Abstract

Background and objectives

Lowering the dialysate temperature may improve outcomes for patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis. We reviewed the reported benefits and harms of lower temperature dialysis.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We searched the Cochrane Central Register, OVID MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Pubmed until April 15, 2015. We reviewed the reference lists of relevant reviews, registered trials, and relevant conference proceedings. We included all randomized, controlled trials that evaluated the effect of reduced temperature dialysis versus standard temperature dialysis in adult patients receiving chronic hemodialysis. We followed the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach to assess confidence in the estimates of effect (i.e., the quality of evidence). We conducted meta-analyses using random effects models.

Results

Twenty-six trials were included, consisting of a total of 484 patients. Compared with standard temperature dialysis, reduced temperature dialysis significantly reduced the rate of intradialytic hypotension by 70% (95% confidence interval, 49% to 89%) and significantly increased intradialytic mean arterial pressure by 12 mmHg (95% confidence interval, 8 to 16 mmHg). Symptoms of discomfort occurred 2.95 (95% confidence interval, 0.88 to 9.82) times more often with reduced temperature compared with standard temperature dialysis. The effect on dialysis adequacy was not significantly different, with a Kt/V mean difference of −0.05 (95% confidence interval, −0.09 to 0.01). Small sample sizes, loss to follow-up, and a lack of appropriate blinding in some trials reduced confidence in the estimates of effect. None of the trials reported long-term outcomes.

Conclusions

In patients receiving chronic hemodialysis, reduced temperature dialysis may reduce the rate of intradialytic hypotension and increase intradialytic mean arterial pressure. High–quality, large, multicenter, randomized trials are needed to determine whether reduced temperature dialysis affects patient mortality and major adverse cardiovascular events.

Keywords: dialysis, hemodialysis, end stage renal disease, chronic hemodialysis, cold temperature, dialysis solutions, follow-up studies, humans, hypotension, renal dialysis

Introduction

Approximately 2 million patients worldwide receive life–sustaining chronic hemodialysis treatments (1). Intradialytic hypotension occurs in ≤30% of hemodialysis treatments and is associated with substantial long–term mortality (2–4). Maggiore et al. (5) proposed cool dialysis to prevent intradialytic hypotension by increasing peripheral vascular resistance, improving cardiac output, and altering the levels of vasoactive peptides. Nephrologists, however, remain cautious about using this modality of hemodialysis because of limited evidence about its long-term effects and the assumed disadvantages. These disadvantages include the discomfort that patients may experience in association with cool dialysis and the concern that it may interfere with achieving adequate dialysis.

In 2006, Selby and McIntyre (6) conducted a systematic review to assess the effects of lowering dialysate temperature. The review was restricted to English language articles, and Selby and McIntyre (6) were unable to report the effects of lowering dialysate temperature on long–term patient–important outcomes because of lack of data. Since 2006, more trials have been published on this topic (7,8). We conducted this systematic review to evaluate the effect of cool dialysis compared with standard temperature dialysis on patient-important outcomes in adults undergoing maintenance chronic hemodialysis.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources and Searches

We conducted this systematic review in accordance with a prespecified registered protocol available at http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO (registration no. CRD42011001104). We reported the results according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (9).

We performed an electronic search of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (until April of 2015), OVID MEDLINE (from 1946 to April of 2015), EMBASE (from 1947 to April of 2015), and Pubmed (from 1951 to April of 2015). A methodologic filter was applied to limit retrieval to clinical trials and the human population (detailed search strategy is provided in Supplemental Appendix 1) (10). We reviewed the reference lists of relevant articles and reviews as well as trials registered on the ClinicalTrials.gov website. We searched for conference proceedings from 2007 to 2014 using the Web of Science and abstracts presented at recent annual meetings of the American Society of Nephrology, the Canadian Society of Nephrology, the National Kidney Foundation, the European Renal Association-European Dialysis and Transplant Association, and the International Society of Nephrology.

Study Selection

We used the following eligibility criteria.

Studies.

We included all randomized, controlled trials from January of 1946 to April of 2015. This included crossover, parallel arm, and cluster trials.

Participants.

We included all adult patients (aged >18 years old) who received chronic hemodialysis in either an inpatient or outpatient setting, regardless of BP at baseline.

Intervention.

We compared standard temperature dialysis with any method of cool dialysis. Different methods of cool dialysis include fixed reduction in dialysate temperature programmed patient cooling, isothermic dialysis, and negative energy balance using a biofeedback temperature monitoring device. We used the trials’ definitions of standard and cool dialysis temperature. We only included bicarbonate-based dialysis and excluded acetate-based dialysis, because acetate-based dialysis is not used in common practice anymore. We did not include hemodiafiltration or acetate-free biofiltration in this review.

Outcomes Measures.

We abstracted information on the following outcomes: mortality, hospitalization, quality of life (QOL), intradialytic hypotension, BP, cardiovascular events, access failure, system clotting, bleeding, dialysis adequacy, and symptoms, including discomfort caused by cold sensation and cramping. We did not assess the effect of cool dialysis on energy transfer, vasoactive peptides, or radiologic and diagnostic tests changes (e.g., changes in magnetic resonance, echocardiogram, or computed tomography).

Language.

We included trials published in any language.

Publication Status.

We reviewed all published and unpublished studies. Abstracts with relevant information were also reviewed.

Two investigators independently screened the search results for articles on the basis of the title or the title and abstract. The full-text article was retrieved for any citation considered potentially relevant by any investigator. Each of the investigators then independently assessed the eligibility of each article by using a pilot–tested, standardized form with written instructions. Any disagreement was resolved by consensus. If at least one of the characteristics was not met, the article was excluded. We used Cohen κ-value to measure agreement beyond chance between reviewers (11).

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

We extracted data using a pilot-tested and standardized form. Two investigators independently extracted all relevant data from included trials. Results of data extraction were then compared, and any discrepancy was resolved by discussion. When the same results were presented in more than one publication, we included the publication with the most complete results. If results were incomplete or unclear, we contacted study authors for additional information.

We collected the following information from each trial: trial characteristics (author name, year of publication, country, language, number of centers, number of countries, and inclusion and exclusion criteria), patient characteristics (number, patients completing follow-up, age, comorbidities, and baseline BP), intervention and comparison characteristics (type of dialysate cooling, duration of intervention, and temperature of dialysate in each group), cointerventions (concomitant BP medication use), and outcomes. Also, we collected information about funding sources, conflict of interest statements, consent, and ethics approval.

Two reviewers independently assessed the risk of bias of the selected trials. To assess any risk of bias, different domains were considered for each outcome. These domains were adequate random sequence generation, concealment of allocation, adherence to the intention-to-treat principle, stopping early for benefit, proportion of patients lost to follow-up, selective reporting of outcomes, freedom from other biases, and blinding of patients, investigators, dialysis nurses, clinical outcome assessors, data collectors, and data analyzers.

To assess the confidence in the estimates of effect (i.e., quality of evidence) across studies, we followed the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation GRADE approach (12) by making judgments about the risk of bias, publication bias, indirectness, imprecision, and inconsistency among different trials. To assess publication bias, we used the funnel plot and Egger linear regression test (13).

Data Synthesis and Analyses

The intervention effect estimates for each outcome were combined quantitatively (pooled) from different trials when appropriate using RevMan, version 5. When quantitative synthesis of the data was not appropriate, the results were summarized qualitatively. The Breslow–Day test was used to measure the percentage of total variation across studies caused by heterogeneity (I2). Trial data were considered worthy of exploration of heterogeneity when the I2 statistic was >50%. Attempts were also made to explain heterogeneity on the basis of the patient clinical characteristics and interventions of the trials included.

Rates were expressed as rate ratios and compared using generic inverse variance. Continuous data were expressed as mean differences. Overall results were pooled using a random effects model (14,15).

Sensitivity analyses to assess robustness of results and subgroup analyses to determine whether the summary effects vary in relation to clinical characteristics of the population in the included trials were prespecified. The treatment effects were examined according to risk of bias. Two subgroup analyses were undertaken. The first compared the effect of fixed temperature reduction compared with biofeedback devices on different outcomes. The second compared the effect of cooling dialysate in patients with stable and unstable BPs at baseline.

Results

Study Selection

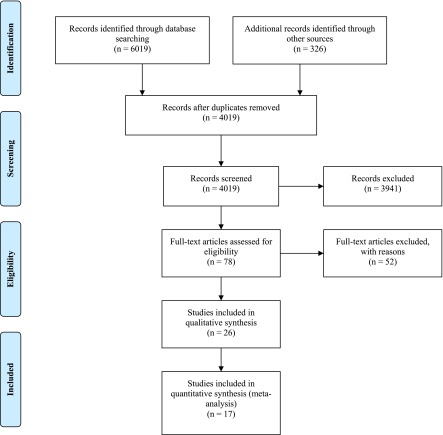

Study selection is presented in Figure 1; 4019 citations were screened, and a total of 26 trials were included in the review. The chance-corrected agreement for full-text eligibility was good (κ=0.87). Details about the excluded studies are presented in Supplemental Appendix 2. The most important reasons for exclusion included the use of acetate dialysis, duplicate data, and a lack of primary data.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the article selection process based on preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Study Characteristics

Table 1 presents the details about characteristics of included trials (16–40) (B. Jo et al., unpublished data). All 26 trials selected for the final review were crossover, randomized trials published in English. Nineteen trials had no dropouts. The other seven trials had patient dropout of varying degrees (8%–42%) (16–22). One trial was an international multicenter study (20) (27 centers and nine countries), and the rest were conducted in single centers.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included trials

| Study Country | Methodsa | Participants | Intervention | Control | Outcomes | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Zealand (25) | Crossover design; allocation concealment: NR; sequence generation: NR; blinding: no; dropouts: 0 | n=10; BP: five stable, five unstable; age 59.8±5.5 yr | Fixed temperature 35°C; duration: three sessions | Fixed temperature 36°C; duration: three sessions | Dialysis adequacy; BP; body temperature; symptoms; IDH | Circulation or vascular access problems, recent surgery, AKI, severe anemia, CAD |

| The Netherlands (16) | Crossover design; allocation concealment: NR; sequence generation: NR; blinding: NR; dropouts: 1 | n=12 (eight men, four women); BP: all stable; age 69±6 yr | Fixed temperature 35.5°C; duration: one session | Fixed temperature 36.5°C; duration: one session | BP; body temperature; hemodynamics | CHF (NYHA≥3), severe CAD, DM |

| The Netherlands (26) | Crossover design; allocation concealment: NR; sequence generation: NR; blinding: NR; dropouts: 0 | n=12 (seven men, five women); BP: all stable; age 64.7±2.6 yr | BTM (mean dialysate temperature 35.2°C); duration: one session | Fixed temperature 37.5°C; duration: one session | BP; body temperature; symptoms; IDH | CHF (EF≤25%), DM, CAD, NYHA≥3, using nitrates |

| United Kingdom (17) | Crossover design; allocation concealment: NR; sequence generation: NR; blinding: patients, not staff; dropouts: 1 | n=10 (six men, four women); BP: not stable; age 67±2 yr | Fixed temperature 35°C; duration: one session | Fixed temperature 37°C; duration: one session | Dialysis adequacy; BP; body temperature; IDH; hemodynamics | Central venous catheter for access, severe CHF (NYHA≥3), heart transplant |

| United States (18) | Crossover design; allocation concealment: NR; sequence generation: NR; blinding: NR; dropouts: 8 | n=19 (six men, five women); BP: not stable; age 67.5 yr | Fixed temperature 35.5°C; duration: nine sessions | Fixed temperature 37°C; duration: nine sessions | Dialysis adequacy; BP; symptoms; IDH | Symptoms not reported |

| United States (23) | Crossover design; allocation concealment: NR; sequence generation: NR; blinding: staff, not patients; dropouts: 0 | n=10 (three men, seven women); BP: not stable; age 61.1±12.5 yr | Fixed temperature 35°C; duration: three sessions | Standard fixed temperature; duration: three sessions | Dialysis adequacy; BP; symptoms; IDH | Uncontrolled HTN, DM, unstable angina, noncompliance, frequent hospitalizations, variable weight gain |

| Canada (19) | Crossover design; allocation concealment: NR; sequence generation: block center randomization; blinding: patients and nurses; dropouts: yes but no clear details; some patients studied more than once | n=128; BP: all stable; age 58 yr | Fixed temperature 35°C; duration: 13 sessions on average | Fixed temperature 37°C; duration: seven sessions on average | IDH | Pre-HD body temperature 36°C–36.5°C |

| Sweden (27) | Crossover design; allocation concealment: NR; sequence generation: NR; blinding: NR; dropouts: 0 | n=10 (seven men, three women); BP: all stable; age 63 yr; time on HD: 3–49 mo | Fixed temperature 34.5°C; duration: one session | Fixed temperature 38.5°C; duration: one session | BP; body temperature | Not reported |

| United States (28) | Crossover design; allocation concealment: NR; sequence generation: NR; blinding: NR; dropouts: 0 | n=13 (eight men, four women); BP: not stable; age 67.6±13.8 yr | Fixed temperature 35.5°C; duration: one session | Fixed temperature 37°C; duration: one session | BP; hemodynamics; complications | Central venous catheter for access, vascular access dysfunction, active medical condition |

| Japan (29) | Crossover design; allocation concealment: NR; sequence generation: NR; blinding: NR; dropouts: 0 | n=7 (one men, six women); BP: not stable; age 53–75 yr | Fixed temperature 35.5°C; duration: one session | Fixed temperature 37°C; duration: one session | BP; symptoms | Not reported |

| United States (30) | Crossover design; allocation concealment: NR; sequence generation: NR; blinding: patients and investigators; dropouts: 0 | n=12 (12 men); BP: not stable; age 62.5±3.6 yr; time on HD: 35.4±6.2 mo | Fixed temperature 35°C; duration: one session | Fixed temperature 37°C; duration: one session | BP; IDH; hemodynamics | Not reported |

| United States (31) | Crossover design; allocation concealment: NR; sequence generation: NR; blinding: NR; dropouts: 0 | n=15; BP: not reported | BTM negative energy (dialysate temperature 35.7°C); duration: one session | BTM thermoneutral (dialysate temperature 37.1°C); duration: one session | Dialysis adequacy; BP; body temperature; IDH; hemodynamics; symptoms | Not reported |

| Japan (32) | Crossover design; allocation concealment: NR; sequence generation: NR; blinding: NR; dropouts: 0 | n=9; BP: not reported; age 43.5 yr | Fixed temperature 34°C; duration: one session | Fixed temperature 37°C; duration: one session | BP; hemodynamics | Not reported |

| Germany (33) | Crossover design; allocation concealment: NR; sequence generation: NR; blinding: NR; dropouts: 0 | n=9; BP: not reported | BTM (program cooling by 0.2°C); duration: one session | Fixed temperature 37°C; duration: one session | Dialysis adequacy; BP; body temperature; hemodynamics | Not reported |

| United States (34) | Crossover design; allocation concealment: NR; sequence generation: NR; blinding: patients and providers; dropouts: 0 | n=6; BP: not reported; age 55±11 yr | Fixed temperature 35°C; duration: one session | Fixed temperature 37°C; duration: one session | BP; body temperature | Not reported |

| Nine countries (20) | Crossover design (27 centers); allocation concealment: NR; sequence generation: central; blinding: no; dropouts: 21 | n=95; BP: not stable; age 66±12 yr | BTM isothermic; duration: 12 sessions on average | BTM thermoneutral; duration: 12 sessions on average | Dialysis adequacy; BP; symptoms; IDH; complications | Recent surgery, severe anemia, vascular access problems, malignancy, ascitis, CHF (NYHA class 4), use of any antihypertensive medications |

| United States (41) | Crossover design; allocation concealment: NR; sequence generation: NR; blinding: single blinded; dropouts: 0 | n=7 (three men, four women); BP: all stable; age 46.1±4.2 yr | Fixed temperature 35°C; duration: one session | Fixed temperature 37°C; duration: one session | BP; body temperature; sleep measures | Chronic infection, CHF, chronic lung disease, arthritis, organic brain disease, drug/alcohol abuse or past psychiatric disorders requiring treatment; taking β-adrenergic blockers, clonidine, methyldopa, antidepressants, sedatives, activating agents or pain medication, NSAIDs, and acetaminophen |

| Australia (35) | Crossover design; allocation concealment: NR; sequence generation: NR; blinding: NR; dropouts: 0 | n=8 (four men, four women); BP: not reported; age 54–79 yr | Fixed temperature 35.3°C±0.2°C; duration: one session | Fixed temperature 37.3°C±0.3°C; duration: one session | BP; body temperature | Not reported |

| United Kingdom (21) | Crossover design; allocation concealment: NR; sequence generation: NR; blinding: patients, not staff; dropouts: 1 | n=10 (four men, six women); BP: not reported; age 65±11 yr | Fixed temperature 35°C; duration: one session | Fixed temperature 37°C; duration: one session | Dialysis adequacy; BP; body temperature; symptoms; IDH; QOL; hemodynamics | CHF (greater than NYHA class 3), cardiac transplant if it was not possible to obtain an echocardiogram |

| The Netherlands (36) | Crossover design; allocation concealment: NR; sequence generation: NR; blinding: NR; dropouts: 0 | n=9 (four men, five women); BP: three of nine not stable; age 68.7±10.4 yr | Fixed temperature 35.5°C; duration: one session | Fixed temperature 37°C; duration: one session | BP; body temperature; IDH | Not reported |

| The Netherlands (37) | Crossover design; allocation concealment: NR; sequence generation: NR; blinding: NR; dropouts: 0 | n=15 (seven men, eight women); BP: not reported; age 55 yr | Fixed temperature 35.5°C; duration: one session (1 h) | Fixed temperature 37.5°C; duration: one session (1 h) | BP; body temperature; symptoms; hemodynamics | Severe CAD, DM, CHF (LVEF<30%) |

| The Netherlands (38) | Crossover design; allocation concealment: NR; sequence generation: NR; blinding: NR; dropouts: 0 | n=12 (seven men, five women); BP: all stable; age 56.67±15.95 yr | Fixed temperature 35.5°C; duration: one session | Fixed temperature 37.5°C; duration: one session | BP; body temperature | Not reported |

| The Netherlands (39) | Crossover design; allocation concealment: NR; sequence generation: NR; blinding: NR; dropouts: 0 | n=13; BP: all stable | BTM isothermic; duration: one session | BTM thermoneutral; duration: one session | Body temperature | Frequent IDH, severe CAD severe CHF, central venous catheter for access |

| The Netherlands (22) | Crossover design; allocation concealment: NR; sequence generation: NR; blinding: NR; dropouts: 3 | n=17; (eight men, six women); BP: not stable; age 60.9±10.4 yr | BTM isothermic; BTM cooling 0.5°C below body temperature; duration: 1.5 sessions on average | BTM thermoneutral; duration: 1.5 sessions on average | BP; body temperature; symptoms; hemodynamics; IDH | Age >85 yr, not able to read and understand English, using central venous catheter for access |

| China (24) | Crossover design; allocation concealment: NR; sequence generation: NR; blinding: patients; dropouts: 0 | n=9; BP: not reported; age 63±2.2 yr | Fixed temperature 35°C; duration: two sessions | Fixed temperature 37.5°C; duration: two sessions | BP; body temperature; IDH; hemodynamics; dialysis adequacy | Not reported |

| Australia (40) | Crossover design; allocation concealment: NR; sequence generation: NR; blinding: NR; dropouts: 0 | n=17 (nine men, eight women); BP: all stable; age 63.3±3.2 yr | Fixed temperature 35°C; duration: NC | Fixed temperature 37°C; duration: NC | BP; Hemodynamics | Arthritis, severe PAD, α- or β-adrenergic blockers |

NR, not reported; IDH, intradialytic hypotension; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; NYHA, New York Heart Association classification; DM, diabetes mellitus; BTM, biofeedback temperature monitoring; EF, ejection fraction; HTN, hypertension; HD, hemodialysis; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti–inflammatory drugs; QOL, quality of life; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NC, not clear; PAD, peripheral arterial disease.

None of the studies stopped early for benefit. It is not clear if the studies had selective reporting of outcomes.

Participants.

The included trials involved 484 participants; 24 of 26 trials were small, with <20 participants (6–19 participants). The remaining two trials involved 95 and 128 participants (19,20). The main inclusion criteria were adults (≥18 years old) with variability in baseline BP and duration on hemodialysis.

Intervention.

Overall, the duration of each trial was short. Eighteen trials reported the effect of cool dialysis on the basis of two sessions of hemodialysis (one session in each arm of the trial) (16,17,21,23,27–39,41). Three trials evaluated the intervention in three to six hemodialysis sessions (22–24). Only three trials followed patients longer than six sessions (18, 20, and 24 sessions on average, respectively) (18–20). Of note, trials with prolonged follow-up had a high dropout rate, and an intention-to-treat analysis was not followed. It is not clear if the dropouts were preferential in cool dialysis or not. Twenty trials used fixed temperature cooling of dialysate fluid (34°C–35.5°C). Six trials used a biofeedback temperature monitoring device (one negative energy, two cooling, and three isothermic devices). In the standard dialysis group, the dialysate temperature ranged from 36°C to 37.5°C, except for in one trial that used a temperature of 38.5°C. Including or excluding this trial did not affect our results, and we decided to include it, although a temperature >37.5°C is higher than the standard and an unusual practice.

Outcomes.

No trial included mortality, hospitalization, cardiovascular events, access failure, bleeding, or system clotting as an outcome. One trial reported the effect of cooling dialysate on QOL; 12 trials reported intradialytic hypotension, 24 trials reported BP, nine trials reported dialysis adequacy, and ten trials reported symptoms of discomfort.

Risk of Bias within Studies

Seven trials described blinding of patients, four trials blinded health care providers or investigators, two trials reported no blinding, and blinding was unclear in the rest of the trials. Only one trial reported a central process for random sequence generation, and the rest did not report any methods for sequence generation or concealment of allocation. We encountered challenges when evaluating our criteria of selective reporting of outcomes, because published protocols for those trials were unavailable. None of the trials were stopped early for benefit or harm.

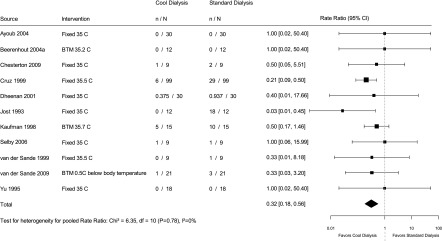

Intradialytic Hypotension

Thirteen trials reported intradialytic hypotension as an outcome. We summarize the definitions used by these trials to define intradialytic hypotension in Supplemental Appendix 3. Two trials (19,20) reported intradialytic hypotension as the proportion of sessions where it occurred. These studies (19,20) reported that 5.5%–25% of the dialysis sessions were complicated by intradialytic hypotension in the cool dialysis group compared with 11.2%–50% of the sessions in the usual dialysate group. The pooled effect on the basis of 11 trials (Figure 2), which included a total of 552 hemodialysis sessions in 120 patients (with an average of 4.6 sessions per patient), showed that the rate of intradialytic hypotension was reduced by 70% (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 49% to 89%) with cool dialysis compared with standard dialysis (I2=0%).

Figure 2.

Effect of low temperature dialysis on intradialytic hypotension. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; BTM, biofeedback temperature monitoring.

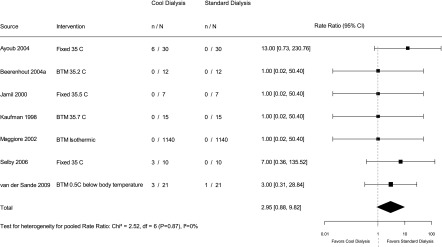

Symptoms of Discomfort

The symptoms that were considered were discomfort on dialysis from feeling cold, shivering, or cramps. The reporting of symptoms of discomfort during dialysis was generally poor. Ten trials reported these symptoms, but they did not uniformly rate their severity. Cruz et al. (18) reported the proportion of sessions with symptoms on cold dialysate (13%). The pooled effect on the basis of nine trials (Figure 3), which included a total of 2548 hemodialysis sessions, showed that symptoms occur 2.95 (95% CI, 0.88 to 9.82) times more commonly with cool dialysis compared with standard dialysis (I2=0%).

Figure 3.

Effect of low temperature dialysis on symptoms of discomfort. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; BTM, biofeedback temperature monitoring.

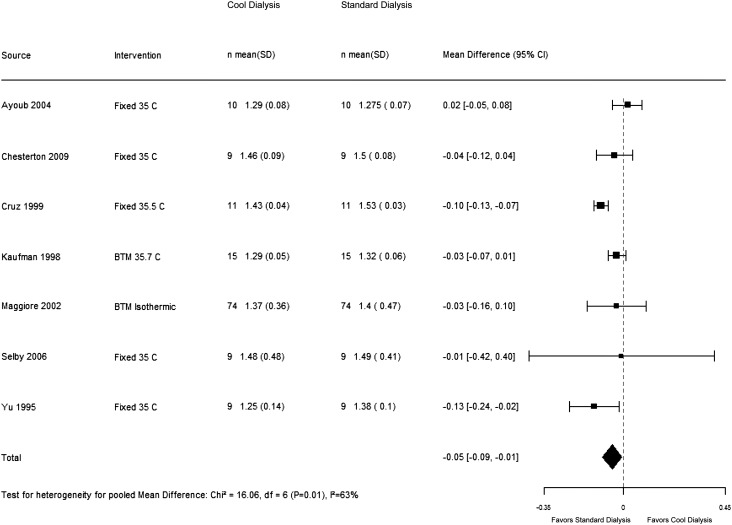

Dialysis Adequacy

Nine trials reported dialysis adequacy as an outcome. Dheenan and Henrich (23) reported urea reduction rate. Levin and colleagues (22) reported no difference in urea kinetics, but no clear estimates were presented. The other seven trials reported Kt/V. Our results show that cool dialysis did not have a significant effect on dialysis adequacy compared with standard dialysis, with a pooled Kt/V mean difference of −0.05 (95% CI, −0.09 to 0.01). We observed some heterogeneity in the results on this outcome across the trials (I2=63%) (Figure 4), which was partially explained (I2=18%) when we conducted a predefined sensitivity analysis on the basis of risk of bias.

Figure 4.

Effect of low temperature dialysis on dialysis adequacy. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; BTM, biofeedback temperature monitoring.

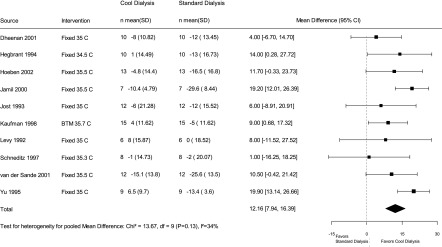

BP

Twenty-four trials reported BP. Some reported a change in mean arterial pressure (MAP), intradialytic MAP, MAP posthemodialysis, changes in systolic and diastolic BP, or systolic and diastolic BP posthemodialysis. We choose to pool change in MAP (before and after hemodialysis), because it is less affected by baseline BP before hemodialysis and was one of the most frequently reported BP measures in the included trials. We meta-analyzed the results of ten trials that reported change in MAP (Figure 5). Our results show that cool dialysis is associated with significantly higher MAP of 12 mmHg (95% CI, 8 to 16 mmHg) compared with standard dialysis (I2=34%). Additionally, in Table 2, we summarize the effect on other measures of BP described in 14 trials that we were not able to mathematically pool.

Figure 5.

Effect of low temperature dialysis on change in mean arterial pressure. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; BTM, biofeedback temperature monitoring.

Table 2.

Summary of BP measures in trials that did not report change in mean arterial pressure

| Reference no. | Cool HD | Standard HD |

|---|---|---|

| 25 | Low BP group: intradialytic MAP: 92±8.4 mmHg; postdialysis MAP: 95.9±10.9 mmHg; stable BP group: intradialytic MAP: 99±11.5 mmHg; postdialysis MAP: 102±13.5 mmHg | Low BP group: intradialytic MAP: 81±7.2 mmHg; P<0.01a; postdialysis MAP: 86.9±7.3 mmHg; P=0.01a; stable BP group: intradialytic MAP: 96.5±12.1 mmHg; postdialysis MAP: 100±14.0 mmHg |

| 16 | Change in SBP: −6.0±2 mmHgb; change in DBP: −4.1±7.6 mmHgb | Change in SBP: −0.8±22.7 mmHgb; change in DBP: −3.8±12.4 mmHgb |

| 26 | SBP: 146±5 mmHg before dialysis; 140±6 mmHg after dialysis; DBP: 81±3 mmHg before dialysis; 79±4 mmHg after dialysis | SBP: 150±5 mmHg before dialysis; 132±4 mmHg after dialysis; DBP: 81±2 mmHg before dialysis; 76±3 mmHg after dialysis |

| 17 | SBP reduction: 2.71±0.97%; DBP reduction: 8.63±1.19%; intradialytic MAP reduction: 3.01±0.98% | SBP reduction: −7.54±1.92%; P<0.001a; DBP reduction: −4.99±1.4%; P<0.001a; intradialytic MAP reduction: −8.99±1.71%; P<0.001 |

| 18 | Mean lowest intradialytic SBP: 102.5±2.9 mmHg; mean lowest intradialytic DBP: 61.7±2.3 mmHg; intradialytic MAP: 75.0±2.3 mmHg; SBP: 132±3.3 mmHg before dialysis; 118.1±3.5 mmHg after dialysis; DBP: 73.7±2.3 mmHg before dialysis; 69.2±2.6 mmHg after dialysis | Mean lowest intradialytic SBP: 90.6±2.5 mmHg; P<0.001a; mean lowest intradialytic DBP: 54.9±2.2 mmHg; P=0.02a; intradialytic MAP: 66.8±2.1 mmHg; P=0.002a; SBP: 132.7±3.4 mmHg before dialysis; 109.0±2.1 mmHg after dialysis; P<0.01a; DBP: 74.9±3.0 mmHg before dialysis; 63.6±1.9 mmHg after dialysis; P=0.01a |

| 32 | MAP did not change with time at the end of cool HD | MAP decreased by 10% at the end of normal HD; P= significant |

| 33 | MAP increased in six of nine sessionsb | MAP increased in one of nine sessionsb |

| 20 | SBP reduction: −14.2±16.5 mmHg; DBP reduction: −5.8±8.1 mmHg | SBP reduction: −20.5±15.7 mmHg; DBP reduction: −8.8±8.4 mmHg; P<0.05a |

| 41 | Mean intradialytic SBP: 136.9±11.4 mmHg; mean intradialytic DBP: 75.4±6.0 mmHg; mean intradialytic MAP: 95.7±7.5 mmHg | Mean intradialytic SBP: 130.7±10.5 mmHg; mean intradialytic DBP: 72.3±6.0 mmHg; average intradialytic MAP: 91.6±7.4 mmHg |

| 21 | Mean SBP: 158.8±14 mmHg; mean DBP: 78.6±4 mmHg; average intradialytic MAP: 110.9±7 mmHg | Mean SBP: 141.6±17 mmHg; P<0.001a; mean DBP: 69.4±5 mmHg; P<0.001a; average intradialytic MAP: 92.6±10 mmHg; P<0.001a |

| 36 | Maximum decrease in intradialytic SBP: 21.8±26.1 mmHg; maximum decrease in intradialytic DBP: −0.1±19.2 mmHg; SBP: 130.3±21.7 mmHg before dialysis; 131.6±21.4 mmHg after dialysis; DBP: 72.2±10.2 mmHg before dialysis; 63.7±9.0 mmHg after dialysis | Maximum decrease in intradialytic SBP: 43.2±20.6 mmHg; maximum decrease in intradialytic DBP: 14.9±9.6 mmHg; SBP: 144.4±25.9 mmHg before dialysis; 117.3±26.1 mmHg after dialysis; DBP: 72.2±10.2 mmHg before dialysis; 67.0±10.9 mmHg after dialysis |

| 37 | SBP: 144±24 mmHg before dialysis; 144±26 mmHg after dialysis; DBP: 68±14 mmHg before dialysis; 76±12 mmHg after dialysis | SBP: 152±22 mmHg before dialysis; 134±23 mmHg after dialysis; DBP: 75±9 mmHg before dialysis; 71±13 mmHg after dialysis |

| 22 | SBP: 159±35 mmHg before dialysis; 127±39 mmHg after dialysis; P<0.05c; DBP: 82±12 mmHg before dialysis; 70±17 mmHg after dialysis; P<0.05c; intradialytic lowest SBP: 113±30 mmHg | SBP: 151±27 mmHg before dialysis; 122±28 mmHg after dialysis; P<0.05c; DBP: 82±11 mmHg before dialysis; 65±12 mmHg after dialysis; P<0.05c; intradialytic lowest SBP: 104±27 mmHg; P=0.08 |

| 40 | SBP: 127±6.4 mmHg before dialysis; 134±3.9 mmHg after dialysis; DBP: 76±3.9 mmHg before dialysis; 81±3.5 mmHg after dialysis | SBP: 126±4.6 mmHg before dialysis; 127±2.1 mmHg after dialysis; DBP: 74±2.8 mmHg before dialysis; 74±3.2 mmHg after dialysis |

Effect estimates are presented as BP measure±SD. HD, hemodialysis; MAP, mean arterial pressure; NS, not significant; SBP, systolic BP; DBP, diastolic BP.

P value comparing cool and standard HD.

After HD compared with before HD.

P value for end versus start of dialysis.

QOL

The work by Selby et al. (21) was the only trial that reported the effect of cool dialysis on QOL. In this trial, there was no difference between cool and standard dialysis on QOL using the short form 36 health survey assessment tool. Ayoub and Finlayson (25), although not clearly assessing QOL, did indicate that 80% of the patients receiving cool dialysis self-reported a dramatic improvement in their general health.

Additional Analyses

According to our protocol for this systematic review, we explored the effects of cool dialysis on heterogeneous outcomes by subgroup analysis. We stratified by different interventions (fixed versus biofeedback temperature monitoring device cooling of dialysate) and patient characteristics (stability of baseline BP). The latter analysis was limited to the trials that reported baseline BP. The subgroup analyses did not explain heterogeneity and did not affect the overall pooled estimate of dialysis adequacy.

To assess the robustness of the pooled estimate, we conducted sensitivity analyses on the basis of risk of bias in studies. Excluding studies with significant loss to follow-up (18,20) resulted in partial explanation of heterogeneity (I2=63%–18%) for dialysis adequacy without affecting the overall pooled estimates of the remaining trials.

Quality of Evidence for the Body of Evidence

Overall, the quality of evidence for the outcomes of interest across all studies was graded low or very low. Details about different domains assessing the quality of evidence using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach are summarized in the evidence profile (Table 3). We did not find evidence for publication bias using funnel plots and Egger linear regression test (intradialytic hypotension [P=0.41], symptoms of discomfort [P=0.13], dialysis adequacy [P=0.49], and change in MAP [P=0.17]). We were not able to fit metaregression models to examine the association with loss to follow-up for dialysis adequacy because of insufficient data.

Table 3.

Evidence profile

| Quality Assessment | No. of Studies | Design | Limitations | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other Considerations | No. of Hemodialysis Sessions and Patients | Effect: Absolute | Quality | Importance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cool Dialysis | Standard Dialysis | |||||||||||

| Mortality—not reported | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Critical | |

| Quality of life (measured with SF-36; better indicated by higher values) | 1 | Randomized trial | Very seriousa | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Very seriousb | None | 18 hemodialysis sessions in nine patients | 18 hemodialysis sessions in nine patients | MD 1 higher (21.64 lower to 23.64 higher) | ⊕○○○ | Critical |

| Hospitalization—not reported | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Critical | |

| Intradialytic hypotension (measured with no. of events per dialysis session; rate ratio <1.0 implies that cool dialysis versus standard dialysis has a lower risk of the outcome) | 11 | Randomized trials | Very seriousc | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 264 hemodialysis sessions in 120 patients | 264 hemodialysis sessions in 120 patients | Rate ratio 0.3 higher (0.11–0.51 higher) | ⊕⊕○○ | Critical |

| Symptoms of discomfort (cold or cramping; measured with no. of events per dialysis session; rate ratio <1.0 implies that cool dialysis versus standard dialysis has a lower risk of the outcome) | 9 | Randomized trials | Very seriousd | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Seriouse | None | 1234 hemodialysis sessions in 141 patients | 1234 hemodialysis sessions in 141 patients | Rate ratio 2.95 (0.88–9.82) | ⊕○○○ | Critical |

| Dialysis adequacy (measured with Kt/V; better indicated by lower values) | 7 | Randomized trials | Very seriousf | No serious inconsistencyg | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 2100 hemodialysis sessions in 137 patients | 2100 hemodialysis sessions in 137 patients | MD 0.05 lower (0.09 lower to 0.01 higher) | ⊕⊕○○ | Important |

| Change in mean arterial pressure (measured with millimeters of mercury; better indicated by lower values) | 10 | Randomized trials | Very serioush | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 731 hemodialysis sessions in 102 patients | 731 hemodialysis sessions in 102 patients | MD 12 higher (8–16 higher) | ⊕⊕○○ | Important |

Question: what are the benefits and harms of cool versus standard dialysis for patients with ESRD? Settings: chronic hemodialysis (inpatient or outpatient). — denotes no data available. SF-36, short form 36 health survey; MD, mean difference; ⊕○○○ very low, ⊕⊕○○ low.

Unclear method for sequence generation and concealment of allocation reported. Only patients were blinded; one of ten patients dropped out of the study (in the work by Selby et al. [21]).

Only one trial reported quality of life. The 95% confidence interval of the results crossed zero, with a very wide 95% confidence interval ranging from considerable benefit to considerable harm.

Unclear methods of sequence generation and concealment of allocation in any of 11 studies; two of 11 studies reported patient blinding, one of 11 studies reported staff blinding, one of 11 studies reported no blinding, and in seven of 11 studies, blinding was unclear.

Unclear methods of sequence generation and concealment of allocation in eight of nine studies; only one of nine studies reported a central process of sequence generation. Two of nine studies reported no blinding, one of nine studies blinded staff but not patients, and blinding was not clear in six of nine studies. Three of nine studies report patients dropping out of the study; in one of them, 21 of 95 patients dropped out.

Lower limit of the 95% confidence interval suggests no effect.

Unclear methods of sequence generation or concealment of allocation in six of seven studies; only one of seven studies reported central sequence generation. Three of seven studies reported blinding of patients only, two of seven studies clearly reported no blinding, and blinding was not clear in two of seven studies. Four of seven studies had patients drop out of the studies; in one study, 21 of 95 patients dropped out, and in another study, eight of 19 patients dropped out.

Substantial heterogeneity (I2=63%) that was partially explained by excluding studies with loss to follow-up (I2=18%).

Unclear methods for sequence generation and concealment of allocation reported. Blinding: four of ten studies blinded patients, one of ten studies blinded staff, one of ten studies blinded providers, and one of ten studies blinded investigators.

Discussion

Twenty-six crossover, randomized trials (including 484 patients) with varying degrees of methodologic rigor were included in this systematic review. The results suggest that cool dialysis significantly reduces the rate of intradialytic hypotension. The available evidence suggests no negative effect on dialysis adequacy, with an increase in symptoms of discomfort of unclear severity.

This review has several strengths. This review extends the review by Selby and McIntyre (6) in many ways. We have identified and analyzed four more trials in this review. The comprehensive and up-to-date search makes it unlikely that relevant trials were missed. All steps, including initial screening, trials selection, and data abstraction, were performed independently in duplicate to minimize any potential biases arising from subjectivity in these tasks. Additionally, we translated non-English articles. Finally, we analyzed sources of bias and explored reasons for diversity in the published literature.

This review has few limitations. The results of this review are inherently limited by the quality of the primary included studies. First, the majority of included studies are small with short follow-up times. Second, no studies reported long–term patient–important outcomes, which is a major limitation in this area. None of the included studies, except one, reported a central method of random sequence generation or allocation concealment. Also, none of the studies had appropriately blinded patients, investigators, dialysis nurses, clinical outcome assessors, data collectors, and data analyzers. Additionally, seven trials had significant patient dropout from 8% to 42%. One may assume that the high rates of dropouts in some studies may be because of intolerability. However, the lack of information about timing and reasons for the dropouts makes it difficult to know whether this assumption is true. Surprisingly, we did not observe any improvement in the methodologic quality of the trials in more recent reports compared with earlier ones. Also, we did not observe any progress in reporting long–term patient–important outcomes.

Despite our low confidence in the estimates of effect owing to imprecision and risk of bias, cool dialysis remains a promising therapy that, we believe, is not frequently used. This may be because of the lack of high-quality evidence to support its possible net benefit or physicians’ beliefs about a negative side effect profile. Still, this intervention is quite simple and can be implemented in any dialysis center in the world without any additional cost other than training nursing staff on a new protocol.

Cool dialysis can be achieved by either a fixed reduction in the temperature of the dialysate fluid or use of a biofeedback device. It will be of interest to the nephrology community to have trials that directly compare the effect of fixed empirical reduction of dialysate temperature with isothermic or cool biofeedback temperature monitoring devices, because the former does not consider patients’ variability in core temperature and access recirculation, but the latter does. This direct comparison may provide information about the optimal management for patients at high risk of intradialytic hypotension during hemodialysis without causing significant symptoms of discomfort.

Additionally, cool dialysis seems promising when evaluating other surrogate outcomes that we did not explore in this review. The study by Eldehni et al. (42) shows that hemodialysis results in a significant amount of magnetic resonance imaging changes signifying brain injury that could possibly be alleviated by the use of cold-temperature hemodialysis. Also, Parker et al. (41) have found that the use of cold-temperature hemodialysis may improve nocturnal sleep by decreasing sympathetic activation and sustaining the nocturnal skin temperature. The poor reporting of symptoms of discomfort and the lack of systematic evaluation of their severity continue to limit the ability to accurately assess the effect of cool dialysis on significant patient discomfort. This review highlights that high–quality, large, multicenter studies with long follow-up are needed to assess the effect of cool dialysis on long–term patient–important outcomes, like mortality, major adverse cardiovascular events, hospitalization, patients’ functional and cognitive status, and discomfort.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Part of this study was funded by the Ontario Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research Support Unit. A.X.G. is supported by the Adam Linton Chair in Kidney Health Analytics.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.04580415/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Grassmann A, Gioberge S, Moeller S, Brown G: ESRD patients in 2004: Global overview of patient numbers, treatment modalities and associated trends. Nephrol Dial Transplant 20: 2587–2593, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daugirdas JT: Pathophysiology of dialysis hypotension: An update. Am J Kidney Dis 38[Suppl 4]: S11–S17, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosa AA, Fryd DS, Kjellstrand CM: Dialysis symptoms and stabilization in long-term dialysis. Practical application of the CUSUM plot. Arch Intern Med 140: 804–807, 1980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zager PG, Nikolic J, Brown RH, Campbell MA, Hunt WC, Peterson D, Van Stone J, Levey A, Meyer KB, Klag MJ, Johnson HK, Clark E, Sadler JH, Teredesai P: “U” curve association of blood pressure and mortality in hemodialysis patients. Medical Directors of Dialysis Clinic, Inc. Kidney Int 54: 561–569, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maggiore Q, Pizzarelli F, Zoccali C, Sisca S, Nicolò F, Parlongo S: Effect of extracorporeal blood cooling on dialytic arterial hypotension. Proc Eur Dial Transplant Assoc 18: 597–602, 1981 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selby NM, McIntyre CW: A systematic review of the clinical effects of reducing dialysate fluid temperature. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 1883–1898, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, Egger M, Davidoff F, Elbourne D, Gøtzsche PC, Lang T, CONSORT GROUP (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) : The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: Explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 134: 663–694, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moher D, Jones A, Lepage L, CONSORT Group (Consolidated Standards for Reporting of Trials) : Use of the CONSORT statement and quality of reports of randomized trials: A comparative before-and-after evaluation. JAMA 285: 1992–1995, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D: The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 62: e1–e34, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chapter 6: Searching for studies. Lefepvre C, Manheimer E, Glanville J: Cochrane Information Retrieval Methods Group: Chapter 6: Searching for studies. Available at: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org/. Accessed January 1, 2011.

- 11.Cohen J: Weighted kappa: Nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol Bull 70: 213–220, 1968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, GRADE Working Group : GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 336: 924–926, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C: Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315: 629–634, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lau J, Ioannidis JP, Schmid CH: Summing up evidence: One answer is not always enough. Lancet 351: 123–127, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DerSimonian R, Laird N: Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 7: 177–188, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beerenhout C, Dejagere T, van der Sande FM, Bekers O, Leunissen KM, Kooman JP: Haemodynamics and electrolyte balance: A comparison between on-line pre-dilution haemofiltration and haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 19: 2354–2359, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chesterton LJ, Selby NM, Burton JO, McIntyre CW: Cool dialysate reduces asymptomatic intradialytic hypotension and increases baroreflex variability. Hemodial Int 13: 189–196, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cruz DN, Mahnensmith RL, Brickel HM, Perazella MA: Midodrine and cool dialysate are effective therapies for symptomatic intradialytic hypotension. Am J Kidney Dis 33: 920–926, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fine A, Penner B: The protective effect of cool dialysate is dependent on patients’ predialysis temperature. Am J Kidney Dis 28: 262–265, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maggiore Q, Pizzarelli F, Santoro A, Panzetta G, Bonforte G, Hannedouche T, Alvarez de Lara MA, Tsouras I, Loureiro A, Ponce P, Sulkovà S, Van Roost G, Brink H, Kwan JT, Study Group of Thermal Balance and Vascular Stability : The effects of control of thermal balance on vascular stability in hemodialysis patients: Results of the European randomized clinical trial. Am J Kidney Dis 40: 280–290, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Selby NM, Burton JO, Chesterton LJ, McIntyre CW: Dialysis-induced regional left ventricular dysfunction is ameliorated by cooling the dialysate. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 1216–1225, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Sande FM, Wystrychowski G, Kooman JP, Rosales L, Raimann J, Kotanko P, Carter M, Chan CT, Leunissen KM, Levin NW: Control of core temperature and blood pressure stability during hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 93–98, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dheenan S, Henrich WL: Preventing dialysis hypotension: A comparison of usual protective maneuvers. Kidney Int 59: 1175–1181, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu AW, Ing TS, Zabaneh RI, Daugirdas JT: Effect of dialysate temperature on central hemodynamics and urea kinetics. Kidney Int 48: 237–243, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ayoub A, Finlayson M: Effect of cool temperature dialysate on the quality and patients’ perception of haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 19: 190–194, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beerenhout CH, Noris M, Kooman JP, Porrati F, Binda E, Morigi M, Bekers O, van der Sande FM, Todeschini M, Macconi D, Leunissen KM, Remuzzi G: Nitric oxide synthetic capacity in relation to dialysate temperature. Blood Purif 22: 203–209, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hegbrant J, Mãrtensson L, Ekman R, Nielsen AL, Thysell H: Dialysis fluid temperature and vasoactive substances during routine hemodialysis. ASAIO J 40: M678–M682, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoeben H, Abu-Alfa AK, Mahnensmith R, Perazella MA: Hemodynamics in patients with intradialytic hypotension treated with cool dialysate or midodrine. Am J Kidney Dis 39: 102–107, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jamil KM, Yokoyama K, Takemoto F, Hara S, Yamada A: Low temperature hemodialysis prevents hypote nsive episodes by reducingnitric oxide synthesis. Nephron 84: 284–286, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jost CM, Agarwal R, Khair-el-Din T, Grayburn PA, Victor RG, Henrich WL: Effects of cooler temperature dialysate on hemodynamic stability in “problem” dialysis patients. Kidney Int 44: 606–612, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaufman AM, Morris AT, Lavarias VA, Wang Y, Leung JF, Glabman MB, Yusuf SA, Levoci AL, Polaschegg HD, Levin NW: Effects of controlled blood cooling on hemodynamic stability and urea kinetics during high-efficiency hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 877–883, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kishimoto T, Yamamoto T, Shimizu G, Horiuchi N, Hirata S, Nishitani H, Mizutani Y, Yamakawa M, Yamazaki Y, Maekawa M: Cardiovascular stability in low temperature dialysis. Dial Transplant 15: 329–333, 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levin NW, Morris AT, Lavarias VA, Wang Y, Glabman MB, Leung JP, Yusuf SA, LeVoci AL, Polaschegg HD, Kaufman AM: Effects of body core temperature reduction on haemodynamic stability and haemodialysis efficacy at constant ultrafiltration. Nephrol Dial Transplant 11[Suppl 2]: 31–34, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levy FL, Grayburn PA, Foulks CJ, Brickner ME, Henrich WL: Improved left ventricular contractility with cool temperature hemodialysis. Kidney Int 41: 961–965, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schneditz D, Martin K, Krämer M, Kenner T, Skrabal F: Effect of controlled extracorporeal blood cooling on ultrafiltration-induced blood volume changes during hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 956–964, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van der Sande FM, Kooman JP, Burema JH, Hameleers P, Kerkhofs AM, Barendregt JM, Leunissen KM: Effect of dialysate temperature on energy balance during hemodialysis: Quantification of extracorporeal energy transfer. Am J Kidney Dis 33: 1115–1121, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van der Sande FM, Gladziwa U, Kooman JP, Böcker G, Leunissen KM: Energy transfer is the single most important factor for the difference in vascular response between isolated ultrafiltration and hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1512–1517, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van der Sande FM, Kooman JP, Konings CJ, Leunissen KM: Thermal effects and blood pressure response during postdilution hemodiafiltration and hemodialysis: The effect of amount of replacement fluid and dialysate temperature. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1916–1920, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van der Sande FM, Rosales LM, Brener Z, Kooman JP, Kuhlmann M, Handelman G, Greenwood RN, Carter M, Schneditz D, Leunissen KM, Levin NW: Effect of ultrafiltration on thermal variables, skin temperature, skin blood flow, and energy expenditure during ultrapure hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 1824–1831, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zitt E, Neyer U, Meusburger E, Tiefenthaler M, Kotanko P, Mayer G, Rosenkranz AR: Effect of dialysate temperature and diabetes on autonomic cardiovascular regulation during hemodialysis. Kidney Blood Press Res 31: 217–225, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parker KP, Bailey JL, Rye DB, Bliwise DL, Van Someren EJ: Lowering dialysate temperature improves sleep and alters nocturnal skin temperature in patients on chronic hemodialysis. J Sleep Res 16: 42–50, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eldehni MT, Odudu A, McIntyre CW: Randomized clinical trial of dialysate cooling and effects on brain white matter. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 957–965, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dhondt A, Eloot S, Verbeke F, Vanholder R: Dialysate and blood temperature during hemodialysis: Comparing isothermic dialysis with a single-pass batch system. Artif Organs 34: 1132–1137, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Donauer J, Schweiger C, Rumberger B, Krumme B, Böhler J: Reduction of hypotensive side effects during online-haemodiafiltration and low temperature haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 1616–1622, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.du Cheyron D, Terzi N, Seguin A, Valette X, Prevost F, Ramakers M, Daubin C, Charbonneau P, Parienti JJ: Use of online blood volume and blood temperature monitoring during haemodialysis in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury: A single-centre randomized controlled trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant 28: 430–437, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hecking M, Antlanger M, Winnicki W, Reiter T, Werzowa J, Haidinger M, Weichhart T, Polaschegg HD, Josten P, Exner I, Lorenz-Turnheim K, Eigner M, Paul G, Klauser-Braun R, Hörl WH, Sunder-Plassmann G, Säemann MD: Blood volume-monitored regulation of ultrafiltration in fluid-overloaded hemodialysis patients: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 13: 79, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Odudu A, Eldehni MT, Fakis A, McIntyre CW: Rationale and design of a multi-centre randomised controlled trial of individualised cooled dialysate to prevent left ventricular systolic dysfunction in haemodialysis patients. BMC Nephrol 13: 45, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alappan R, Cruz D, Abu-Alfa AK, Mahnensmith R, Perazella MA: Treatment of severe intradialytic hypotension with the addition of high dialysate calcium concentration to midodrine and/or cool dialysate. Am J Kidney Dis 37: 294–299, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barendregt JN, Kooman JP, Buurma JH, Hameleers P, Kerkhofs AM, Leunissen KM, Van Der Sande FM : The effect of dialysate temperature on energy transfer during hemodialysis (HD). Kidney Int 55: 2598–2608, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bazzato G, Coli U, Landini S, Lucatello S, Fracasso A, Morachiello P, Righetto F, Scanferla F: Vascular stability and temperature monitoring in patients prone to dialysis-induced hypotension. Contrib Nephrol 41: 394–397, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bazzato G, Coli U, Landini S, Lucatello S, Fracasso A, Morachiello P, Righetto F, Scanferla F: Temperature monitoring in dialysis-induced hypotension. Kidney Int Suppl 17: S161–S165, 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Canaud B, Chenine L, Renaud S, Leray H: Optimal therapeutic conditions for online hemodiafiltration. Contrib Nephrol 168: 28–38, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Coli U, Landini S, Lucatello S, Fracasso A, Morachiello P, Righetto F, Scanferla F, Onesti G, Bazzato G: Cold as cardiovascular stabilizing factor in hemodialysis: Hemodynamic evaluation. Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs 29: 71–75, 1983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Colì L, La Manna G, Comai G, Ursino M, Ricci D, Piccari M, Locatelli F, Di Filippo S, Cristinelli L, Bacchi M, Balducci A, Aucella F, Panichi V, Ferrandello FP, Tarchini R, Lambertini D, Mura C, Marinangeli G, Di Loreto E, Quarello F, Forneris G, Tancredi M, Morosetti M, Palombo G, Di Luca M, Martello M, Emiliani G, Bellazzi R, Stefoni S: Automatic adaptive system dialysis for hemodialysis-associated hypotension and intolerance: A noncontrolled multicenter trial. Am J Kidney Dis 58: 93–100, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ghasemi A, Shafiee M, Rowghani K: Stabilizing effects of cool dialysate temperature on hemodynamic parameters in diabetic patients undergoing hemodialysis. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 19: 378–383, 2008 [PubMed]

- 56.Gotch FA, Keen ML, Yarian SR: An analysis of thermal regulation in hemodialysis with one and three compartment models. ASAIO Trans 35: 622–624, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hsu HJ, Yen CH, Hsu KH, Lee CC, Chang SJ, Wu IW, Sun CY, Chou CC, Yu CC, Hsieh MF, Chen CY, Hsu CY, Weng CH, Tsai CJ, Wu MS: Association between cold dialysis and cardiovascular survival in hemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 2457–2464, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jefferies HJ, Burton JO, McIntyre CW: Individualised dialysate temperature improves intradialytic haemodynamics and abrogates haemodialysis-induced myocardial stunning, without compromising tolerability. Blood Purif 32: 63–68, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Keijman JM, van der Sande FM, Kooman JP, Leunissen KM: Thermal energy balance and body temperature: Comparison between isolated ultrafiltration and haemodialysis at different dialysate temperatures. Nephrol Dial Transplant 14: 2196–2200, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kerr PG, van Bakel C, Dawborn JK: Assessment of the symptomatic benefit of cool dialysate. Nephron 52: 166–169, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Leunissen KM, Kooman JP, van Kuijk W, van der Sande F, Luik AJ, van Hooff JP: Preventing haemodynamic instability in patients at risk for intra-dialytic hypotension. Nephrol Dial Transplant 11[Suppl 2]: 11–15, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lima EQ, Silva RG, Donadi EL, Fernandes AB, Zanon JR, Pinto KR, Burdmann EA: Prevention of intradialytic hypotension in patients with acute kidney injury submitted to sustained low-efficiency dialysis. Ren Fail 34: 1238–1243, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lindholm T, Thysell H, Yamamoto Y, Forsberg B, Gullberg CA: Temperature and vascular stability in hemodialysis. Nephron 39: 130–133, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cadena M, Medel H, Rodrguez F, Flores P, Mariscal A, Franco M, Pérez-Grovas H, Escalante B: Isothermic vs thermoneutral hemodiafiltration evaluation by indirect calorimetry. Presented at the Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, August 21–24 2008 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Maggiore Q, Pizzarelli F, Sisca S, Catalano C, Delfino D: Vascular stability and heat in dialysis patients. Contrib Nephrol 41: 398–402, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Maggiore Q, Pizzarelli F, Zoccali C, Sisca S, Nicolò F: Influence of blood temperature on vascular stability during hemodialysis and isolated ultrafiltration. Int J Artif Organs 8: 175–178, 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maggiore Q: Isothermic dialysis for hypotension-prone patients. Semin Dial 15: 187–190, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mahida BH, Dumler F, Zasuwa G, Fleig G, Levin NW: Effect of cooled dialysate on serum catecholamines and blood pressure stability. Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs 29: 384–389, 1983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Marcen R, Orofino L, Quereda C, Pascual J, Ortuño J: Effects of cool dialysate in dialysis-related symptoms. Nephron 54: 356–357, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Marcén R, Quereda C, Orofino L, Lamas S, Teruel JL, Matesanz R, Ortuño J: Hemodialysis with low-temperature dialysate: A long-term experience. Nephron 49: 29–32, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Orofino L, Marcén R, Quereda C, Villafruela JJ, Sabater J, Matesanz R, Pascual J, Ortuño J: Epidemiology of symptomatic hypotension in hemodialysis: Is cool dialysate beneficial for all patients? Am J Nephrol 10: 177–180, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Panzetta G, Bianco F, Galli G, Ianche M, Savoldi S, Vianello S, Vidi E, Cicinato P: Thermal energy balance during hemodialysis: The role of the filter membrane. G Ital Nefrol 19: 425–431, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Parker KP, Bailey JL, Rye DB, Bliwise DL, Van Someren EJ: Insomnia on dialysis nights: The beneficial effects of cool dialysate. J Nephrol 21[Suppl 13]: S71–S77, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Provenzano R, Sawaya B, Frinak S, Polaschegg HD, Roy T, Zasuwa G, Dumler F, Levin NW: The effect of cooled dialysate on thermal energy balance in hemodialysis patients. ASAIO Trans 34: 515–518, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Quereda C, Marcén R, Lamas S, Hernández-Jodra M, Orofino L, Sabater J, Villafruela J, Ortuño J: Hemodialysis associated hypotension and dialysate temperature. Life Support Syst 3[Suppl 1]: 18–22, 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sherman RA, Faustino EF, Bernholc AS, Eisinger RP: Effect of variations in dialysate temperature on blood pressure during hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 4: 66–68, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sherman RA, Rubin MP, Cody RP, Eisinger RP: Amelioration of hemodialysis-associated hypotension by the use of cool dialysate. Am J Kidney Dis 5: 124–127, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.van Kuijk WH, Hillion D, Savoiu C, Leunissen KM: Critical role of the extracorporeal blood temperature in the hemodynamic response during hemofiltration. J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 949–955, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.van Kuijk WH, Luik AJ, de Leeuw PW, van Hooff JP, Nieman FH, Habets HM, Leunissen KM: Vascular reactivity during haemodialysis and isolated ultrafiltration: Thermal influences. Nephrol Dial Transplant 10: 1852–1858, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.van der Sande FM, Kooman JP, van Kuijk WH, Leunissen KM: Management of hypotension in dialysis patients: Role of dialysate temperature control. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 12: 382–386, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Maggiore Q, Pizzarelli F, Dattolo P, Maggiore U, Cerrai T: Cardiovascular stability during haemodialysis, haemofiltration and haemodiafiltration. Nephrol Dial Transplant 15[Suppl 1]: 68–73, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brewster UC, Ciampi MA, Abu-Alfa AK, Perazella MA: Addition of sertraline to other therapies to reduce dialysis-associated hypotension. Nephrology (Carlton) 8: 296–301, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Maggiore Q, Pizzarelli F, Sisca S, Zoccali C, Parlongo S, Nicolò F, Creazzo G: Blood temperature and vascular stability during hemodialysis and hemofiltration. Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs 28: 523–527, 1982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Maggiore Q, Dattolo P, Piacenti M, Morales MA, Pelosi G, Pizzarelli F, Cerrai T: Thermal balance and dialysis hypotension. Int J Artif Organs 18: 518–525, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Maggiore Q, Enia G, Catalano C, Misefari V, Mundo A: Effect of blood cooling on cuprophan-induced anaphylatoxin generation. Kidney Int 32: 908–911, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nesrallah GE, Suri RS, Guyatt G, Mustafa RA, Walter SD, Lindsay RM, Akl EA: Biofeedback dialysis for hypotension and hypervolemia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 28: 182–191, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shahgholian N, Ghafourifard M, Shafiei F: The effect of sodium and ultra filtration profile combination and cold dialysate on hypotension during hemodialysis and its symptoms. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res 16: 212–216, 2011 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Smirnov AV, Nesterova OB, Suglobova ED, Golubev RV, Vasil’ev AN, Vasil’eva IA, Verbitskaia EV, Korosteleva NI, Kostereva EM, Lebedeva EB, Levykina EN, Starosel’skiĭ KG, Lazeba VA: Clinical and laboratory evaluation of the efficiency of chronic hemodialysis treatment using acidosuccinate in patients with terminal renal failure. Ter Arkh 85: 69–75, 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Teruel JL, Martins J, Merino JL, Fernández Lucas M, Rivera M, Marcén R, Quereda C, Ortuño J: Temperature dialysate and hemodialysis tolerance. Nefrologia 26: 461–468, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.