Abstract

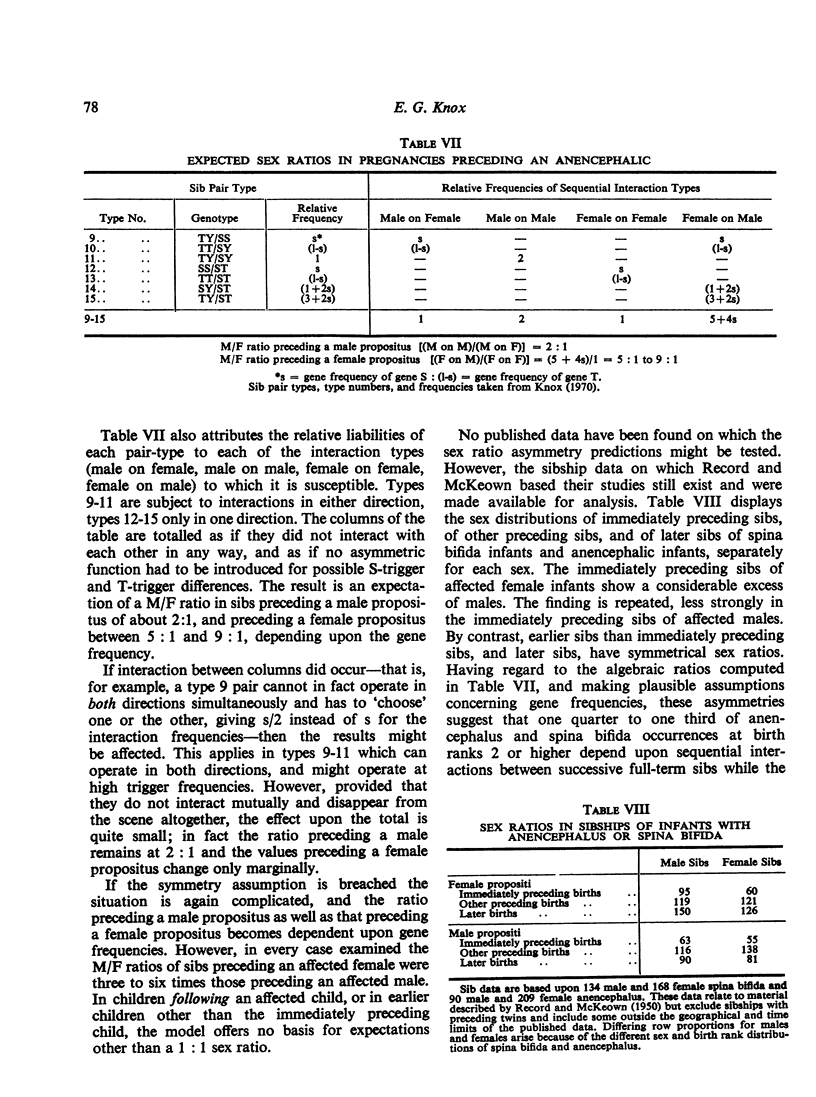

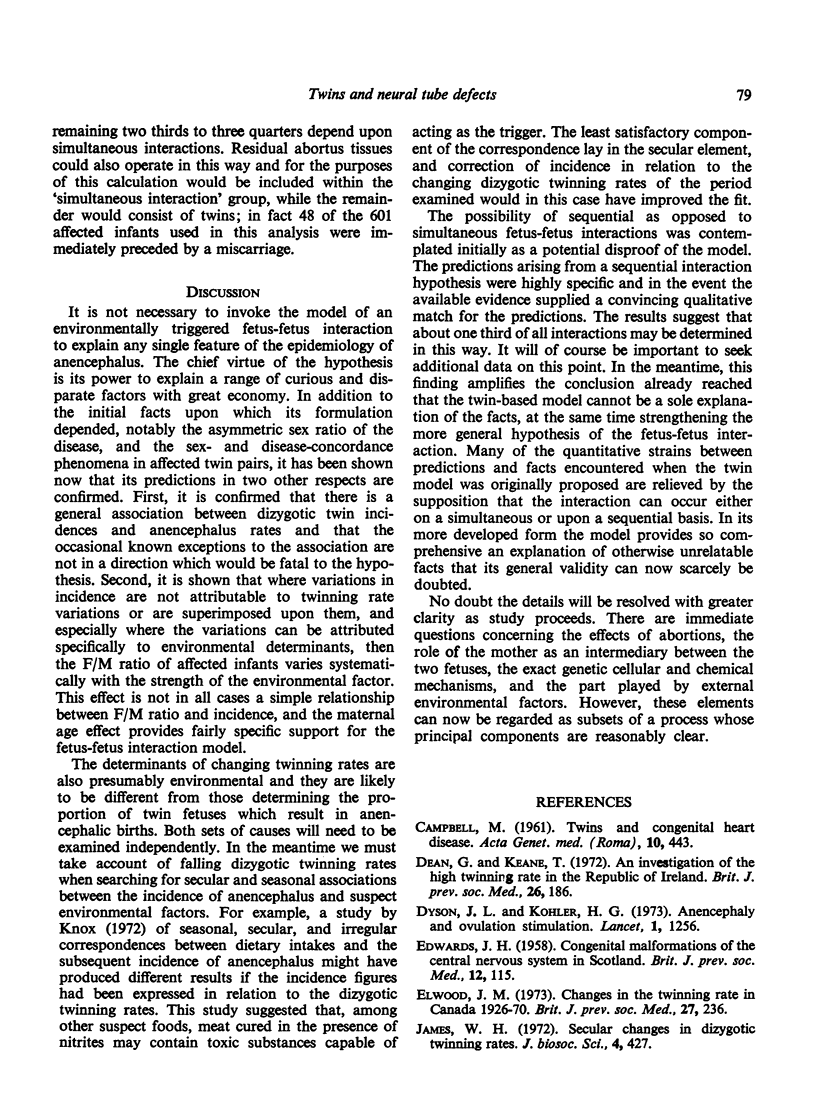

The hypothesis that anencephalus stems from fetus-fetus interactions in dizygotic twin pairs is examined by comparing the epidemiological predictions of the hypothesis with available observations. The hypothesis itself was based upon the disease-discordance and sex-concordance characteristics of twin pairs affected with anencephalus, and upon the sex ratio of the disease itself. The testable predictions of the hypothesis are (a) that variations in the incidence of anencephalus should be related to variations in dizygotic twinning rates, and particularly that dizygotic twinning rates will set upper limits to the incidence of anencephalus, and (b) that the F/M ratio in anencephalic infants will be high in circumstances of high incidence, and specifically when the incidence is high in relation to the dizygotic twinning rate. Examples from international comparisons, secular changes, social class gradients, and variations according to maternal age confirm a consistent correspondence between observations and these predictions. In addition, the possibility was tested that some fetus-fetus interactions might be based upon sequential rather than simultaneous pairs of fetuses. This model predicted asymmetries of sex ratio in sibs immediately preceding propositi, with differences according to the sex of the affected child, and the predicted findings were confirmed. The fetus-fetus interaction hypothesis is therefore extended in the terms that about one third of occurrences are determined in a sequential manner.

The success of the extended fetus-fetus interaction model in explaining a large number of otherwise unrelatable findings confirms its validity.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- CAMPBELL M. Twins and congenital heart disease. Acta Genet Med Gemellol (Roma) 1961 Oct;10:443–456. doi: 10.1017/s1120962300016772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean G., Keane T. An investigation of the high twinning rate in the Republic of Ireland. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1972 Aug;26(3):186–192. doi: 10.1136/jech.26.3.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson J. L., Kohler H. G. Anencephaly and ovulation stimulation. Lancet. 1973 Jun 2;1(7814):1256–1257. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)90576-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EDWARDS J. H. Congenital malformations of the central nervous system in Scotland. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1958 Jul;12(3):115–130. doi: 10.1136/jech.12.3.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwood J. M. Changes in the twinning rate in Canada 1926-70. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1973 Nov;27(4):236–241. doi: 10.1136/jech.27.4.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James W. H. Secular changes in dizygotic twinning rates. J Biosoc Sci. 1972 Oct;4(4):427–434. doi: 10.1017/s0021932000008750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KNOX G., MORLEY D. Twinning in Yoruba women. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp. 1960 Dec;67:981–984. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1960.tb09255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox E. G. Obstetric determinants of rhesus sensitisation. Lancet. 1968 Mar 2;1(7540):433–436. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(68)92776-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leck I., Record R. G. Seasonal incidence of anencephalus. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1966 Apr;20(2):67–75. doi: 10.1136/jech.20.2.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEEL J. V. A study of major congenital defects in Japanese infants. Am J Hum Genet. 1958 Dec;10(4):398–445. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RECORD R. G., McKEOWN T. Congenital malformations of the central nervous system; maternal reproductive history and familial incidence. Br J Soc Med. 1950 Jan;4(1):26–50. doi: 10.1136/jech.4.1.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STALLY BRASS F. C. Anencephaly in uniovular twins. Report of a case. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1960 Jul;14:136–138. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler B. Anencephaly and ovulation stimulation. Lancet. 1973 Aug 18;2(7825):379–379. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)93222-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitelaw M. J., Kalman C. F., Grams L. R. The significance of the high ovulation rate versus the low pregnancy rate with Clomid. A review of 203 private anovulatory patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1970 Jul 15;107(6):865–877. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)34038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]