cysteine protease, or proteasome activation has been reported in L. infantum amastigotes (49). Nitric oxide-mediated cell death was also demonstrated in L. amazonensis amastigotes, which induced extensive DNA fragmentation, not due to activation of caspase-like activity, but due to noncaspase protease of proteasomes (22).

It has been suggested that mitogenic-signal transduction and second-messenger generation via inhibition of protein kinase C (PKC) might be a possible mode of action (56). However, inhibition of PKC did not necessarily match with the antiproliferative activity of miltefosine, and PKC-depleted cells did not alter their sensitivity towards the drug (19). Phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis has been shown to be inhibited by miltefosine (17). Miltefosine has been considered to inhibit the translocation of CTP:phosphocholine-cytidyltransferase, the key enzyme of phosphocholine biosynthesis, from its inactive cytosolic form to its active membrane-bound form (9). In addition, sphingomyelin biosynthesis has been shown to be inhibited by miltefosine, leading to increased levels of cellular ceramide (60). It has also been suggested that the increased levels of cellular ceramide trigger apoptosis in HL-60 and U-937 leukemic cells (28). Studies on L. mexicana suggested that miltefosine might cause perturbation of ether-lipid metabolism, GPI anchor biosynthesis, and leishmanial signal transduction (33). Later, Lux et al. (34) showed inhibition of the glycosome-located alkyl-specific acyl coenzyme A acyltransferase in L. mexicana, an enzyme involved in lipid remodeling, by miltefosine in a dose-dependant manner. However, the IC50 for inhibition of this enzyme was 50 μM (9), making it unlikely to be the primary target. Miltefosine also interferes with cellular carrier systems. Inhibition of the incorporation of 14C-labeed desoxyglucose, choline, and methionine has been shown in cancer cells (6). Interference with the carrier proteins could lead to depletion of essential nutrients and thus contribute to growth arrest and cell death. Furthermore, Na+-, K+-ATPase has been reported to be inhibited by miltefosine (6). However, in these studies experiments were not undertaken to determine whether miltefosine-induced killing occurs by apoptosis or necrosis. Moreover, there is no report on the mechanism of miltefosine action on amastigote forms of the parasite.

The combined use of several techniques, including PI and in situ TUNEL staining, DNA condensation, and fragmentation assay, conclusively proves that L. donovani undergoes apoptosis-like cell death due to miltefosine treatment. Further studies may shed light on possible targets of miltefosine action. As miltefosine has been in clinical use in recent years as an antileishmanial therapy, a better understanding of mechanisms that regulate cell death may help us to design new therapeutic strategies against Leishmania parasites. The mechanism of miltefosine action described in this study needs more attention and should be considered in future experimental animal and clinical studies. Further studies are needed to see the effects of miltefosine action on strains that have become resistant to commonly used drugs.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. L. Kaul, NIPER, for his keen interest in this study. We thank R. Mahajan for providing us with the Leishmania donovani strain MHOM/80/IN/Dd8 and S. S. Sharma for providing the peritoneal macrophages and amastigotes used in this study. We acknowledge K. G. Jayanarayan and A. Khurana for their support in executing some experiments and helpful discussions. R. Singh is acknowledged for his assistance in the laboratory.

N.K.V. is recipient the of a Research Associateship from NIPER.

Footnotes

NIPER communication no. 288.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ameisen, J. C. 1996. The origin of programmed cell death. Science 272:1278-1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnoult, D., K. Akarid, A. Grodet, P. X. Petit, J. Estaquier, and J. C. Ameisen. 2002. On the evaluation of programmed cell death: apoptosis of the unicellular eukaryote Leishmania major involves cysteine proteinase activation and mitochondrion permeabilization. Cell Death Differ. 9:65-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arvind, L., V. M. Dixit, and E. V. Konin. 2001. Apoptotic molecular machinery: vastly increased complexity in vertebrates revealed by genome comparisons. Science 291:1279-1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balanco, J. M. F., M. E. C. Moreira, A. Bonomo, P. T. Bozza, G. A. Mendes, C. Pirmez, and M. A. Barcinski. 2001. Apoptotic mimicry by an obligate intracellular parasite downregulates macrophage microbial activity. Curr. Biol. 11:1870-1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basselin, M., F. Lawrence, and M. Robert-Gero. 1996. Pentamidine uptake in Leishmania donovani and Leishmania amazonensis, promastigotes and amastigotes. Biochem. J. 315:631-634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berkovic, D., E. A. M. Fleer, H. Eibl, and C. Unger. 1992. Effects of hexadecylphosphocholine on cellular function. Prog. Exp. Tumor Res. 34:59-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaudhuri, G., A. Mukhopadhyay, and S. K. Basu. 1989. Selective delivery of drugs to macrophages through a highly specific receptor. Biochem. Pharmacol. 38:2995-3002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Croft, S., L. D. Snowdon, and V. Yardly. 1996. The activities of four anticancer alkyllysophospholipids against Leishmania donovani, Trypanosoma cruzi and Trypanosoma brucei. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 38:1041-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Croft, S. L., K. Seifert, and M. Duchene. 2003. Antiprotozoal activities of phospholipid analogues. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 126:165-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das, M., S. B. Mukherjee, and C. Shaha. 2001. Hydrogen peroxide induces apoptosis-like death in Leishmania donovani promastigotes. J. Cell Sci. 114:2461-2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Debrabant, A., N. Lee, S. Bertholet, R. Duncan, and H. L. Nakhasi. 2003. Programmed cell death in trypanosomatids and other unicellular organisms. Int. J. Parasitol. 33:257-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DosReis, G. A., and M. A. Barcinski. 2001. Apoptosis and parasitism: from the parasite to the host immune response. Adv. Parasitol. 49:133-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engelmann, J., J. Henke, and W. Willker. 1996. Early stage monitoring of miltefosine induced apoptosis in KB cells by multinuclear NMR spectroscopy. Anticancer Res. 16:1429-1440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ephros, M., A. Bitnun, P. Shaked, E. Waldman, and D. Zilbersten. 1999. Stage-specific activity of pentavalent antimony against Leishmania donovani axenic amastigotes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:278-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Escobar, P., S. Matu, C. Marques, and S. L. Croft. 2002. Sensitivity of Leishmania species to hexadecylphosphocholine (miltefosine), ET-18-OCH3 (eldefosine) and amphotericin B. Acta Trop. 81:151-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganguly, N. K. 2002. Oral miltefosine may revolutionize treatment of visceral leishmaniasis. TDR News W. H. O. 68:2. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haase, R., T. Wieder, C. C. Geilen, and W. Reutter. 1991. The phospholipid analogue hexadecylphosphocholine inhibits phosphocholine biosynthesis in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. FEBS Lett. 288:129-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hart, D. T., K. Vickerman, and G. H. Coombs. 1981. A quick, simple method for purifying Leishmania mexicana amastigotes in large numbers. Parasitology 82:345-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heesbeen, E. C., L. F. Verdonck, G. E. Staal, and G. Rijksen. 1994. Protein kinase C is not involved in the cytotoxic action of 1-octadecyl-2-o-methyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphocholine in HL-60 and K562 cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 47:1481-1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herwaldt, B. L. 1999. Miltefosine: the long awaited therapy for visceral leishmaniasis? N. Engl. J. Med. 341:1840-1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hilgard, P., T. Klenner, J. Stekar, and C. Unger. 1993. Alkylphosphocholines: a new class of membrane active anticancer agents. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 32:90-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holzmuller, P., D. Sereno, M. Cavaleyra, L. Mangot, S. Daulouede, P. Vincendeau, and J. L. Lemesre. 2002. Nitric oxide-mediated proteosome-dependent oligonucleosomal DNA fragmentation in Leishmania amazonensis. Infect. Immun. 70:3727-3735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jayanarayan, K. G., and C. S. Dey. 2002. Resistance to arsenite modulates expression of β- and γ-tubulin and sensitivity to paclitaxal during differentiation of Leishmania donovani. Parasitol. Res. 88:754-759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jayanarayan, K. G., and C. S. Dey. 2003. Overexpression and DNA topoisomerase II-like enzyme activity in arsenite resistant Leishmania donovani. Microbiol. Res. 158:55-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jha, T. K., S. Sunder, C. P. Thakur, P. Bachmann, J. Karbwang, C. Fischer, A. Voss, and J. Berman. 1999. Miltefosine, an oral agent, for the treatment of Indian visceral leishmaniasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 341:1795-1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joshi, M., D. M. Dwyer, and H. L. Nakhasi. 1993. Cloning and characterization of expressed genes from in vitro grown amastigotes of Leishmania donovani. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 58:345-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaur, J., and C. S. Dey. 2000. Putative P-glycoprotein expression in arsenite resistant Leishmania donovani down regulated by verapamil. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 271:615-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Konstantinov, S. M., H. Eibl, and M. R. Berger. 1998. Alkylphosphocholines induce apoptosis in HL-60 and U-937 leukemic cells. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 41:210-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lazebnik, Y. A., S. H. Kaufmann, S. Desnoyers, C. G. Poirier, and W. C. Earnshaw. 1994. Cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase by a proteinase with properties like ICE. Nature 371:346-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee, N., S. Bertholet, A. Debrabant, J. Mullar, R. Duncan, and H. L. Nakhasi. 2002. Programmed cell death in the unicellular protozoan parasite Leishmania. Cell Death Differ. 9:53-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Le Fichoux, Y., D. Rousseau, B. Ferrua, S. Ruette, A. Lelievre, D. Grousson, and J. Kubar. 1998. Short- and long-term efficacy of hexadecylphosphocholine against established Leishmania infantum infection in BALB/c mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:654-658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leonard, R., J. Hardy, G. van Tienhoven, S. Houston, P. Simmonds, M. David, and J. Mansi. 2001. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial of 6% miltefosine solution, a topical chemotherapy in cutaneous metastases from breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 19:4150-4159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lux, H., D. T. Hart, P. J. Parker, and T. Klenner. 1996. Ether lipid metabolism, GPI anchor biosynthesis, and signal transduction are putative targets for antileishmanial alkyl phospholipids analogues. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 416:201-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lux, H., N. Heise, T. Klenner, D, Hart, and F. R. Opperdoes. 2000. Ether-lipid (alkyl-phspholipid) metabolism and the mechanism of action of ether-lipid analogues in Leishmania. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 111:1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsuyama, S., and J. C. Reed. 2000. Mitochondria-dependent apoptosis and cellular pH regulation. Cell Death Differ. 7:1155-1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moreira, M. E. C., H. A. D. Portillo, R. V. Milder, J. M. F. Balanco, and M. A. Barcinski. 1996. Heat shock induction of apoptosis in promastigotes of the unicellular organism Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis. J. Cell Physiol. 167:305-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paris, C., P. M. Loiseau, C. Bories, and J. Breard. 2004. Miltefosine induces apoptosis-like death in Leishmania donovani promastigotes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:852-859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pearson, R. D. 2003. Development status of miltefosine as first oral drug in visceral and cutaneous leishmaniasis. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 5:41-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perez-Victoria, F. J., S. Castanysand, and F. Gamarro. 2003. Leishmania donovani resistant to miltefosine involves a defective inward translocation of the drug. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2397-2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prasad, V., J. Kaur, and C. S. Dey. 2000. Arsenite resistant Leishmania donovani promastigotes express an enhanced membrane P-type adenosine triphosphatase activity that is sensitive to verapamil treatment. Parasitol. Res. 86:661-664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prasad, V., S. S. Kumar, and C. S. Dey. 2000. Resistant to arsenite modulates levels of α-tubulin and sensitivity to paclitaxal in Leishmania donovani. Parasitol. Res. 86:838-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prasad, V., and C. S. Dey. 2000. Tubulin is hyperphosphorylated on serine and tyrosine residues in Leishmania donovani promastigotes. Parasitol. Res. 86:876-880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ruiter, G. A., S. F. Zerp, H. Bartelink, W. J. Van Blitterswijk, and M. Verheij. 2003. Anti-cancer alkyl-lysopholipids inhibits the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt/PKB survival pathway. Anticancer Drugs 14:167-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rybczynska, M., M. Spitaler, N. G. Knebel, G. Boeck, H. Grunicke, and J. Hofmann. 2001. Effect of miltefosine on various biochemical parameters in a panel of tumor cell lines with different sensitivities. Biochem. Pharmacol. 62:765-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed., vol. I-III. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 46.Saraiva, V. B., D. Gibaldi, J. O. Previato, L. M. Previato, M. T. Bozza, C. G. Freire-de-Lima, and N. Heise. 2002. Proinflammatory and cytotoxic effects of hexadecylphosphocholine (miltefosine) against drug-resistant strains of Trypanosama cruzi. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3472-3477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schmidt-Ott, R., T. Klenner, P. Overath, and T. Aebischer. 1999. Topical treatment with hexadecylphosphocholine (Miltex) efficiently reduces parasite burden in experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 93:85-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seifert, K., S. Matu, F. Javier Perez-Victoria, S. Castanys, F. Gamarro, and S. L. Croft. 2003. Characterisation of Leishmania donovani promastigotes resistant to hexadecylphosphocholine (miltefosine). Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 22:380-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sereno, D., P. Holzmuller, I. Mangot, G. Cuny, A. Ouaissi, and J. L. Lemesre. 2001. Antimonial-mediated DNA fragmentation in Leishmania infantum amastigotes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2064-2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Soto, J., J. Toledo, P. Gutierez, R. S. Nicholls, J. Padila, J. Engel, C. Fischer, A. Voss, and J. Berman. 2001. Treatment of American cutaneous leishmaniasis with miltefosine, an oral agent. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33:E57-E61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sperandio, S., L. de Belle, and D. E. Bredesen. 2000. An alternative non-apoptotic form of programmed cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:14376-14381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sundar, S., F. Rosenkaimer, M. K. Makharia, A. K. Goyel, A. K. Mandal, A. Voss, P. Hilgard, and H. W. Murray. 1998. Trial of oral miltefosine for visceral leishmaniasis. Lancet 352:1821-1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sundar, S., L. B. Gupta, M. K. Makharia, M. K. Singh, A. Voss, F. Resenkaimer, J. Engel, and H. W. Murray. 1999. Oral treatment of visceral leishmaniasis with miltefosine. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 93:589-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sundar, S., A. Makharia, D. K. More, G. Agrawal, A. Voss, C. Fischer, P. Bachmann, and H. W. Murray. 2000. Short-course of oral miltefosine for treatment of visceral leishmaniasis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 31:1110-1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sundar, S., T. K. Jha, C. P. Thakur, J. Engel, H. Sindermann, C. Fischer, K. Junge, A. Bryceson, and J. Bermam. 2002. Oral miltefosine for Indian visceral leishmaniasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 347:1739-1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Uberall, F., H. Oberhuber, K. Maly, J. Zaknum, L. Demuth, and H. H. Grunicke. 1991. Hexadecylphosphocholine inhibitsinositol phosphate formation and protein kinase C activity. Cancer Res. 51:807-812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Virag, L., and C. Szabo. 2002. The therapeutic potential of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors. Pharmacol. Rev. 54:375-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Welburn, S. C., and I. Maudlin. 1997. Control of Trypanosoma brucei brucei infections in tsetse, Glossina morsitans. Med. Vet. Entomol. 11:286-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Welburn, S. C., M. A. Barcinski, and G. T. Williams. 1999. Programmed cell death in Trypanosomatids. Parasitol. Today 13:22-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wieder, T., W. Reutter, C. E. Orfanos, and C. C. Geilen. 1999. Mechanism of action of phospholipid analogs as anticancer compounds. Prog. Lipid Res. 38:249-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zangger, H., J. C. Mottram, and N. Fasel. 2002. Cell death in Leishmania induced by stress and differentiation: programmed cell death or necrosis? Cell Death Differ. 9:1126-1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]