Abstract

Objective

To determine whether patients with severe sepsis or septic shock could benefit from a strict and early goal-directed therapy (EGDT) protocol recommended by Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) Guidelines.

Methods

MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE/OVID and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) were searched between March 1983 and March 2015. Eligible studies evaluated the outcomes of EGDT versus usual care or standard therapy in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. The primary outcomes were mortality within 28 days, 60 days and 90 days. Included studies must report at least one metric of mortality.

Results

5 studies that enrolled 4303 patients with 2144 in the EGDT group and 2159 in the control group were included in this meta-analysis. Overall, there were slight decreases of mortality within 28 days, 60 days and 90 days in the random-effect model in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock receiving EGDT resuscitation. However, none of the differences reached statistical significance (RR=0.86; 95% CI 0.69 to 1.06; p=0.16; p for heterogeneity=0.008, I2=71%; RR=0.94; 95% CI 0.81 to 1.10; p=0.46; p for heterogeneity=0.16, I2=43%; RR=0.98; 95% CI 0.88 to 1.10; p=0.75; p for heterogeneity=0.87, I2=0%, respectively).

Conclusions

The current meta-analysis pooled data from five RCTs and found no survival benefit of EGDT in patients with sepsis. However, the included trials are not sufficiently homogeneous and potential confounding factors in the negative trials (ProCESS, ARISE and ProMISe) might bias the results and diminish the treatment effect of EGDT. Further well-designed studies should eliminate all potential source of bias to determine if EGDT has a mortality benefit.

Keywords: ACCIDENT & EMERGENCY MEDICINE, INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Early goal-directed therapy (EGDT) was first reported by Rivers et al to be of surviving benefit in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Though the EGDT protocol is recommended by Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) Guidelines, its therapeutic value remains controversial. The current meta-analysis pooled data from five randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and found no survival benefit of EGDT in patients with sepsis. However, the included trials are not sufficiently homogeneous and potential confounding factors in the negative trials (ProCESS, ARISE and ProMISe) might bias the results and diminish the treatment effect of EGDT. Further well-designed studies should eliminate all potential source of bias to determine if EGDT has a mortality benefit. Our study focusing specifically on high-quality RCTs would provide a timely guide in the management of severe sepsis or septic shock using EGDT so far.

Our meta-analysis has several limitations. First, the number of studies that met the inclusion criteria for this meta-analysis was relatively small due to the strict implementation of resuscitation goals in the EGDT group according to SSC guidelines. Second, this study did not take all potential confounds into account that may affect the mortality. Lastly, despite the strict inclusion criteria that were applied, a severe degree of heterogeneity cannot be ruled out because of the difference in patient populations, study design and the improved management of the control group over the decade.

Introduction

Modern medicine defines sepsis as a deleterious systemic inflammatory response to infection. Sepsis may progress to severe sepsis and septic shock, both of which are life-threatening health problems affecting millions of people worldwide. Also, sepsis is responsible for huge economic and medical resources consumption.1–3 Besides urgent measures to treat infections with antimicrobial agents and to eliminate the offending microorganisms, haemodynamic and respiratory supports are important managements for sepsis. Early goal-directed therapy (EGDT), first reported by Rivers et al4 in 2001, was used to treat patients with severe sepsis and septic shock, which significantly lowered mortality compared with those who were given standard therapy (30.5% vs 46.5%). Though the EGDT protocol is recommended by Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) Guidelines in 2004 (later updated in 2008 and 2012),1 5 6 it remained to be questioned because of the complexity of resuscitation protocol, potential risks associated with its elements,7 and concerns about the generalisability of Rivers et al’ findings.8 9 Furthermore, three large multicentre randomised clinical trials (RCTs) have recently shown the ineffectiveness of EGDT in the initial management of patients with septic shock, which leads to the debatable efficacy of EGDT.10–12 To better specify the effect of EGDT, we conducted the present meta-analysis focusing on high-quality RCTs only and discussed the effects of a strict EGDT in accordance with SSC Guidelines on mortality.

Methods

Since this is a meta-analysis of previously published studies, ethical approval and patient consent are not required.

Search strategy

This analysis followed the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions statement and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. We searched MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE/OVID, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and the System for Information on Grey Literature between March 1983 and March 2015. Our search was restricted to RCTs published in full-text versions; no language restrictions were applied. Our search strategy was based on three search themes, using (1) ‘sepsis’ or ‘severe sepsis’ or ‘septic shock’ or ‘septicemia’ or ‘septicaemia’ or ‘pyohemia’ or ‘pyaemia’ or ‘pyemia’; and (2) ‘EGDT’ or ‘goal directed therapy’ or ‘early resuscitation’ or ‘protocol based’ or ‘early goal directed strategy’; and (3) ‘randomised controlled trial’ or ‘controlled clinical trial’ or ‘randomised’ or ‘randomly’ or ‘trail’ or ‘groups’ (Electronic search strategies are provided in online supplementary appendix 1). A secondary search was performed by manually searching bibliographies and conferences to identify additional relevant studies.

bmjopen-2015-008330supp_appendix1.pdf (126.8KB, pdf)

Selection criteria

Study inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Design: randomised controlled parallel trials; (2) Population: adult patients (>18 years) with severe sepsis or septic shock. Studies that included patients with sepsis secondary to non-infectious causes were excluded; (3) Intervention: a strict EGDT protocol, defined as a 6 h resuscitation goals in accordance with SSC guidelines including (a) central venous pressure (CVP) 8–12 mm Hg, (b) mean arterial pressure (MAP) ≥65 mm Hg, (c) Urine output (UO) ≥0.5 mL/kg/h, (d) Superior vena cava oxygenation saturation (ScvO2) or mixed venous oxygen saturation (SvO2) ≥70%; (4) Control: usual care or standard therapy; (5) Outcomes: mortality, duration of hospital stay, APACHE II score and use of organ support. Eligible studies must report at least one metric of primary outcome, that is, mortality. Secondary outcomes that focused on duration of hospital stay, APACHE II score and use of organ support (cardiovascular, respiratory and renal system) were also analysed since the data were available in at least three trials.

Data extraction

Three authors independently screened the titles and abstracts of initial search results and extracted data with a standardised data collection form. The following information was extracted from each trial: first author, year of publication, number of patients (EGDT/control), study design, clinical setting, study population, goals of each group (EGDT/control), timing of EGDT and mortality end point. Bin Liu, the senior author, adjudicated any disagreements between the reviewers.

Validity assessment

We assessed methodological quality using the Cochrane Collaboration risk of bias tool that considered seven different domains: adequacy of sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, blinding for outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other potential sources of bias.13

Quality of evidence

Quality of evidence was rated by GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) system14 using GRADE profiler V.3.6 software. The GRADE system classifies the quality of evidence in one of four levels: high, moderate, low and very low. Meta-analysis based on RCTs starts as high-quality evidence, but the confidence may be decreased for the following reasons: study limitation, inconsistency of results, indirectness of evidence, imprecision and reporting bias.

Statistical analysis

For dichotomous data, we estimated the relative risk (RR) with 95% CI to describe the size of treatment effect. For continuous variables, standard mean difference (SMD) was employed.

Homogeneity assumption was tested with I2 statistics. It is calculated as I2=100%×(Q−df)/Q, where Q is Cochran's heterogeneity statistic.15 Heterogeneity was suggested if p≤0.10. I2 values of 0–24.9% indicated no heterogeneity, 25–49.9% mild heterogeneity, 50–74.9% moderate heterogeneity and 75–100% considerable heterogeneity.

Synthesis of the data was performed using the random effects model. For accurate identification, publication bias was only conducted with data sets of at least 10 data. The publication bias was not assessed on account of the limited number of included studies. Sensitivity analyses were carried out for different subgroups according to a variety of differences in study design.

All analyses were performed using Review Manager (RevMan) (Computer program) V.5.2. Significant differences are set at a two-sided p value <0.05.

Results

Literature identification and study characteristics

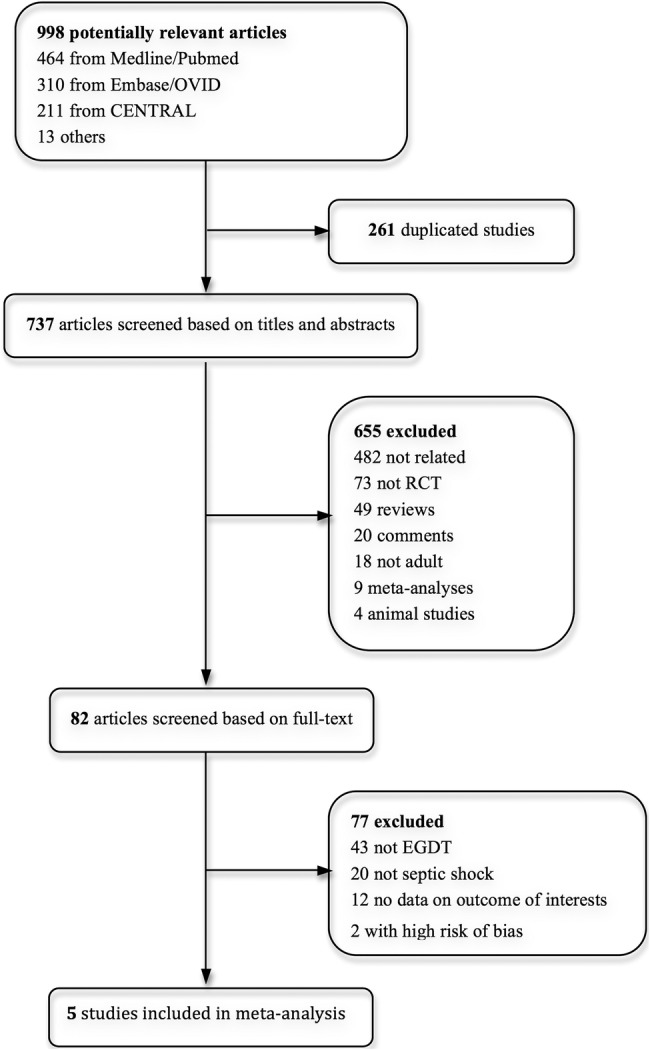

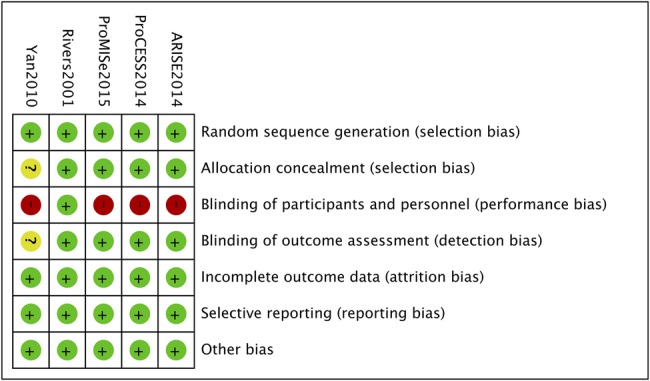

Our search yielded 998 potentially eligible articles (464 from MEDLINE/PubMed, 310 from EMBASE/OVID, 211 from CENTRAL and 13 from other sources). After removing 261 duplicated studies, three independent authors screened 737 articles according to the inclusion criteria. A total of 655 publications were eliminated on the basis of titles or abstracts, and 82 publications were based on full texts. Eventually, five RCTs enrolling 4303 patients, with 2144 in the EGDT group and 2159 in the control group, were included in this meta-analysis (figure 1).4 10–12 16 The characteristics of the eligible trials are described in table 1. Patients enrolled in all these five studies were adults with severe sepsis or septic shock. EGDT within the first 6 h was conducted in all experimental groups of included trials in accordance with SSC guidelines. Usual care was provided by the treating physician in the control group of the ProCESS (Protocolized care for early septic shock) trial, ProMISe (Protocolized Management in Sepsis) trial and ARISE (Australasian resuscitation in sepsis evaluation) trial. In addition to the aforementioned, the first one, namely the ProCESS trial, conducted another control group using standard therapy, where the components were less aggressive than those of EGDT. Meanwhile, River et al and Yan et al treated patients in the control group using standard therapy on the basis of haemodynamic monitoring, which is similar to the EGDT group but lacked ScvO2. All these studies were published in English except the study of Yan et al, which is in Chinese. The Chinese study was conducted in the intensive care unit (ICU), the Rivers et al in the emergency department, while the rest three in the emergency department, ICU or both due to the national limits on length of stay in emergency department. All studies were designed as multicentre trials except that of Rivers et al. All publications reported mortality with more than one end point. The assessment of risk of bias is shown in figure 2. Every study described appropriate sequence generation while the allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessment were unclear in the trial of Yan et al. On account of the specialty of the intervention, none of the five trials were able to perform a double-blinded study except that of Rivers et al, whose study care was blinded to the ICU clinicians while the rest four were unblinded after the first 6 h resuscitation.

Figure 1.

Study selection. RCT, randomised clinical trial; EGDT, early goal-directed therapy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included randomised controlled trials

| Source | Number of patients (EGDT/control) | Design | Clinical setting | Study population | Goals in EGDT group | Goals in control group | Timing of EGDT | Mortality end point |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rivers et al 2001 | 263 (130/133) | P-R-NB-SC | ED | Adult patients with severe sepsis, septic shock or sepsis syndrome | SvO2 ≥70% CVP:8–12 mm Hg MAP:65–90 mm Hg UO ≥0.5 mL/kg/h |

Standard therapy: CVP:8–12 mm Hg MAP:65–90 mm Hg UO ≥0.5 mL/kg/h |

Within the first 6 h | Hospital 28-day 60-day |

| Yan et al 2010 | 303 (157/146) | P-R-NB-MC | ICU | Adult patients with severe sepsis or septic shock | ScvO2 ≥70% CVP:8–12 mm Hg SBP >90 mm Hg MAP ≥65 mm Hg UO ≥0.5 mL/kg/h |

Standard therapy: CVP:8–12 mm Hg SBP >90 mm Hg MAP ≥65 mm Hg UO ≥0.5 mL/kg/h |

Within the first 6 h | ICU 28-day |

| ProCESS 2014 | 895 (439/456) 885 (439/446) |

P-R-NB-MC | ED/ICU | Adult patients with septic shock | ScvO2 ≥70% CVP:8–12 mm Hg MAP:65–90 mm Hg UO ≥0.5 mL/kg/h |

Usual care Standard therapy: SBP ≥100 mm Hg |

Within the first 6 h | 30-day 60-day 90-day |

| ARISE 2014 | 1591 (793/798) | P-R-NB-MC | ED/ICU | Adult patients with septic shock | ScvO2 ≥70% CVP:8–12 mm Hg MAP:65–90 mm Hg UO ≥0.5 mL/kg/h |

Usual care | Within the first 6 h | ICU Hospital 28-day 60-day 90-day |

| ProMISe 2015 | 1251 (625/626) | P-R-MB-MC | ED/ICU | Adult patients with septic shock | ScvO2 ≥70% CVP ≥8 mm Hg MAP >60 mm Hg SBP >90 mm Hg |

Usual care | Within the first 6 h | Hospital discharge 28-day 60-day 90-day |

CVP, central venous pressure; ED, emergency department; EGDT, early goal-directed therapy; ICU, intensive care unit; MAP, mean arterial pressure; MC, multicentre; NB, non-blinded; P, prospective; R, randomised; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SC, single centre; ScvO2, central venous oxygen saturation; SvO2, mixed venous oxygen saturation; UO, urine output.

Figure 2.

The assessment of risk bias.

Primary outcome

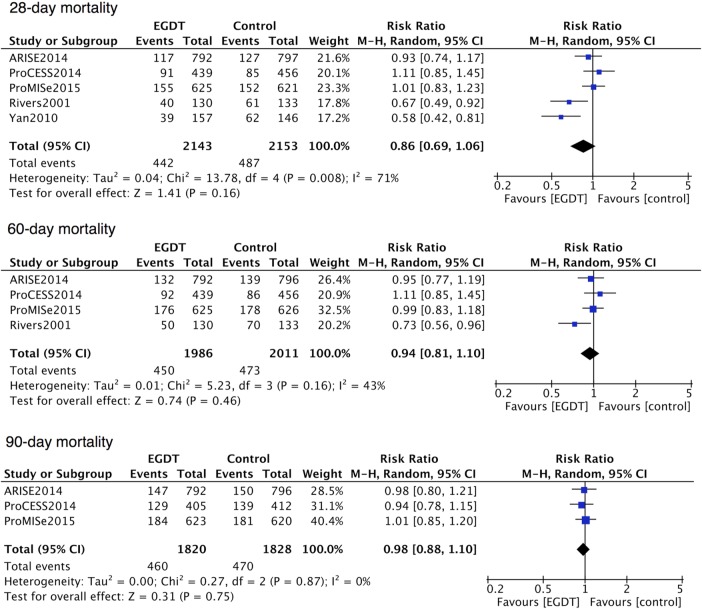

More than one metric of mortality was provided by each eligible trial. Therefore, we conducted mortality analysis on the basis of different end points including 28-day, 60-day and 90-day mortality. Regarding the two control groups in ProCESS, usual care was included in this meta-analysis as a control group, while a substitute of standard therapy did not change the results of any primary outcomes. As shown in figure 3, five studies reported the incidence of death in 28 days except the ProCESS trial, which provided it in 30 days. The 28-day death had occurred in 442 of 2143 patients (20.6%) in the EGDT group and in 487 of 2153 patients (22.62%) in the control group. The 2.0% mortality decrease did not reach statistical significance (RR=0.86; 95% CI 0.69 to 1.06; p=0.16; p for heterogeneity=0.008, I2=71%; figure 3). The 60-day mortality reported in four trials tended to be lower in the EGDT group (22.7% (450 of 1986 patients) vs 23.5% (473 of 2011 patients)), but this did not reach statistical significance (RR=0.94; 95% CI 0.81 to 1.10; p=0.46; p for heterogeneity=0.16, I2=43%; figure 3).4 10–12 Only three of the five studies conducted a follow-up as long as 90 days.10–12 EGDT was associated with decreased 90-day mortality (25.3% (460 of 1820 patients) vs 25.7% (470 of 1828 patients)), although the difference did not reach statistical significance (RR=0.98; 95% CI 0.88 to 1.10; p=0.75; p for heterogeneity=0.87, I2=0%; figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot for the 28-day, 60-day and 90-day mortality. A pooled RR was calculated using the random effects model according to the Mantel-Haenszel (M-H) method. EGDT decreased 28-day, 60-day and 90-day mortality but with no statistical significance. EGDT, early goal-directed therapy.

Secondary outcome

The length of hospital stay4 11 16 (SMD=−0.11; 95% CI −0.31 to 0.10; p=0.31; p for heterogeneity=0.04, I2=69%) and APACHE II score4 11 16 (SMD=−0.29; 95% CI −0.64 to 0.06; p=0.11; p for heterogeneity<0.0001, I2=89%) did not differ significantly between the two groups. Also, receipt of advanced cardiovascular,4 10–12 respiratory4 10–12 or renal10–12 support was equivalent between two groups. (RR=1.08; 95% CI 0.95 to 1.22; p=0.24; p for heterogeneity=0.009, I2=74%, RR=1.04; 95% CI 0.92 to 1.17; p=0.57; p for heterogeneity=0.21, I2=36% and RR=1.03; 95% CI 0.86 to 1.24; p=0.74; p for heterogeneity=0.88, I2=0%, respectively).

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analysis was performed according to a variety of differences in study design (see online supplementary appendix 2). There was no significant decrease in 28-day mortality when excluding the single-centre trial.4 No significant decrease of in-hospital mortality was observed by pooling the death data in patients with septic shock.4 10–12 Both usual-care therapy and standard therapy showed a comparable mortality to EGDT therapy.

bmjopen-2015-008330supp_appendix2.pdf (108.2KB, pdf)

Quality of evidence

GRADE system grades of evidence are very low for 28-day mortality, and moderate for 60-day mortality and 90-day mortality (see online supplementary appendix 3).

bmjopen-2015-008330supp_appendix3.pdf (420.3KB, pdf)

Discussion

The main finding of this meta-analysis is that a strict EGDT protocol conducted in accordance with SSC guidelines showed equivalent survival benefits in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. Meanwhile, the length of hospital stay, APACHE II score and receipts of advanced cardiovascular, respiratory or renal support did not differ significantly between EGDT and other protocols.

Severe sepsis or septic shock is associated with sepsis-induced (persisting) tissue hypoperfusion and disrupted balance of tissue oxygen use.3 An effective initial fluid resuscitation is relied on to prevent the haemodynamic collapse and ongoing of organ failure.1 The prespecified MAP, CVP and ScvO2 goals are recommended in the EGDT protocol to adjust intravenous fluids, vasopressors, inotropes and blood transfusions. CVP and MAP reflect the intravascular volume status and organ perfusion, and could direct the administration of fluid and vasoactive drugs.17 18 Moreover, a goal of maintaining ScvO2≥70% could restore a balance between oxygen delivery and oxygen demand,1 5 6 and normoxia was associated with decreased mortality in patients with sepsis as reported by Pope et al.19 Also, previous meta-analyses of observational studies20–22 or clinical trials23 reported that EGDT or a 6 h sepsis bundle including EGDT significantly reduces mortality in patients with sepsis over the past decade.

The current meta-analysis pooled data from all well-designed RCTs and focused on whether a strict EGDT protocol combining all goals (four indicators, ie, MAP, CVP, UO, ScvO2/SvO2) was necessary to achieve survival benefit in patients with sepsis. While the findings were consistent with the three recent negative trials,10–12 they contradicted those of previous meta-analyses.20–23 Owing to the strict selection criteria in this meta-analysis, only five RCTs were included eventually. Although all of them are all well-designed RCTs, they are not sufficiently homogeneous in terms of patient population and methodology (table 2). First, the study cohorts between these trio of trials and Rivers et al were of different illness severity. The patients of Rivers et al were slightly older than those in the three recent studies. Also, higher rates of chronic coexisting health condition, higher initial serum lactate levels and lower ScvO2 levels were found in the population of Rivers et al’s study, and the APACHE II score and mechanical ventilation rates were relatively lower in the three recent trials.10–12 Besides, the fluid challenge of in Rivers et al was much more than that of the three trials (20 to 30 mL per kilogram of body weight vs 1000 mL), which yields a haemodynamic heterogeneity in these enrolled studies. Second, there are some methodological differences that should be examined before viewing the results. In Rivers et al's study, patient care was blinded to the ICU clinicians while the rest of the trials were unblinded. Corticosteroid was administrated in 8–37% of patients in the trio of trials, but not in that of Rivers et al, which might be associated with improved mortality in the recent three trials, as it was reported that corticosteroid therapy showed a significant shock reversal effect and improved mortality in vasopressor-unresponsive patients with septic shock.24–26 Third, the recent three trials did not compare the causes of death between two groups, especially the rate of death due to sudden cardiovascular collapse. Rivers et al4 assumed that sudden cardiovascular collapse was an important cause of early death and that the EGDT benefits arose from early identification of cardiovascular collapse. Importantly, the mortality in all groups of the recent three trials was much lower than that in Rivers et al's study. The significantly lower mortality may be the result of rapid recognition and management of patients with severe sepsis, and the aggressive intravenous fluids and antibiotics treatment prior to enrolment in these studies. Therefore, on the basis of these biases, it is inappropriate to conclude that EGDT is a useless protocol.

Table 2.

The source of bias in terms of patient population and methodology of included trials

| Rivers et al | ProCESS, ARISE and ProMISe | |

|---|---|---|

| Illness severity heterogeneity* | ||

| Fluid challenge before enrolment | 20 to 30 mL/kg | 1000 mL |

| Blood lactate levels at baseline, mmol/L | 6.9 | 4.2–5.1 |

| APACHE II score at baseline | 20.4 | 15.8–20.7 |

| ScvO2, at baseline, % | 49.2 | NR |

| ScvO2, 0–6 h, % | 66 | 75.9† |

| Mechanical ventilation 0–6 h, % | 53.8 | 19.0–22.4 |

| 28-day mortality | 49.2% | 15.9–24.5% |

| Methodological differences | ||

| CVC, %‡ | 100 | 50.9–61.9 |

| Corticosteroid use | None | 8–37% |

| Antibiotics treatment | After enrolment | Before enrolment |

| Treatment in control group | Well-defined | Vague |

| Blinding | Double blinded | Unblinded to the ICU clinicians |

| Time of conduction | 1997–2000 | 2008–2014 (EGDT recommendation in SSC Guidelines and the sepsis six) |

*The data in control groups.

†The data in the EGDT group in ARISE.

‡The central venous catheterisation in control group: standard therapy in Rivers et al and usual care in the trio of trials.

CVC, central venous catheterisation; EGDT, early goal-directed therapy; NR, not reported; ScvO2, central venous oxygen saturation; SSC, Surviving Sepsis Campaign.

It is worth mentioning that the treatments made by the treating clinical team in the usual care group were not well defined in the trio of trials, and the control groups and treatment groups were not received distinctly different treatments in a blinded fashion, which may cause a crossover of treatment between the two groups. Also, it is rational to assume that the usual care has changed dramatically due to the influence of Rivers et al's trial advocating EGDT. It is evidenced by the progressive decrease in sepsis mortality over the past decade.27 Also, the trio of trials were conducted with a duration ranging between 4 and 8 years, during which period the SSC Guidelines recommending the EGDT protocol updated in 2008 (later updated in 2012) and the UK used a sepsis six protocol before and during the ProMISE trial conduction.28 29 What is more important is that even in the usual care group, the central venous catheterisation (a fundamental component of the EGDT) rates were over 50%, and MAP and CVP targets were achieved within the initial resuscitation in the three recent trials.10–12 Hence, the crossover of treatment between the two groups and rapid and effective resuscitation in management of patients with sepsis with modified clinician behaviours in the usual care group might render the effect of EGDT underpowered.30 31

Owing to a lack of high-level evidence of validation of EGDT replicating Rivers et al's trial, the trio of trials designed multicentre RCTs. However, potential confounding of recruiting milder patients, more aggressive antibiotic therapy and crossover of treatments between the control groups and the EGDT groups due to unblinding might bias the results and diminish the treatment effect of EGDT. Further well-designed studies should eliminate all potential source of bias mentioned above to determine if EGDT has a mortality benefit. Indeed, the results of current meta-analysis and recent trials did not undermine the effect of EGDT; instead, they urged us to find a more practical and cost-saving approach that could yield similar survival outcomes. Lin et al32 employed a modified EGDT protocol without the monitoring of ScvO2 and found a decrease in mortality. A clinical trial confirmed that the value of lactate clearance is equivalent to ScvO2 using the EGDT algorithm.33 Moreover, some new researches are on the way, aiming to use a minimally invasive protocol utilising oesophageal Doppler monitoring (EDM) to replace continuous ScvO2 (NCT00535821).

Our meta-analysis has several limitations. First, the number of studies that met the inclusion criteria for this meta-analysis was relatively small due to the strict implementation of resuscitation goals in the EGDT group according to SSC guidelines. Consequently, subanalyses that could be conducted to compare EGDT with different control groups were limited. Second, end points of the mortality in each trial ranged from 28 days to 90 days, which may have a potential effect on overall mortality. However, we conducted mortality analysis according to different end points including mortality in 28 days, 60 days and 90 days, and the results were consistent. Third, this study did not take all potential confounds (eg, age, chronic coexisting health conditions, initial serum lactate levels as well as APACHE II score) into account, which may affect the mortality. Lastly, despite the strict inclusion criteria that were applied, a severe degree of heterogeneity cannot be ruled out because of the difference in patient populations, study design and the improved management of the control group over the decade.

Conclusions

The current meta-analysis pooled data from five RCTs and found no survival benefit of EGDT in patients with sepsis. However, the included trials are not sufficiently homogeneous and potential confounding factors in the negative trials (ProCESS, ARISE and ProMISe) might bias the results and diminish the treatment effect of EGDT. Further well-designed studies should eliminate all potential sources of bias to determine if EGDT has a mortality benefit.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the authors of the primary studies.

Footnotes

Contributors: HY, DC and SW contributed equally to this article. BL provided the original idea of this meta-analysis, supervised the data analysis and revised the article. HY, DC and SW participated in the study selection, data collection, statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. SW was involved in the Introduction part; DC in the Methods part; and HY in the Results part. All the authors contributed to the discussion part and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the research grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number 30972862) and the Sichuan Province Science and Technology Supporting Programme (Grant 2012FZ0121).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A et al. . Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med 2013;41:580–637. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827e83af [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lagu T, Rothberg MB, Shieh MS et al. . Hospitalizations, costs, and outcomes of severe sepsis in the United States 2003 to 2007. Crit Care Med 2012;40:754–61. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232db65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angus DC, van der Poll T. Severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 2013;369:2063 10.1056/NEJMc1312359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S et al. . Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1368–77. 10.1056/NEJMoa010307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dellinger RP, Carlet JM, Masur H et al. . Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Intensive Care Med 2004;30:536–55. 10.1007/s00134-004-2210-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM et al. . Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med 2008;36:296–327. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000298158.12101.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapman M, Gattas D, Suntharalingam G. Why is early goal-directed therapy successful—is it the technology. Crit Care 2005;9:307–8. 10.1186/cc3726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peake S, Webb S, Delaney A. Early goal-directed therapy of septic shock: we honestly remain skeptical. Crit Care Med 2007;35:994–5; author reply 995 10.1097/01.CCM.0000257481.37623.3B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ho BC, Bellomo R, McGain F et al. . The incidence and outcome of septic shock patients in the absence of early-goal directed therapy. Crit Care 2006;10:R80 10.1186/cc4918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mouncey PR, Osborn TM, Power GS et al. . Trial of early, goal-directed resuscitation for septic shock. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1301–11. 10.1056/NEJMoa1500896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yealy DM, Kellum JA, Huang DT et al. . A randomized trial of protocol-based care for early septic shock. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1683–93. 10.1056/NEJMoa1401602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peake SL, Delaney A, Bailey M et al. . Goal-directed resuscitation for patients with early septic shock. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1496–506. 10.1056/NEJMoa1404380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC et al. , Cochrane Bias Methods Group; Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE et al. . GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–6. 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ et al. . Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Early Goal-Directed Therapy Collaborative Group of Zhejiang Province. [The effect of early goal-directed therapy on treatment of critical patients with severe sepsis/septic shock: a multi-center, prospective, randomized, controlled study]. Zhongguo Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue 2010;22:331–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rivers EP, Katranji M, Jaehne KA et al. . Early interventions in severe sepsis and septic shock: a review of the evidence one decade later. Minerva Anestesiol 2012;78:712–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tuchschmidt J, Fried J, Astiz M et al. . Elevation of cardiac output and oxygen delivery improves outcome in septic shock. Chest 1992;102:216–20. 10.1378/chest.102.1.216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pope JV, Jones AE, Gaieski DF et al. , Emergency Medicine Shock Research Network (EMShockNet) Investigators. Multicenter study of central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO(2)) as a predictor of mortality in patients with sepsis. Ann Emerg Med 2010;55:40–46.e1. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wira CR, Dodge K, Sather J et al. . Meta-analysis of protocolized goal-directed hemodynamic optimization for the management of severe sepsis and septic shock in the Emergency Department. West J Emerg Med 2014;15:51–9. 10.5811/westjem.2013.7.6828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chamberlain DJ, Willis EM, Bersten AB. The severe sepsis bundles as processes of care: a meta-analysis. Aust Crit Care 2011;24:229–43. 10.1016/j.aucc.2011.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barochia AV, Cui X, Vitberg D et al. . Bundled care for septic shock: an analysis of clinical trials. Crit Care Med 2010;38:668–78. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cb0ddf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gu WJ, Wang F, Bakker J et al. . The effect of goal-directed therapy on mortality in patients with sepsis—earlier is better: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care 2014;18:570 10.1186/s13054-014-0570-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Annane D, Sebille V, Charpentier C et al. . Effect of treatment with low doses of hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone on mortality in patients with septic shock. JAMA 2002;288:862–71. 10.1001/jama.288.7.862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Briegel J, Forst H, Haller M et al. . Stress doses of hydrocortisone reverse hyperdynamic septic shock: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, single-center study. Crit Care Med 1999;27:723–32. 10.1097/00003246-199904000-00025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bollaert PE, Charpentier C, Levy B et al. . Reversal of late septic shock with supraphysiologic doses of hydrocortisone. Crit Care Med 1998;26:645–50. 10.1097/00003246-199804000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaukonen KM, Bailey M, Suzuki S et al. . Mortality related to severe sepsis and septic shock among critically ill patients in Australia and New Zealand, 2000–2012. JAMA 2014; 311:1308–16. 10.1001/jama.2014.2637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daniels R, Nutbeam T, McNamara G et al. . The sepsis six and the severe sepsis resuscitation bundle: a prospective observational cohort study. Emerg Med J 2011;28:507–12. 10.1136/emj.2010.095067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robson WP, Daniel R. The Sepsis Six: helping patients to survive sepsis. Br J Nurs 2008;17:16–21. 10.12968/bjon.2008.17.Sup1.28145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russell JA, Vincent JL. The new trials of early goal-directed resuscitation: three-part harmony or disharmony? Intensive Care Med 2013;39:1867–9. 10.1007/s00134-013-3068-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gattinoni L, Giomarelli P. Acquiring knowledge in intensive care: merits and pitfalls of randomized controlled trials. Intensive Care Med 2015;41:1460–4. 10.1007/s00134-015-3837-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin SM, Huang CD, Lin HC et al. . A modified goal-directed protocol improves clinical outcomes in intensive care unit patients with septic shock: a randomized controlled trial. Shock 2006;26:551–7. 10.1097/01.shk.0000232271.09440.8f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones AE, Shapiro NI, Trzeciak S et al. . Lactate clearance vs central venous oxygen saturation as goals of early sepsis therapy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2010;303:739–46. 10.1001/jama.2010.158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2015-008330supp_appendix1.pdf (126.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2015-008330supp_appendix2.pdf (108.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2015-008330supp_appendix3.pdf (420.3KB, pdf)